Klimt's work focuses on all aspects of the Art Nouveau master's oeuvre. Visualized through a timeline, Klimt's creative periods are rolled up here, starting with his training, his collaboration with Franz Matsch and his brother Ernst in the "Künstler-Compagnie", the affair surrounding the faculty paintings and his post-fame and the myth that still surrounds this exceptional artist today.

Posthumous Fame and Legend

→

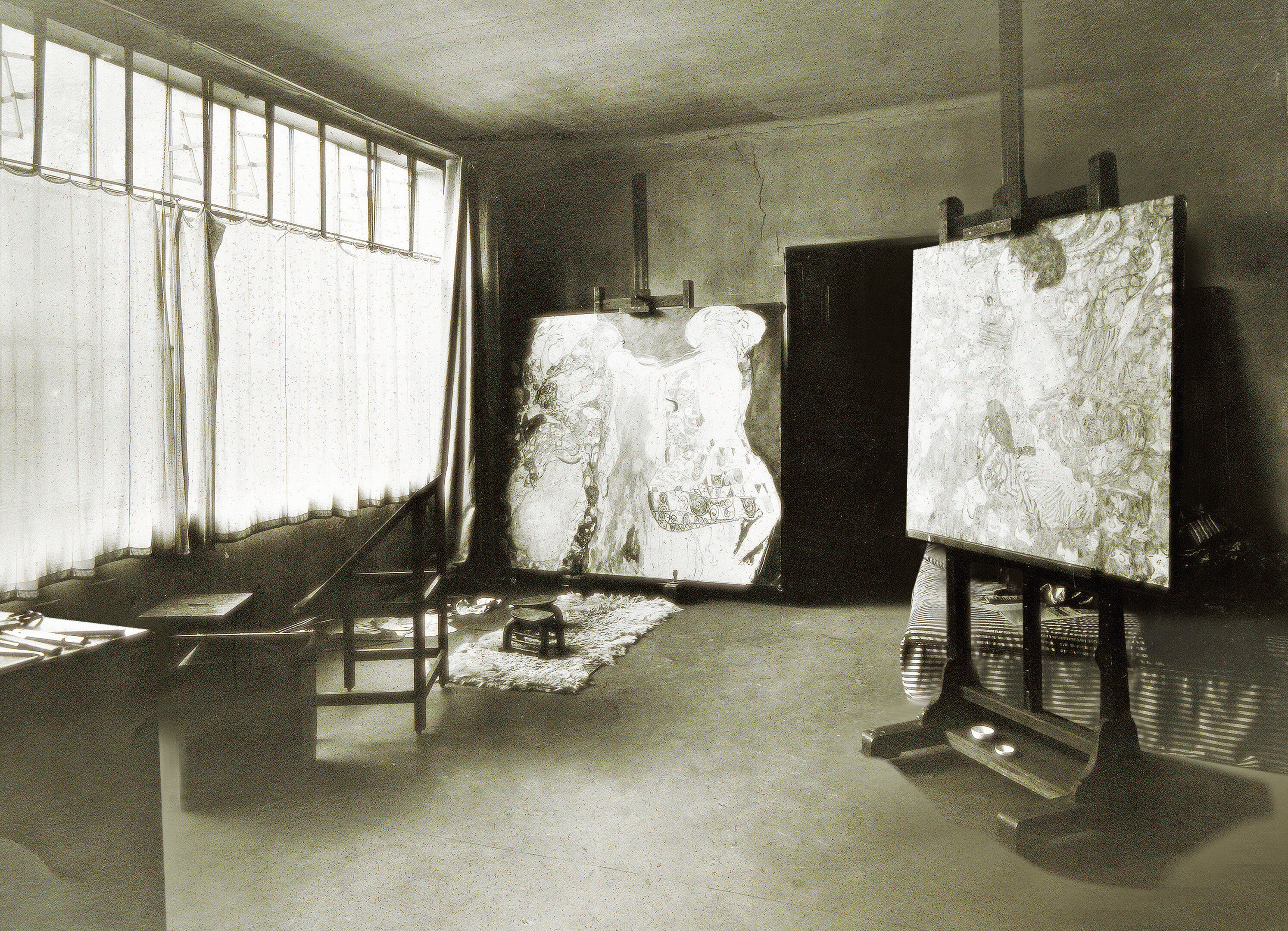

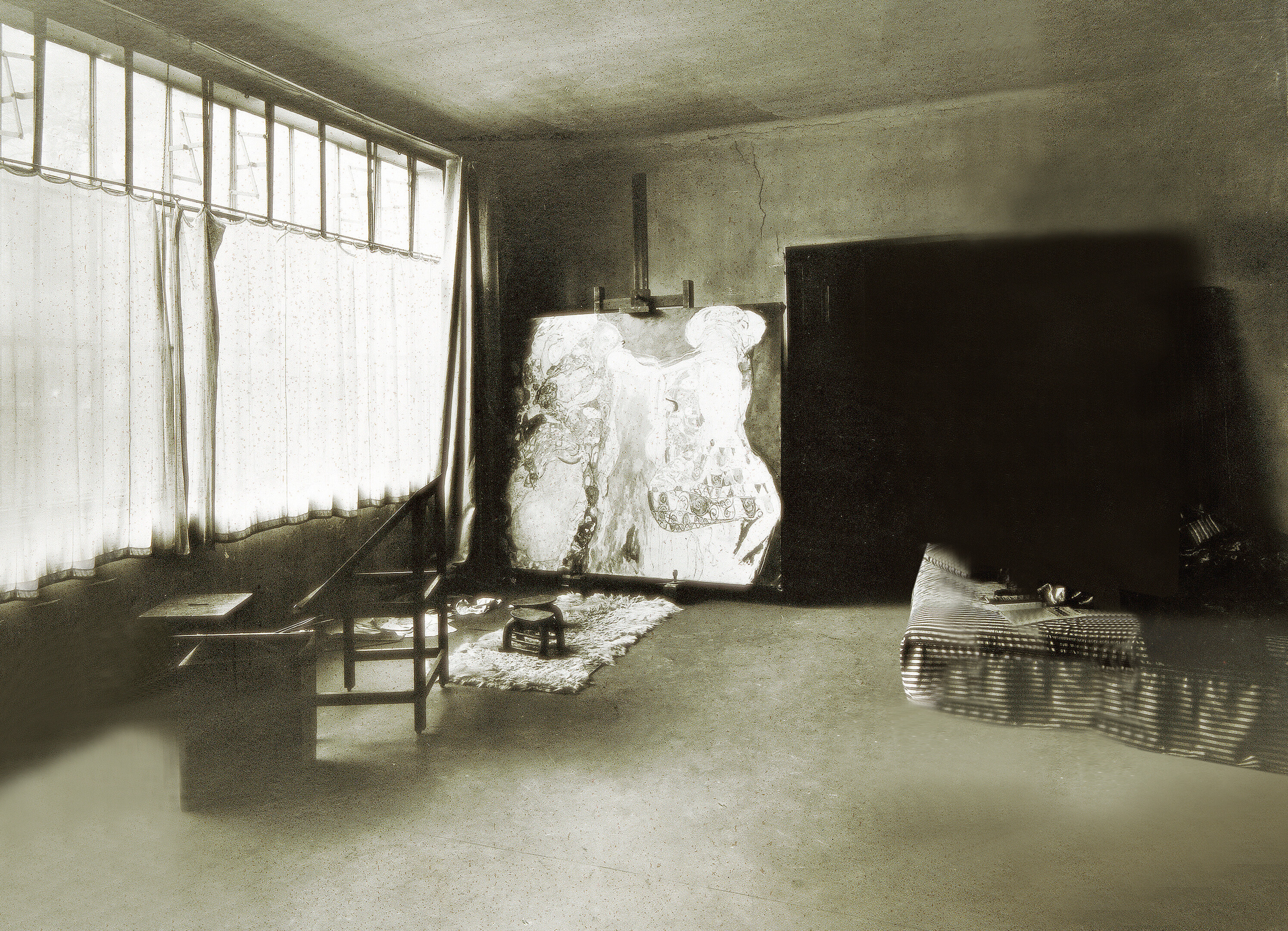

Moriz Nähr: Gustav Klimt's workshop in Feldmühlgasse, presumably 1917, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Estate

Gustav Klimt’s estate comprised modest savings, numerous unfinished and unsold paintings, as well as countless drawings. It was divided amongst his four siblings, his niece Helene Donner, her aunt Emilie Flöge, and his illegitimate children.

To the chapter

→

Obituary of Gustav Klimt, 02/12/1918, Wiener Stadt- und Landesarchiv

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna

Commemorating Gustav Klimt

After Klimt’s death, a number of renowned contemporaries made it their task to put the artist of the century’s life and work down in writing. In addition to monographs and publications by Max Eisler, Emil Pirchan, and Arthur Roessler, it was above all the so-called “Klimt Chronicle” by Georg Klimt that gained special importance.

To the chapter

→

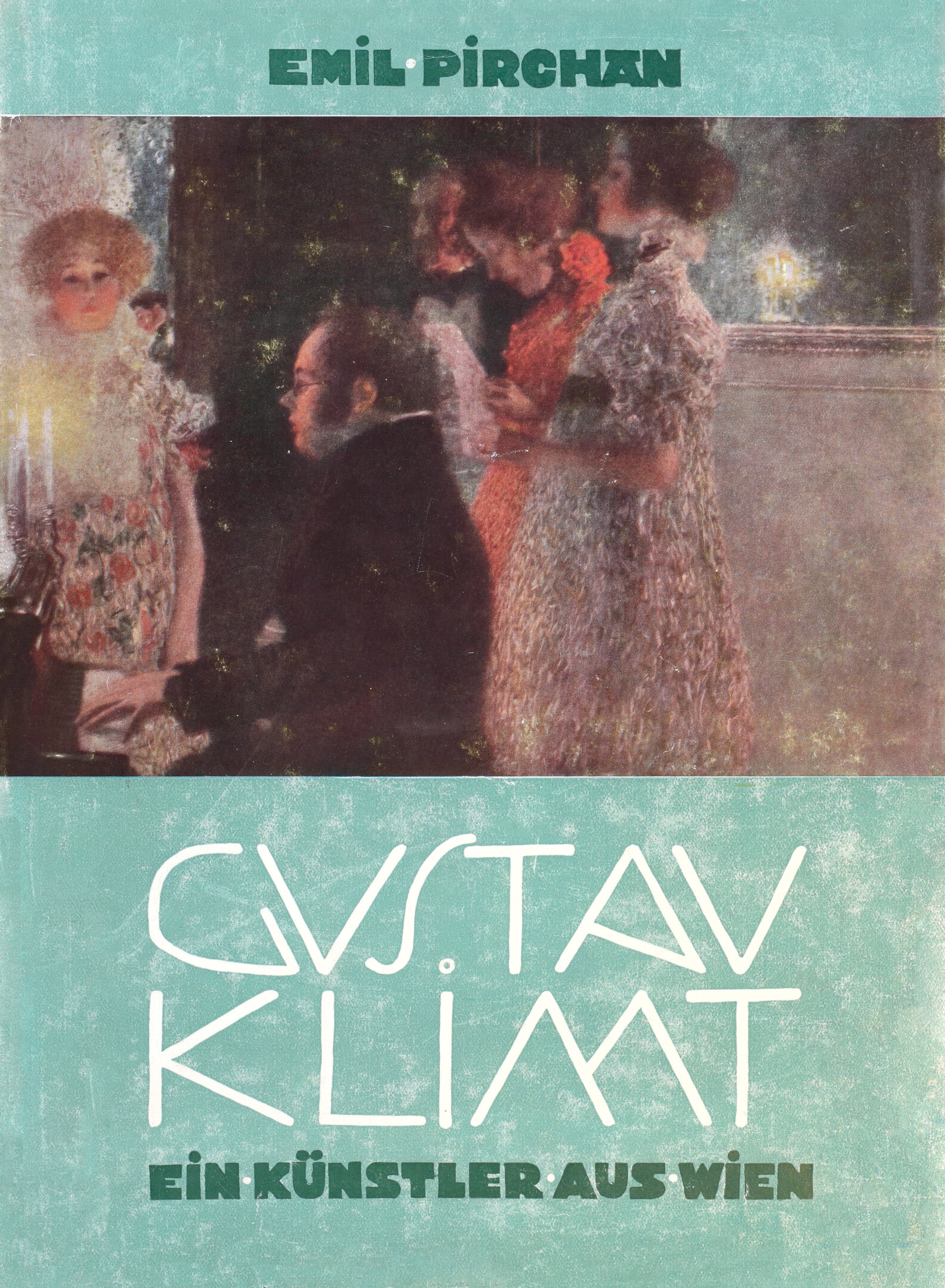

Emil Pirchan: Gustav Klimt. Ein Künstler aus Wien, Vienna - Leipzig 1942.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Exhibition in Commemoration of Klimt

In the summer of 1928, an exhibition was held at the Vienna Secession on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of Gustav Klimt’s death. It was initiated and compiled by some of his closest artist-companions, headed by Carl Moll.

To the chapter

→

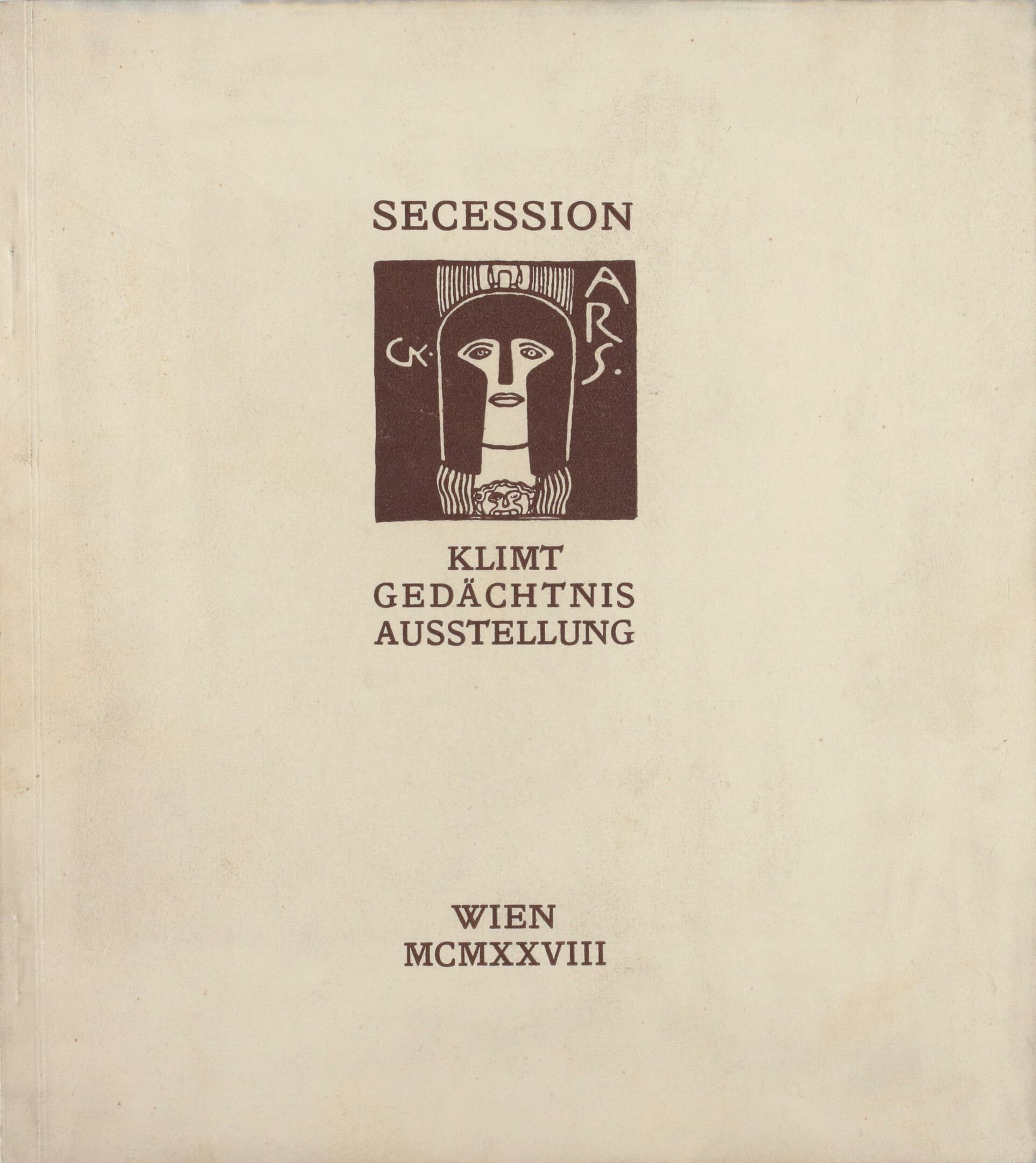

Vereinigung bildender KünstlerInnen Wiener Secession (Hg.): XCIX. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Wiener Secession. Klimt-Gedächtnis-Ausstellung, Ausst.-Kat., Secession (Vienna), 27.06.1928–05.08.1928, Vienna 1928.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Show at Ausstellungshaus Friedrichstraße

In the spring of 1943, with World War II still in full swing, a big Klimt retrospective exhibition was held at Ausstellungshaus Friedrichstraße, the former Secession building. The show, which had been organized with some delay to mark the artist’s 80th birthday, took place under the auspices of Vienna’s Reichsstatthalter Baldur von Schirach.

To the chapter

→

Poster of the Gustav Klimt memorial exhibition, 1943, private collection

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Klimt Collectors – Persecuted by the National Socialists

It is not least due to restitution procedures that those art collectors persecuted by the National Socialists are much more distinctly perceived by the public today than other collectors. However, it is true that among Klimt’s clientele were indeed many collectors of Jewish origin.

To the chapter

→

Martin Gerlach: Insight into the apartment of Serena and August Lederer, 1920s - 1930s, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Immendorf Castle

In May 1945, Austria suffered one of the most serious losses in cultural assets. In the wake of World War II, at least ten paintings and two compositional designs by Gustav Klimt were destroyed by fire, including such masterpieces as the three Faculty Paintings. In addition, further art objects fell victim to the flames.

To the chapter

→

Immendorf Castle

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Posthumous Fame and Legend

→

Moriz Nähr: Gustav Klimt's workshop in Feldmühlgasse, presumably 1917, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Estate

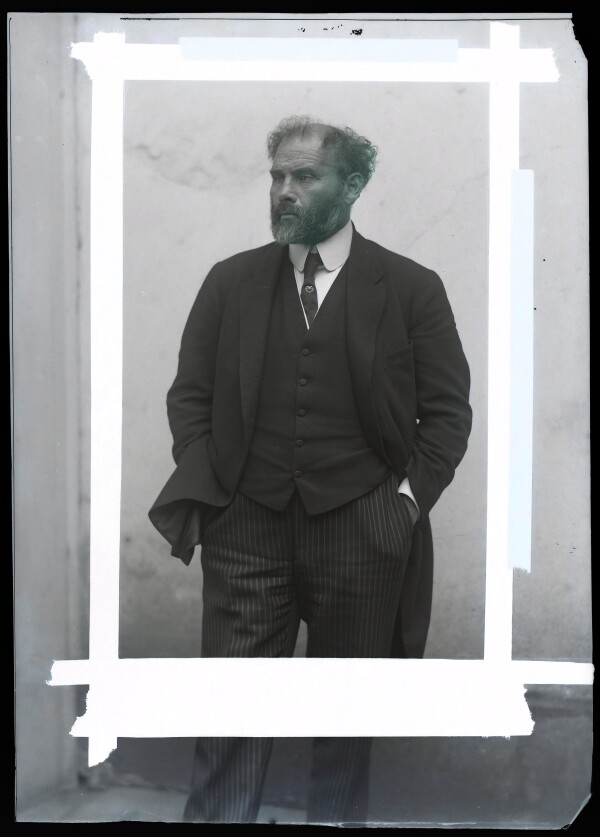

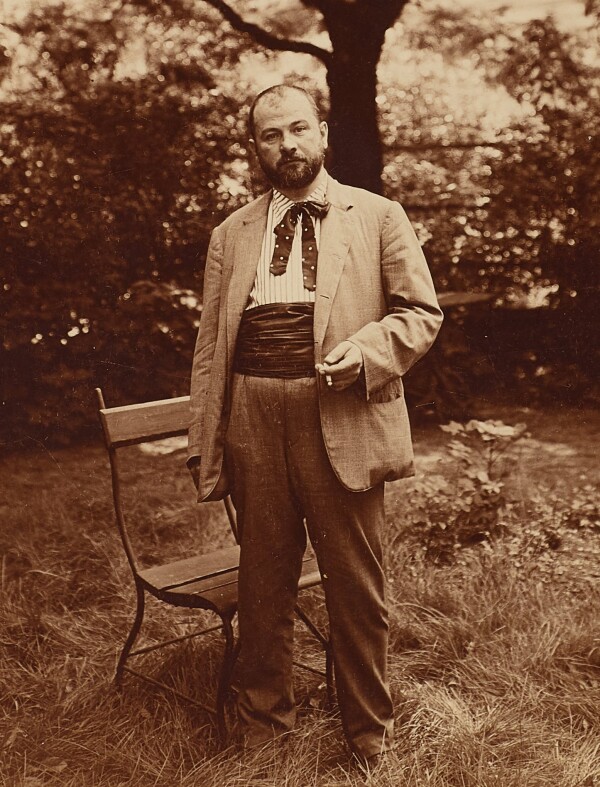

Moriz Nähr: Gustav Klimt in front of his studio in Feldmühlgasse, May 1917, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Gustav Klimt’s estate comprised modest savings, numerous unfinished and unsold paintings, as well as countless drawings. It was divided amongst his four siblings, his niece Helene Donner, her aunt Emilie Flöge, and his illegitimate children.

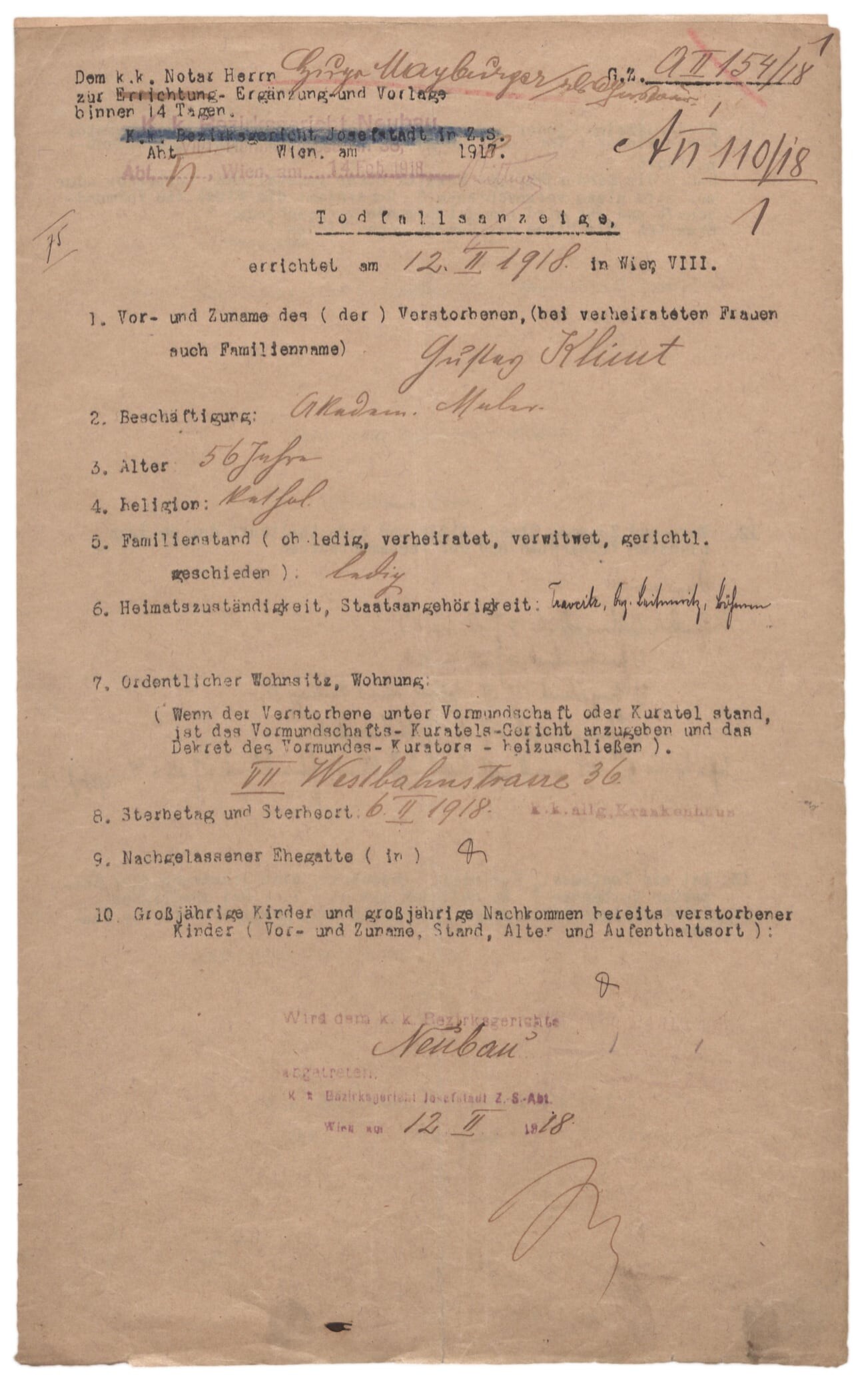

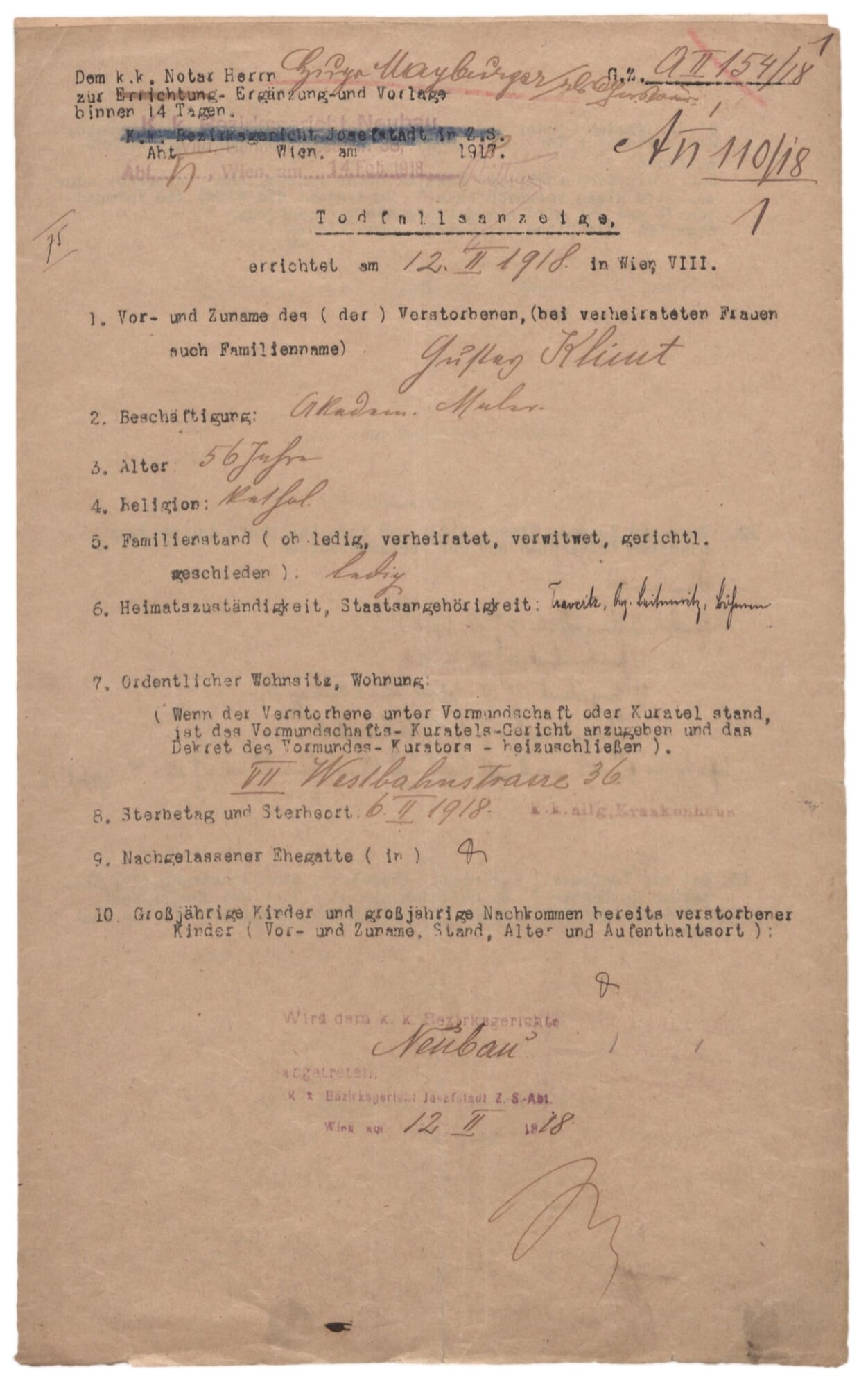

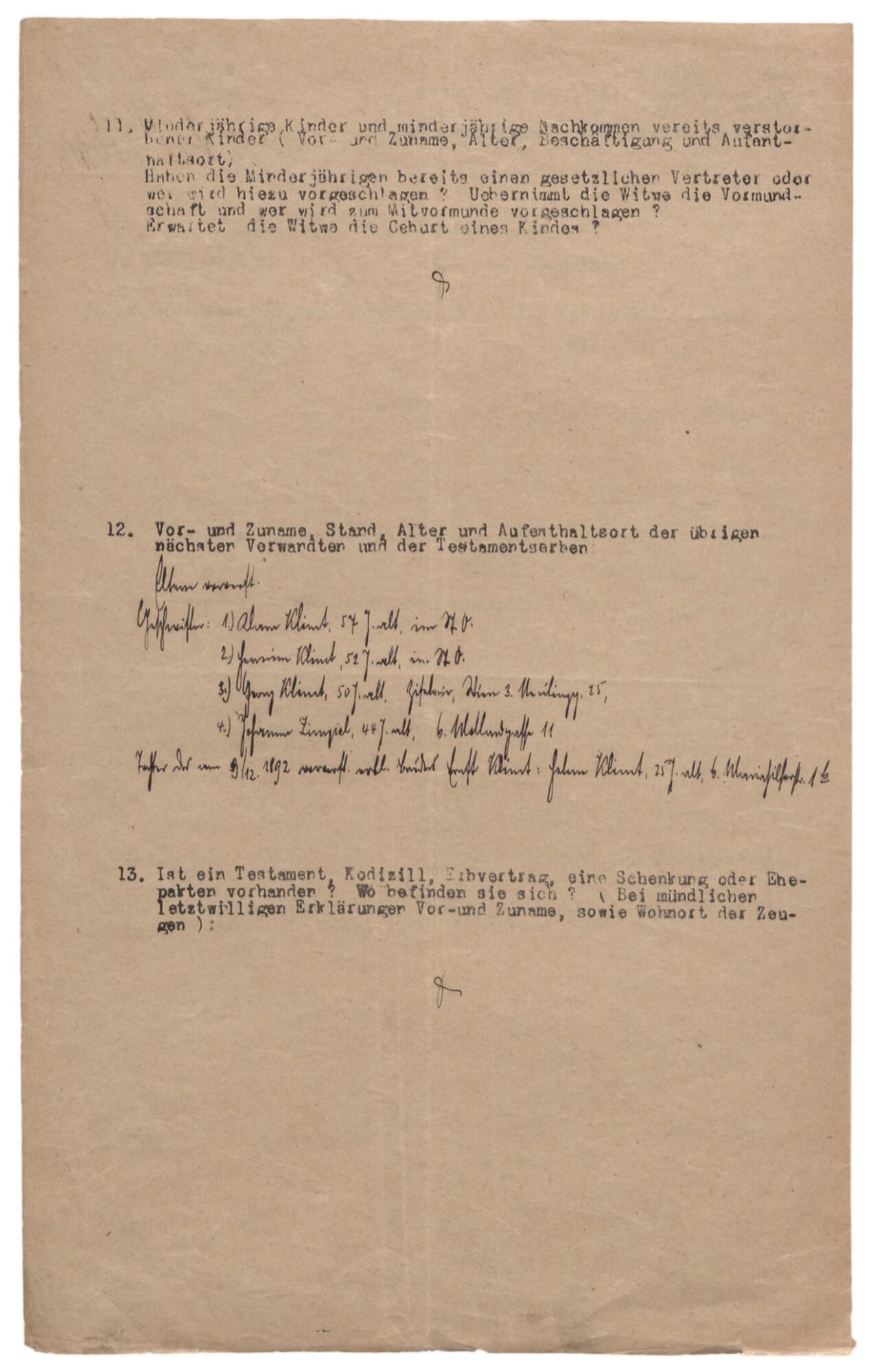

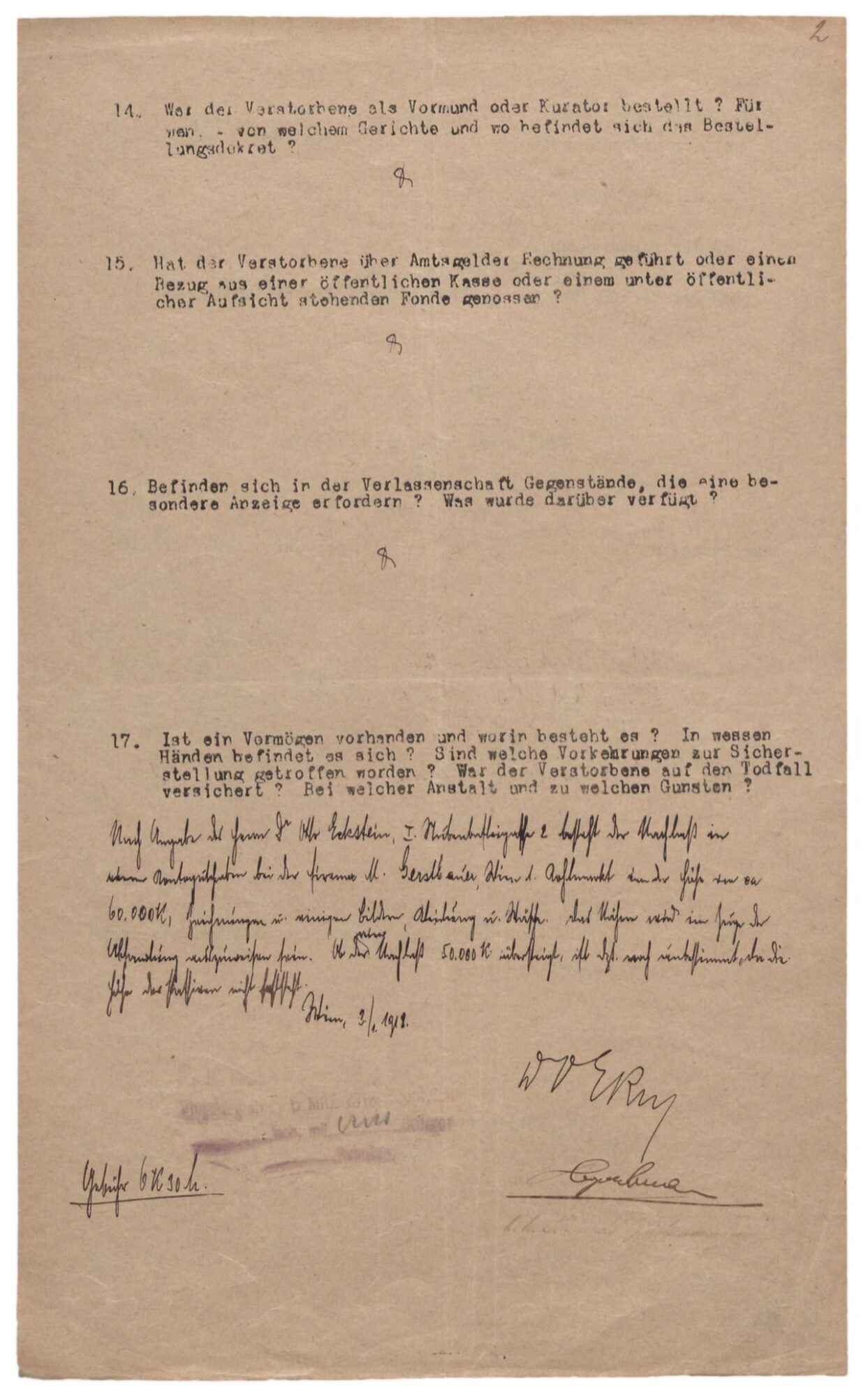

Contrary to his status as an internationally renowned artist, Klimt did not leave a sizeable fortune after his death. During his lifetime, the artist, who was renowned for his generosity, had to support not only himself but also his two unmarried sisters, his mother, his niece and her mother, as well as three women and their five illegitimate children. This, coupled with the financial hardships during the war years from 1914 to 1918, had prevented Klimt from accumulating any significant money reserves. In the death notice, the extent of his property was listed as follows: “60,000 crowns, drawings and several paintings, clothes and linen.”

The reserves in Klimt’s savings account with the banking house M. Gerstbauer only amounted to around 33,330 euros. Seeing as he had rented the apartment at Westbahnstraße 36 and the studio at Feldmühlgasse 9 (now no. 11), the properties were not included in the inheritable estate. Thus, his only assets of great value were the unfinished works, and those paintings and drawings he had not yet sold and left in his studio.

The legal heirs mentioned in the death notice included Klimt’s four living siblings, Georg, Hermine and Klara Klimt as well as Johanna Zimpel, and his niece Helene Klimt jun. As the only daughter of Klimt’s late brother Ernst, she was entitled to the share of the estate that would have gone to her father.

Death Notice of Gustav Klimt

-

Obituary of Gustav Klimt, 02/12/1918, Wiener Stadt- und Landesarchiv

Obituary of Gustav Klimt, 02/12/1918, Wiener Stadt- und Landesarchiv

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna -

Obituary of Gustav Klimt, 02/12/1918, Wiener Stadt- und Landesarchiv

Obituary of Gustav Klimt, 02/12/1918, Wiener Stadt- und Landesarchiv

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna -

Obituary of Gustav Klimt, 02/12/1918, Wiener Stadt- und Landesarchiv

Obituary of Gustav Klimt, 02/12/1918, Wiener Stadt- und Landesarchiv

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna -

Obituary of Gustav Klimt, 02/12/1918, Wiener Stadt- und Landesarchiv

Obituary of Gustav Klimt, 02/12/1918, Wiener Stadt- und Landesarchiv

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna

Distribution of the Inheritance

The exact distribution of the inheritance has not been handed down. However, lender labels – especially those that appeared on works featured in the large-scale memorial exhibitions held in 1928 and 1943 – as well as estate stamps, autographs and reports by Klimt’s contemporaries give us a rough idea about the division of his estate. According to a statement by the artist’s niece, it was Carl Moll who divided the drawings among the siblings and Emilie Flöge, who, by law, had no claim to the inheritance. The person in charge of Gustav Klimt’s estate was the lawyer Dr. Otto Ekstein.

Aside from a few individual works, all paintings from the estate were sold in 1919, and the proceeds split among the heirs. Klimt’s relatives likely selected and kept several individual items of personal value. This would explain why none of the siblings or members of the Flöge family sold any of these works during their lifetime.

Klimt’s correspondence, most of it unopened, was destroyed after his death. Thus, there are very few extant autographs addressed to the artist.

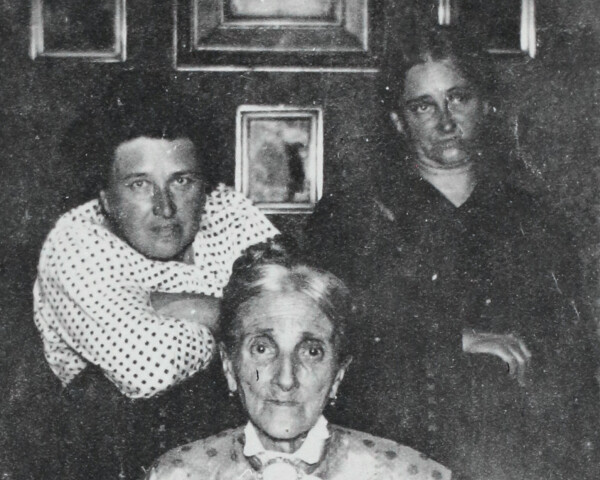

Hermine, Anna and Klara Klimt in the family apartment at Westbahnstraße 36 (detail)

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Hermine and Klara Klimt

Numerous sources indicate that the two sisters Hermine and Klara inherited several drawings, the painting of their mother Portrait of Anna Klimt (1897/98, whereabouts unknown), the three small-scale landscapes Tranquil Pond (probably 1881, private collection), Forest Floor (1881/82, Klimt-Foundation, Vienna) and Forest Interior (1881/82, Hida Takayama Museum of Art), as well as the portrait of their father painted by Ernst Klimt. They took over the lease of the apartment on Westbahnstraße and likely kept all the furniture, including items from the Wiener Werkstätte. While the portrait of the mother hung for a long time in the family’s living room above the dining table, the two unmarried women sold most of their brother’s drawings to keep afloat during the period of inflation. The drawings from their estate are still clearly identifiable today owing to the handwritten annotation “Nachlass meines Bruders Gustav Hermine Klimt” [“Estate of my Brother Gustav Hermine Klimt”]. Hermine probably looked after her own and her sister Klara’s portion of the inheritance. As the latter had been mentally unstable for some years, she was likely not in a position to manage her own affairs.

70th birthday of Anna Klimt with her family, 01/27/1906, ARGE Sammlung Gustav Klimt, Dauerleihgabe im Leopold Museum, Wien: Johanna Zimpel with her children at her mother's 70th birthday party, 1906

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

Johanna Zimpel

Gustav Klimt’s youngest sister also primarily inherited drawings. Only very few paintings entered into her possession. These included small-scale oil sketches from Klimt’s early school days, such as Male Nude to the Right (c. 1883, private collection), and several small boxes with miniatures on ivory. Johanna further received the majority of her brother’s personal items, including a signet, certificates, photographs and exotic art objects from the artist’s studio, among them a large red and black Samurai armor. When her two older sisters died in 1938, she inherited the Portrait of Anna Klimt, which subsequently hung in the living room of her apartment on Mollardgasse.

Johanna’s sons also showed an interest in their uncle’s estate. Her second eldest son, Rudolf Zimpel, looked after much of Klimt’s estate already during Johanna’s lifetime, labeling and selling parts of the collection. Many of the drawings, as well as the male nude, thus bear the stamp “Nachlass Gustav Klimt Sammlung R. Zimpel” [“Estate Gustav Klimt Collection R. Zimpel”] and, more rarely, “JOHANNA ZIMPEL” or the written annotation “Nachlass Gustav Klimt Zimpel Gustav” [“Estate Gustav Klimt Zimpel Gustav”]. The aforementioned Samurai armor was sold by Rudolf in 1945 to the steel company Böhlerwerke in Kapfenberg.

Georg Klimt

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

Georg Klimt

As far as we can tell today, Gustav’s brother Georg only inherited the furniture from Klimt’s studio, which he used in his own atelier on Neulinggasse, as well as several drawings. Among them was the chalk drawing said to depict the youngest Klimt sister Anna, who died as a child, as well as various naturalistic heads with the title “The Beautiful Viennese Woman,” which may be part of a hitherto undiscovered portfolio. Both Georg and his wife Franziska certified the drawings’ authenticity for buyers with the handwritten annotations: “Drawn by Gustav Klimt Georg Klimt” and “Drawings by Gustav Klimt authenticated Franziska Klimt.” After Georg’s death in 1931, Franziska inherited all her brother-in-law’s drawings. Time and again, she was forced to sell them due to financial difficulties, though she was not prepared to drop below a certain price. In December 1934, she wrote to the secretary of the Künstlerhaus:

“Would it be possible to grant me a humble subsidy? If agreeable, I would like to give a drawing by Gustav Klimt in return. If you find buyers for it, the piece must not be sold for under 100 shillings [N.B. 560 euros].”

Georg’s widow gifted all the drawings she did not sell during her lifetime to the Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien (now Wien Museum).

Helene Klimt with her cousin Gertrude Flöge in a rowing boat on Lake Attersee, around 1912

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Helene “Lentschi” Klimt

The role that Helene Klimt played in Gustav Klimt’s life went far beyond that of a niece. Klimt had taken over guardianship of Helene – lovingly called “Lentschi” – when she was still an infant. Thus, he was always more like a father than an uncle to the semi-orphan. Contemporaries also perceived their relationship this way, with an ill-informed journalist calling her “Fräulein Klimt – the daughter of the painter Gustav Klimt” in a newspaper article in 1912.

Attempting to determine her portion of the inheritance is particularly difficult, as she shared an apartment with her aunt Emilie. This makes it almost impossible to gauge which share of the estate belonged to Emilie and which part belonged to Helene. Additionally, Emilie had likely looked after Helene’s share for a while, as the latter had only just come of age when her uncle died.

However, there are some oil paintings that can be attributed without doubt as belonging to Helene Donner, née Klimt. Along with the portrait of herself as a young girl, which her mother had owned already during Klimt’s lifetime, she inherited at least one painting from the artist’s estate. In the memorial exhibitions held in 1928 and 1943, the landscape Birch on the Attersee (Calm Water) (1901, whereabouts unknown) is clearly labeled as belonging to Helene.

Latest since the passing of her aunt Emilie in 1952, Helene came into possession of the entire estate of the Flöge family, though it had been greatly diminished following a fire in 1945.

Emilie Flöge and Gustav Klimt in the garden of Villa Oleander, summer 1910, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

The Inheritance of the “Eternal Bride”

Even before the final settlement of Klimt’s estate, the artist’s contemporaries clearly believed that his long-standing companion Emilie Flöge should be one of the primary heirs. Josef Hoffmann, for instance, suggested already on 13 February 1918 that it would be best if the secretary of the Hagenbund, Josef Krzizek, sent the proceeds from the sale of the late artist’s drawings to Emilie Flöge.

Legally, Emilie wasn’t part of Klimt’s immediate family, but she was recognized by everyone as his closest companion. Unofficially, her role always went beyond that of his brother’s sister-in-law. Otto Wagner commented on 8 February 1918 about Klimt and Emilie’s relationship, for which there was little understanding at the time:

“I wrote a very nice letter today to Mirl (Klimt’s eternal bride). I find it pretty abhorrent that he never married her. I cannot make any sense of their relationship. 6 or 7 years ago, we were in Gastein together, and kept expecting them to make it official at any moment.”

Seeing as she wasn’t entitled to inherit by law, Emilie was not listed among Klimt’s heirs. Documents prove, however, that eminent paintings from the estate came into her possession. Whether Emilie had made a later claim to the inheritance or whether her niece had simply shared her portion of the estate with her can unfortunately no longer be ascertained today.

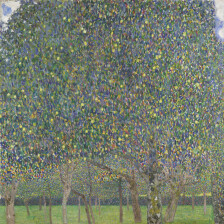

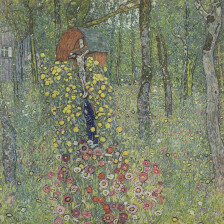

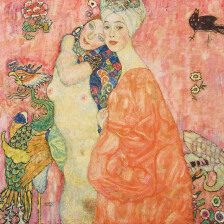

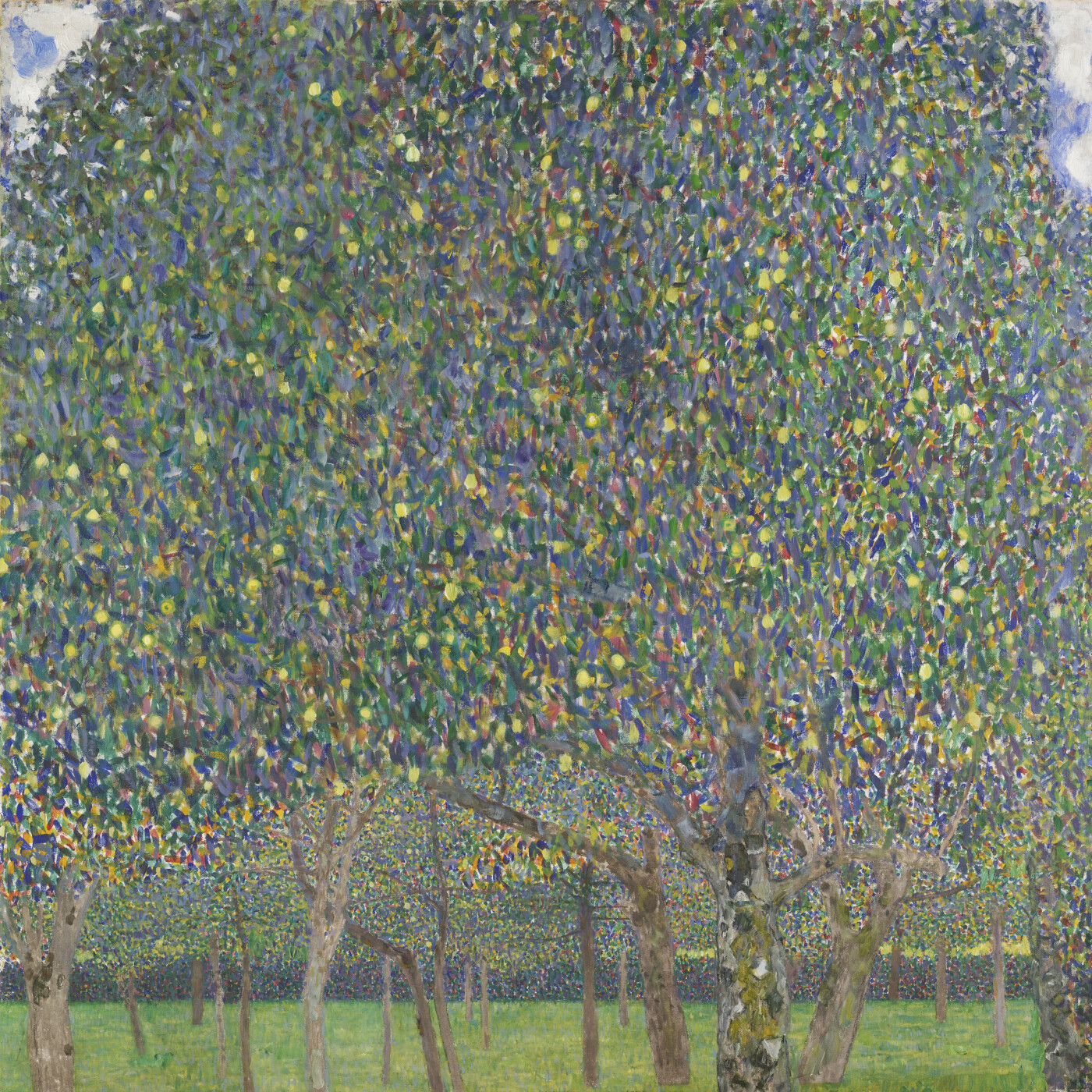

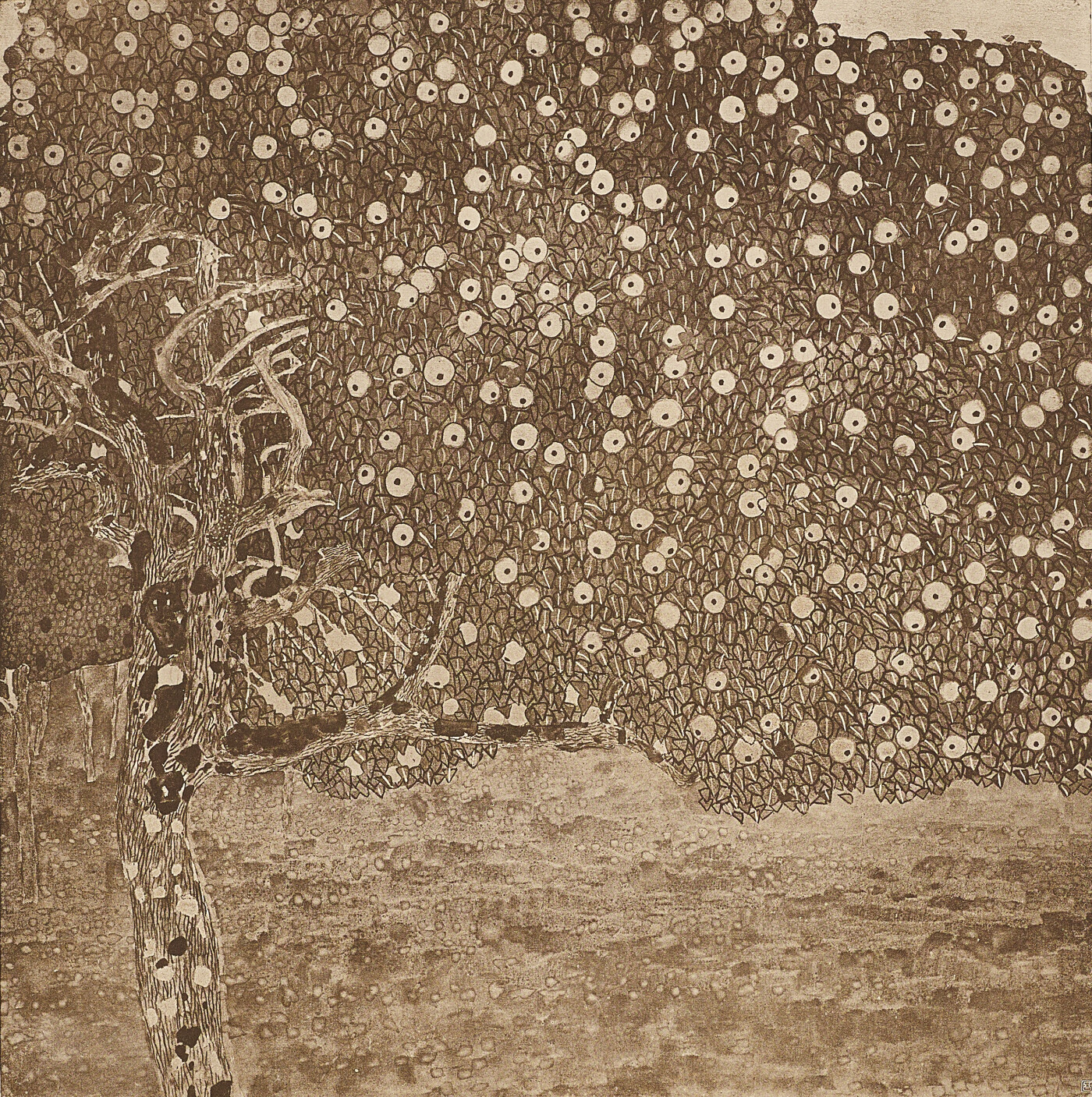

At any rate, along with several works Klimt had given to her while he was still alive, such as Orchard (c. 1898, Leopold Museum, Vienna) and Portrait of Pauline Flöge on Her Deathbed (1917, destroyed by fire in Vienna in 1945), Emilie was also in possession of paintings from the estate. We verifiably know that she owned The Black Bull (1900, private collection), Pear Tree (1903, Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Cambridge) as well as Klimt’s last large-scale allegory The Bride (1917/18, Klimt-Foundation). Many contemporaries probably thought it fitting that Emilie – who was often compared to Grillparzer’s eternal fiancée Kathi Fröhlich by acquaintances and referred to as the artist’s “eternal bride” – would receive an allegory of a bride as a last memento.

-

Gustav Klimt: Orchard, circa 1898, private collection

Gustav Klimt: Orchard, circa 1898, private collection

© Leopold Museum, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: The Black Bull, 1900, private collection

Gustav Klimt: The Black Bull, 1900, private collection

© Leopold Museum, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Pear Tree, 1903, Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Cambridge

Gustav Klimt: Pear Tree, 1903, Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Cambridge

© President and Fellows of Harvard College -

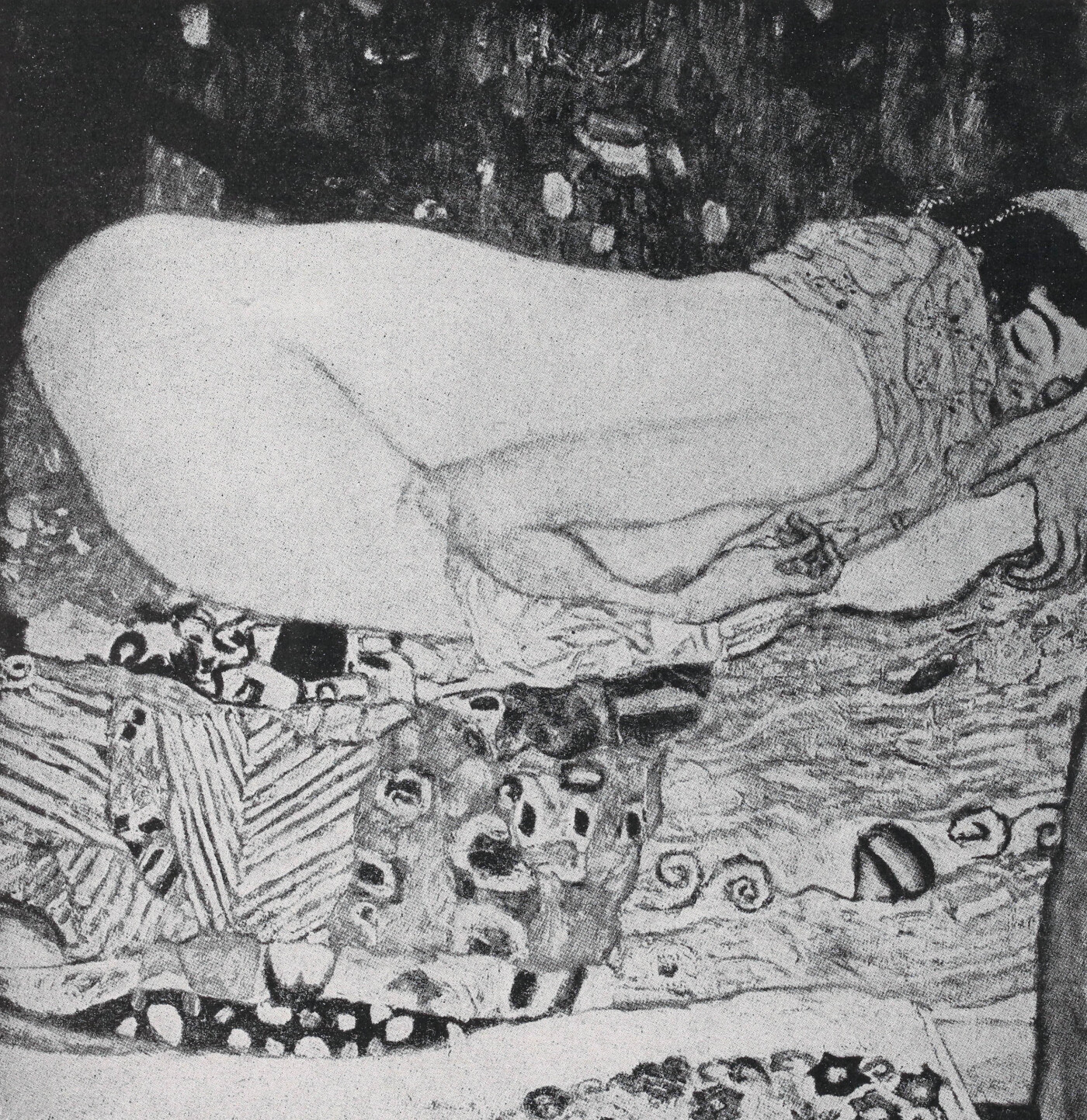

Gustav Klimt: The Bride, 1917/18, Klimt Foundation

Gustav Klimt: The Bride, 1917/18, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Emilie further owned a large amount of drawings, which she loaned to exhibitions and also sold to art dealers over the years. She had also taken over the lease of Klimt’s last studio in Hietzing. Egon Schiele, who wished to buy the studio of his revered role model, learnt from Felix Harta, whose mother-in-law was Klimt’s landlady:

“[...] that the Klimt house is rented out to Klimt’s heirs until February 1919. She [N.B. Harta’s mother-in-law] had promised Fräulein Flöge that she wouldn’t press her in any way to vacate the house, and that she wouldn’t terminate the lease agreement.”

It was also Emilie Flöge who signed the termination of the contract in February of that year. While the Wiener Werkstätte furniture kept there had gone to Georg Klimt, the majority of Klimt’s collection of Asian art, including kimonos, vases and scroll paintings, now belonged to the Flöge family. According to a contemporary report, Emilie stored these objects in the living quarters of the Casa Piccola, in a room that resembled a shrine and was known as “Klimt room.” The exotic dresses were aired out regularly, and the drawings – which included the sketches for the spandrels of the Imperial-Royal Kunsthistorisches Museum – were kept in folders and drawers. When the fashion salon closed down in 1938, the family moved into an apartment at Ungargasse 39 in the 3rd District of Vienna. The Klimt estate kept by the Flöge family was lost in a fire in 1945, when the apartment was destroyed by the events of war. Everything Emilie and Helene had failed to transfer to the Attersee during the war years was thus lost for posterity.

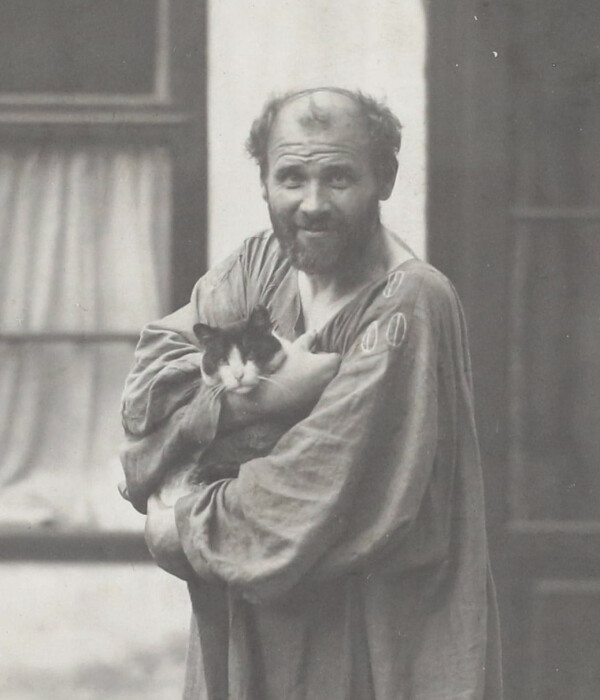

Moriz Nähr: Gustav Klimt with a cat in front of his studio in Josefstädter Straße, May 1911, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

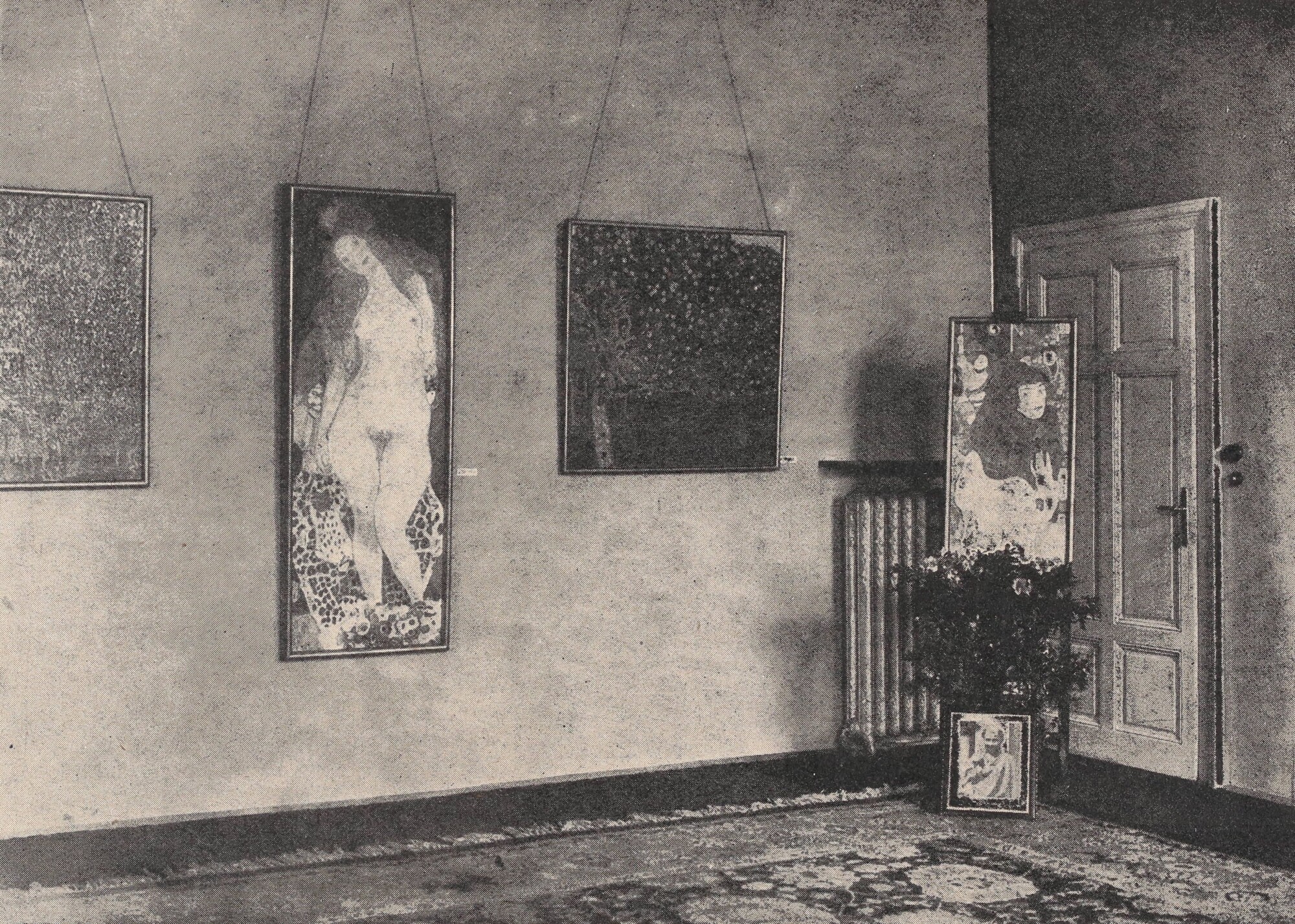

Estate Exhibition Organized by Gustav Nebehay

Likely to avoid disputes about the value of individual paintings, and to ensure a fair distribution of the estate, Klimt’s heirs decided to hold a sales exhibition of the remaining works in their possession. For this, the relatives turned to the art dealer Gustav Nebehay, who had been friends with Klimt and was himself a collector of the artist’s works.

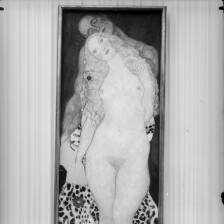

The exhibition, titled “Gedächtnis = Ausstellung Gustav Klimt” [“Memorial Exhibition”], opened on 6th February 1919. Its purpose was to sell the artist’s estate as favorably as possible. Along with some 20 paintings, it also featured numerous drawings, Klimt’s collection of Asian art and his library. The works were labeled with the stamp “GUSTAV KLIMT NACHLASS” [“GUSTAV KLIMT ESTATE”]. Klimt’s last large-scale paintings, including Baby (1917/18, National Gallery of Art, Washington), Gastein (1917, destroyed in a fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945), as well as the unfinished works Adam and Eve (1916–18, Belvedere, Vienna), Portrait of a Lady in White (1917/18, Belvedere, Vienna) and Garden Landscape with Rounded Mountaintop (Parsonage Garden) (1916, Kunsthaus Zug), were sold for enormous sums. According to newspaper reports, the market value of these late works, some of them unfinished, was many times higher than that of works sold during the artist’s lifetime:

“[…] the prices of these fragments and ruins exceeded the sum for which you could buy finished works by the master in his studio less than a year ago by five to six times. The total proceeds from the sale of these works likely equal what Klimt earned from his paintings during his entire lifetime. In the interest of his heirs, who have been left behind in modest financial circumstances, this is highly gratifying.”

Insight into the Gustav Klimt memorial exhibition, February 1919 - March 1919

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

The buyers of these works were mostly already established Klimt collectors, among them the Lederer and Primavesi families, and Sonja Knips. We do not know how exactly the proceeds were distributed among the heirs. What we do know for certain is that the closing of the sales exhibition did not mark the end of their cooperation with Gustav Nebehay. On 10 March 1919, Emilie Flöge wrote to Georg Klimt:

“Mr. Nebehay informs me that the exhibition is closed, but before he returns the unsold works he wants to make the following proposition: He would hold back some 300 drawings of different quality to keep selling them on behalf of Klimt’s heirs. [...] Please let me know if you are in agreement with this. Could you perhaps also talk to your sisters about it, and inform me of your decision soon?”

Maria Ucicka with her son Gustav Ucicky (detail) photographed by Karl Strempel, around 1900, Klimt Foundation, Vienna

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Maria Zimmermann with her son Gustav Zimmermann (detail) photographed by S. Fleck, around 1903, Klimt Foundation, Vienna

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Consuela Huber, Klimt Foundation, Vienna

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

This letter proves that both the Klimt siblings and the Flöge family participated in the sale of the estate, and that all of them turned to Nebehay in this matter.

Illegitimate Children and Inheritance Disputes

Though the settlement of inheritance claims appeared straightforward at first glance, it turned out to be more complicated than anticipated. Julius Zimpel – the son of Gustav’s younger sister Johanna – wrote in November 1918, nine months after the artist’s passing:

“The settlement of my uncle’s estate brought with it a series of unpleasant incidents and lawsuits, and no one knows how long this might drag on for.”

Julius Zimpel probably referred to the legal battle surrounding the inheritance claims made on behalf of Gustav Klimt’s illegitimate children.

The Zimmermann, Ucicky and Huber Families

Although the death notice listed no descendants – legitimate or illegitimate – there were three mothers who made claims to parts of the estate on behalf of their sons. Gustav Zimmermann, Gustav Ucicky, as well as Gustav and Wilhelm Huber were indeed Klimt’s illegitimate children, for whom he had been paying alimony. The three mothers – Consuela Huber, Marie Zimmermann and Maria Ucicky – probably came forward when a notice in the newspaper Wiener Zeitung was first published on 13 March 1918, asking for any claims to Gustav Klimt’s estate to be asserted and proven by 6 May at the district court of Neubau (7th District of Vienna). What ensued throughout the following months was a tug of war about proofs of paternity, demands and settlements. Several letters from Maria Zimmermann and Maria Ucicky to various lawyers prove that it was exceedingly difficult to ensure a share in the estate for an illegitimate child, and that this process required legal help.

In June 1919, the guardian of Gustav Zimmermann, Rudolf Eigner, made a claim of 10,000 crowns (c. 2000 euros) on his ward’s behalf. Maria Zimmermann had previously sent her personal letters to her lawyer to prove Gustav Klimt’s paternity. On 29 October 1919, more than a year after the artist’s death, the two Huber children (6 and 2 ½ years old) were awarded 5000 crowns – barely 1000 euros – each. Gustav Ucicky, who was already 20 years old, but at the time was still considered a minor until his 21st birthday, was to receive only 4000 crowns, which amounts to less than 850 euros in today’s money. The same sum was also offered to Gustav Zimmermann, who was of the same age. According to Dr. Ekstein, the heirs could not afford to pay more. The offer was to stand until 10 November. It wasn’t until December 1919 that the matter was settled once and for all. Gustav Zimmermann received 5000 crowns. While this was 1000 crowns more than initially offered, it was still only half of what he had hoped to receive.

Considering the enormous sums that the Flöge and Klimt families must have earned from the proceeds of the sales exhibition, the amounts the illegitimate children received appear more than meagre. Legally, they were indeed entitled only to a proportionate “maintenance settlement,” and their rights did not extend beyond monetary claims. None of them received any drawings, let alone paintings, from the estate. Gustav Ucicky would later try and redress this imbalance by purchasing his father’s works.

Further contents

Literature and sources

- Brief von Otto Kiebacher in Wien an Maria Zimmermann in Wien (19.12.1919). S64/262.

- Brief von Otto Kiebacher in Wien an Maria Zimmermann in Wien (10/29/1919).

- Aufkündigung des Mietvertrages für das Atelier Feldmühlgasse durch Emilie Flöge (before May 1919).

- Ausstellungsanmeldung von Emilie Flöge für „Die Braut“ anlässlich der VI. Kunstschau des Bundes Österreichischer Künstler im Künstlerhaus 1925 (09.04.1925). Mappe Gustav Klimt, .

- Empfangsbestätigung der Gesellschaft bildender Künstler Wiens an Emilie Flöge (13.03.1943). 1.A1.1943.01_050.

- Brief von Josef Krzizek an Emilie Flöge in Wien (13.02.1918).

- Brief von Emilie Flöge in Wien an Georg Klimt (10.03.1919). S104.

- Brief von Julius Zimpel jun. in Wien an Theodor Petermichel (11/06/1918). S499/4.

- Brief mit Kuvert von Felix Albrecht Harta in Salzburg an Egon Schiele in Wien (01.10.1918). ESA345.

- Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Emilie Flöge. Reform der Mode. Inspiration der Kunst, Vienna 2016.

- Vereinigung bildender KünstlerInnen Wiener Secession (Hg.): XCIX. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Wiener Secession. Klimt-Gedächtnis-Ausstellung, Ausst.-Kat., Secession (Vienna), 27.06.1928–05.08.1928, Vienna 1928.

- Christian M. Nebehay (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Dokumentation, Vienna 1969.

- Emil Pirchan: Gustav Klimt, Vienna 1956.

- Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Chiffre: Sehnsucht – 25. Gustav Klimts Korrespondenz an Maria Ucicka 1899–1916, Vienna 2014.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band I, 1878–1903, Salzburg 1980.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band IV, 1878–1918, Salzburg 1989.

- Wolfgang Georg Fischer: Gustav Klimt und Emilie Flöge III. Erinnerungen an Emilie Flöge, in: Alte und moderne Kunst. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Kunst, Kunsthandwerk und Wohnkultur, 26. Jg., Heft 190/191 (1983), S. 57.

- Rose Poor Lima: Besuch bei Hermine und Klara Klimt, in: Wiener Zeitung, 22.10.1933, S. 14-15.

- Münchner neueste Nachrichten: Wirtschaftsblatt, alpine und Sport-Zeitung, Theater- und Kunst-Chronik (Morgenausgabe), 28.03.1919, S. 1.

- Bertha Zuckerkandl: Gedächtnis=Ausstellung, in: Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, 06.02.1919, S. 2-3.

- N. N.: Gedächtnisausstellung Gustav Klimt, in: Die Frau, 26.02.1919, S. 5.

- N. N.: Beilage, in: Die bildenden Künste. Wiener Monatshefte, 2. Jg. (1919), S. VII.

Commemorating Gustav Klimt

Max Eisler: Gustav Klimt, Vienna 1920.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Arthur Roessler: In Memoriam Gustav Klimt, Vienna 1926.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Emil Pirchan: Gustav Klimt. Ein Künstler aus Wien, Vienna - Leipzig 1942.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

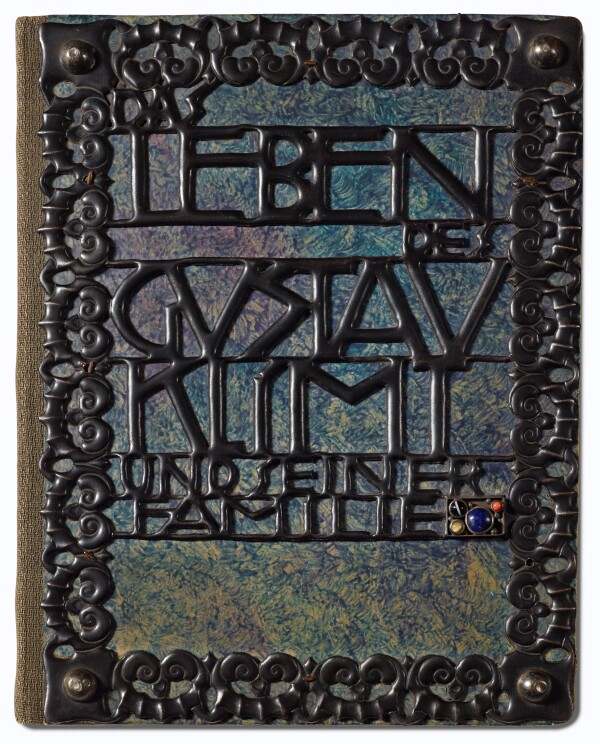

Georg Klimt: Chronicle of the life of the Klimt family, 1924, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

After Klimt’s death, a number of renowned contemporaries made it their task to put the artist of the century’s life and work down in writing. In addition to monographs and publications by Max Eisler, Emil Pirchan, and Arthur Roessler, it was above all the so-called “Klimt Chronicle” by Georg Klimt that gained special importance.

Max Eisler’s “Gustav Klimt”

The Austrian art historian and lecturer Max Eisler was among the first to dedicate a comprehensive monograph to Gustav Klimt, which appeared in 1920 with the publishing house of the Austrian State Press. Its publication was already announced in the spring of the previous year. In this context, Die Zeit wrote on 19 April 1919:

“The German-Austrian State Press intends to come out with a high-quality and elegantly designed publication on Gustav Klimt consisting of 50 pages of text and 25 plates in the quarto format, including three color collotypes, based on the master’s original drawings and paintings. University lecturer Dr. Max Eisler is responsible for the text and the selection of images.”

According to the press release, a unique hand-numbered premium edition was planned, which would be sold for 90 crowns. After a subscription period, the price would increase substantially. In the end, the edition comprised 500 copies, which, different from the announcement, contained more than 30 plates. The first fifty copies featured a gold-embossed leather binding, whereas the rest came with a gold-embossed cardboard binding.

According to a review that appeared in the Wiener Zeitung, Eisler’s monograph seems to have been presented to the public toward the end of 1920 within the framework of a small book exhibition at the Vienna Secession’s “Ver Sacrum Room.” In said article, journalist Rudolf Holzer reviewed the publication on Gustav Klimt as follows:

“Let us put it plainly: this is not merely a precious book; as such it is also the first art historically critical presentation of Gustav Klimt’s complete oeuvre that has ever been compiled.”

In 1931, Max Eisler published another catalogue raisonné on Gustav Klimt in the form of the portfolio Gustav Klimt. Eine Nachlese [“Gustav Klimt. Afterthoughts”]. It should again appear as a limited edition, but this time in German, English, and French.

In Memoriam Gustav Klimt

In 1926, the booklet In Memoriam Gustav Klimt was printed by the studio Officina Vindobonensis on high-quality paper in a small edition on behalf of the Österreichischer Werkbund. The author of this work, which comprised only a few pages, was the Austrian writer Arthur Roessler. He reminisced Klimt’s greatest “scandals,” including Nuda Veritas (1899, Theatermuseum, Vienna) and the three Faculty Paintings. The publication presumably harked back to a journalistic contribution by Roessler that partly made reference to statements coming from Ludwig Hevesi, and which was published on the occasion of Klimt’s death in the Arbeiter-Zeitung on 10 February 1918. Furthermore, it might be assumed that a lecture about Gustav Klimt, which Roessler held at the Vienna Urania’s Volksbildungshaus in 1925, provided the basis for In Memoriam Gustav Klimt.

Gustav Klimt – An Artist from Vienna

During World War II, the biography Gustav Klimt. Ein Künstler aus Wien [“Gustav Klimt. An Artist from Vienna”] appeared in 1942, having been written by the versatile artist Emil Pirchan. In 1956, an extended edition was to be published, including additional information. Whereas in his Klimt monograph Eisler placed his focus on an art historical description of the painter’s career, Pirchan, in his richly illustrated publication, revealed biographic details, most of which were conveyed in the form of anecdotes. According to Pirchan’s own words, the biography was mainly based on memories and information supplied by Rudolf Bacher, Emilie Flöge, Josef Hoffmann, Georg Klimt’s widow Franziska Klimt, Moriz Nähr, Carl Moll, Michael Powolny, Mäda Primavesi, Klimt’s illegitimate son Gustav Ucicky, and Klimt’s sister Johanna Zimpel.

The Life of Gustav Klimt and His Family

The life and work of Gustav Klimt was also documented in retrospect by his brother, Georg Klimt, in the so-called “Klimt Chronicle” (Klimt-Foundation, Vienna). This comprehensive calligraphed work, which also contains numerous photographs and autographs, has a specially designed cover page adorned with iron ornaments. In 1929, the journalist Leopold Wolfgang Rochowanski wrote about the specific motive for its production on the occasion of a visit to Georg Klimt’s studio:

“Georg Klimt first of all seeks to put right all false information, all kinds of misinterpretations that have circulated, the numerous minor inaccuracies and grave errors in books and essays about his brother, so as to hold up the truth. […] He has spent a long time keeping records about all of his memories.”

After his death in 1931, the chronicle, which Georg Klimt had not yet wished to make available to the public during his lifetime, came into the possession of his wife, Franziska “Fanny” Klimt. What is particularly interesting in this context is a newspaper article in the Kleine Volks-Zeitung of 30 June 1942, which mentions that Georg Klimt’s widow owned “two thick scrapbooks” compiled by Georg Klimt. This sole reference to a second part of the chronicle could not be verified by research to date.

Literature and sources

- Max Eisler: Gustav Klimt, Vienna 1920.

- Max Eisler (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Eine Nachlese, Vienna 1931.

- Emil Pirchan: Gustav Klimt. Ein Künstler aus Wien, Vienna - Leipzig 1942.

- Emil Pirchan: Gustav Klimt, Vienna 1956.

- Arthur Roessler: In Memoriam Gustav Klimt, Vienna 1926.

- Neues Wiener Journal, 13.01.1929, S. 18-19.

- Chronik über das Leben der Familie Klimt, "DAS LEBEN DES GUSTAV KLIMT UND SEINER FAMILIE" (1924). S16/1.

- Wiener Zeitung, 28.11.1920, S. 2-4.

- Neues Wiener Journal, 08.12.1925, S. 19.

- Kleine Volks-Zeitung, 30.06.1942, S. 5.

- Belvedere. llustrierte Zeitschrift für Kunstsammler, Band 8 (1925).

- Der Cicerone. Halbmonatsschrift für die Interessen des Kunstforschers & Sammlers, 13. Jg., Heft 18 (1921), S. 533.

- Die Zeit, 19.04.1919, S. 6.

- Neue Freie Presse (Morgenausgabe), 29.12.1920, S. 8.

- Neues Wiener Tagblatt (Tagesausgabe), 26.07.1942, S. 3.

Exhibition in Commemoration of Klimt

Vereinigung bildender KünstlerInnen Wiener Secession (Hg.): XCIX. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Wiener Secession. Klimt-Gedächtnis-Ausstellung, Ausst.-Kat., Secession (Vienna), 27.06.1928–05.08.1928, Vienna 1928.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

In the summer of 1928, an exhibition was held at the Vienna Secession on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of Gustav Klimt’s death. It was initiated and compiled by some of his closest artist-companions, headed by Carl Moll.

In 1928 – ten years after Klimt’s death – long-time friends and admirers of the painter suggested organizing a big commemorative exhibition. According to Carl Moll, they thus wished to remember him publicly, reminding people of “his pure sense of art, his unique approach, his incredible taste, and his superior virtuosity […].” The exhibition committee was made up of altogether nine renowned personalities from the spheres of art, culture, and politics of those days, including, apart from Carl Moll, Anton Hanak, Josef Hoffmann, and Berta Zuckerkandl. It was presided by Vienna’s city councilor Julius Tandler.

“A treasury full of painted jewels”

On 27 June 1928, the “XCIX. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Wiener Secession. Klimt Gedächtnis-Ausstellung” [“19th Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists Vienna Secession. Exhibition in Commemoration of Klimt”] opened officially and, according to an article in the Arbeiter-Zeitung, ended on 5 August 1928 – five days later than originally planned – with a festive closing event.

The organizers succeeded in assembling altogether more than 75 works for the show, including the three controversial Faculty Paintings, as well as numerous original drawings, all of which were presented in seven exhibition rooms at the Vienna Secession. Second to the “Kollektiv-Ausstellung Gustav Klimt” [“Gustav Klimt Collective Exhibition”] of 1903, the “Exhibition in Commemoration of Klimt” was thus the hitherto most comprehensive public presentation of Gustav Klimt’s artistic oeuvre at a single venue. On 8 July 1928, Hans Ankwicz-Kleehoven, the then-art reviewer of the Wiener Zeitung, wrote in this context that visitors, due to the unique variety offered, had the feeling “[…] to dwell in a treasury of painted jewelry, to be surrounded by gems of art more delightful than what has ever been created in Vienna.”

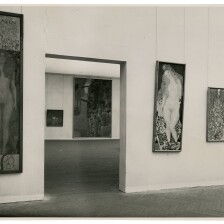

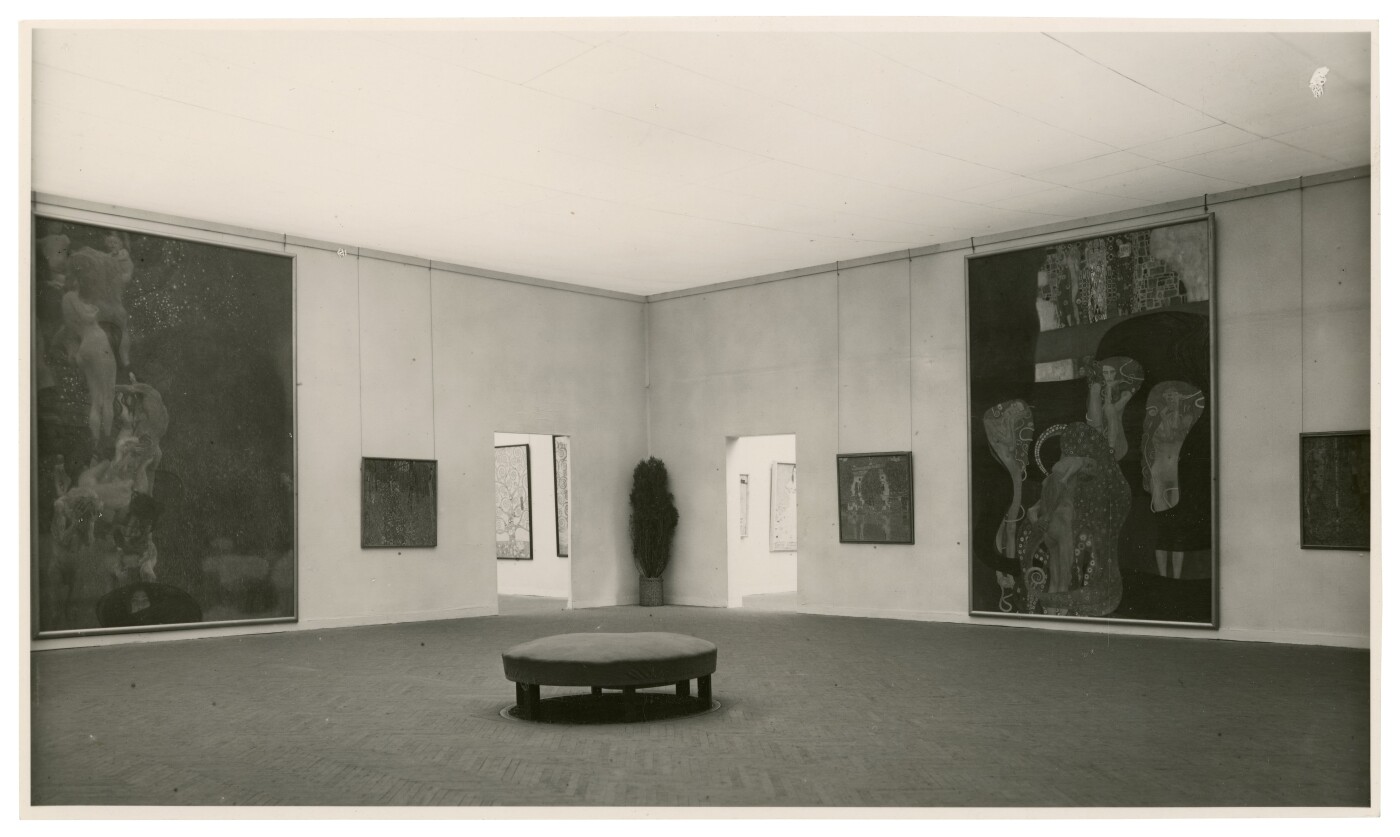

Julius Scherb (?): Insight into the 1928 memorial exhibition, June 1928 - August 1928, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

The majority of the works on display had been made available by such private collectors as industrial tycoon Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer or by Klimt’s niece Helene Donner. Individual lenders made use of the event as a selling platform. According to the exhibition catalog, Poppies in Bloom (1907, Belvedere, Vienna) and Portrait of Mäda Primavesi (1913, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) were officially offered for sale.

Photographic Documentation

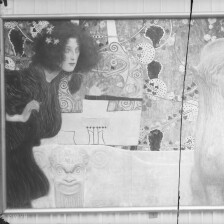

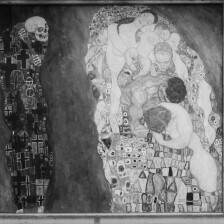

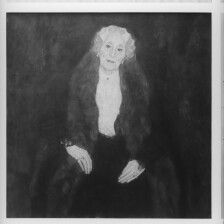

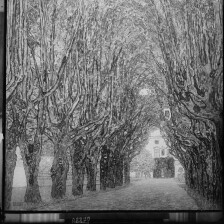

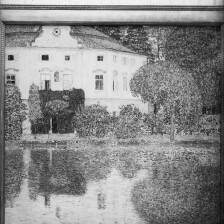

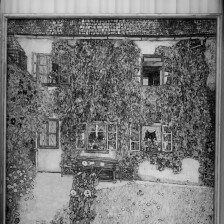

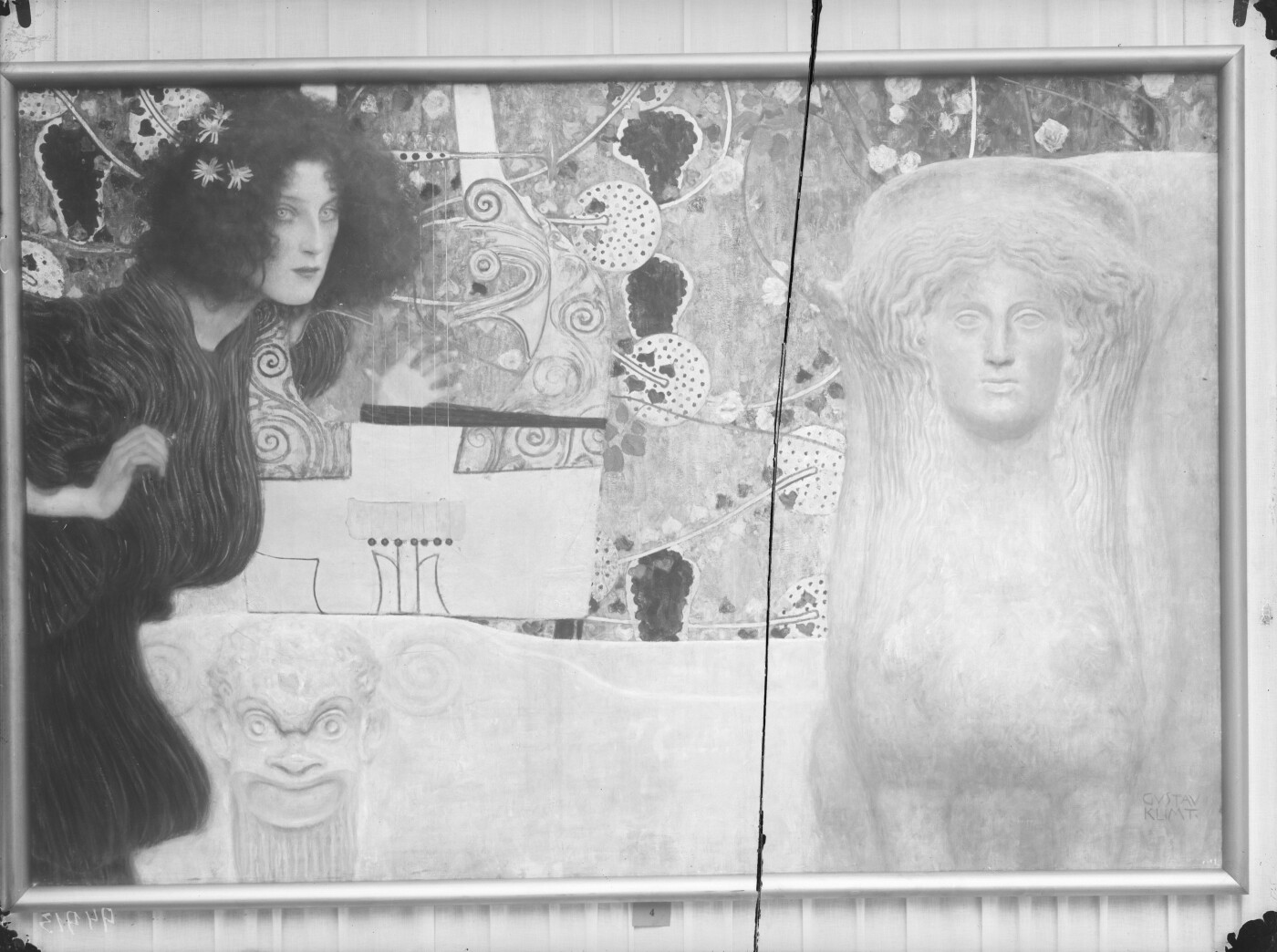

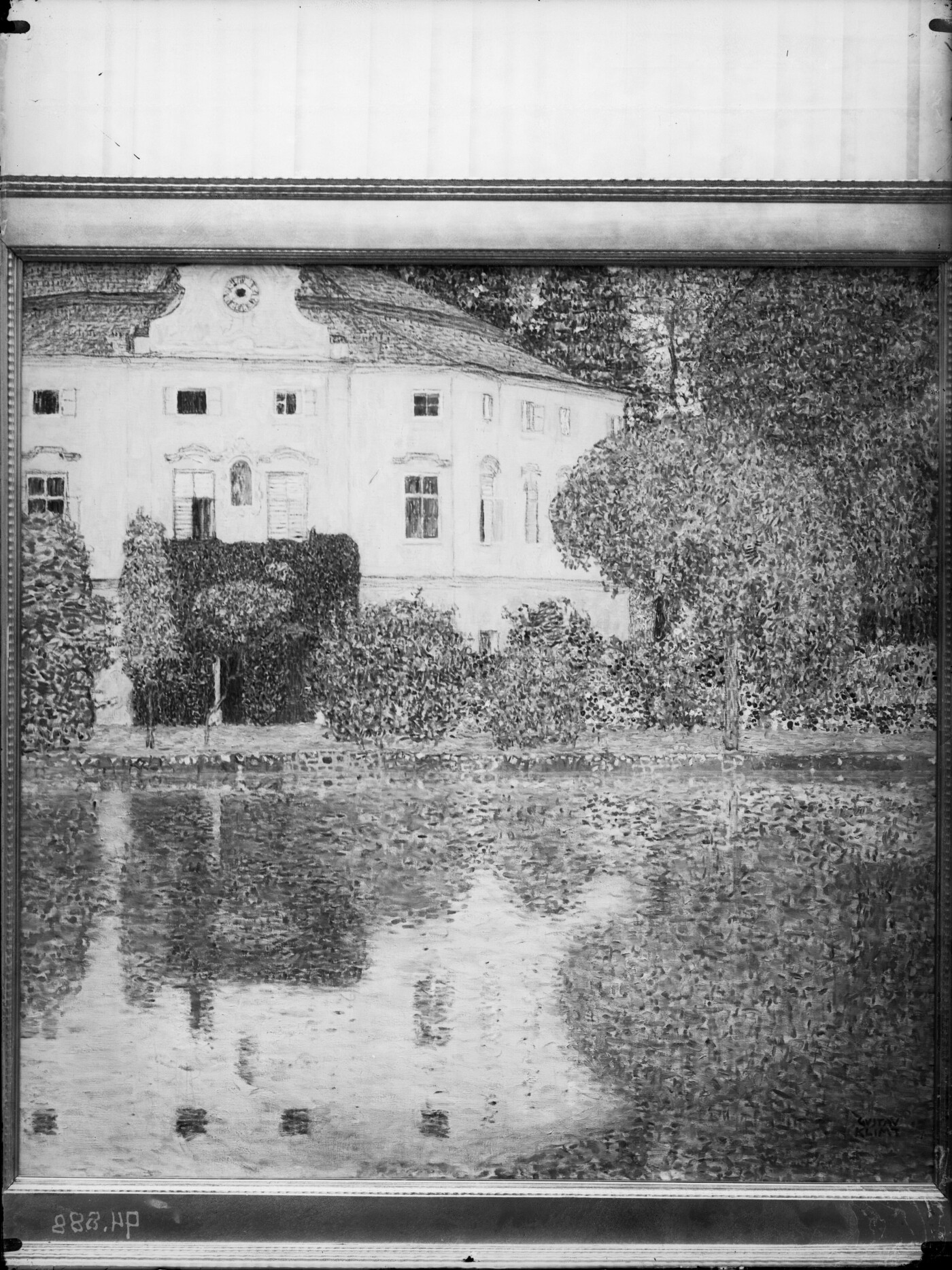

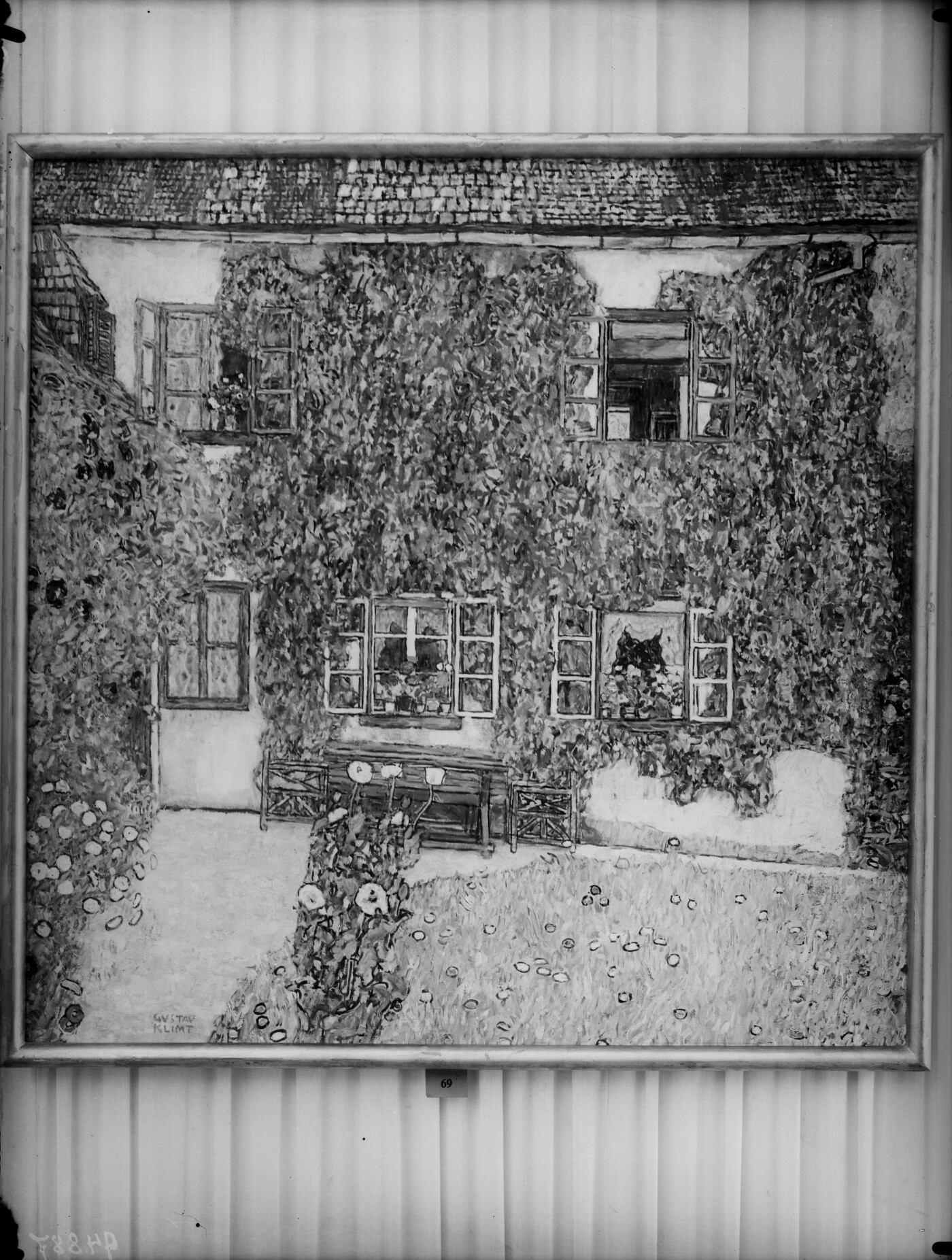

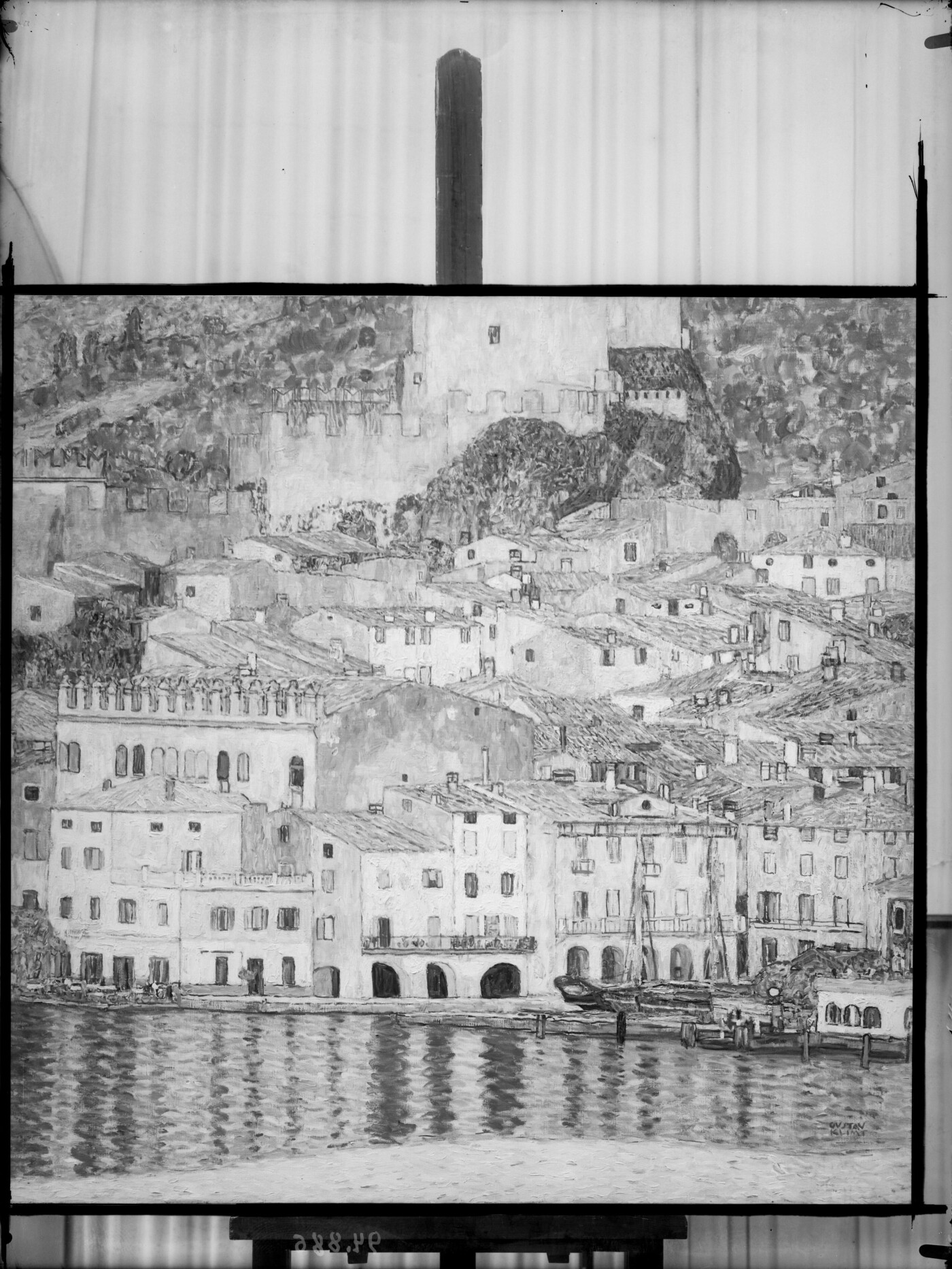

In his article, which was several pages long, Hans Ankwicz-Kleehoven regretted that due to the lack of time and high production costs it had not been possible to seize the unique opportunity and photograph all of the paintings on view for the first time for the exhibition catalog. However, Moriz Nähr documented individual works photographically during the preparations for the exhibition, including the late works Portrait of Charlotte Pulitzer (1917, unknown whereabouts, considered lost since the end of the war in 1945) and Forester’s House in Weißenbach on the Attersee II (1914, Neue Galerie New York, Estée Lauder Collection). Three years later, these photographs were used for the portfolio Gustav Klimt. Eine Nachlese by Max Eisler.

Artwork Photographs by Moriz Nähr

-

Moriz Nähr: The music, June 1928 - August 1928, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

Moriz Nähr: The music, June 1928 - August 1928, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library -

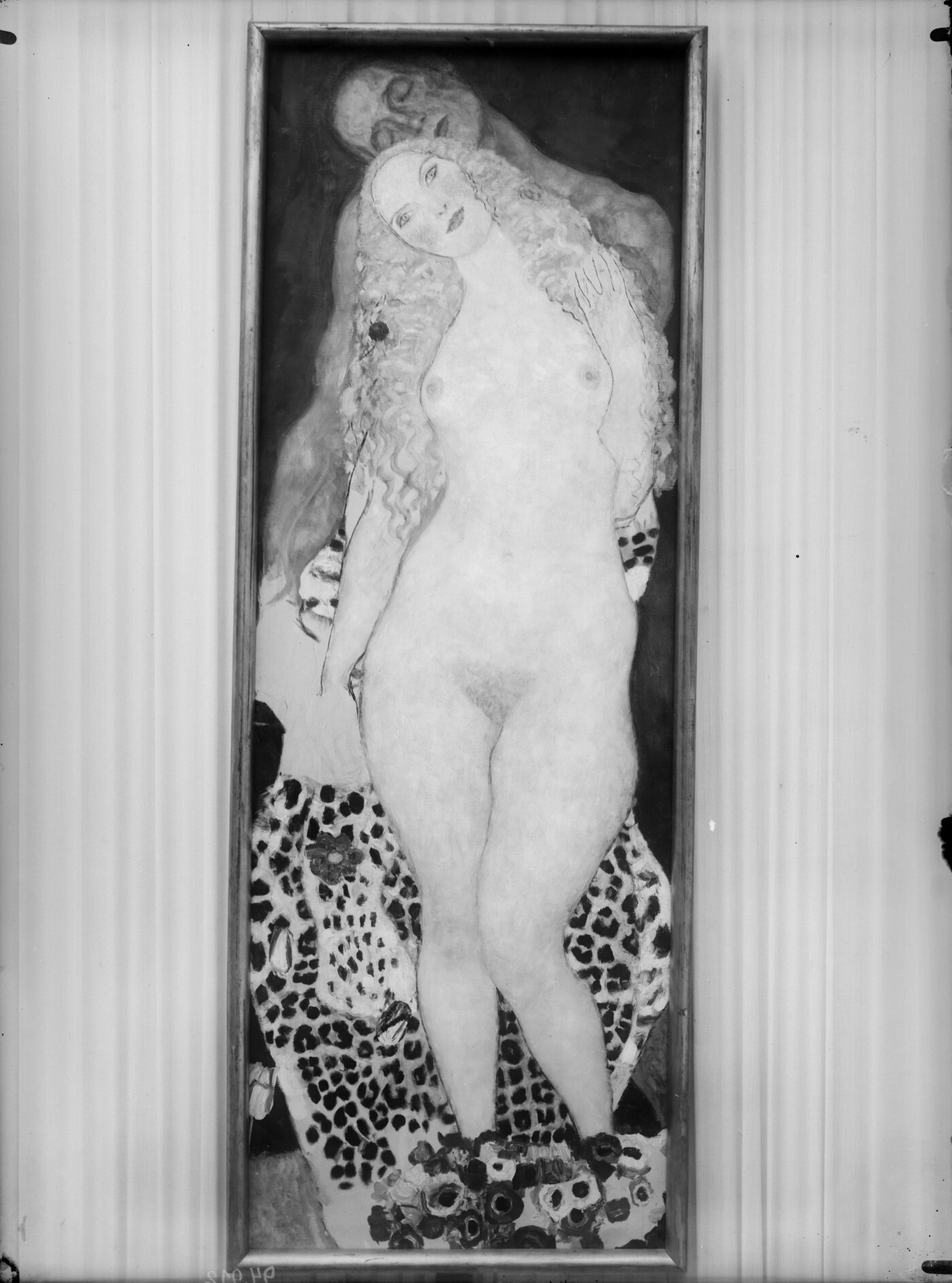

Moriz Nähr: Adam and Eve, June 1928 - August 1928, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

Moriz Nähr: Adam and Eve, June 1928 - August 1928, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library -

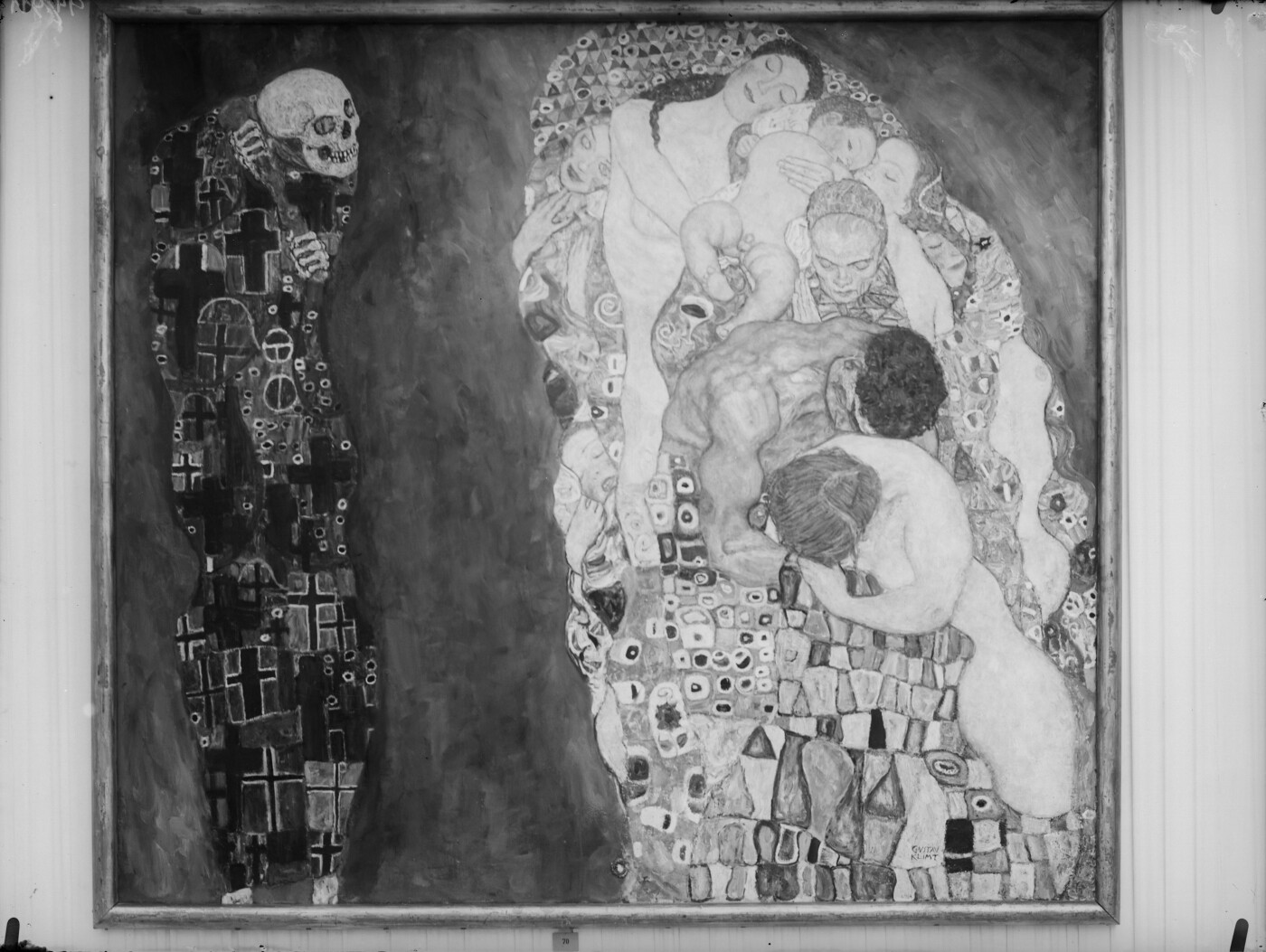

Moriz Nähr: Death and life (Death and love), June 1928 - August 1928, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

Moriz Nähr: Death and life (Death and love), June 1928 - August 1928, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library -

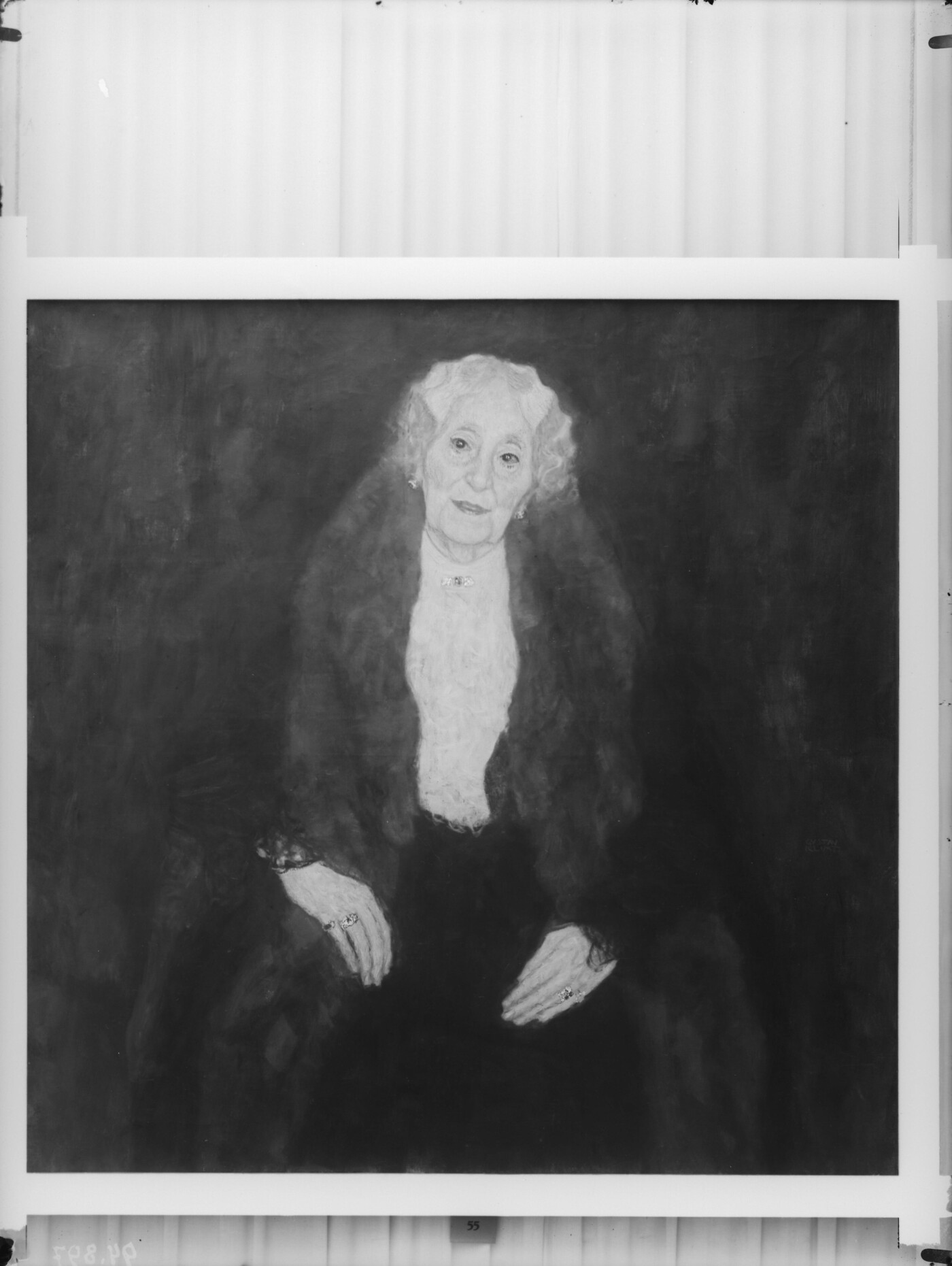

Moriz Nähr: Portrait of Charlotte Pulitzer, June 1928 - August 1928, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

Moriz Nähr: Portrait of Charlotte Pulitzer, June 1928 - August 1928, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library -

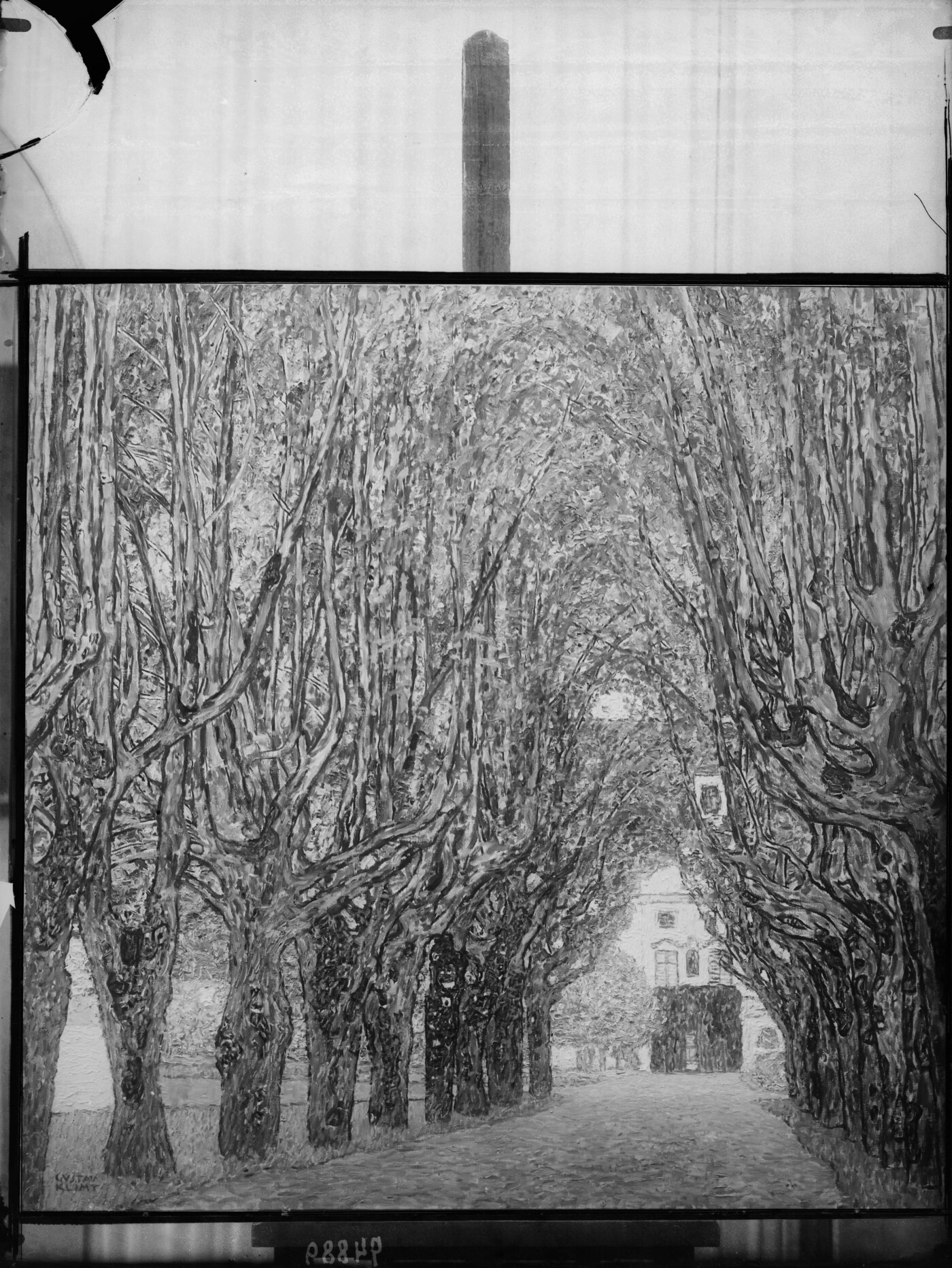

Moriz Nähr: Alley in front of Schloss Kammer am Attersee, June 1928 - August 1928, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

Moriz Nähr: Alley in front of Schloss Kammer am Attersee, June 1928 - August 1928, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library -

Moriz Nähr: Kammer am Attersee Castle IV, June 1928 - August 1928, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

Moriz Nähr: Kammer am Attersee Castle IV, June 1928 - August 1928, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library -

Moriz Nähr: Forester's lodge in Weissenbach am Attersee, June 1928 - August 1928, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

Moriz Nähr: Forester's lodge in Weissenbach am Attersee, June 1928 - August 1928, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library -

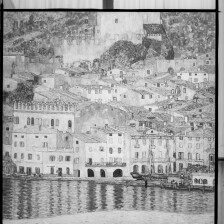

Moriz Nähr: Malcesine on Lake Garda, June 1928 - August 1928, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

Moriz Nähr: Malcesine on Lake Garda, June 1928 - August 1928, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Press Reviews

Only few daily newspapers and art magazines wrote about the “Exhibition in Commemoration of Klimt.” However, press coverage also comprised critical reviews of Klimt’s artistic oeuvre. For example, the Reichspost wrote on 2 July 1928:

“His technical skills, his enormously cultivated taste in terms of color, and the wonderful elegance of his draftsmanship deserve absolute recognition and admiration. But also the dark side of his artistic peculiarity reveals itself with shocking explicitness. Klimt’s art from the later years has something exaggeratingly sensitive about it, an almost pathological streak.”

On the other hand, the Austrian Arbeiter-Zeitung and the Neue Freie Presse published favorable reviews praising Gustav Klimt’s artistic work and the exhibition extensively. The latter wrote on 27 June 1928:

“Even those only halfway interested in the visual arts simply have to go and see this exhibition, at least because it will not be possible to compile a similar one in the foreseeable future and probably never again […].”

Internationally, though, the exhibition went largely unnoticed. Carl Moll commented upon this critically in an article penned by himself for the Neue Freie Presse, which appeared in November 1928. He expressed his disappointment about the press and art circles in Germany, as it “has ever since become a habit in Germany to shrug Klimt off […].” For Moll, the commemorative exhibition was an experience that “made us aware of what we had and what we lost in Klimt, for it was proof that his art has not been surpassed and has remained unparalleled up to now.”

Literature and sources

- Vereinigung bildender KünstlerInnen Wiener Secession (Hg.): XCIX. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Wiener Secession. Klimt-Gedächtnis-Ausstellung, Ausst.-Kat., Secession (Vienna), 27.06.1928–05.08.1928, Vienna 1928.

- Die Bühne. Wochenschrift für Theater, Film, Mode, Kunst, Gesellschaft, Sport, 5. Jg., Heft 193 (1928), S. 20-21.

- Moderne Welt, 9. Jg., Heft 28 (1928), S. 14-16.

- Der Cicerone. Halbmonatsschrift für die Interessen des Kunstforschers & Sammlers, 20. Jg., Heft 14 (1928), S. 488.

- Die Kunst für Alle. Malerei, Plastik, Graphik, Architektur, 44. Jg. (1928/29), S. 1-5.

- Der Tag, 28.06.1928, S. 7.

- Salzburger Volksblatt: unabh. Tageszeitung f. Stadt u. Land Salzburg, 12.07.1928, S. 5.

- Neues Wiener Journal, 28.06.1928, S. 6.

- Wiener Zeitung, 08.07.1928, S. 1-3.

- Reichspost, 02.07.1928, S. 3.

- Arbeiter-Zeitung, 04.07.1928, S. 3-4.

- Arbeiter-Zeitung, 04.08.1928, S. 4.

- Neue Freie Presse, 27.06.1928, S. 1-3.

- Neue Freie Presse, 30.11.1928, S. 1-3.

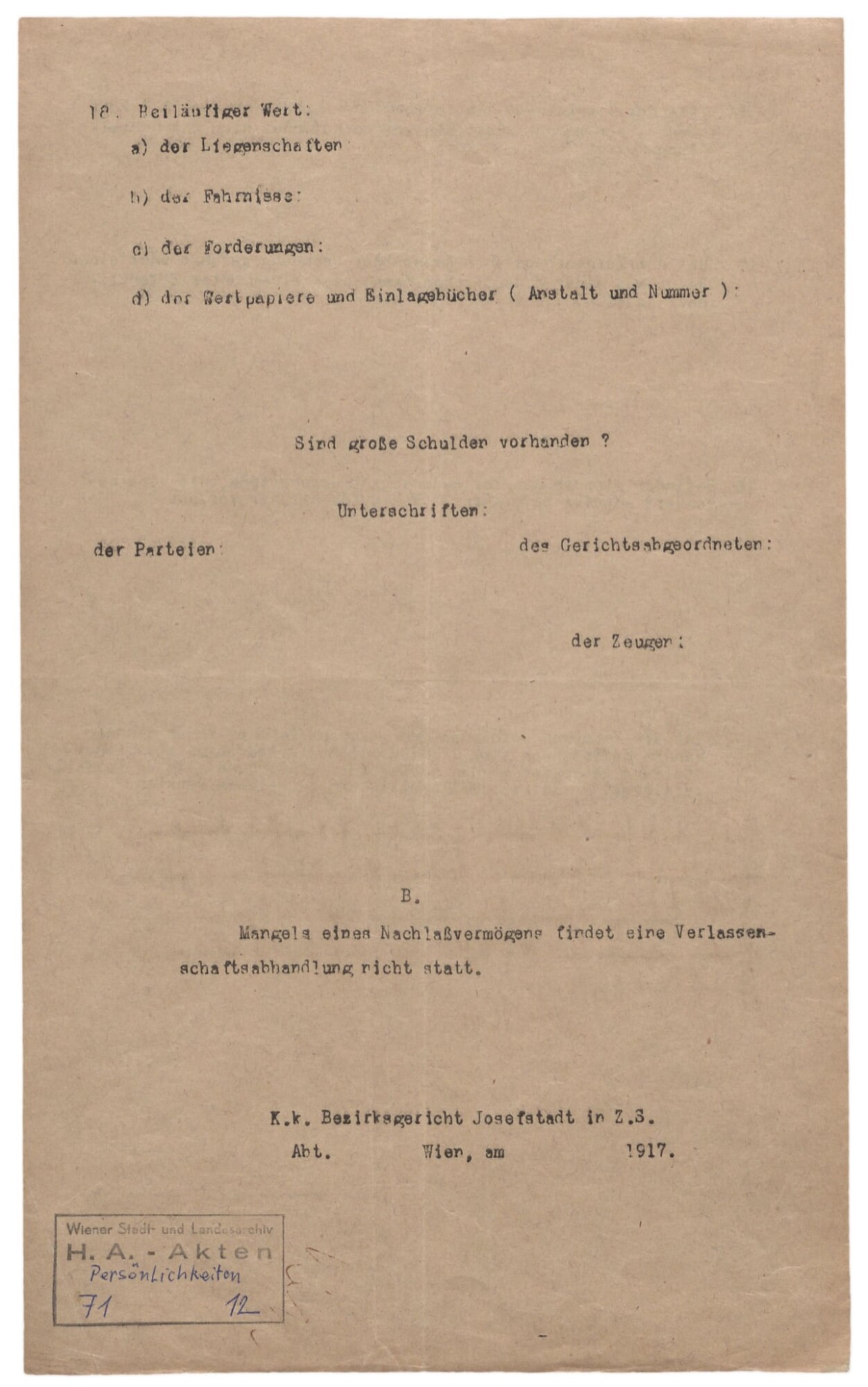

Show at Ausstellungshaus Friedrichstraße

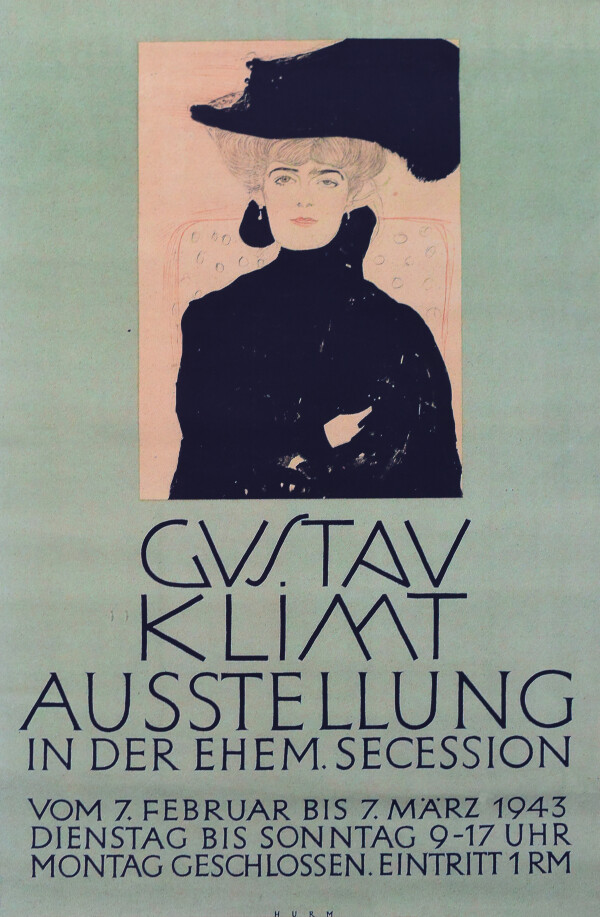

Poster of the Gustav Klimt memorial exhibition, 1943, private collection

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

In the spring of 1943, with World War II still in full swing, a big Klimt retrospective exhibition was held at Ausstellungshaus Friedrichstraße, the former Secession building. The show, which had been organized with some delay to mark the artist’s 80th birthday, took place under the auspices of Vienna’s Reichsstatthalter Baldur von Schirach.

In 1942, Reich Governor Baldur von Schirach entrusted Bruno Grimschitz, director of the Austrian Gallery, with the planning and organization of a comprehensive Klimt retrospective. It seems that apart from National Socialist culture and war propaganda, a crucial impulse for the envisaged Klimt show was provided by Emil Pirchan’s recently published Klimt monograph. The exhibition was to be held at the Vienna Secession, which had meanwhile been renamed Ausstellungshaus Friedrichstraße.

Exhibits and “Lenders”

The exhibition, which was on for several weeks, opened 25 years after Klimt’s death on 7 February 1943, comprising more than 40 paintings and numerous drawings by this “artist of the century.” A large number of the objects on view were loans made available by several renowned state institutions explicitly mentioned in the acknowledgements of the exhibition catalog. In addition, some of the works were provided by private owners, such as Sonja Knips and Klimt’s illegitimate son, film director Gustav Ucicky.

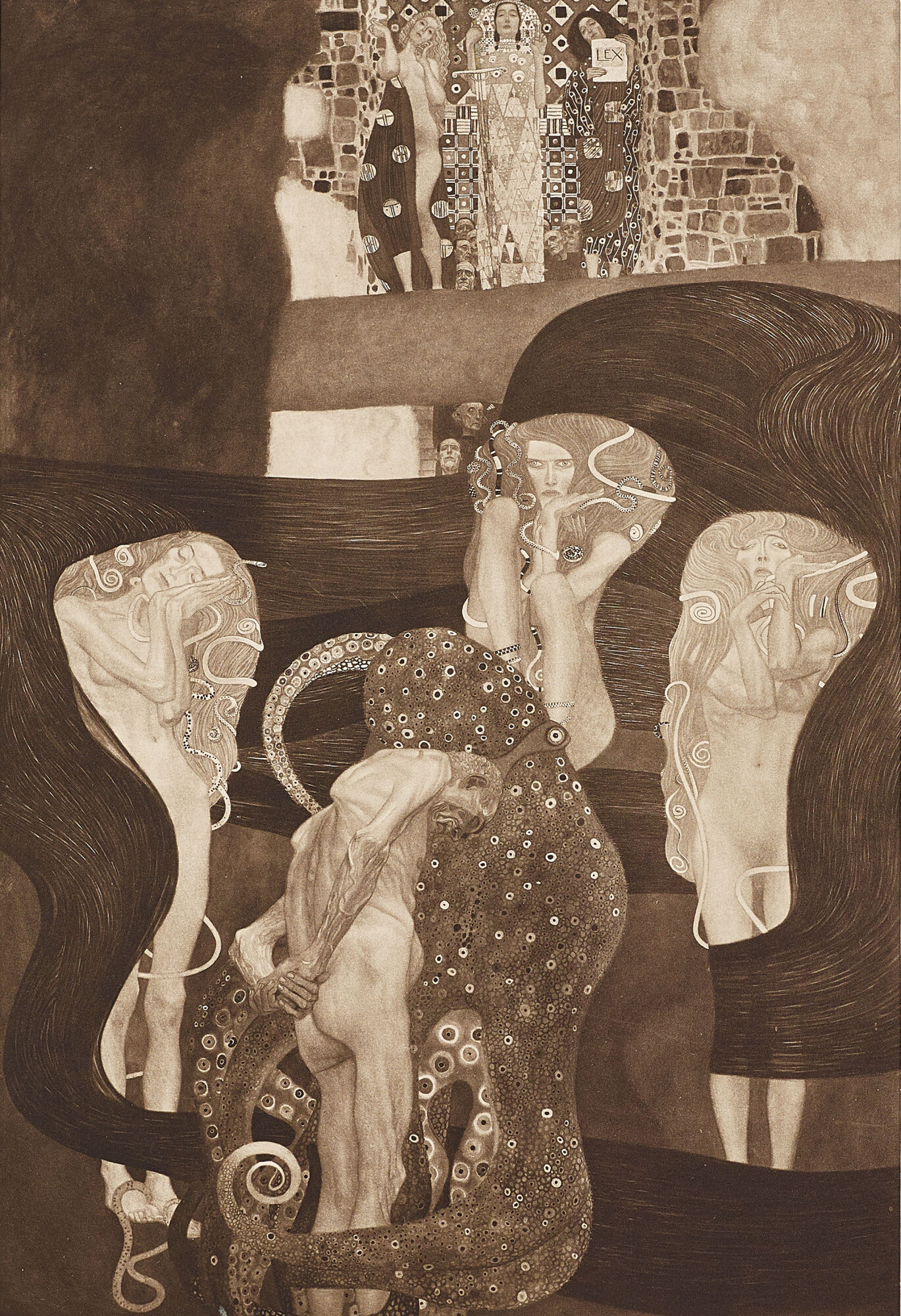

However, many of the paintings from private collections mentioned in the catalog originally came from dispossessed owners who had been forced to have their possessions auctioned off or whose possessions had been seized by the authorities. For example, the exhibition presented a large number of works that originally belonged to the Lederer Collection, including the two Faculty Paintings Medicine (1900–1907, destroyed) and Jurisprudence (1903–1907, destroyed). To conceal these circumstances, the titles of the works had partly been changed in order to obscure ownership conditions or provenances. This specifically concerned Klimt’s portraits of Jewish female sitters, which in the exhibition catalog were merely listed as “Ladies’ Portraits.”

Friedrichstraße exhibition center, formerly Association, after the "Anschluss"

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Glimpses of the Commemorative Exhibition of 1943

-

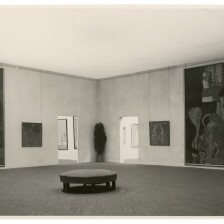

Julius Scherb: Insight into the 1943 memorial exhibition, January 1943 - February 1943, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien

Julius Scherb: Insight into the 1943 memorial exhibition, January 1943 - February 1943, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna -

Julius Scherb: Insight into the 1943 memorial exhibition, January 1943 - February 1943, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien

Julius Scherb: Insight into the 1943 memorial exhibition, January 1943 - February 1943, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna -

Julius Scherb: Insight into the 1943 memorial exhibition, January 1943 - February 1943, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien: Insight into the 1943 memorial exhibition

Julius Scherb: Insight into the 1943 memorial exhibition, January 1943 - February 1943, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien: Insight into the 1943 memorial exhibition

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna -

Julius Scherb: Insight into the 1943 memorial exhibition, January 1943 - February 1943, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien

Julius Scherb: Insight into the 1943 memorial exhibition, January 1943 - February 1943, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna -

Julius Scherb: Insight into the 1943 memorial exhibition, January 1943 - February 1943, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien

Julius Scherb: Insight into the 1943 memorial exhibition, January 1943 - February 1943, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna -

Julius Scherb: View of the 1943 Commemorative Exhibition, January 1943 - February 1943, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien: Insight into the 1943 memorial exhibition

Julius Scherb: View of the 1943 Commemorative Exhibition, January 1943 - February 1943, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien: Insight into the 1943 memorial exhibition

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna -

Julius Scherb: Insight into the 1943 memorial exhibition, January 1943 - February 1943, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien

Julius Scherb: Insight into the 1943 memorial exhibition, January 1943 - February 1943, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Birch Tree on the Attersee (Calm Water), 1901, Verbleib unbekannt

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Photo Series

The exhibition was documented by the photographer Julius Scherb. Today, his visual inventory is of particular importance for research, as several works by Klimt were lost afterwards or destroyed during the war. The series of photographs, which is now kept in the archives of the Vienna Künstlerhaus, comprises altogether seven views of the exhibition rooms. The photographs illustrate the first hanging of Klimt’s works at the Secession, which can be confirmed by comparing them to the two editions of the catalog. In this context, two photographs are particularly worth mentioning. They show two oil paintings by Gustav Klimt that have not been included in the catalogues raisonnés published to date: an unknown small-sized female portrait and the painting Birch Tree on the Attersee (Calm Water) (1901, unknown whereabouts). The latter painting had already been on view in 1902, at the “XIII. Ausstellung der Vereinigung Bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession” [“13th Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists Secession”], and in 1928, at the “Klimt-Gedächtnis-Ausstellung” [“Exhibition in Commemoration of Klimt”]. In 1928, the last known owner of that painting had been Klimt’s niece, Helene Donner.

Literature and sources

- Sophie Lillie: Die Gustav Klimt -Ausstellung von 1943, in: Peter Bogner, Richard Kurdiovsky, Johannes Stoll (Hg.): Das Wiener Künstlerhaus. Kunst und Institution, Vienna 2015, S. 334-341.

- Marion Krammer, Niko Wahl: Klimt Lost, Vienna 2018.

- Ursula Storch (Hg.): Klimt. Die Sammlung des Wien Museums, Ausst.-Kat., Vienna Museum (Vienna), 16.05.2012–07.10.2012, Vienna 2012, S. 38-45.

- Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 08.02.1943, S. 2-3.

- Znaimer Tagblatt, 08.02.1943, S. 3.

- Salzburger Zeitung, 14.02.1943, S. 5.

- Reichsstatthalter in Wien (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Ausstellung 7. Februar bis 7. März 1943. Ausstellungshaus Friedrichstrasse ehemalige Secession, Ausst.-Kat., Friedrichstrasse Exhibition Center (Vienna), 07.02.1943–12.03.1943, 1. Auflage, Vienna 1943.

- Reichsstatthalter in Wien (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Ausstellung 7. Februar bis 7. März 1943. Ausstellungshaus Friedrichstrasse ehemalige Secession, Ausst.-Kat., Friedrichstrasse Exhibition Center (Vienna), 07.02.1943–12.03.1943, 2. Auflage, Vienna 1943.

- Laura Morowitz: "Heil the Hero Klimt!". Nazi Aesthetics in Vienna and the 1943 Gustav Klimt Retrospective, in: Oxford Art Journal, 39. Jg., Nummer 1 (2016), S. 107-129.

Klimt Collectors – Persecuted by the National Socialists

Martin Gerlach: Insight into the apartment of Serena and August Lederer, 1920s - 1930s, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

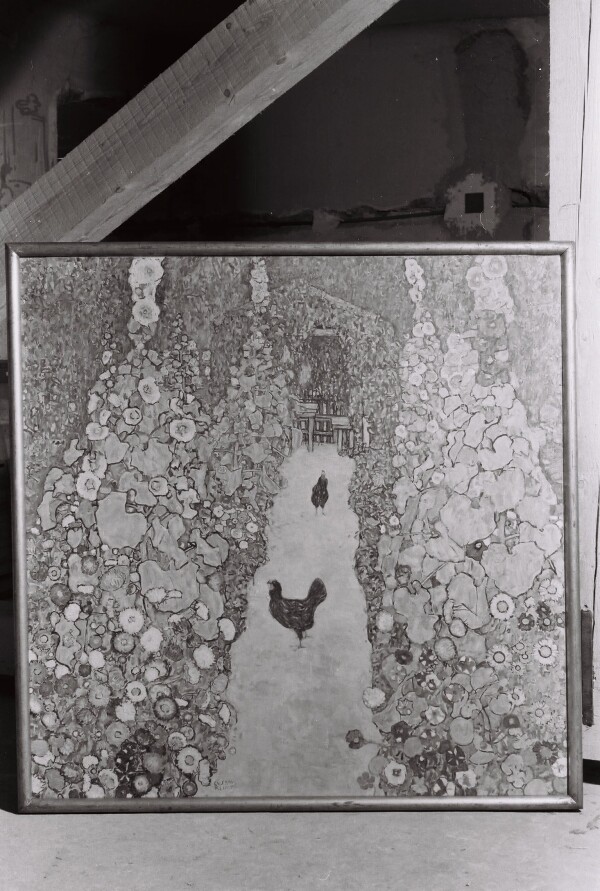

Garden path with chickens, circa 1939, Federal Monuments Authority Austrian

© BDA, Vienna - Federal Monuments Office

It is not least due to restitution procedures that those art collectors persecuted by the National Socialists are much more distinctly perceived by the public today than other collectors. However, it is true that among Klimt’s clientele were indeed many collectors of Jewish origin.

Regardless of the importance one attached to religion, persons of Jewish origin in Vienna around 1900 were to a certain extent always exposed to anti-Semitic hostility. From 1938 on, this culminated in proprietary and personal persecution, including deportation and murder. In addition to money and a personal network, it was above all luck that was needed to be able to leave Austria after the “Anschluss” so as to continue living in safety in another country. Those who managed to do so mostly stayed on in the countries outside continental Europe, which had originally been intended as temporary exile. Only few returned to Austria permanently after 1945.

Gretl Gallia, the daughter of Hermine Gallia, was able to emigrate to Australia with her family. They managed to take their entire collection, including Portrait of Hermine Gallia (1903/04, National Gallery, London), to their new home. In 1976 it went on sale in London. The stops of the painting were made known by Hermina Gallia’s great-grandson, Tim Bonyhady, who described the history of the Gallia family in his book Good Living Street in 2011.

Gertrude Felsövanyi, who as a young woman had posed for Gustav Klimt in 1902 for Portrait of Gertrud Loew (1902, The Lewis Collection), was forced to leave Austria in 1939. She arrived in the USA with her son via several detours and lived in California until her death. She had had to leave her portrait behind, along with six drawings by Klimt. Felsövanyi was never to visit Austria again.

The Lederer family’s extensive art collection was seized in 1938. When the Reich’s governor of Vienna organized a major Klimt exhibition in 1943, he drew on the art collection that had been seized by the authorities and exhibited the masterpieces from the Lederer Collection without the owner’s consent. By this time, Serena Lederer had already fled to Budapest, where she died that same year. Her daughter, Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt, died in Vienna in 1944, and her son managed to emigrate to Switzerland, where he lived until his death. After the end of the war, he received back the Klimt drawings that had been stored in Altaussee. Gustav Klimt’s oil paintings, however, had been destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in Lower Austria as a consequence of the war.

As to the Zuckerkandl family, only Berta Zuckerkandl and her son Fritz were able to escape abroad. Her grandson Emile had already lived in France earlier. Mirijam Amalie Zuckerkandl and her daughter, Nora Stiasny, were murdered at the Belzec extermination camp in October 1942. Nora’s husband, Paul Stiasny, and their son Otto were deported to Auschwitz and murdered.

Further contents

-

Klimt's Artworks 1946 – today (Klimt Today)Klimt = Restitution?

-

Klimt's Artworks 1919 – 1945 (Posthumous Fame and Legend)Show at Ausstellungshaus Friedrichstraße

-

Network Vienna 1900 BenefactorsThe Gallias

-

Network Vienna 1900 BenefactorsThe Zuckerkandl Family

-

Network Vienna 1900 BenefactorsThe Lederer Family

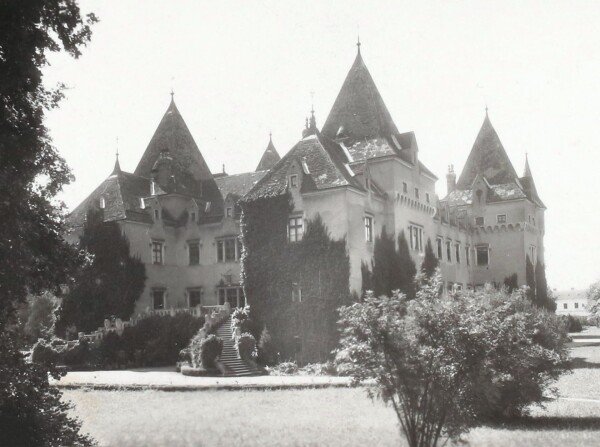

Immendorf Castle

Immendorf Castle

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

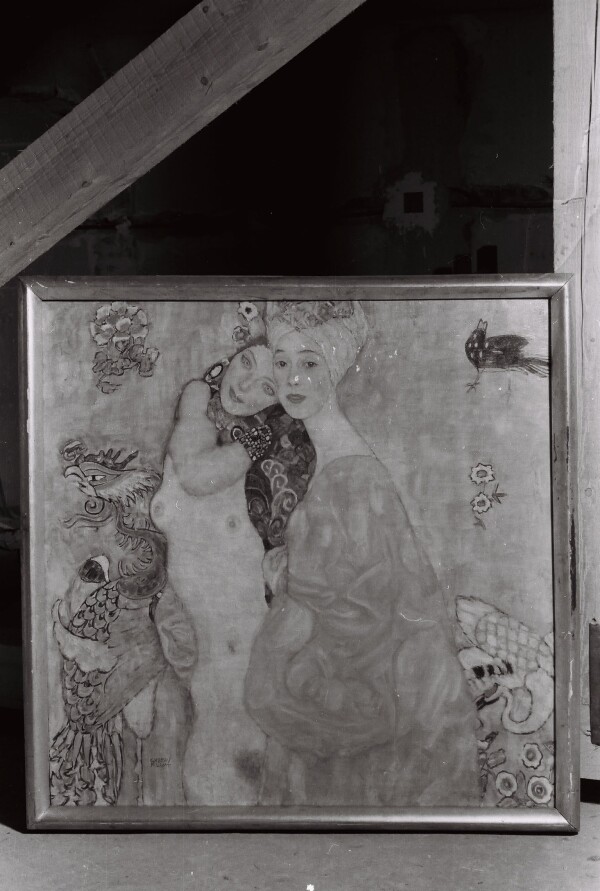

Girlfriends II, circa 1939, Federal Monuments Authority Austrian

© BDA, Vienna - Federal Monuments Office

In May 1945, Austria suffered one of the most serious losses in cultural assets. In the wake of World War II, at least ten paintings and two compositional designs by Gustav Klimt were destroyed by fire, including such masterpieces as the three Faculty Paintings. In addition, further art objects fell victim to the flames.

The Events of 8 May 1945

Starting in 1943, exposed cultural assets were rescued from potential air raids during World War II. Apart from such destinations as Weinern Castle and the Altaussee salt mines, they were also brought to Immendorf Castle in Lower Austria, north of Hollabrunn. The estate, which belonged to the Freudenthal family, was used to store art collections that had been seized by the Nazis, including the Lederer Collection. Moreover, art objects from the holdings of the Museum of Applied Arts (MAK) and the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere were conserved in this place.

At Immendorf, SS units pulling out followed Hitler’s so-called “Nero Decree” of 19 March 1945, regardless of the unconditional surrender. An insane work of destruction began, vandalizing not only strategically crucial targets like roads and bridges, but also monuments and works of art.

Two reports about this catastrophic incident are known, during which the castle burned for several days, leading to the destruction of the paintings stored there: In a letter of 7 August 1945, Baroness Adelheid von Freudenthal pointed out the final eradication of the cultural assets stored at the castle by a German SS unit. The owners of the castle had left the place before 20 April 1945. The subsequent federal police report of the District of Hollabrunn, dating from 20 May 1946, mentions the German SS unit known under the name of “Feldherrenhalle,” which is said to have celebrated orgies at the castle on 7 May 1945. Following the troops’ withdrawal and shortly after the arrival of the Red Army, a fire deliberately set by the Nazis and raging over an extensive period of time devastated the entire building. It started at the tower, causing several explosions due to ammunition stored there. Eyewitness reports and documentations of the events are not known. Speculations that the place had been looted prior to the fire had been voiced time and again. However, it has not been possible to substantiate to date whether objects – and if yes, which ones – were possibly removed then.

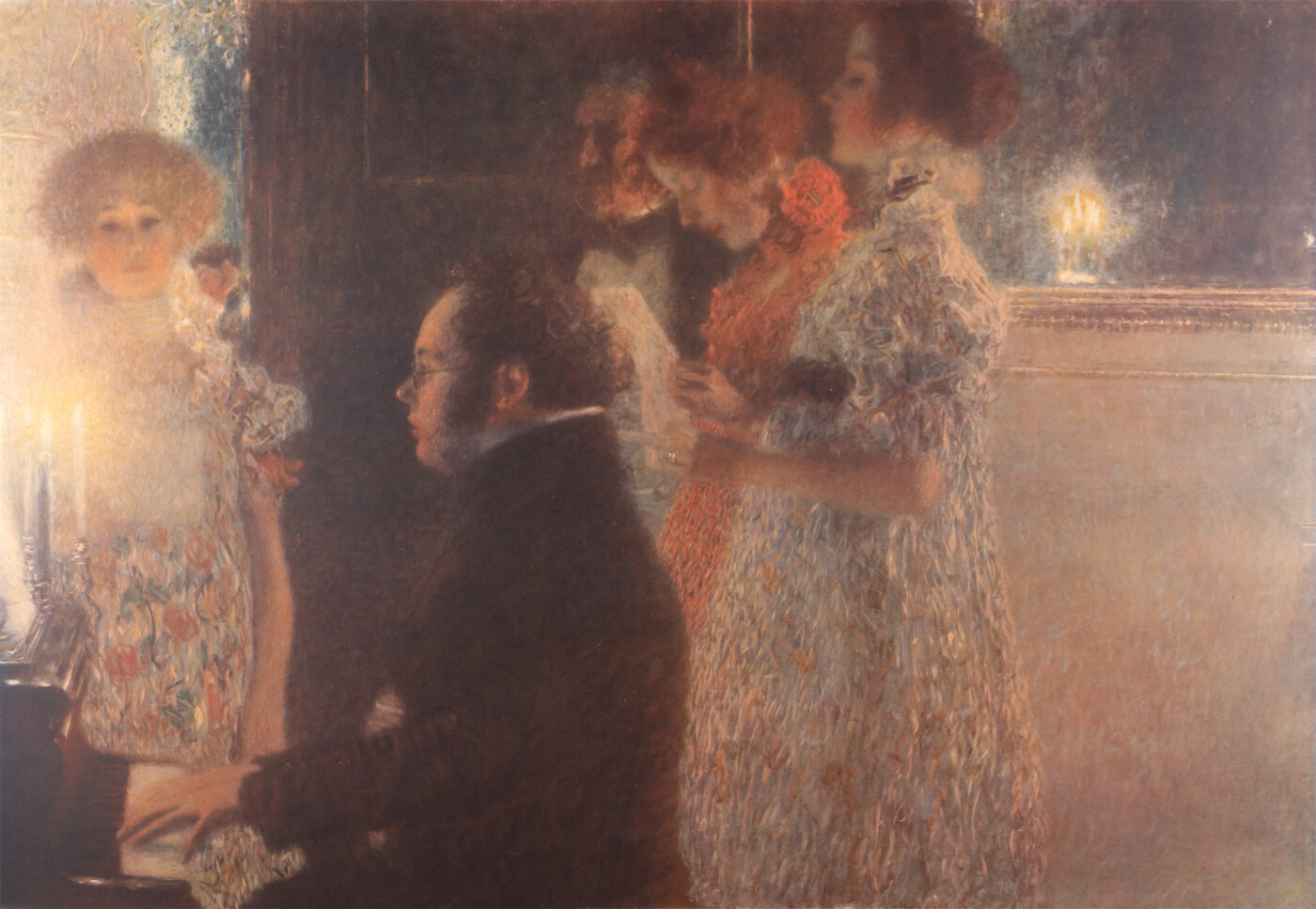

The Rescue

It was presumably on 3 April 1943 that the following paintings by Klimt arrived at Immendorf: Country Garden with Calvary (1912), Friends II (1916/17), Portrait of Wally (1916), Garden Path with Chickens (1916), The Golden Apple Tree (1903), Jurisprudence (1903–1907), Philosophy (1900–1907), Leda (1917), Music (1897/98), and Schubert at the Piano (1899). Moreover, the compositional designs for Philosophy (1898) and Jurisprudence (1897/98) had also been brought to Immendorf. However, the latter two, unlike the paintings mentioned, did not appear on the rescue list of 3 March 1945. All of these works are now considered having been destroyed by the fire raging at Immendorf Castle. Moreover, works by Egon Schiele, such as his painting Mödling I (Gray City) (1916) and a watercolored Self-Portrait (1910), as well as sketches for the ceiling of the Burgtheater by Ernst Klimt, Hanswurst (1886/87) and Molière Theater (1886/87), were destroyed. All of these objects originally came from the Lederer Collection, the most comprehensive collection of works by Klimt in private ownership. In 1919, the Faculty Painting of Medicine (1900–1907) had been acquired by the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere via Ditha Moser with the aid of Serena Lederer. The Nazis also brought it to the rescue place at Immendorf, where it burned together with the two other Faculty Paintings.

Klimt Paintings from the Rescue List

-

Gustav Klimt: Country Garden with Calvary, 1912, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

Gustav Klimt: Country Garden with Calvary, 1912, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

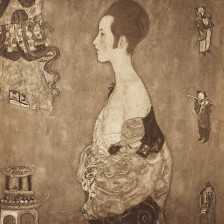

Gustav Klimt: Friends II, 1916/17, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt, in: Max Eisler (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Eine Nachlese, Vienna 1931.

Gustav Klimt: Friends II, 1916/17, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt, in: Max Eisler (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Eine Nachlese, Vienna 1931.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Wally, 1916, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Wally, 1916, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

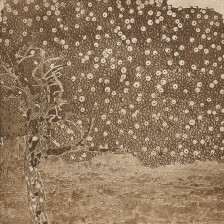

Gustav Klimt: Garden Path with Chickens, 1916, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

Gustav Klimt: Garden Path with Chickens, 1916, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: The Golden Apple Tree, 1903, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

Gustav Klimt: The Golden Apple Tree, 1903, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

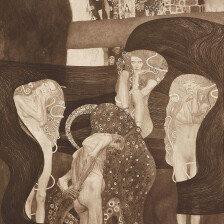

Gustav Klimt: Jurisprudence, 1903-1907, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt, in: Kunstverlag Hugo Heller (Hg.): Das Werk von Gustav Klimt, Vienna - Leipzig 1918.

Gustav Klimt: Jurisprudence, 1903-1907, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt, in: Kunstverlag Hugo Heller (Hg.): Das Werk von Gustav Klimt, Vienna - Leipzig 1918.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

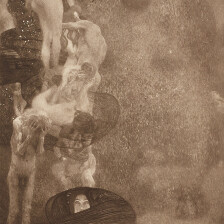

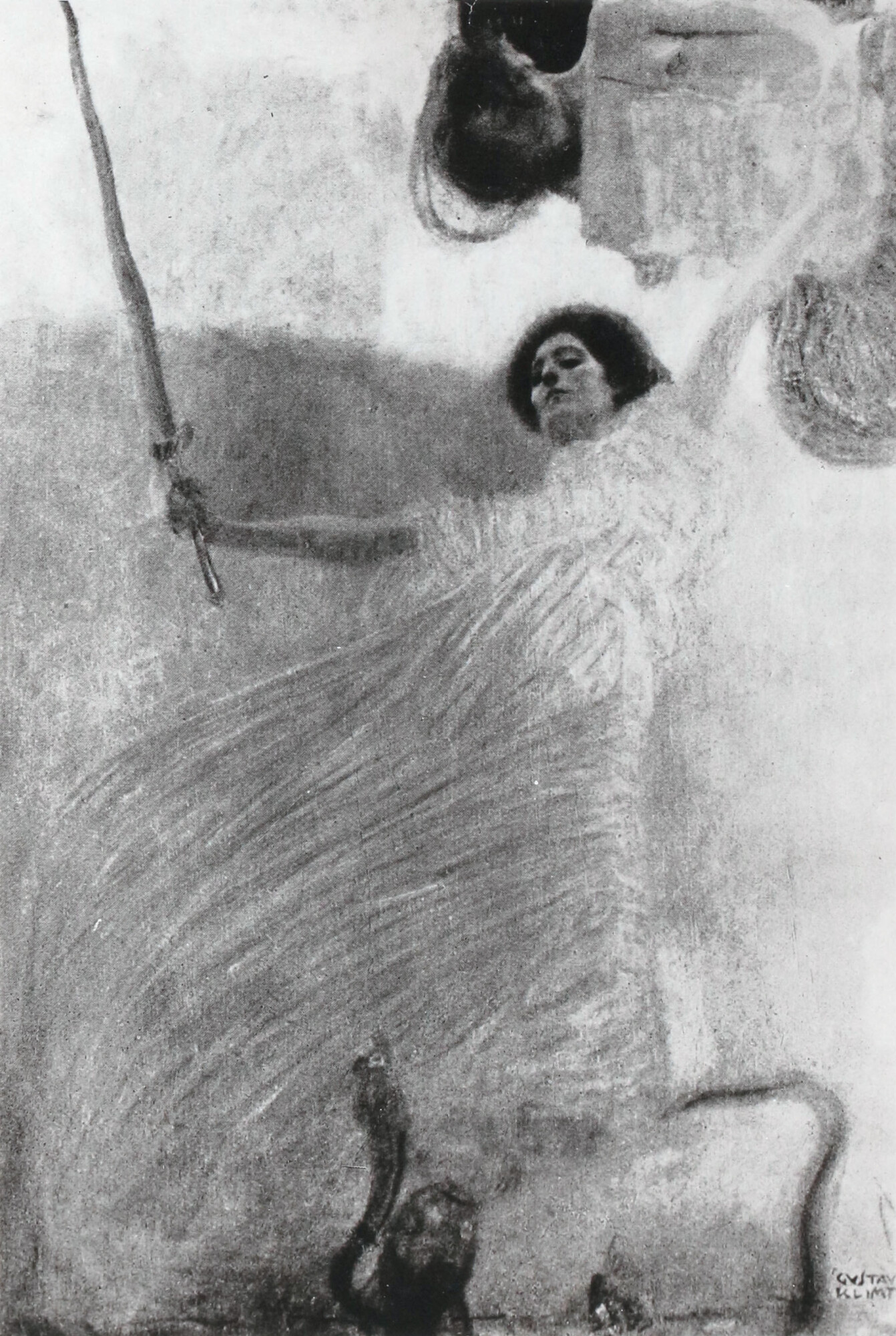

Gustav Klimt: Philosophy, 1900-1907, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt, in: Kunstverlag Hugo Heller (Hg.): Das Werk von Gustav Klimt, Vienna - Leipzig 1918.

Gustav Klimt: Philosophy, 1900-1907, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt, in: Kunstverlag Hugo Heller (Hg.): Das Werk von Gustav Klimt, Vienna - Leipzig 1918.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

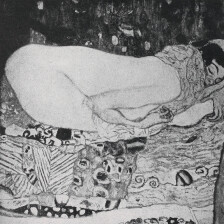

Gustav Klimt: Leda, 1917, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

Gustav Klimt: Leda, 1917, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Music, 1897/98, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

Gustav Klimt: Music, 1897/98, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Schubert at the Piano, 1899, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

Gustav Klimt: Schubert at the Piano, 1899, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Philosophy (Study), 1898, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

Gustav Klimt: Philosophy (Study), 1898, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

© Gallery Welz Salzburg -

Gustav Klimt: Jurisprudence (Study), 1897/98, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

Gustav Klimt: Jurisprudence (Study), 1897/98, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

© Gallery Welz Salzburg

Martin Gerlach: Insight into the apartment of Serena and August Lederer, 1920s - 1930s, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Further works by Klimt from the Lederer Collection, the rescue and storage of which at Immendorf Castle could not be verified and which have been considered lost since 1945, include: From the Realm of Death (Stream of the Dead) (1903), Malcesine on Lake Garda (1913), Portrait of Charlotte Pulitzer (1917), and Gastein (1917).

The Lederer Family Collection

August and Serena Lederer and their children Elisabeth (married name Bachofen-Echt), Erich, and Fritz were already the most important collectors of Klimt during the artist’s lifetime, and they were also on friendly terms with him. After August Lederer’s death in 1936, the collection continued to be owned by Serena and her children and remained in their apartment at Bartensteingasse 8 in Vienna’s First District (Inner City). After Austria’s “Anschluss” to Nazi Germany in March 1938, the apartment was looted by the Gestapo, during which a large number of Klimt drawings were confiscated. In March 1939, the collection was finally removed by the Nazis, and the apartment was sealed.

Last Public Presentation

In January 1943, Klimt’s works were brought from Bartensteingasse to the Secession, where they were presented from 7 February to 14 March. Baldur von Schirach, Reich Governor of Vienna, held the so-called “Gedächtnisausstellung” (“Commemorative Exhibition”) on the artist’s 80th birthday in 1942. With its 96 items, the catalog documented fundamental masterpieces, including the Beethoven Frieze, the Faculty Paintings, and the designs for the Stoclet Frieze. All in all, as many as 50 paintings and 45 drawings were on display. The early ending of the show, probably due to imminent air raids, and the transfer to their alleged rescue place at Immendorf Castle eventually meant an immense loss of cultural heritage for Austria.

Literature and sources

- Andreas Lehne: Die Katastrophe von Immendorf. Nach dem Archivmaterial vom Bundesdenkmalamt, in: Stephan Koja (Hg.): Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst. Sonderband Gustav Klimt, Vienna 2007, S. 54-63.

- Peter Weinhäupl: Under Construction: The Faculty Paintings. Klimts´s Pugnacious Modernism, its Unwanted Recognition and Downfall, in: Deborah Pustišek Antić (Hg.): The Unknown Klimt. Love, Death, Ecstasy, Ausst.-Kat., Muzej Grada Rijeke (Rijeka), 20.04.2021–20.10.2021, Rijeka 2021, S. 195-201.

- Pia Schölnberger, Sabine Loitfellner (Hg.): Bergung von Kulturgut im Nationalsozialismus, Mythen – Hintergründe – Auswirkungen, Vienna - Cologne - Weimar 2016.

- Leonhard Weidinger: Schloss Immendorf. www.lexikon-provenienzforschung.org/immendorf-schloss (08/29/2022).