Klimt's work focuses on all aspects of the Art Nouveau master's oeuvre. Visualized through a timeline, Klimt's creative periods are rolled up here, starting with his training, his collaboration with Franz Matsch and his brother Ernst in the "Künstler-Compagnie", the affair surrounding the faculty paintings and his post-fame and the myth that still surrounds this exceptional artist today.

The Final Years

In the last three years of his life, Gustav Klimt increasingly turned to the female portrait. He celebrated both illustrious personalities and anonymous models with his painterly refinement and Asian motifs. As to the landscapes, the artist drew his inspirations from his stays on the Attersee until 1916, while in his allegories he continued to deal with the theme of Eros and Thanatos.

→

Gustav Klimt: The Bride, 1917/18, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Commissioned Portraits

From the summer of 1914, World War I and the devaluation of money it entailed reduced Klimt’s income considerably. It was presumably for this reason that he increasingly turned to portrait commissions. Stylistically, they stand out for their bright, gaudy colors, modern garments, and Asian motifs.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Friederike Maria Beer, 1916, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, The Mizne-Blumental Collection

© Tel Aviv Museum of Art

Portraits of Anonymous Ladies

In the last four years of his life, Gustav Klimt painted a series of portraits of anonymous ladies. Their characteristic features are fashionable accessories, Asian backdrops, and the bright colors typical of the artist’s late style. In just under four years, Klimt produced more than ten paintings of sophisticated anonymous women, thus revisiting the type of the “Viennese belle” that had already preoccupied the “Painter of Women” in his early years.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Lady with a Muff, 1916/17, private collection

© Gallery Welz Salzburg

Late Allegories

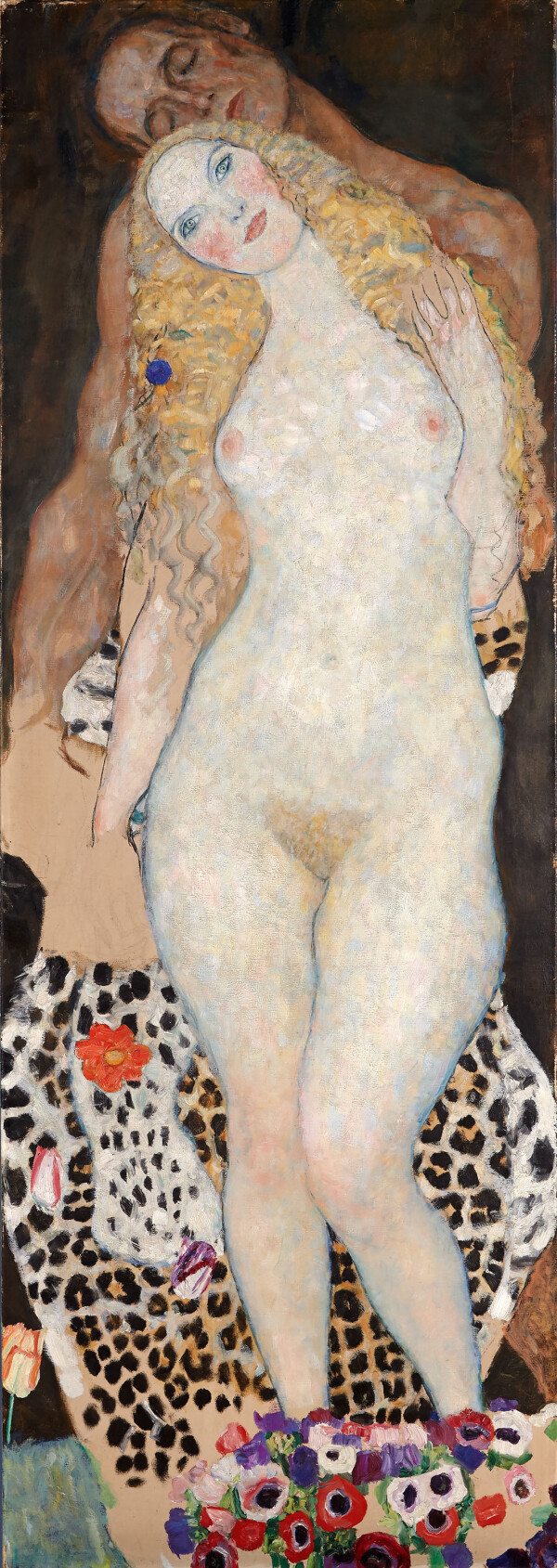

In September 1917, Gustav Klimt presented 13 oil paintings at the Österrikiska Konstutställningen [Austrian Art Exhibition] in Stockholm, including two of his latest allegories: Leda and Baby. Together with the unfinished works The Bride and Adam and Eve, they constitute the artist of the century’s artistic legacy.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Adam and Eve, 1916-1918, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

Bad Gastein as a Source of Inspiration

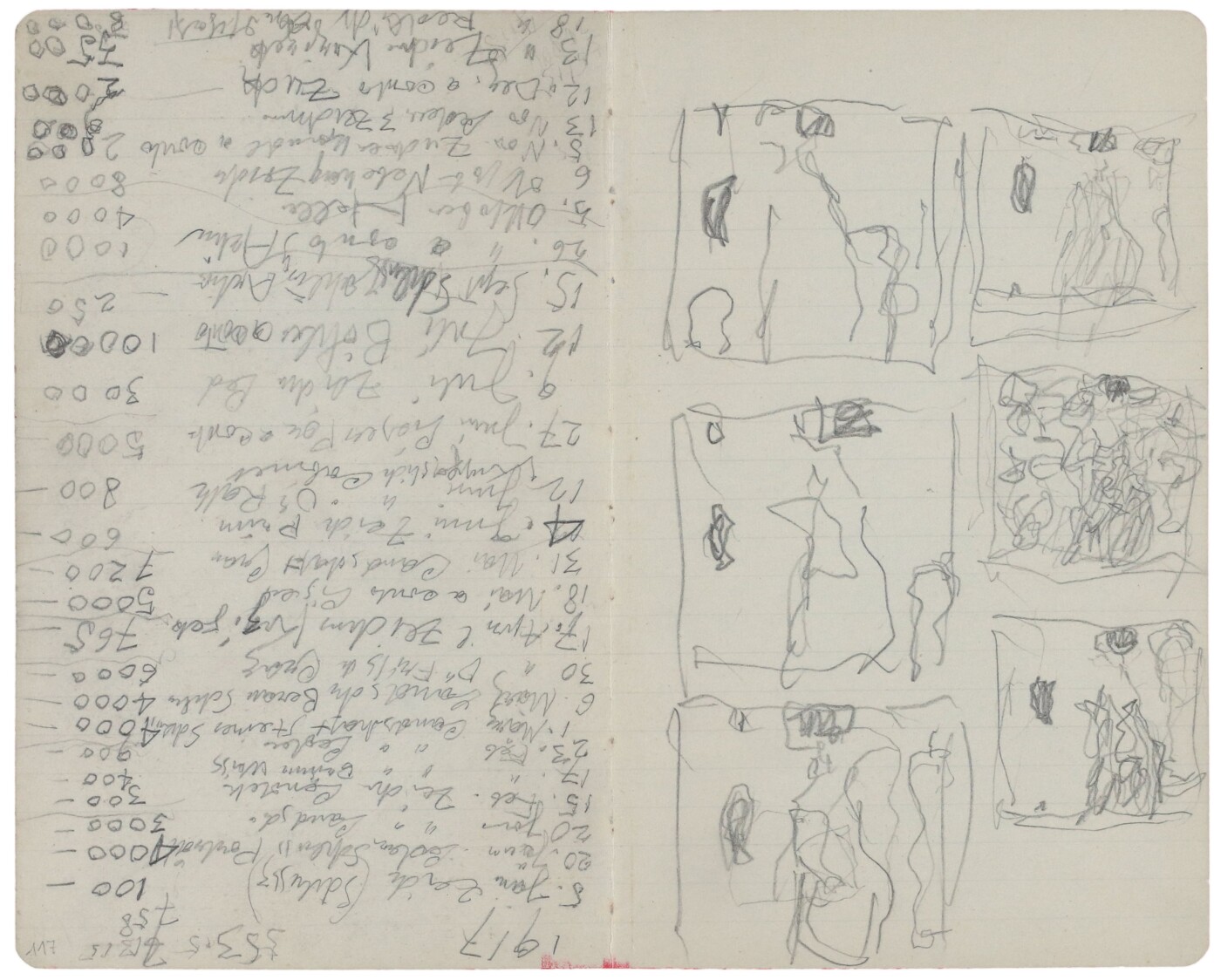

Starting in 1912, Gustav Klimt and Emilie Flöge mostly spent the month of July in the health spa resort of Bad Gastein. The oil sketch measuring 70 by 70 centimeters, as well as a composition study and smaller sketches of details in the painter’s last sketchbook indicate his artistic interest in the resort. The oil sketch was first owned by August and Serena Lederer. A black-and-white photograph by Moriz Nähr and a collotype print in Max Eisler’s Gustav Klimt portfolio, as well as several descriptions document the work, which is now considered lost.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Gastein, 1917, Verbleib unbekannt

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

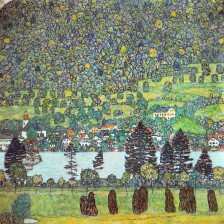

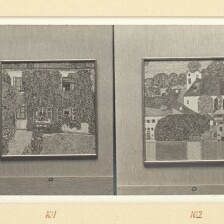

Last Stays on the Attersee

Between 1914 and 1916, Gustav Klimt spent his last three summers on the southern shore of the Attersee. He rented a remote forester’s lodge in Weißenbach, which appears in two painted views. Apart from picturesque garden landscapes, he also captured Unterach on the southwestern shore and Litzlberg, located in the north of the lake, in oil on canvas – twice and three times respectively.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Litzlberg on the Attersee, circa 1915, private collection

© Sotheby's

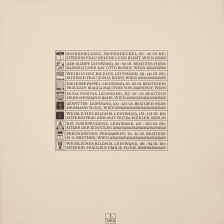

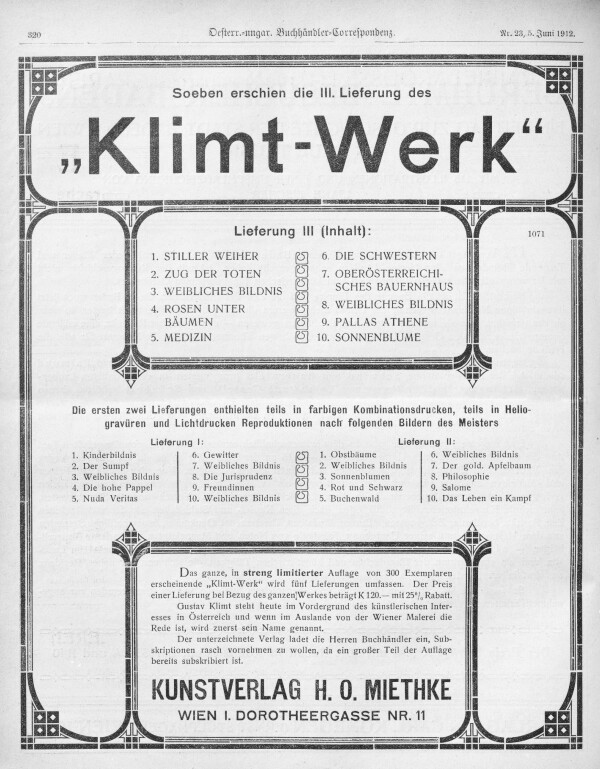

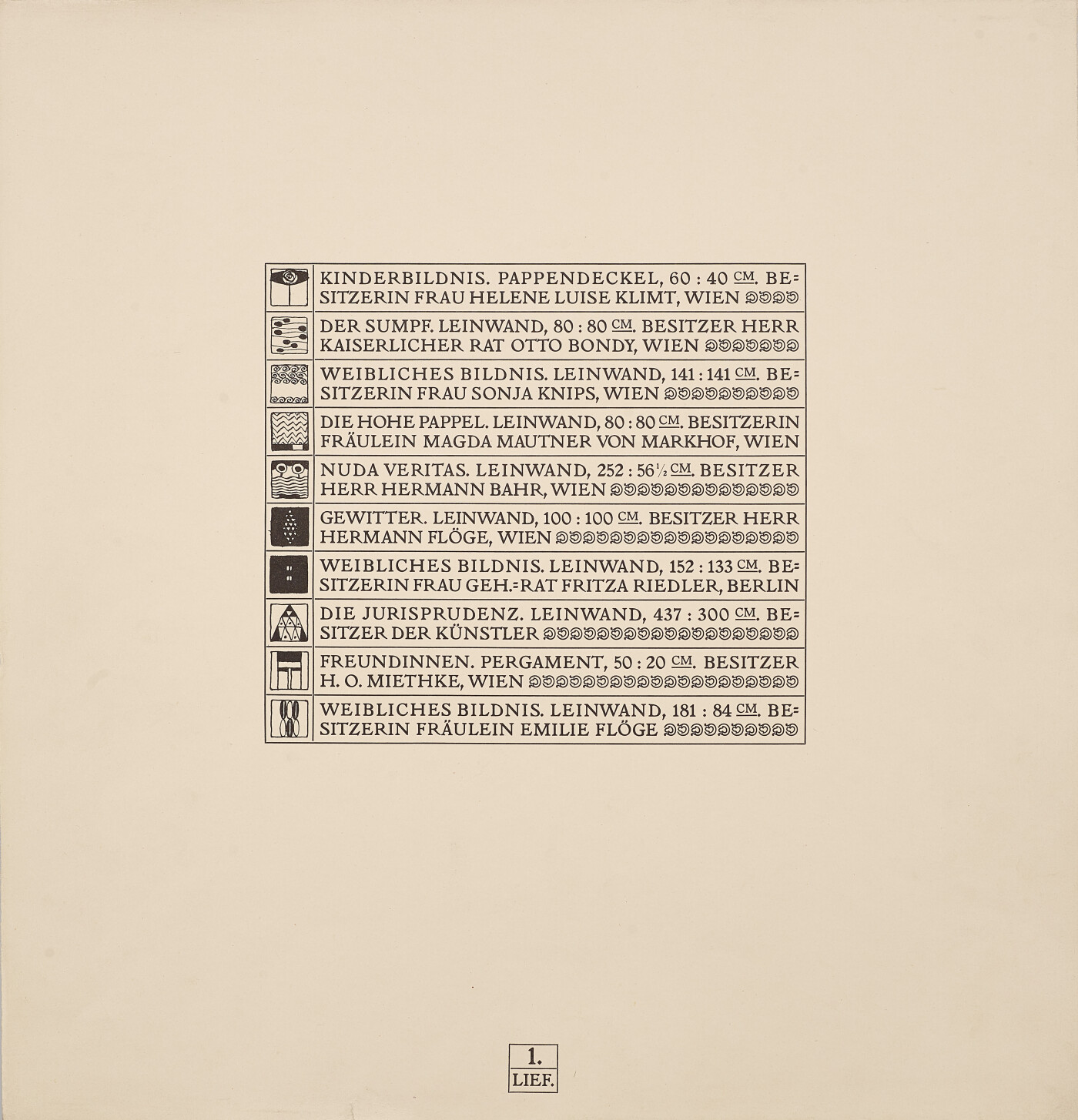

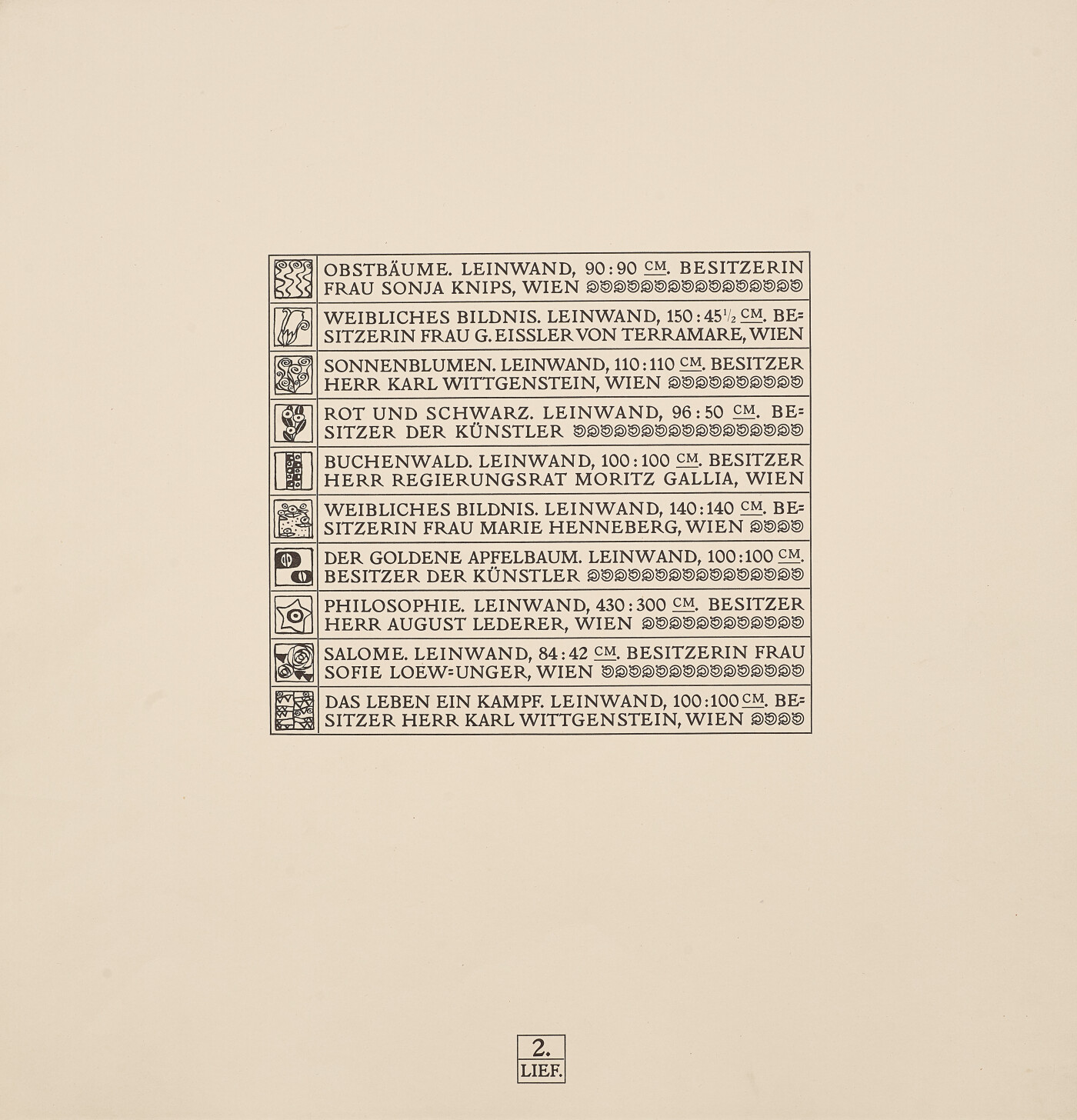

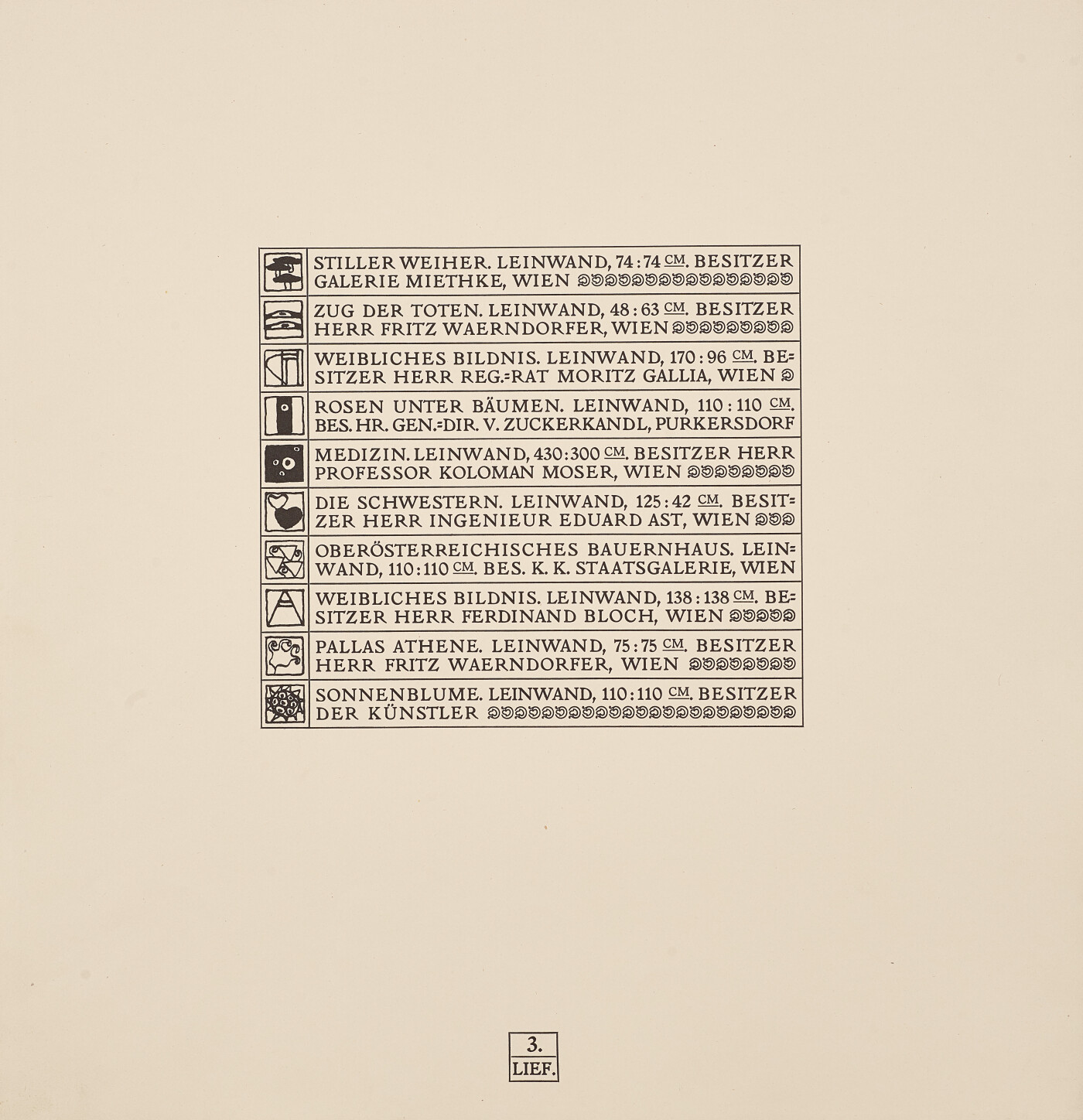

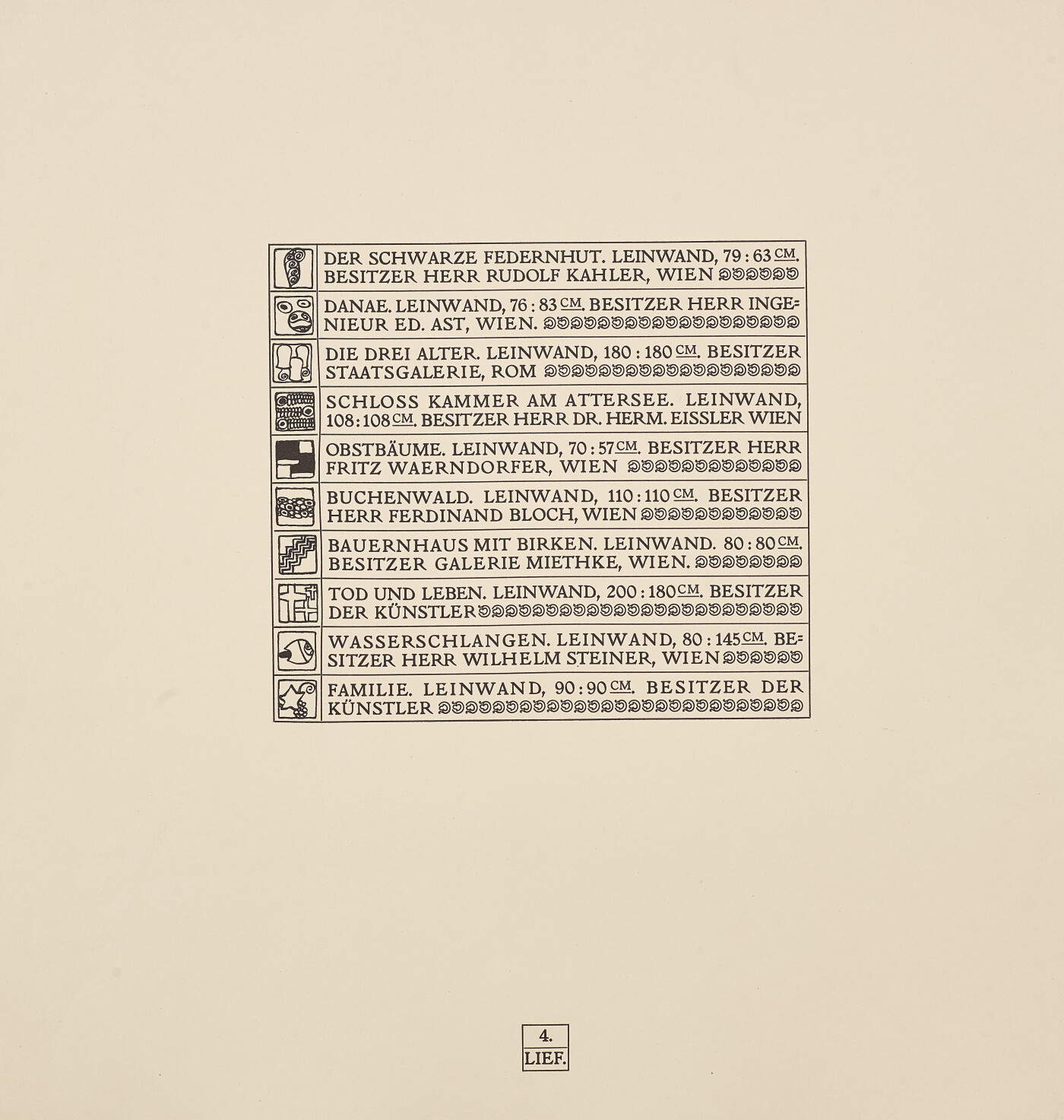

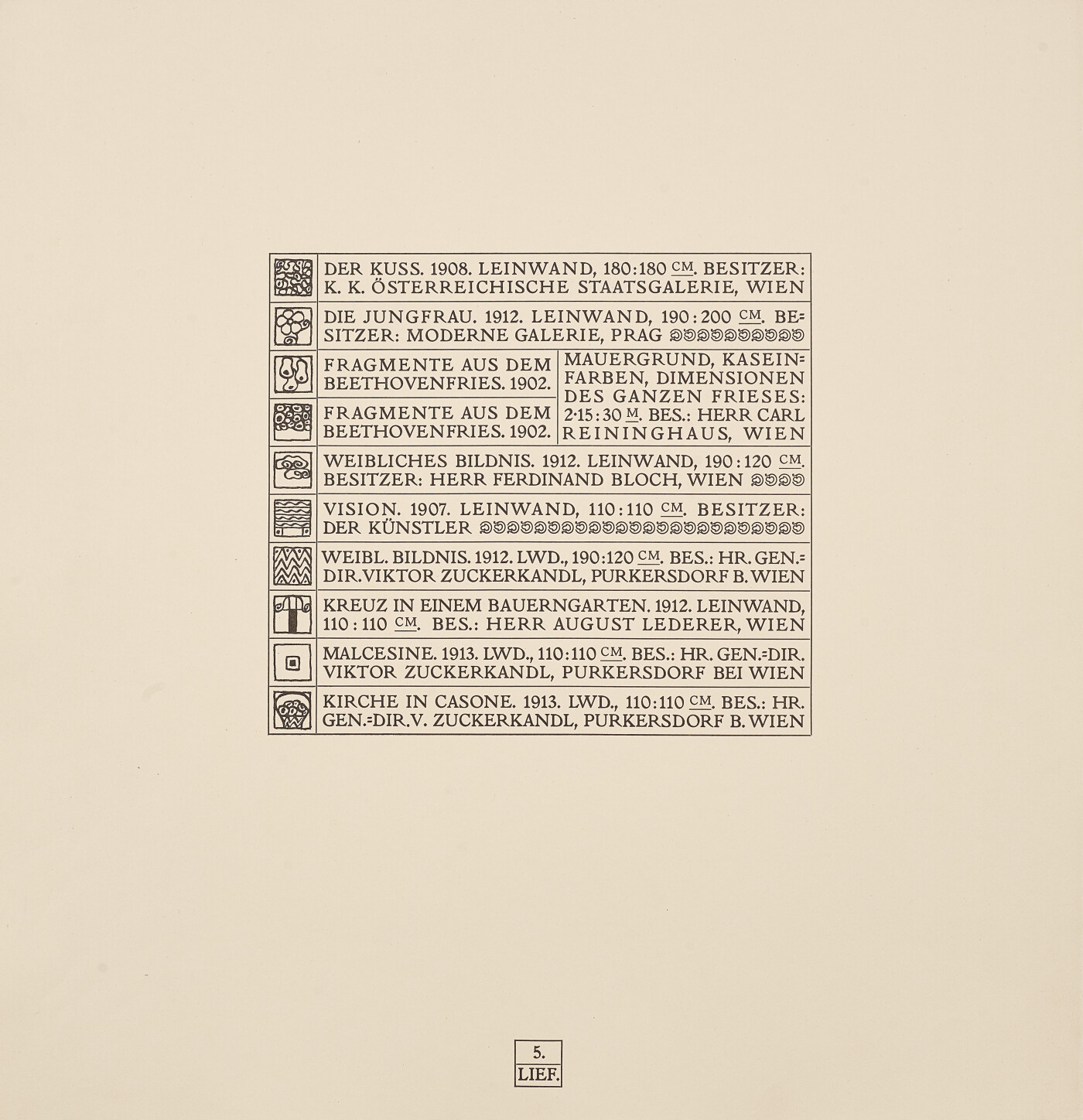

The Work of Gustav Klimt. The Heller Portfolio

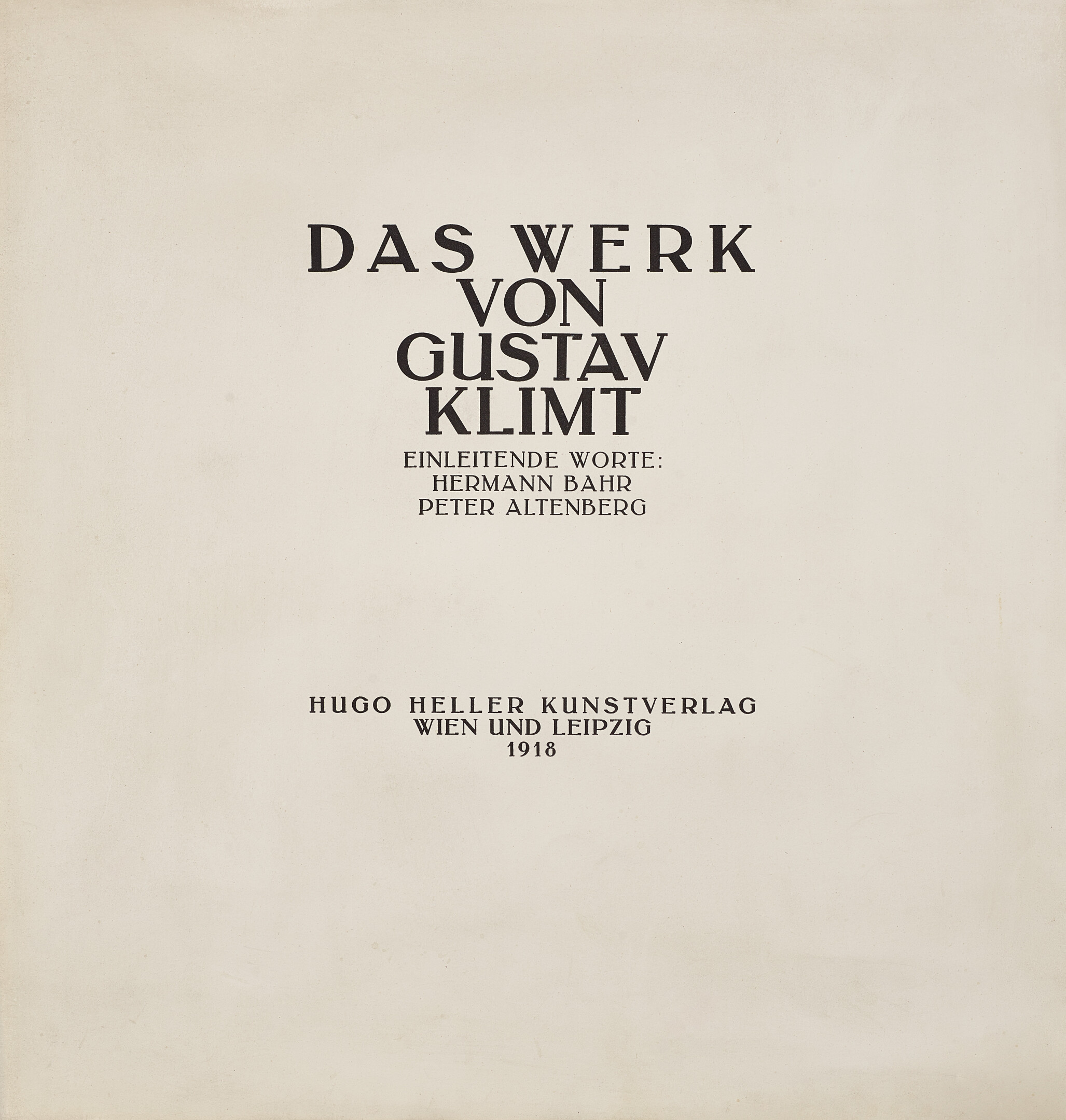

Das Werk von Gustav Klimt [The Work of Gustav Klimt], referred to as Heller Portfolio, as it was edited by art publisher Hugo Heller in 1918, was the continuation of the so-called Miethke Portfolio. After Klimt’s death, it brought to mind again Klimt’s oeuvre on a high quality level in terms of reproduction technique and is still considered a coveted collector’s item.

To the chapter

→

Kunstverlag Hugo Heller (Hg.): Das Werk von Gustav Klimt, Vienna - Leipzig 1918.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

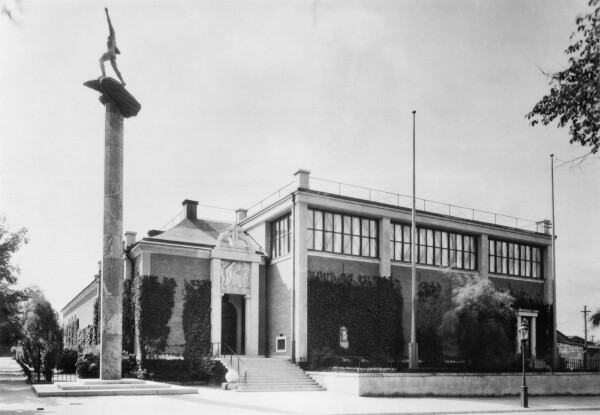

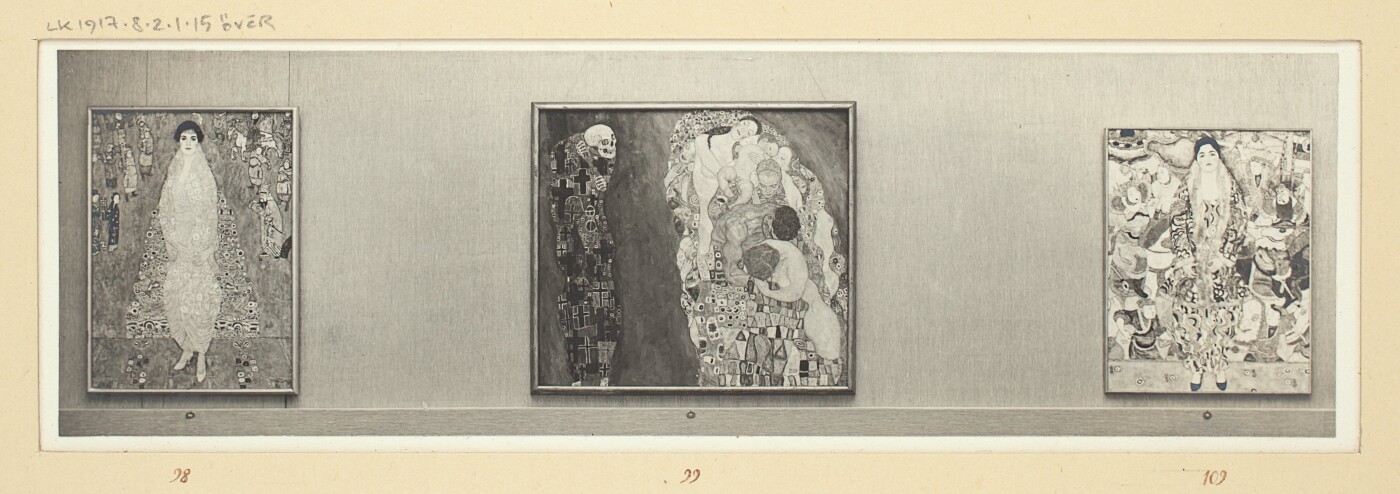

Exhibition Activity

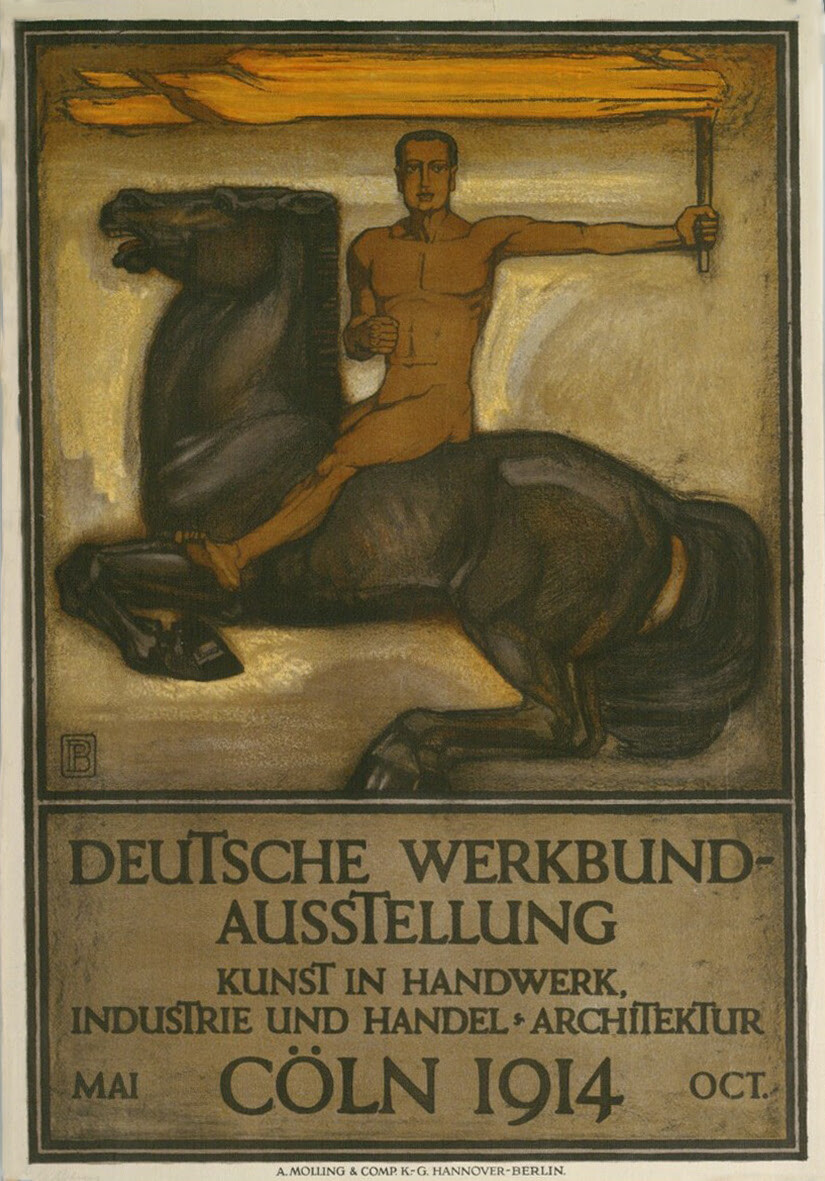

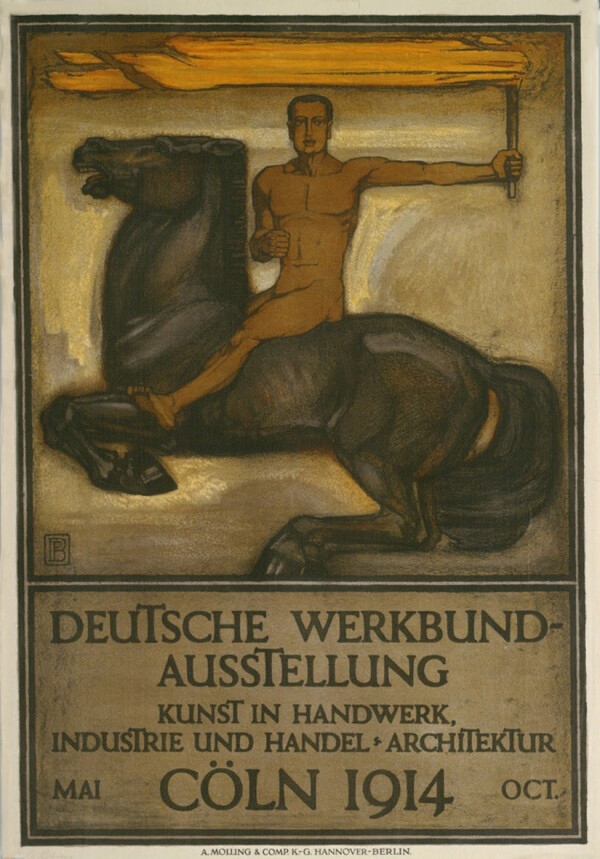

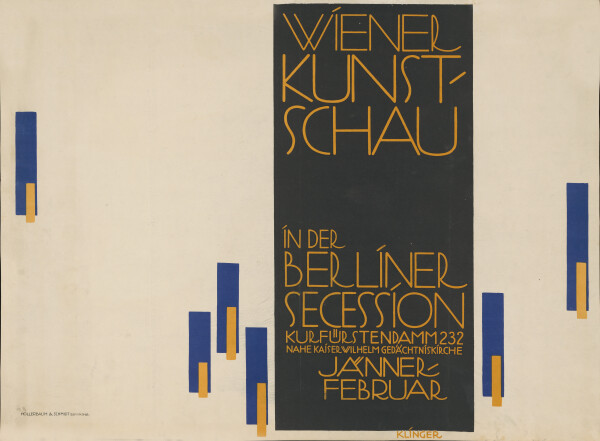

During World War I, Klimt accepted invitations from a number of artists’ associations from abroad. In addition to exhibitions organized by the German-Bohemian Artists’ League, the Secession in Rome, the Deutscher Werkbund, and the Berlin Secession, he took part in two important exhibitions of Austrian art in Scandinavia in 1917/18. The show in Stockholm would be the last major presentation of the master’s recent work before his death in early 1918.

To the chapter

→

Peter Behrens: Poster of the German Werkbund Exhibition Cologne, 1914

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

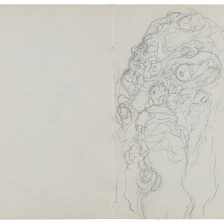

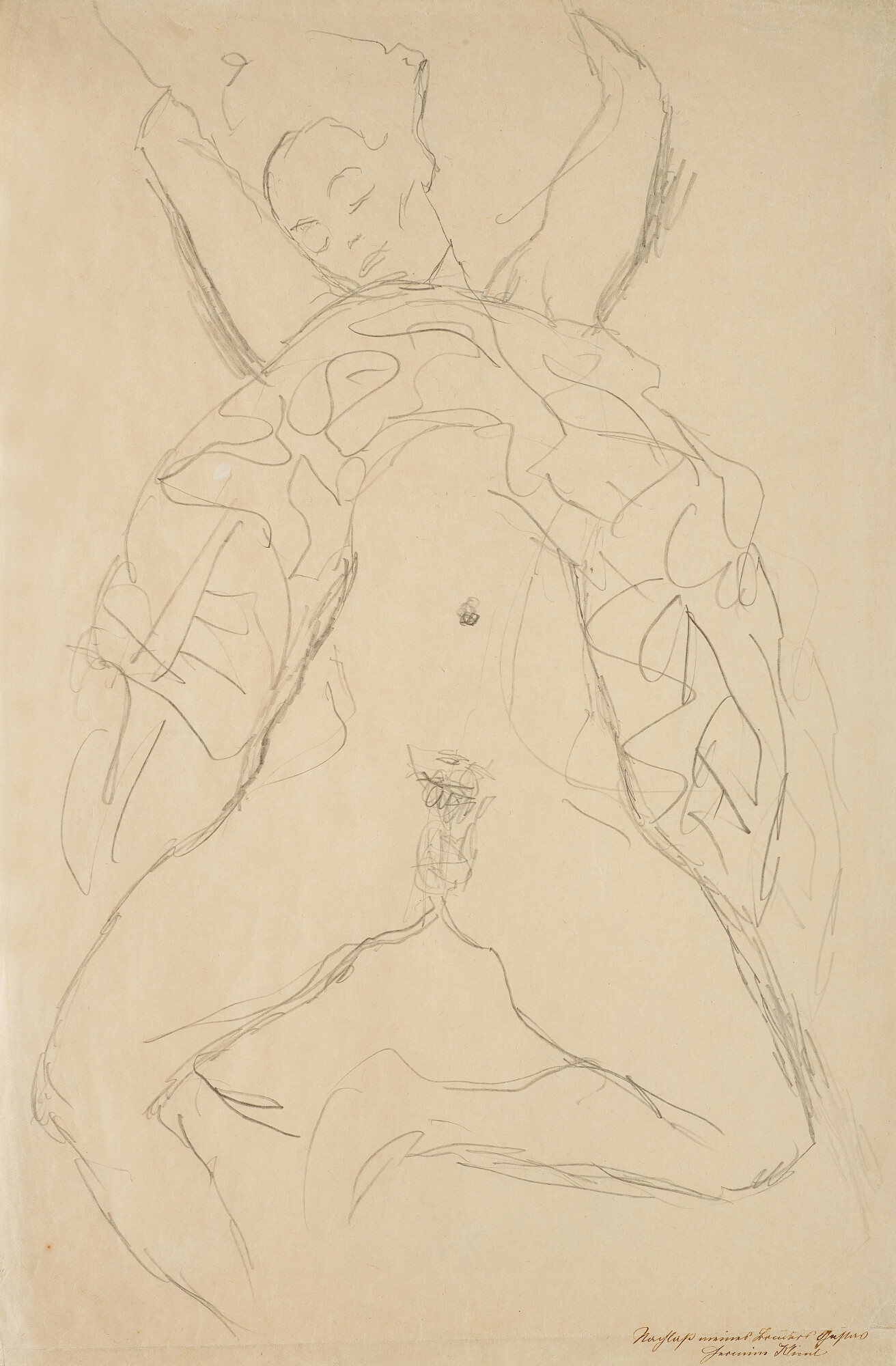

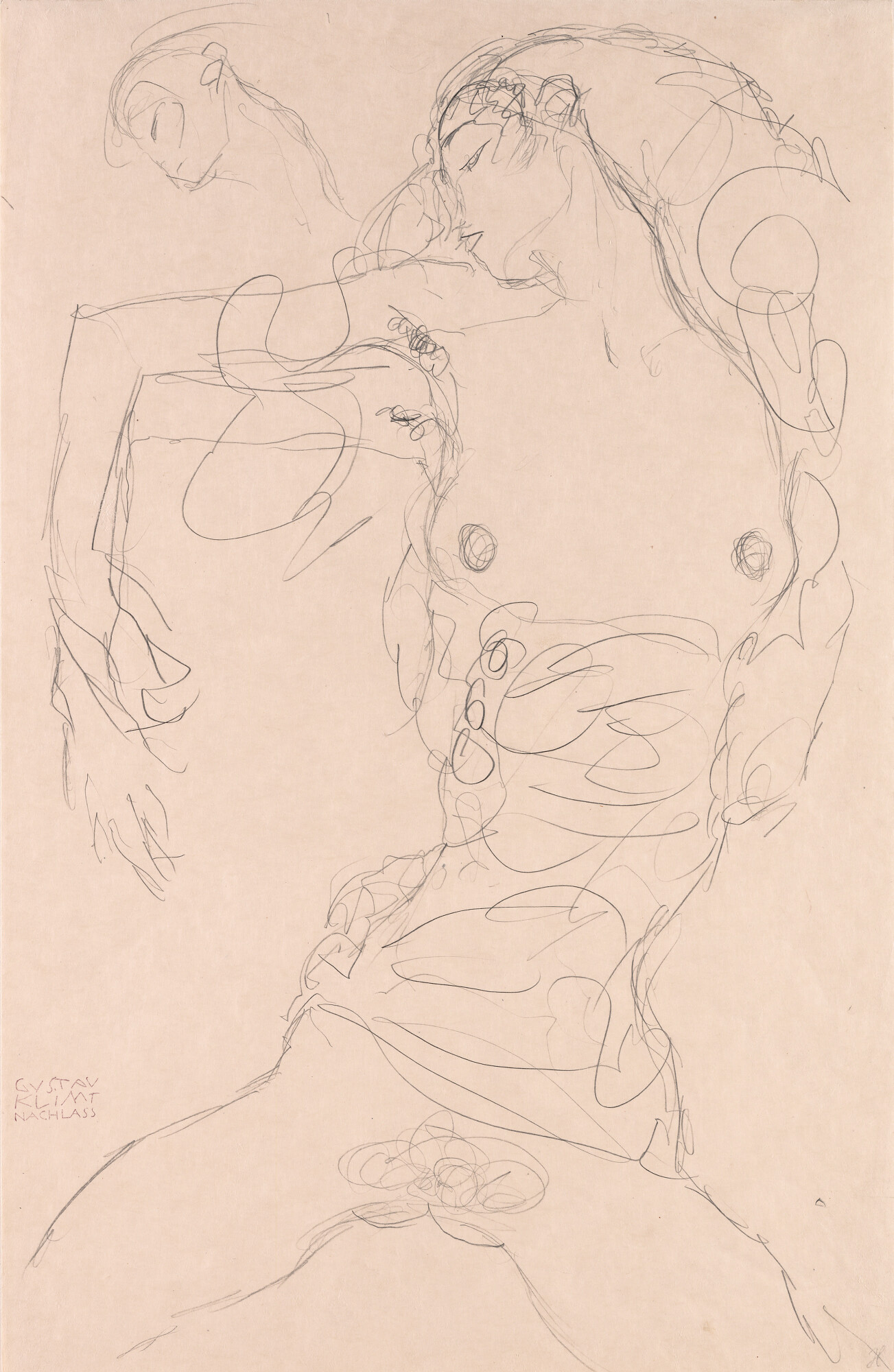

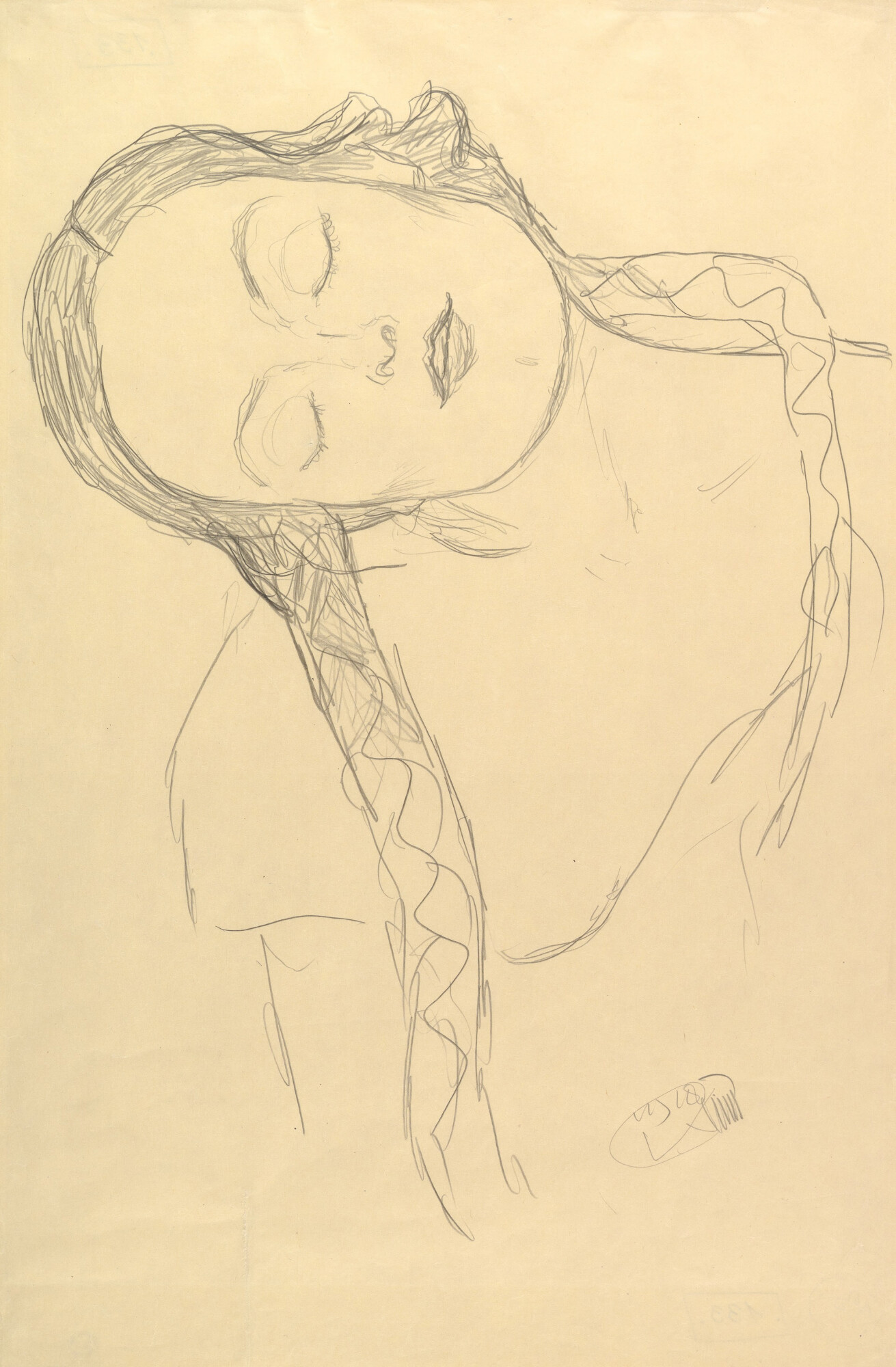

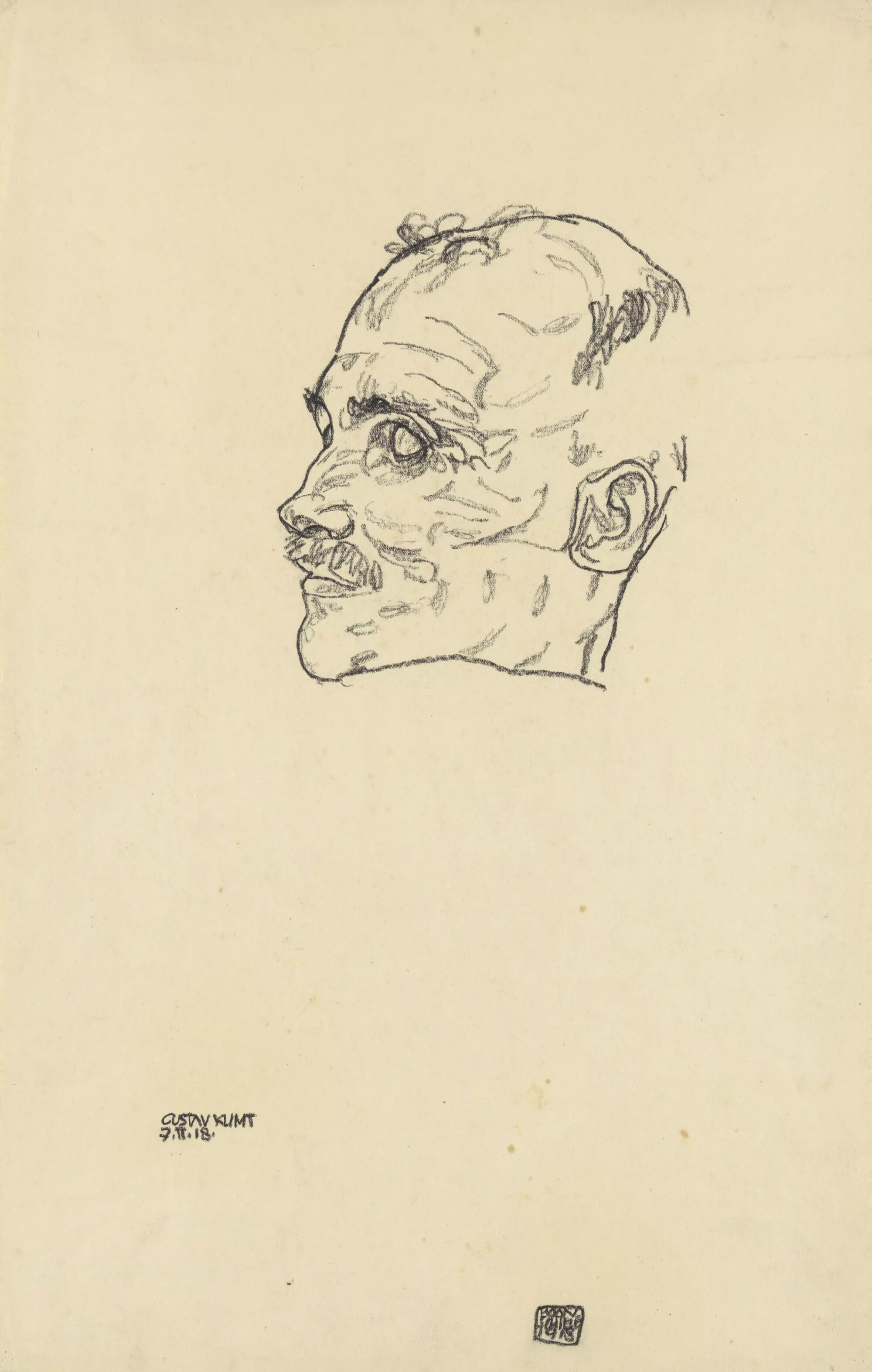

Drawings

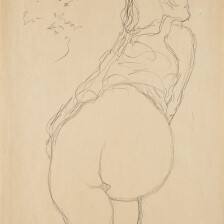

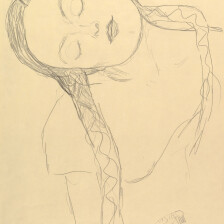

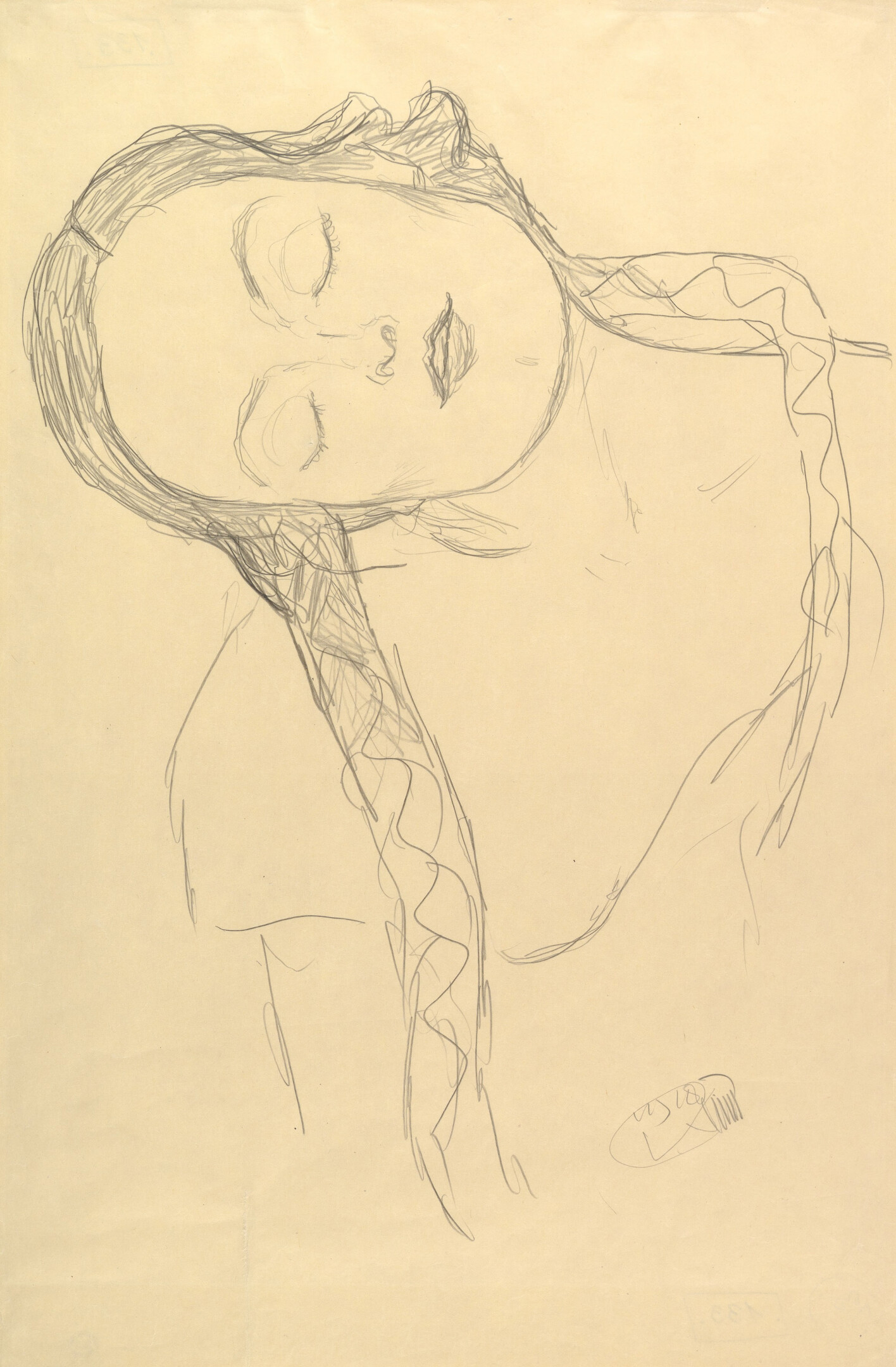

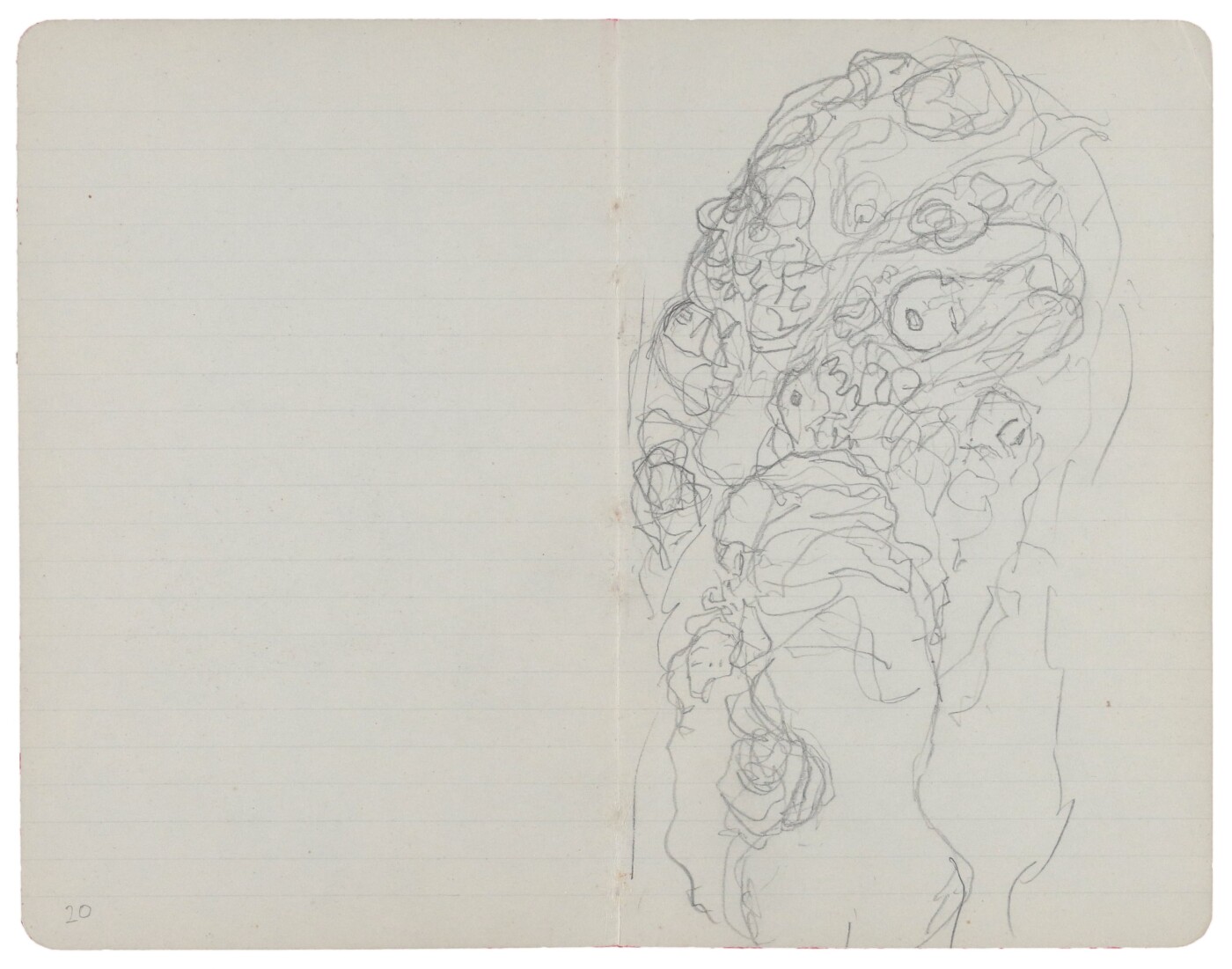

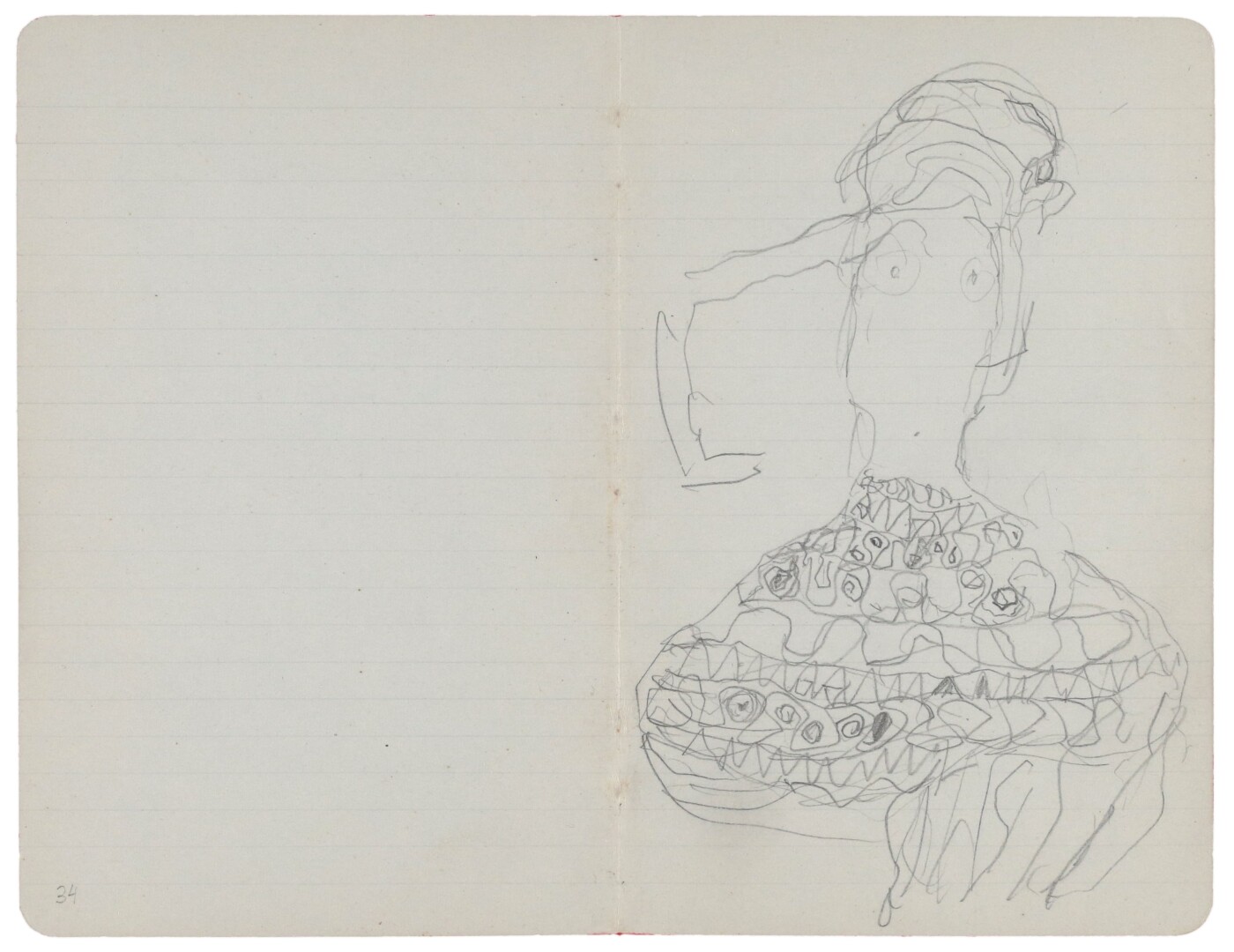

In his late drawings, besides studies for commissioned portraits, Klimt again devoted himself to the erotic female nude. It was above all for his monumental work The Bride (1917/18, unfinished, Klimt-Foundation, Vienna) that he created a multitude of nude drawings exhibiting both the free painterly style of his late work and an increasing tendency toward expression.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Bust portrait of a girl with falling braids, her head tilted to the left, circa 1917, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

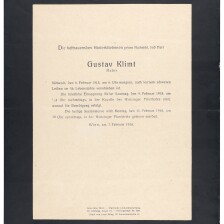

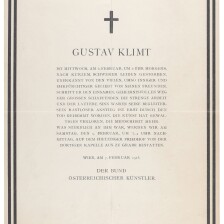

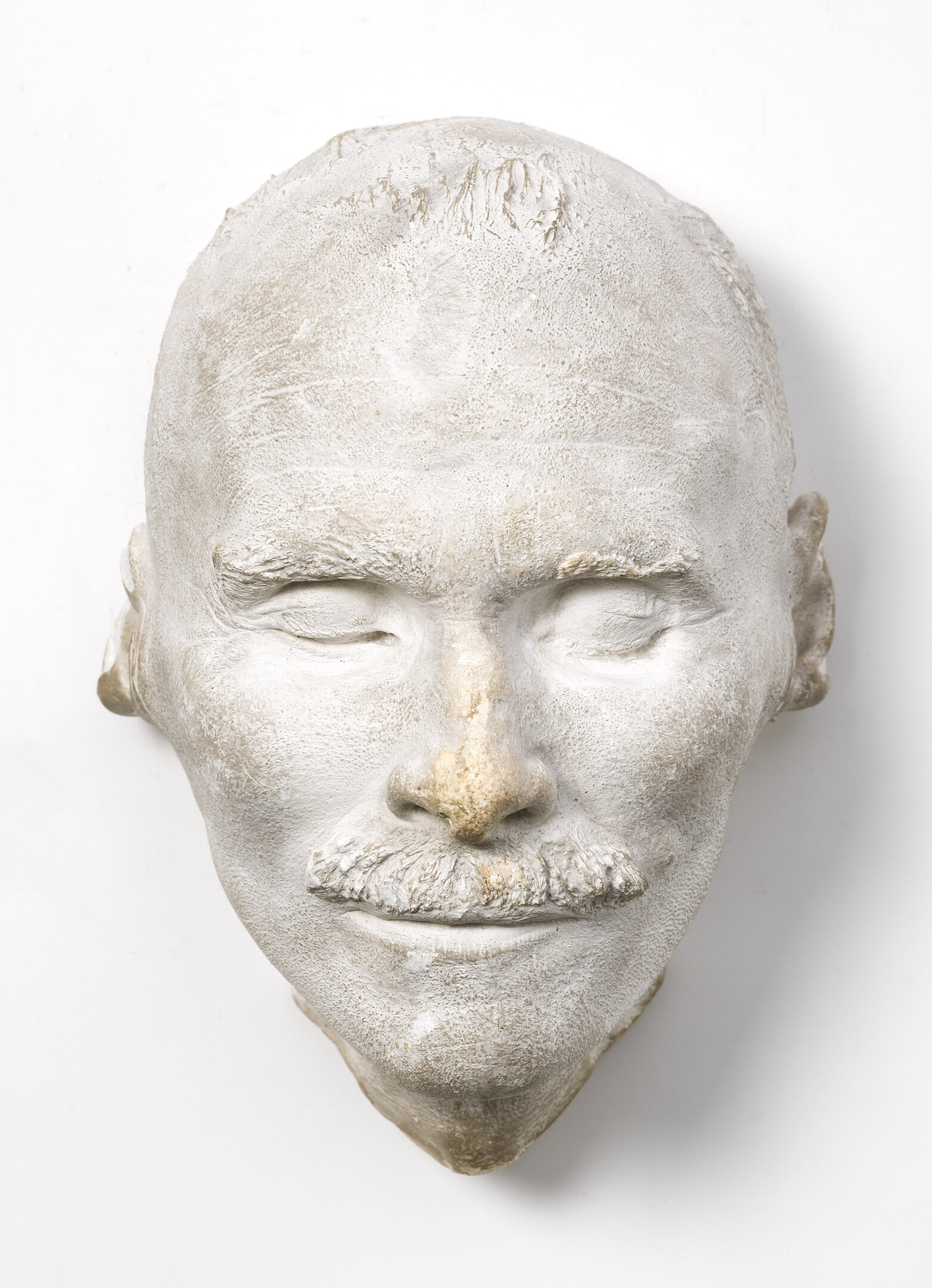

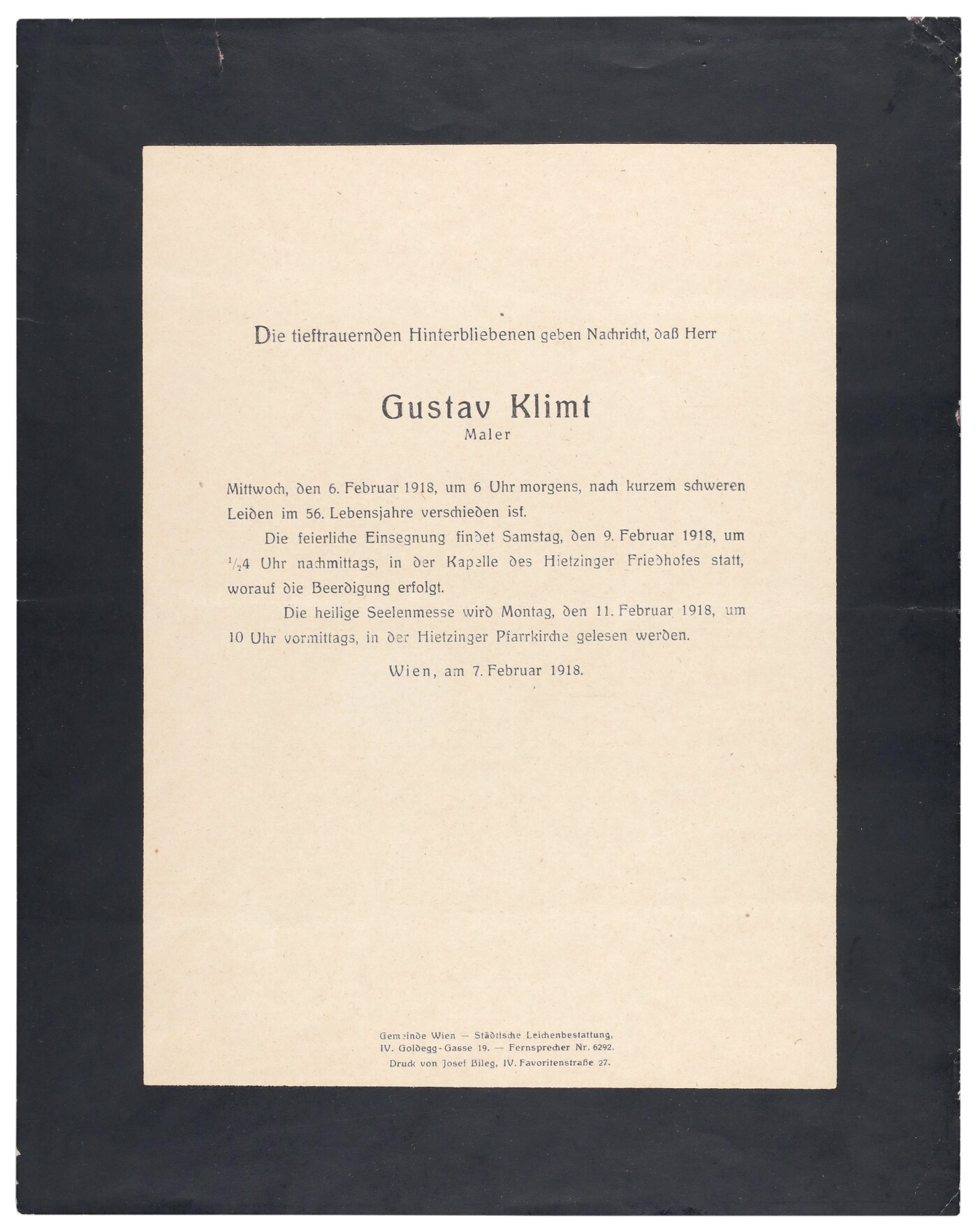

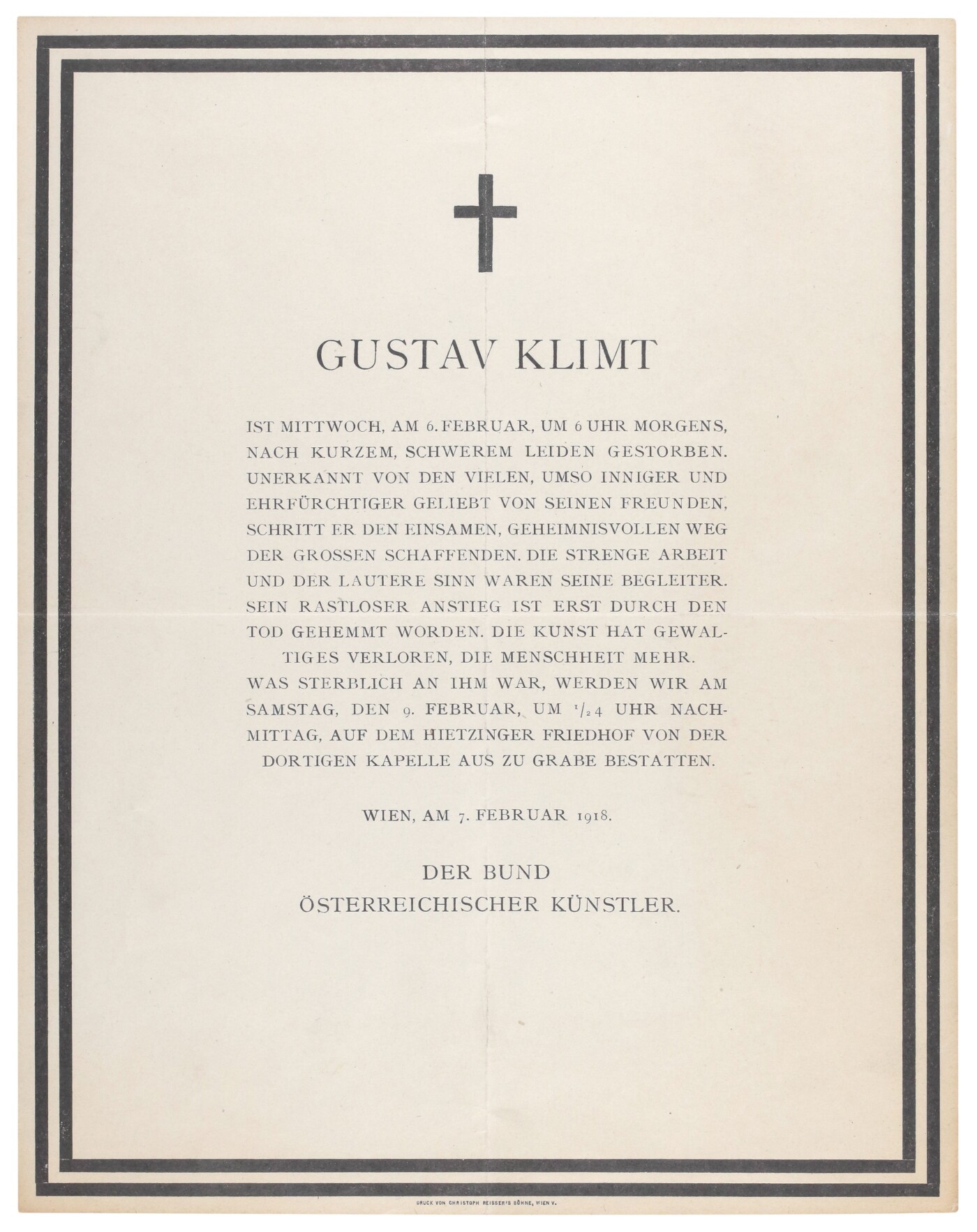

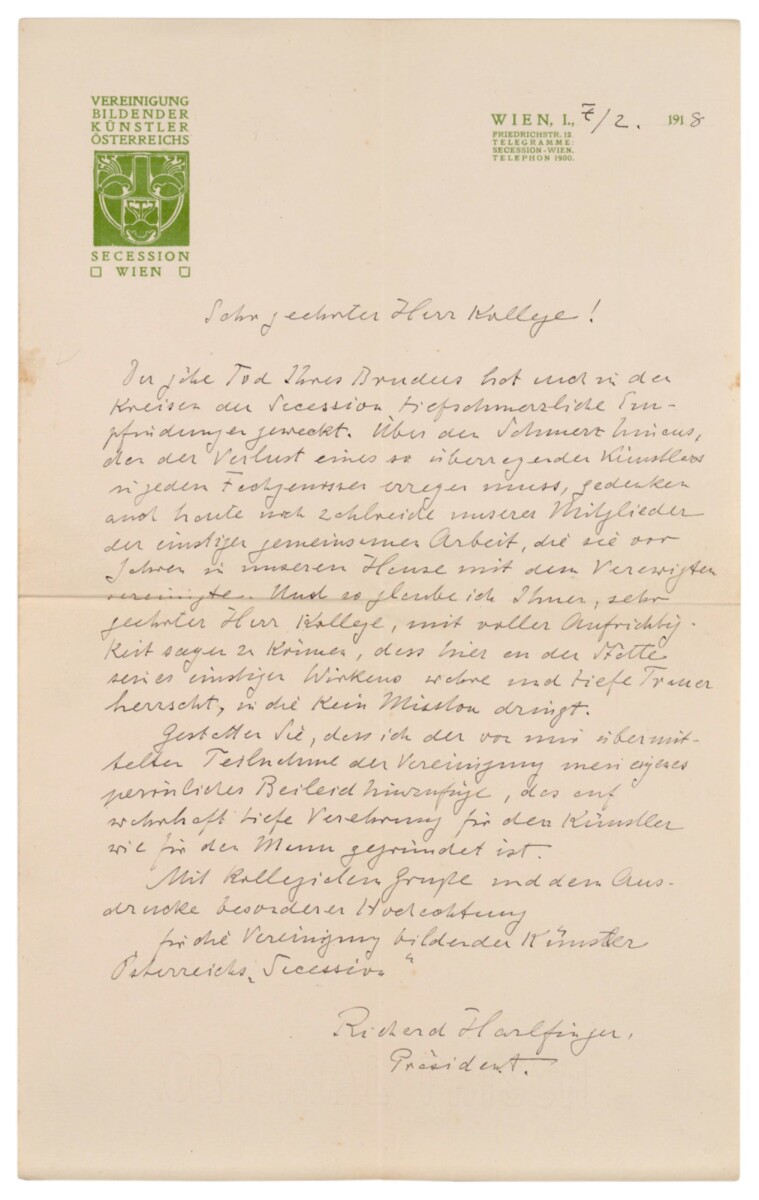

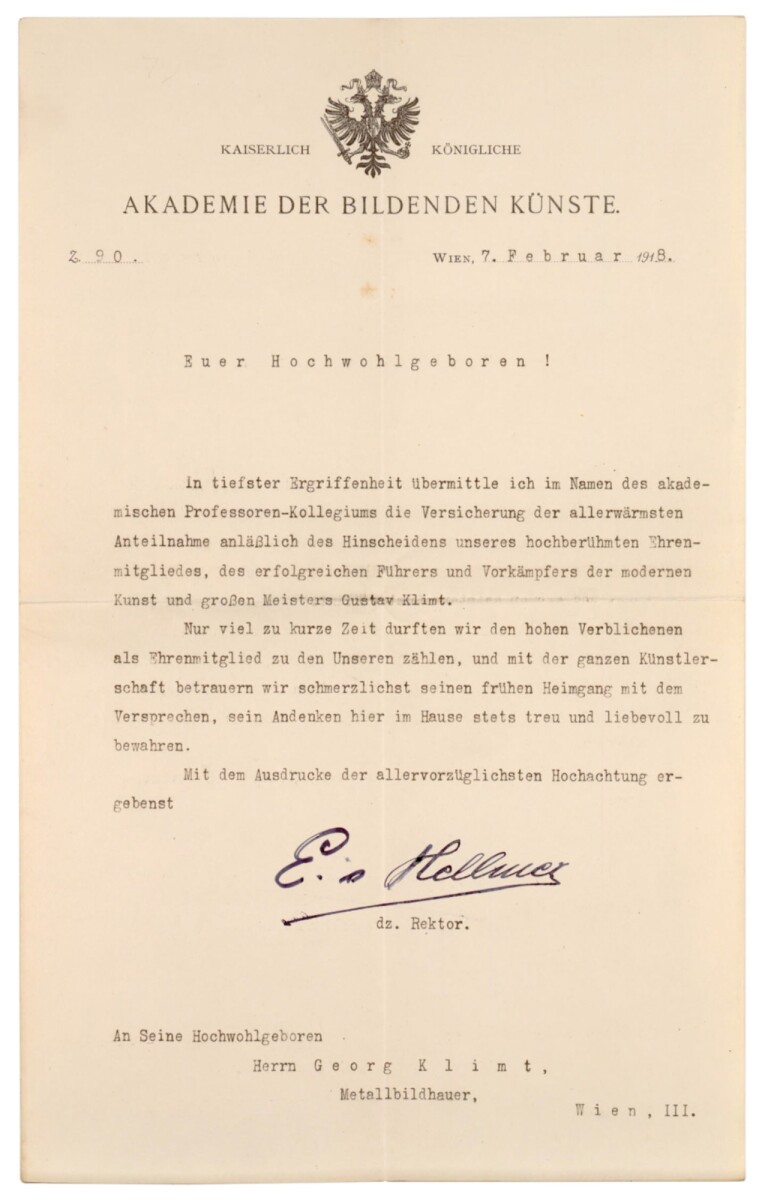

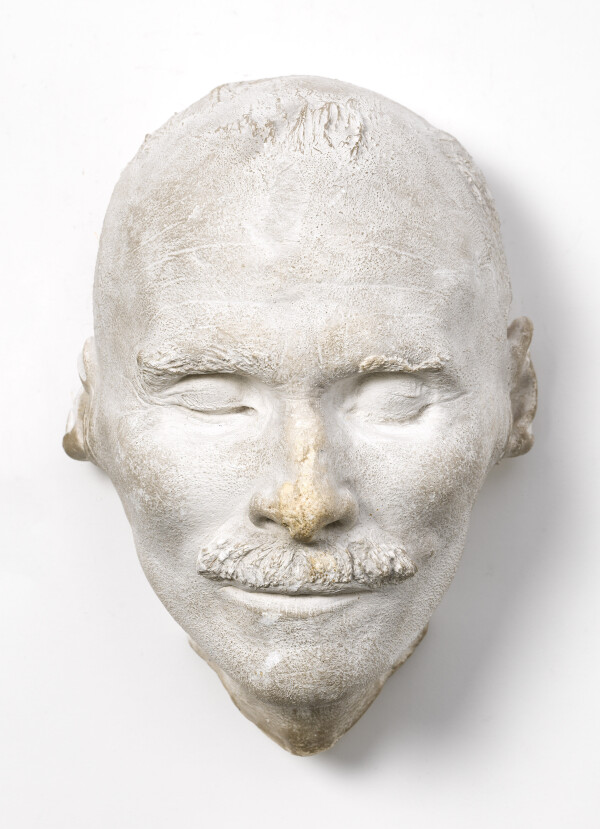

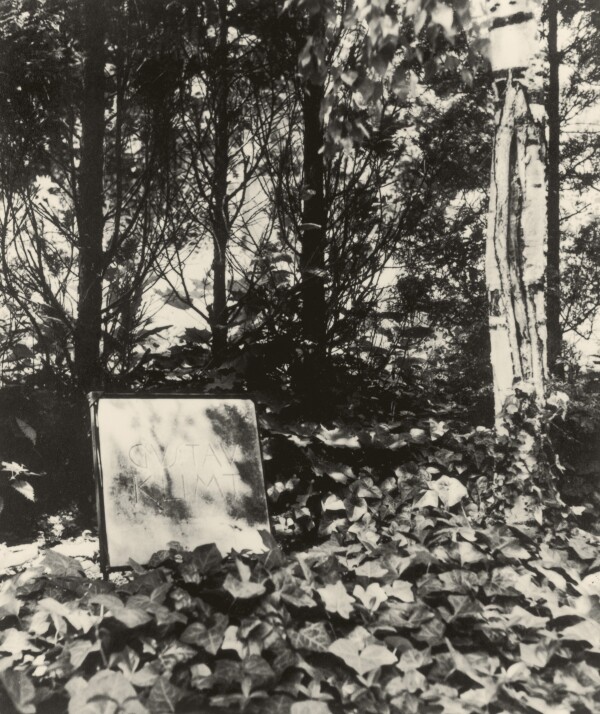

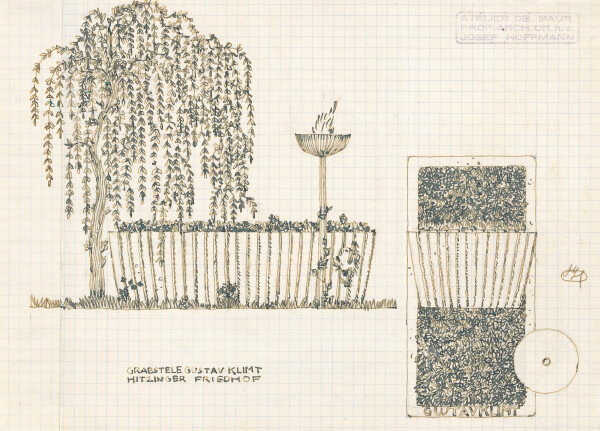

Death of an Artist of the Century

Having suffered a cerebral stroke, Gustav Klimt died at the Vienna General Hospital at the premature age of fifty-five years on 6 February 1918. The funeral ceremony, attended by numerous friends and illustrious personalities from Vienna’s world of art and culture and the political scene, took place three days later at the Hietzing Cemetery.

To the chapter

→

Death mask by Gustav Klimt

© Wien Museum

The Final Years

In the last three years of his life, Gustav Klimt increasingly turned to the female portrait. He celebrated both illustrious personalities and anonymous models with his painterly refinement and Asian motifs. As to the landscapes, the artist drew his inspirations from his stays on the Attersee until 1916, while in his allegories he continued to deal with the theme of Eros and Thanatos.

→

Gustav Klimt: The Bride, 1917/18, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Commissioned Portraits

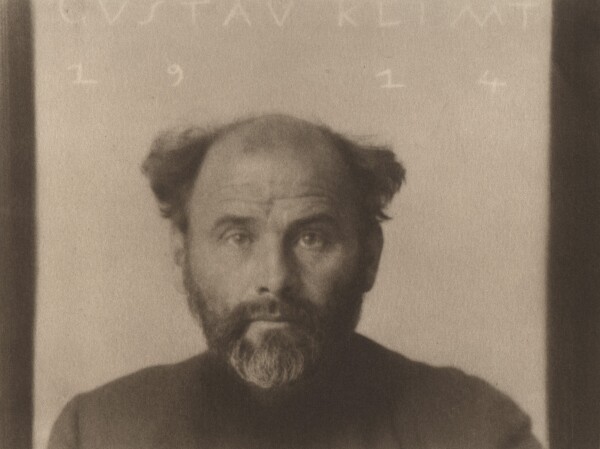

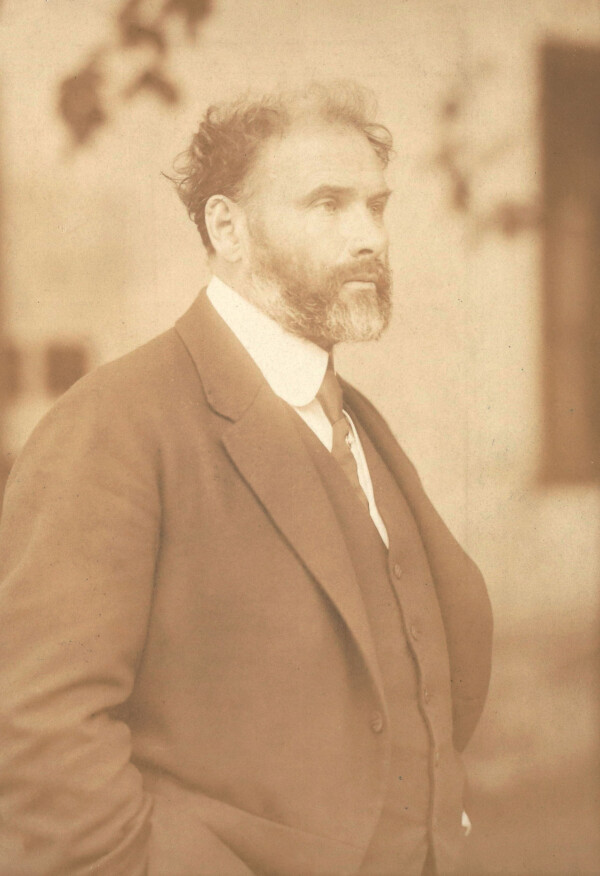

Anton Trčka: Gustav Klimt, 1914, private collection

© Courtesy Galerie Johannes Faber, Vienna

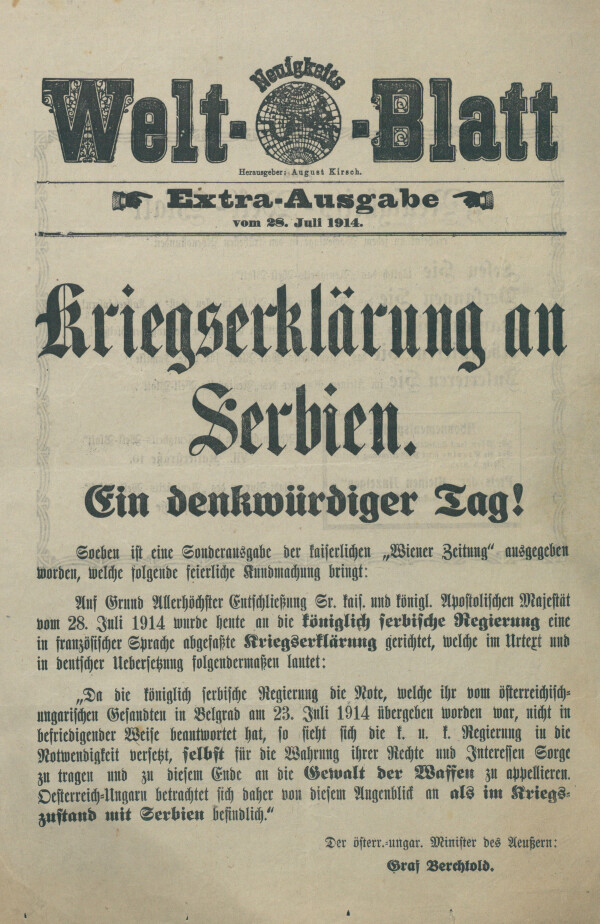

Neuigkeits-Welt-Blatt, 28.07.1914.

© ANNO | Austrian National Library

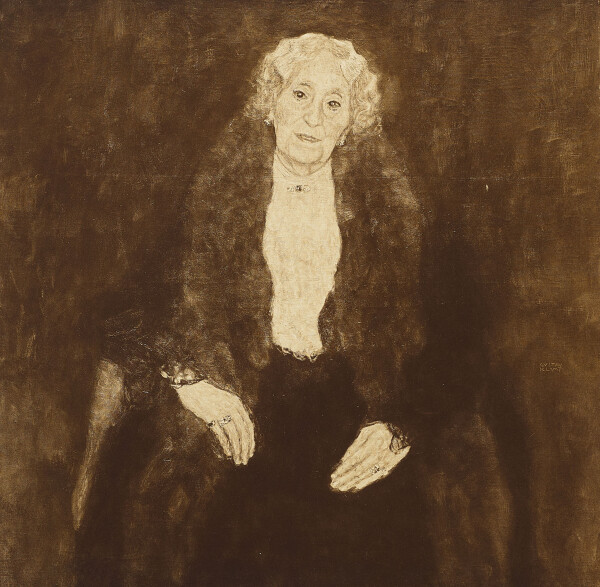

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer, 1916, private collection

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

From the summer of 1914, World War I and the devaluation of money it entailed reduced Klimt’s income significantly. It was presumably for this reason that he increasingly turned to portrait commissions. Stylistically, they stand out for their bright, gaudy colors, modern garments, and Asian motifs.

Gustav Klimt learned about the declaration of war by Austria-Hungary on 28 July 1914 during his summer vacation on the Attersee. In the years to come it would become increasingly difficult even for this internationally famous artist to earn enough money with his work to make a living for himself and his family. For this reason, he increasingly turned to lucrative portrait commissions. A letter to Serena Lederer, in which he asked for an advance for the portrait of her mother, Charlotte Pulitzer, shows his financial plight:

“The painting will be finished by Tuesday or Wednesday – the ‘shabby remainder’ of my fee will be due by then – I’m waiting for it as the devil waits for a poor soul! Merely to spend it again right away. [...] It’s indeed shabby! – Given the hardships of the war, it’s but a poor consolation! [...] Otherwise I would have to draw on my very small ‘gold coin treasure’ – which is saved for times of utmost distress.”

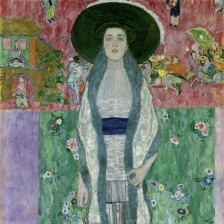

Klimt’s late commissioned portraits can be divided into two groups. On the one hand, he depicted mostly standing ladies wrapped in colorful Wiener Werkstätte fabrics or exotic garments. The background is primarily dominated by Asian motifs, which Klimt borrowed from vases and sculptures he owned or from literature.

On the other hand, Klimt painted depictions of seated women dominated by large, mostly homogeneous expanses of color. Space-annulling, monochrome green backgrounds can be most commonly found in this group.

With the two portraits Adele Bloch-Bauer II (1912, private collection) and Eugenia (Mäda) Primavesi (1913/14, Toyota Municipal Museum of Art), Klimt was to introduce this type of late portraits of women. From 1915 to 1918 he produced two commissioned works dominated by Asian creatures and figures and wild tapestries of bright colors.

Serena Lederer

In 1914, Klimt was commissioned by his friends August and Serena Lederer, who were among his most important patrons and collectors, to paint a portrait of their daughter. It took Klimt more than two years to complete Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer (1914–1916, private collection). The relationship between the painter and the barely 20-year-old girl – whom Klimt had known since her childhood – was so close that Elisabeth called Klimt “uncle.”

The painting belongs to the Asianizing type already discussed. Elisabeth Lederer is the central subject of the picture. Depicted standing, she dominates the narrow vertical format, filling the picture. As in Portrait of Adele Bloch Bauer II, a horizontal line separates the vibrantly colored, contrasting floor from the background, thus locating the depiction in space. Klimt uses decorative elements to divide the composition into geometric shapes. While the pattern on the floor places the sitter within a rectangle, the ornamental carpet in the background inscribes her in a triangular shape. Such a procedure could already be observed in Portrait of Eugenia (Mäda) Primavesi, in which Klimt encloses the sitter within an oval with the aid of a rose bush inspired by the Stoclet Frieze (1905–1911, private collection). The Asian figure groups in the background frame the upper portion of the triangle, but still maintain an orderly distance, emphasizing the sitter’s face through the vacant space thus created. This orderly rhythm of colored flat background and Asian figure groups was soon to develop into a veritable crowd of figures.

In spite of the fact that it is a modern piece, the white dress with its tapering skirt and the transparent chiffon stole recall the portrait of the mother from 1899, in which the sitter is also clothed in pure white. The black hair, dark eyes, and dark eyebrows, creating a strong contrast to the pale complexion, also clearly identify the sitter as Serena Lederer’s daughter. Never satisfied, Klimt, however, apparently did not agree. When he saw the finished portrait in the Lederer family’s apartment, he stated: “Now it’s certainly not her after all!” Elisabeth Lederer recalled the long painting process, which was characterized by numerous reworking sessions:

“Months passed with making drawings of diverse positions. Uncle [Klimt] swore and cursed in a way that made it very entertaining to listen to him. He repeatedly dropped the pencil, exclaiming that one should never paint people with whom one was too close. Then Mama arrived, and an argument started about my pose, toilette, etc. Now and then, their differences became really nasty, and he would yell with his deep, wonderful bass voice: ‘I’ll paint my girl the way I like her. Enough already!’”

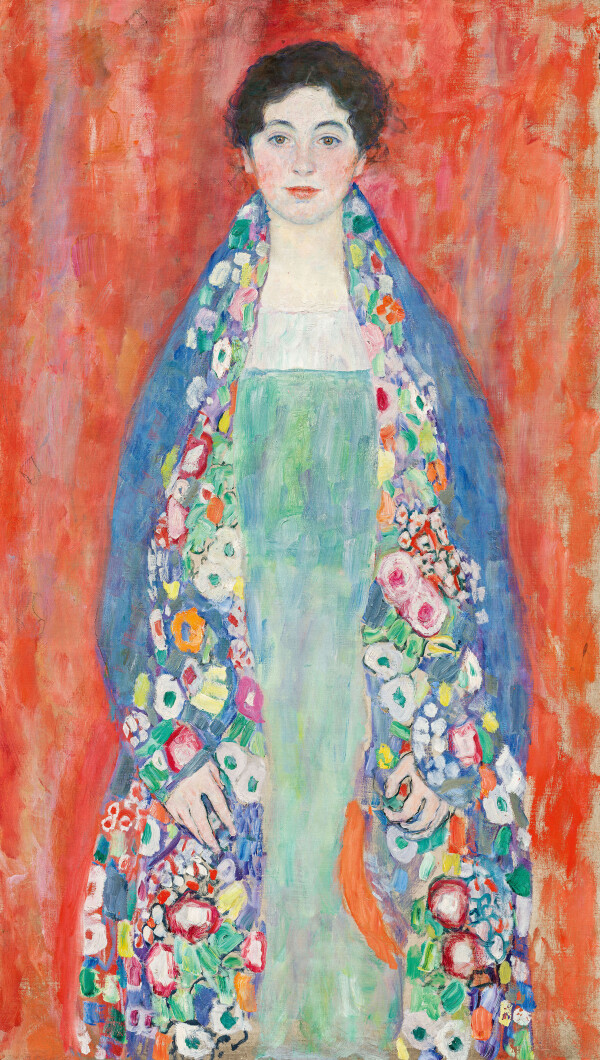

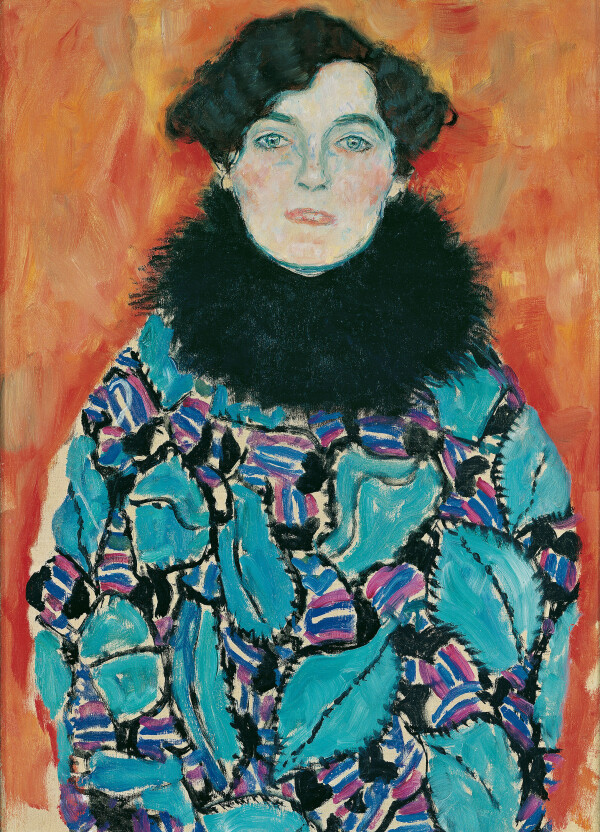

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Friederike Maria Beer, 1916, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, The Mizne-Blumental Collection

© Tel Aviv Museum of Art

Friederike Maria Beer

While in Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer Klimt had used a formal language he had developed in previous years, he now combined well-tried pictorial elements to arrive at a new mode of representation dominated by the rhythm of color and the dissolution of corporeality through ornamentation.

Portrait of Friederike Maria Beer (1916, Museum of Art, Tel Aviv, Mizne-Blumenthal Collection) was commissioned by the painter Hans Böhler, one of Gustav Klimt’s friends. Böhler was romantically involved with the wealthy daughter of the owner of the Kaiserbar (Krugerstraße 3, 1010 Vienna). The comparatively short time of barely four months it took Klimt to finish the portrait – between November 1915 and February 1916 – could, on the one hand, have been due to the fact that Klimt had already tested the composition of the painting in Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer. On the other hand, both the client and the model may have been aware of Klimt’s unwillingness to complete paintings and simply have wrested it from him.

Klimt decided to depict Friederike Maria Beer in a silk dress made of Wiener Werkstätte fabric. The colorful pattern called “Marina” was a design by Dagobert Peche. Originally, the sitter seems to have worn a plain fur jacket over it. It is said, however, that Klimt decided against this visually calming, monochrome element. By turning the jacket inside out, Leo Blonder’s colorfully patterned lining became visible. Whereas Miss Lederer, in her white dress, had still stood out strongly from the rest of the composition, it now appears practically impossible to identify Friederike Maria Beer’s silhouette in her colorfully patterned outfit.

In addition, Klimt modified the design of the background. Whereas previously individual figures populated a monochrome expanse of color, Klimt now enlarged the subsidiary figures in the Asian style, integrating them in a large tapestry of pattern and ornament. Similar to a crowded Crucifixion, the individual figures blur into an ornamental mass structured by a rhythmic sequence of color and form. It seems that the goal of the work, which resembles a crazy quilt, was to prevent any identification of corporeality and outlines. No sooner do you think you have understood a form than the colors begin to flicker, with the shapes dissolving into individual fields of color.

The sitter’s head stands out from the colorful mass of ornaments thanks to the black hair, but it cannot be located with certainty. As if seen through a kaleidoscope, at one time it floats into the foreground, sitting on the sitter’s shoulders, whereas at another time it moves into the background and joins the Asian heads forming a circle around the sitter. The shapes of the background, the Asian figures, and the body of Friederike Maria Beer intersect almost like a mandala. The turquoise ground alone anchors the depiction spatially and manages to steady the viewer’s gaze.

Klimt’s stylistic development manifests itself in the growing ornamentation of his paintings and in an increasing compositional abstraction in favor of interlocking color fields.

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Charlotte Pulitzer, 1917, Verbleib unbekannt

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Barbara Flöge, 1917/18, private collection

© Gallery Welz Salzburg

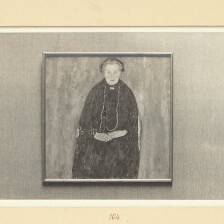

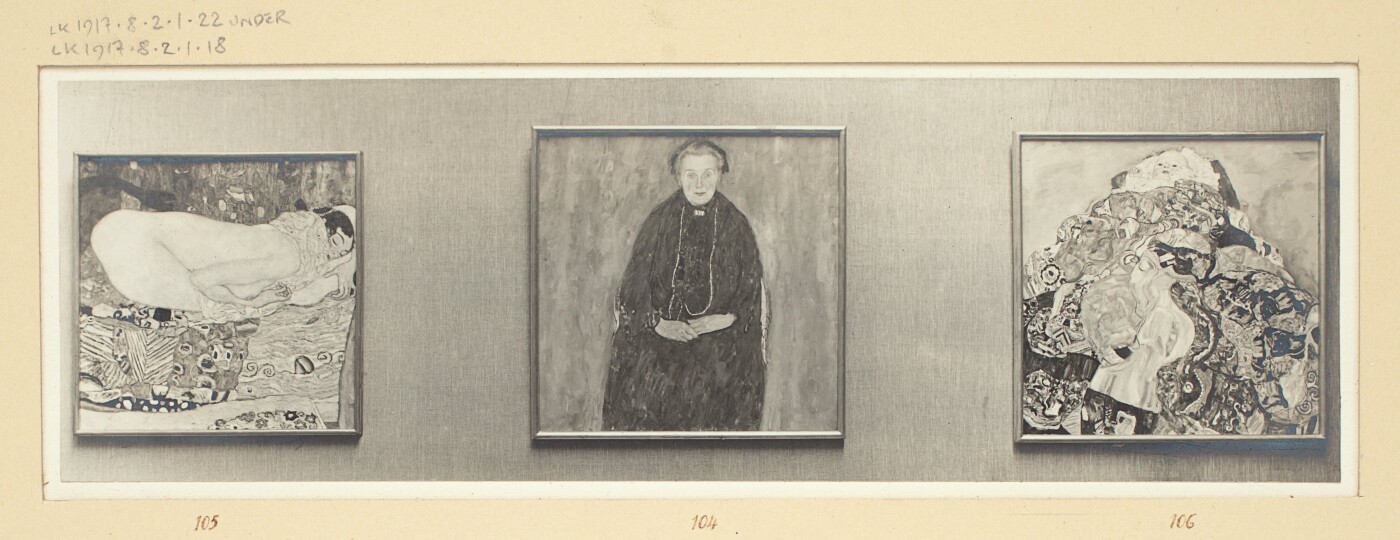

Elderly Ladies and Monochrome Backgrounds

The other type of portrait Klimt would increasingly take to in his later years seems to have been reserved for the depiction of elderly ladies. From 1917 to 1918, Klimt painted two likenesses of seated elderly ladies against monochrome backgrounds. While Portrait of Charlotte Pulitzer (1917, whereabouts unknown, lost since the end of the war in 1945), Serena Lederer’s mother and Elisabeth Lederer’s grandmother, was certainly a paid commission, Portrait of Barbara Flöge (1917/18, private collection), begun at the same time, seems to have been a gift to the Flöge family. Barbara Flöge, affectionately called “Mother” by Klimt, was the biological mother of Helene, his sister-in-law, and her sisters, Emilie and Pauline Flöge.

Both women are depicted frontally and seated. The sitters’ garments lack the colorful patterns of those worn by the younger ladies. Rather, they wear traditional long, black and brown garments, one embellished with a fur collar and the other with a light-colored blouse. The background remains an inanimate, mottled monochrome. In the case of Barbara Flöge, one detects a green tone used more often by Klimt during this period, which can also be found in Baby (1917/18, unfinished, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.) and the revised Portrait of a Woman (Adolescent) (1910, reworked before 1916/17, Galleria d’arte moderna Ricci Oddi, Piacenza). Portrait of Charlotte Pulitzer, which has only survived as a black-and-white reproduction, is said to have shown an equally bluish-green background, according Erich Lederer, to her grandson. Each sitter is integrated in the otherwise two-dimensional picture space through an armchair. Their hands and faces are articulated naturalistically, as was typical of Klimt. The more traditional, calmer rendering of the sitters seems logical, given the fact that in his compositions Klimt always strove to sensitively capture the essence of his models.

That his focus here was primarily on rendering the face and facial expressions marked by life becomes evident from documented changes he made in the picture of Barbara Flöge. On 10 August 1917, he wrote to Emilie Flöge about the genesis of the work:

“I will have to send Mother’s picture as it is now – or not at all – nothing can be done about it as it is.”

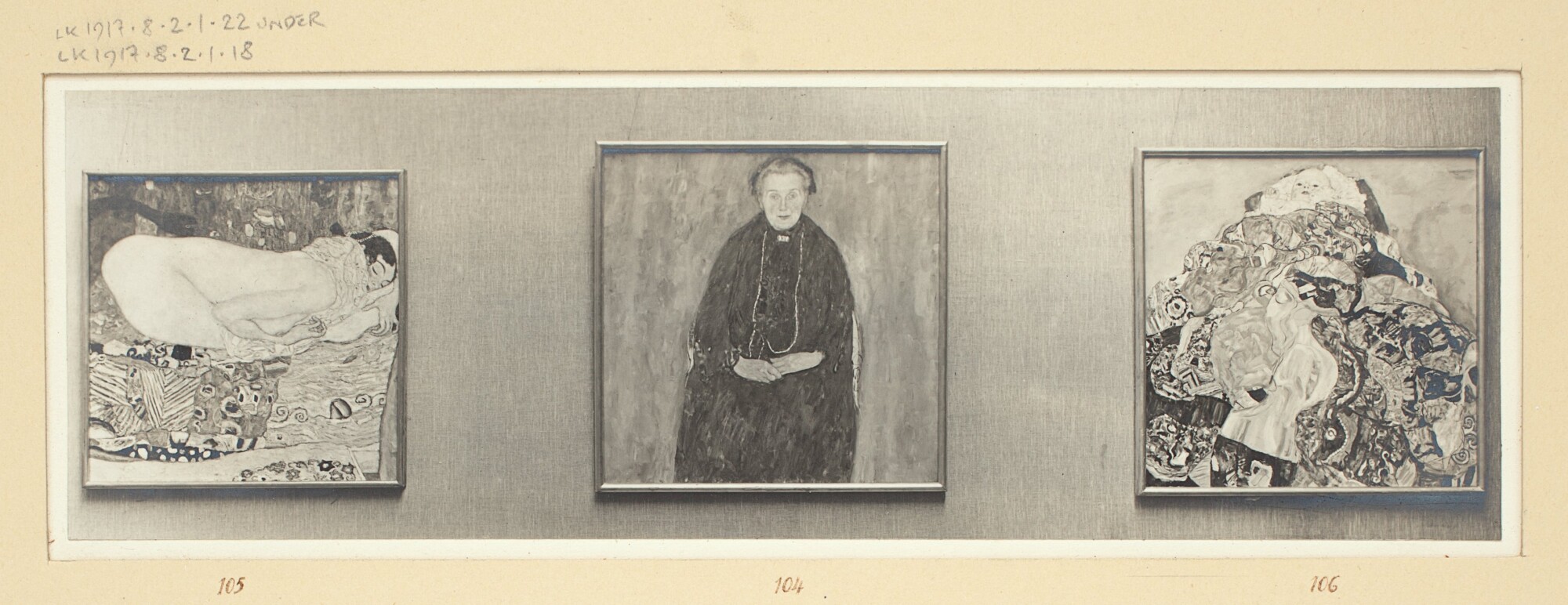

Consequently, the portrait was presented in an unfinished state at an art exhibition in Stockholm. A comparison of photographs from the exhibition with the finished work shows that the principal changes occurred primarily in the sitter’s face, eyes, and lips. In Portrait of Charlotte Pulitzer, the focus is also strongly on the facial area. Due to the muted colors of the background and body, it is mainly the expressively characteristic face that captivates the viewer.

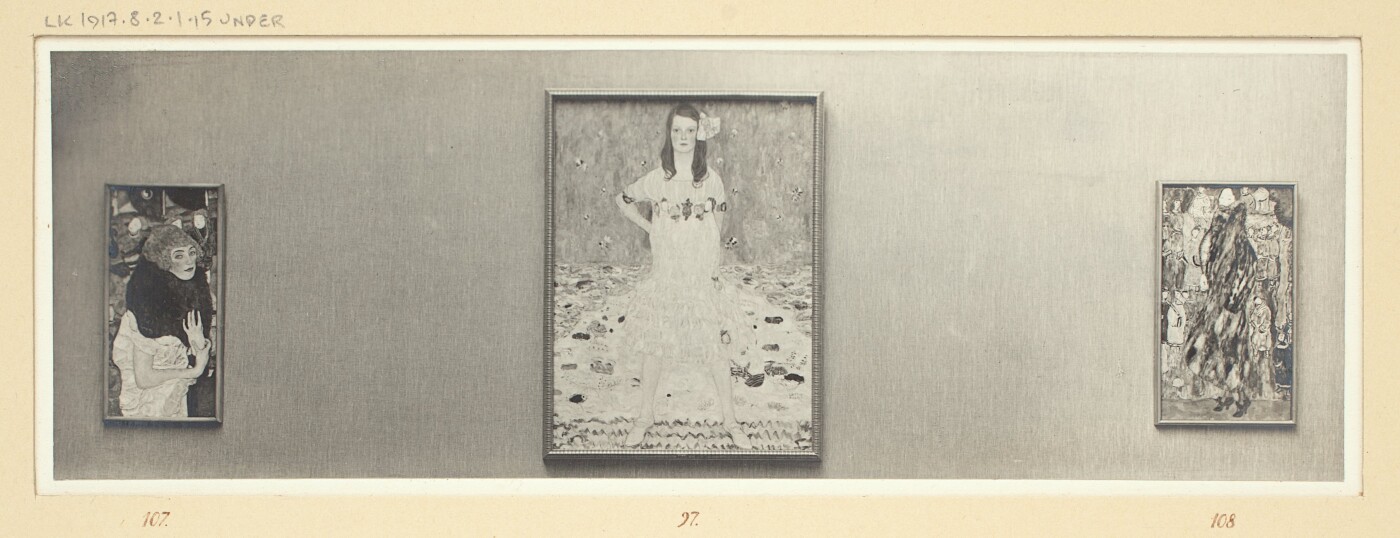

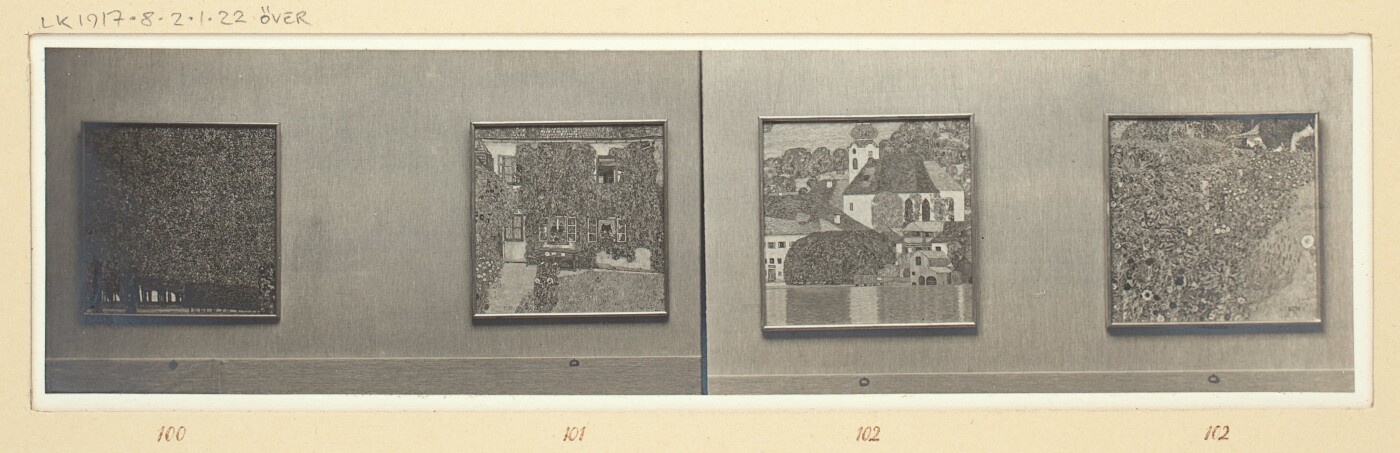

Insight into the Austrian Art Exhibition in Stockholm, September 1917, Archive of Liljevalchs konsthall in The Stockholm City Archive, Sweden

© Archive of Liljevalchs konsthall in The Stockholm City Archive, Sweden

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Miss Lieser, 1917, private collection

© Auktionshaus im Kinsky GmbH, Wien

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Johanna Staude, 1917/18, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Amalie Zuckerkandl, 1917/18, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

Unfinished Commissions

Toward the end of his lifetime, Klimt begun a number of works the master was unable to complete due to his unforeseen death. Thus, numerous portrait commissions remained unfinished. These are difficult to classify stylistically within the late work.

While most of them seem to be in line with the type of portraits of women with monochrome backgrounds, it is not impossible that Klimt still planned to fill them with Asian figures – especially since various studies show that the artist developed his backgrounds mostly without preliminary studies, directly on the canvas.

The painting Portrait of Miss Lieser (1917/18 (unfinished), private collection), rediscovered by the Viennese auction house im Kinsky, presented to the public in January 2024 and auctioned in April 2024, and the Portrait of Johanna Staude (1917/18 (unfinished), Belvedere, Vienna) show formulated faces and heavily patterned, ornamental garments, as already known from the paintings by Elisabeth Lederer and Friederike Maria Beer. In the case of Johanna Staude in particular, the colorful Wiener Werkstätte blouse with a pattern by Martha Alber and the bright orange background seem to indicate that Klimt may have planned to add Asian elements.

The painting Portrait of Miss Lieser was commissioned by a member of the Jewish industrialist family Lieser. It is not entirely certain whether the sitter, who was apparently portrayed in nine sittings, is Helene or Annie Lieser, one of the two daughters of art patron Henriette "Lilly" Lieser, or her niece Margarethe Constance Lieser, daughter of Adolf Lieser. The latest findings point to Helene Lieser, Austria's first female political scientist, who completed her doctorate at the University of Vienna. Lilly Lieser, who was murdered in Auschwitz in 1943, was one of the most important patrons of the arts in Vienna around 1900. Klimt received a total of 10,000 crowns (approx. 8,117 euros) from the patron twice, which presumably only covered the preparatory work. After the master's death, the unfinished work passed into family ownership (Henriette "Lilly" or Adolf Lieser). In addition to the actual sitter, the painting poses further mysteries, as the provenance is considered to be incomplete, especially in the period between 1925 and the 1960s and thus during the Nazi regime.

The contract situation is also surrounded by questions with regard to the Portrait of Johanna Staude. It is known that she worked as a language teacher in 1917 and later on managed Peter Altenberg’s household, so she was not a wealthy lady of society. A letter to Anton Hanak from 1930 provides information about her relationship to Klimt. In it, she refers to the deceased painter as her “splendid friend, understanding confidant, and educator.” It is therefore possible that the work was not a typical commission, but a personal gift.

Another stylistic puzzle is the largely unfinished work Portrait of Amalie Zuckerkandl (1917/18, unfinished, Belvedere, Vienna), which was commissioned by a family of collectors and patrons. Except for the background and the naturalistic head, the work, only rendered as a sketchy underdrawing, is even more difficult to locate in Klimt’s oeuvre than the largely completed paintings for Staude and Lieser. Although surviving preliminary studies document that Klimt had already worked on the painting in 1913/14, the outbreak of World War I stood in the way its execution, for Amalie Zuckerkandl was working as a nurse in her husband Otto’s hospital in Lemberg in 1915/16. However, the preliminary drawing and the first paint layer on canvas must have been largely completed by the end of 1917 at the latest, as Klimt received a total of 4,000 crowns (3,247 euros) for it in November and December.

Although the blue and green background recalls the type of portraits of Barbara Flöge and Charlotte Pulitzer, the blank spots could have been reserved for heads of Asian background figures. Initial color samples on the dress suggest a floral pattern on the stole similar to that in Portrait of Miss Lieser.

Another work from Klimt’s family environment is Portrait of Pauline Flöge on Her Deathbed (1917, presumably destroyed by fire in 1945). Emilie Flöge’s sister had died on 3 July 1917. According to her niece, Helene Donner, Klimt completed the painting, which was meant for the family she had left behind, in just a few hours. Unfortunately, nothing more is known about the color scheme, composition, and layout of the work, which was presumably destroyed by fire in 1945.

Further contents

-

Klimt's Artworks 1904 – 1906 (The Klimt Affair Surrounding the Faculty Paintings)Precious Portraits of Illustrious Ladies

-

Klimt's Artworks 1901 – 1903 (The Golden Knight and Femmes Fatales)Viennese Society Portraits

-

Klimt's Artworks 1910 – 1913 (Expressive Blaze of Colors)Portrayals of Patronesses

Literature and sources

- Alessandra Comini: Gustav Klimt, New York 1975.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band III, 1912–1918, Salzburg 1984.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007.

- Toni Stoos, Christoph Doswald (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Ausst.-Kat., Kunsthaus Zurich (Zurich), 11.09.1992–13.12.1992, Stuttgart 1992.

- Fritz Novotny, Johannes Dobai (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Salzburg 1975.

- Christian M. Nebehay (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Dokumentation, Vienna 1969.

- Tobias Natter: Bildnis Baronin Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt, in: Tobias G. Natter, Gerbert Frodl (Hg.): Klimt und die Frauen, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 20.09.2000–07.01.2001, Cologne 2000, S. 133-134.

- Hansjörg Krug: Gustav Klimt’s Last Notebook, in: Renée Price (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. The Ronald S. Lauder and Serge Sabarsky Collections, Ausst.-Kat., New Gallery New York (New York), 18.10.2007–30.06.2008, Munich 2007, S. 213-231.

- Emily Braun: Empire of Ornament. Klimt’s Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer, in: Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Klimt and the Women of Vienna's Golden Age. 1900–1918, Ausst.-Kat., New Gallery New York (New York), 22.09.2016–16.01.2017, London - New York 2016, S. 56-79.

- Max Eisler: Gustav Klimt, Vienna 1920.

- Edith Krebs: Bildnis Johanna Staude, in: Toni Stoos, Christoph Doswald (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Ausst.-Kat., Kunsthaus Zurich (Zurich), 11.09.1992–13.12.1992, Stuttgart 1992.

- im Kinsky GmbH (Hg.): The Gustav Klimt Sale 24.04.2024, Aukt.-Kat., Vienna 2024.

- Auktionsrekord für Österreich. Klimts "Fräulein Lieser" um 30 Millionen Euro versteigert (24.04.2024). www.derstandard.at/story/3000000217377/klimts-fraeulein-lieser-um-30-millionen-euro-versteigert (04/26/2024).

- Irene Suchy: Lilly Lieser. Die verleumdete Mäzenin (23.04.2024). topos.orf.at/lilly-lieser100 (04/26/2024).

- Olga Kronsteiner: Offene Fragen zu Gustav Klimts "Bildnis Fräulein Lieser (13.04.2024). www.derstandard.at/story/3000000215644/die-vielen-r228tsel-um-fr228ulein-lieser (04/26/2024).

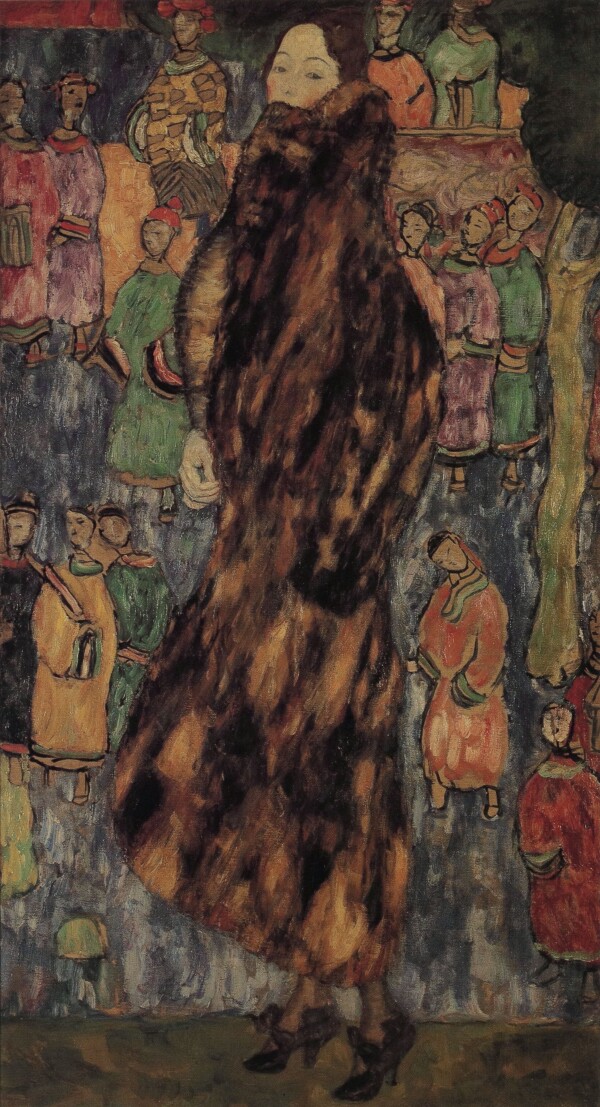

Portraits of Anonymous Ladies

Gustav Klimt: The Polecat Fur, 1916/17, private collection

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Lady with a Muff, 1916/17, private collection

© Gallery Welz Salzburg

Gustav Klimt: The Fur Collar, 1916, vermutlich 1945 verbrannt, in: Max Eisler: Gustav Klimt, Vienna 1920.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

In the last four years of his life, Gustav Klimt painted a series of portraits of anonymous ladies. Their characteristic features are fashionable accessories, Asian backdrops, and the bright colors typical of the artist’s late style. In just under four years, Klimt produced more than ten paintings of sophisticated anonymous women, thus revisiting the type of the “Viennese belle” that had already preoccupied the “Painter of Women” in his early years.

Pictures of Beautiful Viennese Ladies as a Source of Income

It seems that during World War I Klimt produced pictures at the pace of assembly line work. Especially when it comes to his portraits of women, it can be observed that they were painted within a short time and often batchwise. Working according to a scheme and reusing pictorial motifs enabled the artist to come up with a large output for sale. The aesthetics of his late creative years focused on artificially elongated forms and an Asian language of form while harking back to the styles of Mannerism, Primitivism, Orientalism, and Japonism.

It is no coincidence that the artist, who was known as the “Painter of Women,” increasingly turned to the innocuous motif of the “Viennese Belle” during the economically and humanly draining time of World War I, which was wearing people out economically and emotionally. The pleasing motif brought distraction from the horrors of war and therefore certainly enjoyed great popularity. Since Klimt was in a precarious financial situation, it was also in his own interest to produce readily marketable paintings in quick succession. In addition to his commissioned portraits, anonymous portraits of women were a deliberately chosen source of extra income. Collectors in particular acquired them without a specific commission during studio visits.

Ladies with Fashionable Accessories

Most of the portraits of women from Klimt’s last years that were not painted in the context of a portrait commission show busts of beautiful Viennese ladies in square format. They can roughly be divided into two groups. On the one hand, in the representations of his sitters Klimt concentrated on veiling them. The Polecat Fur (1916/17, unfinished, private collection), Lady with a Muff (1916/17, private collection), and The Fur Collar (c. 1916, presumably destroyed by fire in 1945) present women whose bodies are concealed by heavy clothing and scarves. This can similarly be assumed for the unknown work referred to as “The Veil.” Its existence, however, is only known from what has been passed down by contemporaries. However, we learn nothing about the actual appearance or subject matter of the painting, except for the garment that gives the picture its title. What made this type of composition so attractive for the artist probably lied in the mystical secrecy of these women. This is what one critic thought about Klimt’s ladies:

“They are women of a mystical nature and yet of a sensuous elementary force. Secrets slumber in their souls, as do demonic powers.”

Voluminous and mostly dark clothes not only conceal the skin and facial features, but also negate the women’s corporeality. The result is a realistically portrayed head resting on a loosely brushed expanse of color that is abstract pictorial space rather than garment. In the first monograph on Gustav Klimt published in 1920, Max Eisler aptly commented upon the development of female images in Klimt’s work:

“Or a mature girl, a young woman appears within the upright format of these cropped views. A veil, a muff, or a fur collar may lend these studies their names, constituting the eponymous motif. This could also frequently be encountered in the early work. But how much the attitude has changed! How light, how liberal, how painterly it all has become!”

The backgrounds are enlivened by Asian figures that crowd together to form a carpet of dense patterns. Something similar could already be observed in Klimt’s commissioned portraits from around 1916/17. Thus, in Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer (1914–1916, private collection) and Portrait of Friederike Maria Beer (1916, Tel Aviv Museum of Art), one finds the same figurines inspired by Chinese and Korean art objects. For stylistic reasons, therefore, the unknown portraits of ladies are therefore dated to 1916 and 1917. Unfortunately, little is known about the genesis of these portraits. All three works, The Polecat Fur, Lady with a Muff, and The Fur Collar, were part of the estate exhibition at Gustav Nebehay’s gallery in 1919 and may therefore still have been present in the artist’s studio at the time of Klimt’s death.

The Fate of Anonymous Ladies

The painting Lady with a Muff, however, poses some riddles. The correspondence with the lenders of a Klimt exhibition at the Neue Galerie Wien in 1926 indicates that the owner of the painting was Dr. Richard Aschner. Although it is within the realms of possibility that the latter had acquired the work in the course of the estate exhibition, several things seem to suggest that the picture may not represent an unknown person, but is indeed to be seen as a commissioned portrait.

At the time the portrait was painted in 1917, industrialist Richard Aschner had just become engaged to Alice Zimbler and married her in March of the following year. The portrait could therefore have been an engagement present for Alice, similar to Portrait of Margarethe Stonborough-Wittgenstein (1905, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Neue Pinakothek, Munich). At the same time, around 1916/17, Richard Aschner’s brother Emil became engaged to Alice “Lilly” Fenichel. When comparing photographs of Alice “Lilly” Aschner with the woman in Lady with a Muff, the similarity of the facial features is striking. Again, this could have been an engagement gift. Since Lilly Aschner died in an accident in Prague before 1926, the painting would consequently have passed into the possession of the rest of the family, including Richard Aschner. Moreover, a portrait commission would explain why the Aschner family also owned sketches for the work.

Whether Lady with a Muff actually depicts one of the two women named Alice Aschner and was therefore a commissioned portrait or whether it was simply a purchase made at a later date from the artist’s estate cannot be proven with certainty. What is certain, however, is that the Aschners, a Jewish family, owned the painting. They probably still did in the 1940s, when they were forced to escape to Prague because of their Jewish origins, and from where they were deported to a concentration camp and murdered. The work, long believed to be lost, was last shown at the National Gallery in Prague.

The Fur Collar, the whereabouts of which have also remained in the dark until now, was probably destroyed by fire in the café of its last owner, the hotelier and coffeehouse owner Josef Siller. Siller had probably purchased the painting from Galerie Neumann in 1931. In any case, it is known to have been in his possession from 1935 on. The Hotel and Café Siller on Franz-Josefs-Kai was severely damaged in an air raid on 11 April 1945, and Siller’s entire art collection stored there was destroyed. Presumably, The Fur Collar had also been kept there at that time. The painting is therefore merely known in black and white. Only an exhibition title in Swedish from the catalog of the Stockholm exhibition in 1917 reveals something about the colors. There the work is described as “Blondin,” i.e. as showing a blonde. The lady may therefore have been one of the rare depictions of fair-haired women in Klimt’s oeuvre, for the artist preferred dark and red-haired ladies.

Gustav Klimt: Lady with a Fan, 1917/18, private collection

© Belvedere, Vienna

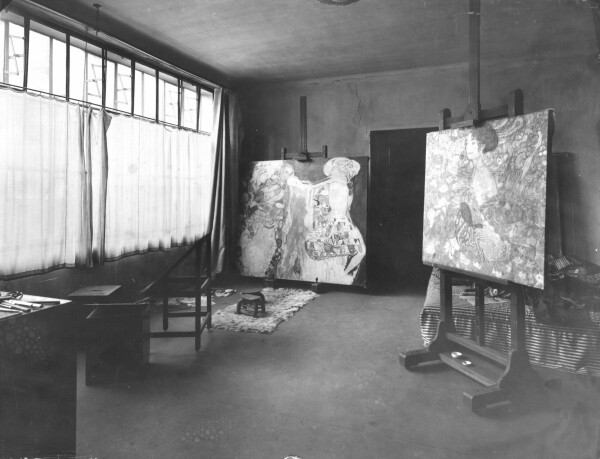

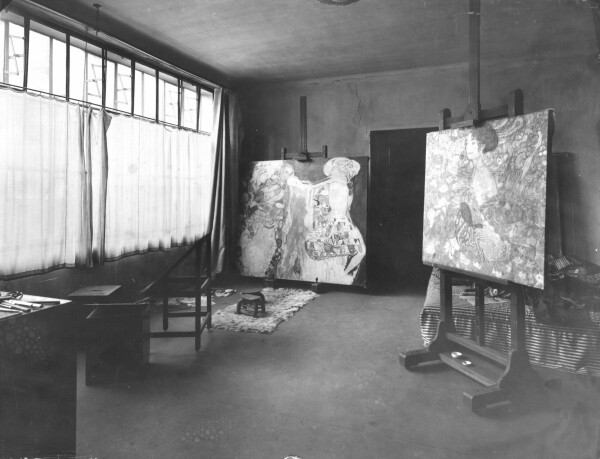

Moriz Nähr: Gustav Klimt's workshop in Feldmühlgasse, presumably 1917, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Swan’s Necks and Kimonos

In stark contrast to the mystically enwrapped depictions of women are those portraits of ladies by Klimt that show women with bare shoulders and elegantly elongated necks, usually rendered in three-quarter profile. In this series, Klimt combines the type of the “Viennese Belle” with exotic beauty. His models wear swept-up coiffures, turbans, kimonos, and other garments featuring oriental patterns. Here Klimt subscribed to the phase of Japonism and Orientalism, as had the Impressionists and Fauvists in France before him. The painting Lady with a Fan (1917/18, unfinished, private collection) marks a transition between the veiled ladies wearing stylish accessories as their attributes and the Viennese ladies depicted as exotic beauties. The long neck – reminiscent of contemporary depictions of women by Amedeo Modigliani – and the exceptionally low-cut kimono allow Klimt to show large areas of bare skin. The wildly patterned garment, on the other hand, causes any corporeality to be swallowed by the flatness of the picture plane. Despite the fact that the sitter is shown down to her hips, one is almost tempted to call the depiction a bust. As in the paintings featuring furs and veils, the fan serves as a guardian of illusionism and as an element of hidden eroticism. Klimt has strategically placed the pink fan where the lady’s naked breasts would be seen. The background is once again rendered in a bright, monochrome tone, different from The Fur Collar, Lady with a Muff, or the commissioned portraits from the same period. However, the picture is not populated by small-sized figures. Although the pictorial language remains Asian, Klimt draws on motifs from flora and fauna. Whereas in the previous paintings the Asian figures still crowd in a mass of color and ornament, the artist has distributed here the phoenix, black crowned crane, golden pheasant, and lotus blossoms over the surface in a quiet pattern reminiscent of wallpaper. The birds’ long necks further emphasize the protagonist’s unnaturally elongated neck.

Although the work is not a commissioned portrait, it is known from autograph documents that Klimt painted it for a particular client. On 10 July 1917 he asked the buyer Erwin Böhler for patience:

“What is coming now is entirely shameful! I wanted to be finished with the picture by 15 July. – I underestimated the work [...]. The major part of the picture has been painted by now – maybe you are eager to take a look at the picture – it will certainly be finished by September.”

He also asked Erwin Böhler for an advance of 10,000 crowns (approx. 8,370 euros). Due to World War I Klimt was in a financial predicament. Advance payments of this kind were therefore not uncommon. However, Böhler was unable to collect the painting before Klimt’s death. A photograph by Moriz Nähr proves that it was still on the easel in the artist’s studio in 1918, together with The Bride.

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Wally, 1916, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Martin Gerlach: Insight into the apartment of Serena and August Lederer, 1920s - 1930s, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Gustav Klimt: Friends II, 1916/17, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt, in: Max Eisler (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Eine Nachlese, Vienna 1931.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Two more portraits of ladies follow the type of beautiful women in oriental robes described above. Portrait of Wally (1916, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945) shows a composition similar to that of Lady with a Fan. The hair is pinned up, the neck elongated, and the kimono-like garment falls over the shoulders. Without a fan to cover her body, Wally’s bare breast is exposed. Since the work has only survived in a black-and-white illustration, there is little evidence of its colors. A description from 1943 mentions a “terra-cotta red with dark figures.” Although Klimt again draws on Asian figures and artifacts here rather than floral patterns, the crowded configurations in the background are absent. Sporadically employed figurines are arranged around the sitter at some distance. The resulting vacant space gives the impression of the sitter being framed. Formally, this solution corresponds to the portrait Elisabeth Lederer. Although the title of the work refers to a specific person, it does not allow us to identify the sitter. It has repeatedly been assumed that it was Egon Schiele’s model and lover, Wally Neuzil, but there is no evidence for this.

The painting was not exhibited during the artist’s lifetime, yet it enjoyed great popularity among Klimt’s collectors. Apparently, Serena Lederer had already expressed interest in the portrait when the artist was still alive, after a visit to his studio, and had more or less reserved it for herself in advance. According to Serena’s son, Erich Lederer, the art historian Othmar Fritsch also wished to acquire the painting. He had seen it at the studio when he bought Schönbrunn Landscape (1916, private collection). As Klimt could not sell it to him, Fritsch is said to have commissioned a similar painting from him. The result was probably Friends II (1916/17, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945). After Klimt’s death, Eugenia Primavesi also attempted to bring Portrait of Wally into her possession. Like the other two buyers, she had encountered it during a visit to the artist’s studio. On 6 February 1918, the day of Klimt’s death, she wrote to Anton Hanak about it:

“Frau Lederer [note: Serena Lederer] need not be considered for sure, for indeed the female portrait has not yet belonged to her.”

In the end, however, it was August and Serena Lederer who succeeded in acquiring the work from Klimt’s estate. Unfortunately, it burned with the rest of the Lederer Collection at Immendorf Castle in 1945. Like Lady with a Fan, the painting Friends II may not have been a portrait commission, but it was created at a buyer’s explicit request. Although Othmar Fritsch wished to purchase a painting that resembled Portrait of Wally, the composition of Friends II differs in several essential aspects from that of the single portrait.

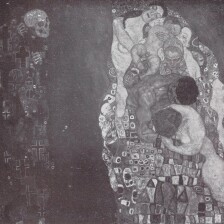

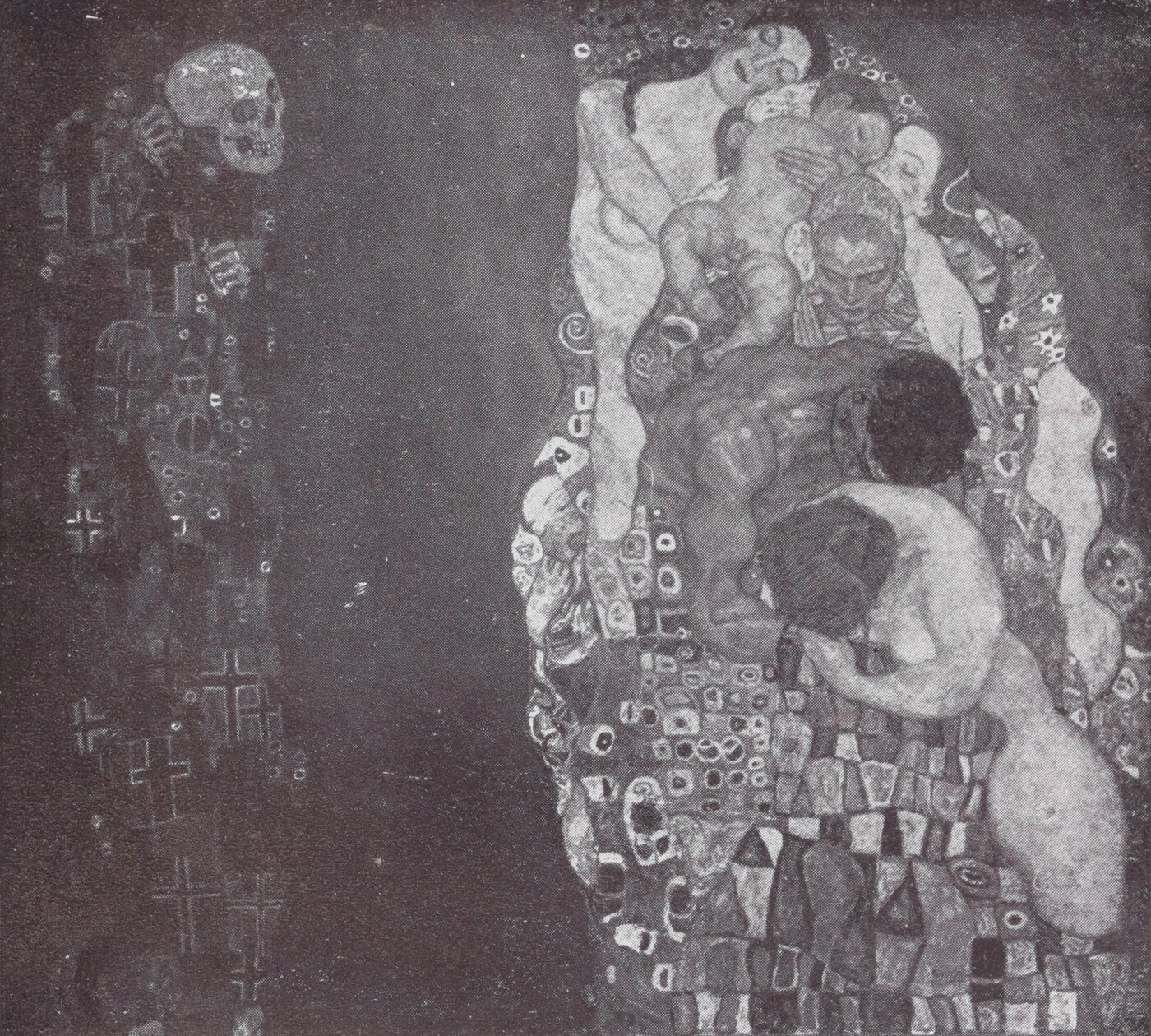

With this painting, Gustav Klimt revisited a motif that had already preoccupied him since the Golden Period: the intimate, homoerotically charged atmosphere between two women. Whereas he had otherwise painted mainly single portraits of young ladies, Klimt now resorted to the type of a double portrait for his anonymous women for the first time in his late phase, using the two figures to bring out contrasts. While one of the protagonists wears a turban and a sweeping orange-red reform dress or kimono, her friend is completely unclothed except for a vibrantly patterned shawl over her shoulder. Again, what is particularly striking is the long, curved neck of the lady in orange, resembling that of a swan and vividly juxtaposed with the veiled short neck of the figure in the nude. The friend on the left is a motif Klimt also used in Death and Life (Death and Love) (1910/11, reworked: 1912/13 and 1916/17, Leopold Museum, Vienna). Presumably, the two figures are based on the same sketch or series of studies. As in the other two portraits, the background is enriched with East Asian motifs – birds and floral motifs loosely spread across the garish pink background. Thus the composition is more related to Lady with a Fan than to Portrait of Wally.

Gustav Klimt: The Dancer (Ria Munk II), circa 1916/17, private collection

© Fine Art Images / Heritage Images

Portrait of a Lady or Portrait Commission?

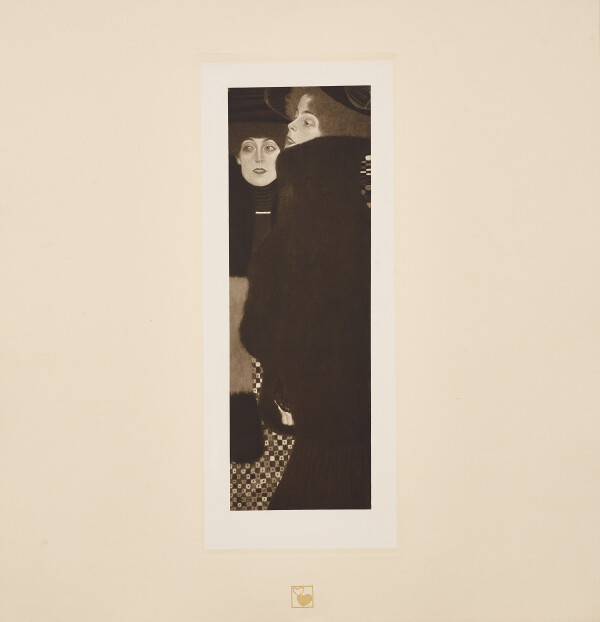

In addition to the square-format portraits depicting the sitters as busts or three-quarter-length figures, Klimt’s output from around 1916/17 also includes two portraits of a narrow vertical format depicting full-length-figures of ladies. As to their composition, both The Dancer (Ria Munk?) (c. 1916/17, private collection) and Portrait of a Lady (Ria Munk?) (1917, unfinished, The Lewis Collection) follow Klimt’s commissioned portraits rather than his anonymous portraits of ladies. The standing figures are draped in colorfully patterned robes. In their upright posture, they almost resemble columns. They are embedded in a background pattern of wild colors and shapes combining to form a veritably two-dimensional ornamental carpet.

This similarity to commissioned portraits repeatedly led researchers to see in the paintings works creatd in the context of a commissioned portrait of the late Ria Munk. According to Erich Lederer, Klimt had worked for years on a posthumous portrait of his deceased cousin, but to no avail. It is assumed that the completed picture entitled The Dancer could be a revised version of a portrait of Ria Munk (concrete forensic investigation is still pending), while the unfinished Portrait of a Lady (Ria Munk?) is considered a third version of the same subject. It is thus probably not a portrait of an unknown lady, but an unfinished commissioned portrait showing Ria Munk.

Portrait of a Lady (Ria Munk?) perfectly fits in with the commissioned portraits of the late period. The upright position, the dissolution of the sitter’s corporeality through a straight-cut, patterned robe, and the garish background embellished with Asian ornaments are reminiscent of such works as Portrait of Margarethe Constance Lieser (1917, unfinished, whereabouts unknown) and Portrait of Friederike Maria Beer. In The Dancer, however, Klimt used a new compositional solution. For the first time since Portrait of a Woman (c. 1893/94, private collection), which was painted in the early 1890s, the background is not an abstract expanse of color or ornamentally patterned carpet, but shows an interior. Whereas the space in Portrait of a Woman was still rendered naturalistically, Klimt now deliberately questions perspective. In a complex spatial structure, pictorial elements flip from horizontal to vertical and vice versa. Such objects as the bouquet of flowers optically move from foreground to background, challenging the viewer’s eye. Klimt had already used a similar oscillation of spatial planes in Portrait of Friederike Maria Beer. The ambivalent perspective of the spatial solution is reminiscent of works by Henri Matisse.

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of a Lady en face, 1917/18, Lentos Kunstmuseum Linz

© LENTOS Kunstmuseum Linz

Unfinished Ladies’ Portraits

Two unfinished portraits of ladies from the artist’s estate make the group of depictions of women from 1917 complete: Portrait of a Lady in White (1917/18, unfinished, Belvedere, Vienna) and Portrait of a Lady en face (1917/18, unfinished, Lentos Kunstmuseum Linz). Both works were in Klimt’s studio after his death in February 1918 and therefore bear estate stamps on their reverse sides. That they have come down to us in such a sketchy condition makes it difficult to judge them. Formally, however, the two paintings are reminiscent of Portrait of Charlotte Pulitzer (1917, whereabouts unknown, lost since the end of World War II in 1945) and Portrait of Barbara Flöge (1917/18, private collection). Both of these commissioned portraits show ladies viewed from relatively close up against neutral, mottled monochrome backgrounds. While in the case of Portrait of a Lady in White it can be assumed that Klimt had not intended to integrate Asian art objects in the background, this cannot be ruled out in view of the sketchy execution of Portrait of a Lady en face. The two women’s pale, almost whitish blue complexion is remarkable, but it is possible that this was only a first version that Klimt would have reworked. With its dotted patterns, the protagonist’s impressionistically blurred garment in Portrait of a Lady in White is stylistically reminiscent of the overpainting of Portrait of a Woman (Adolescent) (1910, reworked before 1916/17, Galleria d’arte moderna Ricci Oddi, Piacenza). Again, Klimt draped the sitter in a kimono-like loose robe with a dotted pattern. The background shows a monochrome expanse in dark green. Thus, Klimt had adapted the painting created almost a decade earlier to his most modern painting style.

Further contents

-

Klimt's Artworks 1901 – 1903 (The Golden Knight and Femmes Fatales)Viennese Society Portraits

-

Klimt's Artworks 1904 – 1906 (The Klimt Affair Surrounding the Faculty Paintings)Precious Portraits of Illustrious Ladies

-

Klimt's Artworks 1910 – 1913 (Expressive Blaze of Colors)Portrayals of Patronesses

Literature and sources

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007.

- Sophie Lillie: Was einmal war. Handbuch der enteigneten Kunstsammlungen Wiens, Vienna 2003.

- Tobias G. Natter, Gerbert Frodl (Hg.): Klimt und die Frauen, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 20.09.2000–07.01.2001, Cologne 2000.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band IV, 1878–1918, Salzburg 1989.

- Fritz Novotny, Johannes Dobai (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Salzburg 1975.

- Gerbert Frodl: Damenbildnis in Weiß, in: Gustav Klimt in der Österreichischen Galerie Belvedere in Wien, Salzburg 1992, S. 62.

- Max Eisler: Gustav Klimt, Vienna 1920.

- Curt Glaser: Berliner Ausstellungen, in: Kunstchronik. Wochenschrift für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, N.F., 27. Jg., Heft 19 (1915/16), Spalte 190.

- Auktionshaus Albert Kende (Hg.): 110. Kunstauktion. Nachlässe: Jacques E. Strauss, Wien, Industrieller E. T., Wien, Dr. A. E., Wien, Fr. Sch., Wien und Wiener Patrizierbesit, Aukt.-Kat., Vienna 1931.

- Führungszeugnis Alice Aschnerová, 15.7.1939, Inv.-Nr.: A 522/38.

- Führungszeugnis Emil Aschnera, 15.7.1939, Inv.-Nr.: A 522/39.

- Führungszeugnis Emil Aschnera, 17.4.1939, Inv.-Nr.: A 577/8.

- Empfangsbestätigung für Richard Aschner, 23. Ausstellung Gustav Klimt (Neue Galerie) (07/03/1926). Dokumentation 384/2, .

- Brief von Gustav Klimt in Wien an Erwin Böhler, DLSTPW11 (10.07.1917), .

- Brief von Eugenia „Mäda“ Primavesi sen. in Winkelsdorf an Anton Hanak (02/06/1918). Mappe 17.

- Brief von Gustav Klimt an Dr. Othmar Fritsch (05/22/1917).

- Neues Wiener Journal, 08.02.1919, S. 5.

- Kunstchronik und Kunstmarkt. Wochenschrift für Kenner und Sammler, 54. Jg., Nummer 30 (1919), S. 19.

- Neue Freie Presse, 10.10.1917, S. 8.

- Neue Freie Presse, 24.03.1918, S. 11.

- Neue Freie Presse, 20.10.1926, S. 14.

- Wiener Zeitung, 21.09.1948, S. 3.

- Wiener Woche. Sport und Salon, 1. Jg., Nummer 5 (1919), S. 4.

- Alessandra Comini: Gustav Klimt, New York 1975.

- N. N.: Die Kaiser-Franz-Josef-Ausstellung, in: Österreichische Kunst, 6. Jg., Heft 6 (1935), S. 11-13.

- Marian Bisanz-Prakken: Ria Munk III von Gustav Klimt. Ein posthumes Bildnis neu betrachtet, in: Parnass, 29. Jg., Heft 3 (2009), S. 54-59.

Late Allegories

Gustav Klimt: Leda, 1917, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Crouching half nude to the right, 1913/14, Leopold Museum

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

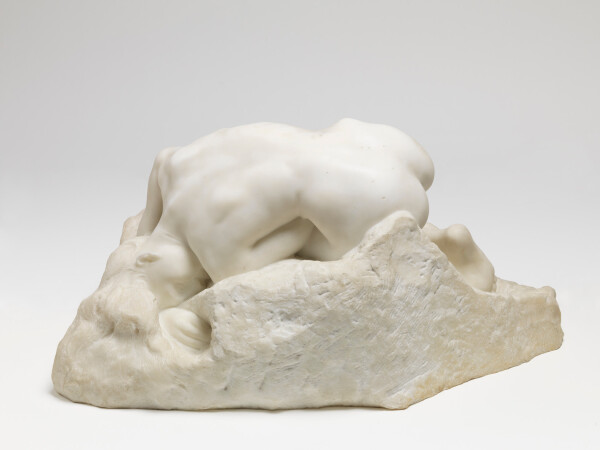

Auguste Rodin: La Danaïde, 1889

© Finnish National Gallery

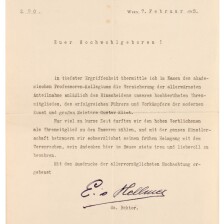

In September 1917, Gustav Klimt presented 13 oil paintings at the Österrikiska Konstutställningen [Austrian Art Exhibition] in Stockholm, including two of his latest allegories: Leda and Baby. Together with the unfinished works The Bride and Adam and Eve, they constitute the artist of the century’s artistic legacy.

On the one hand, Klimt’s late allegories tie in with his fantastic compositions of death, life, and female sexuality. On the other hand, he revisits established mythological and biblical themes, as he had last done in 1909 with his Judith II (Salome) (1909, Ca’Pesaro – Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna, Venice). In terms of style, colorful and wildly patterned fabrics and dark, mottled, and monochrome backgrounds clearly identify the painting as a late work.

Christian Genesis and Ancient Mythology

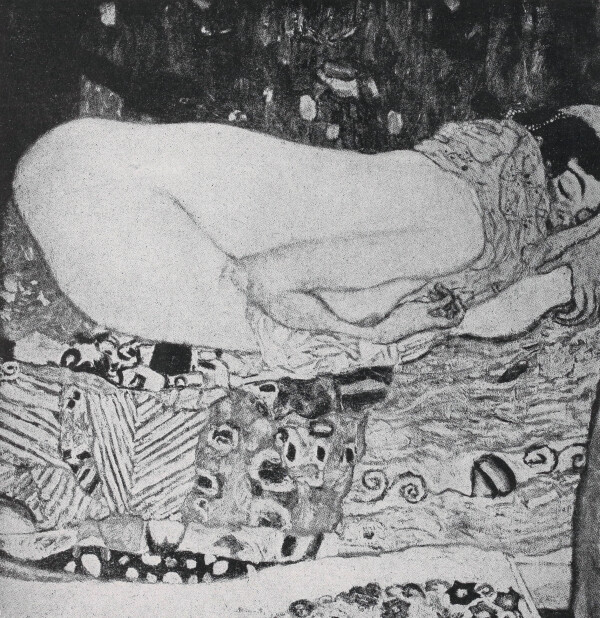

Barely ten years after Gustav Klimt had first dealt with the erotic adventures of Zeus, the father of the gods, in Danaë (1907/08, private collection), he turned to the legend of Leda and the Swan in another oil painting. The story of Leda, who was impregnated by the father of the gods in the guise of a swan, had repeatedly been formulated as an erotic scene since the High Renaissance.

As he had in Danaë and The Virgin (1913, National Gallery, Prague), Klimt depicted his protagonist asleep. The motif of the erotic dream occupied the artist time and again over the years. The sleeping Leda, depicted in the nude, is shown crouching on her bed. Her conspicuously lifted buttocks, her breast peeping out from under her arm, and the figure’s right hand, clawing into the upholstery as if in rapture, are the only indicators that this is a sexual scene. The phallus-shaped black swan and Leda’s relaxed facial expression also subtly enhance the erotic component. The swan, touching Leda innocuously on the back, is relegated to the margin of the painting as a masculine pictorial element.

Klimt first dealt with the figure of Leda in studies in 1913/14. He took up the theme again in 1917. While the ancient marble sculptures of the Callipygian Venus, the goddess of love with her magnificent buttocks, are often cited in literature as models for the female figure, it seems obvious that Leda was inspired by Rodin’s La Danaïde (1889, Musée Rodin, Paris). Originally conceived as a figure for the Gates of Hell, it is considered one of the most sensual representations in Rodin’s oeuvre.

The work, which unfortunately has only survived in a black-and-white photograph, stands out as a typically late work, especially because of the turbulently patterned sheets and the composition’s apparent lack of spatiality. Since the painting fell victim to fire in World War II, unfortunately nothing can be said about its colors. In an article about the estate exhibition at Gustav Nebehay’s gallery in 1919, however, there is talk of a “dazzling” Leda. A similarly garish palette as that of Friends II (1916/17, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945) or Lady with a Fan (1917/18, unfinished, private collection) would therefore seem plausible.

Gustav Klimt: Adam and Eve, 1916-1918, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

Adam and Eve

Before his death in 1918, Klimt was to make use of time-honored iconography one last time to express his ideas about man and woman, sexuality, and hidden eroticism.

Adam and Eve (1916–1918, unfinished, Belvedere, Vienna) is one of Klimt’s rare works in which he dealt with figures from the Old Testament. Whereas his two depictions of Judith had addressed the role of the femme fatale, the painting Adam and Eve follows Klimt’s allegories on the relationship between man and woman. Klimt had already dealt with gender roles, the differences between man and woman, and their inevitable merging in the act of love in The Kiss (Lovers) (1908/09, Belvedere, Vienna) and the motif of the embrace in the Stoclet Frieze (1905–1911, private collection). While Adam and Eve formally takes up the artist’s visual preferences from the Golden Period – the man, with his dark skin and hair and the wild, animalistic loincloth rendered in contrast to the naked, fair-skinned, almost radiantly blonde woman standing amidst soft, pinkish red flowers – he now seems to reverse their roles. Whereas the man always played the dominant, protective part in the motifs of embrace, he is now portrayed as a passive figure. With his eyes closed, he stands behind Eve. She looks at the viewer knowingly and completely uncovered. Like Nuda Veritas (1899, Theatermuseum, Vienna), she knows the truth about her nature as a woman and has shed the veil of ignorance. Again, Klimt used the cloak of biblical iconography that gave him permission to depict explicit female nudity. However, Klimt omits the shame that she is supposed to feel according to the literary example, and the attempt to cover herself. Eve has thus already eaten from the Tree of Knowledge, while Adam is still blind and ignorant about his sexuality. The hands, already outlined in the underdrawing, with her left presumably meant to hold the apple, indicate that Eve is about to take Adam by the hand and introduce him to the mystery of sensuality and eroticism. However, the painter could not complete this part before his death.

Toward the end of his life, Gustav Klimt once again celebrated the power of women, the power of love, and its fateful end. At this point, Klimt’s idea of a seductive femme fatale, which he had already developed in the course of his Judith at the beginning of the century, comes full circle. Klimt’s female protagonists lure the man on to destruction through their raw, sexual energy.

Klimt’s Adam and Eve, however, also depict a union of man and woman that testifies to love and trust. The woman leans against the man, supporting him, while he leans against her, content and secure. The two hands, which are not yet executed, could have been planned as being clasped in an intimate gesture. The depiction is thus a charged interplay between love and trust, as well as sexuality and betrayal.

The painting is one of those works that had remained unfinished in the artist’s studio after his death. It was presented to the public for the first time in an exhibition of Klimt’s estate organized by Gustav Nebehay and was immediately acquired by Sonja Knips.

Insight into the Villa Knips, 1920s

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Baby, 1917/18, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Otto and Franciska Kallir with the help of the Carol and Edwin Gaines Fullinwider Fund 1978

© Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

From the Cradle to the Altar of Marriage

In addition to established iconographic themes, Klimt also dealt with his own thematic circle of birth, death, and all the intermediate stages of the life cycle.

The work Baby (1917/18, unfinished, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.), also known under the title “Cradle” or “Child,” is one of the artist’s few portraits of children. To be assigned to the group of his life cycle subjects, it represents the beginning of life, the first stage of existence, following the pictures of Hope depicting pregnant women. The inspiration for the preoccupation with young life could have been the birth of Klimt’s second son with Consuela Huber in 1915 and the death of their daughter that same year.

Compositionally, the painting follows Klimt’s commissioned portraits of the years 1914 to 1918. The mottled greenish background, the colorful piles of fabric, and the arrangement of pictorial ornaments within a triangular composition are all elements that can also be found in Portrait of Amalie Zuckerkandl (1917/18, unfinished Belvedere, Vienna) and Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer (1914–1916, private collection), among others. As in Portrait of Friederike Maria Beer (1916, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, The Mizne-Blumenthal Collection), the child’s pearly face stands out strongly from the colorfully patterned environment and is thus augmented. At the same time, however, it almost seems to be lost in the mass of fabric. Klimt’s intensified concentration on the play of colors, forms, and patterns determined his entire late work.

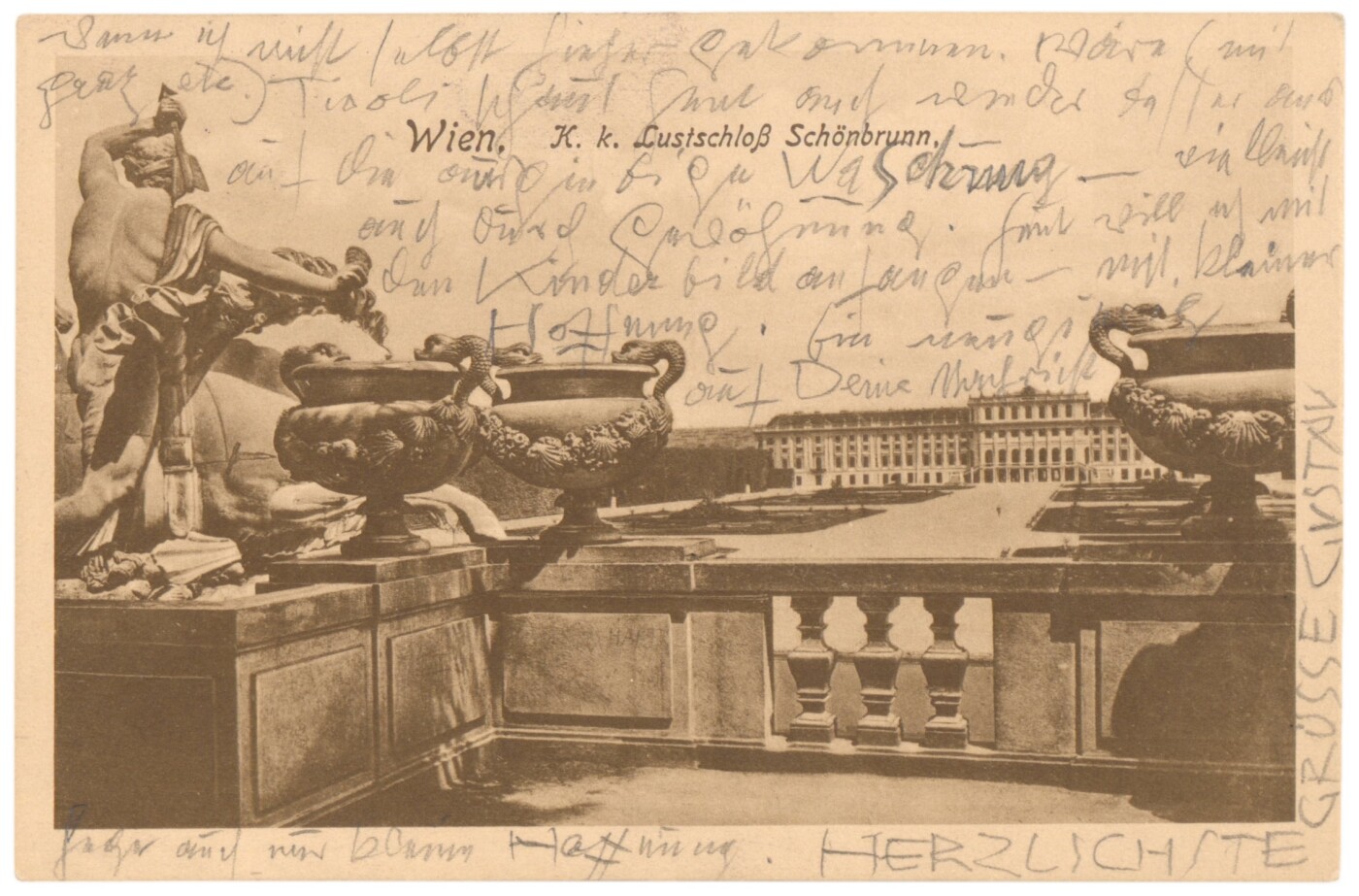

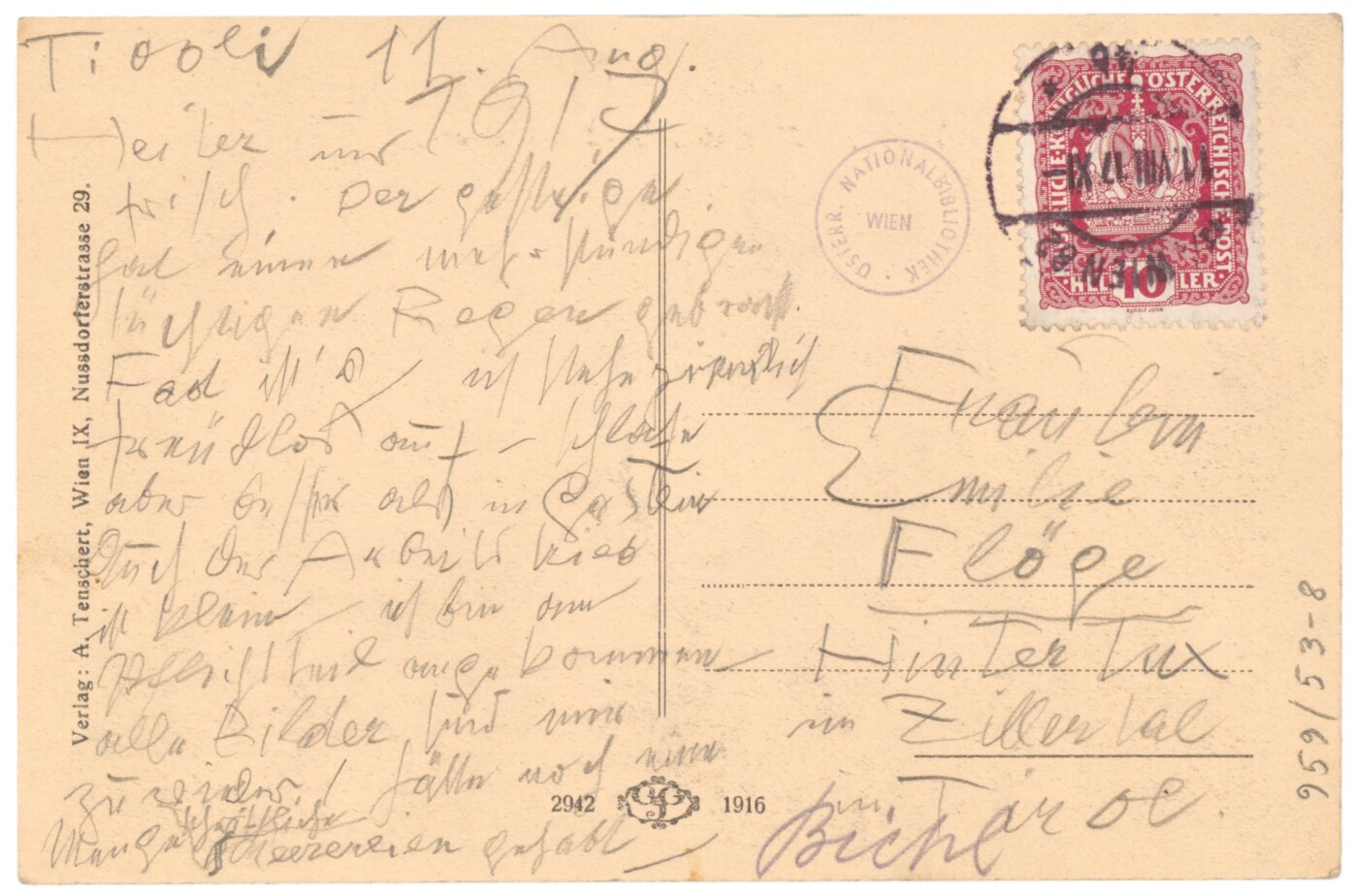

The painting was probably created within a relatively short period of time between August and September. On 11 August, he reported to Emilie Flöge that he would like to “begin with the child’s picture.” The very next day, the first coat of paint was applied. According to Klimt himself, Baby was already half finished on 13 August:

“the child’s picture half finished – today it should be completed – if it’s true – extremely mixed feelings about it.”

In September 1917 the painting was shown publicly for the first time at an exhibition in Stockholm. Photographs of the exhibition reveal that Klimt made a few more changes to the work after the show. The work can therefore only be said to have been completed around 1918.

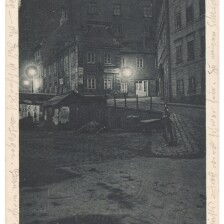

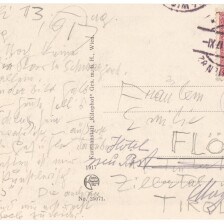

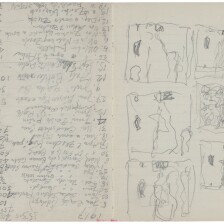

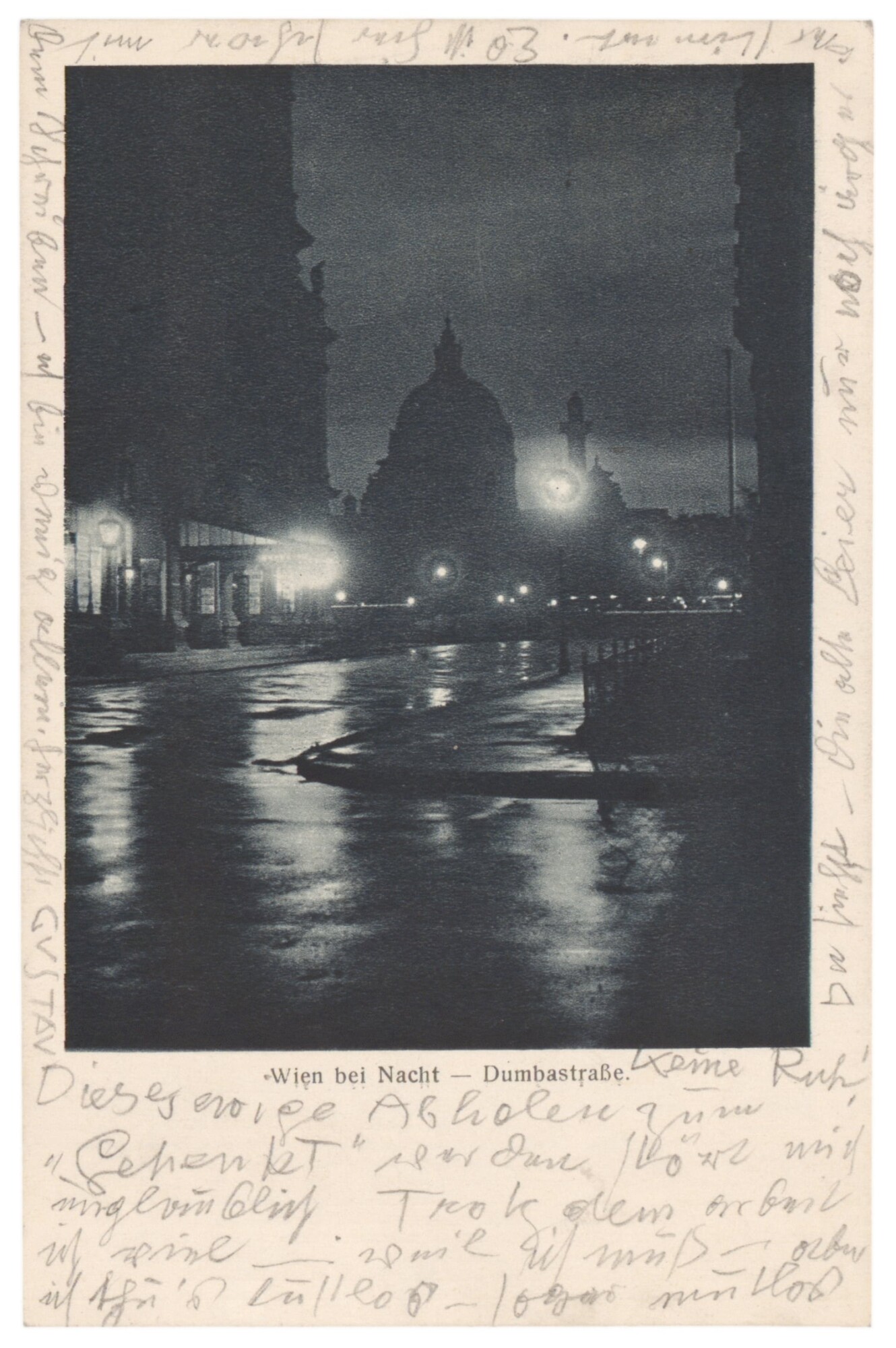

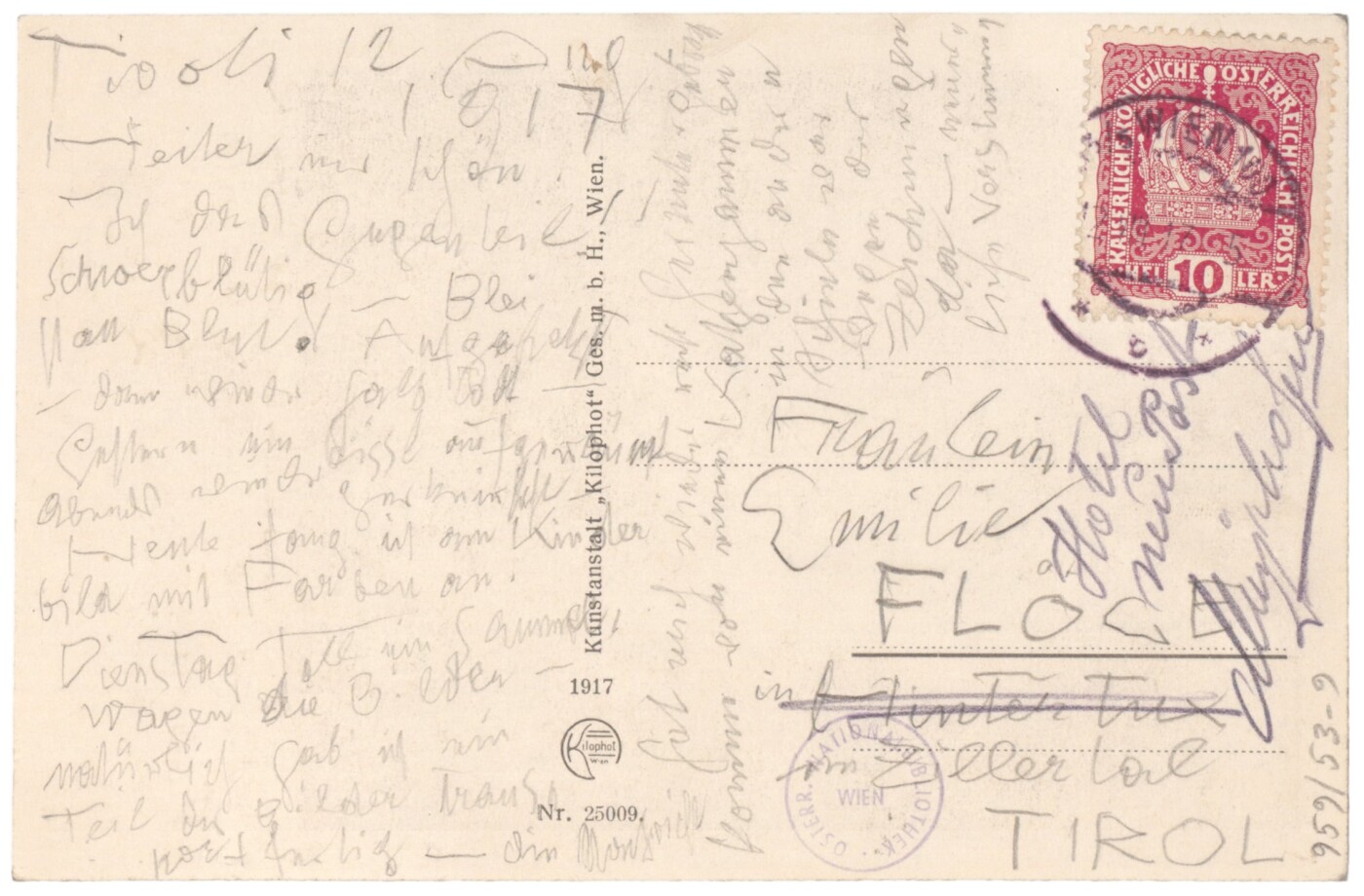

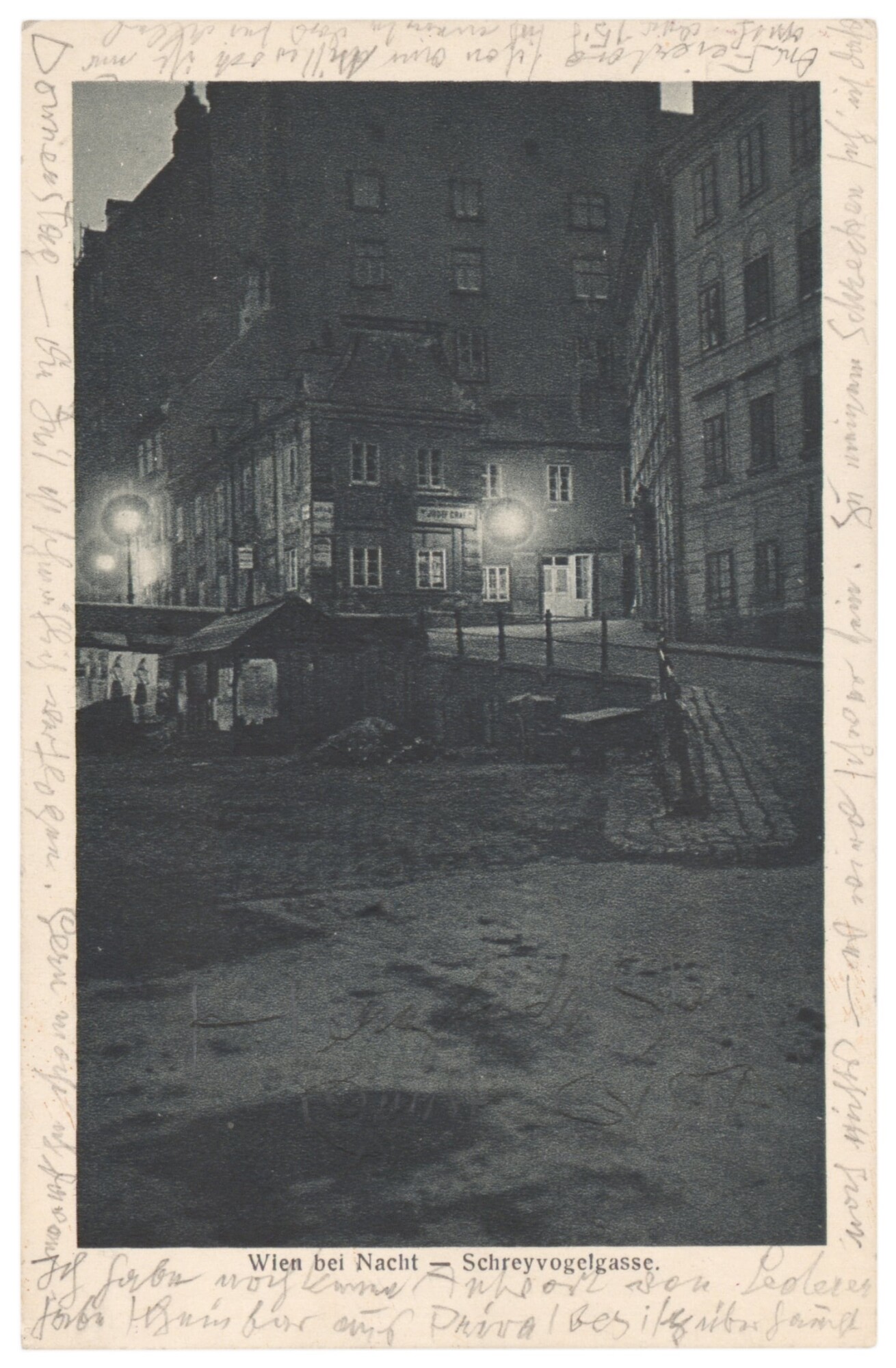

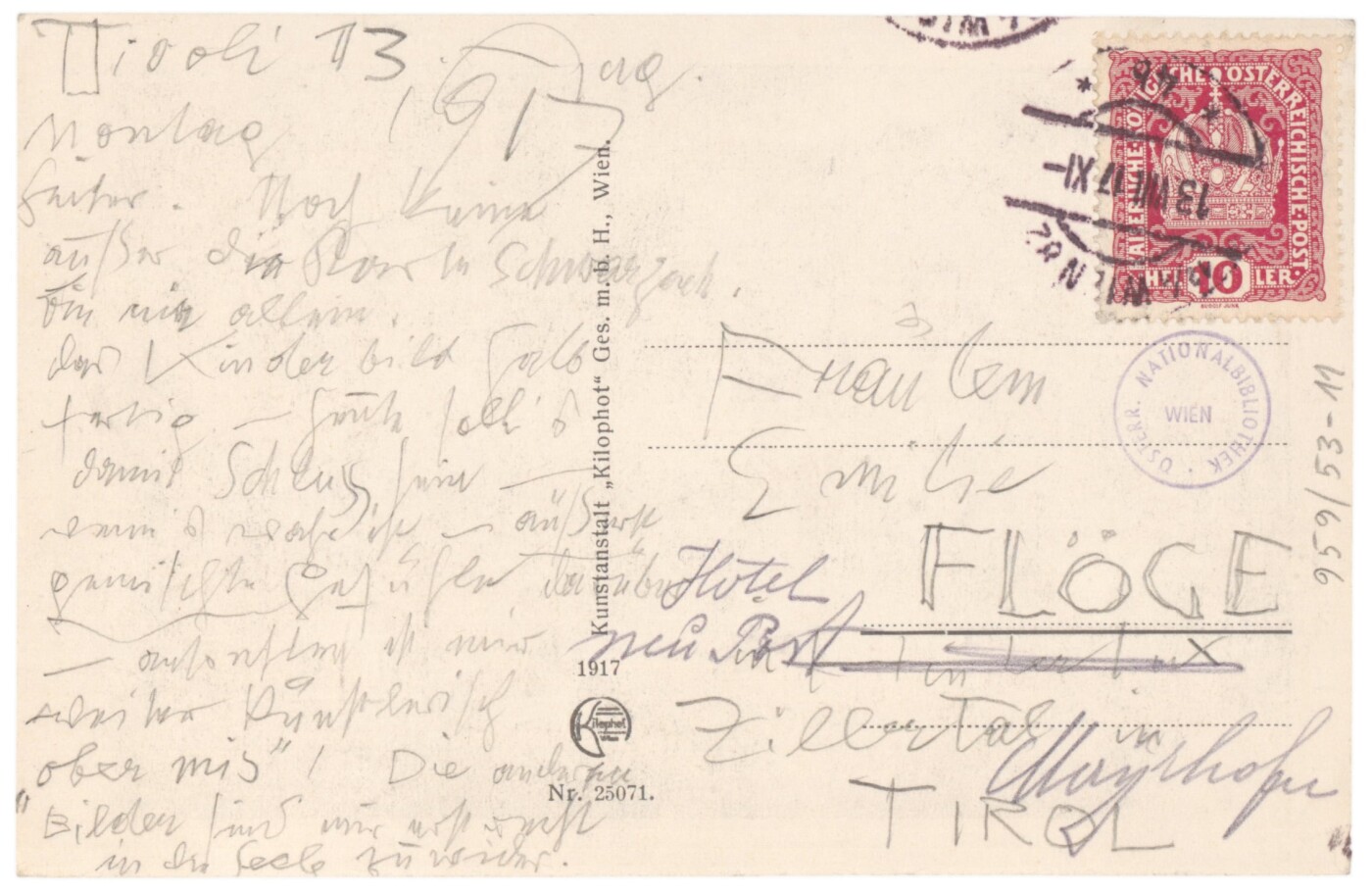

Picture Postcards from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Emilie Flöge in Tyrol, 1917

-

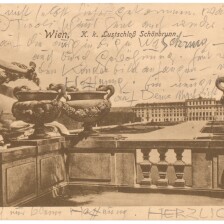

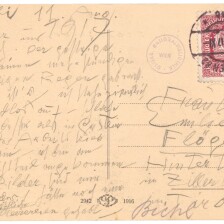

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Emilie Flöge in Tyrol, 08/11/1917, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Sammlung von Handschriften und alten Drucken

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Emilie Flöge in Tyrol, 08/11/1917, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Sammlung von Handschriften und alten Drucken

© Department of Manuscripts and Rare Books, Austrian National Library -

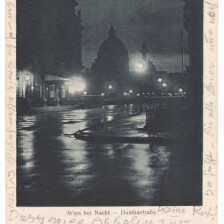

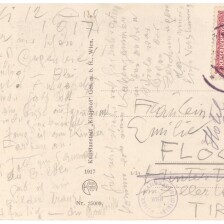

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Emilie Flöge in Tyrol, 08/11/1917, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Sammlung von Handschriften und alten Drucken

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Emilie Flöge in Tyrol, 08/11/1917, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Sammlung von Handschriften und alten Drucken

© Department of Manuscripts and Rare Books, Austrian National Library -

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Emilie Flöge in Tyrol, 08/12/1917, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Sammlung von Handschriften und alten Drucken

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Emilie Flöge in Tyrol, 08/12/1917, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Sammlung von Handschriften und alten Drucken

© Department of Manuscripts and Rare Books, Austrian National Library -

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Emilie Flöge in Tyrol, 08/12/1917, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Sammlung von Handschriften und alten Drucken

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Emilie Flöge in Tyrol, 08/12/1917, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Sammlung von Handschriften und alten Drucken

© Department of Manuscripts and Rare Books, Austrian National Library -

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Emilie Flöge in Tyrol, 08/13/1917, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Sammlung von Handschriften und alten Drucken

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Emilie Flöge in Tyrol, 08/13/1917, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Sammlung von Handschriften und alten Drucken

© Department of Manuscripts and Rare Books, Austrian National Library -

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Emilie Flöge in Tyrol, 08/13/1917, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Sammlung von Handschriften und alten Drucken

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Vienna to Emilie Flöge in Tyrol, 08/13/1917, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Sammlung von Handschriften und alten Drucken

© Department of Manuscripts and Rare Books, Austrian National Library

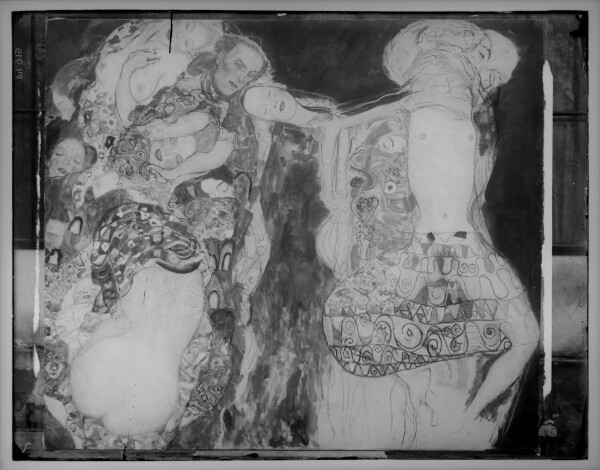

Gustav Klimt: The Bride, 1917/18, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Moriz Nähr: Gustav Klimt's workshop in Feldmühlgasse, presumably 1917, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Moriz Nähr: The bride, 1917/18, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Klimt’s life cycle pictures also include his last unfinished monumental work The Bride (1917/18, unfinished, Klimt-Foundation, Vienna). Together with The Virgin (1913, National Gallery, Prague) and Death and Life (Death and Love) (1910/11, reworked 1912/13 and 1916/17, Leopold Museum, Vienna), it forms a trio in Klimt’s oeuvre. The large-sized works of the late phase are fantastic allegories that explore the mystery of the human psyche through color, ornamentation, and a very unique pictorial language.

The Bride is the last large-sized work Klimt worked on before suffering a cerebral stroke in January 1918. A photograph by Moriz Nähr – probably taken shortly before the artist’s death – shows the unfinished painting on an easel in the master’s studio. The low stool and the carpet in front of the painting suggest that the artist had still worked on the painting shortly before. While parts of the composition already appear to be finished, about a third still shows the bare canvas, on which the preliminary pencil drawing is clearly visible.

Klimt had already been working on the composition since 1915/16 in his preliminary drawings, preparing it in over 140 sketches until 1917. While in Death and Life (Death and Love) and The Virgin he had still inscribed his groups of figures in geometrically arranged forms, in The Bride they now take up the entire space, almost filling the picture. The painting shows the eponymous bride in a blue dress at the center. She is surrounded by a crowd of eight women, a baby, and a man resembling a monk. This male figure is probably the groom. While most of the female figures are depicted asleep, the man gazes vigilantly at his sleeping bride as she leans against him.

The colorful, generously patterned scarfs characteristic of the late work have an ambivalent function in Klimt’s work: on the one hand, Klimt uses them to cover the nakedness of his protagonists; on the other hand, through the contrast of colored garments and light-colored skin, he directs the viewer’s attention to the exposed parts of the body. This rhythm of clothing and nudity is particularly emphasized in the elongated female figure on the right, under whose patterned semi-transparent skirt the pubic region is still clearly visible. Whether Klimt had intended to cover the private parts completely or whether this effect of transparence was intended must remain open because of the sudden termination of the artist’s work on the painting.

The multiple interpretations of the composition range from being a “vision” to “the Bride’s dreamt imaginations” to an allegory of Death. Recently, reference has been made to Arthur Schnitzler’s novella of the same name, Die Braut (1891), and the fact that the two artists knew each other personally. Such an interpretation would suggest a theme along the lines of the book of the woman being torn between marital duties and sexual inclinations. The chaste snuggling up of the protagonist, dressed in night blue like in Schnitzler’s work, to the groom and the baby would stand for the woman’s deep commitment to her duties as wife and mother, while the sexually charged female figures could represent the bride’s unbridled erotic fantasies.

Literature and sources

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band III, 1912–1918, Salzburg 1984.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band IV, 1878–1918, Salzburg 1989.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012.

- Fritz Novotny, Johannes Dobai (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Salzburg 1975.

- Emil Pirchan: Gustav Klimt. Ein Künstler aus Wien, Vienna - Leipzig 1942.

- Bertha Zuckerkandl: Gedächtnis=Ausstellung, in: Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, 06.02.1919, S. 2-3.

- Jane Kallir: Egon Schiele. The Complete Works, New York 1990.

- Sandra Tretter: „Phantasien, vollendete und unvollendete“. Gustav Klimts Allegorie Die Braut im Kontext seines Spätwerks und Arthur Schnitzlers gleichnamiger Novelle, in: Sandra Tretter, Hans-Peter Wipplinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Jahrhundertkünstler, Ausst.-Kat., Leopold Museum (Vienna), 22.06.2018–04.11.2018, Vienna 2018, S. 167-177.

- Die bildenden Künste. Wiener Monatshefte, 2. Jg. (1919).

- Elizabeth Clegg: War and Peace at the 1917 Stockholm ›Austrian Art Exhibition‹, in: The Burlington Magazine, 154. Jg., Heft 1315 (2012), S. 676-688.

- Jane Kallir (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Auf der Suche nach dem Gesamtkunstwerk, Ausst.-Kat., Hangaram Arts Center Museum (Seoul), 01.02.2009–15.05.2009, Munich 2009.

- Kunstchronik und Kunstmarkt. Wochenschrift für Kenner und Sammler, 54. Jg., Nummer 30 (1919), S. 19.

- Marian Bisanz-Prakken (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Ausst.-Kat., Albertina (Vienna), 14.03.2012–10.06.2012; Getty Center (Los Angeles), 03.07.2012–23.09.2012, Munich 2012.

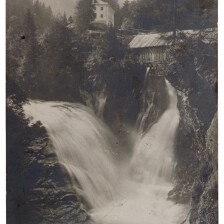

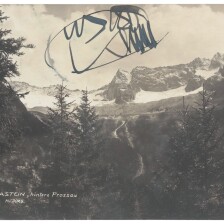

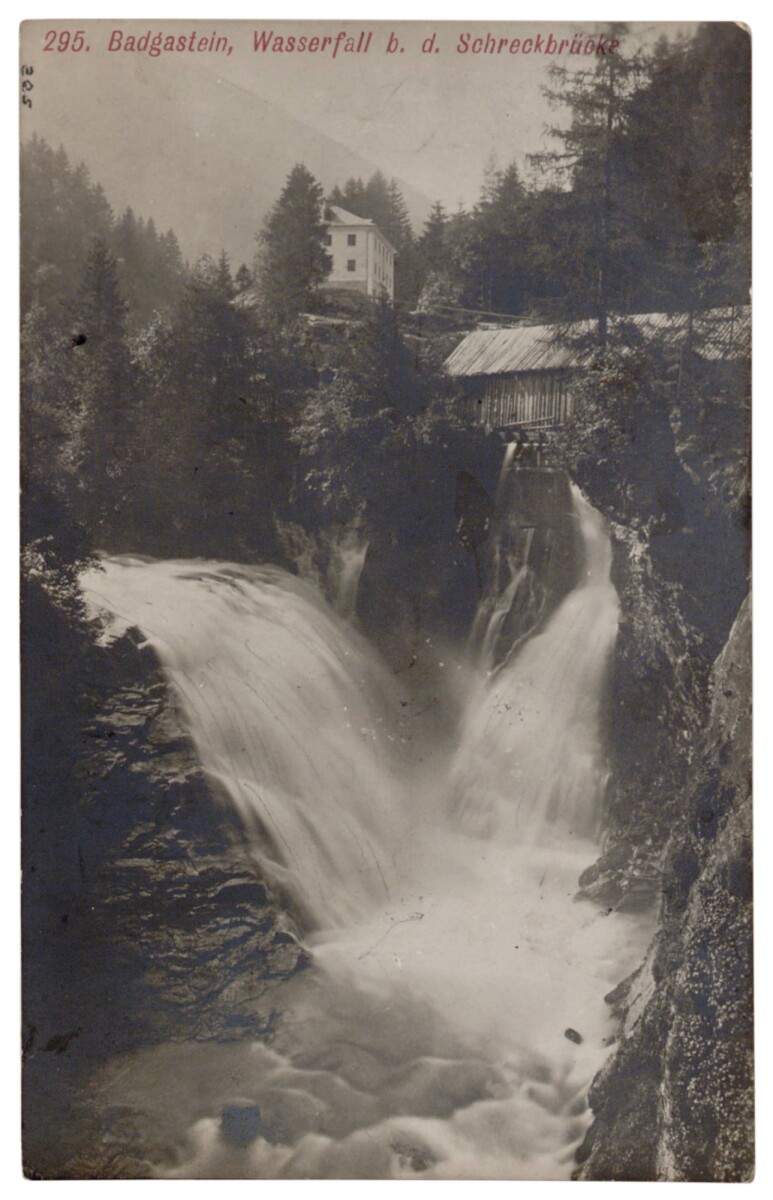

Bad Gastein as a Source of Inspiration

Gustav Klimt: Gastein, 1917, Verbleib unbekannt

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Starting in 1912, Gustav Klimt and Emilie Flöge mostly spent the month of July in the health spa resort of Bad Gastein. The oil sketch measuring 70 by 70 centimeters, as well as a composition study and smaller sketches of details in the painter’s last sketchbook indicate his artistic interest in the resort. The oil sketch was first owned by August and Serena Lederer. A black-and-white photograph by Moriz Nähr and a collotype print in Max Eisler’s Gustav Klimt portfolio, as well as several descriptions document the work, which is now considered lost.

Although Klimt used his time with Emilie Flöge at the spa primarily for recreation, the unique topography and sophisticated flair inspired him to paint the landscape Gastein (1917, whereabouts unknown, considered lost since the end of the war in 1945). This square-format work, which was formerly in the Lederer Collection, depicts the hotels on the northwestern slope of the town. Heinrich Zimburg, future Gastein spa director and editor of the Badgasteiner Badeblatt, described Klimt’s painted view of the Alpine spa as follows:

“As particularly charming subject matter, Gustav Klimt chose the hotels on Gastein’s northwestern slope, built one above the other in the style of a crèche– referred to as Italian quarter in common Gastein parlance.”

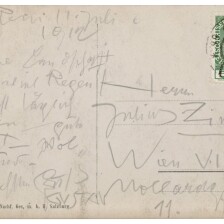

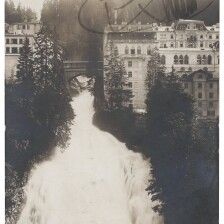

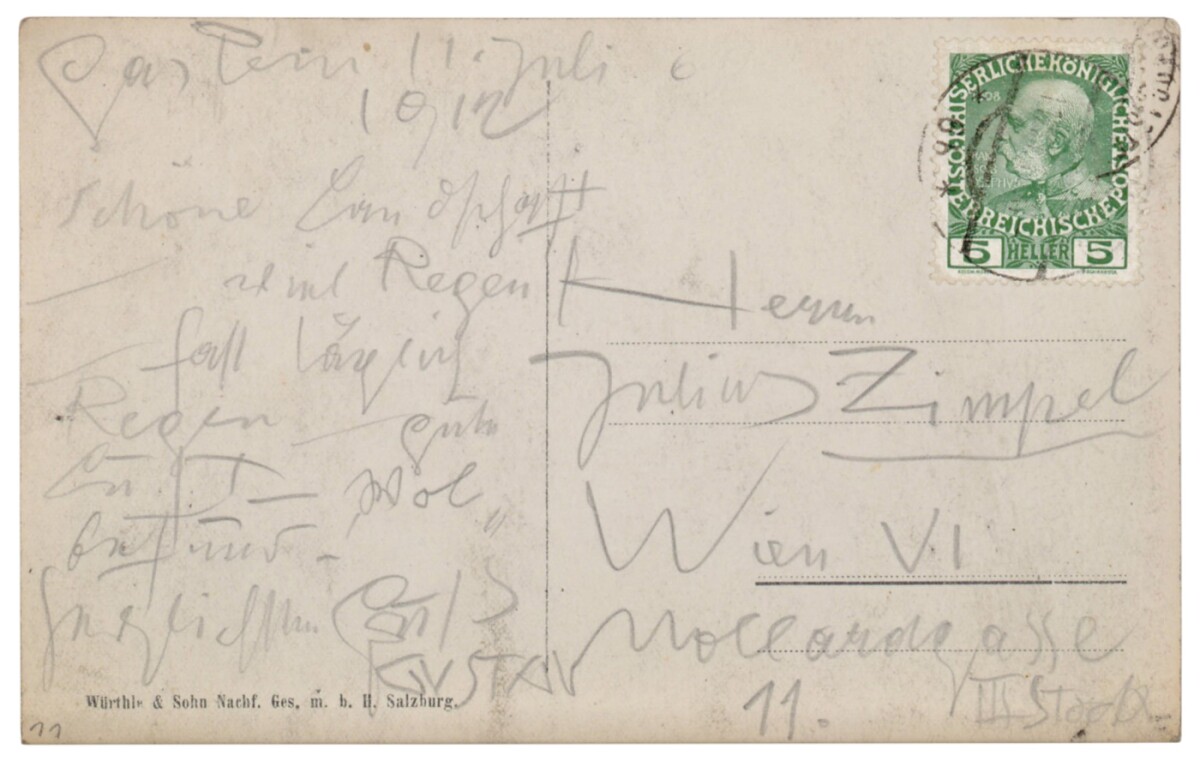

Picture Postcards from Gustav Klimt in Bad Gastein to Family Members and Acquaintances

-

Gustav Klimt: Picture Postcard from Gustav Klimt in Bad Gastein to Julius Zimpel sen. in Vienna, 07/11/1912, The Albertina Museum

Gustav Klimt: Picture Postcard from Gustav Klimt in Bad Gastein to Julius Zimpel sen. in Vienna, 07/11/1912, The Albertina Museum

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Picture Postcard from Gustav Klimt in Bad Gastein to Julius Zimpel sen. in Vienna, 07/11/1912, The Albertina Museum

Gustav Klimt: Picture Postcard from Gustav Klimt in Bad Gastein to Julius Zimpel sen. in Vienna, 07/11/1912, The Albertina Museum

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna -

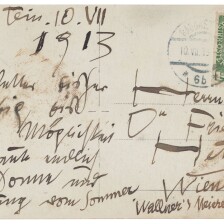

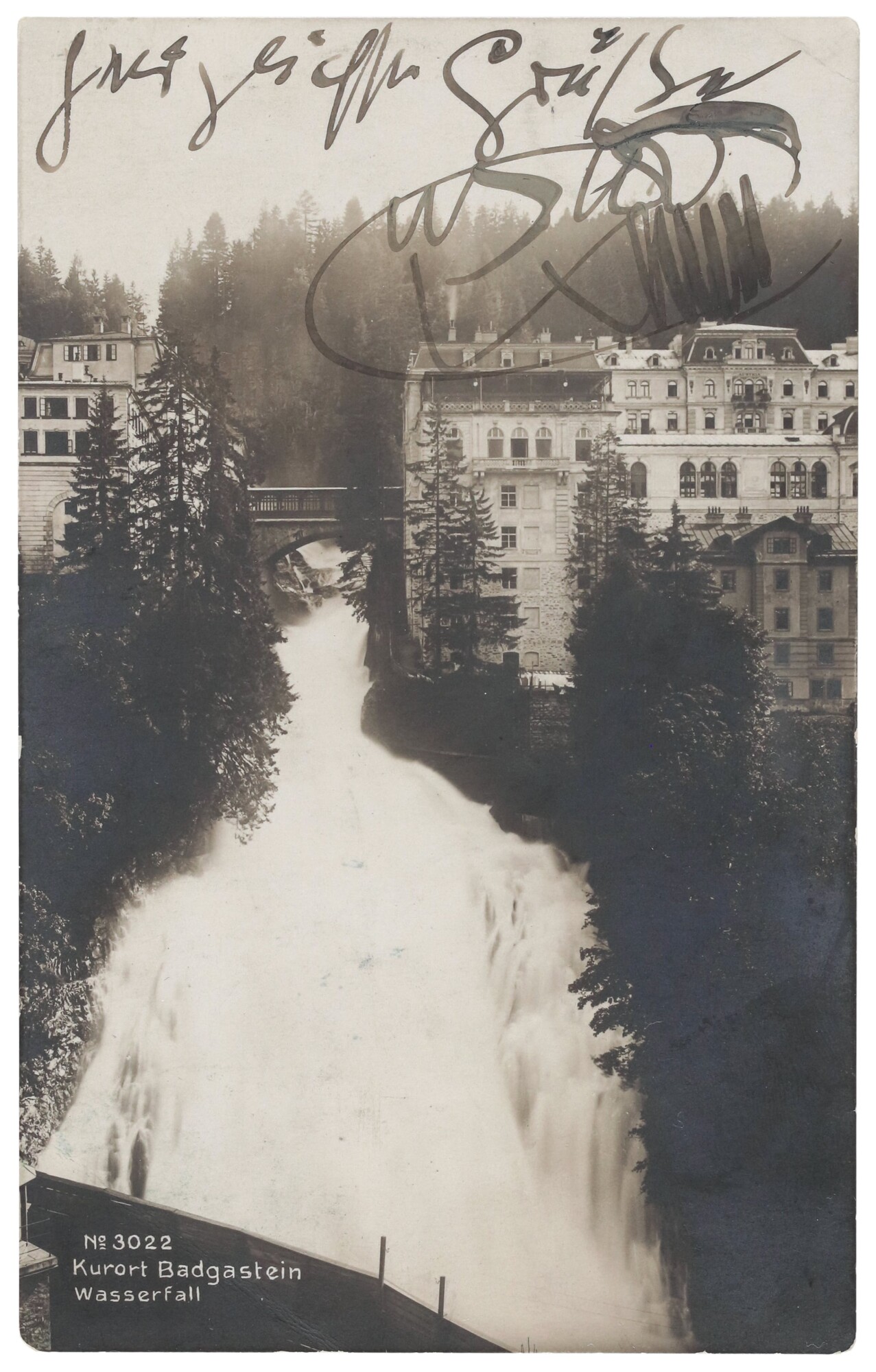

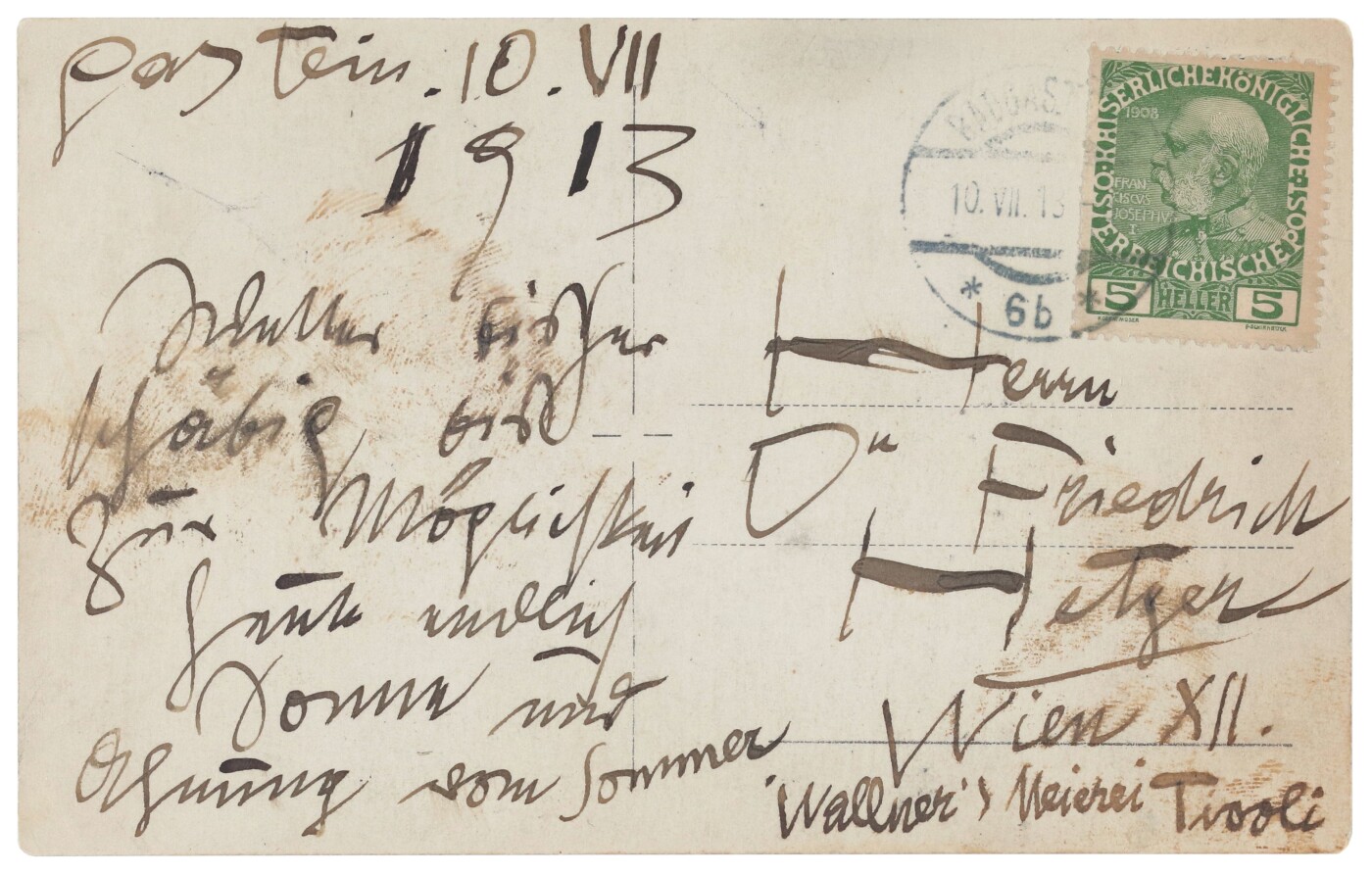

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Bad Gastein to Friedrich Hetzer in Vienna, 07/10/1913, Klimt Foundation

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Bad Gastein to Friedrich Hetzer in Vienna, 07/10/1913, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Bad Gastein to Friedrich Hetzer in Vienna, 07/10/1913, Klimt Foundation

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Bad Gastein to Friedrich Hetzer in Vienna, 07/10/1913, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

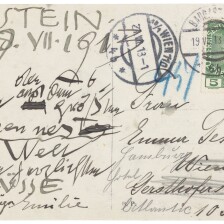

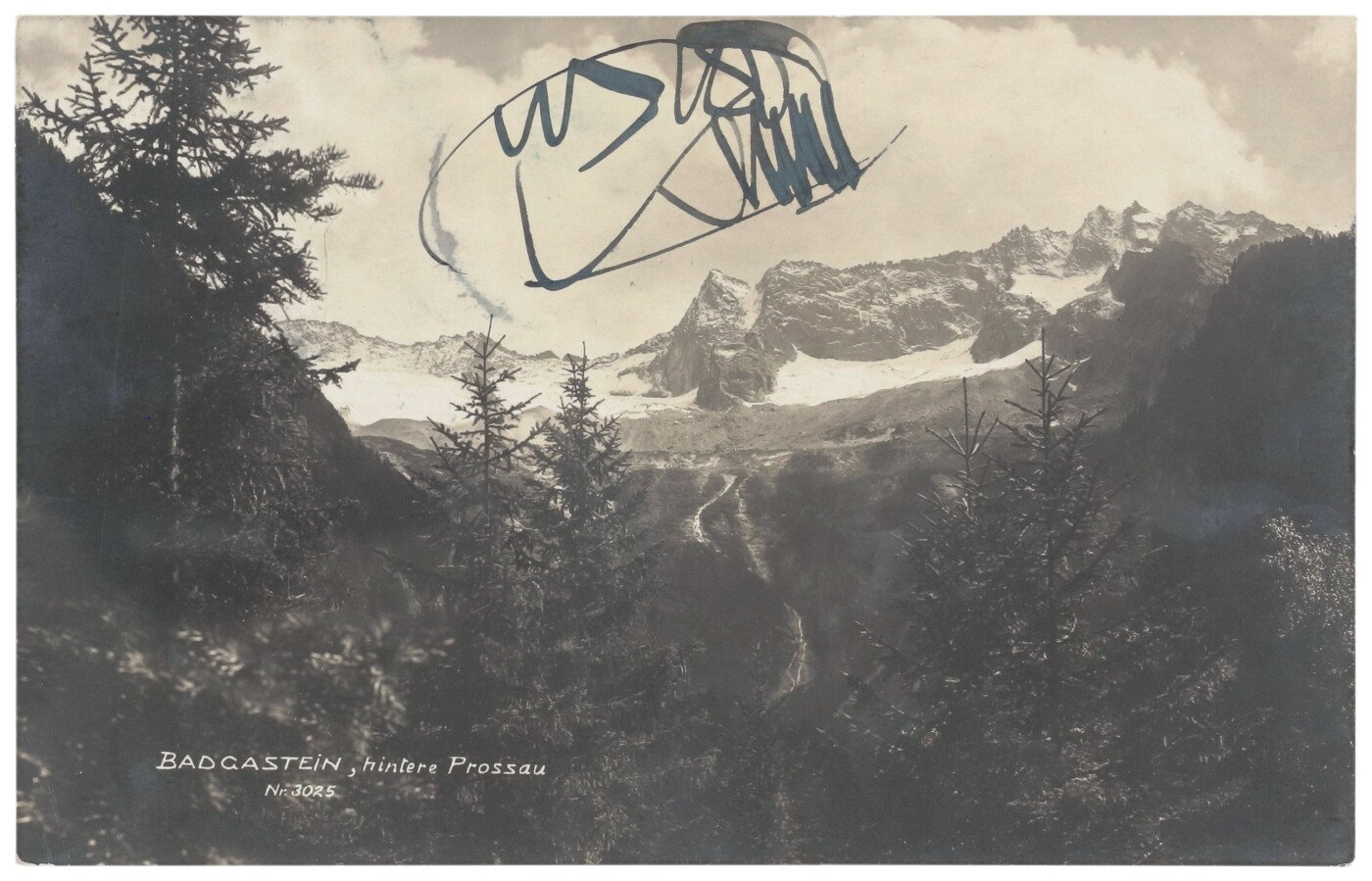

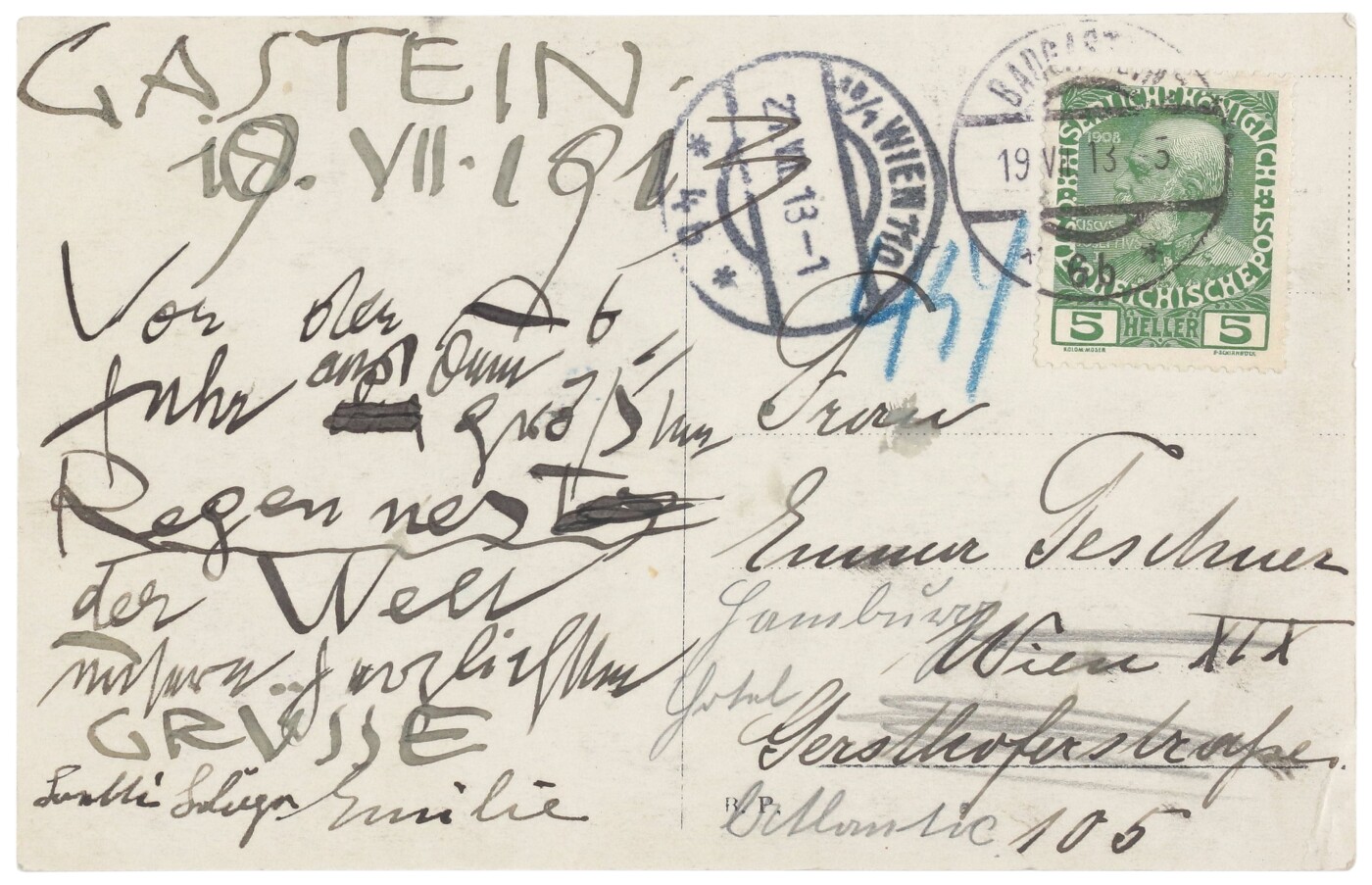

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Bad Gastein to Emma Bacher-Teschner in Hamburg, co-signed by Emilie and Barbara Flöge, 07/19/1913, Privatbesitz, courtesy Klimt-Foundation, Wien

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Bad Gastein to Emma Bacher-Teschner in Hamburg, co-signed by Emilie and Barbara Flöge, 07/19/1913, Privatbesitz, courtesy Klimt-Foundation, Wien

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Bad Gastein to Emma Bacher-Teschner in Hamburg, co-signed by Emilie and Barbara Flöge, 07/19/1913, Privatbesitz, courtesy Klimt-Foundation, Wien

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Bad Gastein to Emma Bacher-Teschner in Hamburg, co-signed by Emilie and Barbara Flöge, 07/19/1913, Privatbesitz, courtesy Klimt-Foundation, Wien

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

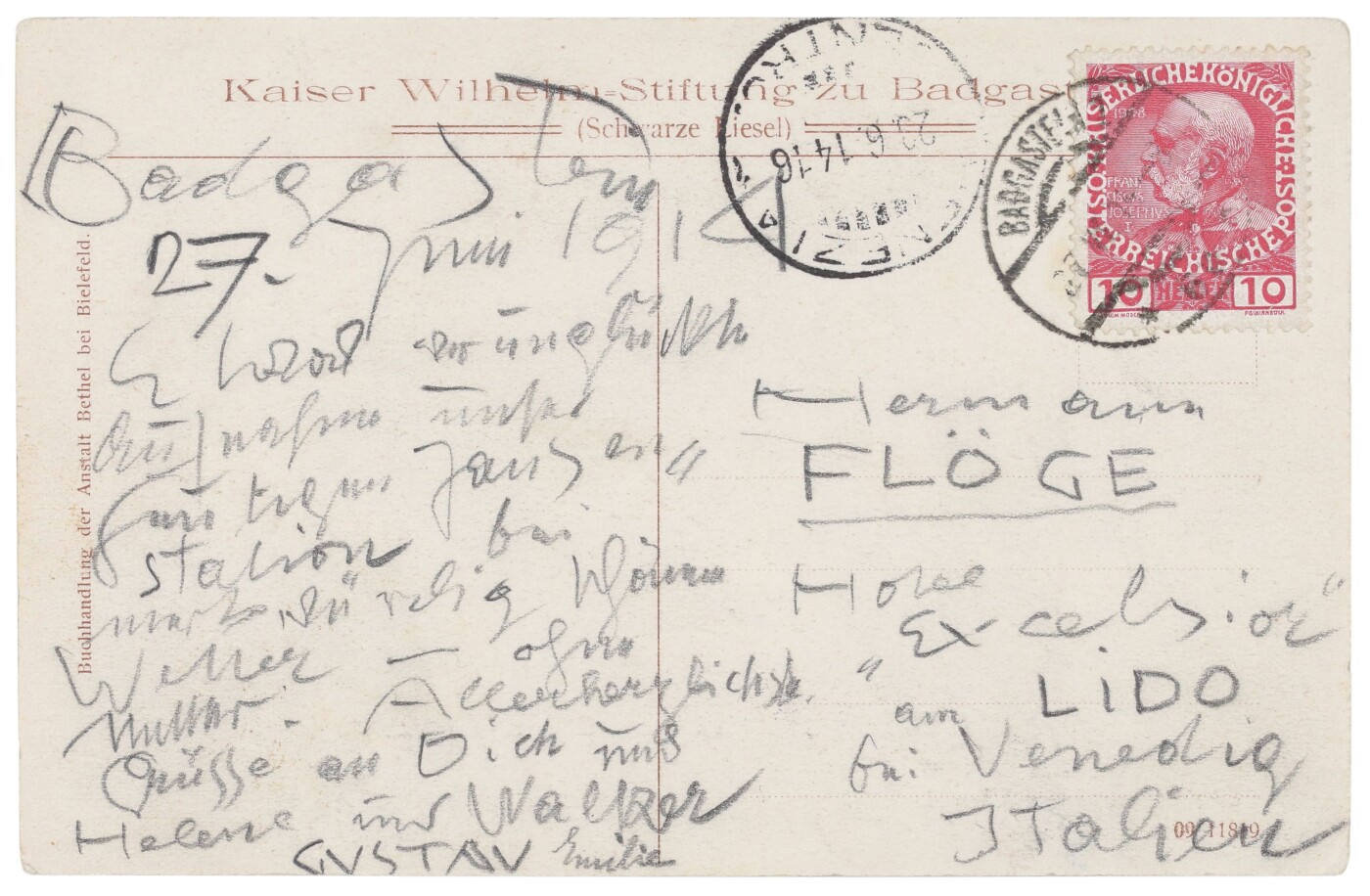

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Bad Gastein to Hermann Flöge jun. in Venice, co-signed by Emilie Flöge, 06/27/1914, Sammlung Villa Paulick, courtesy Klimt-Foundation, Wien

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Bad Gastein to Hermann Flöge jun. in Venice, co-signed by Emilie Flöge, 06/27/1914, Sammlung Villa Paulick, courtesy Klimt-Foundation, Wien

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Bad Gastein to Hermann Flöge jun. in Venice, co-signed by Emilie Flöge, 06/27/1914, Sammlung Villa Paulick, courtesy Klimt-Foundation, Wien

Gustav Klimt: Picture postcard from Gustav Klimt in Bad Gastein to Hermann Flöge jun. in Venice, co-signed by Emilie Flöge, 06/27/1914, Sammlung Villa Paulick, courtesy Klimt-Foundation, Wien

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Bath Gastein, around 1910

© Austrian National Library

Gustav Klimt: Church in Cassone on Lake Garda, 1913, private collection

© Sotheby's

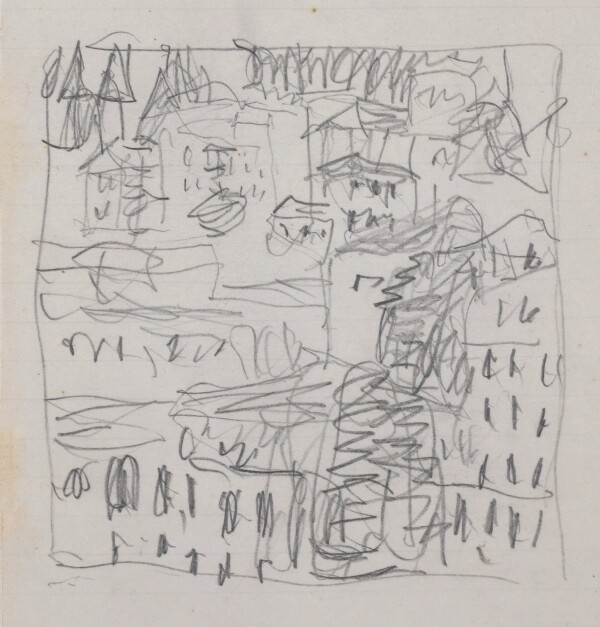

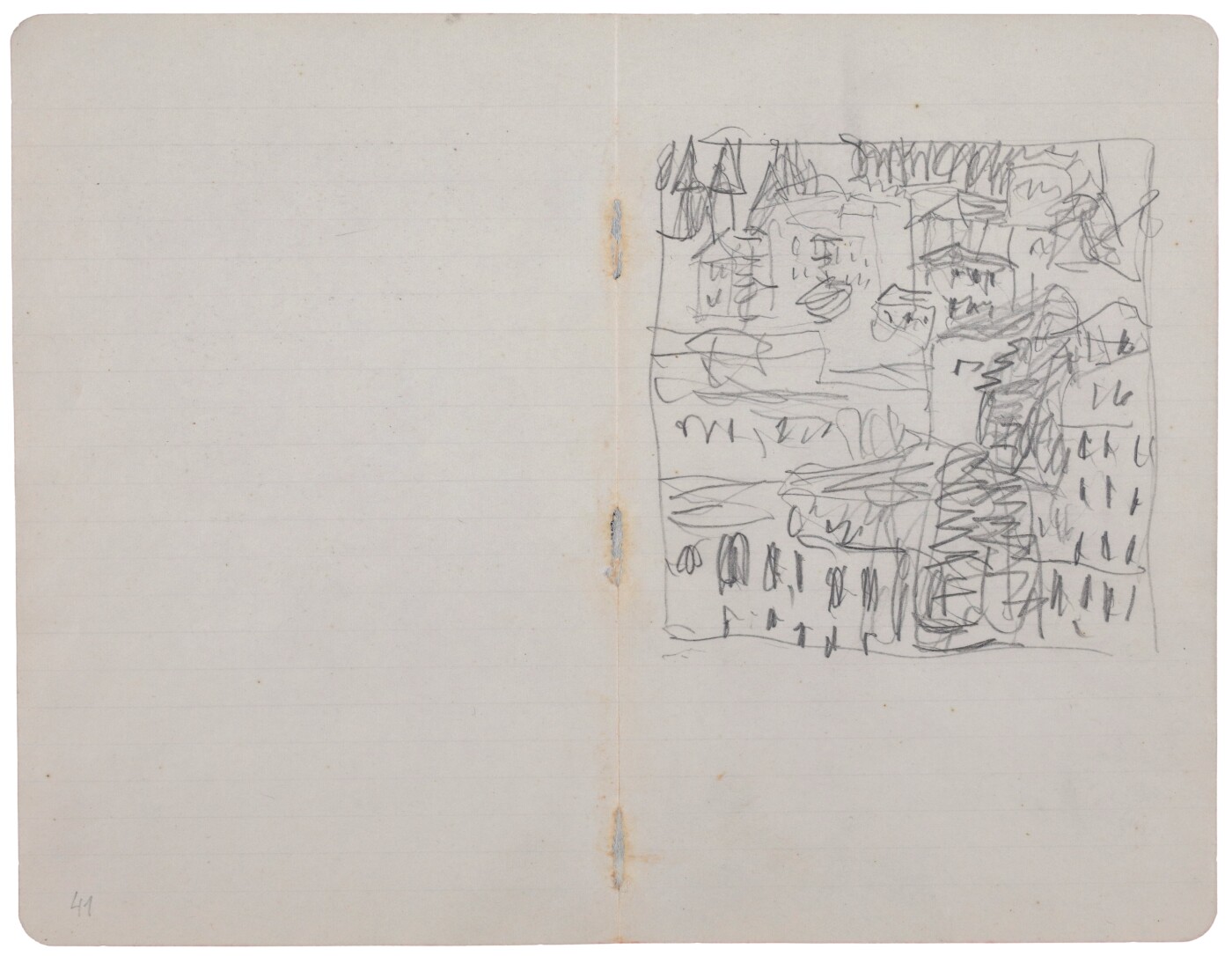

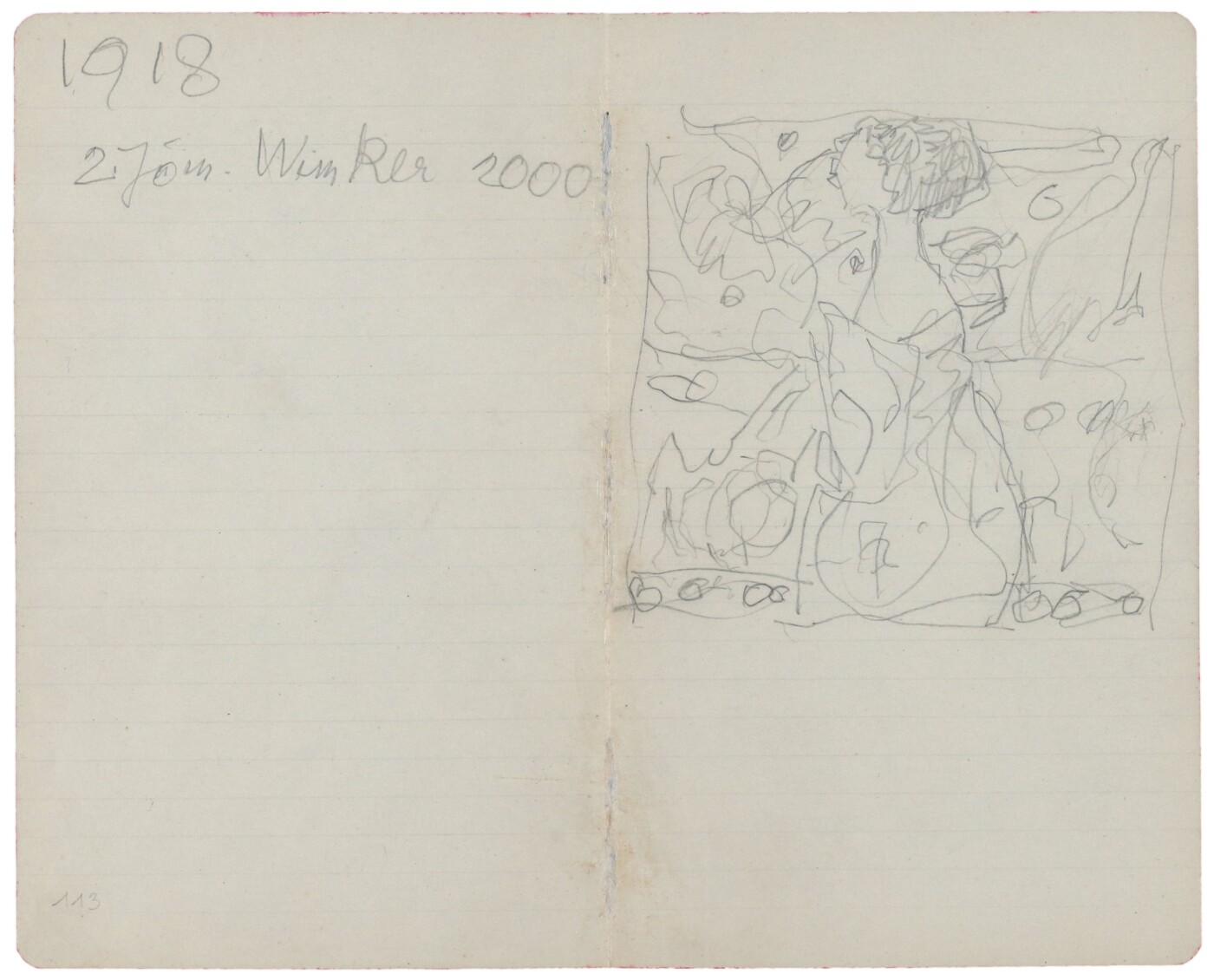

Gustav Klimt: Sketchbook by Gustav Klimt, 1917/18, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

The geographically motivated arrangement of the hotel buildings, which in this compressed form also found its way into Klimt’s painting, is certainly reminiscent of Klimt’s depictions of the architectural setting in Cassone and Malcesine on Lake Garda, which he had painted about three years earlier. The pictorial structure developed in Italy at that time was thus now adopted for Klimt’s depiction of Gastein’s Italian quarter. The name can be traced back to the master builder Angelo Comini, who came from Friuli. In Klimt’s case, a double meaning could thus be attributed to the Italian reminiscences.

It is only thanks to a description by Max Eisler that one gets an idea today of the extraordinary effect of the coloristic mood. Eisler emphasized Klimt’s tendency toward the painterly in his late work and mentioned the Gastein view as being “placed on white and blackish green, on polished ivory.” The contrast of the light-colored building facades shining forth between the green of the conifers seemed to him characteristic of the atmosphere of the place.

According to Erich Lederer, Klimt originally considered the effect of chromatic accents in the painting in the form of pasted strips of colored paper meant to refer to the flagging for the birthday of Emperor Charles I on 17 August. The oil sketch, which Klimt quite probably painted in situ, described the unique atmosphere of the Alpine spa in a color composition of selected tones of a limited chromatic spectrum, so that he must subsequently have abandoned the variant with the flags.

Klimt probably used his personal optical aid, the so-called “motif finder,” to define the view. It was presumable the hill of the former Kurhotel Mirabell on Bismarckstraße that served as Klimt’s vantage point.

There is a sketch for the Gastein motif in the last Sketchbook (1917/18, Klimt-Foundation, Vienna). Further studies it contains show dark coniferous trees. Due to its small format it is assumed that Gastein served as an oil sketch Klimt wished to translate into a larger painting in his studio in Vienna.

Literature and sources

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007.

- Emil Pirchan: Gustav Klimt, Vienna 1956.

- Christian Philipsen, Thomas Bauer-Friedrich, Wolfgang Büche (Hg.): Gustav Klimt und Hugo Henneberg. Zwei Künstler der Wiener Secession, Ausst.-Kat., Moritzburg Art Museum Halle (Saale) (Halle (Saale)), 14.10.2018–06.01.2019, Cologne 2019.

- Badgasteiner Badeblatt, 16. Jg., Nummer 36 (1956), S. 453ff..

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band III, 1912–1918, Salzburg 1984, S. 246.

Last Stays on the Attersee

Forester's lodge in Weissenbach am Attersee

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Gustav Klimt and Friederike Maria Beer on a walk in Weissenbach, summer 1916, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

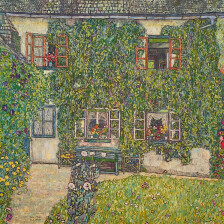

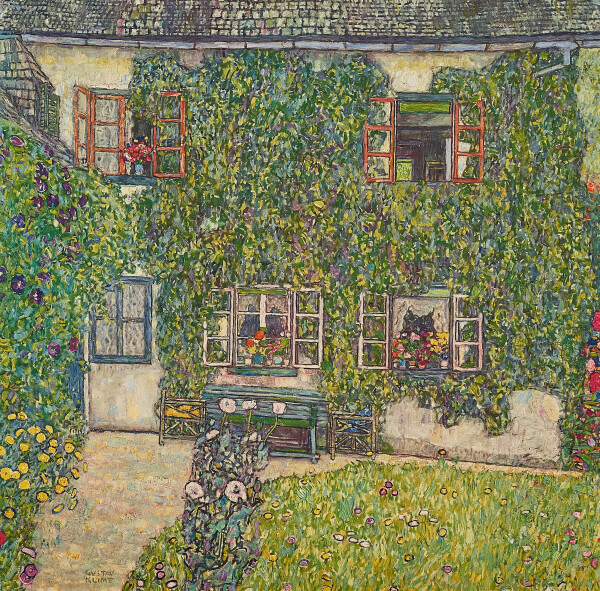

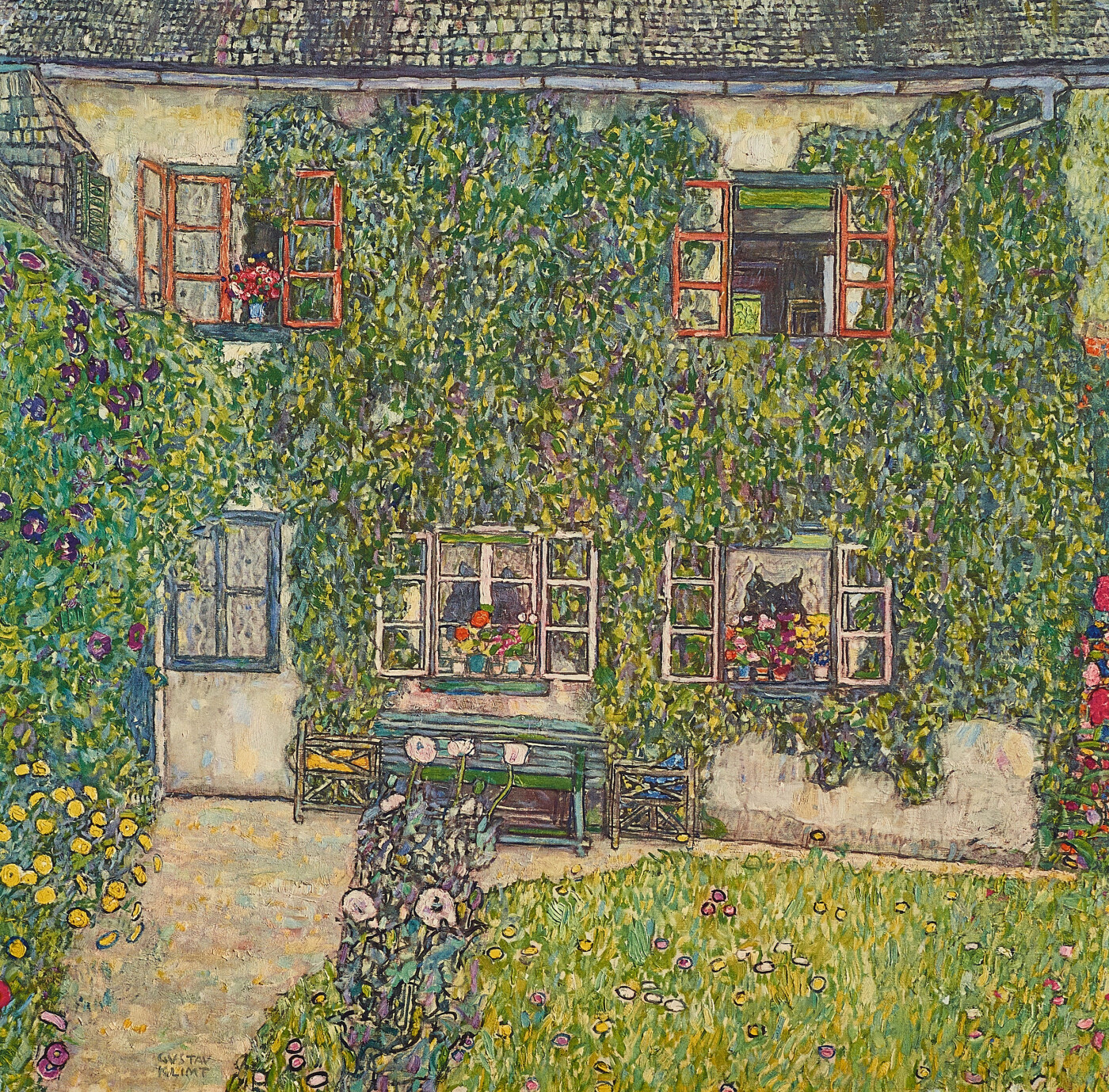

Gustav Klimt: Forester's House in Weissenbach on the Attersee I, 1914, private collection

© Belvedere, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Forester's House in Weissenbach on the Attersee II, 1914, Neue Galerie New York

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Litzlberg on the Attersee, circa 1915, private collection

© Sotheby's

Between 1914 and 1916, Gustav Klimt spent his last three summers on the southern shore of the Attersee. He rented a remote forester’s lodge in Weißenbach, which appears in two painted views. Apart from picturesque garden landscapes, he also captured Unterach on the southwestern shore and Litzlberg, located in the north of the lake, in oil on canvas – twice and three times respectively.

From 1914 on, the Flöge family found a new place to stay at Haus Donner in Steinbach on the Attersee. Before, they had resided at Villa Oleander in Kammerl, but this was not possible that summer as the place was rented to other guests. It was probably Friedrich Paulick junior who recommended the forester’s lodge, located at the entrance into the Weißenbach valley, to Klimt. Between 1914 and 1916 it was there that Klimt found the peace and seclusion he desired. Friends of the painter spoke of a “bliss” for which he had longed so much, a retreat into a private world unperturbed by outside influences. Herta Schrey, the former owner of the nearby Villa Sans Souci in Weißenbach, recalled that Emilie Flöge and Klimt visited each other every day and spent most of their time together:

“As a child, I occasionally spotted him in our garden in his caftan-like cloak, with an easel and painting utensils, or also on the go, sometimes riding a bicycle. […] In 1914, when the war began, he was certainly in Weißenbach, because people said that on the day the war broke out (on 28 July 1914), all papers were sold out at the newspaper kiosk of the hotel, and Klimt was enraged because he could not get hold of a paper.”

Forester’s House in Weißenbach and Unterach

Klimt captured the building situated on a sloping meadow near the edge of a forest in two paintings, Forester’s House in Weißenbach on the Attersee I (1914, private collection) and Forester’s House in Weißenbach on the Attersee II (1914, Neue Galerie New York, Estée Lauder Collection). The work Tree Landscape in the Weißenbach Valley on the Attersee (1916, private collection), painted during the last summer on the Attersee, once again reveals Klimt’s interest in a harmonious combination of rural architecture and the Salzkammergut’s natural scenery. The amalgamation of architecture and nature is indeed a characteristic feature of Klimt’s late landscapes.

In Forester’s House in Weißenbach on the Attersee I, the viewer’s gaze is directed over a lush flowering meadow and then held up by the rising flank of the Schoberstein behind the building. While the façade is entirely overgrown with wild vine tendrils, the wooden shingles of the roof offer a rich and fragmented pattern of light reflections, the tones of which recur in the soft, hilly landscape. As he had done in the landscape paintings of the preceding fifteen years, Gustav Klimt changed what he saw into an idyllic paradise far removed from technology. Thus the narrow country road that leads directly past the forester’s lodge into the Weißenbach valley and to Bad Ischl has not been given any attention. In his pieces of staged nature, Klimt reduces all traces of human activity in favor of green opulence.

A landscape ideal is expressed both in the scene as a whole and in detail. For the painting Forester’s House in Weißenbach on the Attersee II, Klimt thus chose a section of the façade. Its unusual, unique character manifests itself in the differently colored windows, either open or closed, with simple curtains, geranium pots, or a view of the meadow beyond. The building and the patio in front of it are an invitation to linger.

Litzlberg and Unterach

In 1915, Klimt, although living in Weißenbach in the south, returned to his first place of residence, Litzlberg, twice in terms motifs. He devoted himself to the depiction of Litzlberg on the Attersee (c. 1915, private property), dominated by a distant view and the hilly landscape in the background, and around the same time began to paint the Litzlberger Keller on the Attersee (1915/16, private collection), viewed from an elevation. Over the years, the place had developed into a popular rustic eatery that was also a regular haunt of Klimt’s. In the painting, the building appears at the center as a two-dimensional pictorial element, embedded in the nuanced green of the surrounding vegetation. Comparisons between the architecture depicted in the painting and in historical photographs of the site also reveal the extent to which Klimt altered his motifs to make them more cohesive and to formally adapt them to his ideas. For example, he removed a staircase leading to the lake in the painting Litzlberger Keller on the Attersee, so that the house is entirely surrounded by natural setting. In 1916 this work, which was first owned by Otto and Eugenia Primavesi, was completed at the artist’s studio in Hietzing. Klimt informed Otto Primavesi about its completion in a letter from 3 May 1916.