Klimt's work focuses on all aspects of the Art Nouveau master's oeuvre. Visualized through a timeline, Klimt's creative periods are rolled up here, starting with his training, his collaboration with Franz Matsch and his brother Ernst in the "Künstler-Compagnie", the affair surrounding the faculty paintings and his post-fame and the myth that still surrounds this exceptional artist today.

Symbolism in Klimt’s Oeuvre

These years mark a caesura in Klimt’s oeuvre. He and Franz Matsch had received the commission to jointly execute the Faculty Paintings, which were to keep them busy over the following eleven years. Noticeably distancing himself from the academic and historically informed approach to painting, Klimt increasingly embraced Symbolism. In 1897 the break with artistic tradition culminated in the foundation of the Secession.

→

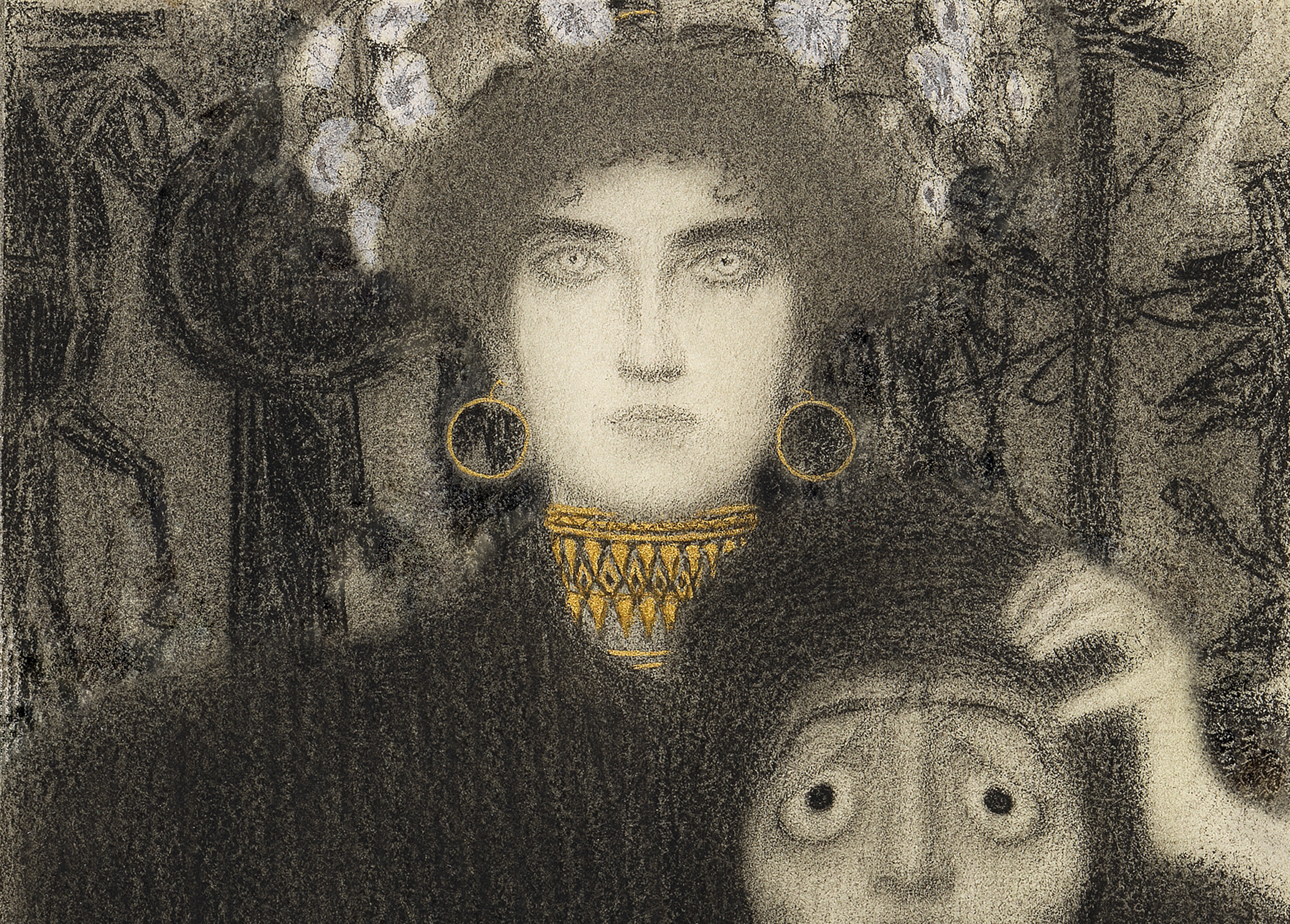

Gustav Klimt: Allegories. New series (tragedy), 1896

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

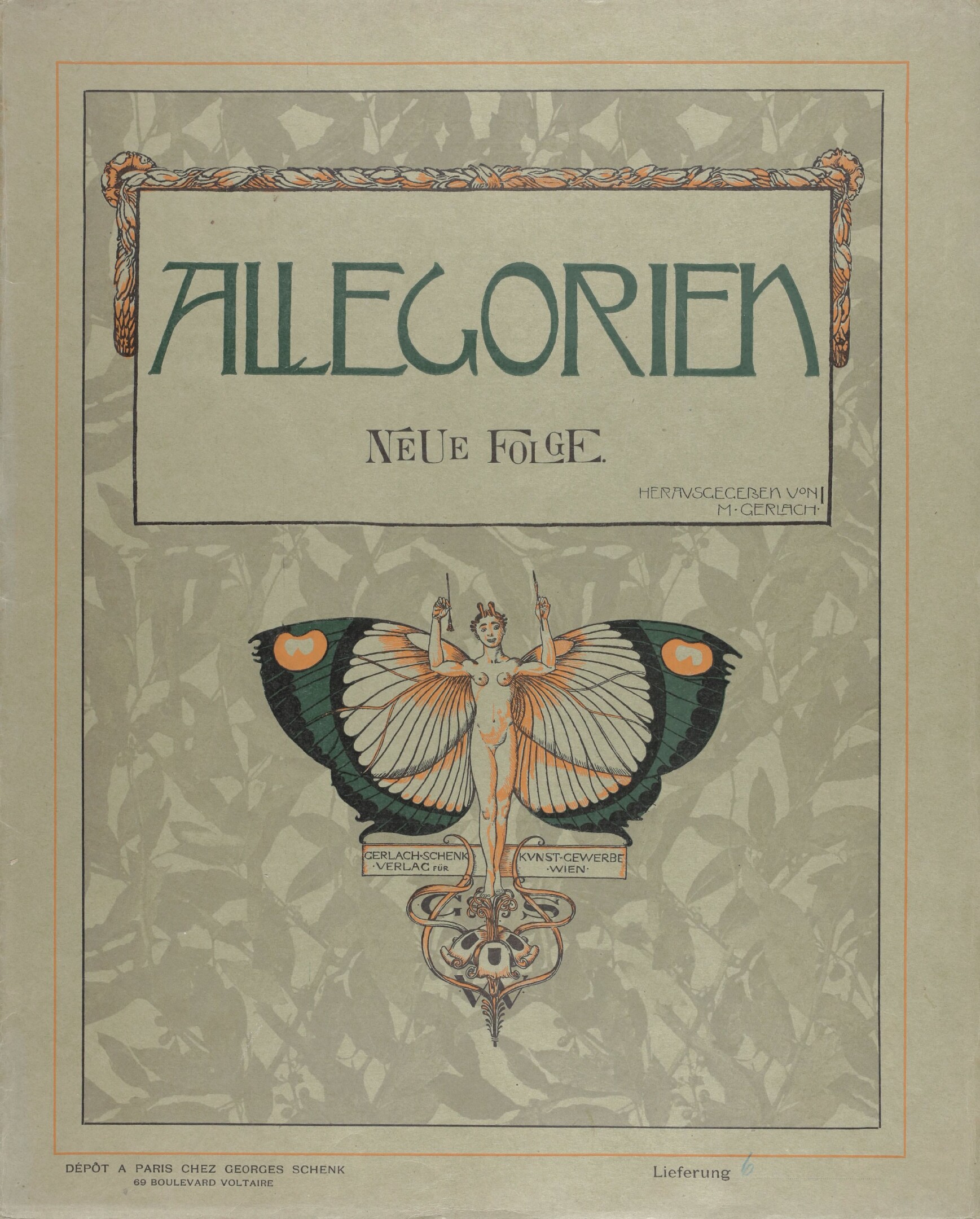

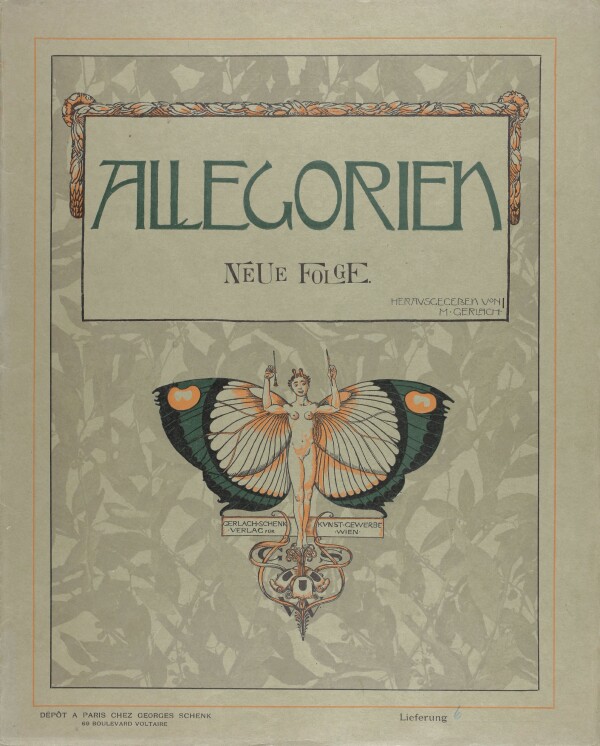

Allegorien. Neue Folge

Gustav Klimt contributed four allegories to the portfolio Allegorien. Neue Folge [“Allegories. New Series”], which was published by Martin Gerlach in 1895/96: the oil painting Allegory of Love and three drawings for Junius, Sculpture, and Tragedy. In these works, he pursued the idea of a symbolic embeddedness of antiquity in contemporary art.

To the chapter

→

Martin Gerlach (Hg.): Allegorien. Neue Folge, Vienna 1896/1900.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Embrace of Symbolism and Impressionism

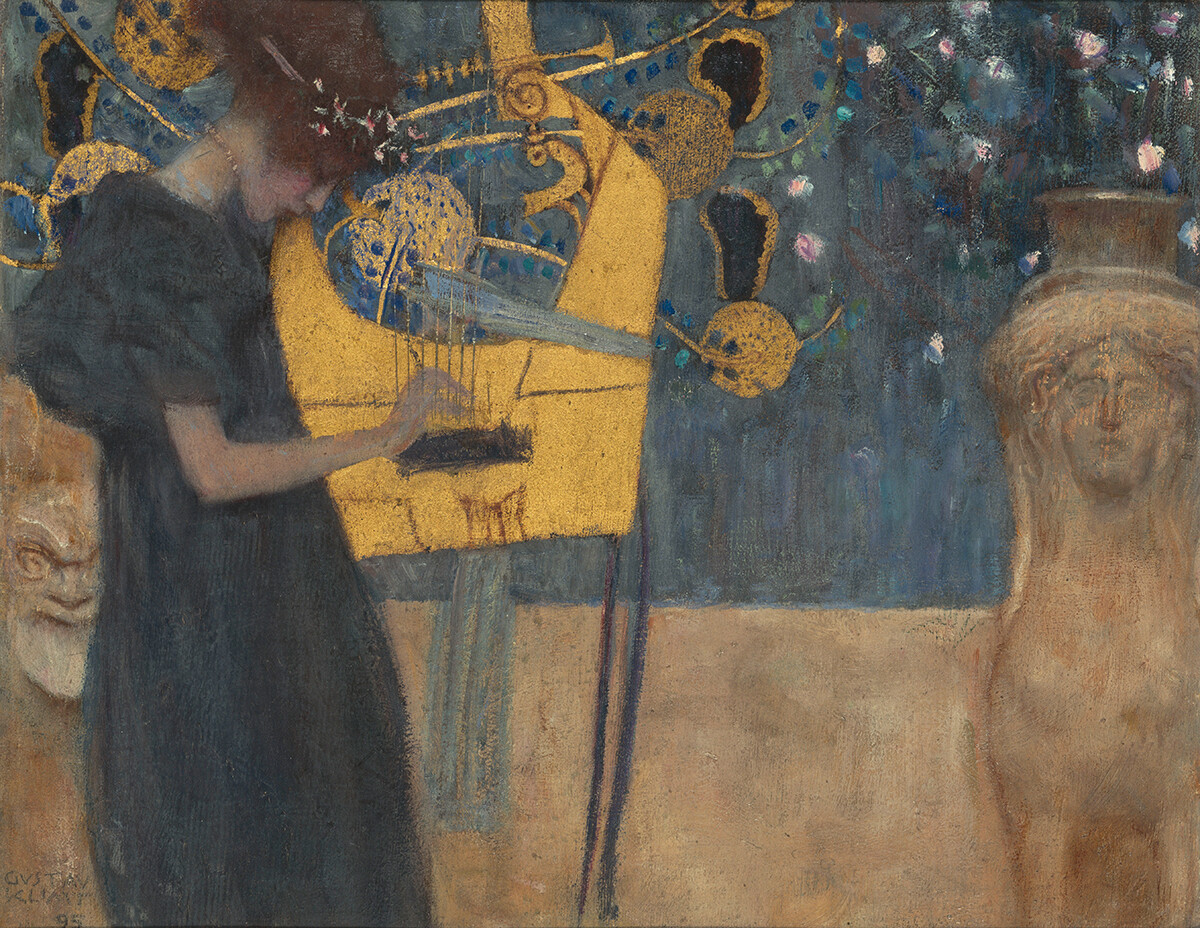

The years immediately preceding the turn of the century were marked by Klimt’s preparatory work for the Faculty Paintings and the conception of two overdoors for Nicolaus Dumba’s music salon. In 1895, Klimt finished the portrait of Josef Lewinsky as Carlos in Clavigo as one of his rare male portraits. He embraced Symbolism and also incorporated Impressionist tendencies into his work.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Music (Study), 1895, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen - Neue Pinakothek München

© bpk | Bavarian State Painting Collections

Faculty Paintings. First Sketches

From 1894, Gustav Klimt executed first studies and sketches for the Faculty Paintings Medicine, Jurisprudence and Philosophy he had been commissioned to create for the large ceremonial hall of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna. The period between 1895 and 1897 was shaped by Klimt’s artistic re-orientation, which manifested in his Symbolist interpretation of the Faculty Paintings.

To the chapter

→

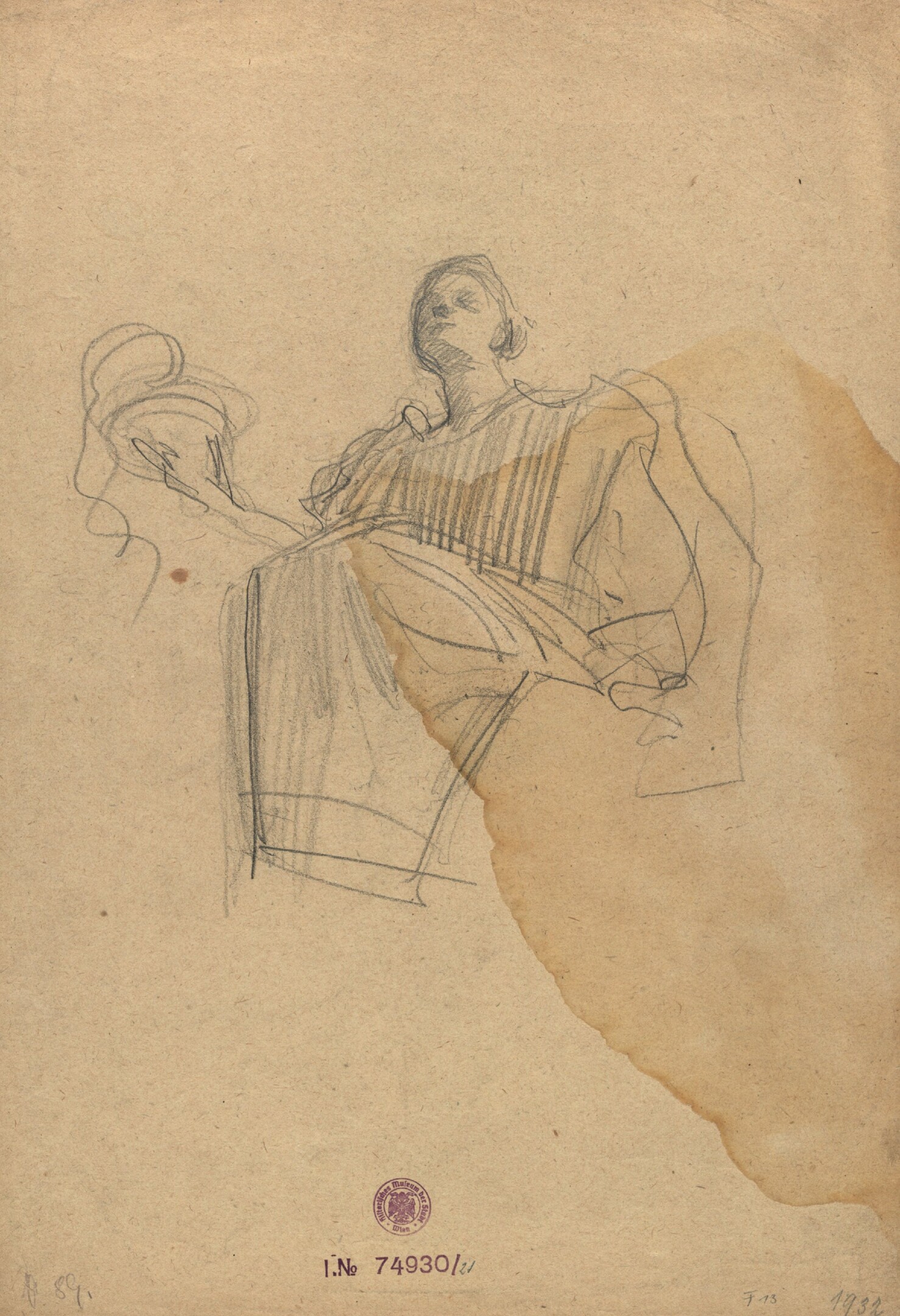

Gustav Klimt: Hygieia, study on the faculty image "Medicine", circa 1894, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Klimt and the Vienna Secession

The Association of Austrian Artists Vienna Secession was founded in 1897 by a group of artists gathering around Gustav Klimt. The Secession is considered the driving force behind Viennese modernism. That same year, the artists, headed by Klimt as their first president, planned the publication of the organization’s official magazine Ver Sacrum and the construction of their own exhibition building.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Design for the building of the Vienna Association, 1898, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Exhibition Activity

Following Klimt’s international debut at the World’s Fair in Antwerp, he exhibited his works primarily at the Vienna Künstlerhaus in the years from 1895 to 1897. The presentations focused on paintings and graphic works that had been created as designs for printed works.

To the chapter

→

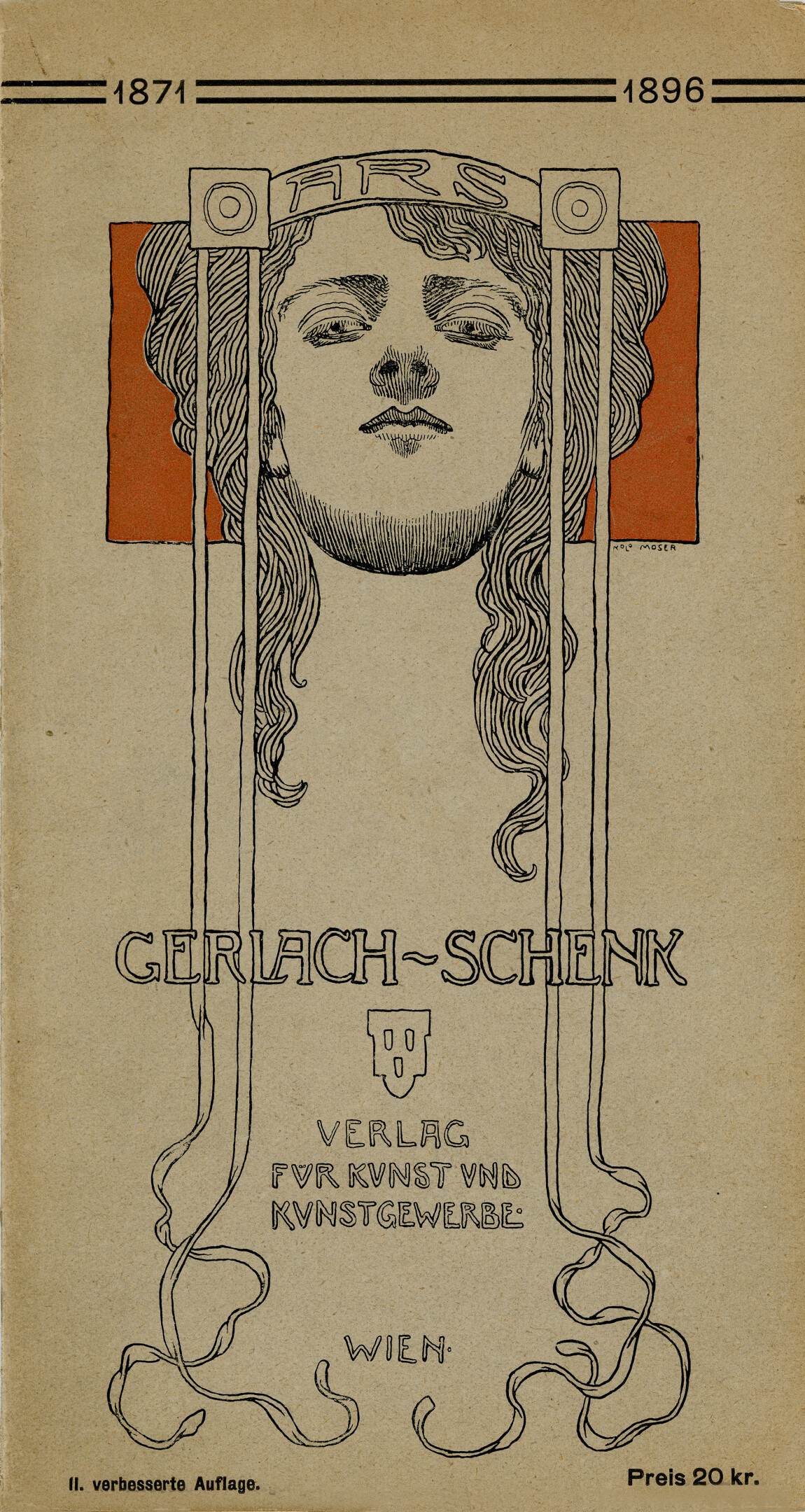

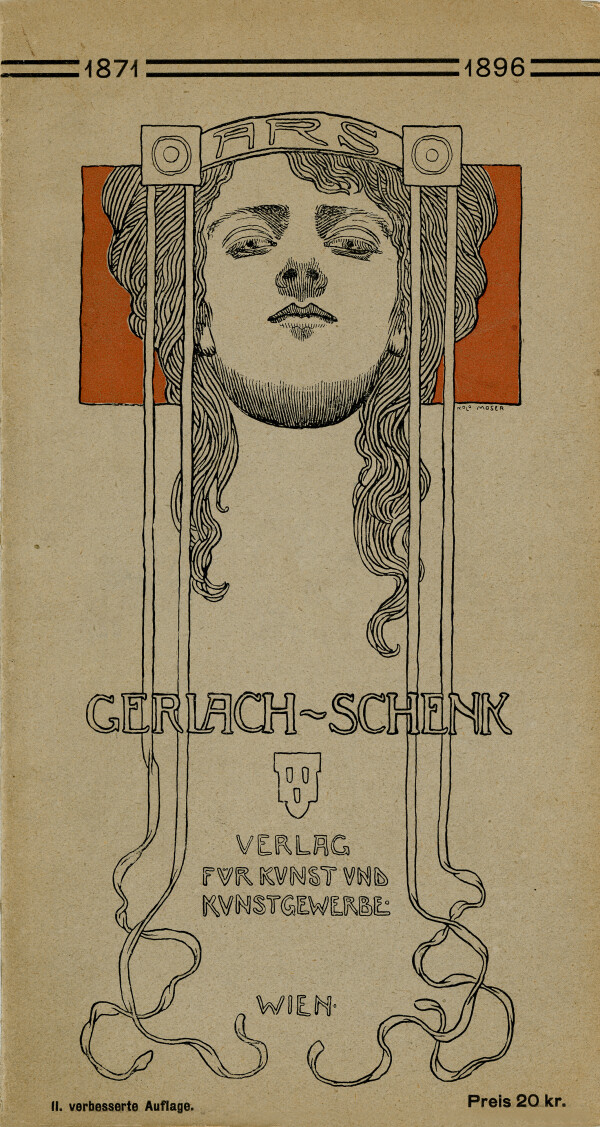

Joseph Meder (Hg.): Originalzeichnungen, Ölgemälde, Aquarelle, Drucke und Vorlagenwerke ausgestellt im Künstlerhause von Gerlach & Schenk, Ausst.-Kat., Artists' House (Vienna), 06.09.1896–01.11.1896, Vienna 1896.

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna

Drawings

The drawings made in the three years between 1895 and 1897 impressively attest to Gustav Klimt’s embrace of Symbolism and the advent of Jugendstil. As a draftsman he tackled his motifs by meticulously studying his models. The artwork designed in 1897/98 for Ver Sacrum illustrates Klimt’s increasing interest in flatness.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Bust portrait of a child, circa 1895, The Albertina Museum

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

Symbolism in Klimt’s Oeuvre

These years mark a caesura in Klimt’s oeuvre. He and Franz Matsch had received the commission to jointly execute the Faculty Paintings, which were to keep them busy over the following eleven years. Noticeably distancing himself from the academic and historically informed approach to painting, Klimt increasingly embraced Symbolism. In 1897 the break with artistic tradition culminated in the foundation of the Secession.

→

Gustav Klimt: Allegories. New series (tragedy), 1896

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Allegorien. Neue Folge

Martin Gerlach (Hg.): Allegorien. Neue Folge, Vienna 1896/1900.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

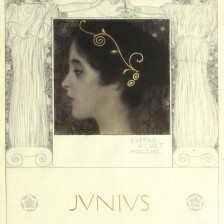

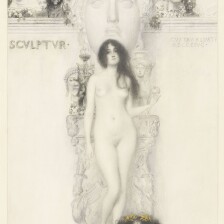

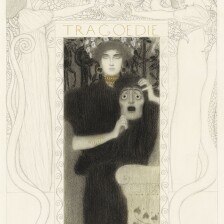

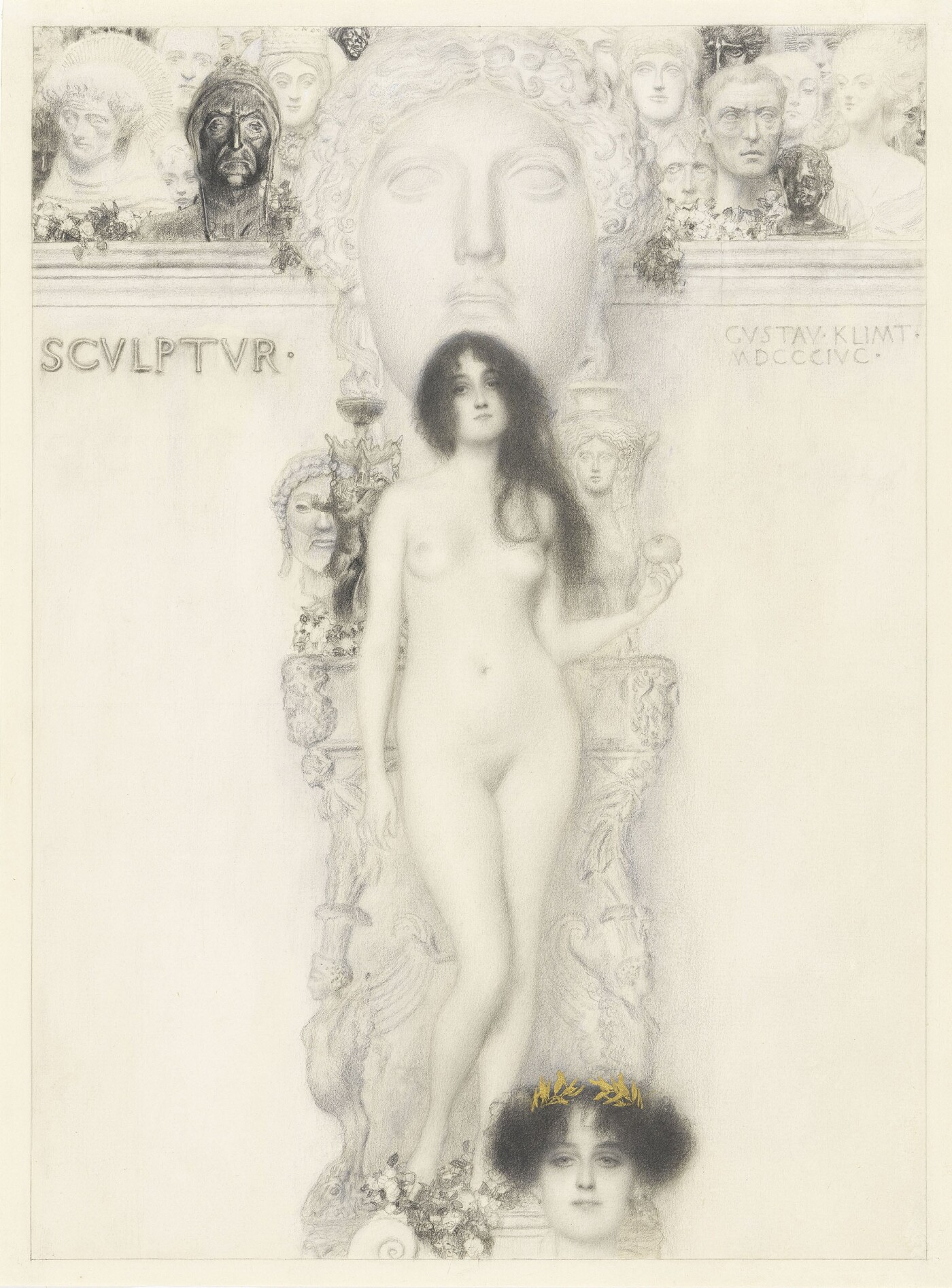

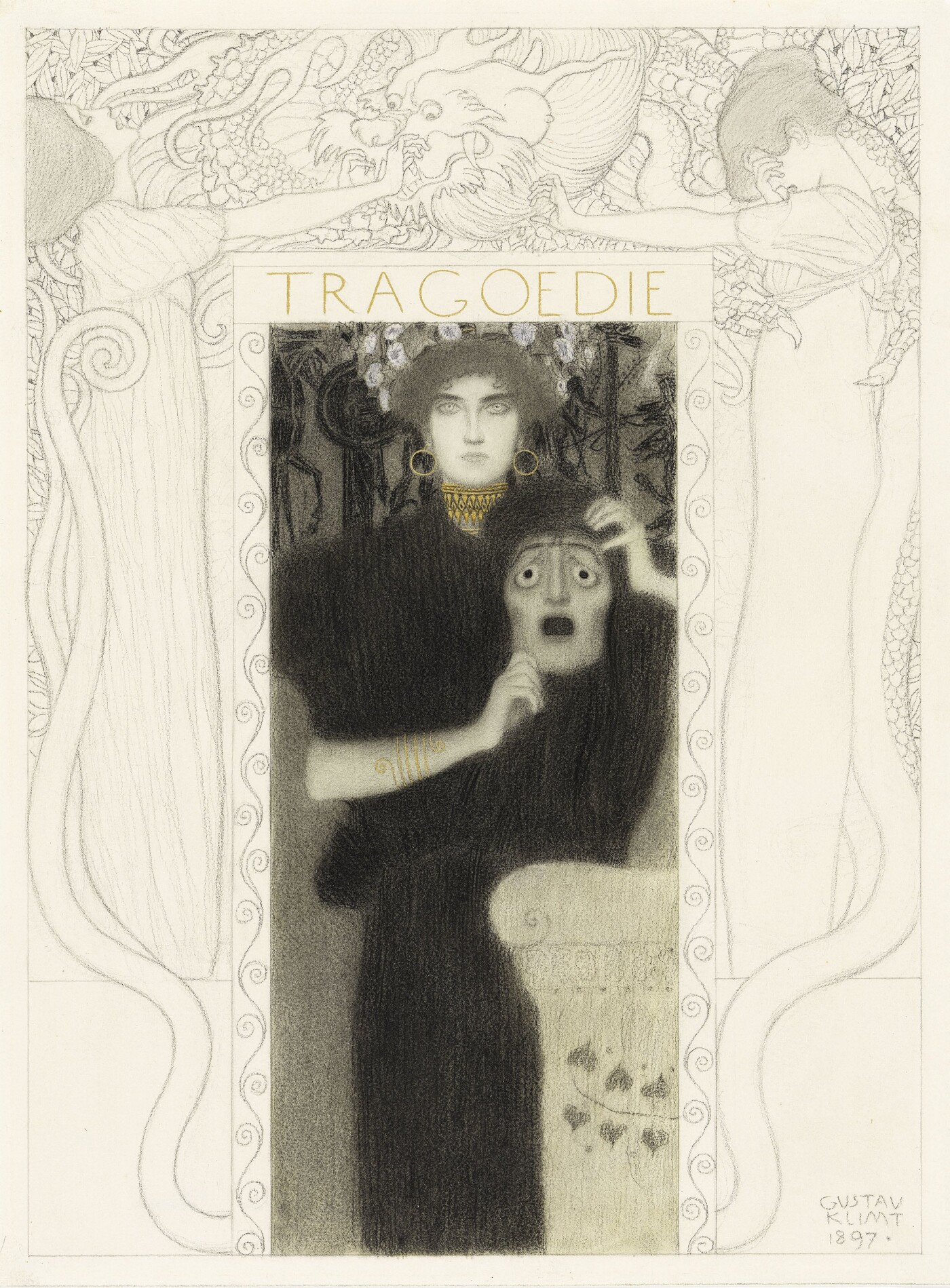

Gustav Klimt contributed four allegories to the portfolio Allegorien. Neue Folge [“Allegories. New Series”], which was published by Martin Gerlach in 1895/96: the oil painting Allegory of Love and three drawings for Junius, Sculpture, and Tragedy. In these works, he pursued the idea of a symbolic embeddedness of antiquity in contemporary art.

The series Allegorien. Neue Folge [“Allegories. New Series”] (1895/96), which was published by Gerlach & Schenk from 1895 on, appeared in continuation of an earlier and commercially successful portfolio called Allegorien und Embleme [“Allegories and Emblems”] (1882). Such preeminent contemporary artists as Franz von Stuck, Gustav Klimt, and Koloman Moser were involved in the publication of the second series. Their modern reinterpretations of symbolic concepts were meant to take contemporary art production and artisanry to the level of international modernism and disseminate them among artists, craftspeople, and traders in the form of a compilation of samples. The publication of this portfolio was advertised in numerous newspapers. Comprising 120 illustrations in 20 installments and sold for the substantial price of 150 guilders (2,280 euros), it was one of the most comprehensive sample compilations of its time.

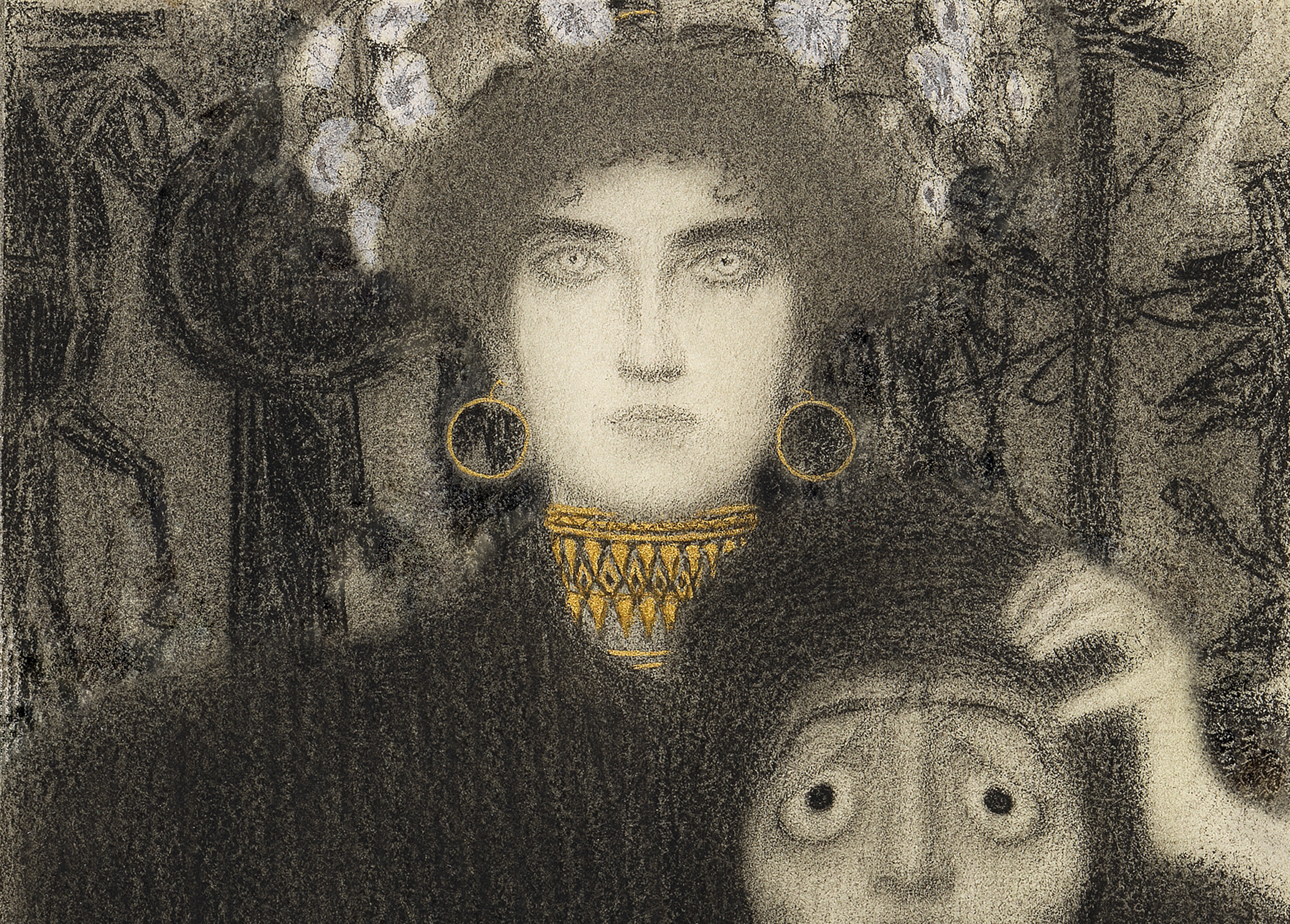

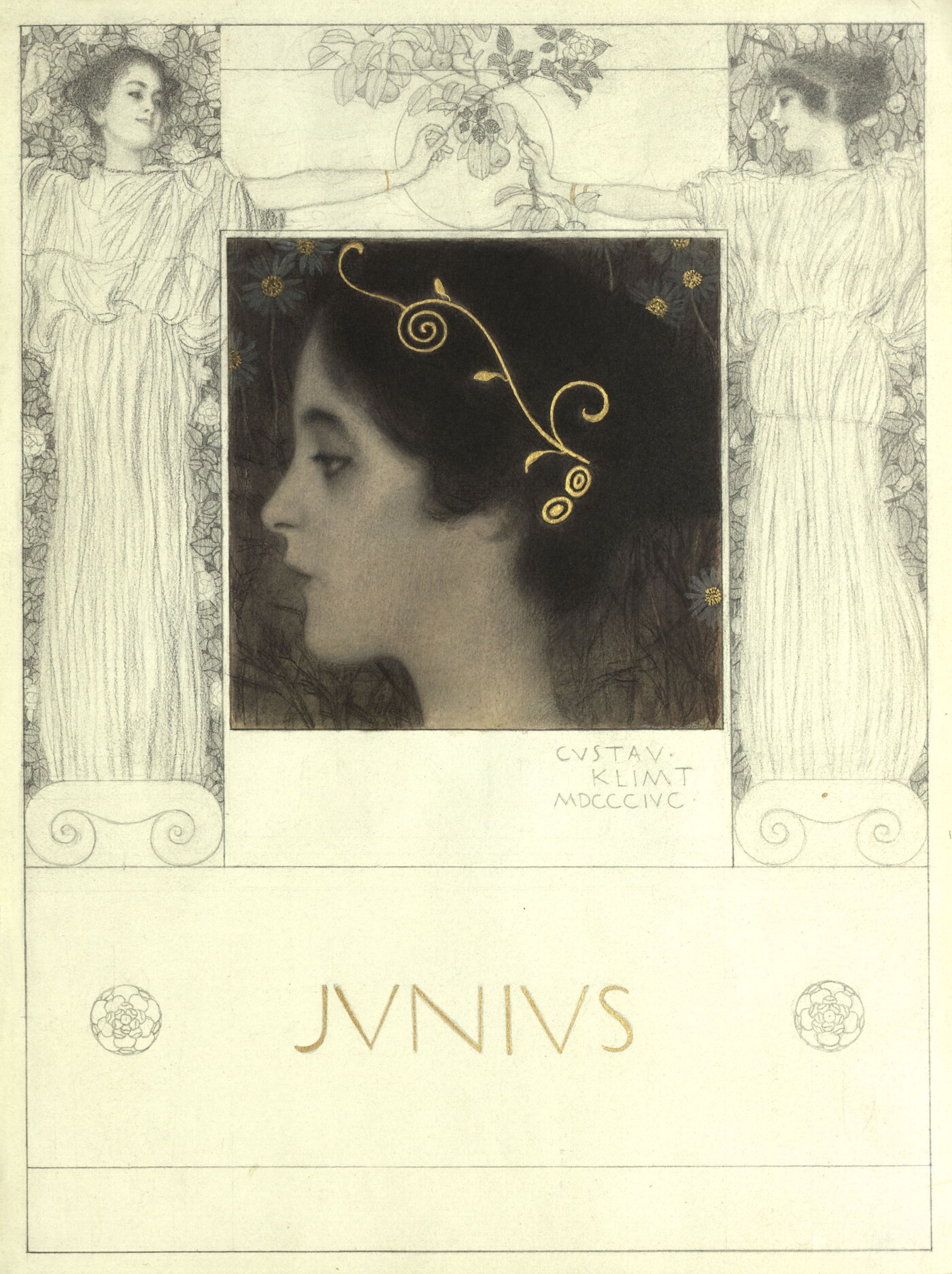

For this sample compilation, Klimt made the drawings Junius (model for: Allegorien N.F. No. 53) (1896, Wien Museum, Vienna), an allegory of the month of June, as well as allegories of Sculpture (model for: Allegorien N.F. No. 58) (1896, Wien Museum, Vienna) and Tragedy (model for: Allegorien N.F. No. 66) (1897, Wien Museum, Vienna), plus the oil painting Allegory of Love (model for: Allegorien N.F. No. 46) (1895, Wien Museum, Vienna). These four works hold a crucial position in Viennese Modernism. The three drawings and the oil painting show Klimt’s stylistic reorientation, pointing to his increasing exploration of Symbolism and thus his preoccupation with the painters Fernand Khnopff and Jan Toorop.

Gustav Klimt: Allegory of Love, 1895, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

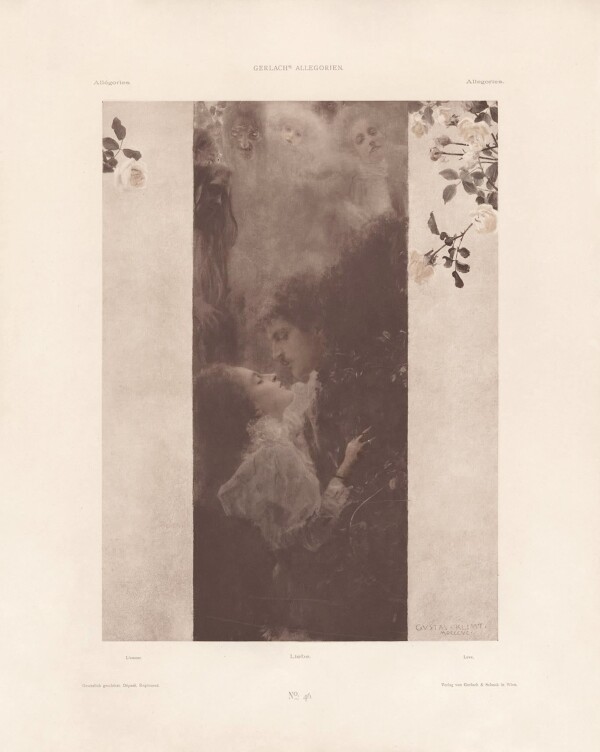

Love, in: Martin Gerlach (Hg.): Allegorien. Neue Folge, Vienna 1896/1900.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Allegory of Love

Klimt’s new stylistic development is most clearly visible in the oil painting on which Allegory of Love is based. The painting follows a strict structure of compartments, as they would later also show in the drawings. The principal compartment is framed by two narrow golden marginal fields adorned with roses, the symbol of love. The narrow vertical field thus created encloses an amorous couple about to kiss, emerging from the vague and hazy background like some dreamlike apparition. In the upper zone of the picture, Klimt presents several heads representing different ages. They seem to have been conceived as allegorical components, although their precise iconographic message remains unclear. These heads anticipate the entangled groups of hovering figures in the Faculty Paintings. Both compositionally and stylistically, Allegory of Love is thus a pendant to Portrait of Josef Lewinsky as Carlos in Clavigo (1895, Belvedere, Vienna), which dates from the same year and likewise served as model for a print.

The Drawings

The drawing Junius stands out for its rigid order of geometric fields. It is for the first time that Klimt divided the picture plane in such a way that the result was a square central field. In Junius one can already sense art’s increasingly harking back to antiquity, which for Klimt would become more and more relevant in the context of the foundation of the Vienna Secession. For example, he referred to the ancient classification according to gender and ornament established by Vitruvius. The latter had assigned the Ionic column with its scrolls to femininity by comparing it to “gracilitas,” the slenderness of the female body. Klimt consequently positioned two women dressed in the style of antiquity on Ionic capitals.

The final artwork for Sculpture (late 1896) exhibits similar tendencies. Once again, the picture plane is divided into geometric compartments. In front of a wall that is placed parallel to the picture plane and thus encloses the composition, and which bears an inscription, Klimt has positioned a female nude holding an apple in one hand. Behind her and above the cornice, he has collaged busts from antiquity to Rococo to create a frieze. They present a survey of sculpture’s greatest accomplishments. Klimt has additionally expanded the continuity of the pictorial space beyond the margins by adding a realistic female head crowned with a wreath at the lower margin, thus anticipating the motif of the Faculty Painting of Philosophy (1900–1907, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945).

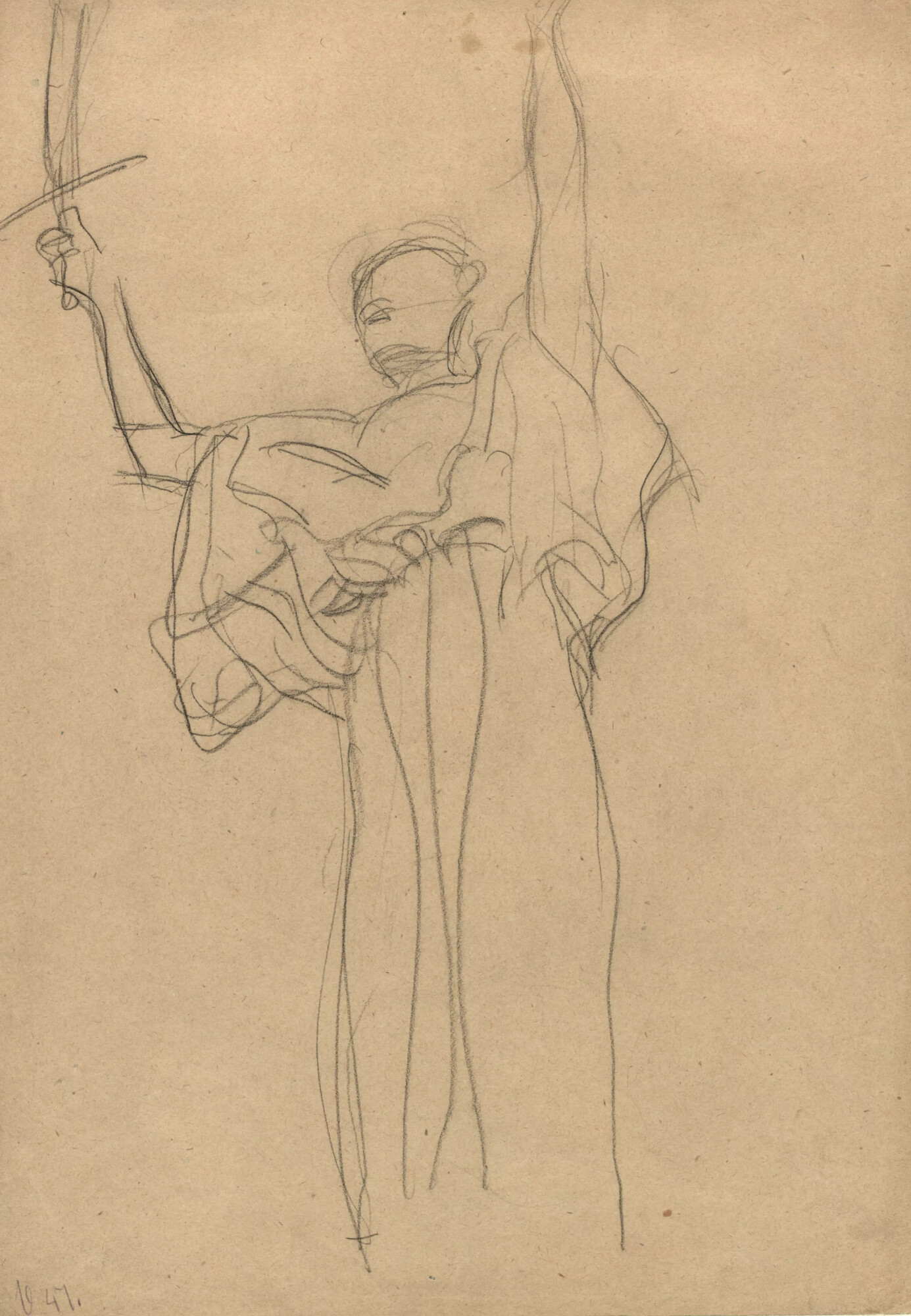

In the final design for Tragedy, the last sheet of the series, Klimt’s radicality in his adaptation of the new pictorial idiom of Symbolism manifests itself most distinctly. Shown frontally within a strict composition of flat fields, the figure reminiscent of the art of Fernand Khnopff appears against the foil-like backdrop of a figural frieze inspired by antique vase painting, while Jan Toorop’s influence is revealed by the figure’s gestures and elongated limbs.

Final Artworks

-

Gustav Klimt: June, 1896, Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: June, 1896, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum -

Gustav Klimt: Sculpture, 1896, Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Sculpture, 1896, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum -

Gustav Klimt: Tragedy, 1897, Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Tragedy, 1897, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

From Allegorien. Neue Folge to Ver Sacrum

By contributing to the portfolio Allegorien. Neue Folge, Gustav Klimt had secured for himself a highly attractive platform for disseminating his newly developed approach to art. The exhibition of the original designs for the portfolio at the Vienna Künstlerhaus in 1896 proved an additional stage for Gustav Klimt to present himself. Besides the works for the first part of the portfolio, Allegorien und Embleme [“Allegories and Emblems”], the show also comprised drawings and paintings for the new series. Especially Klimt’s painting Allegory of Love arrested the reviewers’ attention. However, their judgment was neither enthusiastic nor particularly negative. The reviews were rather characterized by a hesitant uncertainty, as their authors did not know how to deal with modern art.

“G. Klimt’s mystic picture ‘Die Liebe’ [‘Love’] (4) will not only meet with lots of applause, but probably also with some opposition. It is peculiar, yet good.”

The collaboration between Klimt and Martin Gerlach would also continue after the edition of Allegorien. Neue Folge. Following the foundation of the Vienna Secession in 1897, Gerlach & Schenk would be in charge of the publication of the association’s periodical, Ver Sacrum.

Literature and sources

- Martin Gerlach (Hg.): Allegorien. Neue Folge, Vienna 1896/1900.

- Rainer Metzger: Gustav Klimt. Das graphische Werk, Vienna 2005.

- Marian Bisanz-Prakken (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Ausst.-Kat., Albertina (Vienna), 14.03.2012–10.06.2012; Getty Center (Los Angeles), 03.07.2012–23.09.2012, Munich 2012.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band I, 1878–1903, Salzburg 1980.

- Ursula Storch (Hg.): Klimt. Die Sammlung des Wien Museums, Ausst.-Kat., Vienna Museum (Vienna), 16.05.2012–07.10.2012, Vienna 2012.

- Oesterreichisch-ungarische Buchhändler-Correspondenz, 37. Jg., Nummer 15 (1896), S. 8.

- Deutsches Volksblatt, 10.09.1896, S. 9.

- Marian Bisanz-Prakken (Hg.): Toorop / Klimt. Toorop in Wenen. lnspiratie voor Klimt, Ausst.-Kat., Gemeentemuseum The Hague (The Hague), 07.10.2006–07.01.2007, The Hague 2006.

Embrace of Symbolism and Impressionism

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Josef Lewinsky as Carlos in Clavigo, 1895, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Lady with Cape and Hat against a Red Background, 1897/98, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Girl in the Foliage, circa 1898, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

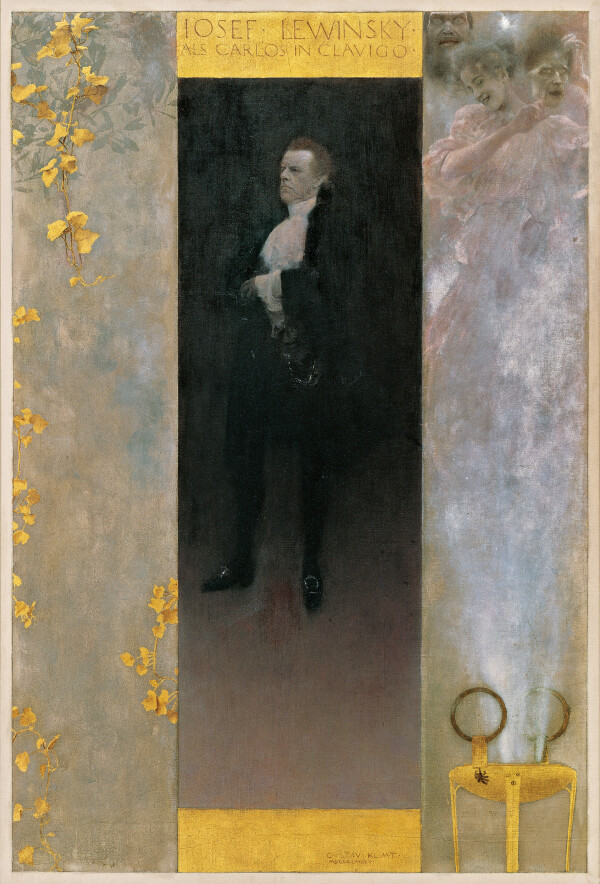

The years immediately preceding the turn of the century were marked by Klimt’s preparatory work for the Faculty Paintings and the conception of two overdoors for Nicolaus Dumba’s music salon. In 1895, Klimt finished the portrait of Josef Lewinsky as Carlos in Clavigo as one of his rare male portraits. He embraced Symbolism and also incorporated Impressionist tendencies into his work.

Gustav Klimt managed to arouse the enthusiasm of industrialist Nicolaus Dumba, whom he won over as an important patron of the arts and collector. For the latter’s music salon in his Vienna city palace at Parkring 4, Klimt conceived two overdoors. Only the preliminary designs for Music (Study) (1895, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen – Neue Pinakothek, Munich) and Schubert at the Piano (Study) (1896/97, private collection) have survived. It is especially in the latter work that Klimt reflected upon the painterly possibilities of Postimpressionism. The actual paintings, which had been installed in the palace in 1899, were destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945.

The stage portrait of Josef Lewinsky was a work commissioned from Gustav Klimt as early as 1894 by the Society of Reproductive Art. The Society planned to publish Oskar Teuber’s historical review Das k. k. Hofburgtheater seit seiner Begründung [The Imperial-Royal Court Theater since Its Foundation] (1896, vol. 2/2). Klimt’s portrait accompanied the photograph of the sitter in the form of a photogravure. Portrait of Josef Lewinsky as Carlos in Clavigo (1895, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna) was based on a photograph and a bronze statuette cast by Karl Dietrich, as the actor sojourned abroad at the time. One is struck by Klimt’s tripartition of the picture plane. He likely painted the framing parts as early as the first half of the year 1894: twigs on a gray ground, with an ancient tripod on the right-hand side. From the incense offering arises the vision of an allegory of the theater: a laughing woman with the mask of tragedy and the head of Dionysus. Whereas in his earlier work Portrait of Joseph Pembaur (1890, Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum, Innsbruck) Klimt had quoted elements from antiquity around the frame without relating them to one another, he now connected the tripod to the incense offering, the vision, and the foliage decoratively spread on the flat surface. It is for the first time that Symbolist and Japanese influences directly manifest themselves in his work.

By 1897, Klimt’s adoption of Impressionist tendencies can also be observed in some of his portraits. Fashionable accessories such as a hat, cape, stole, or fur collar are characteristic of Klimt’s mostly small-sized female portraits painted at the time, such as Lady with a Cape and Hat (1897/98, Klimt-Foundation, Vienna). Klimt painted a hitherto unidentified woman seen from the side, facing the viewer with slightly parted lips. The clothing is entirely black and thus set off against the red tones of the background. The way the color has been applied suggests movement. Like in the following portrait, Klimt used different types of brushstrokes to differentiate between the individual elements of the portrait. While the background and clothes are rendered in a coarser fashion, the face and hair resemble a delicate, almost translucent structure.

In Girl in the Foliage (c. 1898, Klimt-Foundation, Vienna), the artist created a sensitive portrait that likely shows Maria Ucicka, the mother of his first illegitimate son, Gustav Ucicky. The sitter, with her figure slightly twisted, presents herself in a fashionable Girardi sun hat and a high-necked white blouse with puffed sleeves, directing her light-blue eyes at the viewer. Because of the faintly blushed cheeks, her softly and gracefully rendered oval face suggests a certain timidity or insecurity. The delicate painting style already anticipates Klimt’s lyrical and diaphanous portraits of ladies like those of Maria Henneberg, Gertrud Loew, or Hermine Gallia and is in stark contrast to the gestural and Impressionist brushwork of the green foliage surrounding the figure. While the leaves appear denser over her right shoulder and are therefore painted in darker greens, the bright green accents over her left shoulder are reminiscent of the palette of the early Salzkammergut landscapes Klimt painted in St. Agatha.

At that time, Klimt was also influenced by the artistic formulations of George Minne, Jan Toorop, Fernand Khnopff, and Max Liebermann. This development eventually culminated in his first monumental portrayal of square format: Portrait of Sonja Knips (1897/98, Belvedere, Vienna).

Literature and sources

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt 150 Jahre, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 13.07.2012–27.01.2013, Vienna 2012.

- Sandra Tretter: »In meinem Lusthaus im Garten ein herrlichster Tag – betörende Luft – ein schöner Platz – bin wie am Lande«. Gustav Klimts Naturvision im Atelier und auf Sommerfrische, in: Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Florale Welten, Vienna 2019, S. 9-43.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alexander Klee (Hg.): Klimt und die Ringstraße, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna), 05.07.2015–11.10.2015, Vienna 2015.

Faculty Paintings. First Sketches

University of Vienna, around 1900

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

From 1894, Gustav Klimt executed first studies and sketches for the Faculty Paintings Medicine, Jurisprudence and Philosophy he had been commissioned to create for the large ceremonial hall of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna. The period between 1895 and 1897 was shaped by Klimt’s artistic re-orientation, which manifested in his Symbolist interpretation of the Faculty Paintings.

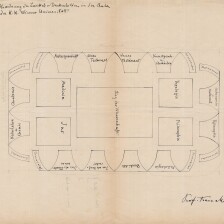

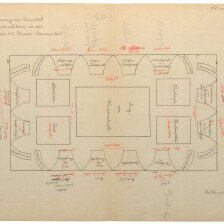

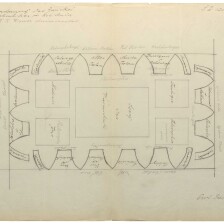

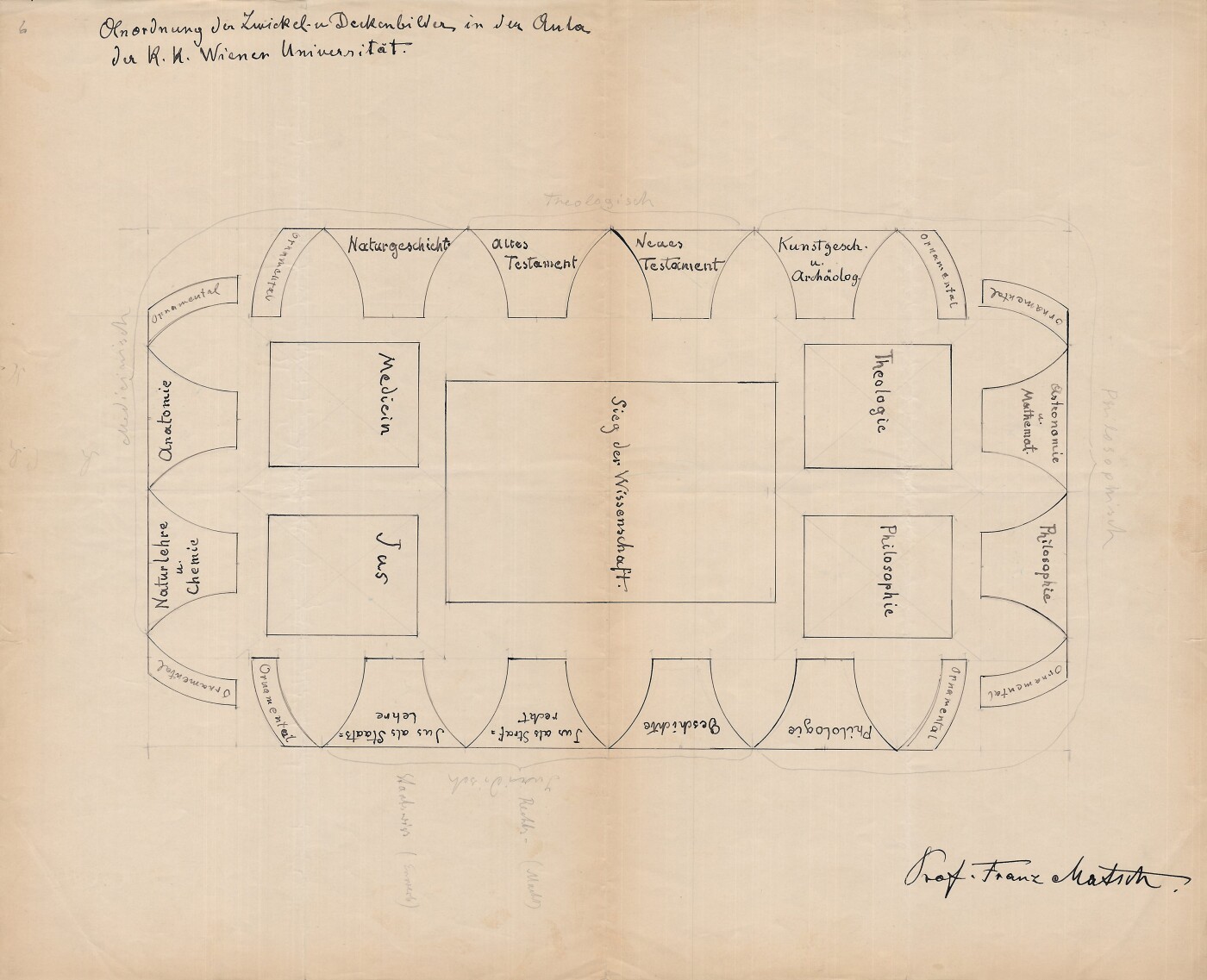

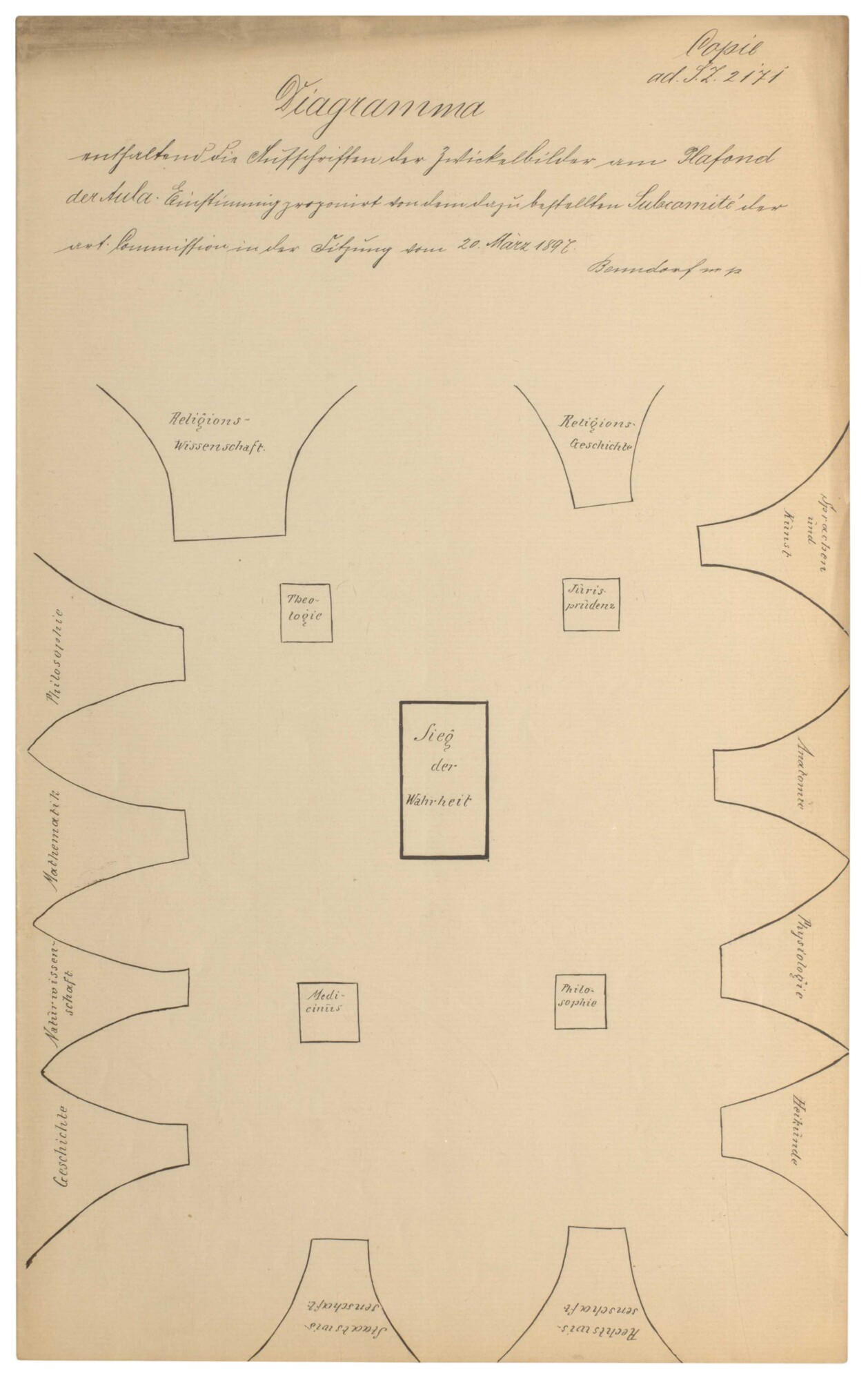

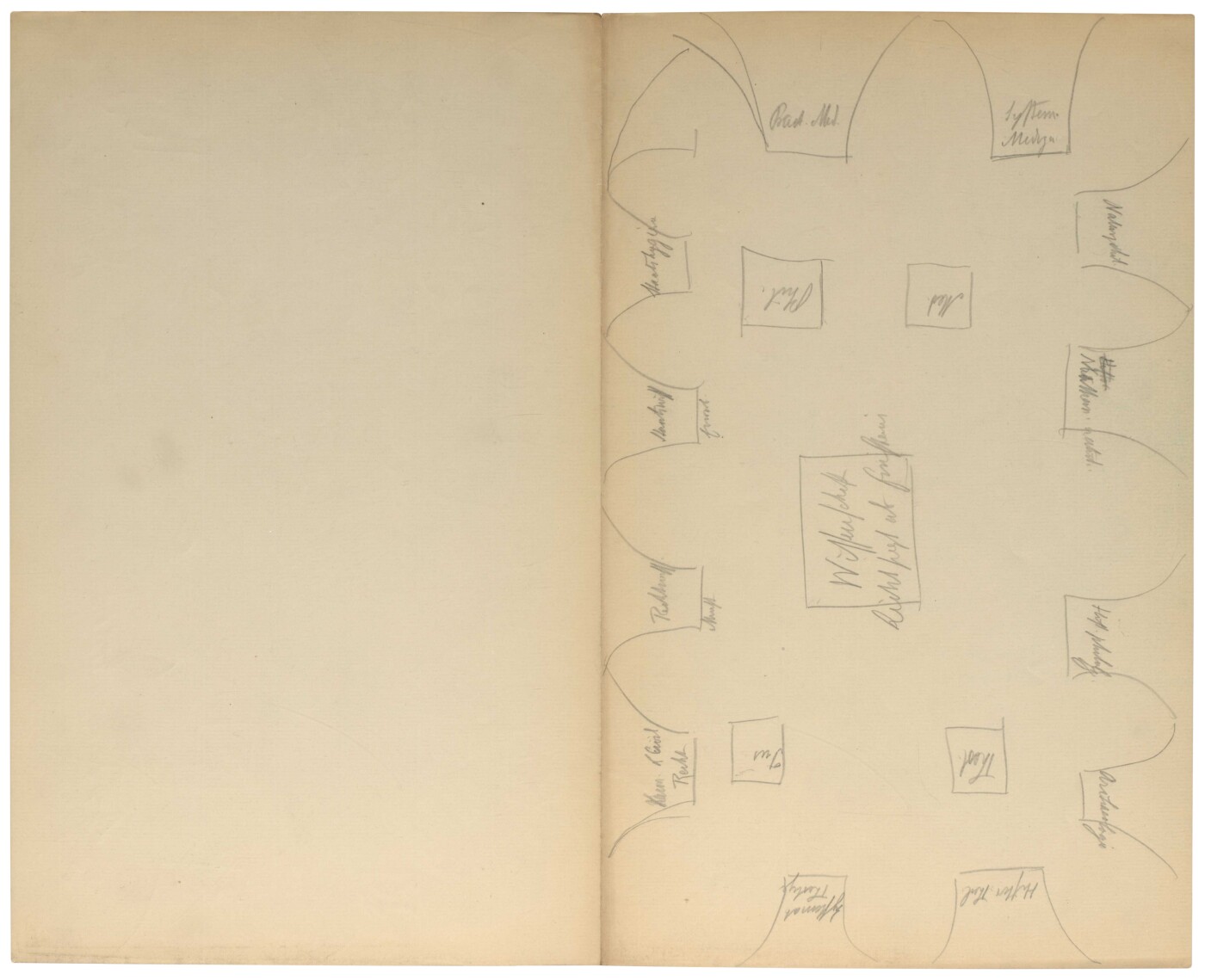

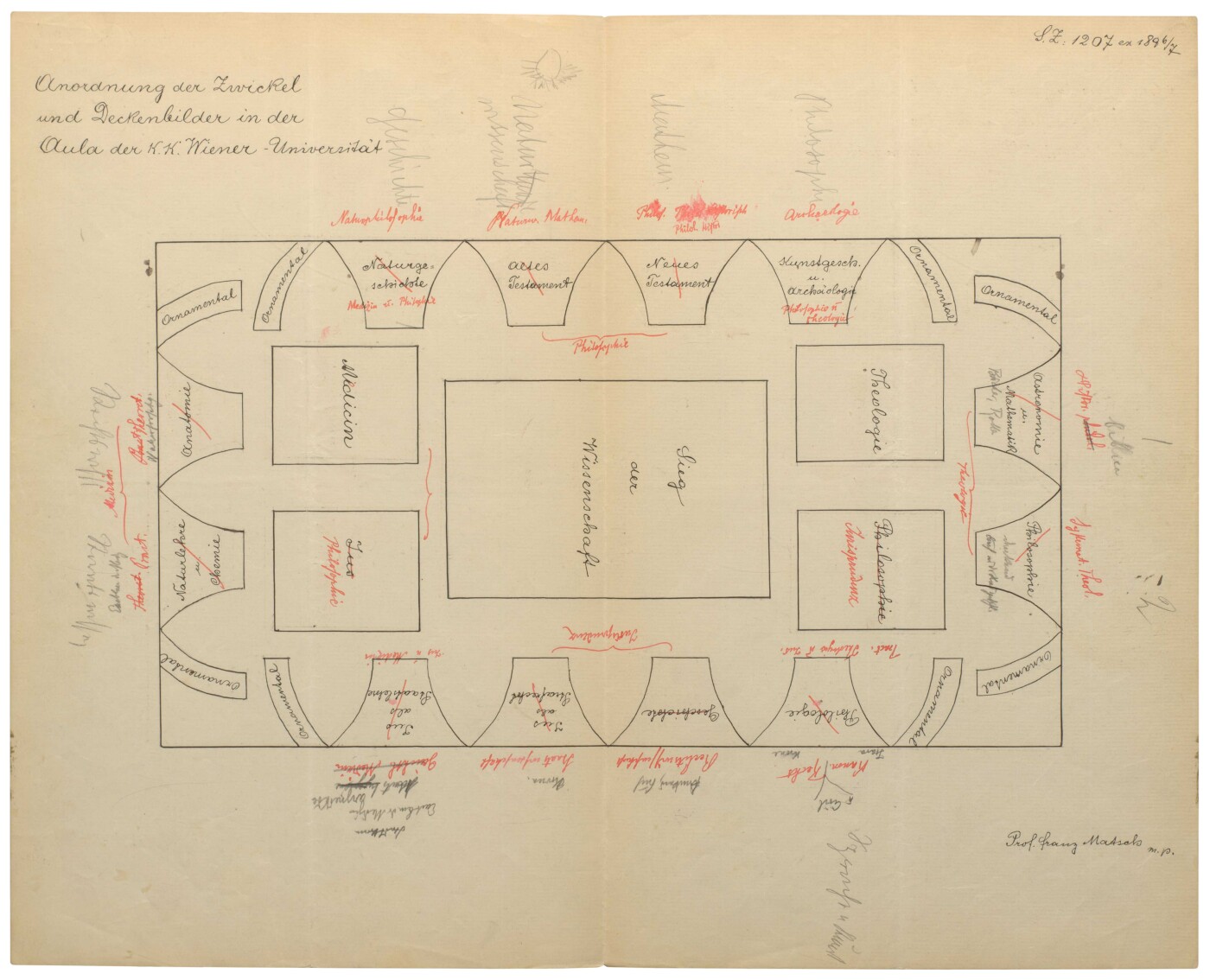

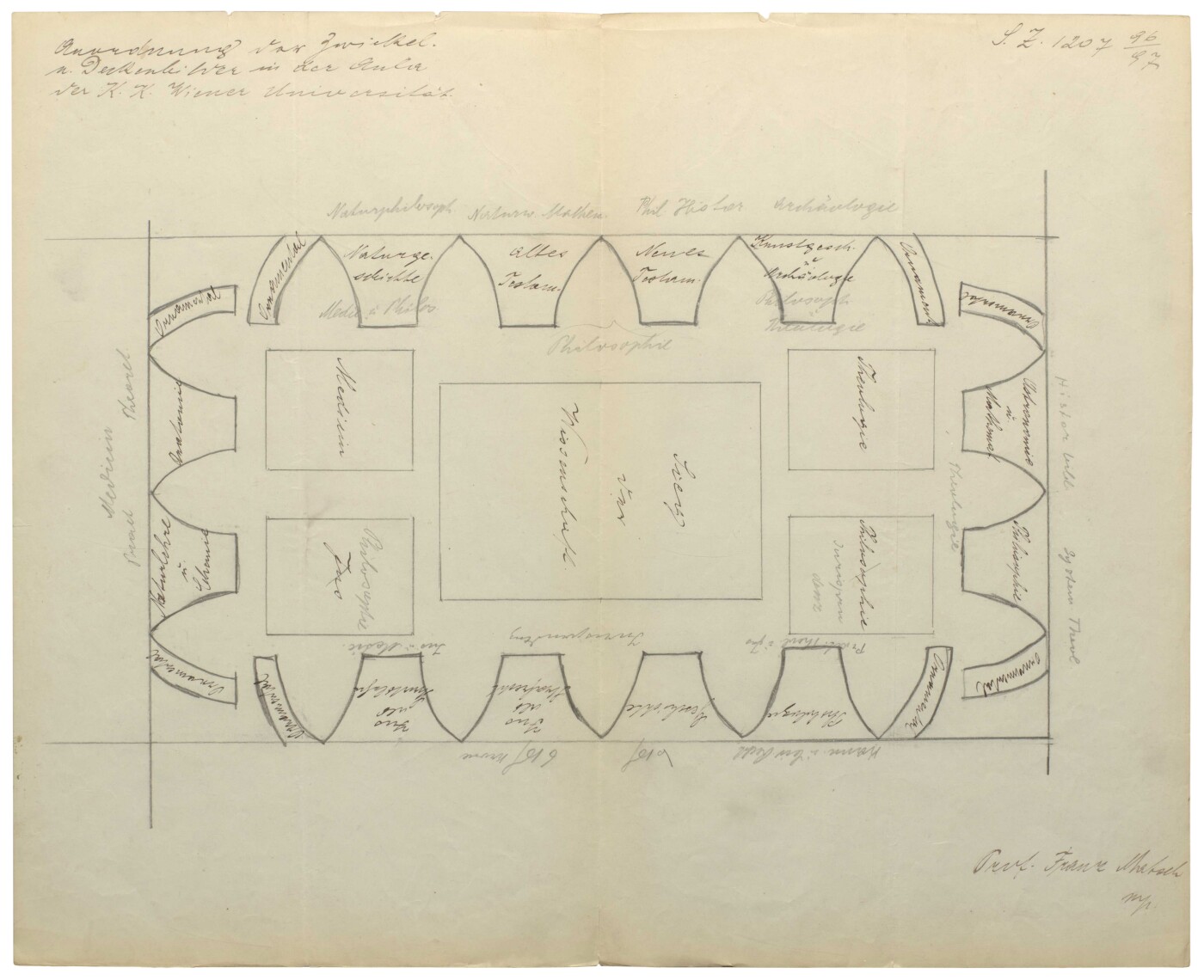

Commission and Programmatic Concept

Even before the artists received their commission in September 1894, Franz Matsch and Gustav Klimt maintained an animated exchange with the Imperial-Royal Ministry of Culture and Education, the artistic committee of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, as well as with the university’s academic senate and rectorate. Between 1896 and 1898, the focus was on the programmatic placement of the ceiling and spandrel paintings. Several drafts, which include the change requests made by the university professors, have survived and are kept at the Austrian State Archives and the Vienna University Archive.

-

Franz Matsch: Sketch showing the arrangement of the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, signed by Franz Matsch, 1896/97-1897/98, Austrian State Archive

Franz Matsch: Sketch showing the arrangement of the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, signed by Franz Matsch, 1896/97-1897/98, Austrian State Archive

© Austrian State Archives, Vienna -

Copy of a Sketch Showing the Arrangement of the Ceiling Paintings for the Great Hall of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna as Desired by the University Professors, 03/20/1897, Archiv der Universität Wien

Copy of a Sketch Showing the Arrangement of the Ceiling Paintings for the Great Hall of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna as Desired by the University Professors, 03/20/1897, Archiv der Universität Wien

© University of Vienna Archive -

Draft of a Sketch Showing the Arrangement of the Ceiling Paintings for the Great Hall of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna as Desired by the University Professors, 1896/97-1897/98, Archiv der Universität Wien

Draft of a Sketch Showing the Arrangement of the Ceiling Paintings for the Great Hall of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna as Desired by the University Professors, 1896/97-1897/98, Archiv der Universität Wien

© University of Vienna Archive -

Copy of a sketch with the arrangement of the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna by Franz Matsch with corrections by the university professors, 1896-1897, Archiv der Universität Wien

Copy of a sketch with the arrangement of the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna by Franz Matsch with corrections by the university professors, 1896-1897, Archiv der Universität Wien

© University of Vienna Archive -

Copy of a sketch with the arrangement of the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna by Franz Matsch with corrections by the university professors, 1896-1897, Archiv der Universität Wien

Copy of a sketch with the arrangement of the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna by Franz Matsch with corrections by the university professors, 1896-1897, Archiv der Universität Wien

© University of Vienna Archive

Gustav Klimt: Hygieia, study on the faculty image "Medicine", circa 1894, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Klimt’s First Sketches

Gustav Klimt began to execute first studies and sketches for the Faculty Paintings in 1894. One of the earliest drawings for Medicine shows Hygieia – the goddess of health and patron saint of pharmacists – sitting on a cloud and holding a bowl with a coiling snake. A chalk drawing, depicting a standing figure holding a sword in her right hand, was likely created around the same time. This study was executed for a painted compositional draft for Jurisprudence (1897/98) which was lost in a fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945.

From the summer of 1896, Klimt likely intensified his work on the drafts for the Faculty Paintings. On 29 August 1896, he explained in a letter to Emilie Flöge, who was staying in Langenwang, that he was as yet unable to join her, as he was busy with work he would not be able to do there, adding:

“[…] seeing as the ministry is withholding an advance until I have completed the sketches, I have been forced to change my program and work very hard, which I am now doing in the extreme. [!] this decision by the ministry has completely thwarted my plans […]”

Klimt referred to an advance of 2000 guilders (c. 29,037 euros), which was eventually granted by the ministry on 28 November 1896, “[…] before the completion and approval of the relevant sketches […].”

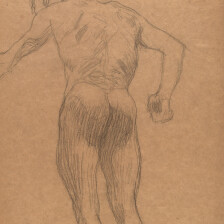

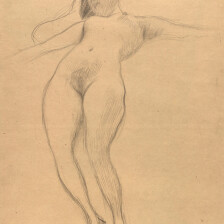

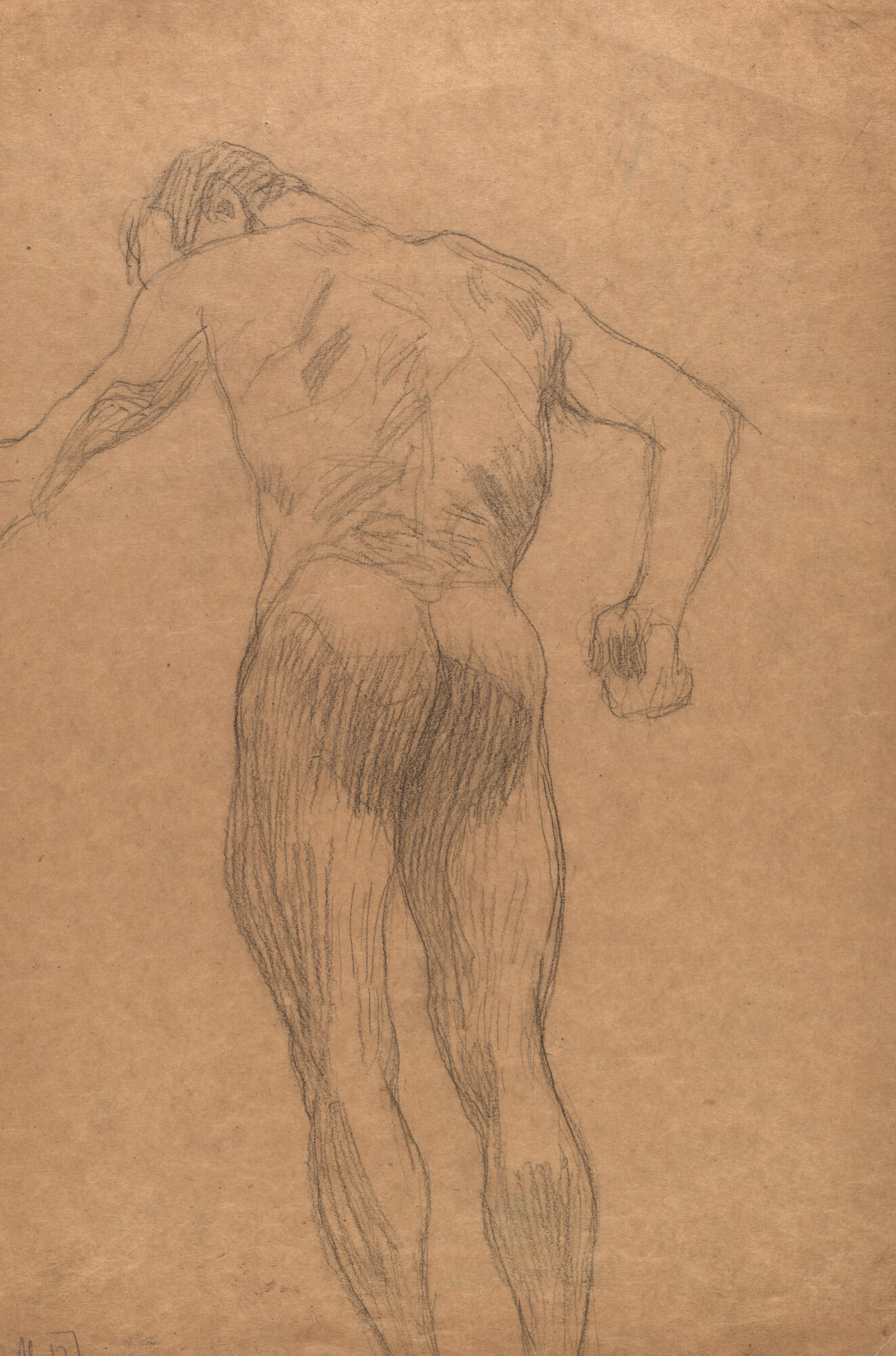

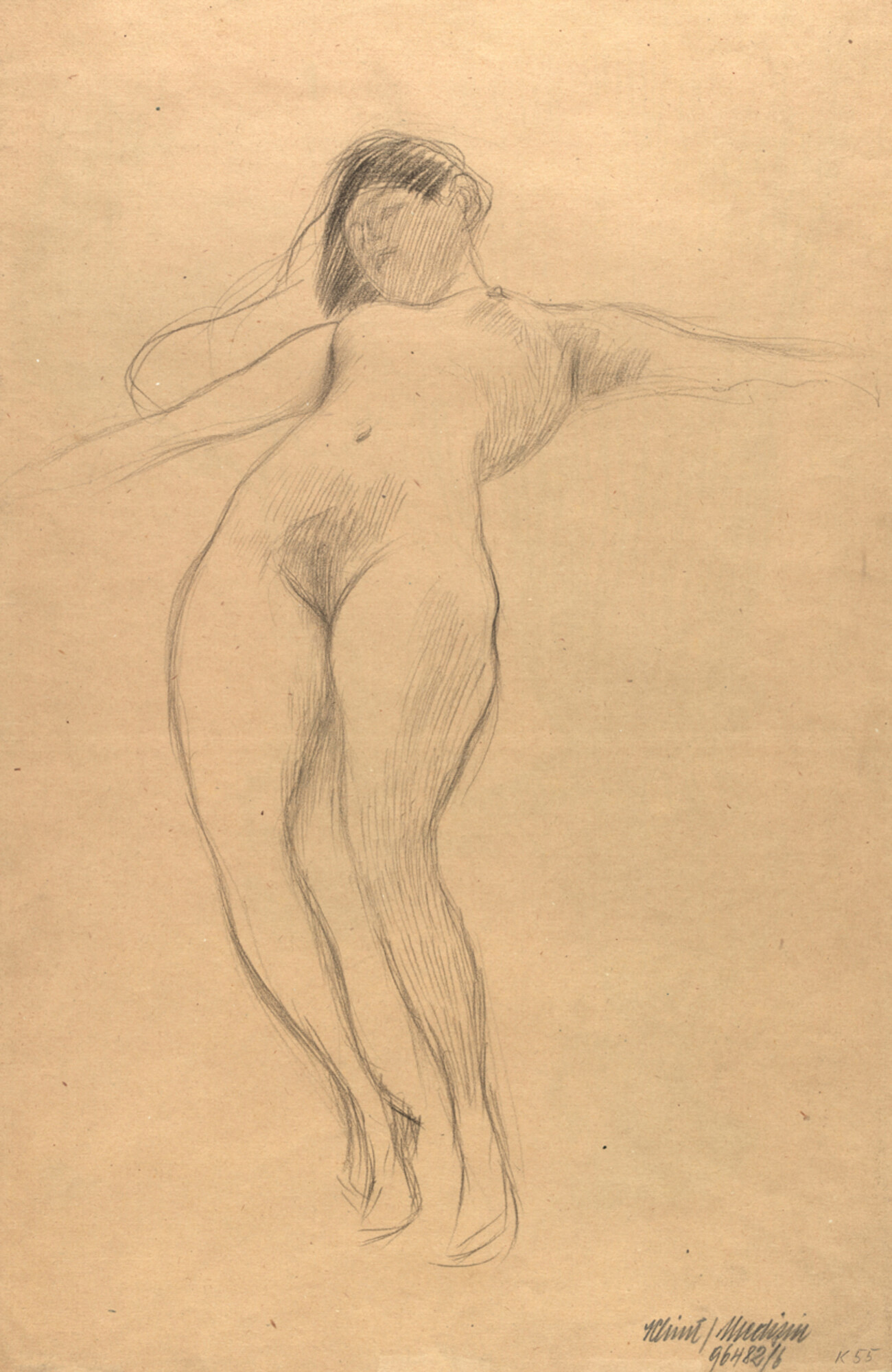

Around 1897/98, Gustav Klimt drew further studies for the Faculty Paintings, now also for Philosophy. The majority of these studies depicted nudes in floating or hunched positions, viewed from below, with softly oscillating outlines and bodies delicately modeled using parallel hatching. This underscored Klimt’s stylistic transition away from Historicism and towards Symbolism. The artist subsequently created numerous drafts as well as compositional studies and transfer sketches for the Faculty Paintings, before embarking on the execution of the paintings in 1898.

-

Gustav Klimt: Standing with sword in raised right hand, circa 1894, Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Standing with sword in raised right hand, circa 1894, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum -

Gustav Klimt: Male nude from below, study for the faculty painting "The Philosophy", 1897/98, Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Male nude from below, study for the faculty painting "The Philosophy", 1897/98, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum -

Female nude, study on the faculty painting "Medicine", 1896, Wien Museum

Female nude, study on the faculty painting "Medicine", 1896, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum -

Gustav Klimt: Standing with raised left arm. Study for the painted compositional design for the painting "Jurisprudence", circa 1897/98, Klimt Foundation

Gustav Klimt: Standing with raised left arm. Study for the painted compositional design for the painting "Jurisprudence", circa 1897/98, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Program Changes

In a meeting held on 22 January 1897, the academic senate discussed the two sketches presented by Matsch for his spandrel paintings, as well as a program regarding “the arrangement of the spandrel areas and ceiling paintings” and the relevant proposals made by the artistic committee. Matsch requested that he be informed of “possible wishes with regards this program and the artistic solutions.” The academic senate asked for the following changes: Instead of dividing Jurisprudence into criminal law and political science, they wanted a division into jurisprudence and political science, with the attributes of power and economic life. Regarding the visualization of Theology via the Old and New Testament through a vision of Ezekiel and the glorification of the cross, the committee voiced concerns about “the depiction’s overly modern direction.” The deanship of the faculty of theology, meanwhile, expressed objections and requests concerning the realization of the spandrel paintings. Rather than portraits of notable scholars, they were to depict symbolic figures holding panels with inscriptions of the disciplines. Matsch and Klimt were informed verbally and in writing about the envisaged alterations which were likely decided latest on 22 May 1897.

Further contents

-

Klimt's Artworks 1889 – 1894 (Decorator of the Ringstraße)Faculty Paintings. Awarding of the Commission

-

Klimt's Artworks 1898 – 1900 (Cradle of Modernism)Faculty Paintings. Philosophy

-

Klimt's Artworks 1901 – 1903 (The Golden Knight and Femmes Fatales)Faculty Paintings. Medicine and Jurisprudence

-

Klimt's Artworks 1904 – 1906 (The Klimt Affair Surrounding the Faculty Paintings)Faculty Paintings. The Klimt Affair

Literature and sources

- Alice Strobl: Zu den Fakultätsbildern. Anlässlich der Neuerwerbung einer Einzelstudie zur „Philosophie“ durch die Graphische Sammlung Albertina, in: Albertina Studien, 2. Jg., Heft 4 (1964), S. 138-169.

- R. Bk.: Vermischtes, in: Kunstchronik. Wochenschrift für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, N.F., 6. Jg., Heft 8 (1894/95), Spalte 125.

- N. N.: Staatliche Kunstpflege in Österreich im Zeitraume von 1891–1895, in: Kunstchronik. Wochenschrift für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, N.F., 6. Jg., Heft 17 (1894/95), Spalte 257-265.

- Brief mit Kuvert von Gustav Klimt in Wien an Emilie Flöge in Langenwang (08/29/1896). Lg1543.

- Brief von Leo Reinisch an das k. k. Ministerium für Cultus und Unterricht (01/26/1897). AT-OeStA/AVA Unterricht UM allg. Akten 739, Zl. 2.698 und 5.191/1897 fol. 6 und 11, .

- Brief vom k. k. Ministerium für Cultus und Unterricht an das Rektorat der k. k. Universität Wien, unterschrieben von Paul Gautsch von Frankenthurn (11/28/1896). S102.1207.2, .

- Brief vom k. k. Ministerium für Cultus und Unterricht an das Rektorat der k. k. Universität Wien (03/15/1897). S102.2171.2, .

- Umschlag Senatsakt 12 über die Gemälde für die Zwickelfelder im Festsaal der k. k. Universität Wien (15.03.1897). S102.2171.1, .

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band I, 1878–1903, Salzburg 1980, S. 147-157, S. 165-199, S. 253-271.

- Alice Strobl: Die Fakultätsbilder »Medizin« und »Philosophie«, in: Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007, S. 41-53.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt 150 Jahre, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 13.07.2012–27.01.2013, Vienna 2012, S. 84-121.

- Universität Wien. 650 plus-Geschichte an der Universität Wien. geschichte.univie.ac.at/de/artikel/die-fakultaetsbilder-von-gustav-klimt-im-festsaal-der-universitaet-wien (04/24/2020).

- Alice Strobl: Kompositionsentwürfe zur "Philosophie" aus dem Skizzenbuch von Sonja Knips sowie Einzelstudien zum selben Fakultätsbild, in: Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band IV, 1878–1918, Salzburg 1989, S. 73-82.

Klimt and the Vienna Secession

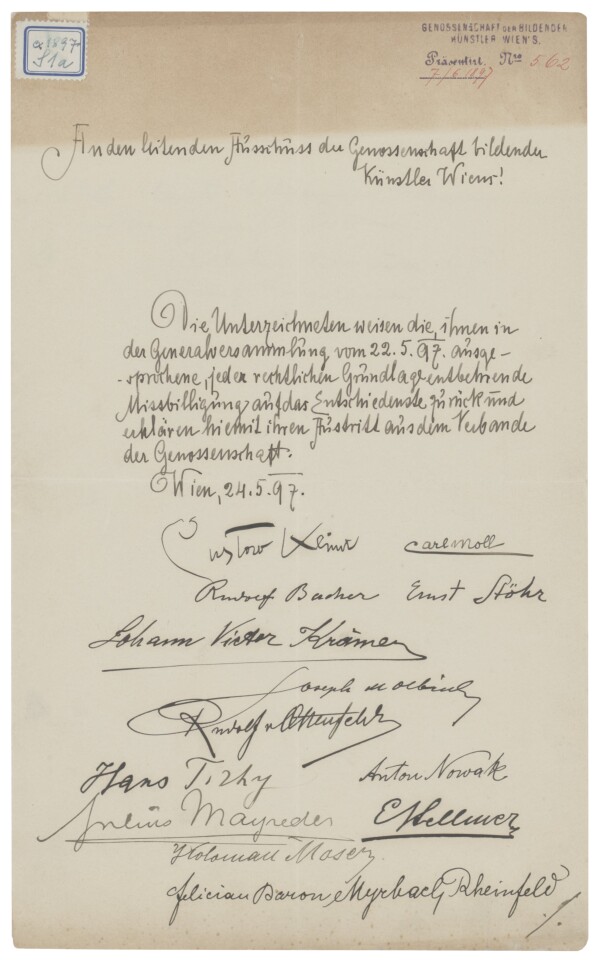

Alfred Roller: Letter written by Alfred Roller to the Committee of the Cooperative of Fine Artists of Vienna, signed by Gustav Klimt, Carl Moll, Rudolf Bacher, Ernst Stöhr, Johann Victor Krämer, Joseph Maria Olbrich, and others., 05/24/1897, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna

The Association of Austrian Artists Vienna Secession was founded in 1897 by a group of artists gathering around Gustav Klimt. The Secession is considered the driving force behind Viennese modernism. That same year, the artists, headed by Klimt as their first president, planned the publication of the organization’s official magazine Ver Sacrum and the construction of their own exhibition building.

Klimt’s Resignation from the Vienna Künstlerhaus and the Formation of the Vienna Secession

Since the early 1890s, Europe’s art world had seen a number of reform movements, most of which had taken place in England, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany. Ambitions for a renewal and the liberation of art led to the foundation of secessions in Düsseldorf (1891), Munich (1892), and, somewhat later, Berlin (1899). Modernism’s budding ideas spread internationally above all through such art magazines as The Studio, Pan, and Jugend. Events on the international art scene also influenced Gustav Klimt, whose artistic development away from Historicism and toward a Symbolist vocabulary of form and liberal manner of painting began to show.

By the fall of 1896, a nucleus had formed in Vienna consisting of members of the Cooperative of Visual Artists (short: Künstlerhaus), including Gustav Klimt, as well as artists from the more loosely organized groups of the so-called Hagen Society and Siebener-Club [Club of Seven]. As their ambitions for a renewal of the exhibition policy and a stronger orientation toward international art movements led to tensions within the more traditionally-minded Cooperative and met with little approval from the rest, they wished to pursue their goals independently and within their own organization. Following several meetings, they installed a “preparatory committee,” which in addition to Klimt also consisted of Carl Moll and Kolo Moser, among others. The committee was assigned the tasks to look for a plot of land for the exhibition building, draft the association’s statutes and rules of procedure for the organization of exhibitions, secure financing, and provide for the necessary conditions for the foundation as such.

The incorporation of the Association of Austrian Artists Vienna Secession finally took place on 3 April 1897. The Secessionists elected Klimt as their first president, in whose name they informed the Künstlerhaus about their constitution, motives, and goals in a letter dated 5 April. It said:

“This concentration of like-minded Austrian artists will first and foremost strive to raise the level of artistic activity and the interest in art in our city and, as soon as it rests on a broader Austrian basis, in the entire monarchy.”

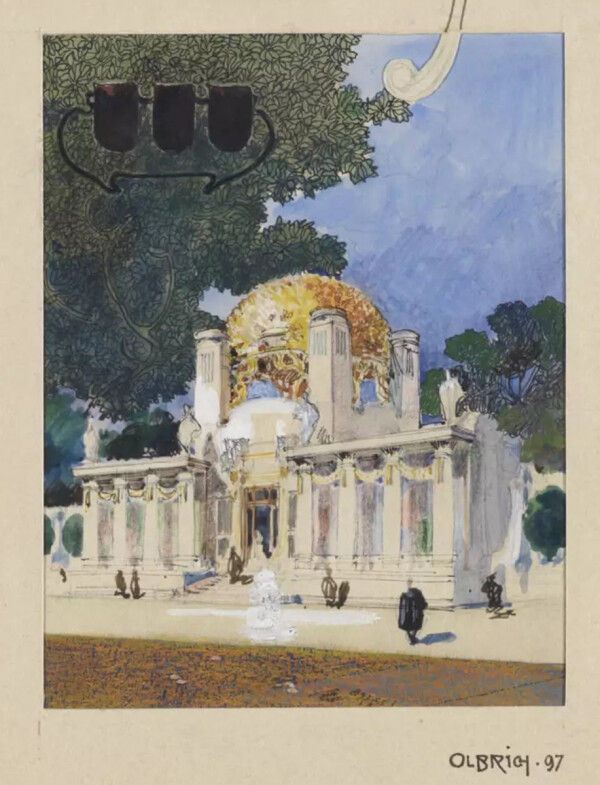

Joseph Maria Olbrich: Design for the building of the Vienna Association, 1897

© Wien Museum

At the same time, they informed daily newspapers and enclosed the Secession’s list of members. Those who were members of the Künstlerhaus wished to remain part of this association, yet notwithstanding pursue their artistic goals in the Secession. However, the founding of the new organization entailed misunderstandings and conflicts, which ultimately led to a fierce dispute in the extraordinary general assembly of the Künstlerhaus on 22 May 1897. Some artists around Klimt announced their resignation in an official letter two days later on 24 May 1897.

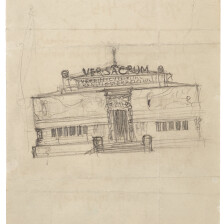

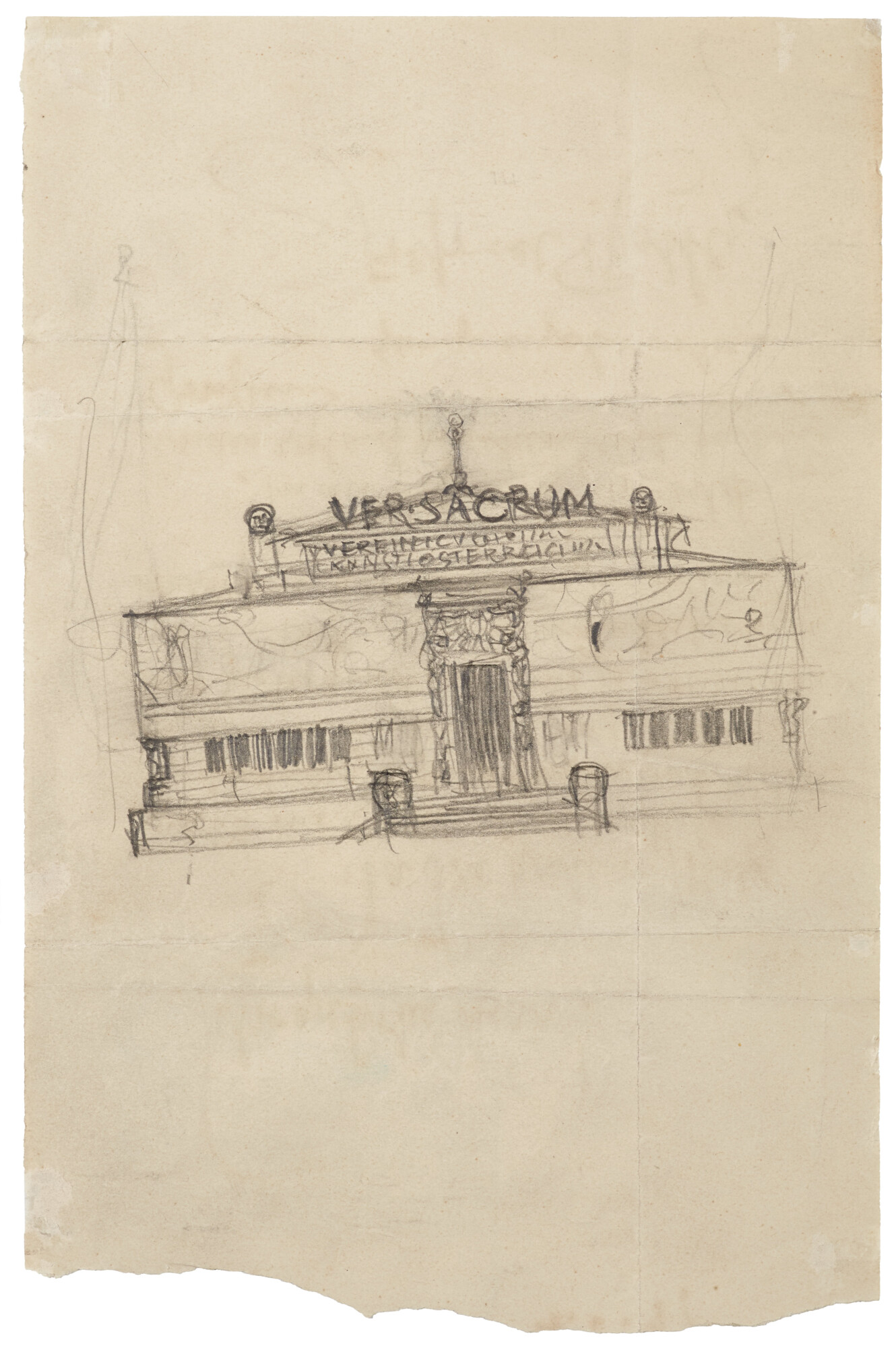

Pavilion of the Secessionists

Planning for an exhibition building began even before the official founding of the Secession, when architect Joseph Maria Olbrich prepared the submission plans for the building project to the Vienna City Council in March 1897. Olbrich had been working in Otto Wagner’s office in 1893, where he was involved in the construction of the Vienna Stadtbahn, a public urban rail transport system. In the summer of 1897, Olbrich presented further designs for the Secession building. Interestingly enough, Klimt also presented two sketches of ideas during this intense planning phase that showed similarities to the interior decoration studies for the music room of the Dumba Palace from around the same period (private collection, Strobl 1980: 319). He drew one of the two Secession sketches on the back of a letter of 4 May 1897 he had received from Alfred Roller. In his design, Klimt placed the inscription “VER SACRUM VEREINIGUNG BILDENDER KÜNSTLER ÖSTERREICHS” in an architrave-like field on the front façade of the cubic building. Above the portal, he added three small shields in the style of the guild emblems.

Architectural Idea Sketches by Gustav Klimt

-

Gustav Klimt: Design for the building of the Vienna Association, 1898, Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Design for the building of the Vienna Association, 1898, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum -

Alfred Roller: Letter from Alfred Roller to Gustav Klimt with a design sketch for the building of Gustav Klimt's Vienna Association , 05/04/1897, Klimt Foundation

Alfred Roller: Letter from Alfred Roller to Gustav Klimt with a design sketch for the building of Gustav Klimt's Vienna Association , 05/04/1897, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

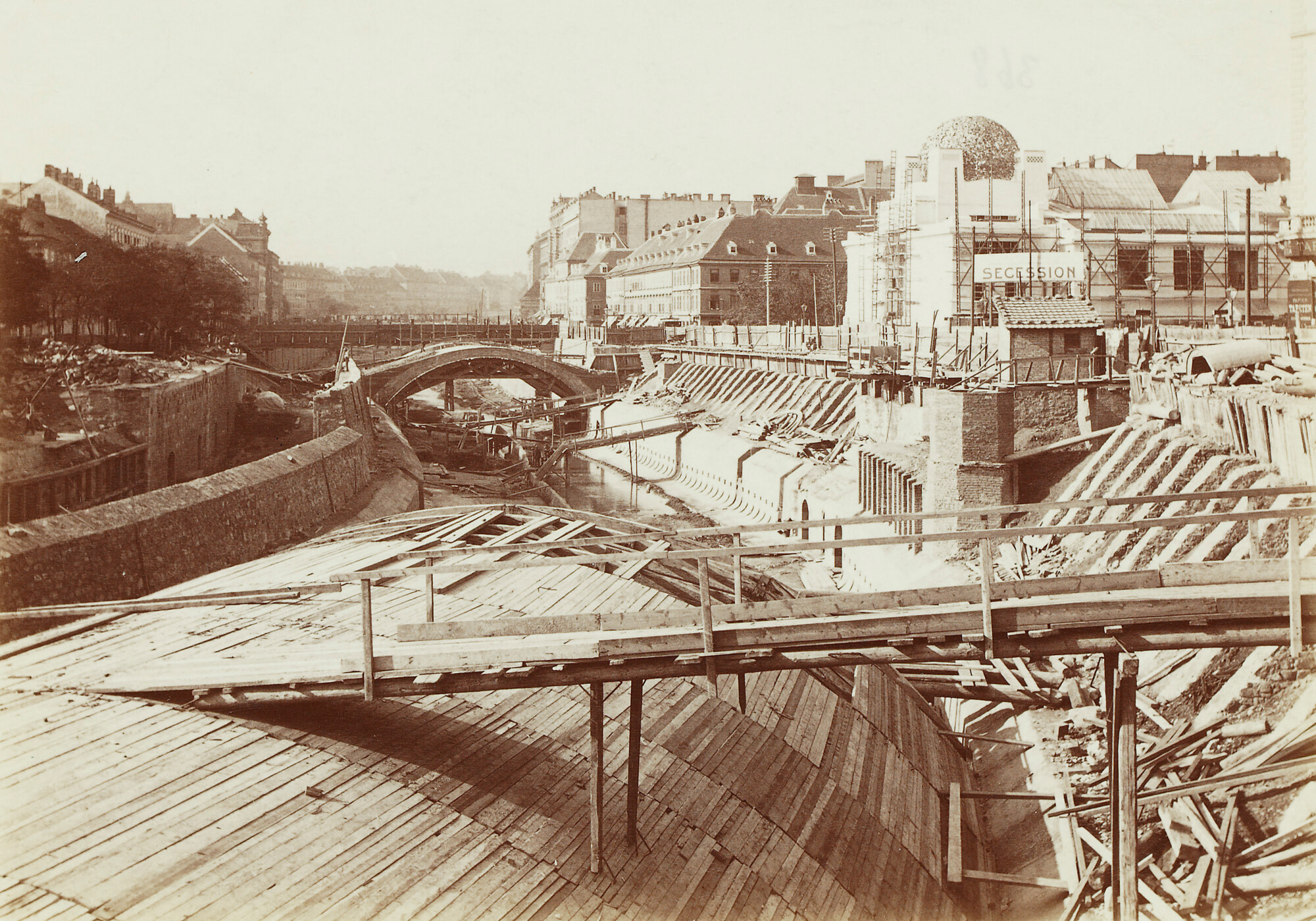

Vienna River dome and Association under construction photographed by Friedrich Strauß, 1898

© Wien Museum, Wien Museum

After lengthy negotiations over the building site, the city council gave its approval for the plot on Linke Wienzeile (now Friedrichstraße) behind the Academy of Fine Arts on 17 November 1897. As the association wished to open its first exhibition already in spring 1898, the working committee decided to rent and adapt facilities of the k. k. Gartenbaugesellschaft (Imperial-Royal Horticultural Society) for this purpose. The foundation stone of the Secession’s own exhibition pavilion was eventually laid on 28 April 1898, and the “art temple” was finished off with a cupola of gilded laurel leaves. On the façade one can still read the Secession’s motto: “DER ZEIT IHRE KVNST. DER KVNST IHRE FREIHEIT” [“To Time Its Art. To Art Its Freedom”].

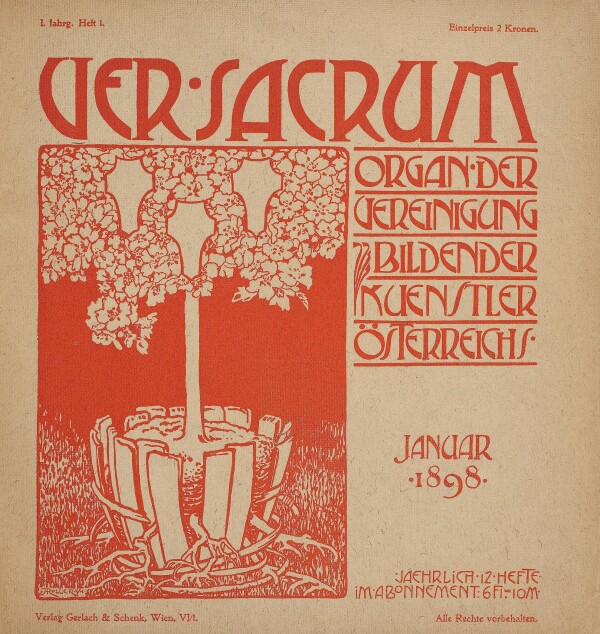

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Official Magazine Ver Sacrum

In its general assembly on 21 July 1897, the interest group of modern artists decided to publish its programmatic ideas in its official magazine Ver Sacrum. To this end, in August 1897 an agreement was entered into with the publishing house Gerlach & Schenk, for which Gustav Klimt had already contributed to the portfolios Allegorien und Embleme [Allegories and Emblems] (from 1881 on) and Allegorien. Neue Folge [Allegories. New Series] (from 1885 on). According to an article in the newspaper Neue Freie Presse of 19 November 1897, the goal of the illustrated art magazine was not only

“to keep the artists occupied apart from the exhibition, but also to impart on Austrian and international audiences a more intimate knowledge of our art life.”

In November, Klimt wrote to Hermann Bahr and asked him to contribute an article to the first issue of Ver Sacrum, which appeared from 1898 on and, with Bahr as a member on the literary advisory committee, became one of the leading magazines of Jugendstil.

Literature and sources

- Brief von Gustav Klimt an die Genossenschaft der bildenden Künstler Wiens, verfasst von fremder Hand (05.04.1897). Mappe Gustav Klimt, .

- Brief verfasst von Alfred Roller an den Ausschuss der Genossenschaft der bildenden Künstler Wiens, unterzeichnet von Gustav Klimt, Carl Moll, Rudolf Bacher, Ernst Stöhr, Johann Victor Krämer, Joseph Maria Olbrich, u.a., Austrittsgesuch (05/24/1897). Mappe Gustav Klimt, .

- N. N.: Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, in: Das Vaterland. Zeitung für die österreichische Monarchie, 06.04.1897, S. 6.

- Hermann Bahr: Unsere Secession, in: Die Zeit, 29.05.1897, S. 139-140.

- Brief von Gustav Klimt an Hermann Bahr (17.11.1897). HS_AM19666Ba.

- N. N.: Der Pavillon der Secessionisten, in: Neue Freie Presse, 19.11.1897, S. 5.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band I, 1878–1903, Salzburg 1980, S. 111-115.

- Marian Bisanz-Prakken (Hg.): Heiliger Frühling. Gustav Klimt und die Anfänge der Wiener Secession 1895–1905, Ausst.-Kat., Albertina (Vienna), 16.10.1998–10.01.1999, Vienna 1999.

- Oskar Pausch: Gründung und Baugeschichte der Wiener Secession. Mit Erstedition des Protokollbuches von Alfred Roller, Vienna 2006.

- Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Erster Jahresbericht der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession, Vienna 1899.

- Franz Smola: Der Zeit ihren Architekten. Joseph Maria Olbrich und die Wiener Secession, in: Ralf Beil, Regina Stephan (Hg.): Joseph Maria Olbrich. 1867‒1908. Architekt und Gestalter der frühen Moderne, Ausst.-Kat., Mathildenhöhe (Darmstadt), 07.02.2010–24.05.2010; Leopold Museum (Vienna), 18.06.2010–27.09.2010, Darmstadt - Vienna 2010, S. 93-113.

Exhibition Activity

Genossenschaft der bildenden Künstler Wiens (Hg.): Katalog der XXIII. Jahresausstellung der Genossenschaft der bildenden Künstler Wiens, Ausst.-Kat., Artists' House (Vienna), 30.03.1895–09.06.1895, Vienna 1895.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Following Klimt’s international debut at the World’s Fair in Antwerp, he exhibited his works primarily at the Vienna Künstlerhaus in the years from 1895 to 1897. The presentations focused on paintings and graphic works that had been created as designs for printed works.

Ever since Klimt had joined the Cooperative of Visual Artists in Vienna in 1891, the rising star on the arts scene exhibited his works primarily at the Künstlerhaus. For the annual exhibitions of 1895 and 1896, Gustav Klimt was also appointed a member of the exhibition panel.

XXIII. Jahresausstellung der Genossenschaft der bildenden Künstler Wiens

The “XXIII. Jahresausstellung der Genossenschaft der bildenden Künstler Wiens” [“23rd Annual Exhibition of the Cooperative of Visual Artists in Vienna”] was held from March to June 1895. Klimt submitted the painting Hanswurst Delivering an Impromptu Performance in Rothenburg (1892–1894, privately owned). The work represented an exception in the artist’s oeuvre. Gustav’s brother Ernst Klimt had begun the easel painting, inspired by his eponymous ceiling painting for the Burgtheater. The work was presumably intended for a private commission. After the premature death of Ernst in 1892, Gustav Klimt completed the composition. At Gustav’s request, the work was shown posthumously under his brother’s name at the annual exhibition. A certain Mr. V. Wokaun – probably Viktor Wokaun, an investor from Prague – purchased the work for 8400 guilders (approx. 126,800 euros).

Reproducing Art

The 1890s were characterized by the medium of reproductions. The publication and duplication of works of art in the form of heliogravures or reproductions in portfolios became increasingly popular. It is therefore not surprising that several exhibitions addressed this topic in the years from 1895 to 1897.

The “III. Internationale Graphische Ausstellung. Jubiläumsausstellung der Gesellschaft für Vervielfältigende Kunst” [“3rd International Graphic Art Exhibition. Jubilee Exhibition of the Society of Fine Art Reproduction”], which was held from October to December at the Künstlerhaus, presented numerous original designs for important printed works created around 1890, including the Portrait of Josef Lewinsky as Carlos in Clavigo (1895, Austrian Gallery Belvedere, Vienna), which Klimt had created for the Society of Fine Art Reproduction as a contribution to the second volume of the luxurious publication Die Theater Wiens.

Genossenschaft der bildenden Künstler Wiens (Hg.): Katalog der XXIV. Jahres-Ausstellung in Wien, Ausst.-Kat., Artists' House (Vienna), 21.03.1896–10.05.1896, Vienna 1896.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Joseph Meder (Hg.): Originalzeichnungen, Ölgemälde, Aquarelle, Drucke und Vorlagenwerke ausgestellt im Künstlerhause von Gerlach & Schenk, Ausst.-Kat., Artists' House (Vienna), 06.09.1896–01.11.1896, Vienna 1896.

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna

Klimt himself commissioned the Society of Fine Art Reproduction to create several reproductions of the painting Hanswurst Delivering an Impromptu Performance in Rothenburg in October 1895. It was probably such reproductions of works by his brother Ernst Klimt that were presented in the aftermath of the “Internationale Kunst-Ausstellung” [“International Art Exhibition”] in Berlin in 1896. On 9 June 1896, the Wiener Zeitung reported about “three brilliantly designed and graciously drawn engravings by Klimt, printed on satin,” which addressed the history of comedy.

XXIV. Jahresausstellung der Genossenschaft der bildenden Künstler Wiens

At the “XXIV. Jahresausstellung der Genossenschaft der bildenden Künstler Wiens” [“24th Annual Exhibition of the Cooperative of Visual Artists in Vienna”], held from 21 March to 10 May 1896, Klimt presented an unidentified watercolor portrait (catalogue number 487). The work, which was also cited as “Woman’s Portrait” in press reviews, sparked ambivalent reactions from critics. The art critic Xaver von Gayrsperg harshly criticized the work in the (Neuigkeits-)Welt-Blatt:

“Gustav Klimt [presents a] surprisingly bad portrait of a crippled creature that would immediately be promoted to a pretty picture by amputation.”

Emmerich Ranzoni from the Neue Freie Presse, however, had a much more positive view of the work and called it a depiction of “captivating charm.”

Presentation of Allegories. New Series

In the autumn of 1896, another exhibition that focused on reproductions and portfolios was held at the Künstlerhaus. Prior to the publication of the collection of designs Allegorien. Neue Folge [Allegories. New Series], Martin Gerlach organized an exhibition at the Künstlerhaus titled “Ausstellung von Originalen und Publicationen der Firma Gerlach & Schenk” [“Exhibition of Originals and Publications of the Gerlach & Schenk Company”] on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of his publishing company, which specialized in art and industry. Gustav Klimt presented a total of 9 studies for both the first series and the second, then still unpublished, series. These included the painting Allegory of Love (1895, Wien Museum), created only the year before. While Klimt’s older allegories, such as the Allegory of Fable (1883, Wien Museum), were still praised, reviews of his latest works were rather critical:

“G. Klimt’s mystical picture Love (4) will be met with much applause, but possibly also with some rejection. It is peculiar, yet good.”

With this review, dated 10 September 1896, the Deutsches Volksblatt alerted its readers to the painter’s changed approach for the first time. The press had hitherto regarded Klimt – as well as Franz Matsch – purely as a master of decorative painting. Klimt’s abandonment of detailed naturalism in the years to come would result in the founding of the Vienna Secession and the scandal surrounding the Faculty Paintings.

Turning Away from the Künstlerhaus

Klimt’s first disagreements with the Cooperative of Visual Artists in Vienna became notable as early as 14 April 1897. In a letter, the artist informed the cooperative that he was “regrettably unable […] to comply with the honorable committee’s flattering request to present my picture ‘Palace Theater in Totis’ in the exhibition.” The letter shows that Klimt was no longer interested in the presentation of his works in the annual exhibitions of the Künstlerhaus. Further disputes concerning the exhibition policy of the Cooperative of Visual Artists in Vienna led to the founding of the Association of Austrian Artists Vienna Secession in 1897. Klimt and other members of the Secession officially left the Künstlerhaus on 25 April 1897.

Literature and sources

- Christian M. Nebehay (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Dokumentation, Vienna 1969.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012.

- Emmerich Ranzoni: Jahresausstellung im Künstlerhause, in: Neue Freie Presse (Morgenausgabe), 21.03.1896, S. 6.

- N. N.: Theater, Kunst und Literatur. Künstlerhaus, in: Deutsches Volksblatt, 10.09.1896, S. 9.

- X. von Gayrsperg: Künstlerhaus. Die XXIV. Jahres-Ausstellung, Teil 2, in: Neuigkeits-Welt-Blatt, 17.04.1896, S. 10.

- N. N.: Theater und Kunst, in: Wiener Zeitung, 09.06.1896, S. 4.

- Herbert Giese: Franz von Matsch – ein Wiener Maler der Jahrhundertwende, in: Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien (Hg.): Franz von Matsch. Ein Wiener Maler der Jahrhundertwende, Ausst.-Kat., Museums of the City of Vienna (Vienna), 12.11.1981–31.01.1982, Vienna 1981, S. 9-28.

- Österreichische Kunst-Chronik, Nummer 16 (1894), S. 468.

- Deutsches Volksblatt (Morgenausgabe), 22.10.1895, S. 2.

- Brief von Gustav Klimt an Unbekannt (04/05/1895). 18.2.2.4577, .

- Revers der Gesellschaft für Vervielfältigende Kunst von Gustav Klimt (04/27/1895).

- Brief von Gustav Klimt an die Genossenschaft der bildenden Künstler Wiens (presumably 04/14/1897). Mappe Gustav Klimt, .

- Brief verfasst von Alfred Roller an den Ausschuss der Genossenschaft der bildenden Künstler Wiens, unterzeichnet von Gustav Klimt, Carl Moll, Rudolf Bacher, Ernst Stöhr, Johann Victor Krämer, Joseph Maria Olbrich, u.a., Austrittsgesuch (05/24/1897). Mappe Gustav Klimt, .

- Joseph Meder (Hg.): Originalzeichnungen, Ölgemälde, Aquarelle, Drucke und Vorlagenwerke ausgestellt im Künstlerhause von Gerlach & Schenk, Ausst.-Kat., Artists' House (Vienna), 06.09.1896–01.11.1896, Vienna 1896.

- Genossenschaft der bildenden Künstler Wiens (Hg.): Katalog der XXIII. Jahresausstellung der Genossenschaft der bildenden Künstler Wiens, Ausst.-Kat., Artists' House (Vienna), 30.03.1895–09.06.1895, Vienna 1895.

- Gesellschaft für Vervielfältigende Kunst (Hg.): Katalog der graphischen Ausstellung des Jahres 1895. Originalarbeiten der Gegenwart - der Holzschnitt seit dem Jahre 1886 - Jubiläumsausstellung der Gesellschaft, Ausst.-Kat., Artists' House (Vienna), 18.10.1895–12.12.1895, Vienna 1895.

- Genossenschaft der bildenden Künstler Wiens (Hg.): Katalog der XXIV. Jahres-Ausstellung in Wien, Ausst.-Kat., Artists' House (Vienna), 21.03.1896–10.05.1896, Vienna 1896.

Drawings

Gustav Klimt: Bust portrait of a child, circa 1895, The Albertina Museum

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of a lady with cape and hat, 1897/98, The Albertina Museum

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

The drawings made in the three years between 1895 and 1897 impressively attest to Gustav Klimt’s embrace of Symbolism and the advent of Jugendstil. As a draftsman he tackled his motifs by meticulously studying his models. The artwork designed in 1897/98 for Ver Sacrum illustrates Klimt’s increasing interest in flatness.

Klimt’s drawings for the portfolio Allegorien: Neue Folge [Allegories: New Series] are among the Viennese artist’s most well-known creations from those years. Bust of a Child and Bust of a Baldheaded Old Man (both 1895, Albertina, Vienna, S 1980: 261 and S 1980: 260) combine a naturalistic approach with the emphatically descriptive quality of Klimt’s pencil strokes. Soft modeling enabled him to especially work out the three-dimensional qualities of the faces. Klimt contrasts the frizzy curls of the angelic child with rigid hatching in the background, and with the aid of light creates the impression of volume and expanse in the lavish hair. In terms of posture and direction of the gaze, both drawings already closely resemble the figures in Klimt’s Allegory of Love (1895, Wien Museum, Vienna). The painter must thus have made them at a later point in time in the process of the work’s genesis.

Gustav Klimt increasingly established drawing as an autonomous medium in his oeuvre. He considered Portrait of a Lady in a Cape and Hat (Albertina, Vienna, S 1980: 389) as sufficiently accomplished to present it at the Secession’s first exhibition in March 1898. Moreover, he had this drawn masterpiece reproduced in the magazine Ver Sacrum. The face, which is framed by the hat and cape, is illuminated through a brightly lit window on the right. The subtle use of black chalk permits Klimt to let the anonymous figure emerge from the darkness. This dramatic and most impressive half-length portrait is vaguely reminiscent of drawings made around the same time by the Paris-based artist and printmaker Eugène Carrière, who was greatly admired by the Secessionists and could eventually be won over as a member of the Secession. The transition from objective realism to subjective neo-idealism was formulated as early as the beginning of 1898, inspired by Carrière’s lithographs. The art critic Rudolf Klein’s review of the latter might also fit for Klimt’s master drawing:

“[…] Carrière, in whose lithographs the soul, stripped of all outward appearances, twitches in ethereal semblance, just like in the oil paintings.”

Other drawings by Klimt that also appeared in this very issue of Ver Sacrum dedicated to him seem essentially different, however. The soft, tonal modeling has given way to a flat configuration reduced to values of light and dark. The Blood of Fish (private collection, S 1980: 675), Initial D (Albertina, Vienna, S 1980: 342), Flying Tripod (Albertina, Vienna, S 1980: 352), and Nuda Veritas (1898, Wien Museum, Vienna, S 1980: 350) adopt motifs from his oil paintings made around the same time, such as Moving Water (1898, private collection), translating them into the two-dimensional style of flatness. Great importance was assigned to the ornamentation of the composition.

These designs for book ornaments, which are rare in Klimt’s oeuvre, follow contemporary developments in Paris, which the artist discovered in the prints by Parisian artists like Eugène-Samuel Grasset, Georges Auriol, and Alfons Mucha.

Literature and sources

- Marian Bisanz-Prakken (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Ausst.-Kat., Albertina (Vienna), 14.03.2012–10.06.2012; Getty Center (Los Angeles), 03.07.2012–23.09.2012, Munich 2012, S. 166-173.

- Rudolf Klein: Internationale Lithographien-Ausstellung im Kunstgewerbe-Museum zu Düsseldorf, in: Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, Band 2 (1898), S. 264-276.