Klimt's work focuses on all aspects of the Art Nouveau master's oeuvre. Visualized through a timeline, Klimt's creative periods are rolled up here, starting with his training, his collaboration with Franz Matsch and his brother Ernst in the "Künstler-Compagnie", the affair surrounding the faculty paintings and his post-fame and the myth that still surrounds this exceptional artist today.

The Golden Knight and Femmes Fatales

Between 1901 and 1903, Gustav Klimt created some of the most important works of his entire oeuvre: the Faculty Paintings, the Beethoven Frieze, and Hope I. In the "Klimt-Kollektive" ["Gustav Klimt Collective Exhibition"], his first solo exhibition at the Vienna Secession, he presented himself as a painter of female portraits, landscapes of square format, and mysterious underwater worlds.

→

Gustav Klimt: The Golden Knight (Life a Battle), 1903, Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art

© Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art, Nagoya

Allegories of Danger

In his allegories dating from the beginning of the 20th century, Klimt dealt primarily with the subject of dark forces, personified by the wicked femme fatale, the knight and his eternal struggle, or the vision of Death. In 1903 he turned to the subject of death and life and the relationship between man and woman in Hope I.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Hope I, 1903/04, National Gallery of Canada

© NGC

Mystic Underwater Worlds

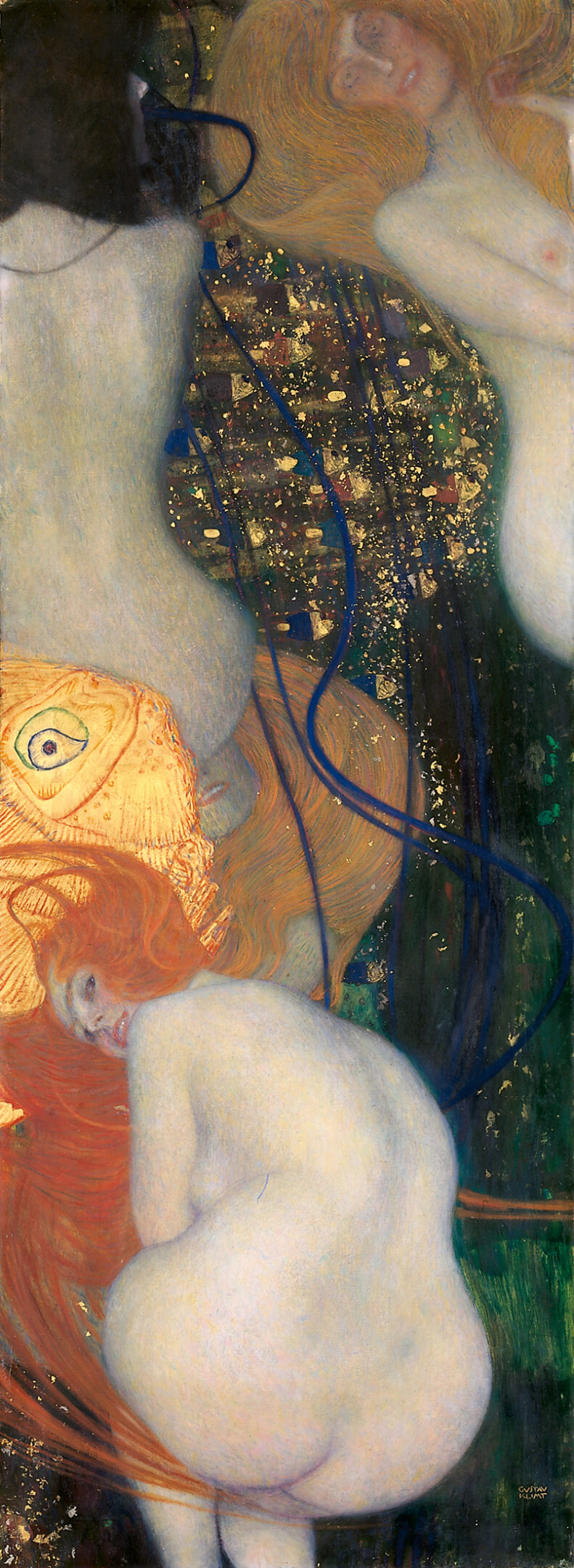

Klimt’s output between 1901 and 1903 is characterized by such fantastic and mystical figures as mermaids, will-o’-the-wisps, and whimsical aquatic creatures.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Goldfish, 1901/02, Kunstmuseum Solothurn, Dübi-Müller-Stiftung

© Kunstmuseum Solothurn

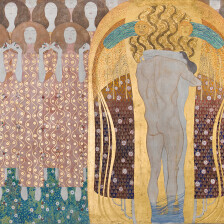

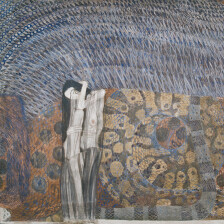

The Beethoven Frieze

On the occasion of the presentation of Max Klinger’s monumental Beethoven statue at the Vienna Secession in 1902, Gustav Klimt conceived the so-called Beethoven Frieze. Painting directly onto three exhibition walls using casein paints, the artist intended his work to lead up to the central sculpture thematically, thus contributing with the frieze to what was to become a Gesamtkunstwerk or universal work of art. Although Ludwig van Beethoven is mentioned in the title, the composer is not depicted.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: The Beethoven Frieze (The Suffering of Weak Mankind, The Well-Armed Strongman), 1901/02, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

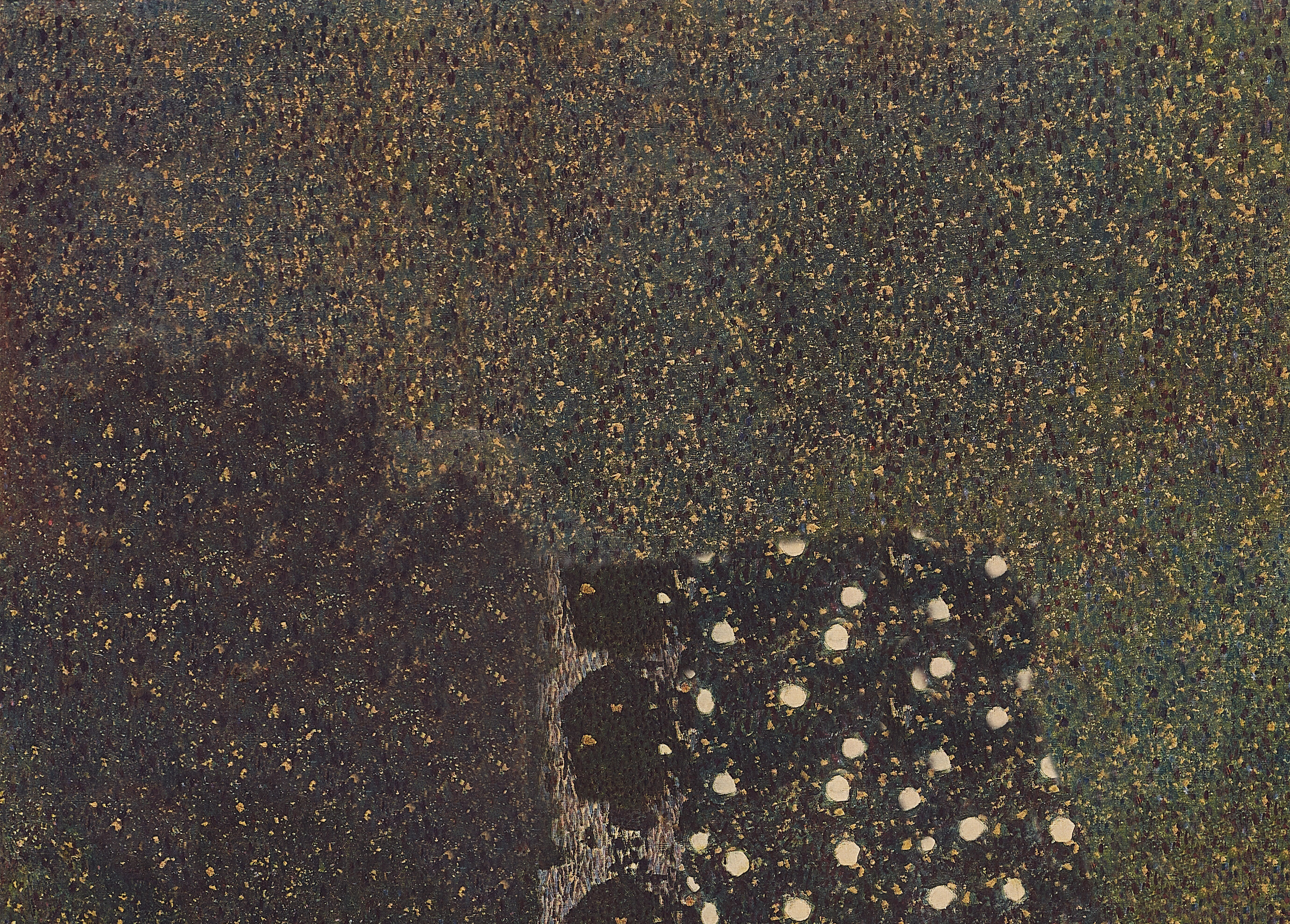

Trees and Forests

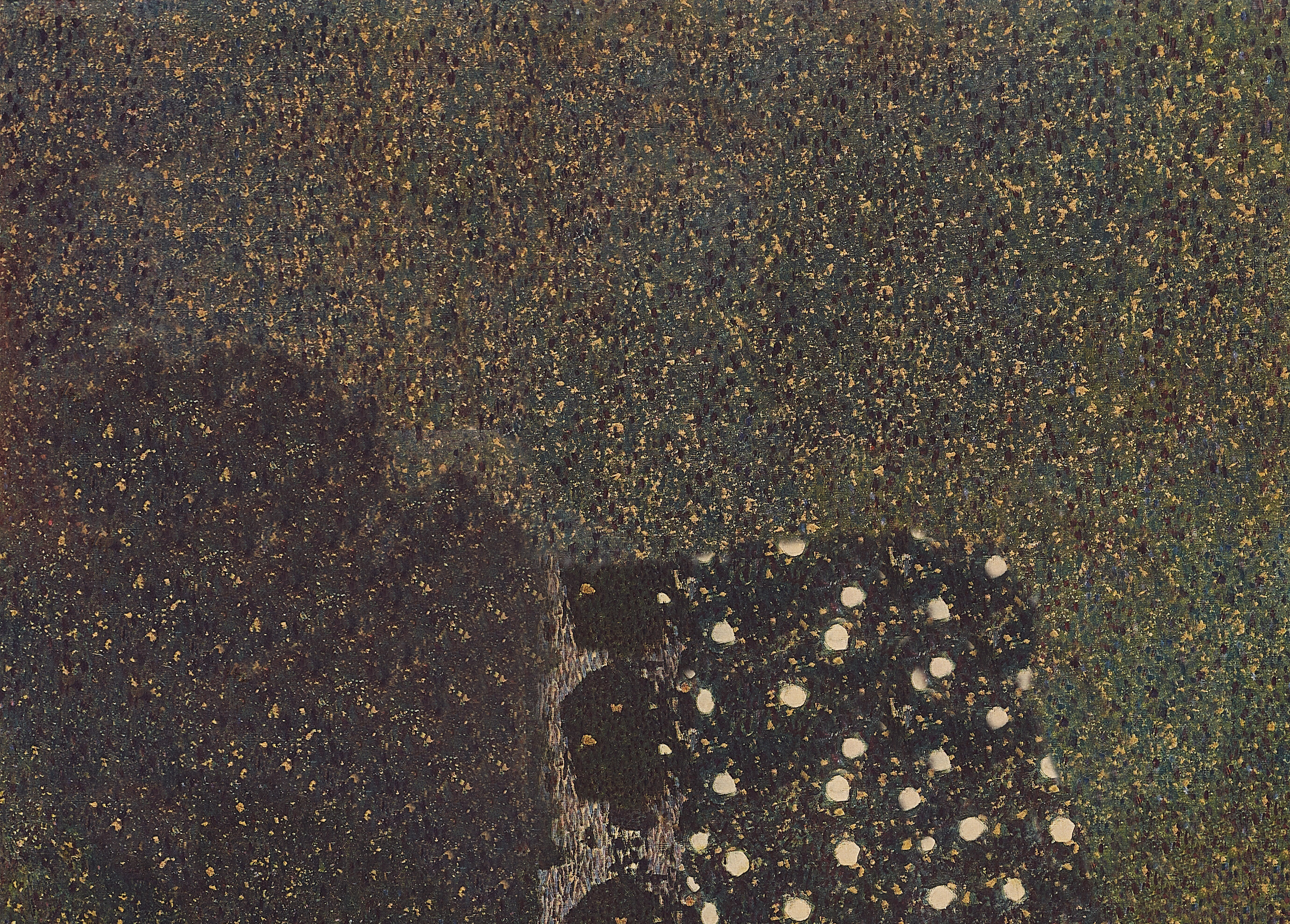

Having arrived at a personal approach to landscape painting between 1898 and 1900, Klimt made use of the motif of the forest view for stylistic experiments in the years between 1901 and 1903. A phase of Post-Impressionism and Pointillism was followed by the artist’s turn toward flatness.

To the chapter

→

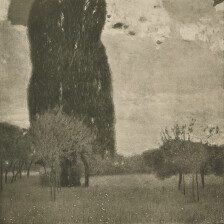

Gustav Klimt: The Large Poplar II (Gathering Storm), 1902/03, Leopold Museum

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

Viennese Society Portraits

From 1900 onwards, Gustav Klimt increasingly established himself as a portraitist of the upper echelons of Viennese society. Above all, his ability to capture the latest fashion trends on canvas in a gossamer painting style quickly became his personal signature. Successively introducing more ornamentation in his portraits, Klimt already anticipated the two-dimensionality of his subsequent works.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Emilie Flöge, 1902/03, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Faculty Paintings. Medicine and Jurisprudence

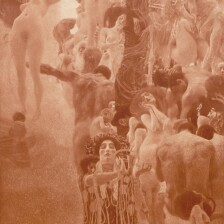

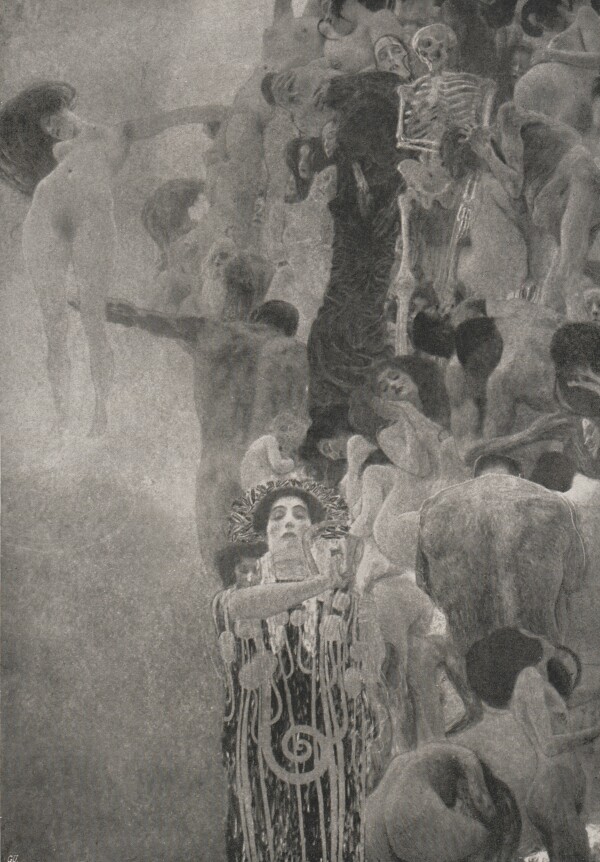

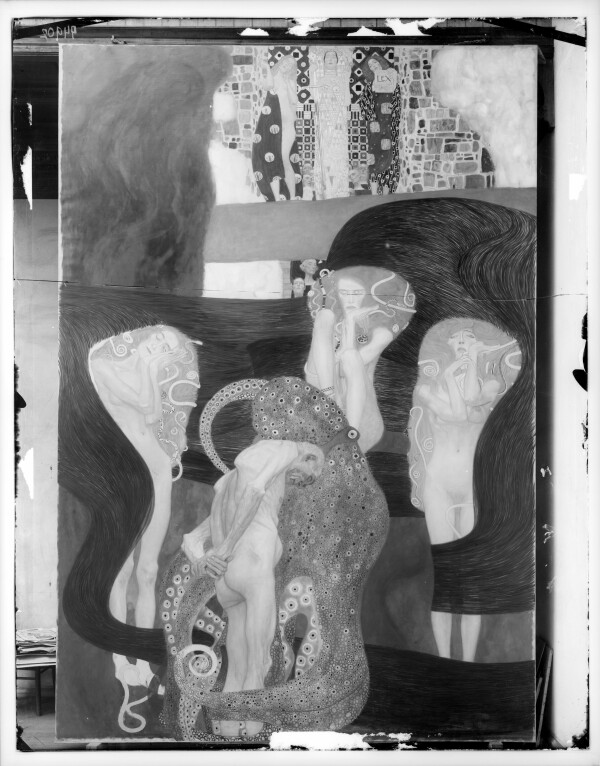

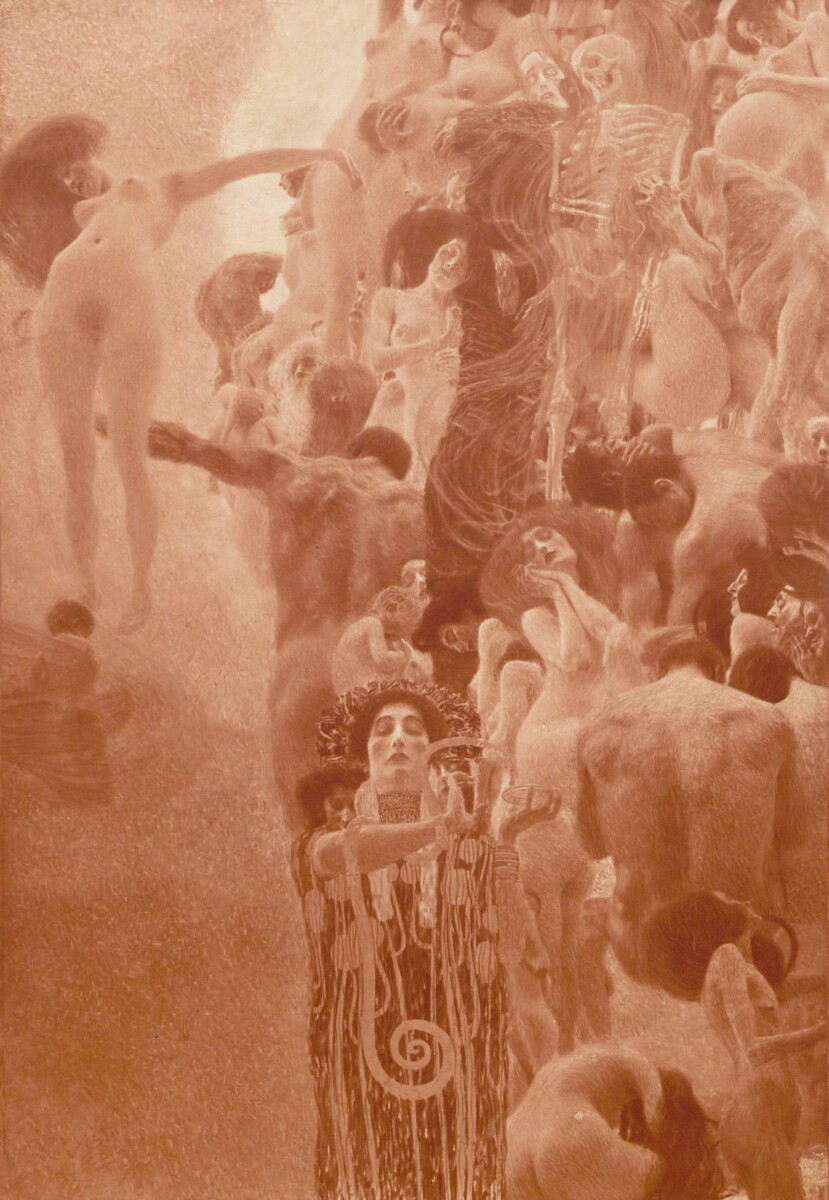

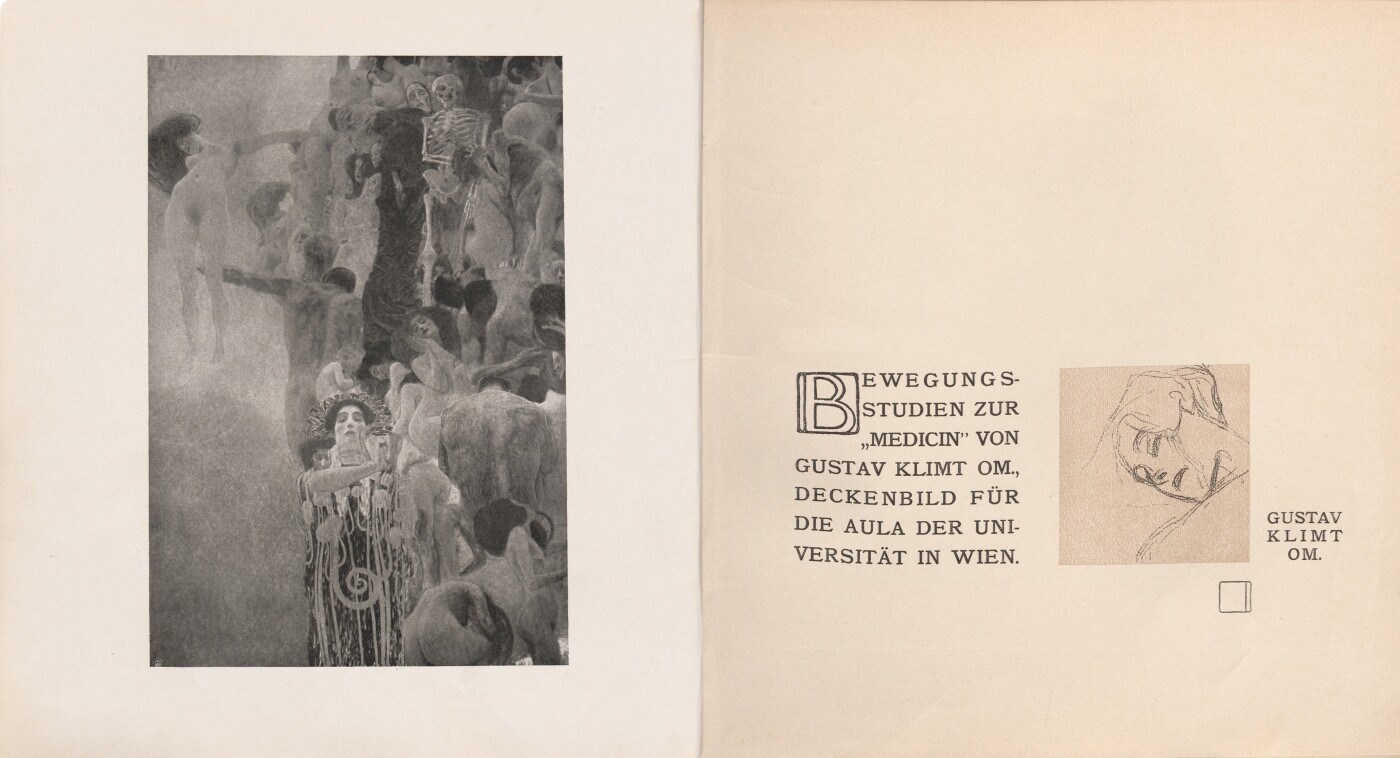

Between 1900 and 1903, Gustav Klimt worked intently on the two Faculty Paintings Medicine and Jurisprudence for the auditorium of Vienna University. When the paintings were first presented in 1901 and 1903, they caused scandals, as the Faculty Painting Philosophy had done in 1900. Following numerous alterations and additions carried out until 1907, the works were destroyed in fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Medicine, 1900-1907, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt, in: Kunstverlag Hugo Heller (Hg.): Das Werk von Gustav Klimt, Vienna - Leipzig 1918.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

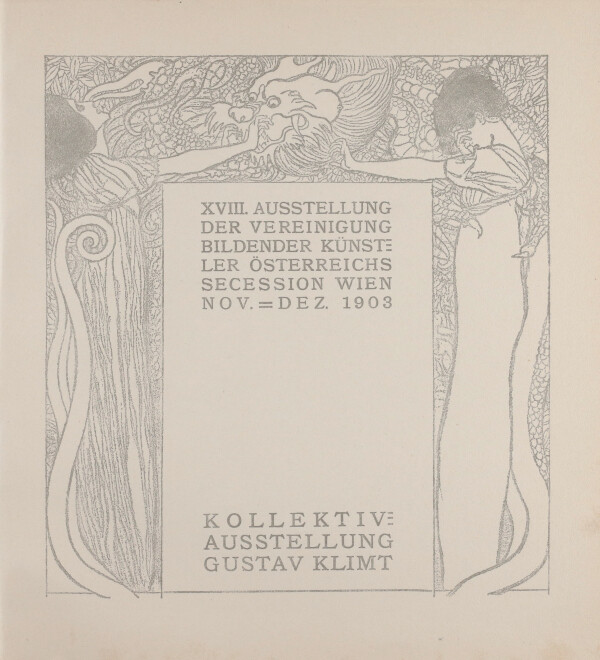

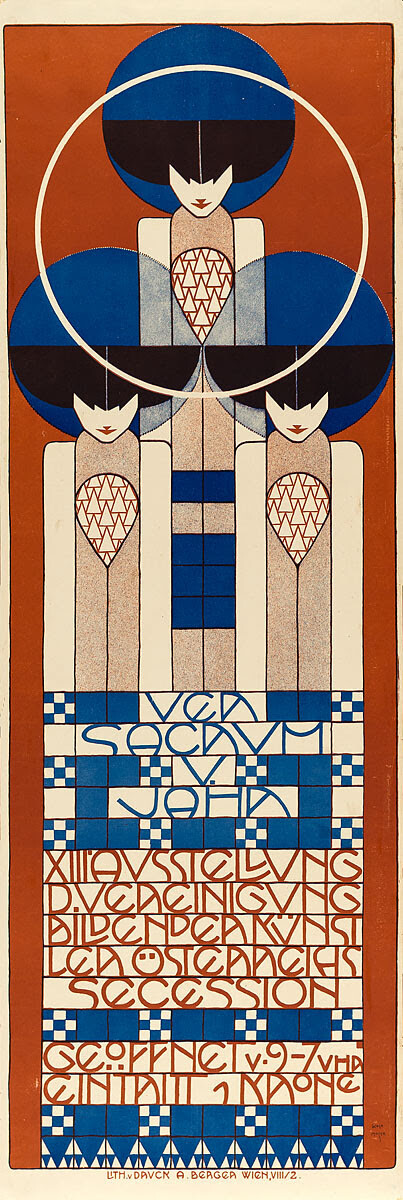

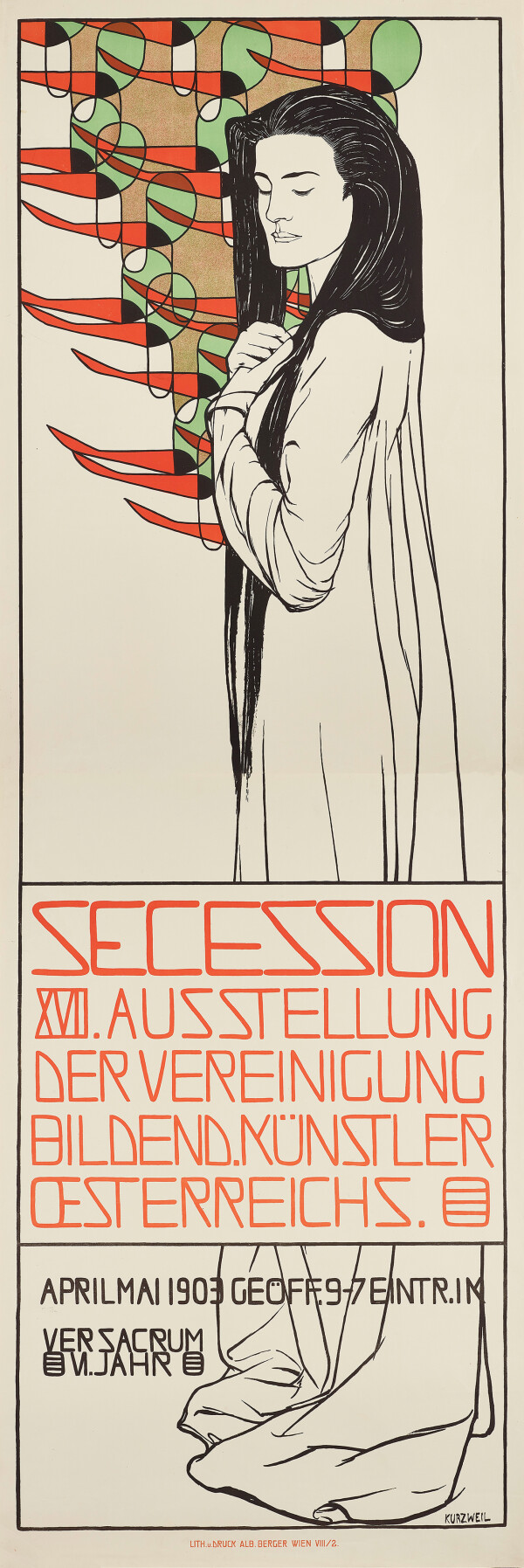

Klimt-Kollektive

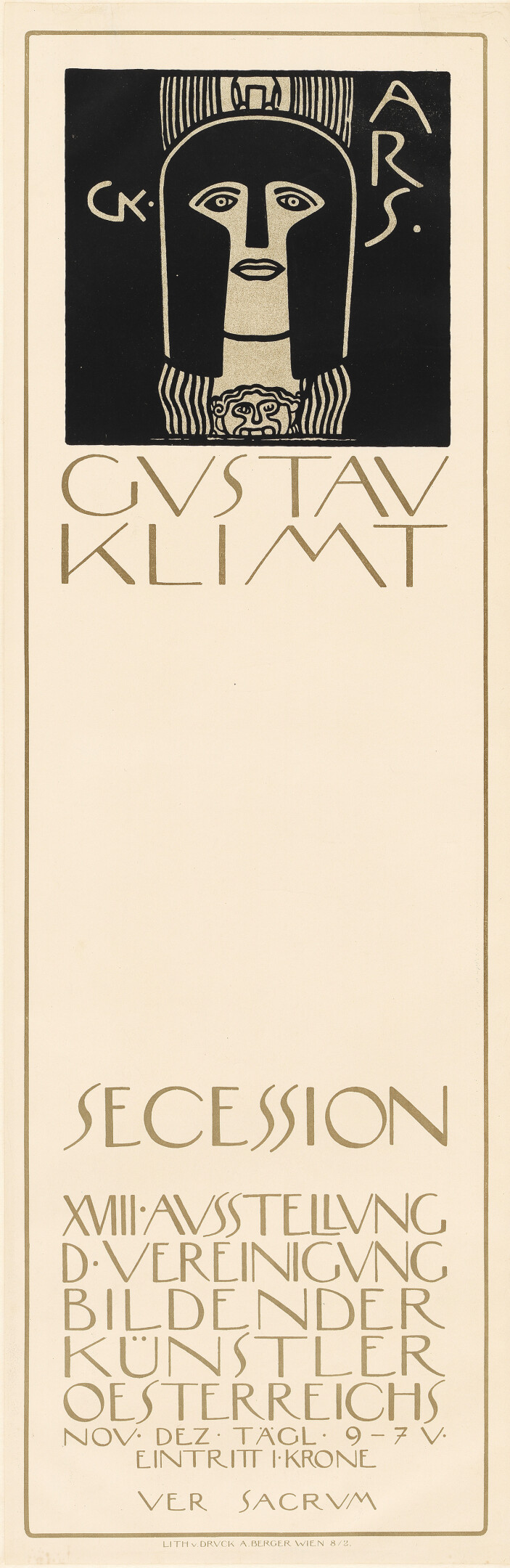

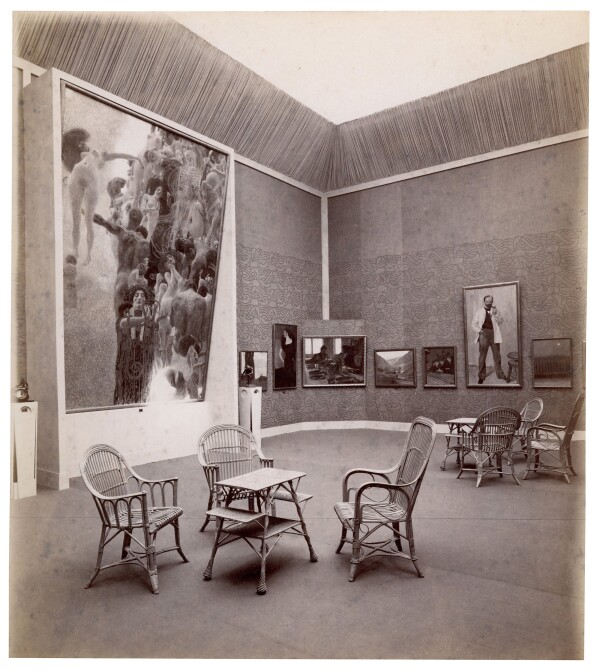

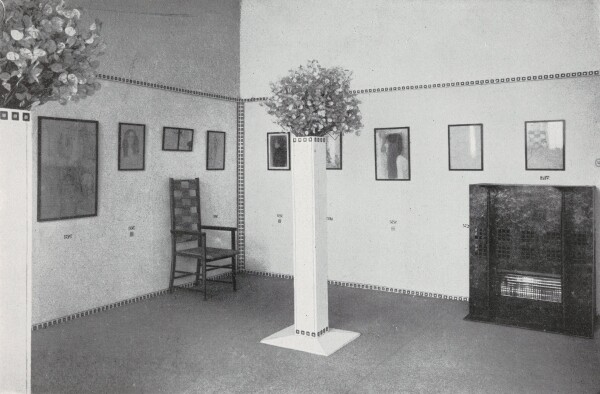

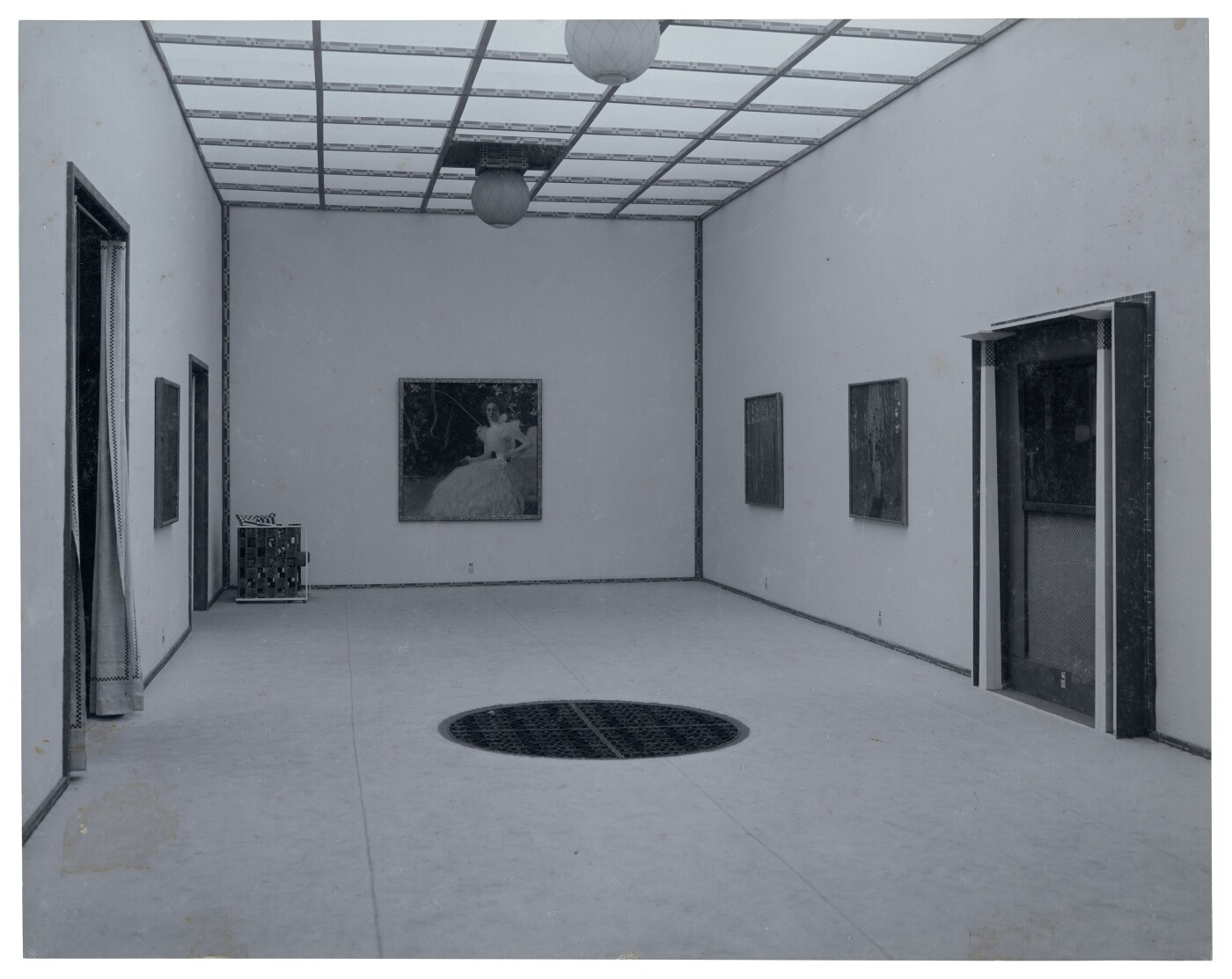

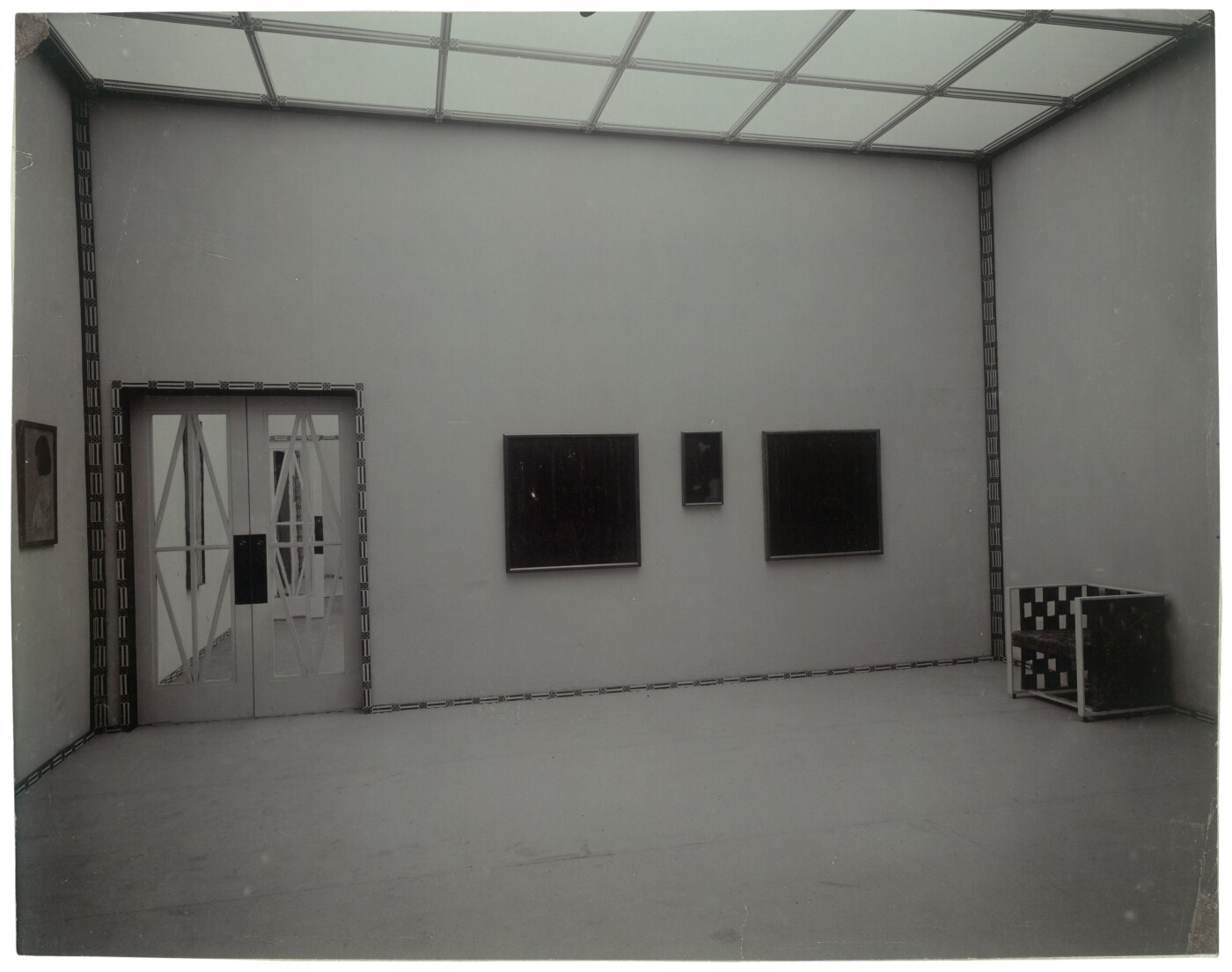

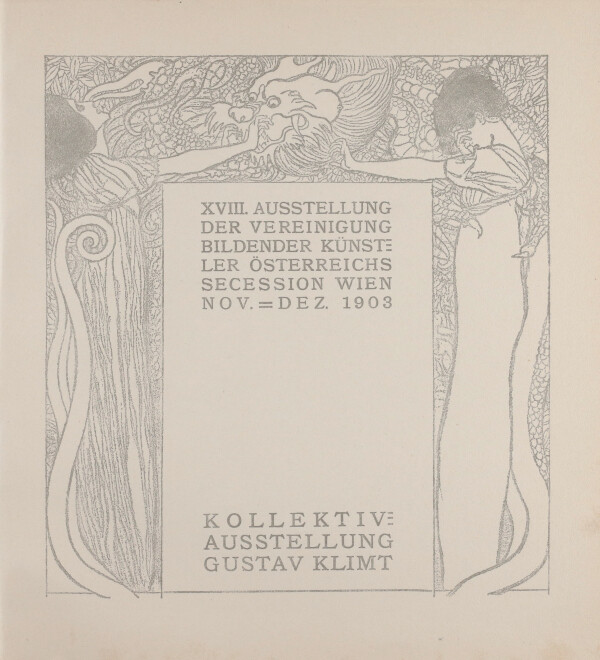

The XVIII. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession Wien [13th Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists Vienna Secession] presented a comprehensive monographic exhibition dedicated to its former president Gustav Klimt. Comprising as many as 80 works, the show offered a survey of the artist’s works created to this date. For the first time, the Faculty Paintings Philosophy, Medicine, and Jurisprudence were displayed together in an exhibition.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Poster of the XVIII Secession Exhibition (Klimt Collective), 1903, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

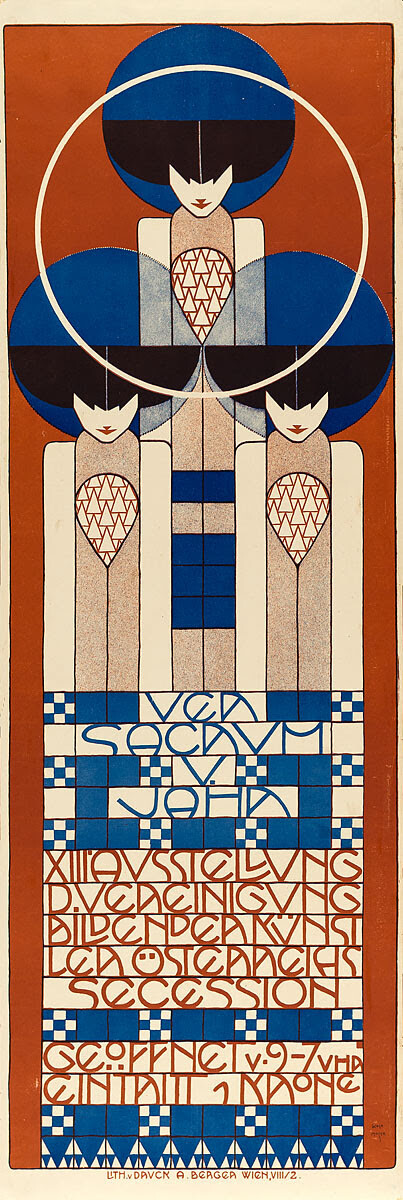

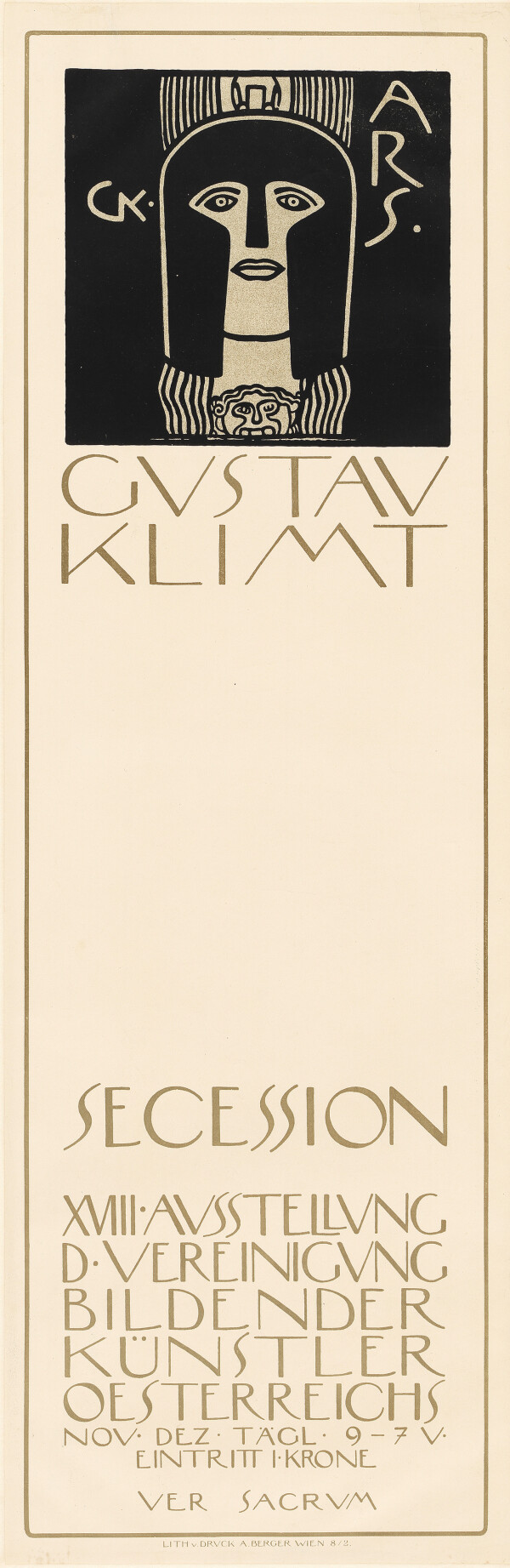

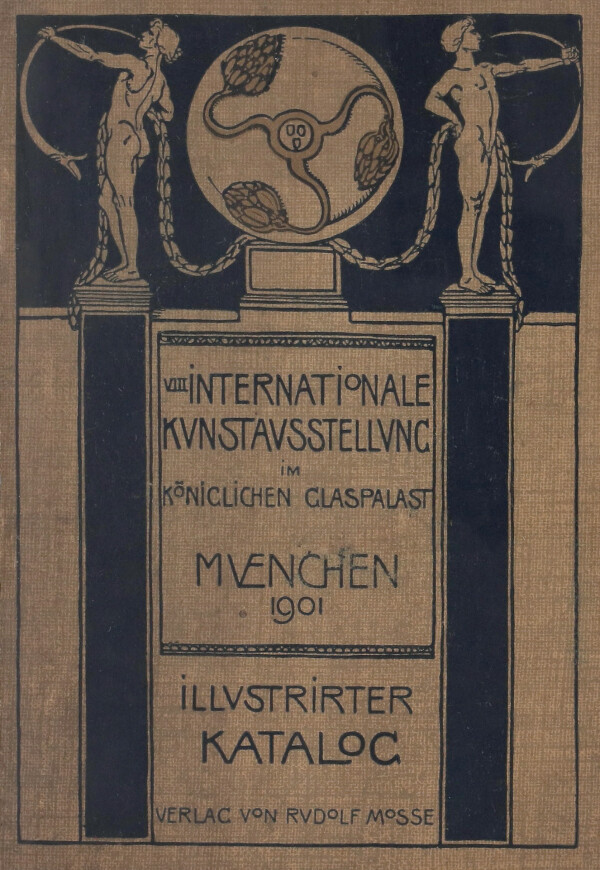

Exhibition Activity

Between 1901 and 1903, Klimt took part in more than twenty exhibitions. The Faculty Painting of Medicine, which was presented in 1901, caused a scandal but at the same time brought about a lively interest in Klimt as an artist both at home and abroad. The highlight during these three years full of exhibitions was certainly the “Kollektiv-Ausstellung Gustav Klimt” [“Gustav Klimt Collective Exhibition”] in Vienna in 1903.

To the chapter

→

Kolo Moser: Poster of the XIII Secession Exhibition, 1902, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg (MK&G)

© Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg

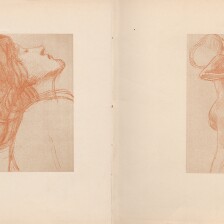

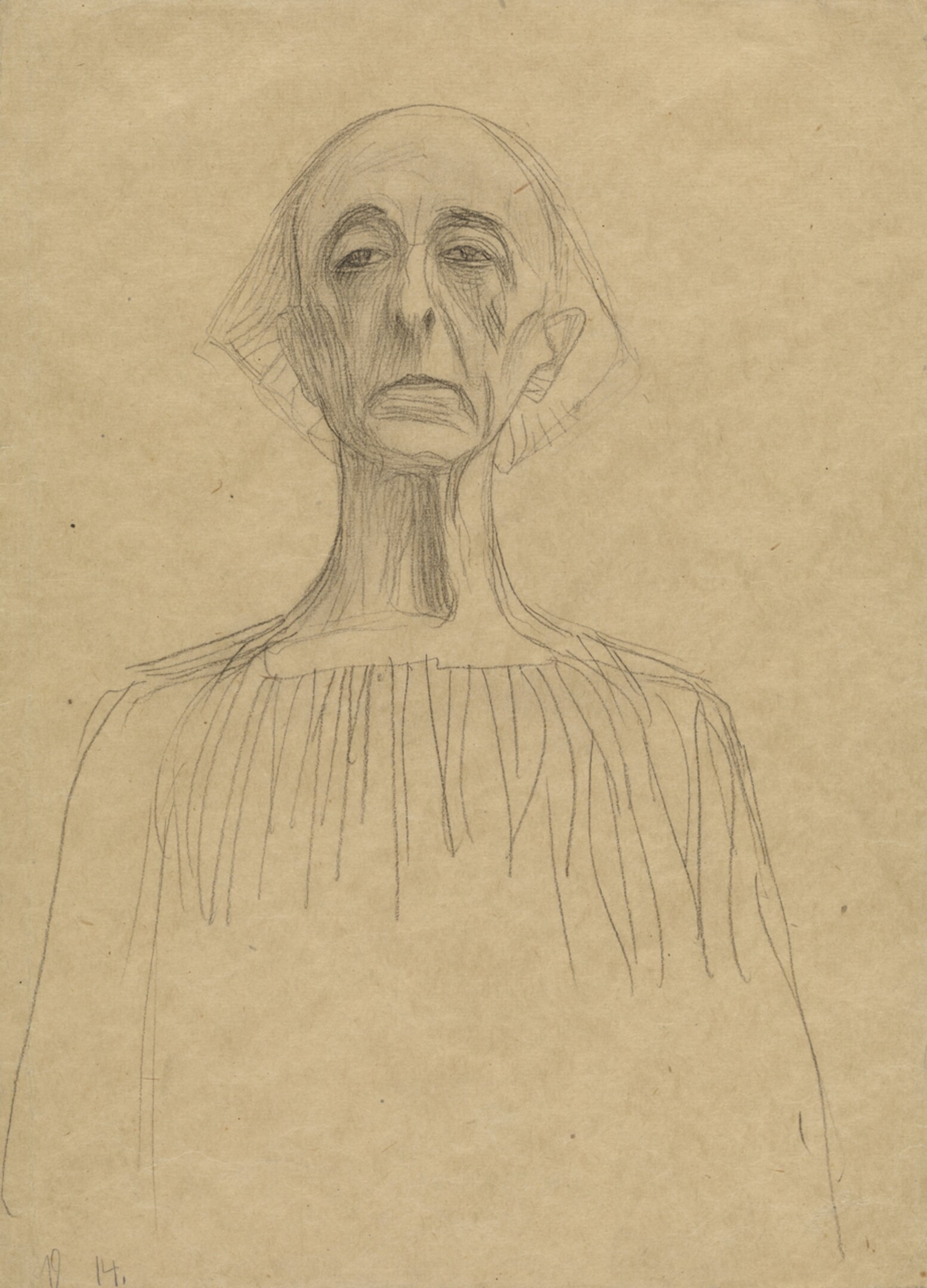

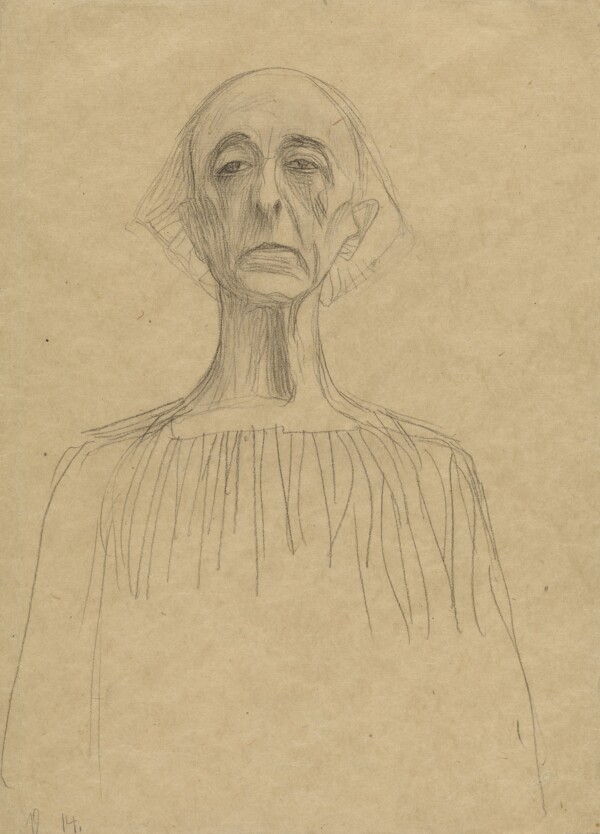

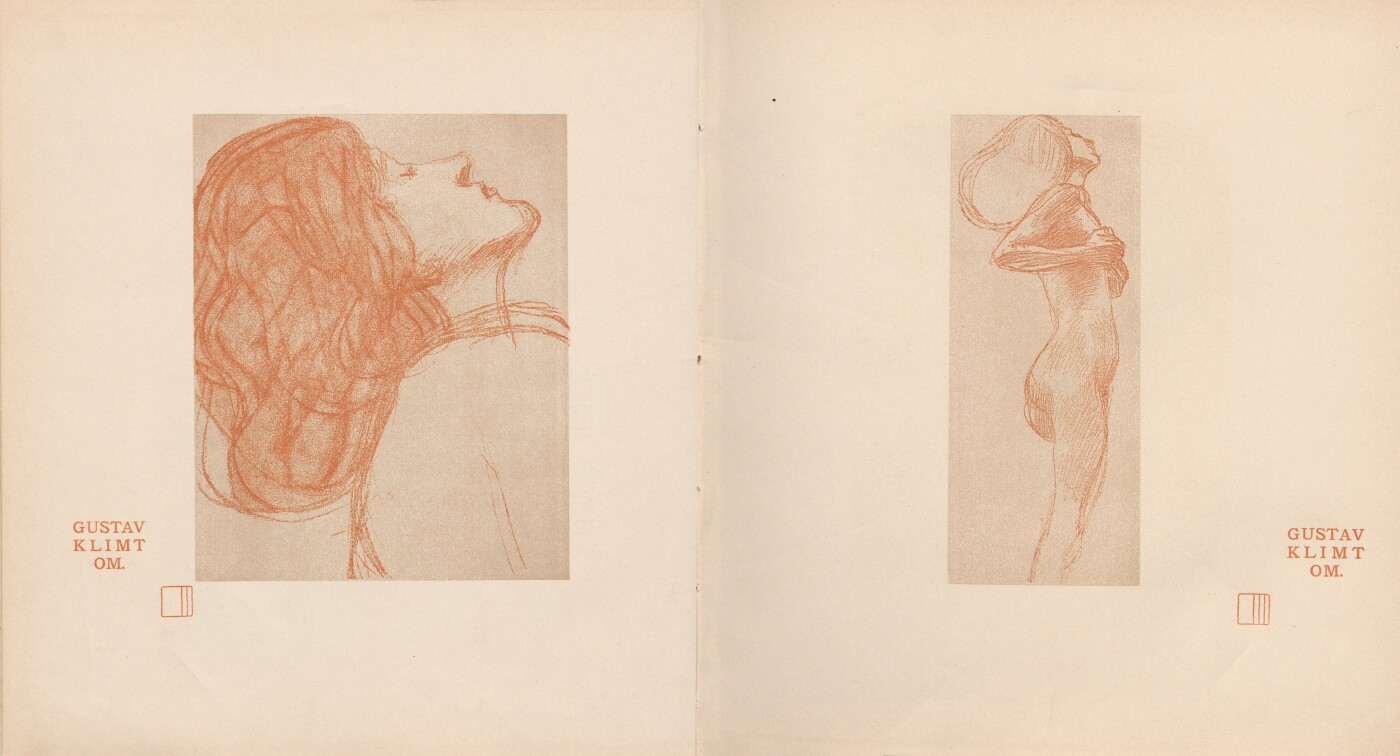

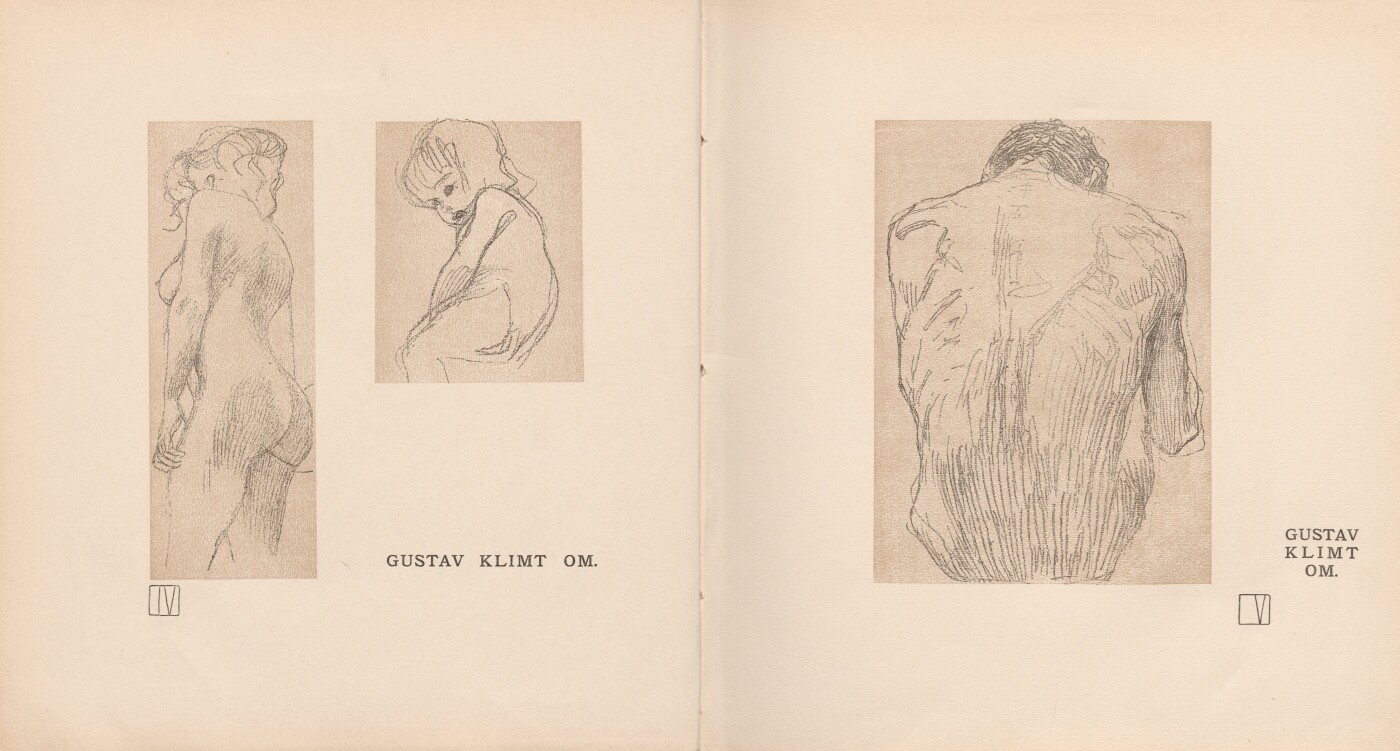

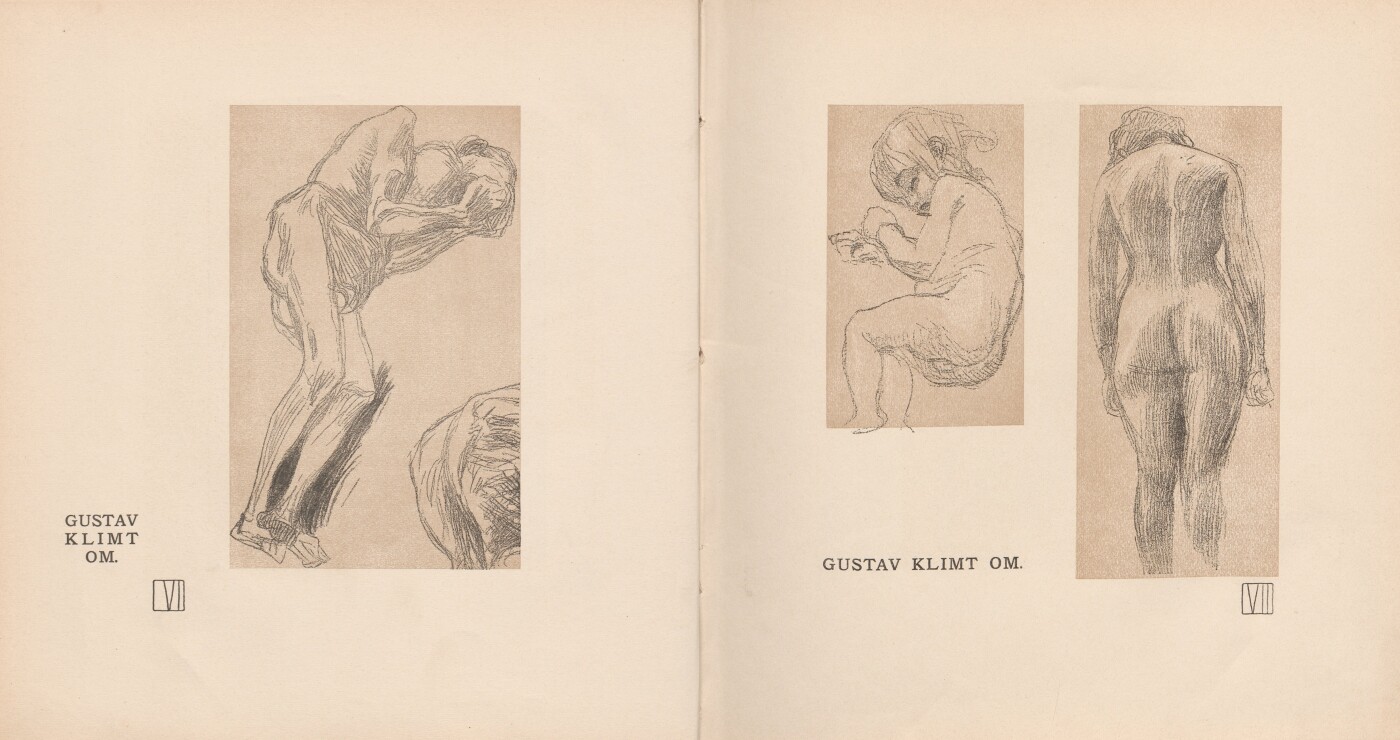

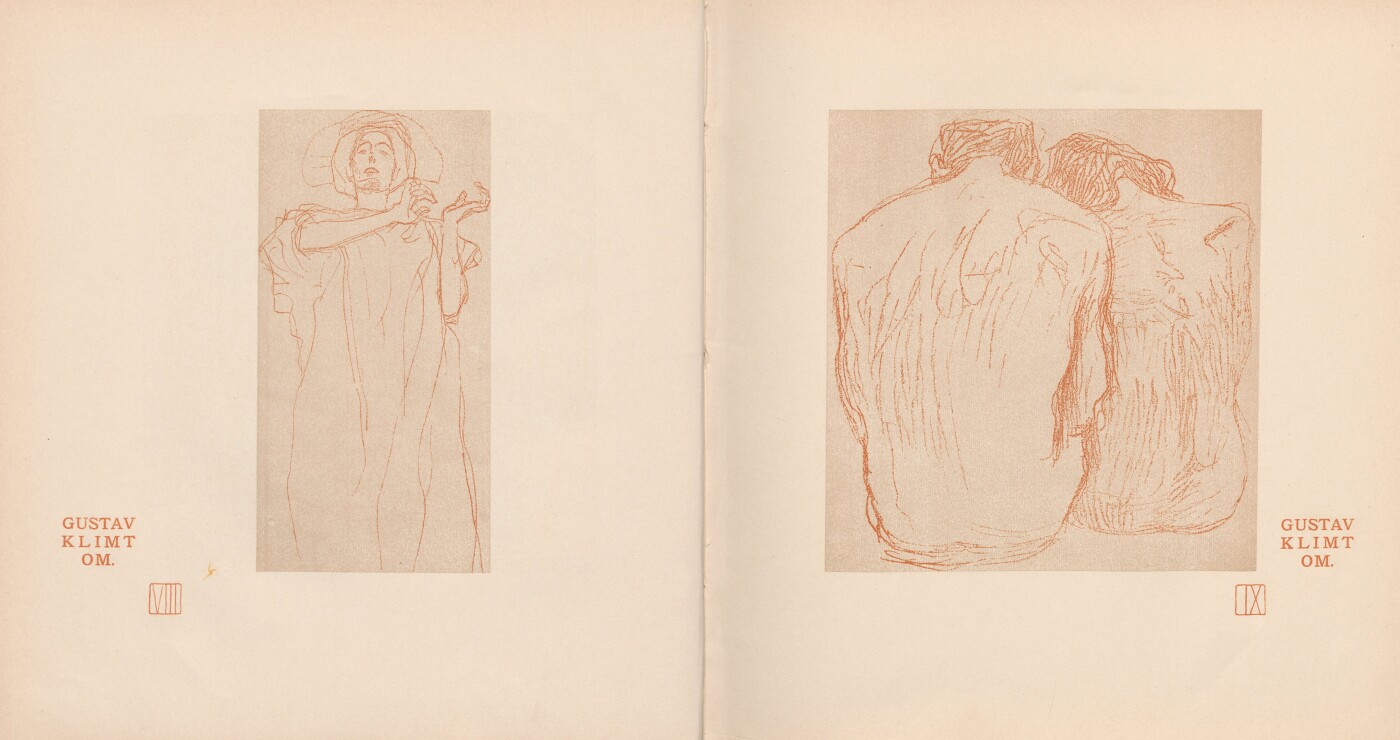

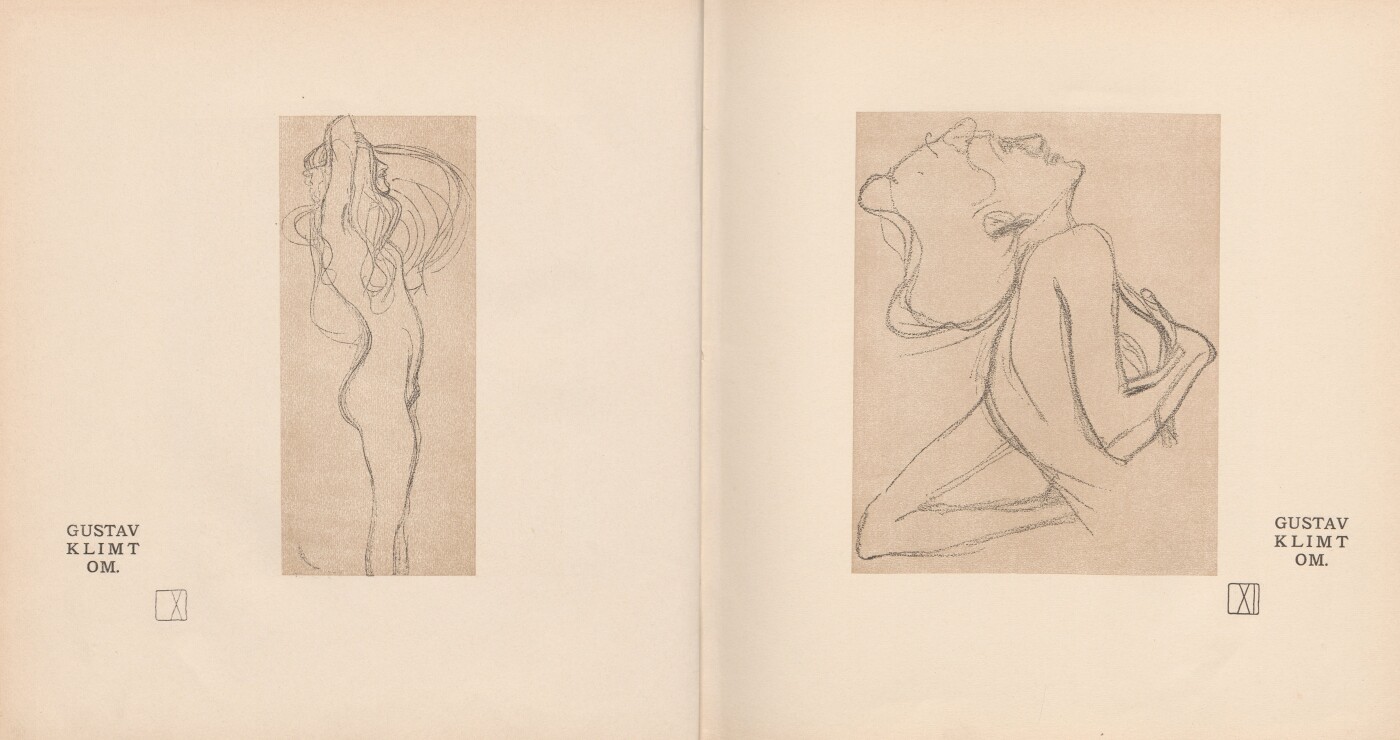

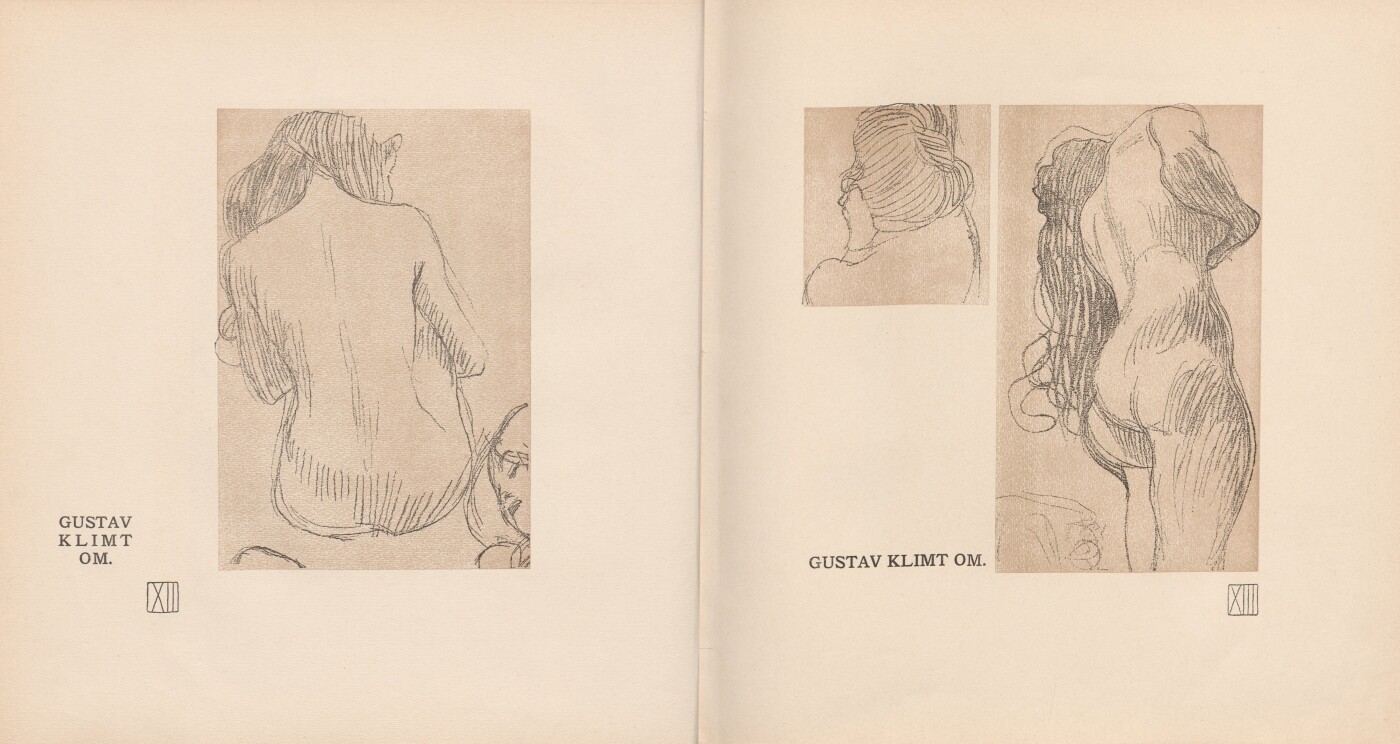

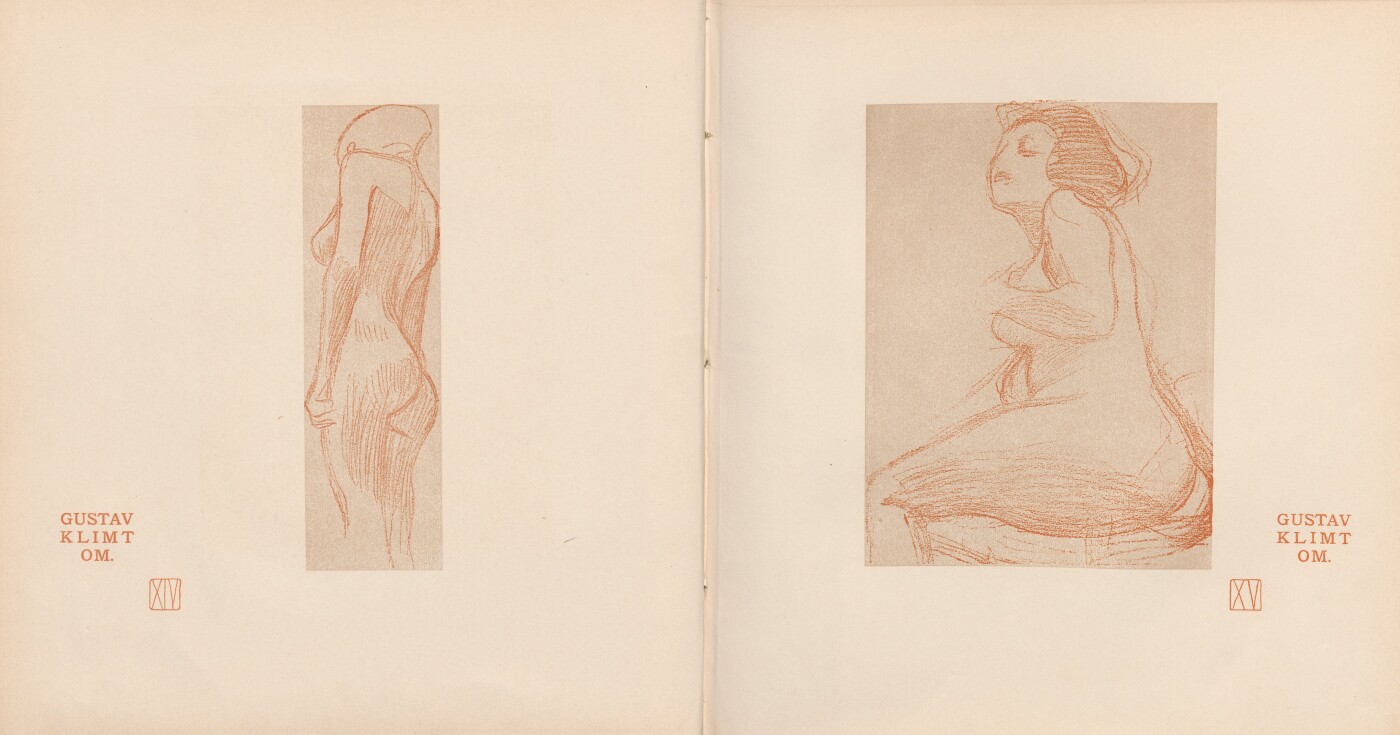

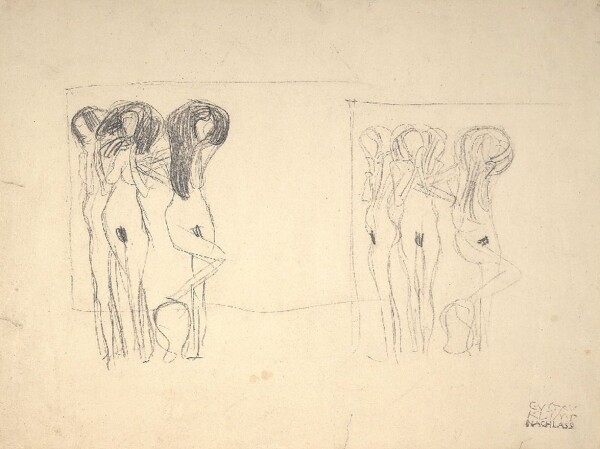

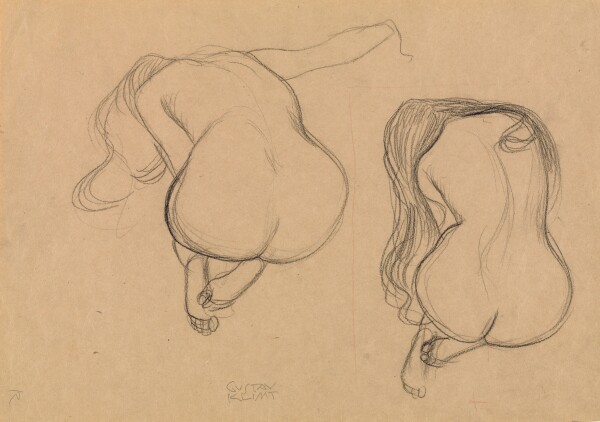

Drawings

Shortly after 1900, Klimt expanded his previously preferred medium of charcoal to include a pointed pencil and polychromy in the form of colored pencils. Beautifully curved outlines and parallel hatching became increasingly relevant. Using nude models, he studied postures and emotions in coherent series.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Bust portrait of a man from the front, 1901-1903, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

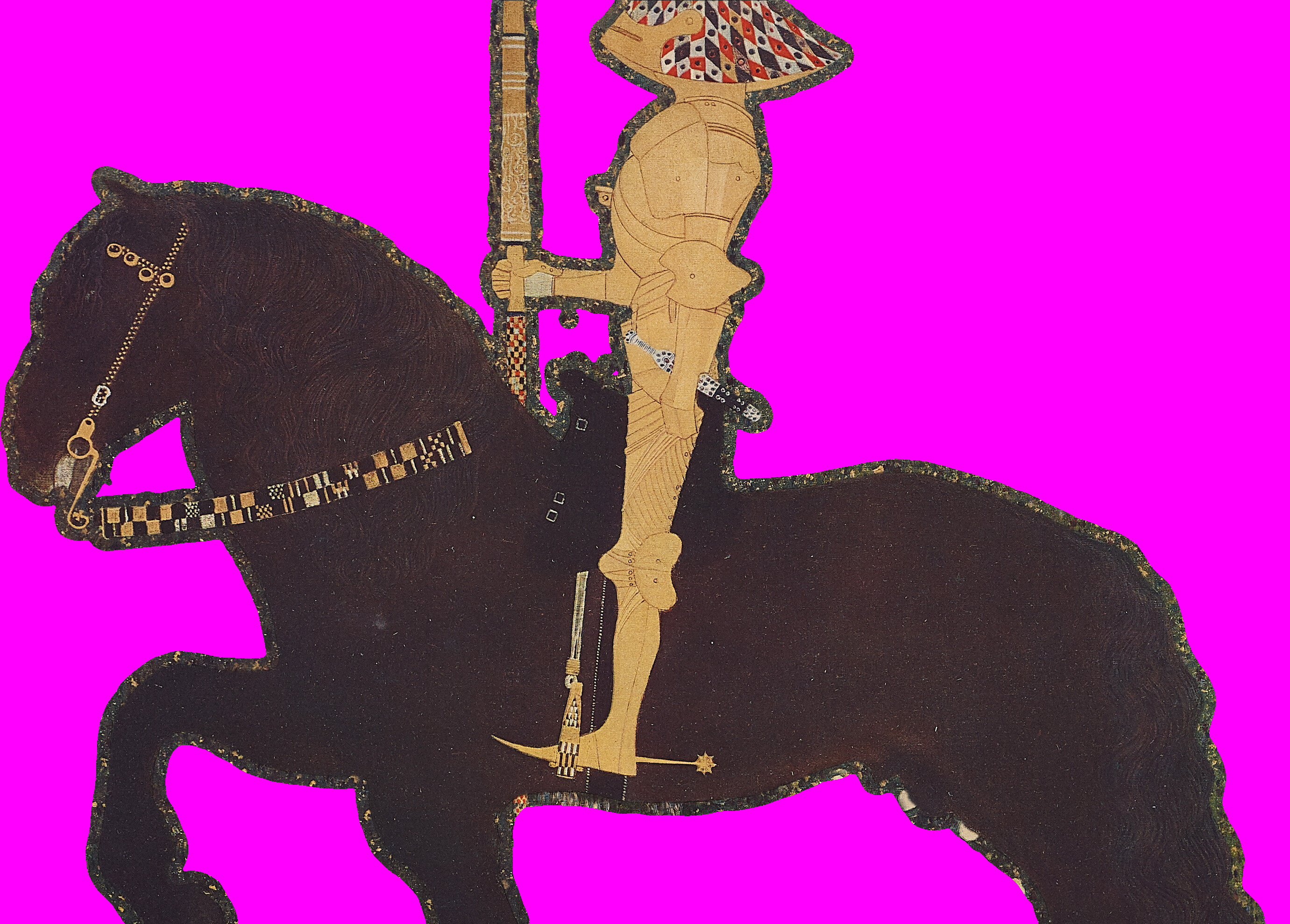

The Golden Knight and Femmes Fatales

Between 1901 and 1903, Gustav Klimt created some of the most important works of his entire oeuvre: the Faculty Paintings, the Beethoven Frieze, and Hope I. In the "Klimt-Kollektive" ["Gustav Klimt Collective Exhibition"], his first solo exhibition at the Vienna Secession, he presented himself as a painter of female portraits, landscapes of square format, and mysterious underwater worlds.

→

Gustav Klimt: The Golden Knight (Life a Battle), 1903, Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art

© Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art, Nagoya

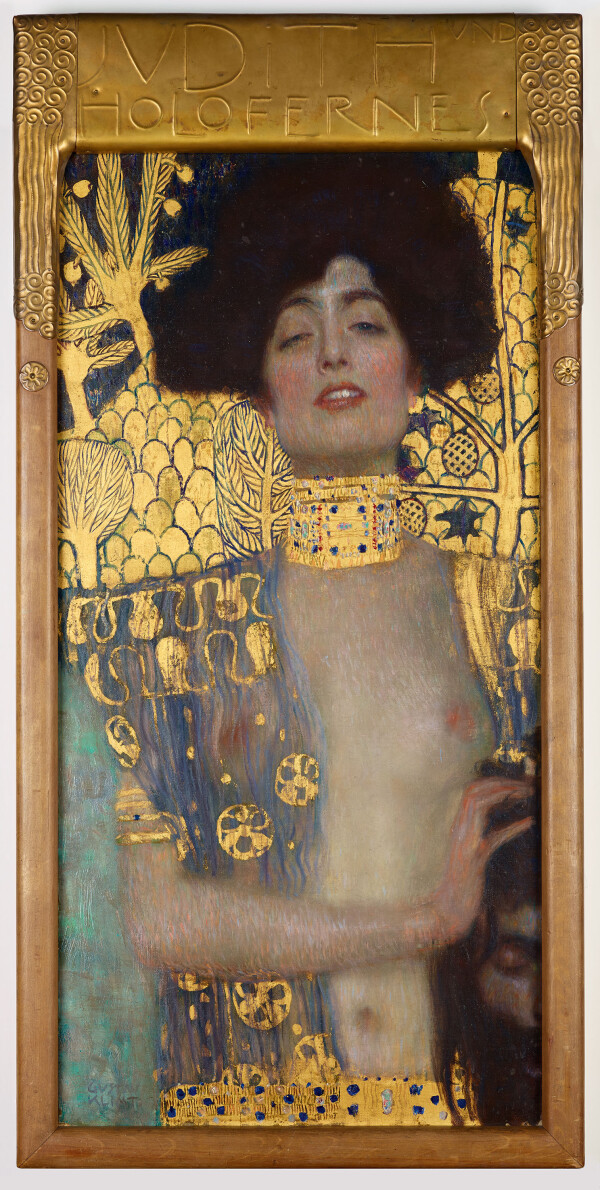

Allegories of Danger

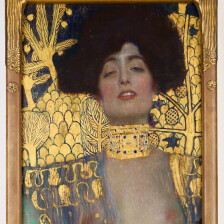

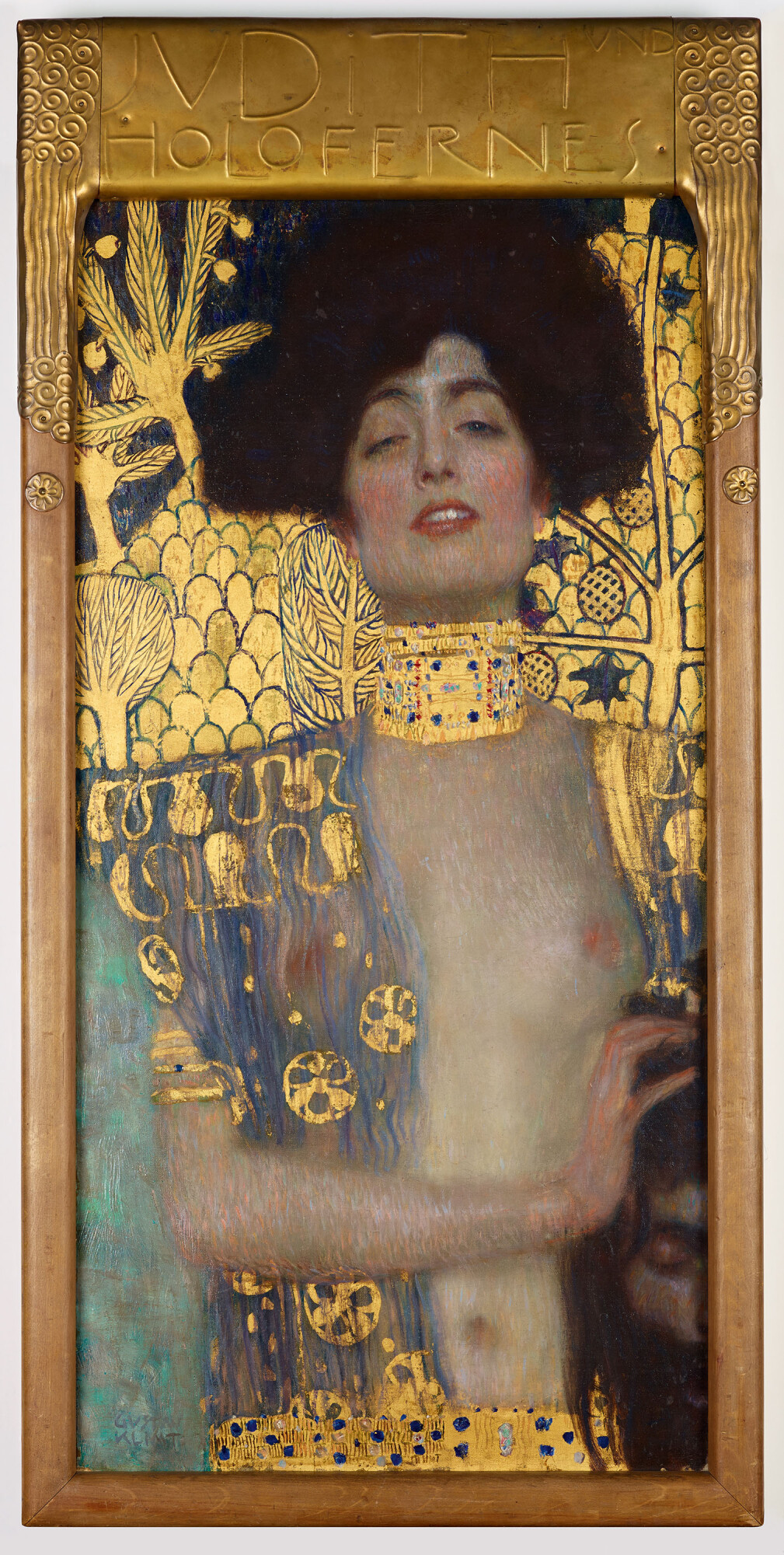

Gustav Klimt: Judith I, 1901, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

In his allegories dating from the beginning of the 20th century, Klimt dealt primarily with the subject of dark forces, personified by the wicked femme fatale, the knight and his eternal struggle, or the vision of Death. In 1903 he turned to the subject of death and life and the relationship between man and woman in Hope I.

Judith I

The painting Judith I (1901, Belvedere, Vienna) can be seen as a prime example of women shown as femmes fatales. It shows the heroine from the Old Testament with the head of the cruel commander Holofernes embedded in a shiny golden composition with oriental pictorial elements inspired by Assyrian reliefs. The focus is entirely on the female protagonist. The head of Holofernes, half of which is overlapped by the margin of the picture, has been assigned the function of a mere attribute. The feminine aspect is dominant, while the male component is literally marginalized.

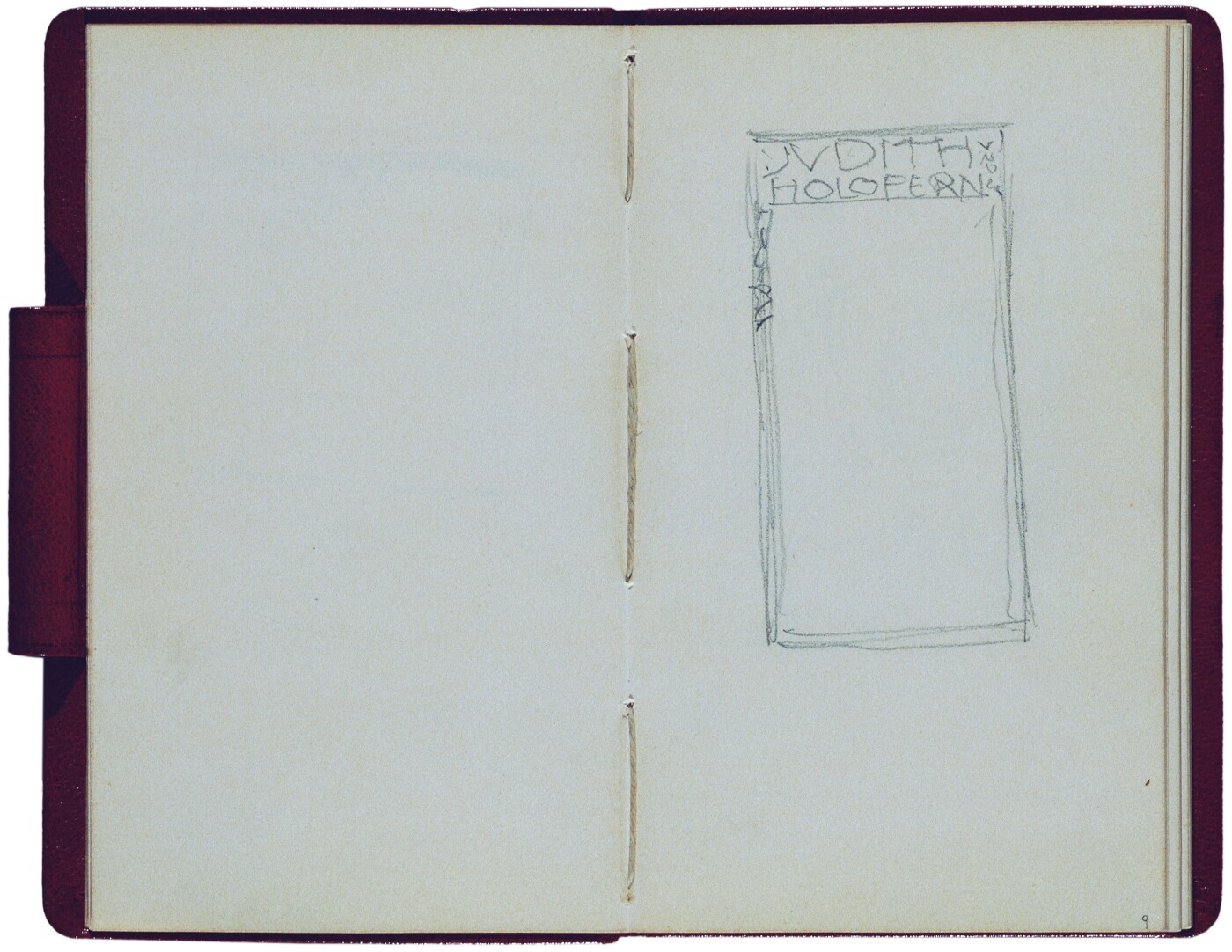

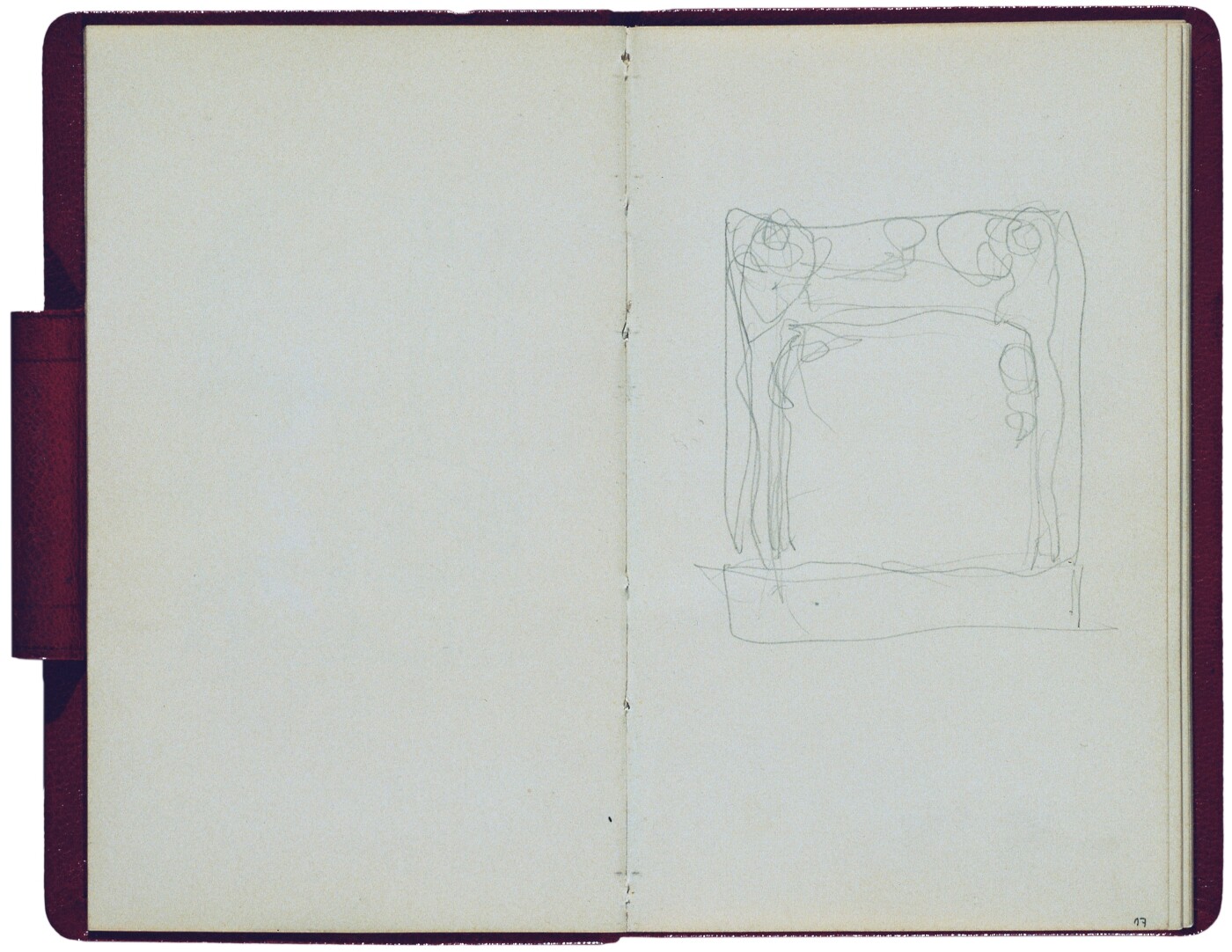

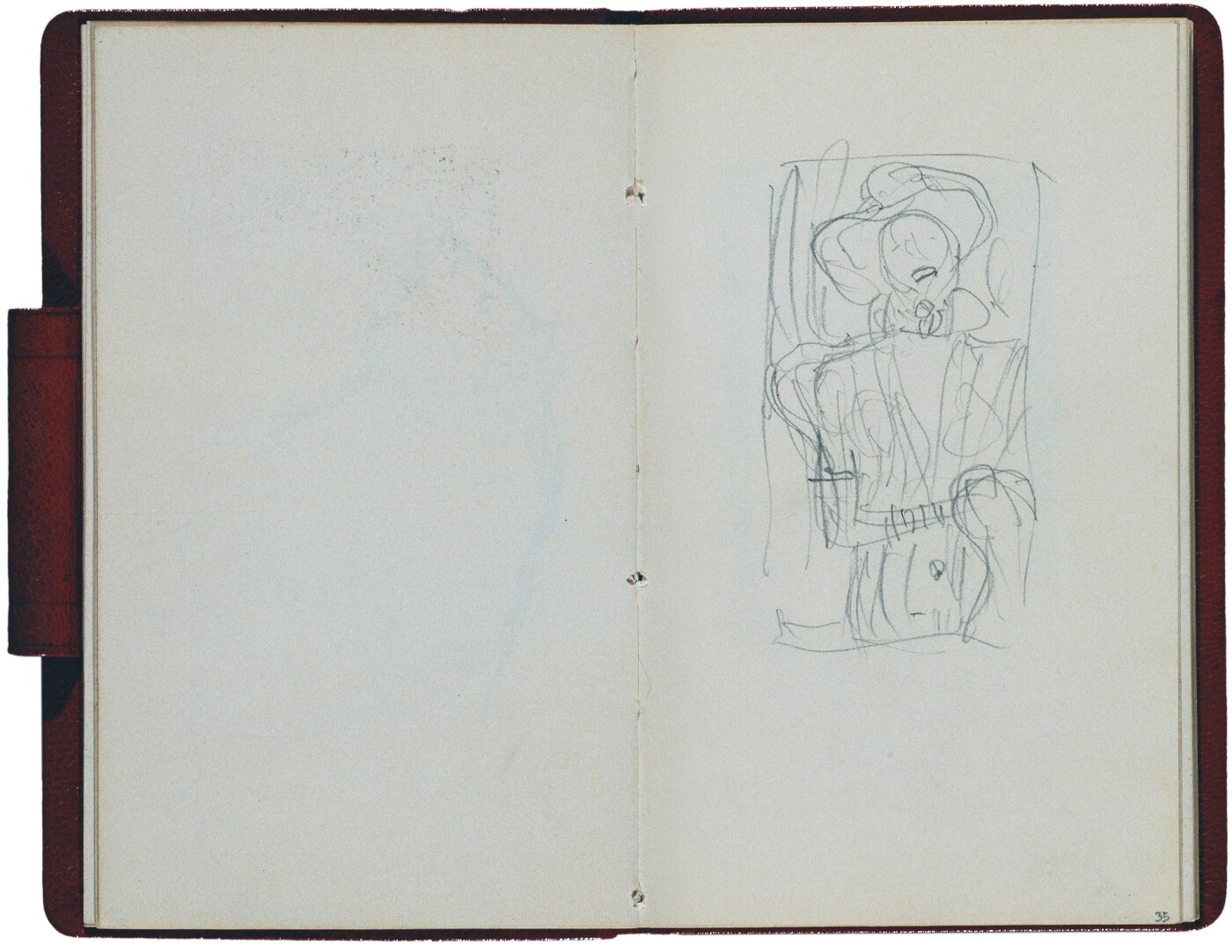

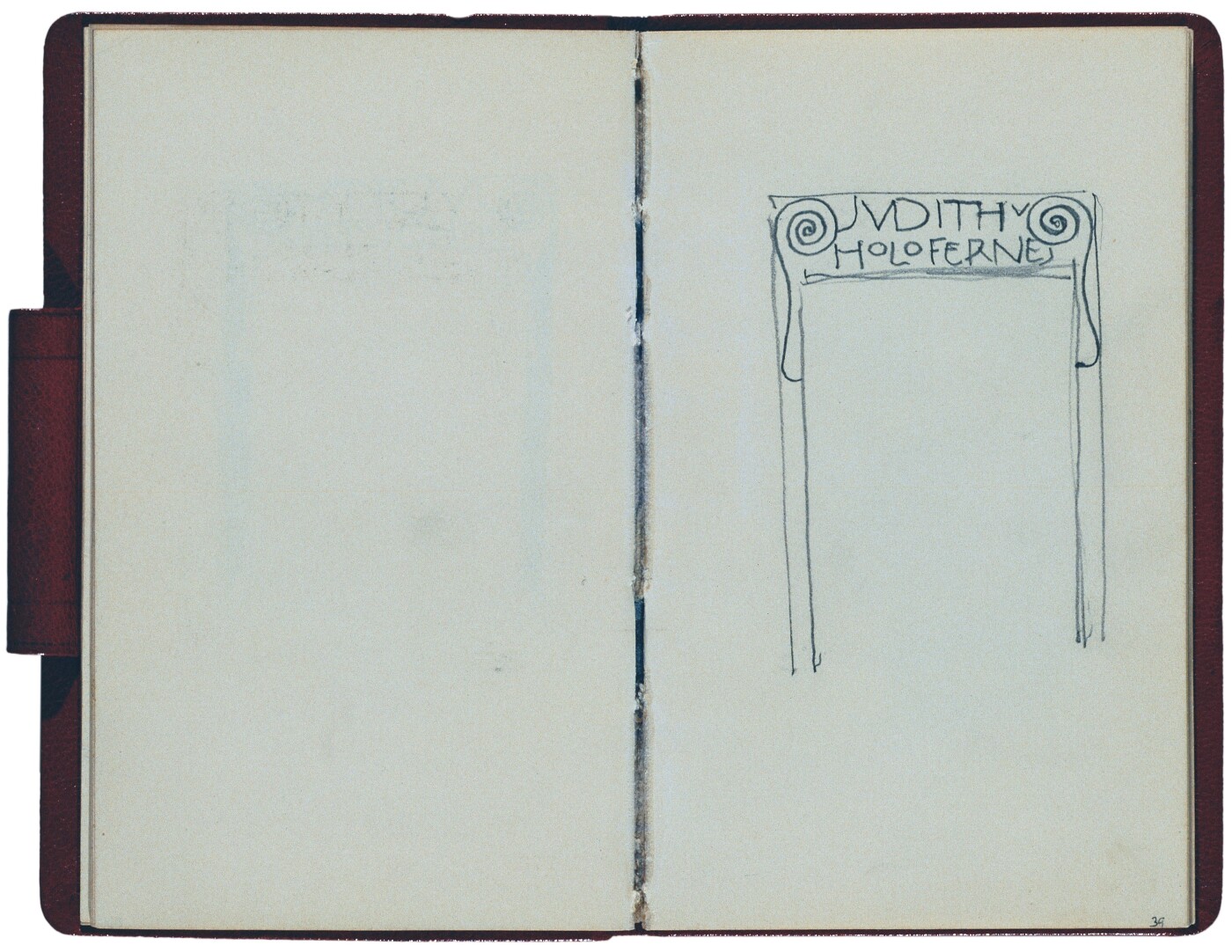

The frame, designed by Klimt and inscribed “JUDITH UND HOLOFERNES,” can be seen as part of the composition in the sense of a Gesamtkunstwerk or total work of art. It was executed by Georg Klimt, the painter’s brother, who was a successful metal sculptor. Despite the fact that the protagonist can clearly be identified as Judith thanks to the inscription on the frame, her ambivalent portrayal as a seductive, erotic femme fatale led to her sometimes also being interpreted as Salome – virtuous Judith’s sinful counterpart in the Bible. The art critic Ostini thus remarked:

“For the splendid biblical figure of the slayer of Holofernes, this face is much too lustful and much too perverse. There is a slackness to it that comes not from the act [!] but from the pleasure.”

Klimt’s depiction thus oscillates between triumphant, heroic patriot and sexually dominant, mantis-like killer of men. Sketches in the so-called Red Sketchbook (1898, Belvedere, Vienna), which was once in the possession of Sonja Knips, show that Klimt deliberately heightened the aspect of eroticism by emphasizing the lips and navel. What is crucial here is above all the transposition of time-honored iconographic themes and their simultaneous incorporation in contemporary history. As early as 1903, Felix Salten recognized Klimt’s ability to update mythological figures by seeing in Klimt’s Judith a beautiful Jewish ‘jourdame.’”

Individual Pages from the Red Sketchbook

-

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: Sonja Knips' red sketchbook, 1898, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

With his interpretation of Judith, Klimt followed in the footsteps of various writers and artists of the fin de siècle – above all Friedrich Hebbel – who associated their idea of the modern, sexual woman dominating men with the figure of Judith. With his Judith I, Klimt positioned himself stylistically in the midst of the international discourse around Symbolism and Décadence. One of his inspirations from the field of painting was certainly Franz Stuck’s series revolving around his work The Sin (c. 1893, Neue Pinakothek, Munich), in which Stuck establishes the principle of the seductive woman who, in her obvious sexuality, is also always surrounded by an air of danger. This is picked up by Klimt in his own interpretation of Judith.

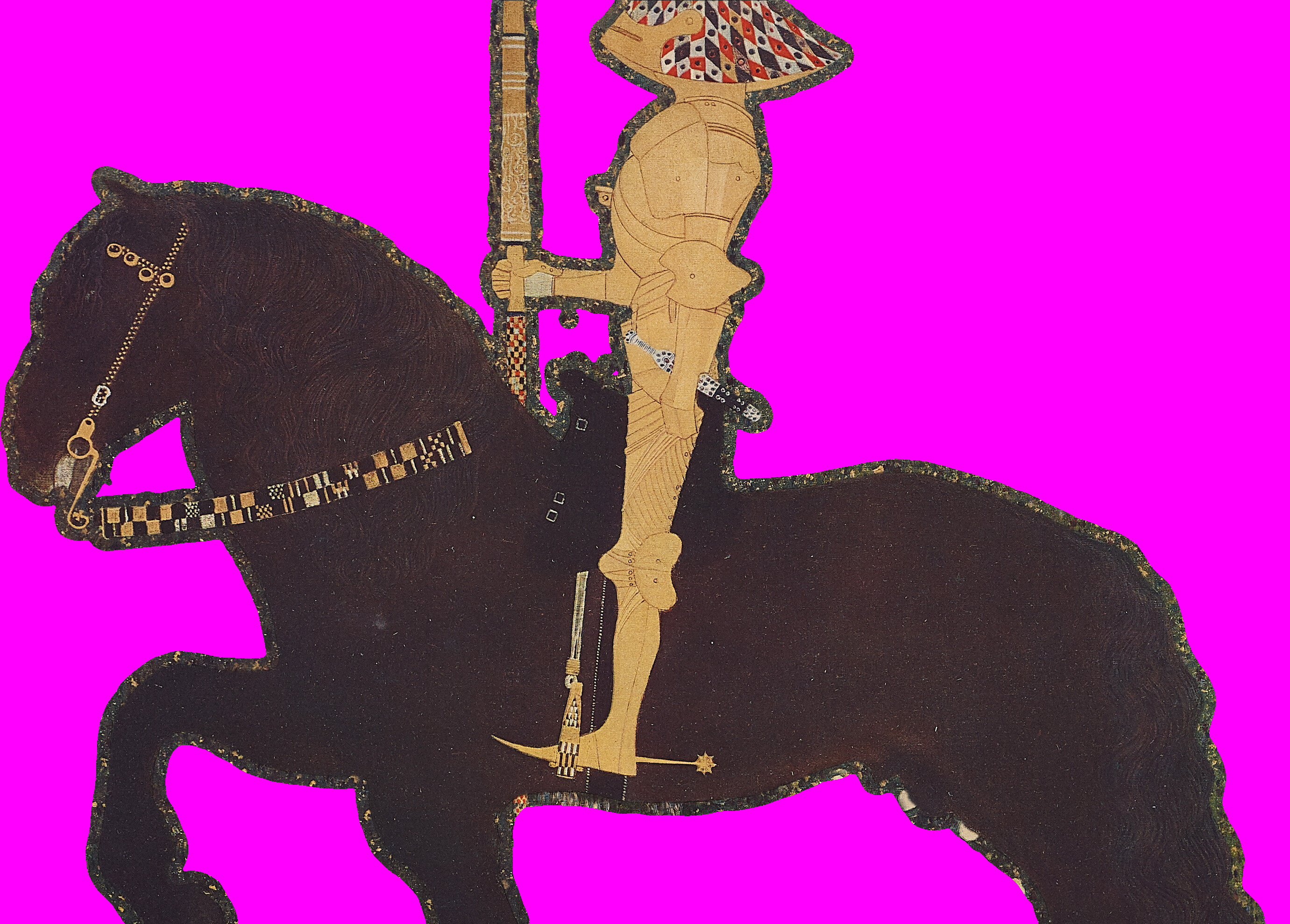

Gustav Klimt: The Golden Knight (Life a Battle), 1903, Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art

© Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art, Nagoya

The Golden Knight

The “Kollektiv-Ausstellung Gustav Klimt” [“Gustav Klimt Collective Exhibition”], which took place at the Secession from late 1903 to early 1904, presented another two new allegories by Klimt.

In contrast to the frequent depictions of women, men rarely appear as protagonists in Klimt’s oeuvre. In the painting Life Is a Battle, later referred to as The Golden Knight (1903, Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art, Nagoya), Klimt draws on the figure of the knight from The Beethoven Frieze (1901/02, Belvedere, Vienna), isolating it as a symbol of constant struggle. While the knight in the Beethoven Frieze fights as a “well-armed, strong man” against the monster Typhaeon and his horrible daughters in order to lead suffering humankind to music and happiness, the Golden Knight marches toward an uncertain future on the back of a giant black warhorse, past trees painted in the Pointillist style. The adder already hints at danger. Snakes play a major role in Klimt’s works from the Golden Period, appearing time and again in depictions such as Nuda Veritas (1899, Österreichisches Theatermuseum, Vienna) and shortly after 1900 in the Faculty Paintings of Medicine and Jurisprudence (1900–1907 and 1903–1907 resp., both destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945).

Could Gustav Klimt, who throughout his life saw himself as a lone fighter, sole breadwinner of his family and illegitimate children, and dissatisfied artist caught in a ceaseless struggle with his works, have created an allegorical parable in this painting? It would be quite obvious to see in the knight the constantly troubled painter, fighting against the empty canvas and, following the program of the Beethoven Frieze, leading suffering humankind to art and happiness. However, there is no (historical) proof of this theory.

That the painting meant a creative struggle for Klimt himself is evidenced by the fact that the artist could not finish it in time for the beginning of the exhibition in 1903. The Viennese public was forced to wait almost two weeks before the master won the battle and completed the work. The industrialist Karl Wittgenstein, a passionate Klimt collector, subsequently acquired the painting for his collection.

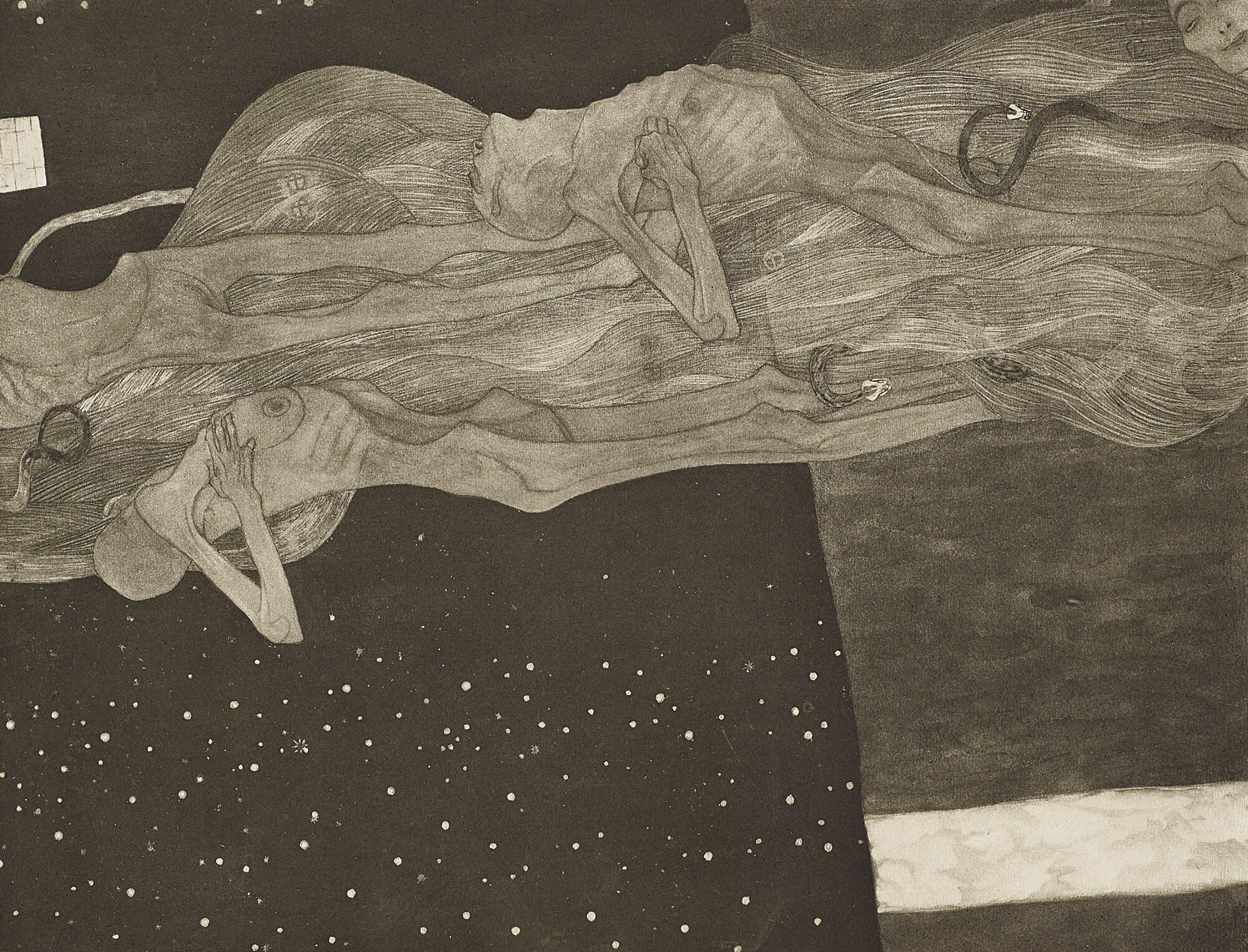

Gustav Klimt: From the Realm of Death (Stream of the Dead), 1903, Verbleib unbekannt

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

View into Villa Waerndorfer, 1903/04, MAK - Museum für angewandte Kunst, Archiv der Wiener Werkstätte

© MAK

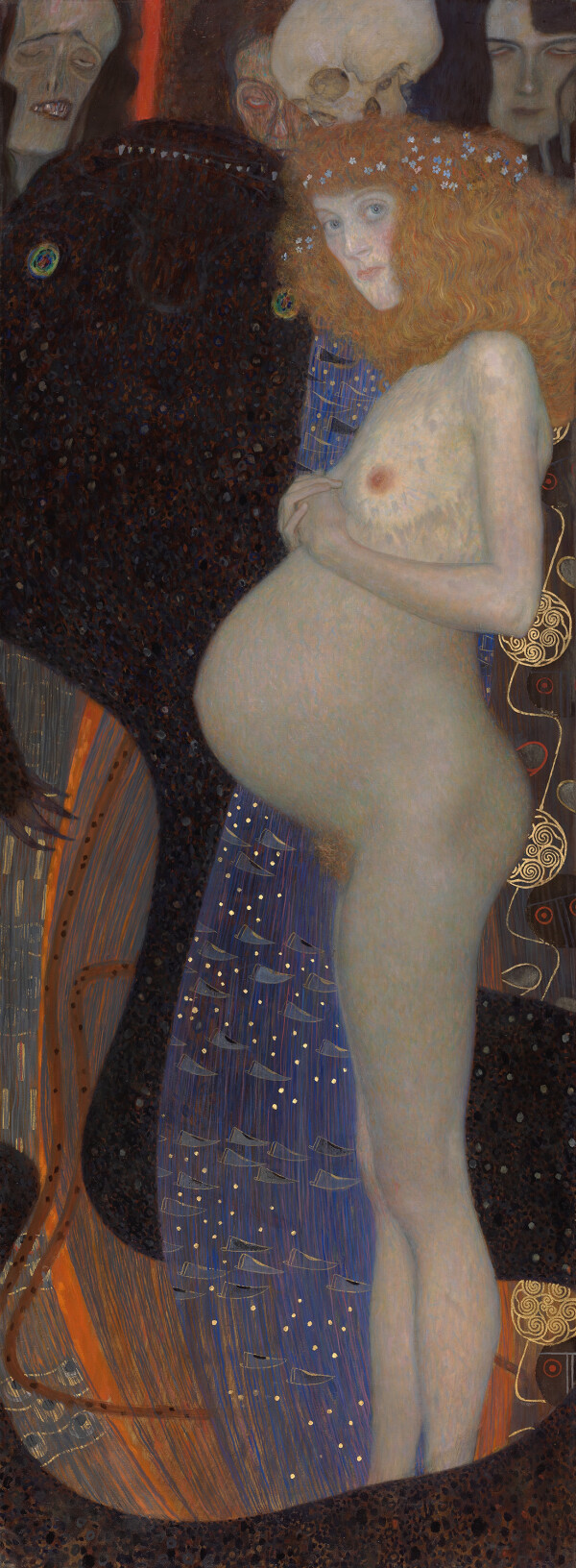

Gustav Klimt: Hope I, 1903/04, National Gallery of Canada

© NGC

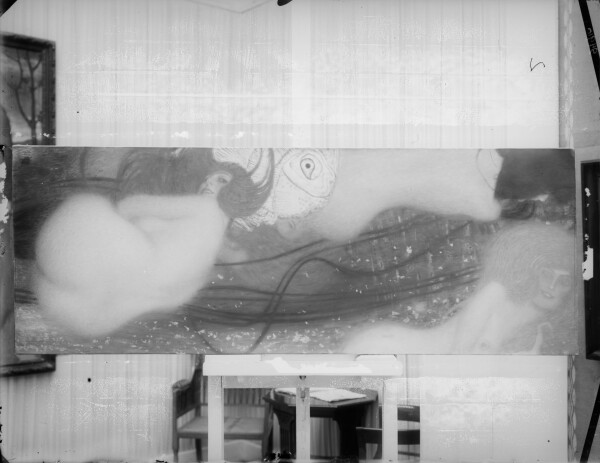

From the Realm of Death

The snakes mentioned above also play a role in Klimt’s first allegory dealing with the theme of death, From the Realm of Death (Stream of the Dead) (1903, whereabouts unknown, considered lost since the end of the war in 1945). The vision of the afterlife, in which emaciated human bodies seem to be floating weightlessly in the universe, has unfortunately only survived in the form of a black-and-white reproduction. However, the painting can be partially reconstructed in its color scheme thanks to a description by art critic Ludwig Hevesi. White scarfs featuring an irregular pattern of green double squares are said to have connected the dead, who are said to have spanned the surface of the picture like the “Milky Way across the night sky,” with dark blue vipers with golden heads meandering between them. Both the background and the frame may have suggested an infinite black void, now and then interspersed with colored stars. In terms of the structure of the painting, with its stream-like flow of arched bodies in the throng of an undulating, billowing ornamental band, Klimt formally harked back to Moving Water (1898, private collection) and Will-o’-the-Wisp (1903, private collection).

The first explorations of life and death had already taken place in the Faculty Painting of Medicine (1900–1907, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945). Klimt drew on anatomical sketches for the realistic depiction of the decomposed bodies. They were probably the same he had already used for said Faculty Painting. According to Hevesi, he had gained access to his lifeless models through his physician friend, Emil Zuckerkandl:

“How many hours he spent in Prof. Zuckerkandl’s dissecting room this summer, eagerly drawing in order to distill this pale, rigid play of colors and lines from all this death.”

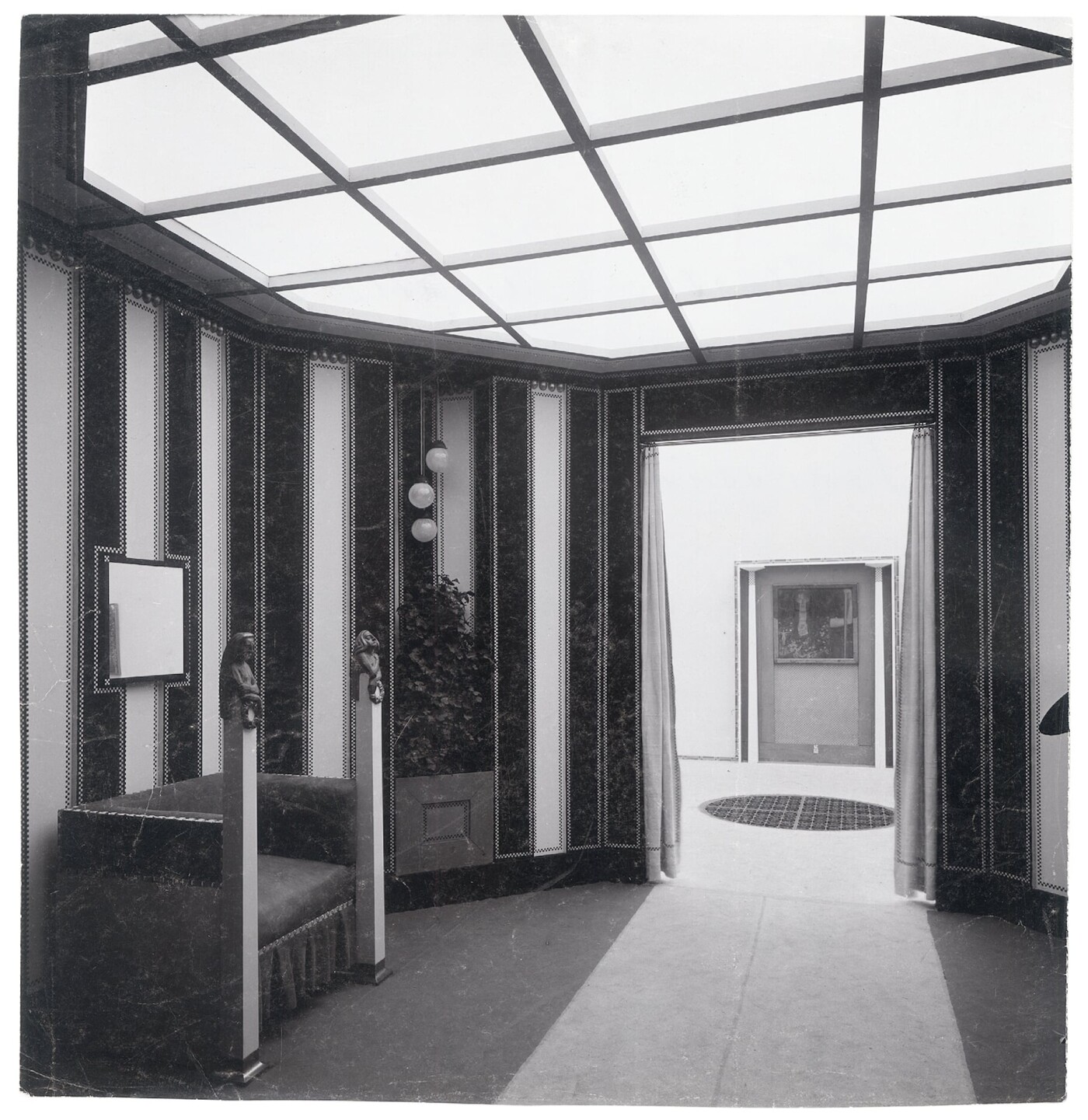

It was precisely this ruthlessly realistic depiction of death, entirely devoid of idealization or abstraction, that struck a chord with viewers and led to criticism and rejection. Fritz Waerndorfer eventually acquired the painting and kept it at his villa in Vienna’s Cottage Quarter.

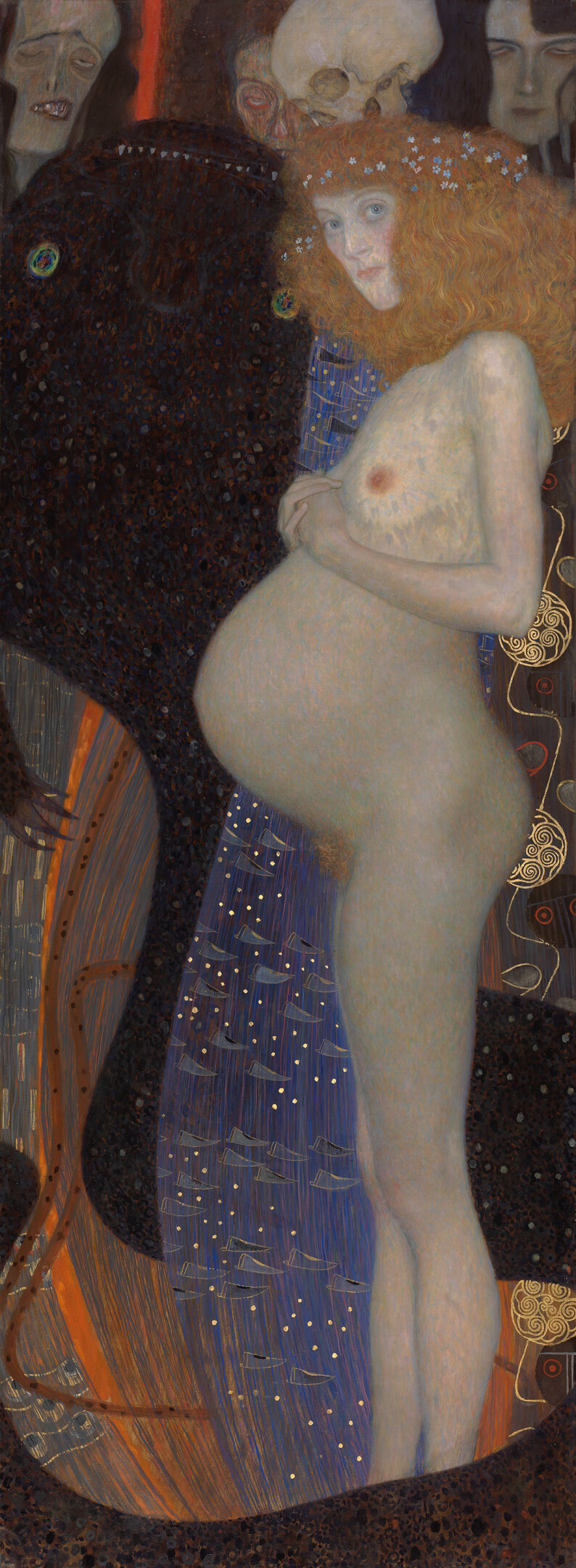

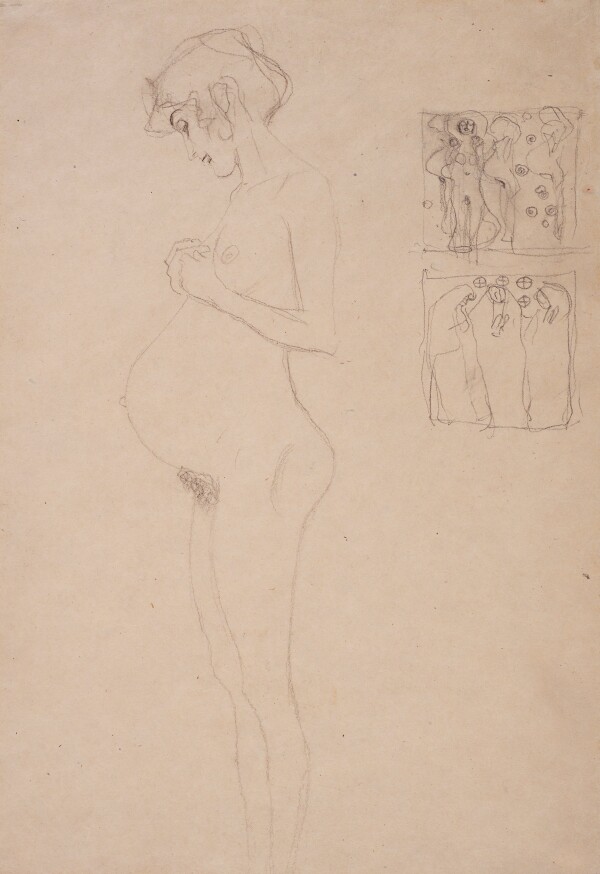

Hope I

In the painting Hope I (1903/04, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa) Klimt once again dealt with the theme of death. A naked pregnant woman – who is thus proverbially “expecting” – is shown standing in the foreground of the composition as a luminous figure. A personification of death in the form of a skeleton, emaciated faces, and a black shadowy figure loom menacingly in the background. The woman, however, who puts her hands protectively over her belly, looks at the viewer and is not aware of the imminent danger. Again, Klimt combines here a depiction of a woman with the element of threat. However, since Judith I, the connotations of the two terms have changed fundamentally. The woman has transformed from femme fatale to an almost sacred and innocent maternal figure. Her nakedness no longer radiates seduction but exhibits a childlike vulnerability. The symbols of danger are no longer meant as a warning directed at the viewer, but rather pose a threat to the protagonist. This change in Klimt’s image of women was probably due to the death of his son Otto Zimmermann in 1902, when he was not yet a year old.

Klimt actually wished to present Hope I in mid-November 1903 as part of the “Gustav Klimt Collective Exhibition.” However, Berta Zuckerkandl reported that Hartel, the Minister of Education, feared that the depiction of a naked pregnant woman might cause another scandal, as had happened with the Faculty Paintings earlier. It was at his request that Klimt withdrew the painting from the exhibition. When Hans Koppel saw the work in Klimt’s studio in November 1903, he referred to it as “Klimt’s most recent painting,” which would have been completed except for a few minor details. The painter still intended to change the background from landscape to patterned carpet and add “characteristic heads clarifying the thoughts behind the work.” In 1904, Gustav Klimt revised the composition and then sold the picture to Fritz Waerndorfer. The latter asked Koloman Moser to design a piece of furniture especially for the purpose of protecting the scandalous work from unwanted glances. On 25 November 1905, Ludwig Hevesi reported on the occasion of a visit to Villa Waerndorfer:

“That evening we were sitting together for a long time, looking at the gloomy works of art Herr Wärndorfer collects. Over a large picture, a double-wing door is hermetically closed to shield off any profane eye. This picture is Klimt’s famous or, rather, notorious ‘Hope’ – said young woman expecting in the most interesting ways, whom the artist dared to paint without clothes. One of his masterpieces. […] In the Klimt exhibition two years ago the picture could not be shown, as some superior authority prevented it. Now it has become a private matter at Waerndorfer’s house.”

Literature and sources

- Hans Koppel: Bei Gustav Klimt, in: Die Zeit, 15.11.1903, S. 4-5.

- Berta Zuckerkandl (Hg.): Zeitkunst. Wien 1901–1907, Vienna 1908.

- Franz Servaes: Klimt-Ausstellung (Sezession), in: Neue Freie Presse (Abendausgabe), 23.11.1903, S. 1-4.

- Ludwig Hevesi: Weiteres zur Klimt-Ausstellung. 21. November 1903, in: Acht Jahre Sezession (März 1897–Juni 1905). Kritik – Polemik – Chronik, Vienna 1906, S. 448–452.

- Joris-Karl Huysmans: Gegen den Strich, Bremen 1991.

- Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 16.02.1902, S. 12.

- Johannes Dobai: Gustav Klimt’s Hope I, in: National Gallery of Canada Bulletin, Nummer 71 (1971).

- Alice Strobl: Klimts Irrlichter. Phantombild eines verschollenen Gemäldes, in: Klimt-Studien. Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Galerie, Heft 66-67 (1978/79), S. 119–145.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt 150 Jahre, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 13.07.2012–27.01.2013, Vienna 2012.

- Alfred Weidinger: Les Belles Dames. Gedanken zum Frauenbildnis bei den Präraffaeliten und Gustav Klimt, in: Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Schlafende Schönheit. Meisterwerke viktorianischer Malerei aus dem Museo de Arte de Ponce, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna), 14.06.2010–03.10.2010, Vienna 2010, S. 103-110.

- N. N.: Theater- und Kunstnachrichten, in: Neue Freie Presse (Morgenausgabe), 04.04.1901, S. 7.

- N. N.: X. Ausstellung der Vereinigung vom 15. März bis 12. Mai 1901. Liste der verkauften Werke, in: Vereinigung bildender KünstlerInnen Wiener Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Mitteilungen der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 4. Jg., Heft 12 (1901), S. 209.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2017.

- Fritz von Ostini: Die VIII. Internationale Kunstausstellung im kgl. Glaspalast zu München, in: Die Kunst. Monatshefte für freie und angewandte Kunst, 16. Jg., Band 3 (1901).

- Ludwig Hevesi: Haus Wärndorfer, in: Altkunst – Neukunst, Vienna 1909, S. 221–227.

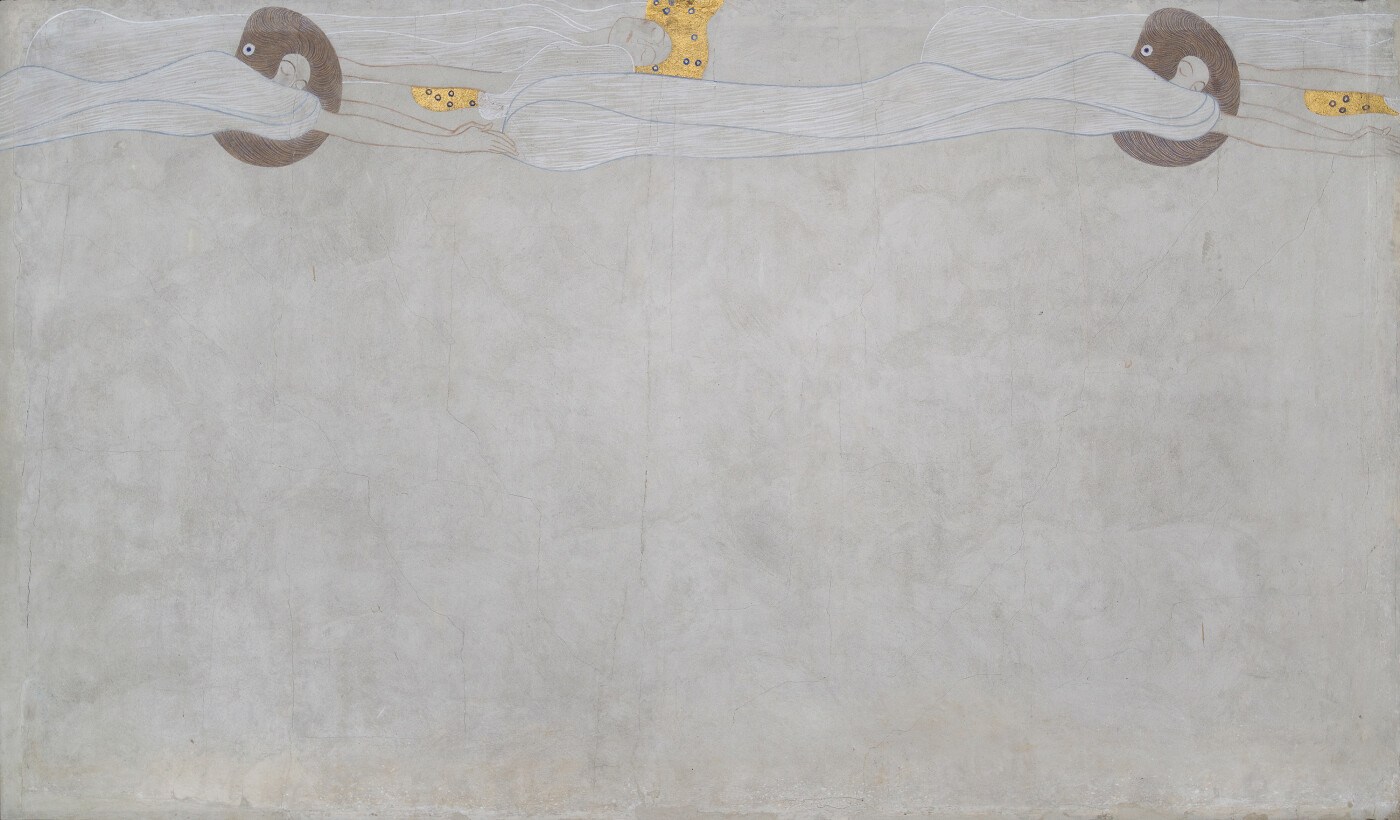

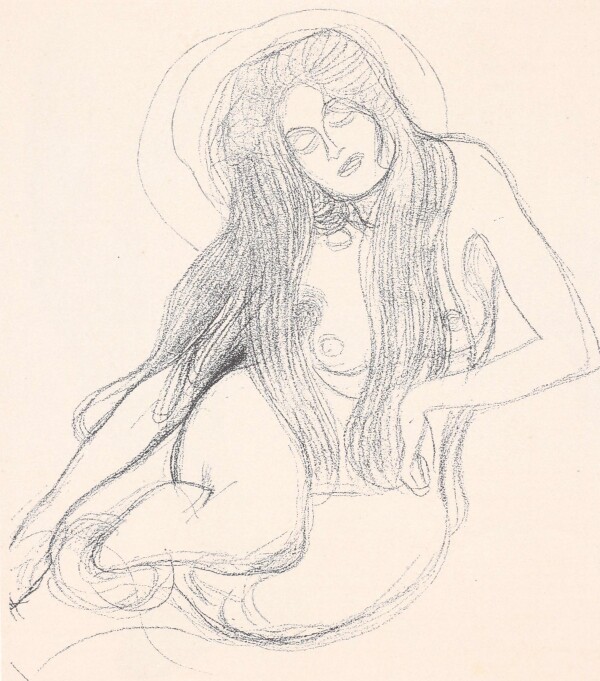

Mystic Underwater Worlds

Water Nymphs (Silverfish), 1902/03, The Albertina Museum

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

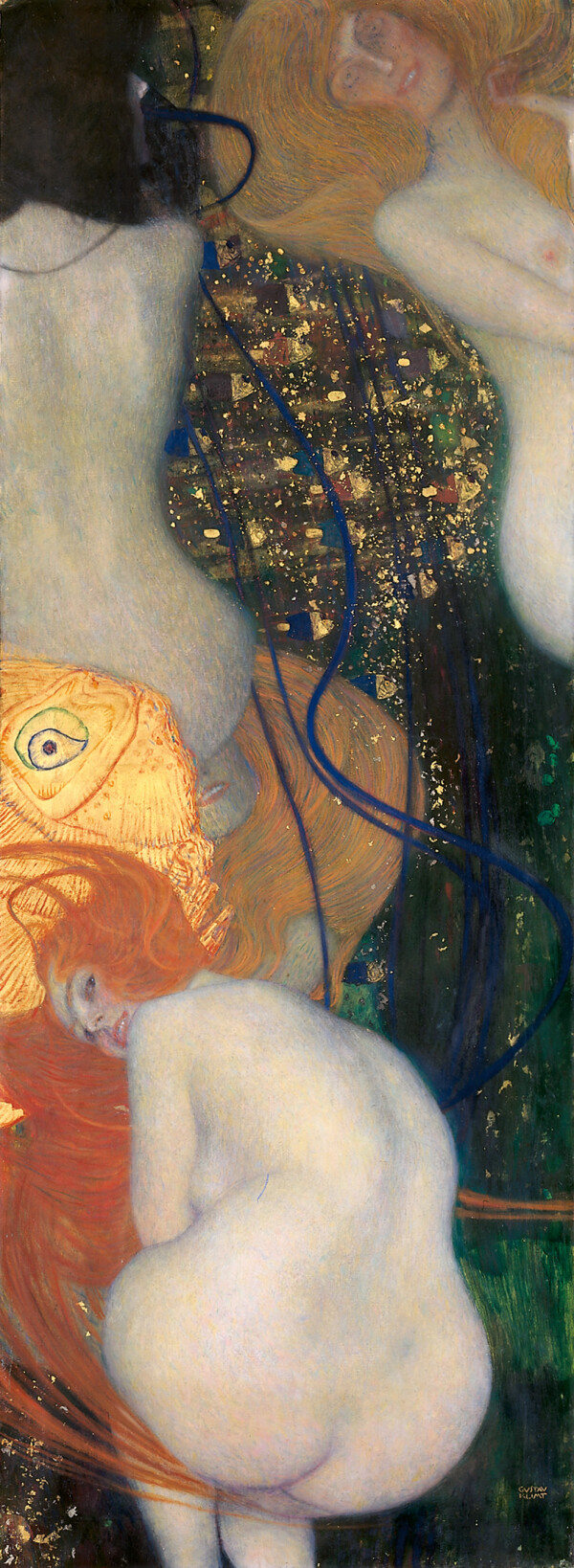

Gustav Klimt: Goldfish, 1901/02, Kunstmuseum Solothurn, Dübi-Müller-Stiftung

© Kunstmuseum Solothurn

Gustav Klimt: Water Snakes II, 1904, private collection

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Klimt’s output between 1901 and 1903 is characterized by such fantastic and mystical figures as mermaids, will-o’-the-wisps, and whimsical aquatic creatures.

“He populates the mysterious depths of water with the most terrific, most seductive mermaid magic. Goldfish, the Wave, and now, as the latest caprice, the chromatically delightful little picture of the ‘Water Nymphs’ are full of dewily sparkling poetry. A ‘Daphne’ and the ‘Will-o’-the-Wisps’ are also among these absolutely fantastic creations.”

In 1903/04, a contributor to Die Kunst für Alle found these words to describe said group of Klimt’s paintings, which deals primarily with fantastic beings from the aquatic realm. Klimt’s images of erotically charged female aquatic creatures and light phenomena rank among his most mysterious paintings. In four works – Water Nymphs (Silverfish) (1902/03, Albertina, Vienna), Goldfish (1901/02, Kunstmuseum Solothurn, Dübi-Müller-Stiftung), Will-o’-the-Wisp (1903, private collection), and Daphne (1902/03, private collection) – he revisited the theme of floating, mystical underwater beings he had first explored in Moving Water (1898, private collection).

Scholars consider all of these images as evidence of woman’s misogynistic image prevalent at the turn of the century. Many thought that, women, being creatures of nature, developed an erotic attraction that could be dangerous for men. Gustav Klimt translated this idea into images of teasing, mostly naked women with long hair floating in the water. Swimming with goldfish or silverfish, they drift in dark green waters, existing far removed from all cultural norm.

While Klimt mostly developed his compositions from a multitude of motion studies of anonymous models, individual women from reputable bourgeois backgrounds also made their way into these dubious and somber compositions. Thus, upon closer inspection of Water Nymphs, one can recognize in the face of one of the two black, tadpole-like creatures the features of Rose von Rosthorn-Friedmann, whose society portrait Klimt had completed in 1900/01. The art critic Ludwig Hevesi had already noticed their resemblance:

“But I would rather call them tadpoles, all dotted with matte-colored trout spots, and charming, quiet, lurking mermaid faces. One is truly related to one of his best female portraits. How the painter understood to insert these faces in such a self-understood fashion is quite a piece of natural humor.”

Whether the elegant lady knew about her role as a model, or whether Klimt decided to use the sketches for her portrait without her consent can unfortunately not be verified.

It was above all the painting Goldfish, compositionally reminiscent of the human tower in the Faculty Painting of Philosophy (1900–1907, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945) that caused quite a stir. Much more than a mere display of unbridled femininity, Klimt here deliberately directed a provocative message at the critics of his Faculty Paintings, aptly summarized by Ludwig Abels as follows:

“[...] and in a jaunty, brilliantly painted fantasy called ‘Goldfish,’ he ostentatiously turned his back on any influence through public opinion.”

An exception among Klimt’s paintings from the realm of mythology and aquatic life is Daphne. Conceived more as a lady’s portrait than as a crowded and dynamic scene, the painting only very subtly reveals the protagonist’s identity. While the meadow landscape represents Daphne’s flight ashore from Apollo, implied here only by the title, since there is no trace of the god, the cloth fluttering behind her, with its blue color and wavy pattern, resembles almost a river meandering away from the landscape. Here we also find the clue to the identity of the red-haired female figure as a water nymph. The dreamily closed eyes and the slightly parted lips of her face, placed directly in front of the blue expanse, almost seem to betray Daphne’s longing for the water, where she would once again be able to drift carelessly and playfully with the undulating figures in Will-o'-the-Wisp and Moving Water. In the following years, Klimt would continue to develop the theme of the underwater world with such paintings as Water Snakes I (Parchment) (1904, reworked before 1907, Belvedere, Vienna) and Water Snakes II (1904, reworked before 1908, private collection), using materials and techniques from the decorative arts.

Literature and sources

- Alfred Weidinger: Les Belles Dames. Gedanken zum Frauenbildnis bei den Präraffaeliten und Gustav Klimt, in: Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Schlafende Schönheit. Meisterwerke viktorianischer Malerei aus dem Museo de Arte de Ponce, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna), 14.06.2010–03.10.2010, Vienna 2010, S. 103-110.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt 150 Jahre, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 13.07.2012–27.01.2013, Vienna 2012.

- Dr. Ludwig Abels: Ein Wiener Kunst-Jahr, in: Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, Band 10 (1902), S. 463-474, S. 464.

- Die Kunst für Alle. Malerei, Plastik, Graphik, Architektur, 19. Jg. (1903/04), S. 163.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2017.

- Ludwig Hevesi: Weiteres zur Klimt-Ausstellung. 21. November 1903, in: Acht Jahre Sezession (März 1897–Juni 1905). Kritik – Polemik – Chronik, Vienna 1906, S. 448–452.

- Alice Strobl: Klimts Irrlichter. Phantombild eines verschollenen Gemäldes, in: Klimt-Studien. Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Galerie, Heft 66-67 (1978/79), S. 119–145.

The Beethoven Frieze

Alfred Roller: Poster of the XIV Secession Exhibition (Klinger-Beethoven), 1902, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg (MK&G)

© Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg

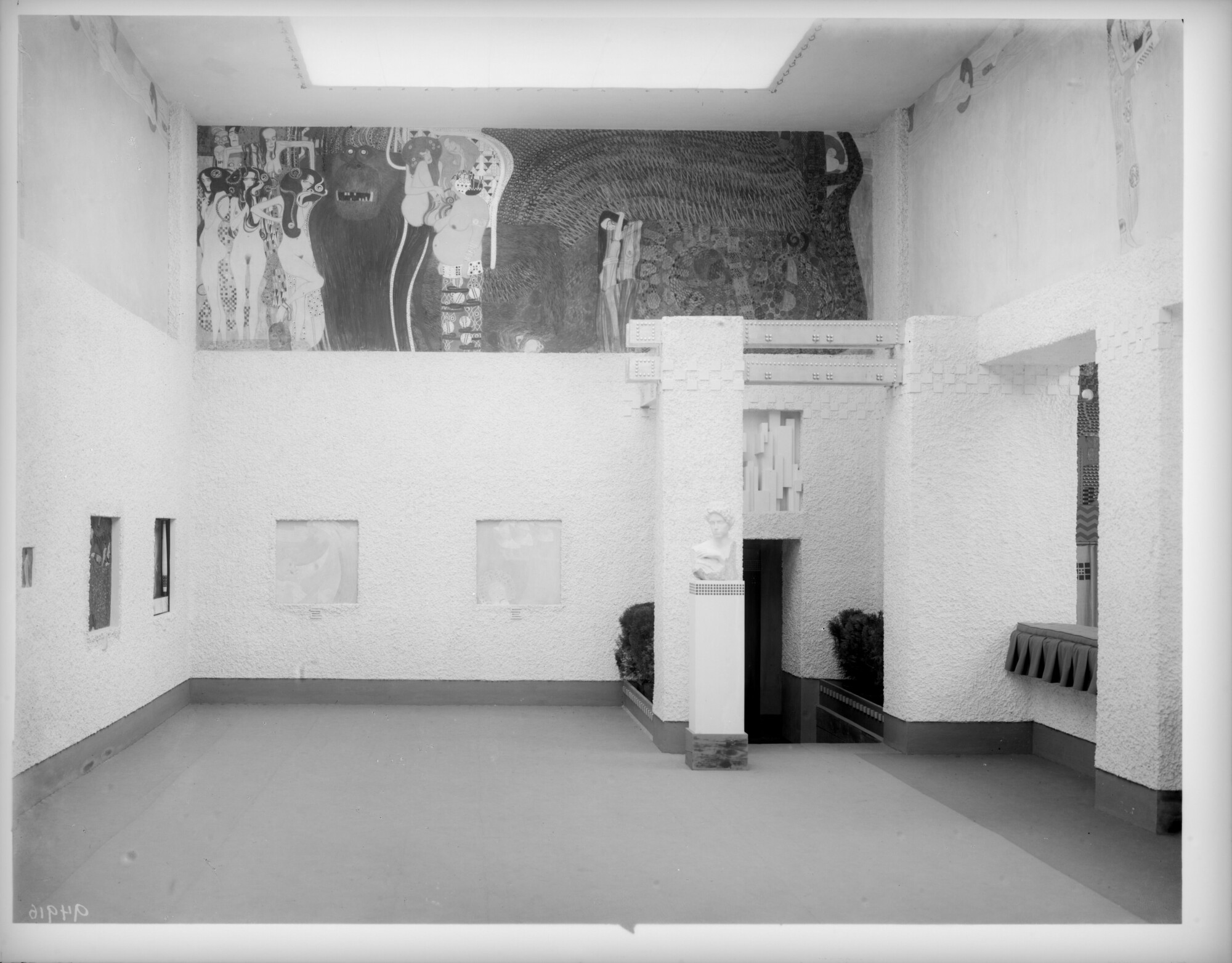

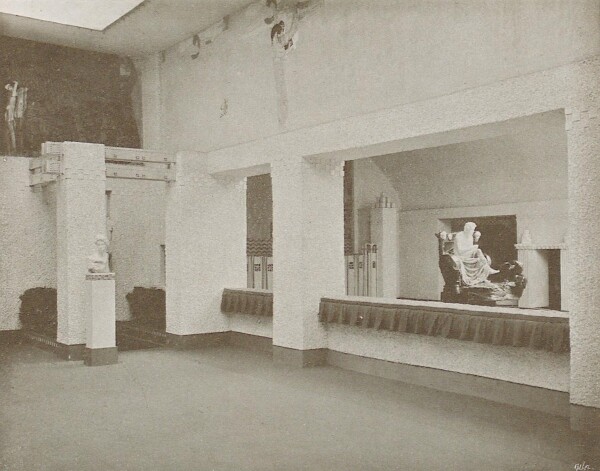

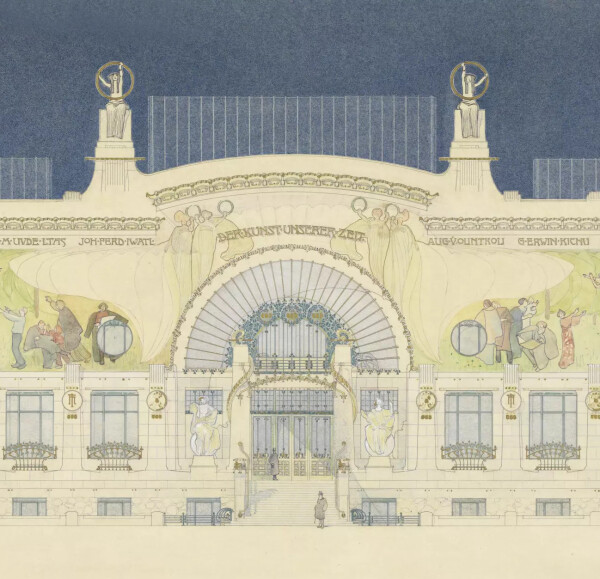

On the occasion of the presentation of Max Klinger’s monumental Beethoven statue at the Vienna Secession in 1902, Gustav Klimt conceived the so-called Beethoven Frieze. Painting directly onto three exhibition walls using casein paints, the artist intended his work to lead up to the central sculpture thematically, thus contributing with the frieze to what was to become a Gesamtkunstwerk or universal work of art. Although Ludwig van Beethoven is mentioned in the title, the composer is not depicted.

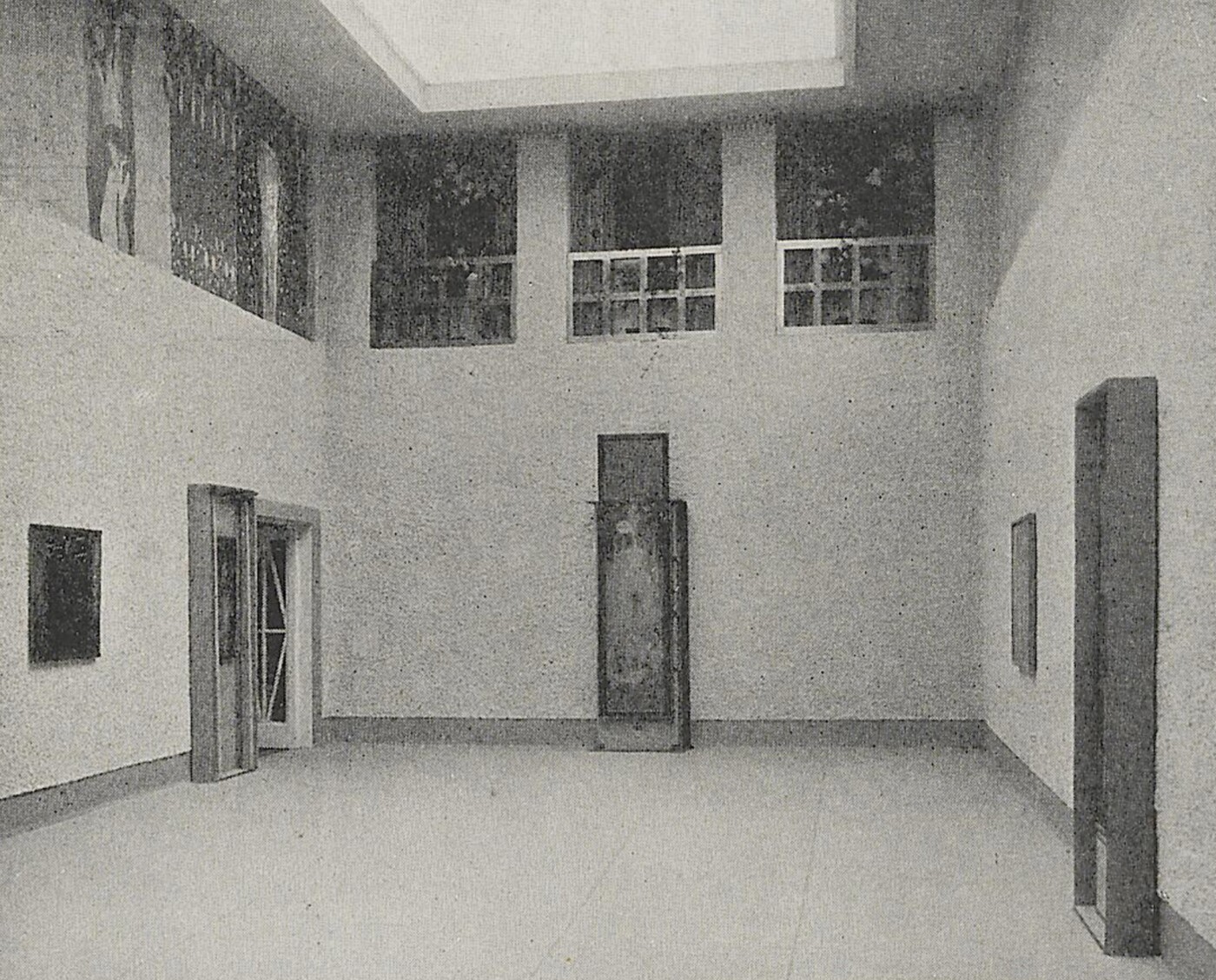

From 15 April to 27 June 1902, 21 male artists and one female artist presented a universal work of art around Max Klinger’s huge sculpture of the composer Ludwig van Beethoven. As Gustav Klimt’s monumental contribution to the “XIV. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession Wien” [“14th Exhibition of the Association of Austria Artists Vienna Secession”], also referred to as “Beethoven Exhibition,” the Beethoven Frieze (1901/02, Belvedere, Vienna, on permanent loan to the Vienna Secession) extends over a length of 34.14 meters and a height of 2.15 meters.

Beethoven, having died in Vienna in 1827, had risen to the status of unattainable genius in the perception of Klimt’s contemporaries. Max Klinger, a sculptor from Leipzig, sought to do justice to this perception when he painstakingly created a statue of the revered composer over a period of 20 years. The statue of Beethoven was finally completed in the spring of 1902, and the Secessionists successfully negotiated that the first presentation of the work should take place at their venue in Vienna.

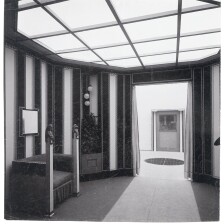

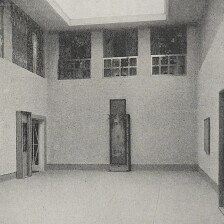

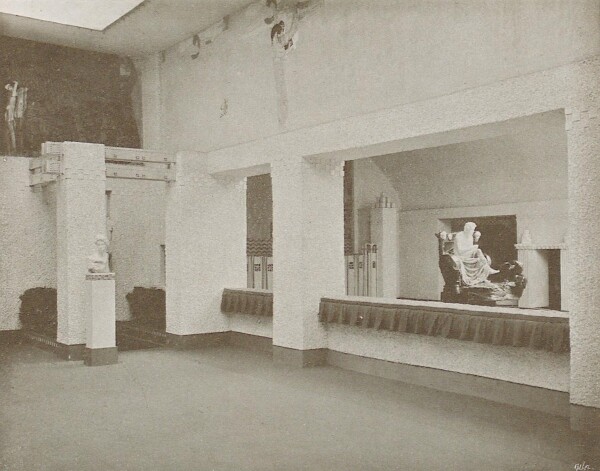

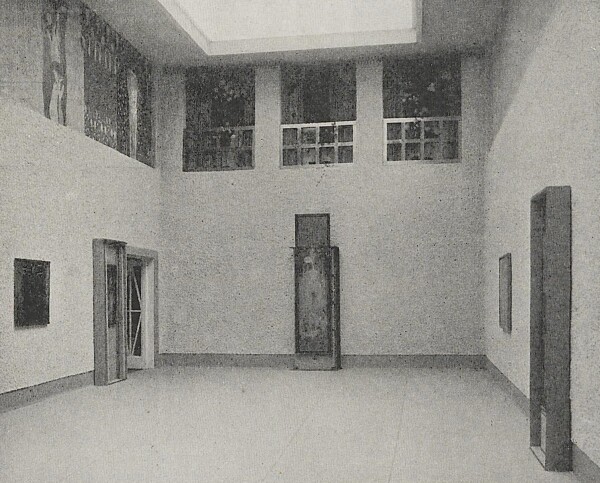

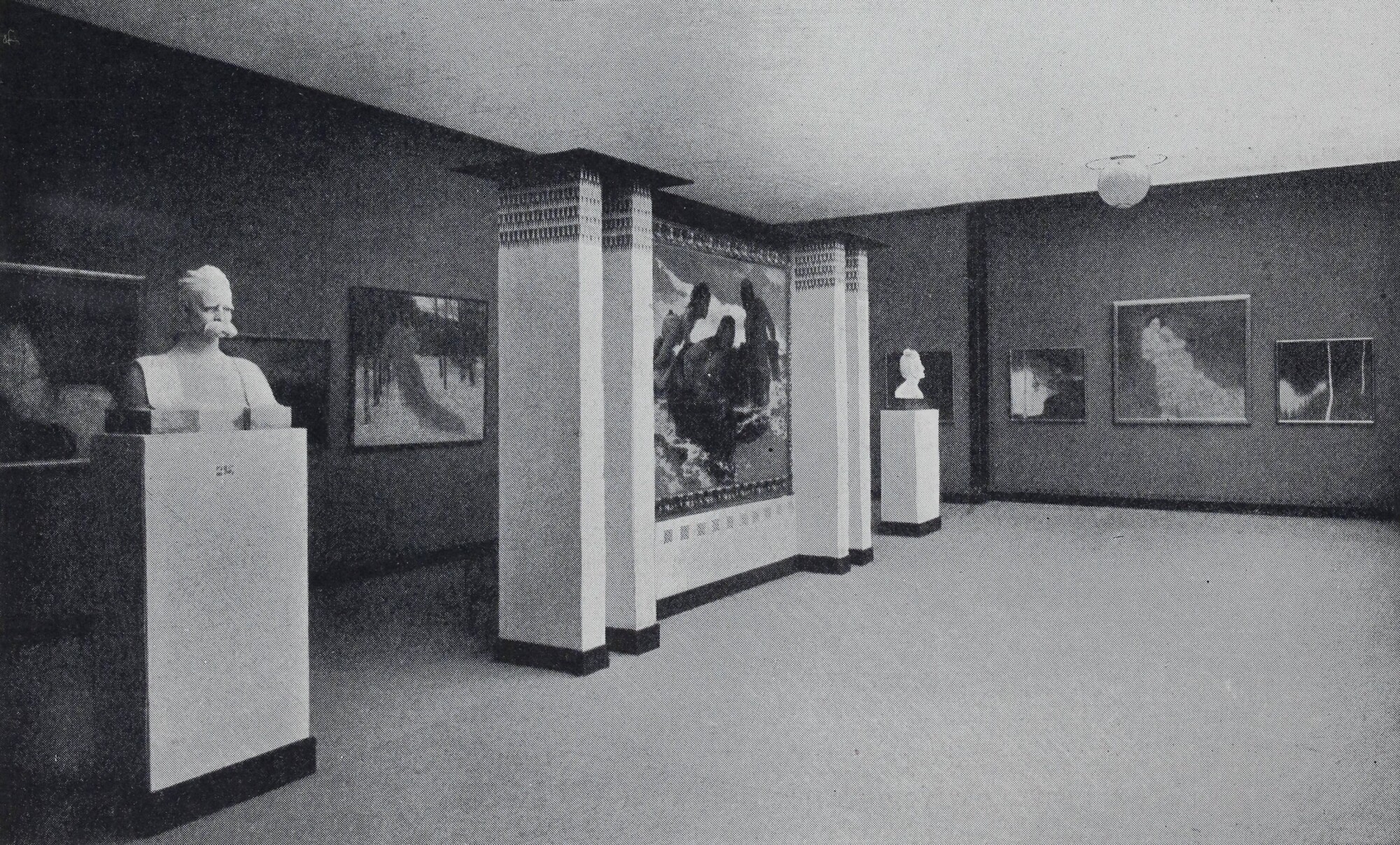

Exhibition Architecture – A Worthy Framework for Beethoven

To mark the 75th anniversary of Beethoven’s death on 26 March 1902, the Vienna Secession decided to dedicate a theme exhibition to the composer. Gathering around Josef Hoffmann, who was responsible for the exhibition architecture, the participants conceived a worthy presentation, with Klinger’s monument at the center. By exploring the possibilities of wall-mounted solutions and arranging their works around the composer’s statue, the artists jointly created an almost sacred art space, a site for holy “temple art.”

The preparatory works began in the summer of 1901. The participating artists included, among others, Alfred Roller, Josef Maria Auchentaller, Ferdinand Andri, Emil Orlik, and Gustav Klimt. Josef Hoffmann divided the Vienna Secession’s exhibition hall into three rooms, separating the left aisle through a windowed wall. This enabled Gustav Klimt to design a tripartite composition comprising two long side walls (13.92 m each) and a shorter rear wall (6.3 m) at the center.

Moriz Nähr: Gustav Klimt with the artists participating in the 14th Exhibition of the Secession, April 1902, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

At the Secession’s Beethoven exhibition, the painter Klimt showed that he could also create groundbreaking works of art outside his familiar medium. Since the summer of 1901 he had been working on a piece that would fuse painting, sculpture, and arts and crafts to create a monumental overall composition. While he initially prepared the composition through studies, correspondence proves that Klimt spent more time at the Secession in the late summer and fall of 1901 in order to transfer his work directly to the wall on site. Thus he wrote to Maria Zimmermann toward early October:

“I am not working at the Secession building as such yet – today, around noon, I hope to finally make it there – to begin with the actual work on the wall [...]”

By 12 November 1901 he had completed the work:

“My last day of work is tomorrow in the morning – I am glad [...]. If you need money earlier, send me a pneumatic letter card to the Secession -”

A Multimedia Work of Art

The accompanying text in the 1902 exhibition catalog briefly mentions the materials used by Gustav Klimt: “Casein paints, applied stucco, gilding,” is what it says. However, a large-scale restoration campaign in the 1980s managed to identify many more materials.

Klimt first drew the figures in graphite onto the dry plaster ground and then executed the colored areas using water-soluble casein paint. Moreover, he applied cut opalescent glass cabochons, cut and metal-mounted transparent colored glass, mirror fragments, mother-of-pearl buttons, and hollow brass rings. Thanks to the casein paint, which is matt after it has dried, the artist could intensify the glow of gold and silver. Klimt achieved the flatness of the gilded areas with the aid of oil gilding. It is interesting that Klimt used aluminum foil for the knight’s sword. This produced a silver tone without running the risk of oxidation. In a final step, the artist used a pencil to draw over the gilding, or he glazed gilded areas in colors. What is remarkable about the formal solution of the Beethoven Frieze is that there are many areas of “blank” wall shining through, while the narrative is heavily rhythmized.

Moriz Nähr: Insight into the XIV Secession Exhibition, April 1902 - June 1902, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

This Kiss to the Whole World

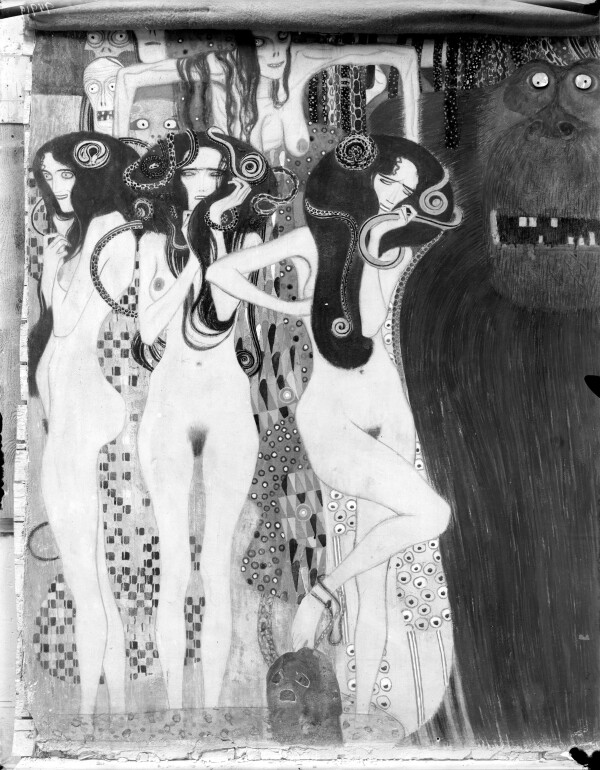

A glance into the exhibition catalog also provides information about the figures conceived by Klimt, whose symbolic content would be difficult to decipher without the contribution of an author whose name remains unknown. Thus, the flying or floating genii in long white robes represent the “Yearning for Happiness.” This “Train of Yearning” connects three quarters of the composition. On the left wall, the Knight in Golden Armor stands out, who is supposed to represent “Armored Strength.” From his head spring Ambition and Compassion as female personifications. Ambition holds a laurel wreath in her hands, while Compassion is depicted folding her hands. A poor family is shown kneeling behind the knight. Pleading for help, it stands for “Weak Mankind,” as is pointed out in the catalog. After this introduction, the “Hostile Forces” follow on the narrow wall, with the monster Typhoeus, half gorilla, half octopus, at center, carrying two human skulls in his paw.

Around the Typhoeus, Klimt has grouped the three Gorgons on the left, with “Sickness, Death, and Madness” above them and “Lust, Lechery, and Intemperance” to the monster’s right. The seated woman embracing herself represents “Gnawing Grief.” In the upper right corner, “Yearning for Happiness” reappears and leads up to “Poetry,” which Klimt has depicted in the form of a woman with a kithara.

-

Gustav Klimt: The Beethoven Frieze (The Longing for Happiness), 1901/02, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: The Beethoven Frieze (The Longing for Happiness), 1901/02, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: The Beethoven Frieze (The Longing for Happiness), 1901/02, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: The Beethoven Frieze (The Longing for Happiness), 1901/02, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: The Beethoven Frieze (The Suffering of Weak Mankind, The Well-Armed Strongman), 1901/02, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: The Beethoven Frieze (The Suffering of Weak Mankind, The Well-Armed Strongman), 1901/02, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: The Beethoven Frieze (The Longing for Happiness), 1901/02, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: The Beethoven Frieze (The Longing for Happiness), 1901/02, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: The Beethoven Frieze (The Longing for Happiness is Satisfied by Poetry), 1901/02, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: The Beethoven Frieze (The Longing for Happiness is Satisfied by Poetry), 1901/02, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: The Beethoven Frieze (The Arts, Paradise Choir and Embrace), 1901/02, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: The Beethoven Frieze (The Arts, Paradise Choir and Embrace), 1901/02, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: The Beethoven Frieze (The Hostile Forces), 1901/02, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: The Beethoven Frieze (The Hostile Forces), 1901/02, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: The Beethoven Frieze (The Hostile Forces), 1901/02, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

Gustav Klimt: The Beethoven Frieze (The Hostile Forces), 1901/02, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

Moriz Nähr (?): Insight into the XIV Secession Exhibition, April 1902 - June 1902

© Heidelberg University Library

Hoffmann and Klimt had envisaged that the audience would then be able to see the statue of Beethoven through the opening, connecting up to antique Poetry. The phrase “The arts lead the way for us into an ideal realm” is represented through rising personifications in the nude of the various genres of art.

The end of the frieze is made up of a “Choir from Paradise” on a flowering meadow, surrounding a couple embracing each other, complete with rose bush and entitled “This Kiss to the Whole World.” The famous line from Schiller’s Ode to Joy (1786) was set to music by Beethoven in his Symphony No. 9 (1822–1824), and it leads up to Max Klinger’s statue of Beethoven. On the one hand, the interpretation of the Beethoven Frieze is based on the traditional symbolism of the figures and, on the other hand, on Richard Wagner’s reading of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9, which he had put in writing. Perhaps Gustav Mahler, who conducted a wind ensemble of the Vienna Symphony Orchestra at the opening, conveyed knowledge of this interpretation to Gustav Klimt and the Secessionists. According to Wagner’s reading, the four movements of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 represent mankind’s struggle for happiness against overwhelming threats, which finds expression in the final chorus and Friedrich Schiller’s Ode to Joy. Since Gustav Klimt dealt intensively with this theme in the years between 1900 and 1907 – above all in the context of his work on the Faculty Paintings – the Beethoven Frieze may be counted among the important works from both the Golden Period and Klimt’s maturity.

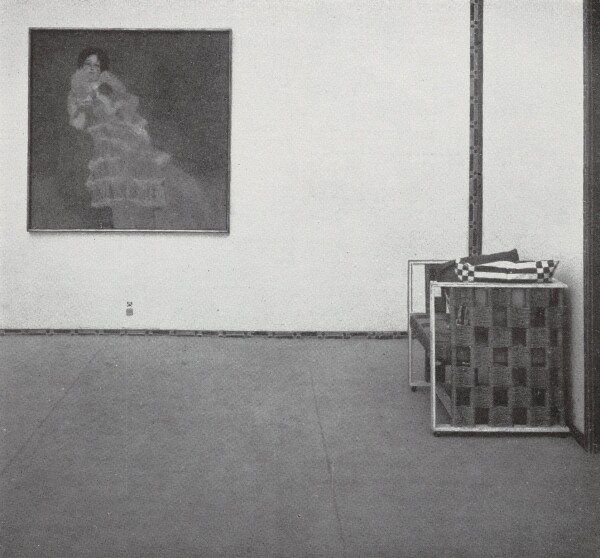

Insight into the XVIII Secession Exhibition, November 1903 - January 1904

© Heidelberg University Library

Moriz Nähr: The Beethoven Frieze (The Hostile Forces), presumably 1903, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Elfriede Mejchar: The Beethoven frieze, early 1960s - mid-1970s, Federal Monuments Authority Austrian

© BDA, Vienna - Federal Monuments Office

Saved from Destruction and Sale

Gustav Klimt executed the Beethoven Frieze in casein paints on the already dry exhibition wall. Klimt had obviously planned the frieze as an ephemeral work of art that would be demolished after the exhibition had closed.

However, according to an article in the Illustriertes Wiener Extrablatt, the Viennese public had expressed its interest to start collecting signatures to rescue the work from destruction. Both Klinger’s statue and Klimt’s frieze were to be purchased by the City of Vienna and placed in a specially built temple. Although this plan was never realized, it shows the great interest Viennese society had in the two works. Hevesi also expressed his support for the preservation of the Beethoven Frieze:

“In the left aisle, Gustav Klimt has created a delightful frieze painting, so full of his bold, self-important personality that one must resist the temptation to call this painting his masterpiece. If it really is to serve only the temporary Beethoven purpose like all the rest of the exhibition and then be destroyed, Austrian art will suffer a severe loss.”

In the end, the prominent art collector Carl Reininghaus acquired the frieze for the legendary sum of 40,000 crowns (about 281,400 euros). The panels were to be removed from the walls in a laborious process. Klimt himself assured to repair the resulting damage free of charge.

However, the frieze remained in place for the show referred to as “Klimt-Kollektive” [“Gustav Klimt Collective Exhibition”] in 1903. After the end of the exhibition, it was sawn out of the wall and divided into seven panels. Since the building planned by Reininghaus to house the frieze was never realized, the work was stored in various depots for years. In 1915, Reininghaus sold the important work to the Klimt collectors August and Serena Lederer through the agency of Egon Schiele. The couple was expropriated after Austria’s “Anschluss” to the German Reich, and the frieze was transferred to the Institute for the Preservation of Monuments. After World War II, the Beethoven Frieze was returned to its heir, Erich Lederer, in 1950; however, he was not allowed to take the listed work abroad and in return would have had to donate works of art to Viennese museums. After many years of tough negotiations, Erich Lederer sold the Beethoven Frieze to the Republic of Austria in 1972. The precarious state of preservation necessitated a ten-year restoration process. In 1985, the Beethoven Frieze was presented to the public for the first time as part of the exhibition “Traum und Wirklichkeit” [“Dream and Reality”] at the Vienna Künstlerhaus. Afterwards, the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere (now Belvedere, Vienna) as the owner of the work decided to have the Beethoven Frieze installed in the basement of the Vienna Secession, where it can still be seen today.

Literature and sources

- Sophie Lillie: Feindliche Gewalten: Das Ringen um Gustav Klimts Beethovenfries, Vienna 2017.

- Stephan Koja (Hg.): Gustav Klimt: Der Beethoven-Fries und die Kontroverse um die Freiheit der Kunst, Munich 2006.

- Margarethe Szeless: Der Beethovenfries – Provenienz- und Ausstellungsgeschichte, in: Susanne Koppensteiner (Hg.): Gustav Klimt- Beethovenfries, Vienna 2002, S. 19-48.

- Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): XIV. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession. Klinger Beethoven, Ausst.-Kat., Secession (Vienna), 15.04.1902–15.06.1902, Vienna 1902.

- Alfred Weidinger: 100 Jahre Palais Stoclet. Neues zur Baugeschichte und künstlerischen Ausstattung, in: Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt – Josef Hoffmann. Pioniere der Moderne, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna) - Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 25.10.2011–04.03.2012, Munich 2011, S. 202-251.

- Peter Vergo: Gustav Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze, in: The Burlington Magazine, 115. Jg., Heft 839 (1973), S. 108-113.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt – Josef Hoffmann. Pioniere der Moderne, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna) - Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 25.10.2011–04.03.2012, Munich 2011.

- Anette Vogel (Hg.): Gustav Klimt Beethovenfries. Zeichnungen, Ausst.-Kat., Balingen Town Hall (Balingen), 10.07.2010–26.09.2010, Munich 2010.

- Charles Holme (Hg.): The Art-Revival in Austria. The Studio. Special Summer Number, London - Paris - New York 1906.

- Rohrpost-Kartenbrief von Gustav Klimt in Wien an Maria Zimmermann in Wien (12.11.1901). S63/27.

- Brief von Gustav Klimt am Attersee an Maria Zimmermann in Villach (vermutlich Anfang September 1901). S63/24.

- Brief von Gustav Klimt an Maria Zimmermann (Ende September 1901 - Anfang Oktober 1901). S63/23.

- Brief von Gustav Klimt am Attersee an Maria Zimmermann (August 1901). S63/20.

- Brief von Gustav Klimt am Attersee an Maria Zimmermann (August 1901). S63/19.

- Revers von Gustav Klimt in Wien, mitunterschrieben von Carl Moll und Hugo Haberfeld (16.12.1907). H.I.N. 15.9214, .

- Brief von Erich Lederer in Györ an Egon Schiele (04.10.1915). S263.

- Brief mit Kuvert von Gustav Klimt in Wien an Maria Zimmermann in Villach (17.10.1902). S63/28.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007.

- Alexandra Matzner, Gustav Klimts Gold für das Paradies Vergoldungstechnik im Beethovenfries, Wien 2015. artinwords.de/klimt-gold-im-beethovenfries/ (12/20/2019).

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Die Galerie Miethke. Eine Kunsthandlung im Zentrum der Moderne, Ausst.-Kat., Jewish Museum Vienna (Vienna), 19.11.2003–08.02.2004, Vienna 2003.

- Ivo Hammer: 110 Jahre Beethovenfries von Gustav Klimt. Zu Maltechnik, Restaurierung und Präsentation, in: Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt – Josef Hoffmann. Pioniere der Moderne, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna) - Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 25.10.2011–04.03.2012, Munich 2011, S. 140-149.

- Manfred Koller: Zur Technik und Erhaltung des Beethoven-Frieses, in: Stephan Koja (Hg.): Gustav Klimt: Der Beethoven-Fries und die Kontroverse um die Freiheit der Kunst, Munich 2006, S. 155-165.

- Manfred Koller: Klimts Beethovenfries. Zur Technologie und Erhaltung, in: Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Galerie, 22/23. Jg., Nummer 66/67 (1978/79), S. 215-240.

- Marian Bisanz-Prakken: Der Beethovenfries von Gustav Klimt in der XIV. Ausstellung der Wiener Secession (1902), in: Robert Waissenberger (Hg.): Traum und Wirklichkeit. Wien 1870–1930, Ausst.-Kat., Museums of the City of Vienna (Vienna), 28.03.1985–06.10.1985, Vienna 1985, S. 528-543.

- Marian Bisanz-Prakken: Gustav Klimt - Der Beethovenfries. Geschichte, Funktion und Bedeutung, 1977.

Trees and Forests

Gustav Klimt: Pine Forest I, 1901, Kunsthaus Zug

© Kunsthaus Zug, Stiftung Sammlung Kamm

Gustav Klimt: Beech Forest I, 1902, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

© bpk | Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

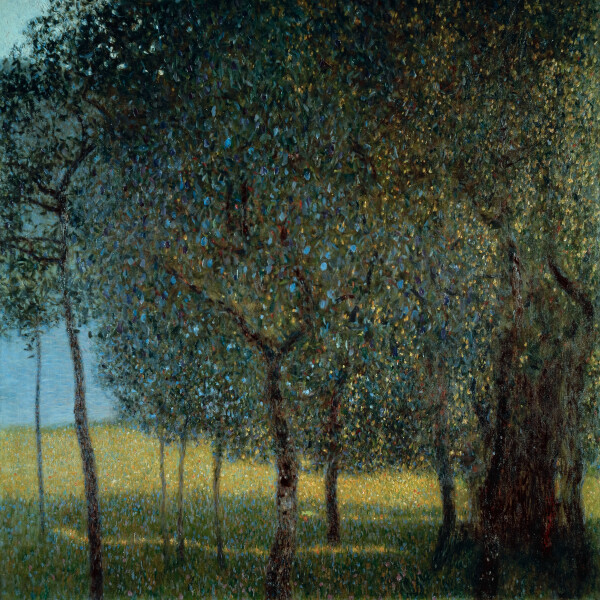

Having arrived at a personal approach to landscape painting between 1898 and 1900, Klimt made use of the motif of the forest view for stylistic experiments in the years between 1901 and 1903. A phase of Post-Impressionism and Pointillism was followed by the artist’s turn toward flatness.

Forest Views

One of the most essential innovations in Gustav Klimt’s oeuvre was the painter’s discovery of forest views in the summer of 1901. In the years up to 1904 he painted as many as altogether five forest pictures, all of which seem to depict motifs from the surroundings of the Bräuhof in Litzlberg on the Attersee: Pine Forest I (1901, Kunsthaus Zug), Pine Forest II (1901, private collection), Beech Forest I (c. 1902, Staatliche Kunstsammlung, Dresden), Beech Forest II (Beech) (1903, private collection), and Birch Forest (Beech Forest) (1904, private collection). Next to orchards, which were already an established motif in his oeuvre, thick spruce and beech forests followed as the second characteristic subject matter of those years.

In his review of the “XIII. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession” [“13th Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists Secession”], Ludwig Hevesi found apt words to describe Pine Forest I and Pine Forest II on 13 February 1902:

“A number of vertical trunks, seemingly all the same, like columns in a church, seemingly an orderless throng of long, vertical things. But, indeed, thoroughly composed groups and perspectives, spatial life, air, twilight. [...] Just observe the delicate breakthroughs of sunny air in one of his two forest pictures, which at first sight merely seem to be dark thickets.”

What critics like Richard Muther admired about the forest views was how Klimt placed spots of light and color. Although the motifs did not differ from those of other painters, they would be recognizably “Klimt” at first glance. The Viennese painter had developed a personal signature style, from the choice of the square picture format to a delicate manner of painting composed of subtle strokes and dabs.

Gustav Klimt: The Large Poplar II (Gathering Storm), 1902/03, Leopold Museum

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Fruit Trees, 1901, private collection

© Gallery Welz Salzburg

Poplar on the Attersee

In Island in the Attersee (1902, private collection) and The Large Poplar II (Gathering Storm) (1902, Leopold Museum, Vienna), the artist revisited two compositions from 1900. Klimt’s dealing not only with Claude Monet’s Impressionism but also with the possibilities offered by Pointillism led to breathtaking compositions. Frequently, Klimt’s change in style is also explained by his studying the art of Giovanni Segantini and Théo van Rysselberghe, whose works he knew not only from the Vienna Secession’s exhibitions. Both works differ from the dominant forest views and orchards from that same phase by their widening space. The eye is allowed to wander into the depth of the landscape without being held up. In these works, Klimt nevertheless puts the possibilities of an increasingly two-dimensional or flat rendering of nature to the test.

In Island in the Attersee, while revisiting the motif of the painting On the Attersee (1900, Leopold Museum, Vienna), Klimt moves the island of Litzlberg, which is overlapped by the upper margin of the picture, somewhat more into the picture. The castle located on the island is again blocked from view. Instead, Gustav Klimt concentrates on rendering the play of waves in the foreground and the reflection of the island in the middle ground, which in literature is referred to as “vegetabilization.” As was to be seen for the first time in the two works dating from the previous year – Farmhouse in Kammer on the Attersee (Mill) (1901, private collection) and Fruit Trees (1901, private collection) – Klimt increasingly turned to the Impressionist and Pointillist style in his landscapes.

In The Large Poplar II (Rising Thunderstorm), he combined the gossamer and, at first glance, naturalistic depiction of cumulus clouds with a dab-like treatment of the foliage. The autumnal trees – unique in Klimt’s entire oeuvre – shimmer in shades of green, blue, violet, red, and orange. The candle shape of the eponymous poplar and its position within the picture are reminiscent of Vincent van Gogh’s late landscapes featuring lambent cypresses. The low horizon is unusual for a landscape by Klimt, yet it allows him to describe the mood of the gathering storm in the form of dark clouds. Upon closer inspection it is noticeable that colored layers are worked into the gray of the cloud masses, lending the composition its coloristic equilibrium.

Gustav Klimt: Pear Tree, 1903, Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Cambridge

© President and Fellows of Harvard College

Gustav Klimt: The Golden Apple Tree, 1903, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

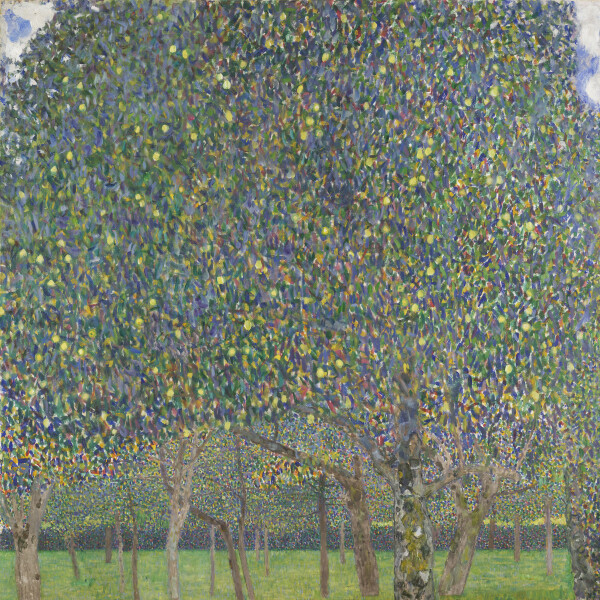

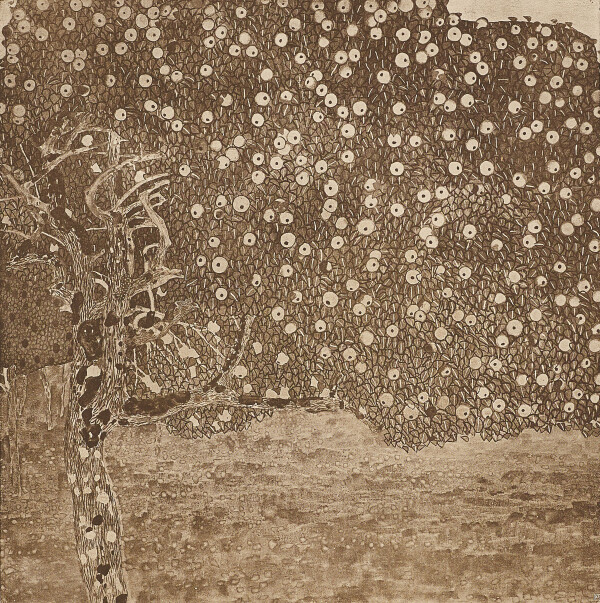

Fruit Trees

In 1903 the Viennese painter devoted himself to pear and apple trees, whose rich fruit he used for stylistic experiments: Pear Tree (1903, Harvard Art Museum/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Cambridge) and The Golden Apple Tree (1903), which was destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945. In both paintings, the fruit trees are approached in a Pointillist play of dots on the one hand and as gilded stylization on the other. In its composition, Pear Tree follows the painting Fruit Trees from 1901. If in the earlier painting he still lets the lake flash in the background, in Pear Tree (Pear Trees) he organizes the landscape in horizontal stripes. The treetops obscure the view into the sky, while the trunks close off the garden parallel to the picture plane. The painting shows a noticeably thicker application of paint on the left side than in the center or on the right. This is probably due to the fact that Gustav Klimt, who gave the work to Emilie Flöge in 1903, probably worked on it until his death.

One year after the Beethoven Frieze (1901/02, Belvedere, Wien), in which Klimt took the use of flatness, gold leaf, and rhythmic linearity to a first climax, he also applied these stylistic principles to the depiction of a single tree. Although the composition of the Golden Apple Tree has survived only in a black-and-white reproduction, it can be classified stylistically due to the high quality of the photograph. Friedrich König’s illustration The Golden Bird may have served as a model for the formal composition, as it was published in Ver Sacrum in 1902. The design of the exuberant treetop combines inspirations from Viennese stylization art and Byzantine mosaics. The intricately ramifying tree trunk on the left side of the picture repeats painted solutions as seen in Pear Tree (Pear Trees).

It should be pointed out that landscape painting advanced to become a principal subject in Gustav Klimt’s work in the first years after 1900. The painter apparently became more financially dependent on private portrait commissions and marketable landscapes as a result of his extensive involvement with the Faculty Paintings. The landscape paintings offered him the opportunity to explore diverse stylistic possibilities of modernism and develop his art.

Literature and sources

- Ludwig Hevesi: Acht Jahre Sezession (März 1897–Juni 1905). Kritik – Polemik – Chronik, Vienna 1906.

- Stephan Koja (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Landschaften, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 23.10.2002–23.02.2003, Munich 2002.

- Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sommerfrische am Attersee 1900-1916, Vienna 2015.

- Toni Stoos, Christoph Doswald (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Ausst.-Kat., Kunsthaus Zurich (Zurich), 11.09.1992–13.12.1992, Stuttgart 1992.

- Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Chiffre: Sehnsucht – 25. Gustav Klimts Korrespondenz an Maria Ucicka 1899–1916, Vienna 2014.

- Richard Muther: Klimt (1903), in: Aufsätze über bildende Kunst, Band I, Berlin 1914.

Viennese Society Portraits

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Rose von Rosthorn-Friedmann, 1900/01, private collection

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

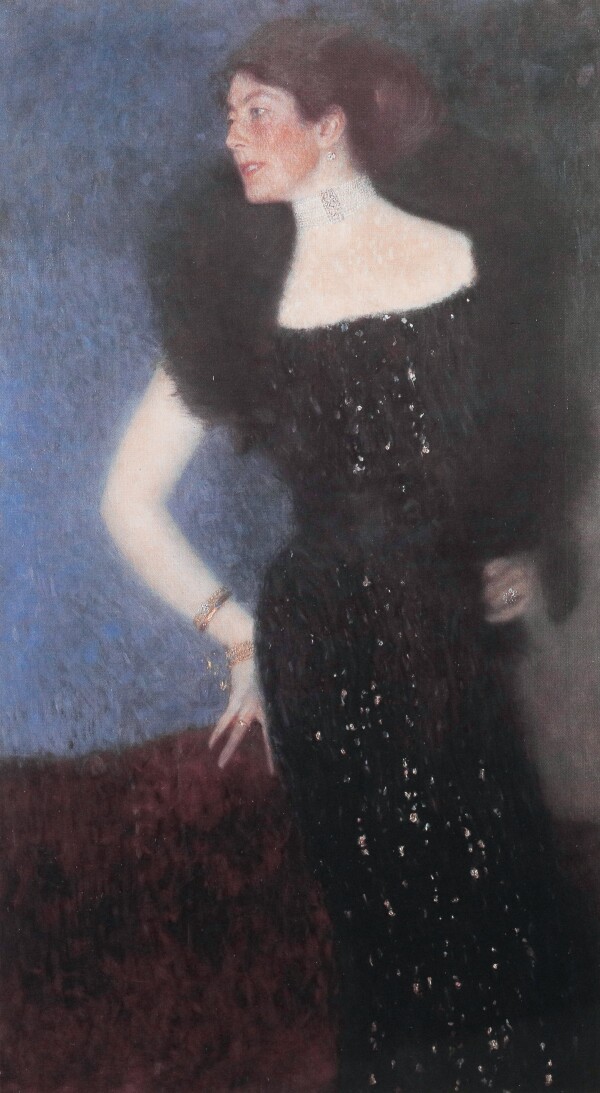

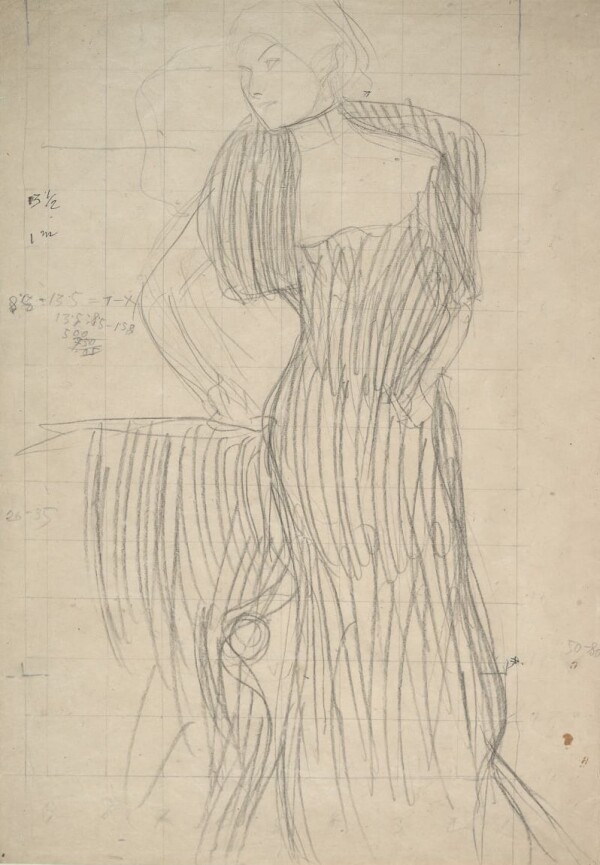

From 1900 onwards, Gustav Klimt increasingly established himself as a portraitist of the upper echelons of Viennese society. Above all, his ability to capture the latest fashion trends on canvas in a gossamer painting style quickly became his personal signature. Successively introducing more ornamentation in his portraits, Klimt already anticipated the two-dimensionality of his subsequent works.

The avant-gardist, who had become internationally famous around 1900 due to the scandal surrounding the Faculty Painting of Philosophy (1900–1907, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945), was able to convince a small circle of extremely wealthy, modern-minded Viennese of his art. Gustav Klimt’s works were particularly popular with the ladies of the upper middle classes. Between 1901 and 1903, he created one to two monumental portraits per year, thus arriving at a rhythm he would maintain for the rest of his life. The female portraits dating from this period are characterized by a gossamer painting style and voluminous dresses shimmering in powdery tones.

Rose von Rosthorn-Friedmann

The Portrait of Rose von Rosthorn-Friedmann (1900/01, private collection) was considered lost for a long time and was last exhibited in 1992. The sitter was the daughter of an industrialist whose family originally came from England. In 1886 she married her second husband, the industrial tycoon Louis Friedmann. Together with her husband, she undertook numerous mountain tours and was one of the most important alpinists of her time. The couple frequented Vienna’s artistic circles and cultivated friendships with such personalities as Arthur Schnitzler and Hugo von Hofmannsthal.

Gustav Klimt depicted Rose von Rosthorn-Friedmann as a sophisticated and elegantly dressed woman. He prepared the painting in several figure studies in which he dealt primarily with the position of her arms. In addition, he made a transfer sketch (1900/01, Albertina, Vienna, S 1980: 511), which was already very close to the executed work. Klimt opted for an upright standing position and a strongly twisted upper body. He clad the sitter in a fitted black evening dress that appears to be embroidered with sequins. Over her shoulders she wears a fur bolero, and the glitter of her robe is repeated in her jewelry: a multistranded pearl choker, earrings, bracelets, and rings.

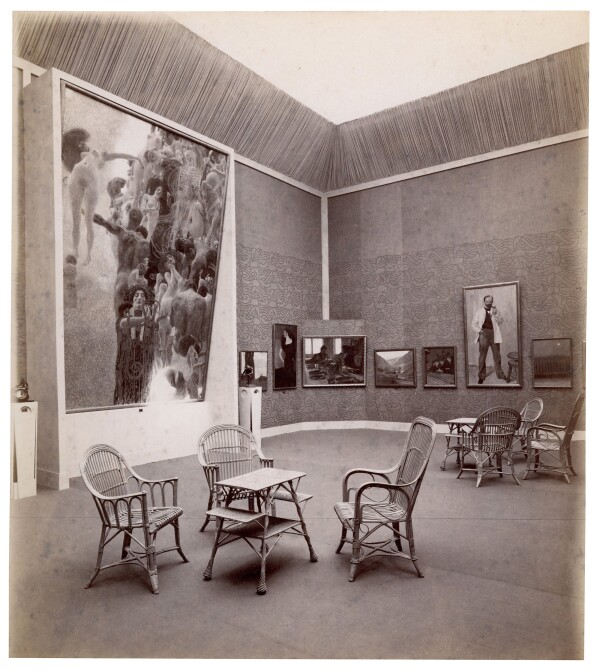

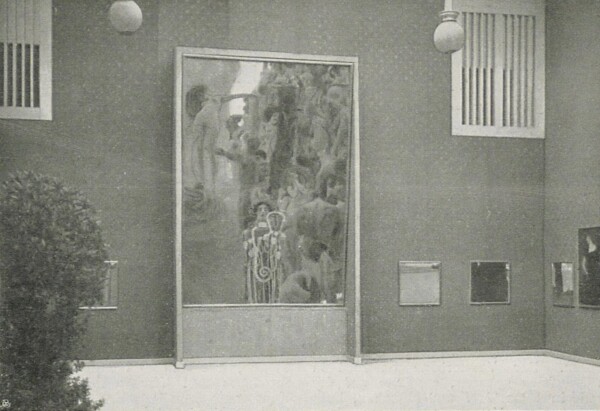

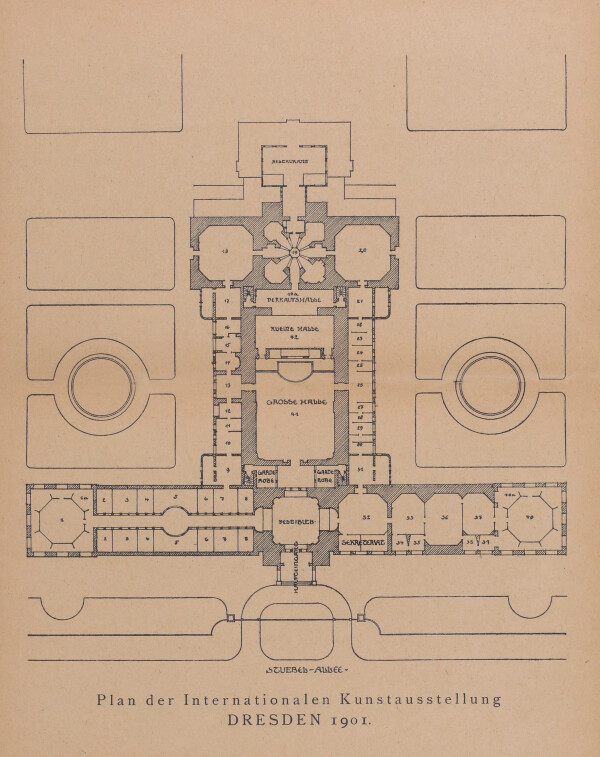

Insight into the VIII. International Art Exhibition in Munich, June 1901 - October 1901, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna

The portrait was first shown in March 1901 at the “X. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession” [“10th Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists Secession”] alongside such paintings such as Medicine (1900–1907, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945) and The Large Poplar II (1902/03, Leopold Museum, Vienna). Franz Servaes reviewed the exhibition in the Neue Freie Presse and described the work and the sitter’s jewelry:

“It is wonderful how the shimmering violet of the background caresses the naked, propped-up arm and the dark robe covered with glitter. And gold bracelets, pearls, and jewels shine mysteriously.”

A letter Gustav Klimt wrote to Louis Friedmann in July 1901 also provides an interesting insight in this regard:

“[I] took the liberty of writing a letter to your honorable wife [to which I] have unfortunately received no reply to date, and in which I asked her where to send the three bracelets that are still here with me, for I would like to go to the countryside and would not think it wise to keep them here.”

Portrait of Rose von Rosthorn-Friedmann is also related to Water Nymphs (Silverfish) (1902/03, Albertina, Vienna), both formally and thematically. The sitter’s face closely resembles the nymph depicted in the foreground.

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Marie Henneberg, 1901/02, Kunstmuseum Moritzburg Halle (Saale) – Kulturstiftung Sachsen-Anhalt

© Kulturstiftung Sachsen-Anhalt – Kunstmuseum Moritzburg Halle (Saale)

Marie Henneberg

Marie Henneberg was the wife of Hugo Henneberg, a chemist and amateur photographer, who at the turn of the century established himself as one of the most important practitioners of Pictorialism, exhibiting at the Vienna Secession. In the spring of 1899, the couple joined a travel party led by the Moll family to Italy, which was also joined by Gustav Klimt. In 1900/01 the Hennebergs had a villa built by Josef Hoffmann in what was referred to as an artists’ colony on Hohe Warte and thus lived in the immediate vicinity of Carl Moll, Kolo Moser, and Friedrich Viktor Spitzer. The house became a meeting place of modernism in Vienna.

An acquaintance of the couple, Gustav Klimt painted the square-format Portrait of Marie Henneberg (1901/02, Staatliche Galerie Moritzburg, Halle an der Saale), which depicts her seated in an armchair. It was first presented in 1902 – in a still unfinished state – at the “XIII. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession” [“13th Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists Secession”]. This was followed in 1903 by the “Klimt-Kollektive” or “Kollektiv-Ausstellung Gustav Klimt” [“Gustav Klimt Collective Exhibition”], where Ludwig Hevesi described the work as “[...] the lady in white frillwork; the seated one in pale purple, with a bouquet of violets.” That same year, the magazine Das Interieur published several photographs of Villa Henneberg showing the painting in situ in the villa’s spacious entrance hall.

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Gertrud Loew, 1902, The Lewis Collection, in: Kunstverlag Hugo Heller (Hg.): Das Werk von Gustav Klimt, Vienna - Leipzig 1918.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

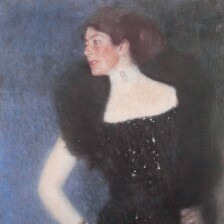

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Emilie Flöge, 1902/03, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

The portrait can be assigned to a whole group of brightly dressed ladies – works in which Klimt increasingly explored the latest developments in Post-Impressionism and Pointillism. Both the dominance of tones in lilac and light blue and the growing dissolution of the armchair in favor of a colored composition show how Klimt adopted the innovations of the French and Belgian avant-garde for his own style.

Gertrud Loew

Gertrud Loew was the daughter of the physician Dr. Anton Loew, founder of the renowned Viennese private hospital Sanatorium Loew. He was an advocate of modern art and owned several works by Klimt. Most likely it was he who, around 1902, also commissioned from Gustav Klimt a portrait of his then 19-year-old daughter. It may have been an engagement present, as Gertrud Loew married the industrial magnate Dr. Hans Eisler von Terramare in February 1903. The couple moved into a modern apartment on Schottenring, furnished by Kolo Moser and committed to the idea of the Secessionist Gesamtkunstwerk [universal work of art].

It seems that no preliminary studies have survived for Portrait of Gertrud Loew (1902, The Lewis Collection). The work was first presented in 1903 as part of the “Klimt-Kollektive” at the Secession. The lender was Anton Loew, who asked the Secession in writing to label the “Portrait of a Lady” and other works provided by him as anonymous loans from a “private collection.” Ludwig Hevesi compared the exhibited painting with the Portrait of Rose von Rosthorn-Friedmann:

“Just look at the nervously pointed nature of the lady in black painted a few years ago and, by contrast, the very young white Fräulein of this year, a pure breeze, with the four pale lilac silk ribbon stripes running down the flimsy, crinkled dress. Each stripe meanders differently in the iridescent fall of the fabric; a coincidence in which lies the finest painterly plan.”

With Gertrud Loew, Klimt developed the portrait type he had established with Portrait of Serena Lederer (1899, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) and Portrait of Trude Steiner (1900, whereabouts unknown). By way of comparison, however, the sitter now occupies almost the entire pictorial space of the extremely narrow vertical format, which betrays an influence of Japanese art. Through Gertrud Loew’s frontal view, the tightly cropped composition, and the tonality of the light-colored dress, which continues in the background, Klimt emphasized the two-dimensionality of the work. In the upper left corner, he added his signature and the date “1902” within two green squares reminiscent of signature stamps in Japanese woodcuts.

Emilie Flöge

Due to their family connections, there was a close bond between Klimt and Emilie Flöge over many years. Together with her sisters Pauline and Helene, the widow of Klimt’s elder brother Ernst, she opened the fashion salon “Schwestern Flöge” on 1 July 1904. She was in charge of the management of the salon in artistic and fashion matters. The company’s customers included art-savvy and fashion-conscious ladies of high society such as Sonja Knips, Hermine Gallia, and Eugenia Primavesi, who were also associated with Gustav Klimt as the artist’s patronesses.

The genesis of the painting Portrait of Emilie Flöge (1902/03, Wien Museum, Vienna) cannot be accurately reconstructed due to a lack of drawn studies, among other things. Klimt signed and dated the work in a way similar to that of Portrait of Gertrud Loew, inscribing two square signets with “Gustav Klimt 1902.” However, the two paintings, which were created around the same time, differ greatly: unlike the ethereal, powdery appearance of Gertrud Loew, the portrait of Emilie Flöge is dominated by powerful colors, ornamented surfaces, and the use of gold and silver. Slightly twisted, Flöge stands in an undefined space wearing an ornamentally patterned dress whose two-dimensionality contrasts with her naturalistic facial features. Ludwig Hevesi referred to Flöge as seen in the painting as “the upright one, à la Japan and faience in blue, green, and gold.” It was first exhibited in an unfinished state in November 1903 at the “Klimt-Kollektive” at the Secession. Berta Zuckerkandl went into further detail about the work in the Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung:

“The charming, subtly and delicately modeled face is further elevated by the rare framing. The head is surrounded by an aureole-like green and blue floral wreath that has the coloristic mysticism of Byzantine backgrounds.”

While the exhibition was still on, Klimt corresponded about the unfinished portrait. In a letter of 17 January 1904 he replied to a purchase request from the Imperial-Royal Ministry for Culture and Education:

“[I] had not intended to sell the portrait of Miss Flöge. But as in the present case it would possibly be acquired for the State Gallery, I am prepared to sell the picture for the Modern Gallery with the consent of its owner as soon as it has been completed. The price will be the same I now receive for a portrait commission, 10,000 crowns.”

The sale probably did not materialize due to the high price, and Klimt completed the painting no later than the summer of 1908, when it was purchased by the Niederösterreichisches Landesarchiv [Lower Austrian State Archives].

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Hermine Gallia, 1903/04, The National Gallery

©

Hermine Gallia

Portrait of Hermine Gallia (1903/04, National Gallery, London) shows the wife of the wealthy businessman Moritz Gallia, who, among other things, served as president of the Wiener Werkstätte. Together, the couple also supported the Vienna Secession, championed the founding of the Moderne Galerie [Modern Gallery] (now Belvedere, Vienna), and passionately collected art.

Klimt’s portrait of Hermine Gallia was a direct continuation of the portrait of Marie Henneberg, which he prepared around 1902/03 with a number of studies. Originally conceived in a seated position, Klimt decided, to depict Hermine Gallia standing. In the upright-format painting, the sitter is set off against the dark background and looks out of the picture in a slightly twisted pose. She wears an elaborately designed evening gown with a cape-like boa – a so-called “ball entrée” – with ruffles, flounces, and a train draped effectively in the foreground. Transparent and light-colored sections iridesce and are accented by a pink sash around the sitter’s waist, as well as glittering, stone-studded jewelry. Not only did Klimt execute the background in a style similar to that employed for the portrait of Emilie Flöge, he also repeated the geometric shapes, although here he integrated them very subtly into the patterned carpet on the floor.

The work was shown for the first time in 1903 at the “XVIII. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession Wien” [“18th Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists Vienna Secession”]; in the accompanying catalog it was listed as “38. Portrait of a Lady. Private collection. Unfinished.” Both the number and the unfinished state were also documented in the form of a photograph of the work when it was installed at the Secession during the exhibition. After the presentation, Klimt changed only a few details in the hairstyle and face and then added his signature and the date 1904 in the already familiar square signet in the upper right corner of the picture.

Literature and sources

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012.

- Tobias G. Natter, Gerbert Frodl (Hg.): Klimt und die Frauen, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 20.09.2000–07.01.2001, Cologne 2000.

- Ernst Ploil: The Portrait of Gertha Loew, in: Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Klimt and the Women of Vienna's Golden Age. 1900–1918, Ausst.-Kat., New Gallery New York (New York), 22.09.2016–16.01.2017, London - New York 2016, S. 96-101.

- Franz Servaes: Secession. Eine Porträtgalerie. Gustav Klimt, in: Neue Freie Presse, 19.03.1901, S. 1-3.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band I, 1878–1903, Salzburg 1980, S. 158-163, S. 216-219, S. 292-299.

- Rohrpost-Kartenbrief von Gustav Klimt in Wien an Louis Friedmann in Wien (07/30/1901). S538.

- Gerd Pichler, Joseph Maria Olbrichs nie gebaute Künstlerkolonie in Wien und Josef Hoffmanns Künstlerkolonie auf der Hohen Warte.. journals.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/index.php/icomoshefte/article/view/46883/40388 (05/18/2020).

- Ludwig Hevesi: Weiteres zur Klimt-Ausstellung. 21. November 1903, in: Acht Jahre Sezession (März 1897–Juni 1905). Kritik – Polemik – Chronik, Vienna 1906, S. 448–452.

- Gerd Pichler: Kolo Mosers »Wohnung für ein junges Paar« - Gerta und Dr. Hans Eisler von Terramare, in: Rudolf Leopold, Gerd Pichler (Hg.): Koloman Moser 1868−1918, Ausst.-Kat., Leopold Museum (Vienna), 25.05.2007–10.09.2007, Munich 2007, S. 174-201.

- Visitenkarte von Anton Loew an die Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs (10/22/1903). 24.4.2_Loew Anton_5861, .

- Brief von Gustav Klimt in Wien an das k. k. Ministerium für Kultus und Unterricht, verfasst von fremder Hand (presumably 01/17/1904). AT-OeStA/AVA Unterricht UM, Fasz.15 Kunstwesen, Ankauf, Akt ZI 4197/1904 Fasz 3060, Klimt, Flöge, fol. 2, .

- Berta Zuckerkandl: Die Klimt-Ausstellung, in: Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung (Abendausgabe), 15.11.1903, S. 6-7.

- Rechnungsbestätigung von Gustav Klimt an den Niederösterreichischen Landesausschuss in Wien (06.07.1908). NÖ Landesarchiv, Nö. Landesregistratur, IV-42 1908, zu Zl. 2/1, fol.8.

- biografiA. Rose Rosthorn. www.biographien.ac.at/oebl_9/270.pdf (05/05/2020).

- Die Kunst. Monatshefte für freie und angewandte Kunst, Band 10 (1903/04), S. 355.

- Ursula Storch (Hg.): Klimt. Die Sammlung des Wien Museums, Ausst.-Kat., Vienna Museum (Vienna), 16.05.2012–07.10.2012, Vienna 2012, S. 206-207.

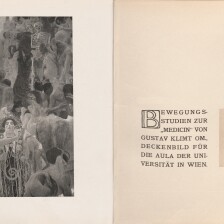

Faculty Paintings. Medicine and Jurisprudence

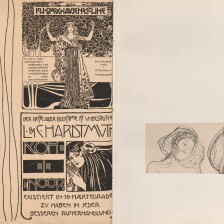

Gustav Klimt: Medicine, 1900-1907, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt, in: Vereinigung bildender KünstlerInnen Wiener Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Mitteilungen der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 4. Jg., Heft 6 (1901).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Medicine (Study), 1898 (überarbeitet: 1898), The Israel Museum

© The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

Gustav Klimt: The medicine (transfer sketch), circa 1900, The Albertina Museum

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Medicine, 1900-1907, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt, in: Max Eisler (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Eine Nachlese, Vienna 1931.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Jurisprudence (Study), 1897/98, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt

© Gallery Welz Salzburg

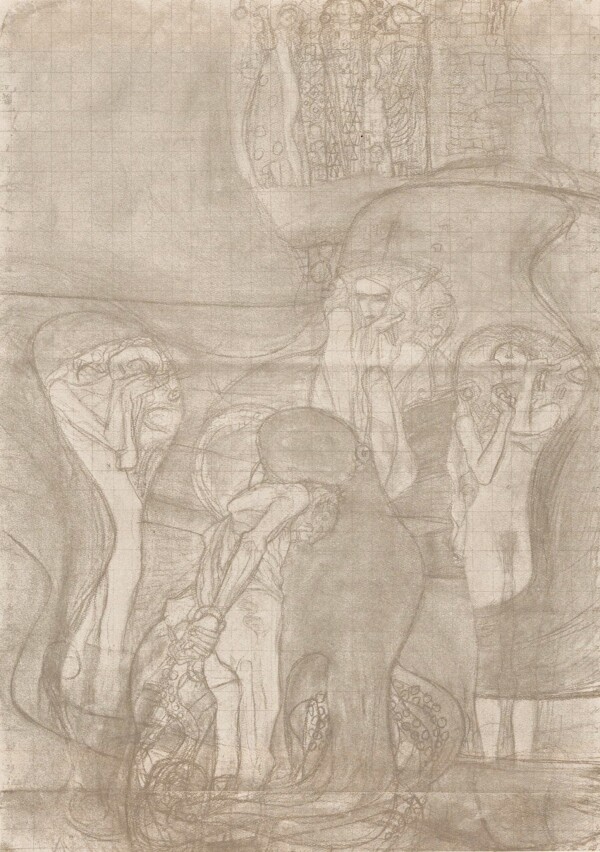

Gustav Klimt: Jurisprudence (transfer sketch), 1902/03, private collection, in: Vereinigung bildender KünstlerInnen Wiener Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Mitteilungen der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 6. Jg., Sonderband 3 (1903).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

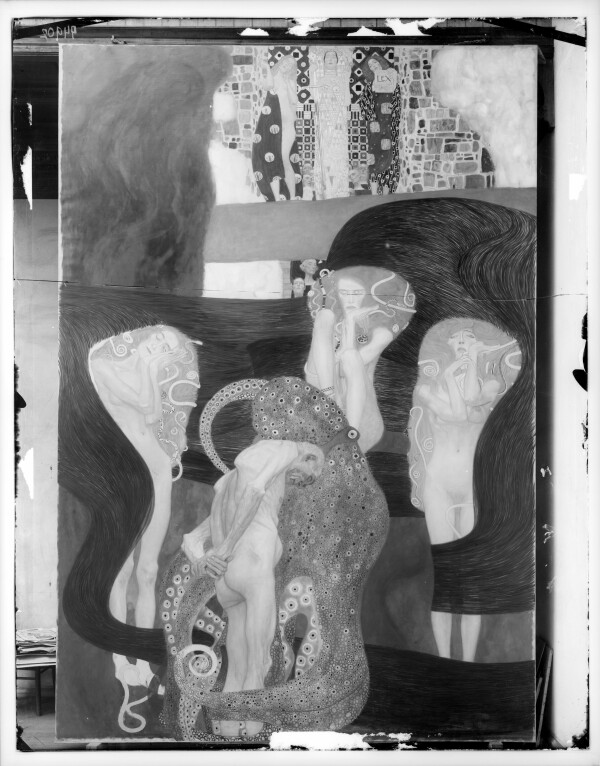

Moriz Nähr: Jurisprudence, spring 1903 - fall 1903, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

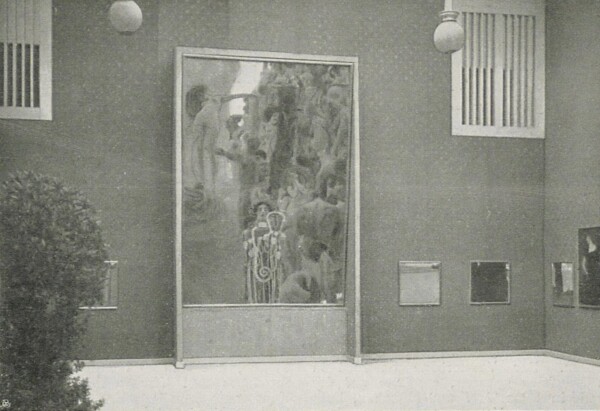

Insight into the Xth Secession Exhibition, March 1901 - May 1901, in: Die Kunst für Alle. Malerei, Plastik, Graphik, Architektur, 16. Jg. (1900/01).

© Heidelberg University Library

Insight into the VIII. International Art Exhibition in Munich, June 1901 - October 1901, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna

Vereinigung bildender KünstlerInnen Wiener Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Gustav Klimt. XVIII. Ausstellung Nov.=Dez. 1903 Secession Wien, Ausst.-Kat., Secession (Vienna), 15.11.1903–06.01.1904, Vienna 1903.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Moriz Nähr: Insight into the XVIII Secession Exhibition, November 1903 - January 1904, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Insight into the XVIII Secession Exhibition, November 1903 - January 1904, in: Die Kunst. Monatshefte für freie und angewandte Kunst, Band 10 (1903/04).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

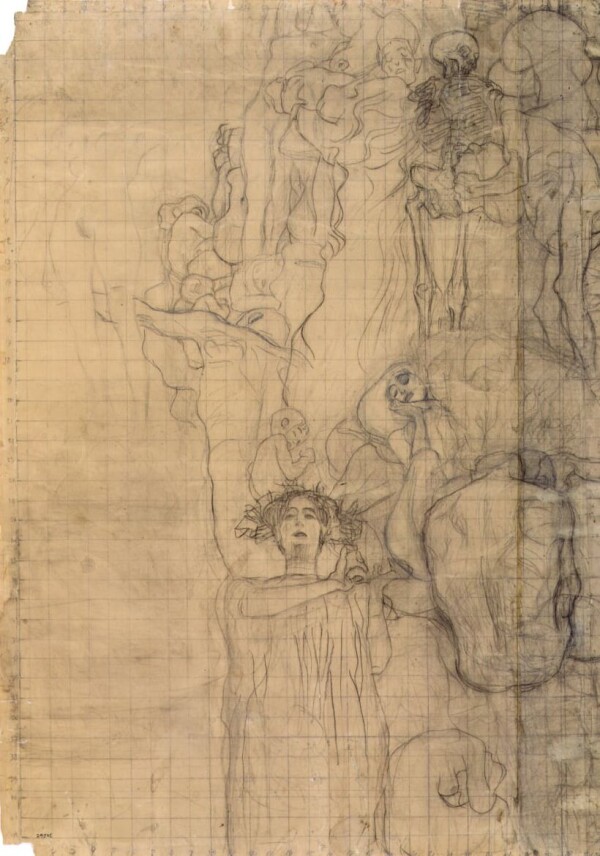

Between 1900 and 1903, Gustav Klimt worked intently on the two Faculty Paintings Medicine and Jurisprudence for the auditorium of Vienna University. When the paintings were first presented in 1901 and 1903, they caused scandals, as the Faculty Painting Philosophy had done in 1900. Following numerous alterations and additions carried out until 1907, the works were destroyed in fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945.

Medicine

Gustav Klimt epitomized Medicine (1900-1907, destroyed in a fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945) with the figure of Hygieia, the goddess of health. Seen slightly from below, she faces viewers in stringent frontality. Assuming this stance, Hygieia turns her back on suffering mankind. The Aesculapian snake is coiling around her right arm to drink from the bowl holding the water of life. Behind and above the figure of Hygieia, Klimt rendered a current of suffering mankind, with disease, pain and death – symbolized by an ailing figure and a skeleton in the upper part of the depiction – appearing within the group of mostly naked human bodies. Klimt rendered these bodies in different poses, ages and from various perspectives. In the upper right corner, we see a heavily pregnant woman with a naked belly; slightly below, a couple of men are fighting one another, while a cowering nude from behind concludes the stream of people. The left area of the painting is dominated by a hovering female nude connected to the group by her arm.

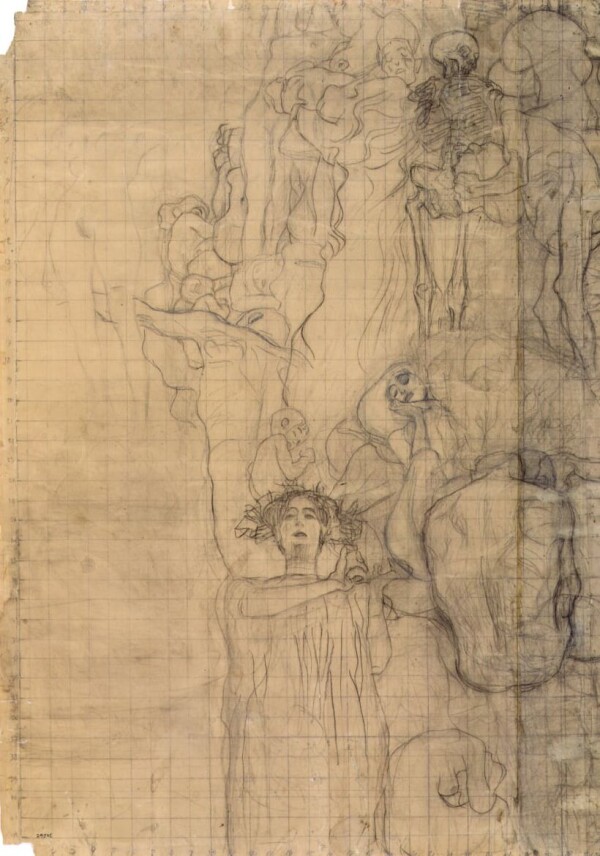

The process of creation of Medicine extended over a period of several years from the awarding of the commission in 1894: Klimt first created the oil draft for Medicine (1898, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem). This draft was heavily criticized by the academic senate as well as the artistic committee of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna and the Imperial-Royal Ministry of Culture and Education during an “art committee meeting” held in 1898. Klimt wanted to withdraw from the commission already back then. It was only after the intervention of the department’s counselor Weckbecker, who guaranteed that his “artistic freedom” would be “respected,” that Klimt agreed to sign the final contract and promised to take the committee’s change requests into account. The oil sketch was followed by the transfer sketch executed in black chalk (c. 1900, Albertina, Vienna, S 1980: 605).

When comparing the two works’ transfer sketches, it becomes apparent that Gustav Klimt assimilated the compositions of Philosophy (1900, Wien Museum, S 1980: 477) and Medicine by dividing the stream of people among both paintings. The works were meant to be mounted as counterparts onto the ceiling of the university’s auditorium, while Jurisprudence (1903–1907, destroyed in a fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945) was to be placed opposite Franz Matsch’s Theology (1900, Vienna University). Klimt had decided on this arrangement of the Faculty Paintings already around 1898/99, as a fleeting sketch that includes the ornamental area of the ceiling (1898/99, private collection) shows. The overall concept of the stream of people was likely inspired by Auguste Rodin’s The Gates of Hell (1880–1917, Musée d’Orsay, Paris), and individual figures, too, recall Rodin’s sculptural work, which Klimt knew.

Seeing as the process of creation spanned a considerable period of time, the alterations and additions Klimt made to the Faculty Paintings reflect his artistic evolution towards Symbolism. In a letter to Maria Zimmermann, written in September 1900, he reported that he had started working on the painting. In a further letter, he mentioned the attic studio on Florianigasse he had rented specifically for the execution of the Faculty Paintings, referring to it as his “altitude studio”:

“I am toiling and sweating in my ‘altitude studio.’ I won’t go to Paris, but I might be able to steal a little more time, as our exhibition already starts in October and I absolutely won’t be finished by then with my ‘Medicine’ (the first two figures for which I ‘messed up’ yesterday, by the way).”

Klimt also wrote to the Imperial-Royal Minister of Education, Wilhelm von Hartel, informing him about his progress and asking for an extension until “mid-October,” suggesting that the minister look at the painting at the Florianigasse studio.

Gustav Klimt kept working until 1907 on Medicine, which is known to us from reproductions in four different versions. The first version – which does not yet include the baby on the outer left side of the depiction – was printed in 1901 in the 6th number of the magazine Ver Sacrum, as well as in the journal Kunst für Alle in a photograph from the presentation “X. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession” [10th Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists Secession”], held in 1901, in which the painting was shown to the public for the first time. Klimt made further alterations until 1903, resulting in a second and third version, which were both documented in photographs. The third version of the painting was presented in 1903 in an exhibition by the “Klimt Collective” at the Secession. A reproduction of this version was published in a special edition of Ver Sacrum that accompanied the exhibition. The final version of 1907 was printed in 1918 in the portfolio Das Werk von Gustav Klimt [The Oeuvre of Gustav Klimt] published with Hugo Heller art publishers. A collotype print showing a detail of Hygieia featured in the 1931 portfolio Gustav Klimt. Eine Nachlese published by Max Eisler. The color reproduction gives an impression of the painting’s glowing red color and of the sections rendered in gold. When comparing the different versions of the work, we see that Klimt added the ornamental details in gold, and exchanged the original laurel wreath worn by Hygieia with a floral headdress.

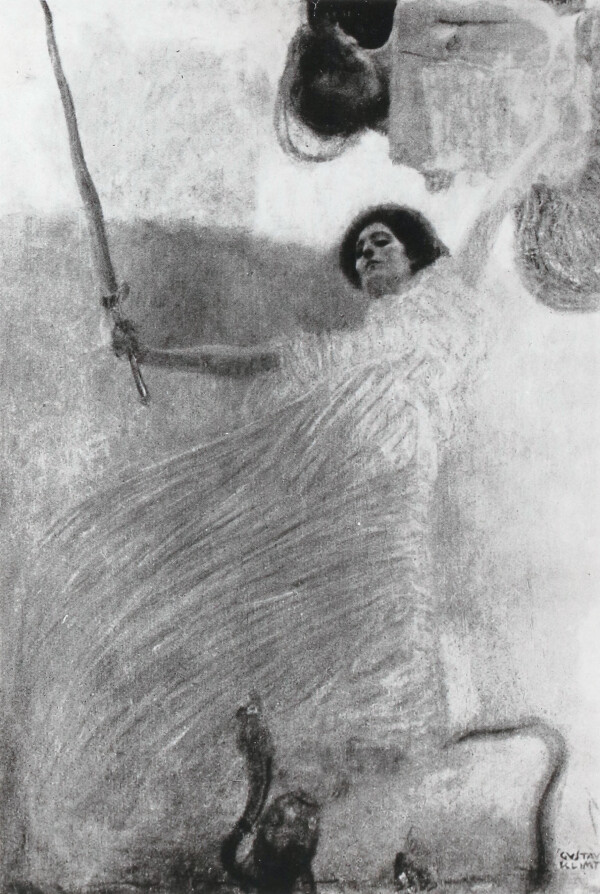

Jurisprudence

The Faculty Painting Jurisprudence (1903‒1907, destroyed in a fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945) reveals an entirely different approach to the subject than the two earlier works Philosophy and Medicine. The painted draft Jurisprudence (1897/98, destroyed in a fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945) and the transfer sketch (1902/03, private collection, S 1980: 942), drawn in 1902, have nothing in common. This illustrates the long period of time that elapsed between the works’ commissioning in 1894 and Klimt settling on the motifs and beginning the execution of the paintings. Klimt’s increasingly planar style and recourse to the “painting mosaic,” he used during what is known as his Golden Period, replaced his atmospheric, neo-Impressionist manner of painting from the fin-de-siècle and paved his way towards Symbolism. The criticism and change requests voiced by his commissioners in their 1898 “art committee meeting,” as well as the polemics against his first Faculty Paintings, had prompted Klimt to create an entirely new painting. The transfer sketch for Jurisprudence largely corresponded with the composition of the final work.

For Jurisprudence, Gustav Klimt overturned the concept he used for Philosophy and Medicine, in which the personifications of the sciences appeared in the lower edge of the depictions. He now placed the delinquent prominently into the center, surrounded by the three goddesses of vengeance from Greek mythology, the Erinyes. Far away, in the upper edge of the picture, appears the small rendering of the sword-bearing personification of justice, flanked by those of law and truth. The connection between the three goddesses of vengeance and the man, hunched with shame, is provided by a group of male heads who can be interpreted as judges. The most surprising element of this pictorial narrative is the octopus coiled around the lawbreaker.

In terms of style, the painting is shaped by Klimt’s exploration of Early Christian mosaics in Ravenna. The walls depicted in Jurisprudence reminded Ludwig Hevesi of the Upper Italian city’s architecture. The planar-linear drawing style links Jurisprudence with The Beethoven Frieze (1901/02), and was based on the style espoused by artists such as Jan Toroop and Aubrey Beardsley. The black veil, which runs like a common thread through the composition, is linked with death in reference works. The three Erinyes may either be interpreted as spawns of hell or as powers of fate from the 9th Circle of Hell from Dante’s Divina Commedia.