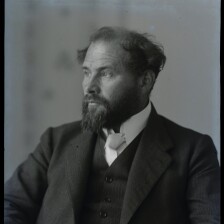

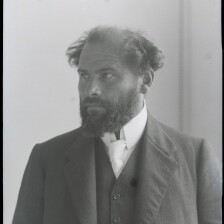

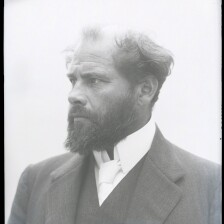

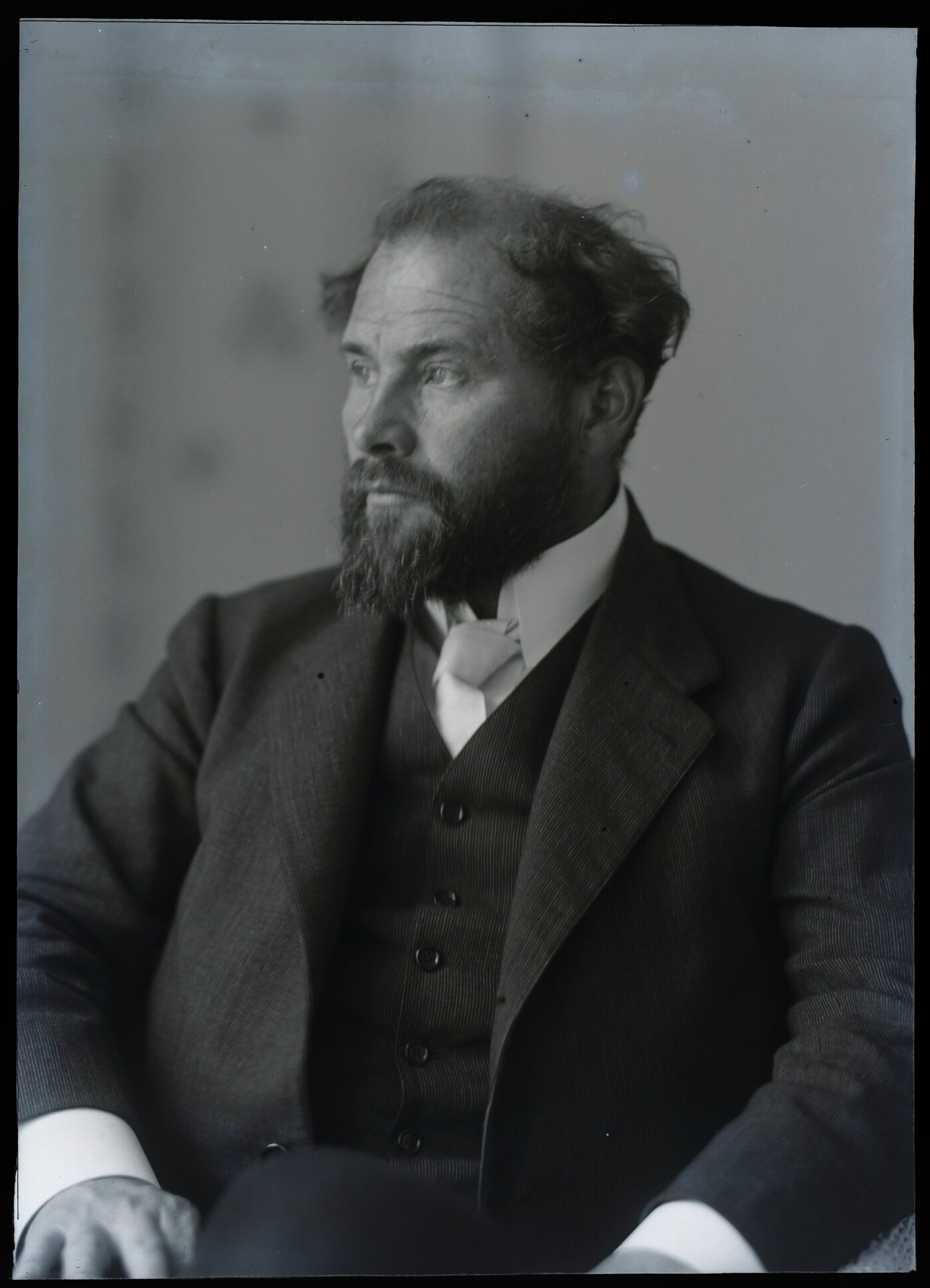

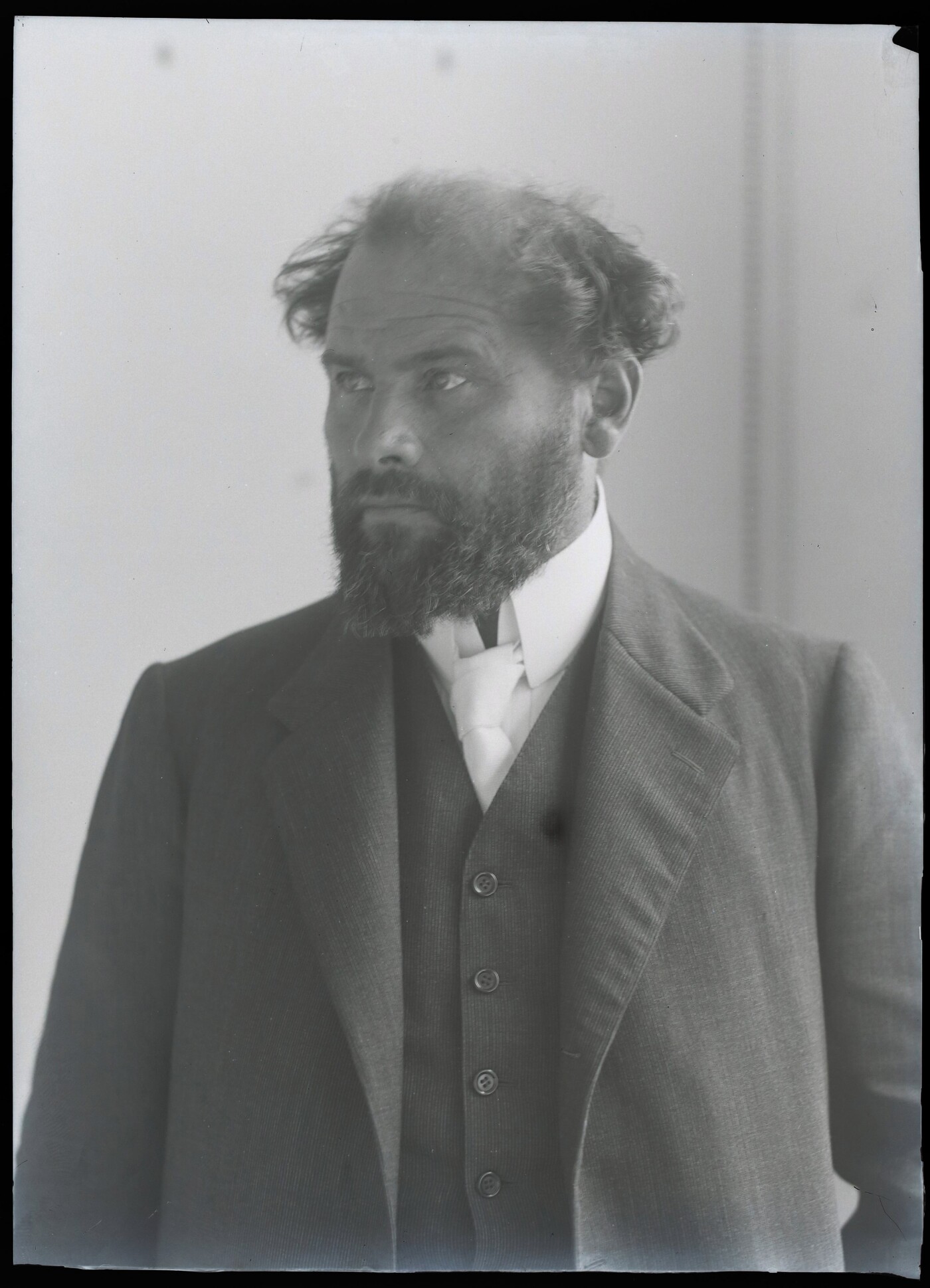

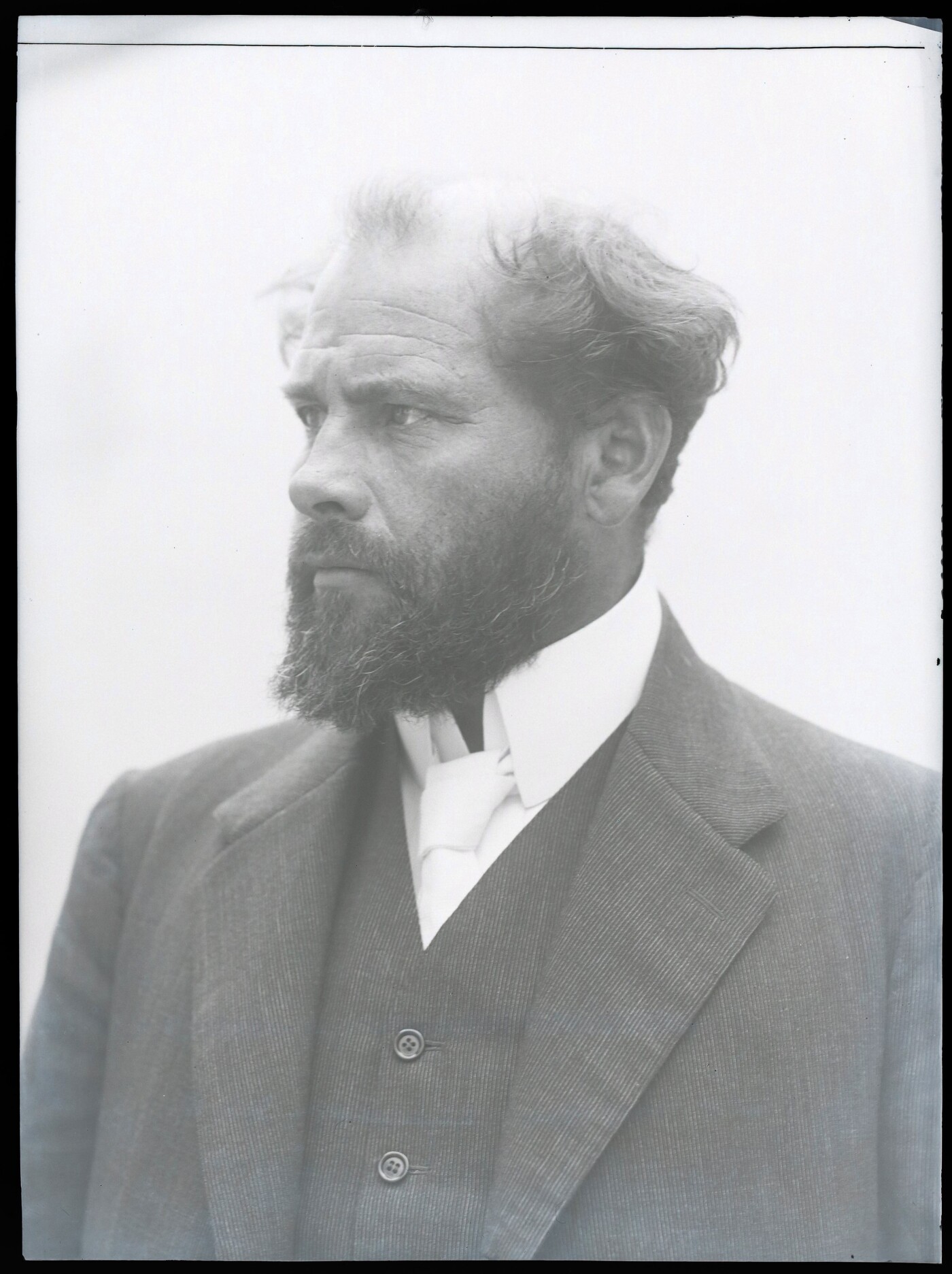

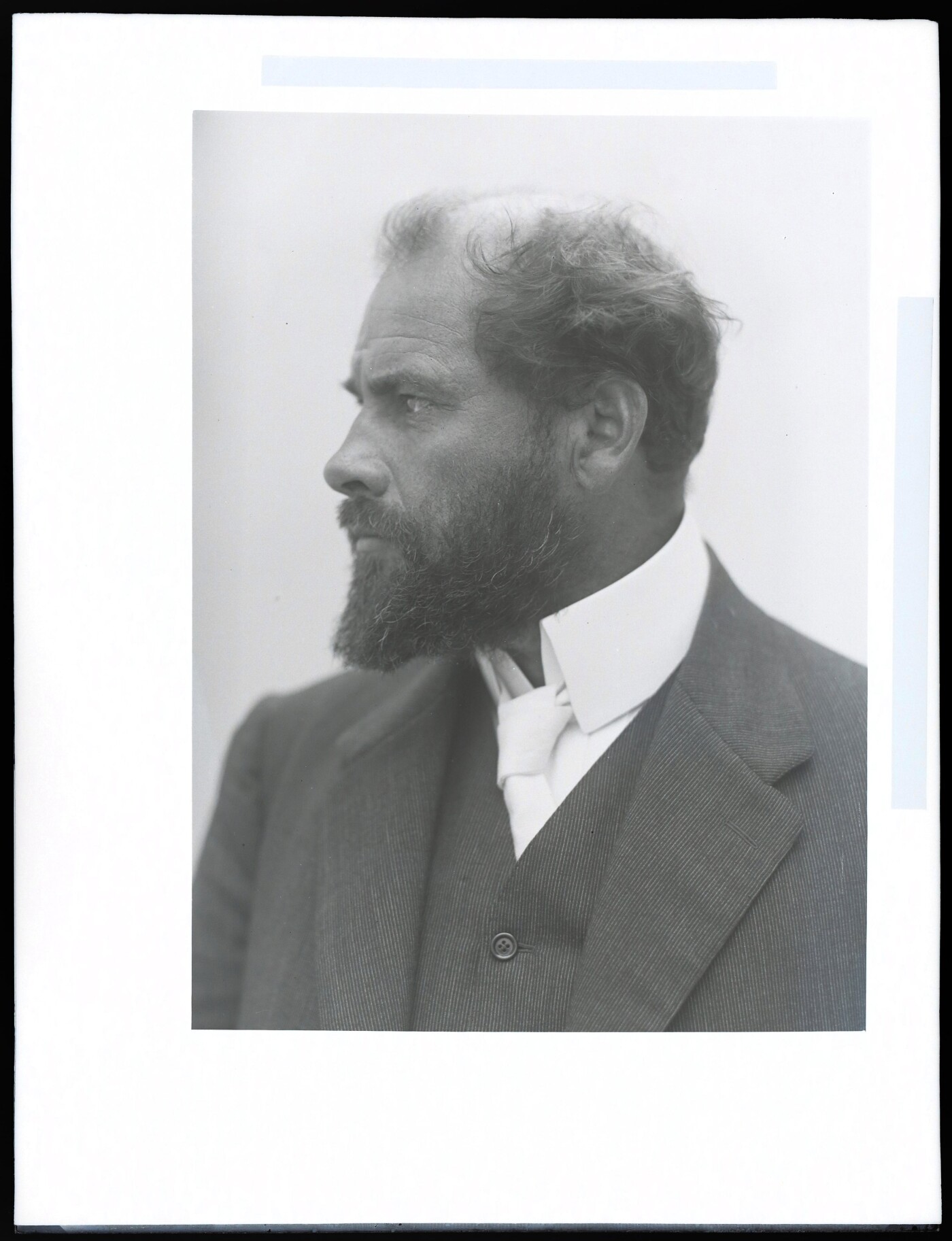

Klimt's work focuses on all aspects of the Art Nouveau master's oeuvre. Visualized through a timeline, Klimt's creative periods are rolled up here, starting with his training, his collaboration with Franz Matsch and his brother Ernst in the "Künstler-Compagnie", the affair surrounding the faculty paintings and his post-fame and the myth that still surrounds this exceptional artist today.

Gustav Klimt at His Zenith

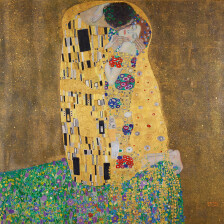

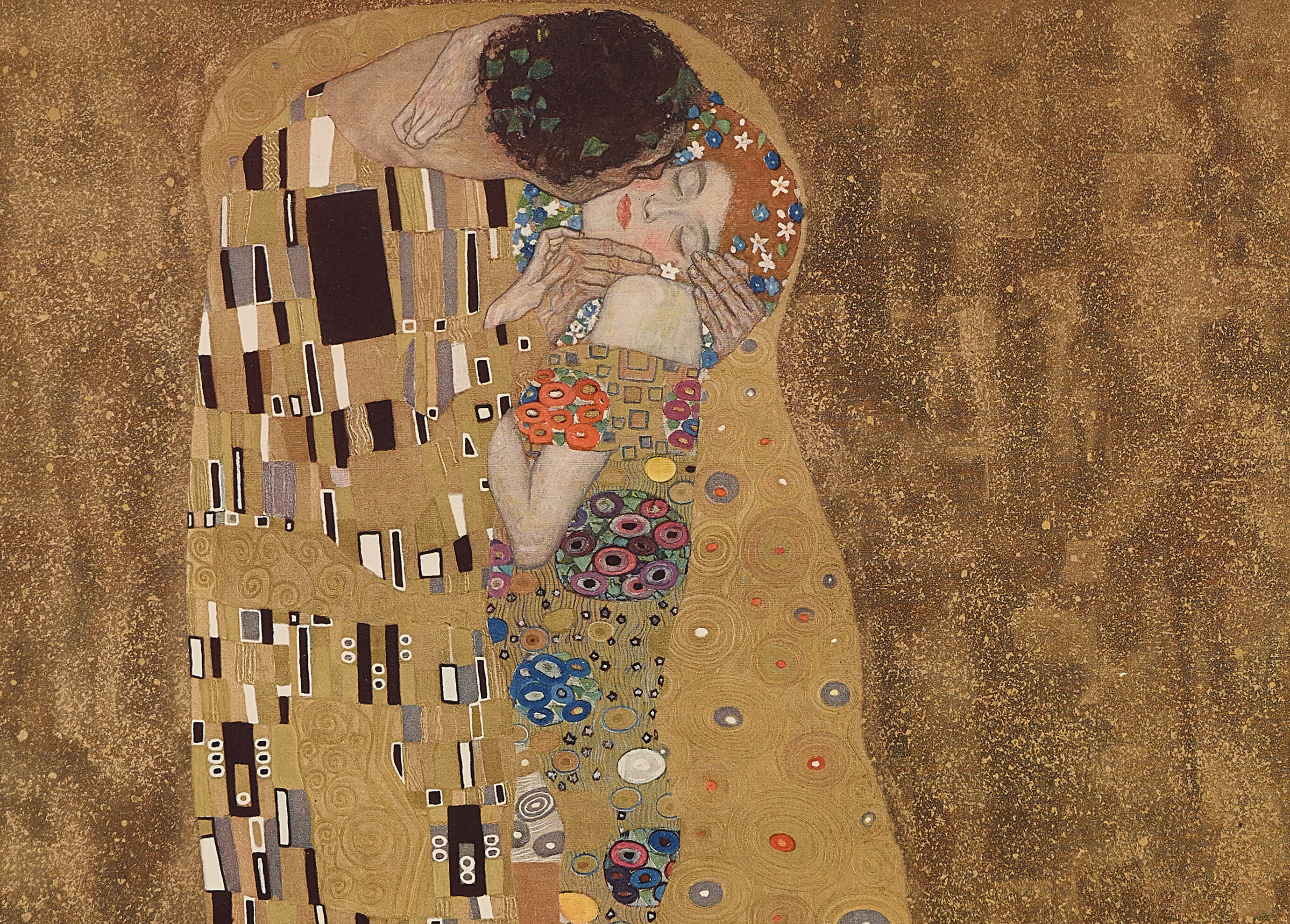

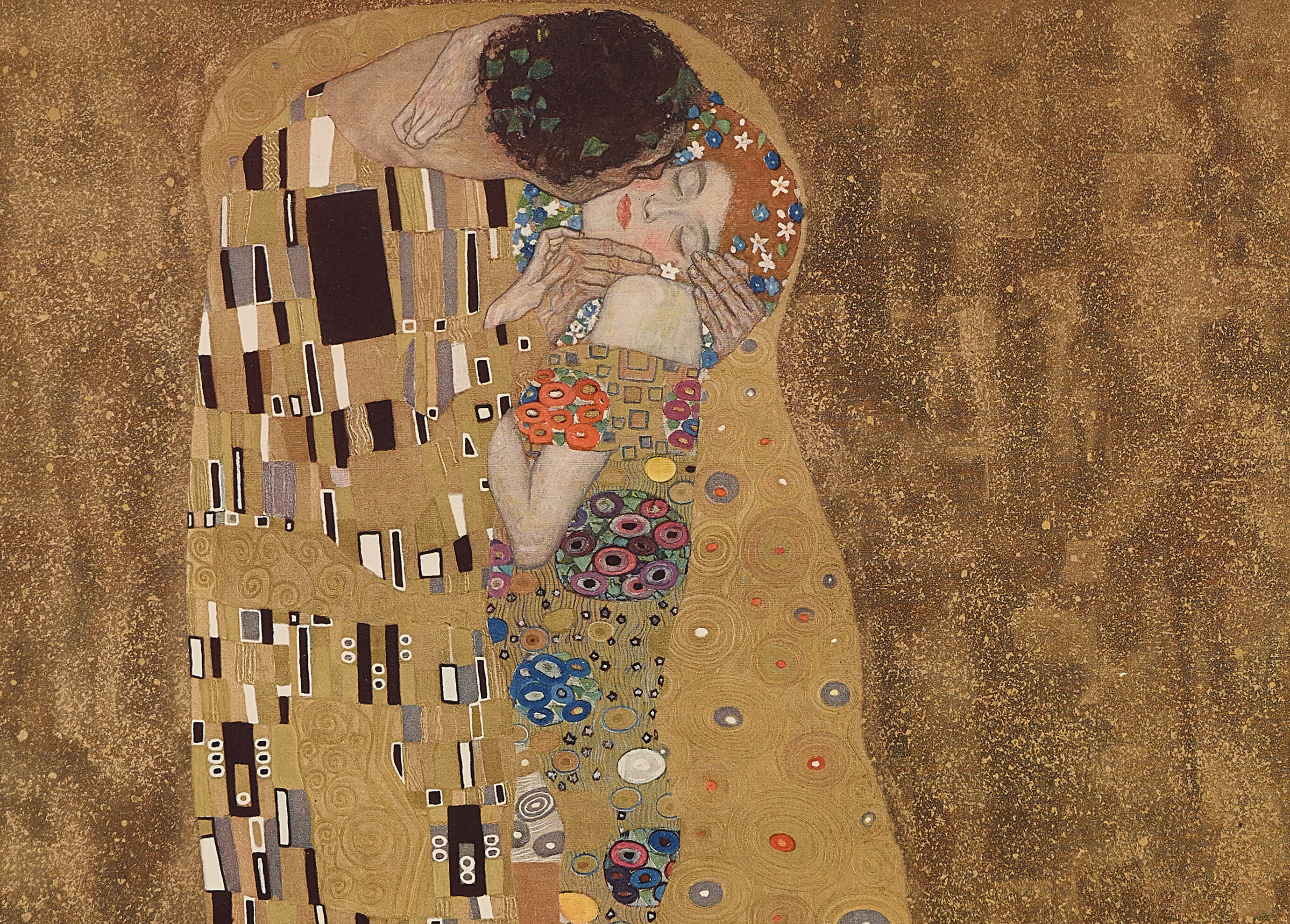

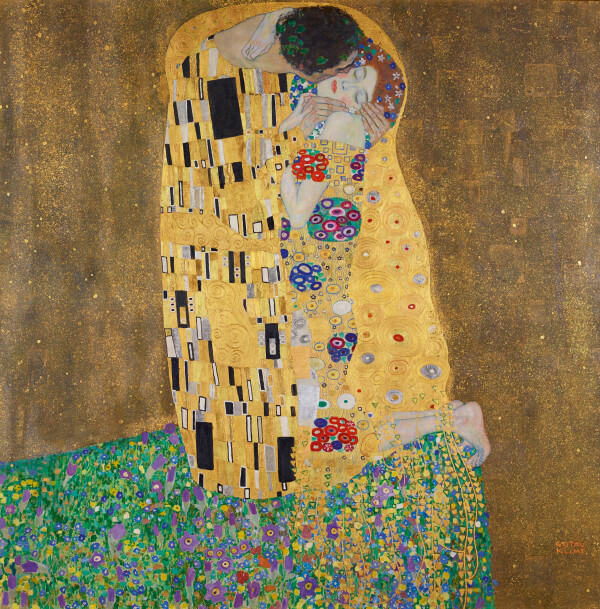

The oil paintings created between 1907 and 1909 date from the height of Klimt’s Golden Period: first of all, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I and the monumental icon The Kiss (Lovers). At this time, Klimt also worked on the frieze for the Stoclet Palace in Brussels. What is more, the Klimt group organized two of the most important and comprehensive exhibitions of Viennese Modernism, the "Kunstschau Wien 1908" and the "Internationale Kunstschau 1909".

→

Gustav Klimt: The Kiss (Lovers), 1908/09, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

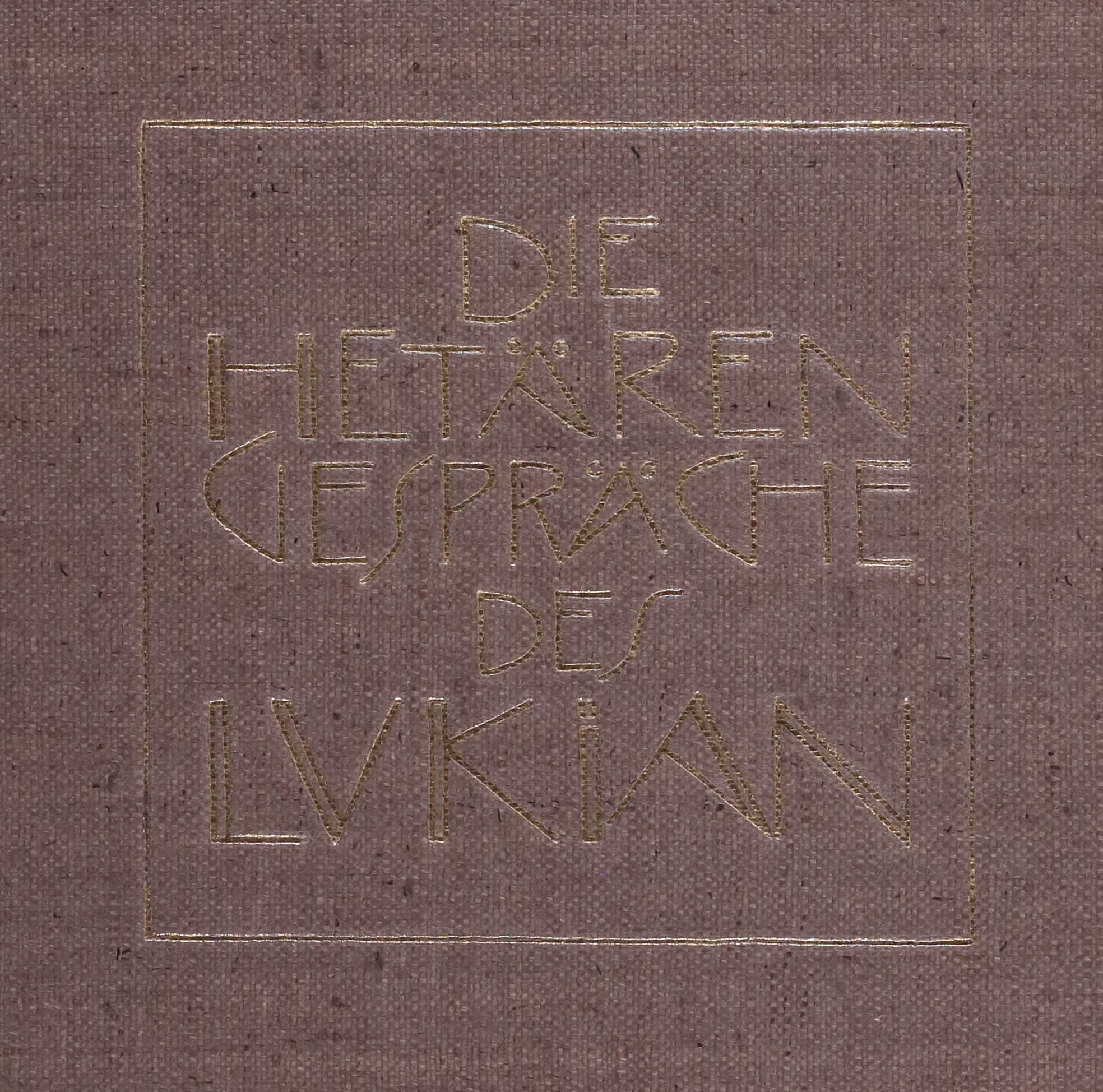

Lucian’s Dialogues of the Courtesans

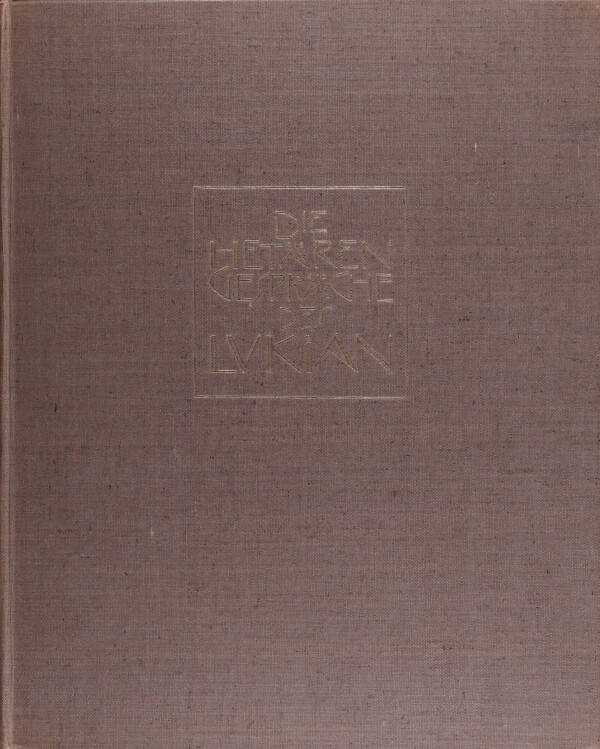

The luxury volume of Lucian’s Dialogues of the Courtesans was published by Julius Zeitler in 1907. Franz Blei supplied the German translation of the Dialogues by the late antique writer Lucian of Samosata; 15 erotic drawings by Gustav Klimt were integrated as collotype plates, and the Wiener Werkstätte produced the bindings of the luxurious special editions.

To the chapter

→

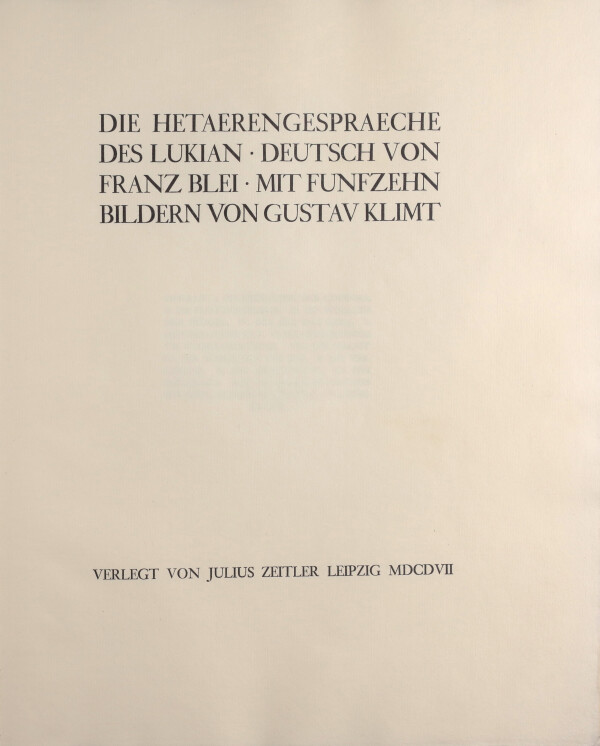

Edition C, cover title, in: Franz Blei (Hg.): Die Hetärengespräche des Lukian, Leipzig 1907.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Highlights of the Golden Period

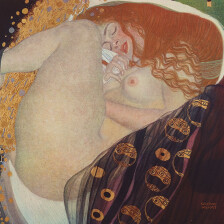

Some of Gustav Klimt’s most prestigious masterpieces were created in the years between 1907 and 1909. In his paintings The Kiss (Lovers) and Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II, he carried the effect of gold to its height. In his works Hope II, Danaë, and Judith II, he dealt with the image of women around 1900.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: The Kiss (Lovers), 1908/09, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

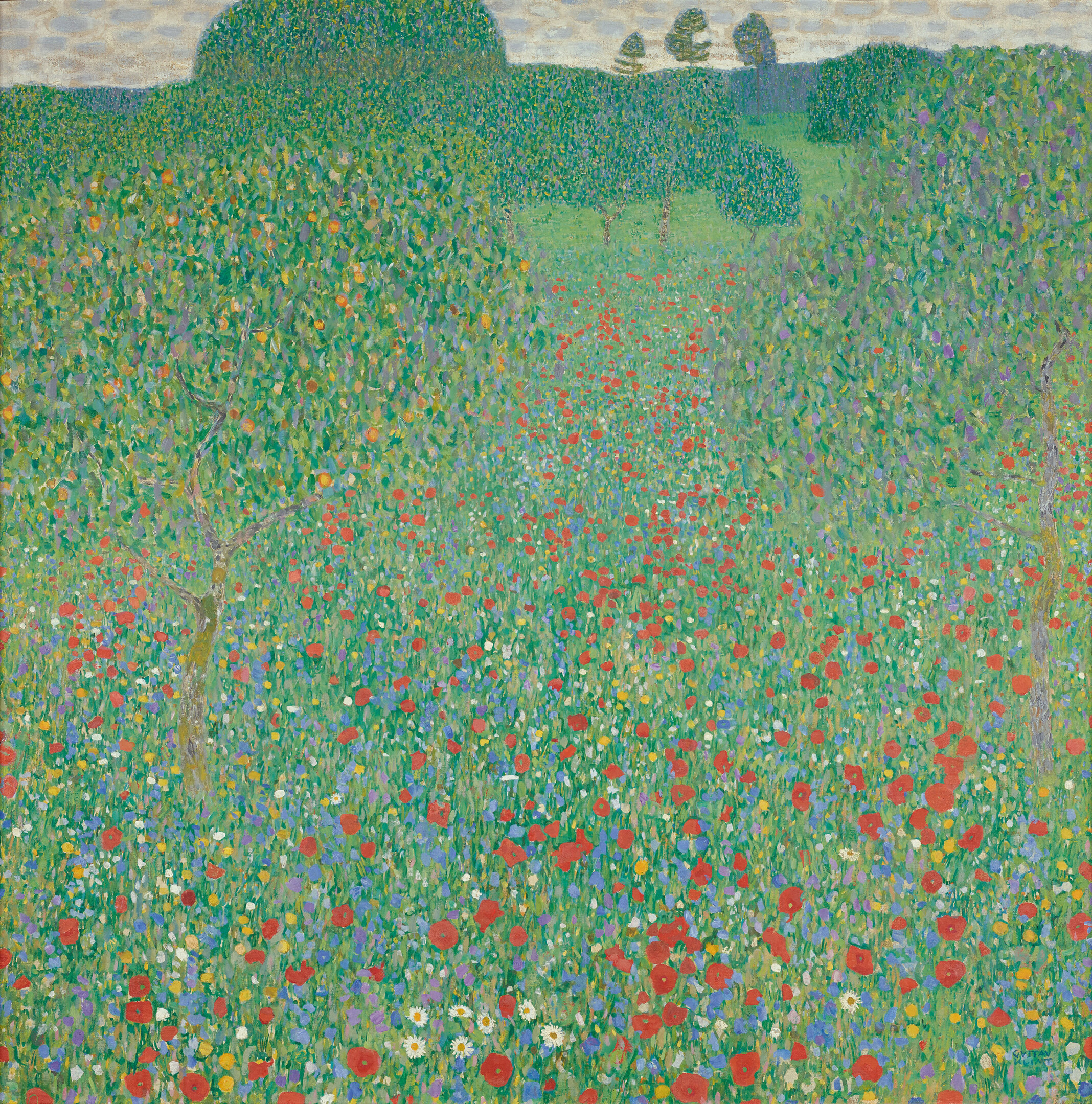

Floral Mosaics Continued

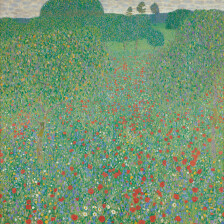

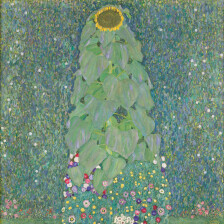

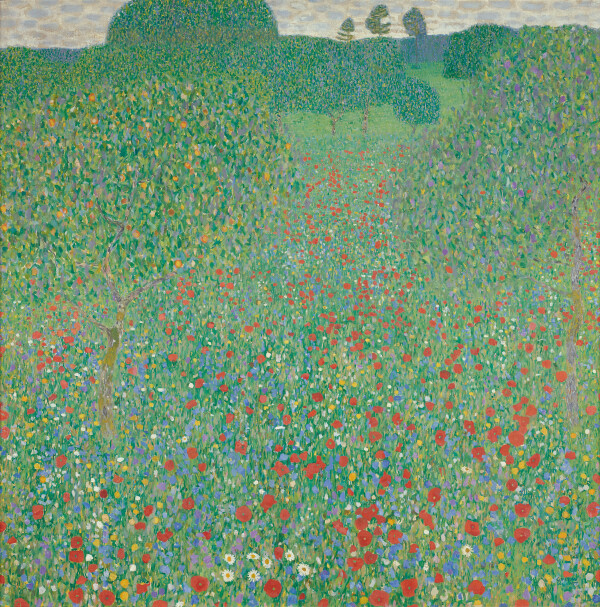

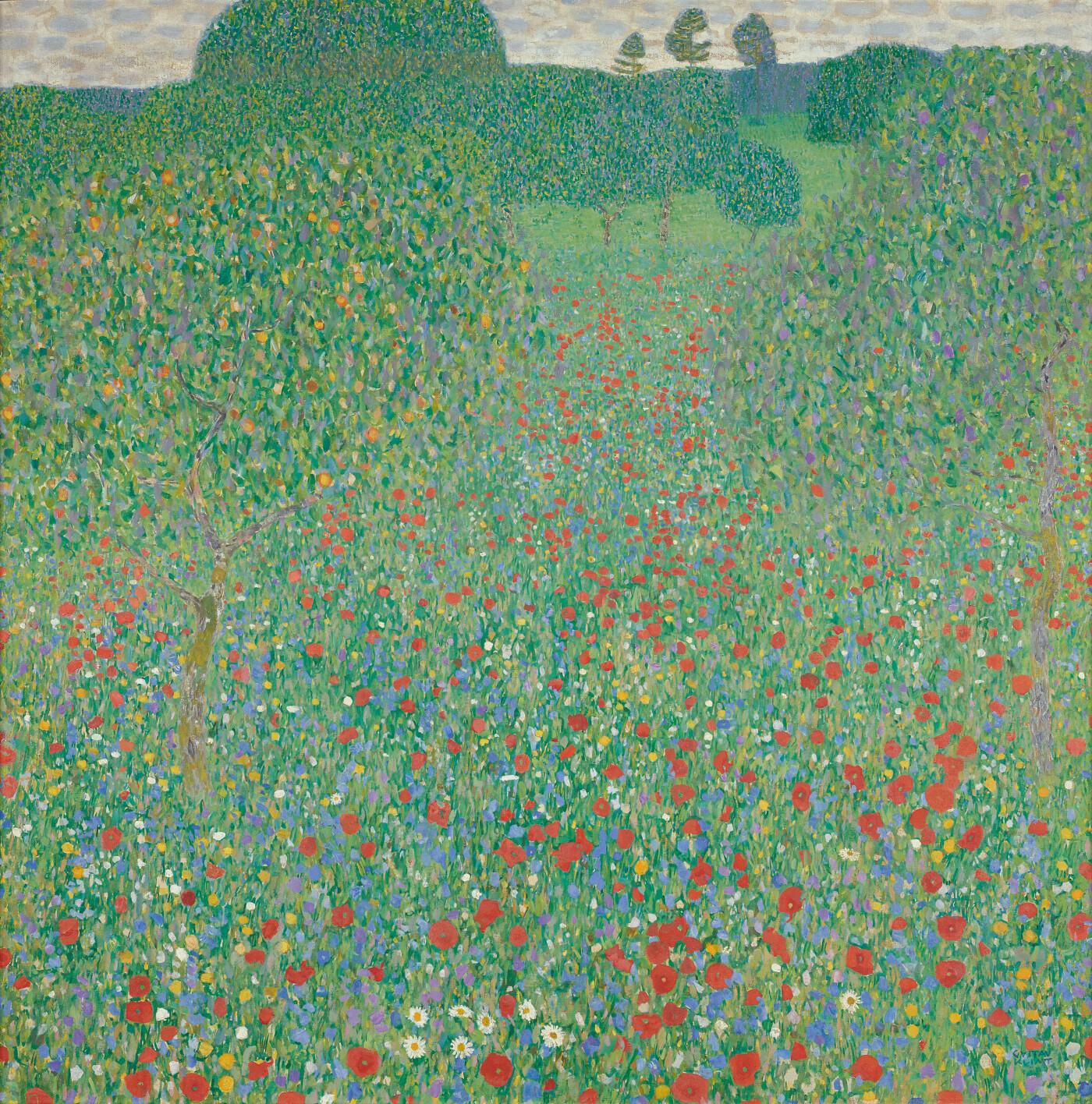

In 1907 Gustav Klimt completed another three landscape paintings with which he paid tribute to the floral splendor around the Attersee. The sunflower in particular inspired him in his homage to the beauty of nature. The motif of the wild meadow had once again made its way into Klimt’s work.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Poppies in Bloom, 1907, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

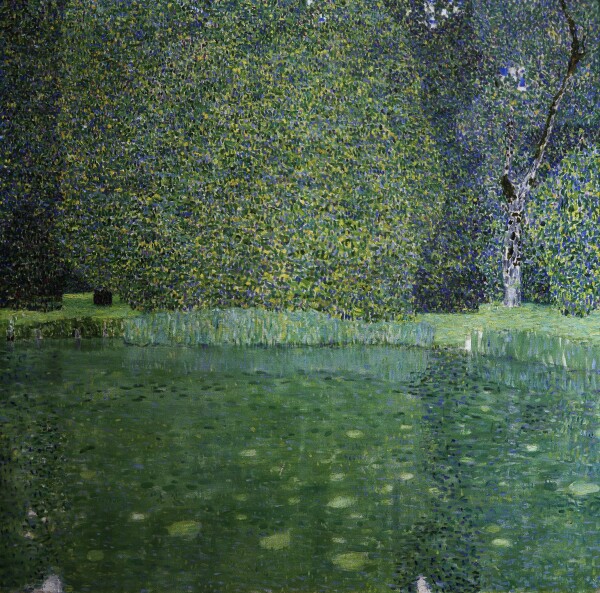

Views of Kammer Castle on the Attersee

Between 1908 and 1912, Klimt stayed at the Villa Oleander in Kammerl, which was part of the district of Kammer-Schörfling, for his summer vacation. Several views of the formerly moated Kammer Castle date from this period. In them, Klimt gradually translated the multifaceted image of nature into a stylized, flickering pictorial order.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Kammer Castle on the Attersee I, 1908, Národní Galerie

© National Gallery Prague

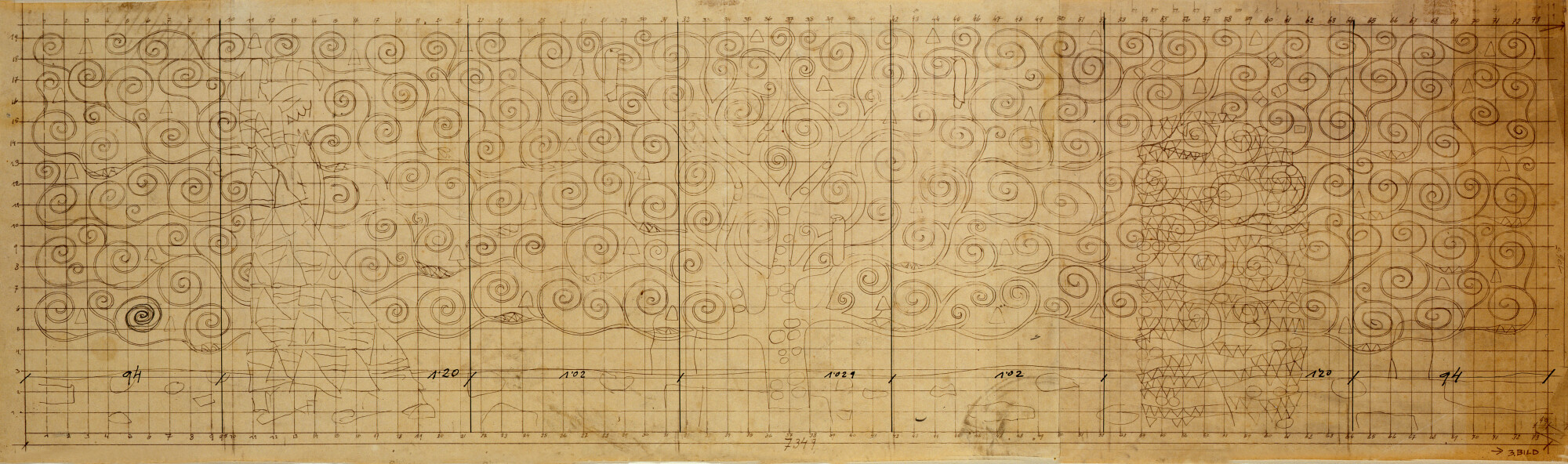

The Stoclet Frieze. Sketches

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt on the site of the Palais Stoclet in Brussels, 05/09/1906, MAK - Museum für angewandte Kunst, Archiv der Wiener Werkstätte

© MAK

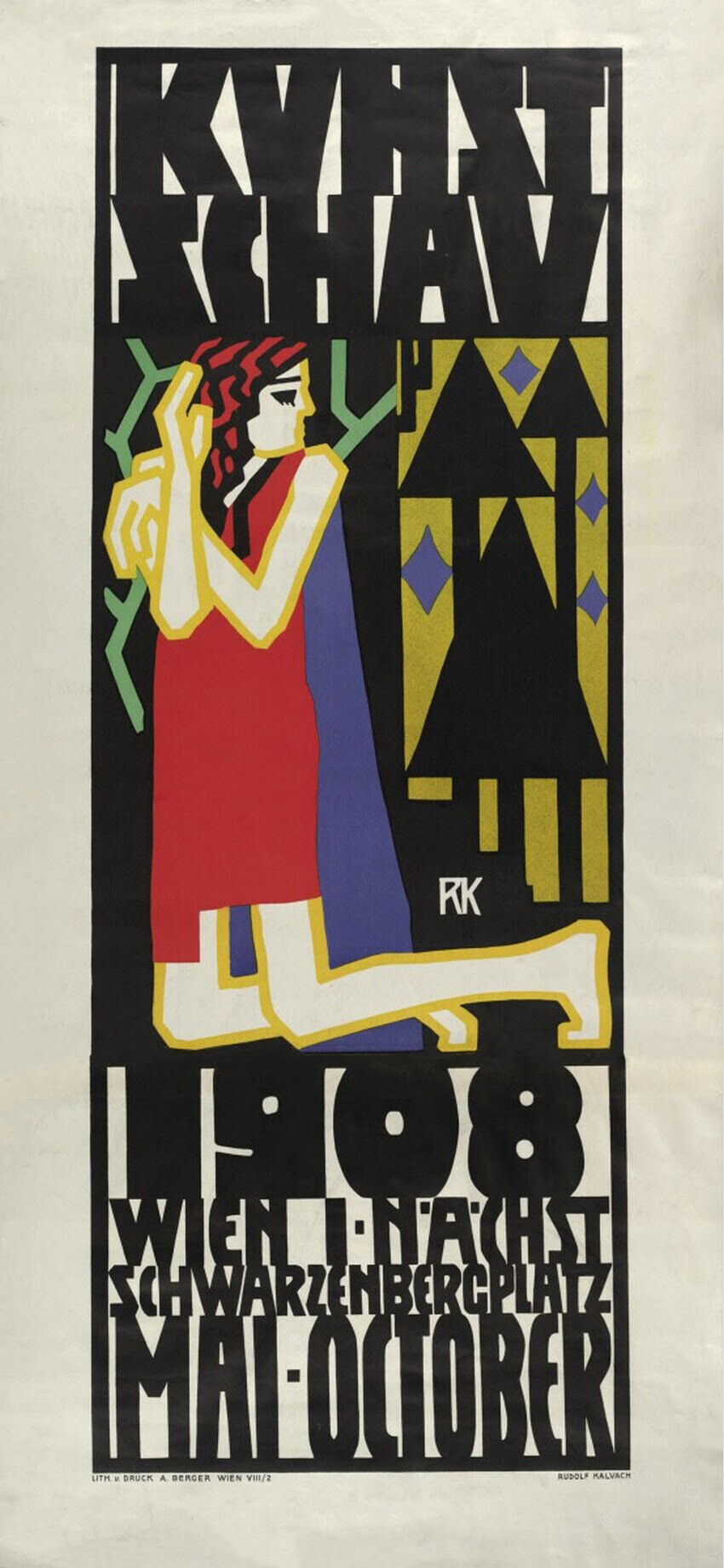

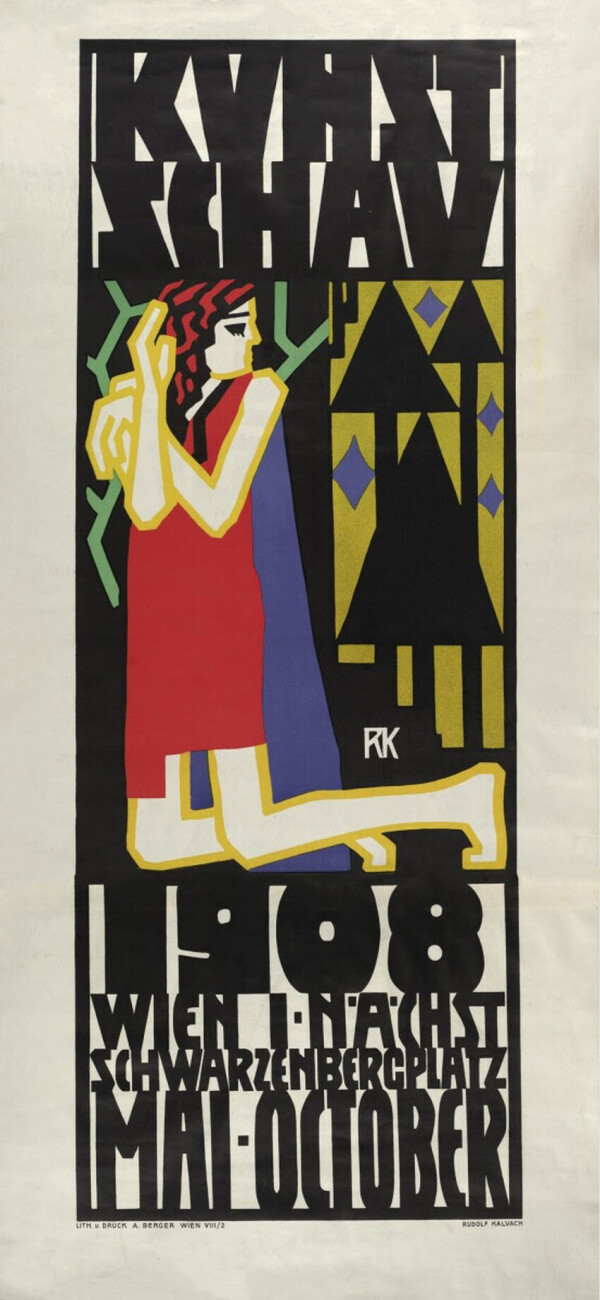

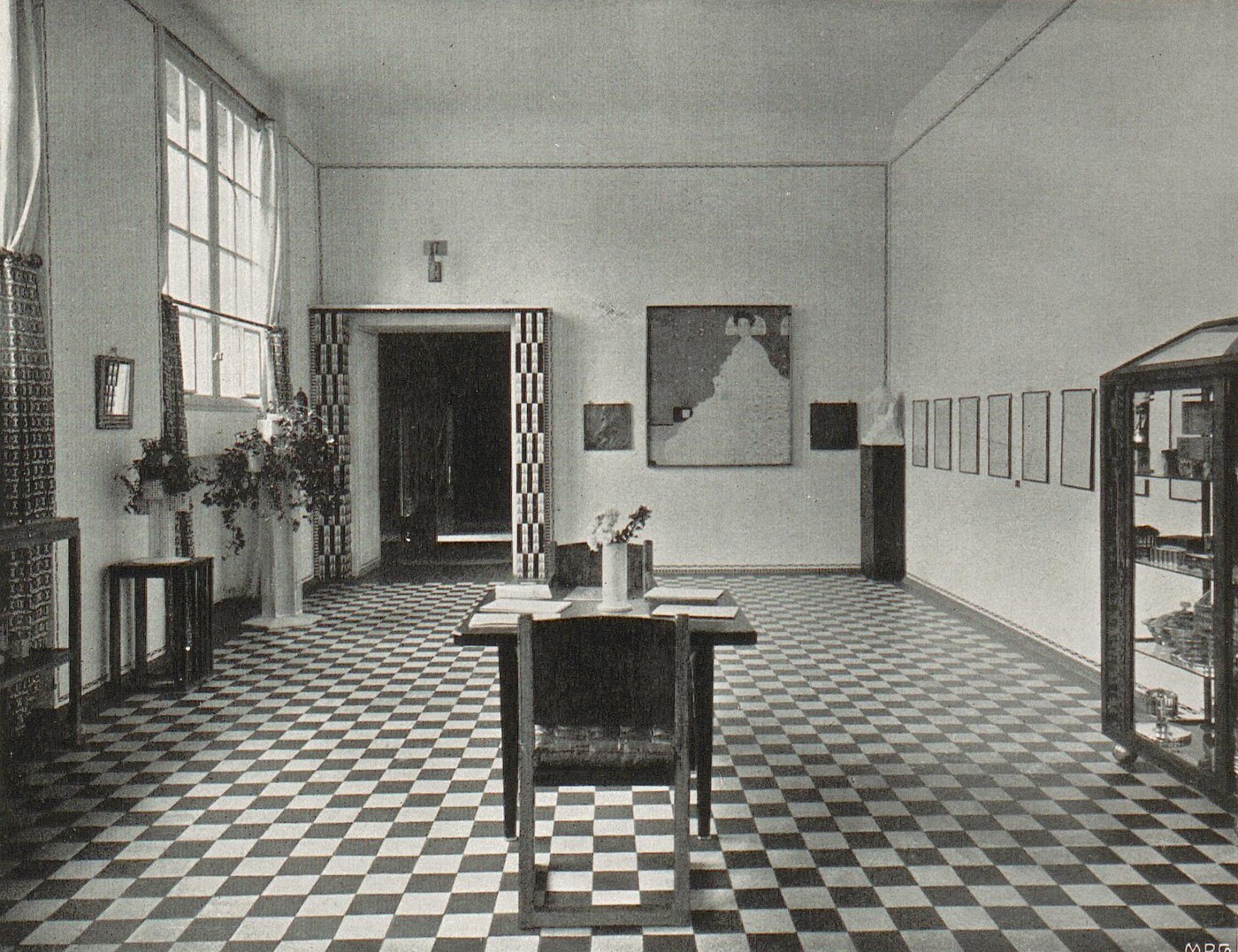

Kunstschau Wien 1908

At the “Kunstschau Wien 1908” Gustav Klimt exhibited 16 oil paintings and 18 drawings in three rooms. As president of the so-called Klimt Group, he was significantly involved in the show’s organization and program. Having sold four paintings, Klimt was one of the most successful artists of this large-scale exhibition.

To the chapter

→

Rudolf Kalvach: Poster of the Vienna Art Show 1908

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

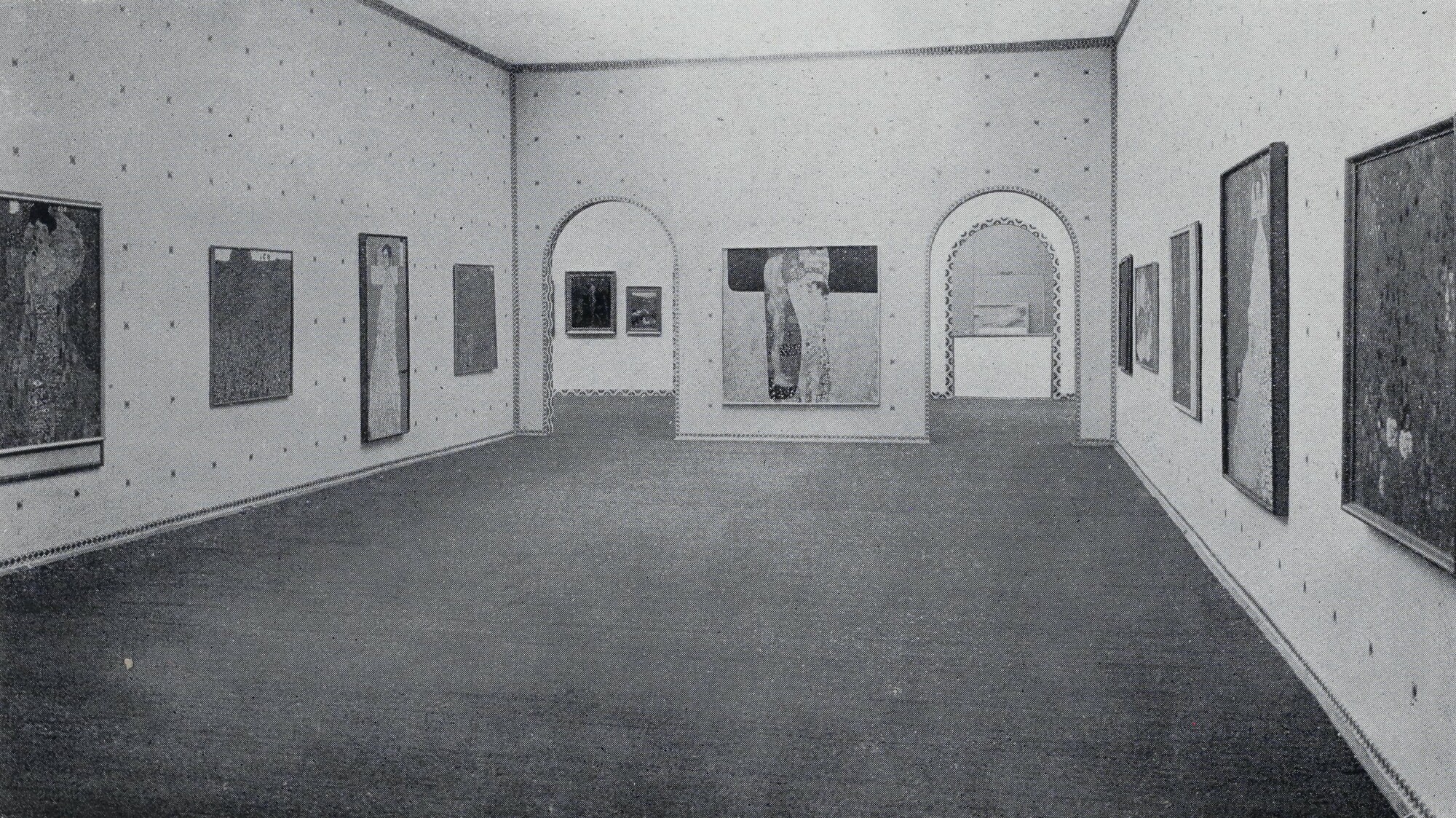

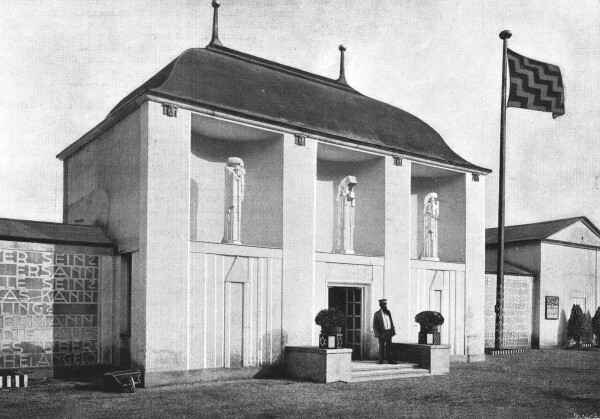

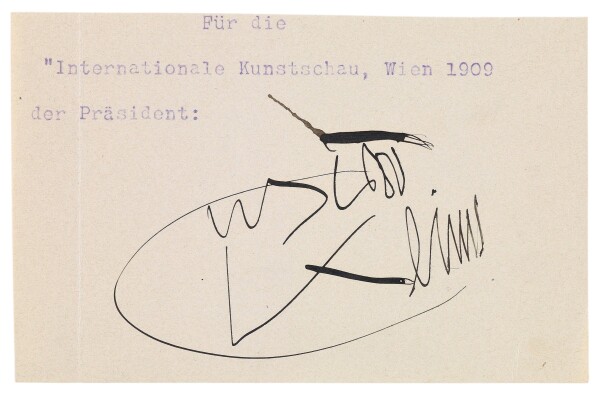

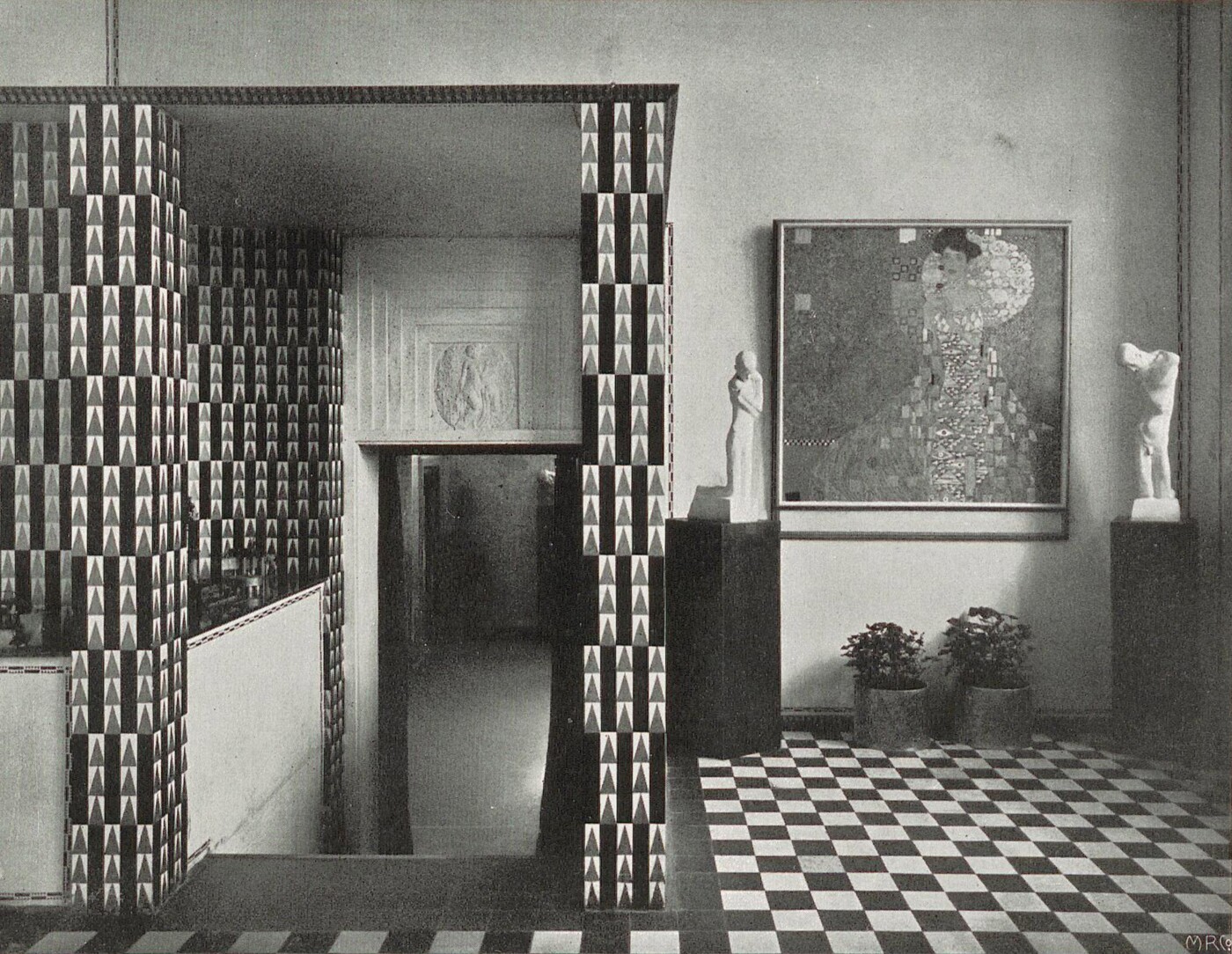

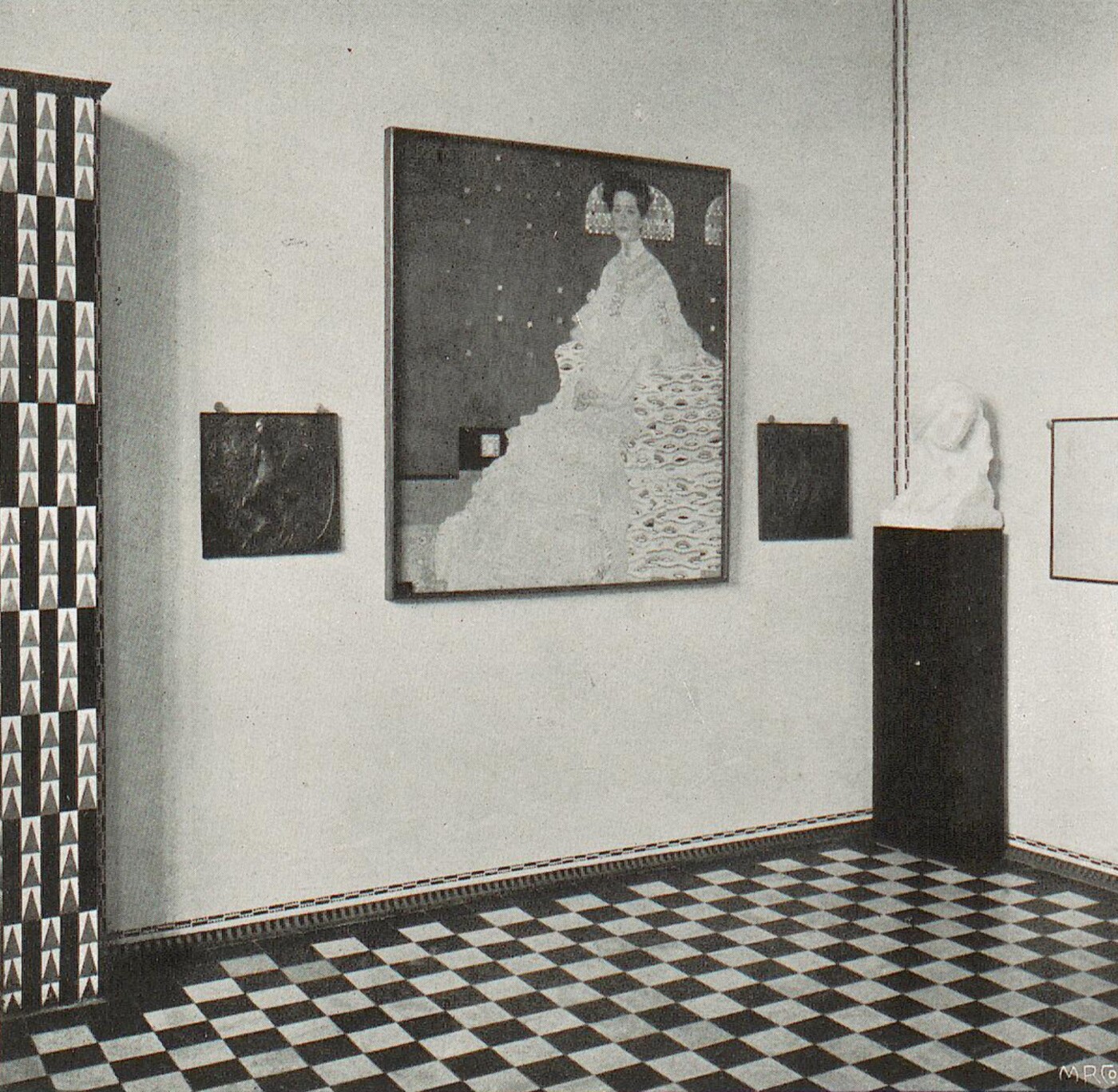

Internationale Kunstschau Wien 1909

The “Internationale Kunstschau Wien 1909” initiated by the Klimt Group brought together the leading artists of the early 20th century. In the exhibition building designed by Josef Hoffmann, Gustav Klimt presented seven paintings in the context of works by Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Max Liebermann, Henri Matisse, and Edvard Munch.

To the chapter

→

Bertold Löffler: Poster of the International Art Exhibition 1909

© gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

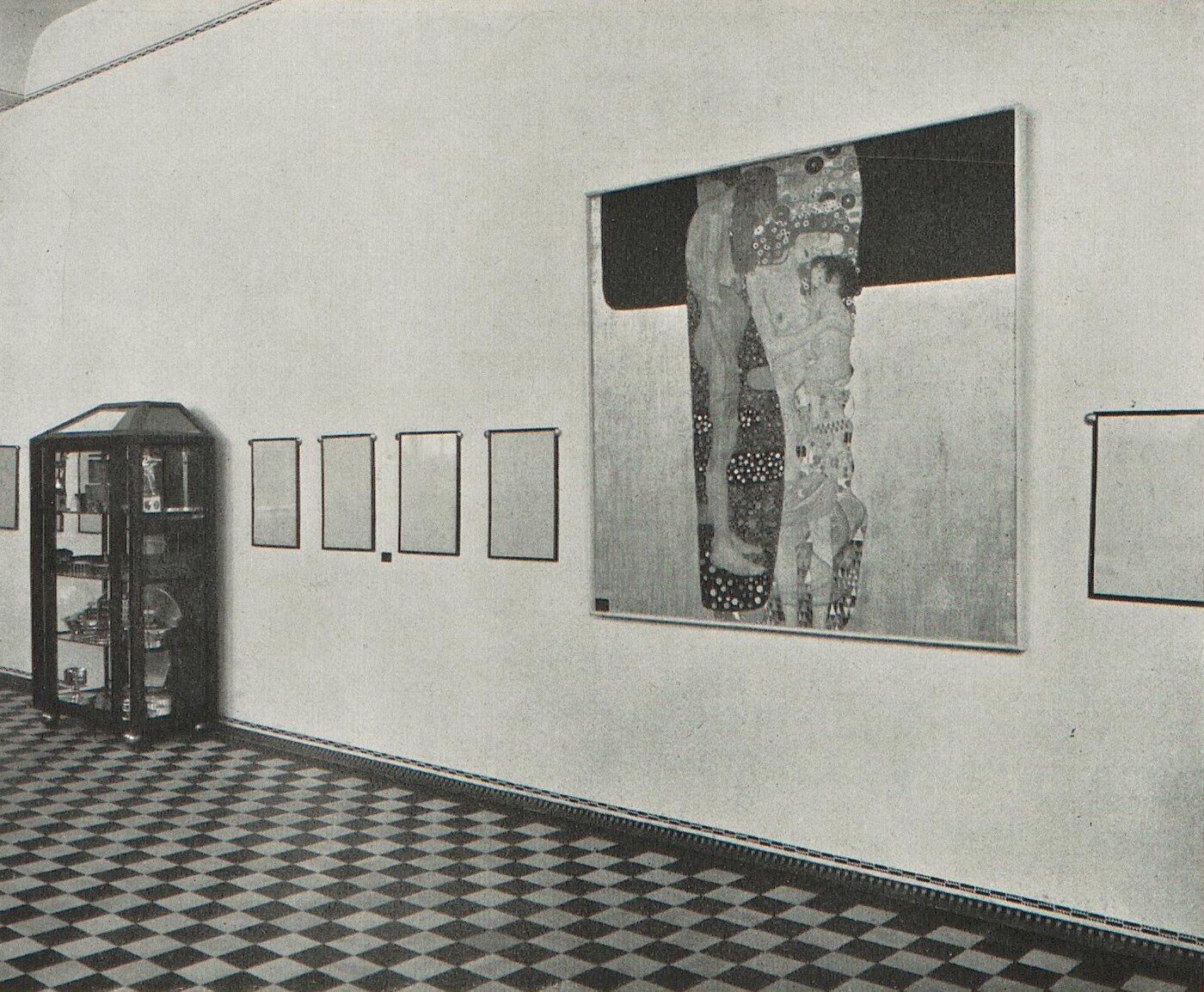

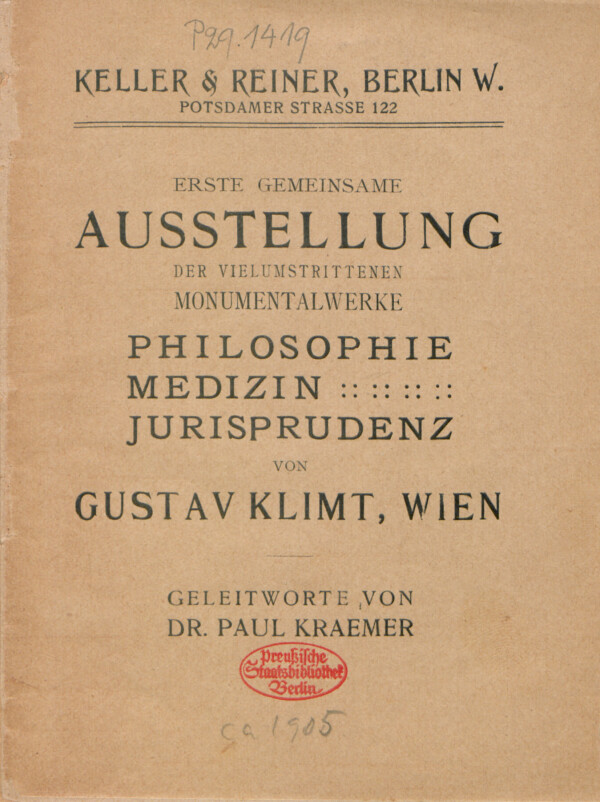

Exhibition Activity

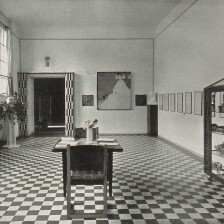

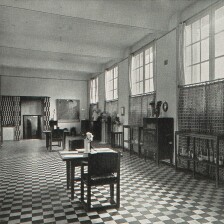

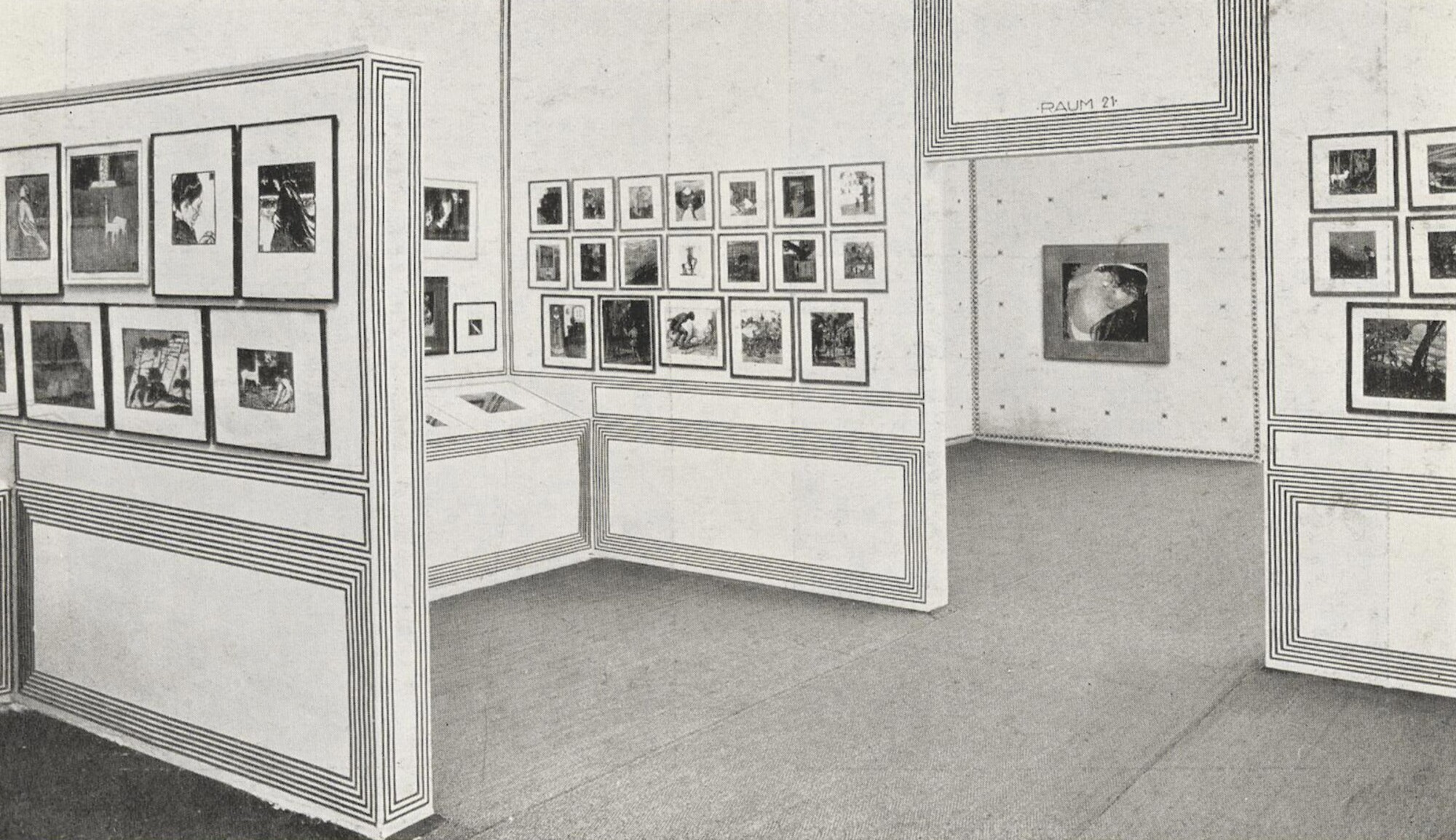

The Klimt Group having left the Vienna Secession in 1905, it had to realign and reorganize at first. Until 1908, only one major exhibition of Klimt’s work took place in Austria. He presented his latest paintings in Germany instead. His art was praised as innovative and groundbreaking in Mannheim, Berlin, and Dresden. In Vienna, Klimt, in his function as president of the exhibition committee, organized the “Kunstschau Wien” 1908 and the “Internationale Kunstschau” 1909.

To the chapter

→

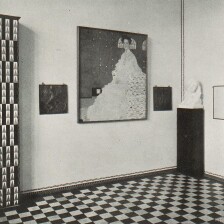

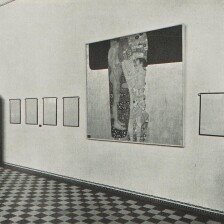

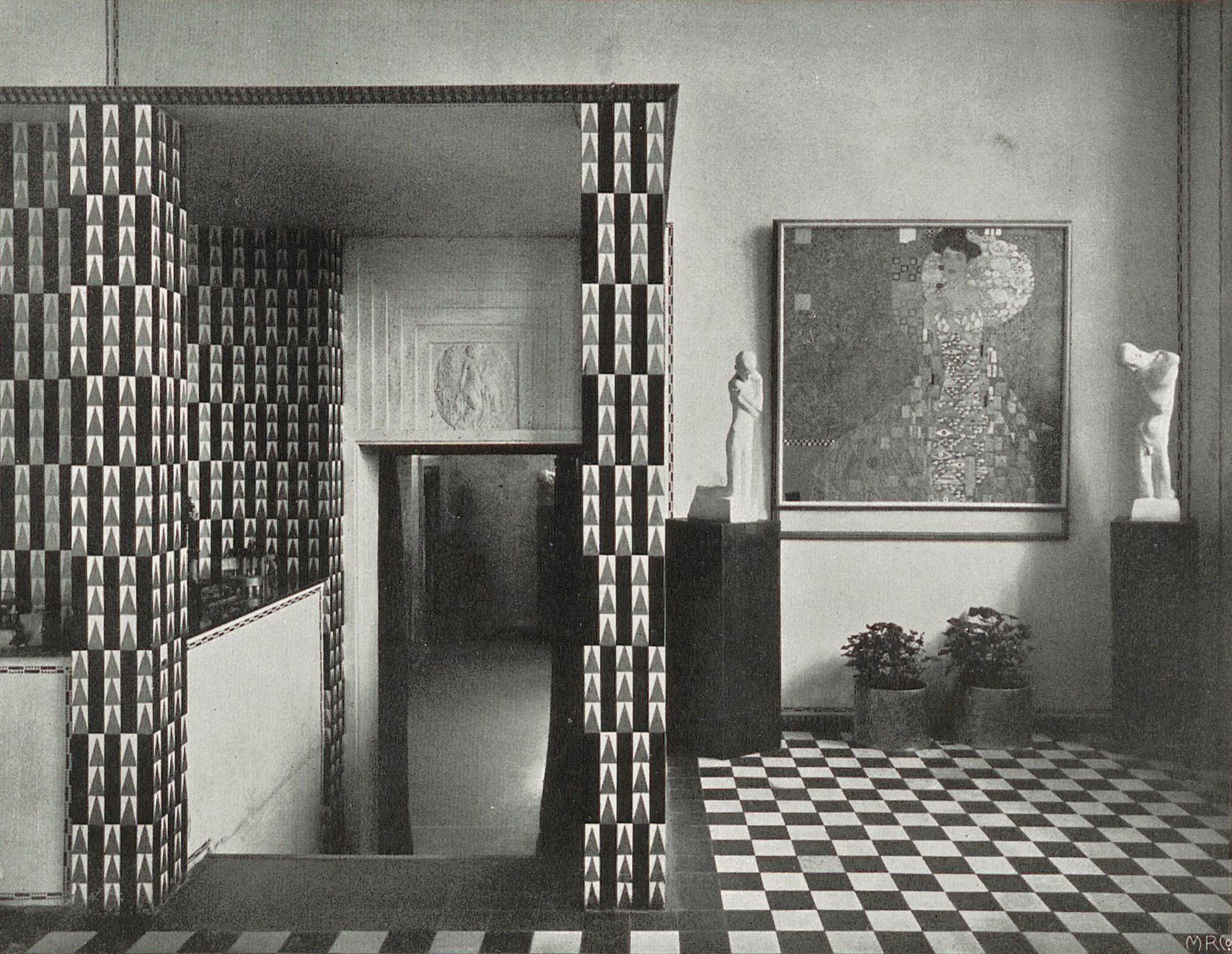

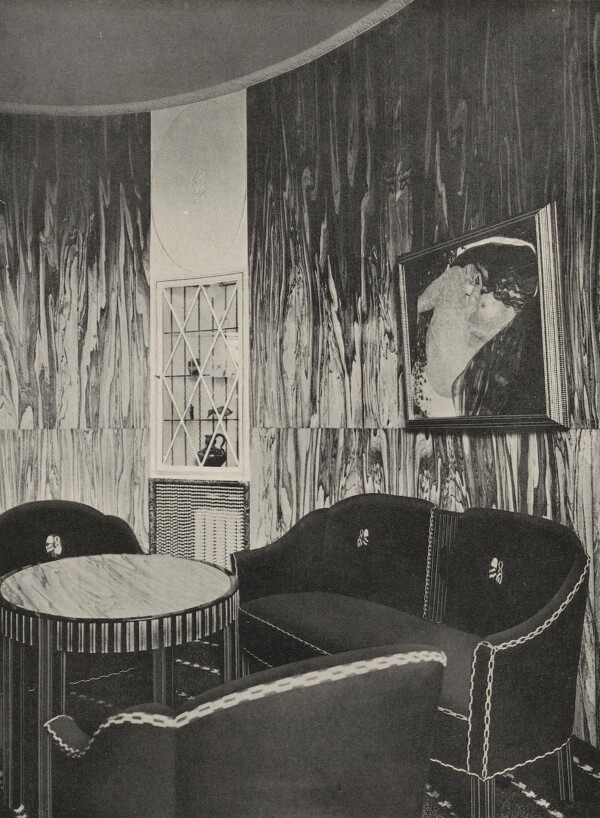

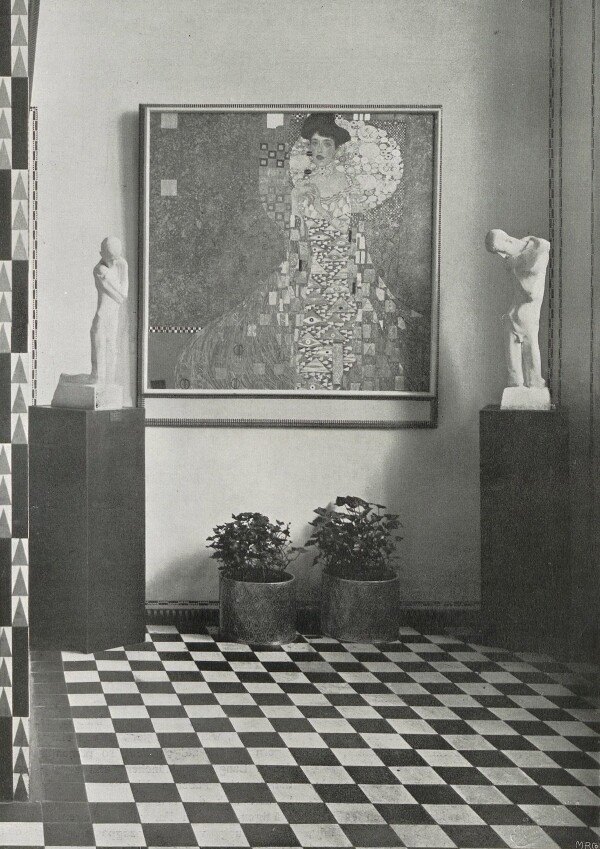

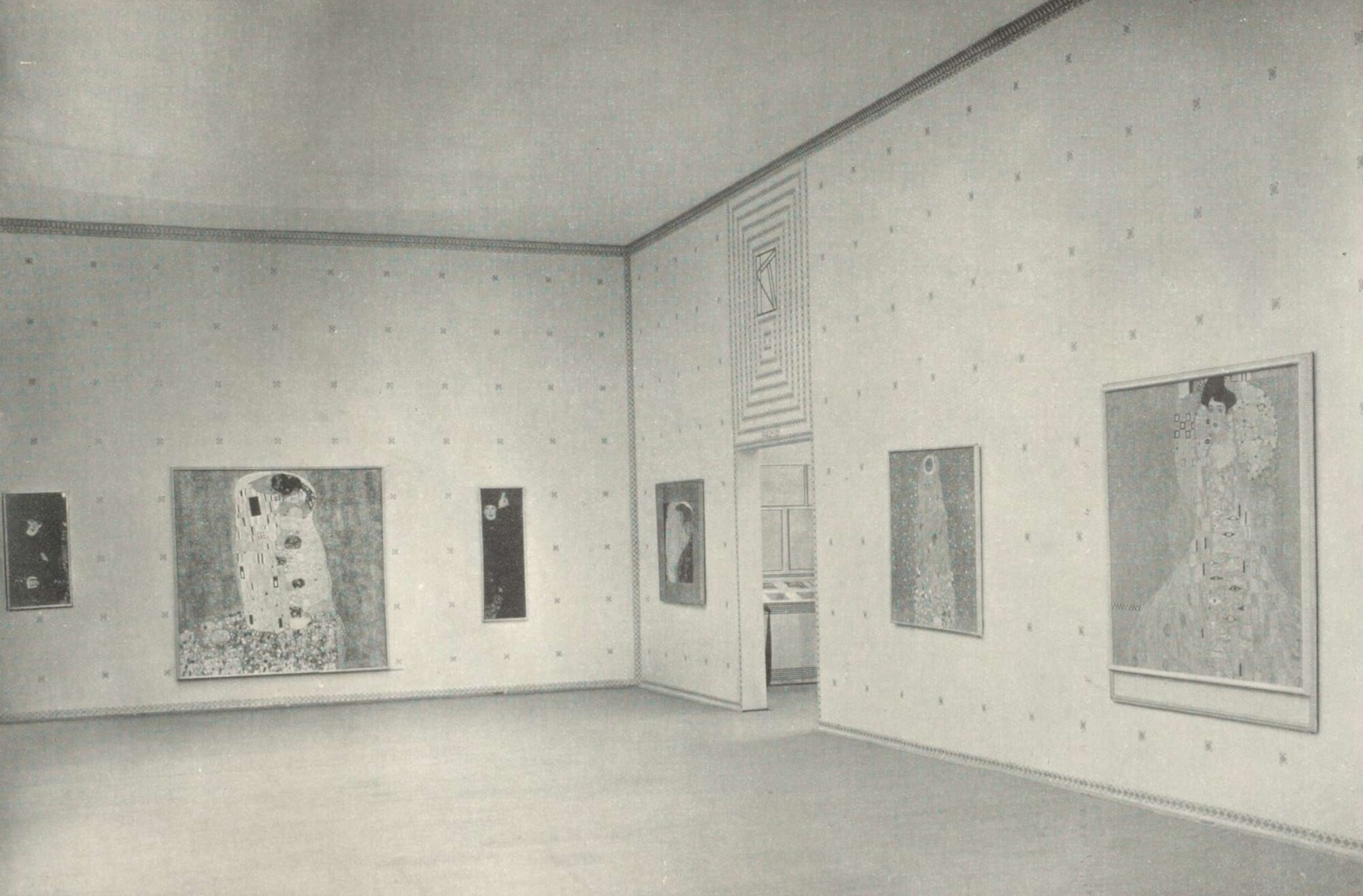

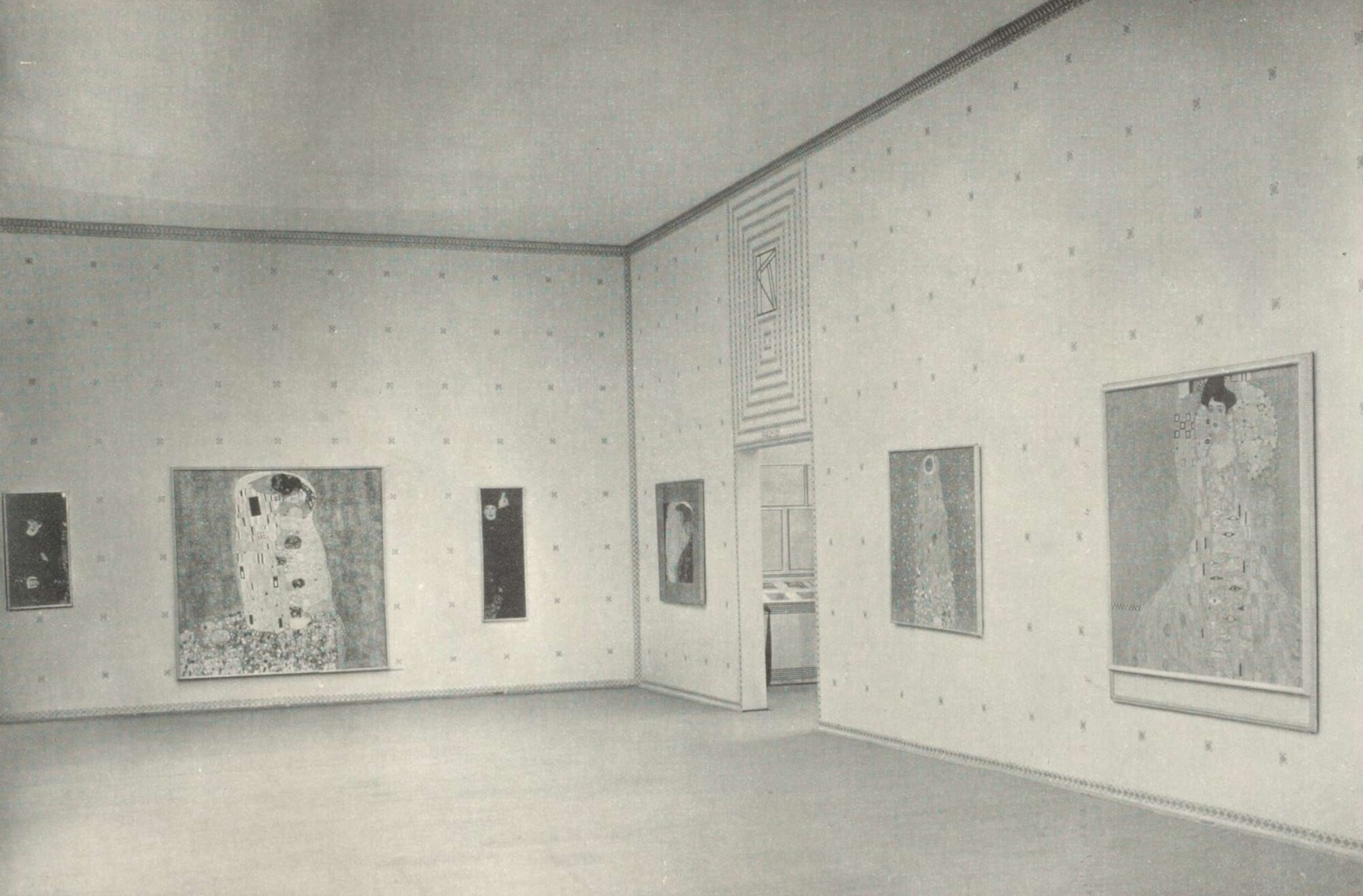

Insight into the anniversary exhibition in Mannheim, May 1907 - October 1907

© Heidelberg University Library

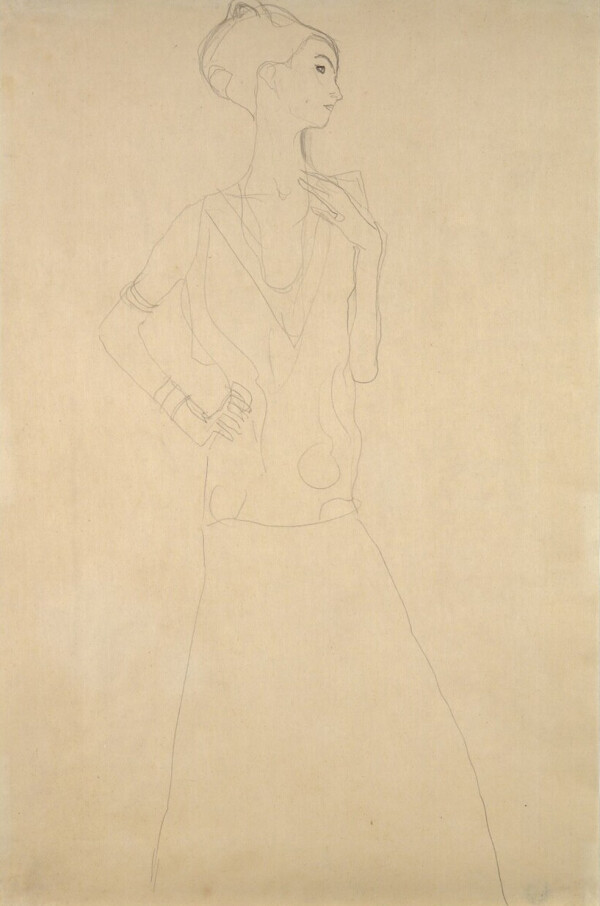

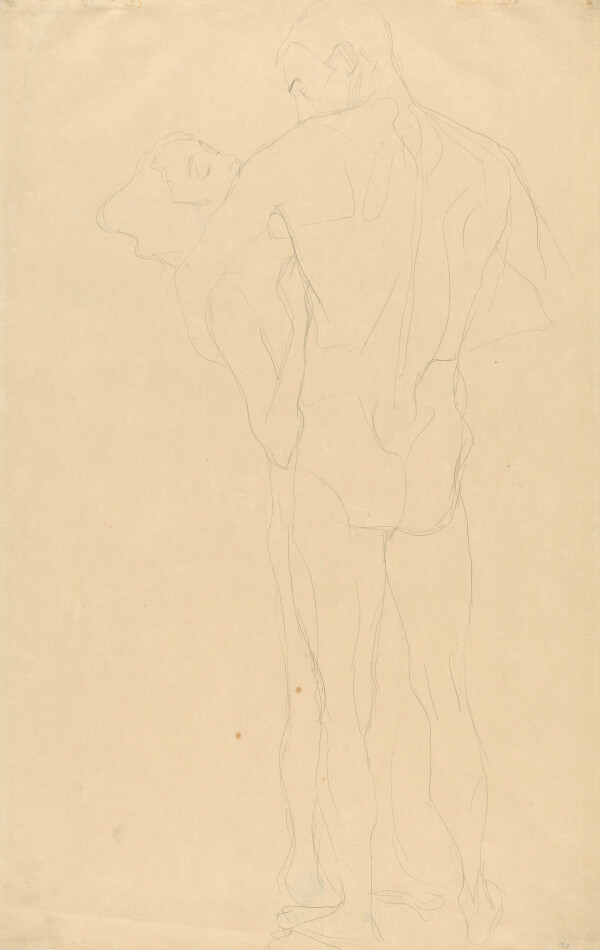

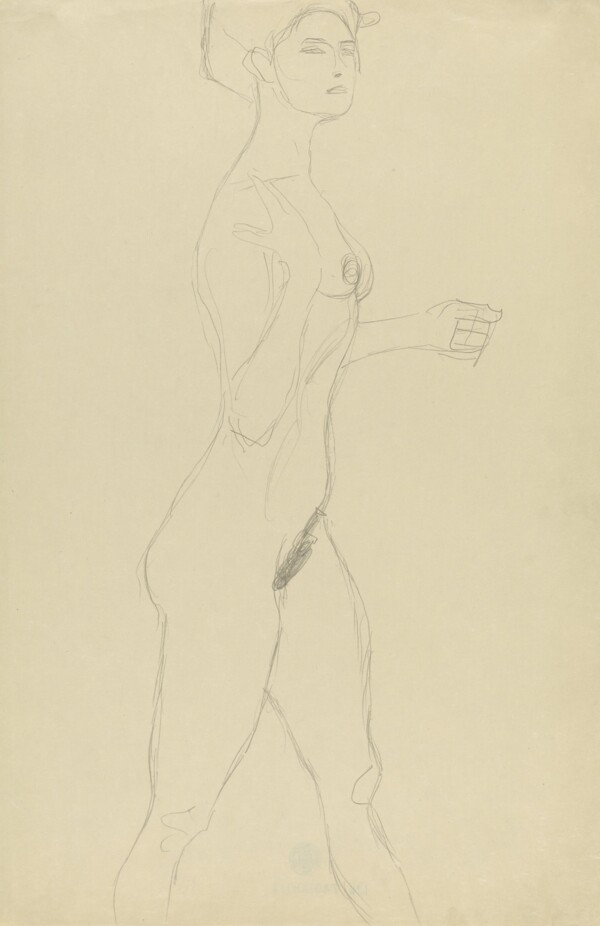

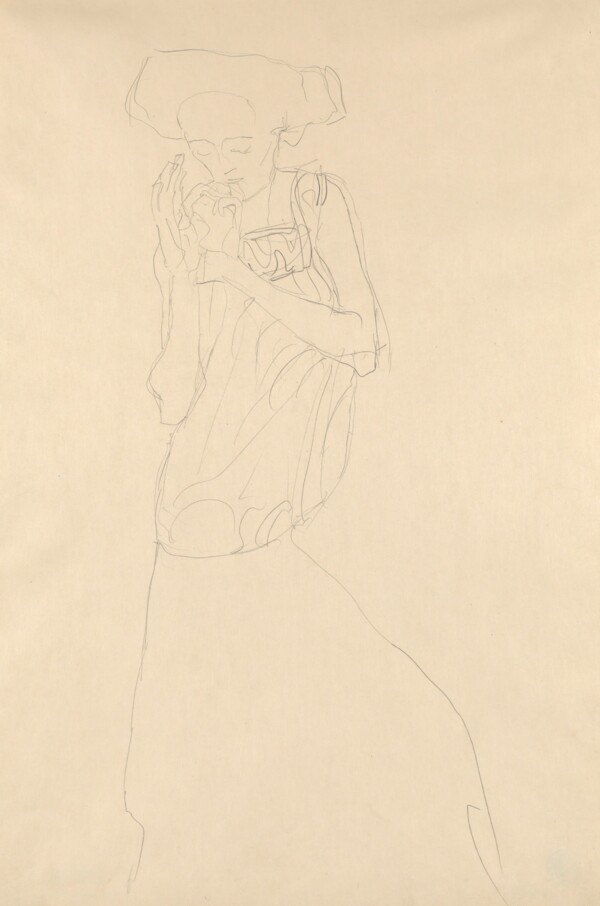

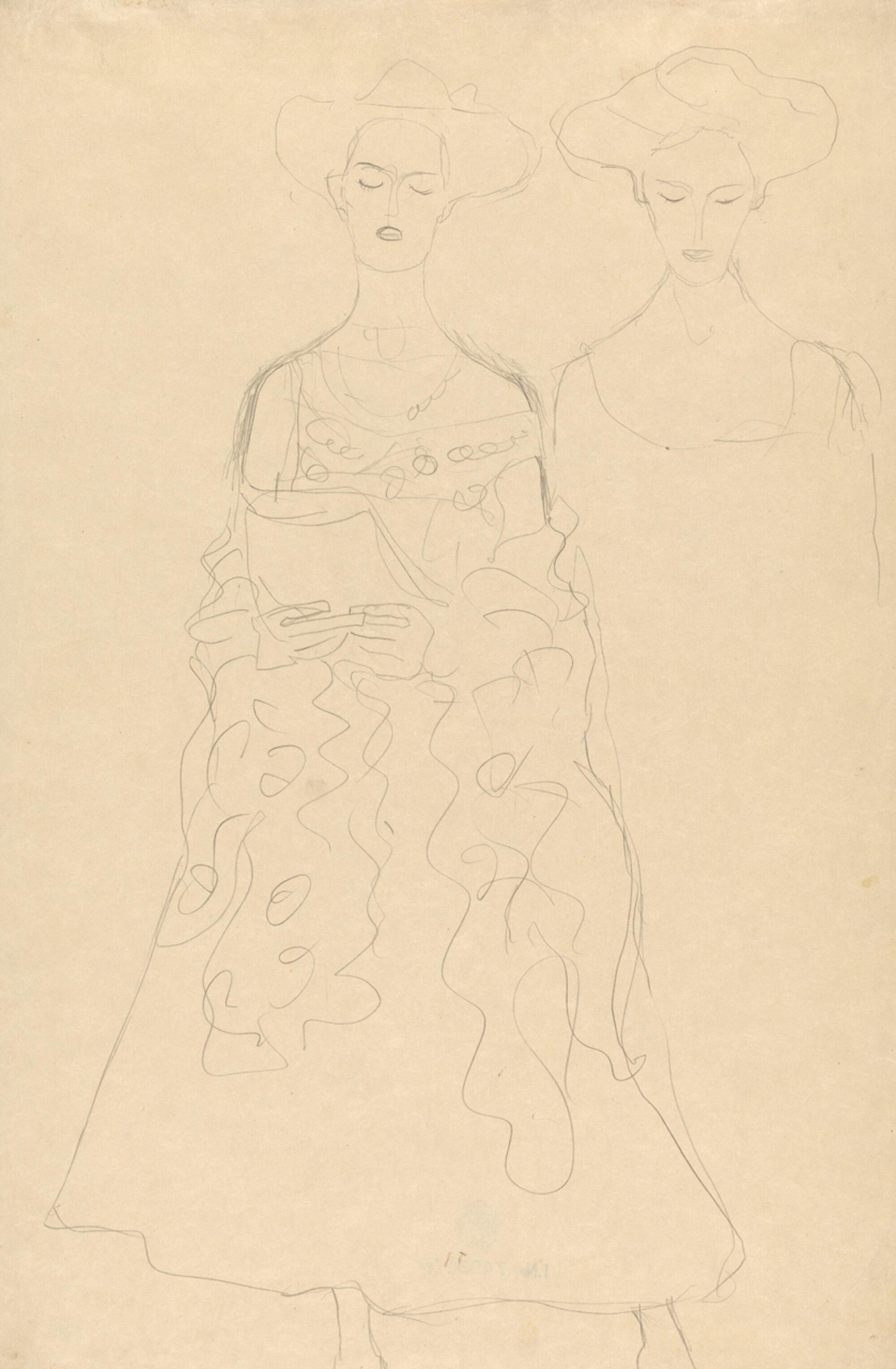

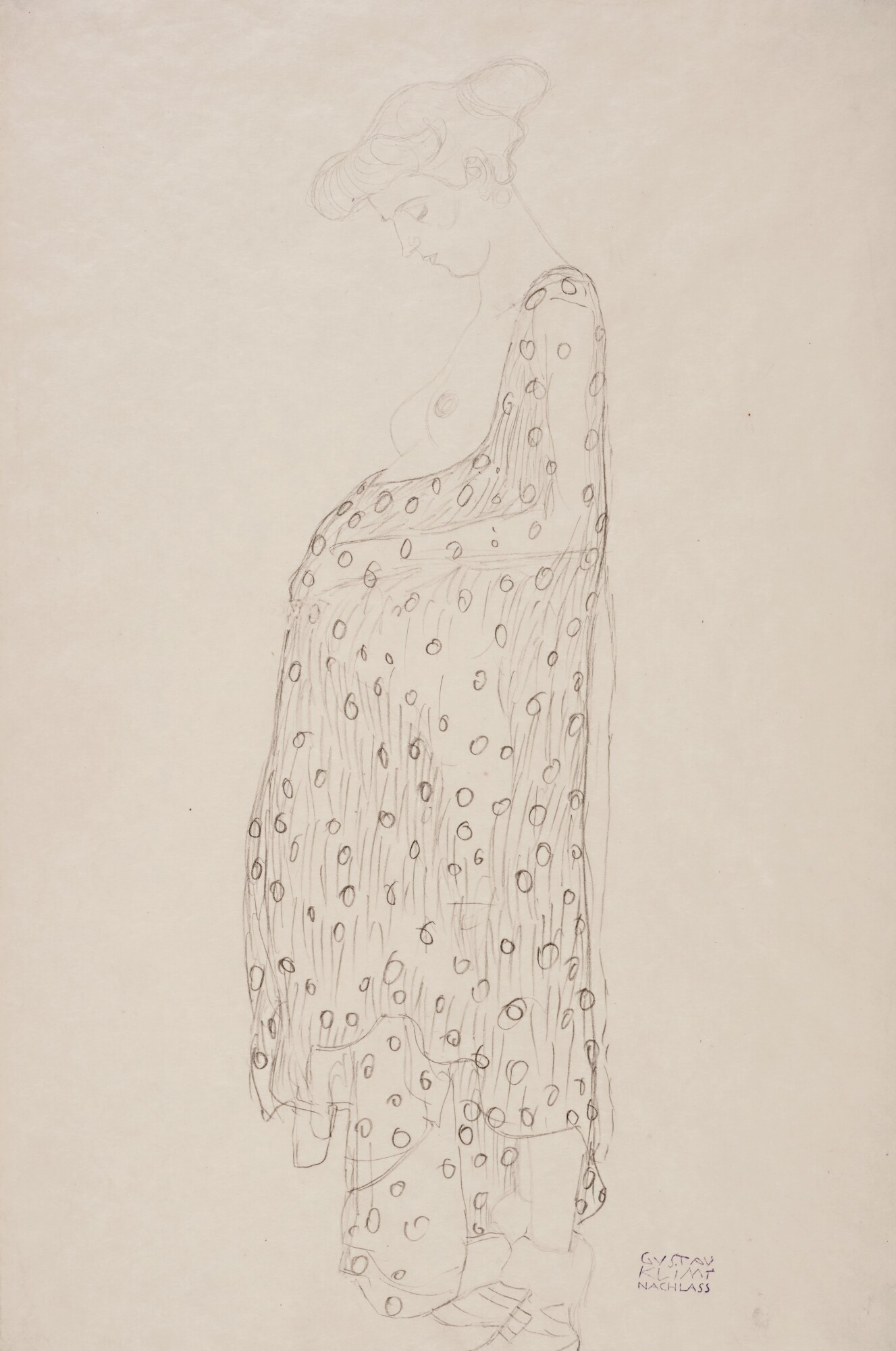

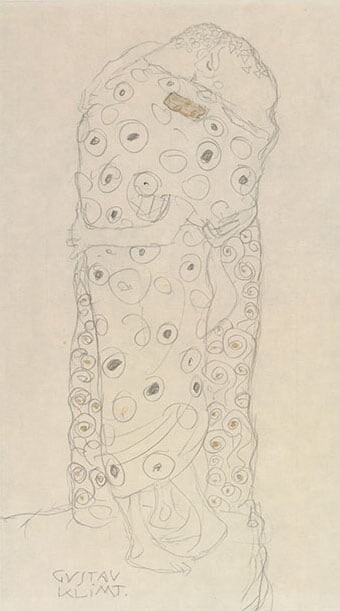

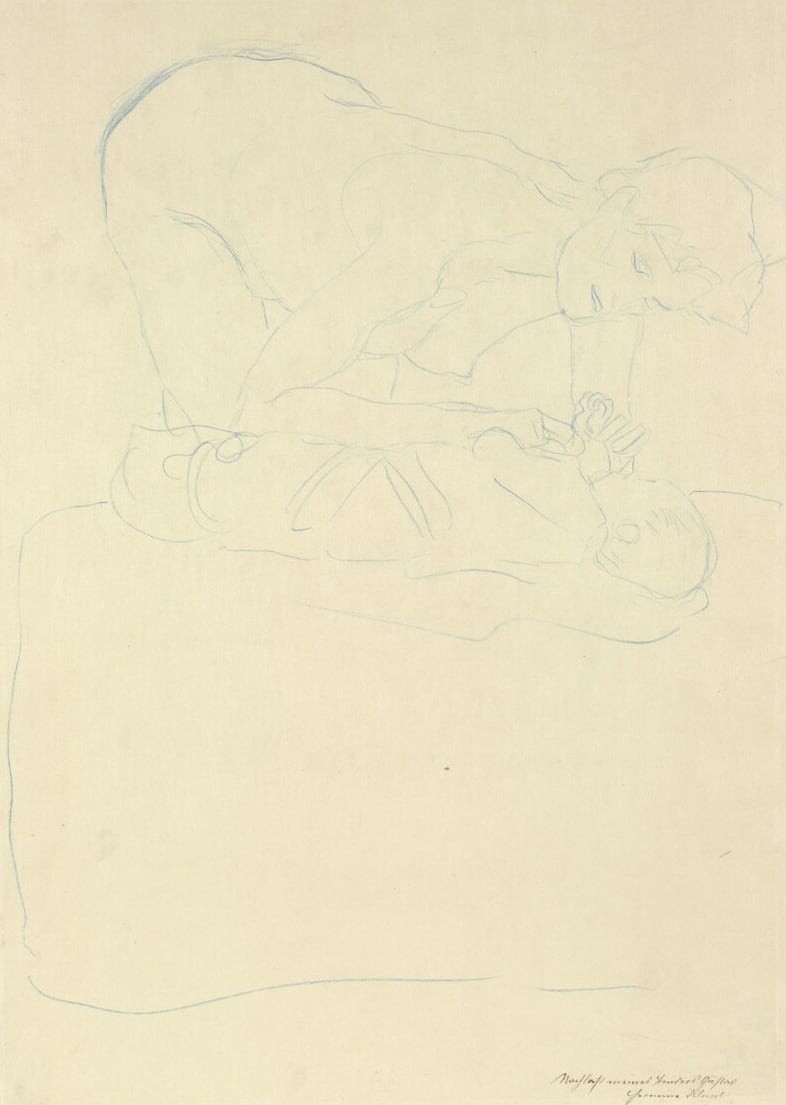

Drawings

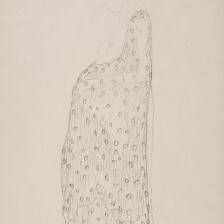

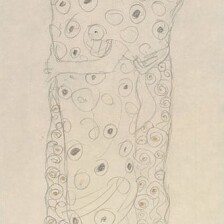

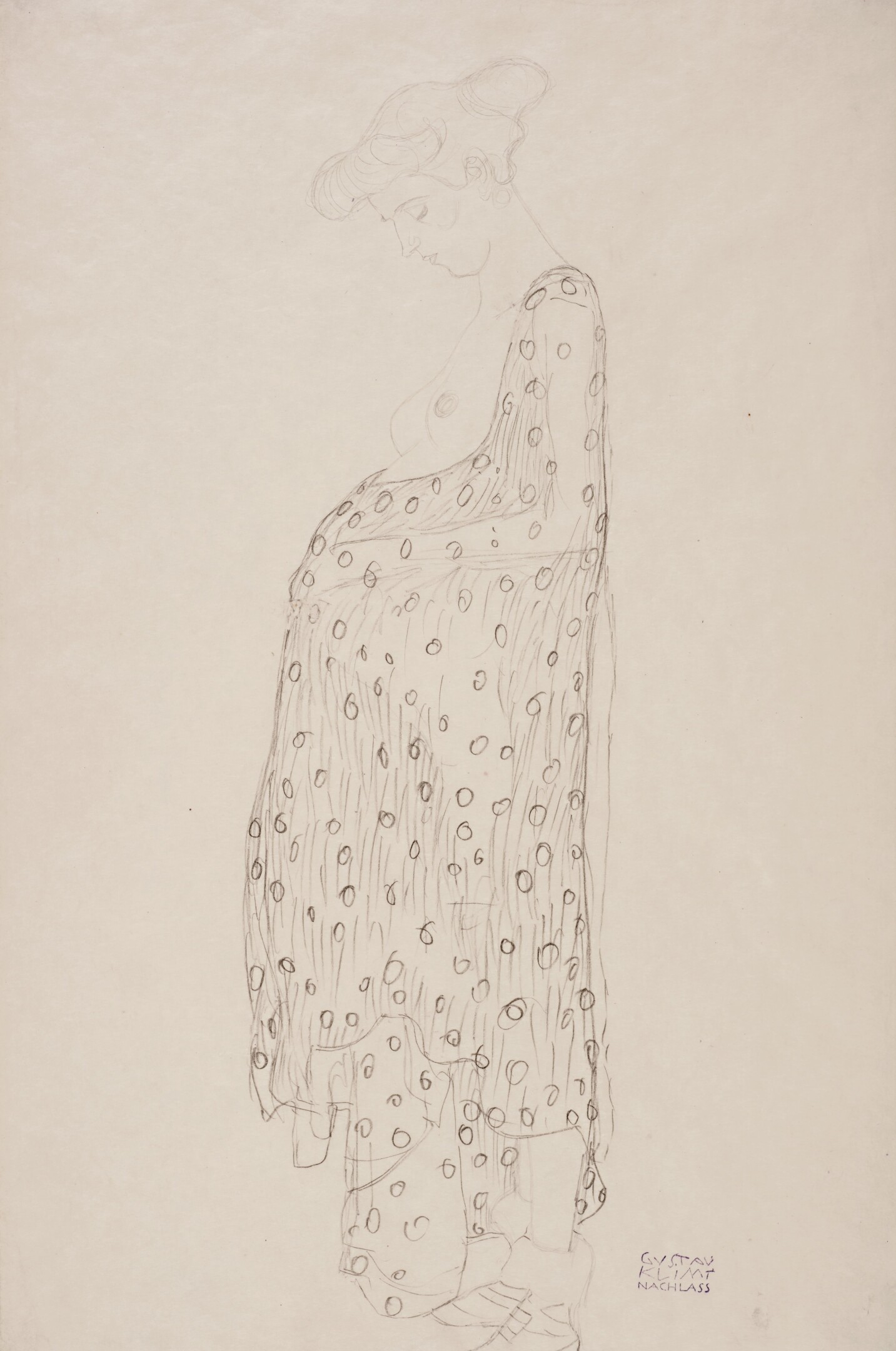

Between 1907 and 1909, Klimt mostly made sketches for the Stoclet Frieze and the paintings The Kiss (Lovers) and Hope II (Vision). The numerous studies show striding figures, dancers, pregnant women, and tightly embracing lovers. The focus is on a simplified geometrization of the postures.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Pregnant woman in profile to the left, 1907/08, Leopold Museum

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

Gustav Klimt at His Zenith

The oil paintings created between 1907 and 1909 date from the height of Klimt’s Golden Period: first of all, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I and the monumental icon The Kiss (Lovers). At this time, Klimt also worked on the frieze for the Stoclet Palace in Brussels. What is more, the Klimt group organized two of the most important and comprehensive exhibitions of Viennese Modernism, the "Kunstschau Wien 1908" and the "Internationale Kunstschau 1909".

→

Gustav Klimt: The Kiss (Lovers), 1908/09, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

Lucian’s Dialogues of the Courtesans

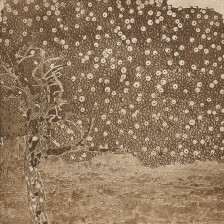

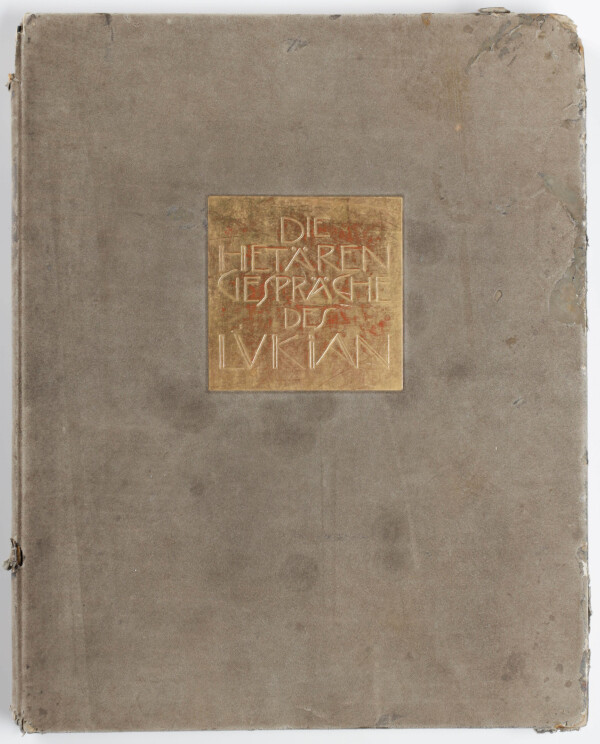

Edition C, binding, in: Franz Blei (Hg.): Die Hetärengespräche des Lukian, Leipzig 1907.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

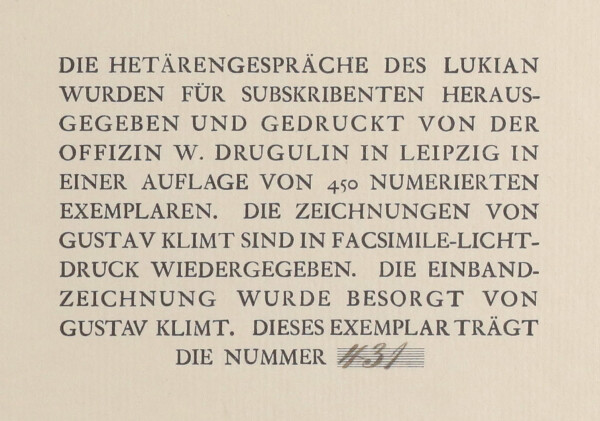

Issue C, cover page, in: Franz Blei (Hg.): Die Hetärengespräche des Lukian, Leipzig 1907.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

The luxury volume of Lucian’s Dialogues of the Courtesans was published by Julius Zeitler in 1907. Franz Blei supplied the German translation of the Dialogues by the late antique writer Lucian of Samosata; 15 erotic drawings by Gustav Klimt were integrated as collotype plates, and the Wiener Werkstätte produced the bindings of the luxurious special editions.

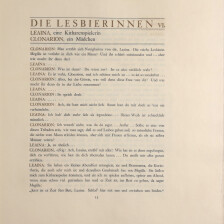

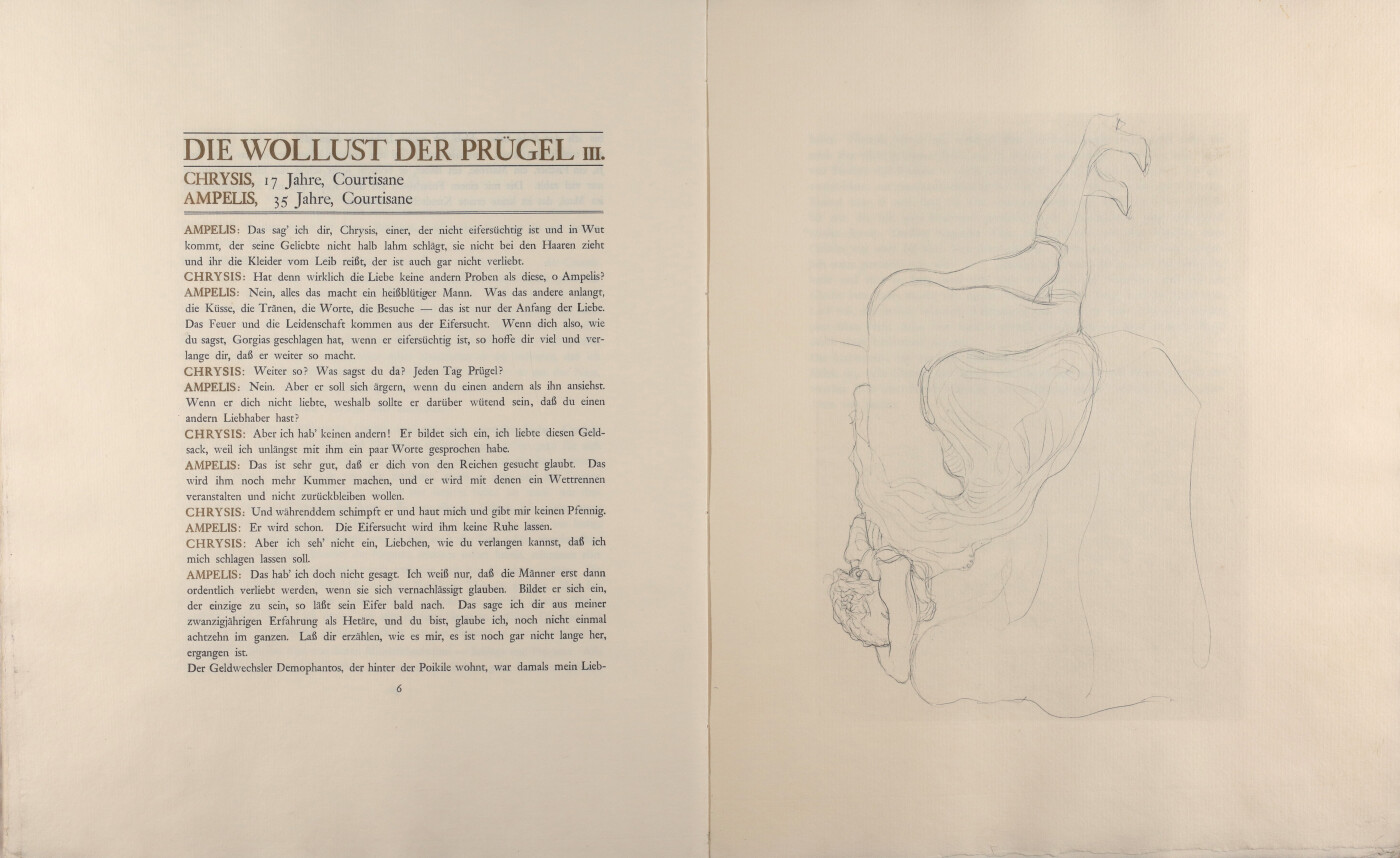

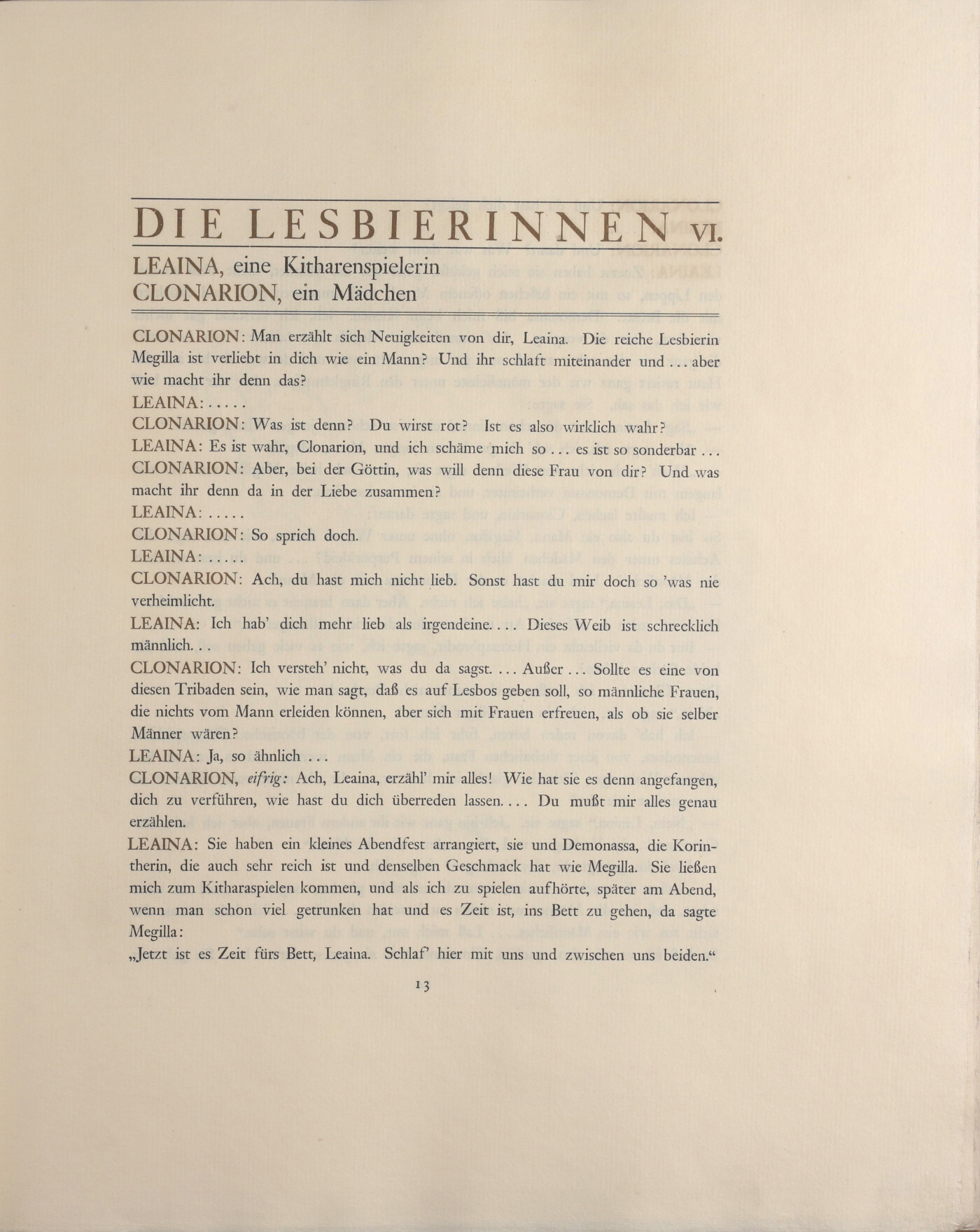

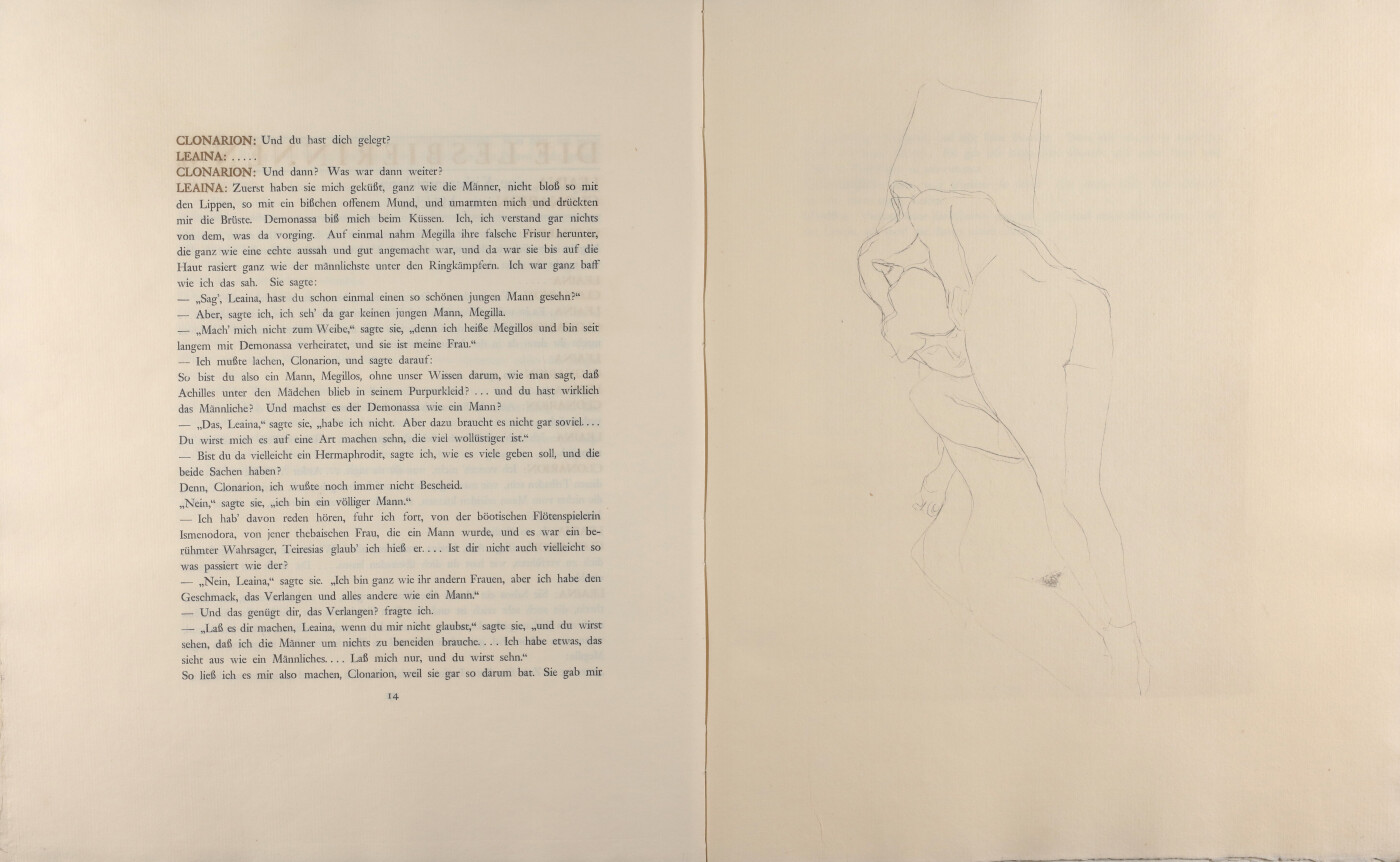

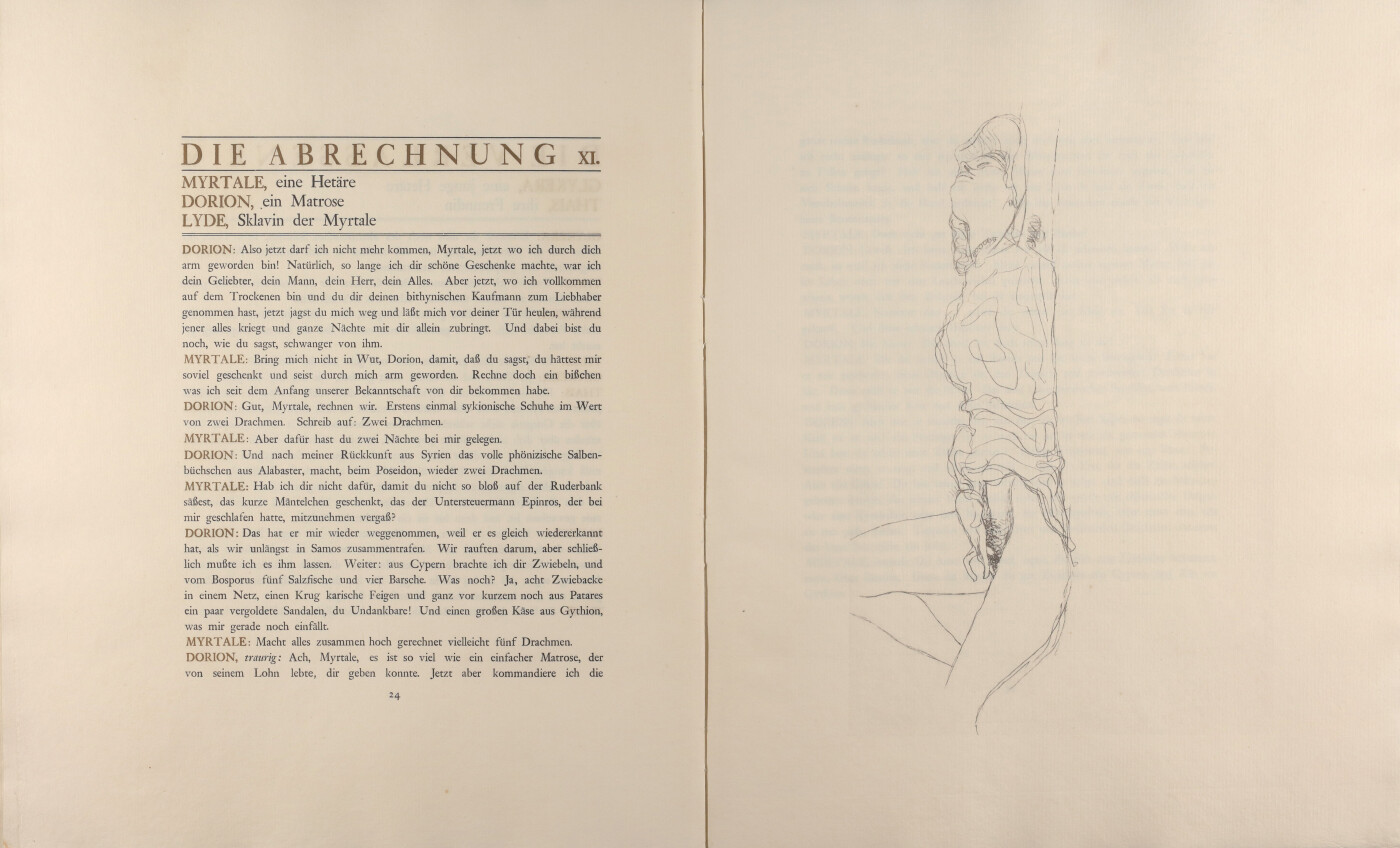

The late antique author Lucian of Samosata wrote the Dialogues of the Courtesans around 160 AD. The fifteen dialogues grant insight into the everyday life of courtesans, publicly recognized and educated prostitutes of the 5th century BC. In the stories set in the demimonde of Athens, the protagonists converse in a humorous manner on such topics as infidelity, jealousy, homosexuality, chastisement, seduction, and love spells.

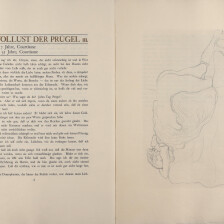

In the first German translation of Lucian’s Dialogues of the Courtesans of 1788, Christoph Martin Wieland did not include the fifth dialogue, as the conversation about lesbian love was much too immoral for his taste. It was not until 1866 that this gap was filled by the translator Theodor Fischer. The Viennese writer, essayist, and translator Franz Blei lived in Munich from 1900 on and published, among other things, the magazine Amethyst, which was considered pornographic. In 1906 he laid the literary foundation for a new edition of the Dialogues of the Courtesans. In his translation, he changed the order of the 15 dialogues and gave them provocative titles, such as “The Horrors of Marriage,” “The Voluptuousness of Spanking,” and “The Lesbians.” Blei thus also included the “immoral” dialogue about lesbian love as chapter VI.

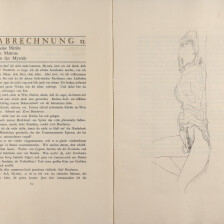

The extravagant book project was presumably initiated by Franz Blei, although in the absence of clear evidence the distribution of roles among all the players involved cannot be clearly traced. In January 1906, Gustav Klimt gave Blei a drawing, which perhaps spurred the idea for the publication of the Dialogues of the Courtesans as a luxury volume. It seems that 15 appropriate drawings by Klimt – most of which already existed – had been selected by 14 August 1906. At that time, the publisher Julius Zeitler commissioned the Wiener Werkstätte with two sample volumes “F[ÜR]. KLIMT’S LUKIAN,” the design of which was entrusted to Josef Hoffmann. The Leipzig-based editor Julius Zeitler was known among connoisseurs for publishing erotica and promoting innovative book art. Zeitler was probably also responsible for the graphic design, which stands out for its unusually wide-margined layout, the elaborate two-color typeface in black and gold, and the arrangement of the Klimt drawings. Two vertical-format drawings, The Education of Corinna and The Spell of Love, mark the beginning and end of the Dialogues of the Courtesans. In between, the remaining 13 motifs have been inserted in landscape format, forcing readers to interrupt their reading and turn the book by 90 degrees to look at them.

-

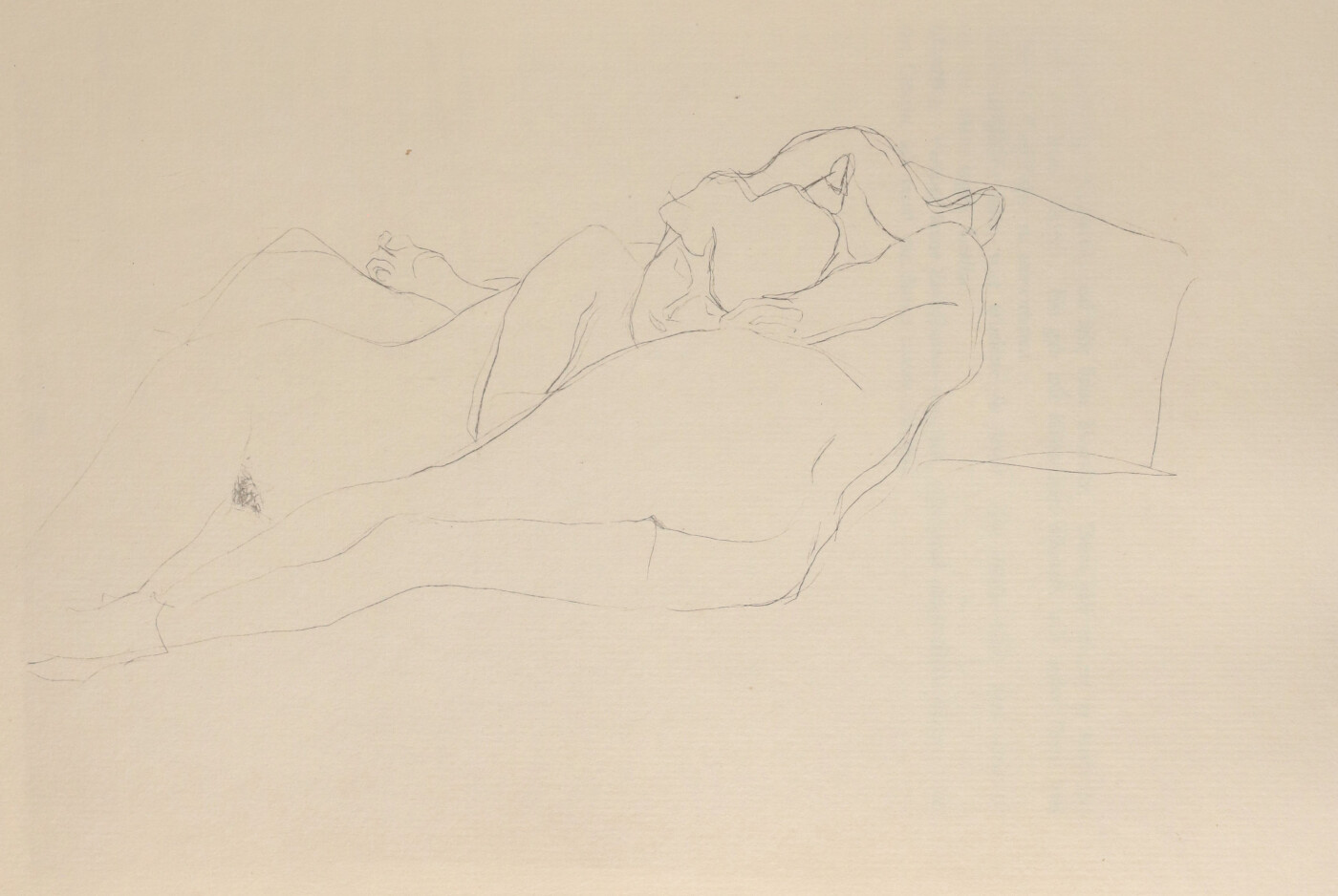

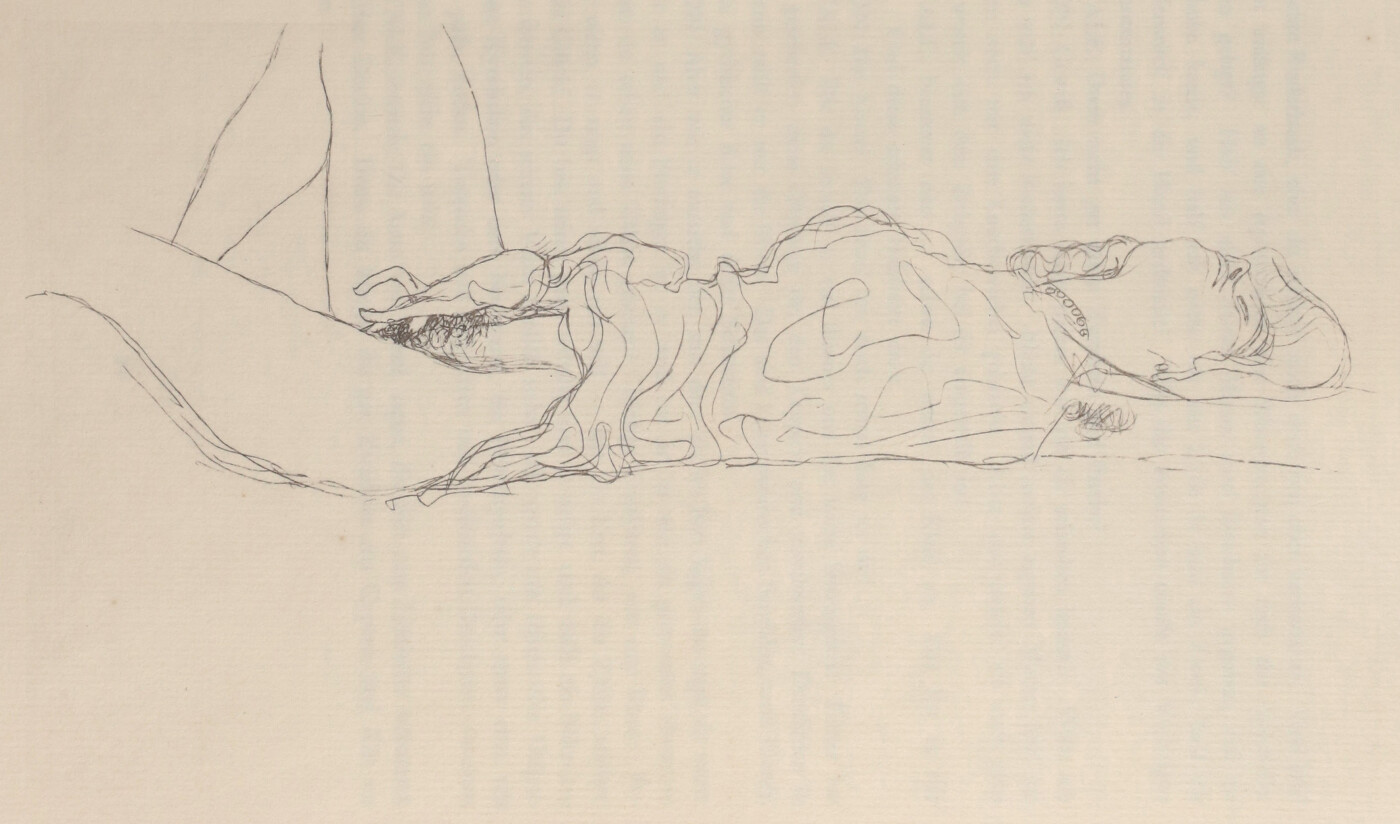

Edition C, The lust of the beating III., in: Franz Blei (Hg.): Die Hetärengespräche des Lukian, Leipzig 1907.

Edition C, The lust of the beating III., in: Franz Blei (Hg.): Die Hetärengespräche des Lukian, Leipzig 1907.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Edition C, The lust of the beating III., in: Franz Blei (Hg.): Die Hetärengespräche des Lukian, Leipzig 1907.

Edition C, The lust of the beating III., in: Franz Blei (Hg.): Die Hetärengespräche des Lukian, Leipzig 1907.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

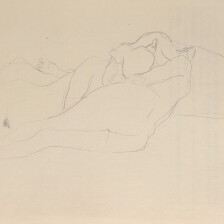

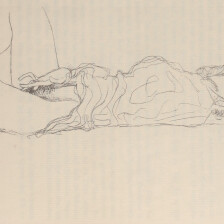

Issue C, The Lesbians VI., in: Franz Blei (Hg.): Die Hetärengespräche des Lukian, Leipzig 1907.

Issue C, The Lesbians VI., in: Franz Blei (Hg.): Die Hetärengespräche des Lukian, Leipzig 1907.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Issue C, The Lesbians VI., in: Franz Blei (Hg.): Die Hetärengespräche des Lukian, Leipzig 1907.

Issue C, The Lesbians VI., in: Franz Blei (Hg.): Die Hetärengespräche des Lukian, Leipzig 1907.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Issue C, The Lesbians VI., in: Franz Blei (Hg.): Die Hetärengespräche des Lukian, Leipzig 1907.

Issue C, The Lesbians VI., in: Franz Blei (Hg.): Die Hetärengespräche des Lukian, Leipzig 1907.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

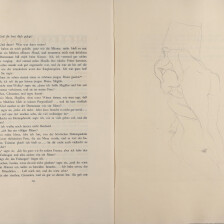

Edition C, The Reckoning XI., in: Franz Blei (Hg.): Die Hetärengespräche des Lukian, Leipzig 1907.

Edition C, The Reckoning XI., in: Franz Blei (Hg.): Die Hetärengespräche des Lukian, Leipzig 1907.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Edition C, The Reckoning XI., in: Franz Blei (Hg.): Die Hetärengespräche des Lukian, Leipzig 1907.

Edition C, The Reckoning XI., in: Franz Blei (Hg.): Die Hetärengespräche des Lukian, Leipzig 1907.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

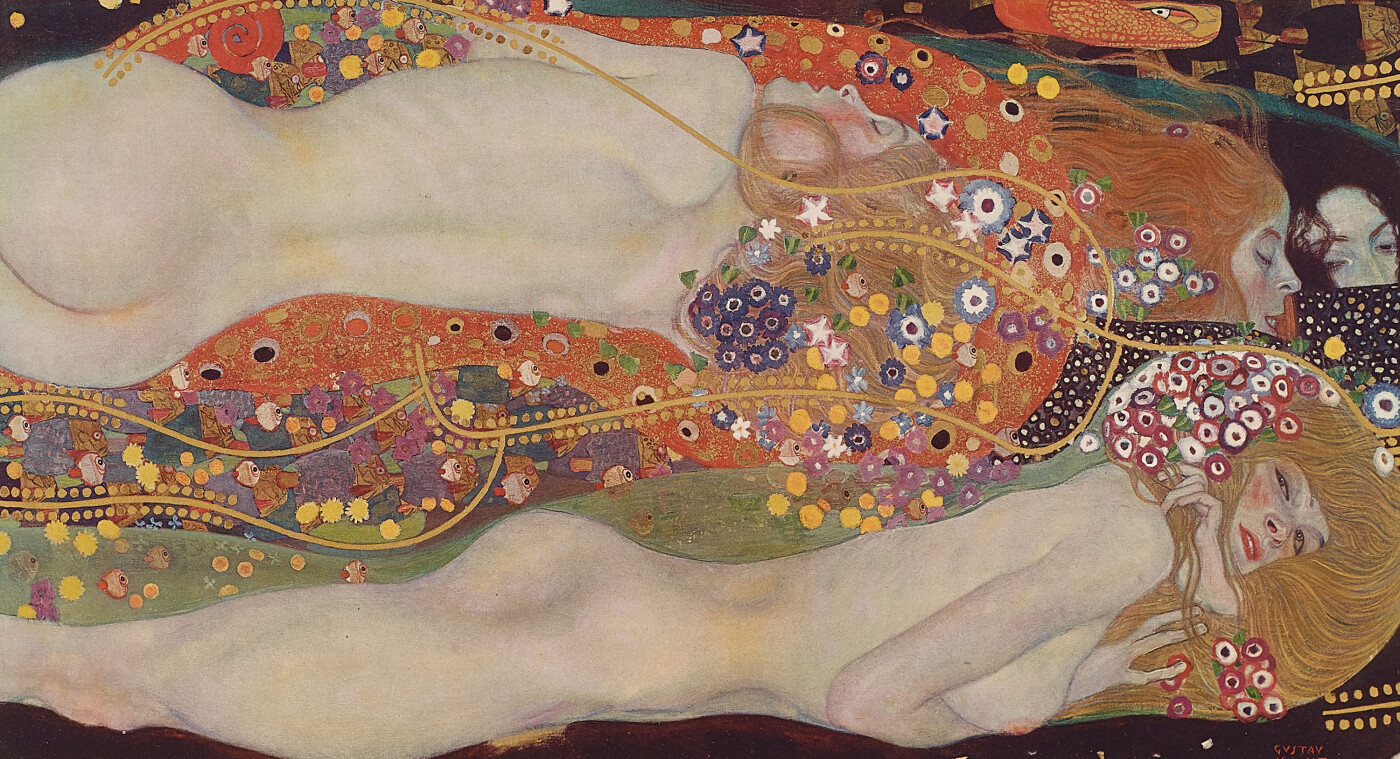

Gustav Klimt’s Erotic Drawings in the Dialogues of the Courtesans

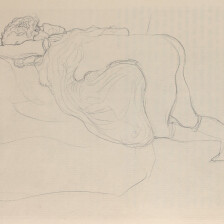

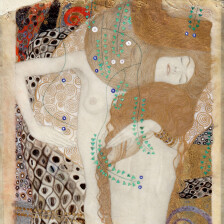

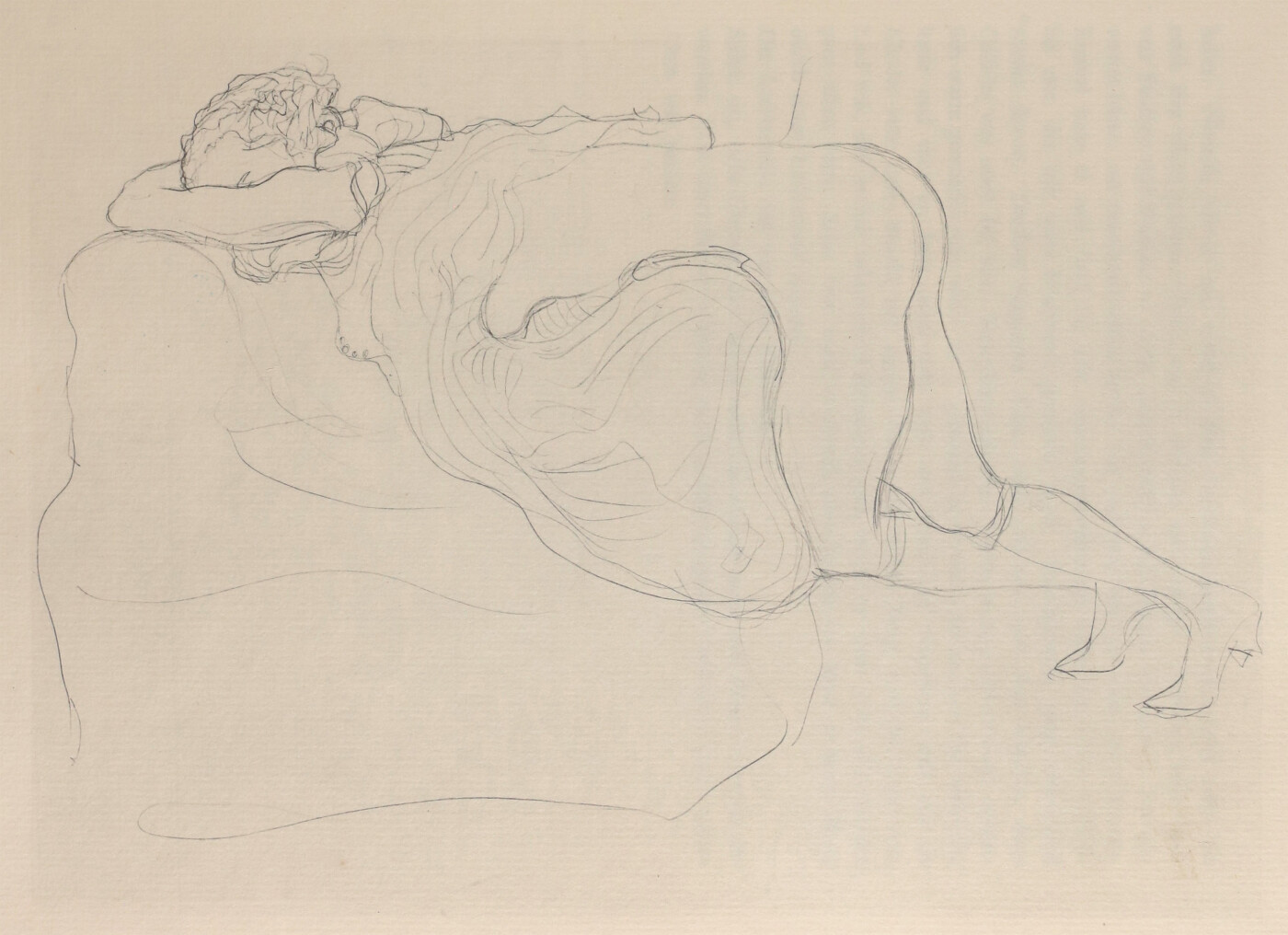

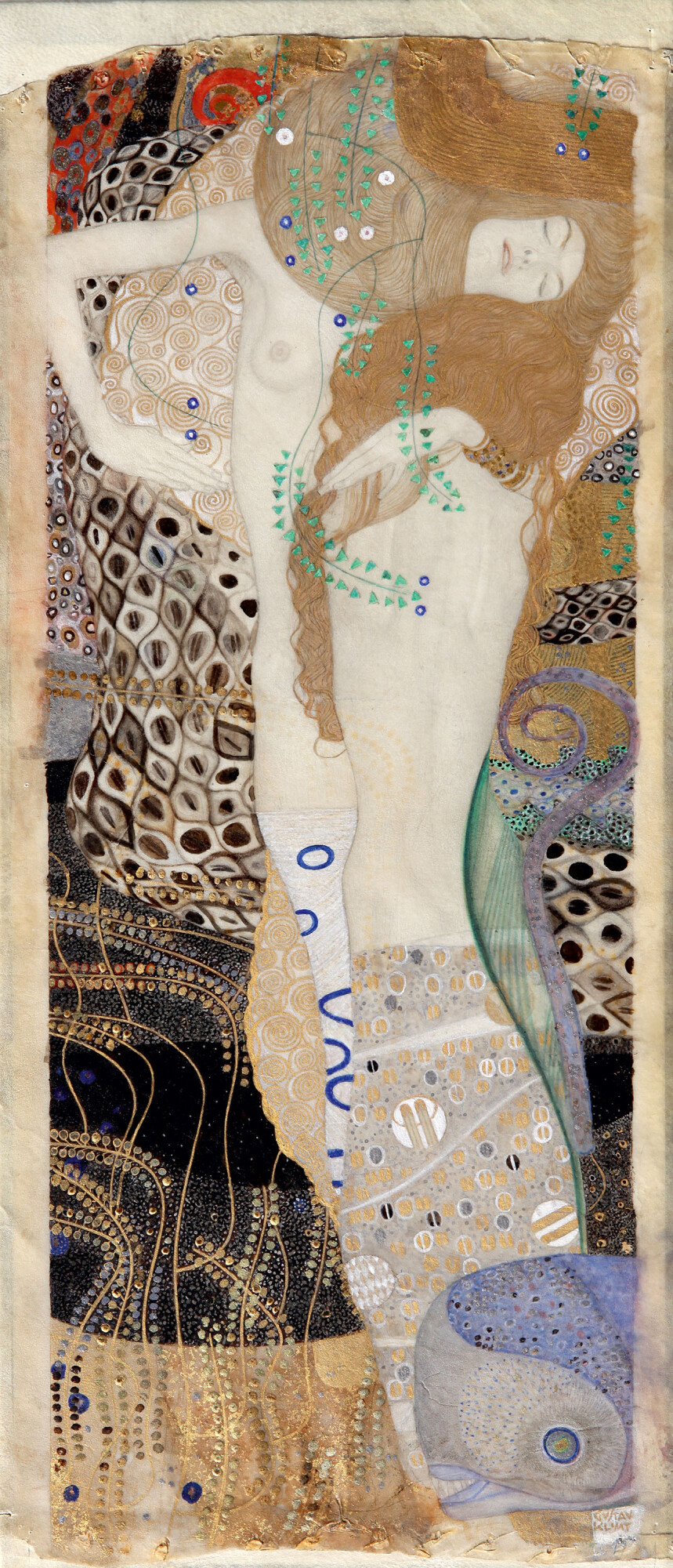

On grounds of both style and material, Klimt’s 15 erotic drawings visually complementing the Dialogues of the Courtesans can be dated to the period between 1904 and 1906. Some of the drawings are related to the studies for Water Snakes II (1904, reworked before 1908, private collection). About two-thirds of the works were made in 1904 around Klimt’s turning point in drawing, when he switched from soft chalk on kraft paper to hard pencil on lighter-colored Japan paper in larger formats. In addition, he took to depicting erotic female bodies at the time. Different from his painted works, in his drawings he introduced motifs of masturbating or lesbian nude and semi-nude women.

For his sensual depictions that went beyond common moral concepts, Klimt probably found sources of inspiration in Greek vase painting, Japanese woodcuts, and the erotic illustrations of the English artist Aubrey Beardsley, with which Klimt was well familiar. The drawings chosen for the Dialogues of the Courtesans mostly show reclining figures, for which Klimt had arrived at refined linear compositions, accentuating such details as pubic and armpit hair or pieces of jewelry and drapery wrapped around the bodies.

Aside from the Dialogues of the Courtesans, the drawings stand as independent works illustrating the texts and providing an intimate insight into Klimt’s work. Thus Franz Blei remarked in his autobiography from 1940:

“[T]he woman’s image was his [Klimt’s] predilection, and those thousands of drawn nude or half-nude female bodies capturing these moments were his private life, so to speak, the diary of his best achievements in every sense.”

Issue C, copy number 431 of 450, in: Franz Blei (Hg.): Die Hetärengespräche des Lukian, Leipzig 1907.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Issue B, copy number 11 of 100, binding, in: Franz Blei (Hg.): Die Hetärengespräche des Lukian, Leipzig 1907.

© Dorotheum, Vienna

Issue C, issue B, copy number 11 of 100, back cover (detail), in: Franz Blei (Hg.): Die Hetärengespräche des Lukian, Leipzig 1907.

© Dorotheum, Vienna

Production and Special Editions of the Luxury Volume

The bibliophilic reedition of Lucian‘s Dialogues of the Courtesans should originally have appeared before Christmas 1906, so as to attract the attention of a clientele with money to spend for the holiday season. However, the luxury edition was not completed before January 1907. The traditional book printer Offizin W. Drugulin in Leipzig was entrusted with its production. The drawings were reproduced by Obernetter in Munich, one of the pioneers of and specialists in collotype printing. The costly product with its lavish design was to meet the highest standards. The difficulty lay in bringing together and matching the dimensions of the printed text and the collotype prints bound in as plates.

The same quality standards applied to the bindings of the 450 numbered copies. Josef Hoffmann designed the sample bindings for the two special editions A and B, which were produced by the Wiener Werkstätte. Edition A, the most luxurious edition, was limited to 50 copies and printed on Japan paper. The edition features a black-and-white marbled full-cloth binding with a gold embossed cover plate designed by Klimt, gilt edges, and black-and-white marbled endpapers matching the binding. Edition B, printed on handmade paper, comprised 100 copies featuring gray chamois leather binding with a gold embossed cover plate and gilt edges, but without the handmade endpapers. The bindings of the two special editions bear Hoffmann’s monogram JH and the three-line company logo WIENER=WERK=STÄTTE embossed in gold on the back. Edition C, limited to 300 copies, is the most basic of the three versions, with a full-cloth binding and gold embossed cover title. Franz Blei commented upon the different editions in a letter to the publisher Julius Zeitler:

“[A]s to the Lucian volumes, you are completely right: all of the three book covers will come out superb, and everyone can choose according to their taste and pocket.”

A few surviving special editions A and B point to the group of buyers who could afford the high-priced luxury versions. Among the first owners were Berta Zuckerkandl, Kolo Moser, Paul Bacher, Gottfried Eissler, and the important German collector Karl Ernst Osthaus. Hermann Bahr owned a copy of Edition C and thanked Blei for the work, launching into a eulogy about his friend Gustav Klimt and his taboo breaking in the medium of drawing:

“I drink to Klimt, the bright pagan. Those know-it-alls out there believe he merely plays with lines. Poor fools, they don’t recognize the indescribable power of this lewdness swearing to be sacred! He is the only one for whom burgeoning nature is not obscured by bourgeois shame; the only one looking at things from a pagan’s perspective. The only one for whom the woman is woman all over.”

Literature and sources

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band II, 1904–1912, Salzburg 1982, S. 86.

- Tobias G. Natter: Gustav Klimt und die Hetärengespräche des Lukian. Ein Erotikon, sein Bedeutungsraum und die griechische Antike, in: Stella Rollig, Tobis G. Natter (Hg.): Klimt und die Antike. Erotische Begegnungen, Ausst.-Kat., Orangery (Vienna), 23.06.2017–08.10.2017, Munich 2017, S. 8-25.

- Marian Bisanz-Prakken: Klimts Zeichnungen für die Hetärengespräche und ihr Stellenwert im Werk des Künstlers, in: Stella Rollig, Tobis G. Natter (Hg.): Klimt und die Antike. Erotische Begegnungen, Ausst.-Kat., Orangery (Vienna), 23.06.2017–08.10.2017, Munich 2017, S. 26-33.

- Stephanie Auer: Die prominenten Erstbesitzerinnen und Erstbesitzer der Hetärengespräche, in: Stella Rollig, Tobis G. Natter (Hg.): Klimt und die Antike. Erotische Begegnungen, Ausst.-Kat., Orangery (Vienna), 23.06.2017–08.10.2017, Munich 2017, S. 78-85.

- Hermann Bahr: Die Opale. Blätter für Kunst und Literatur, Leipzig 1907, S. 127-128.

- Stefan Kutzenberger: "Die Wollust der Prügel". Gustav Klimt, Franz Blei und die "Hetärengespräche" des Lukian, in: Tobias G. Natter, Franz Smola, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Klimt persönlich. Bilder – Briefe – Einblicke, Ausst.-Kat., Leopold Museum (Vienna), 24.02.2012–27.08.2012, Vienna 2012, S. 144-163.

- Hartmut Walravens: Briefe Franz Bleis an den Verleger Julius Zeitler (1874-1943). Die Rolle Franz Bleis als Verlagsberater, in: Monika Estermann, Ursula Rautenberg (Hg.): Archiv für Geschichte des Buchwesens, Band 64, Berlin - Boston 2009, S. 1-52, Nr. 12.

- Franz Blei: Zeitgenössische Bildnisse, Amsterdam 1940, S. 95.

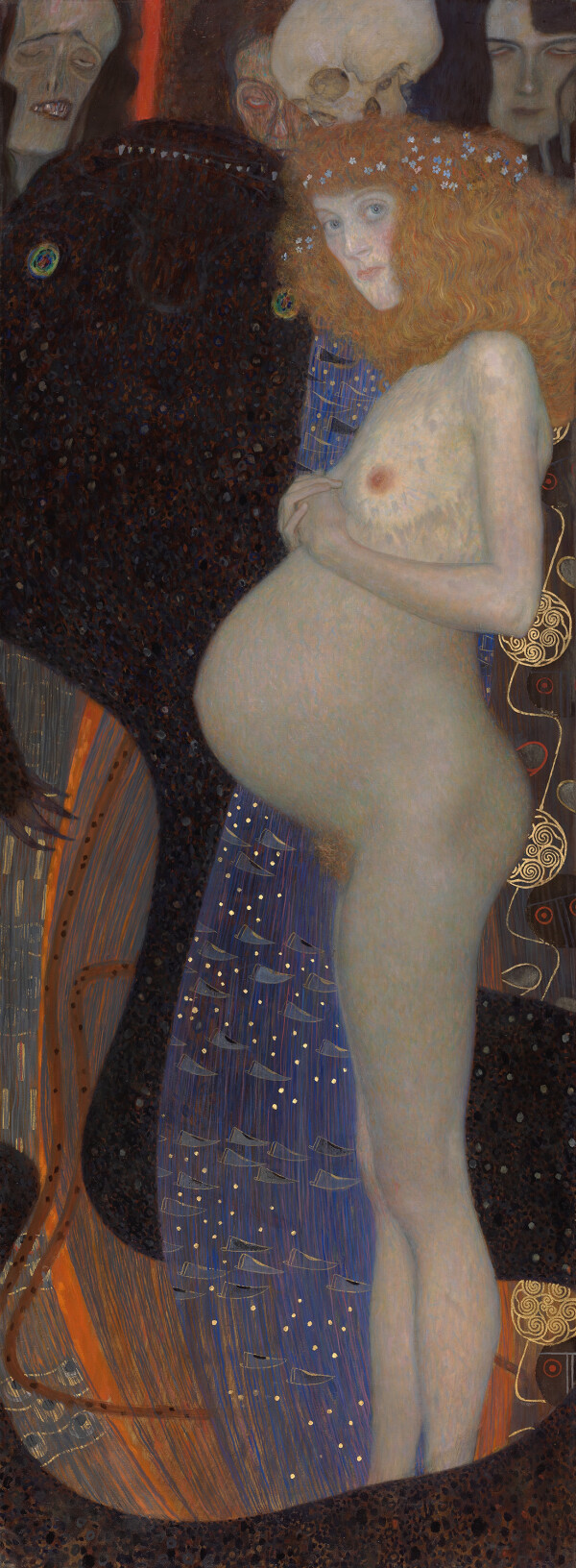

Highlights of the Golden Period

Gustav Klimt: Hope II (Vision), 1907/08, The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder and Helen Acheson Funds, and Serge Sabarsky

© Scala Florence

Some of Gustav Klimt’s most prestigious masterpieces were created in the years between 1907 and 1909. In his paintings The Kiss (Lovers) and Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II, he carried the effect of gold to its height. In his works Hope II, Danaë, and Judith II, he dealt with the image of women around 1900.

Hope II (Vision)

In 1909, the painting Hope II (Vision) (1907/08, reworked before 1914, The Museum of Modern Art, New York) was first presented under the title of Vision at the “Internationale Kunstschau Wien,” where it was juxtaposed with the first version of the subject, Hope I (1903/04, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa).

As he had been in the first version, in this work Klimt was also concerned with the existential questions of becoming and passing away, of life and death. As early as 1909, Berta Zuckerkandl noted that the woman well advanced in pregnancy in Klimt’s work stands for “eternally sprouting life that victoriously overcomes illness and death.” Yet as opposed to the first version of the theme, Klimt did without the threatening figures above and behind the pregnant woman, limiting the menacing aspect of the scene to a skull, which, however, lies directly on the pregnant woman’s belly. She has bowed her head as if to pray for her child. Three other women form what resembles a pedestal, on which the protagonist seems to be standing. With their arms raised, they, too, appear to be praying. Colorful ornaments, spirals, and a shimmering golden background reminiscent of medieval icons identify the square picture as a typical composition of the Golden Period.

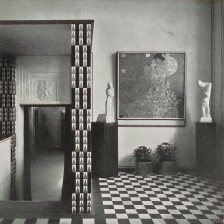

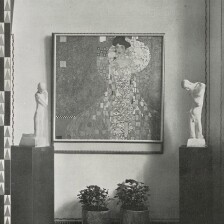

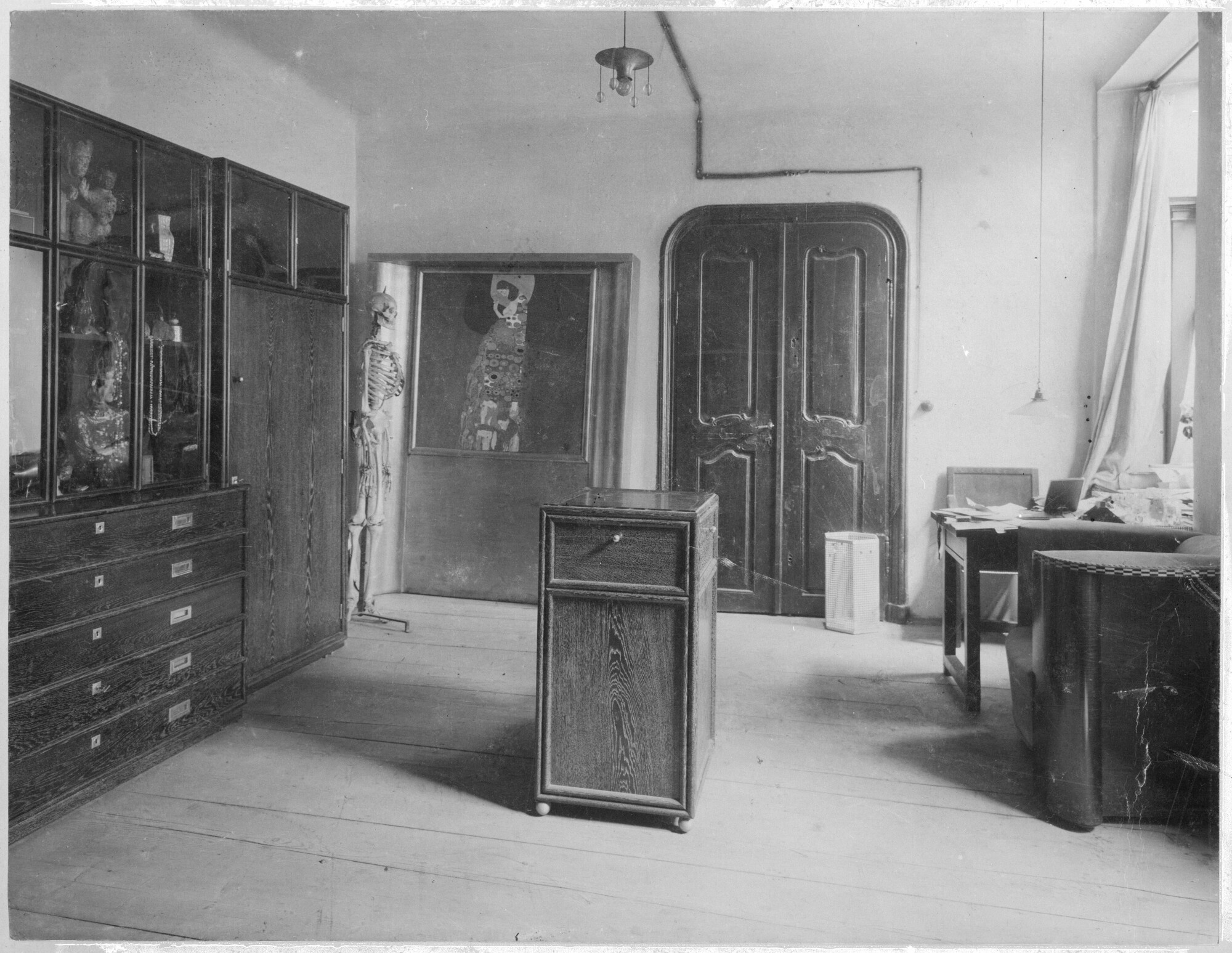

Moriz Nähr: Anteroom of Gustav Klimt's studio in Josefstädter Straße, May 1911, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Gustav Klimt: Hope II (Vision), 1907/08, The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder and Helen Acheson Funds, and Serge Sabarsky

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Although the work had already been exhibited in 1909, Klimt revised it several times afterwards. It was not uncommon for the artist to make further changes to supposedly finished paintings if they were not yet sold. A picture of Klimt’s studio at No. 21 Josefstädter Straße taken by the photographer Moriz Nähr in 1911 shows the original version of the painting leaning against the wall next to a skeleton model. Comparing the final version of the work with the photograph of the artist’s studio from 1911 shows that Klimt made various changes between 1911 and 1914. The most conspicuous modifications concern the pregnant woman’s circular nimbus, which Klimt eventually reduced to a semicircle, and the handling of the background.

The painting found an admirer in Eugenia Primavesi. She had seen it in the artist’s studio in 1914 and had been thrilled by it. That same year, she received the work from her husband Otto as a Christmas present. On New Year’s Day, Eugenia wrote:

“On Christmas Eve, a picture by Klimt came as a surprise, the one I liked so much when visiting his studio some time ago on a Saturday – Vision it is called, and I am very pleased with it.”

When the work was purchased and installed at the Villa Primavesi in Olomouc, the lengthy painting process thus came to a sudden end.

Gustav Klimt: Danaё, 1907/08, private collection

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Danaë

Like in Judith I (1901, Belvedere, Vienna), in the painting Danaë (1907/08, private collection) Klimt made use of a traditional theme from art history, which he revisited for the sake of depicting sensual eroticism. Klimt thus reinterpreted the mythological tale of Zeus ravishing the beautiful Danaë during her sleep in the form of a shower of gold. Due to the protagonist’s closed eyes and softly parted lips, with her hand disappearing between her thighs, the scene of a rape becomes an erotic act of love. As if in ecstasy, Danaë pulls her blanket to her breast. Contemporaries such as Fritz Waerndorfer already noticed the protagonist’s erotic pleasure when Klimt presented the work for the first time at the “Kunstschau Wien” in 1908:

“A Danaë penetrated by a golden stream as if it were a giant penis [note: the German original uses the obscene dialect expression “Mordsschwaf”], which gives her ultimate pleasure.”

Insight into the Vienna Art Show 1908, June 1908 - November 1908

© Heidelberg University Library

Bruno Reiffenstein (?): Insight into the Villa Ast, circa 1913, MAK - Museum für angewandte Kunst, Bibliothek und Kunstblättersammlung

© Heidelberg University Library

In terms of form and content, this picture is reminiscent of Klimt’s numerous drawings of masturbating women, which became increasingly common, especially in his later years. Moreover, the crouching posture and the closed eyes are reminiscent of an erotic dream. The painter seems to have been primarily concerned with the display of the sensation of sexual pleasure, independent of the presence of a man. The mythology surrounding Zeus – in which the god never appears in human form – probably played into Klimt’s hands here, as he took up this theme again in his erotic Leda (1917, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945).

Artists had gotten away with creating erotic depictions for decades under the cloak of mythological iconography, thereby circumventing the period’s moral censorship. After all, watching a sleeping woman with her left hand disappearing between her thighs does not lack a voyeuristic touch. Édouard Manet had already been heavily criticized for a similar subject in his work Olympia (1863, Musée d’Orsay, Paris).

Once again, gold plays an important role here. The precious metal preferred by Klimt during his Golden Period is not only found in the brocade elements of the violet fabric – which are sometimes also interpreted as blastocysts, i.e. embryonic cells supposed to symbolize Danaë’s impregnation; as golden rain it even becomes the objectified divine, thus detaching itself from its function as a decorative element.

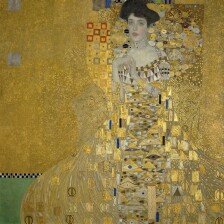

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, 1907, Neue Galerie New York, Acquired through the generosity of Ronald S. Lauder, the Heirs of the Estates of Ferdinand and Adele Bloch-Bauer, and the Estée Lauder Fund

© APA-PictureDesk

Adele Bloch-Bauer, photographed by Friedrich Viktor Spitzer, 1906, in: Photographische Rundschau und photographisches Centralblatt. Zeitschrift für Freunde der Photographie, 22. Jg., Heft 3 (1908).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Insight into the anniversary exhibition in Mannheim, May 1907 - October 1907

© Heidelberg University Library

Adele Bloch-Bauer I

“[B]ut with Klimt, there are flashes, thunders, and hailstorms of glistening gold, an entire Nibelung treasure descending, cracking and rattling, a golden downpour!”

Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907, Neue Galerie New York) is not only one of the painter of women’s most famous portraits, but certainly also a masterpiece of the Golden Period. Using gold leaf and ornamentation, the artist transformed his sitter into a “sparkling jewel,” a disembodied apparition. Klimt’s sources of inspiration ranged from Byzantine mosaics to late 19th-century painting and traditional Japanese art. Klimt was thus very much in line with the style of his time, for Hans Makart, Fernand Khnopff, and the Pre-Raphaelites also loved the precious metal.

Klimt’s first portrait of the then 26-year-old Adele Bloch-Bauer is one of his most prominent paintings and a masterpiece of the Golden Period. A letter from Adele Bloch-Bauer proves that Klimt was first commissioned with the portrait as early as the summer of 1903:

“My husband subsequently decided to have my portrait painted by Klimt, who, however, can only set to work this coming winter.”

But for reasons unclear, the Bloch family had to wait considerably longer for the portrait, which had originally been intended as a gift to Adele’s parents for their wedding anniversary. It was not until 1907 that Klimt completed Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, with a frame based on a design by Josef Hoffman.

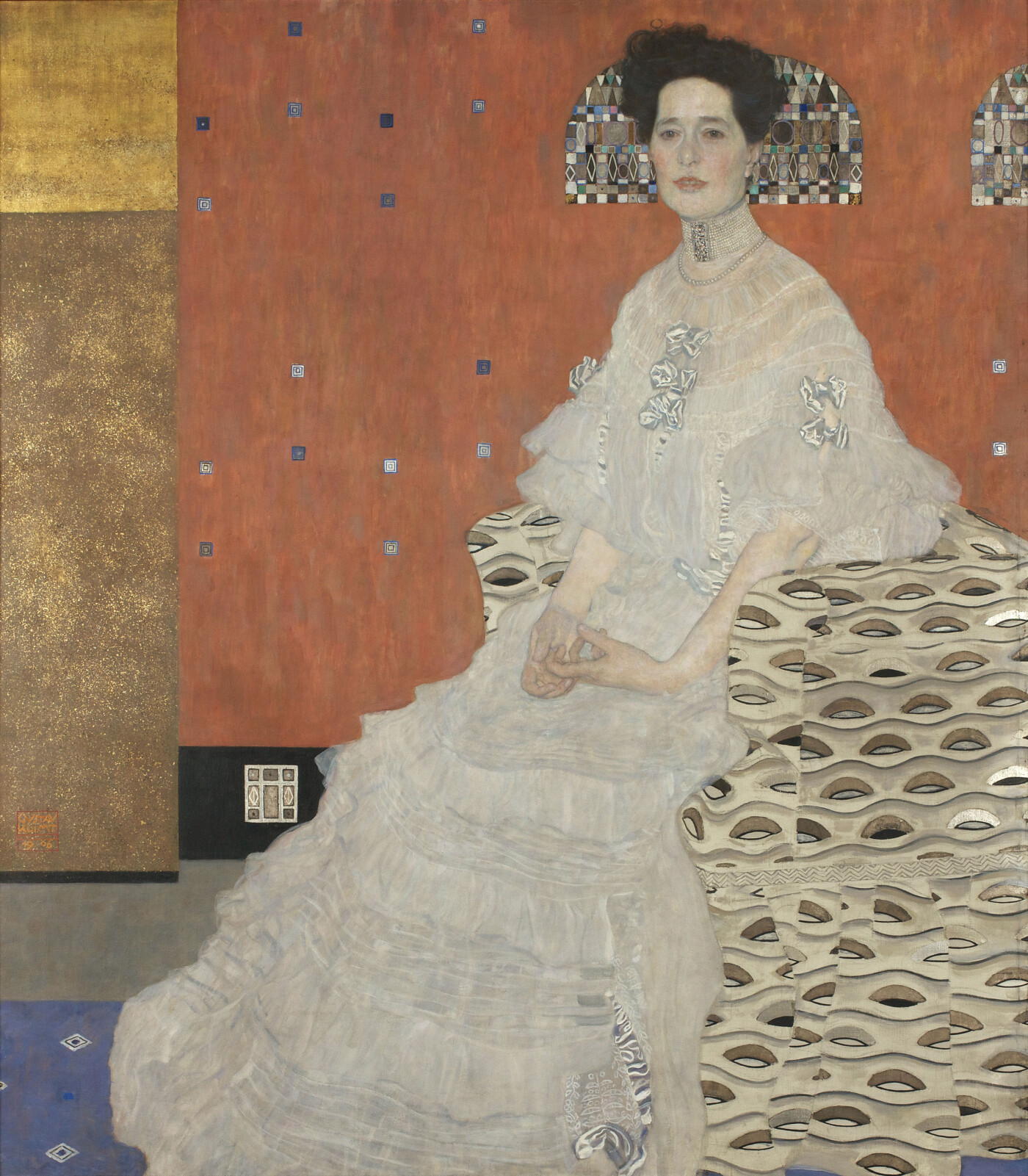

Like with The Three Ages of Woman (1905, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Rome) and Portrait of Fritza Riedler (1906, Belvedere, Vienna), contemporaries referred to the work as “mosaic picture.” This term refers to the arts-and-crafts character of the three paintings, as well as Klimt’s fusion of painting and decorative arts elements, an approach he would subsequently carry to an as yet unparalleled peak in the Stoclet Frieze (1905–1911, private collection). The mosaic character of the works was fed by impressions Klimt had gathered during a trip to Italy in 1903, when he visited the cathedral of Ravenna. There it was for the first time that he saw the golden Byzantine “mosaics of a splendor unheard of,” which had a lasting impact on the entire output of his Golden Period.

The use of gold and the understanding of a painting as decorative ornament reached unknown heights in Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I. With its golden spirals, the upholstered chair optically blurs into the background, as does the sitter’s dress. Gold becomes the dominant pictorial component, broken only by a few accents of color. All three-dimensional objects are noticeably abstracted, to which the sitter’s naturalistically rendered head and hands stand in stark contrast. Orthodox icons, which have always combined painted images of saints with golden metal frames, may have served as an inspiration here.

Klimt thus elevates the sitter to the status of an icon, taking her to divine spheres, while, at the same time, making a statement of splendor and wealth. In this way, he presented the wealthy bourgeoisie on the rise in a way that had previously been reserved for the nobility.

Having finished his epochal Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, Klimt would not paint another commissioned portrait for four years. Work on the Stoclet Frieze and his position as president of the “Kunstschau” probably took up too much of his time to accept any more assignments. By the time Klimt painted another portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer in 1912, he had already left the Golden Period behind and turned to bright colors and exotic, Asianizing motifs.

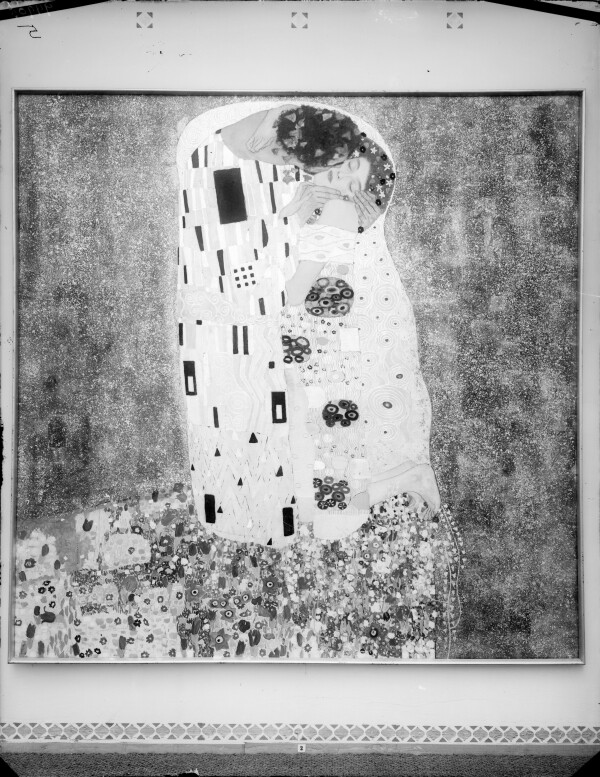

Gustav Klimt: The Kiss (Lovers), 1908/09, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

The Kiss (Lovers)

The painting The Kiss (Lovers) (1908/09, Belvedere, Vienna) can undoubtedly be considered Klimt’s climax and endpoint of the Golden Period. Since the use of gold in Klimt’s paintings, as has already been pointed out, was based on Byzantine mosaics and the tradition of icon painting, The Kiss is also frequently referred to as “monumental icon.”

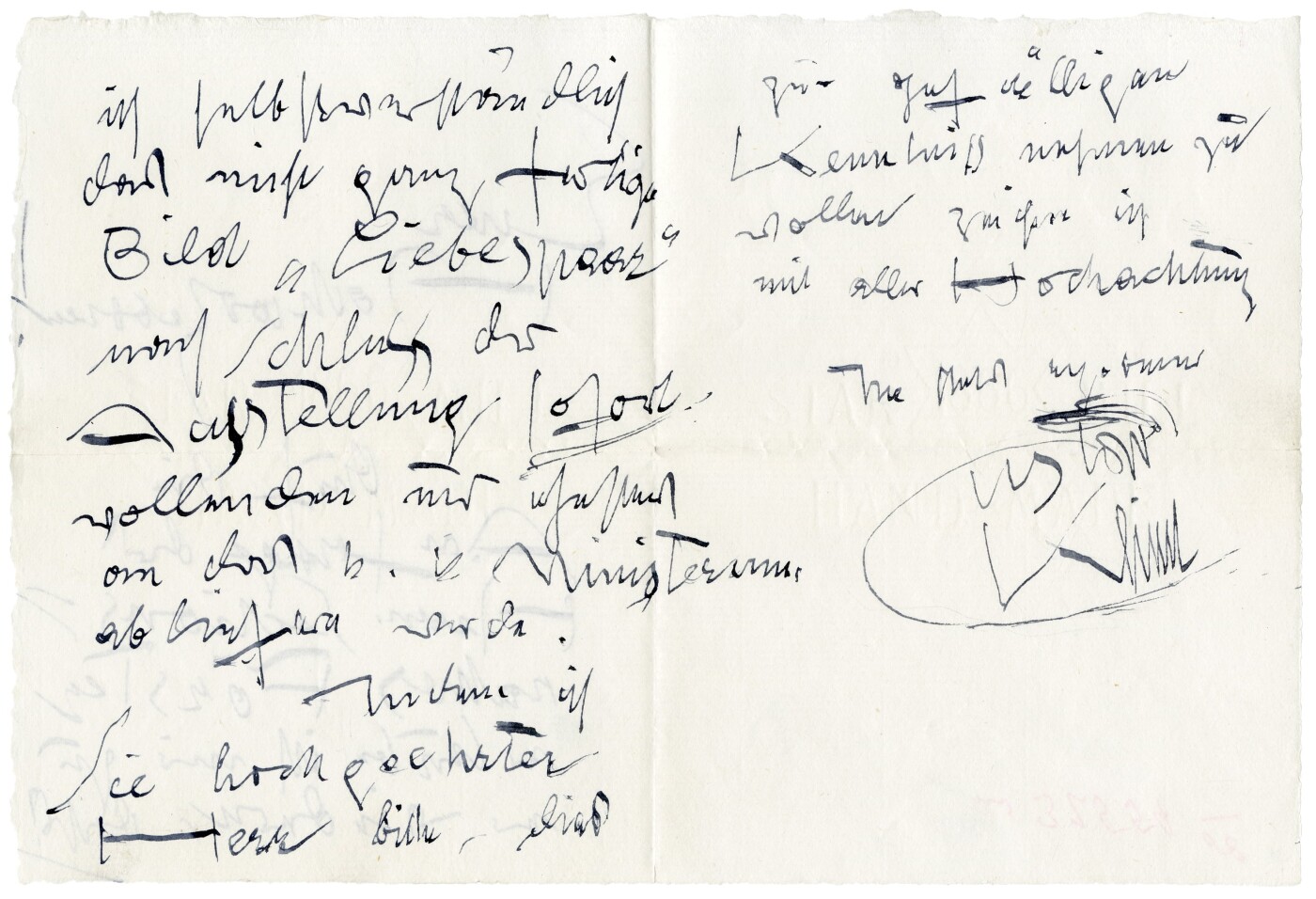

The painting was exhibited for the first time at the “Kunstschau Wien” in 1908 under the title The Lovers. The work, which was still unfinished at the time, was purchased for the Modern Gallery by the Imperial-Royal Ministry of Culture and Education. After its completion in 1909, Klimt handed it over to the ministry against payment of 25,000 crowns (approx. 155,700 euros).

“This kiss to the whole world” is a line from the final movement of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 and was an inspiration for Gustav Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze (1901/02, Belvedere, Vienna). It is this very motif of the kiss of a tightly embracing man and woman that Klimt developed further in this painting. Two lovers are shown kneeling on a cliff covered with flowers against a flickering golden backdrop typical of the Golden Period. The man bends down to the kneeling woman to kiss her on the cheek.

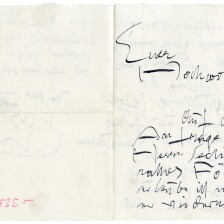

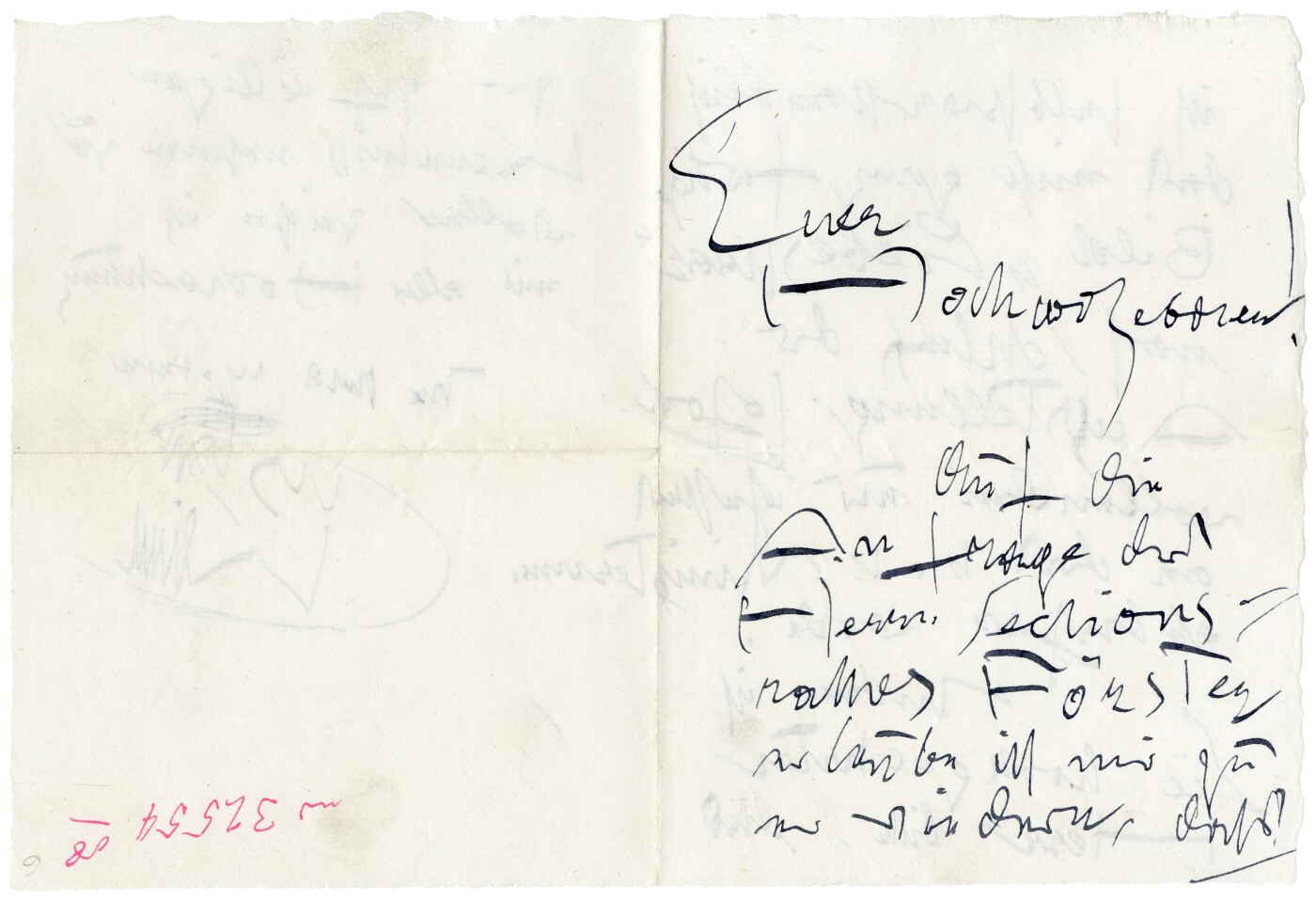

Letter and Envelope from Gustav Klimt to the Imperial-Royal Ministry of Culture and Education, Vienna, 16 July 1908

-

Gustav Klimt: Letter with envelope from Gustav Klimt in Kammer am Attersee to the Imperial-Royal Ministry of Culture and Education in Vienna, 07/16/1908, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

Gustav Klimt: Letter with envelope from Gustav Klimt in Kammer am Attersee to the Imperial-Royal Ministry of Culture and Education in Vienna, 07/16/1908, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

© Austrian State Archives, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Letter with envelope from Gustav Klimt in Kammer am Attersee to the Imperial-Royal Ministry of Culture and Education in Vienna, 07/16/1908, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

Gustav Klimt: Letter with envelope from Gustav Klimt in Kammer am Attersee to the Imperial-Royal Ministry of Culture and Education in Vienna, 07/16/1908, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

© Austrian State Archives, Vienna

Insight into the Vienna Art Show 1908, June 1908 - November 1908

© BSB

Moriz Nähr: The kiss (lovers), June 1908 - November 1908, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Insight into the International Art Exhibition in Rome, March 1911 - December 1911, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Archiv

© Belvedere, Vienna

In his composition, Klimt worked out the differences between man and woman through stark contrasts. The man’s dark skin, the hard, black rectangles of his robe, and the wild, rough ivy in his hair emphasize a stereotypical masculine hardness and rugged natural force, while the woman, with her fair skin, floral dress featuring round, feminine patterns, and delicate flowers in her hair, reflects a beautiful, gentle kind of nature. The relationship between man and woman is also clearly defined. Kneeling protectively over her, he holds her in a tight embrace, while she nestles trustingly against him with her eyes closed. For all that separates the two sexes, the gold acts as a unifying element. The two robes and the cosmic background blend in to create a single foil, with man and woman becoming one.

Klimt had already accomplished such a synthesis of the individual pictorial elements into a flat, abstract mass the previous year in Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I. Edvard Munch’s woodcut The Kiss (1895, Albertina, Vienna), in which man and woman seem to share the same face, could have served as a model for the fusion of man and woman. The subject of the man holding the vulnerable woman in a protective embrace already dates back to 1902 and the first sketches for Hope I.

It is often assumed that the lovers are Gustav Klimt himself and his longtime companion Emilie Flöge. In fact, there is a brooch featuring the depiction of an embrace (30 August 1908, private property) that reproduces the Kiss motif in a modified version. The parchment support is inscribed to the right and left of the protagonists, identifying them as “Gustav” and “Emilie” respectively. A preliminary study for this brooch that has come down to us in one of Klimt’s sketchbooks (Klimt-Foundation, Vienna) is likewise inscribed “Emilie.” It therefore seems quite plausible that Klimt saw himself and Emilie Flöge in the lovers, but anonymized the protagonists in favor of a universalization of the motif. This would also be supported by the fact that Klimt painted over the man’s facial hair after the “Kunstschau Wien” of 1908 and thus removed the figure even further from the bearded artist.

Klimt repeated the motif of the embrace one more time in the panel of “Fulfillment” in the Stoclet Frieze, revisiting the composition of The Kiss in terms of both content and form.

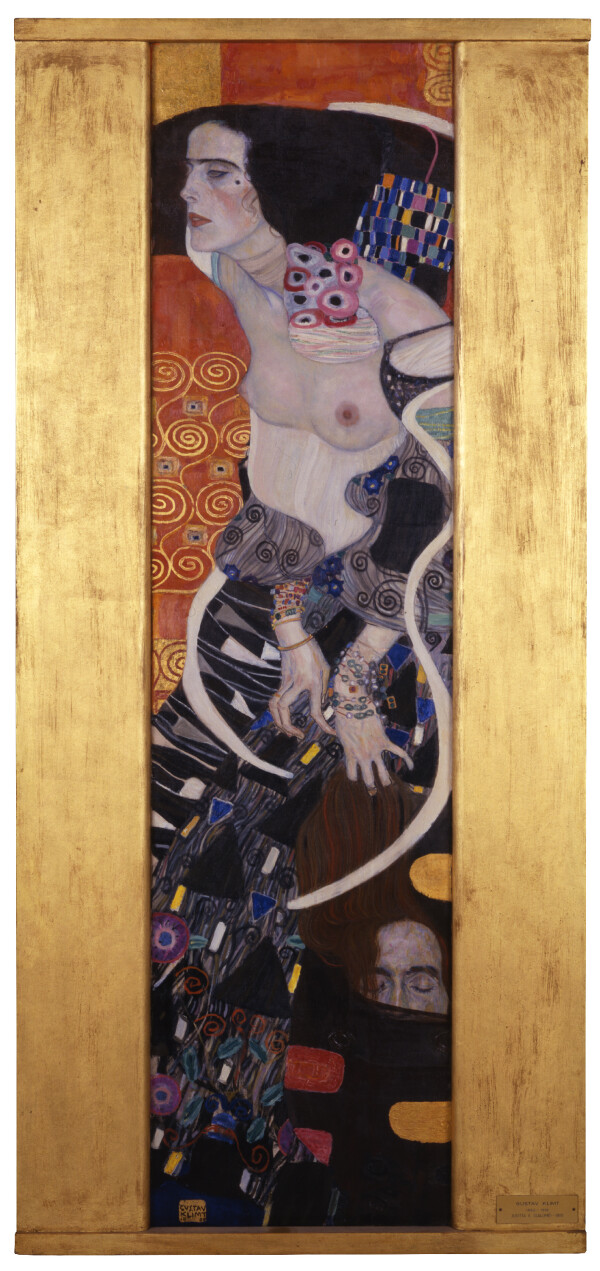

Gustav Klimt: Judith II (Salome), 1909, Ca'Pesaro - Galleria Internazionale d'Arte Moderna

© Photo Archive - Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia

Judith II (Salome)

In 1909, Klimt once again created a threatening, man-eating femme fatale. As in Judtih I, the interpretation of the protagonist in Judith II (Salome) (1909, Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna Ca’ Pesaro, Venice) oscillates between the two biblical female figures. Despite all this, when it was first presented at the “Internationale Kunstschau Wien” in 1909, the picture was exhibited under the title of Judith. The painting still bore this title in 1910 at the Venice Biennale, where it was purchased by the Venice Municipal Gallery. The painting was thus never officially titled “Salome” by the artist himself, although much would speak in favor of this association in terms of form. The dancer with the exposed décolleté, dull eyes, and fingers cramped into claws looks much more like the seductive dancer than the virtuous avenger.

Around 1900, the figure of Salome increasingly found its way back into the visual arts. Particularly Oscar Wilde’s drama Salome, published in 1896, caused a genuine hype around the scandalous dancer. Klimt was thus able to draw from a veritable repertoire of models for his Judith/Salome. Besides pictures by Aubrey Beardsley, Lovis Corinth, and Gustave Moreau, Franz Stuck, whose works had already been an impetus for Judith I, had also created a cycle of three paintings on the theme of Salome in 1906. Adaptations of Salome also circulated in the performing arts. Between 1906 and 1907, three of the most famous dancers, Maud Allan, Ruth St. Denis, and Mata Hari, appeared in Vienna as seductive femmes fatales. It is highly likely that Klimt, who regularly frequented the theater and was working on his studies for the dancer in the Stoclet Frieze, attended some of these performances.

Klimt’s interest appears to have still been the same as in Judith I, painted almost a decade earlier. She is a sexually permissive femme fatale who appeals to the viewer, but at the same time sends out a warning through the severed male head, which suggests imminent danger. Here, however, the male component is once again pushed to the margin of the picture, taking a subordinate role. The depiction combines the sexual act and killing, pleasure and suffering, and thus calls into question the gender roles around 1900.

What is new, on the other hand, is Klimt’s interest in the movement of the figure. The motif of dancing allows him to use abstract positions of the body and billowing, flamboyantly patterned garments. What is typical of the Golden Period is the contrast between the soft, naked skin and the flat bands of patterned fabric more or less concealing corporeality. Fitted into a narrow vertical format enclosed by thick golden framing lines on the sides, the woman with her dark hair and broad hairdo, artificial posture, and the multilayered lengths of fabric, is formally strongly reminiscent of Japanese woodblock prints of dancing geishas. The woodcut The Courtesan by Keisai Eisen could have served as a model. Vincent van Gogh had already used it in his Japonaiserie Oiran (1884, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam). Van Gogh’s oil painting mirrors the original woodcut, thus showing the figure in the same position as Judith II. Klimt may therefore also have been based on Van Gogh’s adaptation of the subject.

Further contents

Literature and sources

- Catherine Dean: Klimt, New York 1996.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt 150 Jahre, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 13.07.2012–27.01.2013, Vienna 2012.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band II, 1904–1912, Salzburg 1982.

- Tobias G. Natter, Gerbert Frodl (Hg.): Klimt und die Frauen, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 20.09.2000–07.01.2001, Cologne 2000.

- Daniela Hammer-Tugendhat: Judith, in: Tobias G. Natter, Gerbert Frodl (Hg.): Klimt und die Frauen, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 20.09.2000–07.01.2001, Cologne 2000, S. 220–225.

- Hans Bisanz: Zur Bildidee „Der Kuss“ – Gustav Klimt und Edvard Munch, in: Tobias G. Natter, Gerbert Frodl (Hg.): Klimt und die Frauen, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 20.09.2000–07.01.2001, Cologne 2000, S. 226–234.

- Brief von Fritz Waerndorfer in Wien an Carl Otto Czeschka (06/05/1908).

- Brief von Eugenia „Mäda“ Primavesi sen. in Winkelsdorf an Anton Hanak (01.01.1915). Mappe 17.

- Franz Smola: Il bacio e Le tre età della donna. due capolavori di Gustav Klimt a confronto, in: Maria Vittoria Marini Clarelli (Hg.): Klimt. La Secessione e l’Italia, Museo di Roma, Ausst.-Kat., Museo di Roma (Rome), 27.10.2021–27.03.2022, Rome 2022, S. 63-76.

- Felix Salten: Gustav Klimt – Gelegentliche Anmerkungen. mit Buchschmuck von Berthold Löffler, Leipzig 1903.

- Sabine Brauckamnn: Fertilization Narratives in the Art of Gustav Klimt, Diego Rivera and Frieda Kahlo: Repression, Domination and Eros among Cells, in: Leonardo, Band 44 (2011).

- Berta Zuckerkandl: Ankauf von Klimt-Werken durch Staat und Land, in: Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, 04.08.1908, S. 3.

- Armin Friedmann: Kunstschau 1908, in: Wiener Zeitung, 09.06.1908, S. 1.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Schlafende Schönheit. Meisterwerke viktorianischer Malerei aus dem Museo de Arte de Ponce, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna), 14.06.2010–03.10.2010, Vienna 2010.

- Ansichtskarte von Gustav Klimt in Ravenna an Emilie Flöge in Wien (12/02/1903).

- Brief von Adele Bloch-Bauer in Elbekosteletz an Julius Bauer (22.08.1903). Autogr. 577/52-1, .

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Klimt and the Women of Vienna's Golden Age. 1900–1918, Ausst.-Kat., New Gallery New York (New York), 22.09.2016–16.01.2017, London - New York 2016.

- Renée Price (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. The Ronald S. Lauder and Serge Sabarsky Collections, Ausst.-Kat., New Gallery New York (New York), 18.10.2007–30.06.2008, Munich 2007.

- Alfred Weidinger: 100 Jahre Palais Stoclet. Neues zur Baugeschichte und künstlerischen Ausstattung, in: Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt – Josef Hoffmann. Pioniere der Moderne, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna) - Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 25.10.2011–04.03.2012, Munich 2011, S. 202-251.

Floral Mosaics Continued

Litzlberg on the Attersee

© Austrian National Library

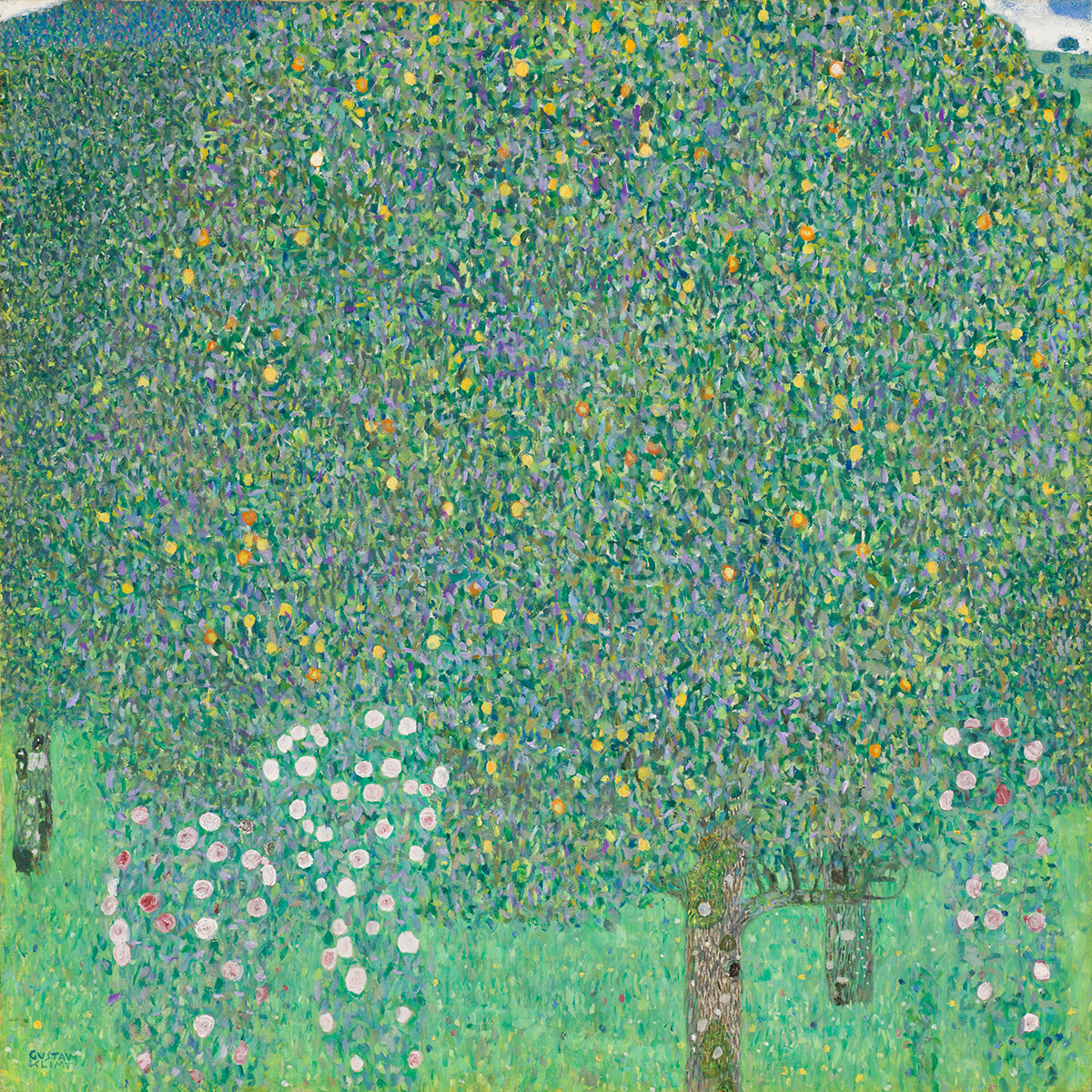

Gustav Klimt: Poppies in Bloom, 1907, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

In 1907 Gustav Klimt completed another three landscape paintings with which he paid tribute to the floral splendor around the Attersee. The sunflower in particular inspired him in his homage to the beauty of nature. The motif of the wild meadow had once again made its way into Klimt’s work.

In 1907 Gustav Klimt stayed at the Bräuhof in Litzlberg for the last time. The landscape paintings of that year suggest that Klimt found the motifs for his paintings in the immediate surroundings of his domiciles. Poppies in Bloom (1907, Belvedere, Vienna) might therefore show the view from the inn’s balcony. The painter probably came across the cottage garden he captured in three of his oil paintings dating from his stays on the Attersee near the farmstead of Anton Mayr. Before presenting them at the “Kunstschau Wien,” which opened on 1 June 1908, Klimt finished his works in his studio in Vienna.

Poppies in Bloom (1907)

Poppies in Bloom may have been the first of the three landscape paintings from the summer of 1907. In terms of both composition and motif, Klimt harked back to Flowering Meadow (1908, private collection) and Orchard (A Summer’s Day) (1902/03, The Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania). In all of the three works, Klimt chose a high horizon to be able to indulge in Pointillist expanses of meadows interspersed with flowers. All of these landscapes show a cloudy sky. The eye, led into the far distance, travels freely over grasses and blossoms; the space is structured by solitary trees. In Poppies in Bloom, Klimt carried his preoccupation with Pointillism to a climax: the diminishing size of the painted flower-heads – in terms of botany, one can identify poppies and daisies – and the growing dimension of the fruit trees in the foreground give the impression of a continuous space. This was counteracted by Klimt through the uniformity of figures and ground, trees and meadow. He structurally adjusted the foliage, shimmering in shades of green and violet, the orange-yellow apples, and the flowers. Only the somewhat looser brushwork suggests the large size of the treetop.

Moriz Nähr (?): Insight into the Vienna Art Show 1908, June 1908 - November 1908

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: The Sunflower, 1907/08, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, 2012, bequest Peter Parzer, Vienna

© Belvedere, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Cottage Garden, 1907, private collection

© Sotheby's

When the painting was exhibited for the first time at the “Kunstschau Wien” of 1908 under the title of Poppies in Bloom, critic Franz Servaes described his impressions poetically:

“The voluptuous cornucopia of nature, an atmosphere heavy with trepidation, the paradisiacal tranquility of a daydream not of this world – hardly has this been expressed as sublimely and as vibrantly as by Klimt; often with lines of blissful simplicity and stillness; at times with colors burning as if in astral luminosity.”

Klimt sold the painting within the first week of the exhibition, as the “Kunstschau” management announced in several Viennese newspapers, including Das Vaterland, Wiener Zeitung, and Die Zeit.

Solitary Sunflower and Superb Cottage Garden

In The Sunflower (1907/08, Belvedere, Vienna), an ordinary composite is fabulously elevated to resemble the portrayal of a woman. Klimt has heightened the anthropomorphic form of the single-headed sunflower by making its leaves look like a reform dress. As if on a floral throne, the sunflower stands at the center of the picture.

Reminiscent of the 1906 fashion photographs with Emilie Flöge, the plant seems like nature’s stand-in for the faithful companion in her precious clothes. Since Klimt strictly distinguished between the disciplines of portraiture and landscape, the work The Sunflower is the closest approximation between the two genres in the Jugendstil painter’s oeuvre. At the height of the Golden Period, Klimt enhanced the sunflower’s “portrait” with a myriad of golden dots.

Cottage Garden with Sunflowers (1907, Belvedere, Vienna) shows a carpet-like all-over that covers the entire expanse of the picture. As in his portraits, the painter closed the composition behind a narrow strip of space running parallel to the picture plane. Flower heads cropped along the margins give the impression of a zoomed-in view of a larger whole. Klimt’s “viewfinder” was essential for the choice of detail. The cottage garden assembles different species of flowers in bright, contrasting colors, which was considered a particular characteristic of peasant garden art around 1900. In Cottage Garden (1907, private collection), Klimt clarified the arrangement of the flowers by choosing a pyramidal composition.

Starting the following year, Klimt’s artistic attention would focus on Kammer Castle on the Attersee.

Further contents

Literature and sources

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007.

- Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sommerfrische am Attersee 1900-1916, Vienna 2015.

- Stephan Koja: Die Sommer in Litzlberg, in: Stephan Koja (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Landschaften, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 23.10.2002–23.02.2003, Munich 2002, S. 64-70.

- Laura Erhold: »Ausheiterung, Wiesen voll von Sonnenblumen«. Wenn Blumen sprechen. Florale Symbolik von der Antike bis zu Gustav Klimt, in: Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Florale Welten, Vienna 2019, S. 84-101.

- Das Vaterland. Zeitung für die österreichische Monarchie, 14.06.1908, S. 9-10.

- Wiener Zeitung, 14.06.1908, S. 9.

- Die Zeit, 14.06.1908, S. 3.

Views of Kammer Castle on the Attersee

Kammer-Seewalchen am Attersee, around 1910

© Austrian National Library

Between 1908 and 1912, Klimt stayed at the Villa Oleander in Kammerl, which was part of the district of Kammer-Schörfling, for his summer vacation. Several views of the formerly moated Kammer Castle date from this period. In them, Klimt gradually translated the multifaceted image of nature into a stylized, flickering pictorial order.

Numerous photographs show Klimt together with the Flöge family in the garden of the Villa Oleander in Kammerl. A private villa, it belonged to the larger complex of the Hôtel Seehof in the immediate vicinity of the castle and from 1908 on functioned as domicile for the “Kammerl Colony.” If Klimt hat mainly chosen brilliantly colorful cottage gardens and wild poppy meadows as themes for his pictures there, this first summer at the Villa Oleander increasingly fired his interest in cropped architectural motifs as integral part of his paintings. This interest of his manifests itself in his views of Kammer Castle.

The Impressionists’ preference for landscape motifs featuring stretches of water played an inspiring role in the artist’s tendency toward stylization, which was intensified by the symmetry of the reflections. In 1908 and 1909 he thus painted two views of Kammer Castle and two views of its surrounding gardens, dominated by imposing trees.

Gustav Klimt and the Flöge Family in Front of the Villa Oleander, Summer 1908

-

Gustav Klimt in the garden of Villa Oleander, summer 1908, Klimt Foundation

Gustav Klimt in the garden of Villa Oleander, summer 1908, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt with the Flöge family in the garden of Villa Oleander, summer 1908, Klimt Foundation

Gustav Klimt with the Flöge family in the garden of Villa Oleander, summer 1908, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt with the Flöge family in front of Villa Oleander, summer 1908, Klimt Foundation

Gustav Klimt with the Flöge family in front of Villa Oleander, summer 1908, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Kammer Castle on Lake Attersee, around 1910

© Austrian National Library

Gustav Klimt: Kammer Castle on the Attersee I, 1908, Národní Galerie

© National Gallery Prague

The First View of Kammer Castle

The moated edifice of Kammer Castle was mentioned in records for the first time in the 13th century. Its central structure dates from that time. The Khevenhüller family acquired the castle in 1581. In the second quarter of the 17th century, the owners had a new castle built, which in 1710 underwent constructional changes carried out by the Linz-based master builder Johann Michael Prunner. In the late 18th century, the complex was connected with the shore through an earth bank, and an access was built in the form of an avenue.

The first painting of the series, Kammer Castle on the Attersee I (1908, Národní Galerie, Prague), shows a bipartition of the picture plane, which consists of the mirroring water surface of the lake on the one hand and the strip of the lakeside with the castle complex and the church of Seewalchen on the other. In the painting, the parish church, located on the left side behind the castle, and the monumental structure almost form a single spatial unit; the water surface as such and the actual distance between the castle and the church disappear. A system of orthogonal lines and squares ties the composition to the two-dimensional surface of the picture, evoking an impression of harmonious tranquility. Delicate light reflections characterize the atmospheric quality of Klimt’s Impressionist snapshot. Even art critic A. F. Seligmann referred to the picture in the Neue Freie Presse as “masterpiece and highlight,” when it was presented for the first time as part of the “Internationale Kunstschau” of 1909. In the subsequent year, the picture was exhibited in Prague at the “Ausstellung des Deutsch-Böhmischen Künstlerbundes” [“Exhibition of the German-Bohemian Artists’ League”], where it was immediately purchased.

Gustav Klimt: Kammer Castle on the Attersee II, 1909, private collection

© Scala Florence

Gustav Klimt: Park of Kammer Castle on the Attersee, 1909, The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Gertrud A. Mellon Fund

© Scala Florence

Gustav Klimt: Pond at the Park of Kammer Castle on the Attersee, 1909, Neue Galerie New York

© APA-PictureDesk

This view was painted from a wider distance with the aid of such optical devices as a telescope or Klimt’s “motif finder.” Actually, the boathouse of the Villa Oleander functioned as the artist’s vantage point. In a contemporary picture postcard Klimt wrote to his brother-in-law Julius Zimpel, the perspective and the distance between the Villa Oleander and the church of Seewalchen are easily recognizable.

The Castle as a Pointillist Entity

The composition of the landscape as softly undulating compartments dominates Klimt’s second painting of said series, Kammer Castle on the Attersee II (1909, private collection), for which he painted the Baroque structure from a hill in Schörfling. In this much more fragmented, Pointillist version, Gustav Klimt had the architecture merge more decidedly with the surrounding vegetation. The castle and the outbuilding in front of it almost seem to form a union, with the distance merely adumbrated by the trees placed in between. Moreover, Klimt, resorting to a varied brushwork and differentiated, self-contained fields of color, managed to define the pictorial unit as a whole. The painting was exhibited for the first time in 1910, at the “IX. Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte della Città di Venezia” [“9th International Art Exhibition of the City of Venice”].

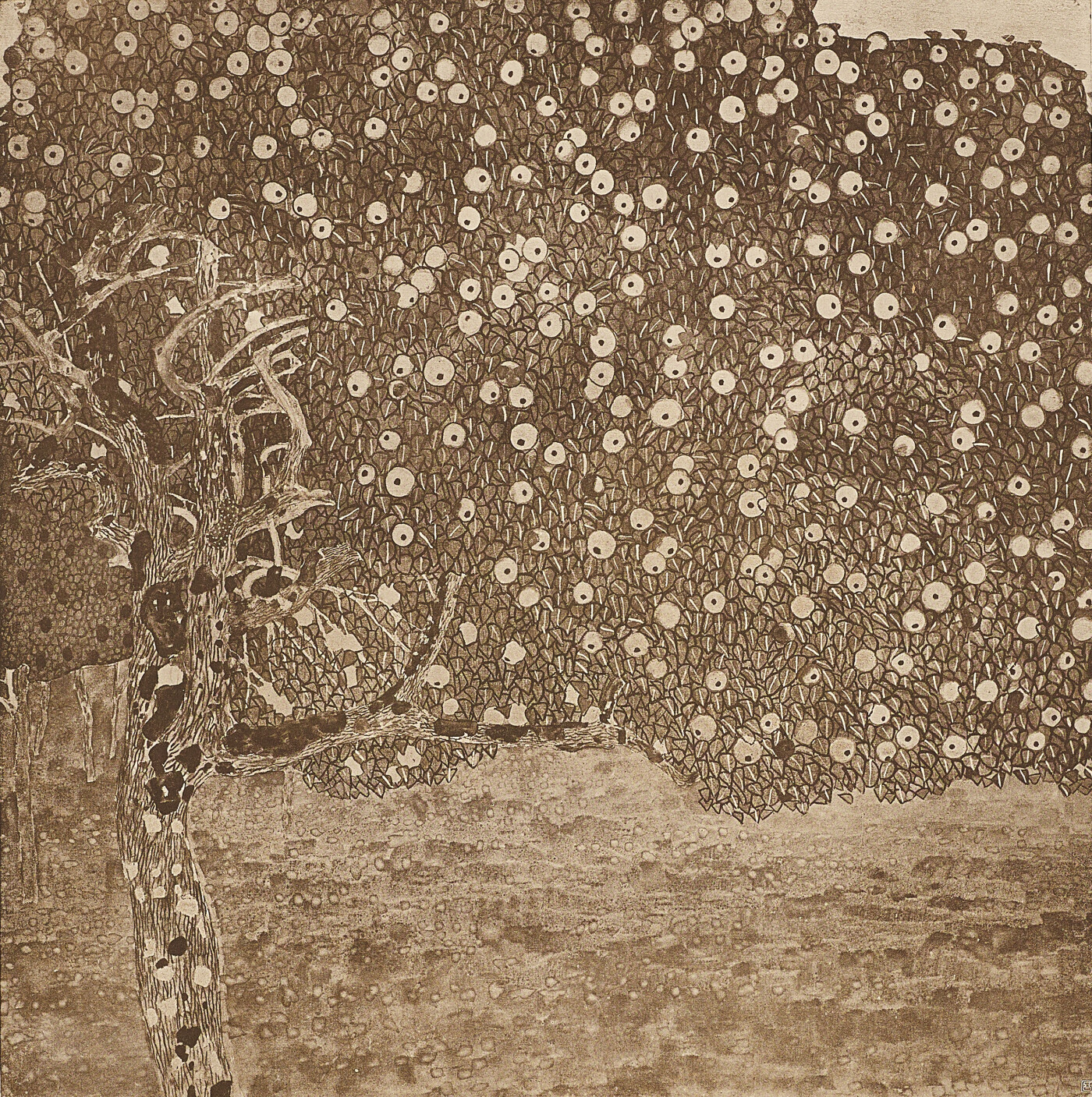

The Gardens of Kammer Castle as a Pictorial Motif

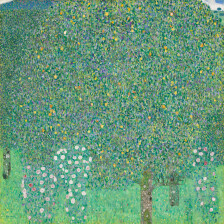

The same year in which Klimt painted Kammer Castle on the Attersee II, he also directed his attention to the gardens surrounding the castle in two works. In Park of Kammer Castle on the Attersee (1909, The Museum of Modern Art, New York), Klimt rendered the dense foliage of the treetops as a vibrant, mosaic-like wall of colors, using an incredible diversity of delicate brushstrokes. The major part of the square canvas is thus covered with the foliage of the trees. Some dark green shrubs form a hedge, which together with a tree trunk on the right, seen from close up, block the view into the depth of the picture. The lake shines through between the tree trunks only hesitantly. In this way, Klimt combined an ornamental surface with the mysterious symbolism of an Impressionist description of nature. This work, too, was first presented at the “IX. Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte della Città di Venezia.”

A shady corner amidst a cluster of trees on the shore of a pond finally inspired Klimt to juxtapose in an almost abstract fashion the reflecting green surface of the water, punctured with a myriad of light reflections, with the vibrant wall created by the foliage of deciduous trees in Pond in the Park of Kammer Castle on the Attersee (1909, Neue Galerie New York, Estée Lauder Collection). Like before, Klimt proved with this work that he knew how to combine a Pointillist manner of painting with his painted mosaics consistently filling up all forms. It has frequently been observed how Klimt contrasted diverse tones with great refinement, thereby modeling the individual segments in an extremely nuanced way. Making the troika complete, this landscape painting was also on display for the first time at the “IX. Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte della Città di Venezia.”

A number of further depictions of the castle dominating the district of Kammerl and of its surroundings would follow in 1910 and 1912.

Literature and sources

- Johannes Dobai: Gustav Klimt. Die Landschaften, Salzburg 1981.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012, S. 554-557.

- Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sommerfrische am Attersee 1900-1916, Vienna 2015, S. 62-69.

- Stephan Koja: Der Sommer in Kammer am Attersee, in: Stephan Koja (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Landschaften, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 23.10.2002–23.02.2003, Munich 2002.

- Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Florale Welten, Vienna 2019, S. 34.

- Ansichtskarte von Gustav Klimt in Kammer am Attersee an Julius Zimpel jun. in Wien, mitunterschrieben von Barbara, Pauline und Emilie Flöge, Helene Klimt sen. und Helene Klimt jun. (30.08.1908). GKA35.

- N. N.: Die Ausstellung des deutsch-böhmischen Künstlerbundes, in: Prager Tagblatt, 17.02.1910, S. 2.

- Adalbert Franz Seligman: Die Kunstschau, in: Neue Freie Presse, 29.04.1909, S. 3-4.

The Stoclet Frieze. Sketches

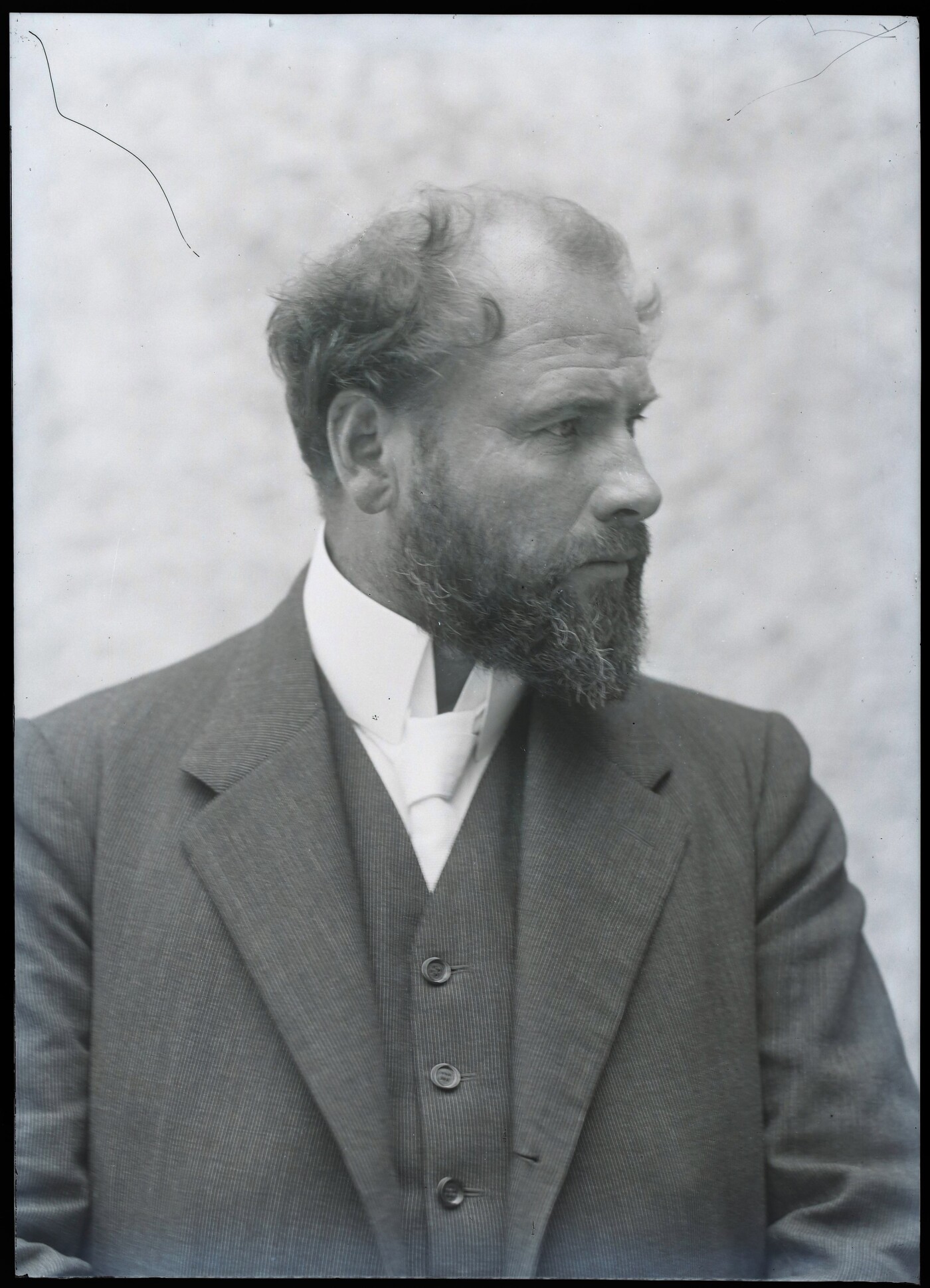

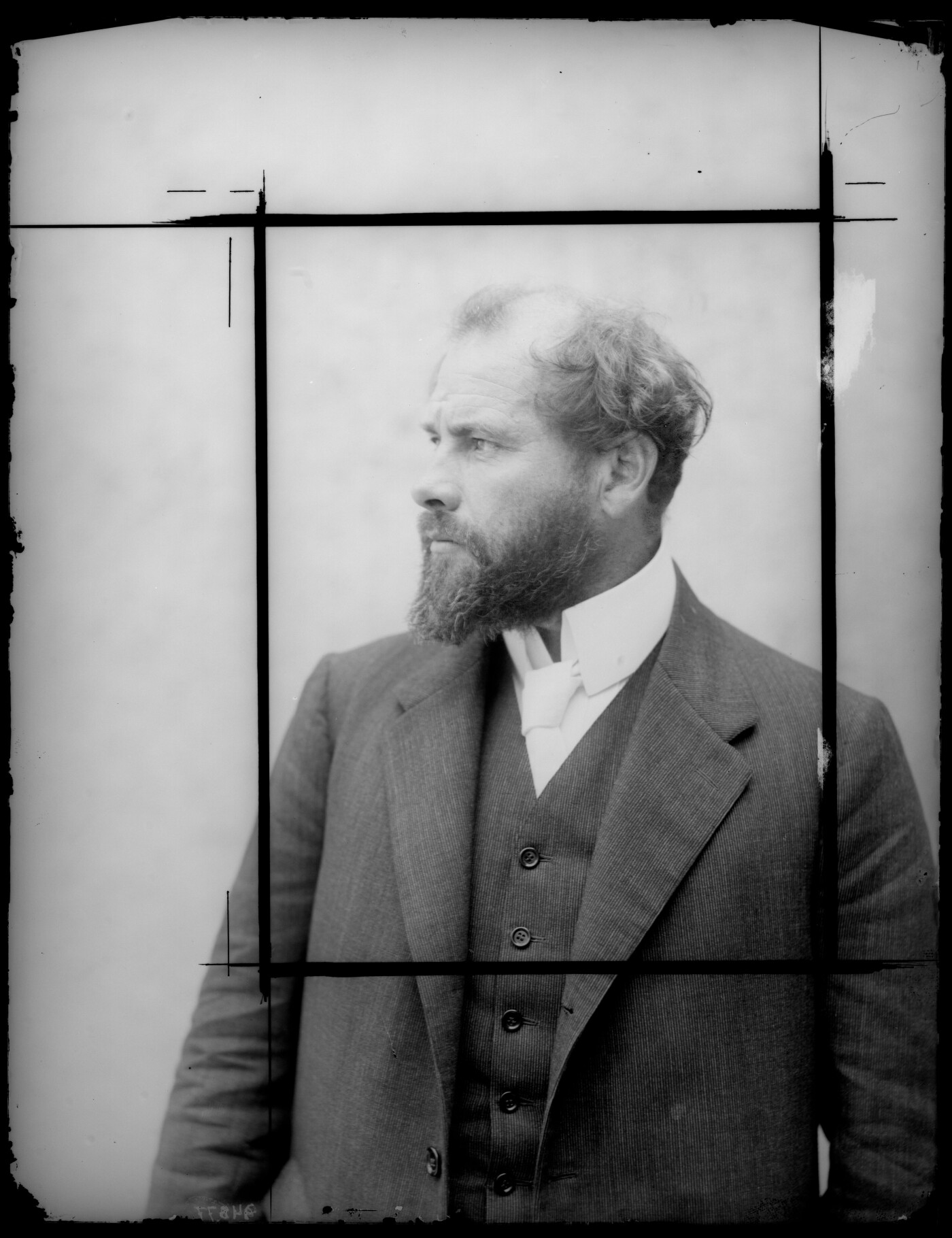

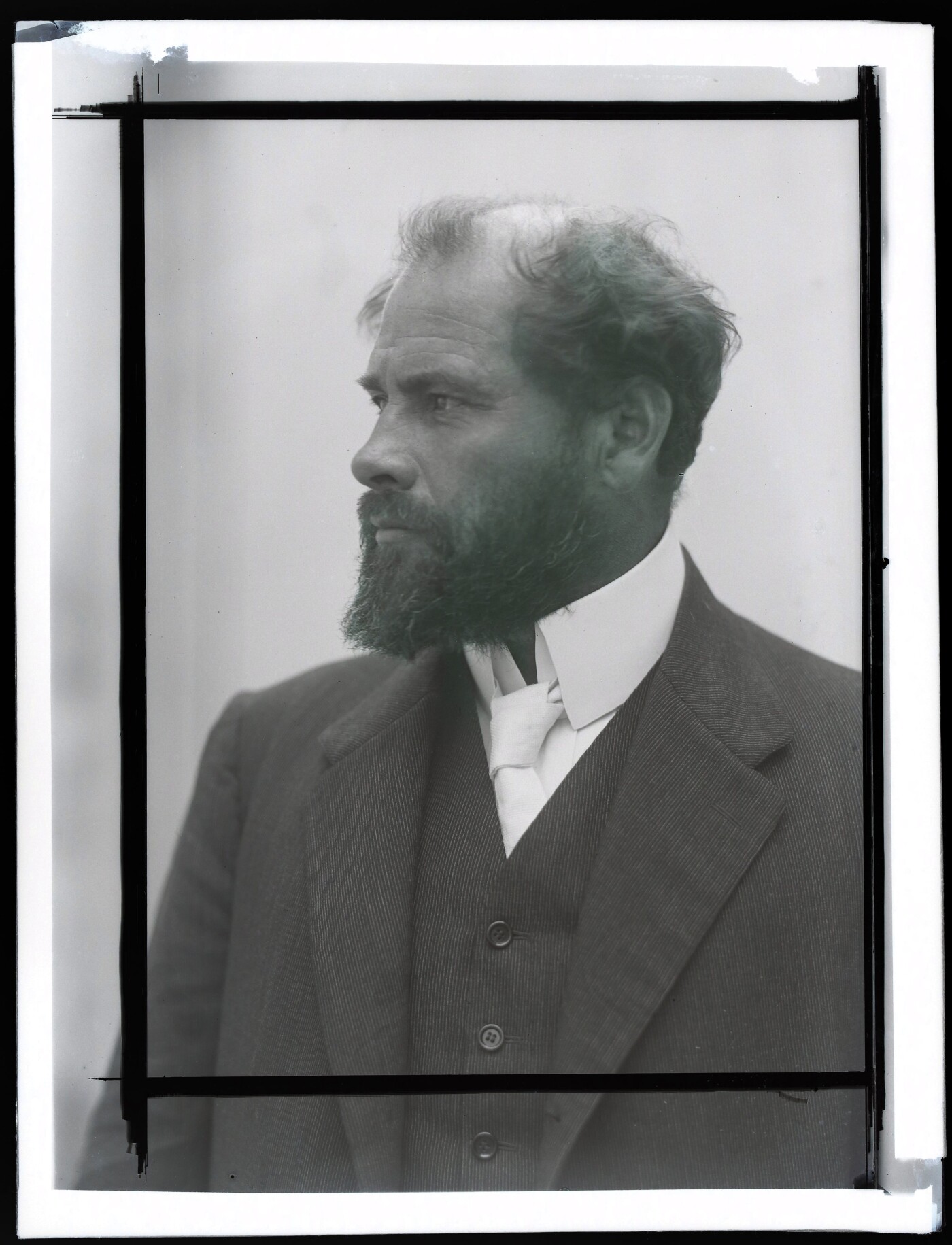

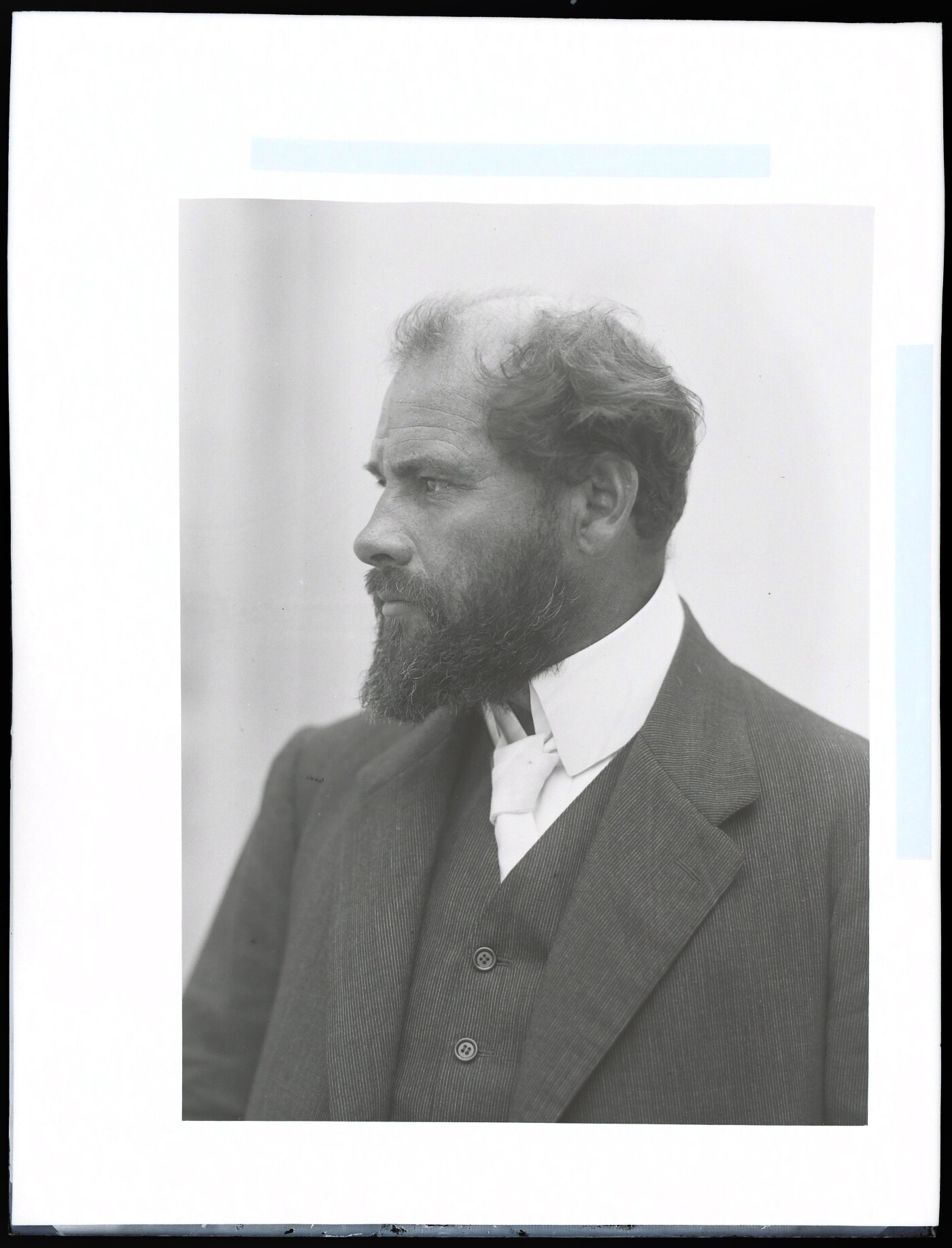

Gustav Klimt on the site of the Palais Stoclet in Brussels, 05/09/1906, MAK - Museum für angewandte Kunst, Archiv der Wiener Werkstätte

© MAK

By the summer of 1908, Gustav Klimt was working on sketches for the Stoclet Frieze. They show his path from an ornamental background with small figural insets to the large-scale Tree of Life with scenic depictions. It was not until around 1910/11 that the true-to-scale working drawings for the mosaic frieze in the dining room of the Stoclet Palace in Brussels were realized.

In 1903/04 the Belgian patrons Baron Adolphe Stoclet and his wife, Suzanne, lived in Vienna, where the art-minded couple made the acquaintance of artists of the Vienna Secession and the newly founded Wiener Werkstätte. In 1904 the close contact between the Belgian painter Fernand Khnopff, the financier Fritz Waerndorfer, the artists Carl Moll, Josef Hoffmann, and Gustav Klimt, and patron Adolphe Stoclet led to the idea of the Stoclet Palace, which was commissioned shortly afterwards. For family and business reasons, the couple returned to Brussels toward the end of 1904 and realized the project in Belgium. Josef Hoffmann designed the Stoclet Palace, which was built between 1909 and 1911 and realized with the Wiener Werkstätte in the sense of a universal work of art. The fact that Adolphe Stoclet was not only extremely wealthy, but also a recognized connoisseur of art with an exquisite taste, made it possible for Hoffmann and his colleagues to create a precious Gesamtkunstwerk or universal work of art that ranks among the most important buildings of European Art Nouveau.

Gustav Klimt: Dancer (study for "Expectation" in the stoclet frieze), 1907/08, The Albertina Museum

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

The Stoclet Frieze

Gustav Klimt was asked to design a golden frieze for the dining room, which was to extend over three walls. The Stoclet couple gave Klimt free rein in both the choice of materials and the subject matter. As documented in a letter from Fritz Waerndorfer of 17 April 1906, the painter already had a decorative artwork in mind at this early stage to solve the “spatial task” set for him. Klimt thus thought “THAT HE WOULD USE A LOT OF METAL AND ENAMEL.” In contrast to the Beethoven Frieze (1901/02, Belvedere, Vienna, on permanent loan to the Secession), he therefore conceived the wall decoration not as a mural but as intarsia. In the summer of 1907, the painter described his fears of failure in a letter to Waerndorfer of 16 August, suggesting his withdrawal from the project:

“I cannot do this. It is hard for me to say no, but I must! Better to be a ‘failure’ from the start than later, when there would be nasty consequences. I work much too clumsily. Stoklet [!] does not come easily to my mind and hand, let alone all the other things – I am either too old or too nervous or too – it must be something. I always envy Peppo [Josef Hoffmann] for his ‘work flow,’ his courage and appetite, but just this once I can’t, there are so many things ahead of me, I will make no headway like this. Dear Fritz, try to keep Peppo from scolding and growling – I feel embarrassed to have to say no, but I have no other choice if I want to keep halfway calm. Don’t be angry with me either for my constant failure.”

However, Klimt continued working on the project, and in 1908 Karl M. Kuzmany announced in his review of the “Kunstschau Wien” that Klimt intended the “decorative mural to be a strictly flat mosaic in colors.” Perhaps the Stoclet couple’s visit to Vienna and the “Kunstschau Wien” had supported this idea. Klimt designed his famous Tree of Life with rose bushes, hawks, and butterflies for the longitudinal room with a view of the garden, along with the personifications of Expectation and Fulfillment and the Knight on the narrow wall.

Sketches, Studies, and Whiteprint

Several preparatory drawings, studies, and sketches provide insights into the design process of the Stoclet Frieze. The whiteprint (1907/08, Wien Museum, S 1982: 1693) is a composition sketch squared for transfer, showing the Tree of Life wall.

Gustav Klimt: Light break for the Stoclet frieze, 1907/08, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Two standing nudes embracing, 1904/05, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

In 1908 Klimt made the three sketches – designs in landscape format – in pencil, gouache, gold, silver, and bronze on tracing paper (1908, MAK, Vienna). These could be the works on “tracing paper” Klimt told Fritz Waerndofer about in another letter:

“Under separate cover I am sending three sketches on tracing paper – created with great difficulty, they unfortunately did not come out any better. Of course they only give a most cursory impression, also in terms of color, as they are meant to be executed with gilding and material (stones, chased metal, enamel, etc.), and the sketches should be placed on white paper, having been created this way.”

It becomes noticeable at first glance that Klimt opted for strictly vertically oriented ornaments, into which he inserted the figures and the tree-of-life motif like small images in a niche. In the design drawings he already used the lovers (also interpreted as “Family” or “Early Youth”), which he realized at around the same time in The Kiss (Lovers) (1908/09, Belvedere, Vienna). In one version, the painter abandoned the carpet-like background solution and responded to Josef Hoffmann’s garden with a tree of life and scenic depictions. At this stage, he already juxtaposed the dancer with the rose bush as a counterweight to fill the length of the wall.

The whiteprint shows a version of the tree of life, dancer, and rose bush. Since the roses were drawn over the spirals of the tree, while the dancer has already been assigned a fixed place, the painter was obviously still uncertain about the compositional balance of the arrangement. By conceiving a tree spanning the entire wall surface, Klimt managed to stick to his idea of a shimmering golden background and achieve a balance between movement and the flat surface.

Both in terms of composition and handling of the materials, the Japanese borrowings Klimt had still recognizably integrated in the Beethoven Frieze can hardly be identified here anymore. In tackling the Stoclet Frieze, Klimt was increasingly concerned with questions of stylization and the use of gold and silver. This led to the climax of his Golden Period in 1907/08. It was not until 1910/11 that the Stoclet Frieze was executed according to Klimt’s true-to-scale working drawings by the highly skilled craftsmen of the Wiener Werkstätte.

Literature and sources

- Marian Bisanz-Prakken (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Ausst.-Kat., Albertina (Vienna), 14.03.2012–10.06.2012; Getty Center (Los Angeles), 03.07.2012–23.09.2012, Munich 2012.

- Anette Freytag: Der Lebensbaumfries von Gustav Klimt als künstlicher Garten im Traumhaus, in: Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Beate Murr (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Erwartung und Erfüllung. Entwürfe zum Mosaikfries im Palais Stoclet, Ausst.-Kat., MAK - Museum of Applied Arts (Vienna), 21.03.2012–15.07.2012, Vienna 2012, S. 69-87.

- Anette Freytag: Der Stoclet-Fries. Ein künstlicher Garten im Herzen des Hauses, in: Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012, S. 59-87.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt – Josef Hoffmann. Pioniere der Moderne, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna) - Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 25.10.2011–04.03.2012, Munich 2011.

- Friedrich Kurrent, Alice Strobl: Das Palais Stoclet in Brüssel, Salzburg 1991.

- Karl M. Kuzmany: Kunstschau Wien, in: Dekorative Kunst. Illustrierte Zeitschrift für angewandte Kunst, Band 16 (1908), S. 513-544, S. 513.

- Moderne Bauformen. Monatshefte für Architektur und Raumkunst, 13. Jg. (1914).

- Alexandra Matzner: Auch der Garten ist über Erwarten schön, auch die neue junge Anlage, in: Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Florale Welten, Vienna 2019, S. 103-115.

- Beate Murr: I. Die Entwurfszeichnungen zum Stoclet Fries: Ihre Entstehung, Umsetzung und Restaurierung, in: Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Beate Murr (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Erwartung und Erfüllung. Entwürfe zum Mosaikfries im Palais Stoclet, Ausst.-Kat., MAK - Museum of Applied Arts (Vienna), 21.03.2012–15.07.2012, Vienna 2012, S. 11-42.

- Fritz Novotny, Johannes Dobai (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Salzburg 1975.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band II, 1904–1912, Salzburg 1982.

- Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Beate Murr (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Erwartung und Erfüllung. Entwürfe zum Mosaikfries im Palais Stoclet, Ausst.-Kat., MAK - Museum of Applied Arts (Vienna), 21.03.2012–15.07.2012, Vienna 2012.

- Alfred Weidinger: 100 Jahre Palais Stoclet. Neues zur Baugeschichte und künstlerischen Ausstattung, in: Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt – Josef Hoffmann. Pioniere der Moderne, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna) - Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 25.10.2011–04.03.2012, Munich 2011, S. 202-251.

- Johannes Wieninger: JAPON. Zum Japonismus bei Gustav Klimt, in: Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Beate Murr (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Erwartung und Erfüllung. Entwürfe zum Mosaikfries im Palais Stoclet, Ausst.-Kat., MAK - Museum of Applied Arts (Vienna), 21.03.2012–15.07.2012, Vienna 2012, S. 96-119.

- Brief von Fritz Waerndorfer in Wien an Hermann Muthesius (17.04.1906). D 102-6647.

- Brief von Gustav Klimt an Fritz Waerndorfer (1907).

- Brief von Gustav Klimt an Fritz Waerndorfer, DLSTPW6 (um 1908-1911), .

- Christian Witt-Döring: Palais Stoclet, in: Christian Witt-Dörring, Janis Staggs (Hg.): Wiener Werkstätte. 1903–1932: The Luxury of Beauty, Ausst.-Kat., New Gallery New York (New York), 26.10.2017–29.01.2018, Munich - London - New York 2017, S. 368-410.

Kunstschau Wien 1908

Rudolf Kalvach: Poster of the Vienna Art Show 1908

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

At the “Kunstschau Wien 1908” Gustav Klimt exhibited 16 oil paintings and 18 drawings in three rooms. As president of the so-called Klimt Group, he was significantly involved in the show’s organization and program. Having sold four paintings, Klimt was one of the most successful artists of this large-scale exhibition.

To mark the diamond jubilee of Emperor Francis Joseph I’s reign, the group of artists rallying around Gustav Klimt, Josef Hoffmann, and Carl Moll organized the “Kunstschau Wien 1908.” On the site of today’s Konzerthaus and Akademietheater in Lothringerstraße in Vienna’s Inner City (1st District), a temporary showground comprising as many as 54 structures was built under the supervision of Eduard Ast, based on plans by Josef Hoffmann. In the sense of a Gesamtkunstwerk or universal work of art, the buildings were not merely conceived as shells around the works of art on display, but as accomplished units of house, garden, courtyards, and showcases. Gustav Klimt had discussed the goals of the “Kunstschau Wien” with Berta Zuckerkandl, his supporter of many years, as early as November 1907:

“Our program has not yet fully matured. In any case, we seek to present ‘Gesamtkunst’ in the broadest sense of the word. This means that it should turn out an exhibition of pictures, architecture, sculpture, and decorative arts. If possible, with garden design as a supplement [...]. But then it is above all the young people that should come out. We will see what has developed here, how much talent and skills have matured.”

The “Kunstschau Wien” was held from 1 June to 16 November 1908. It was the first exhibition of the Klimt Group, a loosely united, informal association of artists that had left the Secession on 14 June 1905. The area of 6500 square meters consisted of some 30 exhibition rooms, several courtyards, a garden theater, a coffeehouse, and a cottage. All spheres of life were to be considered. The exhibits comprised, among other disciplines, children’s art, decorative arts (interior design), religious art, theater and poster art, as well as painting and sculpture.

Emma Bacher, a close acquaintance of Klimt’s and the owner of Galerie Miethke, documented the festive atmosphere at the opening ceremony on 1 June 1908 in several photographs. Gustav Klimt held an opening speech that was printed word by word in the catalog and in almost all newspaper reviews.

Series of Photographs by Emma Bacher, 1908

-

Gustav Klimt during his speech at the opening of the "Kunstschau Wien 1908", 06/01/1908, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

Gustav Klimt during his speech at the opening of the "Kunstschau Wien 1908", 06/01/1908, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library -

Gustav Klimt in conversation at the opening of the "Kunstschau Wien 1908", 06/01/1908, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

Gustav Klimt in conversation at the opening of the "Kunstschau Wien 1908", 06/01/1908, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library -

Gustav Klimt in conversation at the opening of the "Kunstschau Wien 1908", 06/01/1908, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

Gustav Klimt in conversation at the opening of the "Kunstschau Wien 1908", 06/01/1908, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library -

Gustav Klimt at the opening of the "Kunstschau Wien 1908", 06/01/1908, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

Gustav Klimt at the opening of the "Kunstschau Wien 1908", 06/01/1908, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library -

Gustav Klimt at the opening of the "Kunstschau Wien 1908", 06/01/1908, Klimt Foundation

Gustav Klimt at the opening of the "Kunstschau Wien 1908", 06/01/1908, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Emilie Flöge and Gustav Klimt at the opening of the "Kunstschau Wien 1908", 06/01/1908, Klimt Foundation

Emilie Flöge and Gustav Klimt at the opening of the "Kunstschau Wien 1908", 06/01/1908, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Entrance portal of the Vienna Art Show 1908 designed by Josef Hoffmann, in: Der Architekt. Wiener Monatshefte für Bau- und Raumkunst, 14. Jg. (1908).

© Heidelberg University Library

The “Kunstschau Wien 1908” was meant to present high art (painting, sculpture, architecture) and applied art (decorative arts, theater, garden design) in an ideal equilibrium. Its goal was to illustrate that modern art should penetrate all spheres of life, so as to acquaint a large audience with the concept of “art for everyone.” The artists around Klimt thus continued the road they had taken with the artists’ colony on Hohe Warte, the Cabaret Fledermaus, and the Stoclet Palace.

176 artists participated in this major event, one third of them being women. Special rooms were dedicated to such illustrious personalities as Gustav Klimt, Carl Moll, Kolo Moser, and the sculptor Franz Metzner. Besides painting, the focus was also on the presentation of decorative arts, especially with works from the Wiener Werkstätte, which had also been assigned a room of its own (50). In addition to art objects, modern dance performances and theater plays were staged at the garden theater, with the participation of leading practitioners of dance and theater, including the Wiesenthal sisters.

The “Kunstschau Wien 1908” was meant to present high art (painting, sculpture, architecture) and applied art (decorative arts, theater, garden design) in an ideal equilibrium. Its goal was to illustrate that modern art should penetrate all spheres of life, so as to acquaint a large audience with the concept of “art for everyone.” The artists around Klimt thus continued the road they had taken with the artists’ colony on Hohe Warte, the Cabaret Fledermaus, and the Stoclet Palace.

176 artists participated in this major event, one third of them being women. Special rooms were dedicated to such illustrious personalities as Gustav Klimt, Carl Moll, Kolo Moser, and the sculptor Franz Metzner. Besides painting, the focus was also on the presentation of decorative arts, especially with works from the Wiener Werkstätte, which had also been assigned a room of its own (50). In addition to art objects, modern dance performances and theater plays were staged at the garden theater, with the participation of leading practitioners of dance and theater, including the Wiesenthal sisters.

Moriz Nähr: Insight into the Vienna Art Show 1908, June 1908 - November 1908, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

The two allegorical masterpieces – the paintings The Three Ages of Woman (1905, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Rome) and The Kiss (Lovers) (1908/09, Belvedere, Vienna), which was still unfinished at the bottom – were juxtaposed on the narrow sides of the room. By flanking The Three Ages of Woman with two symmetrical door openings, the painting was made to stand out even more, whereas The Kiss (Lovers) was framed by the two tall portrait formats Portrait of a Lady in Red and Black (1907/08, private collection) and Friends II (1916/17, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945). Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907, Neue Galerie, New York) and Portrait of Fritza Riedler (1906, Belvedere, Vienna) faced each other on the long walls. Along the long walls, the sequence of the works was similarly devised in a rhythmic fashion by alternating themes and scale – with two square landscape pictures framing a vertical or horizontal female portrait, for example.

Insight into the Vienna Art Show 1908, June 1908 - November 1908

© BSB

Works Exhibited at the “Kunstschau Wien 1908”

-

Gustav Klimt: The Three Ages of Woman, 1905, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea

Gustav Klimt: The Three Ages of Woman, 1905, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea

© National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art, Rome -

Gustav Klimt: The Kiss (Lovers), 1908/09, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: The Kiss (Lovers), 1908/09, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna -

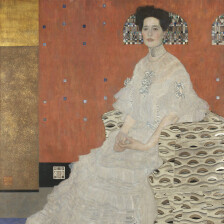

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Fritza Riedler, 1906, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Fritza Riedler, 1906, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, 1907, Neue Galerie New York, Acquired through the generosity of Ronald S. Lauder, the Heirs of the Estates of Ferdinand and Adele Bloch-Bauer, and the Estée Lauder Fund

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, 1907, Neue Galerie New York, Acquired through the generosity of Ronald S. Lauder, the Heirs of the Estates of Ferdinand and Adele Bloch-Bauer, and the Estée Lauder Fund

© APA-PictureDesk -

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein, 1905, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen - Neue Pinakothek München

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein, 1905, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen - Neue Pinakothek München

© bpk | Bavarian State Painting Collections -

Gustav Klimt: Water Snakes I (Parchment), 1904, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: Water Snakes I (Parchment), 1904, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Friends I (The Sisters), 1907, Klimt Foundation

Gustav Klimt: Friends I (The Sisters), 1907, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of a Lady in Red and Black, 1907/08, private collection, in: Kunstverlag Hugo Heller (Hg.): Das Werk von Gustav Klimt, Vienna - Leipzig 1918.

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of a Lady in Red and Black, 1907/08, private collection, in: Kunstverlag Hugo Heller (Hg.): Das Werk von Gustav Klimt, Vienna - Leipzig 1918.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Cottage Garden with Sunflowers, 1906, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: Cottage Garden with Sunflowers, 1906, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Roses beneath Trees, circa 1904, private collection

Gustav Klimt: Roses beneath Trees, circa 1904, private collection

© bpk | RMN - Grand Palais -

Gustav Klimt: Poppies in Bloom, 1907, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: Poppies in Bloom, 1907, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: The Golden Apple Tree, 1903, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

Gustav Klimt: The Golden Apple Tree, 1903, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Danaё, 1907/08, private collection

Gustav Klimt: Danaё, 1907/08, private collection

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Water Snakes II, 1904, private collection

Gustav Klimt: Water Snakes II, 1904, private collection

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: The Sunflower, 1907/08, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, 2012, bequest Peter Parzer, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: The Sunflower, 1907/08, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, 2012, bequest Peter Parzer, Vienna

© Belvedere, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Birch Forest (Beech Forest), 1903, private collection

Gustav Klimt: Birch Forest (Beech Forest), 1903, private collection

© Christie’s Images Limited

The Klimt Room introduced a large number of new paintings to the Viennese audience, as in the previous years the artist had primarily exhibited his works abroad. Half of Klimt’s works in the show were thus presented in Vienna for the first time. While Portrait of Fritza Riedler and Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I had been on view in Mannheim the year before, Klimt had completed The Sunflower (1907/08, Belvedere, Vienna), Poppies in Bloom (1907, Belvedere, Vienna), and Danaë (1907/08, private collection) especially for the “Kunstschau Wien 1908.” The two paintings Water Snakes I (Parchment) (1904, reworked before 1907, Belvedere, Vienna) and Water Snakes II (1904, reworked before 1908, private collection) had been further reworked by Klimt for the “Kunstschau Wien.” In Vienna, the artist was well known for his endless revisions and constant discontent with his works. A reviewer of the Prager Tagblatt wrote:

“In the exhibition […], Klimt presents his harvest of five years of work. And even these pictures had to be removed by his friends from his studio secretly and behind his back, for Klimt himself has never ever ‘finished’ a picture. He knows how to rework it time and again, to add something new or improve it; Klimt considers a work ‘finished’ when it has been stolen by his friends […].”

Sales, Reviews, Résumé

The Secession’s patrons also remained loyal to Klimt after his leaving the association: as early as the first week, the reworked version of Water Snakes I (Parchment) was sold to Karl Wittgenstein, Poppies in Bloom was purchased by Viktor Zuckerkandl for 5000 crowns (approx. 31,150 euros), and Danaë was purchased by Eduard Ast for 8000 crowns (approx. 49,800 euros). The latter had a special oval room designed for this painting in his villa designed by Hoffmann on Hohe Warte. The Imperial-Royal Ministry for Culture and Education acquired The Kiss (Lovers) for 25,000 crowns (approx. 155,700 euros). Klimt was thus certainly one of the financially most successful artists in the show.

“The Kunstschau will be the clou of this year’s summer. [...] That we are looking for new ways may well be true, and the courageous ones that are going to show them to us will defeat us, despite all resistance. Such courage seems to emanate from the Klimt community, so that the Kunstschau will turn out the biggest success.”