Klimt's work focuses on all aspects of the Art Nouveau master's oeuvre. Visualized through a timeline, Klimt's creative periods are rolled up here, starting with his training, his collaboration with Franz Matsch and his brother Ernst in the "Künstler-Compagnie", the affair surrounding the faculty paintings and his post-fame and the myth that still surrounds this exceptional artist today.

Expressive Blaze of Colors

Klimt devoted the years leading up to World War I to the working drawings for the Stoclet Frieze. Along with the allegorical paintings Death and Life and The Virgin, the artist primarily created female portraits. Landscapes showing Lake Garda and paintings of Kammer Castle demonstrate that Klimt developed an increasingly painterly style.

→

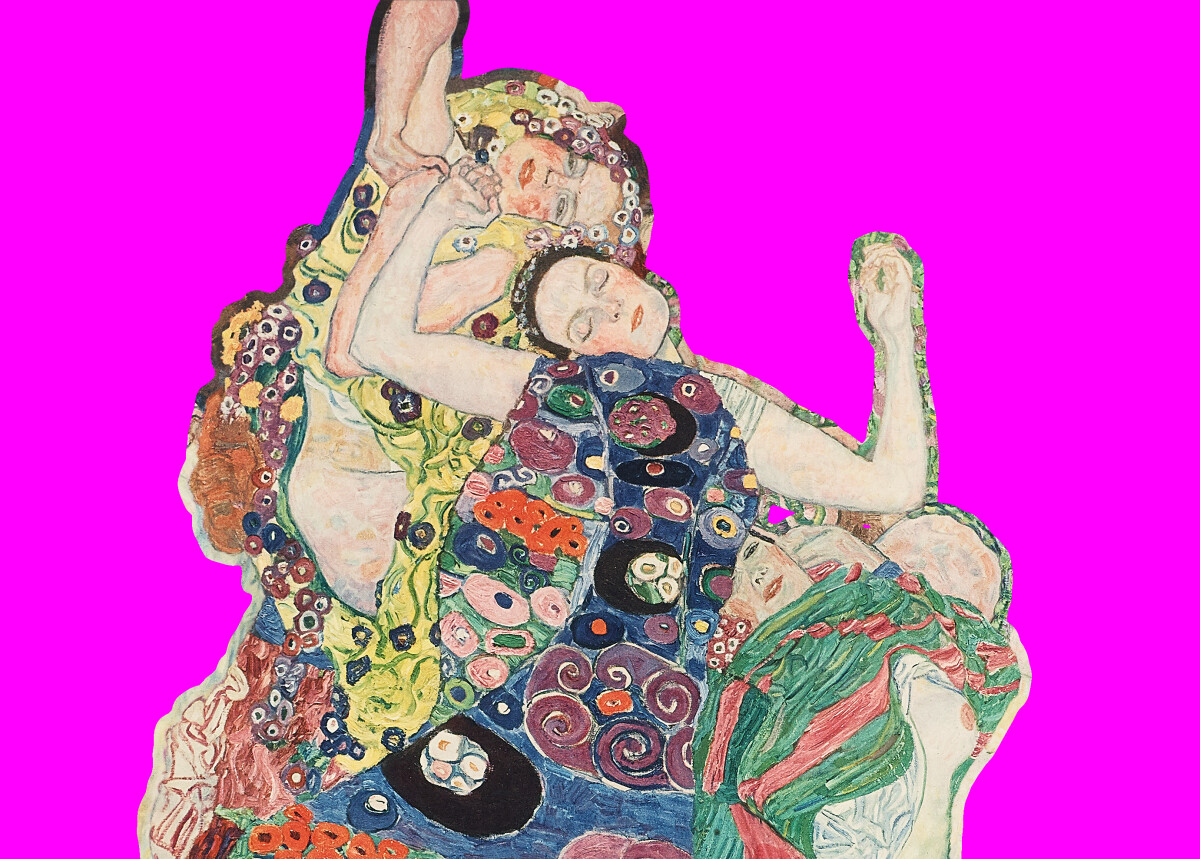

Gustav Klimt: The Virgin, 1913, Národní Galerie

© National Gallery Prague

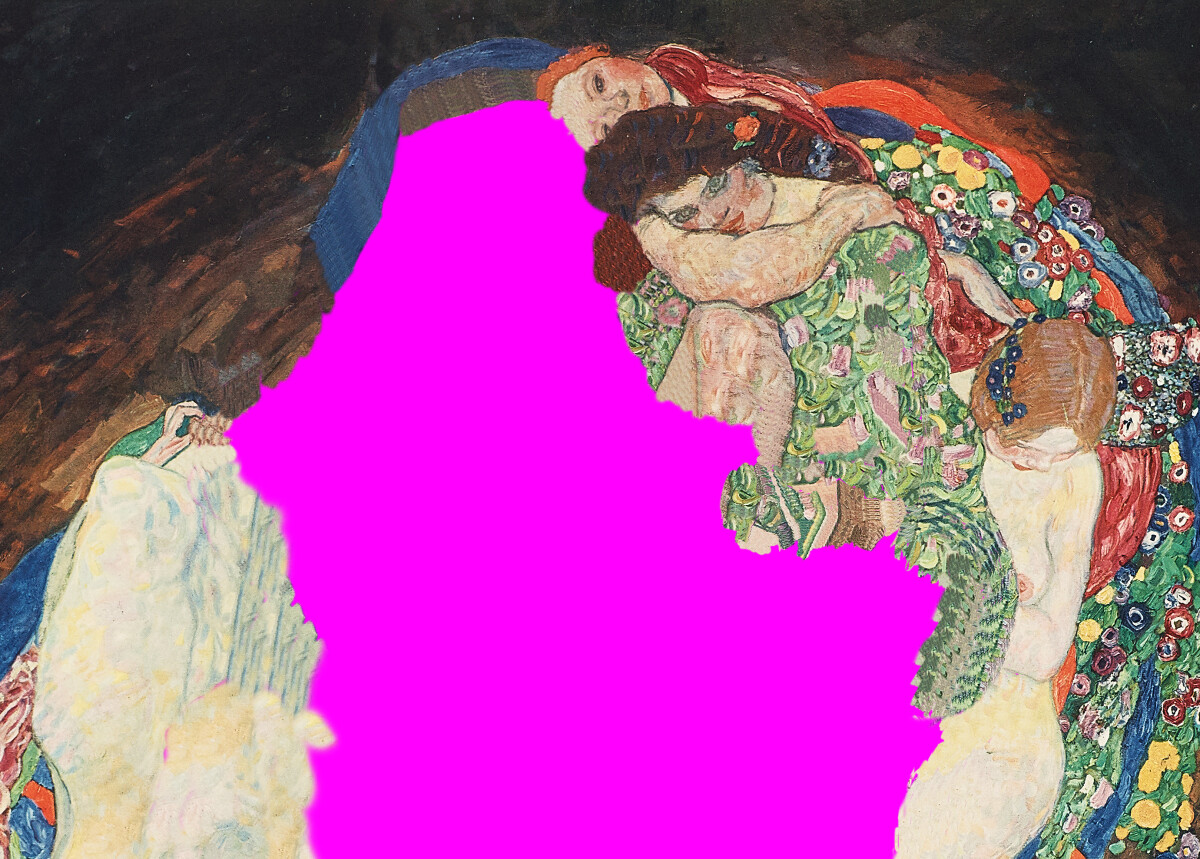

Large-scale Allegories

With his two large-scale allegories Death and Life (Death and Love) and The Virgin, Klimt created his first monumental works after the Golden Period. The works, telling of life, love, and transience, are in line with Klimt’s late style, which is characterized by intense, bright colors and geometrically patterned carpets.

To the chapter

→

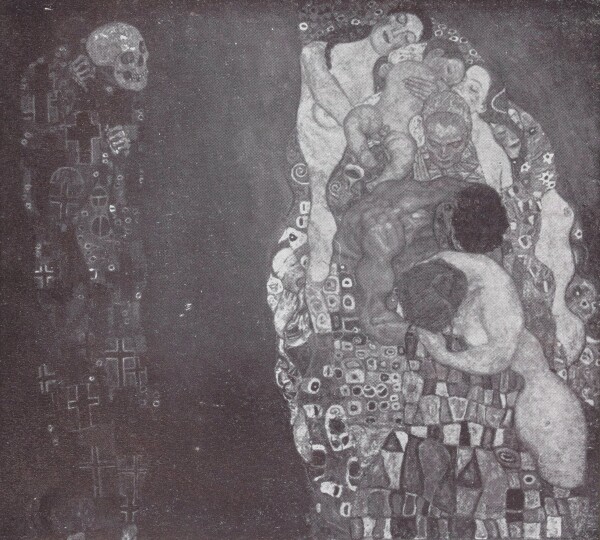

Gustav Klimt: Death and Life (Death and Love), 1910/11 (überarbeitet: 1912/13, 1916/17), Leopold Museum

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

Portrayals of Patronesses

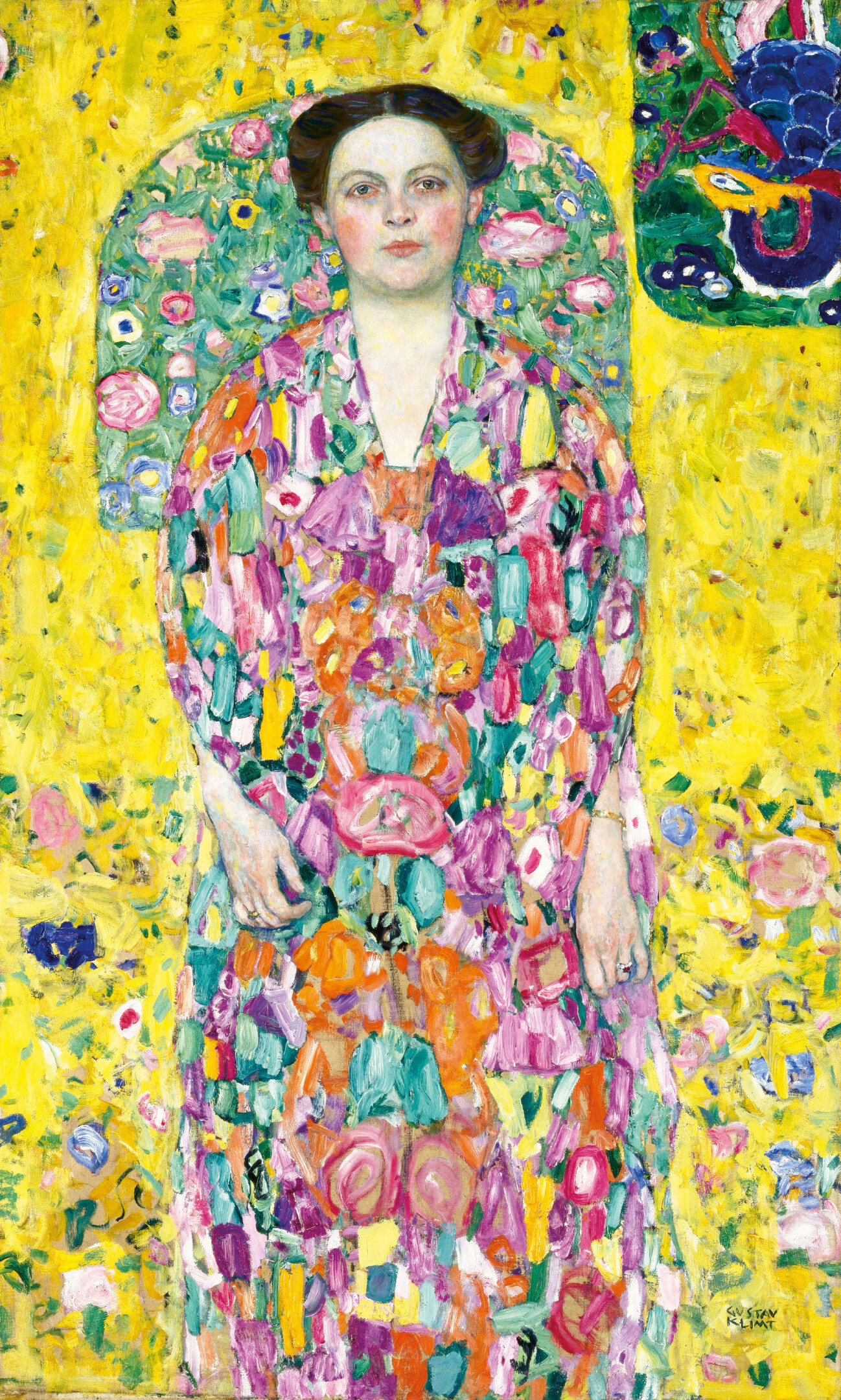

The colorful portraits of Ria Munk, Adele Bloch-Bauer, Paula Zuckerkandl, Mäda Primavesi, and Eugenia Primavesi mark Klimt’s change in style, which paved the way for the final years of his career. Taking his farewell from the Golden Period, he adopted an increasingly open painting style and the use of expressive colors while introducing floral and East Asian motifs in boldly patterned backgrounds.

To the chapter

→

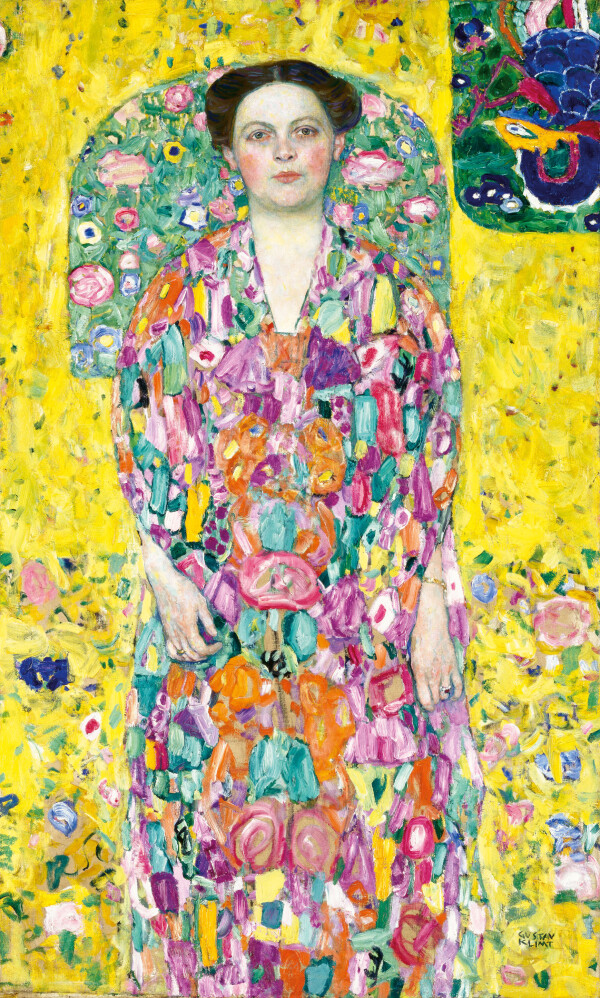

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Eugenia (Mäda) Primavesi, 1913/14, Toyota Municipal Museum of Art

© Toyota Municipal Museum of Art, Toyota

Kammer Castle and Flowering Gardens: A Recurrent Motif

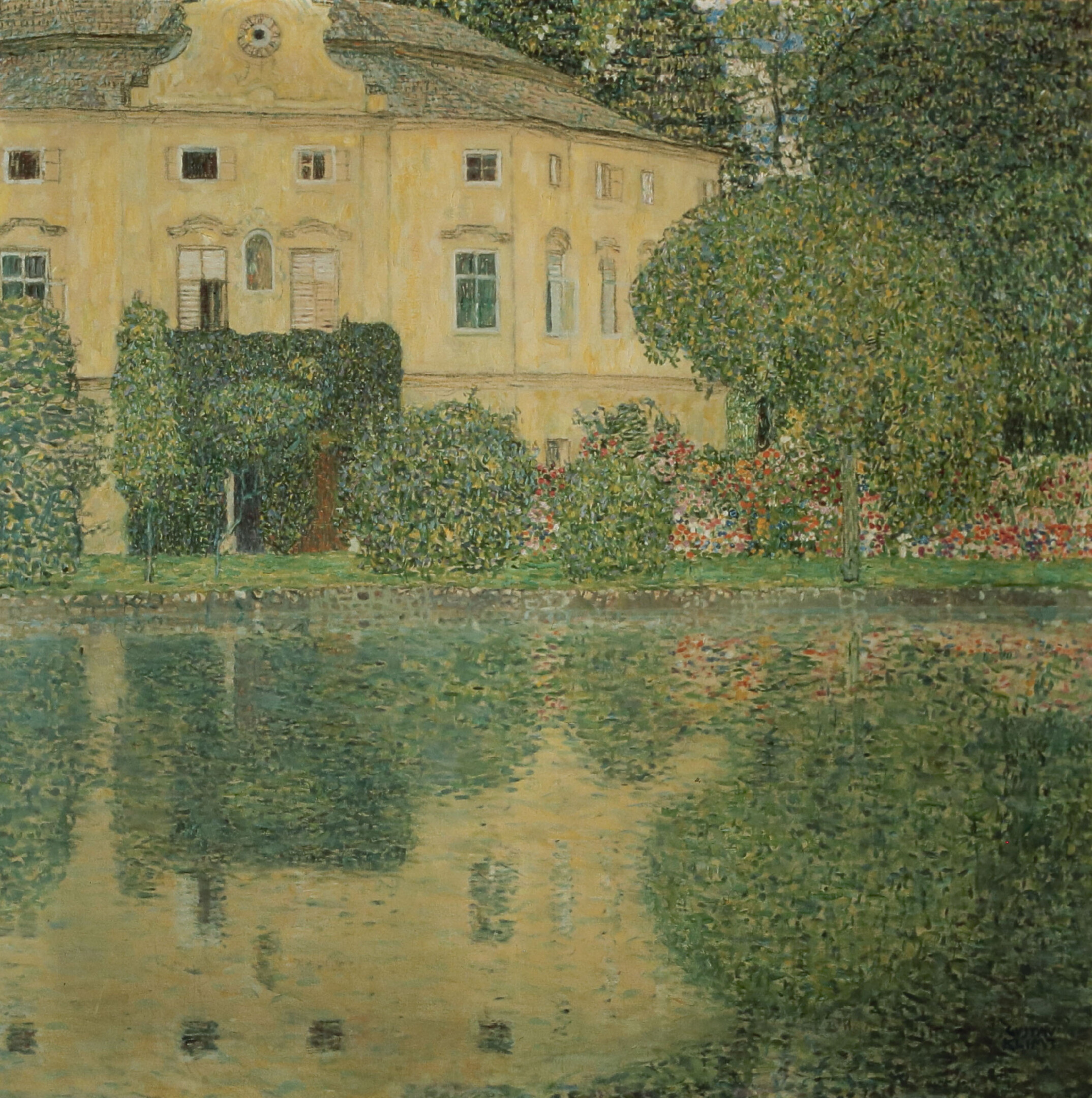

In his landscapes painted from 1910 on, Gustav Klimt once again devoted himself to depictions of Kammer Castle and its immediate surroundings. Moreover, he immortalized the contemplative landscape of the Attersee in a number of paintings.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Kammer Castle on the Attersee IV, 1910, private collection

© Gallery Welz Salzburg

Monuments for Lake Garda

Three landscape paintings bear witness to Klimt’s stay on Lake Garda in the summer of 1913. Two architectural views attest to the continuation of Klimt’s tendency toward two-dimensionality in his art, while in the garden landscape he captured nature in full bloom.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Church in Cassone on Lake Garda, 1913, private collection

© Sotheby's

The Stoclet Frieze. Completion

Designing the Stoclet Frieze, which had been commissioned from him in 1905, was to keep Gustav Klimt busy over many years. It was not until 1910/11 that he made his nine large-sized work drawings, in which he made annotations as to the choice of materials and the execution. The work was finally completed in 1911 by Leopold Forstner’s Mosaic Workshop and installed at the Stoclet Palace in Brussels.

To the chapter

→

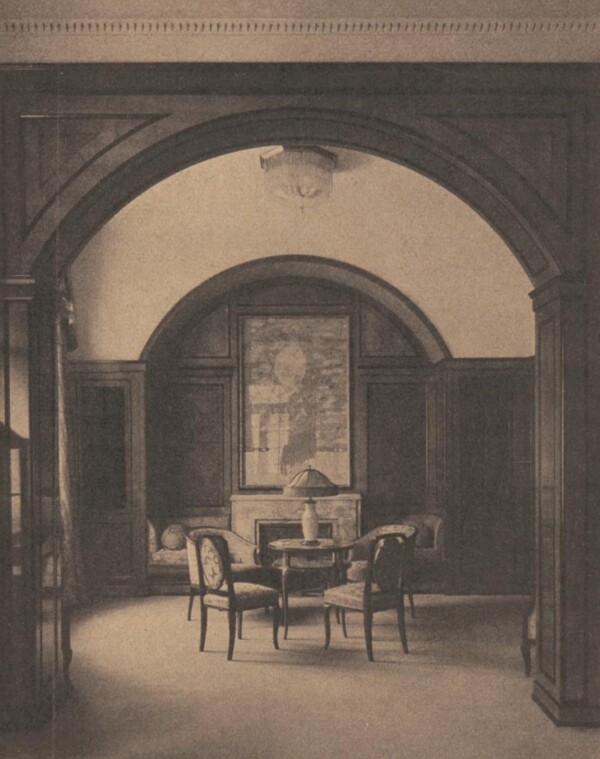

Paula Deetjen: Insight into the Palais Stoclet, 1917/18, Deutsches Dokumentationszentrum für Kunstgeschichte

© Bildarchiv Foto Marburg

Exhibition Activity

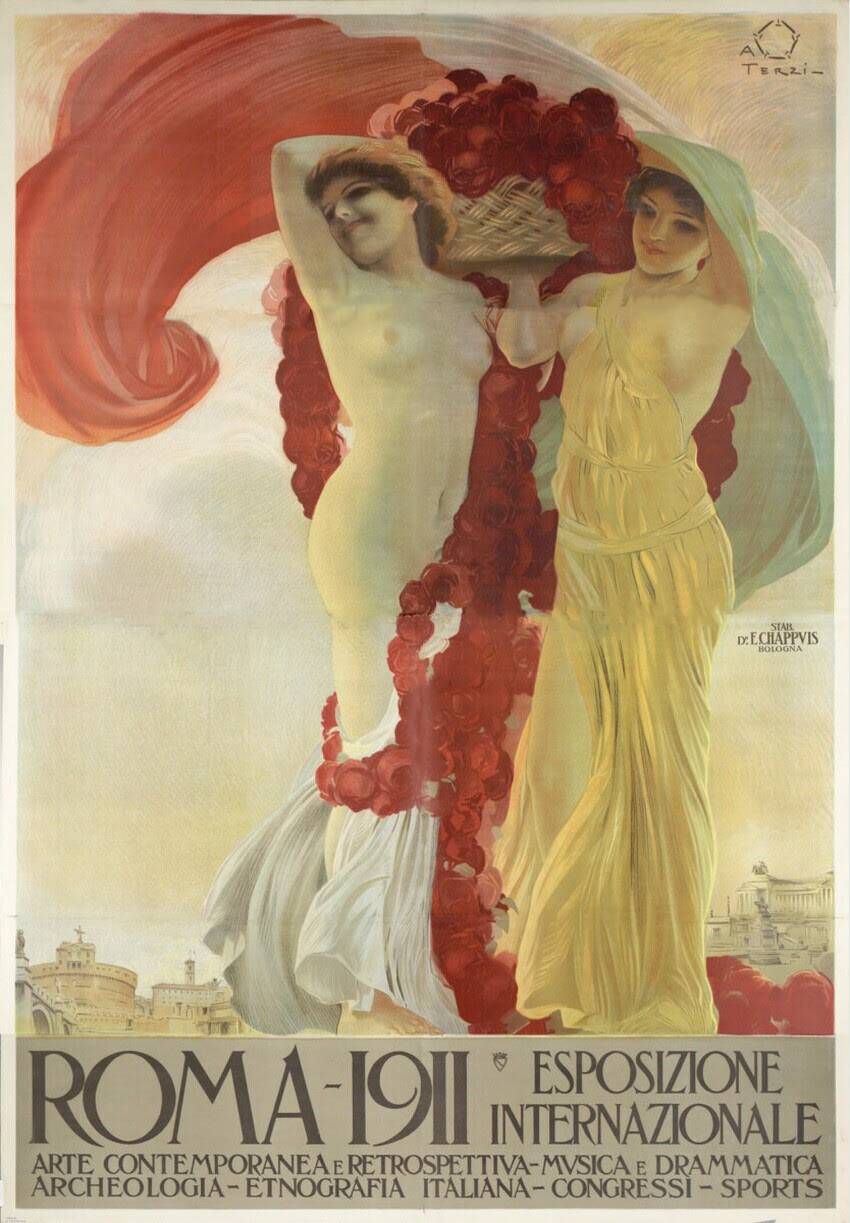

Between 1910 and 1913, Gustav Klimt primarily took part in exhibitions abroad. In Venice, Rome, and Budapest, separate rooms were devoted to the display of the artist’s oeuvre. In Vienna, Klimt’s hometown, his latest works were presented at Galerie Miethke. Toward the end of 1910, Viennese society had a chance to see the panels for the Stoclet Frieze for a brief period at Leopold Forstner’s Vienna Mosaic Workshop.

To the chapter

→

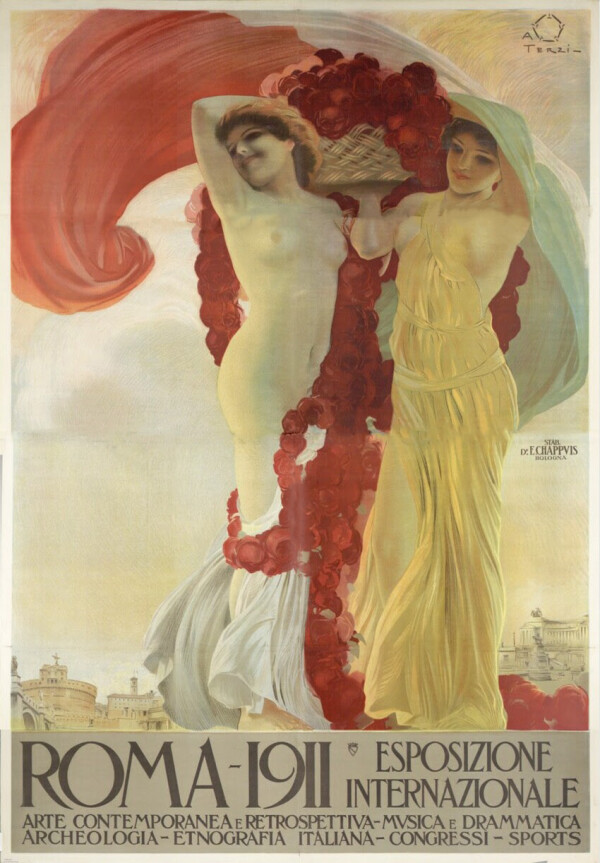

Aleardo Terzi: Poster of the Rome International Art Exhibition, 1911, The Albertina Museum, Vienna

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

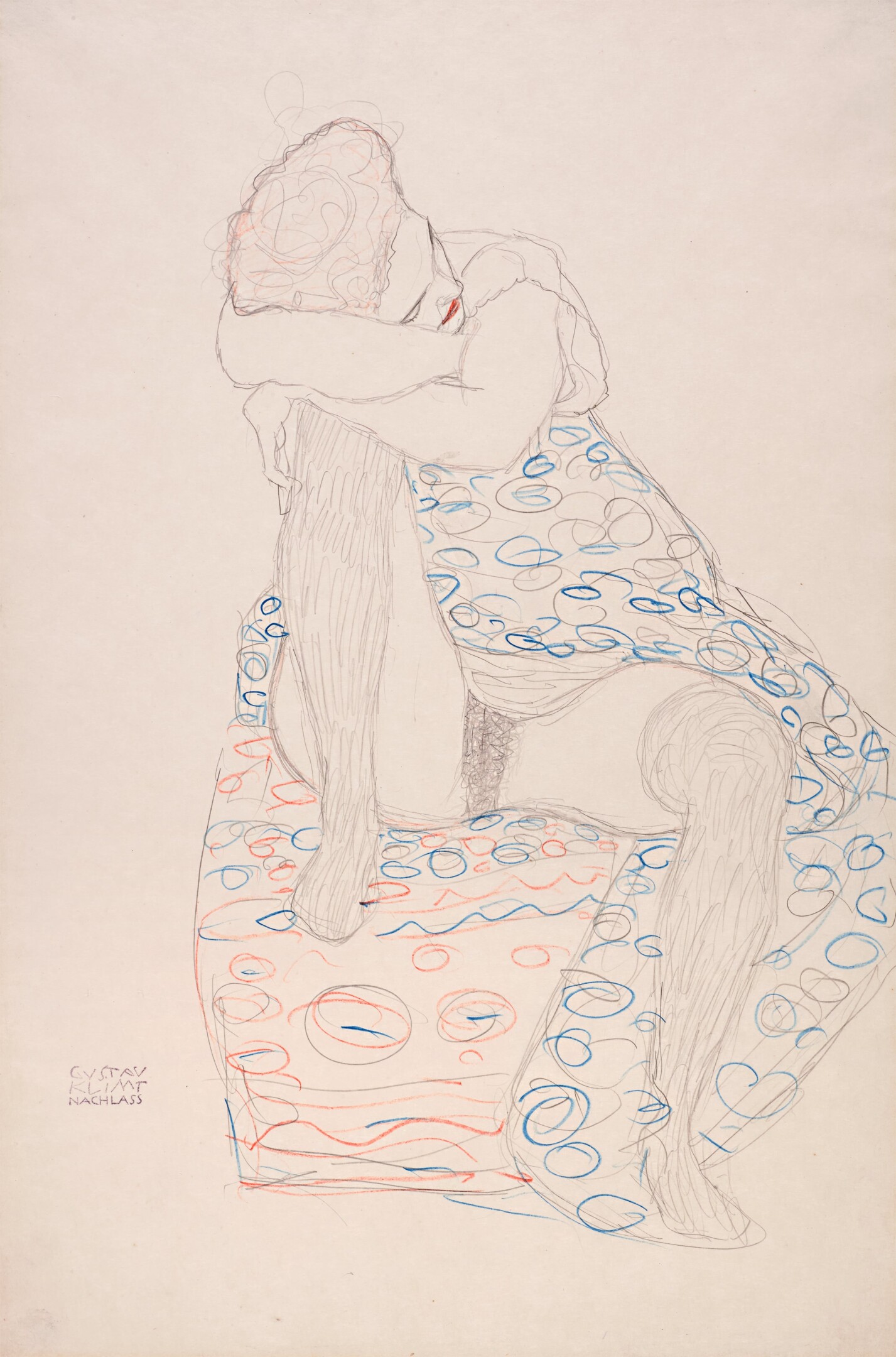

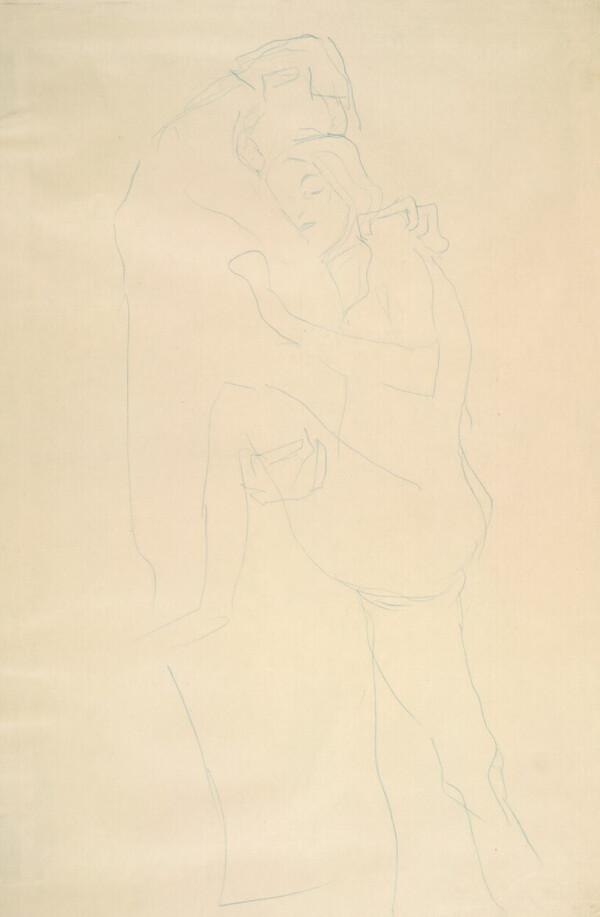

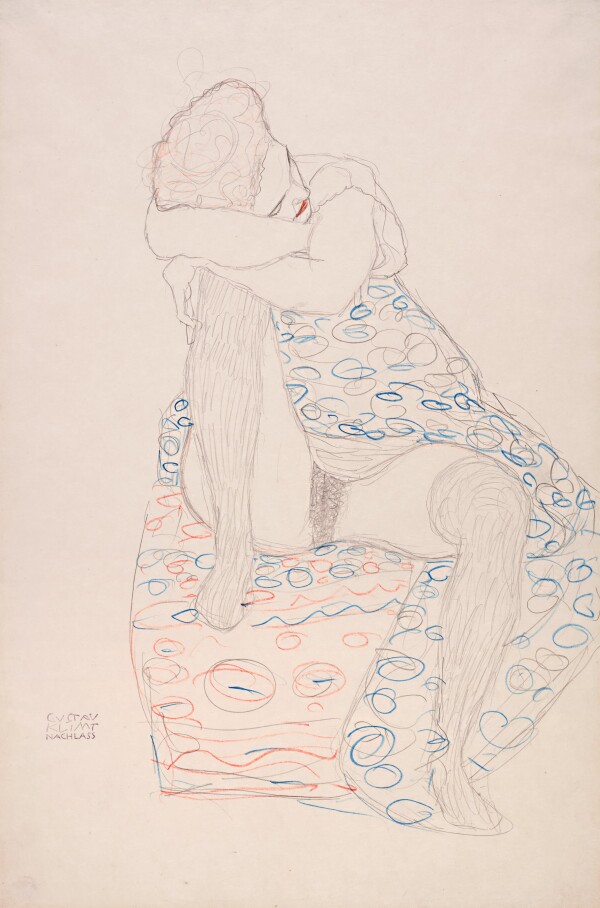

Drawings

In the period from 1910 to 1913, Klimt increasingly sought to capture painterly details in the medium of drawing. While he used an ever more open, pastose style in his paintings, he developed an impressive range of variation in the lines of his drawings.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Sitting half nude supported on the right knee, 1909/10, Leopold Museum

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

Expressive Blaze of Colors

Klimt devoted the years leading up to World War I to the working drawings for the Stoclet Frieze. Along with the allegorical paintings Death and Life and The Virgin, the artist primarily created female portraits. Landscapes showing Lake Garda and paintings of Kammer Castle demonstrate that Klimt developed an increasingly painterly style.

→

Gustav Klimt: The Virgin, 1913, Národní Galerie

© National Gallery Prague

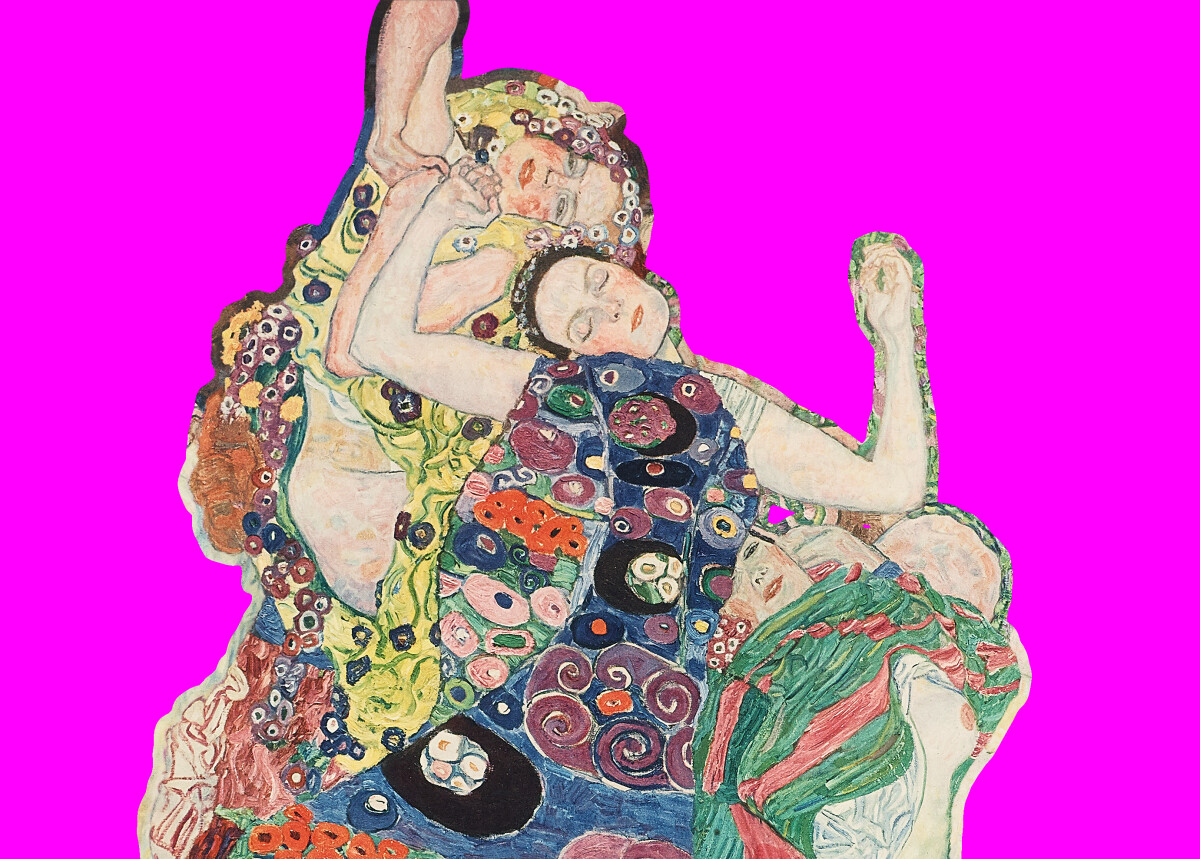

Large-scale Allegories

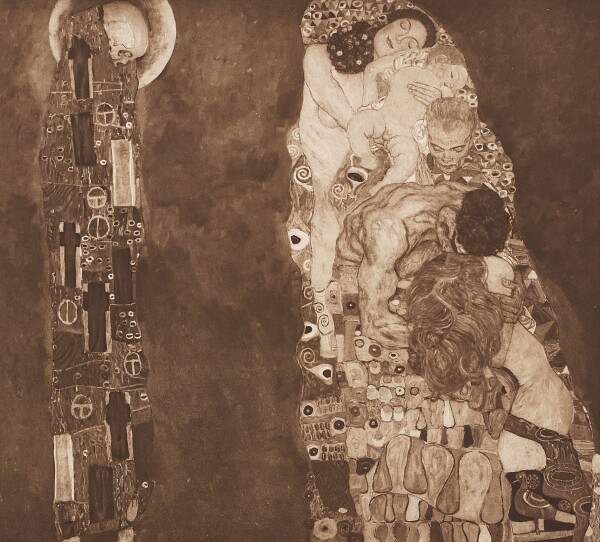

Gustav Klimt: Death and Life (Death and Love), 1910/11 (überarbeitet: 1912/13, 1916/17), Leopold Museum, in: Kunstverlag Hugo Heller (Hg.): Das Werk von Gustav Klimt, Vienna - Leipzig 1918.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

With the two large-scale allegories Death and Life (Death and Love) and The Virgin, Klimt created his first monumental works after the Golden Period. The works, telling of life, love, and transience, are in line with Klimt’s late style, which is characterized by intense, bright colors and geometrically patterned carpets.

“I delved into these images in Rome … Bohemia – ‘Life,’ ‘The Virgin,’ … looking at them, you can think what you like.”

Measuring 180 by 200 centimeters, Death and Life (Death and Love) (1910/11, reworked in 1912/13 and in 1916/17, Leopold Museum, Vienna) is Gustav Klimt’s second largest surviving painting. Pursuing a pictorial concept the artist had already explored beginning in 1903 with his paintings Hope I (1903/04, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa) and Hope II (Vision) (1907/08, The Museum of Modern Art, New York), the painting deals with the themes of birth, life, and death. Compositionally, the depiction is split into two halves. On the right, human beings piled up, a motif Klimt had increasingly used in his Faculty Paintings, represent the aspect of life in the form various closely interlaced age groups. They are faced with the figure of Death on the left, rendered as a cowled skeleton. Klimt had chosen this iconography earlier for the personification of Death in the two Hope paintings, although in the case of Death and Life (Death and Love) he expanded it to include Christian symbols of crucifixes and a halo.

The color scheme seems surprising, as at the same time Klimt was still working on the designs for the Stoclet Frieze (MAK – Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna). Large amounts of gold leaf, which over the years had lent its name to Klimt’s Golden Period, gave way to a bright palette in 1910. In Death and Life (Death and Love), Klimt employed the colors according to their symbolic meaning. He used the cold, dark colors of blue, violet, and green, supplemented by black and white, to paint the Grim Reaper’s robe, interspersed with a multitude of crosses. By contrast, he chose warm colors, mostly shades of red, pink, and orange, for the side of Love and Life. The only exception is the garment of the aged woman, who, having arrived at the end of life, is already assigned to the sphere of Death in terms of color.

Later Revisions – From Life to Love

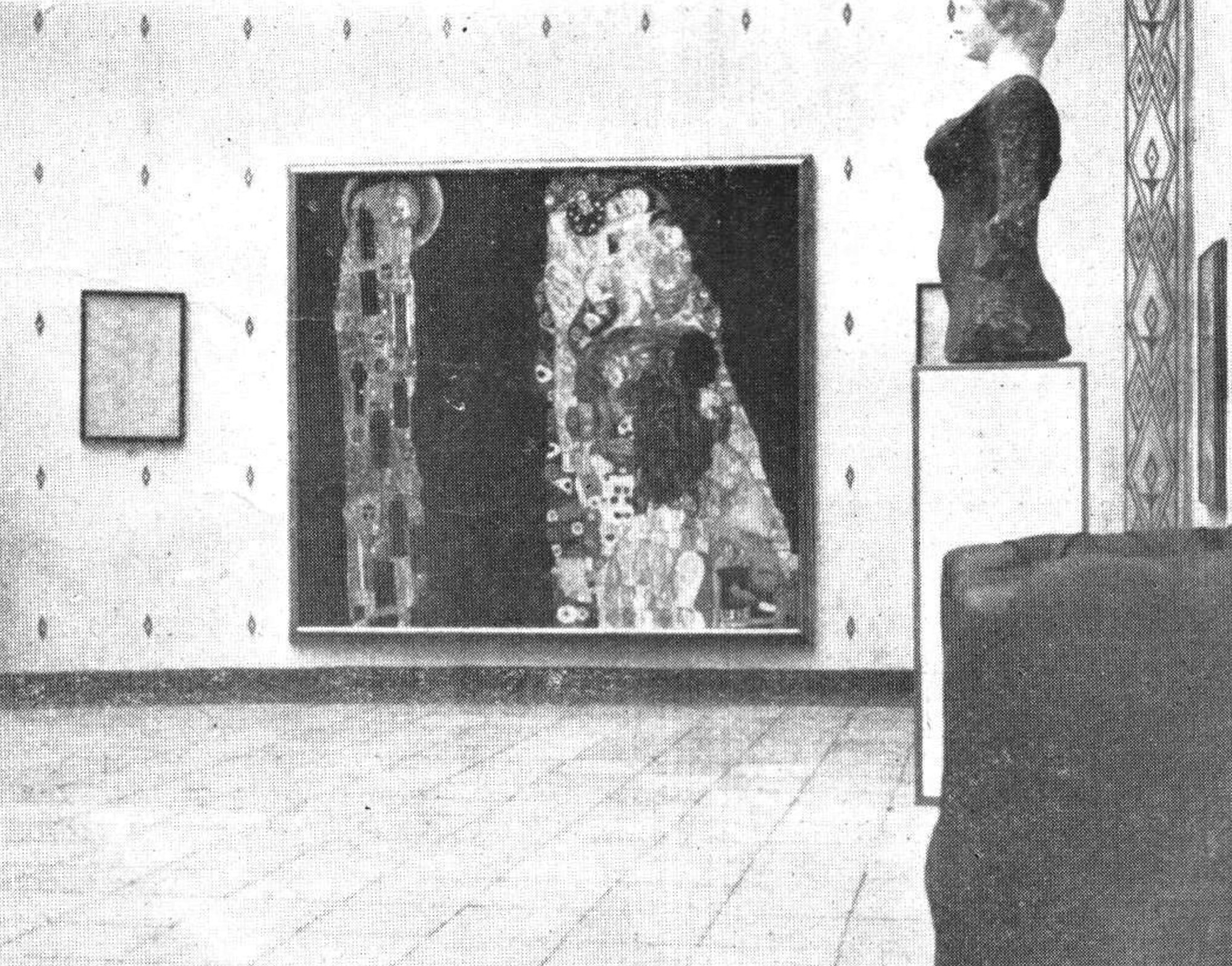

The genesis of the work is characterized by multiple and sometimes large-scale revisions. The first version of the composition is documented by a black-and-white reproduction in the fourth delivery for the Miethke Portfolio, as well as a photograph by Moriz Nähr and exhibition views of the “International Art Exhibition of Rome” in 1911 and the “Great Dresden Art Exhibition” of 1912. A color version of the first state was also published in the fall issue of Kunst für alle in 1913.

Insight into the International Art Exhibition in Rome, March 1911 - December 1911

© ANNO | Austrian National Library

Latest research findings suggest that a first reworking of the painting took place as early as 1912/13. Klimt could have begun work after the end of the “Dresden Art Exhibition” in mid-October 1912 at the latest. On 4 March 1913, the reworking process seems to have been in full swing, when Klimt wrote to Emilie Flöge:

“Hassling fearlessly with the dead.”

Klimt obviously wished to finish the second version before the opening of a planned exhibition in Budapest on 8 March. Unfortunately, there is no photographic evidence of the condition in which the painting was shown there. With the alterations made, the name of the work changed as well. Whereas it had previously been exhibited under the title of “Death and Life,” from 1913 on it was referred to as “Death and Love.” The new title indicates that the changes were not only made for aesthetic and compositional reasons, but they also point to the artist’s new objective in terms of content.

Gustav Klimt: Death and Life (Death and Love), 1910/11 (überarbeitet: 1912/13, 1916/17), Leopold Museum, in: Berliner Secession (Hg.): Wiener Kunstschau in der Berliner Secession Kurfürstendamm 232, Ausst.-Kat., Exhibition house on Kurfürstendamm (Berlin), 08.01.1916–20.02.1916, Berlin 1916.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

The next visual documentation of an intermediate state cannot be found until 1916, in the catalog of the “Vienna Kunstschau at the Berliner Secession.” While the exhibition was still on, Schiele wrote that Klimt’s painting had been “completely repainted.” Whether this was the version of 1913 or the result of another revision cannot be said with certainty. Yet the black and white illustration shows far-reaching changes in the work. Above all, the painter fundamentally reworked the figure of Death. While in the first version he still passively lowered his head, which was surmounted by a halo, in 1916 he swings his club and menacingly raises his skull, contorted into a grimace, to the group of humans. In the part of the living, Klimt added more figures to the left and right. The group thus changed from a conical to a more oval shape. He also shortened the hair of the young woman in the arms of the man. In both groups of figures, he also changed the patterning of the robes.

Gustav Klimt: Death and Life (Death and Love), 1910/11 (überarbeitet: 1912/13, 1916/17), Leopold Museum

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

After the exhibition, Klimt was to rework the painting again. In the final version, a girl was added at the upper left corner. This figure, strongly reminiscent of the woman on the left in the painting Friends II (1916/17, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945), is enclosed by a rose bush that formally recalls the roses in The Stoclet Frieze (1905–1911, private collection). With this addition, Klimt completed the oval shape of the crowd of humans begun earlier. Photographs of the “Austrian Art Exhibition” in Stockholm prove that the work had finally been completed by September 1917.

The price of the monumental work, which was repeatedly put up for sale, was about 26,000 crowns (approx. 160,000 euros). The work found a buyer in Hans Böhler presumably even before the exhibition in Stockholm.

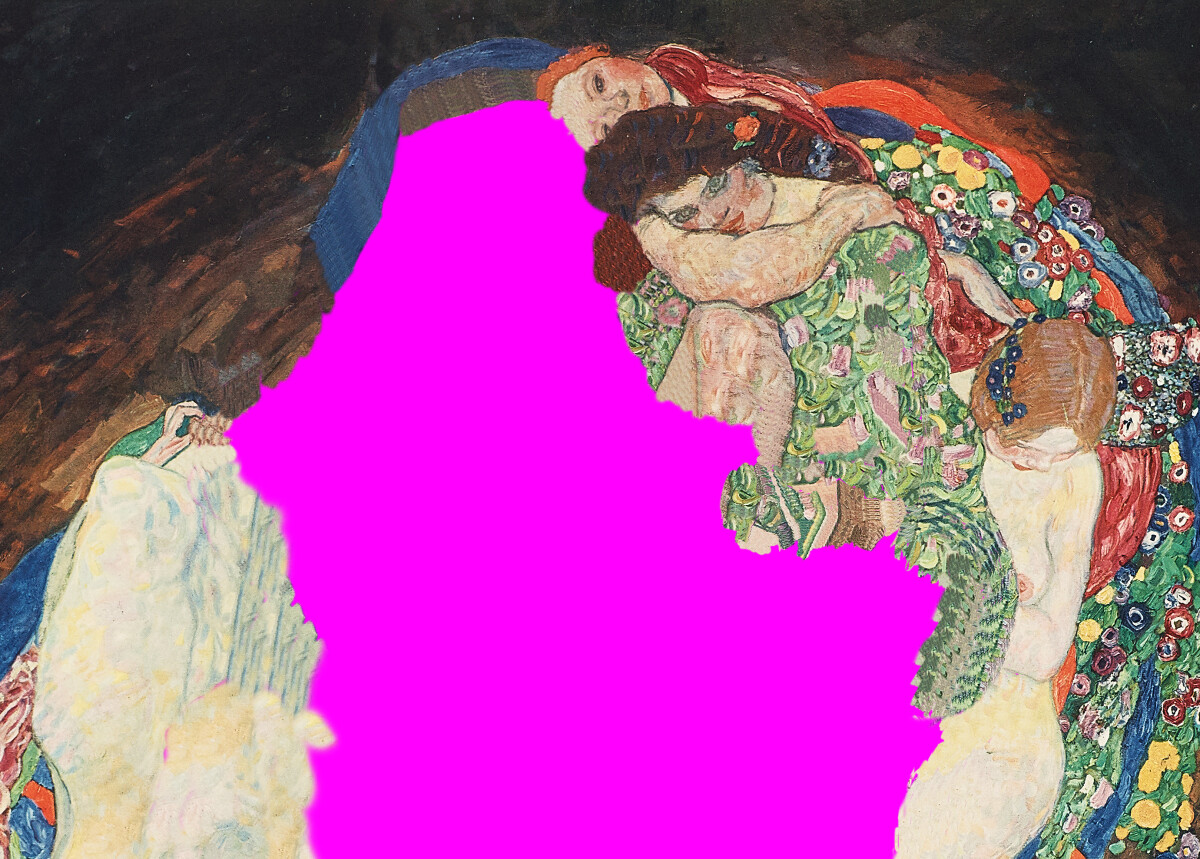

Gustav Klimt: The Virgin, 1913, Národní Galerie

© National Gallery Prague

“And then the Virgin amidst a fantastic fairyland of flowers”

While working on Portrait of Mäda Primavesi (1913, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) and the second version of Death and Life (Death and Love), Gustav Klimt also tackled the crowded allegory The Virgin (1913, National Gallery, Prague). Together with Death and Life (Death and Love) and the unfinished work The Bride (1917/18, Klimt-Foundation, Vienna), The Virgin forms a trio of major figural works from Klimt’s late period. Thematically, they bring together those aspects that had determined the painter’s work for almost two decades: life and death, as well as the image of the woman around 1900.

Painting The Virgin, Gustav Klimt finally embraced the expressive colorfulness of the Fauvists, without, however, abandoning his characteristic ornamental carpets. For his composition, Gustav Klimt placed a total of seven women on brightly patterned sheets, keeping the background in contrasting dark colors. Such a contrasting approach with regard to group of figures and background can already be observed in the works Hope II (Vision) and Death and Life (Death and Love) and was then to be continued in The Bride.

The eponymous Virgin likely refers to the central female figure. As in Death and Life (Death and Love), the figures and fabrics are inscribed in an oval. The arrangement of the bodies in a circle and the round shapes in the garments seem to set the composition into a pulsating, rotating motion.

On closer inspection, the human bodies come together to resemble the shape of a female vulva. The heads, accumulating in the upper third of the picture, come together to form a clitoris-shaped bud, while the back views of nudes, apparently representing the labia, enclose the protagonist’s blue robe, which likely stands for the inner labia. Klimt, who had already captured the female sex in numerous erotic drawings, circumvented censorship by employing this subtle suggestion. While his studies for the composition all clearly show the female pubic region, in the painting he covered it with colorful cloths. An exception is the crouching brunette woman on the right above the Virgin. When taking a closer look, one can identify a brown triangle underneath the elbow of the central figure that turns out to be the crouching woman’s pubic hair. Klimt could only risk such an explicit display of the female sex by disguising it through a myriad of ornaments. A Munich art critic aptly recognized that Klimt knew how to hide his pictorial content wisely:

“As to the intricate symbolism, the eroticism, Klimt’s preference for hiding, concealing, and overlapping his essentially brilliantly and masterfully drawn figures so that one must look for them and interpret them as if they were picture puzzles, one may indeed beg to differ.”

The sleeping Virgin is thus surrounded by a phantasmagorical fabric that seems to refer to her slumbering sexuality and at the same time can be understood as an erotic dream: a subject Klimt had already referred to in his Danaë (1907/08, private collection). Contemporaries dismissed the painting as a pleasing “color puzzle,” while the allusion to female sexuality largely remained uncommented, in spite of the title of the work:

“Klimt is one of those masters solving riddles in one picture while instantly posing color puzzles in another. What seems infinitely complicated for us is essentially simple for him. And how he evades all coloristic eccentricities to create a wondrous whole! The ‘Virgin’ is such a color puzzle.”

The painting was first exhibited in early March 1913, at the Budapest Künstlerhaus. The purchase price was the same as that for Death and Life (Death and Love). Offered for 25,000 guilders each (approx. 153,700 euros), the two pictures were among the most expensive works in the entire exhibition.

After that, the painting was presented in Munich and subsequently, in 1914, in Prague, where it was purchased by the Modern Gallery (today National Gallery, Prague) – which had previously sought to purchase the painting The Kiss (Lovers) (1908/09, Belvedere, Vienna).

Literature and sources

- Jane Kallir: Akte, in: Agnes Husslein-Arco, Jane Kallir, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Klimt, Schiele, Kokoschka und die Frauen, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna), 22.10.2015–28.02.2016, Munich 2015, S. 172-179.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band II, 1904–1912, Salzburg 1982.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012.

- Alfred Weidinger, Michaela Seiser, Eva Winkler: Kommentiertes Gesamtverzeichnis des malerischen Werks, in: Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007, S. 232-313.

- Franz Smola: Tod und Leben, 1910/11, umgearbeitet 1915/16, in: Tobias G. Natter, Elisabeth Leopold (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Sammlung im Leopold Museum, Vienna 2013, S. 216-217.

- Ansichtskarte von Gustav Klimt in Wien an Emilie Flöge in Paris, 2. Karte (Morgen) (03/04/1913). Autogr. 959/47-8, .

- Brief mit Kuvert von Egon Schiele in Wien an Anton Peschka in Wieselburg an der Erlauf (10/03/1916). LM 4503.

- N. N.: Ein Besuch bei Gustav Klimt, in: Neues Wiener Journal, 11.02.1913, S. 4-5.

- Akt betreffend den Ankauf von Kunstwerken für die Moderne Galerie durch das k. k. Ministerium für Kultus und Unterricht (16.07.1908). AT-OeStA/AVA Unterricht UM allg. Akten 3446, Zl.32.554/1908 fol. 1+2, .

- F. v. O.: XI. Internationale Kunstausstellung im Glaspalast. Oesterreich-Ungarn, in: Münchner neueste Nachrichten: Wirtschaftsblatt, alpine und Sport-Zeitung, Theater- und Kunst-Chronik (Morgenausgabe), 12.08.1913, S. 1-2.

Portrayals of Patronesses

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Ria Munk on Her Deathbed, 1912, private collection

© Courtesy Richard Nagy Ltd., London

The colorful portraits of Ria Munk, Adele Bloch-Bauer, Paula Zuckerkandl, Mäda Primavesi, and Eugenia Primavesi mark Klimt’s change in style, which paved the way for the final years of his career. Taking his farewell from the Golden Period, he adopted an increasingly open painting style and the use of expressive colors while introducing floral and East Asian motifs in boldly patterned backgrounds.

In October 1909 Gustav Klimt traveled to France and Spain in the company of Carl Moll. There he encountered the painting styles of the Impressionists, Fauvists, and Spaniards like El Greco, all of which had a stimulating impact on him. By 1910 at the latest he was also intensively preoccupied with the “painterly” approach to his brushwork and color palette. His style seemed more liberated, with gold leaf disappearing in favor of the now-dominant use of bright, expressive colors. From then on, floral and East Asian motifs would dominate garments and backgrounds. Klimt’s portraits of women – Ria Munk, Adele Bloch-Bauer, Paula Zuckerkandl, Eugenia Primavesi, and the latter’s daughter Mäda – marked a change in style in Klimt’s work from 1912 onward that would also determine the works of his last phase.

Maria “Ria” Munk

Originally from Hungary, Aranka Munk was the daughter of the landowner Simon Pulitzer. She married the industrialist Kommerzialrat Alexander Munk in 1882. Her three sisters Irma, Eugenie – called “Jenny” – and Serena married into the wealthy Politzer, Steiner, and Lederer families, with the Lederers owning one of the most important collections of Klimt’s works. Gustav Klimt immortalized the influential Alexander Munk and his wife as early as the late 1880s in his Auditorium of the Old Burgtheater (1888/89, Wien Museum, Vienna), in which he incorporated portraits of numerous personalities of Vienna’s high society. On 28 December 1911, Aranka and Alexander Munk’s daughter Maria, called “Ria,” committed suicide at the young age of 24. The Neues Wiener Journal wrote about the incident:

“[…] Marie M., daughter of Kommerzialrat Alexander M., killed herself yesterday noon in her apartment at Sternwartestraße 52 in Vienna’s 18th District by shooting a bullet from a 5-millimeter caliber revolver through the left side of her chest.”

Arthur Schnitzler also mentioned in his diary “the suicide of Miss Munk because of H. H. Ewers.” The tragic event was probably due to the fact that the writer Hanns Heinz Ewers had broken off his engagement with Ria Munk. Her parents then commissioned portraits of their deceased daughter from Gustav Klimt, to whom they had probably been introduced by Serena and August Lederer. The first posthumous Portrait of Ria Munk on Her Deathbed (1912, private collection) was painted in 1912. The work must have proved laborious and difficult for Klimt. He wrote to Emilie Flöge in June 1912:

“Put off Frau M. with her daughter’s portrait until fall and glad about it.”

Klimt painted the dead woman with her eyes closed and her mouth slightly open, placing her on a white pillow. Her flowing hair and roses surround her pale face. The portrait is reminiscent of John Everett Millais’s painting Ophelia (1851/52, Tate Britain, London). Klimt worked with open, paint-laden brushstrokes. The work is characterized by the contrasting effect of the vibrant hues of the light-colored cushion and face, the deep red to pale pink flowers, and the dark blue background.

A year later, Klimt went about working on another painting for the Munk couple – presumably the portrait The Dancer (Ria Munk?) (c. 1916/17, private collection), which he reworked later on. Frustrated, he wrote to Emilie Flöge in February 1913, when she sojourned in Paris:

“The Munk portrait is becoming a sore, painful spot – can’t do it! It won’t resemble her! Yes, and you will have to listen to my lamentations, although I will contain myself as much as I can.”

A third portrait of the deceased daughter was begun in 1917. Portrait of a Lady (Ria Munk?) (1917, unfinished, The Lewis Collection), however, remained unfinished and only came into the possession of Aranka Munk after Gustav Klimt’s death in 1918.

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II, 1912, private collection

© APA-PictureDesk

Adele Bloch-Bauer II

The members of the wealthy Bloch-Bauer family were among Gustav Klimt’s most important patrons. Adele Bloch-Bauer came from a family of bankers and married the wealthy sugar manufacturer Ferdinand Bloch. The Bloch-Bauer couple used their social standing to establish a salon that would become a meeting place of Vienna’s intellectual and artistic elite. Gustav Klimt too belonged to their circle of acquaintances, and they commissioned him as early as 1903 to paint Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907, New Gallery New York), which Klimt completed in 1907. This painting is considered an icon of the artist’s Golden Period.

Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II (1912, private collection) illustrates the change in style in Klimt’s female portraits. Even in the preliminary drawings, Klimt gave the sitter an immense presence. In the course of the portrait sessions, Bloch-Bauer presented herself in a variety of dresses, which Klimt visualized in his studies through clear lines and adumbrated ornamentation. In the surviving sketches, Klimt exclusively depicted her in an upright standing position, which would almost completely replace the seated position in Klimt’s portraiture from 1912 onward.

In the executed work, Adele Bloch-Bauer is shown standing frontally in the center of the picture. The floor-length dress and the scarf spread over her shoulders obscure the contrast between figure and background. The sitter is only set off by her broad-brimmed black hat trimmed with feathers, as the figure seems to float almost weightlessly against the colored backdrop. Klimt divided the background into geometrically structured zones, which he defined in the form of brightly colored and boldly patterned areas. The floor is designed as a carpet of flowers, while the upper zone shows a figurative scene with Asian warriors on horseback, bringing a primitive exoticism to the work. Klimt was preoccupied with Far Eastern aesthetics for many years and owned a collection of Asian art objects, which he used as a source of inspiration especially for his later works.

Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II was exhibited in June 1913 at the “XI. Internationale Kunstausstellung” [“11th International Art Exhibition”] at the Royal Glass Palace in Munich together with six other paintings and eleven drawings by Gustav Klimt.

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Paula Zuckerkandl, 1912, Verbleib unbekannt, in: Kunstverlag Hugo Heller (Hg.): Das Werk von Gustav Klimt, Vienna - Leipzig 1918.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Insight into the Villa Zuckerkandl, early 1920s

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Mäda Primavesi, 1913, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Eugenia (Mäda) Primavesi, 1913/14, Toyota Municipal Museum of Art

© Toyota Municipal Museum of Art, Toyota

Paula Zuckerkandl

In fin-de-sciècle Vienna, the Zuckerkandl family belonged to an elite of collectors amongst circles of the Jewish upper middle class. Victor Zuckerkandl, an entrepreneur, was the younger brother of Emil and thus the brother-in-law of Berta Zuckerkandl. In 1903 he acquired the Sanatorium Purkersdorf, a park and spa he had furnished by the Wiener Werkstätte, and which he had expanded to include a modern spa house. Together with his wife, Paula Zuckerkandl, he lived on the grounds of the sanatorium in the so-called “private villa.” The couple belonged to the most important promoters of Viennese Modernism and, from 1908 on, also acquired a number of works by Gustav Klimt, mainly landscapes.

In Portrait of Paula Zuckerkandl (1912, whereabouts unknown), which has only survived as a black-and-white photograph, Klimt arrived at a similar pictorial solution as in Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II, painted at the same time. Several preliminary studies for the portrait have survived, in which Klimt already clearly defined the depiction. In the arrangement of the background he again used boldly patterned color fields. In her elaborately patterned cape, Paula Zuckerkandl forms a unity with the ornamental ground, the transitions almost blending into one another, especially in the area of the upper body. In the Chinese cloud motif of the background Klimt again resorted to Asian elements he readily employed during this period. This eloquent component was probably also intended to allude to the collecting activities of the Zuckerkandls, whose collection of Asian art comprised a similarly decorated plate.

In 1916 the couple went to Berlin, where they moved into the newly built Villa Zuckerkandl in Grunewald. Portrait of Paula Zuckerkandl was impressively installed in the living room above the fireplace, in a specially paneled wall niche. A view into the villa was documented in a reproduction published by Hermann Muthesius in 1922. Victor and Paula Zuckerkandl both died in 1927, and their estates were divided among their heirs. Paula’s portrait was to be bequeathed to the Österreichische Galerie (now Belvedere, Vienna), but the painting was lost in Berlin due to the turmoil of war; its whereabouts have remained unknown to this day.

Primavesi Family

In the spring of 1912, Eugenia and Otto Primavesi commissioned the artist to paint a portrait of their then nine-year-old daughter Eugenia Franziska, called Mäda. The wealthy banker and industrialist Primavesi and his family lived in Ölmütz (now Olomouc, Czech Republic), but they were closely connected to the Viennese circle of artists around Gustav Klimt and in 1914 took over shares in the Wiener Werkstätte. They probably knew Klimt before 1912, their acquaintance becoming closer over the years to come.

Portrait of Mäda Primavesi (1913, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) is one of Klimt’s rare portraits of a child. It is particularly striking that Mäda, born in 1903, does not seem very childlike. Standing broad-legged, her right hand resting on her hip and her left arm held behind her body, the girl looks straight out of the picture. A side parting and a blue bow in her hair counterbalance the arm position. With the design of the background, Klimt harked back to the portraits painted the previous year, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II (1912, private collection) and Portrait of Paula Zuckerkandl (1912, whereabouts unknown): patterned expanses dividing the space into separate zones, with the triangular carpet-like area behind Mäda’s legs reminiscent of Klimt’s landscape paintings and once again taking up and augmenting the triangular composition of the upright standing figure. With Mäda positioned at the very bottom of the picture plane, Klimt combined the flowers of her dress with the floral ornaments in the background, both in terms of color and motif. The animal motifs, on the other hand, he borrowed from an Asian vocabulary of form. The sitter later remembered the lengthy work process:

“Every few months we would travel to Vienna and stay there for about ten days. I was a little girl, and Professor Klimt was incredibly nice. When I became impatient, he simply said: ‘Just keep sitting here for a few more minutes.’”

While Gustav Klimt was still working on Portrait of Mäda Primavesi, her mother commissioned him to paint her own likeness, for which she posed for Klimt in Vienna. In 1913, Eugenia Primavesi wanted to give her own portrait to her husband Otto in Olomouc for Christmas, as becomes clear from her correspondence. However, Klimt could not meet the desired deadline. Although he had confirmed receipt of an advance payment on 18 June 1913, he still did not consider the painting “finished” six months later.

Klimt had meticulously prepared the composition Portrait of Eugenia (Mäda) Primavesi (1913/14, Toyota Municipal Museum of Art) in a large number of drawn studies. In the painting, he moved the sitter, viewed frontally, to the foreground, thereby cropping the colorfully patterned reform dress at the lower margin of the picture. A follower and future owner of the Wiener Werkstätte, the patroness appears in a dress that corresponded to the Wiener Werkstätte’s modern designs. Her bust is set against a green field arched at the top, which particularly emphasizes Eugenia Primavesi’s upper body. This painterly element is reminiscent of Portrait of Fritza Riedler (1906, Belvedere, Vienna). In the upper right corner, Klimt positioned the depiction of a phoenix, quoting a Chinese or Japanese model. The portrait’s radiant background in lemon yellow is divided into two zones. Whereas in the portraits of 1912 Klimt had still framed the individual fields of the background and differentiated between them using different colors, in this portrait they are distinguished by the use of floral motifs. The pattern of scattered flowers is most clearly recognizable in the green field behind Eugenia Primavesi’s head and shoulders and diminishes considerably in the rest of the background.

What makes Portrait of Eugenia (Mäda) Primavesi once again so captivating is the interplay between the naturalistically rendered portrait and the liberally painted, expressively patterned and colored background. The precise description of the head, décolleté, hands, and jewelry is set off against the seemingly spontaneously placed, almost abstract shapes in the dress and background. In some spots, the canvas and the preparatory underdrawing have remained visible.

Literature and sources

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007.

- John Collins: Ria Munk on Her Deathbed, in: Colin B. Bailey (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Modernism in the Making, Ausst.-Kat., National Gallery of Canada (Ottawa), 15.06.2001–16.09.2001, Ottawa 2001, S. 126-127.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt 150 Jahre, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 13.07.2012–27.01.2013, Vienna 2012.

- N. N.: Lebensmüde, in: Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 29.12.1911, S. 8.

- Ansichtskarte von Gustav Klimt in Wien an Emilie Flöge in Paris, 2. Karte (28.02.1913). RL 2874, .

- Ansichtskarte von Gustav Klimt in Wien an Emilie Flöge in Bad Gastein, 2. Karte (Morgen) (26.06.1912). RL 2861, .

- Tobias G. Natter, Gerbert Frodl (Hg.): Klimt und die Frauen, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 20.09.2000–07.01.2001, Cologne 2000.

- Wolfgang Georg Fischer: Gustav Klimt und Emilie Flöge. Genie und Talent, Freundschaft und Besessenheit, Vienna 1987.

- Claudia Klein-Primavesi: Die Familie Primavesi und die Wiener Werkstätte. Josef Hoffman und Gustav Klimt als Freunde und Künstler, Vienna 2006.

- Hedwig Steiner: Gustav Klimts Bindung an Familie Primavesi in Olmütz, in: Mährisch-Schlesische Heimat. Vierteljahresschrift für Kultur und Wirtschaft, Heft 4 (1968), S. 242-252.

- Alfred Weidinger: Gustav Klimt- machistisches Selbstverständnis und nervöse Heroinen. Gedanken zum Frauenbild, in: Agnes Husslein-Arco, Jane Kallir, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Klimt, Schiele, Kokoschka und die Frauen, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna), 22.10.2015–28.02.2016, Munich 2015.

- Brief von Eugenia „Mäda“ Primavesi sen. in Olmütz an Anton Hanak (26.01.1912). Mappe 17.

- Brief von Eugenia „Mäda“ Primavesi sen. in Olmütz an Anton Hanak (15.02.1912). Mappe 17.

- Ansichtskarte von Gustav Klimt in Wien an Emilie Flöge am Semmering, 2. Karte (28.02.1912). RL 2855, .

- Brief von Eugenia „Mäda“ Primavesi sen. in Olmütz an Anton Hanak (07.02.1913). Mappe 17.

- Brief von Adele Bloch-Bauer in Elbekosteletz an Julius Bauer (22.08.1903). Autogr. 577/52-1, .

- Hermann Muthesius: Landhäuser. ausgeführte Bauten mit Grundrissen, Gartenplänen und Erläuterungen, 2. Auflage, Munich 1922.

- Arthur Schnitzler: Tagebuch. Digitale Edition, Montag, 1. Jänner 1912. schnitzler-tagebuch.acdh.oeaw.ac.at/entry__1894-03-18.html (09/19/2022).

- Johannes Wieninger: „Im Bücherschrank steht eine chinesische Vase“. Ostasiatisches im Spätwerk von Gustav Klimt, in: Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl, Felizitas Schreier, Georg Becker (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Atelier Feldmühlgasse 1911–1918, Vienna 2014.

The Stoclet Frieze. Completion

Paula Deetjen: Insight into the Palais Stoclet, 1917/18, Deutsches Dokumentationszentrum für Kunstgeschichte

© Bildarchiv Foto Marburg

Designing the Stoclet Frieze, which had been commissioned from him in 1905, was to keep Gustav Klimt busy over many years. It was not until 1910/11 that he made his nine large-sized work drawings, in which he made annotations as to the choice of materials and the execution. The work was finally completed in 1911 by Leopold Forstner’s Mosaic Workshop and installed at the Stoclet Palace in Brussels.

In 1910/11, Gustav Klimt worked intensively on the work drawings (1910/11, MAK, Vienna) for the Stoclet Frieze (1905–1911, private collection), a work conceived for the dining room at the Brussels palace of the Stoclet family. Klimt executed the nine work or design drawings, each measuring 200 by 102 centimeters, true to scale in pencil, colored pencil, pastel, gold, platinum, silver, and bronze on tracing paper, annotating instructions for their realization as to the materials to be used. The mosaic frieze for the Palais Stoclet, executed by the Wiener Werkstätte, is one of Gustav Klimt’s most prestigious works, whose fame can be attributed primarily to the motif of the Tree of Life. Since the palace is family-owned and not open to the public, only a small number of color photographs of the Stoclet Frieze have been published to date.

Gustav Klimt: Standing nude of a pair of lovers (study for "fulfillment" in the stoclet frieze), 1907/08, The Albertina Museum

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

By 1905 at the latest, Gustav Klimt had received a commission from Adolphe and Suzanne Stoclet for a frieze for the dining room of their house, which had been planned by Josef Hoffmann. As early as 1906, Klimt exchanged ideas about the materials to be employed with Fritz Waerndorfer, with whom he was visiting the construction site in Brussels at the time. The first designs can be dated to 1907/08; especially in the summer of 1908, Klimt worked intensively on the project while staying on the Attersee. Shortly before, those involved in the “Kunstschau Wien,” an exhibition of Viennese art organized and curated by the so-called Klimt Group, had agreed on a realization in the form of a “flattish color mosaic.” As had been the case with several previous commissions, the painter suffered from fear of failure here as well, which was the reason for delays in the schedule of execution.

Work Drawings

Following initial figure studies and sketches dating from the years in which he explored the emotional and erotic connection of lovers, Klimt set to work intensively on the work drawings in the summer of 1910. The depiction was based on a composition sketch now lost, which has survived as a heliographic print squared for transfer (1907/08, Wien Museum, S 1982: 1693). Klimt began working when still in Vienna, but in a letter to Emilie Flöge from 28 July 1910 he announced:

“In the countryside I will unfortunately have to be very diligent for Stoclet, which goes against the grain for me. What is more, there will be ‘journey-to-Vienna interruptions.’ But it will and must and will work out.”

He thus continued working on the drawings during his summer retreat at Villa Oleander on the Attersee. It can be assumed that he completed them in the fall and winter of 1910/11, when he was back in Vienna.

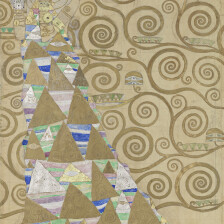

Work Drawings for the Stoclet Frieze

-

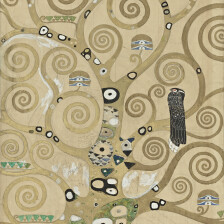

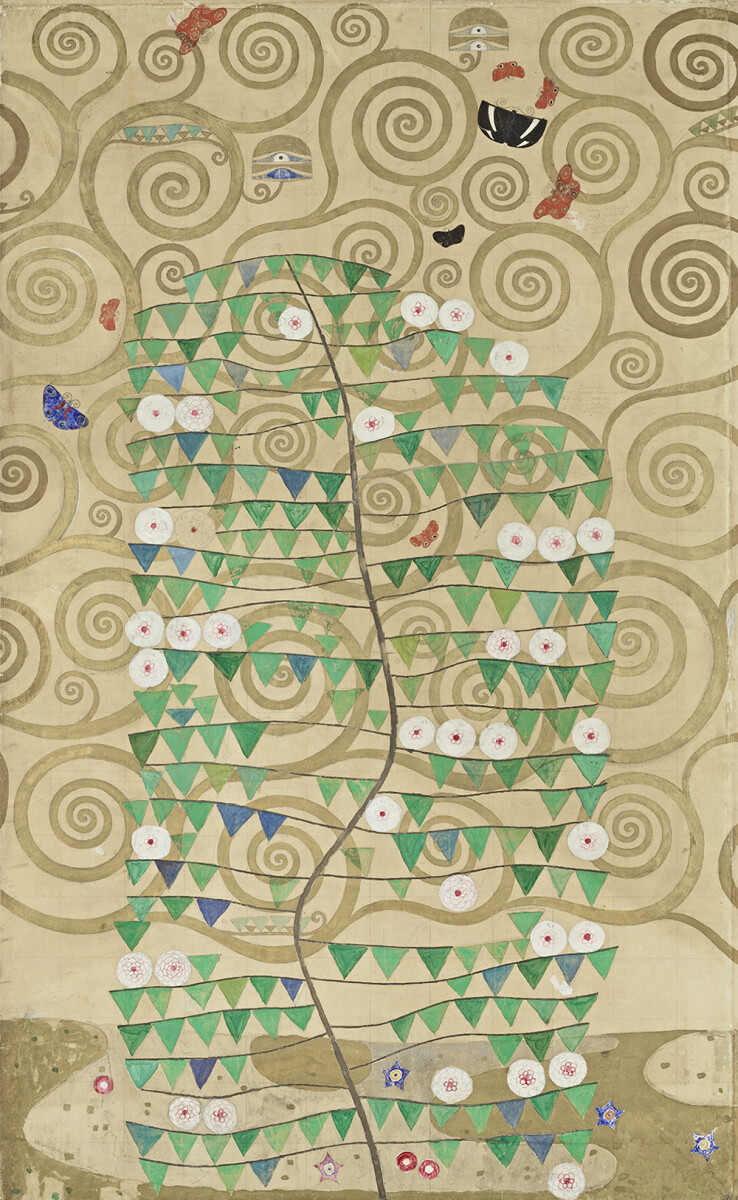

Gustav Klimt: Stoclet frieze "Tree of Life" (work drawing), 1910/11, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

Gustav Klimt: Stoclet frieze "Tree of Life" (work drawing), 1910/11, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

© MAK -

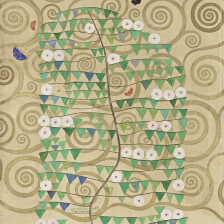

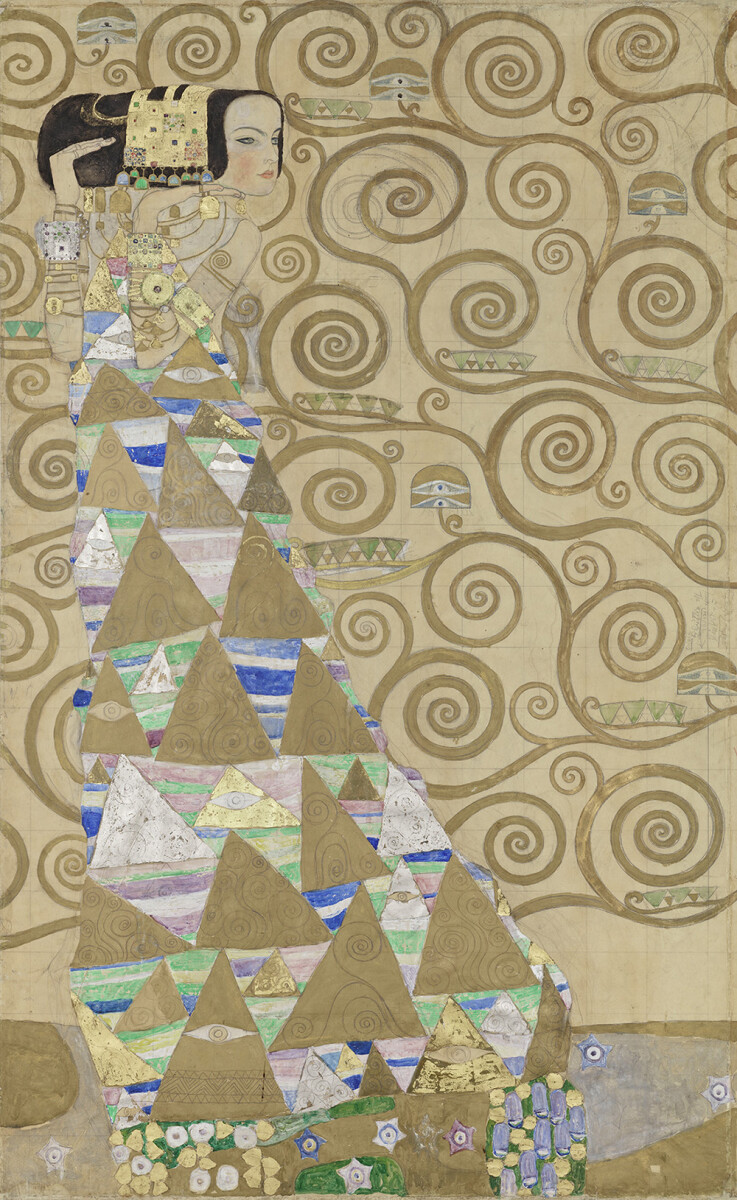

Gustav Klimt: Stoclet frieze "The Expectation (Dancer)" (work drawing), 1911, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

Gustav Klimt: Stoclet frieze "The Expectation (Dancer)" (work drawing), 1911, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

© MAK -

Gustav Klimt: Stoclet frieze "Tree of Life" (work drawing), 1910/11, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

Gustav Klimt: Stoclet frieze "Tree of Life" (work drawing), 1910/11, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

© MAK -

Gustav Klimt: Stoclet frieze "Tree of Life" (work drawing), 1910/11, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

Gustav Klimt: Stoclet frieze "Tree of Life" (work drawing), 1910/11, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

© MAK -

Gustav Klimt: Stoclet frieze "Tree of Life" (work drawing), 1910/11, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

Gustav Klimt: Stoclet frieze "Tree of Life" (work drawing), 1910/11, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

© MAK -

Gustav Klimt: Stoclet frieze "Rose bush" (work drawing), 1910/11, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

Gustav Klimt: Stoclet frieze "Rose bush" (work drawing), 1910/11, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

© MAK -

Gustav Klimt: Stoclet frieze "Tree of Life" (work drawing), 1910/11, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

Gustav Klimt: Stoclet frieze "Tree of Life" (work drawing), 1910/11, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

© MAK -

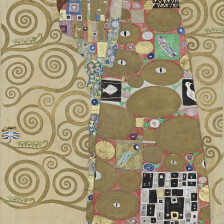

Gustav Klimt: Stoclet frieze "Fulfillment" (work drawing), 1911, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

Gustav Klimt: Stoclet frieze "Fulfillment" (work drawing), 1911, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

© MAK

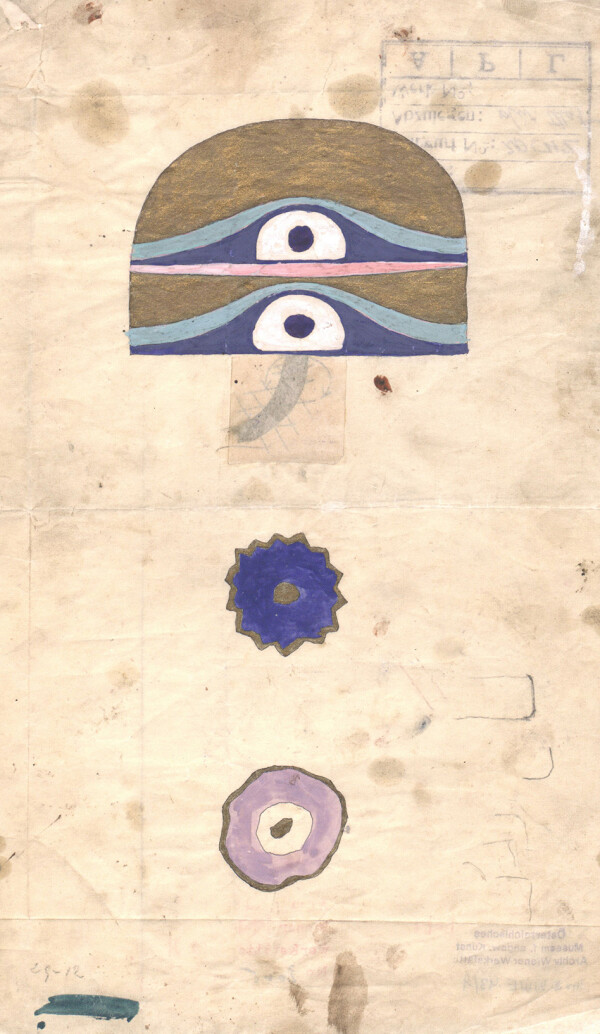

Gustav Klimt: Design of flowers for the stoclet frieze, MAK - Museum für angewandte Kunst, Archiv der Wiener Werkstätte

© MAK

Flower motif (eye) from the dining room frieze in the Palais Stoclet, Museum of Applied Arts, 1910: Flower motif (eye) from the dining room frieze in the Palais Stoclet, Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna

© MAK

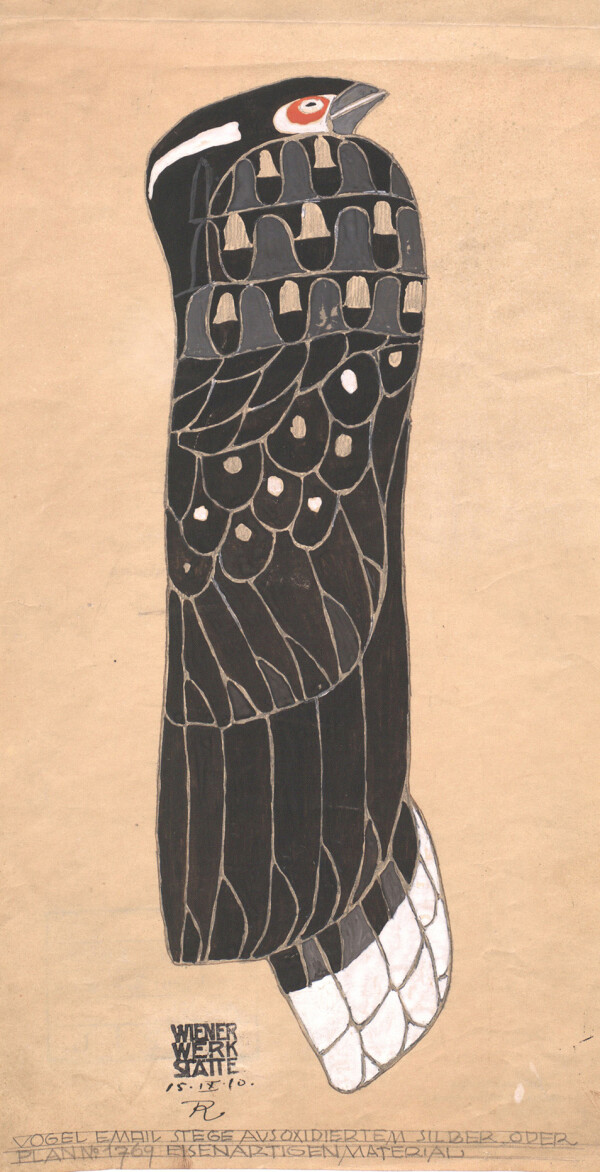

Gustav Klimt: Design drawing for a bird from the Stoclet frieze, 1910, MAK - Museum für angewandte Kunst, Archiv der Wiener Werkstätte

© MAK

Since the two longitudinal walls in the dining room were designed to be axially symmetrical, Klimt concentrated entirely on the wall with the dancer. For the opposite side, a “transferrer” of the mosaic workshop created a mirror inverted version with the Tree of Life and its spiral branches, as well as the rose bush. Therefore, for this side Klimt only had to execute the Lovers of Fulfillment, a motif to be inserted instead of the dancer.

Klimt used a roll of tracing paper two meters wide for the work drawings, which he cut into vertical strips of about one meter to obtain nine individual sheets. The artist used the unpainted areas of the designs to communicate precise instructions to the artisans regarding the materials and colors for their execution.

The tedious process of the work drawings can be observed in the details. Over a rough sketch Klimt drew the precise outlines using a graphite pen (pencil), filling them with soft, thick chalk. For the precise shapes of the spiral branches he used a curve template. The coloring was done with colored pencils, pastels, and metallic powder, as he continued to develop the composition in layers. Klimt’s material luxury in the Stoclet Frieze even went so far as to use real platinum and gold leaf for the work drawings, as well as gold, bronze, and silver powder, which he mixed with zinc white.

Realization: “Damned Expensive”

The three-part frieze extends over three walls in the dining room of the Stoclet Palace. On a meadow with flowers and water stands the famous Tree of Life, with three black hawks and eye flowers, extending over the entire lengths of the west and east walls. For the front wall Klimt devised an ornamental, highly abstracted depiction of a knight. On the west wall, he added a rose bush surrounded by butterflies and a female figure described as dancer or Anticipation. On the east wall, the design was mirrored, while the dancer was replaced by a pair of lovers interpreted as Fulfillment or Embrace.

In the Stoclet Frieze, Gustav Klimt developed a two-dimensional, ornamental visual concept, bringing together man and nature in a design of Symbolist elevation. He found inspiration in Japanese art, early Christian mosaics, and ancient Egyptian symbolism, from which he borrowed Horus the falcon god.

Having received material samples that had been sent to Klimt during his stay on the Attersee, he wrote a long letter to Fritz Waerndorfer in which he expressed his fears and concerns about the execution and choice of materials:

“Several things about the samples sent left me discouraged at first – giving it more thought, though, I have regained my composure, but the thing must nevertheless be handled differently. […] The scrolls of the ‘Tree’ should primarily be made with the warm gold ‘coming closest to gold’ and mixed just a little with the other gold, the greenish (not green), the blackish, and the rough gold (which can be used a bit more profusely). […] The bird will be in black and dark gray enamel, with a little white. The fillets should likewise be dark gray (oxidized). […] As to the tree trunk, several of the white round shapes (I’ve marked them) should be done in mother-of-pearl, others with a piece of white material surrounded by metal – most of the patches are intended as mosaics. I have known from the very start that the whole thing will be damned expensive […].”

Several companies were responsible for the extremely complex and costly execution of the work: the Wiener Werkstätte, the marble company Oreste A. Bastreri, the Wiener Keramik factory, and the Enamel Class of the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts were entrusted with manufacturing the various individual parts made of marble, ceramics, chased metal, beads, gemstones, and enamel. Leopold Forstner’s Mosaic Workshop was again put in charge of the assembly and realization of the individual parts and the inlay work. The so-called plate mosaic, consisting of a total of 15 mosaic plates, was made in Vienna and personally assembled by Forstner in Brussels in 1912.

Insight into the Palais Stoclet, circa 1914

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Contemporary Commentaries

Interestingly, the work on the Stoclet Frieze was not registered in the Wiener Werkstätte’s model books, although they meticulously list 214 purchases made by the Stoclet family. This could have to do with the fact that the work was produced in the Mosaic Workshop of Leopold Forstner, who made it accessible to the Viennese public in his workshop at Pappenheimgasse 41 at the end of October 1911, before it was delivered to Brussels. There it had been seen by Berta Zuckerkandl, who wrote about the “Klimt Frieze” and the artists manufacturing it in the Allgemeine Wiener Zeitung on 23 October 1911:

“In terms of material, Klimt’s original (his drawing in colors already calculated for the material transfer) was realized by the Metal- and Goldsmith’s Workshop of the ‘Wiener Werkstätte,’ by the Enamel School of the School of Arts and Crafts (Miss Starck, Miss König), the Wiener Keramik factory (Professor B. Löffler, Professor Powolny), the Mosaic Workshop (Leopold Forstner), and the Oreste A. Bastreri Marbleworks.”

A few days later, Arthur Roessler provided a long description of this “unique work of art” in the Arbeiter-Zeitung, regretting that the frieze was not to remain in Vienna:

“It is not possible to describe Klimt’s new work, for it must be seen in all of its metallic shimmer and blaze of colors in order to be appreciated as one of the most remarkable and, in terms of decoration, most impressive accomplishments of modern art. It is only regrettable that Klimt’s masterpiece is lost for us. Who will entrust the artist with a similar commission for Vienna?”

Literature and sources

- Beate Murr: I. Die Entwurfszeichnungen zum Stoclet Fries: Ihre Entstehung, Umsetzung und Restaurierung, in: Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Beate Murr (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Erwartung und Erfüllung. Entwürfe zum Mosaikfries im Palais Stoclet, Ausst.-Kat., MAK - Museum of Applied Arts (Vienna), 21.03.2012–15.07.2012, Vienna 2012, S. 11-42.

- Arthur Roessler: Theater und Kunst. Wiener Mosaikwerkstätte, in: Arbeiter-Zeitung (Morgenausgabe), 29.10.1911, S. 11.

- Elisabeth Schmuttermeier: Adolphe und Suzanne Stoclet als Auftraggeber der Wiener Werkstätte, in: Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Beate Murr (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Erwartung und Erfüllung. Entwürfe zum Mosaikfries im Palais Stoclet, Ausst.-Kat., MAK - Museum of Applied Arts (Vienna), 21.03.2012–15.07.2012, Vienna 2012, S. 48-67.

- Alfred Weidinger: 100 Jahre Palais Stoclet. Neues zur Baugeschichte und künstlerischen Ausstattung, in: Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt – Josef Hoffmann. Pioniere der Moderne, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna) - Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 25.10.2011–04.03.2012, Munich 2011, S. 202-251.

- Berta Zuckerkandl: Der Klimt-Fries, in: Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, 23.10.1911, S. 2.

- Christian Witt-Döring: Palais Stoclet, in: Christian Witt-Dörring, Janis Staggs (Hg.): Wiener Werkstätte. 1903–1932: The Luxury of Beauty, Ausst.-Kat., New Gallery New York (New York), 26.10.2017–29.01.2018, Munich - London - New York 2017, S. 368-410.

- Ansichtskarte von Gustav Klimt in Wien an Emilie Flöge in Kammer am Attersee, 2. Karte (Morgen) (07/28/1910). RL 2842, .

Kammer Castle and Flowering Gardens: A Recurrent Motif

Gustav Klimt: Kammer Castle on the Attersee III, 1910, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Kammer Castle on the Attersee IV, 1910, private collection

© Gallery Welz Salzburg

Gustav Klimt: Avenue in Front of Kammer Castle on the Attersee, 1912, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Upper Austrian Farmhouse, 1911, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Orchard with Roses, 1912, private collection

© Bridgeman Images

In his landscapes painted from 1910 on, Gustav Klimt once again devoted himself to depictions of Kammer Castle and its immediate surroundings. Moreover, he immortalized the contemplative landscape of the Attersee in a number of paintings.

Inspirational Potential of a Water Castle and Its Alley

In 1910, Klimt once again committed Kammer Castle to canvas in a pronouncedly cropped view. In the compositions Kammer Castle on the Attersee III (1910, Belvedere, Vienna) and Kammer Castle on the Attersee IV (1910, private collection) he combined the architectural motif with the elements of water and vegetation, as he had done before. The vantage point from which Klimt painted or at least sketched these two views of the castle was located in the area of the former Hotel Seehof. While the third version was on display at Galerie Miethke that same year, variant number four was presented at the “Große Kunstausstellung Dresden” [“Great Dresden Art Exhibition”] of 1914.

In Avenue in Front of Kammer Castle on the Attersee (1912, Belvedere, Vienna), Klimt captured the promontory that connected the old water castle with the shore, and which was planted with an alley of linden trees. The expansive trees, their crowns uniting in the upper half of the picture, constitute the principal motif of the composition – and a rewarding one at that, due to their sometimes bizarrely shaped trunks and gnarled crotches, molded by wind and rain. Inspired by Vincent van Gogh, Klimt brought the alley’s treetops together to create a massive whole. They appear as shadowy, bluish green forms outlined by dark contours. The yellow painted building in the Baroque style, with its curved gables and portal overgrown with ivy, forms the prospect’s conspicuous end point. Between the tree trunks on the left, the view opens up to the Attersee.

Summery Gardens

At his summer retreat on the Attersee, Klimt also discovered the motif of a building surrounded by a flowering meadow and trees, which inspired him to paint Upper Austrian Farmhouse (1911, Belvedere, Vienna). The theme of a balanced ensemble of architecture, cultivated landscape, and natural scenery seems realized here in a most harmonious manner. Shadows cast by the foliage and light falling in produce the remarkably deep blue to violet color of the wooden slats of the house, whose structure is obscured by the rich vegetation. Rendering his immediate impressions, Klimt painted what he saw in a particularly rich and varied depiction of light reflections in the Pointillist style. He enriched this cropped view with such narrative details as the windows adorned with flowers, the carefully piled-up logs along the wall of the house, and the bed of sunflowers near the right margin of the picture. The tree on the right has been pushed so closely to the foreground that it is overlapped by the lower and upper margins, allowing viewers to share Klimt’s impression by directing their gaze. The tree on the left, slightly staggered, suggests depth, by which the artist achieved a subtle balance between flatness and spatial illusionism. Klimt executed the wooden slats with vertical strokes in thin, fluid oil paint; he rendered the flowering meadow in front of the building in a Pointillist manner. In this way, Klimt created tension in the application of paint and thus throughout the canvas as a whole. This painting was first exhibited in 1912 as part of the “Große Kunstausstellung Dresden” [“Great Dresden Art Exhibition”].

At this show, Klimt also presented the work Apple Tree I (Small Apple Tree) (c. 1912, private collection) to a broad public. In this painting, he intensified his meditative immersion in the experience of nature. At the center appears a tree full of ripe, red fruit ready for harvest. Klimt’s style appears more impasto and loose, while at the same time he allows individual details, such as the coloristically modeled forms of the ripe fruit and the blossoms in the foreground of the picture, to stand out through their intensity of color.

In the motif Country Garden with Calvary (1912, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945), Klimt combined the coloristically transfigured image of nature with the popular wayside cross in a Symbolist approach. At this site of devotion, the experience of nature and spirituality are in harmony. In 1914 the picture was presented at an exhibition of the Deutsch-Böhmischer Künstlerbund [German-Bohemian Artists’ Association].

In 1912 the artist also painted a landscape whose overwhelming splendor of blossoms could probably not be found on the shores of the Attersee, but in the garden of Klimt’s studio in Hietzing, Vienna’s 13th District. His poetic reference to cultivated nature found particularly prominent expression in Orchard with Roses (1912, private collection). The contrasting color values create the impression of a rich texture as an autonomous artistic value. Egon Schiele described the garden as “embellished with flowerbeds throughout the year – it was a pleasure to come here and be surrounded by blossoms and old trees.” This view of the garden was also shown in Prague in 1914.

The impressions of nature and architecture combined, committed to canvas on the Attersee and in Vienna, would be continued the following year on Lake Garda.

Further contents

Literature and sources

- Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Florale Welten, Vienna 2019.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012.

- Toni Stoos, Christoph Doswald (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Ausst.-Kat., Kunsthaus Zurich (Zurich), 11.09.1992–13.12.1992, Stuttgart 1992.

- Stephan Koja: Der Sommer in Kammer am Attersee, in: Stephan Koja (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Landschaften, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 23.10.2002–23.02.2003, Munich 2002.

- Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sommerfrische am Attersee 1900-1916, Vienna 2022, S. 65.

- Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl, Felizitas Schreier, Georg Becker (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Atelier Feldmühlgasse 1911–1918, Vienna 2014.

- Arthur Roessler: Erinnerungen an Egon Schiele, Vienna 1948, S. 48-49.

Monuments for Lake Garda

Gustav Klimt: Italian Garden Landscape, 1913, Kunsthaus Zug

© Kunsthaus Zug, Stiftung Sammlung Kamm

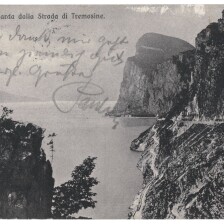

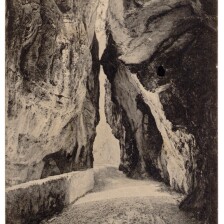

Three landscape paintings bear witness to Klimt’s stay on Lake Garda in the summer of 1913. Two architectural views attest to the continuation of Klimt’s tendency toward two-dimensionality in his art, while in the garden landscape he captured nature in full bloom.

Summer Retreat on Lake Garda

Three landscape paintings from 1913 were the result of the artist’s trip to Lake Garda in Italy: Italian Garden Landscape (1913, Kunsthaus Zug, Stiftung Sammlung Kamm, Zug), Malcesine on Lake Garda (1913, whereabouts unknown, considered lost since the end of the war in 1945), and Church in Cassone on Lake Garda (1913, private collection). Ten years earlier, in December 1903, Klimt had sojourned at this lake in Northern Italy before.

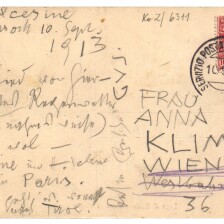

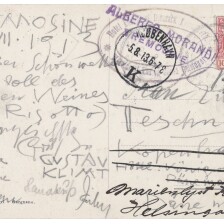

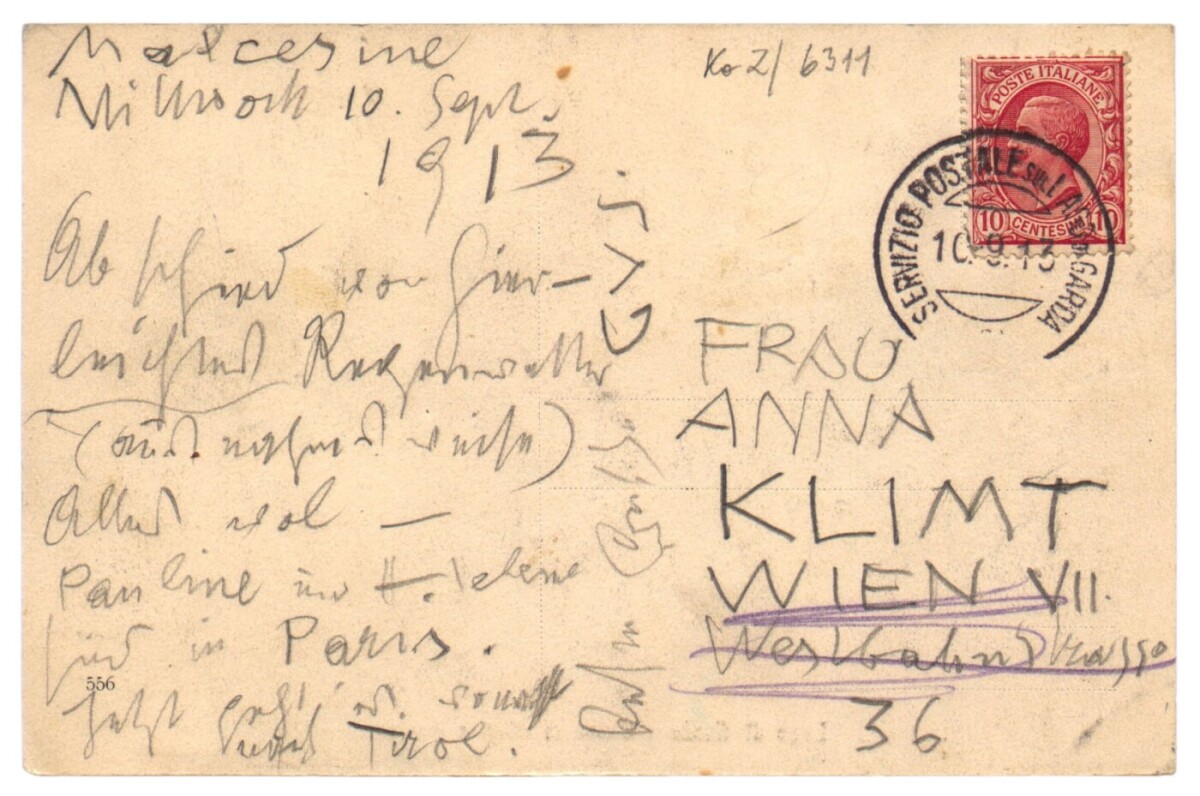

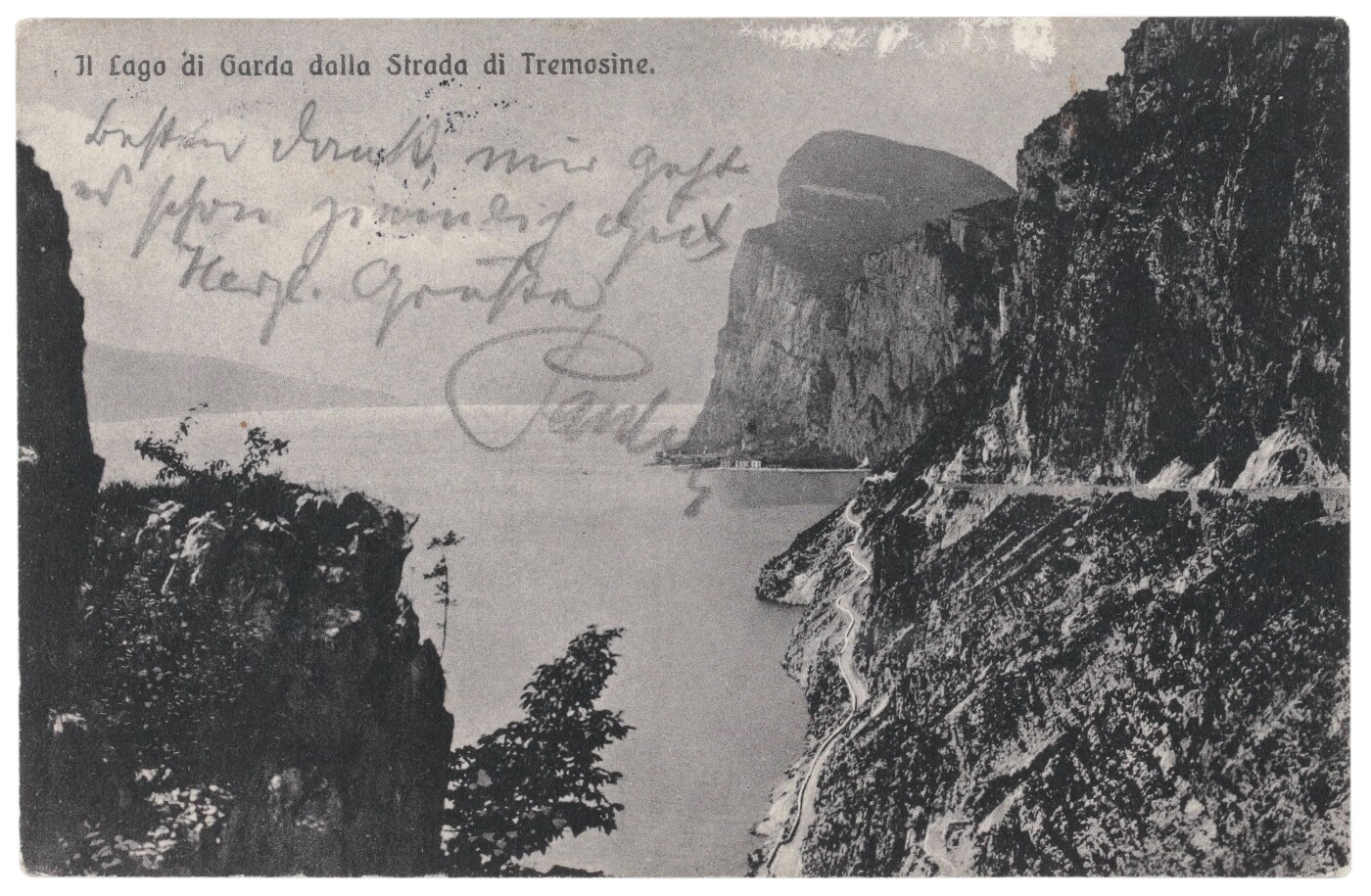

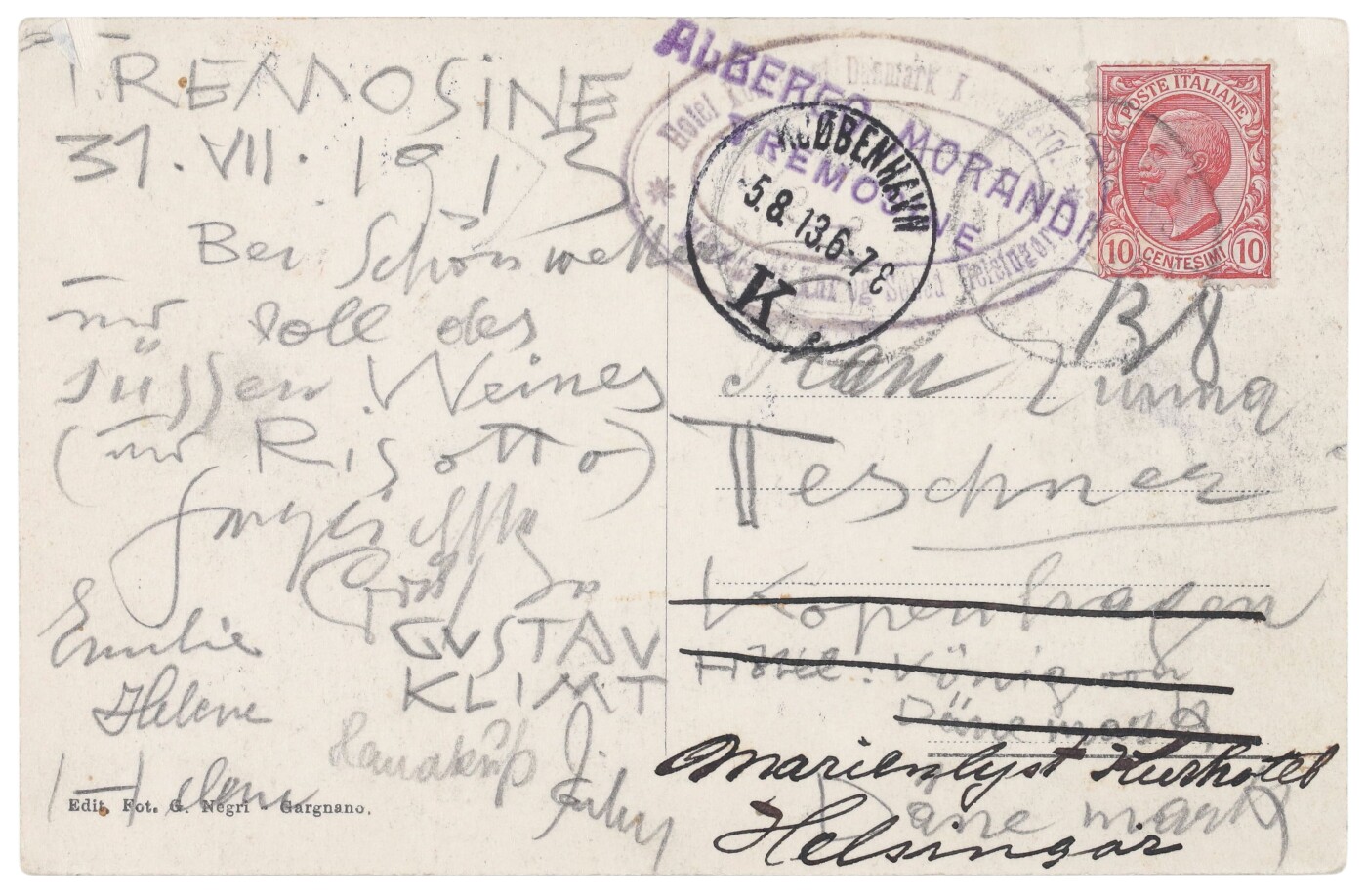

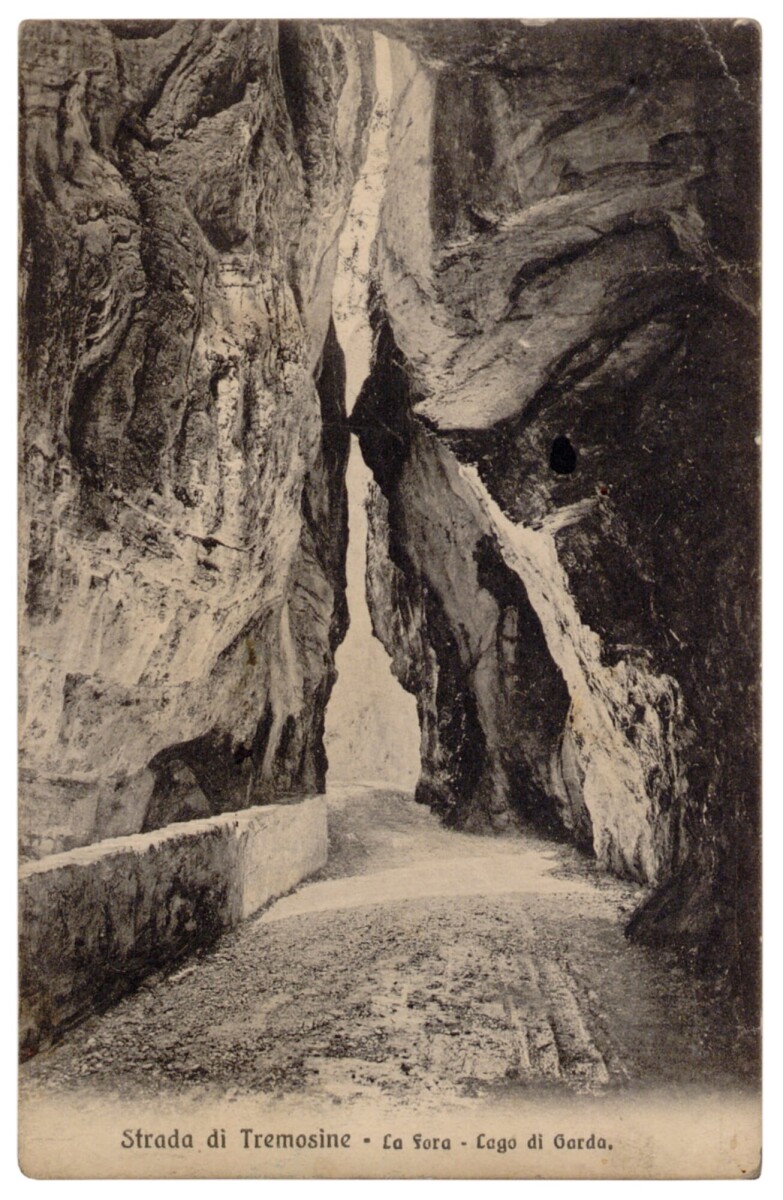

From the end of July until 10 September 1913, Klimt spent his summer vacation on Lake Garda. At times, Emilie and Pauline Flöge, Helene Klimt (née Flöge), his niece, “Lentschi” Klimt, and Josef Eibl were also present Klimt seems to have accepted an invitation from one of his collectors, Emil Zuckerkandl. The party stayed at the Albergo Morandi in Tremosine, a village on the western shore of the lake that afforded a view of Malcesine and its suburb, Cassone, four kilometers away – lakeside features the artist was to capture in his paintings.

Lake Garda, around 1910

© Austrian National Library

Picture Postcards from Gustav Klimt on Lake Garda

-

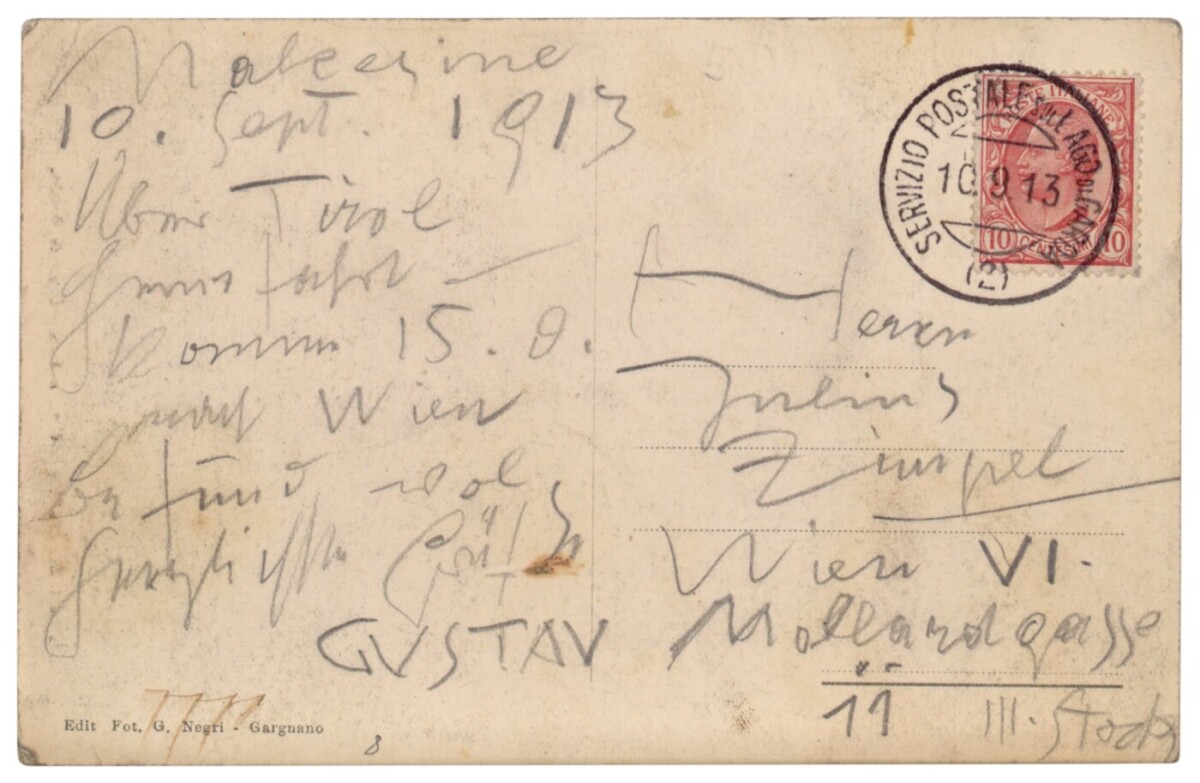

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Malcesine on Lake Garda to Anna Klimt in Vienna, 09/10/1913, The Albertina Museum

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Malcesine on Lake Garda to Anna Klimt in Vienna, 09/10/1913, The Albertina Museum

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Malcesine on Lake Garda to Anna Klimt in Vienna, 09/10/1913, The Albertina Museum

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Malcesine on Lake Garda to Anna Klimt in Vienna, 09/10/1913, The Albertina Museum

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt, Pauline Flöge: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt and Pauline Flöge in Tremosine to Emma Bacher-Teschner in Denmark, co-signed by Emilie Flöge, Josef Eibl, Helene Klimt sen. and Helene Klimt jun., 07/31/1913, Sammlung Villa Paulick, courtesy Klimt-Foundation, Wien

Gustav Klimt, Pauline Flöge: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt and Pauline Flöge in Tremosine to Emma Bacher-Teschner in Denmark, co-signed by Emilie Flöge, Josef Eibl, Helene Klimt sen. and Helene Klimt jun., 07/31/1913, Sammlung Villa Paulick, courtesy Klimt-Foundation, Wien

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt, Pauline Flöge: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt and Pauline Flöge in Tremosine to Emma Bacher-Teschner in Denmark, co-signed by Emilie Flöge, Josef Eibl, Helene Klimt sen. and Helene Klimt jun., 07/31/1913, Sammlung Villa Paulick, courtesy Klimt-Foundation, Wien

Gustav Klimt, Pauline Flöge: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt and Pauline Flöge in Tremosine to Emma Bacher-Teschner in Denmark, co-signed by Emilie Flöge, Josef Eibl, Helene Klimt sen. and Helene Klimt jun., 07/31/1913, Sammlung Villa Paulick, courtesy Klimt-Foundation, Wien

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Picture Postcard from Gustav Klimt in Malcesine on Lake Garda to Julius Zimpel sen. in Vienna, 09/10/1913, The Albertina Museum

Gustav Klimt: Picture Postcard from Gustav Klimt in Malcesine on Lake Garda to Julius Zimpel sen. in Vienna, 09/10/1913, The Albertina Museum

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Picture Postcard from Gustav Klimt in Malcesine on Lake Garda to Julius Zimpel sen. in Vienna, 09/10/1913, The Albertina Museum

Gustav Klimt: Picture Postcard from Gustav Klimt in Malcesine on Lake Garda to Julius Zimpel sen. in Vienna, 09/10/1913, The Albertina Museum

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Church in Cassone on Lake Garda, 1913, private collection

© Sotheby's

Malcesine on Lake Garda

© Austrian National Library

Gustav Klimt: Malcesine on Lake Garda, 1913, Verbleib unbekannt, in: Max Eisler (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Eine Nachlese, Vienna 1931.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Inspiring Lake Garda

In his paintings inspired by the villages of Lake Garda, Klimt held on to the flattening of architecture he had already successfully tried out in his series devoted to Kammer Castle.

Church in Cassone on Lake Garda shows a detailed view of the eponymous suburb, captivating the viewer with its bluish-gray houses covered with ocher shingle roofs. At the center of the composition appears the 17th-century church. The entire view is animated by prominent cypress trees and lush vegetation. Klimt juxtaposes contrasting color values using liberal, impasto brushstrokes, which results in a flat, visually activating expanse.

Klimt probably viewed this veduta from the western shore. The use of binoculars and a “motif finder” may, among other things, have been crucial for the two-dimensional outcome. The emphasis on orthogonal forms in the cypresses and on the horizontal shoreline, as well as the cubic shapes of the houses with the rounded treetops in between, similarly point to a rigorous pictorial order based on basic geometric elements that may have been motivated by the character of the southern landscape.

In Klimt’s depiction of Malcesine on Lake Garda (1913, considered lost since the end of the war in 1945), he created tension through the stepped arrangement of the staggering cubic houses with their reddish shingle roofs along the lakeshore, thereby accentuating the two-dimensionality of architectural detail. This is evident in the battlements of the Castello Scaligero, the prominent building on the lakeside, and the many differently colored windows and balconies. The intensely polychrome design of the façades creates a vivid pattern in the painting, which Klimt has transformed into an abstract, multicolored flickering in the reflections on the water surface. It reveals his fascination with the midsummer atmosphere and the visualization of his personal impressions. It is assumed that he was based near the Villa Gruber (now Hotel Bellevue San Lorenzo) in Dosso Ferri on the peninsula of Val di Sogno in order to be able to depict the view from the perspective represented in the picture.

In Italian Garden Landscape, Klimt’s enthusiasm for the intensity and richness of the colors of southern vegetation becomes obvious.

The spatial situation is defined by the plants of the opulently flowering garden, as they lead diagonally into the picture. With brushstrokes varying in density, Klimt directs the viewer’s eye over oleander, roses, and lavender to an almost overgrown building. What is more, he allows the viewer to catch a glimpse of the lake in the upper left corner. Compared to the garden paintings created about seven years earlier, such as Cottage Garden with Sunflowers (1906, Belvedere, Vienna), Klimt has decided in favor of a smaller-scale representation of pictorial elements. The two works created in 1912, Country Garden with Cavalry (1912, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945) and Orchard with Roses (1912, private collection), on the other hand, stylistically anticipate Italian Garden Landscape. Klimt is believed to have stood near the Albergo Morandi in Tremosine when doing this painting.

While this work was on view at the Rudolfinum in Prague as part of an exhibition of the German-Bohemian Artists’ League as early as 1914, the two paintings committed to architecture were not presented until 1928, as part of a large Klimt retrospective.

Egon Schiele underlined the importance already ascribed to these pictures during Klimt’s lifetime:

“All in all, I consider the Lake Garda pictures his most important landscapes.”

Literature and sources

- Max Eisler: Gustav Klimt, Vienna 1920.

- Johannes Dobai: Gustav Klimt. Die Landschaften, Salzburg 1981.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012, S. 566-567.

- Stephan Koja: Gardasee, in: Stephan Koja (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Landschaften, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 23.10.2002–23.02.2003, Munich 2002, S. 116-117.

- Arthur Roessler: Erinnerungen an Egon Schiele, in: Fritz Karpfen (Hg.): Das Egon-Schiele Buch, Vienna 1921.

- Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Florale Welten, Vienna 2019.

- Johannes Dobai: Die Landschaft in der Sicht von Gustav Klimt, in: Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Galerie, 22/23. Jg., Nummer 66/67 (1978/79), S. 241-272.

- Ansichtskarte von Gustav Klimt in Torbole am Gardasee an Emilie Flöge in Wien (12/10/1903).

- Paolo Boccafoglio (Hg.): Gustav Klimt e Malcesine. La famiglia Zuckerkandl e il mistero di un quadro scomparso, Arco 2013, S. 38-42.

- Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl: I viaggi in Italia di Klimt: una fonte di ispirazione per la sua arte, in: Maria Vittoria Marini Clarelli (Hg.): Klimt. La Secessione e l’Italia, Museo di Roma, Ausst.-Kat., Museo di Roma (Rome), 27.10.2021–27.03.2022, Rome 2022, S. 17-33.

Exhibition Activity

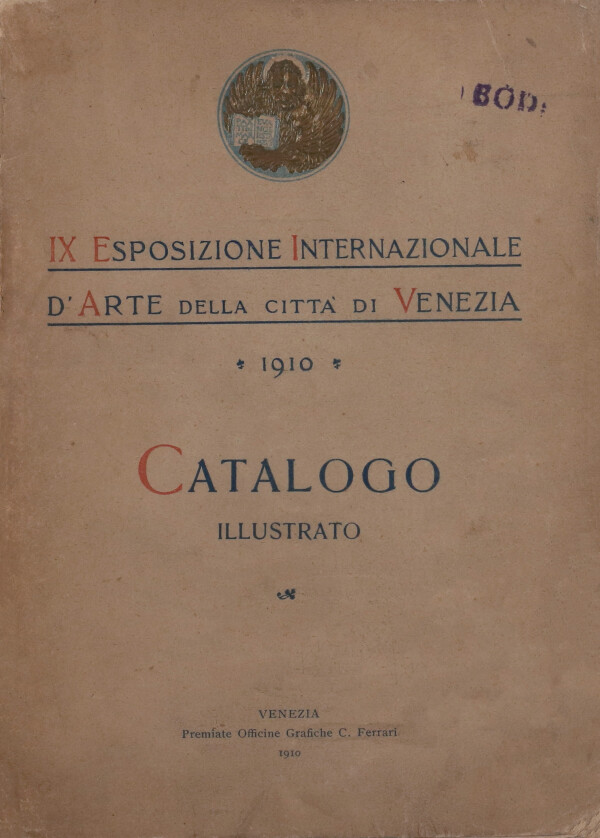

Città di Venezia (Hg.): IX. Esposizione internazionale d‘arte della città di Venezia. Catalogo Illustrato, Ausst.-Kat., Austrian Pavilion (Venice), 22.04.1910–31.10.1910, 1. Auflage, Venice 1910.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Tomaso Filippi: Insight into the IX. Venice Biennale, April 1910 - October 1910, Fondazione La Biennale di Venezia

© Archivio Storico della Biennale di Venezia, ASAC

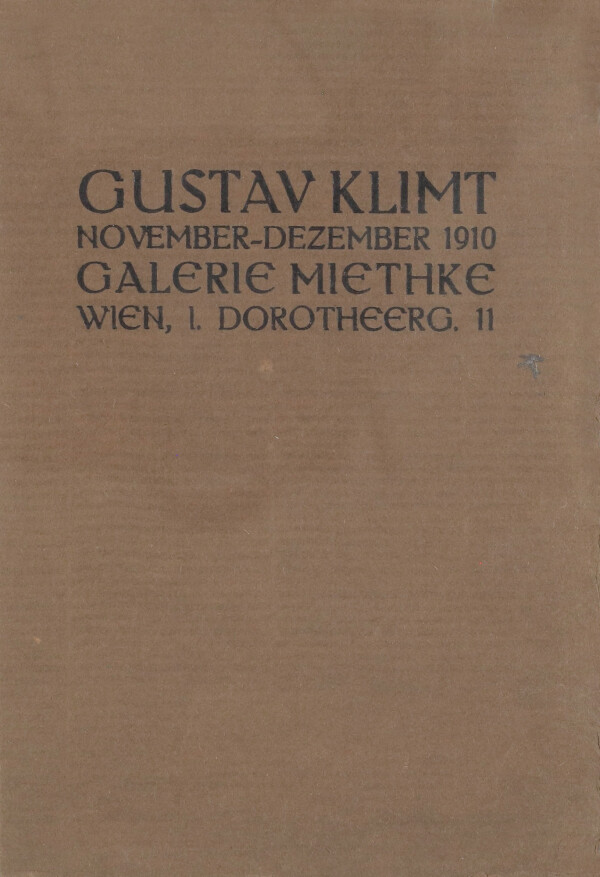

Galerie H. O. Miethke (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. November-Dezember 1910. Galerie Miethke Wien, 1. Dorotheerg. 11, Ausst.-Kat., Gallery H. O. Miethke (Vienna), 23.11.1910–18.12.1910, Vienna 1910.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Aleardo Terzi: Poster of the Rome International Art Exhibition, 1911, The Albertina Museum, Vienna

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

Between 1910 and 1913, Gustav Klimt primarily took part in exhibitions abroad. In Venice, Rome, and Budapest, separate rooms were devoted to the display of the artist’s oeuvre. In Vienna, Klimt’s hometown, his latest works were presented at Galerie Miethke. Toward the end of 1910, Viennese society had a chance to see the panels for the Stoclet Frieze for a brief period at Leopold Forstner’s Vienna Mosaic Workshop.

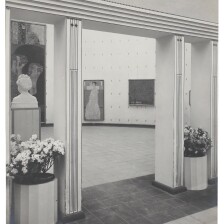

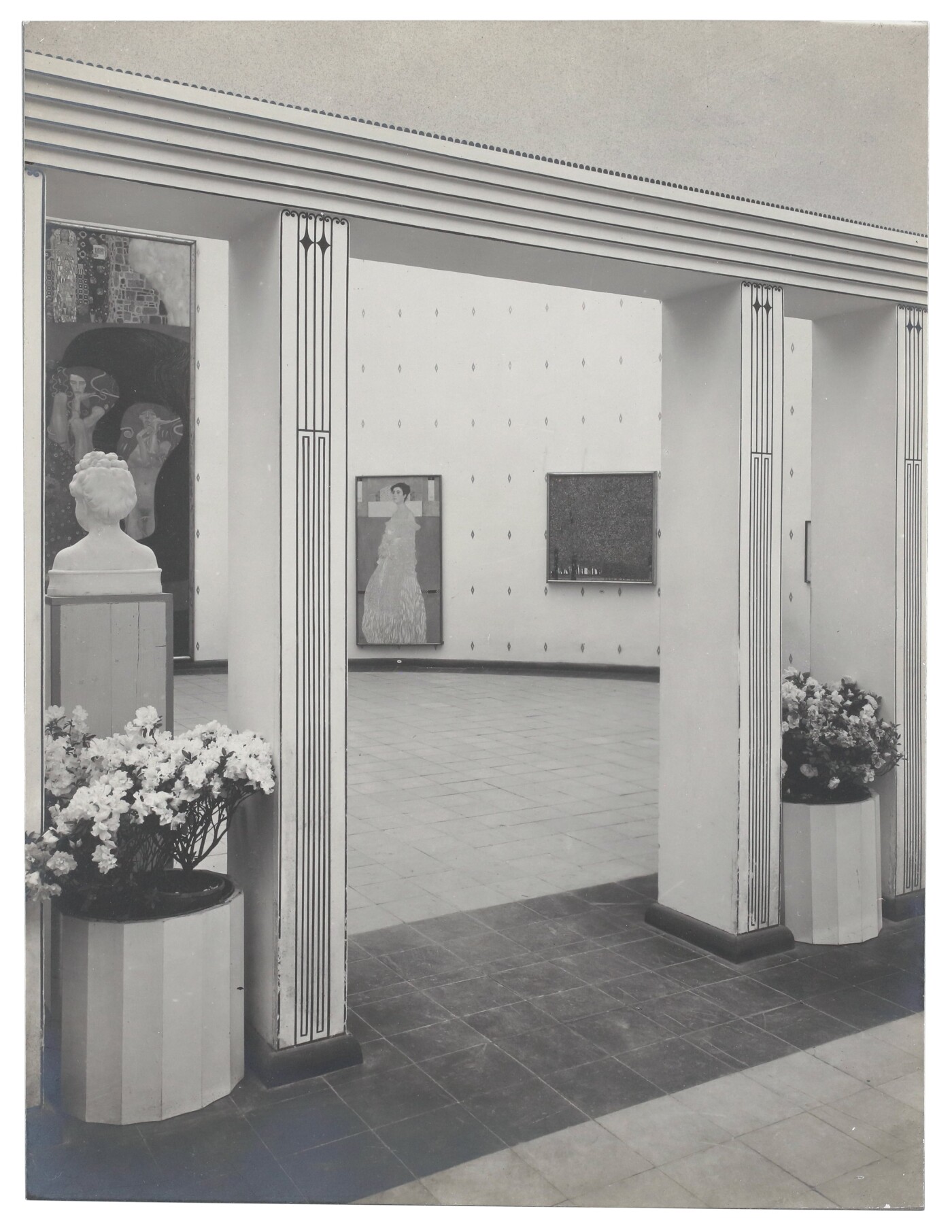

Esposizione internazionale d’arte della città di Venezia

The “IX. Esposizione internazionale d’arte della città di Venezia” [“9th International Art Exhibition of the City of Venice”] in April 1910 was the prelude to large-scale Klimt exhibitions, with an entire room reserved for Gustav Klimt. The “Mostra Individuale di Gustav Klimt” [“Individual Exhibition of Gustav Klimt”] presented twenty-two paintings by the artist in Room 10. According to the exhibition catalog, the room was designed by the architect Josef Wimmer-Wisgrill.

In Venice, Klimt introduced three new works to the public: Portrait of a Woman (Adolescent) (1910, reworked before 1916/17, Galleria d’Arte Moderna Ricci Oddi, Piacenza) (cat. no. 21 Giovanetta), Mother and Two Children (Family) (1909/10, Belvedere, Vienna) (cat. no. 22 Famiglia), and The Black Feathered Hat (1910, private collection) (cat. no. 19 Il capello dalla piuma nera). At that time, the painting Portrait of a Woman (Adolescent) still showed the first version: a young girl in a hat and feather stole. The landscape Flowering Meadow (1908, private collection), possibly created during the summer sojourn on Lake Attersee in 1908, was also presented to the public for the first time here.

Fritz Waerndorfer informed Otto Czeschka:

“Klimt is flat broke and did not sell a thing in his retrospective exhibition in Venice.”

This, however, did not comply with the truth. The painting Judith II (Salome) (1909, Ca’Pesaro – Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna, Venice), which had been on view at the “Internationalen Kunstschau Wien 1909” for the first time, was acquired by the Municipal Gallery of Venice for almost 16,000 crowns (approx. 93,000 euros).

Gustav Klimt at Galerie Miethke

At the end of 1910/beginning of 1911, Galerie Miethke presented another one-man show, bearing the plain title: “Gustav Klimt.” As the gallery functioned as Klimt’s principal dealer between 1904 and 1916, it can be assumed that it was first and foremost a sales exhibition. Indeed, only one of the works on display, referred to as “Palace Gardens” in the catalog (not identifiable with absolute certainty) was not for sale, as it already belonged to a private collector. On 24 November, shortly after the opening of the exhibition, The Black Feathered Hat was sold to Rudolf Kahler. Among the eight paintings on view were Klimt’s most recent works, including Portrait of a Woman (Adolescent), which had already been shown in Venice. An article in the newspaper Wiener Zeitung suggested that it was presented in an unfinished state:

“The “Backfisch” [“Adolescent”] will come out just like that [note: the same femme fatale as the one in Portrait of a Lady in Red and Black]. It justifies the ugliest hopes.”

This seems to imply that the first version of Portrait of a Woman (Adolescent) had not yet been completed. In this case, the painting would also still have been unfinished in Venice. However, it would also be thinkable that Klimt had already started overpainting the work, which would have led to its state known today.

International Art Exhibition of Rome 1911

In Rome, a major “International Art Exhibition” was held in the spring of 1911. The opening coincided with the 50th anniversary of the Kingdom of Italy on 27 March. A picture postcard Gustav Klimt wrote to Emma Bacher from Rome, as well as two further postcards to Maria Ucicka indicate that Klimt had traveled to Rome personally to attend the opening of the show. Documents confirm his stay there between 26 and 30 March.

Each of the twelve nations taking part in the show was assigned its own exhibition building in the Vigna Cartoni. The Austrian Pavilion had been built based on plans by Josef Hoffmann. The Genossenschaft bildender Künstler [Vienna Cooperative of Visual Artists], the Vienna Secession, the Hagenbund, and the Klimt Group figured among the participants from Vienna. Gustav Klimt’s paintings were on display in Rooms 4 and 5 (dedicated exclusively to the artist). Except for Death and Life (Death and Love) (1910/11, reworked in 1912/13 and 1916/17, Leopold Museum, Vienna), all of the works on display were by then held by public or private collections.

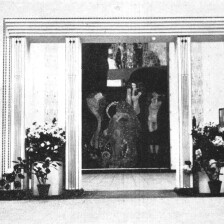

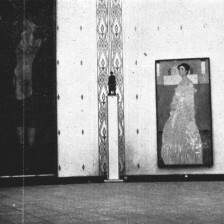

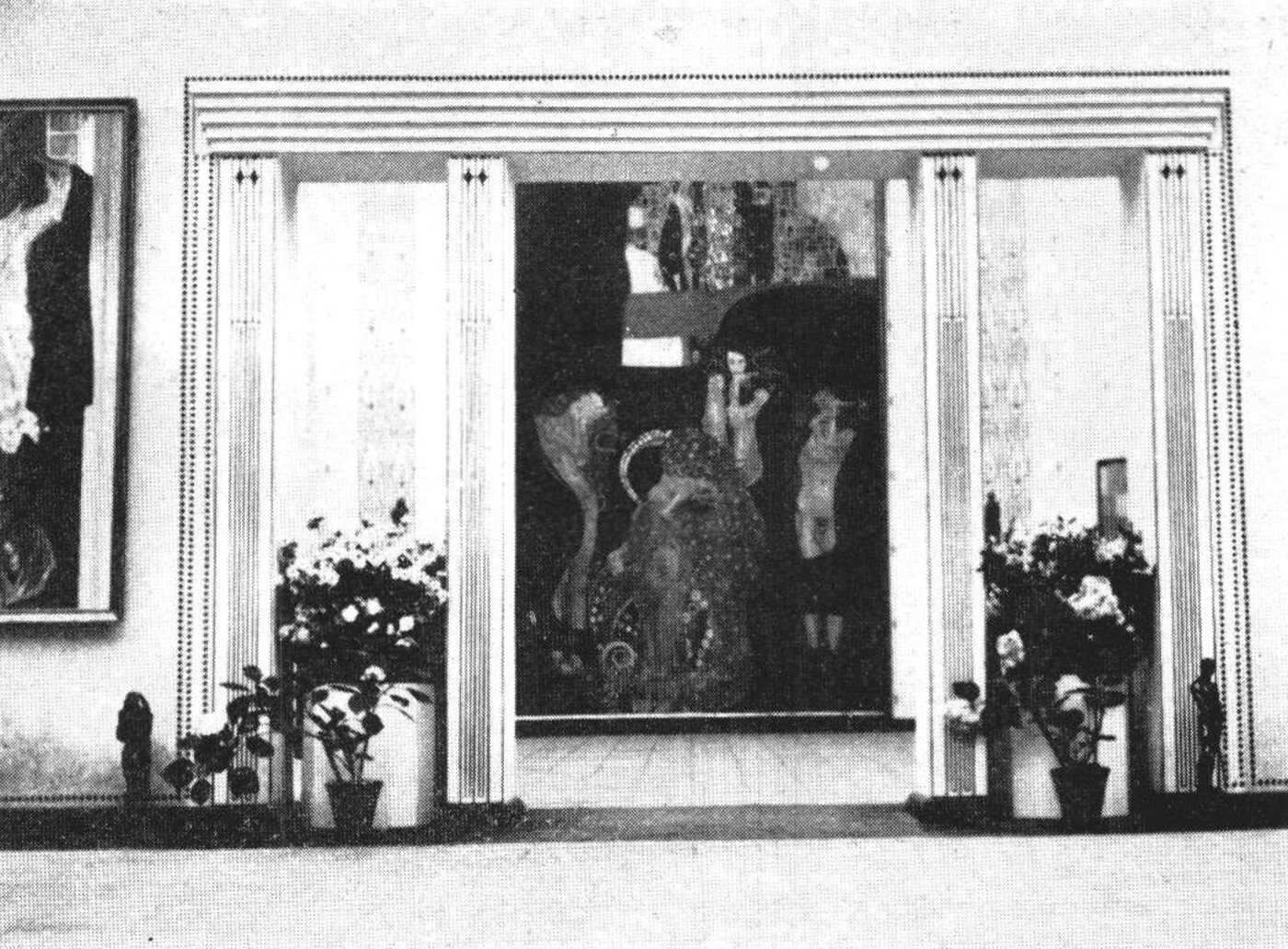

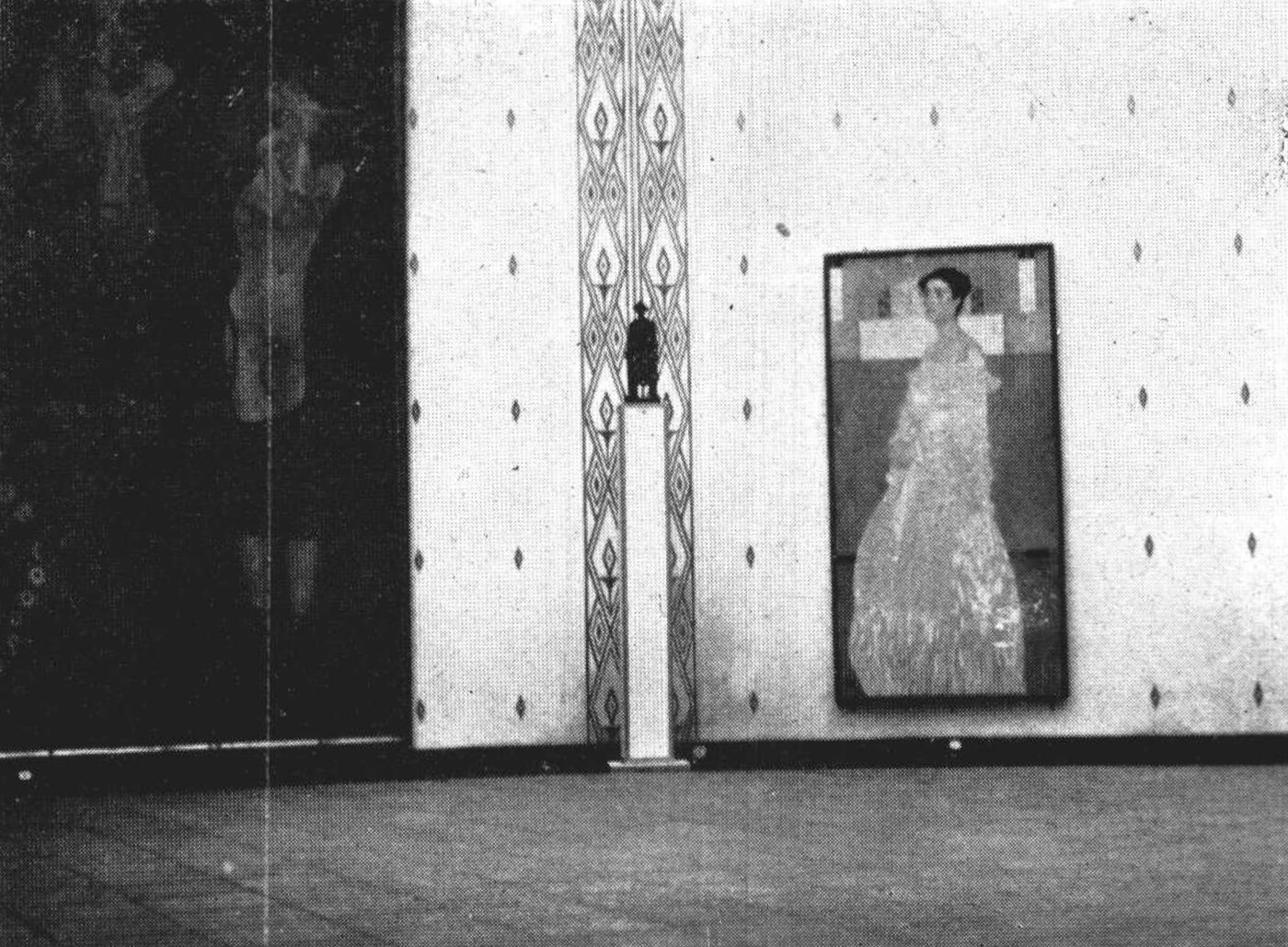

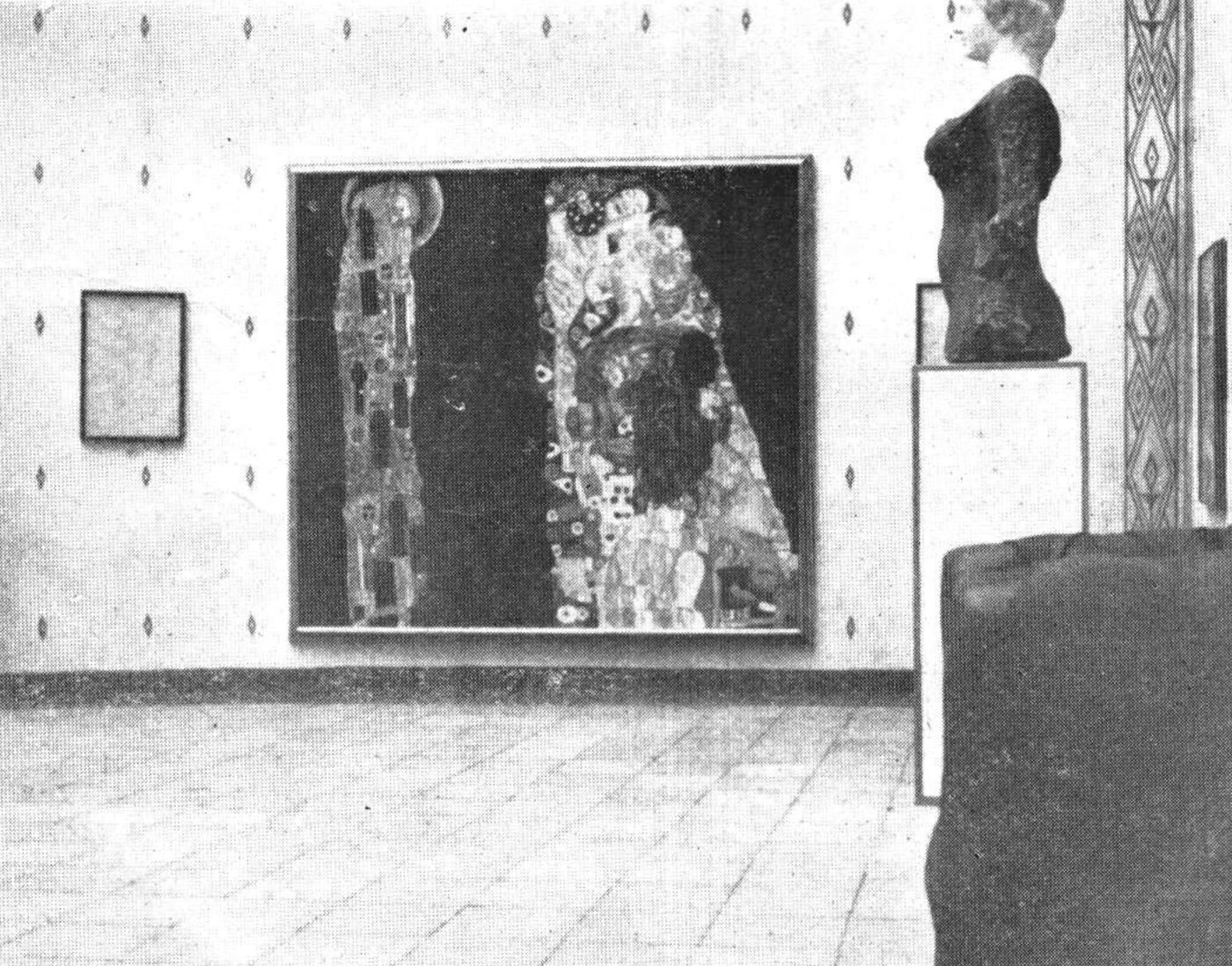

Numerous photographs taken in 1911 document the Austrian Pavilion from the inside and outside. Some of them also show views of the Klimt Room, with Jurisprudence (1903, final version 1907, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945) placed prominently directly opposite the entrance. The series of photographs was published that same year in a special portfolio edited by Verlag Brüder Rosenbaum.

Views of the “International Art Exhibition of Rome 1911”

-

Insight into the International Art Exhibition in Rome, March 1911 - December 1911

Insight into the International Art Exhibition in Rome, March 1911 - December 1911

© ANNO | Austrian National Library -

Insight into the International Art Exhibition in Rome, March 1911 - December 1911

Insight into the International Art Exhibition in Rome, March 1911 - December 1911

© ANNO | Austrian National Library -

Insight into the International Art Exhibition in Rome, March 1911 - December 1911

Insight into the International Art Exhibition in Rome, March 1911 - December 1911

© ANNO | Austrian National Library -

Insight into the International Art Exhibition in Rome, March 1911 - December 1911, Klimt Foundation

Insight into the International Art Exhibition in Rome, March 1911 - December 1911, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Insight into the International Art Exhibition in Rome, March 1911 - December 1911, Klimt Foundation

Insight into the International Art Exhibition in Rome, March 1911 - December 1911, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Insight into the International Art Exhibition in Rome, March 1911 - December 1911, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Archiv

Insight into the International Art Exhibition in Rome, March 1911 - December 1911, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Archiv

© Belvedere, Vienna -

Insight into the International Art Exhibition in Rome, March 1911 - December 1911, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Archiv

Insight into the International Art Exhibition in Rome, March 1911 - December 1911, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Archiv

© Belvedere, Vienna

According to one of the file cards from the archive of Galerie Miethke, the work The Three Ages of Woman (1905, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Rome) was to be sold at the “International Art Exhibition of Rome 1911.” However, this note was later corrected to “sold directly by the artist.” The buyer of the painting was indeed the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Rome. As the painting does not appear in the exhibition catalog and its hanging was not documented in photographs, it seems to have passed into the possession of the Galleria Nazionale before the exhibition began and was thus not presented in the Austrian Pavilion. Correspondence from the Belvedere’s archives reveals that the Italian Ministry of Education was interested in purchasing the painting Portrait of Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein (1905, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen – Neue Pinakothek, Munich) for the Galleria Nazionale in Rome. However, the painting, which was exhibited in the Austrian Pavilion, was then owned by Karl Wittgenstein, who did not agree to sell said painting of his daughter.

That year, the exhibition jury only awarded a single prize in the genre of painting. The Austrian Department entertained great hopes that Klimt should win this prize. Unfortunately, everything turned out to be very complicated. The exhibition had been prolonged beyond its original duration until 20 December, and the jury meeting was not to take place before November. Yet Karl Wittgenstein had only consented to lend the portrait of his daughter until 31 October. However, the painting was one of the most admired objects in the exhibition. As the attempt of the Italian authorities to purchase it had indicated earlier, the work enjoyed great popularity with the Italian audience. Friedrich Dörnhöffer, director of the Modern Gallery in Vienna and Commissioner of the Austrian Department, therefore successfully convinced Karl Wittgenstein to extend his loan until 18 December. Klimt finally won the substantial prize, which came with the amount of 10,000 lire.

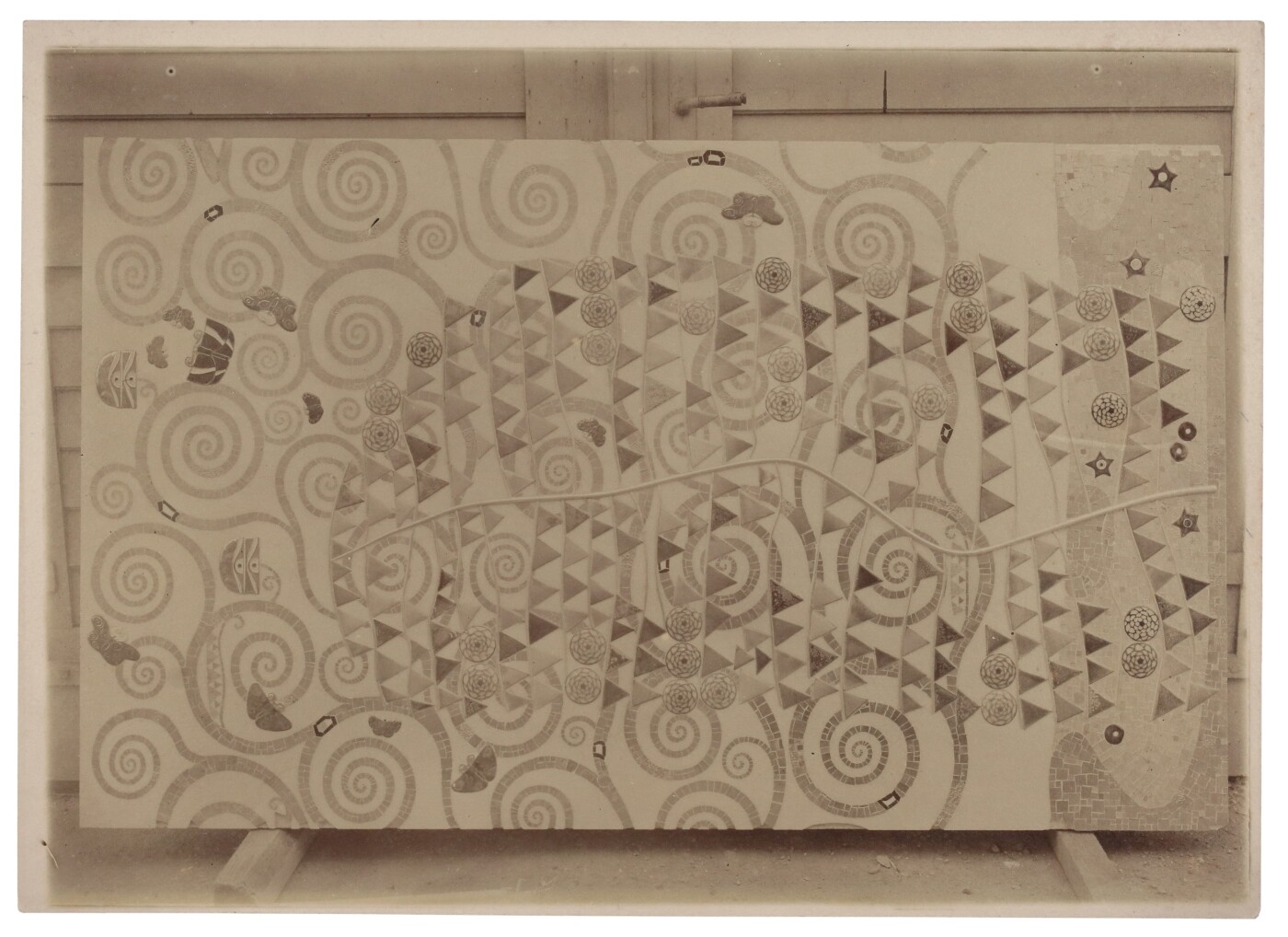

Presentation of the Stoclet Frieze

In October 1911, two panels of the Stoclet Frieze (1905–1911, private collection) were on view for a brief period at Leopold Forstner’s Vienna Mosaic Workshop. The Viennese public should get a chance to see the two panels before they would be delivered to Brussels to be installed in their destination, the dining room of the Stoclet Palace. It was probably because transport of these panels, measuring two by seven meters, should be avoided that they were put up in the workshop where they had been manufactured. Judging from a description in an article that appeared in the Arbeiterzeitung of 29 October, the two panels presented were Dancer and Rosebush. Two photographs show these fragments of the frieze leaning against a door. The pictures, which had probably been taken by Moriz Nähr, seem to have been photographed at Forstner’s workshop shortly before the departure of the two works to Brussels. The two panels were received highly favorably:

“Klimt’s new work cannot be described; it must be seen [...]. The only unfortunate thing about it is that this masterpiece by Klimt is lost to us. Who will commission a similar work from the artist for Vienna?”

Photographs

-

Moriz Nähr (?): The Stoclet frieze (rose bush), October 1911, Klimt Foundation

Moriz Nähr (?): The Stoclet frieze (rose bush), October 1911, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Moriz Nähr (?): The Stoclet Frieze (The Expectation (Dancer)), October 1911, Klimt Foundation

Moriz Nähr (?): The Stoclet Frieze (The Expectation (Dancer)), October 1911, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

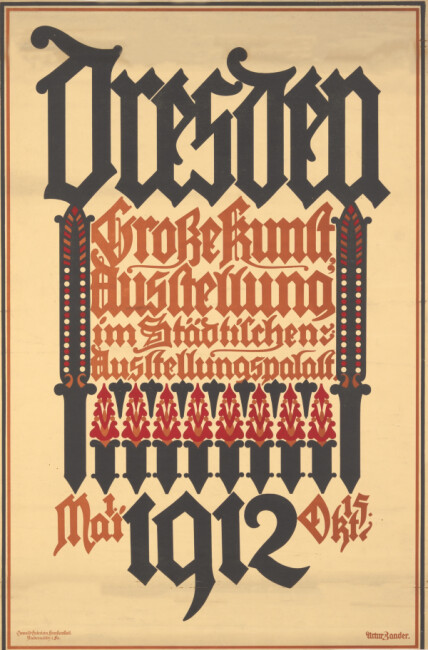

Artur Zander: Poster for the Great Art Exhibition Dresden, 1912,

© Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Foto: Andreas Diesend

Große Kunstausstellung Dresden

From May to October 1912, the “Große Kunstausstellung Dresden” [“Great Dresden Art Exhibition”] took place at the Municipal Exhibition Palace of the City of Dresden. Next to German artists’ associations like the Munich and the Berlin Secessions and the Dresdner Kunstgenossenschaft [Dresden Art Cooperative], Austria was the only other country that was given a section of its own. Gustav Klimt exhibited altogether nine paintings in three different sections. The majority of the paintings, including two unidentified portraits, were hung in Room 50 in the Department of Monumental and Decorative Painting. Birch Forest (Beech Forest) (1903, Paul G. Allen Family Collection) is listed to have been installed in this room in the first edition of the catalog under cat. no. 1833. In the third edition, however, the painting was inserted under number 1524a in Room 32 of the Austrian section, which comprised altogether three rooms – after a painting by Franz Jäger. The work thus appears to have been relocated while the exhibition was already on, probably to ensure that at least one painting by Klimt would be on view in the Austrian section. Beech Forest I was purchased during the exhibition for 8,460 crowns (approx. 48,600 euros) by the Staatliche Kunstsammlung Dresden. Portrait of Emilie Flöge (1902, Wien Museum, Vienna) (cat. no. 1930, “Portrait of a Lady”) was likewise hung in a special section devoted to female portraits (Room 49).

Exhibition of the Austrian Artists’ League in Budapest

The following year, an exhibition was organized in Budapest at the local Künstlerhaus (Művészház). It had been initiated by the Austrian Artists’ League, an association founded in 1912, as an exhibition specifically devoted to Gustav Klimt: “Bund Österreichischer Künstler és Gustav Klimt. Gyüjteményes, kiállitása” [“The Austrian Artists’ League and Gustav Klimt. Collective Exhibition”]. It was the first independent show of Viennese artists in Hungary and the third Klimt collective exhibition held abroad within three years.

In the last room of the exhibition, ten paintings and as many drawings by Klimt were on view. It was for the very first time that Klimt presented his monumental work The Virgin (1913, Národní Galerie, Prague) (cat. no. 23 Panna). The price of the painting amounted to the substantial sum of 25,000 crowns (approx. 142,400 euros). Only one other painting, entitled Halálfélelem (which freely translates as “Fear of Death”), was offered for the same amount: it might have been the work Death and Life (Death and Love) (1910/11, reworked in 1912/13 and 1916/17, Leopold Museum, Vienna). A note to Emilie Flöge of 4 March, in which Klimt writes that he was hassling “fearlessly with the dead,” seems to imply that the work had been reworked for the first time even before the exhibition started on 8 March. These two works were the most expensive paintings by far in the whole show.

As Klimt informed Emilie, he attended the opening in person. It seems that the exhibition was not very successful, for on 6 March he wrote:

“I don’t hear anything from Pest [Budapest] – nothing at all – not much happening around here, as it seems – just the way I thought it would be.”

It is hard to say if this was to refer to the number of attendance or the sales figures.

Exhibition Year 1913

In May that same year, the German Artists’ League invited participation to its “3rd Exhibition” in Mannheim. Gustav Klimt, who had already taken part in the association’s first two shows, was represented with altogether three works, including Death and Life (Death and Love). He sent six paintings, including the new work The Virgin, to the “XI. Internationale Kunstausstellung im Königlichen Glaspalast zu München” [“11th International Art Exhibition at the Royal Glass Palace in Munich”] of 1913, which was on at the same time.

Literature and sources

- Città di Venezia (Hg.): IX. Esposizione internazionale d‘arte della città di Venezia. Catalogo, Ausst.-Kat., Austrian Pavilion (Venice), 22.04.1910–31.10.1910, 3. Auflage, Venice 1910.

- Galerie H. O. Miethke (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. November-Dezember 1910. Galerie Miethke Wien, 1. Dorotheerg. 11, Ausst.-Kat., Gallery H. O. Miethke (Vienna), 23.11.1910–18.12.1910, Vienna 1910.

- Friedrich Dörnhöffer (Hg.): Internationale Kunstausstellung Rom 1911. Österreichischer Pavillon, Ausst.-Kat., Austrian Pavilion (Rome), 27.03.1911–20.12.1911, Vienna 1911.