Klimt's work focuses on all aspects of the Art Nouveau master's oeuvre. Visualized through a timeline, Klimt's creative periods are rolled up here, starting with his training, his collaboration with Franz Matsch and his brother Ernst in the "Künstler-Compagnie", the affair surrounding the faculty paintings and his post-fame and the myth that still surrounds this exceptional artist today.

Discovery and Development of a Drawing Talent

→

Gustav Klimt: Allegory of Music, 1880, Internationales Dialogzentrum (KAICIID)

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Becoming a Drawing Instructor

One of Gustav Klimt’s teachers recommended to Klimt’s father that the talented pupil study at the Imperial-Royal School of Arts and Crafts to train as a drawing instructor. The entrance examination took place in October 1876. Gustav passed it together with his brother Ernst.

To the chapter

→

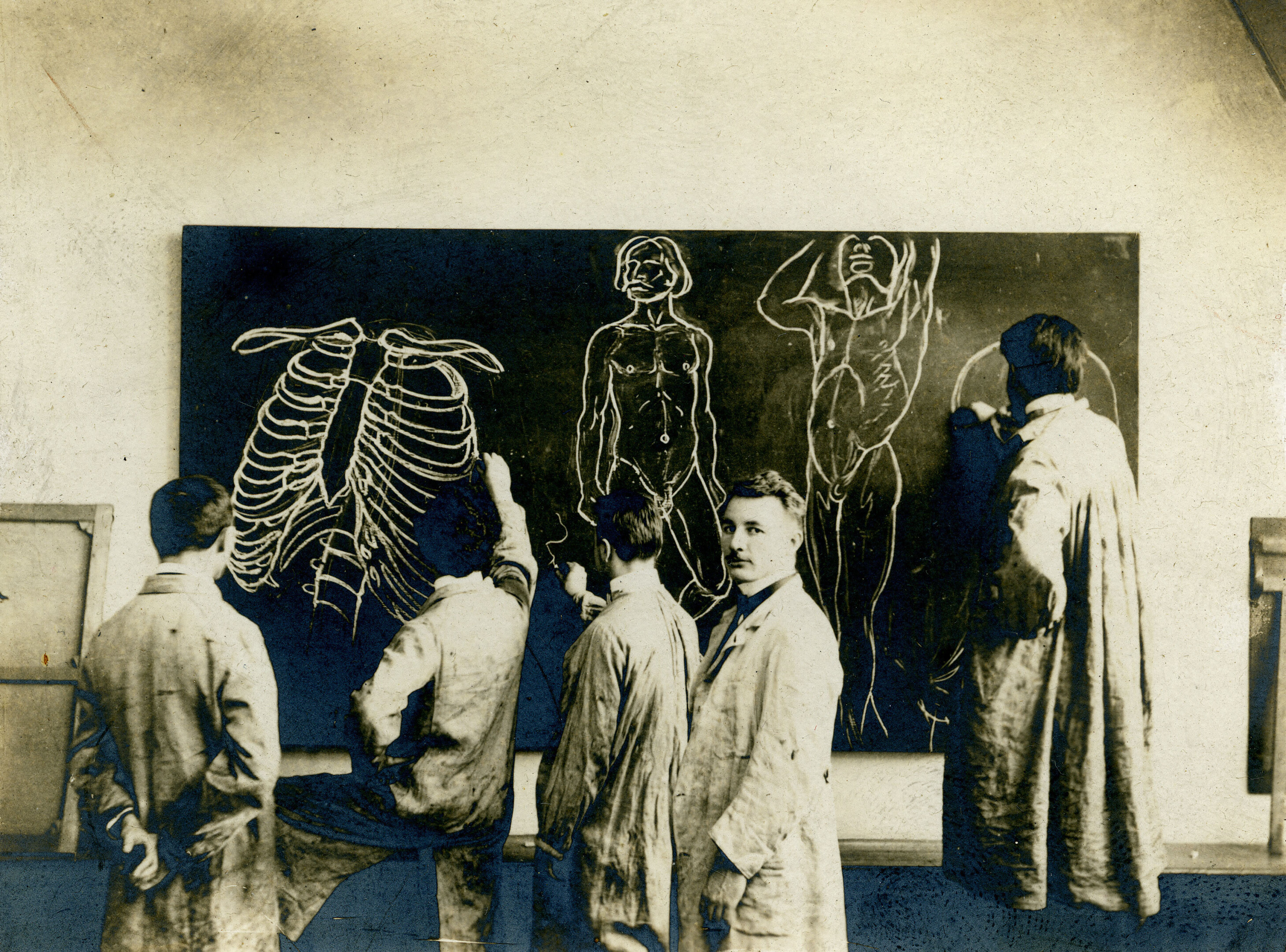

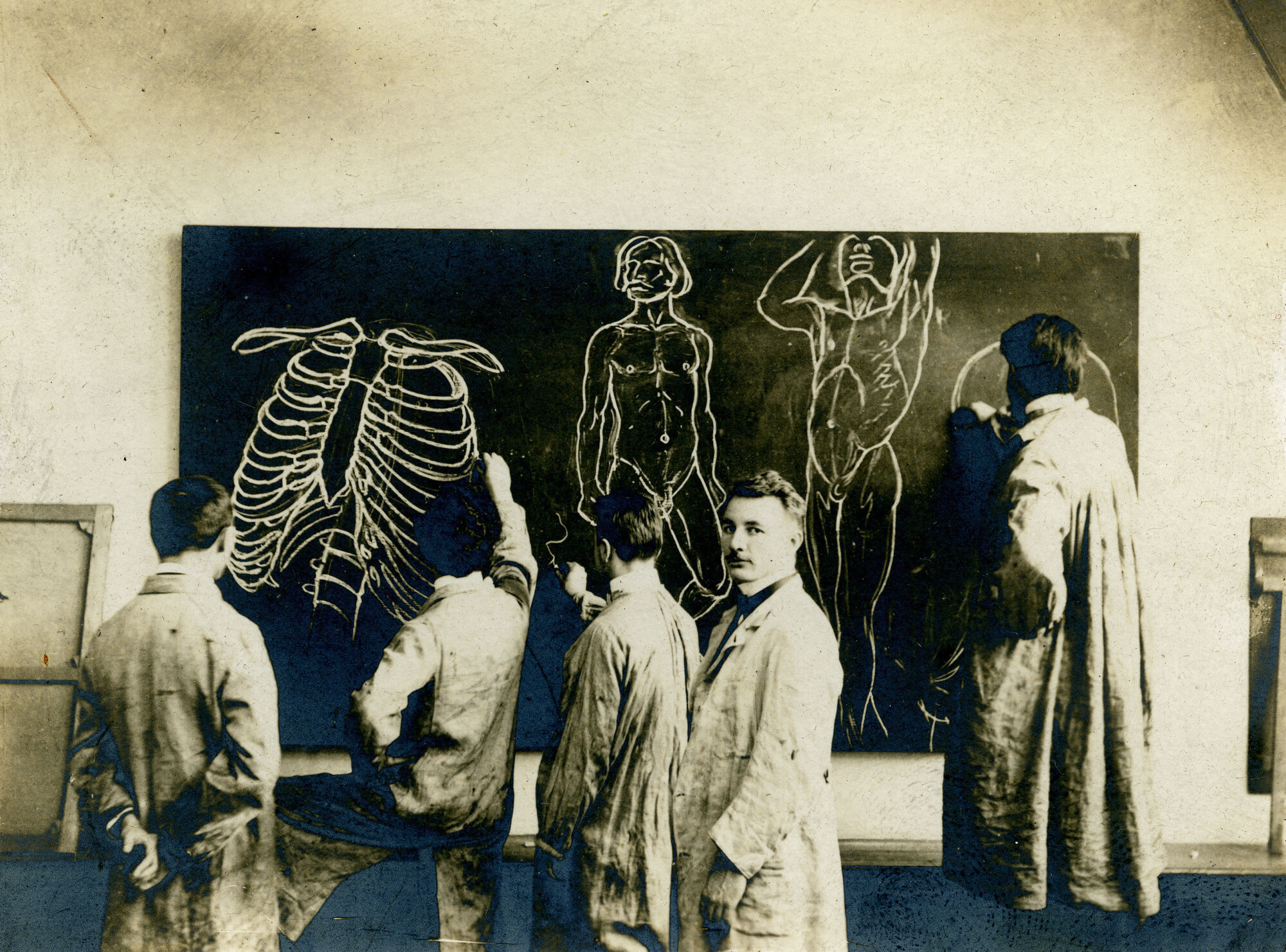

Anatomy lecture at the Imperial and Royal School of Arts and Crafts, around 1900

© University of Applied Arts Vienna, Collection & Archive

Preparatory School at the Imperial-Royal School of Arts and Crafts

Having passed the entrance examination to study as a regular student at the Imperial-Royal School of Arts and Crafts in October 1876, Gustav Klimt attended the school’s preparatory class for two years. There, he created mostly pencil and charcoal drawings after plaster casts, and concentrated on portraits.

To the chapter

→

Imperial and Royal School of Arts and Crafts, around 1880

© Wien Museum

Training as a Decorative Painter

Ferdinand Laufberger trained Gustav Klimt, his brother Ernst and Franz Matsch to become decorative painters. He instructed them in various techniques and enlisted Klimt and his fellow students to assist with his own commissions.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt, Ernst Klimt, Franz Matsch: Allegories of the Fine and Applied Arts, 1879/80, Kunsthistorisches Museum

© KHM-Museumsverband

First Female Portraits

The earliest surviving autonomous oil paintings by Gustav Klimt are study heads and academic nudes datable to the period between 1880 and 1883.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Klara Klimt, circa 1880, ARGE Sammlung Gustav Klimt, Dauerleihgabe im Leopold Museum, Wien

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

Turning to Nature

Forest ground, profuse vegetation, and a pond were at the beginning of Gustav Klimt’s landscape painting. Apart from his commissions for decorative programs within the “Künstler-Compagnie” he studied atmospheric light effects and picturesque views of natural scenery, thus joining the tradition of a romanticized approach to nature.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Forest Floor, 1881/82, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Palais Sturany

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Allegory of Music, 1880, Internationales Dialogzentrum (KAICIID)

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Kursalon Karlsbad

In 1880/81, the new Kursalon was built in the municipal park of Karlsbad to designs by the Viennese architects Fellner & Helmer. The building’s barrel-vaulted main hall, which no longer exists today, was decorated by the “Künstler-Compagnie” with “ceiling paintings.”

To the chapter

→

Kursalon in Karlovy Vary, around 1890

© SLUB / Deutsche Fotothek

Palais Zierer

In 1881/82, Julius Victor Berger afforded his students Franz Matsch and the Klimt brothers the opportunity to participate in one of his own decorative commissions – the decoration of the newly erected Palais Zierer in Vienna. It is believed that the “Künstler-Compagnie” was largely responsible for the independent execution of several ceiling paintings which were based on preliminary sketches by Berger.

To the chapter

→

Julius Victor Berger: Design for a ceiling painting in Palais Zierer, 1881

© Graphic Collection of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna

Stadttheater Brünn

By 1882, the “Künstler-Compagnie” had firmly established itself as a trio of versatile and congenial decorative painters who cooperated with the architectural office Fellner & Helmer. It was likely also at the architects’ behest that the three young artists created sgraffiti for the new municipal theater in Brünn.

To the chapter

→

Brno City Theater, in: Neue Illustrierte Zeitung, 26.11.1882.

© ANNO | Austrian National Library

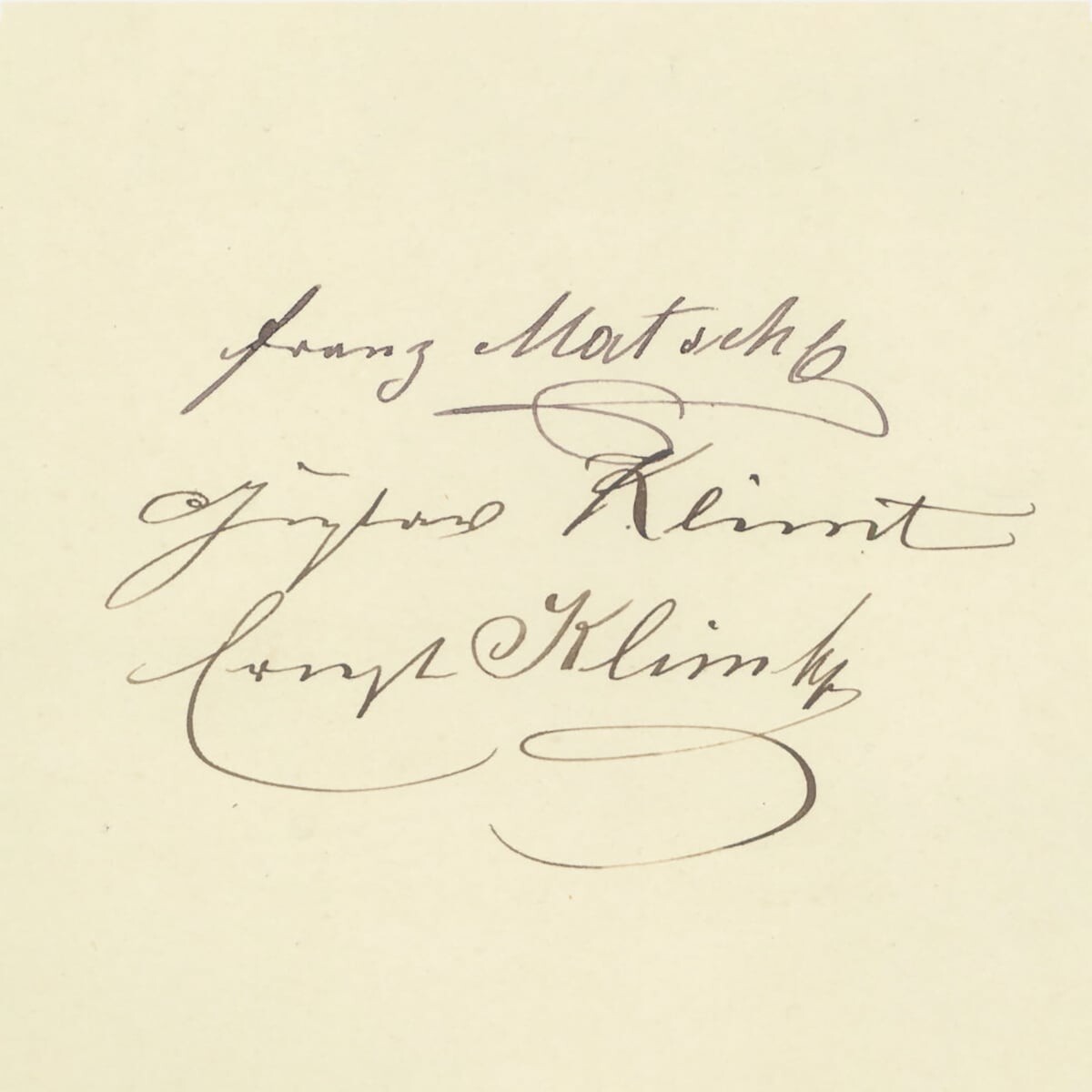

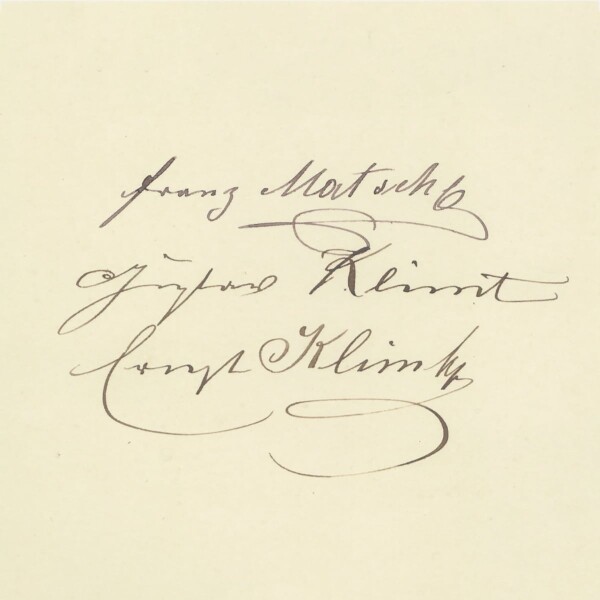

Founding of the “Künstler-Compagnie”

It was already during their studies that the Klimt brothers and Franz Matsch began cooperating closely. The Imperial-Royal School of Arts and Crafts provided the young artists with a studio of their own for their work. This marked the foundation of their studio partnership “Brüder Klimt and Franz Matsch.”

To the chapter

→

Franz Matsch: Letter from Franz Matsch in Vienna to the Magistrate of the City of Liberec, co-signed by Gustav and Ernst Klimt, 10/11/1883, SOkA Liberec, Archiv města Liberec (AML)

© SOkA Liberec, Archiv města Liberec (AML)

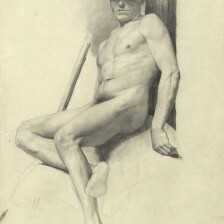

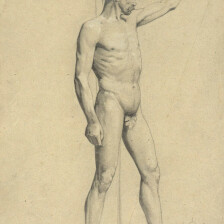

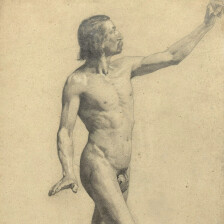

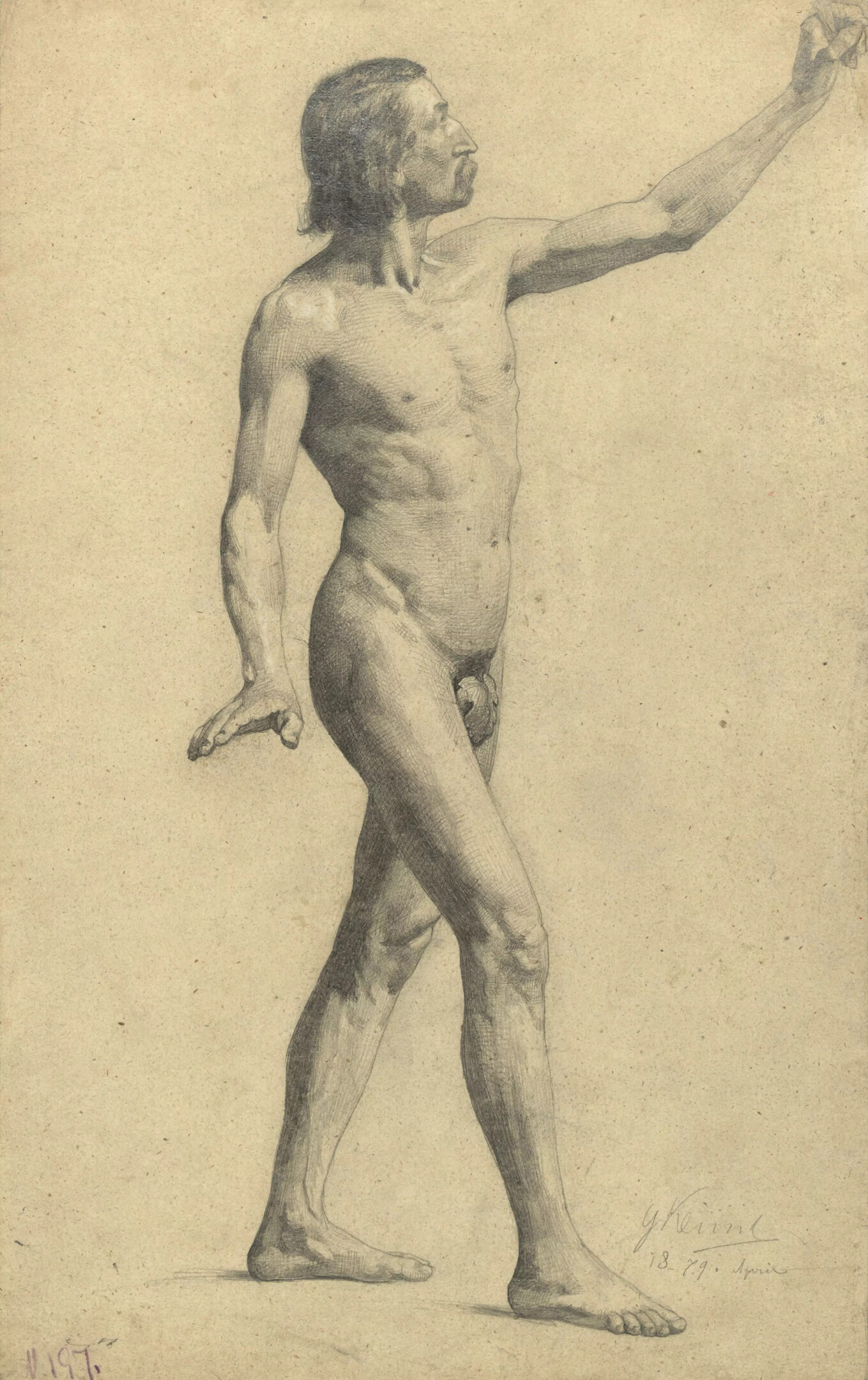

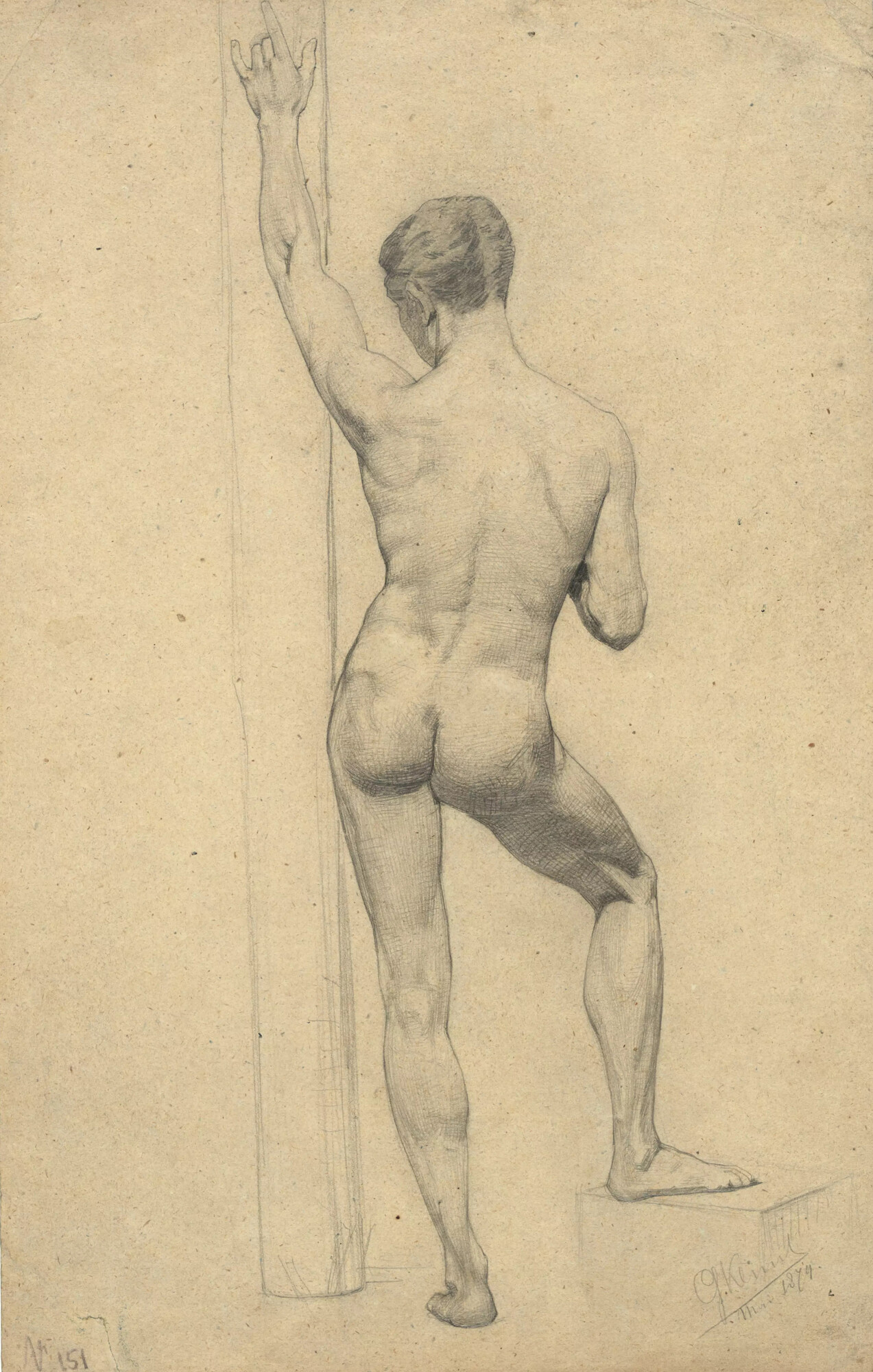

Drawings

Even the drawings from his first years as a student, when Klimt trained by copying plaster statues and sketching portraits, reveal the artist’s outstanding talent. In the Drawing and Painting Class, individual anatomical studies undertaken in life drawing sessions were part of the instructions in drawing.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Male academy act in motion, 1879, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Discovery and Development of a Drawing Talent

→

Gustav Klimt: Allegory of Music, 1880, Internationales Dialogzentrum (KAICIID)

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Becoming a Drawing Instructor

Elementary and secondary school at Lerchenfelder Strasse 61 (first building in the foreground), around 1890

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

One of Gustav Klimt’s teachers recommended to Klimt’s father that the talented pupil study at the Imperial-Royal School of Arts and Crafts to train as a drawing instructor. The entrance examination took place in October 1876. Gustav passed it together with his brother Ernst.

Gustav Klimt attended elementary school for eight years at Lerchenfelder Straße 61 in the 7th District of Vienna. It was at this school that his teachers first recognized and fostered his talent. One of his teachers allegedly convinced Klimt’s father to afford his son an adequate education. Initially, the aim was for Klimt to train as a drawing instructor rather than as an artist. It was likely due to the father’s artisan background as a gold engraver and to the family’s difficult financial situation that Gustav Klimt studied at the Imperial-Royal School of Arts and Crafts (now University of Applied Arts Vienna) rather than at the Imperial-Royal Vienna Academy of Fine Arts. While the School of Arts and Crafts trained students in the field of applied arts (stage painters, chasers and engravers, etc.), graduates from the Academy became freelance painters, sculptors and architects.

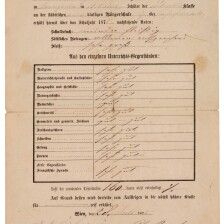

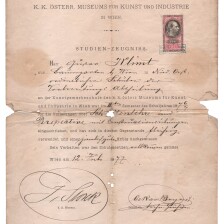

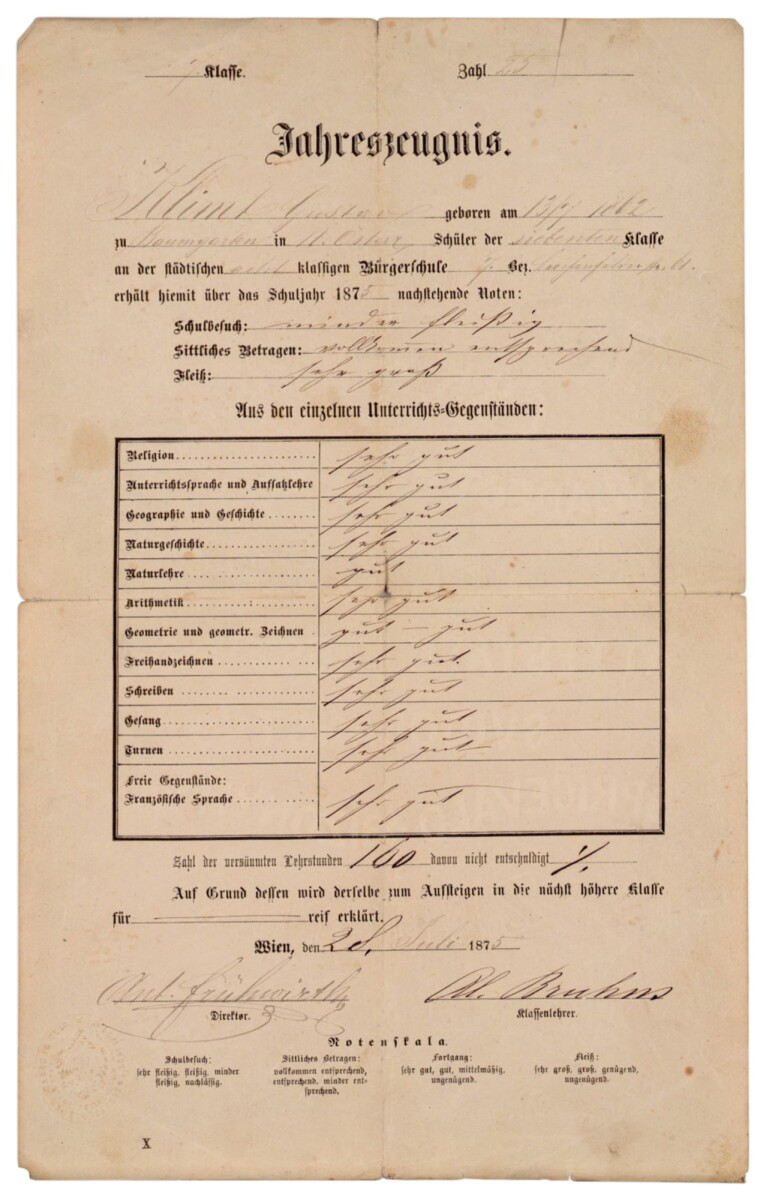

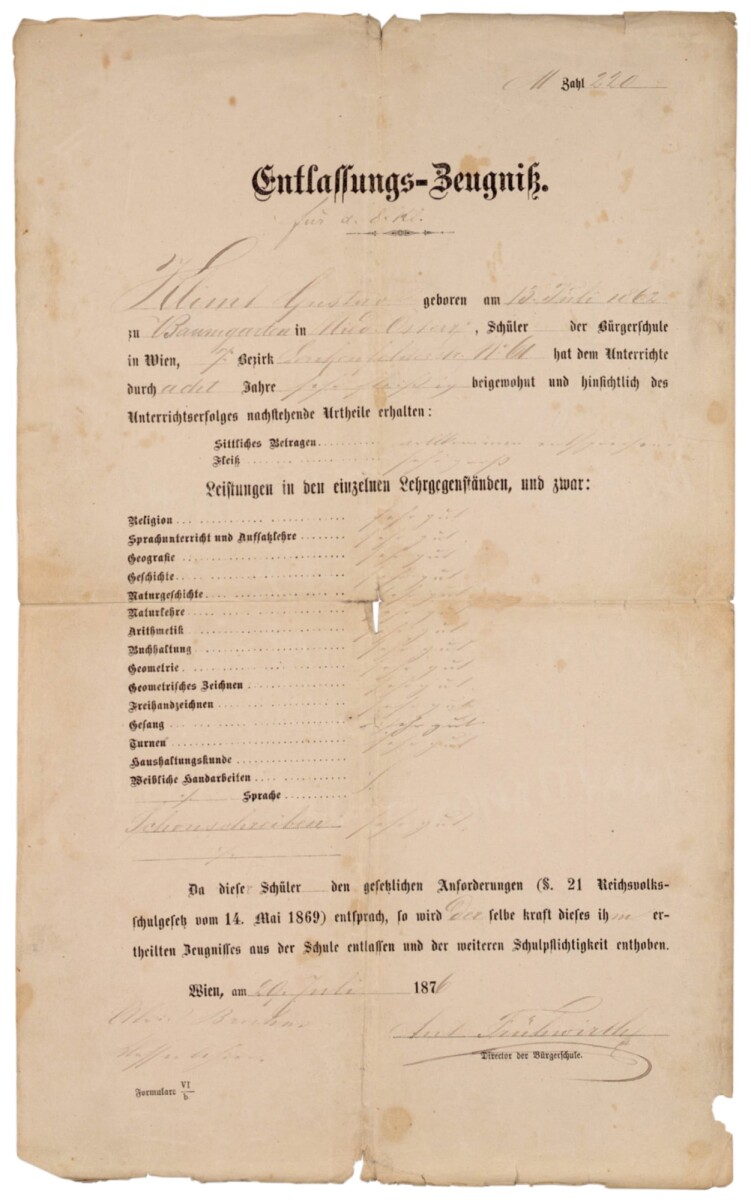

Gustav Klimt’s Certificates from the School Years of 1875 and 1876

-

Annual report by Gustav Klimt for the seventh grade of the Bürgerschule in Vienna, 07/28/1875, The Albertina Museum

Annual report by Gustav Klimt for the seventh grade of the Bürgerschule in Vienna, 07/28/1875, The Albertina Museum

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt's certificate of dismissal from the citizen's school in Vienna, 07/29/1876, The Albertina Museum

Gustav Klimt's certificate of dismissal from the citizen's school in Vienna, 07/29/1876, The Albertina Museum

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

Anatomy lecture at the Imperial and Royal School of Arts and Crafts, around 1900

© University of Applied Arts Vienna, Collection & Archive

Entrance Examination and “Meeting” Franz Matsch

In October 1876, aged 14, Gustav Klimt sat the entrance examination at the Imperial-Royal School of Arts and Crafts with the aim of becoming a drawing instructor. He passed the test together with a further 132 pupils of his year.

Franz Matsch left some 120 pages of handwritten manuscripts – his Autobiographical Sketches – which include his recollections of the entrance examination at the School of Arts and Crafts:

“[…] several plaster heads were exhibited to this end. One classical female head would decide my whole life! Sitting next to me was Gustav KLIMT [!], his brother Ernst joined the school a year later. We became friends immediately and discussed our chances, but we felt rather hopeless. […] The next day, our hearts racing, we got the results; we had been accepted! […] When we enrolled, we had to state our desired profession. Drawing instructors at a secondary school was our aim.”

The records kept by the University of Applied Arts Vienna contradict Franz Matsch’s recollections written in 1930. According to them, Matsch had passed the entrance examination already in October 1875 and attended the preparatory class that semester. In his handwritten CV, Klimt wrote that he did not sit the exam until October 1876. This is confirmed by the records. Thus, it is not possible that the two artists sat next to each other already during the entrance examination. The records further contradict that Ernst only joined the school in 1877. Like his brother, he started studying at the School of Arts and Crafts in the academic year of 1875/76. The three young painters would have met in class, as all three shared the goal of becoming drawing instructors, and thus attended the same lessons.

Literature and sources

- Franz Matsch: Autobiografische Schriften. Privatbesitz, S. 12.

- Herbert Giese: Matsch und die Brüder Klimt. Regesten zum Frühwerk Gustav Klimts, in: Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Galerie, 22/23. Jg., Nummer 66/67 (1978/79), S. 48-68.

- Klassenkataloge 1876–1881, .

- Lebenslauf, eigenhändig verfasst von Gustav Klimt (12/21/1893). Beilage zu Verwaltungsakt Zl. 497-1893, .

- Entlassungszeugnis von Gustav Klimt für die Bürgerschule in Wien (07/29/1876). GKA77.

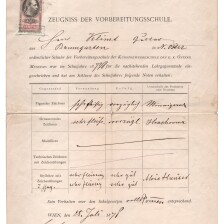

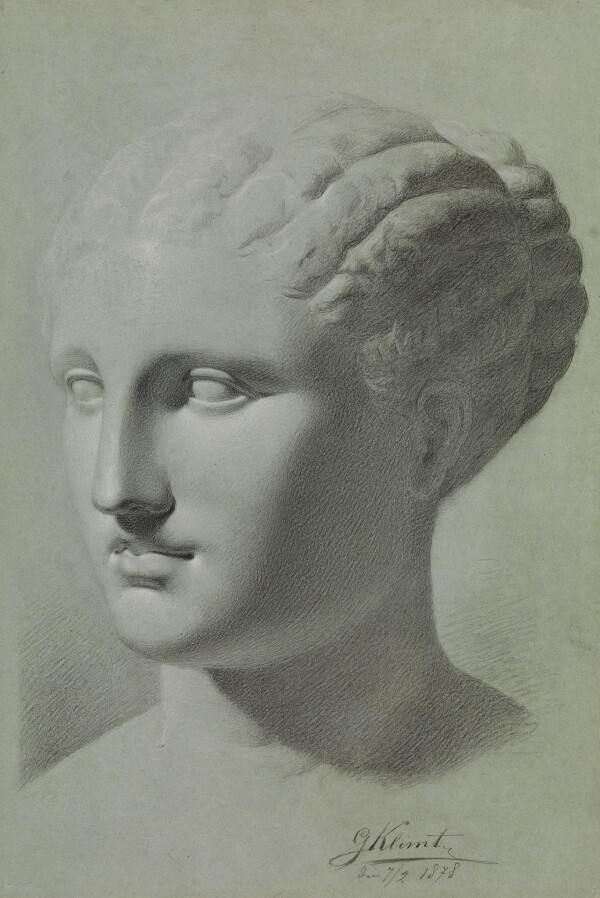

Preparatory School at the Imperial-Royal School of Arts and Crafts

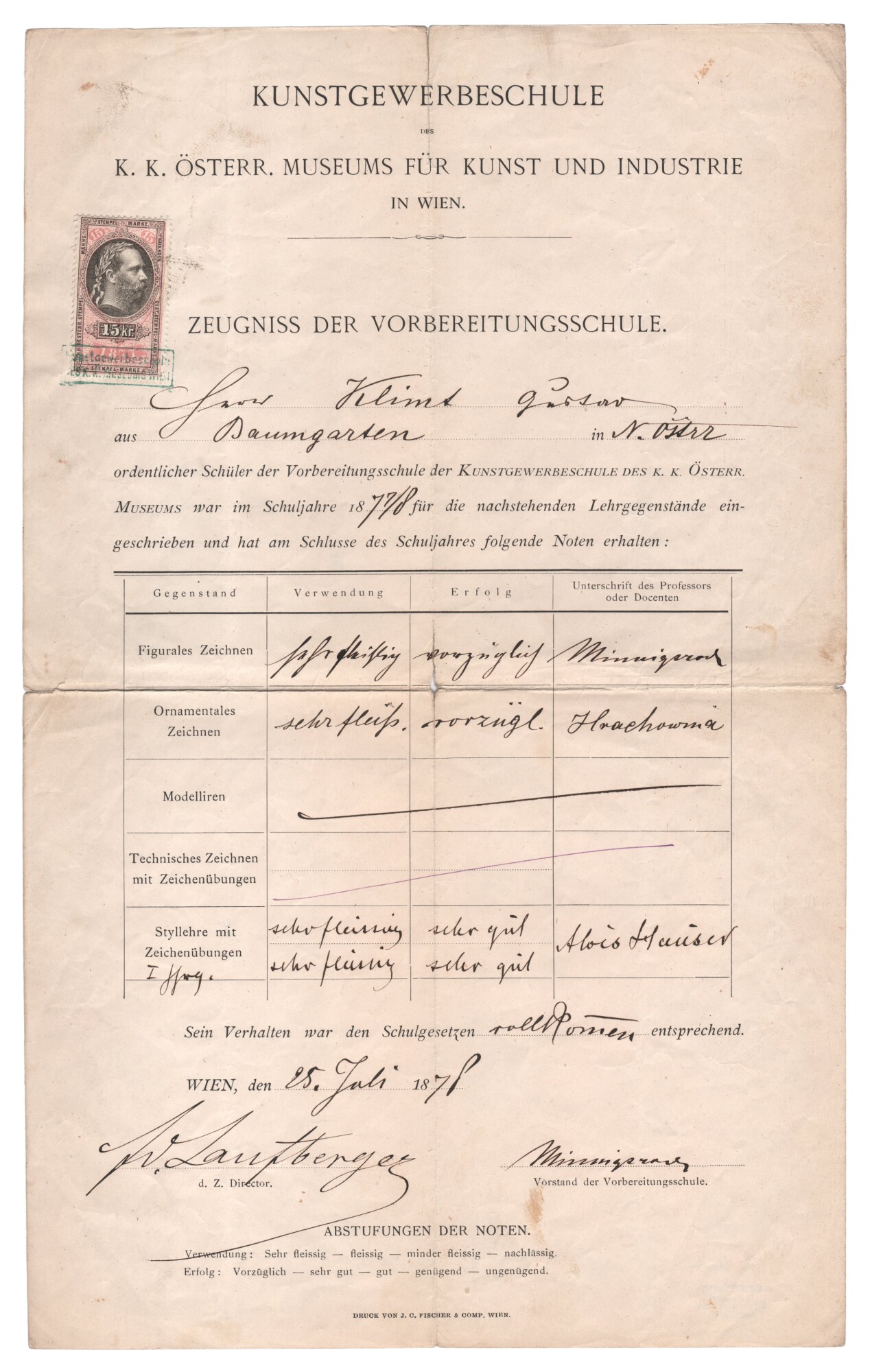

Imperial and Royal School of Arts and Crafts, around 1880

© Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Study based on the plaster model of an acanthus vine, 1877/78, ARGE Sammlung Gustav Klimt, Dauerleihgabe im Leopold Museum, Wien

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

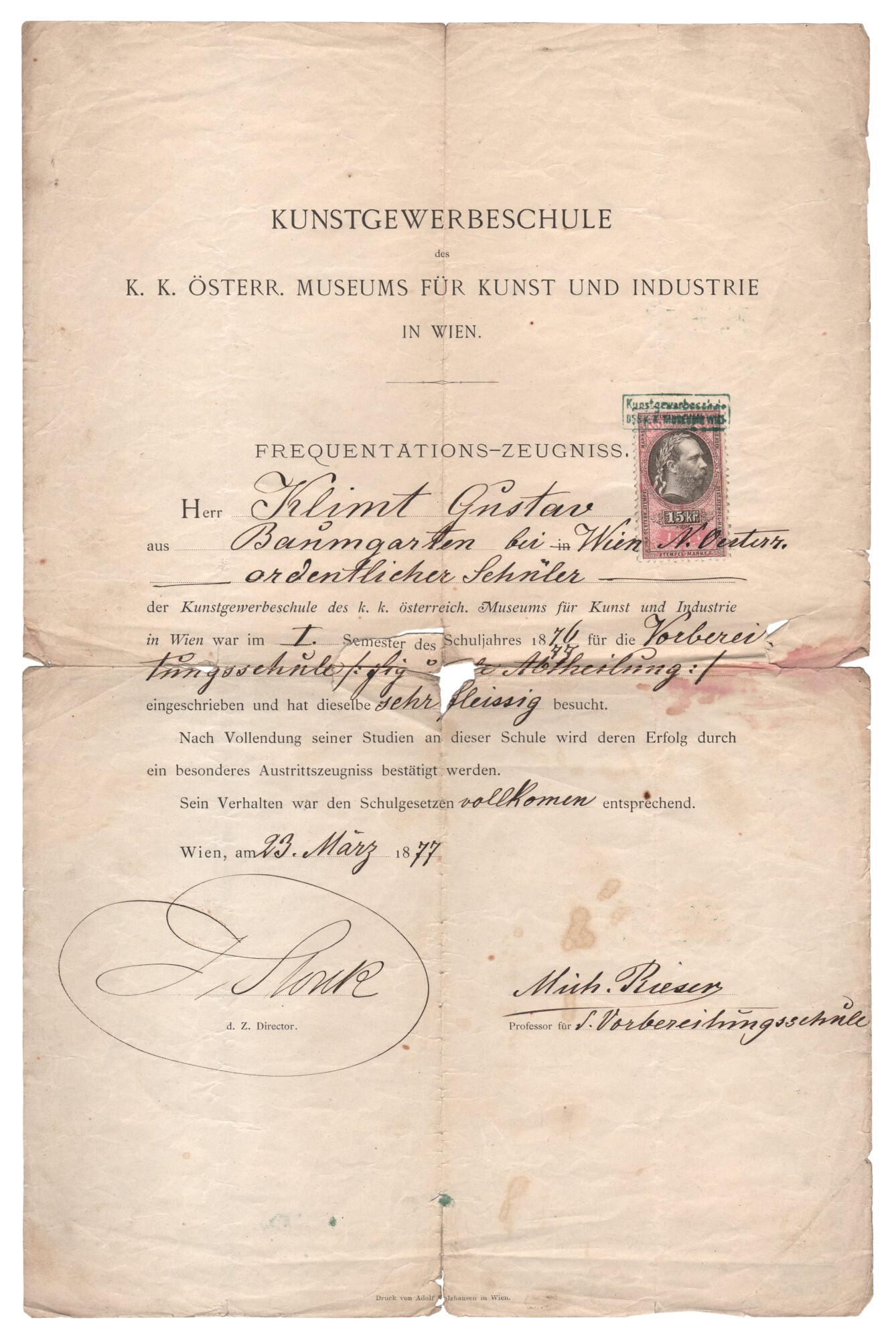

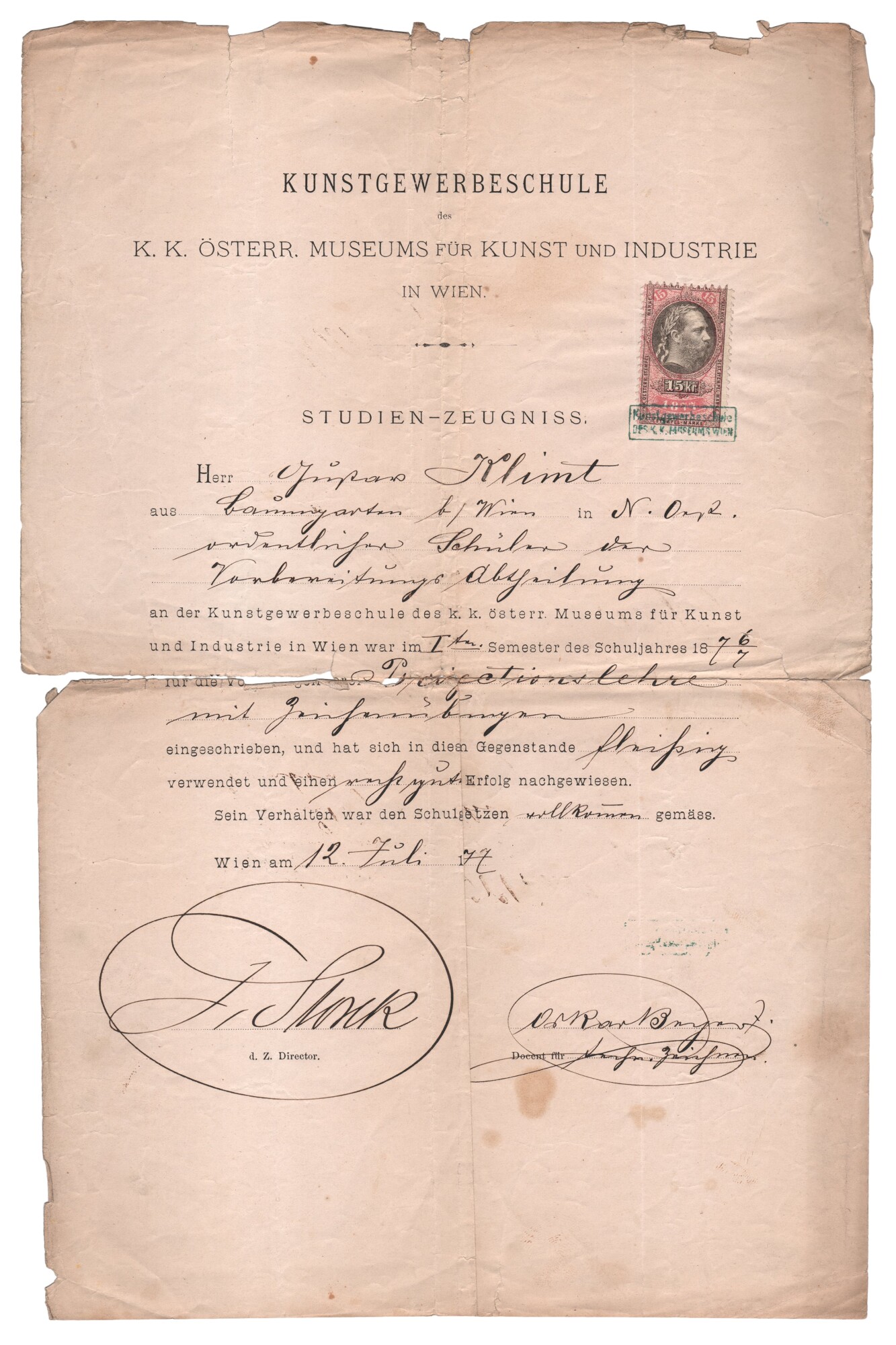

Having passed the entrance examination to study as a regular student at the Imperial-Royal School of Arts and Crafts in October 1876, Gustav Klimt attended the school’s preparatory class for two years. There, he created mostly pencil and charcoal drawings after plaster casts, and concentrated on portraits.

As a prospective teacher, Gustav Klimt attended the preparatory class, known as the “general department,” for two years together with his slightly older colleague Franz Matsch. At the school, which at the time was housed in the building of the Austrian Museum of Art and Industry (now MAK, Vienna) at Stubenring 5, Klimt was instructed in the basics of painting and drawing by copying plaster figures and attending nude drawing classes.

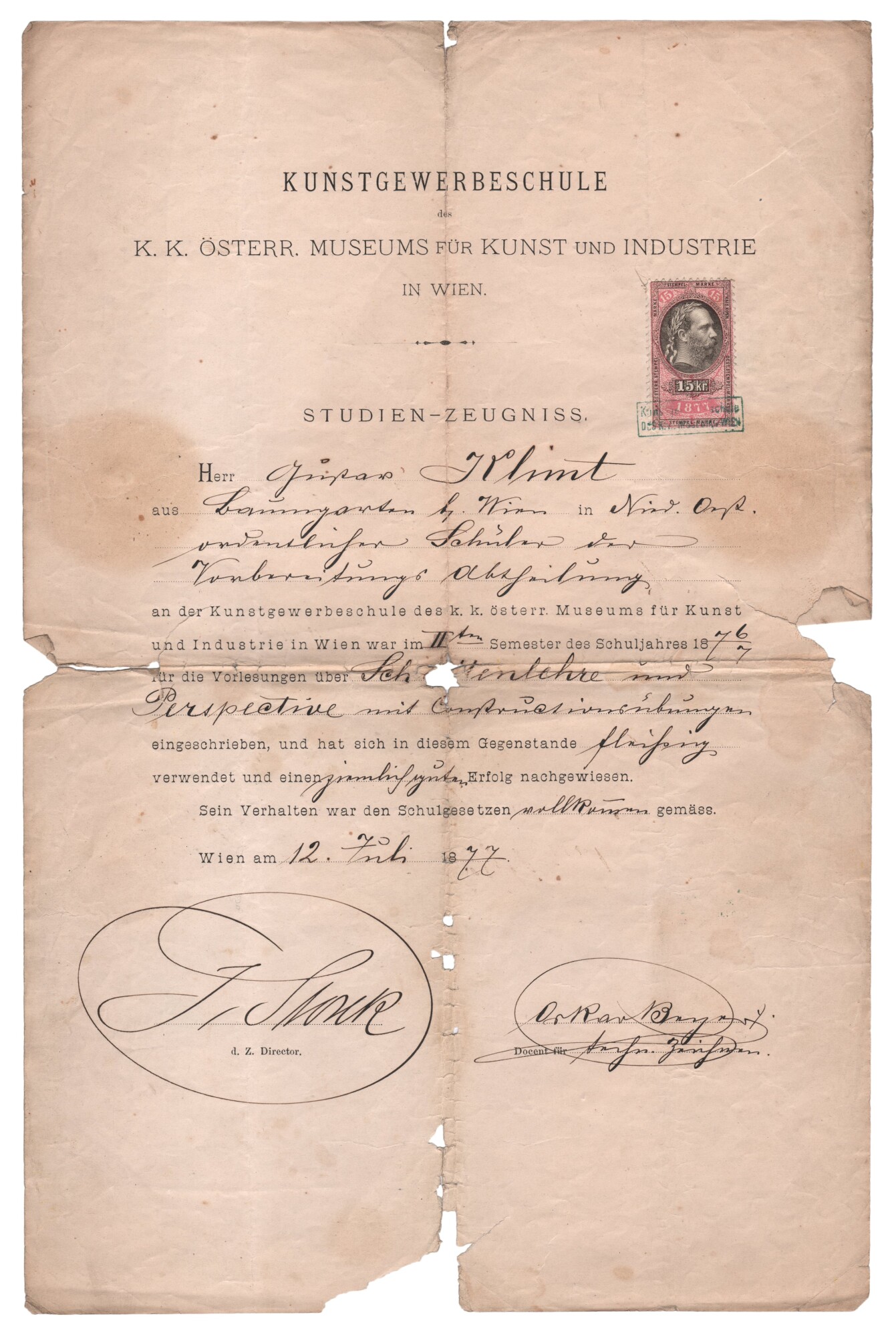

In the academic year of 1877/78, Klimt verifiably attended the classes for “Figural Drawing” headed by the painter Ludwig Minnigerode, for “Ornamental Drawing” under Professor Karl Hrachowina, as well as for “Stylistics with Drawing Exercises” under Alois Hauser. He was further instructed by Oskar Berger in technical drawing. In the subject “Figural Drawing,” Klimt had several teachers – along with Minnigerode, the young artist was also instructed by Ferdinand Laufberger and Michael Rieser during his first years of study. Klimt’s reports attest him “excellent” and “very good” performances, and describe him as consistently “very diligent.” This kind of assessment can be found in all of his extant certificates. Gustav Klimt was a distinguished, gifted and dedicated student whose teachers appreciated his achievements and promoted his talent.

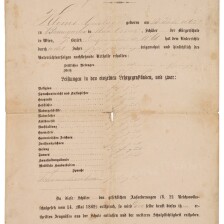

Gustav Klimt’s Certificates from the Academic Years 1875/76 to 1877/78

-

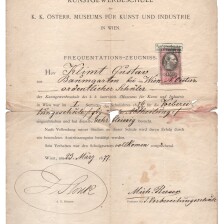

Frequentation certificate from the Imperial and Royal School of Arts and Crafts in Vienna for Gustav Klimt, completed and signed by Michael Rieser and Josef von Storck, 03/23/1877, Universität für angewandte Kunst Wien, Kunstsammlung und Archiv

Frequentation certificate from the Imperial and Royal School of Arts and Crafts in Vienna for Gustav Klimt, completed and signed by Michael Rieser and Josef von Storck, 03/23/1877, Universität für angewandte Kunst Wien, Kunstsammlung und Archiv

© University of Applied Arts Vienna, Collection & Archive -

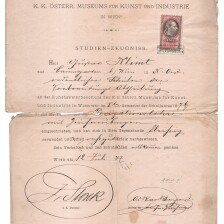

Study certificate from the Imperial and Royal School of Arts and Crafts in Vienna for Gustav Klimt, completed and signed by Oskar Beyer and Josef von Storck, 07/12/1877, Universität für angewandte Kunst Wien, Kunstsammlung und Archiv

Study certificate from the Imperial and Royal School of Arts and Crafts in Vienna for Gustav Klimt, completed and signed by Oskar Beyer and Josef von Storck, 07/12/1877, Universität für angewandte Kunst Wien, Kunstsammlung und Archiv

© University of Applied Arts Vienna, Collection & Archive -

Study certificate from the Imperial and Royal School of Arts and Crafts in Vienna for Gustav Klimt, completed and signed by Oskar Beyer and Josef von Storck, 07/12/1877, Universität für angewandte Kunst Wien, Kunstsammlung und Archiv

Study certificate from the Imperial and Royal School of Arts and Crafts in Vienna for Gustav Klimt, completed and signed by Oskar Beyer and Josef von Storck, 07/12/1877, Universität für angewandte Kunst Wien, Kunstsammlung und Archiv

© University of Applied Arts Vienna, Collection & Archive -

Certificate from the Imperial and Royal School of Arts and Crafts in Vienna for Gustav Klimt, completed and signed by Ludwig Minnigerode and Ferdinand Laufberger, 07/25/1878, Universität für angewandte Kunst Wien, Kunstsammlung und Archiv

Certificate from the Imperial and Royal School of Arts and Crafts in Vienna for Gustav Klimt, completed and signed by Ludwig Minnigerode and Ferdinand Laufberger, 07/25/1878, Universität für angewandte Kunst Wien, Kunstsammlung und Archiv

© University of Applied Arts Vienna, Collection & Archive

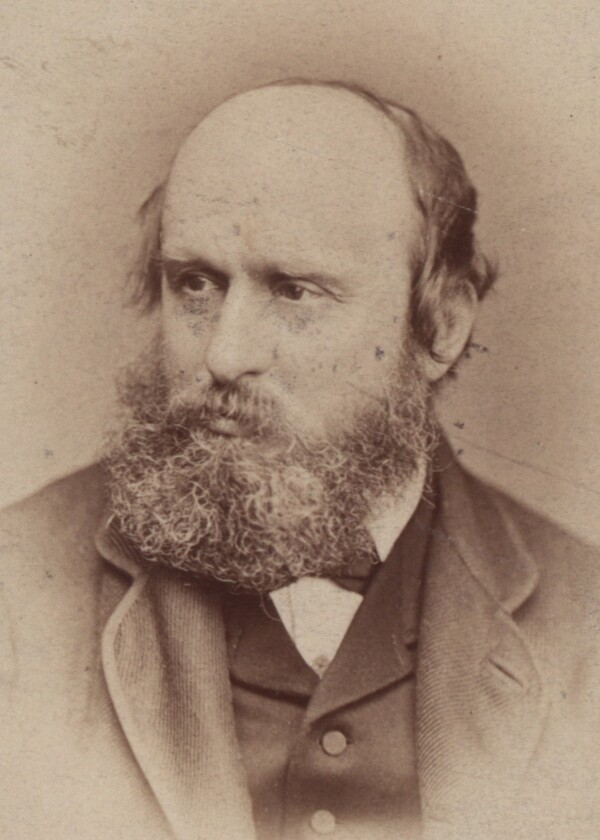

Ferdinand Laufberger, in: Neue Illustrierte Zeitung, 31.07.1881.

© ANNO | Austrian National Library

Transferring to the Special Drawing and Painting Class

After two years, Klimt’s training as a drawing instructor was all but finished, with only the final examination still outstanding. However, the Director of the School of Arts and Crafts, Ferdinand Laufberger, had become aware of the young artists Franz Matsch and Ernst and Gustav Klimt. He offered them a place in the Drawing and Painting Class headed by him, where they could train to become decorative painters. Matsch and Klimt transferred to this class in the academic year of 1878/79, with Ernst joining them the following year. Looking back, Klimt outlined his education in a curriculum vitae, written in 1893, as follows:

“In October 1876, I was admitted as a regular student to the School of Arts and Crafts of the Austrian Museum of Art and Industry, where I studied for 2 years at the preparatory school under Professors Rieser, Minnigerode and Hrachowina, and received further training at the Special Painting Class headed by Prof. Ferd[inand] Laufberger, studying with him until his death in 1881, and continuing my education at the same class under Prof. Berger for another 2 years. In total, I studied for seven years.”

Literature and sources

- Klassenkataloge 1876–1881, .

- Emil Pirchan: Gustav Klimt, Vienna 1956, S. 15-16.

- Herbert Giese: Matsch und die Brüder Klimt. Regesten zum Frühwerk Gustav Klimts, in: Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Galerie, 22/23. Jg., Nummer 66/67 (1978/79), S. 48-68.

- Franz Matsch: Autobiografische Schriften. Privatbesitz.

- Christian M. Nebehay: Gustav Klimt. Sein Leben nach zeitgenössischen Berichten und Quellen, Vienna 1969.

- Frequentations-Zeugnis der k. k. Kunstgewerbeschule in Wien für Gustav Klimt, ausgefüllt und unterschrieben von Michael Rieser und Josef von Storck, Vorbereitungsschule (03/23/1877). Klimt_14074-Aut, .

- Lebenslauf, eigenhändig verfasst von Gustav Klimt (12/21/1893). Beilage zu Verwaltungsakt Zl. 497-1893, .

- Zeugnis der k. k. Kunstgewerbeschule in Wien für Gustav Klimt, ausgefüllt und unterschrieben von Ludwig Minnigerode und Ferdinand Laufberger, Vorbereitungsschule (07/25/1878). Klimt_14077-Aut, .

- Franz Eder: Gustav Klimt und die Fotografie, in: Tobias G. Natter, Gerbert Frodl (Hg.): Klimt und die Frauen, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 20.09.2000–07.01.2001, Cologne 2000, S. 50-56.

Training as a Decorative Painter

Sgraffito by Ferdinand Laufberger, in: Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst, 17. Jg. (1882).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Ferdinand Laufberger trained Gustav Klimt, his brother Ernst and Franz Matsch to become decorative painters. He instructed them in various techniques and enlisted Klimt and his fellow students to assist with his own commissions.

The aim of the Imperial-Royal School of Arts and Crafts (now University of Applied Arts Vienna) was to bring forth designers and decorative painters with artisanal skills. The term decorative painting denotes a wall-based ornamentation which is subordinate to architecture and often depicts personifications from the arts and sciences, as opposed to monumental painting which focuses on complex mythological scenes and mental images. Both types of decorative design were used for public buildings and the palaces along the Ringstraße. In the school’s drawing class, Ferdinand Laufberger instructed future Ringstraße painters in various techniques.

“Drawing Instructors? … You Must Become Painters.”

The Klimt brothers and Franz Matsch had started studying at the Imperial-Royal School of Arts and Crafts (now University of Applied Arts Vienna) with the aim of becoming drawing instructors. However, their teachers soon noticed the three young artists’ talent. In his autobiographical notes, Matsch recalled that Rudolf Eitelberger, the director of the Museum of Art and Industry (now MAK, Vienna) which was associated with the school, said to the three young protégés when visiting the school’s workshop: “Drawing instructors? … You must become painters.” A scholarship enabled Gustav and Ernst Klimt as well as Matsch to transfer in 1878/79 to the “Drawing and Painting Class” headed by Ferdinand Laufberger. The artist afforded his students a well-rounded technical education in the techniques of tempera, watercolor, oil, casein, distemper and fresco. Seeing as Laufberger was also a successful printmaker, he taught his students how to create etchings, lithographs and woodcuts. In his class, the prospective artists even had to grind their own paints.

Gustav Klimt, Ernst Klimt, Franz Matsch: Allegories of the Fine and Applied Arts, 1879/80, Kunsthistorisches Museum

© KHM-Museumsverband

Vienna Votive Church photographed by August Stauda, around 1900

© Wien Museum

First Commissions as Decorative Painters

Laufberger fostered his gifted students’ talents not only through his lessons but also by letting them assist with many of his commissions. The trio created sgraffiti in the courtyards of the Kunsthistorisches Museum after cartoons by their teacher. The Klimt brothers and Matsch further assisted with Michael Rieser’s designs for the stained glass windows of the Votivkirche. To the young artists, these collaborations provided welcome sources of additional income.

After Laufberger’s death on 16 July 1881, the Klimt brothers and Matsch continued their education with the Makart disciple Julius Victor Berger who, like his predecessor, actively promoted his students’ talents. Though Gustav Klimt – like Ernst Klimt and Franz Matsch – received a scholarship for a trip to Italy after graduating in 1881, neither he nor his fellow students accepted the offer. Instead, their studio collective “Künstler-Compagnie” was allowed to use a workshop at the School of Arts and Crafts at Stubenring 3 for two more years, before the three artists became entirely independent decorative painters in 1883 with their own studio at Sandwirtgasse 8 in the 6th District of Vienna.

Literature and sources

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007.

- Herbert Giese: Franz von Matsch – Leben und Werk. 1861–1942. Dissertation, Vienna 1976.

- N. N.: Atelier Klimt und Matsch, in: Mittheilungen des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie. Monatsschrift für Kunst und Gewerbe, 20. Jg., Heft 232 (1885), S. 308.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alexander Klee (Hg.): Klimt und die Ringstraße, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna), 05.07.2015–11.10.2015, Vienna 2015.

First Female Portraits

Gustav Klimt: Study of a Girl's Head, 1880, private collection

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

The earliest surviving autonomous oil paintings by Gustav Klimt are study heads and academic nudes datable to the period between 1880 and 1883.

Study heads and portraits of family members in oil were also considered practicable training methods for future painters in the Drawing and Painting Class at the Imperial-Royal School of Arts and Crafts (now University of Applied Arts Vienna). Study of a Girl’s Head (c. 1880, private collection) may have been executed there. A pendant can be found in the oeuvre of Franz Matsch. Klimt’s friend captured the girl from a slightly different angle. This similarly goes for the two friends’ nude drawings. It seems that they were sitting side by side while painting, rendering the models from their individual perspectives.

As the fees for models were expensive and Gustav Klimt came from a humble background, his first sitters were family members. He also taught himself by copying portrait photographs. The portraits are conceived as busts, which means that they depict the head, breast and shoulders. In some cases the sitters appear en face in a portrait-like manner; sometimes they are shown in profile or with lowered eyes, which emphasizes the character of the study head in question.

Klimt’s First Female Portraits

-

Gustav Klimt: Lady with a Lilac Shawl, 1880-1882, Kunsthistorisches Museum

Gustav Klimt: Lady with a Lilac Shawl, 1880-1882, Kunsthistorisches Museum

© KHM-Museumsverband -

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Klara Klimt, circa 1880, ARGE Sammlung Gustav Klimt, Dauerleihgabe im Leopold Museum, Wien

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Klara Klimt, circa 1880, ARGE Sammlung Gustav Klimt, Dauerleihgabe im Leopold Museum, Wien

© Leopold Museum, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Girl's Head in Profile, circa 1880, private collection

Gustav Klimt: Girl's Head in Profile, circa 1880, private collection

© Auktionshaus im Kinsky GmbH, Vienna

The dark backdrop and tonal painting in combination with effective lighting reveal how Klimt, under the guidance of Ferdinand Laufberger, dealt with contemporary portraiture by such leading painters as Hans Makart, Franz von Lenbach, and August Friedrich von Kaulbach, thereby adopting a realistic approach.

Even in these early portraits, Gustav Klimt exhibits an interest in female models and their clothing. Lace-trimmed bonnets and collars interrupt the darkness of the dresses while framing the faces and eclipsing the sitters’ bodies. These works appear to demonstrate Klimt’s earliest concentration on prestigious female portraiture. Starting with Portrait of Sonja Knips (1897/98, Belvedere, Vienna), this would eventually lead up to a substantial series of impressive paintings of that genre by the hand of the Viennese painter.

Literature and sources

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band I, 1878–1903, Salzburg 1980.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2017.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007.

Turning to Nature

Gustav Klimt: Forest Floor, 1881/82, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Tranquil Pond, presumably 1881, private collection

© Gallery Welz Salzburg

Forest ground, profuse vegetation, and a pond were at the beginning of Gustav Klimt’s landscape painting. Apart from his commissions for decorative programs within the “Künstler-Compagnie” he studied atmospheric light effects and picturesque views of natural scenery, thus joining the tradition of a romanticized approach to nature.

In 1881/82 Klimt, who had previously mainly devoted himself to commissions related to decorative programs within the “Künstler-Compagnie”, began dealing with the genre of landscape painting, probably doing so in the context of his training in the Drawing and Painting Class.

The earliest small-size landscape studies in oil, Tranquil Pond (presumably 1881, private collection), Forest Interior (1881/82, Hida Takayama Museum of Art, Takayama), and Forest Floor (1881/82, Klimt-Foundation, Vienna), depict nature entirely in line with the style of the academic school of Atmospheric Realism then prevalent in Austria. Following in the footsteps of its leading exponents Emil Jakob Schindler and Marie Egner, Klimt painted unruffled waters and calm, intimate views into forests. He limited his palette to warm, subdued hues of browns and greens. These reduced colors bathe his landscape views in a warm light, thus creating a peaceful, almost sacred mood. All three paintings were owned by the Klimt family and therefore seem to be mere results of studies that were never made with the intention to be sold or exhibited.

Even Klimt’s early works reveal his romantic idea of nature as a refuge devoid of man and as a realm governed by a special natural power. The artist especially concentrates on capturing the atmospheric effects of light and shadow. A similar approach to nature can already be observed in the 1870s in the works of Carl Schuch, Ernst Ferdinand Oehme, and Wilhelm Trübner, and it would accompany Klimt until well into his late period.

Literature and sources

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt 150 Jahre, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 13.07.2012–27.01.2013, Vienna 2012.

- Tobias G. Natter, Elisabeth Leopold (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Sammlung im Leopold Museum, Vienna 2013.

- Ivan Ristic: Die Freiheit im Freien. Gustav Klimt als Landschaftsmaler, in: Sandra Tretter, Hans-Peter Wipplinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Jahrhundertkünstler, Ausst.-Kat., Leopold Museum (Vienna), 22.06.2018–04.11.2018, Vienna 2018.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007.

- Stephan Koja: Die Sommer in Litzlberg, in: Stephan Koja (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Landschaften, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 23.10.2002–23.02.2003, Munich 2002, S. 64-70.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2017.

Palais Sturany

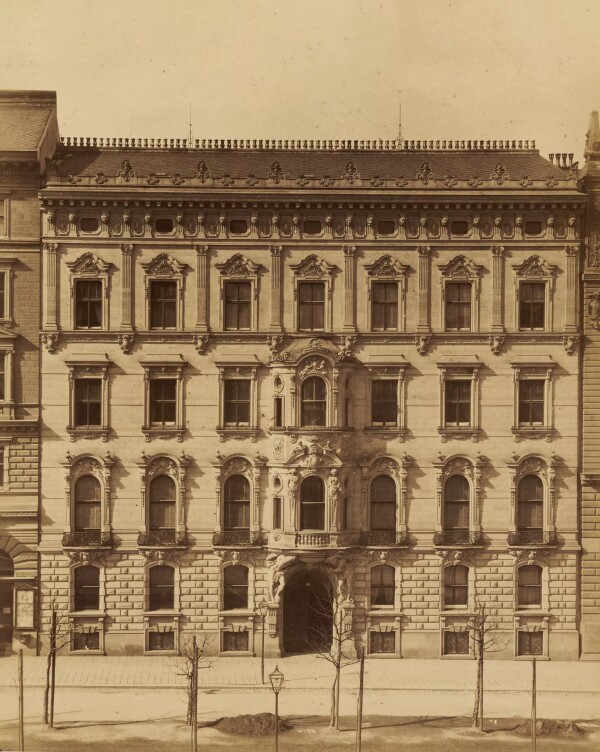

Palais Sturany, around 1880

© Wien Museum

Decorated builder's emblem inside the palace

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

As one of their first commissions, the “Künstler-Compagnie” created ceiling paintings for the salon of Palais Sturany, a mansion on the Ringstraße in Vienna designed by Fellner & Helmer. The four ceiling paintings, executed in 1880, depict personifications of the arts, with the allegory of music created by Gustav Klimt.

The Historicist mansion at Schottenring 21 in the 1st District of Vienna was designed by the architects Ferdinand Fellner and Hermann Helmer as a residential building for the Imperial-Royal court architect Johann Sturany, and built between 1874 and 1880. With this mansion, the young architects, renowned for designing theaters, established their reputation in the construction of residential buildings.

In a lecture given during a meeting of the Österreichischer Ingenieur- und Architekten-Verein [Austrian Association of Civil Engineers and Architects] in 1880, Helmer outlined the influences and reasons for the building’s design “in the quaint forms of the Baroque style” based on the construction plans. Along with the neo-Baroque stylistics, another special feature was the building’s expensive stone facade, which was usually reserved for public buildings along the Vienna Ringstraße, such as the Imperial-Royal Court Theater (now Burgtheater, Vienna) or the town hall.

Artistic Interior Design

Fellner & Helmer commissioned eminent artists of the Ringstraße era to create the elaborate decoration for Palais Sturany. These included the sculptors Franz Schönthaler, Carl Kundmann and Reinhold Völkel, as well as the ornamental blacksmith Albert Milde. The association’s periodical Wochenschrift des österreichischen Ingenieur- und Architektenvereins reported in 1881 after a survey of the building:

“The splendor and richness of this building is evident already in the facade made entirely from Stotzing stone, and in the opulent wrought-iron works adorning the portal […].”

The staircase and rooms were also given a luxurious finish, inspired by the repertoire of forms of neo-Baroque and neo-Rococo.

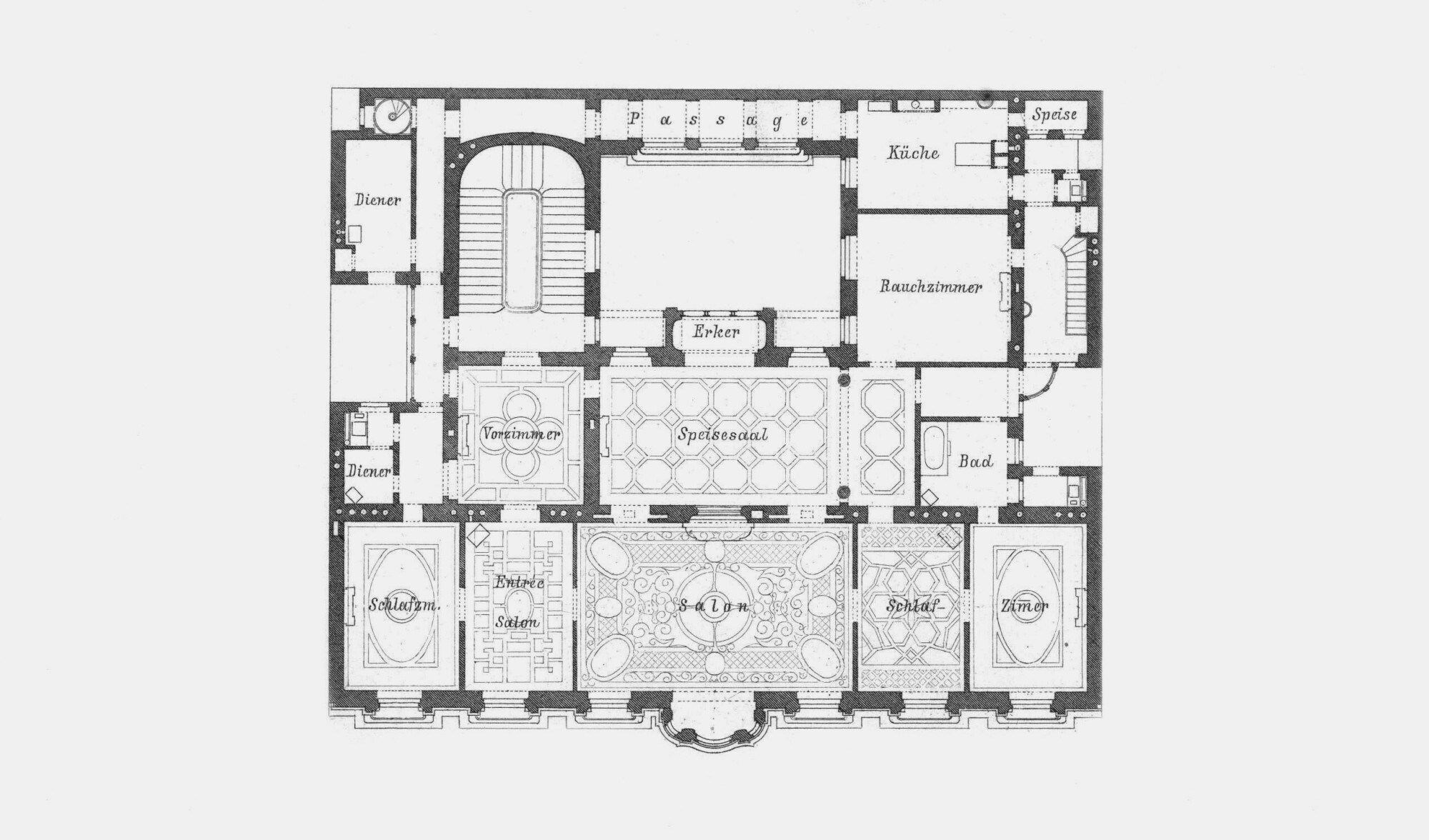

Floor plan of the 1st floor, in: Allgemeine Bauzeitung, 1885.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Personifications of the Four Arts in the Salon of Palais Sturany

-

Gustav Klimt: Allegory of Music, 1880, Internationales Dialogzentrum (KAICIID)

Gustav Klimt: Allegory of Music, 1880, Internationales Dialogzentrum (KAICIID)

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Franz Matsch: Allegory of Poetry | 1880 , undated

Franz Matsch: Allegory of Poetry | 1880 , undated

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Ernst Klimt: Allegory of the Dance | 1880 , undated, Palais Sturany

Ernst Klimt: Allegory of the Dance | 1880 , undated, Palais Sturany

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Franz Matsch: Allegory of the theater | 1880, undated

Franz Matsch: Allegory of the theater | 1880, undated

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Contemporary photograph of the salon in Palais Sturany

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Four Allegories for the Salon

The mansion’s most prestigious room, the salon, was situated on the first floor, the bel-etage. It was described as follows in the afore-mentioned journal:

“The large salon, which is accessible via a sitting room from the hall, and whose spacious bay window opens up onto the Ringstraße, is characterized by a ceiling with a sweeping cavetto, richly decorated with stucco and paintings.”

In the four corners of the room, the ceiling was decorated with paintings showing allegories of the arts in stuccoed and gilded frames. These were among the earliest commissions carried out by the “Künstler-Compagnie.” Franz Matsch and the Klimt brothers likely received the commission for these four ceiling paintings, which are still preserved today, in 1880 via their teacher Ferdinand Laufberger. Owing to two extant drafts, the allegories Theater and Poetry could be ascribed to Franz Matsch, who mentioned in his autobiographical notes that Ernst Klimt executed the work Dance. Gustav Klimt painted the work Music.

The artists oriented their depictions on the mansion’s Historicist decor. In their cartouches, reminiscent of the Baroque era, they incorporated their personifications as floating female musicians against a blue sky. The paintings recall classical role models, which they had been taught by Laufberger. Klimt depicted Music, clad in an antique-like dress, in the form of the muse Euterpe, who represents music and poetry in Greek mythology. Her attribute is the double flute – an instrument known as aulos. Her hair blowing in the wind and her flared dress emphasize the figure’s animated appearance.

Literature and sources

- N. N.: Atelier Klimt und Matsch, in: Mittheilungen des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie. Monatsschrift für Kunst und Gewerbe, 20. Jg., Heft 232 (1885), S. 308.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012, S. 522.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007, S. 232.

- P. L.: Fachgruppe für Architektur und Hochbau. Excursions-Bericht vom 6. März 1881, in: Wochenschrift des österreichischen Ingenieur- und Architektenvereines, Nummer 6 (1881), S. 101.

- Th. Hoppe: Fachgruppe für Architektur und Hochbau.. Bericht über die XXXVI. Versammlung am 15. Jänner 1880, in: Wochenschrift des österreichischen Ingenieur- und Architektenvereines, Nummer 5 (1880), S. 21.

- N. N.: Wohnhaus des Herrn Johann Sturany, am Schottenring in Wien, in: Allgemeine Bauzeitung, 1885, S. 8.

- Lebenslauf, eigenhändig verfasst von Gustav Klimt (12/21/1893). Beilage zu Verwaltungsakt Zl. 497-1893, .

- Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien (Hg.): Franz von Matsch. Ein Wiener Maler der Jahrhundertwende, Ausst.-Kat., Museums of the City of Vienna (Vienna), 12.11.1981–31.01.1982, Vienna 1981, S. 36-37.

- Bundesdenkmalamt (Hg.): DEHIO WIEN. 1. Bezirk. Innere Stadt, Vienna 2003, S. 591-593.

- Franz Matsch: Autobiografische Schriften. Privatbesitz.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2017, S. 466.

- Herbert Giese: Matsch und die Brüder Klimt. Regesten zum Frühwerk Gustav Klimts, in: Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Galerie, 22/23. Jg., Nummer 66/67 (1978/79), S. 48-68.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco (Hg.): Gustav Klimt und die Künstler-Compagnie, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 20.06.2007–14.10.2007, Weitra 2007, S. 9-11.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alexander Klee (Hg.): Klimt und die Ringstraße, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna), 05.07.2015–11.10.2015, Vienna 2015.

Kursalon Karlsbad

Kursalon in Karlovy Vary, around 1890

© SLUB / Deutsche Fotothek

Interior of the Kursalon, around 1900

© Muzeum Karlovy Vary

In 1880/81, the new Kursalon was built in the municipal park of Karlsbad to designs by the Viennese architects Fellner & Helmer. The building’s barrel-vaulted main hall, which no longer exists today, was decorated by the “Künstler-Compagnie” with “ceiling paintings.”

In October 1880, the municipality of Karlsbad (now Karlovy Vary, Czech Republic) granted the Viennese architect duo Fellner & Helmer permission “to build premises complete with a promenade and pavilions in the municipal park.” The opening of the establishment took place already in June of the following year, drawing “an enormous crowd.”

Sources on a Lost Work

Seeing as the building erected by Fellner & Helmer was demolished in 1966, and since there is hardly any photographic documentation of it, it has not been possible as yet to fully reconstruct and appraise the decoration of the Kursalon which, by their own admissions, the Klimt brothers and Franz Matsch were involved in.

There are, however, some sources about this early commission for the “Künstler-Compagnie.” These include Gustav Klimt’s handwritten curriculum vitae and its 1893 draft. In his CV, he mentioned “ceiling paintings” created by him in 1880 for the new premises in Karlsbad, without going into further detail. In terms of the size of the commission, Matsch recalled in his memoirs Autobiografische Skizzen that it included four canvases, which he titled Religious Music, Hunting Music, Dance Music and Wedding Music. An 1885 review of the studio of Klimt and Matsch in the renowned art periodical Mittheilungen des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie [Communications from the Imperial-Royal Austrian Museum of Art and Industry] instead mentioned “six distemper ceiling paintings for the concert hall in Carlsbad.”

Franz Matsch: Dance of the Italians - design for a ceiling painting, 1880/81, Belvedere, Vienna

© Belvedere, Vienna, Photo: Johannes Stoll

Franz Matsch: Wedding celebration on a boat, around 1880, Belvedere Vienna

© Belvedere, Vienna, Photo: Johannes Stoll

Gustav Klimt (?): Allegory of agriculture, presumably circa 1880

© Image courtesy of Skinner, Inc.

The latter statement appears to be corroborated by a publication about Karlsbad from 1937. It describes a total of six ceiling paintings in the Kursalon, depicting “romantic scenes from the lives of the people.” More specifically, the article mentions “a dancing couple wearing traditional Hungarian costumes, a quaint shepherd’s idyll, the dance of the Italians, a couple standing devoutly before an effigy of the Mother of God, rural life on a shore landscape, and the joys of hunting.” Interestingly, the author ascribed these works only to Klimt’s teacher, Ferdinand Laufberger, without mentioning Gustav Klimt and his two colleagues. All the more noteworthy, then, is a 1883 entry from the journal Mitteilungen des k. k. österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie, which states: “They decorated the concert hall in Karlsbad under Laufberger’s guidance, and further participated in their teacher’s sgraffito works.”

Lately, this has prompted researchers to speculate whether the large-scale commission might have been given only to Laufberger, who subsequently delegated it to the Klimt brothers and Franz Matsch.

Klimt’s Missing Sketches and Drafts

There are no extant sketches or studies created by Gustav Klimt for this particular commission. Only a fanlight-shaped draft with the title Allegory of Agriculture (1880/81, private collection), which is ascribed to the artist, is often mentioned in this context. Whether it was actually created in connection with this commission can no longer be proven today. Likely the only surviving colored draft for the Kursalon in Karlsbad is one by Franz Matsch.

Literature and sources

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012, S. 522-523.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007, S. 233.

- Lebenslauf, eigenhändig verfasst von Gustav Klimt (12/21/1893). Beilage zu Verwaltungsakt Zl. 497-1893, .

- Mittheilungen des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie. Monatsschrift für Kunst und Gewerbe, 18. Jg., Heft 209 (1883), S. 335.

- Herbert Giese: Matsch und die Brüder Klimt. Regesten zum Frühwerk Gustav Klimts, in: Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Galerie, 22/23. Jg., Nummer 66/67 (1978/79), S. 48-68.

- Markus Fellinger: Ceiling Paintings and Theatre Curtains of The Atelier Klimt Brothers and Franz Matsch, in: Deborah Pustišek Antić (Hg.): The Unknown Klimt. Love, Death, Ecstasy, Ausst.-Kat., Muzej Grada Rijeke (Rijeka), 20.04.2021–20.10.2021, Rijeka 2021, S. 24-31.

- Entwurf für einen Lebenslauf, eigenhändig verfasst von Gustav Klimt (vor dem 21.12.1893). S189.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band IV, 1878–1918, Salzburg 1989, S. 14, S. 18.

- Neuigkeits-Welt-Blatt, 28.10.1880, S. 27.

- Prager Tagblatt, 17.10.1880, S. 5.

- Neue Freie Presse, 07.06.1881, S. 2.

- Eugen Linke: Heimatkunde des Bezirkes Karlsbad, Heft 2, Carlsbad 1937, S. 31.

- N. N.: Atelier Klimt und Matsch, in: Mittheilungen des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie. Monatsschrift für Kunst und Gewerbe, 20. Jg., Heft 232 (1885), S. 308.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco (Hg.): Gustav Klimt und die Künstler-Compagnie, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 20.06.2007–14.10.2007, Weitra 2007.

Palais Zierer

Palais Zierer entrance portal in Alleegasse photographed by August Stauda, around 1900

© Wien Museum

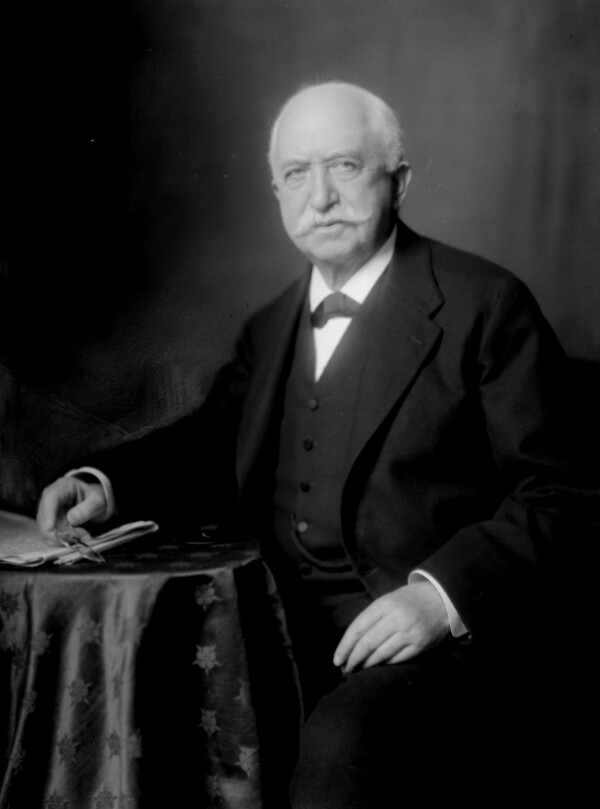

Wilhelm Zierer photographed by Madame d'Ora, 1914

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Julius Victor Berger: Design for a ceiling painting in Palais Zierer, 1881

© Graphic Collection of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna

In 1881/82, Julius Victor Berger afforded his students Franz Matsch and the Klimt brothers the opportunity to participate in one of his own decorative commissions – the decoration of the newly erected Palais Zierer in Vienna. It is believed that the “Künstler-Compagnie” was largely responsible for the independent execution of several ceiling paintings which were based on preliminary sketches by Berger.

The neo-Baroque Palais Zierer (now Palais Kranz) was erected on Alleegasse (now Argentinierstraße 25-27) in the 4th District of Vienna to plans by the architect Gustav Korompay. The building had been commissioned by the banker Wilhelm Zierer. According to an entry in the land register printed in 1881 in the newspaper Der Bautechniker, the banker had bought the plot, spanning 1700 square meters, for 47,000 guilders (c. 657,000 euros).

Interior Decoration

The interior of the newly built Palais Zierer was decorated by the artist Tina Blau, who had been commissioned at the behest of Korompay, as well as by Klimt’s teacher Julius Victor Berger, who created ceiling paintings for the staircase, among other works.

Already on 4 March 1882, the art journal Österreichische Kunst-Chronik reported that Berger’s pupils had taken on some of his work for Zierer’s new residence. A report in the monthly magazine Monatsschrift für Kunst und Gewerbe in 1883 named Ernst and Gustav Klimt as well as Franz Matsch as the students who painted “the four seasons for Palais Zierer on Alleegasse after sketches by Professor Berger.” Based on Berger’s preliminary drafts, which are housed today at the print room of the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, the young artists developed their own detailed studies and preparatory sketches, among them a watercolored draft for a spandrel painting by Franz Matsch. From today’s perspective, it is almost impossible to distinguish the hands of the individual artists, which meant that the members of the “Künstler-Compagnie” had mastered the objective of their training: Their similar artistic hand and means of expression made the Klimt brothers and Franz Matsch ideal decorative painters, able to design paintings in a uniform style and in keeping with the building’s architecture, and to execute these works quickly.

Sale of a Jewel and Magnificent Building

On 28 May 1888, the newspaper Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung’s evening edition devoted only one line to the news that the banker Zierer had sold his mansion on Alleegasse after only a few years. According to the press release, it was said to have been sold for 500,000 guilders (c. 7,622,000 euros). A few days later, an unknown journalist dedicated a more extensive article to the unexpected house sale in the same paper. The author regretted that the building had been sold, as he felt that Zierer’s residence – a “jewel of splendid interior design, of opulent luxury and tasteful elegance” – had been on its way to becoming a much-admired place of interest in the metropolis Vienna:

“Those who visited it admired the wealth, taste and fondness of ostentation of its owner as much as the artistic genius, the creative spirit of its architect Korompay, who designed this delightful home.”

The building was sold to Baron Hermann Springer, who owned it until his death in 1895, when it entered into the possession of his niece. It was bought in 1899 by the industrialist Josef Kranz, who partially converted it. Today, the building houses the trade mission of the Russian Federation.

Literature and sources

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012, S. 523-524.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007, S. 233.

- N. N.: Atelier Klimt und Matsch, in: Mittheilungen des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie. Monatsschrift für Kunst und Gewerbe, 20. Jg., Heft 232 (1885), S. 308.

- Mittheilungen des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie. Monatsschrift für Kunst und Gewerbe, 18. Jg., Heft 209 (1883), S. 335.

- Herbert Giese: Franz von Matsch – Leben und Werk. 1861–1942. Dissertation, Vienna 1976, S. 8.

- Felix Czeike (Hg.): Historisches Lexikon Wien, Band 5, Vienna 1997, S. 705.

- Wiener Abendpost. Beilage zur Wiener Zeitung, 03.09.1881, S. 4.

- Wiener Hausfrauen-Zeitung, 05.01.1902, S. 34.

- Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 29.05.1888, S. 5.

- Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, 18.04.1882, S. 4.

- Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, 31.05.1888, S. 5-6.

- Neue Freie Presse, 17.09.1899, S. 8.

- Der Bautechniker. Centralorgan für das österreichische Bauwesen, 1. Jg., Nummer 40 (1881), S. 326.

- Der Bautechniker. Centralorgan für das österreichische Bauwesen, 2. Jg., Nummer 23 (1882), S. 233.

- Der Bautechniker. Centralorgan für das österreichische Bauwesen, 19. Jg., Nummer 49 (1899), S. 1099.

- Die Arbeit, 17.02.1895, S. 81.

- Österreichische Kunst-Chronik, Nummer 9 (1882), S. 109.

- Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung (Abendausgabe), 28.05.1888, S. 2.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco (Hg.): Gustav Klimt und die Künstler-Compagnie, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 20.06.2007–14.10.2007, Weitra 2007, S. 16-17.

Stadttheater Brünn

Brno City Theater, in: Neue Illustrierte Zeitung, 26.11.1882.

© ANNO | Austrian National Library

By 1882, the “Künstler-Compagnie” had firmly established itself as a trio of versatile and congenial decorative painters who cooperated with the architectural office Fellner & Helmer. It was likely also at the architects’ behest that the three young artists created sgraffiti for the new municipal theater in Brünn.

In May 1881, the reputable Viennese architectural office Fellner & Helmer was officially tasked with planning and erecting a new, free-standing theater building in the Moravian town of Brünn (now Brno, Czech Republic). The newspaper Die Presse reported on 26 May 1881:

“The [Brno] municipal committee conclusively decided today on the building of a theater, and to this end approved a budget of 400,000 guilders. The theater is to be completed and ready for performances latest by 15 October 1882. The architect Fellner in Vienna has been chosen to design the building plans, as he has plenty of experience with the construction of theaters.”

As the time frame for the construction of the new performance venue (now Mahenovo divadlo, Brno) of 1881/82 was rather tight, the plans for the new theater building were presented already in July at the assembly hall of the local town hall. Construction work was set to begin the following month. Fellner & Helmer paid particular attention to structural safety measures and fire protection. In January 1882, the contracting authority invested an additional 30,000 guilders (c. 425,000 euros) into these measures on account of the fatal fire disaster at the Ringtheater which had taken place in December 1881. Furthermore, the responsible municipal committee requested that the two architects fit the theater’s interior and exterior with electric lighting in the summer of 1882. However, this could not be completed in time for the planned opening in late October/early November of 1882. According to a report in the newspaper Prager Abendblatt on 7 November 1882, this caused the theater’s opening to be postponed several times. The inaugural performance was finally staged on 14 November 1882.

Decorative Works Created by the “Künstler-Compagnie”

To date, only one written source could be found that documents the involvement of the “Künstler-Compagnie” in the decoration of the Stadttheater Brünn: The monthly magazine of the Imperial-Royal Austrian Museum of Art and Industry Mittheilungen des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie. Monatsschrift für Kunst und Gewerbe reported in 1885 that the “Atelier Klimt and Matsch” was commissioned – likely directly by Fellner & Helmer – to execute “four cartoons for the municipal theater in Brünn.” It is believed today that the report refers to the drafts for the ornamental panels between the windows on the second floor on the building’s eastern, western and northern side, which were executed using the sgraffito technique. The works depict plant arabesques with children and putti with banners and violins, as well as cornucopias and birds. Both in terms of themes and style, the compositions follow the tradition of Historicism and the manner of painting taught by Laufberger.

Further contents

Literature and sources

- N. N.: Atelier Klimt und Matsch, in: Mittheilungen des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie. Monatsschrift für Kunst und Gewerbe, 20. Jg., Heft 232 (1885), S. 308.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012, S. 524.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007, S. 234.

- Neue Freie Presse, 04.11.1882, S. 5-6.

- Neue Freie Presse, 05.11.1882, S. 5.

- Allgemeine Theater-Chronik. Gratis-Beilage zur Allgemeinen Kunst-Chronik, 28.10.1882, S. 4.

- Die Presse, 26.05.1881, S. 5.

- Der Bautechniker. Centralorgan für das österreichische Bauwesen, 1. Jg., Nummer 22 (1881), S. 174.

- Das interessante Blatt, 26.10.1882, S. 218-219.

- Mährisches Tagblatt, 09.06.1882, S. 6.

- Neue Illustrierte Zeitung, 24.09.1882, S. 831.

- Mährisches Tagblatt, 07.07.1881, S. 6.

- Prager Abendblatt, 07.11.1882, S. 2.

- Prager Abendblatt, 15.11.1882, S. 3.

- Prager Tagblatt, 24.10.1882, S. 7.

- Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, 11.01.1882, S. 7.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco (Hg.): Gustav Klimt und die Künstler-Compagnie, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 20.06.2007–14.10.2007, Weitra 2007.

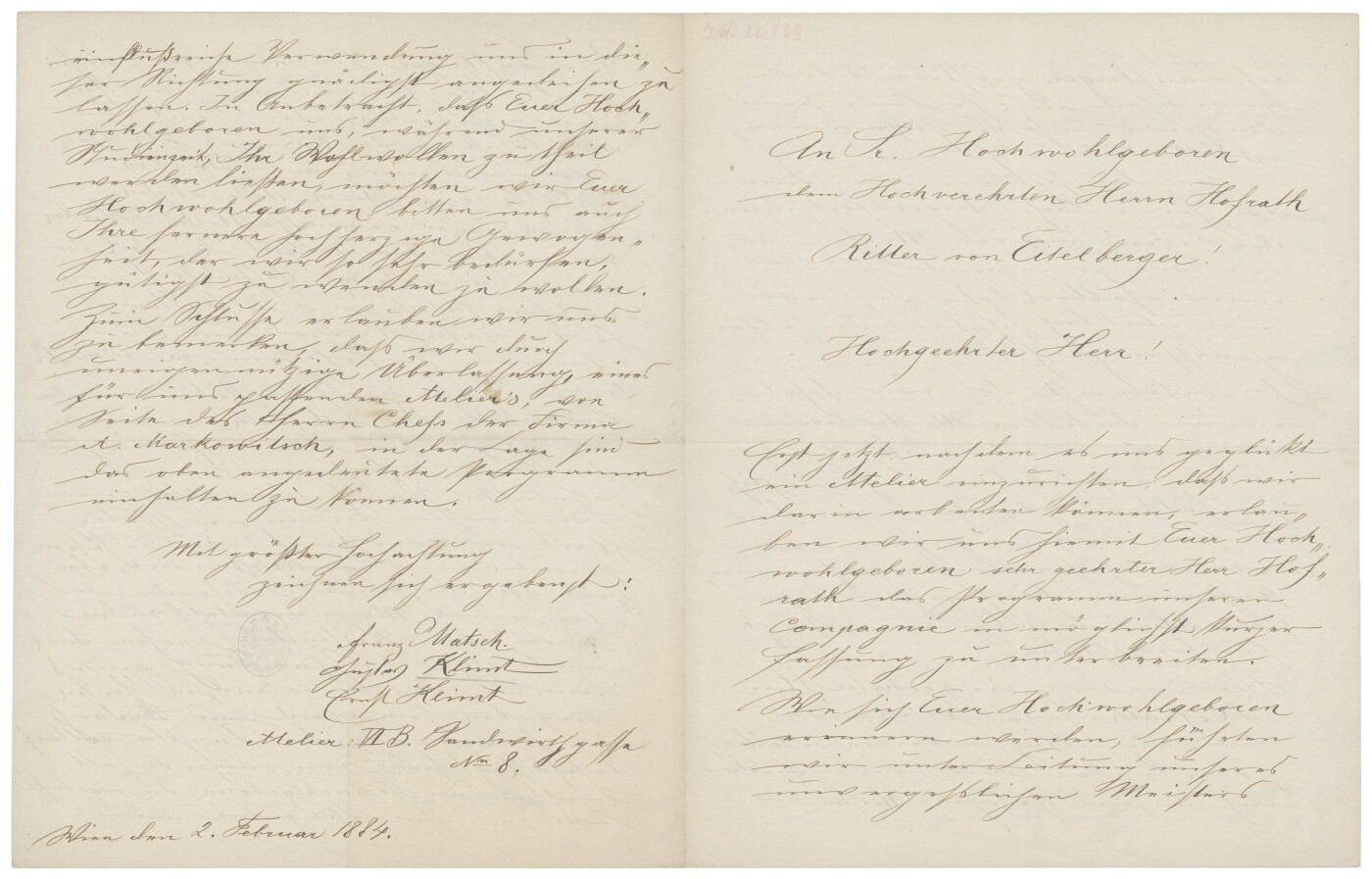

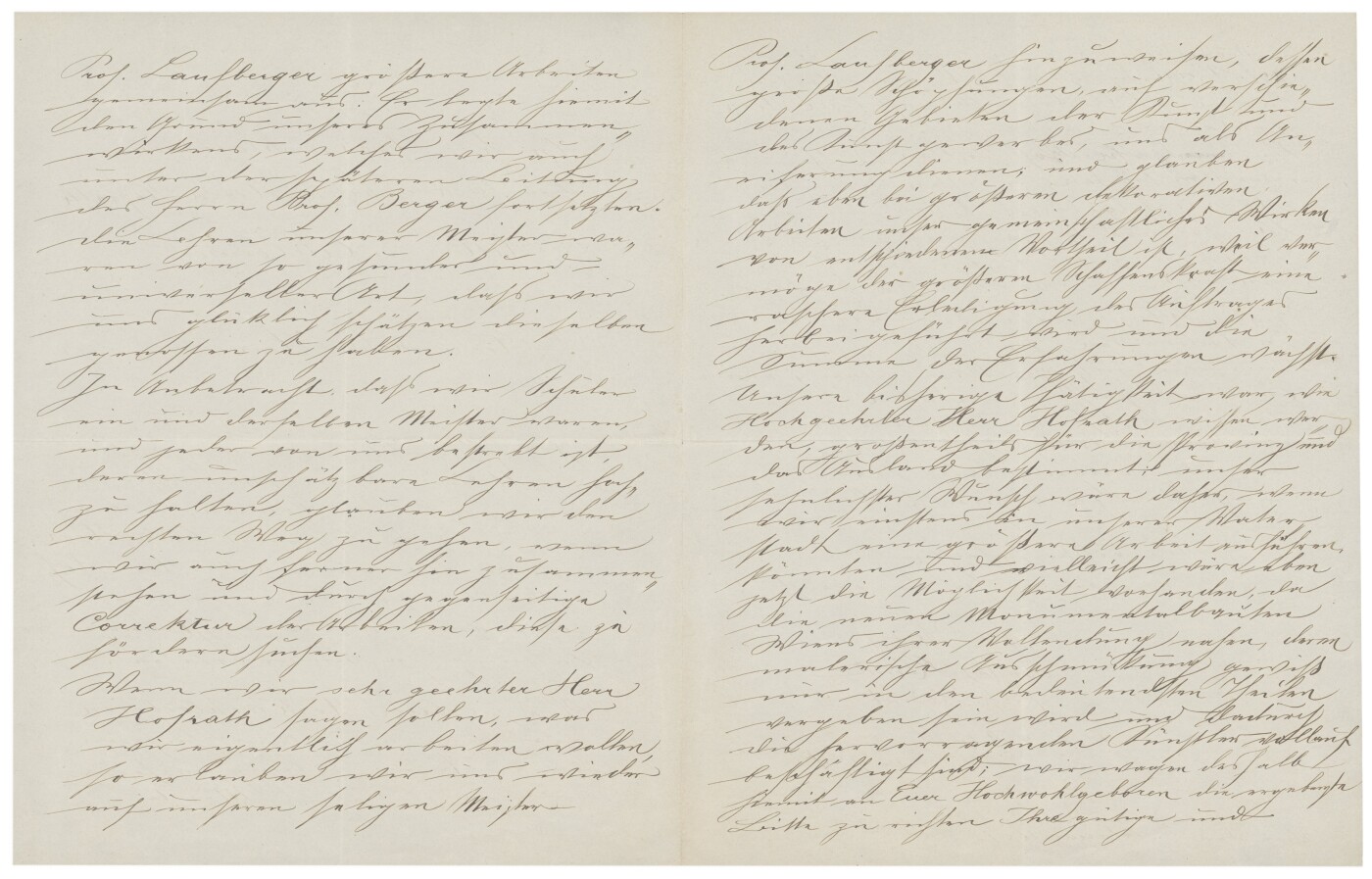

Founding of the “Künstler-Compagnie”

Franz Matsch: Letter from Franz Matsch in Vienna to the Magistrate of the City of Liberec, co-signed by Gustav and Ernst Klimt, 10/11/1883, SOkA Liberec, Archiv města Liberec (AML)

© SOkA Liberec, Archiv města Liberec (AML)

It was already during their studies that the Klimt brothers and Franz Matsch began cooperating closely. The Imperial-Royal School of Arts and Crafts provided the young artists with a studio of their own for their work. This marked the foundation of their studio partnership “Brüder Klimt and Franz Matsch.”

Around 1880/81, Gustav and Ernst Klimt banded together with Franz Matsch to form a studio partnership, the formal incorporation of which is not documented, however. In contemporary sources it is consistently referred to as “Atelier Franz Matsch und Gebrüder Klimt” [“Studio Franz Matsch and Brothers Klimt”]. The name “Künstler-Compagnie” commonly used in academic literature seems to derive from a letter to Rudolf Eitelberger in which the young artists presented the program of their “Compagnie.”

School Studio and First Independent Commissions

The transition from their status as students to their working as decorators happened gradually. Even during their years of training, Franz Matsch and Ernst and Gustav Klimt were permitted to use a studio at the school for their private commissions; they were actively supported by their teachers, who organized paid assignments for them. As early as 1880 they received their first independent commission for the decoration of the Sturany Palace, which had been built in 1874. It seems that they owed this commission to their teacher Laufberger, who had recommended them to Fellner & Helmer, the architects of the palace.

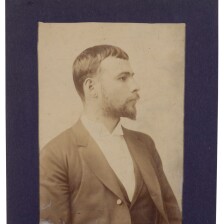

The Members of the “Künstler-Compagnie”

-

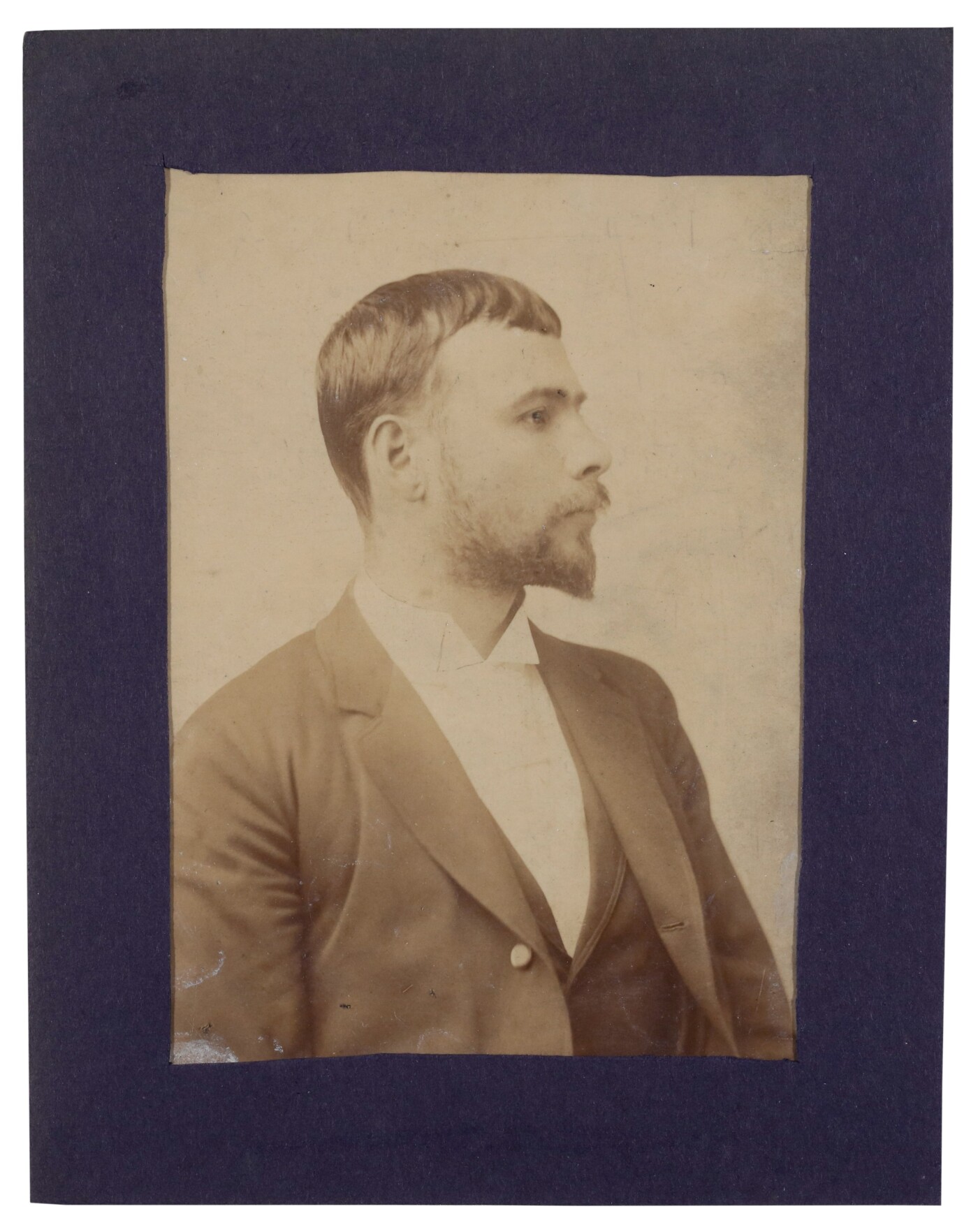

Gustav Klimt, presumably 1890, Klimt Foundation

Gustav Klimt, presumably 1890, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

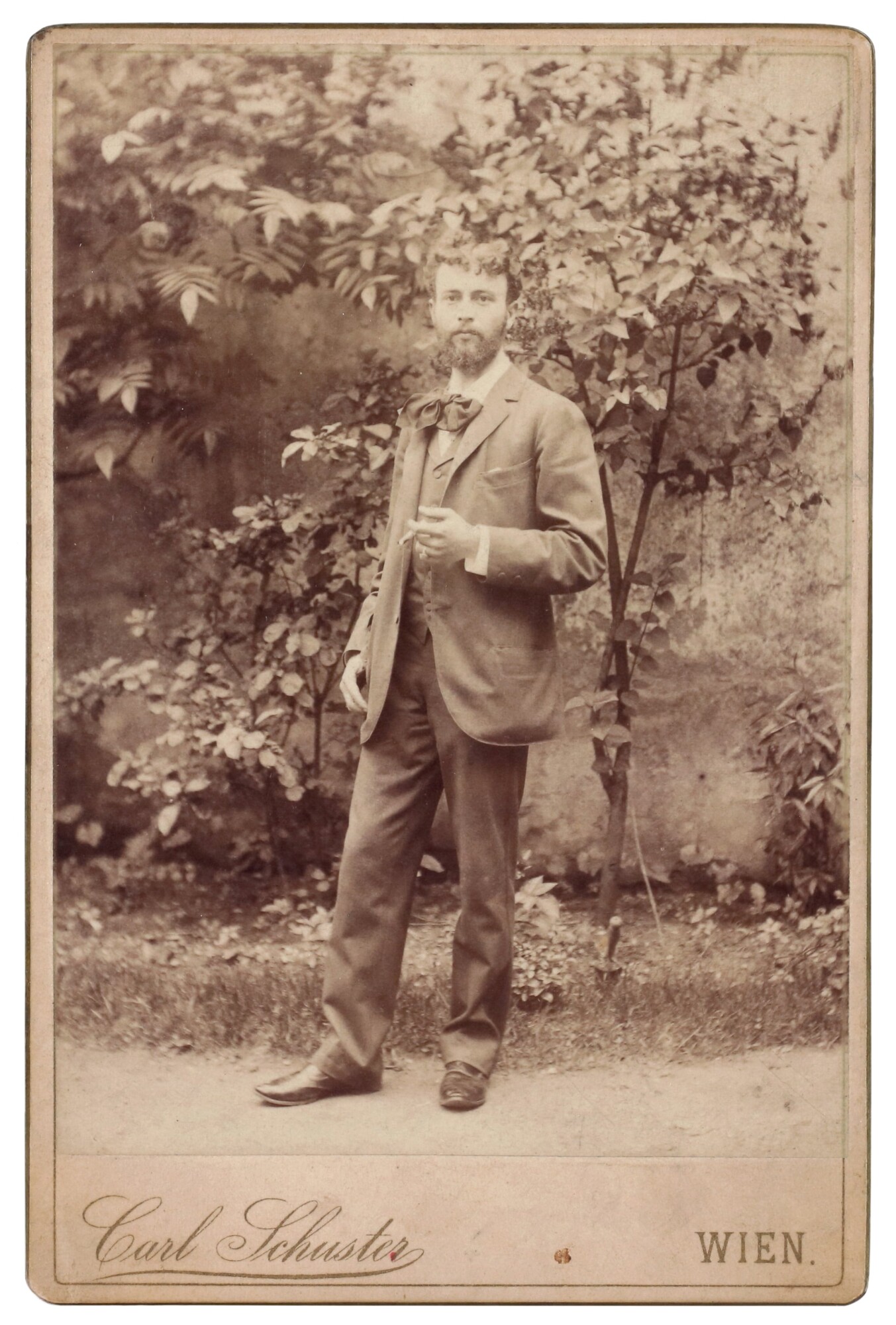

Carl Schuster: Ernst Klimt, presumably 1892, Klimt Foundation

Carl Schuster: Ernst Klimt, presumably 1892, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Franz Matsch photographed by Carl Pietzner, around 1895, Austrian National Library, Vienna

Franz Matsch photographed by Carl Pietzner, around 1895, Austrian National Library, Vienna

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Rudolf Eitelberger photographed by Ludwig Angerer, around 1880-1885

© Wien Museum

Even after they had graduated in 1881, the young artists were allowed to keep using their studio at the school. Their close cooperation with Fellner & Helmer continued after the completion of the ceiling paintings for the Sturany Palace and earned the “Künstler-Compagnie” more prestigious commissions. In 1883 the studio partnership was entrusted with painting the ceiling and main curtain for the City Theater of Reichenberg (now Liberec), which had been built by the two architects. Through their prolific work the artists had made a name of themselves as successful decorators. This put them in the position to rent their first independent studio at Sandwirtgasse 8 in Josefstadt, Vienna’s 8th District.

Program and Aims of the “Künstler-Compagnie”

In 1884 the young artists, spurred by their success, wrote a letter to Rudolf Eitelberger, the director of the Austrian Museum of Art and Industry, who had always been a big supporter of Matsch and the Klimt brothers. The purpose of the letter was to ask Eitelberger to recommend the “Künstler-Compagnie” so that it would win a contract for a decoration program within the Ringstraße construction project. In the letter, Matsch, acting as the company’s clerk, also justified the teaming-up of the Klimt brothers and himself:

“Given that we were students of the same masters and that each of us is eager to honor their invaluable teachings, we believe to have chosen the right way in holding on to our union and seeking to improve our work through mutual correction.”

He also pointed out that their collaboration within the “Künstler-Compagnie” allowed them to speedily execute even larger commissions through work division, while the fact that they had shared the same training would guarantee the homogeneity of their work. These organizational benefits and artistic considerations were to give him and his two comrades in arms a competitive edge over their rivals until the beginning of the 1890s.

Letter from Franz Matsch in Vienna to Rudolf Eitelberger in Vienna, co-signed by Ernst and Gustav Klimt

-

Franz Matsch: Letter from Franz Matsch in Vienna to Rudolf Eitelberger in Vienna, co-signed by Ernst and Gustav Klimt, 02/02/1884, Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Handschriftensammlung, Estate of Rudolf Eitelberger von Edelberg

Franz Matsch: Letter from Franz Matsch in Vienna to Rudolf Eitelberger in Vienna, co-signed by Ernst and Gustav Klimt, 02/02/1884, Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Handschriftensammlung, Estate of Rudolf Eitelberger von Edelberg

© Vienna City Library, Manuscript collection -

Franz Matsch: Letter from Franz Matsch in Vienna to Rudolf Eitelberger in Vienna, co-signed by Ernst and Gustav Klimt, 02/02/1884, Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Handschriftensammlung, Estate of Rudolf Eitelberger von Edelberg

Franz Matsch: Letter from Franz Matsch in Vienna to Rudolf Eitelberger in Vienna, co-signed by Ernst and Gustav Klimt, 02/02/1884, Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Handschriftensammlung, Estate of Rudolf Eitelberger von Edelberg

© Vienna City Library, Manuscript collection

In his letter to Eitelberger, Matsch also described the young studio partnership’s ambitious goals:

“Our previous activities largely took us [...] to the provinces and abroad; it would thus be our greatest wish to be able to realize a larger project in our hometown, and now there would probably be a good opportunity for this, as Vienna’s new monumental buildings are nearing completion.”

These aims would soon be achieved. In 1886 the “Künstler-Compagnie” won the contract for the decoration of the two staircases of the newly erected k. k. Hoftheater [Imperial-Royal Court Theater] (now Burgtheater, Vienna), followed by the commission for the staircase of the k. k. Kunsthistorisches Hofmuseum [Imperial-Royal Art History Museum] (now Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna).

Literature and sources

- N. N.: Atelier Klimt und Matsch, in: Mittheilungen des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie. Monatsschrift für Kunst und Gewerbe, 20. Jg., Heft 232 (1885), S. 308.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007.

- Herbert Giese: Franz von Matsch – Leben und Werk. 1861–1942. Dissertation, Vienna 1976.

- Brief von Franz Matsch in Wien an Rudolf Eitelberger in Wien, mitunterschrieben von Ernst und Gustav Klimt (02.02.1884). H.I.N. 22.439, .

- Korrespondenzkarte von Ferdinand Laufberger in Wien an Gustav Klimt in Wien (24.01.1880). GKA51.

- Adolph Lehmann's allgemeiner Wohnungs-Anzeiger. Nebst Handels- u. Gewerbe-Adressbuch für d. k. k. Reichshaupt- u. Residenzstadt Wien u. Umgebung, 31. Jg. (1889), S. 627.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alexander Klee (Hg.): Klimt und die Ringstraße, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna), 05.07.2015–11.10.2015, Vienna 2015.

Drawings

Gustav Klimt: Head study after the plaster model of "Brunn's head" in three-quarter profile to the left, 1878, Universität für angewandte Kunst Wien, Kunstsammlung und Archiv

© University of Applied Arts Vienna, Collection & Archive

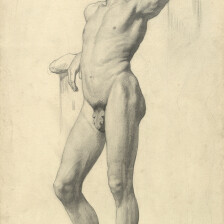

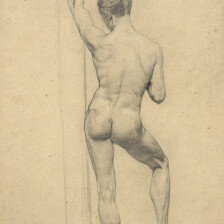

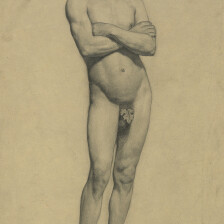

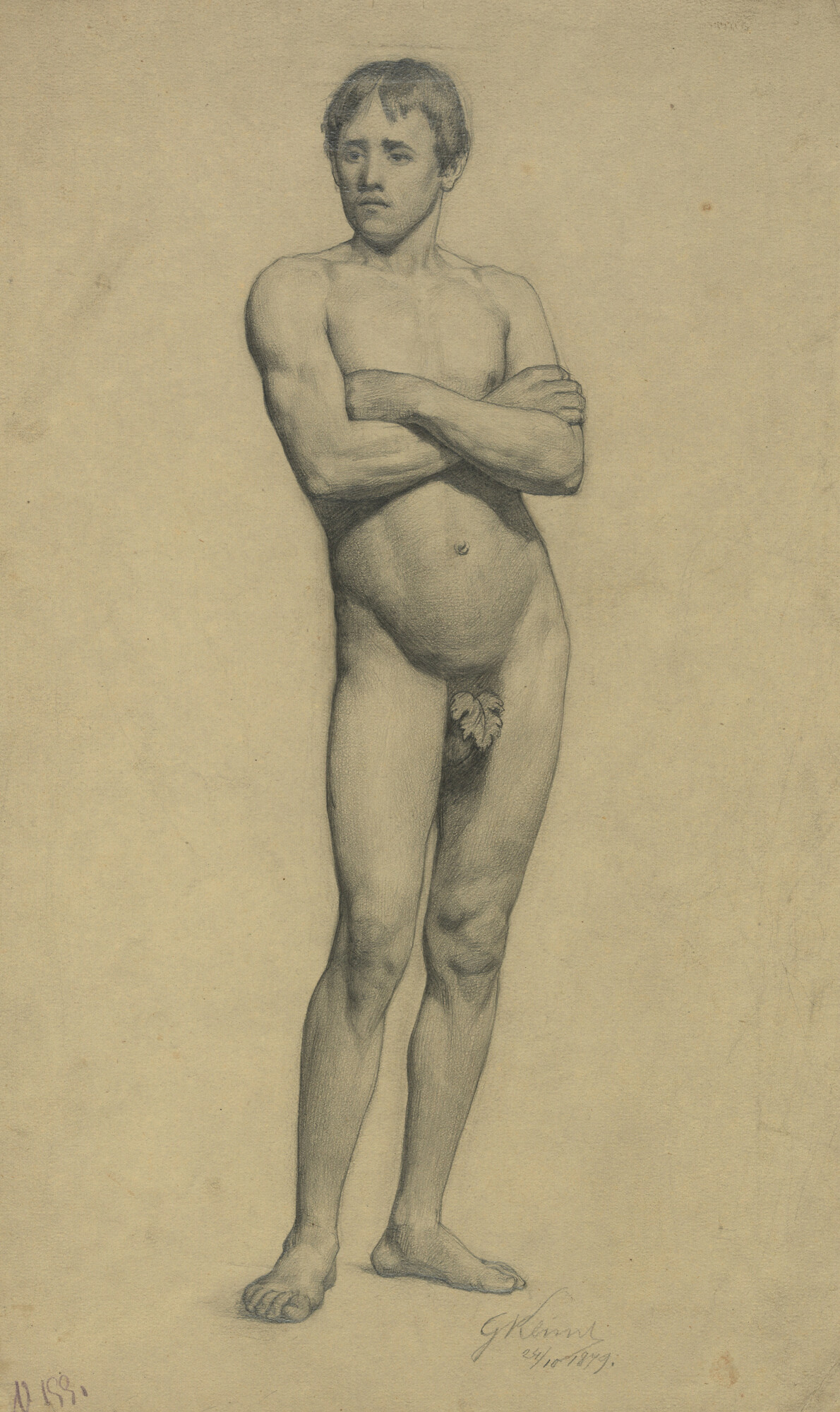

Even the drawings from his first years as a student, when Klimt trained by copying plaster statues and sketching portraits, reveal the artist’s outstanding talent. In the Drawing and Painting Class, individual anatomical studies undertaken in life drawing sessions were part of the instructions in drawing.

Drawing from Plaster Casts

The first part of an artist’s training consisted in copying antique sculptures or plaster casts. In this way, the students were meant to learn how to convincingly translate three-dimensional objects into the two-dimensional medium of drawing. The study of an acanthus tendril (private collection, S 1980: 1) and of the study of the so-called “Brunn’scher Kopf” [“Head Brunn”] (private collection, S 1980: 2), the original of which is conserved at the Munich Glyptothek, are among the few surviving early drawings. The head study, drawn on olive green paper, is dated 7 February 1878 and was thus made during Klimt’s final term at prep school. It shows his virtuoso handling of light and shadow and a compellingly three-dimensional rendering of the bust, documenting Klimt’s extraordinary talent as an artist. The drawing comes from the personal collection of Klimt’s teacher Ludwig Minnigerode.

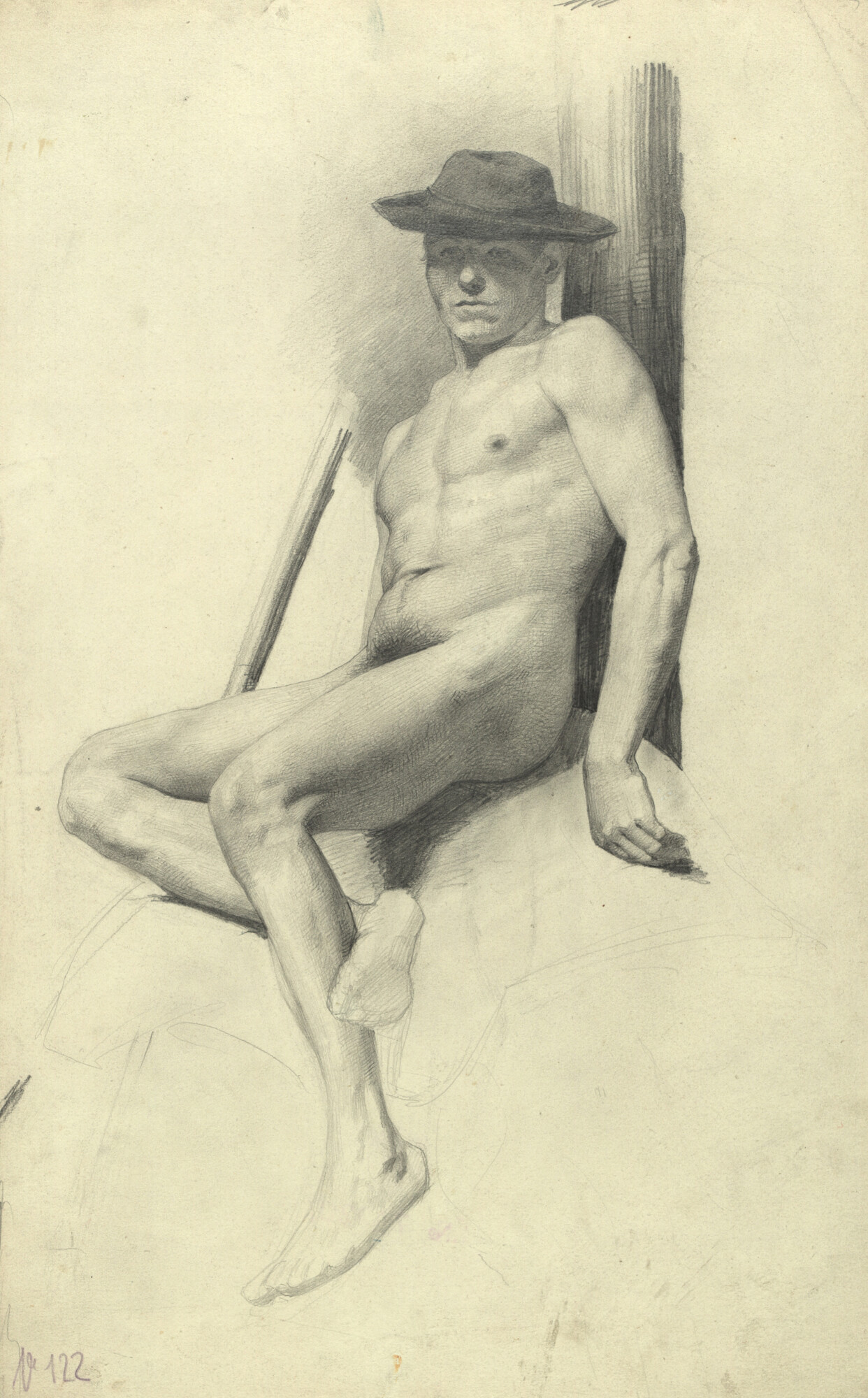

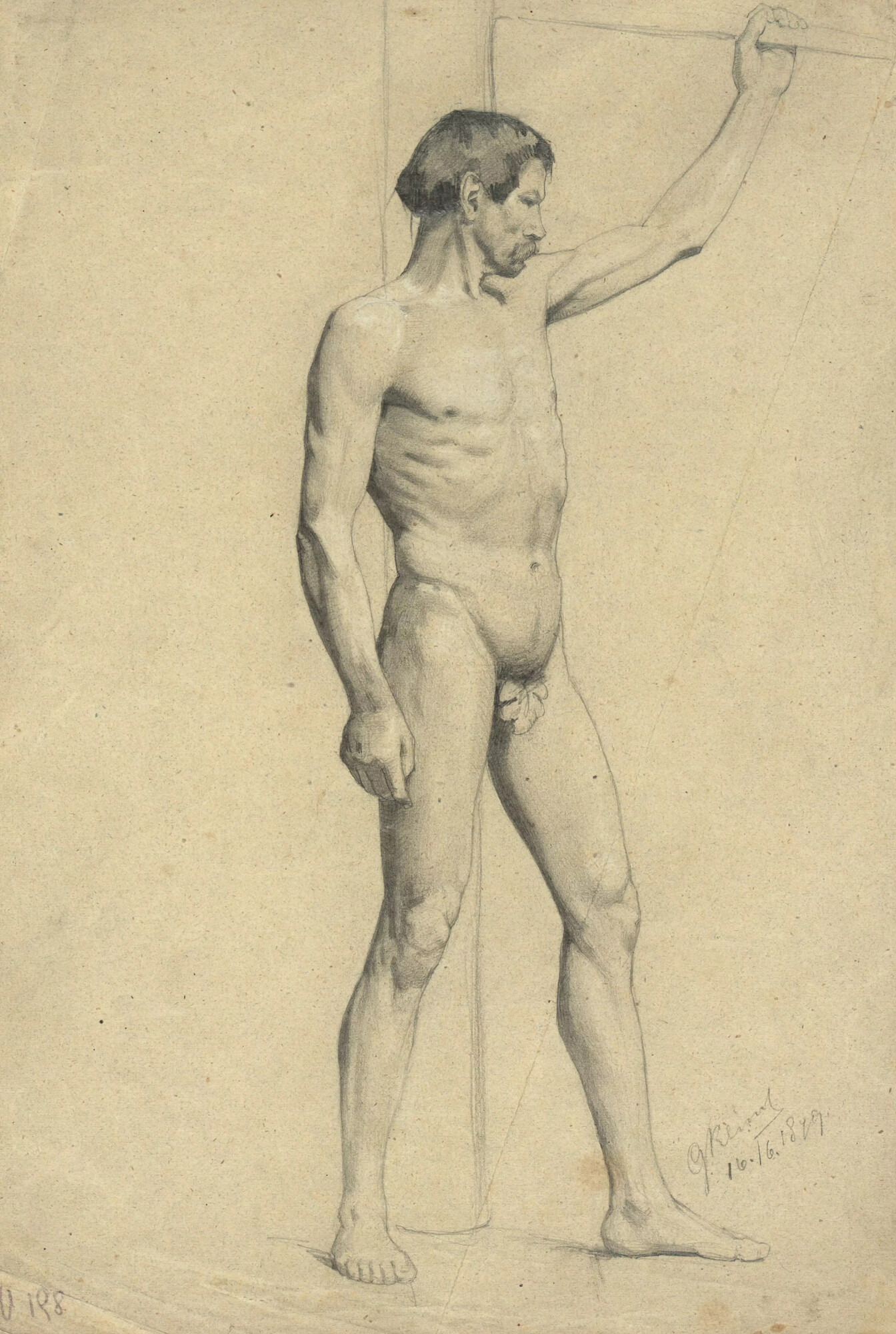

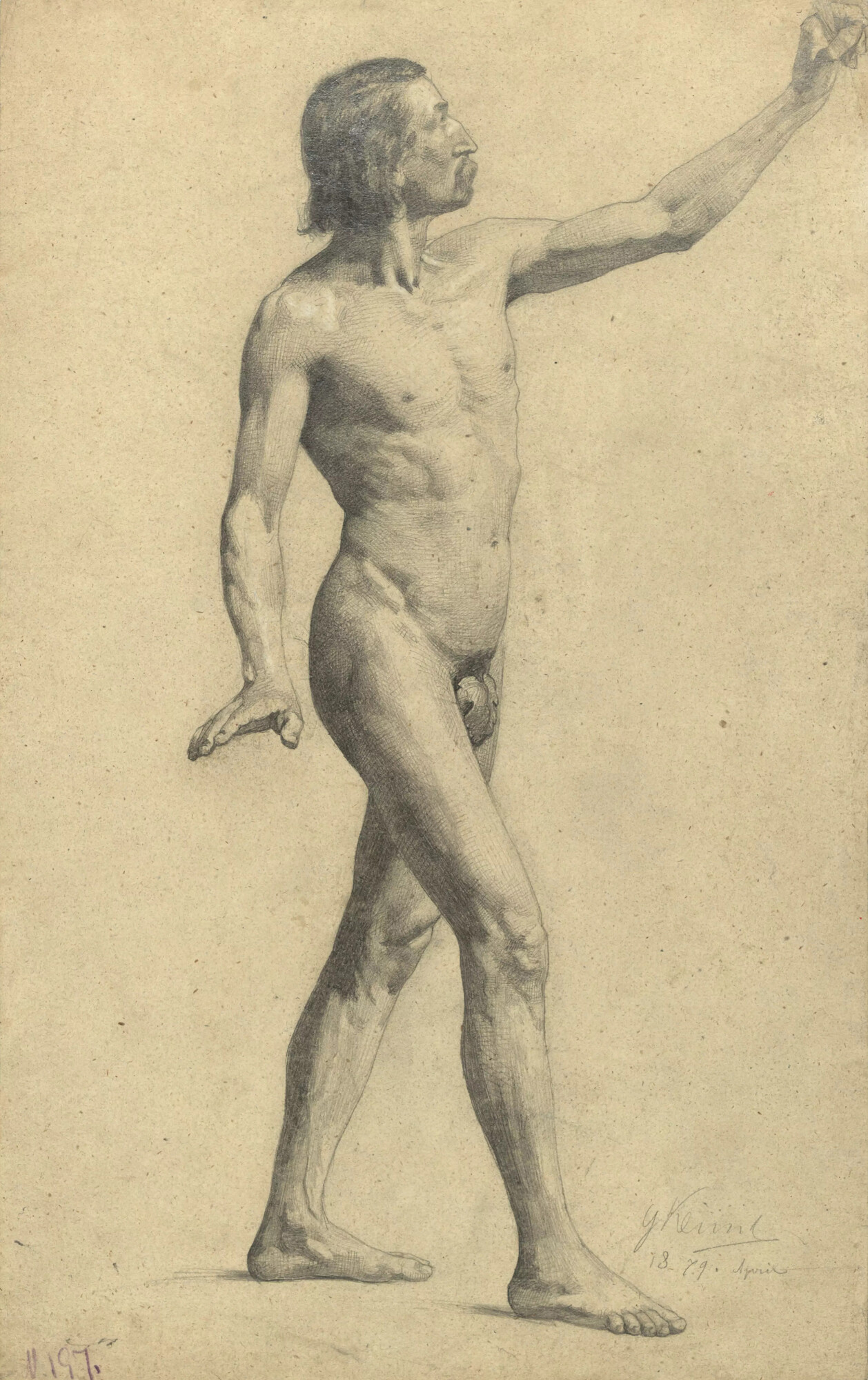

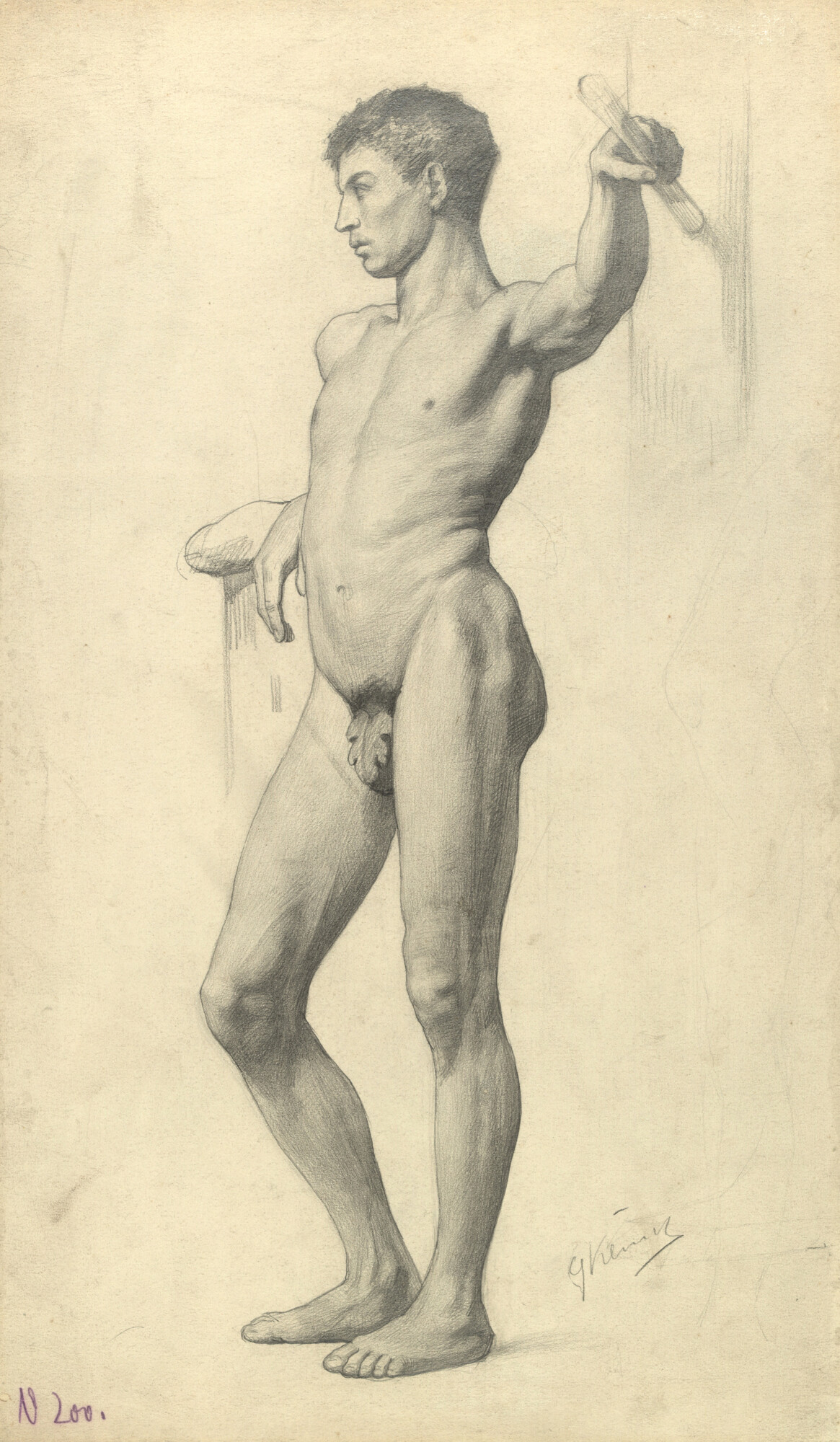

Nude Drawings

The second discipline in which Klimt trained early on was drawing from life. Having switched to the painting and drawing class in 1878/79, he did a large number of drawings of male nudes in diverse poses. They illustrate that during his studies Klimt explored the male anatomy in depth. Particularly impressive in this context are the convincing foreshortening of the limbs and the skillful accentuation of individual groups of muscles through shading. Klimt’s whole focus was on the naturalistic modeling of the human body. Such objects as beams, boxes, or tables mostly merely serve as legitimization for positions of the body, the incidence of light, and perspective and are thus outlined only faintly.

Nude Drawings by Gustav Klimt

-

Gustav Klimt: Seated male nude with hat, 1879-1881, Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Seated male nude with hat, 1879-1881, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum -

Gustav Klimt: Male academy nude in pose, 1879, Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Male academy nude in pose, 1879, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum -

Gustav Klimt: Male academy act in motion, 1879, Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Male academy act in motion, 1879, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum -

Gustav Klimt: Male academy act, 1877-1879, Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Male academy act, 1877-1879, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum -

Gustav Klimt: Male academy nude, back view, 1879, Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Male academy nude, back view, 1879, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum -

Gustav Klimt: Male academy nude with folded arms, 1879, Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Male academy nude with folded arms, 1879, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Mrs. Taglang, 1877, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

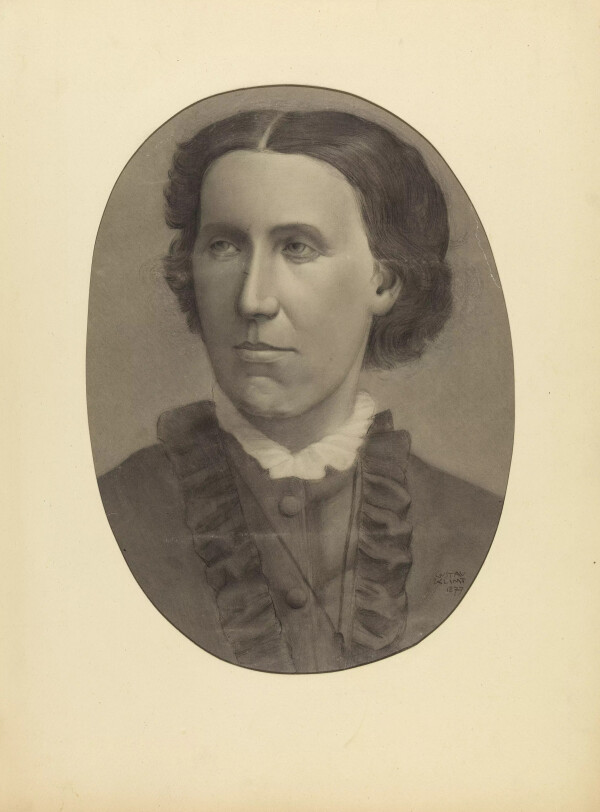

Drawn Portraits

Training at the Imperial-Royal School of Arts and Crafts also comprised portrait drawing. Two surviving drawings of bearded male heads dated to 1879 (private collection, S 1878: 27 and unknown whereabouts, S 1878: 28) were probably made in the context of Klimt’s studies. This assumption is supported by the fact that identical depictions can be found in the work of Franz Matsch, who was Klimt’s classmate. Both drawings stand out for their vibrancy and realistic depiction of the sitters.

Similar portraits have also survived from Klimt’s private surroundings. For example, around 1878/79 he drew his mother (private collection, S 1878: 26) and brother Georg (private collection, S 1878: 29), both of them in a photorealistic manner. In a draft of her brother’s life story, Klimt’s sister Hermine remembered that Gustav and Ernst had drawn portraits from photographs at home even before 1880 – not only for family members but also for paying acquaintances. Selling one drawing earned them around six guilders (about 75 euros). The portrait drawing Frau Taglang (?) (1877, Wien Museum, Vienna, S: -) might be one of these commissioned portraits. The oval format of the drawing and its detailed rendering suggest that it is a portrait based on a photograph. The chalk drawing, roughly 40 centimeters high, shows a woman facing left within a narrow oval. Her face, hair, and clothes are painstakingly captured in a way suggesting volume and executed down to the last detail.

Literature and sources

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band I, 1878–1903, Salzburg 1980.

- Ursula Storch (Hg.): Klimt. Die Sammlung des Wien Museums, Ausst.-Kat., Vienna Museum (Vienna), 16.05.2012–07.10.2012, Vienna 2012.

- Marian Bisanz-Prakken (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Ausst.-Kat., Albertina (Vienna), 14.03.2012–10.06.2012; Getty Center (Los Angeles), 03.07.2012–23.09.2012, Munich 2012.

- Klassenkataloge 1876–1881, .