Klimt's work focuses on all aspects of the Art Nouveau master's oeuvre. Visualized through a timeline, Klimt's creative periods are rolled up here, starting with his training, his collaboration with Franz Matsch and his brother Ernst in the "Künstler-Compagnie", the affair surrounding the faculty paintings and his post-fame and the myth that still surrounds this exceptional artist today.

Cradle of Modernism

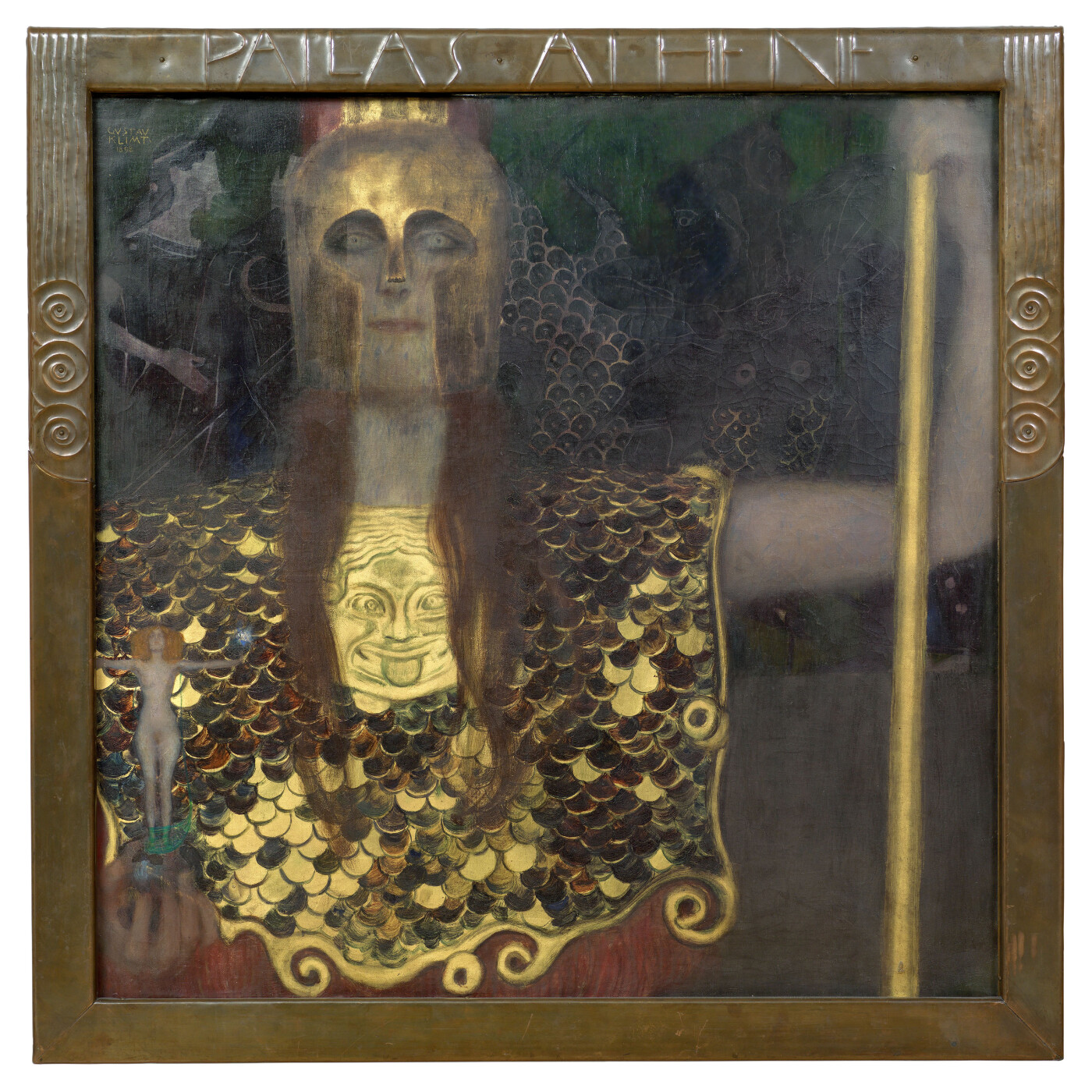

In the period between the foundation of the Secession in 1897 and the scandal surrounding the Faculty Painting of Philosophy in 1900, Gustav Klimt finally mutated into an exponent of Modernist art. In the Secession’s exhibitions he presented himself with the paintings for Nicolaus Dumba, as well as with Pallas Athene, Nuda Veritas, his monumental female portraits, and his first landscapes.

→

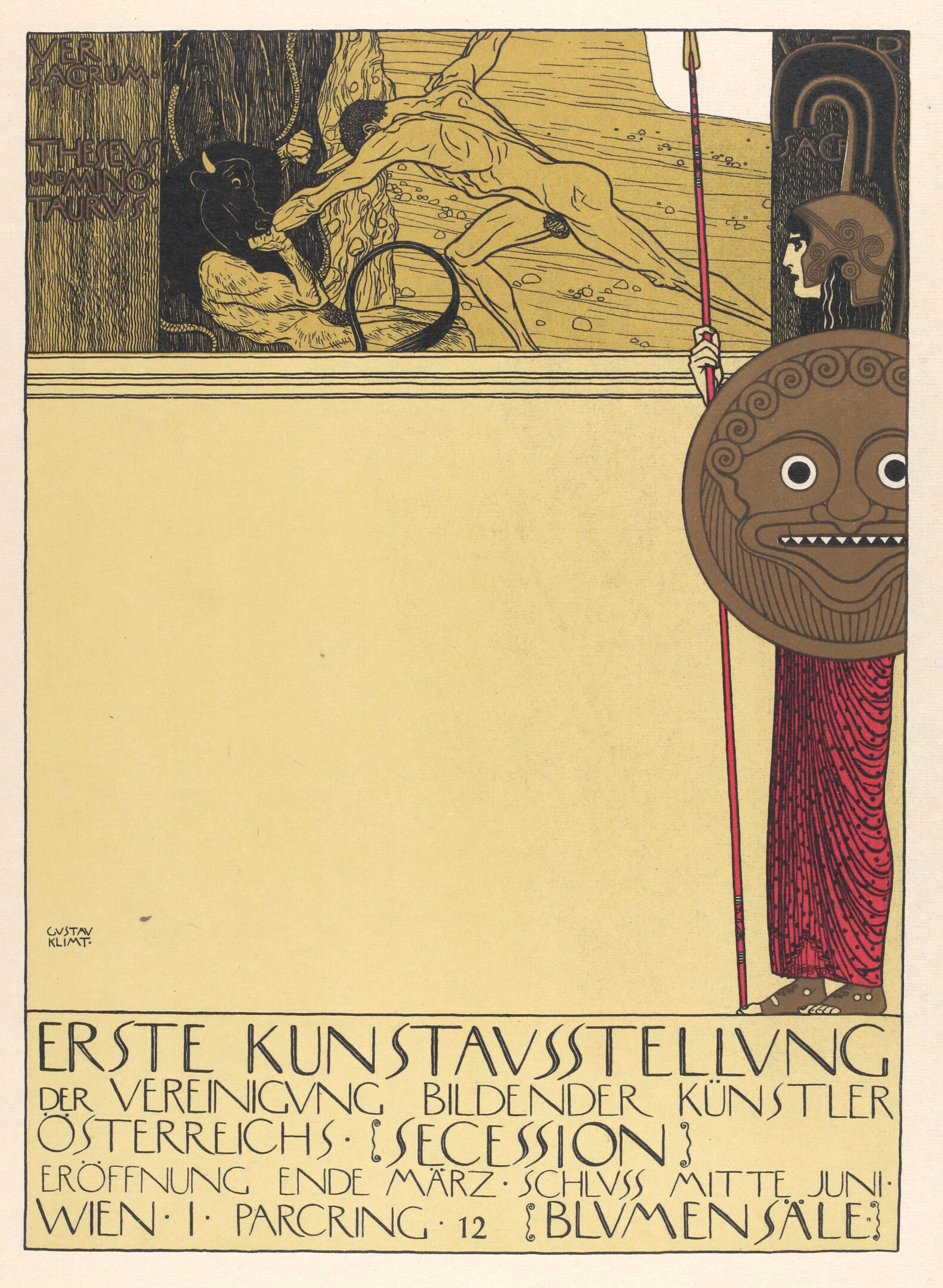

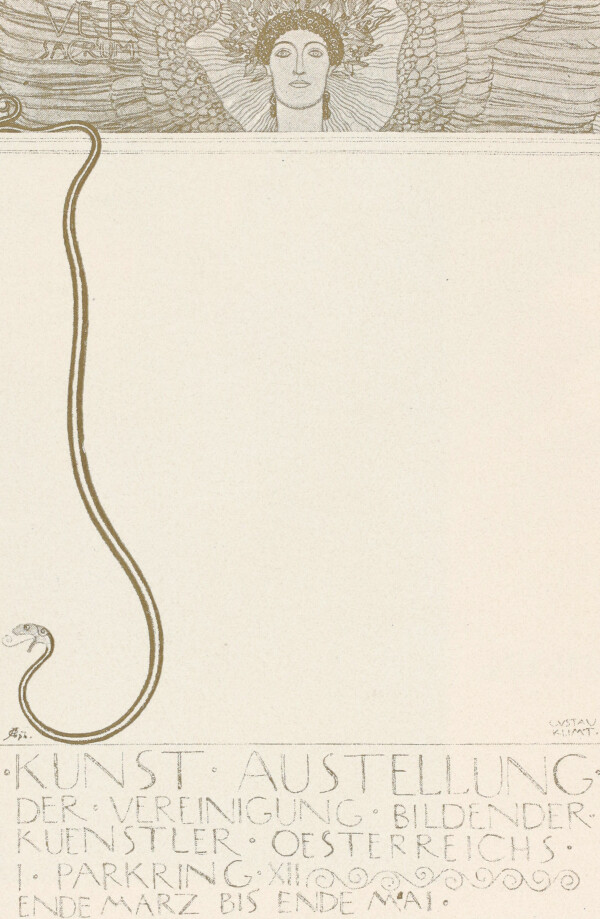

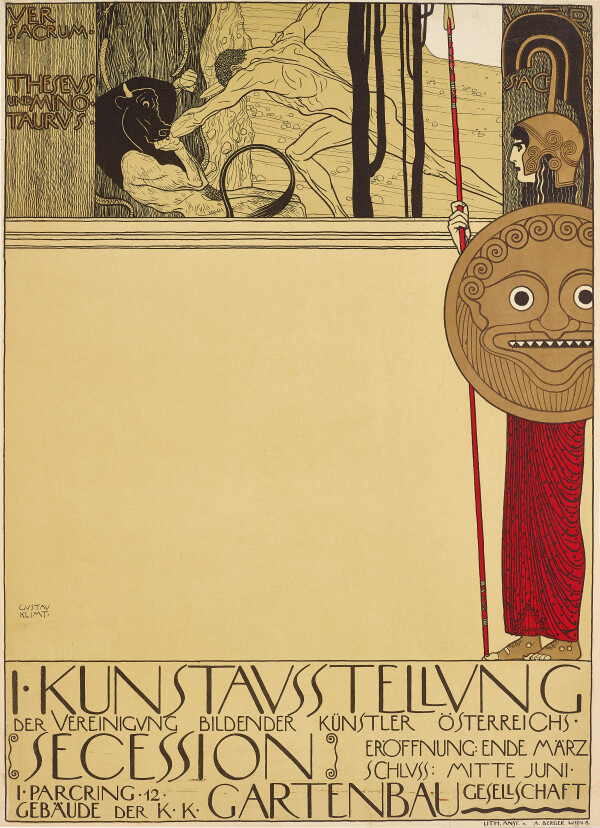

Gustav Klimt: Poster for the first exhibition of the Vienna Association (censored), 1898, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Palais Dumba

Gustav Klimt was commissioned by the influential patron and industrialist Nicolaus Dumba to decorate his music room with the two supraporte paintings Music and Schubert at the Piano. Though only the oil sketches for the paintings have survived in the original, they clearly illustrate Klimt’s emphatic exploration of International Modernism.

To the chapter

→

Josef Löwy: Insight into the music salon at Palais Dumba, 1899, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

© MAK

Myths, Fairy-Tales, and an Allegory

By the time Gustav Klimt painted his archaic Pallas Athene, the all-too-earthly allegory of Naked Truth, Nuda Veritas, and the painting Moving Water in 1898/99, he had already developed into a prominent exponent of Modernism. Within a short period of time, Klimt arrived at a “Secessionist” style in which he combined flatness, frontality, and golden luster with the subtle lightness of Post-Impressionist brushwork.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Moving Water, 1898, private collection

© Kallir Research Institute, New York

Modern Portraits

Gustav Klimt is known today as the author of impressive and monumental female portraits. But he only began to stand out in this genre at the age of thirty-six, with the portrait of Sonja Knips, followed by the painted likenesses of Serena Lederer and Trude Steiner, with which he increasingly established himself as the Painter of Women.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Sonja Knips, 1897/98, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

First Landscapes

From 1897, Klimt continuously worked in the genre of landscape painting. While his initial landscapes were committed to the style of Atmospheric Realism, his later works from the late 19th century onwards were increasingly influenced by Impressionism and Symbolism.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: A Morning by the Pond, 1899, Leopold Museum

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

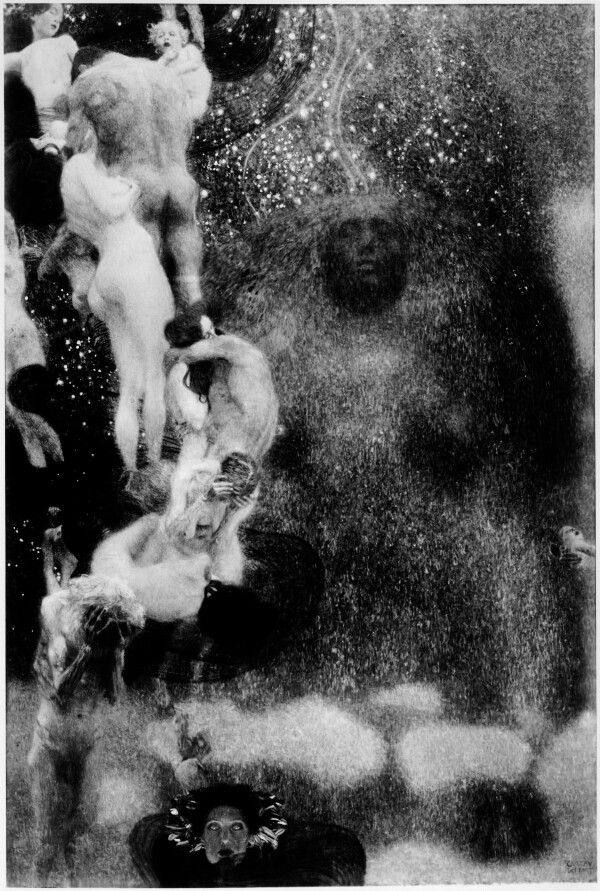

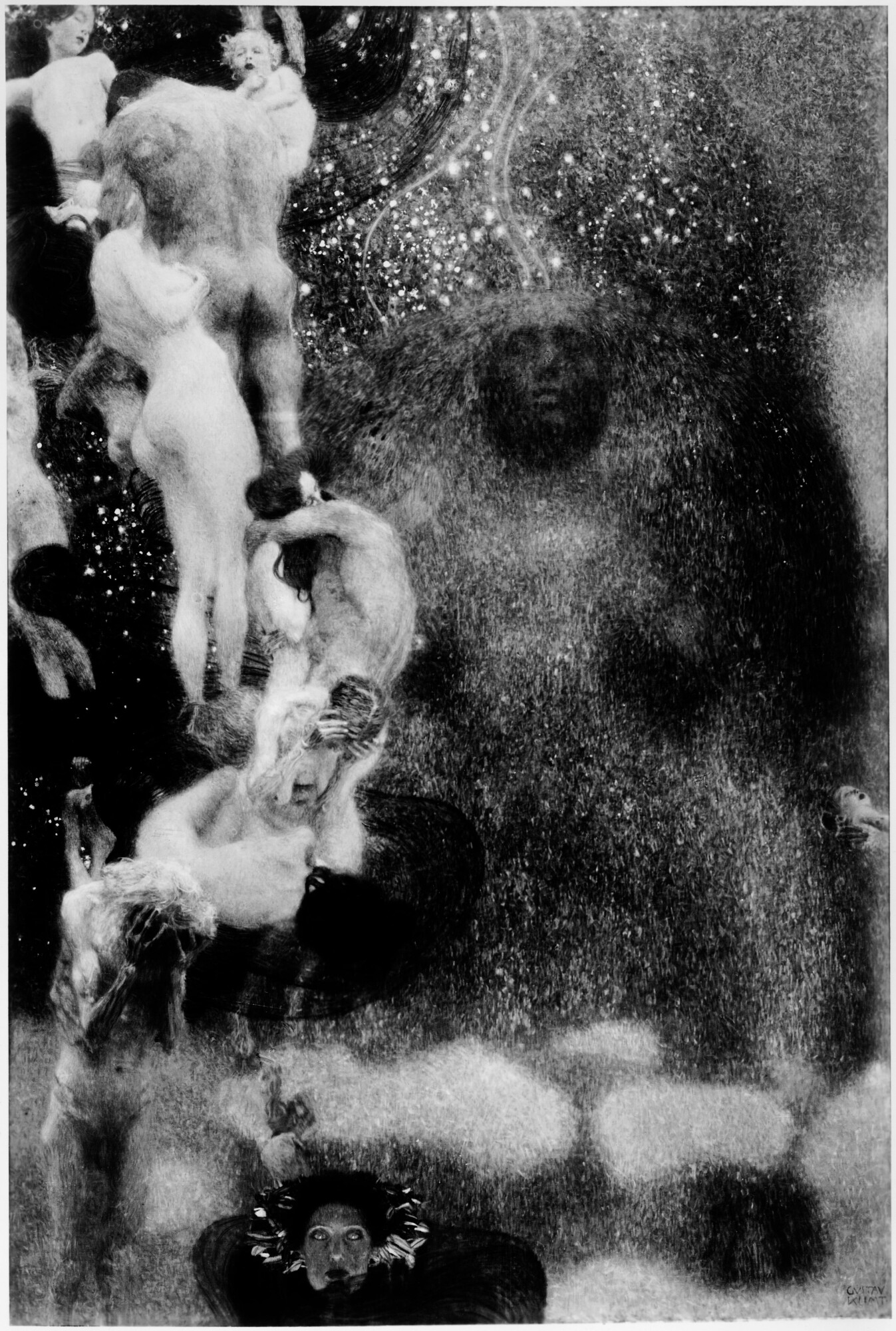

Faculty Paintings. Philosophy

The Faculty Painting Philosophy marks Gustav Klimt’s final break with academic traditions in favor of Symbolism. The painting’s first exhibition in 1900 caused a scandal. Following numerous alterations and additions, which were carried out until 1907, the work was destroyed in a fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Philosophy, 1900-1907, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt, in: Kunstverlag Hugo Heller (Hg.): Das Werk von Gustav Klimt, Vienna - Leipzig 1918.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

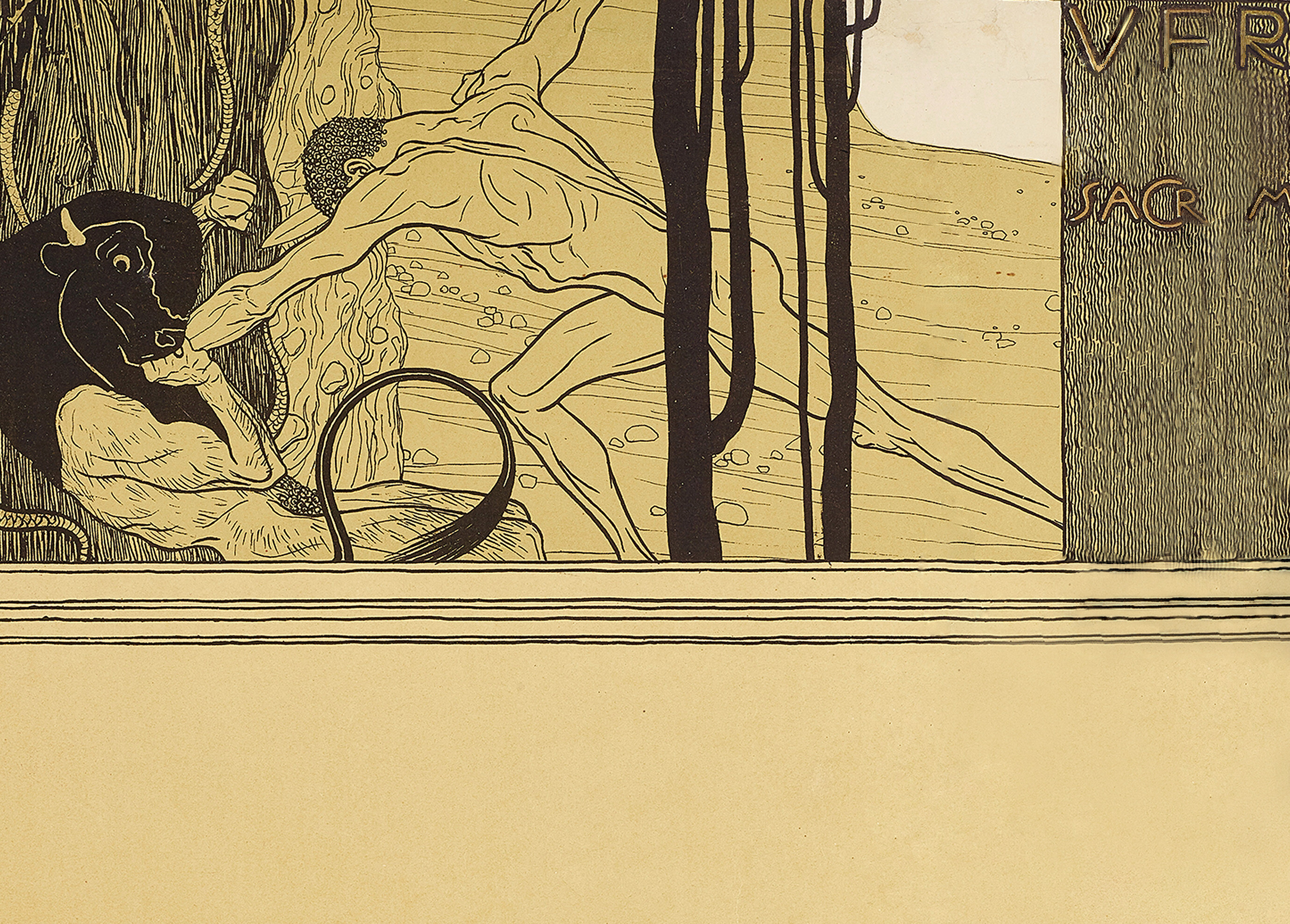

Ver Sacrum and Scandalous Poster

In his capacity as first president of the Vienna Secession, Gustav Klimt exerted a decisive influence on the direction of the new association. He designed the poster for the I. Kunst-Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs [1st Exhibition of the Vienna Secession], exhibited his own works alongside international avant-garde artists in this presentation, and furnished contributions for the association’s ground-breaking magazine Ver Sacrum.

To the chapter

→

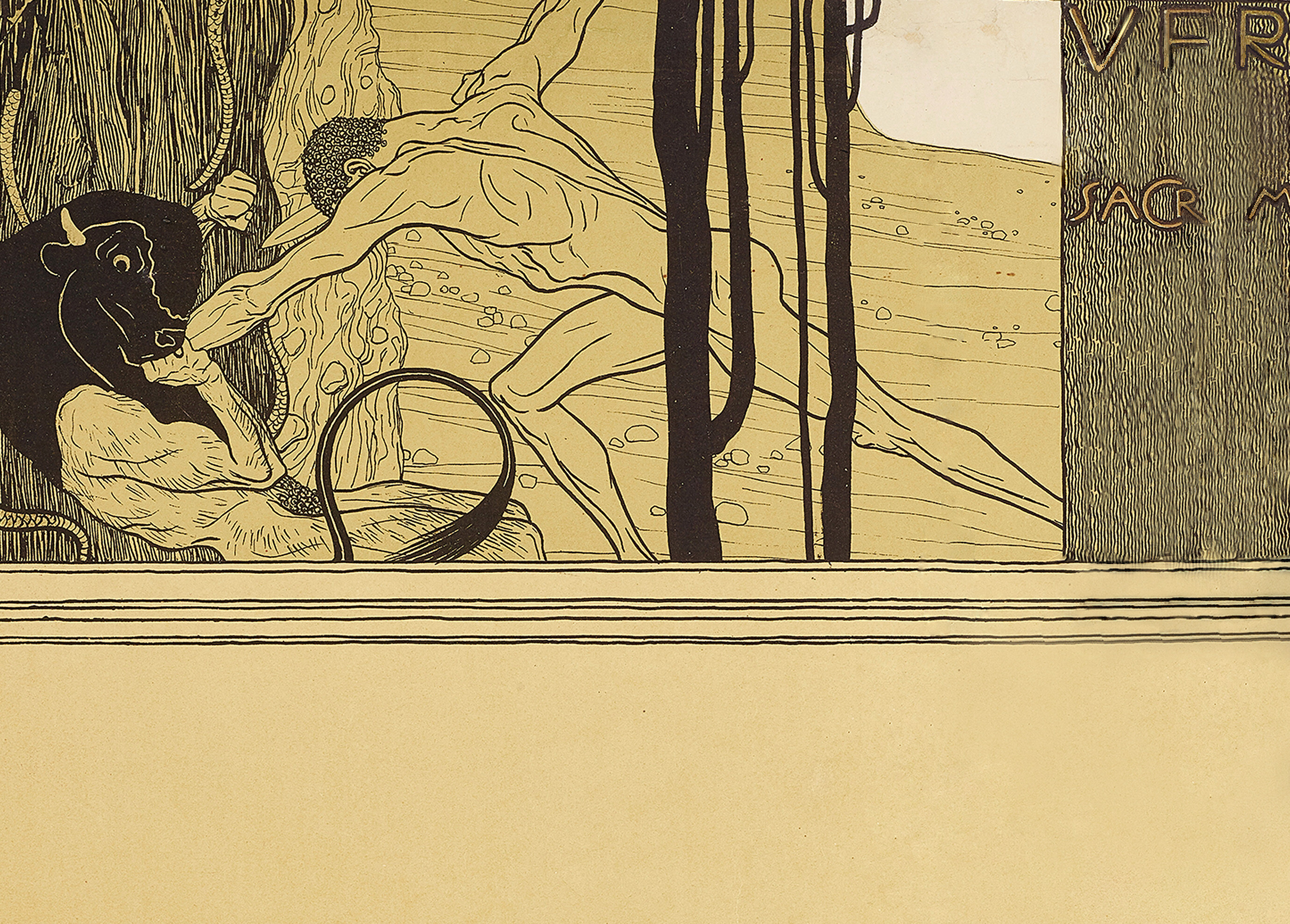

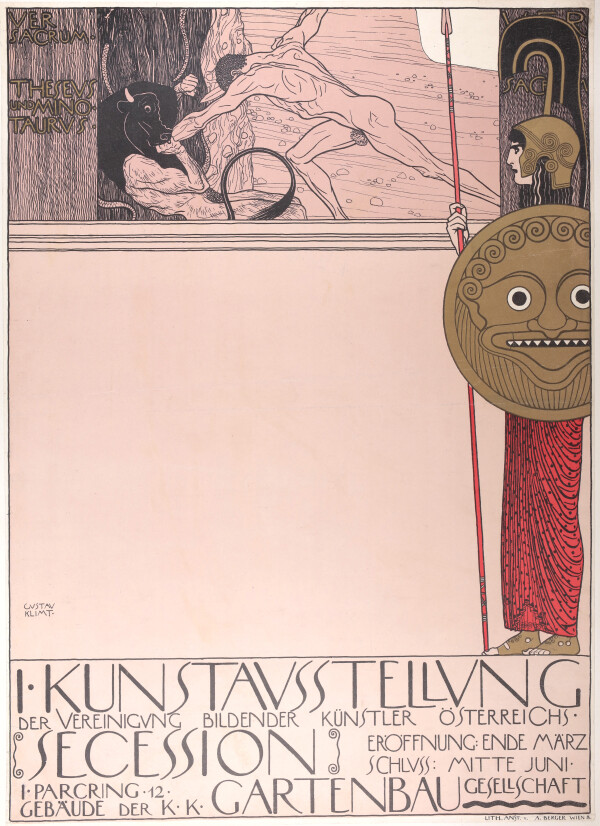

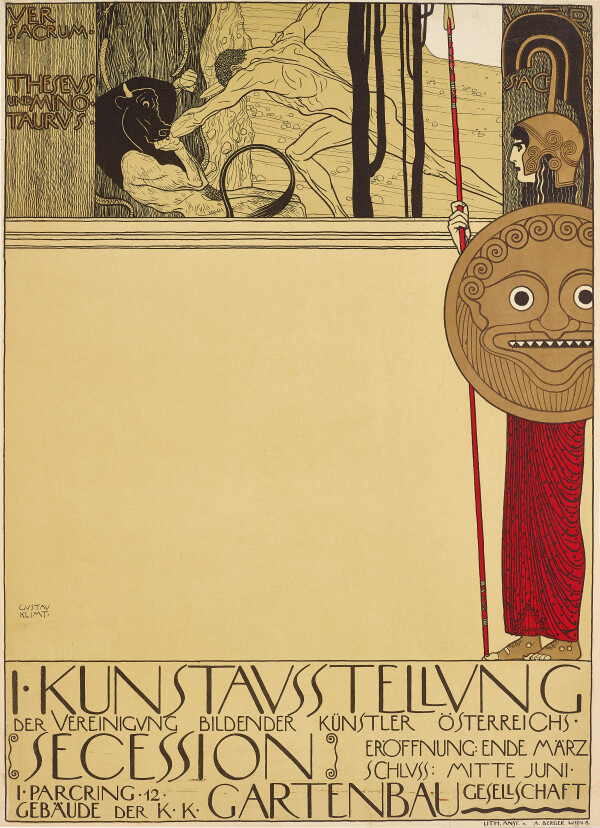

Gustav Klimt: Poster design for the I Secession Exhibition, uncensored version, 1898, private collection

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Exhibition Activity

In the late 1890s, Klimt developed from a Historicist decorator into an independent modern artist. The exhibitions of the newly founded Vienna Secession offered Klimt an ideal platform for presenting his increasingly Symbolist works – which, however, also provoked major scandals.

To the chapter

→

Alfons Mucha: Poster of Austria at the World Exhibition in Paris, 1900

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

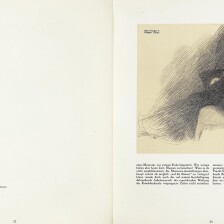

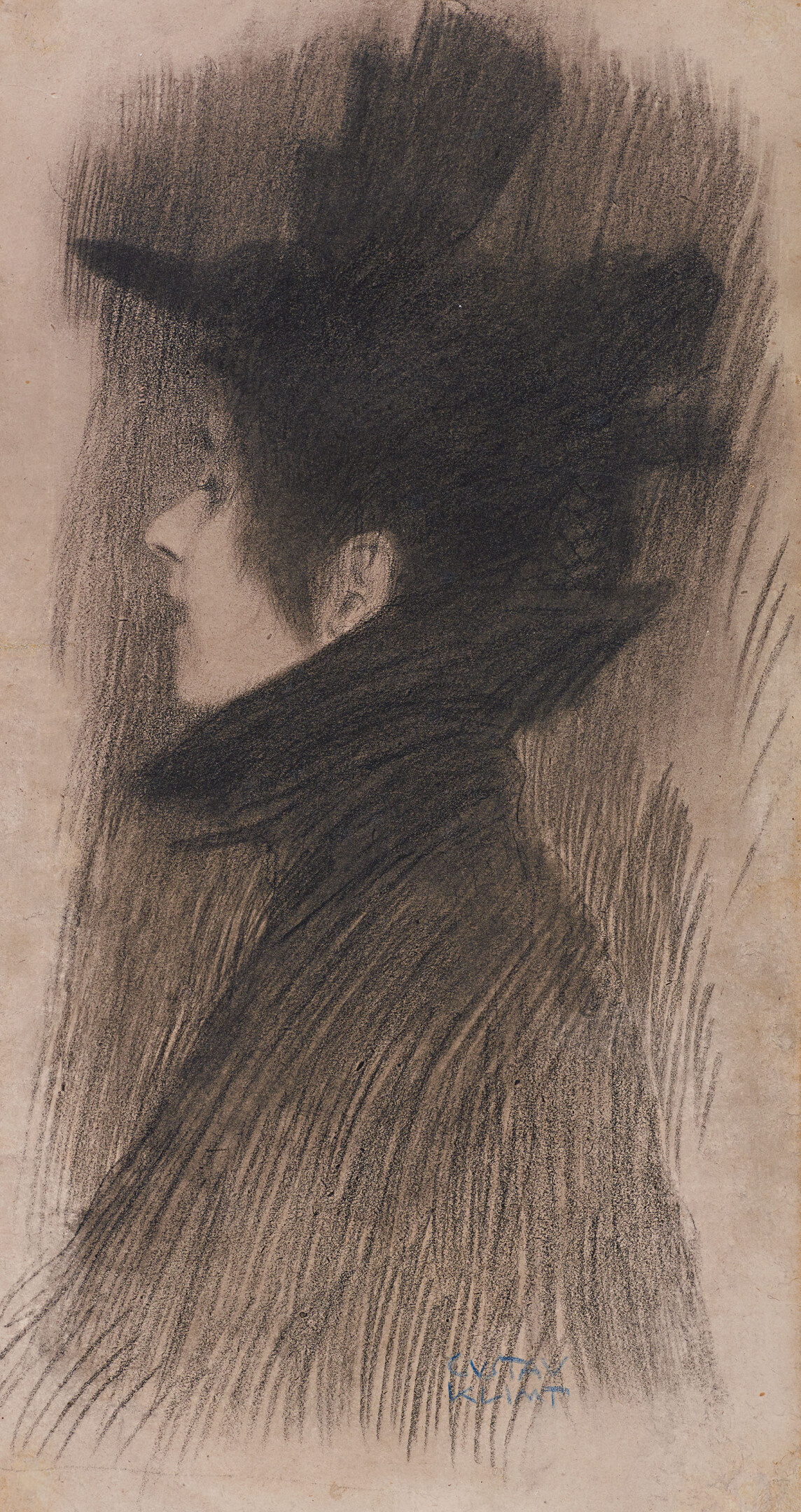

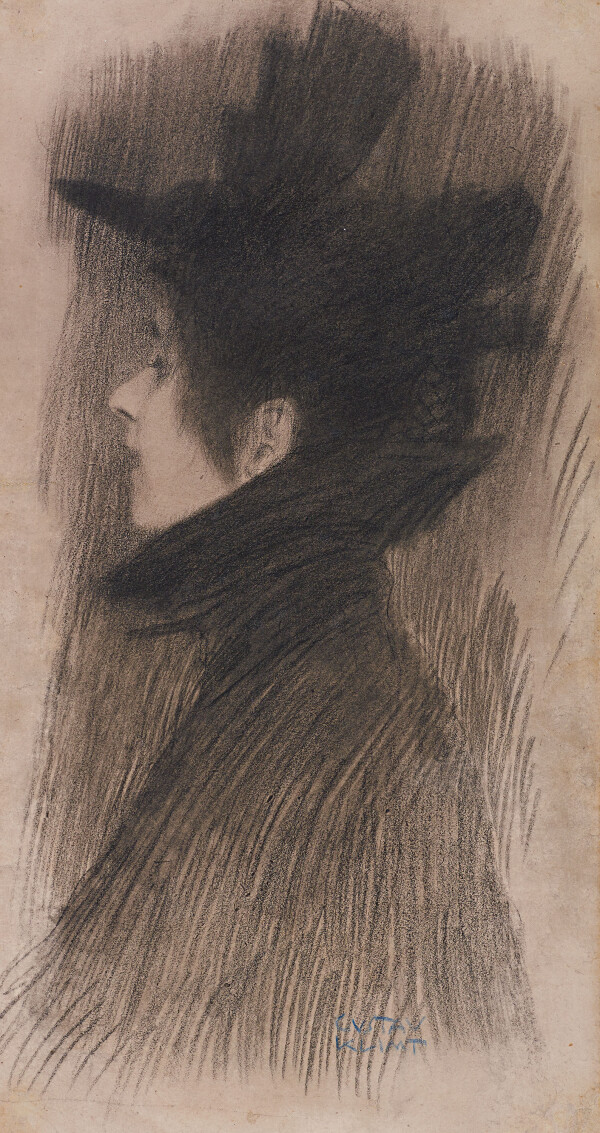

Drawings

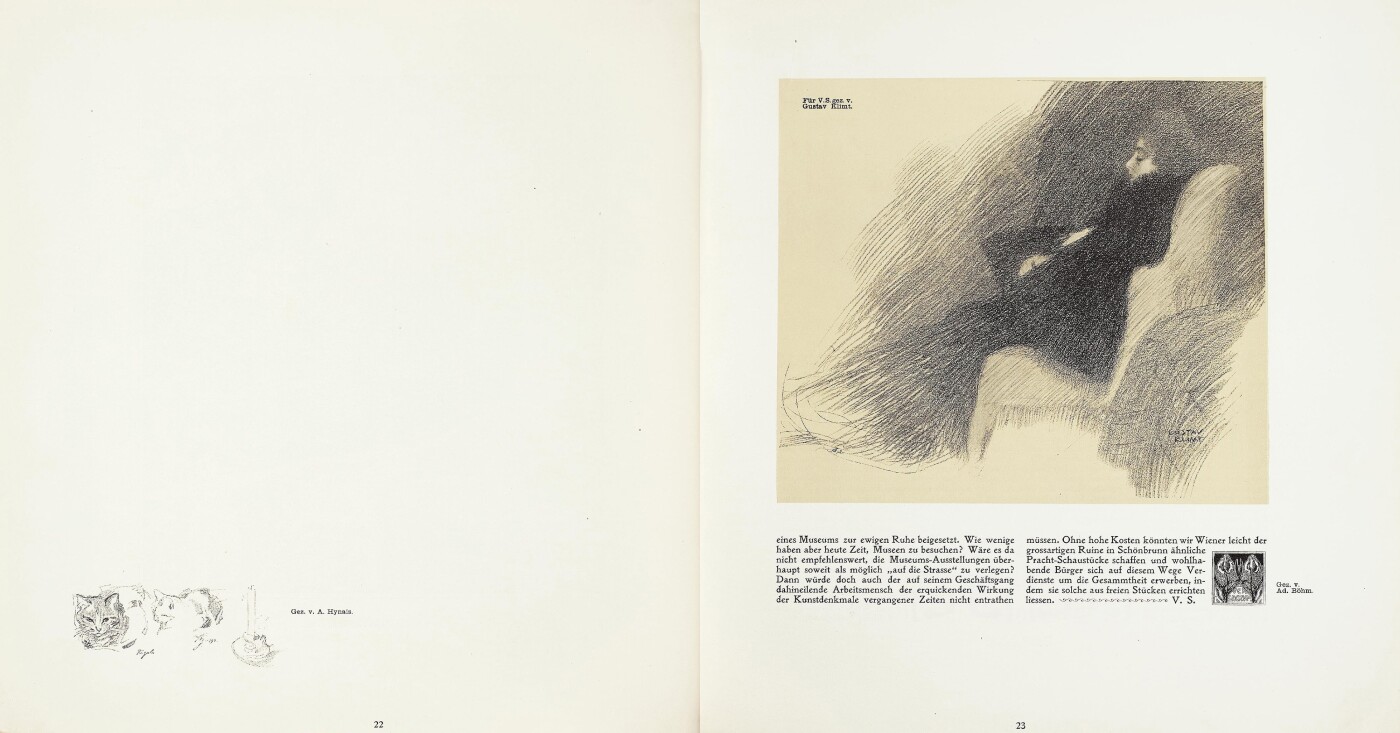

Shortly before 1900 Gustav Klimt worked in both chalk and ink, which allowed him to create fundamentally different effects with his atmospheric and intimate portraits of ladies on the one hand and his stylized allegories on the other. He was influenced by the movements of Symbolism and Jugendstil, both of which gained ground on the international scene.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Bust portrait of a young lady with hat and cape in profile to the left, 1897/98, Leopold Museum

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

Cradle of Modernism

In the period between the foundation of the Secession in 1897 and the scandal surrounding the Faculty Painting of Philosophy in 1900, Gustav Klimt finally mutated into an exponent of Modernist art. In the Secession’s exhibitions he presented himself with the paintings for Nicolaus Dumba, as well as with Pallas Athene, Nuda Veritas, his monumental female portraits, and his first landscapes.

→

Gustav Klimt: Poster for the first exhibition of the Vienna Association (censored), 1898, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

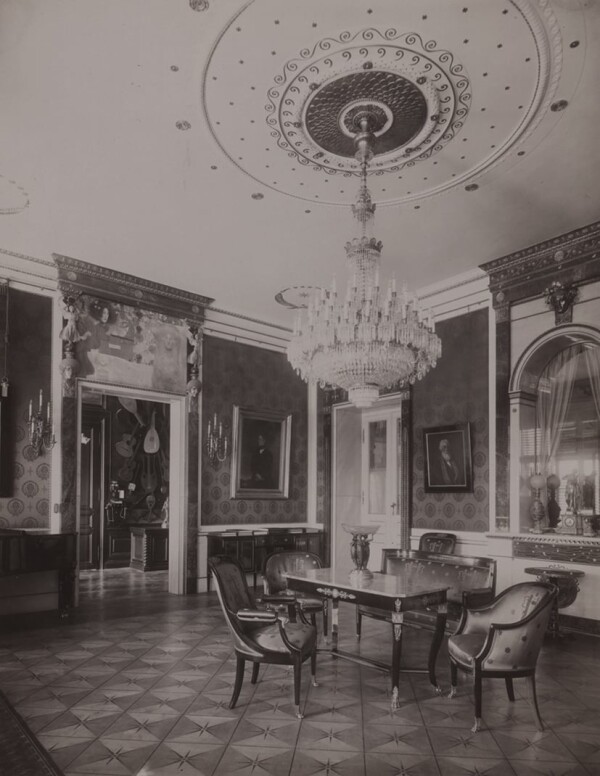

Palais Dumba

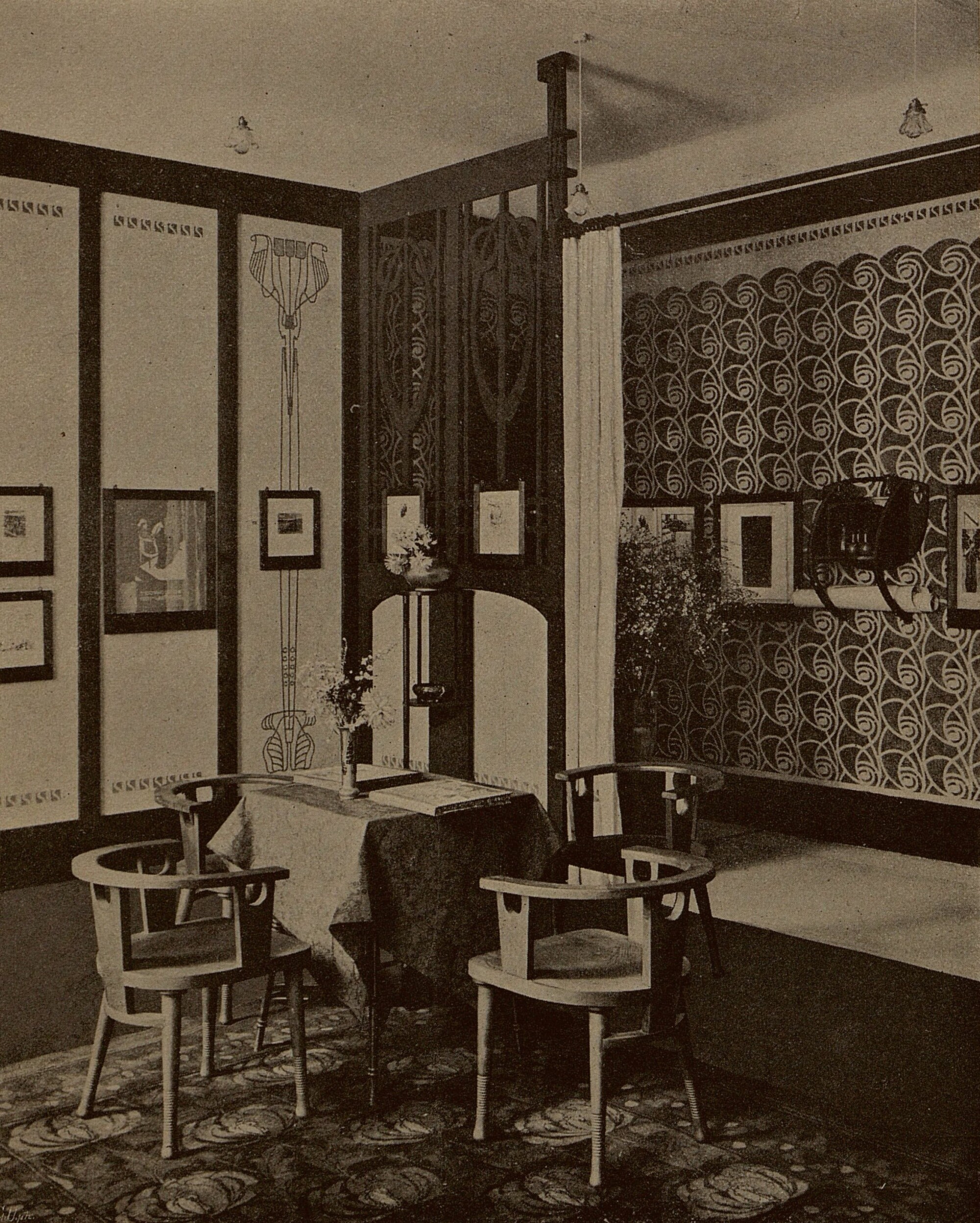

Josef Löwy: Insight into the music salon at Palais Dumba, 1899, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

© MAK

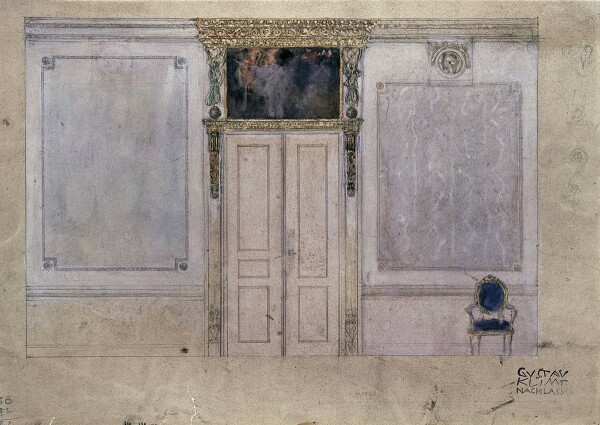

Gustav Klimt: Design of a wall with door and supraporte of the Dumba music salon, circa 1897, private collection

© Scala Florence

Gustav Klimt was commissioned by the influential patron and industrialist Nicolaus Dumba to decorate his music room with the two supraporte paintings Music and Schubert at the Piano. Though only the oil sketches for the paintings have survived in the original, they clearly illustrate Klimt’s emphatic exploration of International Modernism.

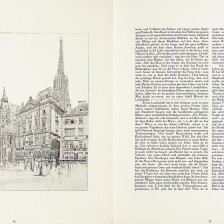

When it came to decorating the representational rooms of his mansion on the Vienna Ringstraße, the eminent commissioner, Schubert collector and patron Nicolaus Dumba wanted to engage only the best Viennese painters of his time. In the 1870s, Hans Makart had already been commissioned to design the office, which was captured for posterity in paintings and photographs. Twenty years later, Dumba tasked the two artists Franz Matsch and Gustav Klimt with the decoration of the dining and music rooms.

The two up-and-coming artists had received the commission already in 1893, but the (architectural) planning and implementation went ahead only four years later. Along with the paintings, Klimt also planned to design the doors, internal elevations and ceiling, for which two relevant drafts have survived (1897, Wien Museum, 1897, private collection).

Reflecting on the extended period of time it took for the music room at Palais Dumba to be completed, the Klimt critic Karl Kraus trenchantly commented in his magazine Die Fackel:

“He [Nicolaus Dumba] had placed the order for the paintings in his music room at a time when Klimt still adhered to the upright style of the Laufberger School, with no more than the odd Makart-esque extravagance strewn in here and there. In the meantime, however, the artist had discovered Khnopff, and – to get the point of the story – has turned into a Pointillist. Naturally, the commissioner has to go along with all of this. Thus, Herr von Dumba has become a Modernist.”

Nicolaus Dumba in his study, around 1890

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

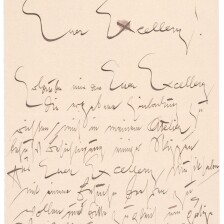

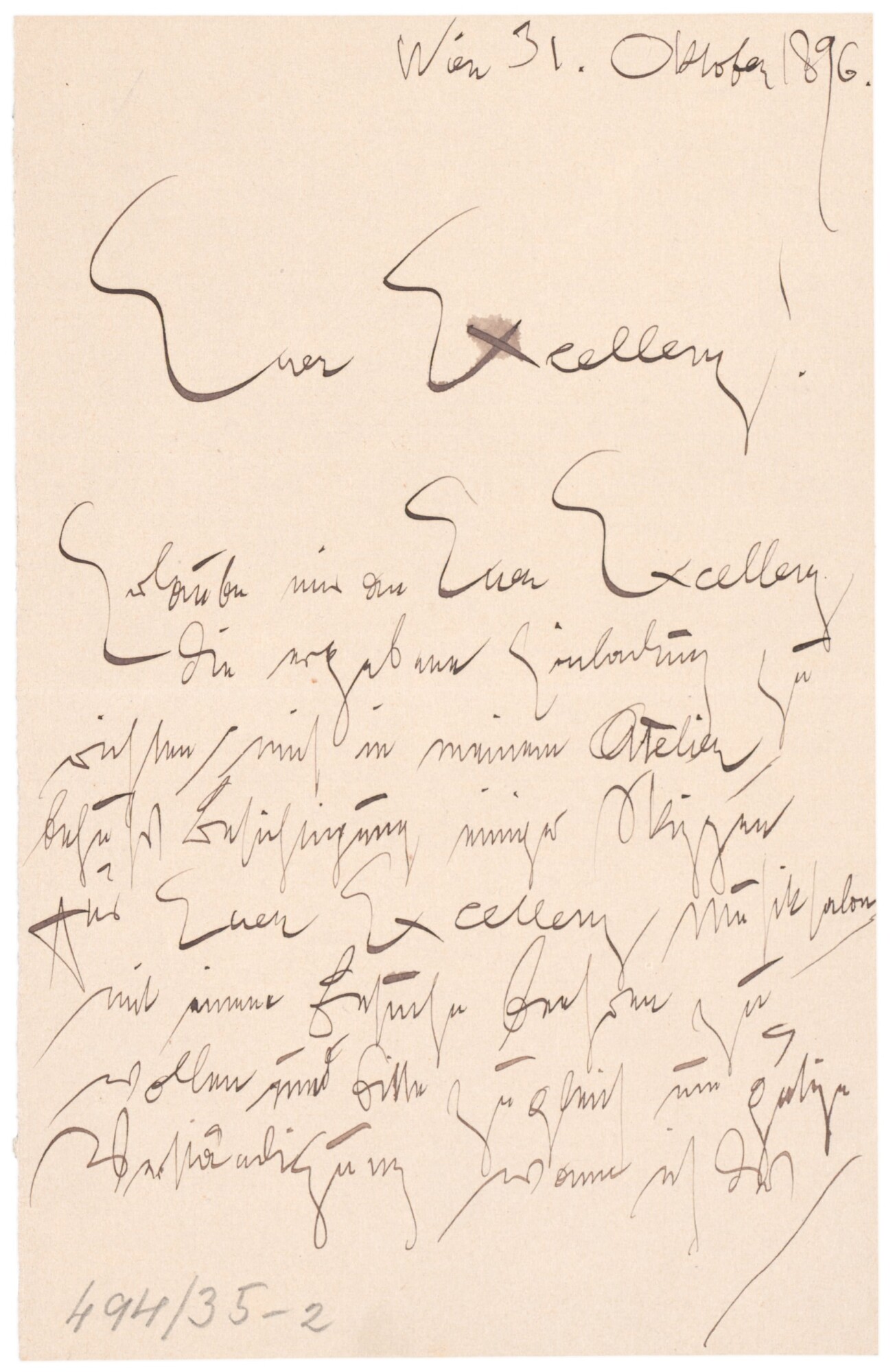

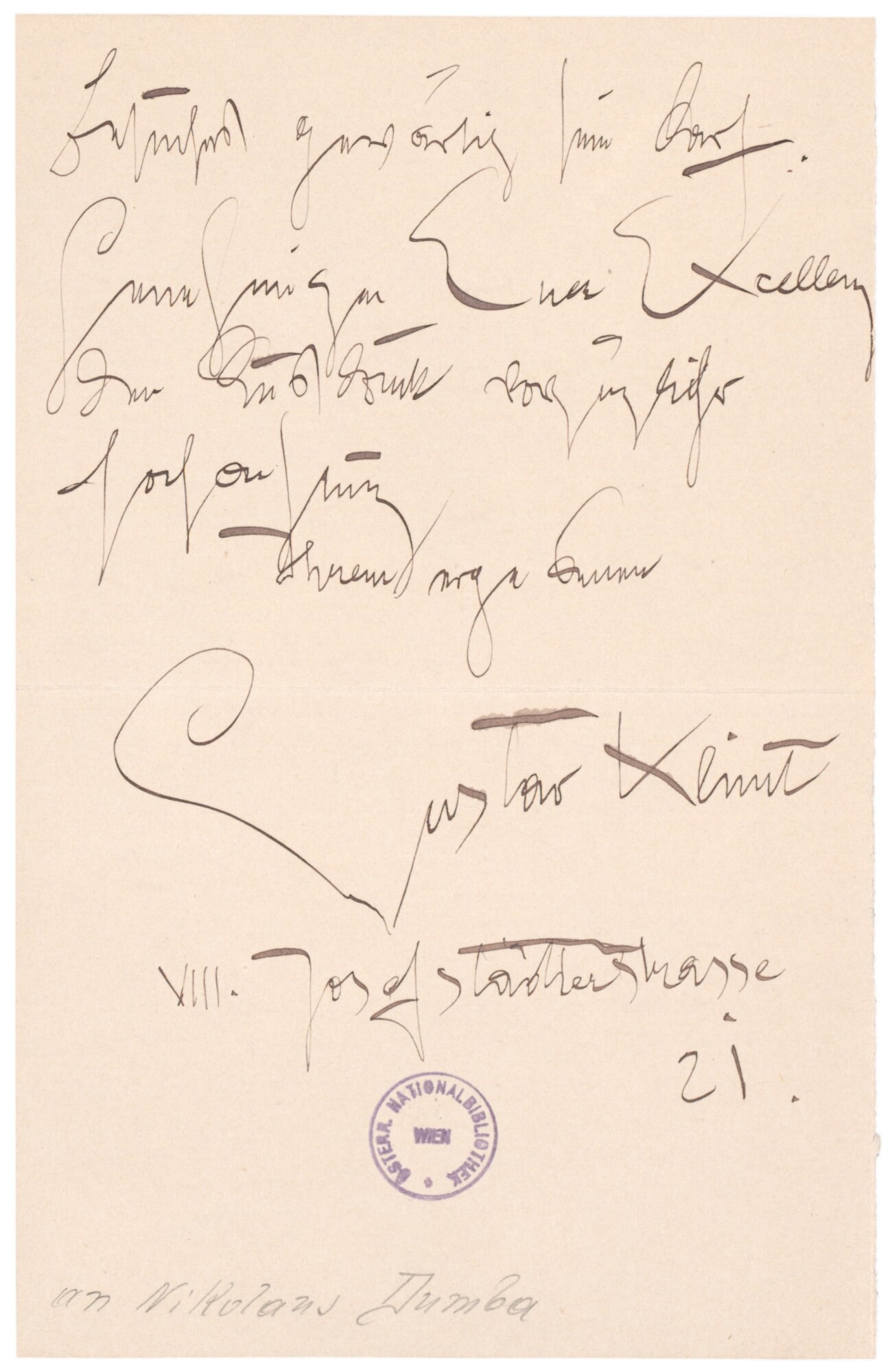

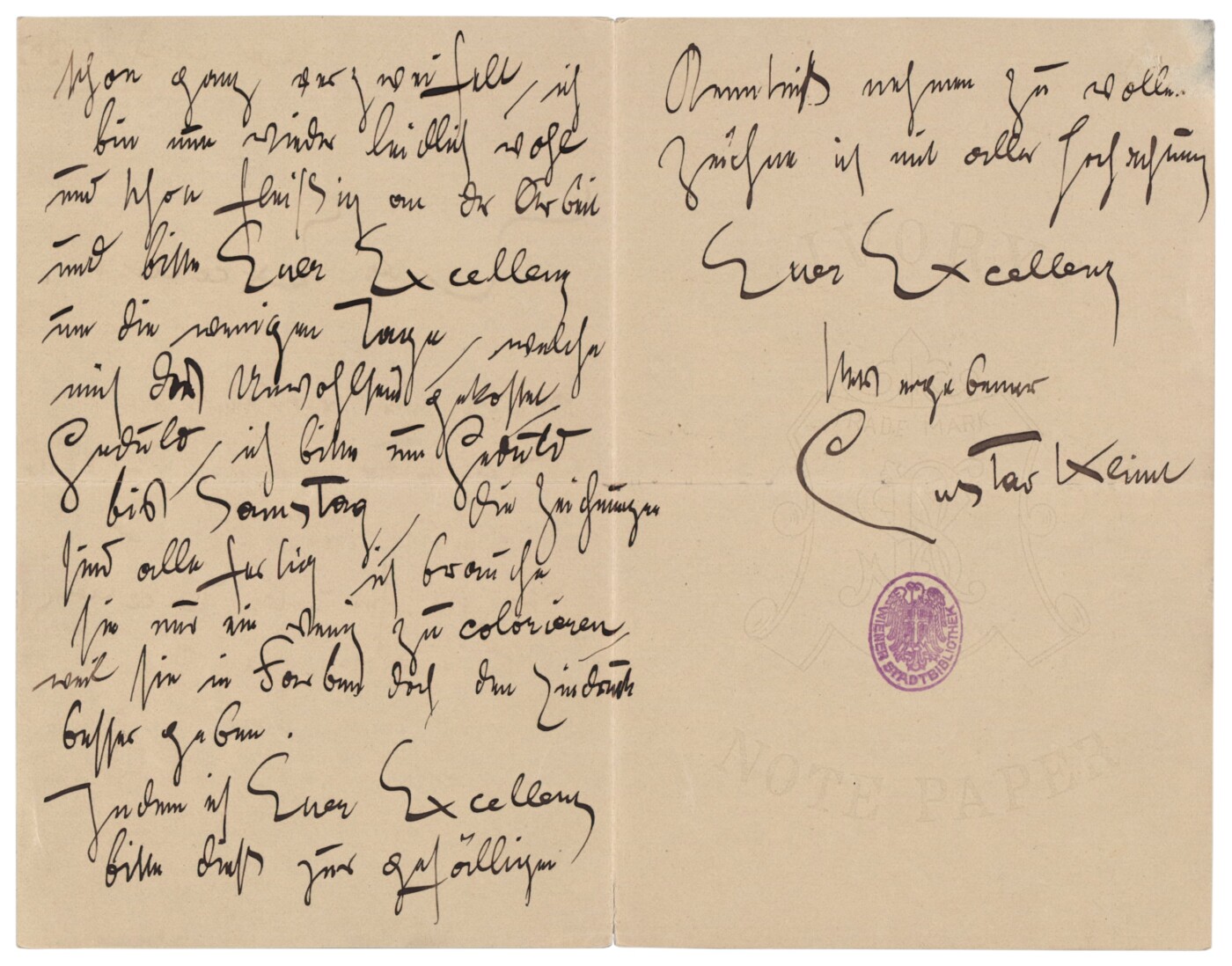

Letters from Gustav Klimt to Nicolaus Dumba from 1896/97

-

Gustav Klimt: Letter from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Nicolaus Dumba, 10/31/1896, Austrian National Library

Gustav Klimt: Letter from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Nicolaus Dumba, 10/31/1896, Austrian National Library

© Department of Manuscripts and Rare Books, Austrian National Library -

Gustav Klimt: Letter from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Nicolaus Dumba, 10/31/1896, Austrian National Library

Gustav Klimt: Letter from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Nicolaus Dumba, 10/31/1896, Austrian National Library

© Department of Manuscripts and Rare Books, Austrian National Library -

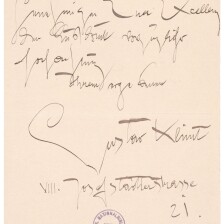

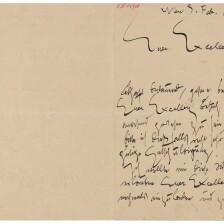

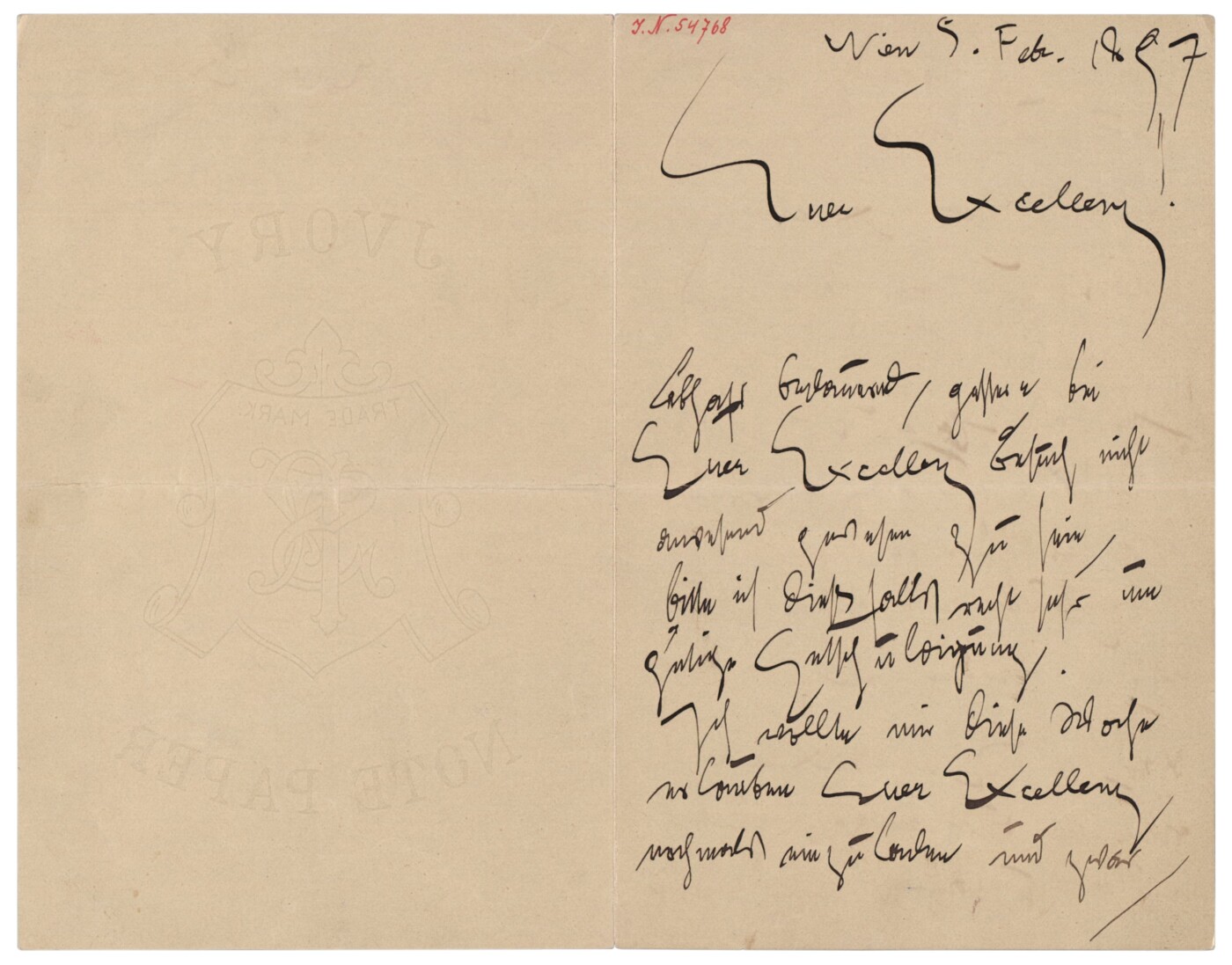

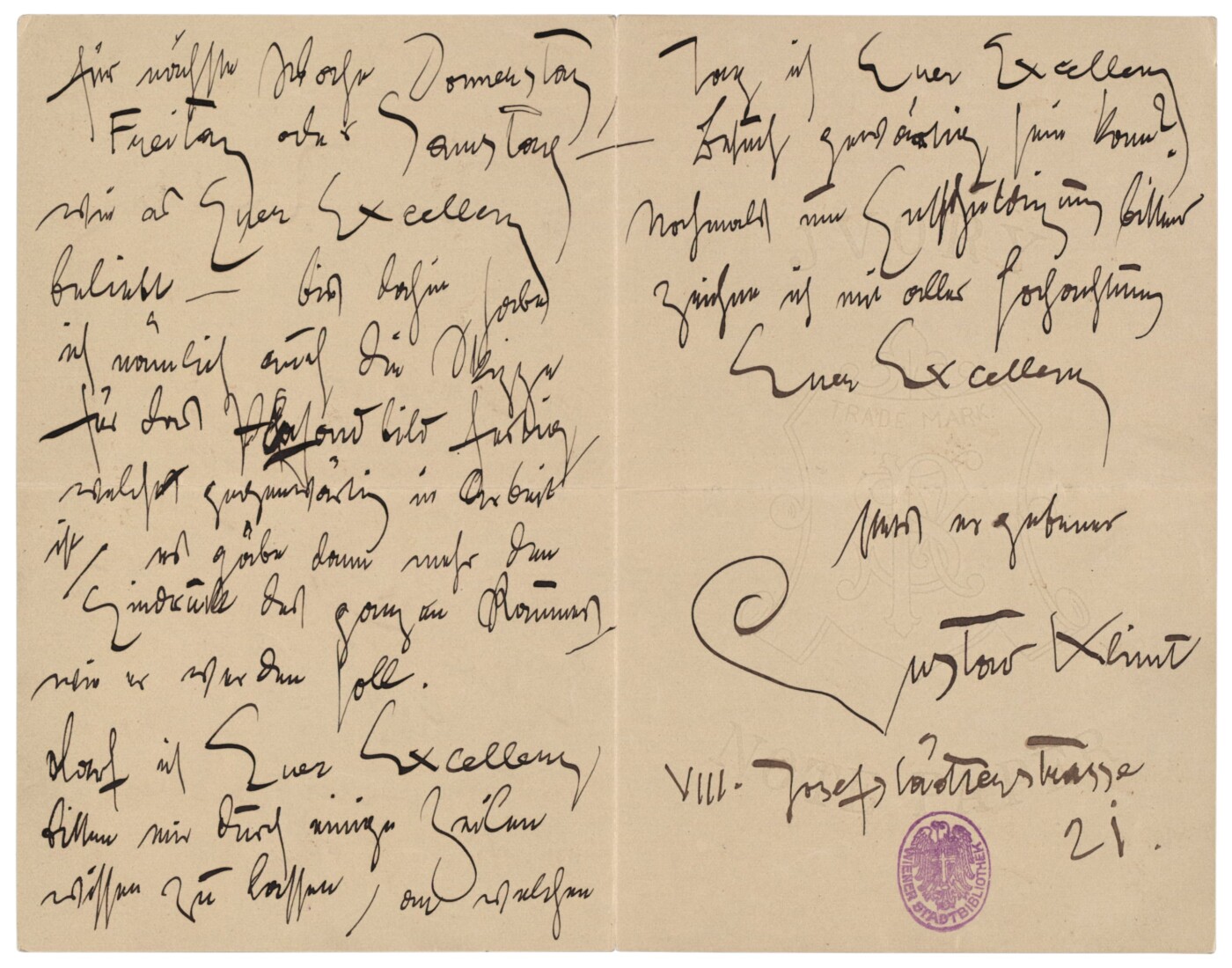

Gustav Klimt: Letter from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Nicolaus Dumba in Vienna, 02/09/1897, Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Handschriftensammlung, Partial estate of Nicolaus Dumba

Gustav Klimt: Letter from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Nicolaus Dumba in Vienna, 02/09/1897, Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Handschriftensammlung, Partial estate of Nicolaus Dumba

© Vienna City Library, Manuscript collection -

Gustav Klimt: Letter from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Nicolaus Dumba in Vienna, 02/09/1897, Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Handschriftensammlung, Partial estate of Nicolaus Dumba

Gustav Klimt: Letter from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Nicolaus Dumba in Vienna, 02/09/1897, Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Handschriftensammlung, Partial estate of Nicolaus Dumba

© Vienna City Library, Manuscript collection -

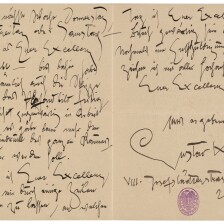

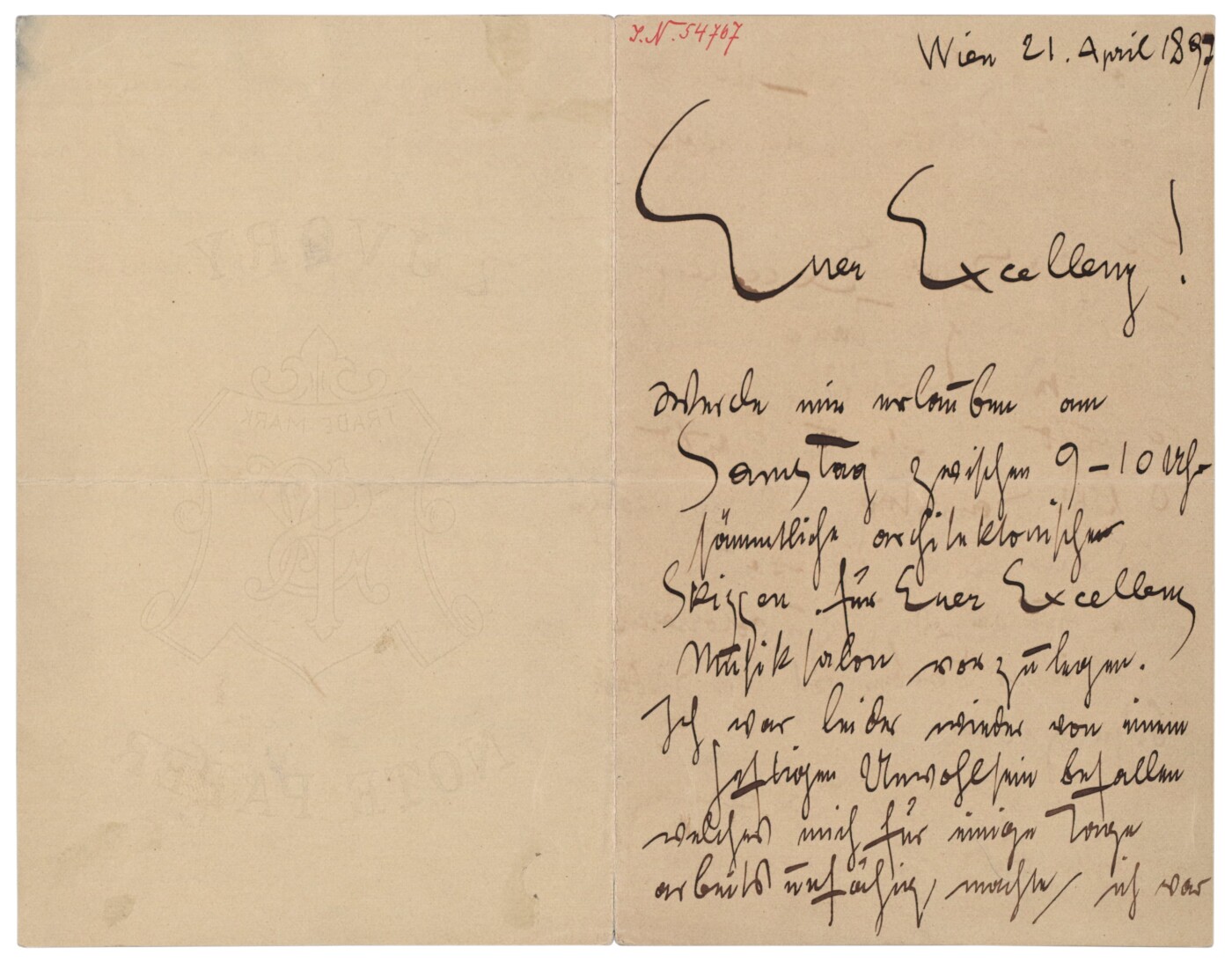

Gustav Klimt: Letter from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Nicolaus Dumba in Vienna, 04/21/1897, Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Handschriftensammlung, Partial estate of Nicolaus Dumba

Gustav Klimt: Letter from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Nicolaus Dumba in Vienna, 04/21/1897, Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Handschriftensammlung, Partial estate of Nicolaus Dumba

© Vienna City Library, Manuscript collection -

Gustav Klimt: Letter from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Nicolaus Dumba in Vienna, 04/21/1897, Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Handschriftensammlung, Partial estate of Nicolaus Dumba

Gustav Klimt: Letter from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Nicolaus Dumba in Vienna, 04/21/1897, Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Handschriftensammlung, Partial estate of Nicolaus Dumba

© Vienna City Library, Manuscript collection

Salon in Palais Dumba, presumably before it was converted into a music salon, around 1890

© Wien Museum

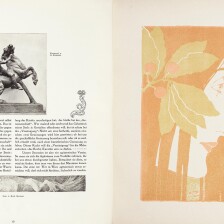

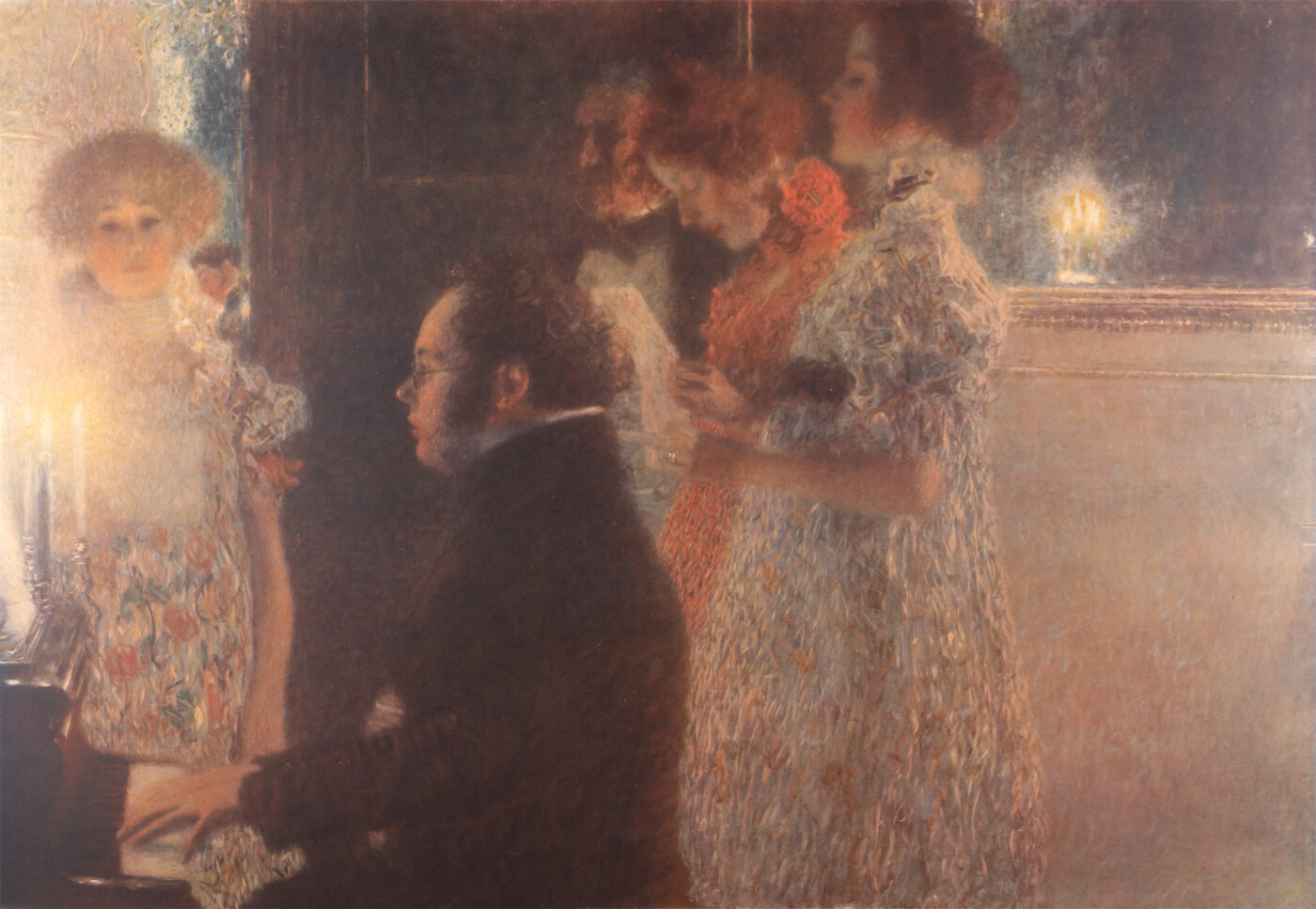

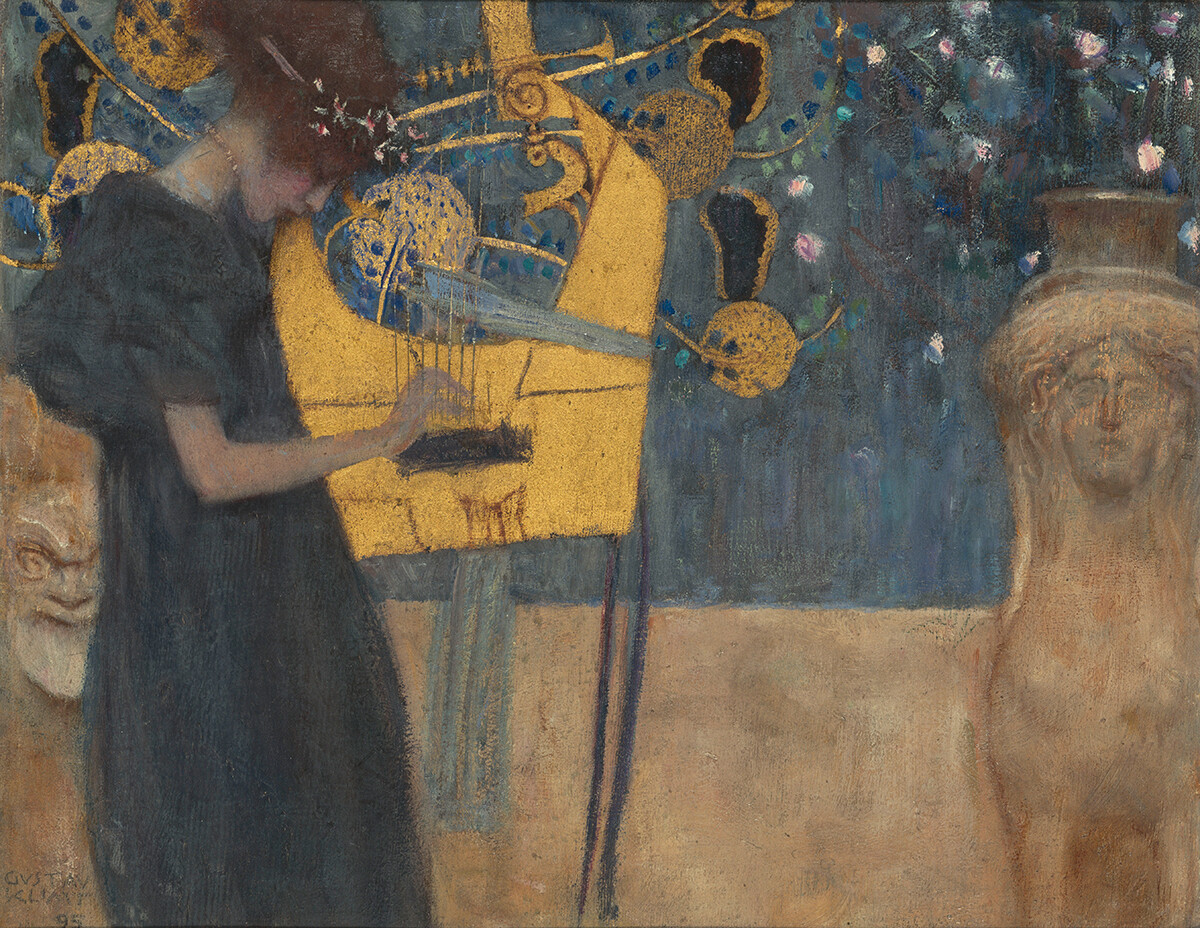

Music and Schubert at the Piano

The two paintings Klimt executed in 1897/98 and 1899 respectively, illustrate his evolution towards Symbolism, Victorian painting and French-Belgian post-Impressionism.

The motifs in the executed painting Music appear much clearer than they do in the preparatory study. The cithara player turns away from the depiction in the painting, resting the instrument on the low wall, with the ornamental background taking up the entire image space. Klimt increasingly dispensed with diffusely painted, post-impressionist elements to accord more space to planar areas. The same tendency can be observed in his painting Schubert at the Piano. In the lost execution of the work, the portrait of the composer is framed by a black door. While the candlelight still shows remnants of Pointillist painting, Gustav Klimt started to develop his own, original style during his work on the two paintings in the second half of the 1890s – that of a planar Jugendstil.

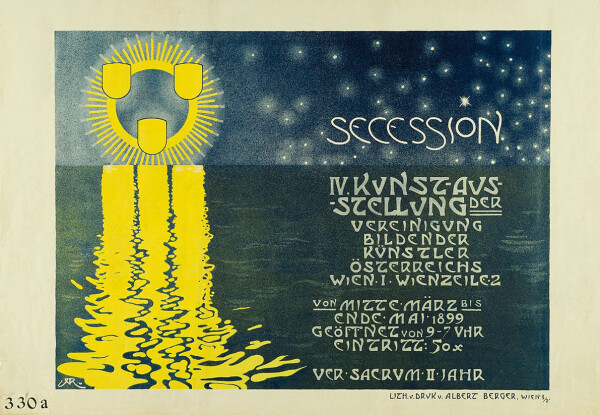

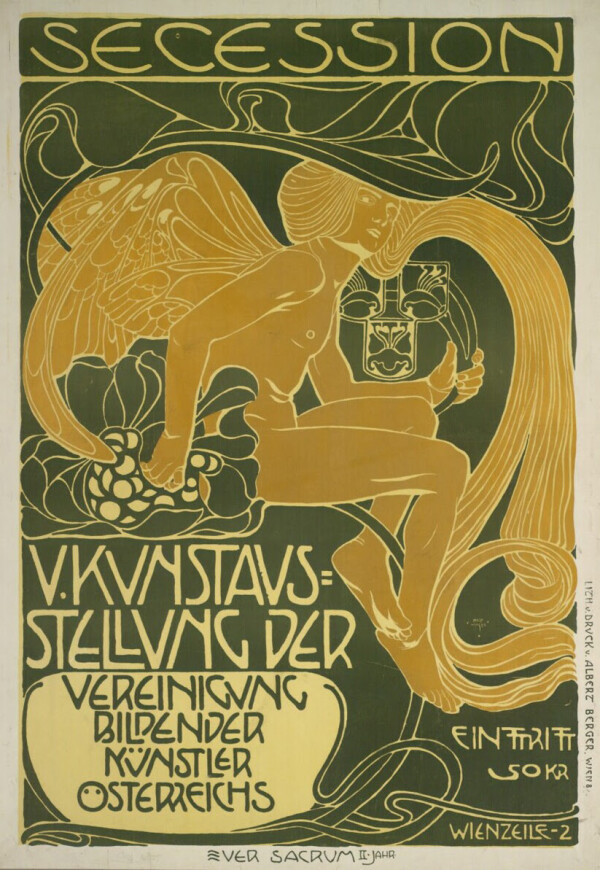

Reviews of Klimt’s Supraporte Paintings

Gustav Klimt presented the commissioned works at the 1st and 4th exhibitions of the Vienna Secession, held in 1898 and 1899. While Music was barely mentioned in the press, the painting Schubert at the Piano was lauded by the majority of critics in 1899. The Austrian author Hermann Bahr even called it “the most beautiful painting ever painted by an Austrian.” A journalist for the newspaper Arbeiter-Zeitung placed the two supraporte paintings into direct comparison:

“The color effects of the two paintings are completely different. While the first one was colorful, radiant, powerful, decorative-fantastical, this one [Schubert at the Piano] is characterized by colors that are duller, duskier and more delicate. In terms of the coloring, the artist has certainly not made things easy for himself. […] The painting is highly subjective, wants to be seen in isolation and requires an unusually profound understanding of the artist’s intentions.”

Schubert at the Piano and Music

-

Gustav Klimt: Schubert at the Piano (Study), 1896/97, private collection

Gustav Klimt: Schubert at the Piano (Study), 1896/97, private collection

© Leopold Museum, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Schubert at the Piano, 1899, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

Gustav Klimt: Schubert at the Piano, 1899, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Josef Löwy: Schubert at the piano, 1899, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

Josef Löwy: Schubert at the piano, 1899, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

© MAK -

Gustav Klimt: Music (Study), 1895, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen - Neue Pinakothek München

Gustav Klimt: Music (Study), 1895, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen - Neue Pinakothek München

© bpk | Bavarian State Painting Collections -

Gustav Klimt: Music, 1897/98, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

Gustav Klimt: Music, 1897/98, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Josef Löwy: The music, 1899, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

Josef Löwy: The music, 1899, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

© MAK

The Works’ Whereabouts

The decor of Palais Dumba has not survived in its entirety, nor have the two supraporte paintings, which were likely destroyed in a fire at Immendorf Castle at the end of World War II. The paintings were exhibited for the last time in 1943. The only impression we have of the works today is from reproductions, several contemporary photographs and the two oil drafts, which are kept at the Bavarian State Painting Collections in Munich and in a private collection (permanent loan at the Leopold Museum, Vienna).

Literature and sources

- Carl Schreder: Erste Kunstausstellung der Secession, in: Deutsches Volksblatt, 22.04.1898, S. 3.

- N. N.: Wiener Briefe, in: (Salzburger) Fremden-Zeitung, 02.04.1898, S. 4.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band I, 1878–1903, Salzburg 1980, S. 101-103.

- Ludwig Hevesi: Das Heim eines Wiener Kunstfreundes (Nikolaus Dumba), in: Kunst und Kunsthandwerk. Monatsschrift des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie, 2. Jg., Heft 10 (1899), S. 341-365.

- Hermann Bahr: Secession, Vienna 1900, S. 120-121.

- Arbeiter-Zeitung, 21.03.1899, S. 4-5.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alexander Klee (Hg.): Klimt und die Ringstraße, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna), 05.07.2015–11.10.2015, Vienna 2015.

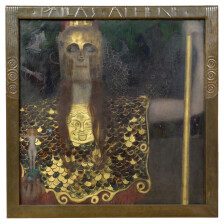

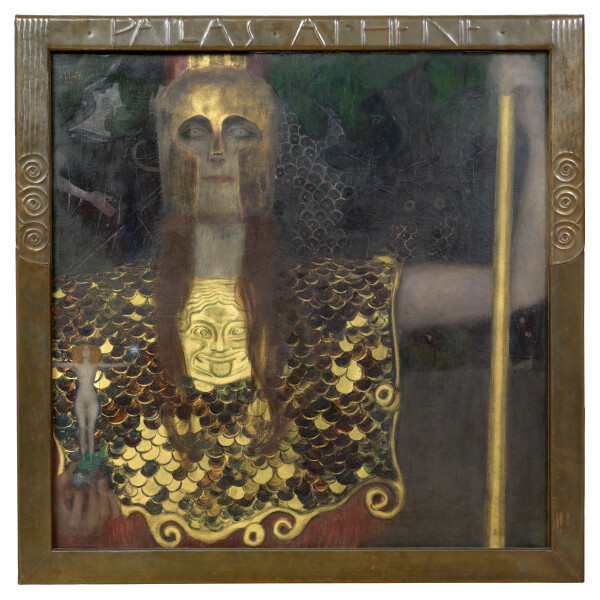

Myths, Fairy-Tales, and an Allegory

Gustav Klimt: Pallas Athene, 1898, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

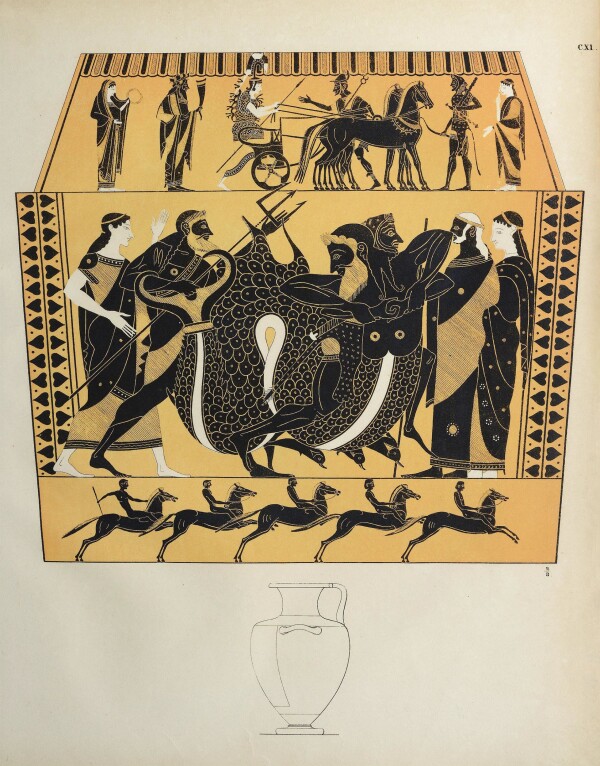

Panel CXI, in: Eduard Gerhard (Hg.): Auserlesene Griechische Vasenbilder, hauptsächlich Etruskischen Fundorts, Band 2, Berlin 1843.

© Heidelberg University Library

Franz Stuck: Poster for the VII. International Art Exhibition in Munich, 1897

© Museum Villa Stuck

By the time Gustav Klimt painted his archaic Pallas Athene, the all-too-earthly allegory of Naked Truth, Nuda Veritas, and the painting Moving Water in 1898/99, he had already developed into a prominent exponent of Modernism. Within a short period of time, Klimt arrived at a “Secessionist” style in which he combined flatness, frontality, and golden luster with the subtle lightness of Post-Impressionist brushwork.

At the “II. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession” [“2nd Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists Secession”] in November 1898, Gustav Klimt presented, among other pieces, three recent works: Pallas Athene (1898, Wien Museum, Vienna), Moving Water (1898, private collection), and Portrait of Sonja Knips (1897/98, Belvedere, Vienna). All three paintings attracted attention, with Pallas Athene and Moving Water in particular provoking disapproval from almost all commentators.

Pallas Athene

The square-format painting, with its frame designed by Klimt himself, leaves no doubt whom it represents. Klimt had the name of the Greek goddess, “PALLAS ATHENE,” written in capital letters along the upper strip of the frame. In strict frontality, the figure presents herself as a defiant woman: she wears a shiny golden Greek helmet with a nose guard, a shimmering gorgoneion, and a scale cuirass (aegis) over a red chiton. With her left hand she leans on the shaft of a lance. In her right hand, Pallas Athene holds a small Nike supported on a sphere, prefigured in an illustration for Ver Sacrum (March 1898) and strikingly reminiscent of the painting Nuda Veritas (1899, Österreichisches Theatermuseum, Vienna), which would be completed the following year. Her mirror reflects the light like a bluish-white flash against the warm copper and reddish gold of the aegis. Behind Pallas Athena appear shadowy figures and a scaly animal. For this, Klimt borrowed from the painted decoration of a hydria by the Painter of Vatican G 43 (c. 530 BC, The Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio), which shows Hercules fighting Triton.

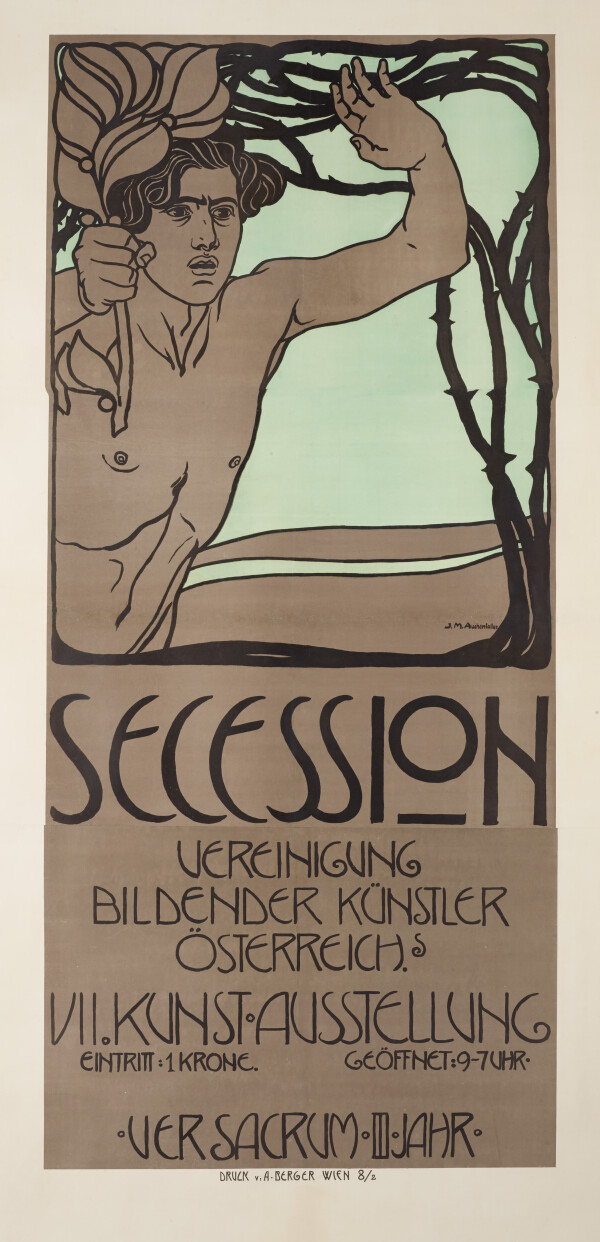

In the year before he painted Pallas Athena, Gustav Klimt had already chosen the combative patron goddess of the arts as a motif for the Vienna Secession’s first exhibition poster. He and his comrades-in-arms thus referred to the Munich Secession and its poster designed by Franz von Stuck. Stuck was well known in Vienna, having supplied designs for Martin Gerlach’s Allegorien und Embleme [“Allegories and Emblems”] (1882–1884). For the poster of the “VII. Internationale Kunstausstellung” [“7th International Art Exhibition”], the Munich Symbolist had conceived a depiction of Pallas Athene that was to anticipate the solution of Gustav Klimt’s painting in terms of form and content.

Moreover, if one compares Klimt’s depiction of Pallas Athene in the spandrel of the staircase of the k. k. Kunsthistorisches Hofmuseum (today’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), which is about eight years older, with the Wien Museum’s picture, the military and aloof appearance of the goddess in the later oil painting is striking.

Gustav Klimt: Greek Antiquity (Athena), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

© KHM-Museumsverband

In 1898, such contemporary sources as the magazine Kunst und Kunsthandwerk reported that contemporaries were shocked by the modernity of the goddess of wisdom’s artistic conception and treatment when the painting was first presented:

“Gustav Klimt is completely on that level with a series of new pictures, as little as they have been painted to please the general public (quite the contrary!). His much-discussed Pallas Athene in a golden helmet and cyan and golden scale aegis is a genuine Secessionist goddess, both the figure and its armor radiant with a distinctive poetry of color. This bold work, which ignores all traditions and follows only personal feeling, will continue to be memorable throughout the history of Viennese painting.”

Gustav Klimt: Moving Water, 1898, private collection

© Kallir Research Institute, New York

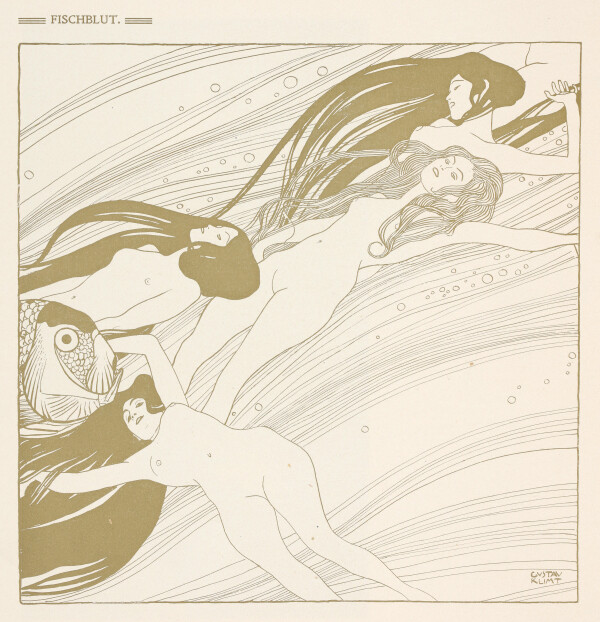

Gustav Klimt: Fish Blood, in: Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 3 (1898).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

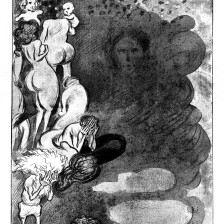

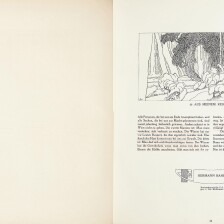

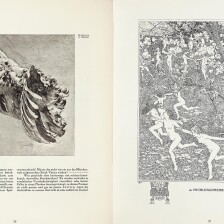

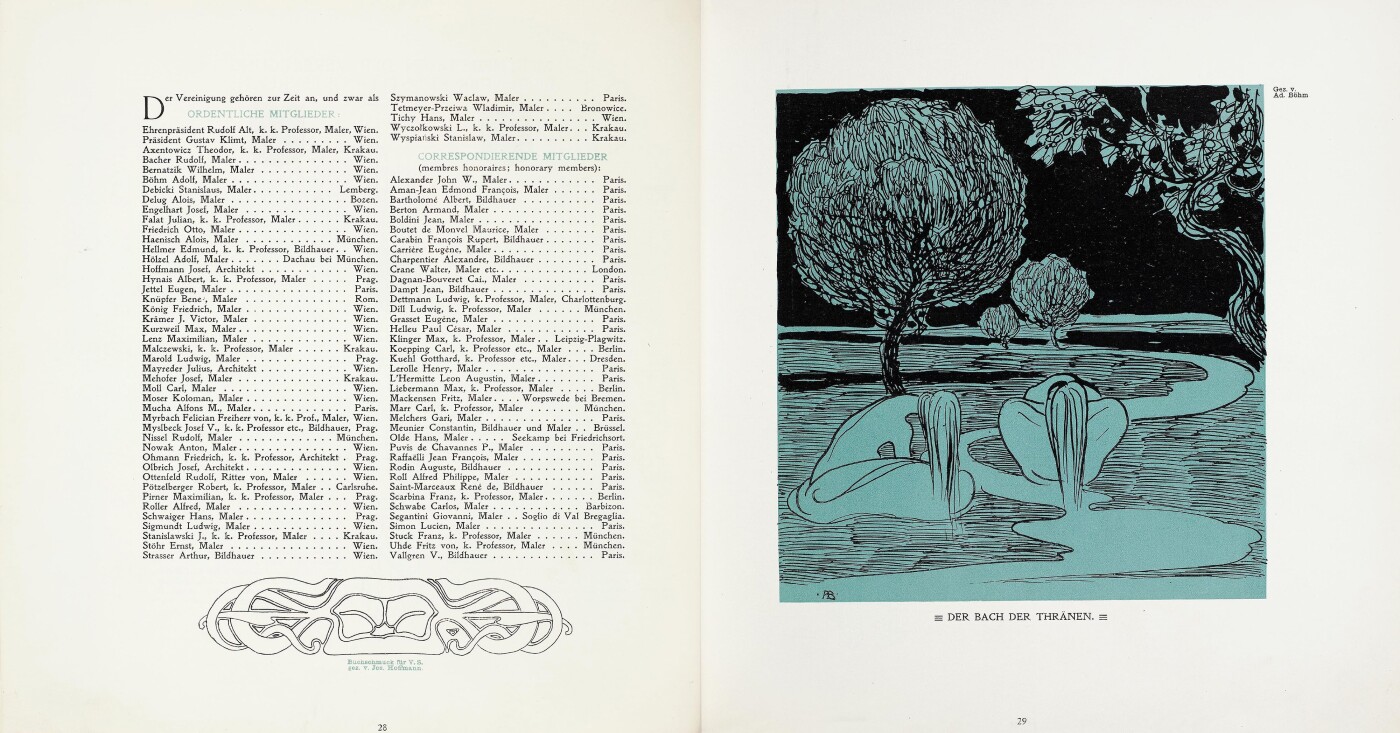

Moving Water

Between 1898 and 1907, Gustav Klimt painted a group of small Symbolist paintings depicting enchanted and mysterious underwater scenes. The work Moving Water, now in a private collection, might have been painted as early as the summer of 1898. It shows the bodies of five women in the nude moving diagonally across the picture plane. Given the title, their postures and hair, as well as the parallel blue and violet lines and the dimmed light, suggest that they could be swimming aquatic creatures. In the lower right corner, a bald creature with green shimmering eyes appears. This is exactly where Gustav Klimt placed his signature in bright red.

In this picture of nameless female creatures, Gustav Klimt revisited the concept of the Faculty Paintings. Today, more than 400 preliminary designs and sketches for the group of these ceiling paintings can still be traced. In them, the painter tried out motifs of human life coming into being, thriving, and perishing, which he visualized in the Faculty Paintings in the form of a rising tower of humans.

The pen and ink drawing The Blood of Fish (1898, private collection), which Klimt created for an issue of the art magazine Ver Sacrum, is also closely related to Moving Water, both compositionally and in terms of content. Conceived with a strong contrast of black and white, the drawing anticipates the procession of swimming and floating women. The scene can be identified as set under water through a large fish head and softly drawn lines and bubbles.

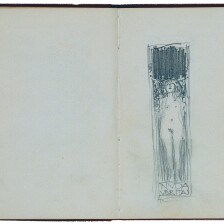

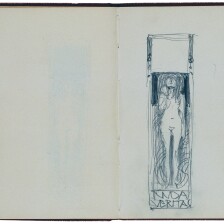

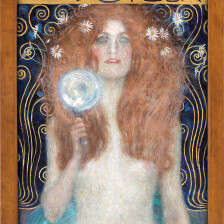

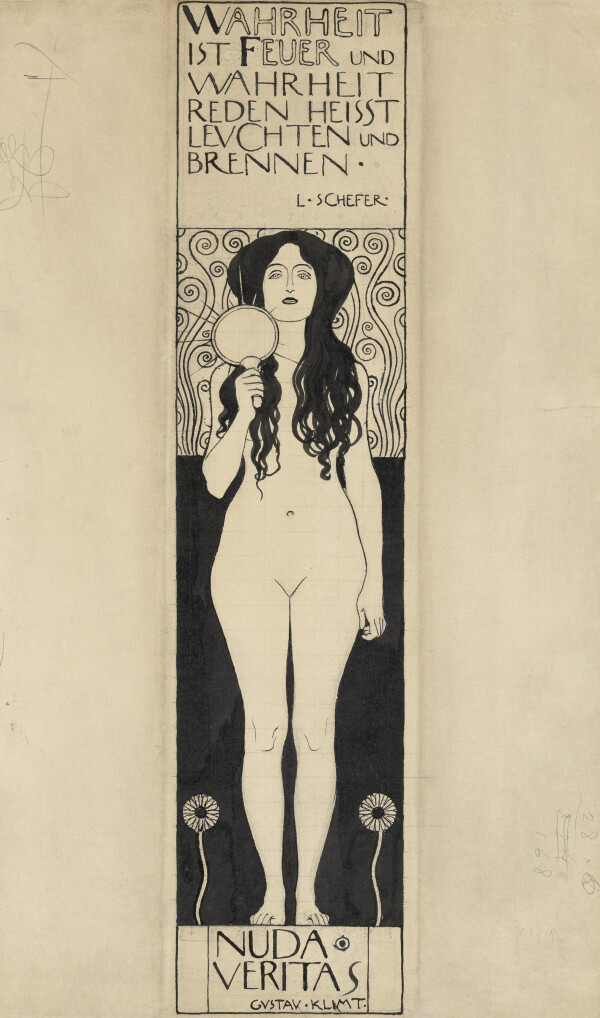

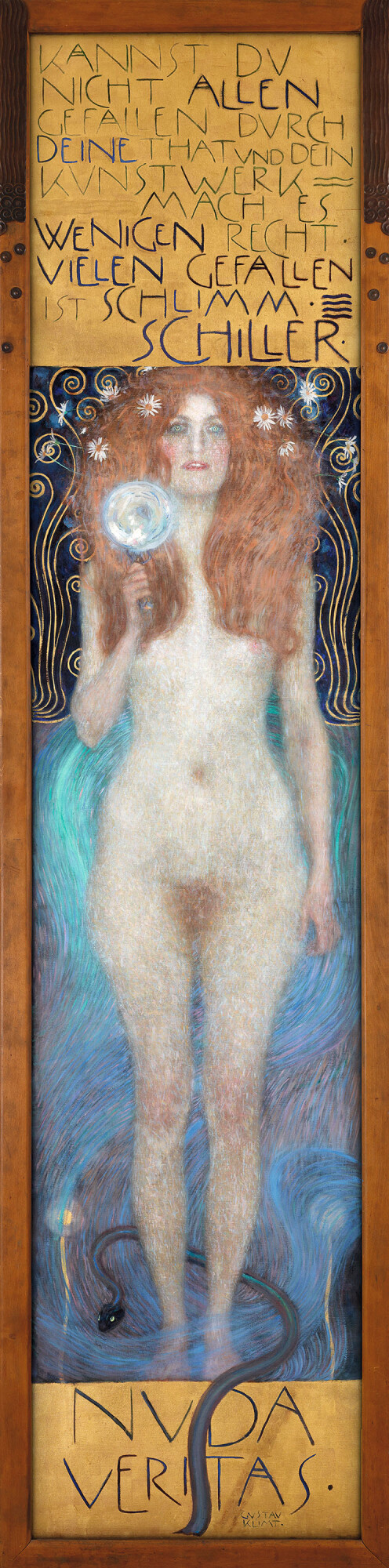

Nuda Veritas

One of Klimt’s most controversial works in 1899 was Nuda Veritas. Measuring 252 by 56.2 centimeters, this tall and narrow painting shows a nude young woman in strict frontality, her appearance stylistically reminiscent of the Belgian painter Fernand Khnopff. White daisies adorn her red mane of hair, and with her right hand she holds up a mirror reflecting the light. Blue and violet lines behind the figure of Naked Truth, the title of the painting translated into German, are interpreted as purifying water or veils. Being motifs borrowed from nature, the two flanking dandelion blossoms, the white flowers in the figure’s hair, and the ornamental lines forming spirals behind the head of Naked Truth are associated with the Secession’s spring symbolism.

Gustav Klimt: Nuda Veritas, 1899, Theatermuseum, Wien

© KHM-Museumsverband

Gustav Klimt: Nuda Veritas, 1898, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

An adder – possibly a reference to renewal – is wound around the legs of Naked Truth, as they rest firmly on a golden pedestal inscribed “NUDA VERITAS.” Above the head of Naked Truth appears the following phrase in capital letters:

“IF YOUR DEED AND YOUR ART DO NOT PLEASE EVERYONE, PLEASE ONLY A FEW. PLEASING EVERYONE IS FATAL. – SCHILLER.”

A year earlier, in 1898, Gustav Klimt made two ink drawings that are closely related to the painting Nuda Veritas. Envy and a first version of Nuda Veritas (both 1898, Wien Museum, Vienna) were reproduced in the third issue of the first annual volume of Ver Sacrum. Both personifications show the same compositional and formal solution. The figure of Envy appears as an aged woman in a Greek chiton, with the adder around her neck. By contrast, Klimt visualizes the personification of Naked Truth as a youthful woman – but still paired with a quotation by the German Romanticist Leopold Schefer.

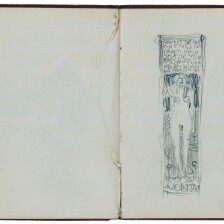

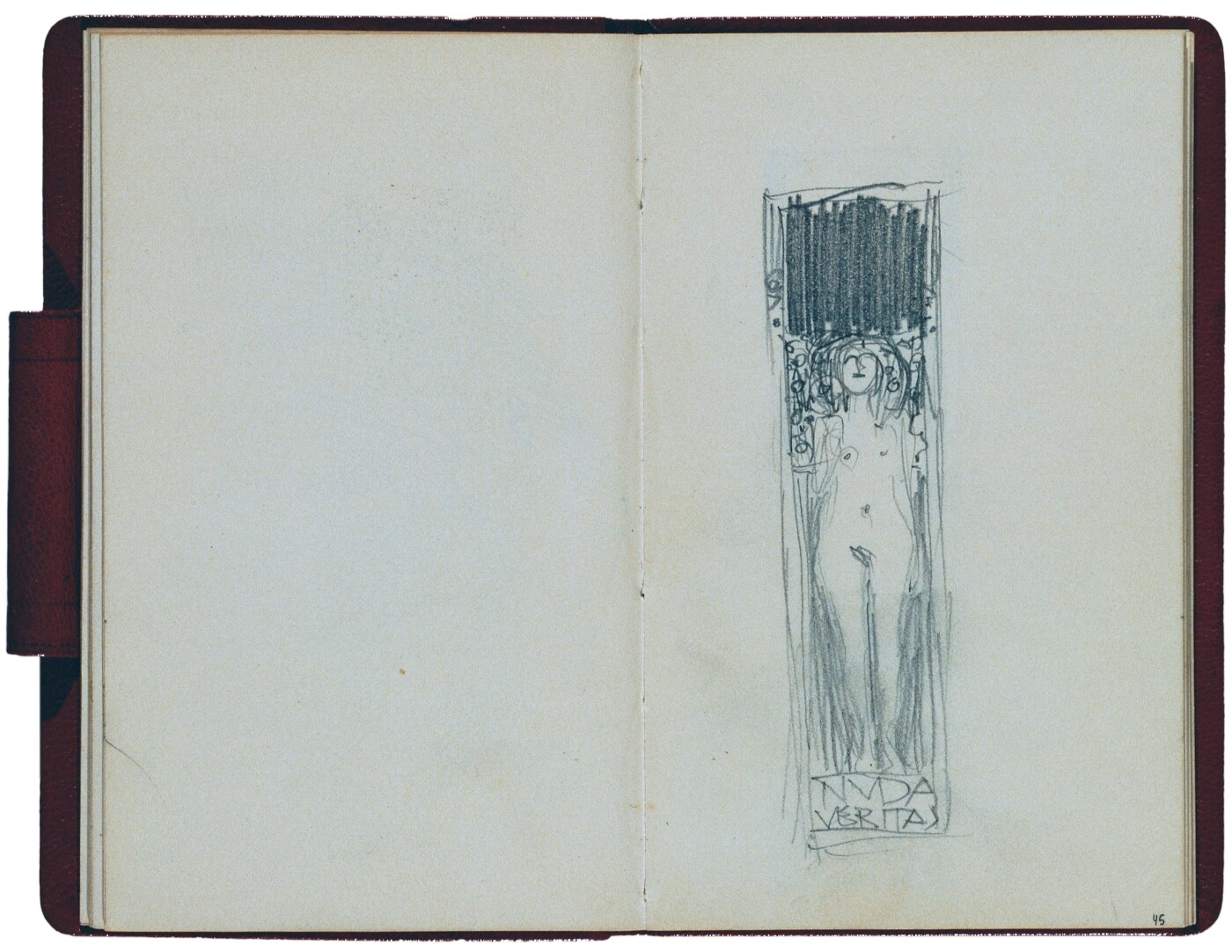

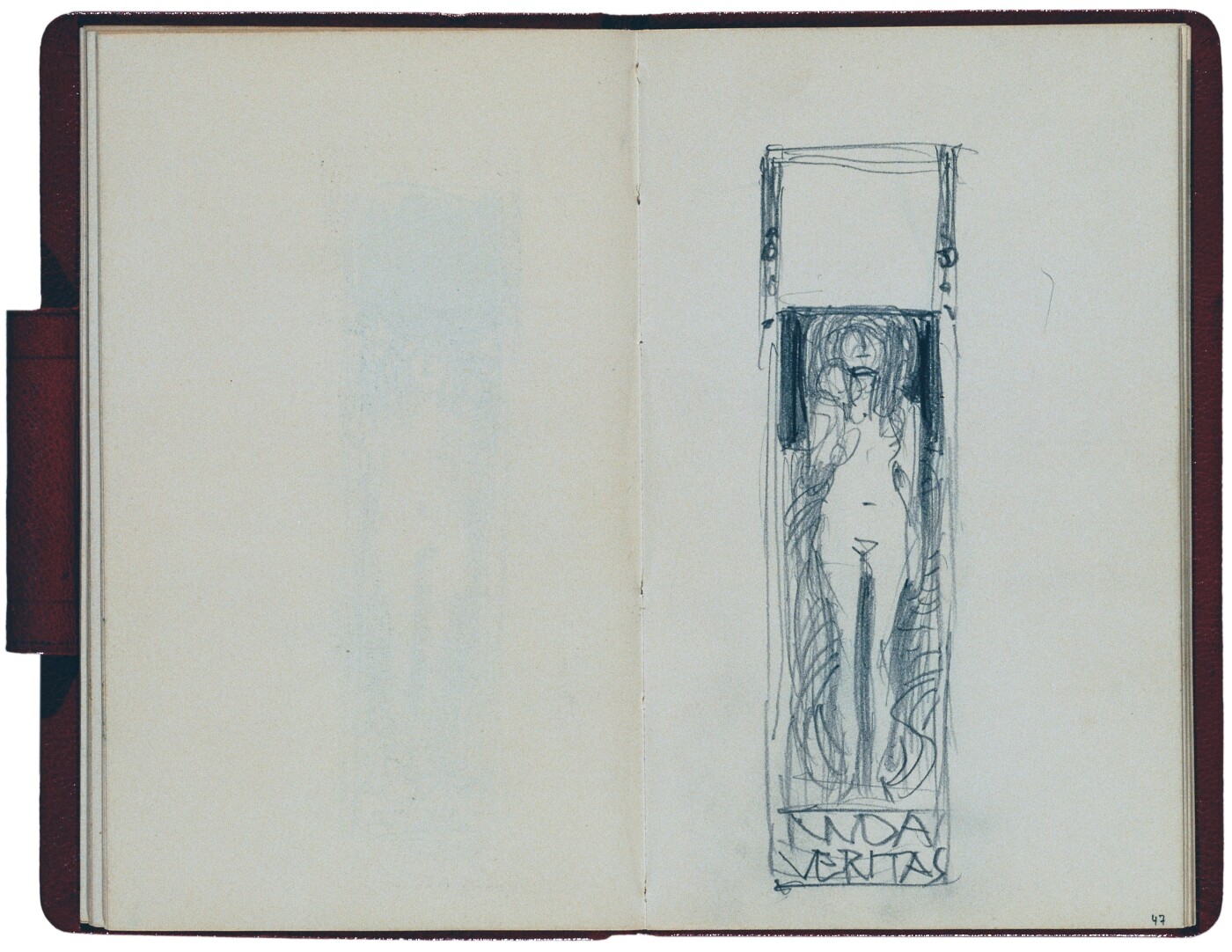

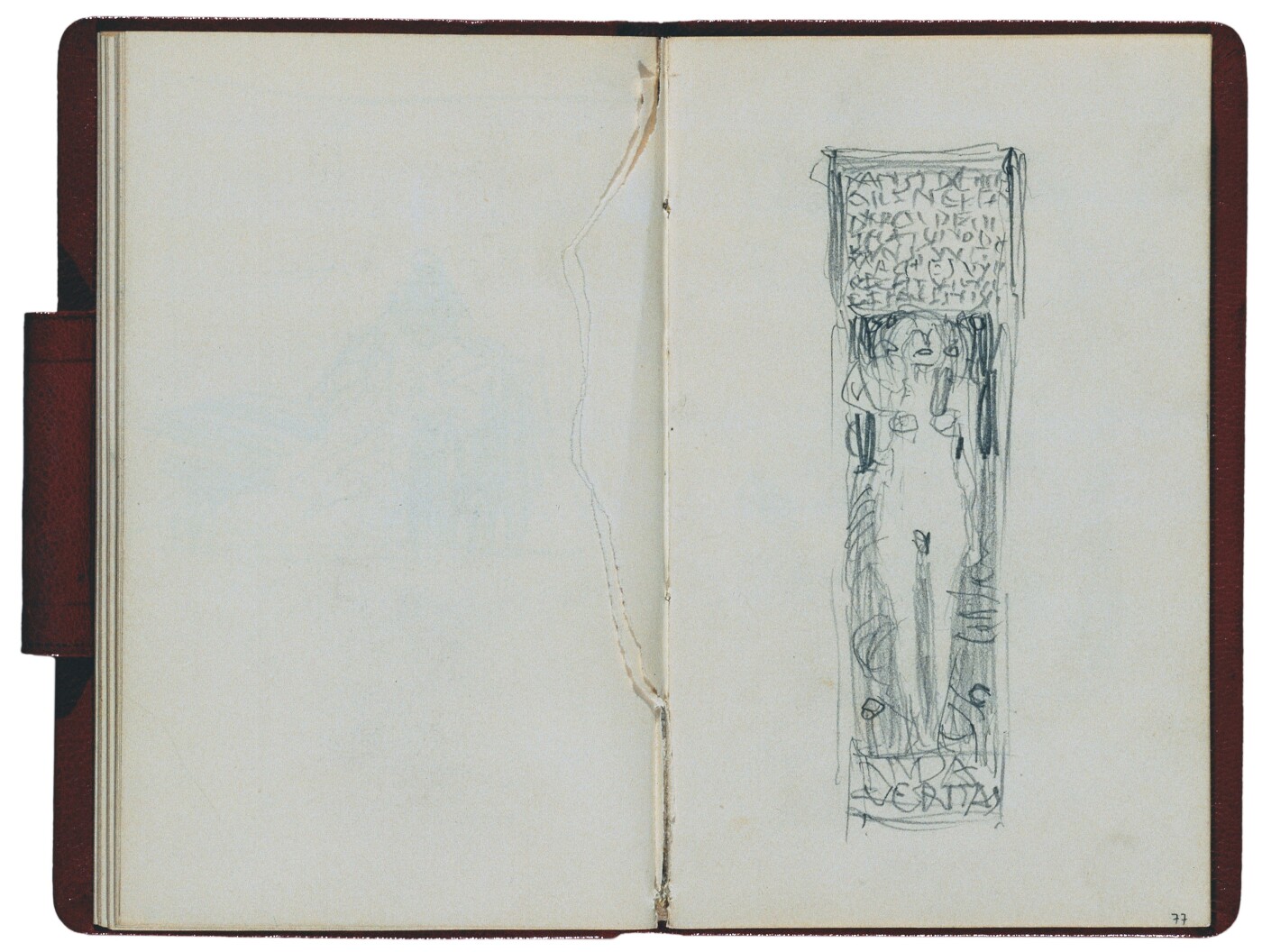

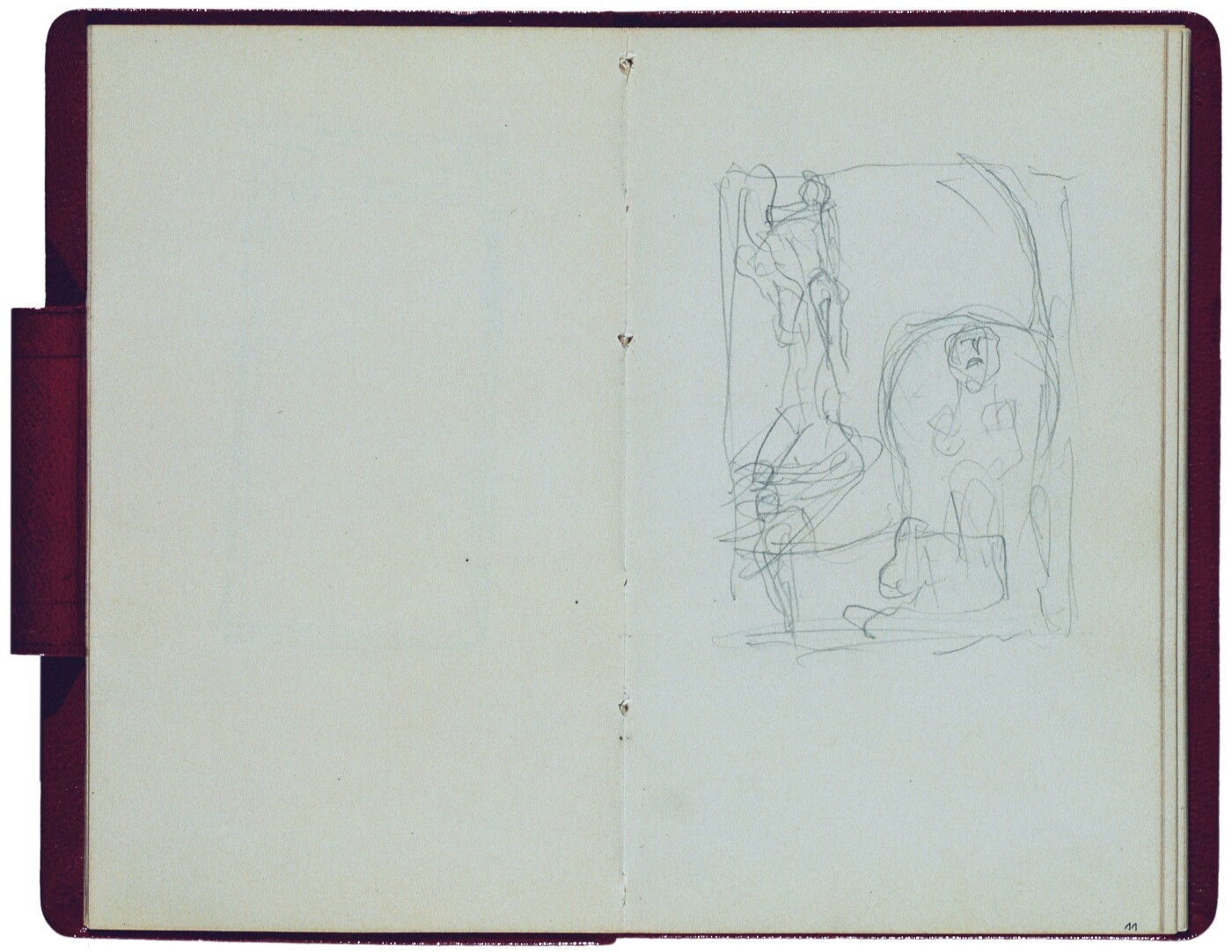

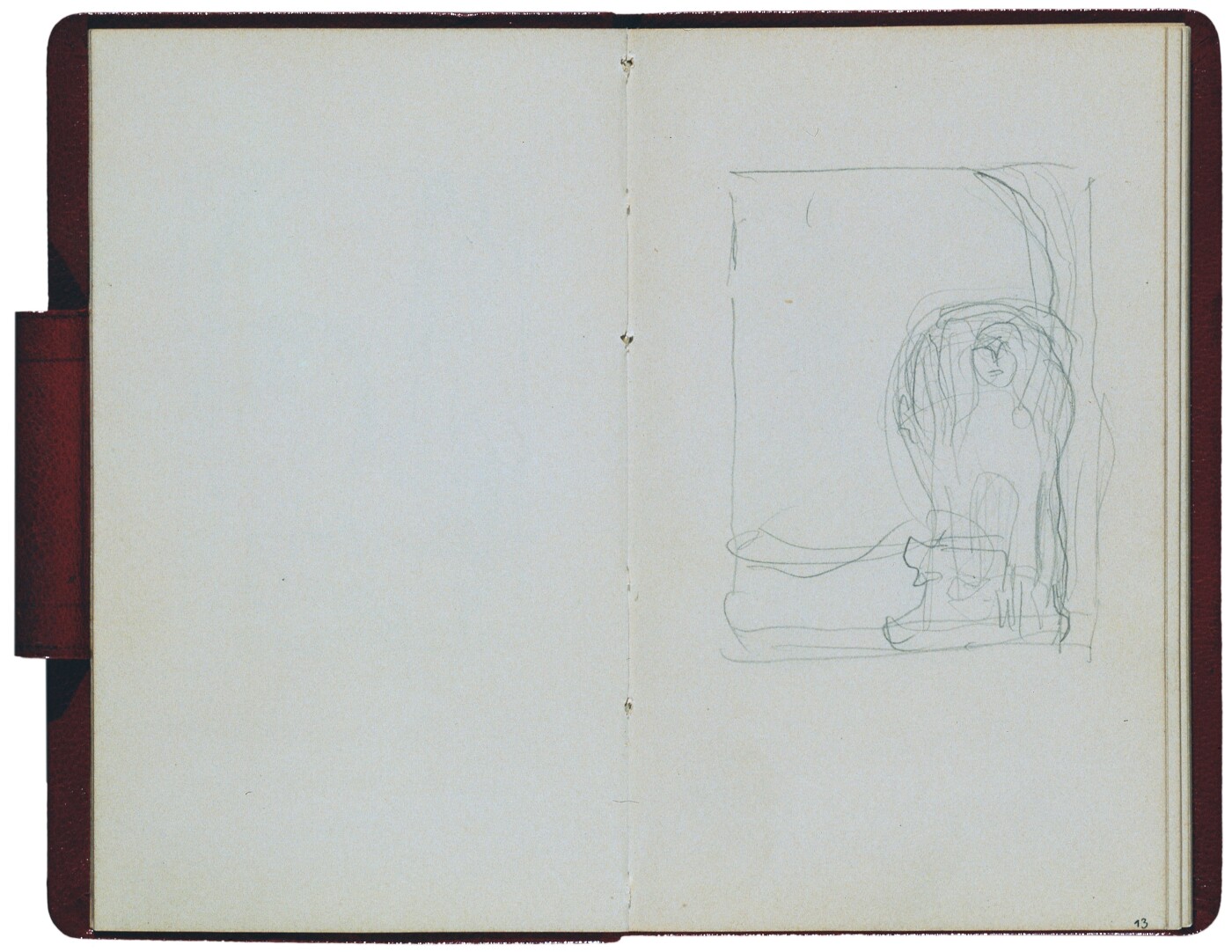

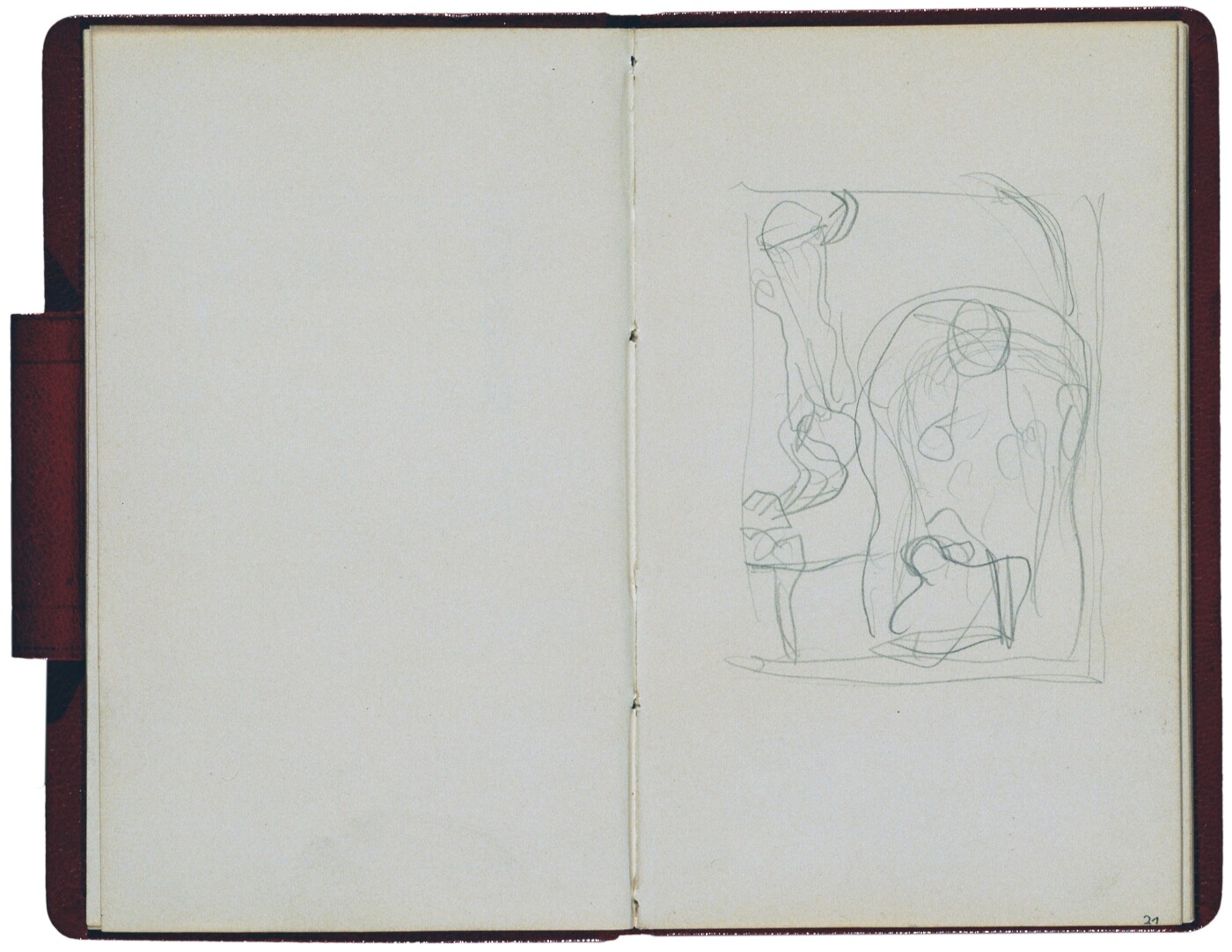

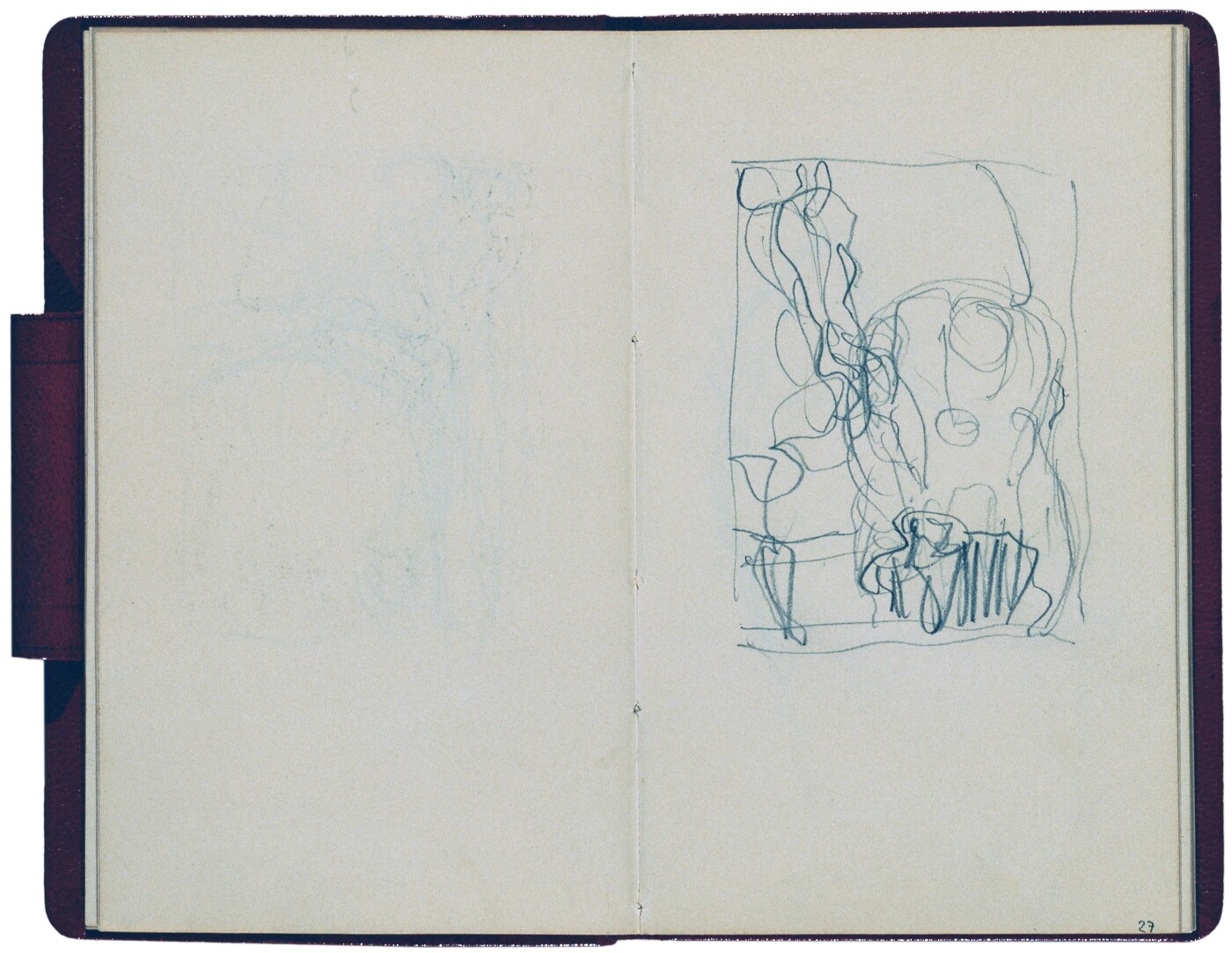

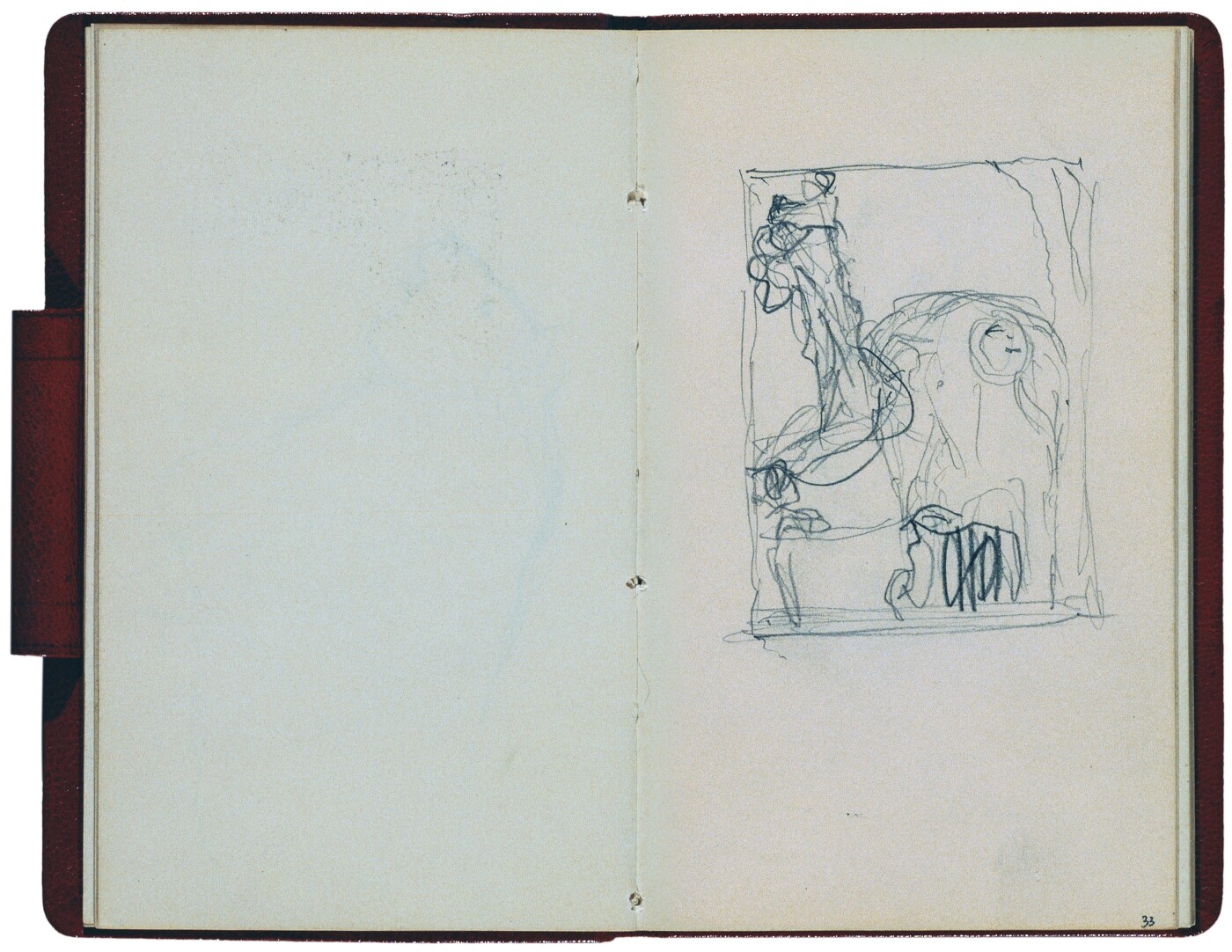

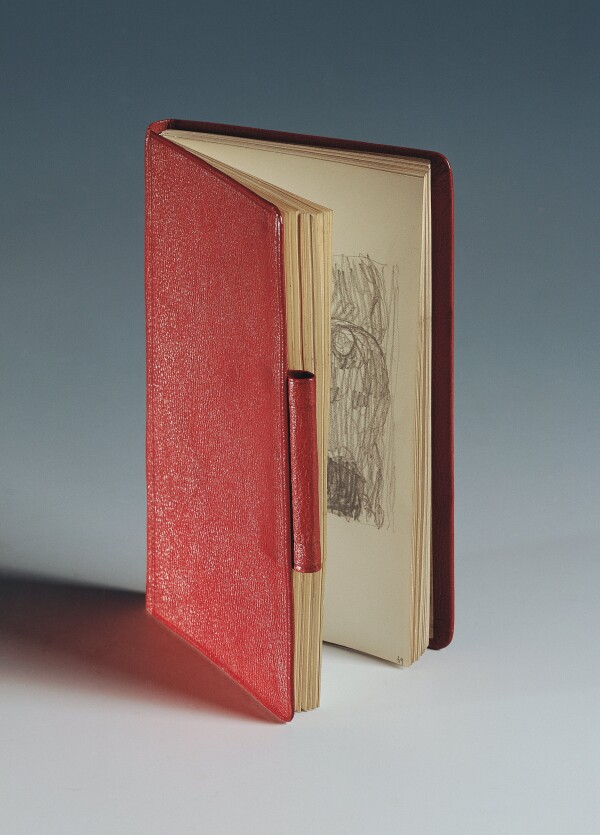

In a sketch to be dated between 1897 and 1899 and contained in the Red Sketchbook, a gift from Gustav Klimt to Sonja Knips now in the collection of the Belvedere in Vienna, the painter developed the composition further. He changed the type of woman, probably because Klimt wished to work more intensively with a living model in his painting.

Sketched Genesis of “Nuda Veritas”

-

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Nuda Veritas, 1899, Theatermuseum, Wien

Gustav Klimt: Nuda Veritas, 1899, Theatermuseum, Wien

© KHM-Museumsverband

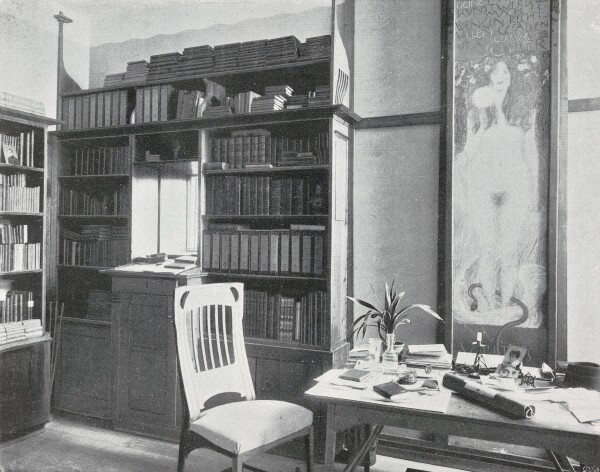

Bruno Reiffenstein (?): Insight into the Villa Bahr, circa 1901

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

The work, which was exhibited at the “IV. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession” [“4th Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists Secession”] (18 March to 31 May 1899), enraged the critics because of the overly slender girl’s body and her reddish cheeks. The prominent quotation from Friedrich Schiller above the sitter’s head was interpreted as an affront by the artist to his audience, which had previously been well disposed toward him but had drifted away in recent years. Klimt’s friend, the author Hermann Bahr, acquired the work and hung it in a special cabinet in the study of his villa.

Today, Nuda Veritas is considered the painting with which Gustav Klimt not only presented himself as an advocate of the concept of the freedom of art, but also ascribed to art a role significant from a socio-politically perspective. The Modernist artist saw himself as a member of a small circle of “chosen ones,” an artistic and social elite whose works were capable of revealing and conveying the truth – which is why Naked Truth holds up a mirror in the direction of the viewer so that one might discover one’s own image in the glaringly bright spot of light.

Literature and sources

- Gottfried Fliedl: Gustav Klimt 1862-1918. Die Welt in weiblicher Gestalt, Cologne 1998.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012.

- Toni Stoos, Christoph Doswald (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Ausst.-Kat., Kunsthaus Zurich (Zurich), 11.09.1992–13.12.1992, Stuttgart 1992.

- Ursula Storch (Hg.): Klimt. Die Sammlung des Wien Museums, Ausst.-Kat., Vienna Museum (Vienna), 16.05.2012–07.10.2012, Vienna 2012.

- Alice Strobl: Wasserbilder, in: Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007, S. 73-92.

- Ludwig Hevesi: Aus dem Wiener Kunstleben, in: Kunst und Kunsthandwerk. Monatsschrift des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie, 1. Jg., Heft 11-12 (1898), S. 409.

Modern Portraits

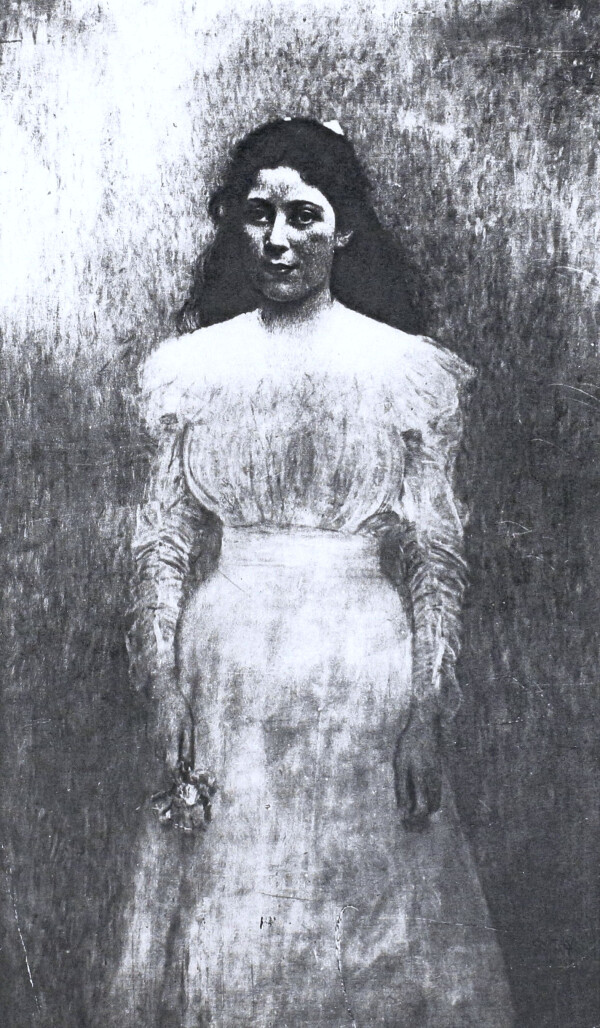

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Helene Klimt, 1898, Kunstmuseum Bern, Loan from a private collection

© Kunstmuseum Bern

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Sonja Knips, 1897/98, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Lady by the Fireplace (at Dusk), 1897/98, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Various Faces (Lady in an Armchair), 1897/98, private collection, courtesy of HomeArt

© Sotheby's

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Serena Lederer, 1899, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Trude Steiner, 1900, Verbleib unbekannt

© Gallery Welz Salzburg

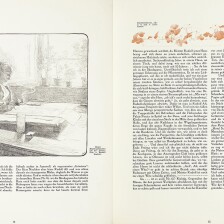

Gustav Klimt is known today as the author of impressive and monumental female portraits. But he only began to stand out in this genre at the age of thirty-six, with the portrait of Sonja Knips, followed by the painted likenesses of Serena Lederer and Trude Steiner, with which he increasingly established himself as the Painter of Women.

Before Gustav Klimt presented his large-sized Portrait of Sonja Knips (1897/98, Belvedere, Vienna) in the Vienna Secession’s second exhibition and thus appeared as both an important painter of stately portraits and a “modernist,” he turned to his own family.

Helene Klimt

In Portrait of Helene Klimt (1898, private collection) he depicted his niece, who was six years old at the time, in strict profile. He was the guardian of the daughter of his brother Ernst, who had died in 1892, and the latter’s wife, Helene. In the portrait the child resembles a young adult, as any clue as to her young age is erased by the hairstyle and clothing. The smooth, auburn hair is effectively set off against the light-colored background and the high-necked dress, with its colored accents in white and blue. Compared to this portrait of a child, the pastel from 1891, which either depicts her mother or the latter’s sister-in-law (private collection), gives a soft and atmospheric impression.

Around 1896 Gustav Klimt began to take an interest in the painted oeuvres of the Belgian Symbolist Fernand Khnopff and the British-American painter James McNeill Whistler, the portraiture of both of whom would make an impact on him. The Symbolist works helped him to handle such compositional problems as the placement of the figure within the picture space and achieve an atmospheric manner of painting.

Sonja Knips

The Portrait of Sonja Knips (1897/98, Belvedere, Vienna) ranks among Gustav Klimt’s most famous portraits. In what was his first painting of square format, measuring 145 by 146 centimeters, Klimt harked back to stylistic and compositional strategies he had already dealt with from about 1897 onwards in such small-sized oil paintings as Lady by the Fireplace (Dusk) (1897/98, Belvedere, Vienna), Portrait of a Lady in Profile to the Right (1897/98, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin, Ohio), and Various Faces (Lady in an Armchair) (1897/98, private collection). All of the portraits mentioned show women in strict profile to the right. The tonal coloring and the painting technique suggest the influence of James McNeill Whistler, recalling the latter’s atmospheric, blurring manner. Sonja Knips also faces toward the right, but the strict profile is moderated by the figure’s turning out of the picture. Contemporary reviewers already observed that one half of the picture had remained empty due to the asymmetrical composition. Through the vacant space the painter successfully achieved an exciting contrast between Sonja Knips in her light-colored dress and the diffusely rendered background. It thus seems impossible to locate the sitter in terms of the setting. Solely the white and red lilies above her head might be interpreted as view into a garden or winter garden.

The combination of the motifs of woman and flower was a common topos in the second half of the 19th century that had been introduced by Dante Gabriel Rosetti, among others. The sketchbook bound in red calfskin, which Klimt has put into her hand as a colored accent or indicator of her role as patroness and close friend, now belongs to the collection of the Belvedere in Vienna. As was already observed by his friend Ludwig Hevesi in 1903, by painting Sonja Knips Gustav Klimt created “the first of his modern female portraits.” The narrow frame, the molding of which was fabricated by the metal sculptor Georg Klimt, Gustav Klimt’s second brother, is based on the concept of a Gesamtkunstwerk or total work of art. One of the chararcteristic features of the “modern” approach to portraiture is the empty surface, which took aback many a reviewer, including Carl Schreder of the Deutsches Volksblatt:

“As far as the head goes, this is a very good portrait of a lady, but the treatment of the hands and the dress seem a bit too negligent, and what is more: why this deliberate placement of the figure to the right side of the picture while leaving the left side empty?”

Serena Lederer

With his Portrait of Serena Lederer (1899, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), Gustav Klimt painted the likeness of one of his most loyal devotees. Klimt had already immortalized the twenty-six-year-old art collector and wife of the industrial tycoon August Lederer in the watercolor Auditorium of the Old Burgtheater (1888, Wien Museum, Vienna). The painting, which was executed in 1899 and presented in 1901 at the Vienna Secession’s “X. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession” [“10th Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists Secession”] shows Serena Lederer as an upright standing figure in a white dress against a white backdrop. Her dark, curly hair, the thick eyebrows, and the black outlined eyes form a vivid contrast. Klimt obviously knew from the very outset that he wished to depict Serena Lederer standing, for the sitter appears like that in all of the surviving drawings.

What strikes one about these preliminary studies is above all the flowing, rhythmical line with which Gustav Klimt sought to capture the drapery. The pose and most of all the high-waisted style of the dress are reminiscent of contemporary fashion photography, which may have served as an inspiration for Klimt in addition to examples of stately portraiture of the past decades. Compared to the transfer sketch (Albertina, Vienna), it becomes obvious that the sweep of the train must have been altered at the very last moment, as it now appears more dynamic. The dress, painted in light blue and white, encloses Serena Lederer’s body without it becoming visible. Using the robe, Klimt suggests a twist of the sitter’s figure, similar to Portrait of Sonja Knips.

When Portrait of Serena Lederer was presented at the “X. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession,” it successfully convinced Friedrich Stern, critic of the Neues Wiener Tagblatt, with its “most delicate coloristic effect.” However, the reviewer mocked the “made-up cheeks,” which he had already felt to be completely out of place in Klimt’s Nuda Veritas. As a consequence, August Lederer refused any further exhibition of portraits of family members, which is why Portrait of Serena Lederer was presented in public only once during Gustav Klimt’s lifetime.

Over more than twenty years, Serena Lederer compiled the largest collection of Klimt’s works in Vienna: following her own portrait, she also commissioned the venerated painter with the portraits of her daughter and her mother, Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer (1914–1916, private collection) and Portrait of Charlotte Pulitzer (1917, unknown whereabouts, lost since 1945).

Trude Steiner

In the years 1900 and 1901, Gustav Klimt was asked twice to portray departed members of the family. Portrait of Hermann Flöge sen. on His Deathbed (1899/1900, Belvedere, Vienna) follows the type of realistic depiction of a deceased person while laid out. Portrait of Trude Steiner (1900, unknown whereabouts), on the other hand, suggests that the daughter of Jenny Steiner, who died at the age of thirteen, was still immortalized during her lifetime. The three-quarter-length portrait, which has been considered lost since World War II, features a composition that is similar to that of the painted likeness of Serena Pulitzer Lederer. Trude Steiner is shown standing and en face in a white dress against a light-colored backdrop, her dark hair set off against the atmospherically rendered setting. A bouquet of flowers in her right hand and her hair, which is held together by a bow but nevertheless falls over her shoulders, emphasize the sitter’s youth. In terms of both composition and coloring, the picture resembles James McNeill Whistler’s Symphony in White No. 1: The White Girl (1862, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.), which before 1906, however, Klimt could only have known from reproductions in black and white.

Literature and sources

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012.

- Fritz Novotny, Johannes Dobai (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Salzburg 1975.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007.

- Tobias G. Natter, Gerbert Frodl (Hg.): Klimt und die Frauen, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 20.09.2000–07.01.2001, Cologne 2000.

- Ludwig Hevesi: Acht Jahre Sezession (März 1897–Juni 1905). Kritik – Polemik – Chronik, Vienna 1906.

- Friedrich Stern: Die Ausstellungssaison, in: Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 16.03.1901.

- Carl Schreder: Zweite Kunstausstellung der Wiener Secession, in: Deutsches Volksblatt (Morgenausgabe), 19.11.1898, S. 1-3.

- Tobias G. Natter: Klimt and Szerena Lederer. Identity and Contradictory Realities of great Art, in: Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Klimt and the Women of Vienna's Golden Age. 1900–1918, Ausst.-Kat., New Gallery New York (New York), 22.09.2016–16.01.2017, London - New York 2016, S. 34-55.

- Catherine Dean: Klimt, New York 1996.

- Ludwig Hevesi: Feuilleton. Eine Klimt-Ausstellung (Sezession), in: Pester Lloyd, 18.11.1903, S. 2.

- Marian Bisanz-Prakken: Im Antlitz des Todes, Gustav Klimts ‚Alter Mann auf dem Totenbett‘. Ein Porträt Hermann Flöges?“, in: Österreichische Galerie Belvedere (Hg.): Belvedere. Zeitschrift für Bildende Kunst, Heft 1 (1996), S. 20-39.

- Marian Bisanz-Prakken: Gustav Klimt. Alter Mann auf dem Totenbett, in: Gerbert Frodl, Michael Krapf (Hg.): Neuerwerbungen: Österreichische Galerie Belvedere 1992-1999 : Meister von Heiligenkreuz bis Elke Krystufek, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 15.09.1999–21.11.1999, Vienna 1999.

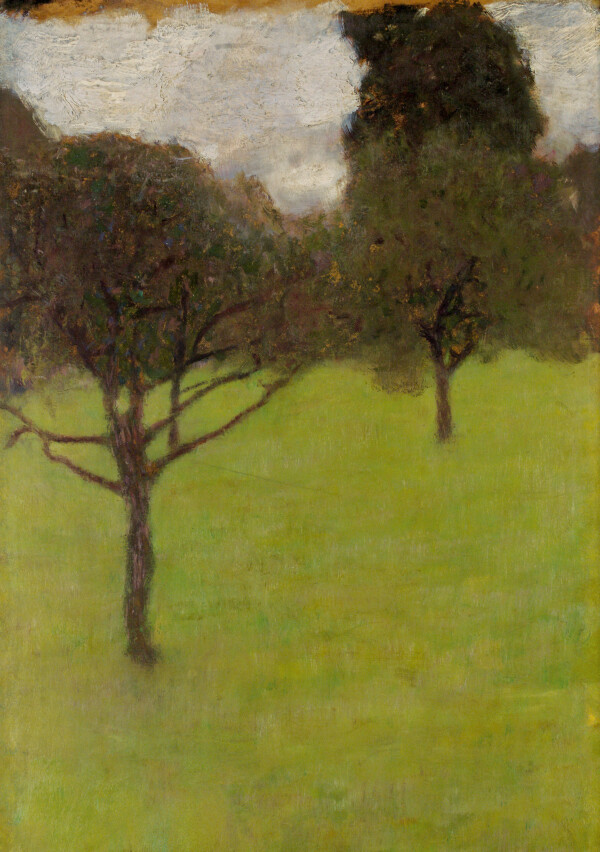

First Landscapes

Gustav Klimt: After the Rain (Garden with Chickens in St. Agatha), 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Orchard, circa 1898, private collection

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

From 1897, Klimt continuously worked in the genre of landscape painting. While his initial landscapes were committed to the style of Atmospheric Realism, his later works from the late 19th century onwards were increasingly influenced by Impressionism and Symbolism.

The first nature studies Klimt executed in 1881/82 were still wholly committed to the style of Atmospheric Realism which was prevalent in Austria at the time. After a ten-year gap, during which there are no known landscapes in Klimt’s oeuvre, the artist focused on depictions of cottage gardens. Most of these works were created during his summer sojourns, in 1897 in Fieberbrunn in Tyrol, and in 1898 in St. Agatha in Upper Austria.

The landscape The Crab Apple Tree (1897, whereabouts unknown), which Klimt likely created in 1897 in Fieberbrunn, is now lost. We can thus only speculate about its appearance. Hevesi described the painting as a small landscape study in which “each branchlet has its own sentiment,” and further as a twilight atmosphere of gray and green. What is certain is that the painting was named after the depicted summer apple variety – crab apple – with its characteristically green color. Klimt’s paintings created over the following years increasingly reflected his tendency towards Symbolist atmospheric landscapes.

The privately owned depiction Farmhouse with Roses (1897/98, private collection), which shows the north-eastern facade of a smithy in St. Agatha, is known to us only from a black-and-white photograph. Klimt summered there in 1898 together with the Flöge family. Along with After the Rain (Garden with Chickens in St. Agatha) (1898, Belvedere, Vienna), the painting executed on board Orchard (1898, private collection) and Orchard in the Evening (1898, private collection), it is one of the few landscapes that Klimt created in a narrow portrait format.

In their atmospheric, shimmering blurriness, the orchard landscapes created in 1897/98 show distinct parallels with the works of Fernand Khnopff – whose paintings were shown at the “I. Kunst-Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs” [“1st Exhibition of the Vienna Secession”] in 1898 – as well as with the shots taken by the art photographer Heinrich Kühne. The open brushwork is reminiscent of Impressionist and Pointillist painting. The phenomenon of color reduction during twilight hours depicted in Orchard in the Evening was especially suitable to convey a mysterious atmosphere. In all his landscapes from this period, Klimt focused on the interplay of light and shadows, and the resulting contrasting color fields, while perspective and spatial depth became less and less important.

While Klimt oriented himself on the innovations of Symbolism and Impressionism in his manner of painting, his formats, which were unusual for Austrian landscape painting, and his high horizons were likely derived from Japanese painting traditions. We know that Klimt took a keen interest in Japanese art, especially in woodcuts. The horizon line, which the artist placed in the upper third of his depictions, served to heighten his increasingly planar, one-dimensional landscape renderings. Klimt would continue to elaborate this carpet-like, almost ornamental concept of nature in his later depictions of cottage gardens.

Gustav Klimt: A Morning by the Pond, 1899, Leopold Museum

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

Klimt’s First Square Landscapes

Klimt’s summer sojourn in Golling near Hallein in 1899, which he spent together with the Flöge family, afforded the artist further opportunities for landscapes and animal depictions. Along with the landscape A Morning by the Pond (1899, Leopold Museum, Vienna), which shows the Egelsee in the early morning, Klimt also painted the work Cows in the Stable (1899, Lentos Kunstmuseum, Linz). Both paintings are among the first examples of nature depictions Klimt created in a square format – the format he would use for all his subsequent landscapes. As documented by a Klimt autograph, the artist searched for these square image sections with the help of a “viewfinder” – a piece of cardboard with a cut out viewing panel.

A Morning by the Pond was the first in a series of landscapes in which Klimt explored the effects of reflections on the water. Once again, the artist placed the horizon close to the upper edge of the painting. His preference for an illusionary depiction of the world through reflections underscores Klimt’s rejection of a naturalistic rendering of reality. While Khnopff had emerged as Klimt’s role model already in previous years, it is blatantly obvious that the Belgian artist’s 1894 painting Still Water. The Ménil Pond (1894, Belvedere, Vienna) served as the direct compositional model for A Morning by the Pond. Claude Monet, too, specialized in such illusionary renderings of nature. It is highly likely that Klimt adopted the idea of a square image format from the French artist, much like the hazy brushstrokes with which he depicted the waves.

Fernand Khnopff: Unmoved Water. The Pond of Menil, 1894, Belvedere, Vienna

© Belvedere, Vienna

At the “VII. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession” [“7th Exhibition of the Vienna Secession”] (1900), Klimt presented not only his Faculty Painting Philosophy but also his landscapes from the two previous years. While the painting for Vienna University caused an art scandal, the Ministry of Culture and Education acquired the work After the Rain (Garden with Chickens in St. Agatha), proving that, despite his controversial modern allegories, Klimt was still highly esteemed as a landscape artist.

Gustav Klimt: The Black Bull, 1900, private collection

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: On the Attersee, 1900, Leopold Museum

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

Inspiring Attersee

When Gustav Klimt spent his first summer on the Attersee in 1900 at the invitation of the Paulick family, he created four landscapes and the animal depiction The Black Bull (1900, private collection). Klimt took lodgings at Litzlberg Brewery, and painted his landscapes in the house’s environs. Again, the compositions are dominated by high horizon lines and Impressionist, planar landscape carpets of splendid colors.

In his painting The Marshy Pond (1900, private collection), Klimt captured an oneiric landscape, situated between Symbolism and Impressionism, similar to A Morning by the Pond created a year earlier. The focus was once more on rendering the reflections of the surroundings on the water’s surface.

In his work On the Attersee (1900, Leopold Museum, Vienna), by contrast, Klimt was not interested in reflections of the surroundings but in the oscillating, shimmering colors and quality of the water. He rendered the turquoise waves of the Attersee in an almost Pointillist manner by placing short brushstrokes onto the silver, reflecting water surface. The depiction of the water as an animated color field takes up nearly the entire image space. Hevesi described the painting as follows: “A frame full of lake water, of the Attersee, nothing but short gray and green waves, flowing into each other.”

In his work Farmhouse with Birch Trees (1900, private collection), showing individual tree trunks within a green, planar meadow, Klimt made formal recourses to his earlier depiction After the Rain (Garden with Chickens in St. Agatha).

It wasn’t until the painting The Large Poplar I (1900, Neue Galerie New York, Estée Lauder Collection) that Klimt began to lower his horizon lines and to explore cloud-covered skies. The almost portrait-like staging of individual plants, which is already palpable in his poplar depiction, would come into full bloom eight years later in his painting The Sunflower (1907/08, Belvedere, Vienna), which, with its figural flower interpretation, is believed to be a landscape portrait of Emilie Flöge.

Further contents

Literature and sources

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt 150 Jahre, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 13.07.2012–27.01.2013, Vienna 2012.

- Tobias G. Natter, Elisabeth Leopold (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Sammlung im Leopold Museum, Vienna 2013.

- Sandra Tretter, Hans-Peter Wipplinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Jahrhundertkünstler, Ausst.-Kat., Leopold Museum (Vienna), 22.06.2018–04.11.2018, Vienna 2018.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2017.

- Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl: Treffpunkt Villa Paulick, in: Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sommerfrische am Attersee 1900-1916, Vienna 2015, S. 14-17.

- Alexandra Matzner: Gemalte Gärten. Gustav Klimt und das Gartenbild der Jahrhundertwende, in: Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Florale Welten, Vienna 2019.

- Ludwig Hevesi: Acht Jahre Sezession (März 1897–Juni 1905). Kritik – Polemik – Chronik, Vienna 1906, S. 235.

- Brief von Gustav Klimt am Attersee an Maria Zimmermann in Wien, mit skizziertem Motivsucher (um den 03.08.1902). S64/17.

- Stephan Koja: Die Sommer in Litzlberg, in: Stephan Koja (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Landschaften, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 23.10.2002–23.02.2003, Munich 2002, S. 64-70.

- Ostdeutsche Rundschau, 13.03.1900, S. 7.

- Ostdeutsche Rundschau, 15.03.1900, S. 8.

- N. N.: Kunst=Ausstellung, in: Wiener Zeitung, 15.03.1900, S. 8.

Faculty Paintings. Philosophy

Gustav Klimt: Philosophy (Study), 1898, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

© Gallery Welz Salzburg

The Faculty Painting Philosophy marks Gustav Klimt’s final break with academic traditions in favor of Symbolism. The painting’s first exhibition in 1900 caused a scandal. Following numerous alterations and additions, which were carried out until 1907, the work was destroyed in a fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945.

Genesis of a Monumental Work

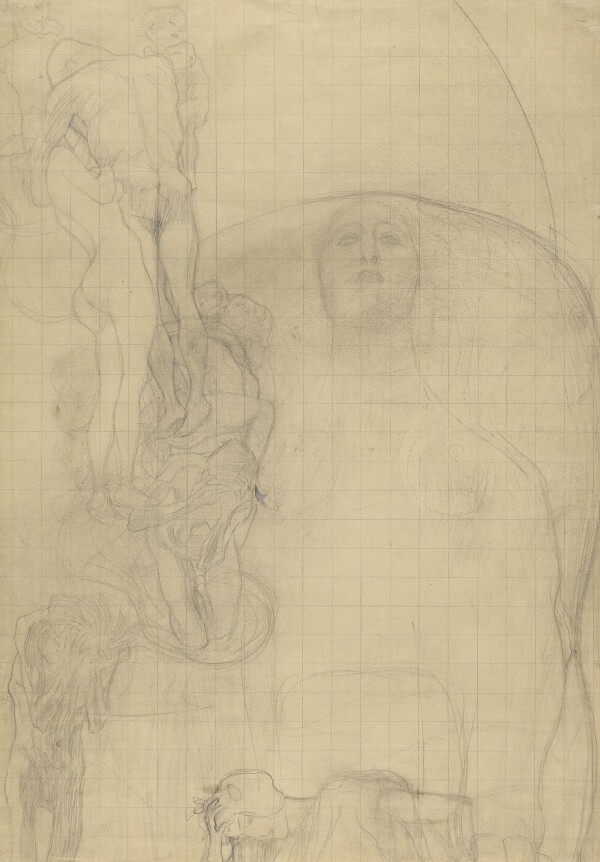

Ever since receiving the commission in 1894, Klimt had been creating preparatory sketches and studies for the ceiling paintings for the ceremonial hall of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, but he intensified his work especially from 1897 and 1898 onwards. One of the artist’s pads, known as the sketchbook of Sonja Knips, contains around 26 extant compositional sketches which can be ascribed to the Faculty Painting Philosophy (1900–1907, destroyed in a fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945). There are also several surviving sketches for the painted draft for Jurisprudence (1897/98, destroyed in a fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945) and Medicine (1900–1907, destroyed in a fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945).

Along with numerous individual studies and compositional sketches, the artist further created drafts painted in oil, which were examined on 26 May 1898 in an “art committee meeting” held by the academic senate, the artistic committee of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna and the Imperial-Royal Ministry of Culture and Education. Prior to this examination, the March issue of Ver Sacrum had printed a reproduction with the title “Draft for a Ceiling Painting ‘Hygiea’.” While the painted draft for Medicine has survived (1898, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem), those for Jurisprudence and Philosophy were lost in a fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945, and are known only from photographs.

Gustav Klimt: Seated woman. Study for the oil sketch for "Die Philosophie", 1897/98, The Albertina Museum

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

At the meeting, Franz Matsch’s designs for the ceiling paintings The Triumph of Light over Darkness and Theology were accepted, while Klimt’s drafts raised several objections. One of the suggestions was for Philosophy to be brighter and rendered more clearly. Especially important was the request for Matsch and Klimt to work more closely together so that the overall effect of the ceiling program would be more harmonious. Resentful of the objections, Klimt wanted to withdraw from the commission, but eventually agreed to the alterations on 3 June 1898, provided that his “artistic freedom” be “respected.” The Ministry of Culture and Education consequently informed Matsch and Klimt of their approval and the payment of the contractually agreed second instalment of their fees on the condition “[…] that the wishes expressed by these two committees [!] be taken into consideration […].”

Seeing as the process of creation of the paintings extended over a long period of time, Klimt’s comprehensive alterations and additions to the Faculty Paintings reflect his artistic development towards Symbolism. In his studies for the personification of knowledge (1897/98, Albertina, Vienna, S 1980: 455; 1897/98, Wien Museum, S 1980: 456), which he placed into the lower right corner of the painted draft for Philosophy, Klimt was likely inspired by Auguste Rodin’s famous work The Thinker (1880/82). Above the figure, we see two heads belonging to a four-headed sphinx, which was probably informed by a marble sculpture (2nd century AD) from the collection of antiquities of the Imperial-Royal Court Museum of Art History (now Kunsthistorisches Museum), which Klimt also depicted in his supraporte painting Music (1897/98, destroyed in a fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945) for Palais Dumba. Klimt positioned a barely visible philosopher opposite the personification of knowledge, while he placed a couple floating skywards above it. This interpretation of the faculty prompted the commissioners’ above-mentioned change requests.

Individual Pages from the Red Sketchbook

-

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: The philosophy (transfer sketch), 1900, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Moriz Nähr: The philosophy, circa 1900, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

In his transfer sketch for Philosophy (1900, Wien Museum, S 1980: 477) from around 1899, Klimt developed the composition further. He moved the severely cropped figure of knowledge into the center of the lower picture margin, thus afforded considerably more space to the sphinx depicted from below, and consolidated the stream of people with the addition of further nude figures. The journalist Alfred Deutsch-German visited Klimt in September 1899 in his studio on Josefstädter Straße and described the work as follows:

“He just started a pencil sketch of Philosophy. A tangle of strokes, which fails to reveal a solid shape, it appears baffling to the viewer. An explanation is needed. A vague Mother Nature emerges behind the globe within the hazy azure of twilight. The birth and passing of mankind, the transience of being, is hinted at with allegorical figures. Below this apparition, the artist rendered a firm and tangible personification of knowledge sitting in an armchair.”

The Realization of Philosophy. First Version

As the ceiling of Klimt’s studio at Josefstädter Straße 21 was not high enough to accommodate the Faculty Paintings, which measured 4.3 x 3 meters, he temporarily rented an additional studio. It was situated at nearby Florianigasse 54 on the 4th floor of the joinery and furniture factory Ludwig Schmitt.

Klimt worked on the first version of the Faculty Painting Philosophy until its first public presentation in March 1900 at the “VII. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession” [“7th Exhibition of the Vienna Secession”]. In the first edition of the accompanying catalogue, the painting was described as follows:

“Philosophy. One of the five allegorical ceiling paintings for the university’s auditorium. Left group of figures: the creation, fertile existence, passing away. Right: the globe, the mystery of the world. An enlightened figure emerging below: knowledge.”

A reproduction of this version of the painting, photographed by Moriz Nähr, was printed in 1900 in Ver Sacrum. In contrast to the painted draft and transfer sketch, the executed work shows the figure of knowledge as an illuminated head which appears in the lower picture margin and looks out of the depiction in rigid frontality. The stream of people in the left area of the painting consists of nudes of various ages shown in different poses. The sphinx emerges from a nebulous sphere which contemporaries described as a “blurry, oscillating, purple-green universe.” The color accents, which appear white in the black-and-white photograph, were gold-plated stars in the original. In Greek mythology, the sphinx was considered a demon of disaster and destruction. In their works of the 1890s, the European Symbolists often used it to visualize mysteriousness. With his sphinx as a symbol of the “mystery of the world,” Klimt thus followed in the tradition of eminent contemporaries, including Fernand Khnopff and Jan Toorop, whose works were familiar to him from exhibitions and art magazines.

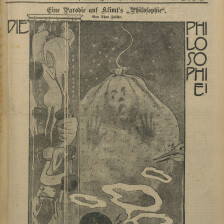

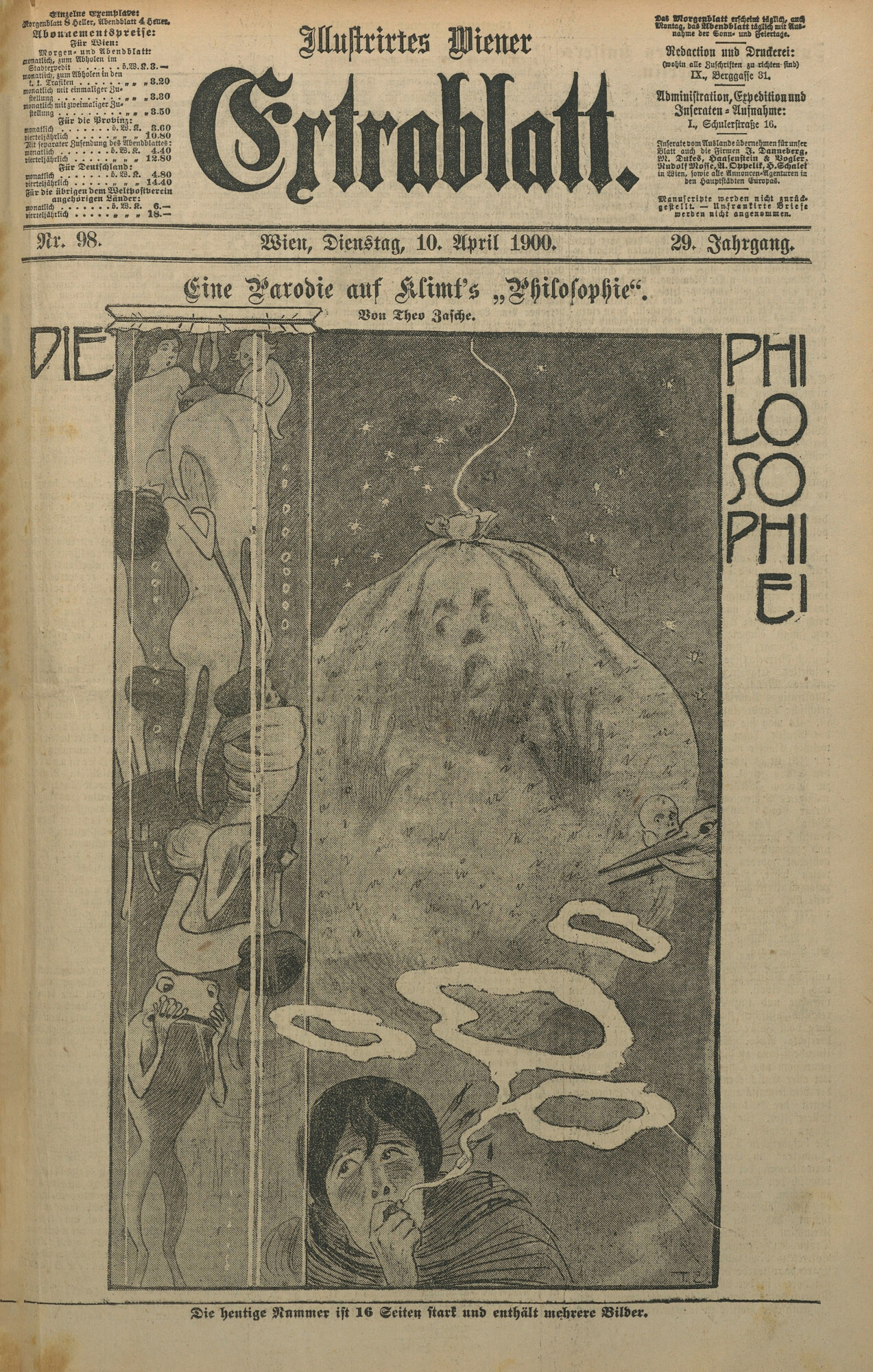

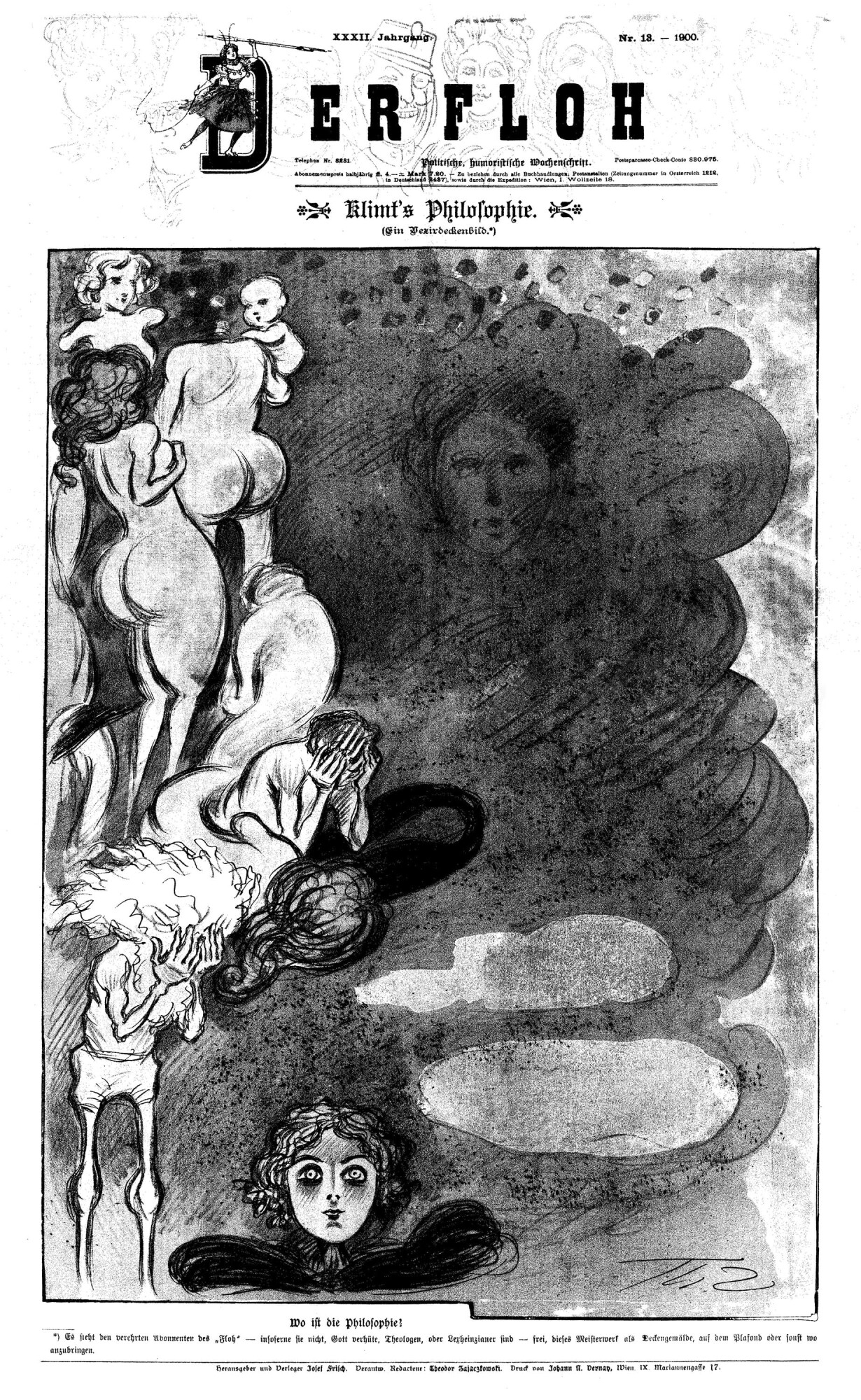

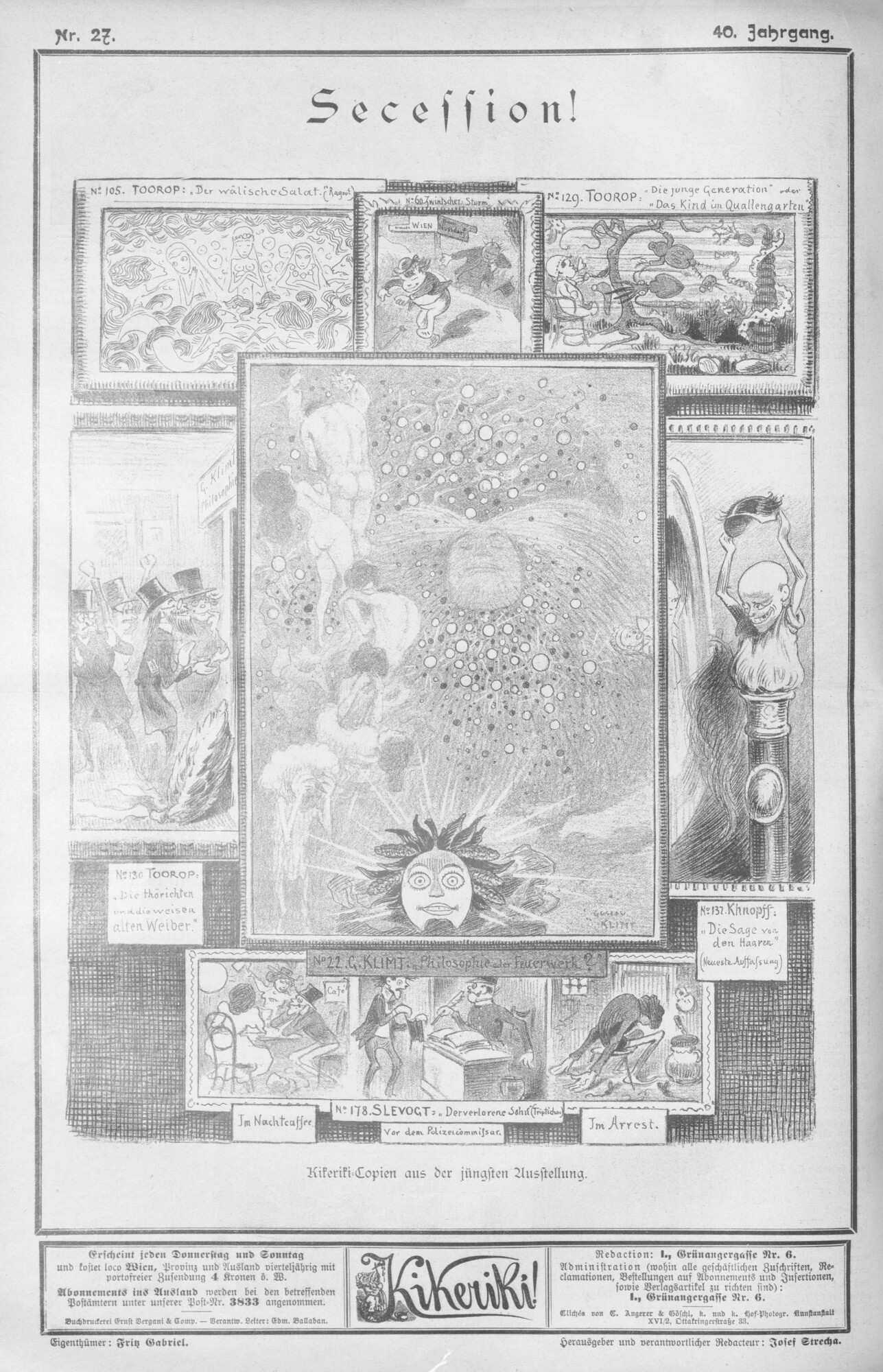

Art Scandal: The “Klimt Affair”

The work Philosophy was first shown at the “VII. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession” which opened on 8 March 1900. The painting was displayed in the main exhibition hall and caused a veritable scandal, which also made international waves. The critics faulted Klimt’s unusual interpretation of the philosophical faculty especially for its lack of a clear pictorial and form language, which they felt made the depiction illegible. Without the explanation in the exhibition catalogue, Klimt’s choice of motif, which deviated from classical iconography, was largely incomprehensible to viewers. Yet, Klimt’s Symbolist pictorial language illustrated his evolution from a Historicist decorative painter to the chief Austrian representative of Modernism. The “Klimt Affair” dominated the newspapers’ arts sections for days in late March 1900, and the work Philosophy was derided in numerous caricatures and satirical articles.

Contemporary Caricatures of the Faculty Painting “Philosophy”

-

Theodor Zasche: Parody of Gustav Klimt's painting "Philosophy", in: Illustrirtes Wiener Extrablatt, 10.04.1900.

Theodor Zasche: Parody of Gustav Klimt's painting "Philosophy", in: Illustrirtes Wiener Extrablatt, 10.04.1900.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Theodor Masche: Klimt's philosophy, in: Der Floh, 01.04.1900.

Theodor Masche: Klimt's philosophy, in: Der Floh, 01.04.1900.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Association! Kikeriki copies from the latest exhibition, in: Kikeriki. Humoristisches Volksblatt, 05.04.1900.

Association! Kikeriki copies from the latest exhibition, in: Kikeriki. Humoristisches Volksblatt, 05.04.1900.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

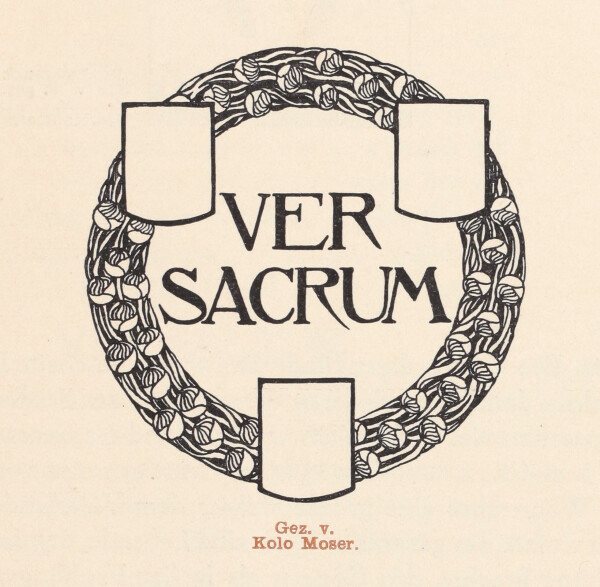

Emil Reisch, Franz Exner, Friedrich Jodl: Circular by Franz Exner, Friedrich Jodl and Emil Reisch, concerning a petition by university professors against the display of the faculty picture "Die Philosophie" (Philosophy), 03/24/1900, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

© Austrian State Archives, Vienna

The scandal culminated in a petition started by a group of university professors, led by Franz Exner, Friedrich Jodl and Emil Reisch, which obtained around 70 signatures within only a few days, and which was inadvertently leaked to the press in a “distorted form.” The professors wanted to prevent the work from being hung in its intended place, arguing:

“We are concerned here only with this one particular painting and with the question of whether or not the artist has fulfilled his commission in a satisfactory manner. We do not intend to voice a general opinion on the art movement, which this painting can be ascribed to, nor do we presume to question Klimt’s oeuvre or artistic personality.”

The main points of criticism were Klimt’s choice to depict philosophy as “the mystery of the world, as coming into being and passing away, and as knowledge,” something which – according to the professors – the artist failed to do in an intelligible manner, as well as the unsuitable and inconsistent composition which did not fit in with the auditorium’s architecture. Karl Kraus also weighed in on the controversy:

“If he were to change the title, his philosophy could still be used elsewhere. It is unsuited to the auditorium’s ceiling, if for no other reason, because Mr. Klimt has failed to align his depiction with Matsch’s design for the central painting.”

The commissioner of the Faculty Paintings, Minister Wilhelm von Hartel, adopted a wait and see approach. The Secessionists defended their founding president by deposing a laurel wreath in front of his controversial work on 27 March 1900. Several university professors – among them Prof. Dr. Wickhoff, Emil Zuckerkandl and Edmund Bernatzik – initiated a counter petition, denying the other professors the authority “[…] to influence the decision in a purely artistic matter […].”

Before the end of the Secession exhibition, the work Philosophy was sent on 2 April 1900 to Paris, where the “World’s Fair” was being held. The Vienna Secession had been tasked with curating a room for the Austrian Pavilion, where the monumental work was presented to the public from 12 May 1900. The exhibition’s jury awarded the painting one of twenty gold medals, the “Grand Prix” in the painting division.

Insight into the Paris World's Fair, May 1900 - November 1900

© Heidelberg University Library

Klimt’s work also received some harsh criticism in the international press. The newspaper Allgemeine Zeitung was surprised by the award and described Philosophy as:

“[…] an entirely incomprehensible Symbolist painting. […] This bundle of naked figures, interspersed with eerily grimacing faces, makes viewers run for the hills.”

In 1900, the weekly magazine Die Wage published interviews with Klimt, Carl Moll and members of the ministry of education’s art council and the philosophical faculty, with Klimt justifying himself and stating:

“The painting must first be seen next to the large central painting and its counterpart, ‘Medicine.’ […] It is not impossible that I might make changes to it once it has returned from Paris. But I will never be forced to do so against my artistic convictions.”

Further contents

-

Klimt's Artworks 1889 – 1894 (Decorator of the Ringstraße)Faculty Paintings. Awarding of the Commission

-

Klimt's Artworks 1895 – 1897 (Symbolism in Klimt’s Oeuvre)Faculty Paintings. First Sketches

-

Klimt's Artworks 1901 – 1903 (The Golden Knight and Femmes Fatales)Faculty Paintings. Medicine and Jurisprudence

-

Klimt's Artworks 1904 – 1906 (The Klimt Affair Surrounding the Faculty Paintings)Faculty Paintings. The Klimt Affair

Literature and sources

- Alice Strobl: Die Fakultätsbilder »Medizin« und »Philosophie«, in: Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007, S. 41-53.

- F. V.: Paris, in: Allgemeine Zeitung (München), 11.06.1900, S. 2.

- Karl von Vicenti: Wiener Frühjahr-Ausstellungen. Secession, in: Die Kunst für Alle. Malerei, Plastik, Graphik, Architektur, 15. Jg. (1899/1900), S. 368-372, S. 396.

- Alfred Deutsch-German: Im Atelier Gustav Klimmt's, in: Neues Wiener Journal, 01.10.1899, S. 4.

- Markus Fellinger, Michaela Seiser, Alfred Weidinger, Eva Winkler: Gustav Klimt im Belvedere. Vergangenheit und Gegenwart, in: Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt 150 Jahre, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 13.07.2012–27.01.2013, Vienna 2012, S. 31-281.

- N. N.: Der Kampf um die "Philosophie". Interviews, in: Die Wage. Wiener Wochenschrift, 3. Jg., Heft 14 (1900), S. 224-225.

- Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 3 (1898), S. 3.

- Vereinigung bildender KünstlerInnen Wiener Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Mitteilungen der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 3. Jg., Heft 10 (1900), S. 150.

- Abschrift eines Briefes vom k. k. Ministerium für Cultus und Unterricht an Franz Matsch und Gustav Klimt (07/07/1898). S102.3616.3, .

- Abschrift des Akademischen Senats der k. k. Universität Wien von einem Brief des k. k. Ministerium für Cultus und Unterricht an das Rektorat der k. k. Universität Wien mit einer Notiz für die Artistische Comission (05/21/1898). S102.3222.3, .

- Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Katalog der VII. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession, Ausst.-Kat., Secession (Vienna), 09.03.1900–06.06.1900, 1. Auflage, Vienna 1900.

- Rundschreiben von Franz Exner, Friedrich Jodl und Emil Reisch, betreffend eine Petition der Universitätsprofessoren gegen die Anbringung des Fakultätsbildes „Die Philosophie“ (03/24/1900). AT-OeStA/AVA Unterricht Präsidium Akten 266, Zl. 1.126/1900 fol. 3-6, .

- Karl Kraus: Klimt, in: Die Fackel, 1. Jg., Heft 36 (1900), S. 16-20.

- Gegenpetition der Professoren der k. k. Universität Wien an das k. k. Ministerium für Cultus und Unterricht in Wien (presumably late March 1900). AT-OeStA/AVA Unterricht Präsidium Akten 266, Zl. 1.126/1900 fol. 15, .

- Petition der Professoren der k. k. Universität Wien an das k. k. Ministerium für Cultus und Unterricht in Wien (05/05/1900). AT-OeStA/AVA Unterricht Präsidium Akten 266, Zl. 1.126/1900 fol. 7-14, .

- N. N.: Der Protest gegen Klimt's "Philosophie", in: Neue Freie Presse (Abendausgabe), 27.03.1900, S. 1.

- Die Wage. Wiener Wochenschrift, 3. Jg., Heft 14 (1900).

Ver Sacrum and Scandalous Poster

Logo of the Association of Austrian Visual Artists - Ver Sacrum, 1897

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Kolo Moser: Vignette from the first Ver Sacrum booklet, 1898

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

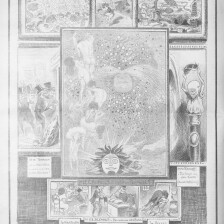

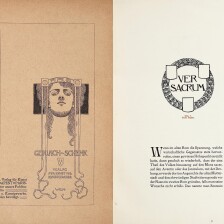

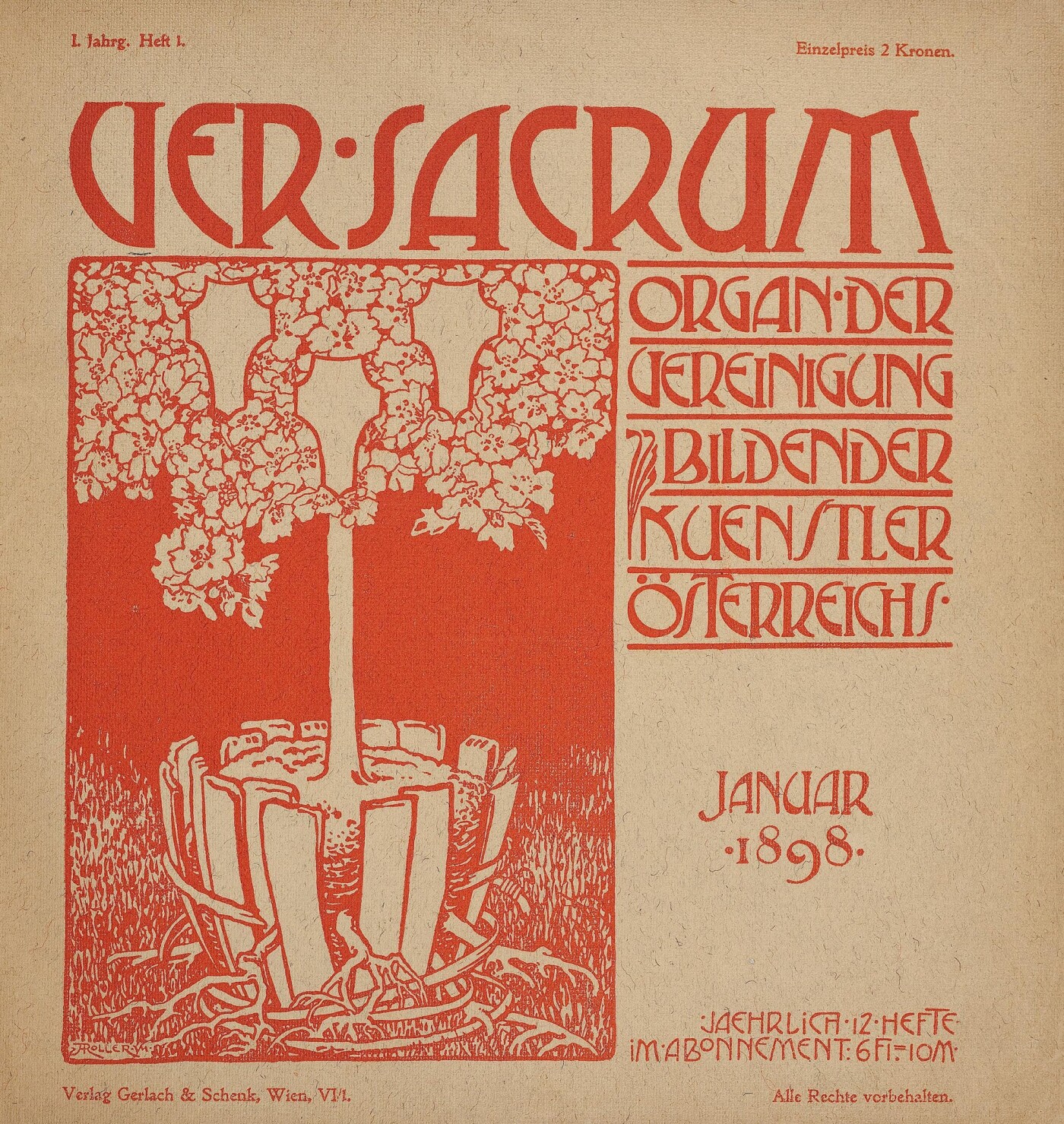

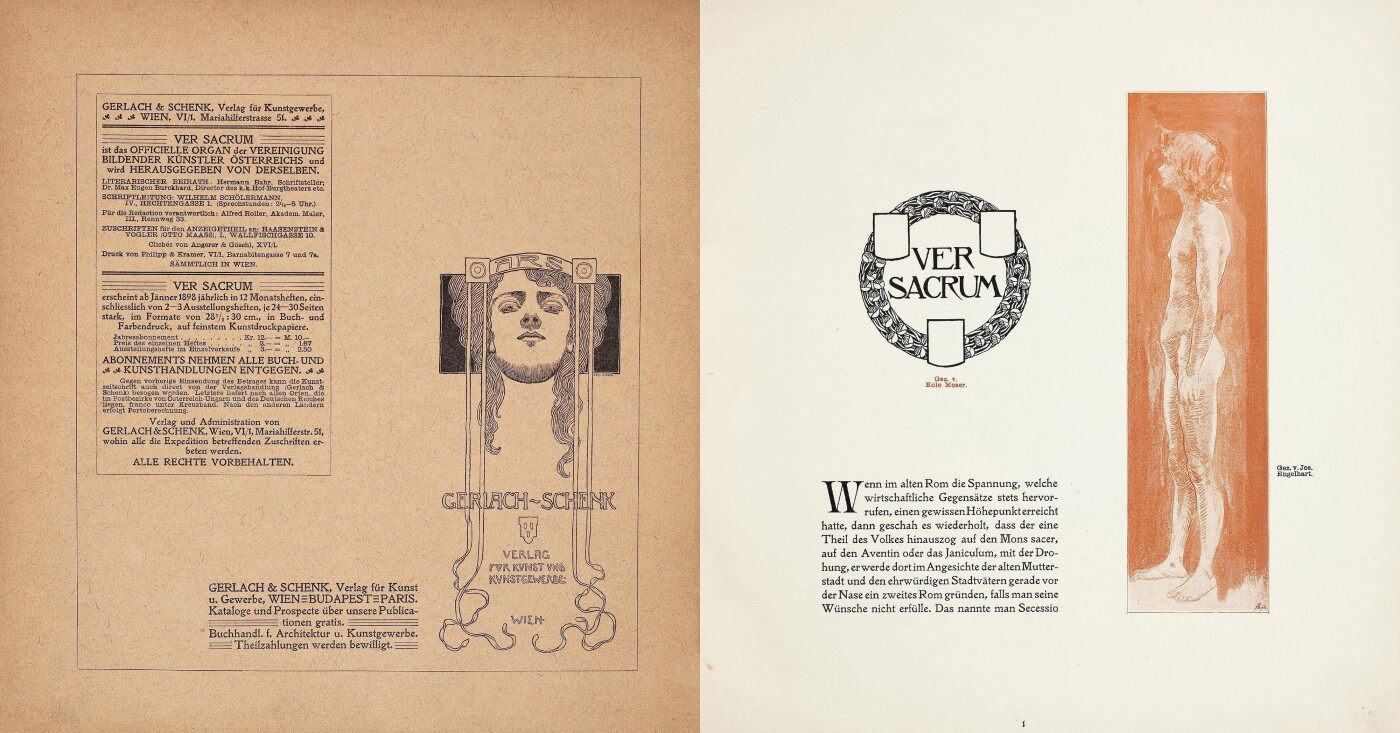

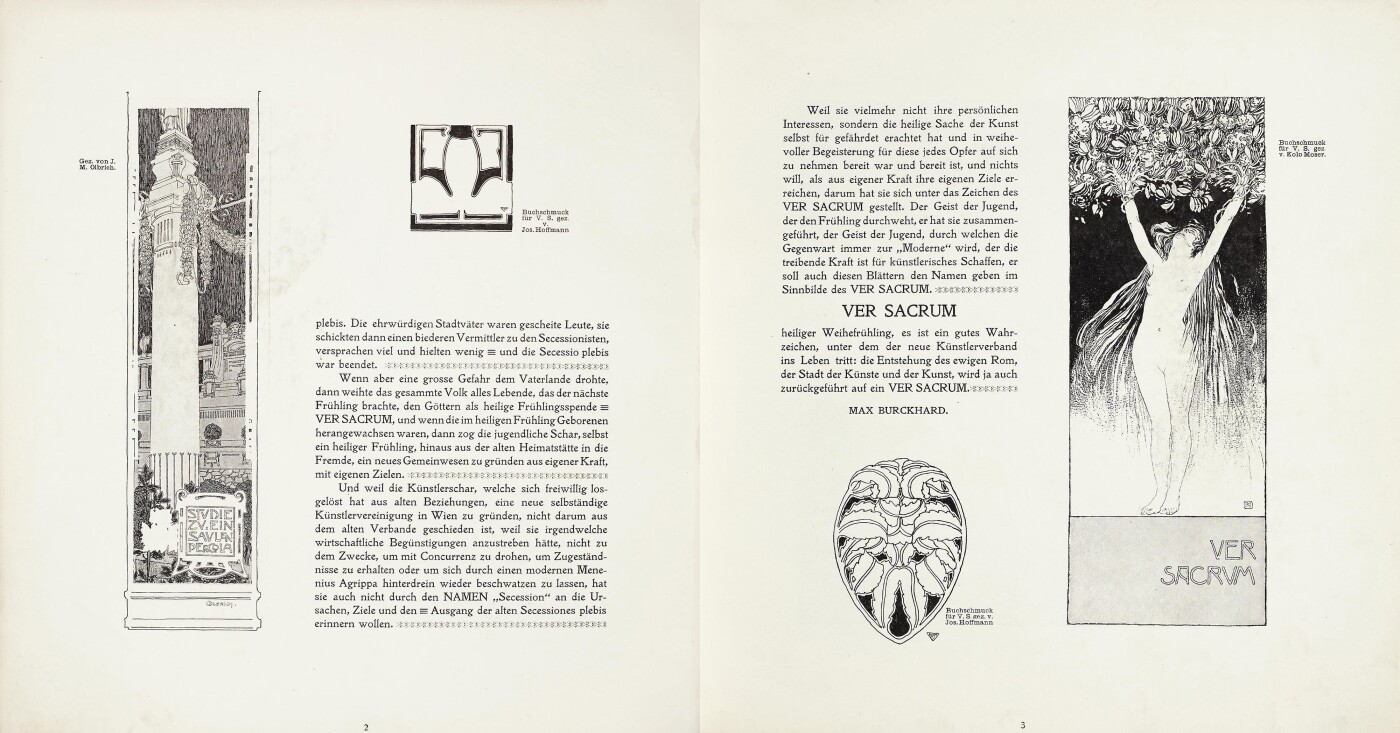

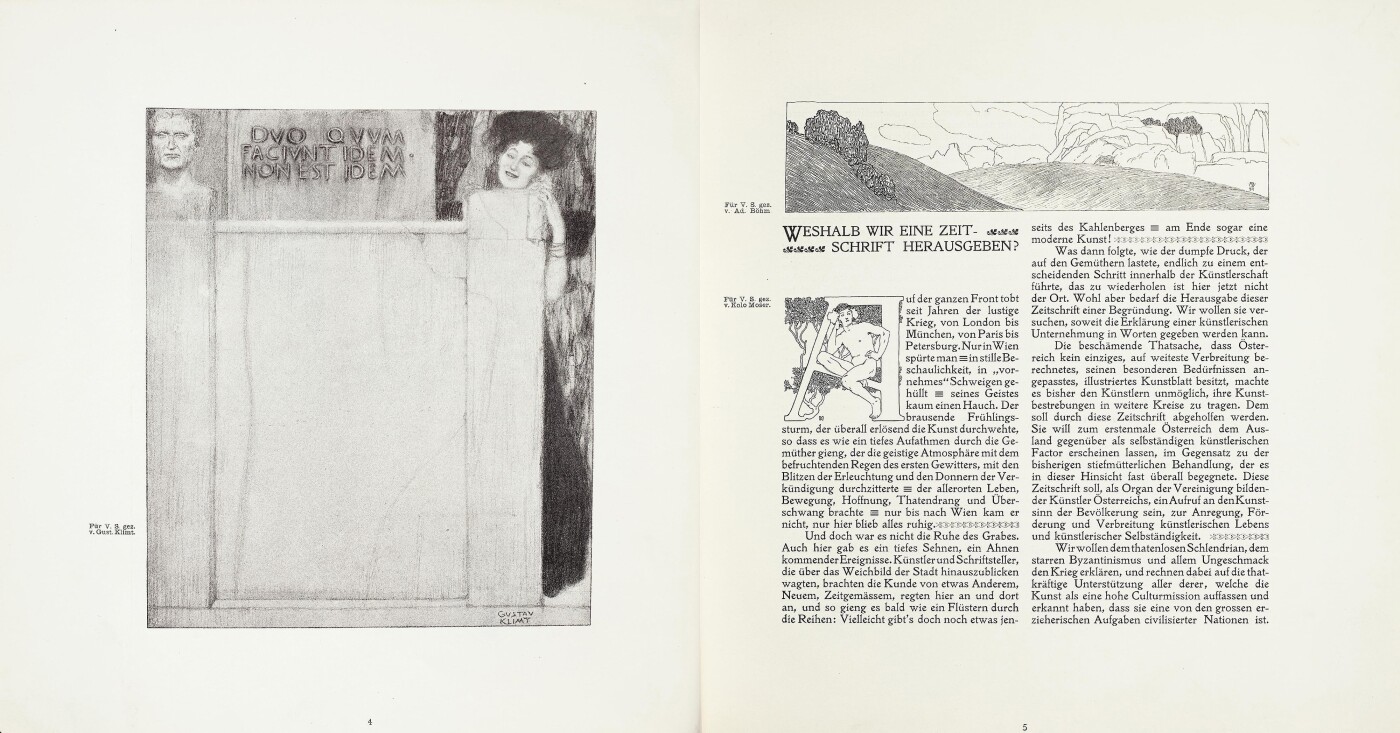

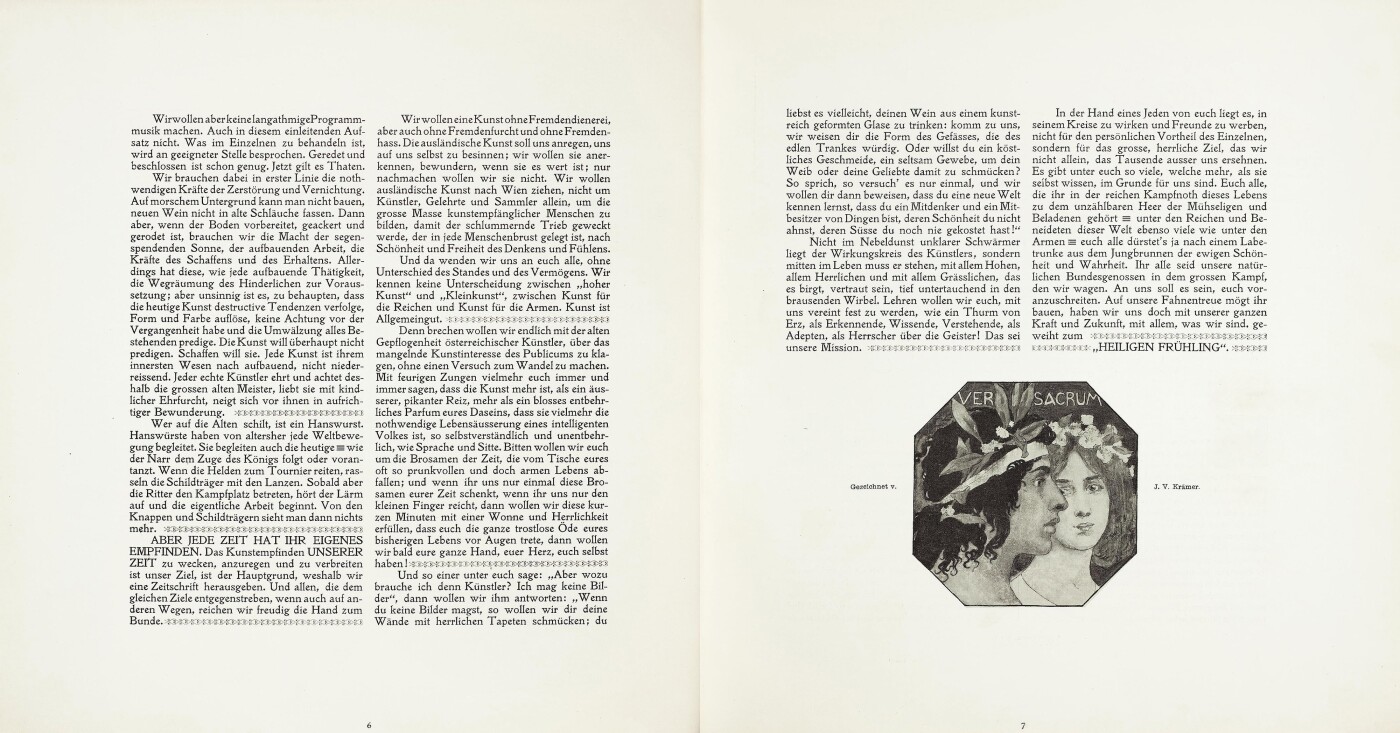

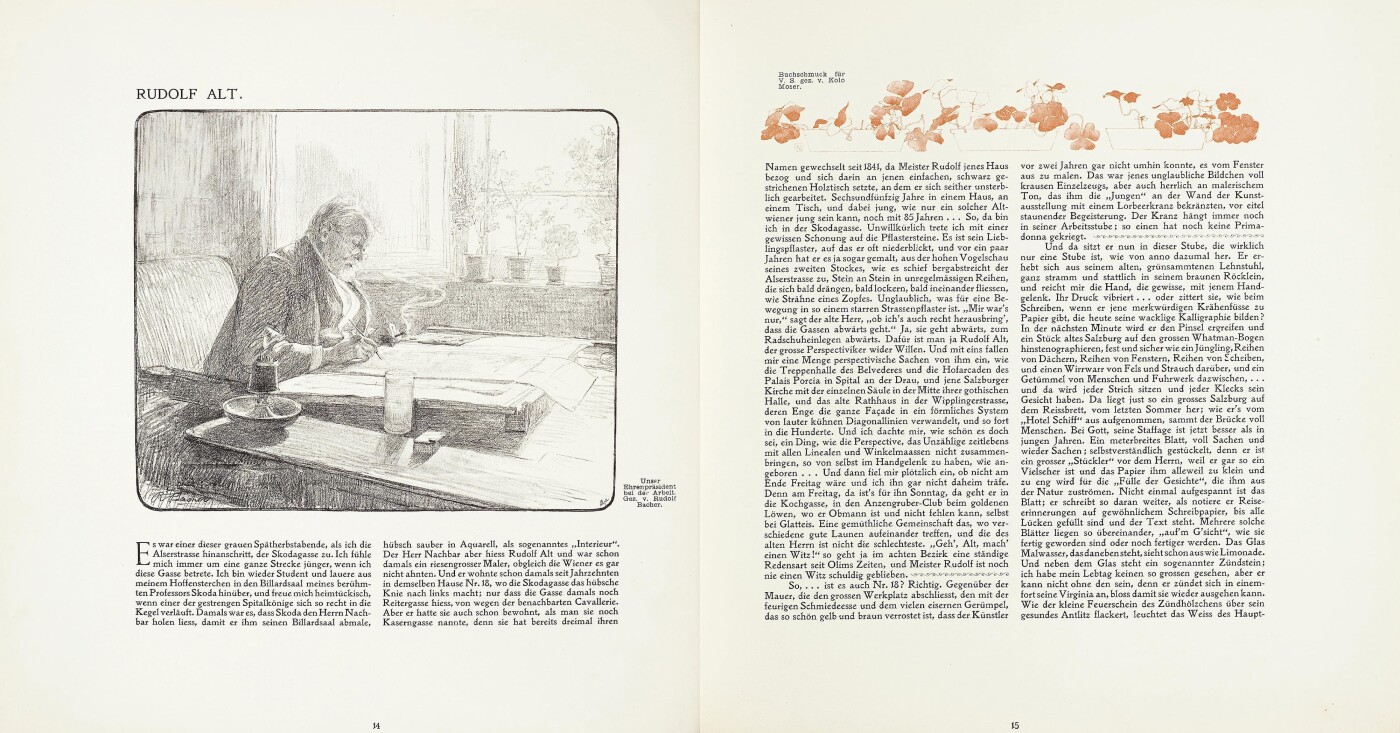

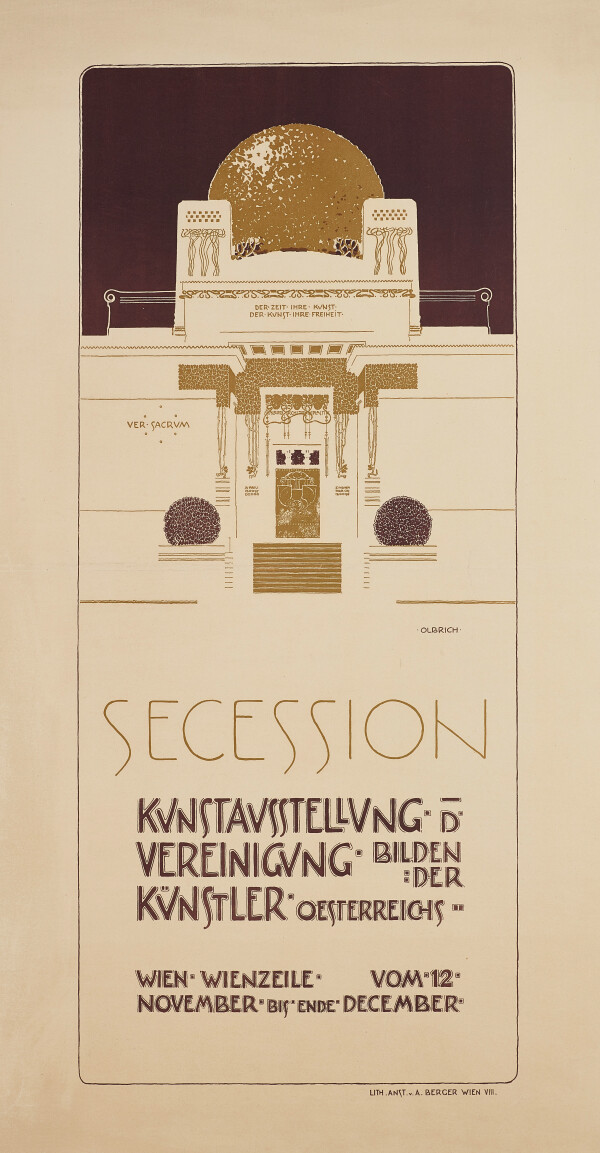

In his capacity as first president of the Vienna Secession, Gustav Klimt exerted a decisive influence on the direction of the new association. He designed the poster for the "I. Kunst-Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs" ["1st Exhibition of the Vienna Secession"], exhibited his own works alongside international avant-garde artists in this presentation, and furnished contributions for the association’s ground-breaking magazine Ver Sacrum.

In the 1890s, the desire for artistic renewal led to the foundation of avant-garde artists’ association all across Europe. The bourgeoning ideas of Modernism were disseminated both through the international exhibitions held by the various “Secessions,” and via art periodicals. In Vienna, the most famous founding members of the Association of Austrian Artists Secession included Gustav Klimt, as well as Kolo Moser, Carl Moll and Joseph Maria Olbrich. In 1897, Klimt was elected the association’s first president, with Moll acting as vice president and Rudolf von Alt, who was already 85 years old at the time, as honorary president. The Secession wanted to represent the interests of modern artists, sought to expedite the “revitalization of the Viennese art scene,” to convey international art and to champion the freedom of artistic work. They focused on the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk, in which artisan craftwork was to be treated on a par with painting, sculpture and architecture.

The Objectives of the Association’s Medium Ver Sacrum

Already during the Secession’s first general assembly on 21 July 1897, it was settled that the association should publish a medium with the title Ver Sacrum. The art periodical was first issued in January 1898 with Gerlach & Schenk publishers. In its first number, the following reasons were given for the magazine’s publication:

“The disgraceful fact that Austria does not have a single illustrated art journal, catering for the country’s particular needs and intended for wide circulation, has made it impossible for artists to promulgate their artistic endeavors. […] As a medium of the Association of Austrian Artists, this magazine is meant to appeal to the population’s appreciation of art, to stimulate, promote and disseminate artistic life and autonomy.”

Alfred Roller acted as the magazine’s editor, while the literary council included Hermann Bahr and Max Burckhard. The latter wrote an opening essay in the first issue, in which he elucidated that the choice of name for the association went back to the Roman tradition of “secessio plebis” – the custom of common people walking out in a demonstration of power to assert their political claims against the patricians. He further explained the journal’s title Ver Sacrum: The “Sacred Spring” also referred to a Roman tradition, which dictated that those who were born in the spring were destined in their adulthood to “leave home to found a new community from their own strength and with their own goals.”

Ver Sacrum, Year 1, Number 1 (1898)

-

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

The magazine became one of the most eminent art periodicals of the time, not just on account of its programmatic content but also due to its innovative graphic design, which reflected the form language of Jugendstil and budding Viennese planar art. From the first year of publication, Gustav Klimt created several illustrations, vignettes and initials for Ver Sacrum, which are testament to his artistic re-orientation and the influence of Symbolism on his work. Along with Klimt’s contribution to book ornamentation, the magazine also reproduced numerous paintings, drawings and works on paper which document his works created at that time.

Poster design, in: Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 3 (1898).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Poster design for the I Secession Exhibition, uncensored version, 1898, Klimt Foundation, Vienna

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Poster design for the I Secession Exhibition, censored version, 1898, Klimt Foundation, Vienna

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Poster for the First Exhibition

Since the Secession initially did not have its own exhibition venue, the “I. Kunst-Ausstellung” was held at the flower halls of the Imperial-Royal Horticultural Society on Parkring. The exhibition design was carried out by Hoffmann and Olbrich, with assistance from the “decoration committee” which embarked on the adaptation of the premises on 1 March 1898. The show was advertised through an advance notice, as the poster drawn by Klimt was “not to be posted until just before the exhibition opening.” On 25 March, Franz Xaver von Gayrsperg described the advance notice posters, which have not survived, as “three green signs meant to symbolize the green art of ‘youth’ or the green color of hope in the three fine arts.”

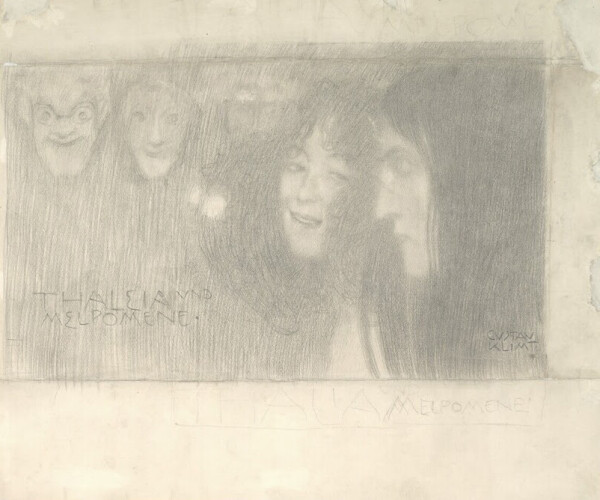

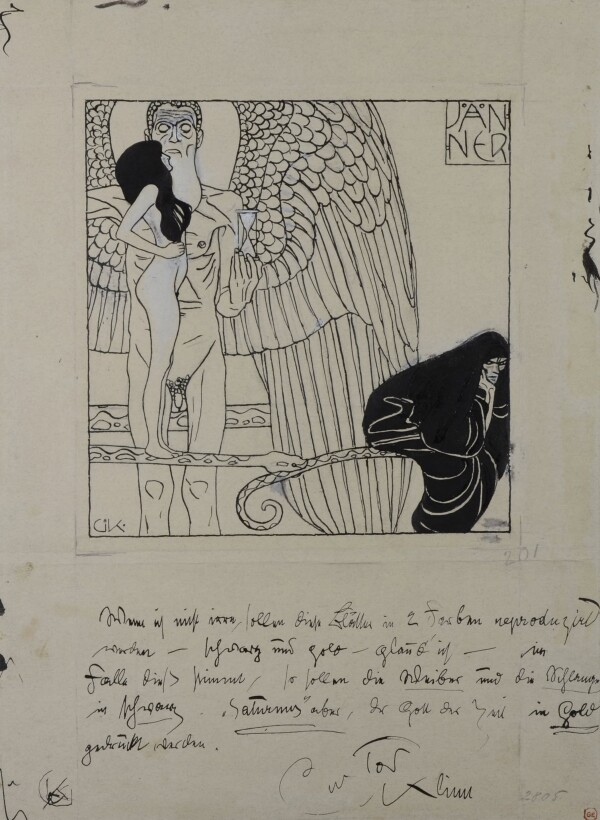

Klimt prepared two different drafts for the first exhibition poster – both with a lot of blank space – which were published in the March issue of Ver Sacrum. For the abandoned poster sketch, Klimt drew a laurel-crowned winged figure, shown from the front, in the upper part which was connected with the written text at the bottom via a snake coiling along the blank area.

For a further poster draft, Klimt also chose a radical composition whose architectural structuring into separate areas dedicated to image and text emphasized the blank space. Along with antique-like typography, he also made recourse to mythological creatures. In the picture frieze above the cornice, Klimt depicted the battle of the naked hero Theseus with Minotaur. On the right edge of the depiction, we discern Pallas Athene who, as goddess of wisdom, strategy, battle, the arts and craftsmanship, and equipped with a spear, a helmet and an apotropaic Gorgoneion shield, watches over the symbolic fight of the Secession against the Künstlerhaus. Thus, the Secessionists’ polemic rhetoric was not only palpable in the articles for Ver Sacrum but continued in the posters. As Theseus rescued the victims from Minotaur, the Secession liberated itself from the constraints of the Künstlerhaus to depart into the “Sacred Spring” and demonstrate its artistic superiority.

“A Cheery Little Piece for Censorship” and “Political Botany”

In the fine drawing (1898, Wien Museum, S 1980: 327) for the poster, Klimt added the exhibition notice, placed the inscription VER SACRUM THESEUS AND MINOTAUR directly next to the battle scene, and covered Theseus’ exposed genitals with a leaf. This version of the poster has survived as a three-colored lithograph in black, red and gold, and as the title page of the May to June 1898 issue of Ver Sacrum.

According to press law, posters – as opposed to printed publications – were subject to pre-censorship. The censors raised objections to the posters – likely already printed at the lithographic printing office of Albert Berger – before the opening of the exhibition. While the records documenting the censorship case have yet to be discovered, it is illustrated by ironic commentaries in the press. Ludwig Hevesi wrote on 25 March in the newspaper Pester Lloyd:

“This Theseus, then, was too naked for the censors! Though concealed by the obligatory fig leaf, even this was considered indecent by the virtuous censors who proscribed the poster. […] Klimt was forced to paint a couple of thick trees to hide Theseus.”

The Ostdeutsche Rundschau described Klimt having to “quickly grow a couple of trees over the already printed battle scene” as a kind of “political botany,” while the paper Das Vaterland called the censorship a “little mishap.” The social democratic Arbeiter-Zeitung attributed the “confiscation” to press prosecutor Dr. Bobies, noting:

“The Secessionists, too, are the kind of filthy pigs who offend common decency by painting a horse without trousers. […] Perhaps Dr. Bobies should go to the trouble of revising the catalogue of the Kunsthistorisches Museum. He will discover dreadful things there, much worse than the Secessionists’ poster.”

Eventually, the exhibition could be advertised with the censored poster, in which trees covered the nakedness – or rather the fig leaf – of Theseus. These tree trunks were probably printed over the already printed lithographs. It is likely that the scandal, handed down through reference works, caused more amusement than outrage among contemporaries.

Franz Holluber: Billboard on Karlsplatz with the 1st Secession poster, 1898, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

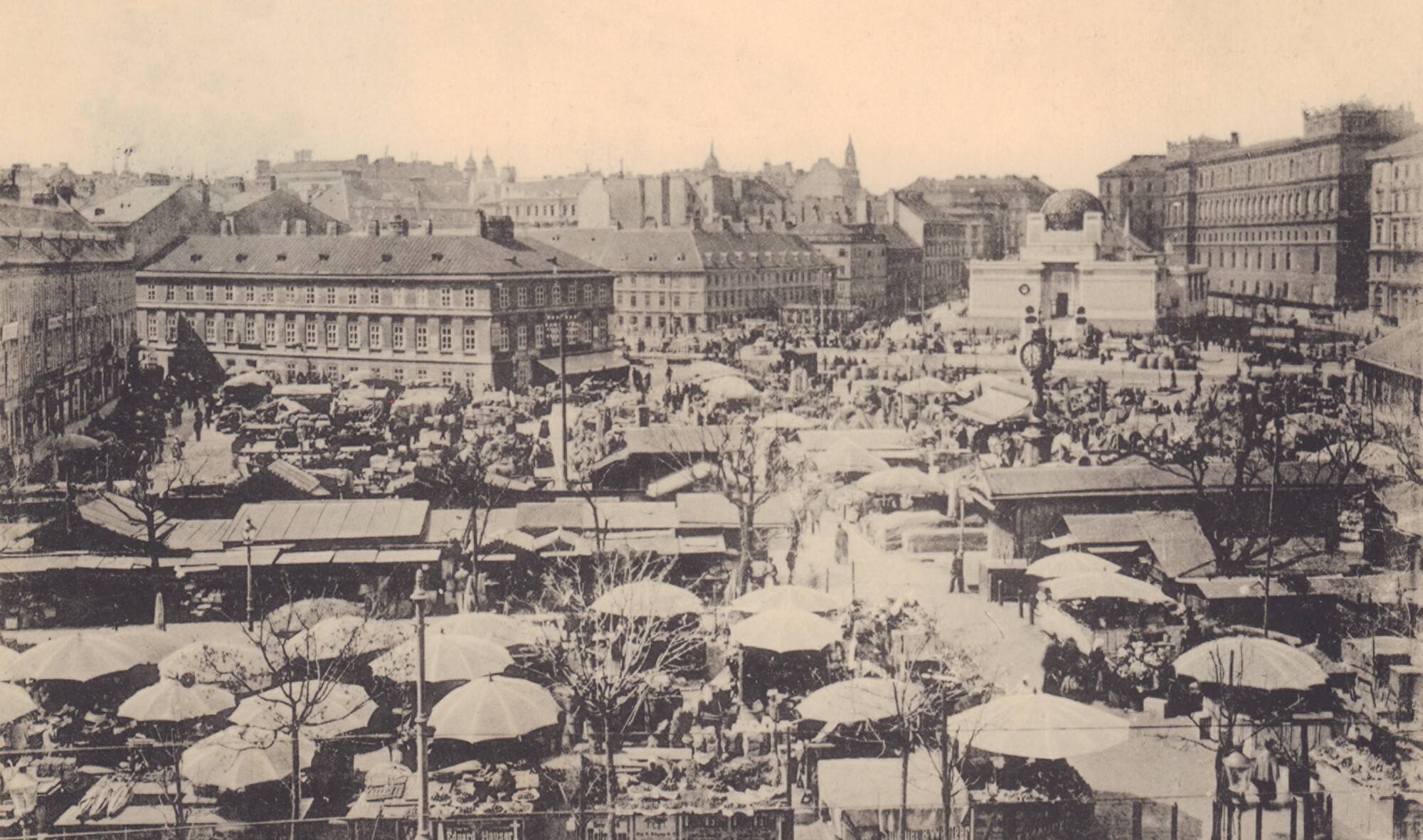

Flower rooms of the k. k. Gartenbaugesellschaft at Parkring 12, 1904

© Wien Museum

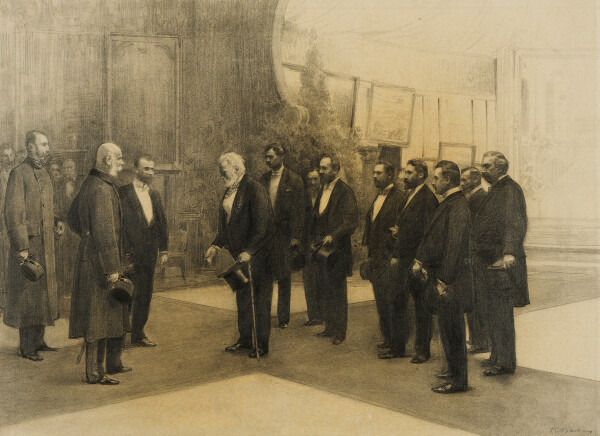

Rudolf Bacher: Emperor Franz Joseph visits the first exhibition of the Vienna Association at the Gartenbaugesellschaft, 1898, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

The Emperor’s Visit