Klimt's work focuses on all aspects of the Art Nouveau master's oeuvre. Visualized through a timeline, Klimt's creative periods are rolled up here, starting with his training, his collaboration with Franz Matsch and his brother Ernst in the "Künstler-Compagnie", the affair surrounding the faculty paintings and his post-fame and the myth that still surrounds this exceptional artist today.

Decorator of the Ringstraße

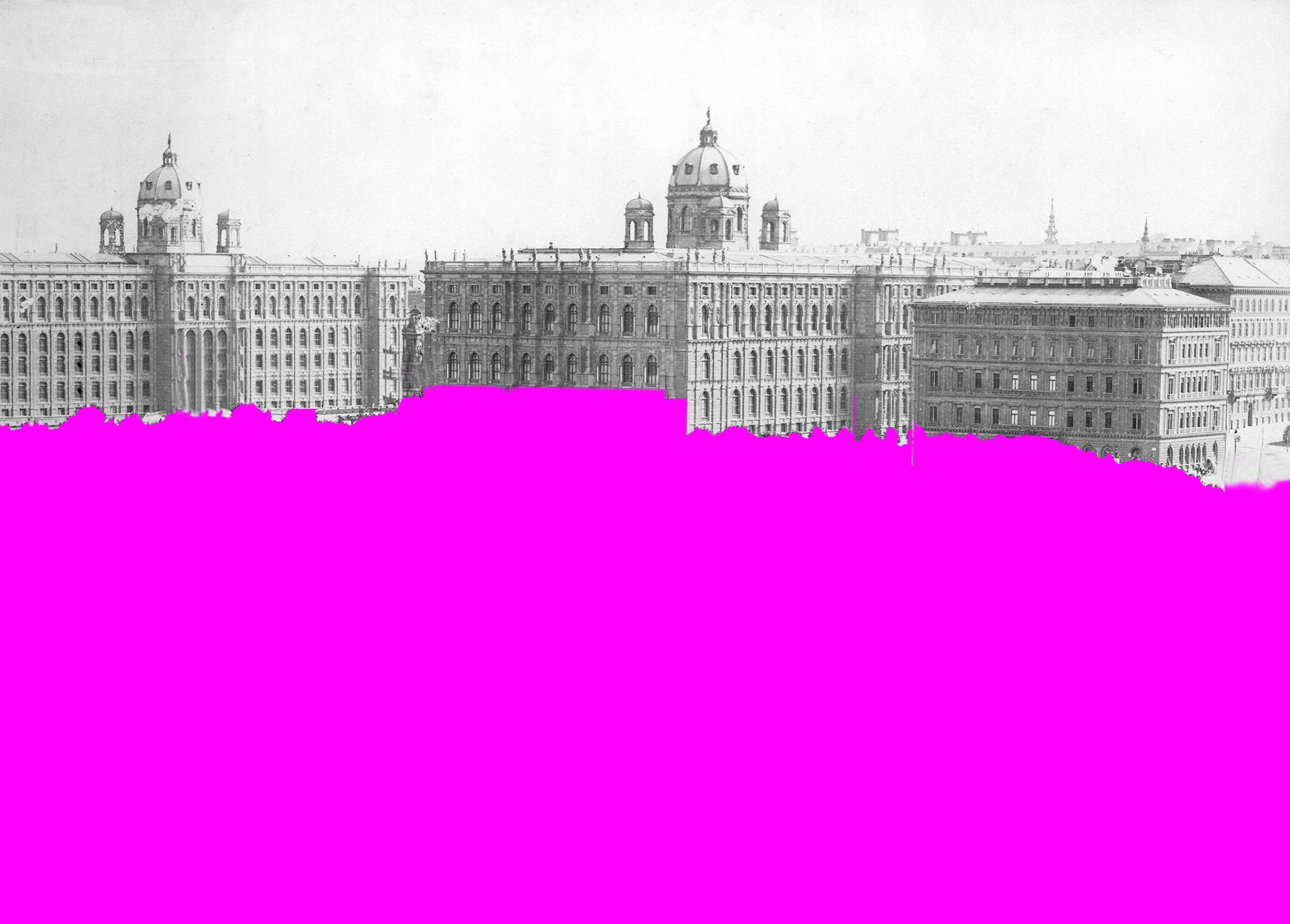

Gustav Klimt’s allegories for the staircase of the Imperial-Royal Court Museum of Art History can be considered the acme of his activities as a decorator of Ringstraße buildings. They were also his last successful commission as a decorator of a public building. At this time, Klimt began painting commissioned portraits for the bourgeoisie and became involved in the project of the Faculty Paintings for the University of Vienna.

→

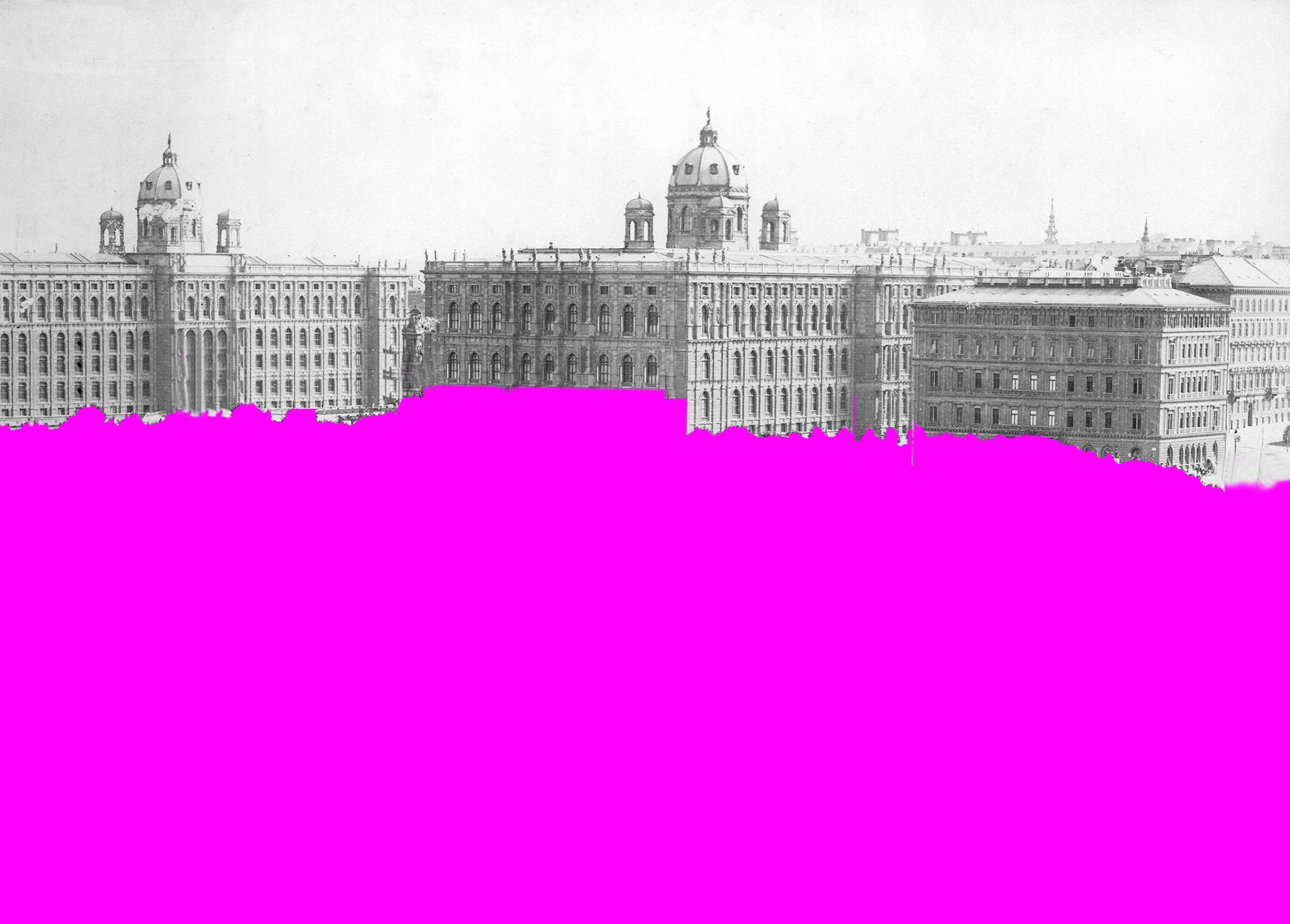

Vienna Volksgarten with the court museums, circa 1890

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Imperial-Royal Court Museum of Art History

In 1890, the “Künstler-Compagnie” was entrusted with completing the decoration in the staircase of the Court Museum of Art History. The cycle, comprising spandrel and intercolumnar panels, allegorizes major stylistic periods in the visual arts. This decoration project can be considered the acme of Klimt’s work at the threshold between Historicism and the dawn of Art Nouveau or Jugendstil.

To the chapter

→

North wall in the staircase of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

© KHM-Museumsverband

Faculty Paintings. Awarding of the Commission

In September 1894, Franz Matsch and Gustav Klimt received the commission to execute the decorative paintings for the large ceremonial hall of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna. The two artists were to complete their work within four years for a fee of 60,000 guilders.

To the chapter

→

University of Vienna Photographed by Josef Wlha, around 1885

© Wien Museum

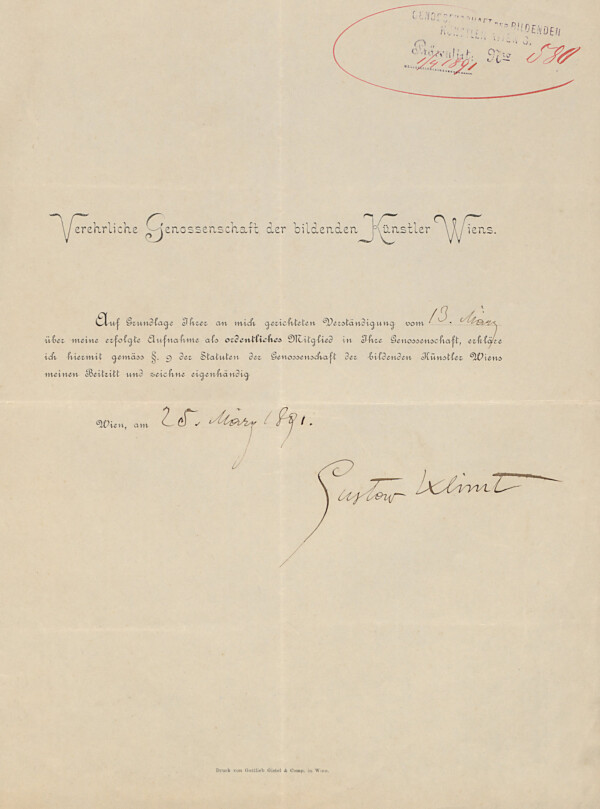

Klimt and the Vienna Künstlerhaus

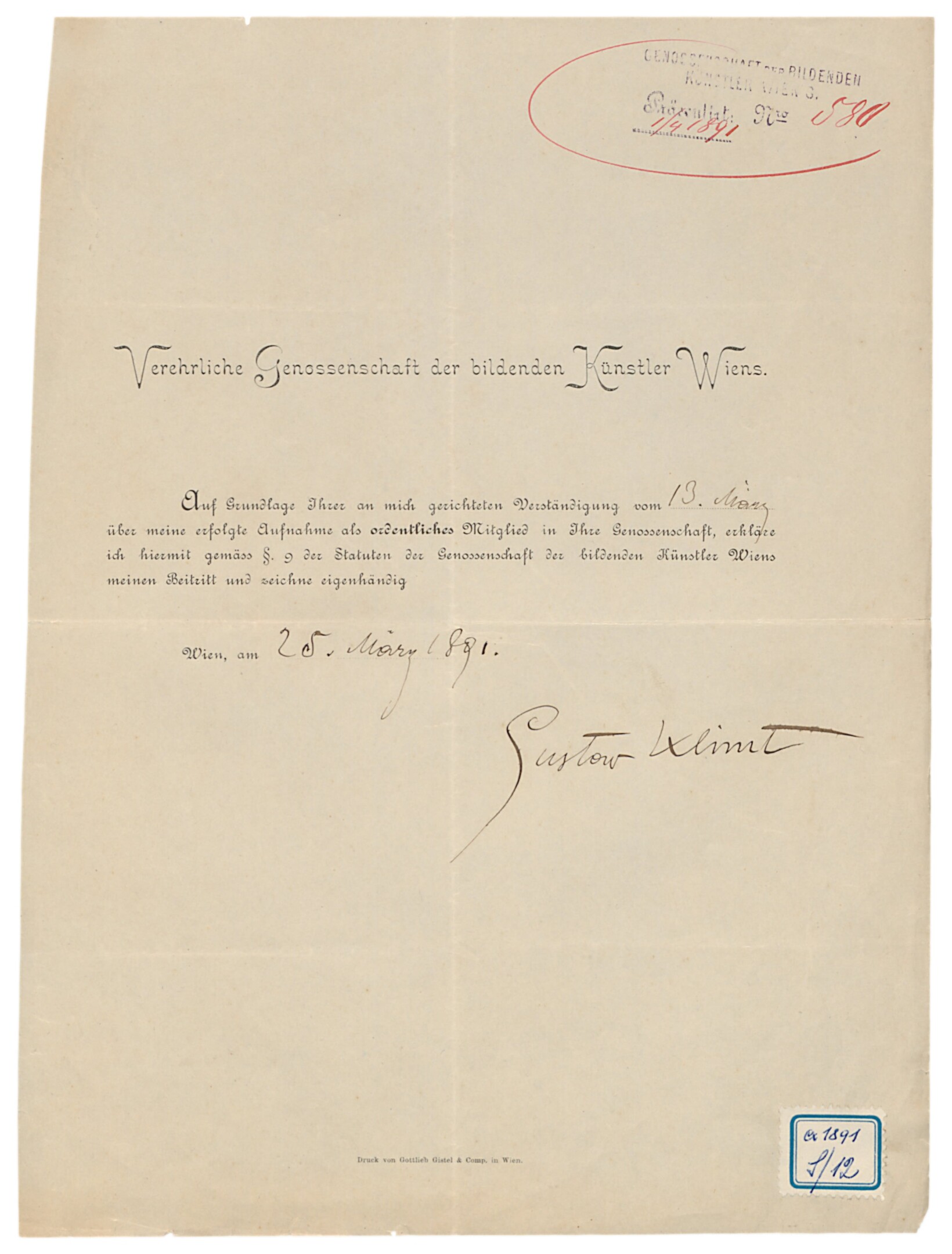

In March 1891, Gustav Klimt joined the Cooperative of Visual Artists in Vienna as a member. He was able to benefit from the institution’s network for acquiring new commissions, was appointed to various committees, and took part in numerous exhibitions, until he left the organization in 1897 in the course of the foundation of the Vienna Secession.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Gustav Klimt's Declaration of Admission to the Cooperative of Fine Artists of Vienna, 03/25/1891, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna

Homage addresses

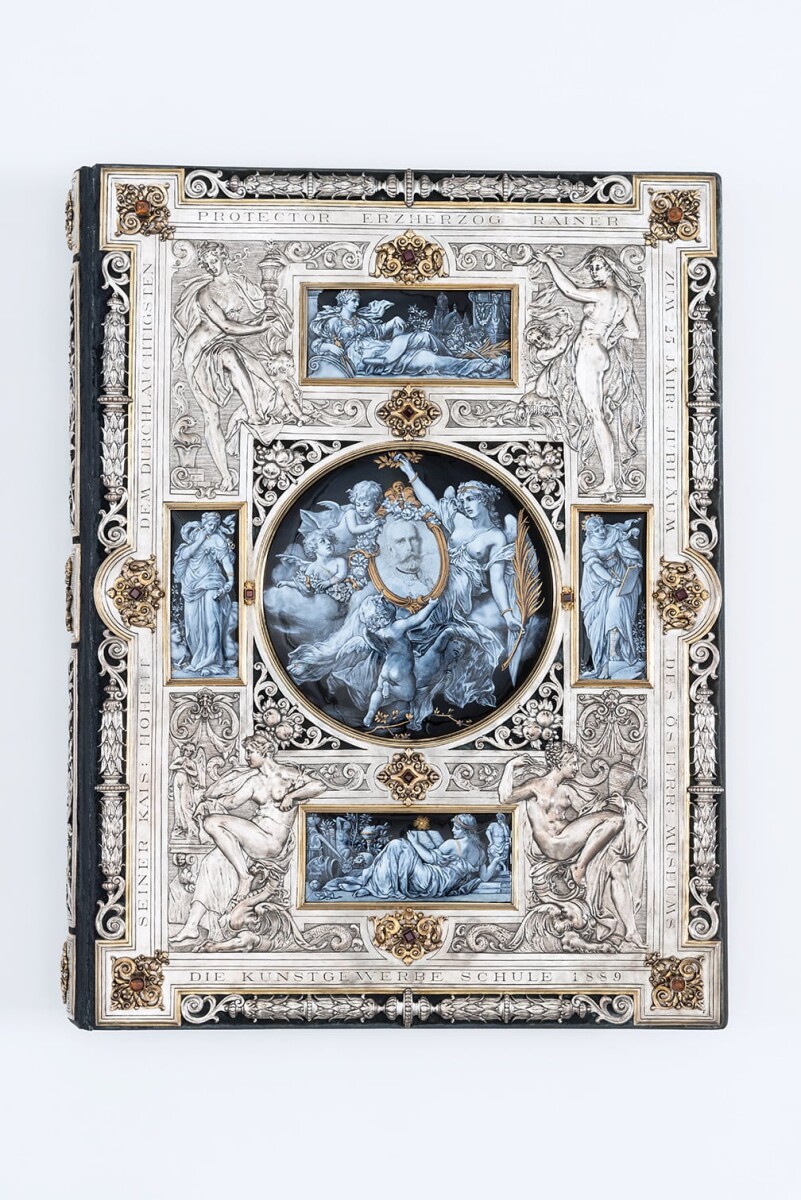

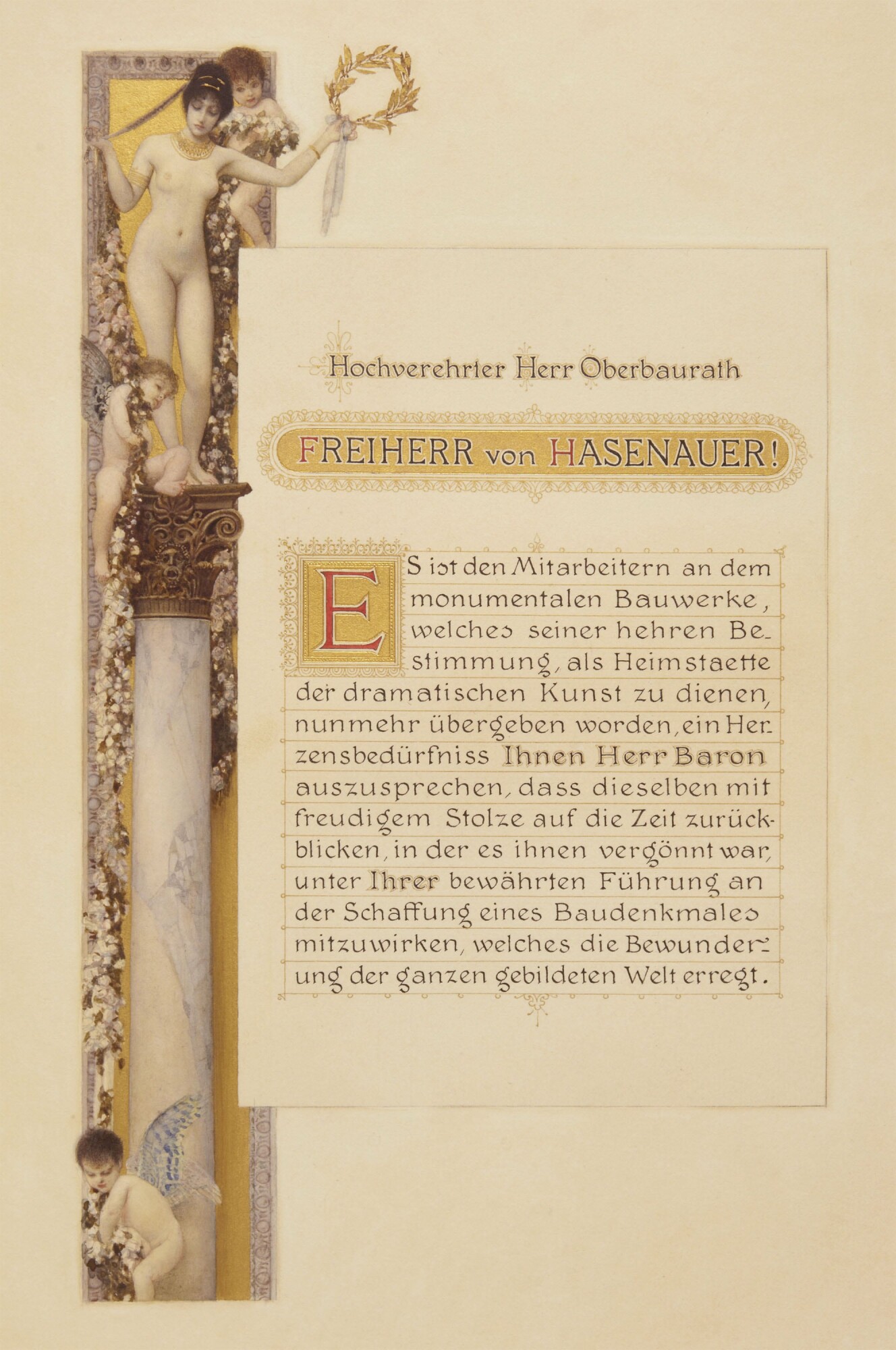

In 1888/89, Gustav Klimt was involved in the design of an homage address for Carl Hasenauer, the architect of the Imperial-Royal Court Theater, as well as a commemorative document for the 25th anniversary of the Imperial-Royal Museum of Art and Industry. In his graphic contributions, Klimt developed an increasingly stylized type of female nude.

To the chapter

→

Commemorative publication on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the Imperial and Royal Austrian Museum of Art and Industry, 1889, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

© MAK

Ernst Klimt’s Artistic Legacy

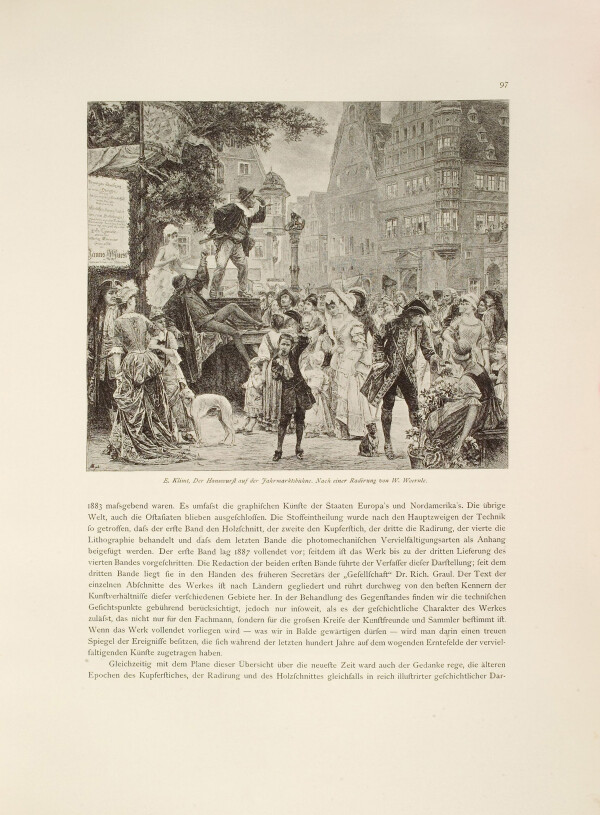

When Ernst Klimt passed away on 9 December 1892, he left the second version of his work Hanswurst Delivering an Impromptu Performance in Rothenburg unfinished. Gustav completed his brother’s oil painting, with members of the Flöge and Klimt families posing as his models.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Hanswurst Delivering an Impromptu Performance in Rothenburg, 1892-1894, private collection

© Sotheby's

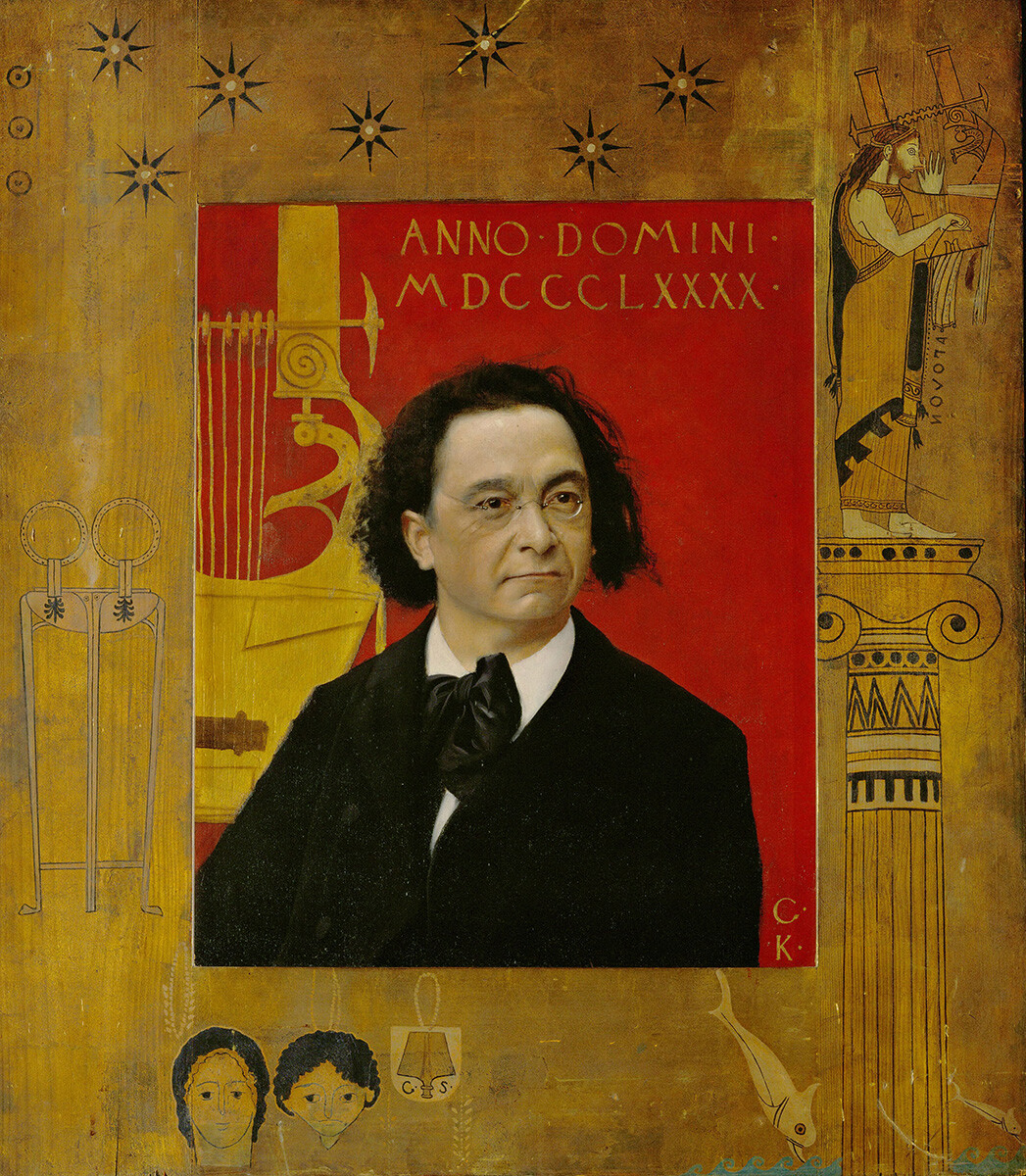

Stylized and Naturalistic Portraits

Between 1889 and 1894, the artist painted numerous naturalistic portraits. Although they are mostly characterized by an extremely realistic painting style, in some cases the first attempts of stylization and open brushwork become evident. These already point to the future development within the movement of the Secession.

To the chapter

→

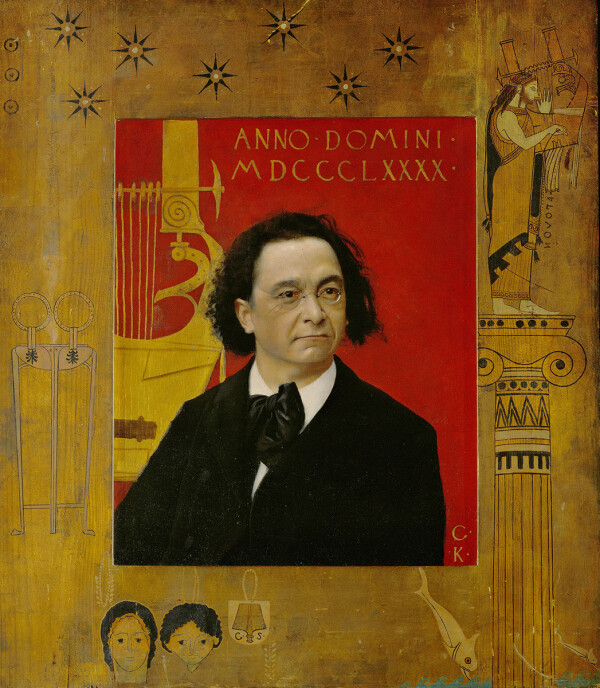

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Joseph Pembaur, 1890, Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum

© Scala Florence

Exhibition Activity

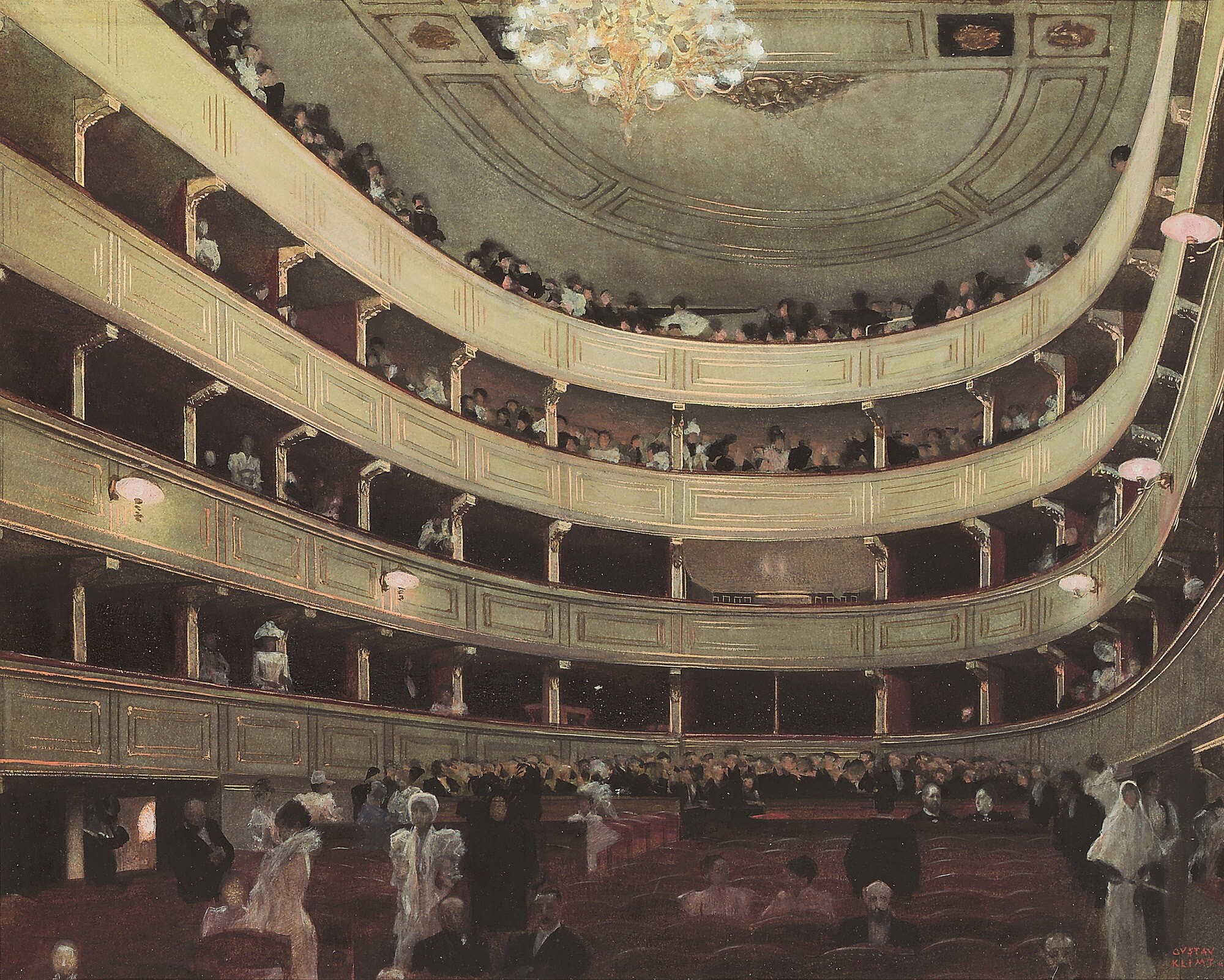

Starting on 17 November 1889, Gustav Klimt’s gouache Auditorium of the Old Burgtheater was on display together with Franz Matsch’s Interior of the Old Burgtheater for a first preview at the City of Vienna’s Historical Museum. Ten days earlier, the Neues Wiener Tagblatt had written about the works, with a special focus on an enumeration of those portrayed in the pictures.

To the chapter

→

Poster of the World Exhibition in Antwerp, 1894

© gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

Drawings

Between 1889 and 1894, Klimt created a series of watercolors, pastels, gouaches and drawings which can be regarded as complete and independent works. While Klimt would use the medium of drawing over the following years primarily for studies, many of his earlier graphic works are artworks in their own right.

To the chapter

→

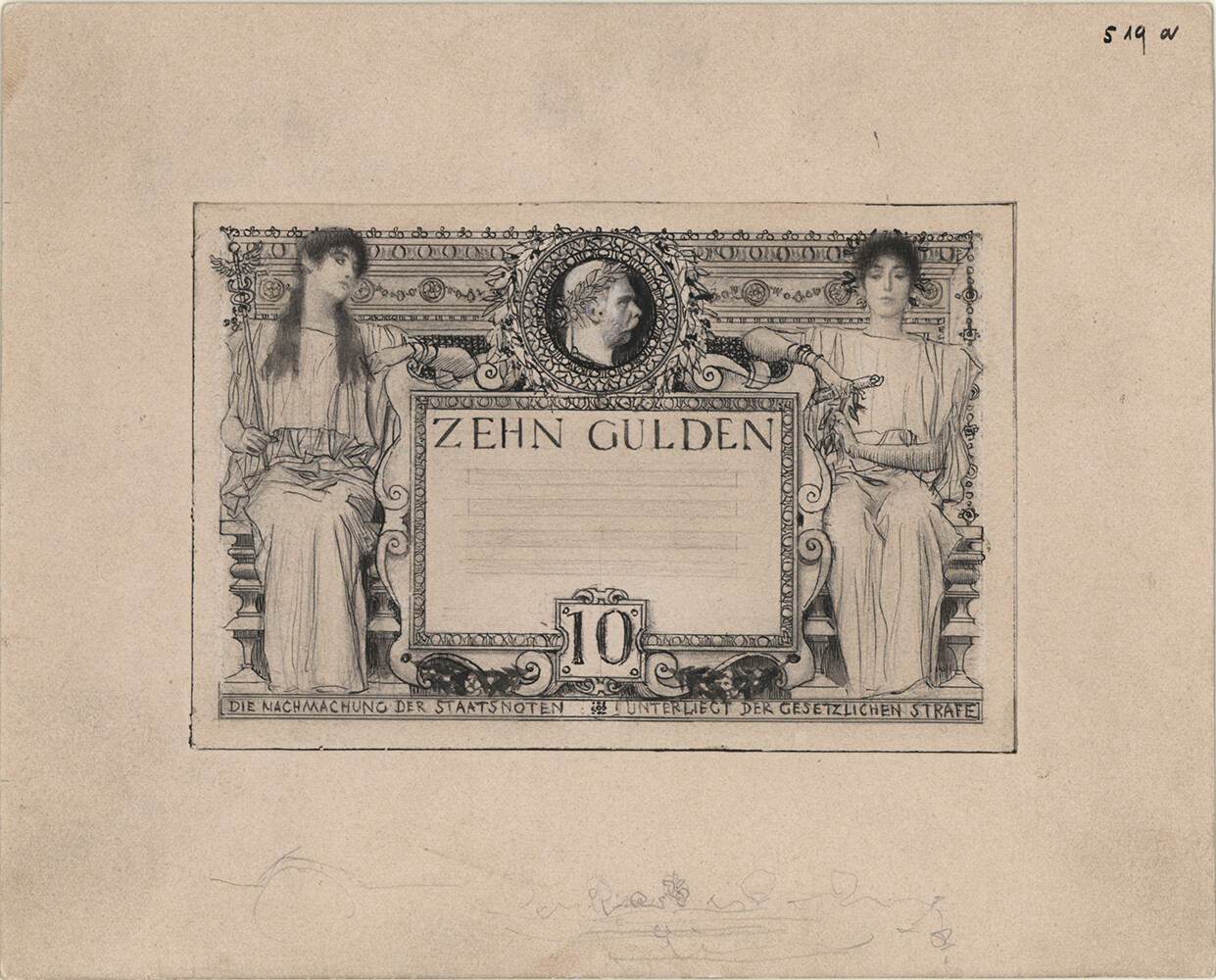

Gustav Klimt: Banknote "Ten guilders" (design), 1892, Österreichische Nationalbank

© Oesterreichische Nationalbank

Decorator of the Ringstraße

Gustav Klimt’s allegories for the staircase of the Imperial-Royal Court Museum of Art History can be considered the acme of his activities as a decorator of Ringstraße buildings. They were also his last successful commission as a decorator of a public building. At this time, Klimt began painting commissioned portraits for the bourgeoisie and became involved in the project of the Faculty Paintings for the University of Vienna.

→

Vienna Volksgarten with the court museums, circa 1890

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Imperial-Royal Court Museum of Art History

Court Museum of Art History, around 1900

© Wien Museum

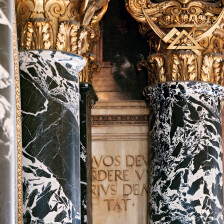

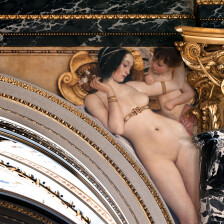

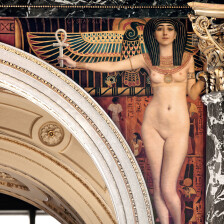

In 1890, the “Künstler-Compagnie” was entrusted with completing the decoration in the staircase of the Court Museum of Art History. The cycle, comprising spandrel and intercolumnar panels, allegorizes major stylistic periods in the visual arts. This decoration project can be considered the acme of Klimt’s work at the threshold between Historicism and the dawn of Art Nouveau or Jugendstil.

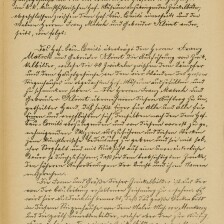

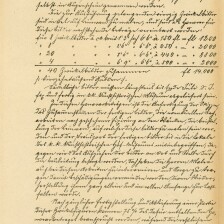

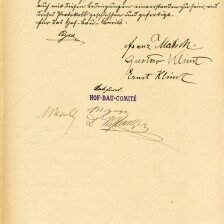

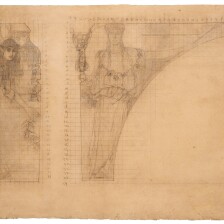

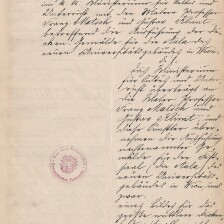

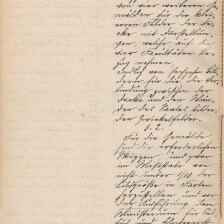

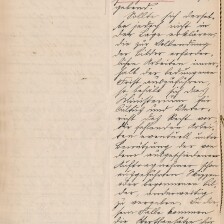

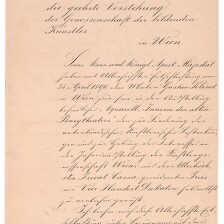

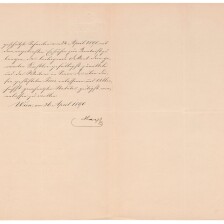

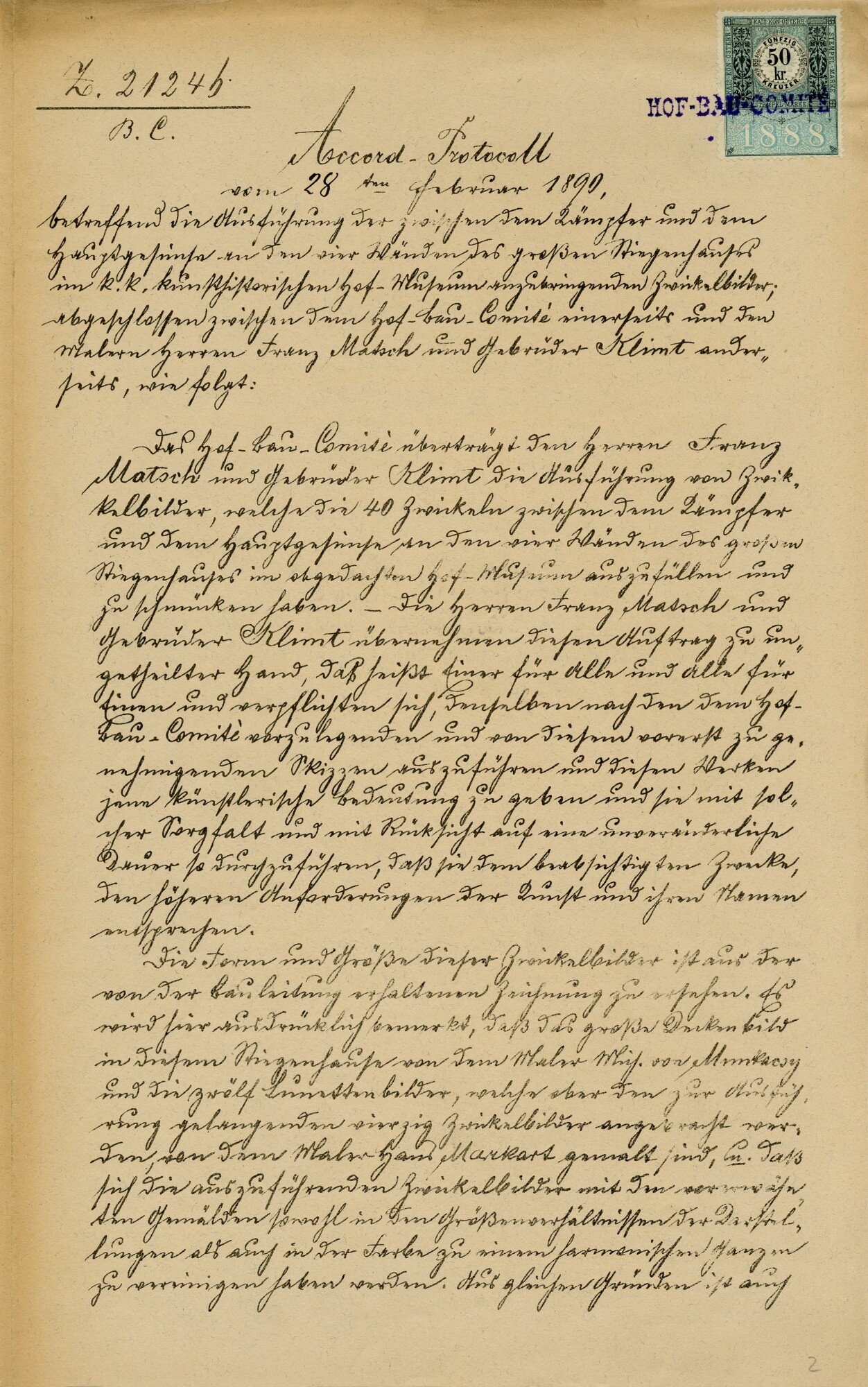

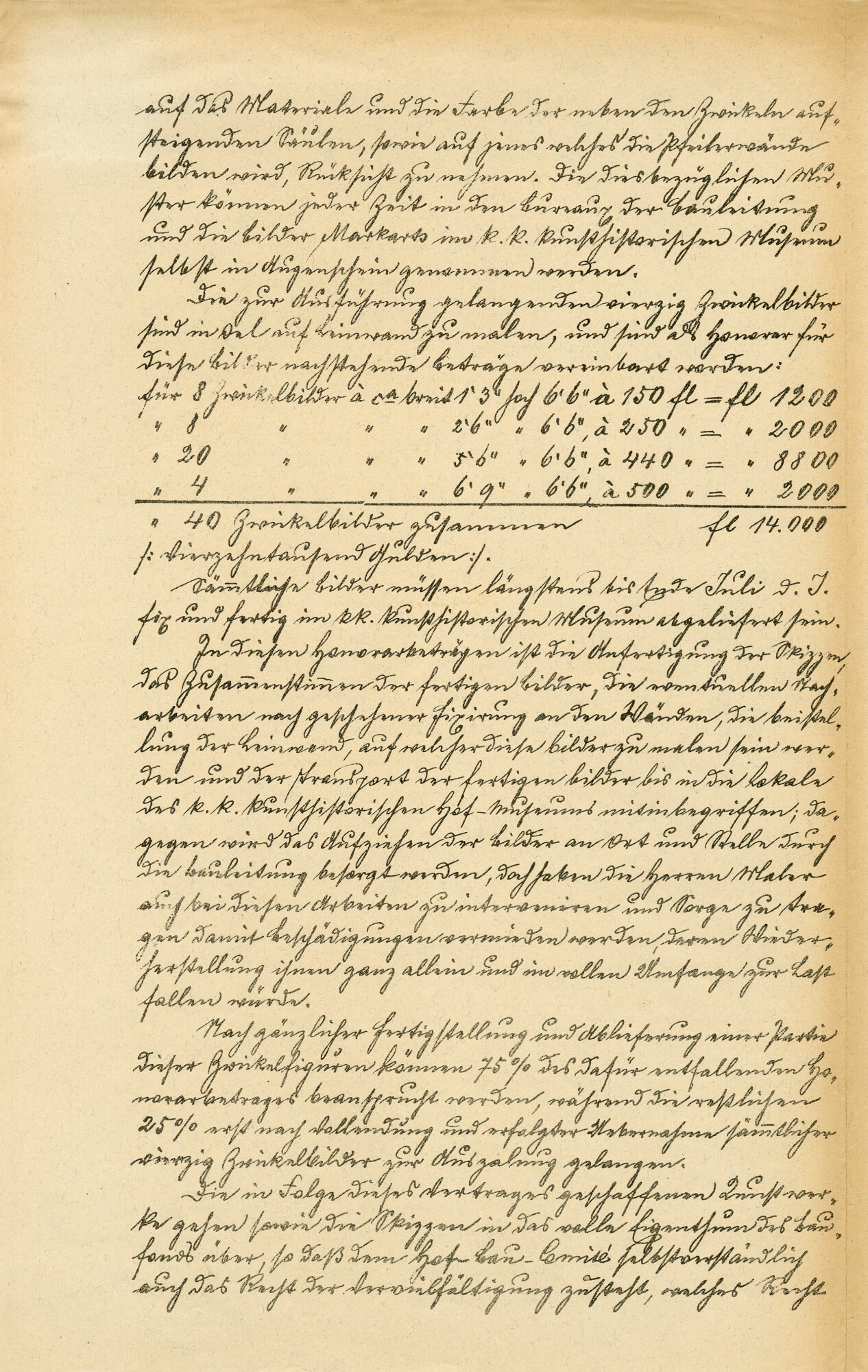

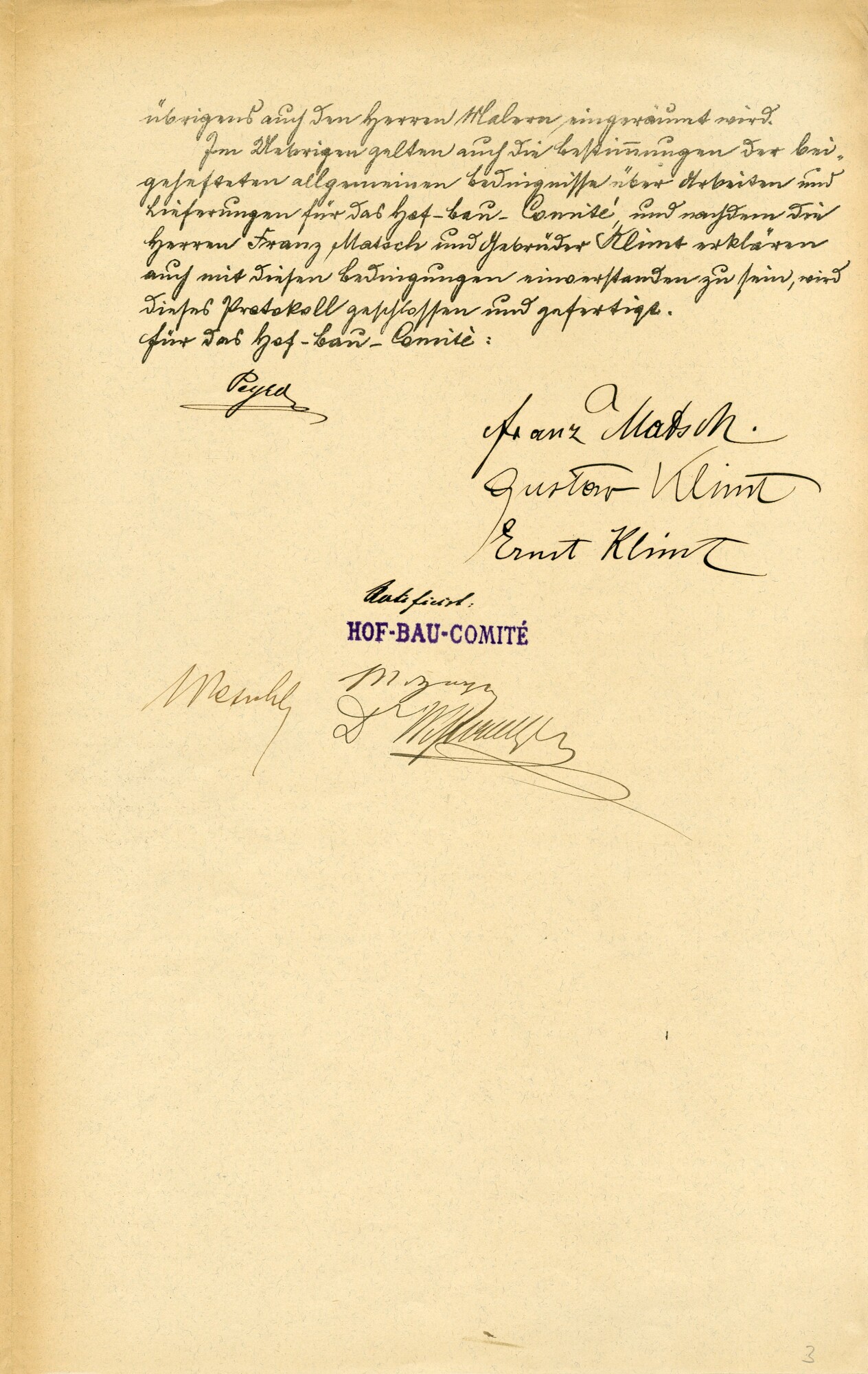

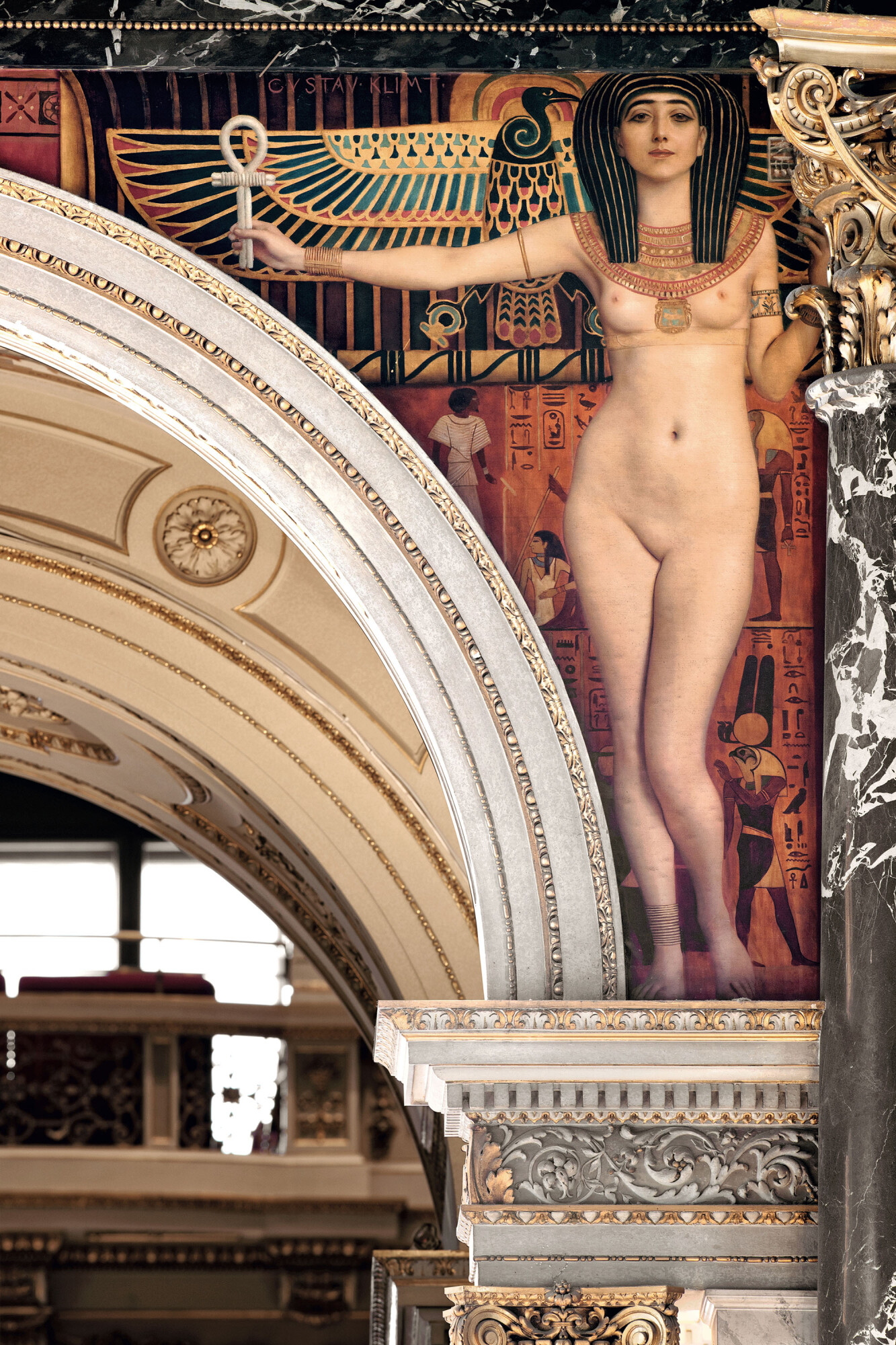

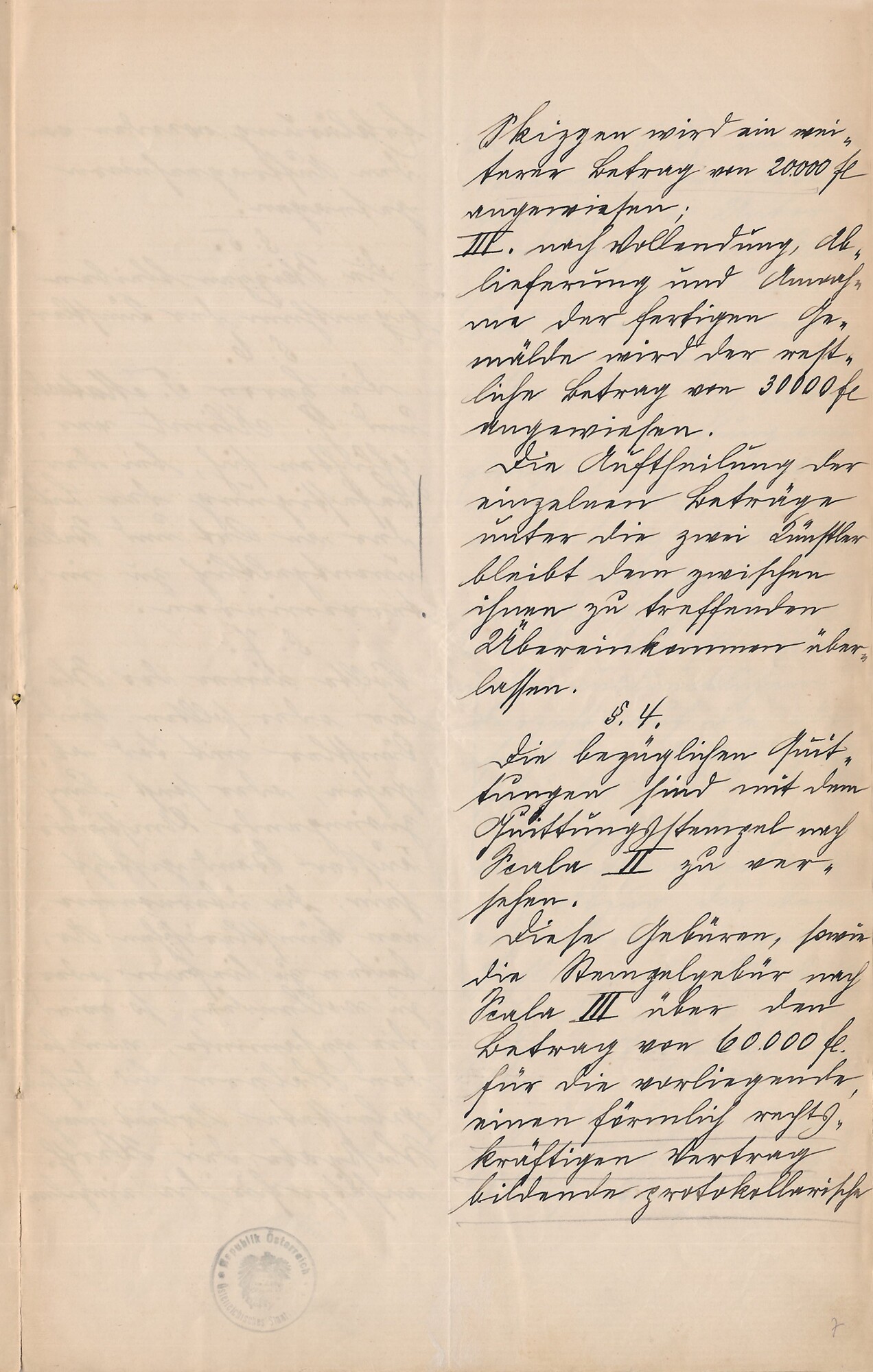

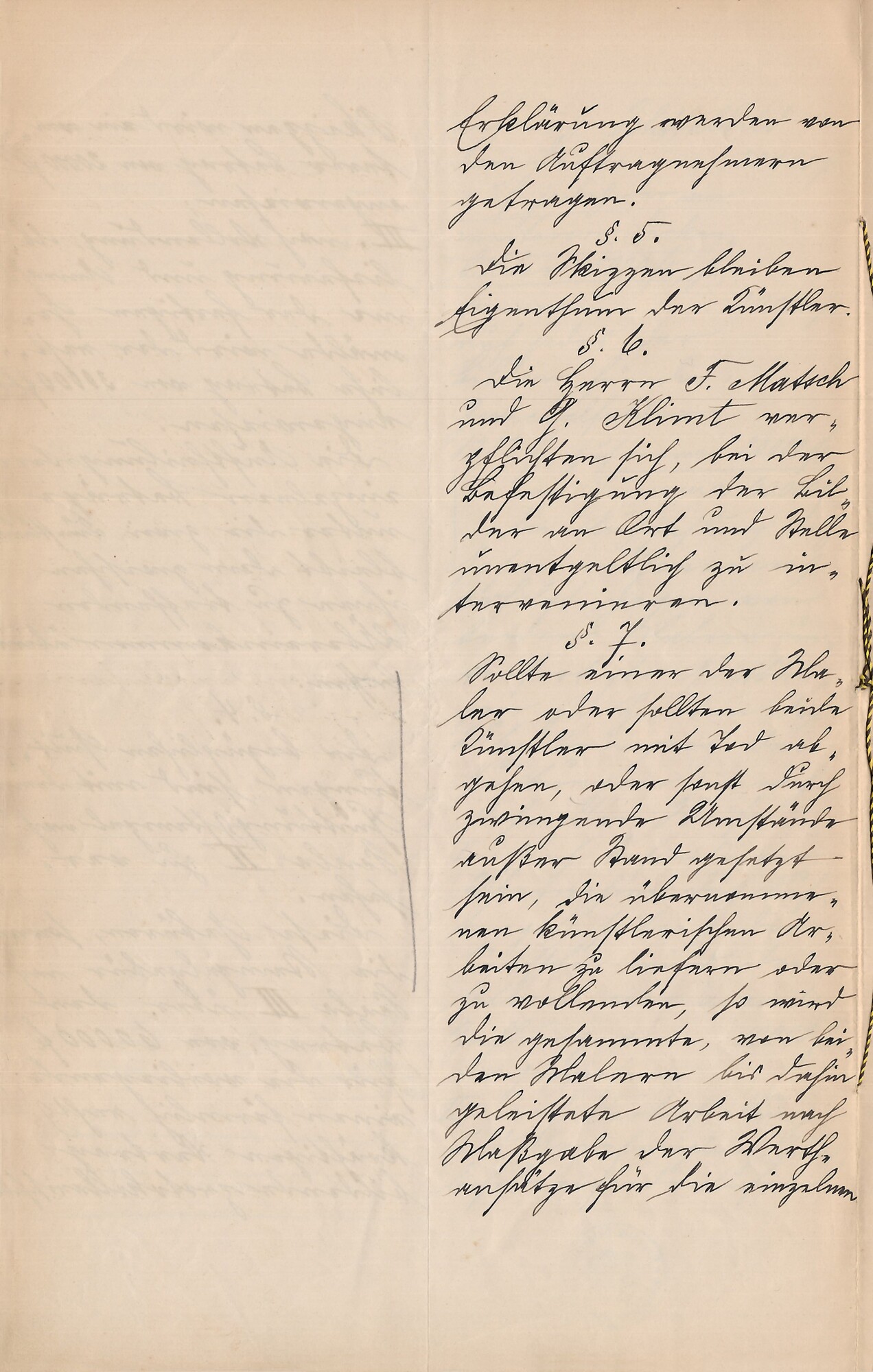

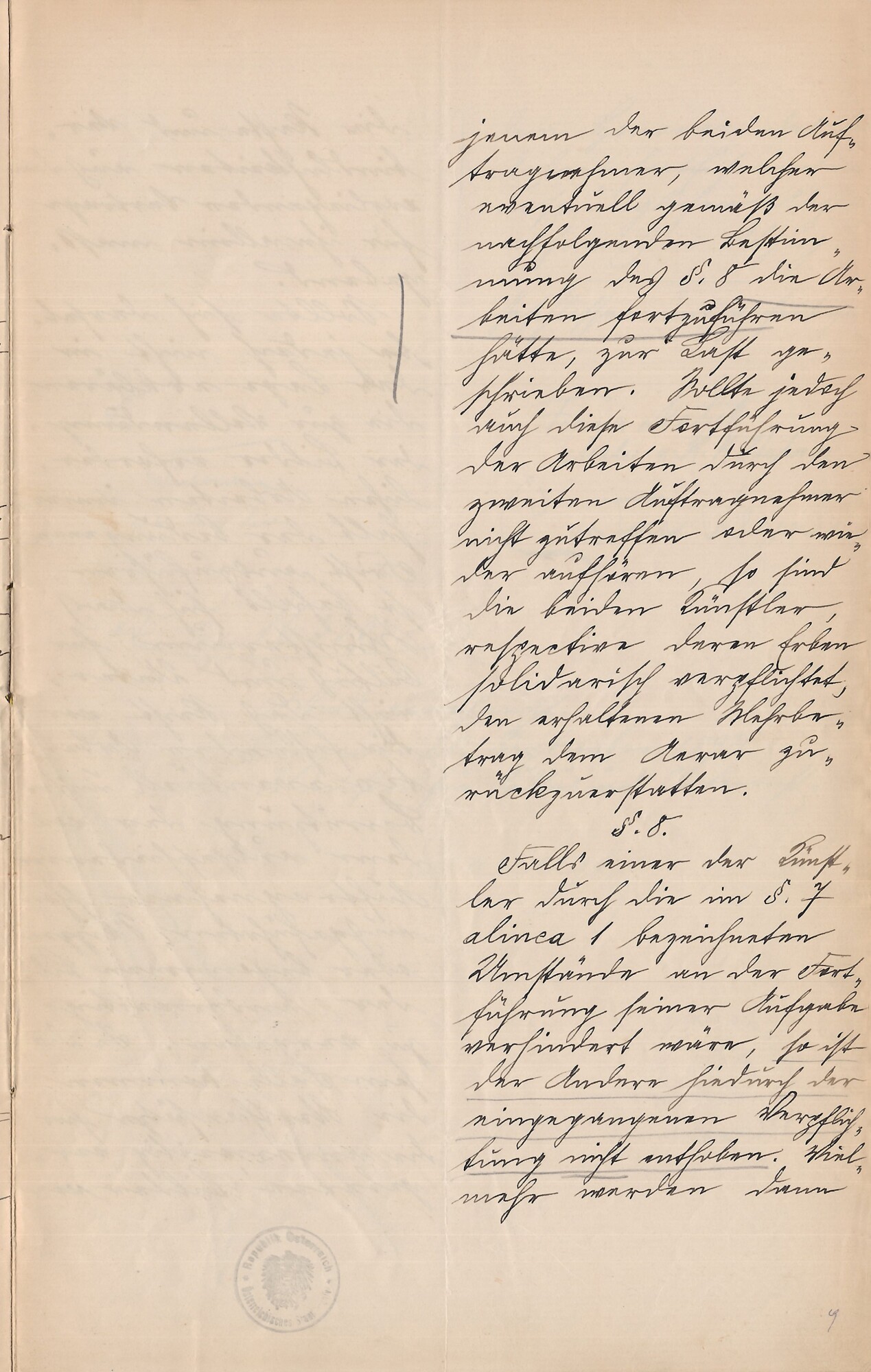

By the time the “Künstler-Compagnie” signed the contract for executing the spandrel and intercolumnar panels in the staircase of the Imperial-Royal Court Museum of Art History (now Kunsthistorisches Museum) on 28 February 1890, its decoration was unfinished except for the lunettes by Hans Makart from 1881. For a fee of 14,000 guilders (approx. 190,352 euros), the promising painters were to conceive 40 representations of the major art epochs, from Egyptian and Greek antiquity to Baroque art. Gustav Klimt was confronted with severe compositional restrictions due to the placement of the pictures in the spandrels above the arcades and in the fields between the columns (intercolumniation). He coped with this challenge by rendering the personifications in strict frontality or profile, adding still lifes of artifacts from cultural and art history.

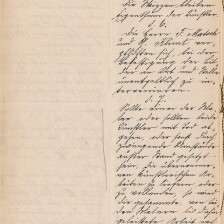

Minutes of the Agreement of 28 February 1890

-

Piecework protocol concerning the decoration of the staircase in the Imperial-Royal Museum of Art History, signed by Franz Matsch, Gustav and Ernst Klimt and members of the Court Building Committee, 02/28/1890, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

Piecework protocol concerning the decoration of the staircase in the Imperial-Royal Museum of Art History, signed by Franz Matsch, Gustav and Ernst Klimt and members of the Court Building Committee, 02/28/1890, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

© Austrian State Archives, Vienna -

Piecework protocol concerning the decoration of the staircase in the Imperial-Royal Museum of Art History, signed by Franz Matsch, Gustav and Ernst Klimt and members of the Court Building Committee, 02/28/1890, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

Piecework protocol concerning the decoration of the staircase in the Imperial-Royal Museum of Art History, signed by Franz Matsch, Gustav and Ernst Klimt and members of the Court Building Committee, 02/28/1890, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

© Austrian State Archives, Vienna -

Piecework protocol concerning the decoration of the staircase in the Imperial-Royal Museum of Art History, signed by Franz Matsch, Gustav and Ernst Klimt and members of the Court Building Committee, 02/28/1890, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

Piecework protocol concerning the decoration of the staircase in the Imperial-Royal Museum of Art History, signed by Franz Matsch, Gustav and Ernst Klimt and members of the Court Building Committee, 02/28/1890, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

© Austrian State Archives, Vienna

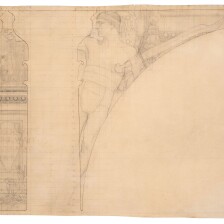

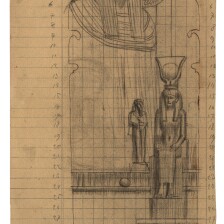

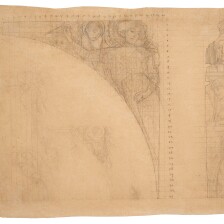

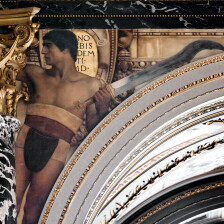

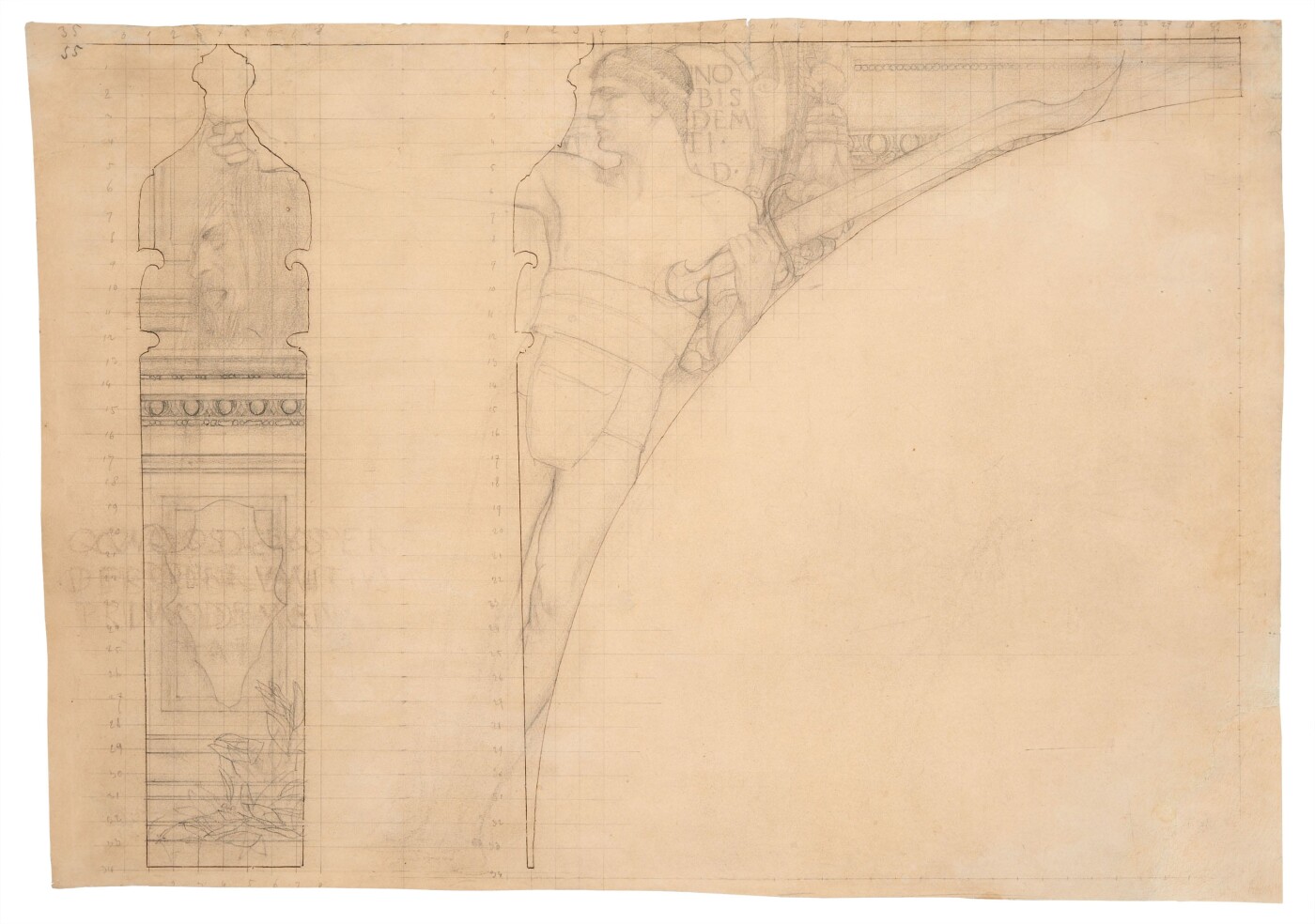

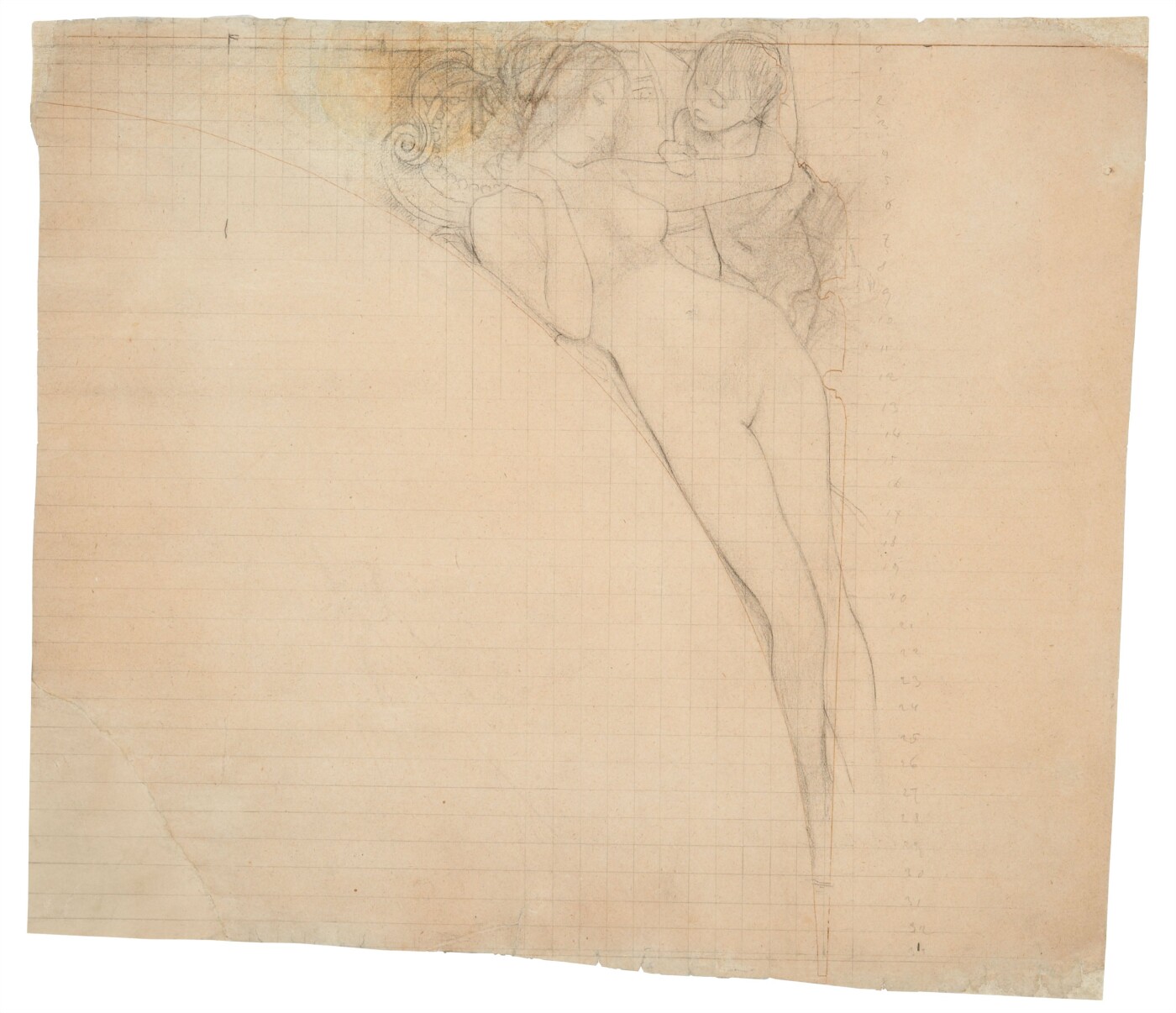

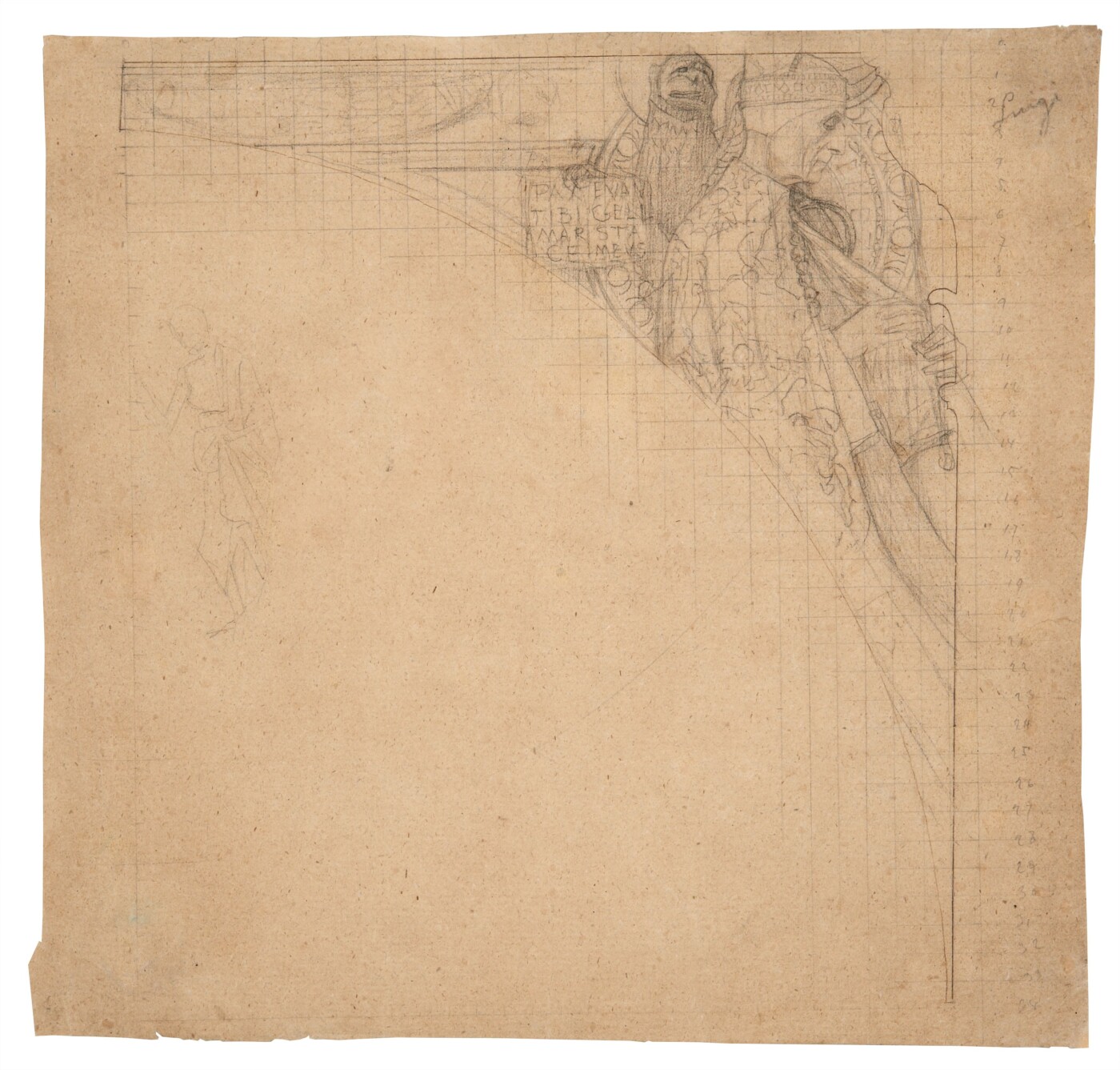

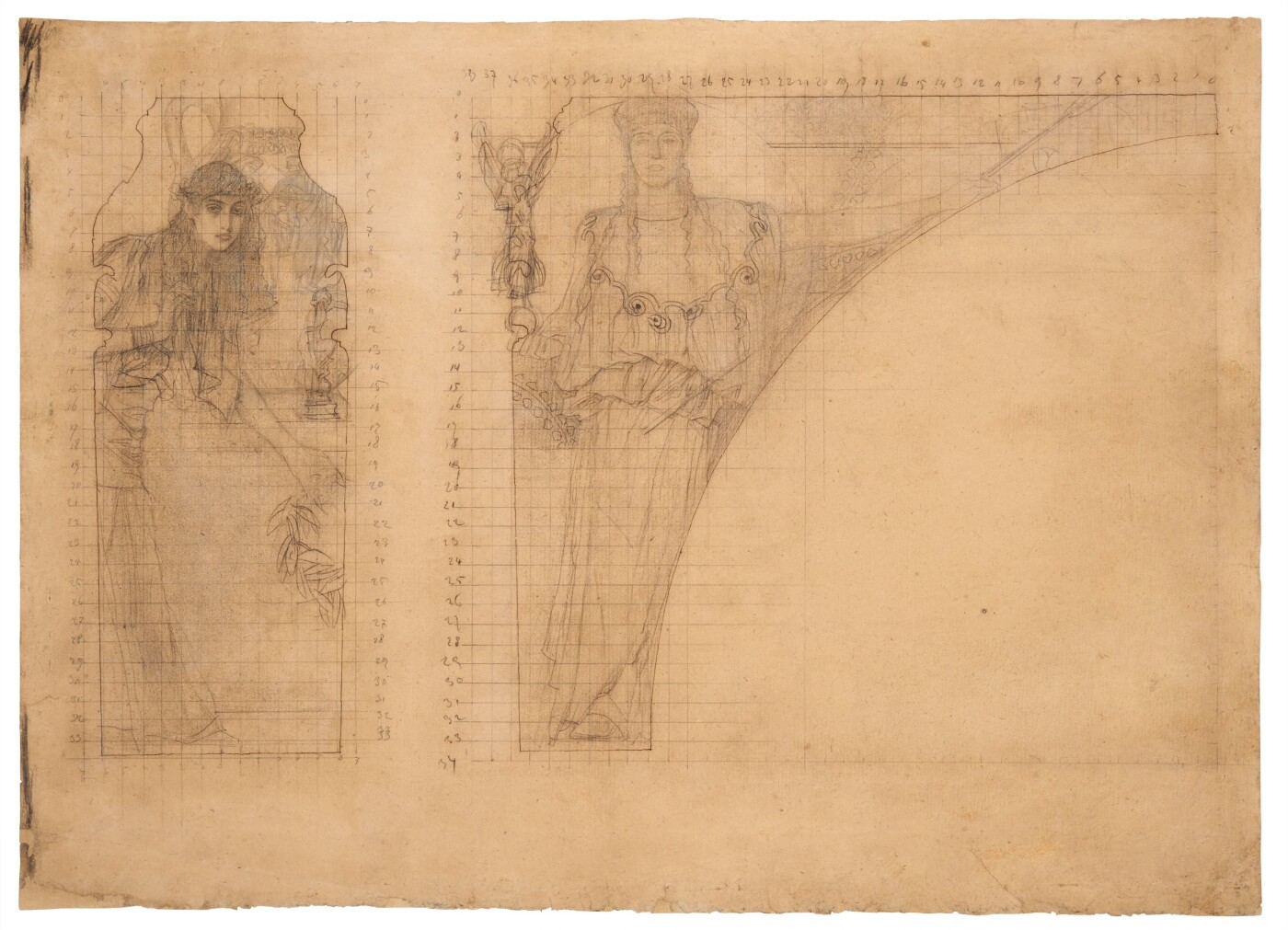

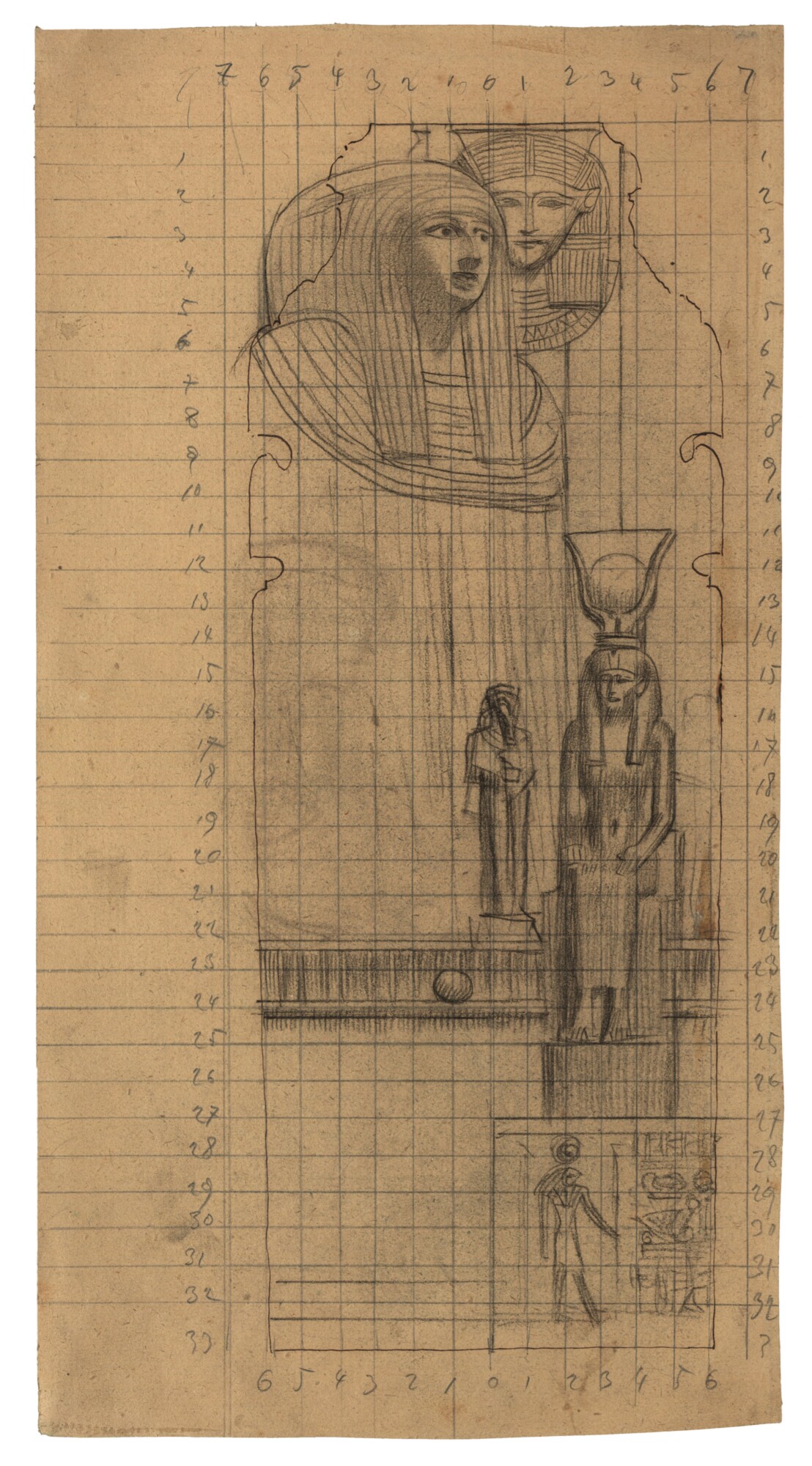

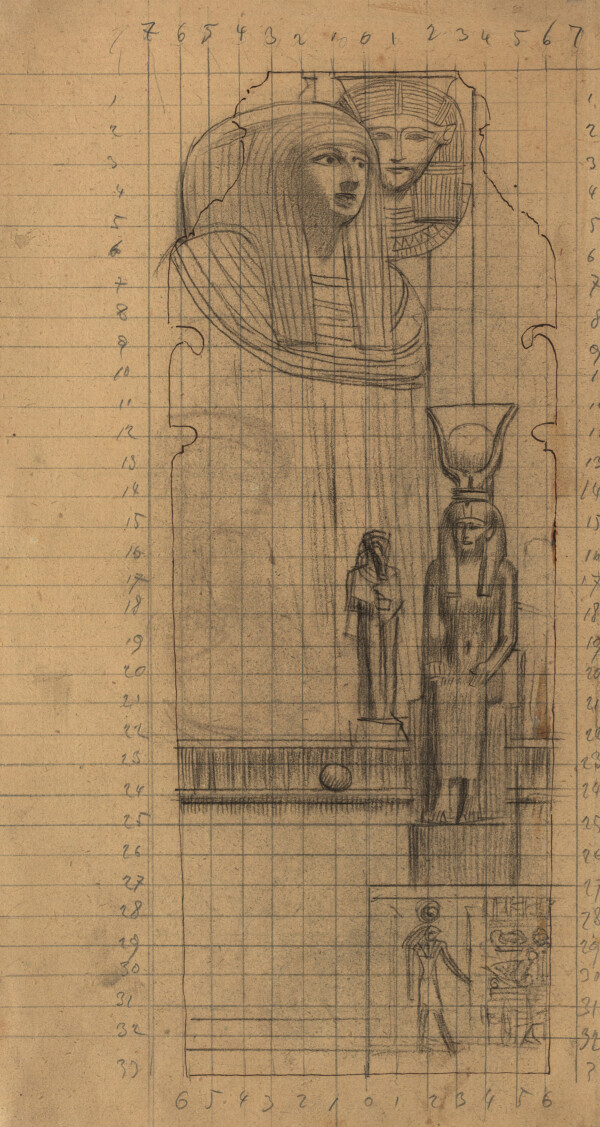

Gustav Klimt was in charge of the decoration of the entire north wall and the first arch of the adjacent west wall. He conceived allegories of Greek and Egyptian antiquity and of the Italian Renaissance. The latter was divided into schools (Roman, Venetian, Florentine) and represented both the 15th and the early 16th century. For the Florentine Cinquecento (Head of Goliath), Klimt vaguely harked back to Michelangelo’s famous David (1501–1504, Galleria dell’Academia, Florence), and for his Venus he drew upon Sandro Botticelli’s Goddess of Love. On the north wall, the allegories of the Roman and Venetian Renaissance show attributes of Ecclesia (Papal Church) and the Doge. Klimt positioned the most impressive allegories at the center of the wall: Greek and Egyptian antiquity, embodied by the deities of Pallas Athena and Nekhbet. Finally, there follows the Early Renaissance with a Scholar in Renaissance Costume and Saint with Cherubim. It is interesting that for these figures Klimt harked back to a painting in the picture gallery at the Academy of Fine Arts instead of making reference to a work in the imperial collections (now Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna).

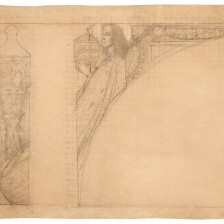

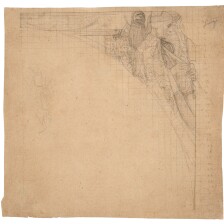

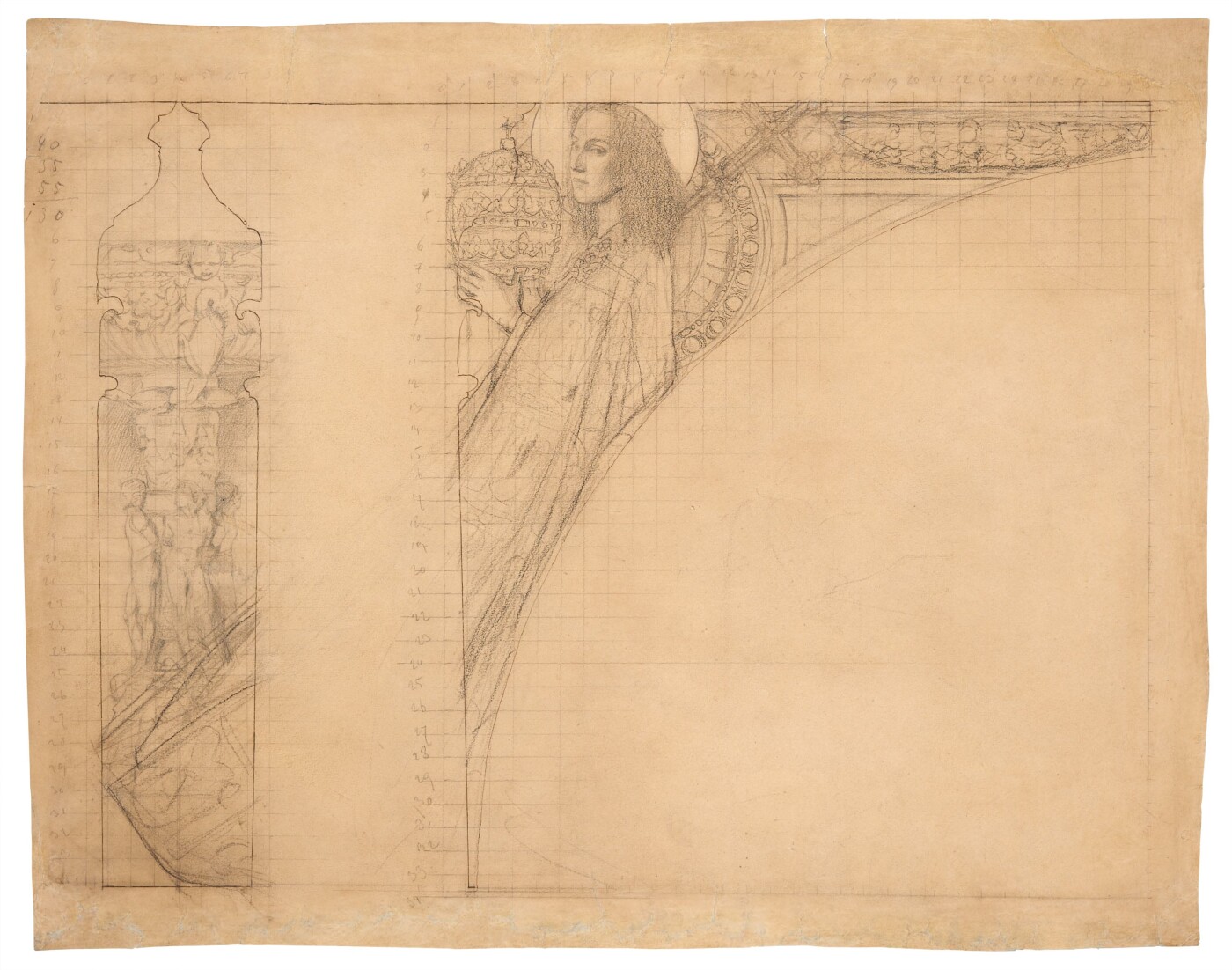

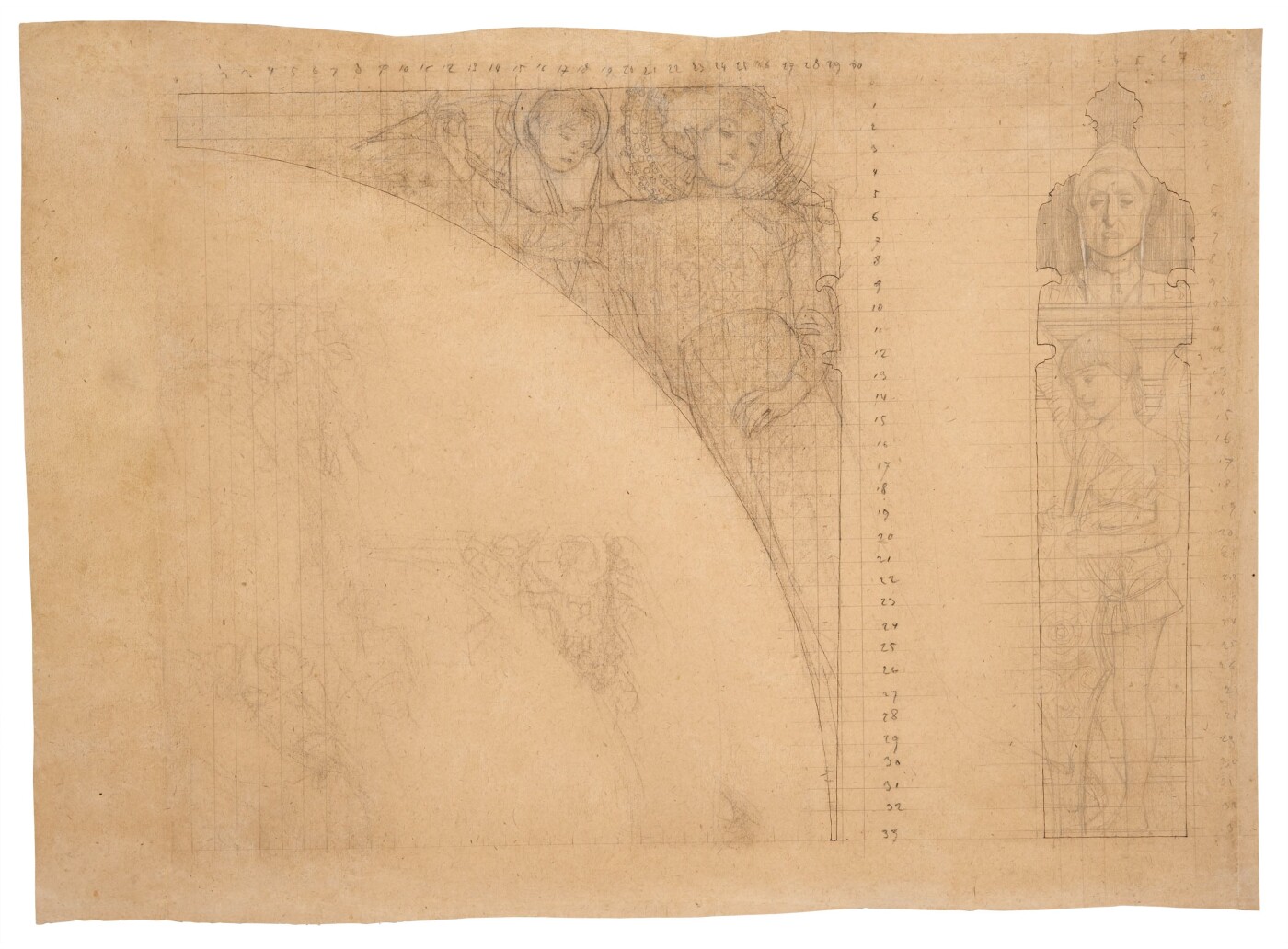

Transfer Sketches for the Spandrel and Intercolumnar Panels by Gustav Klimt

-

Gustav Klimt: The Florentine Cinquecento (transfer sketch), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Bibliothek

Gustav Klimt: The Florentine Cinquecento (transfer sketch), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Bibliothek

© KHM-Museumsverband -

Gustav Klimt: The Florentine Quattrocento (transfer sketch), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Bibliothek

Gustav Klimt: The Florentine Quattrocento (transfer sketch), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Bibliothek

© KHM-Museumsverband -

Gustav Klimt: The Roman Quattrocento (transfer sketch), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Bibliothek

Gustav Klimt: The Roman Quattrocento (transfer sketch), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Bibliothek

© KHM-Museumsverband -

Gustav Klimt: The Venetian Quattrocento (transfer sketch), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Bibliothek

Gustav Klimt: The Venetian Quattrocento (transfer sketch), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Bibliothek

© KHM-Museumsverband -

Gustav Klimt: Ancient Greece (transfer sketch), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Bibliothek

Gustav Klimt: Ancient Greece (transfer sketch), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Bibliothek

© KHM-Museumsverband -

Gustav Klimt: Egyptian art (transfer sketch), 1890/91, Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Egyptian art (transfer sketch), 1890/91, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum -

Gustav Klimt: Ancient Italian art (transfer sketch), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Bibliothek

Gustav Klimt: Ancient Italian art (transfer sketch), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Bibliothek

© KHM-Museumsverband

North wall in the staircase of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

© KHM-Museumsverband

Spandrel and Intercolumnar Panels by Gustav Klimt in the Staircase of the Kunsthistorisches Museum

-

Gustav Klimt: The Florentine Cinquecento (Head of Goliath), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

Gustav Klimt: The Florentine Cinquecento (Head of Goliath), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

© KHM-Museumsverband -

Gustav Klimt: The Florentine Cinquecento (David), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

Gustav Klimt: The Florentine Cinquecento (David), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

© KHM-Museumsverband -

Gustav Klimt: The Florentine Quattrocento (Venus), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

Gustav Klimt: The Florentine Quattrocento (Venus), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

© KHM-Museumsverband -

Gustav Klimt: The Roman Quattrocento (Baptismal Font), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

Gustav Klimt: The Roman Quattrocento (Baptismal Font), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

© KHM-Museumsverband -

Gustav Klimt: The Roman Quattrocento (Ecclesia), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

Gustav Klimt: The Roman Quattrocento (Ecclesia), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

© KHM-Museumsverband -

Gustav Klimt: The Venetian Quattrocento (Doge), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

Gustav Klimt: The Venetian Quattrocento (Doge), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

© KHM-Museumsverband -

Gustav Klimt: Greek Antiquity (Girl from Tanagra), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

Gustav Klimt: Greek Antiquity (Girl from Tanagra), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

© KHM-Museumsverband -

Gustav Klimt: Greek Antiquity (Athena), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

Gustav Klimt: Greek Antiquity (Athena), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

© KHM-Museumsverband -

Gustav Klimt: Egyptian Art (Nekhbet), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

Gustav Klimt: Egyptian Art (Nekhbet), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

© KHM-Museumsverband -

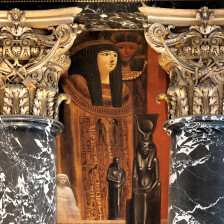

Gustav Klimt: Egyptian Art (Sarcophagus and Isis Statuette), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

Gustav Klimt: Egyptian Art (Sarcophagus and Isis Statuette), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

© KHM-Museumsverband -

Gustav Klimt: Old Italian Art (Scholar in Renaissance Costume), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

Gustav Klimt: Old Italian Art (Scholar in Renaissance Costume), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

© KHM-Museumsverband -

Gustav Klimt: Ancient Italian art (saints with cherubs), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

Gustav Klimt: Ancient Italian art (saints with cherubs), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

© KHM-Museumsverband -

Gustav Klimt: Ancient Italian art (angel with bust of Dante), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

Gustav Klimt: Ancient Italian art (angel with bust of Dante), 1890/91, Kunsthistorisches Museum

© KHM-Museumsverband

Albert Ilg: Zwickelbilder im Stiegenhaus des k. k. Kunsthistorischen Hof-Museums zu Wien, Vienna 1893.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

In no time at all, Gustav Klimt managed to compile convincing compositions for the major art epochs from illustrations in various books. Although it would have been possible to use masterpieces from the imperial collections as pictorial sources, Klimt did without them. There is no evidence whether this was due to the custodians’ wish. Albert Ilg, the director of the Collection of Arms and Armor and the Chamber of Curiosity (Kunstkammer), accompanied the project with a specially dedicated publication, yet without commenting upon this point.

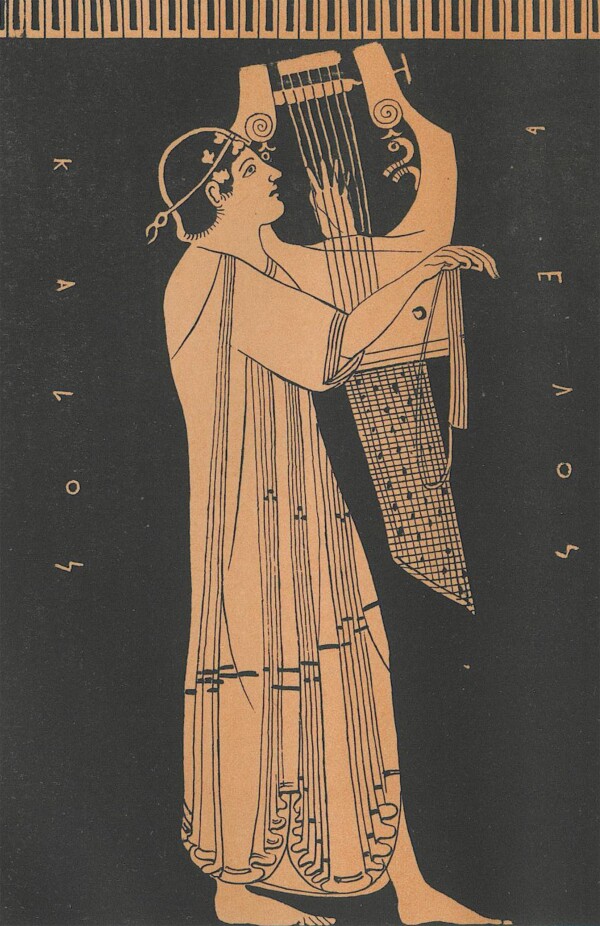

Iconographically, the allegories blend in seamlessly with Klimt’s work, as they particularly betray similarities with his designs for Homage to Archduke Rainer (1889, Albertina, Vienna) and Sculpture (1896, Wien Museum, Vienna) for Martin Gerlach’s Allegorien. Neue Folge [“Allegories. New Series”] (1895/96). As to Gustav Klimt’s stylistic development, the depiction of Nekhbet likewise oscillates between these two female nudes. In the decades to come, the Viennese painter would intensively deal with the flatness and linearity borrowed from Greek vase painting: in the so-called Golden Period, Klimt sought to repress the volumes of the figures while emphasizing the beauty of the line.

Klimt thus joined forced with the country’s most renowned artists, which opened a crucial network of art-loving patrons and collectors for Gustav Klimt, including Nicolaus Dumba.

Literature and sources

- Albert Ilg: Zwickelbilder im Stiegenhaus des k. k. Kunsthistorischen Hof-Museums zu Wien, Vienna 1893.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012.

- Sabine Haag (Hg.): Gustav Klimt im Kunsthistorischen Museum, Ausst.-Kat., Museum of Art History (Vienna), 14.02.2012–06.05.2012, Vienna 2012.

- Beatrix Kriller: Gustav Klimt im Kunsthistorischen Museum. Die Entstehung der Zwickel- und Interkolumnienbilder im großen Stiegenhaus, 1890–1891, in: Toni Stoos, Christoph Doswald (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Ausst.-Kat., Kunsthaus Zurich (Zurich), 11.09.1992–13.12.1992, Stuttgart 1992, S. 216-229.

- Ernst Czerny: Gustav Klimt und die ägyptische Kunst. Die Stiegenhausbilder im Kunsthistorischen Museum in Wien und ihre Vorlagen, in: Österreichische Zeitschrift für Kunst und Denkmalpflege 2009, Heft 3/4 (2009).

Faculty Paintings. Awarding of the Commission

University of Vienna Photographed by Josef Wlha, around 1885

© Wien Museum

In September 1894, Franz Matsch and Gustav Klimt received the commission to execute the decorative paintings for the large ceremonial hall of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna. The two artists were to complete their work within four years for a fee of 60,000 guilders.

Programmatic Concept

The awarding of the commission to Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch was preceded by a two-year discussion about demands and concepts. The university building on the Ringstraße had been designed in the style of Italian High Renaissance by Heinrich von Ferstel, and erected between 1873 and 1884. For financial reasons, the building’s decorations – especially for the ceiling of the large ceremonial hall – had to be delayed until the early 1890s. At the time the project was resumed in the spring of 1891, Franz Matsch and Gustav Klimt were just celebrating their artistic breakthrough with their decorations for the Imperial-Royal Hofburgtheater (now Burgtheater, Vienna) and the Imperial-Royal Court Museum of Art History (now Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna). That Klimt was the first laureate of the “Kaiserpreis” [Emperor’s Prize], and that Matsch had been appointed professor at the Imperial-Royal School of Arts and Crafts of the Austrian Museum of Art and Industry in June 1893, also worked in the artists’ favor. The industrialist Nicolaus Dumba commissioned Klimt and Matsch to decorate his residence on Parkring around the same time.

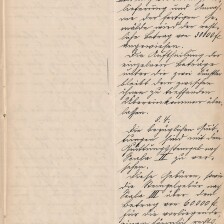

Franz Matsch elaborated a first programmatic concept and two color sketches in 1893, but neither were accepted by those in charge: Both the artistic committee of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna and the Imperial-Royal Ministry of Culture and Education rejected Matsch’s complex design in November 1893. Following thorough consultations, all involved settled on a new draft for the central painting The Triumph of Light over Darkness. The new sketches Matsch submitted on 21 June 1894 were deemed to be “very good,” which meant that the path was now clear for the commission to be officially awarded to Klimt and Matsch.

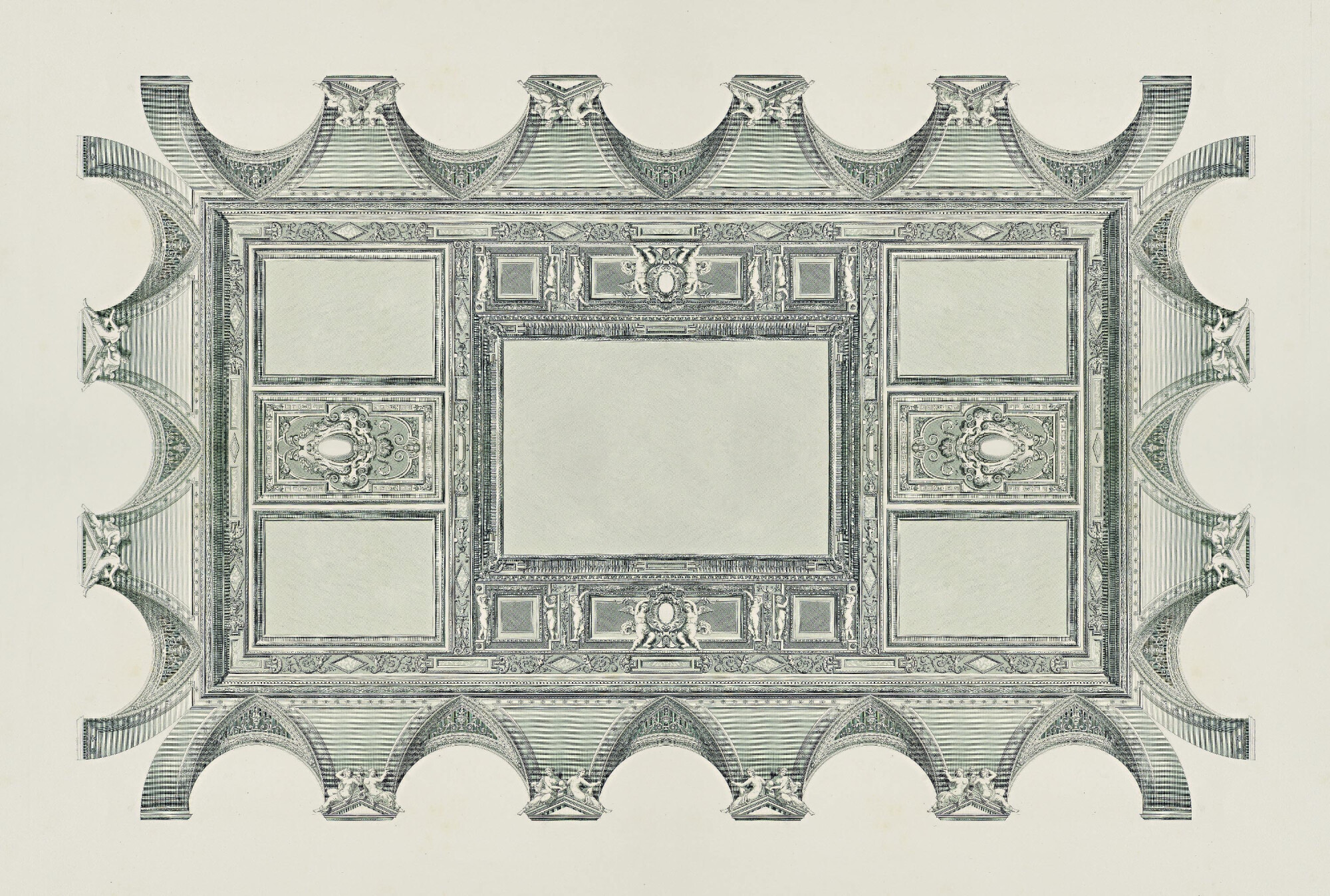

Reconstruction of the ceiling concept for the auditorium of the University of Vienna

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

-

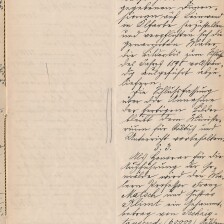

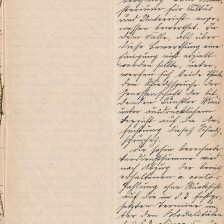

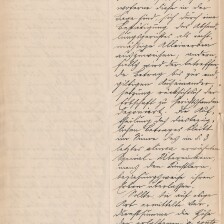

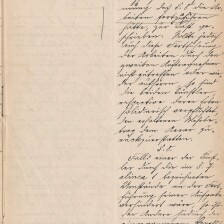

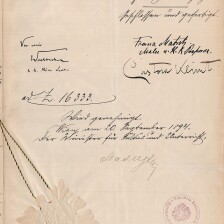

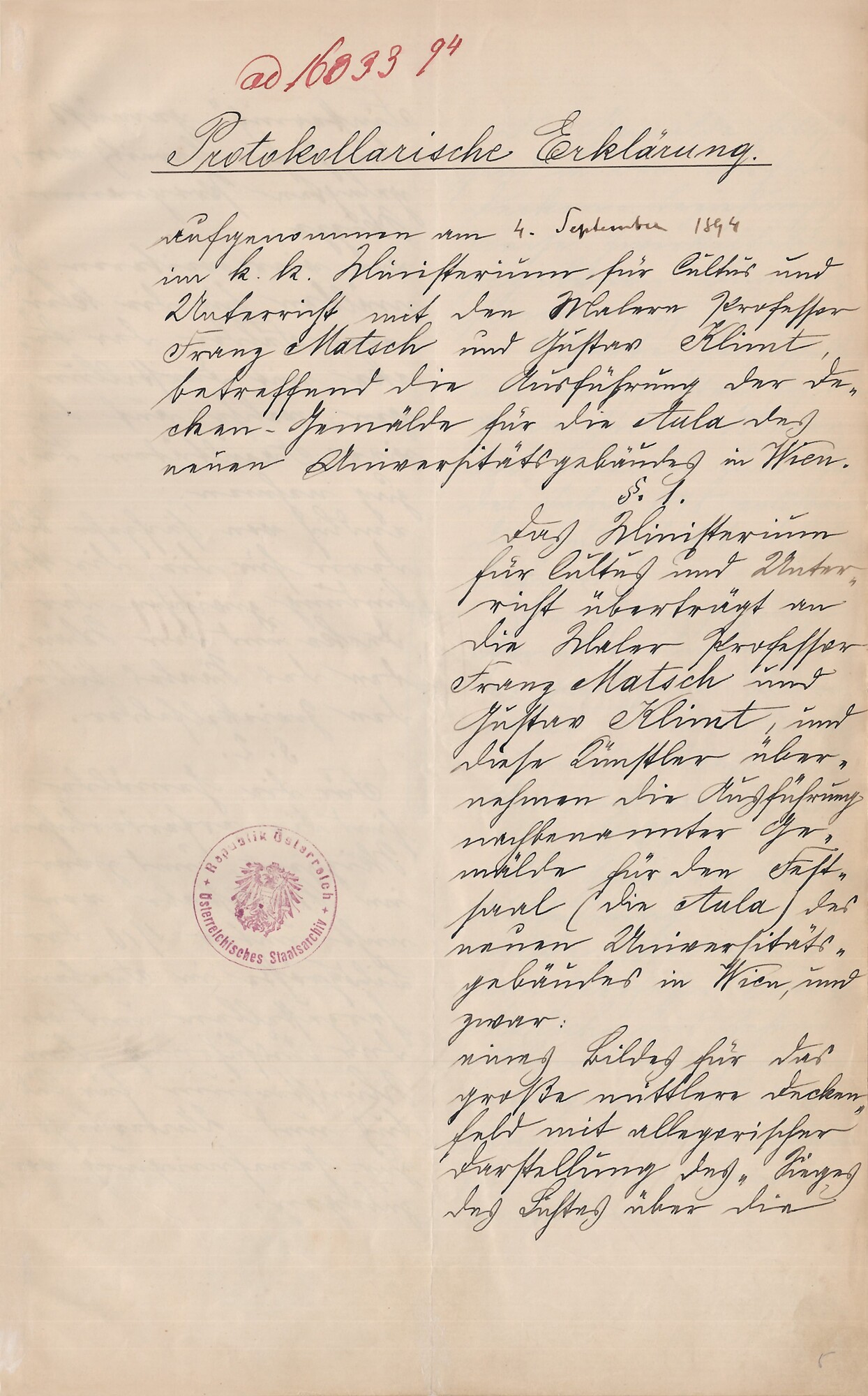

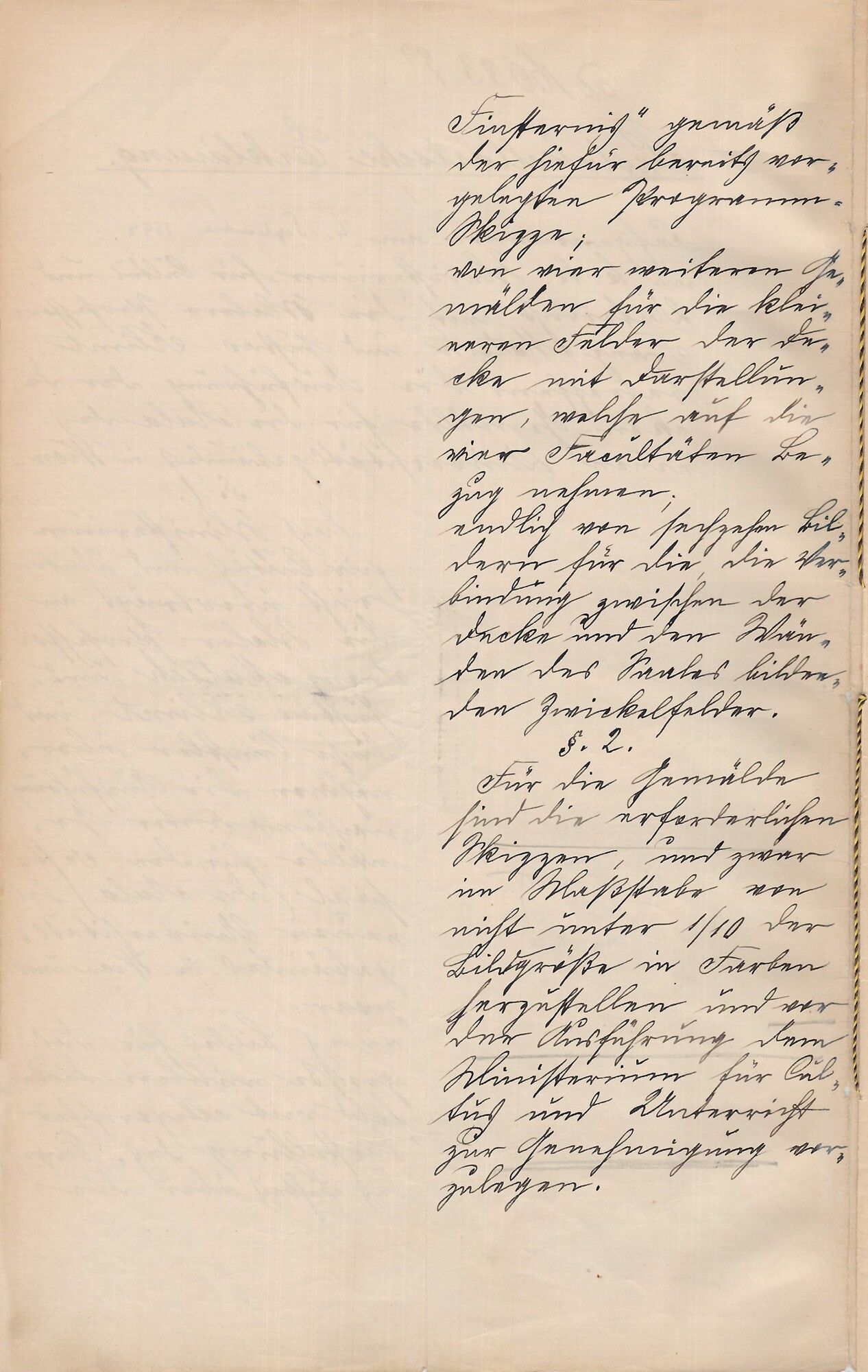

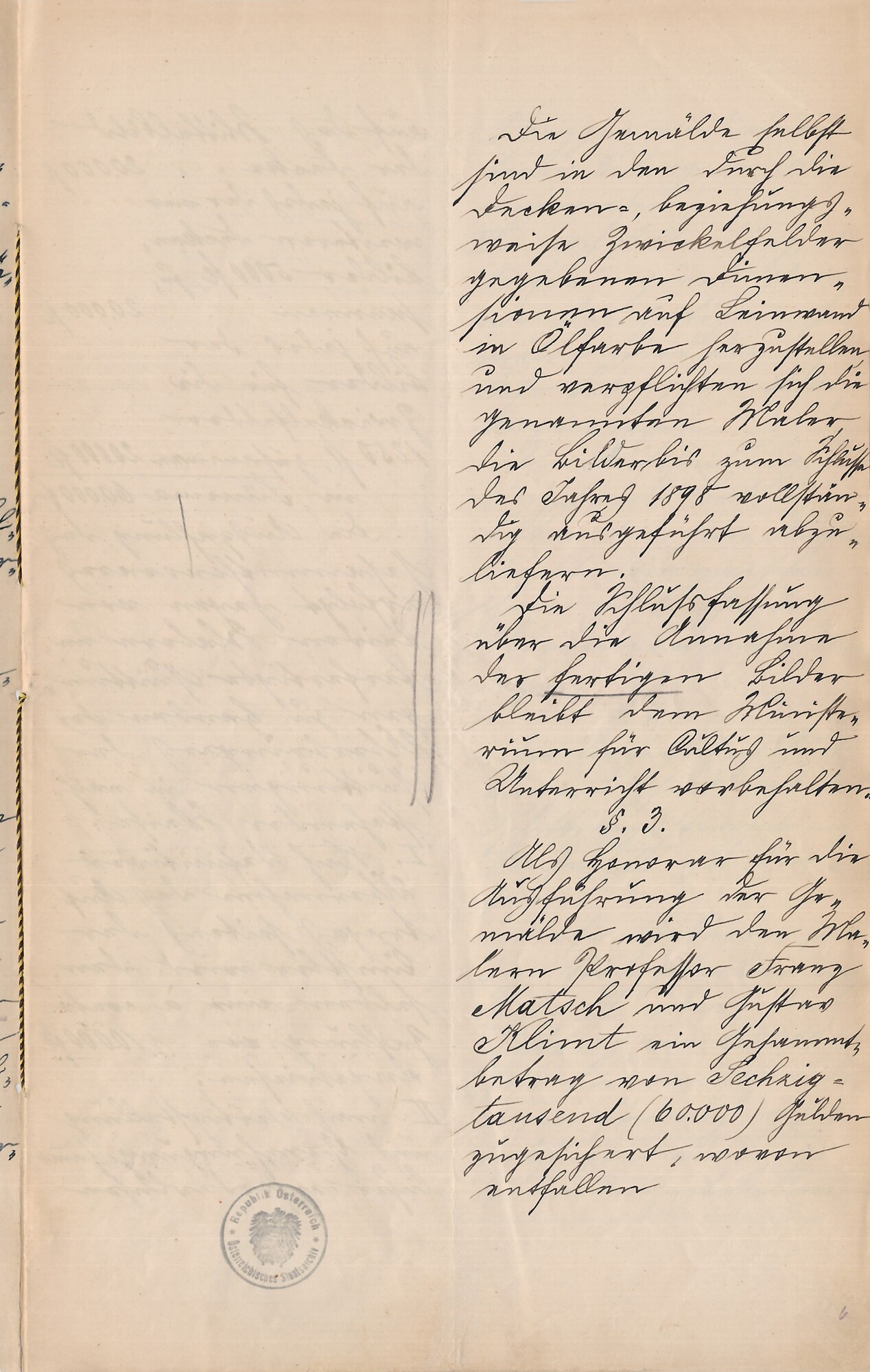

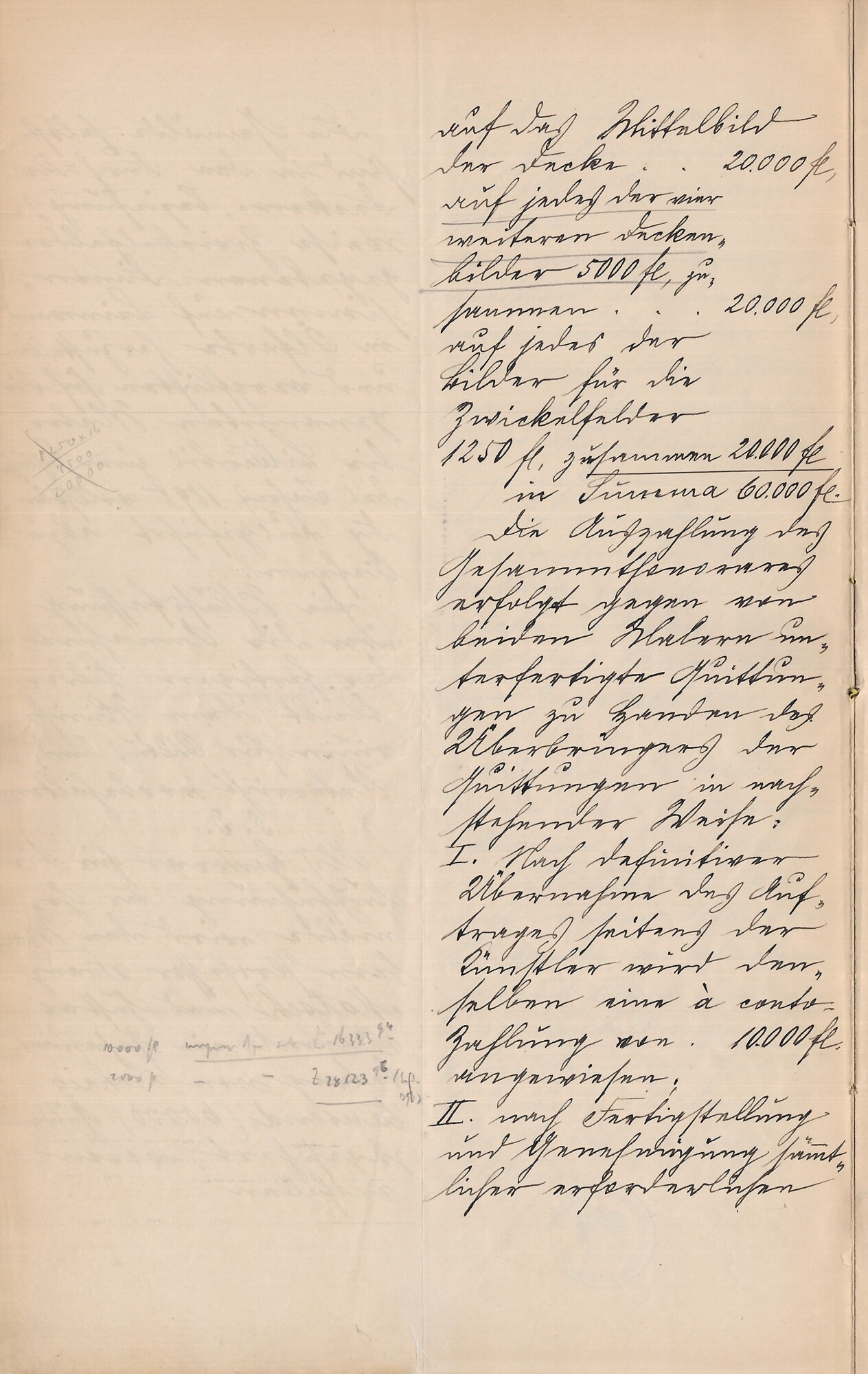

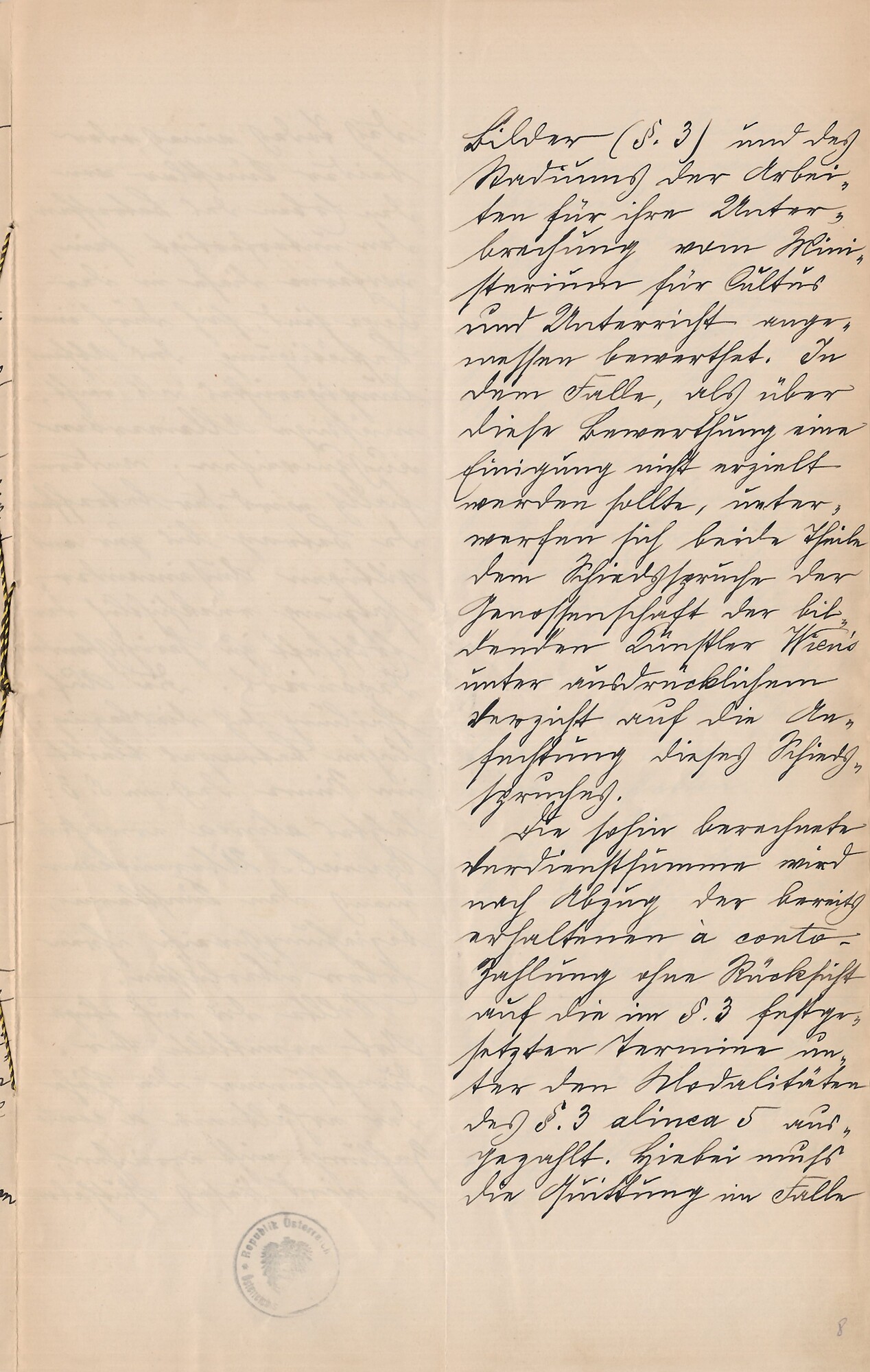

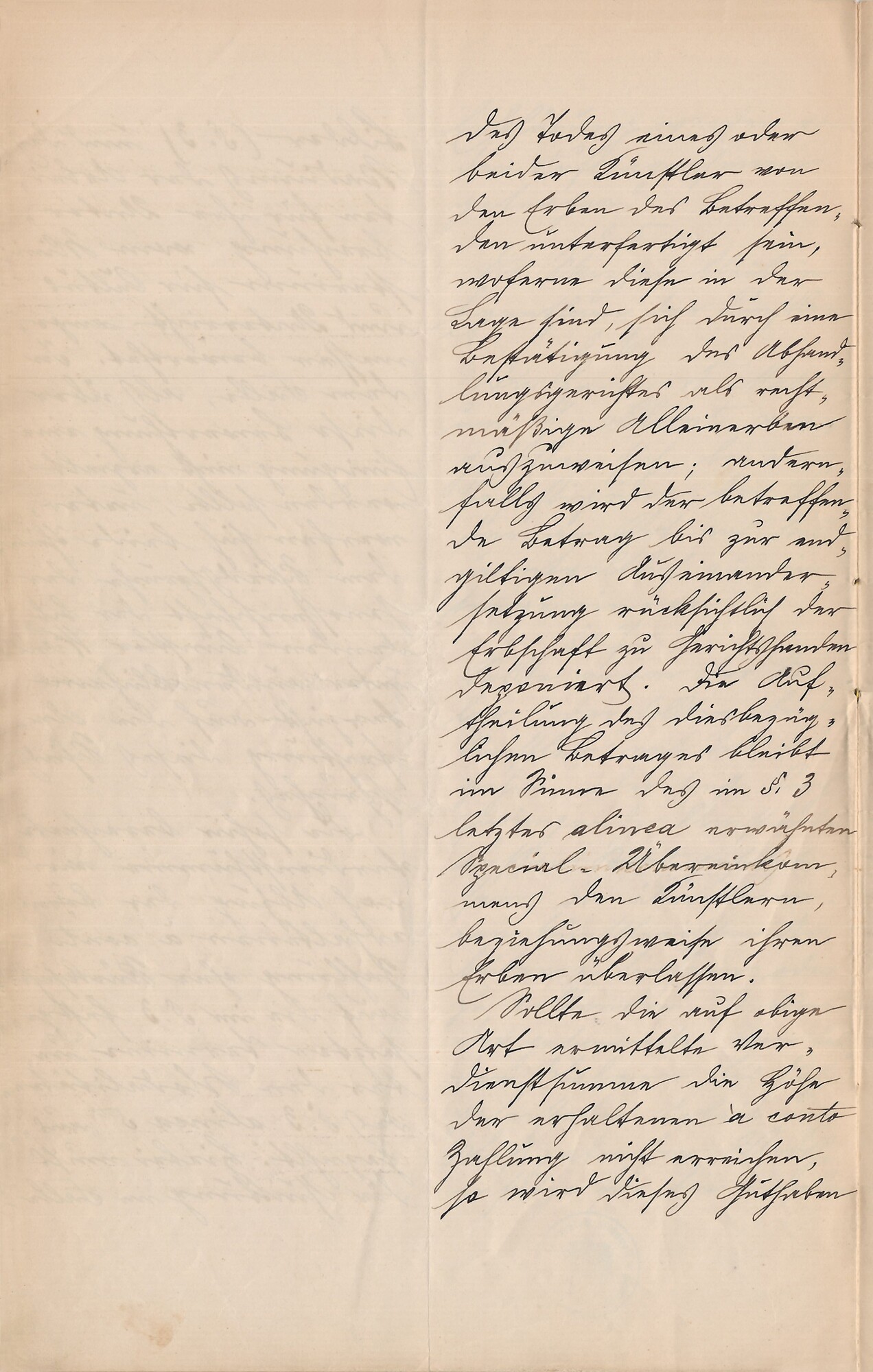

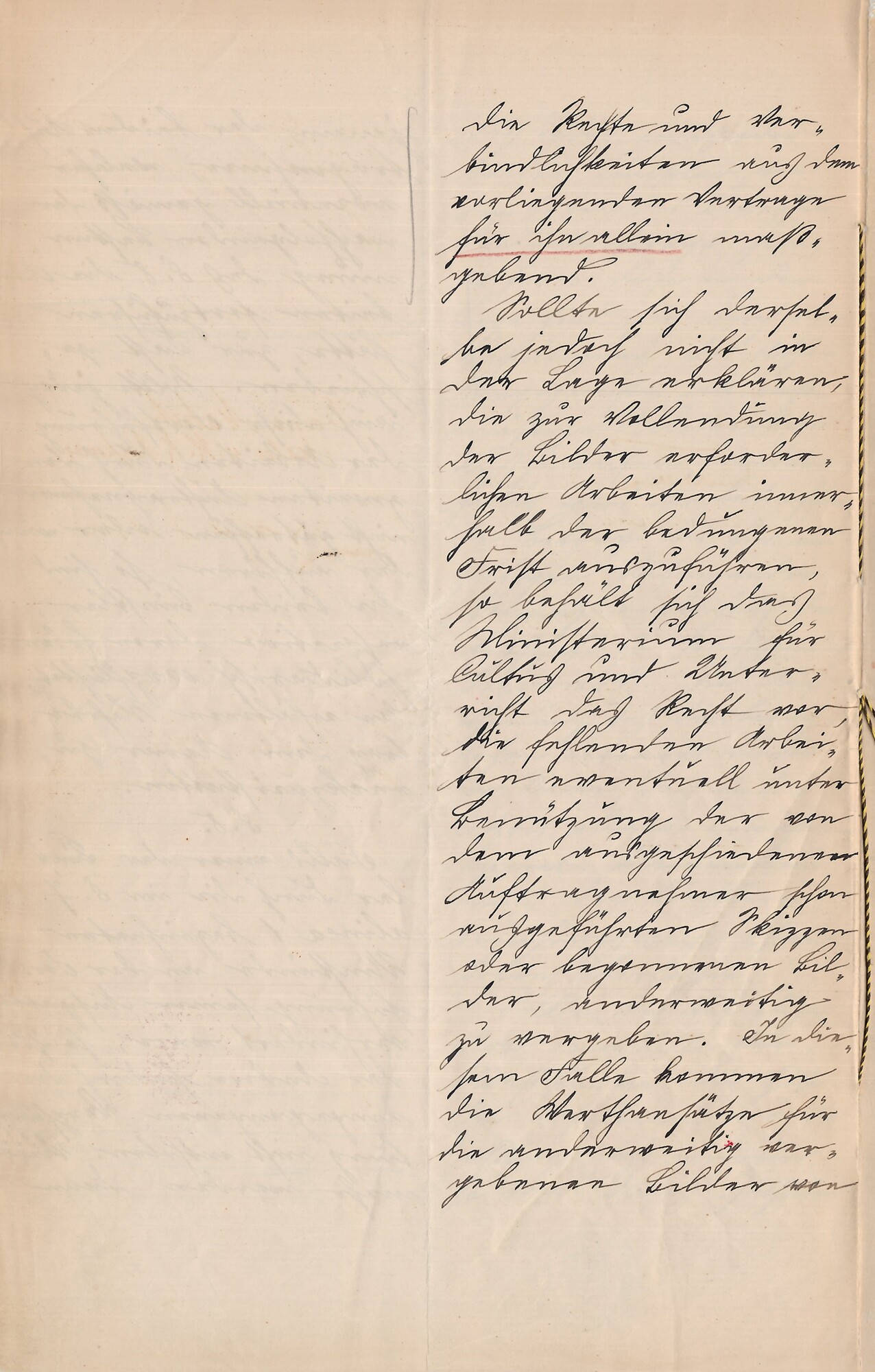

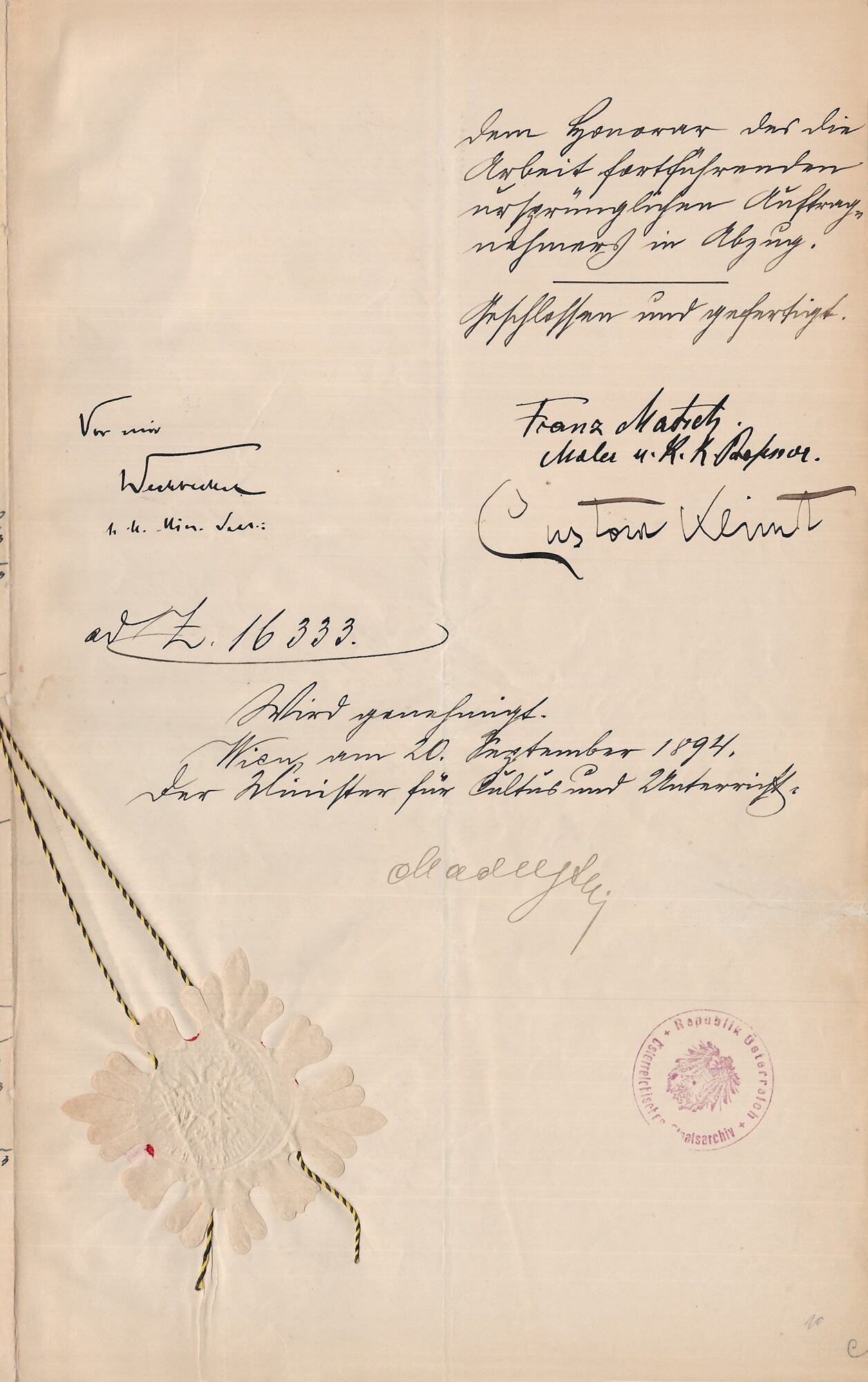

Protocol declaration concerning the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, signed by Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch, Wilhelm Weckbecker and Stanislaus Ritter Madeyski von Poray, 09/20/1894, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

Protocol declaration concerning the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, signed by Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch, Wilhelm Weckbecker and Stanislaus Ritter Madeyski von Poray, 09/20/1894, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

© Austrian State Archives, Vienna -

Protocol declaration concerning the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, signed by Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch, Wilhelm Weckbecker and Stanislaus Ritter Madeyski von Poray, 09/20/1894, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

Protocol declaration concerning the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, signed by Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch, Wilhelm Weckbecker and Stanislaus Ritter Madeyski von Poray, 09/20/1894, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

© Austrian State Archives, Vienna -

Protocol declaration concerning the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, signed by Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch, Wilhelm Weckbecker and Stanislaus Ritter Madeyski von Poray, 09/20/1894, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

Protocol declaration concerning the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, signed by Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch, Wilhelm Weckbecker and Stanislaus Ritter Madeyski von Poray, 09/20/1894, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

© Austrian State Archives, Vienna -

Protocol declaration concerning the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, signed by Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch, Wilhelm Weckbecker and Stanislaus Ritter Madeyski von Poray, 09/20/1894, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

Protocol declaration concerning the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, signed by Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch, Wilhelm Weckbecker and Stanislaus Ritter Madeyski von Poray, 09/20/1894, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

© Austrian State Archives, Vienna -

Protocol declaration concerning the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, signed by Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch, Wilhelm Weckbecker and Stanislaus Ritter Madeyski von Poray, 09/20/1894, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

Protocol declaration concerning the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, signed by Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch, Wilhelm Weckbecker and Stanislaus Ritter Madeyski von Poray, 09/20/1894, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

© Austrian State Archives, Vienna -

Protocol declaration concerning the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, signed by Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch, Wilhelm Weckbecker and Stanislaus Ritter Madeyski von Poray, 09/20/1894, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

Protocol declaration concerning the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, signed by Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch, Wilhelm Weckbecker and Stanislaus Ritter Madeyski von Poray, 09/20/1894, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

© Austrian State Archives, Vienna -

Protocol declaration concerning the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, signed by Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch, Wilhelm Weckbecker and Stanislaus Ritter Madeyski von Poray, 09/20/1894, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

Protocol declaration concerning the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, signed by Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch, Wilhelm Weckbecker and Stanislaus Ritter Madeyski von Poray, 09/20/1894, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

© Austrian State Archives, Vienna -

Protocol declaration concerning the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, signed by Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch, Wilhelm Weckbecker and Stanislaus Ritter Madeyski von Poray, 09/20/1894, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

Protocol declaration concerning the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, signed by Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch, Wilhelm Weckbecker and Stanislaus Ritter Madeyski von Poray, 09/20/1894, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

© Austrian State Archives, Vienna -

Protocol declaration concerning the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, signed by Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch, Wilhelm Weckbecker and Stanislaus Ritter Madeyski von Poray, 09/20/1894, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

Protocol declaration concerning the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, signed by Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch, Wilhelm Weckbecker and Stanislaus Ritter Madeyski von Poray, 09/20/1894, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

© Austrian State Archives, Vienna -

Protocol declaration concerning the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, signed by Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch, Wilhelm Weckbecker and Stanislaus Ritter Madeyski von Poray, 09/20/1894, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

Protocol declaration concerning the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, signed by Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch, Wilhelm Weckbecker and Stanislaus Ritter Madeyski von Poray, 09/20/1894, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

© Austrian State Archives, Vienna -

Protocol declaration concerning the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, signed by Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch, Wilhelm Weckbecker and Stanislaus Ritter Madeyski von Poray, 09/20/1894, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

Protocol declaration concerning the ceiling paintings for the ballroom of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna, signed by Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch, Wilhelm Weckbecker and Stanislaus Ritter Madeyski von Poray, 09/20/1894, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

© Austrian State Archives, Vienna

Franz Matsch sen.: Victory of light over darkness (design), around 1894, The Albertina Museum, Vienna

©

Awarding of the Commission

On 4 September 1894, the execution of the ceiling paintings for the auditorium of the Imperial-Royal University of Vienna by Klimt and Matsch was ceremonially declared in the ministry and approved on 20 September 1894.

The two painters undertook to decorate the large, central area and the four side panels with allegorical compositions representing the faculties theology, philosophy, medicine and jurisprudence, as well as with twelve spandrel paintings showing personifications of the sciences. Matsch was tasked with decorating the central area, for which he created the allegory The Triumph of Light over Darkness, as well as the Faculty Painting Theology. Klimt was to execute the depictions of the faculties medicine, jurisprudence and philosophy.

They promised to submit color sketches of a scale of at least 1:10 to the ministry for approval before embarking on the execution of the paintings. The fee was fixed at 60,000 guilders (c. 855,586 euros), and the completion of the work agreed for the end of 1898. The contract further stated that, should one artist be unable to complete the project, the other would have to finish it in his stead.

Gustav Klimt likely began in late 1894 to create first drawings and sketches for the Faculty Paintings Medicine and Jurisprudence, while he did not start to execute studies for Philosophy until around 1897. The program for the arrangement of the ceiling and spandrel paintings was reworked several times. The artists further discussed the necessity of renting an additional studio with their commissioners, as their studio at Josefstädter Straße 21 was unable to accommodate the large-scale paintings. Seeing as they did not rent this studio, situated at nearby Florianigasse 54, until 1898, we can presume that it was only then that Klimt started to execute the monumental oil paintings.

Further contents

-

Klimt's Artworks 1895 – 1897 (Symbolism in Klimt’s Oeuvre)Faculty Paintings. First Sketches

-

Klimt's Artworks 1898 – 1900 (Cradle of Modernism)Faculty Paintings. Philosophy

-

Klimt's Artworks 1901 – 1903 (The Golden Knight and Femmes Fatales)Faculty Paintings. Medicine and Jurisprudence

-

Klimt's Artworks 1904 – 1906 (The Klimt Affair Surrounding the Faculty Paintings)Faculty Paintings. The Klimt Affair

Literature and sources

- Alice Strobl: Die Fakultätsbilder »Medizin« und »Philosophie«, in: Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007, S. 41-53.

- Peter Weinhäupl: Baustelle Fakultätsbilder. Klimts streitbare Moderne, die ungewollte Anerkennung und der Untergang, in: Sandra Tretter, Hans-Peter Wipplinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Jahrhundertkünstler, Ausst.-Kat., Leopold Museum (Vienna), 22.06.2018–04.11.2018, Vienna 2018, S. 49-76.

- R. Bk.: Vermischtes, in: Kunstchronik. Wochenschrift für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, N.F., 6. Jg., Heft 8 (1894/95), Spalte 125.

- N. N.: Staatliche Kunstpflege in Österreich im Zeitraume von 1891–1895, in: Kunstchronik. Wochenschrift für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, N.F., 6. Jg., Heft 17 (1894/95), Spalte 257-265.

- N. N.: Deckengemälde für den großen Festsaal der Universität in Wien, in: Mittheilungen des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie. Monatsschrift für Kunst und Gewerbe, N.F., 9. Jg., Heft 10 (1894), S. 248.

- Alice Strobl: Die Entwürfe für Klimts Fakultätsbilder »Medizin« und »Philosophie«, in: Stephan Koja (Hg.): Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst. Sonderband Gustav Klimt, Vienna 2007, S. 38-53.

- N.N.: Kleine Chronik. Personal-Nachrichten, in: Neue Freie Presse, 21.06.1893, S. 1.

- Protokollarische Erklärung betreffend die Deckengemälde für den Festsaal der k. k. Universität Wien, unterschrieben von Gustav Klimt und Franz Matsch, Wilhelm Weckbecker und Stanislaus Ritter Madeyski von Poray (09/20/1894). AT-OeSTA/AVA Unterricht UM allg. Akten 739, ZI. 16.333/1894 fol. 5-10, .

- Brief vom Rektorat der k. k. Universität Wien an die artistische Kommission der k. k. Universität Wien, unterschrieben von Laurenz Müllner (11/17/1894). S102.31.4, .

- Brief vom k. k. Ministerium für Cultus und Unterricht an das Rektorat der k. k. Universität Wien (09/20/1894). S102.31.2, .

- N. N.: Deckengemälde in der Universität, in: Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 26.09.1894, S. 5.

- N. N.: Deckengemälde für den großen Festsaal der Universität in Wien, in: Wiener Zeitung, 26.09.1894, S. 4.

- Akt betreffend die Deckengemälde für den Festsaal der k. k. Universität Wien, Teil 1 (07/09/1894). AT-OeSTA/AVA Unterricht UM allg. Akten 739, ZI. 16.333/1894 fol. 1-4, .

Klimt and the Vienna Künstlerhaus

Vienna Künstlerhaus photographed by Leopold Theodor Neumann, around 1875

© Wien Museum

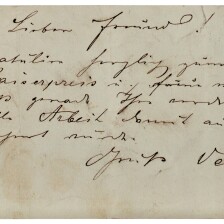

Gustav Klimt: Gustav Klimt's Declaration of Admission to the Cooperative of Fine Artists of Vienna, 03/25/1891, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna

In March 1891, Gustav Klimt joined the Cooperative of Visual Artists in Vienna as a member. He was able to benefit from the institution’s network for acquiring new commissions, was appointed to various committees, and took part in numerous exhibitions, until he left the organization in 1897 in the course of the foundation of the Vienna Secession.

The Cooperative of Visual Artists in Vienna, also referred to as Vienna Künstlerhaus, was established in 1861 as a professional association of painters, sculptors, and architects. In the years to come, it would function as a central association of artists beyond Vienna’s borders. Its own exhibition venue and clubhouse, briefly called Künstlerhaus, opened in 1868 in the vicinity of the Wienfluss, serving the members as an exhibition and sales platform. The Cooperative also organized artists’ balls and rented its facilities to art dealers and gallery owners for profit-oriented auctions.

Having successfully completed late Historicist decoration programs together with his brother Ernst and Franz Matsch, Gustav Klimt presented the gouache Auditorium of the Old Burgtheater (1888, Wien Museum, Vienna) at the “XIX. Jahresausstellung der Genossenschaft der bildenden Künstler Wiens” [“19th Annual Exhibition of the Cooperative of Visual Artists in Vienna”] in 1890. He was awarded the Emperor’s Prize, which was also organized by the Cooperative and came with a substantial amount of money.

Klimt Joining the Cooperative

In March 1891, Klimt applied for membership in writing to the Cooperative’s committee and was admitted by the association, which meanwhile had some 300 ordinary members. The professional association played an important economic role as an agency between audience and artists through its national and international contacts with potential clients. Through this network, Gustav Klimt also met the collector and Ringstraße patron Nicolaus Dumba, who entrusted him with several commissions. Moreover, he was appointed to committees assigning public projects, was active in the Cooperative’s exhibition and admission committees, and made use of the numerous opportunities of exhibiting his own work. For example, he displayed his art not only at the Künstlerhaus, but also at the “Exposition Universelle des Beaux-Arts” in Antwerp in 1894 in the context of the World’s Fair, and during his membership developed from Historicist decorator to portraitist of the high society. At the “III. Internationale Kunst-Ausstellung” [“3rd International Art Exhibition”] at the Künstlerhaus, he showed, among other works, Portrait of Franz Trau (c. 1893, private collection).

Klimt’s Resignation

Tensions within the tradition-minded Cooperative of Visual Artists in Vienna had existed since the mid-1890s. A group of artists around Carl Moll and Gustav Klimt primarily sought to renew the Cooperative’s exhibition policy and intensify its international orientation on the art scene. As their ambitions met with little approval, the Association of Austrian Artists Secession was founded in 1897. Klimt was the Secession’s first president and left the Cooperative of Visual Artists in Vienna on 24 May 1897.

Literature and sources

- K.: Das Künstlerhaus in Wien. Von Architekt August Weber, in: Allgemeine Bauzeitung, 1881, S. 67-68.

- Oskar Pausch: Gründung und Baugeschichte der Wiener Secession. Mit Erstedition des Protokollbuches von Alfred Roller, Vienna 2006.

- Patrick Fiska, Holger Englerth: Ohne Klimt. Klimt und das Künstlerhaus, in: Peter Bogner, Richard Kurdiovsky, Johannes Stoll (Hg.): Das Wiener Künstlerhaus. Kunst und Institution, Vienna 2015, S. 277-283.

- Christian Huemer: Jahrmarktbude oder Musentempel? Das Wiener Künstlerhaus und der Kunsthandel, in: Peter Bogner, Richard Kurdiovsky, Johannes Stoll (Hg.): Das Wiener Künstlerhaus. Kunst und Institution, Vienna 2015, S. 267–275.

- Wien Geschichte Wiki. Künstlerhaus. www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/K%C3%BCnstlerhaus (04/14/2020).

- Brief von Gustav Klimt in Wien an die Genossenschaft der bildenden Künstler Wiens, März 1891, .

- Verzeichnis der 2. und 3. Gemäldesendung der Genossenschaft bildender Künstler Wiens an die Weltausstellung in Antwerpen (06/13/1894). Mappe Antwerpen Weltausstellung A 1894, .

- Brief von Gustav Klimt an die Genossenschaft der bildenden Künstler Wiens, verfasst von fremder Hand (05.04.1897). Mappe Gustav Klimt, .

- Brief verfasst von Alfred Roller an den Ausschuss der Genossenschaft der bildenden Künstler Wiens, unterzeichnet von Gustav Klimt, Carl Moll, Rudolf Bacher, Ernst Stöhr, Johann Victor Krämer, Joseph Maria Olbrich, u.a., Austrittsgesuch (05/24/1897). Mappe Gustav Klimt, .

- Wladimir Aichelburg: Das Wiener Künstlerhaus. 125 Jahre in Bilddokumenten, Vienna 1986.

- Wladimir Aichelburg: Das Wiener Künstlerhaus 1861–2001, Band 1, Vienna 2003.

Homage addresses

Homage address for Carl von Hasenauer, 1888/89, Theatermuseum

© KHM-Museumsverband

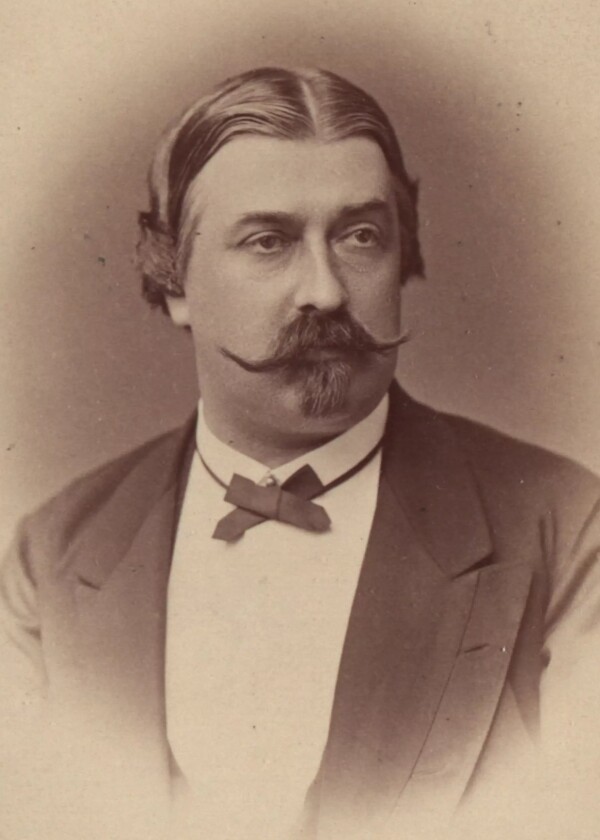

Carl Hasenauer photographed by Ludwig Angerer, around 1868, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

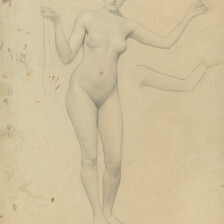

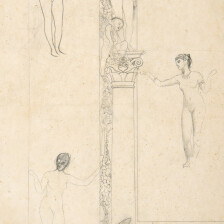

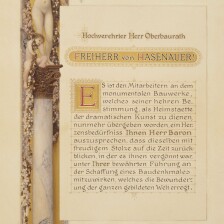

In 1888/89, Gustav Klimt was involved in the design of an homage address for Carl Hasenauer, the architect of the Imperial-Royal Court Theater, as well as a commemorative publication for the 25th anniversary of the Imperial-Royal Museum of Art and Industry. In his graphic contributions, Klimt developed an increasingly stylized type of female nude

On 21 January 1889, a delegation of renowned Viennese architects and industrialists led by Theophil Hansen presented Carl Hasenauer, the architect of the Imperial-Royal Court Theater, with an homage address (1888/89, Theatermuseum, Vienna) as a token of their appreciation and respect. This gesture was primarily brought about by growing public criticism of the new theater on Vienna’s Ringstraße (now Burgtheater, Vienna), with repeated complaints about the poor acoustics on the stage and in the auditorium. According to a newspaper report, Hasenauer’s advocates read out the following message when presenting the homage address:

“Dear and venerated master! At a time when your artistic honor is so unjustly under attack, with no regard for the consequences, the undersigned feel obliged to express their irrevocable respect for your art.”

According to contemporary reports, the signatories included renowned protagonists of Vienna’s political and cultural scene, such as Nikolaus Dumba, Otto Wagner, Ferdinand Fellner jr. and Hermann Helmer as well as Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch.

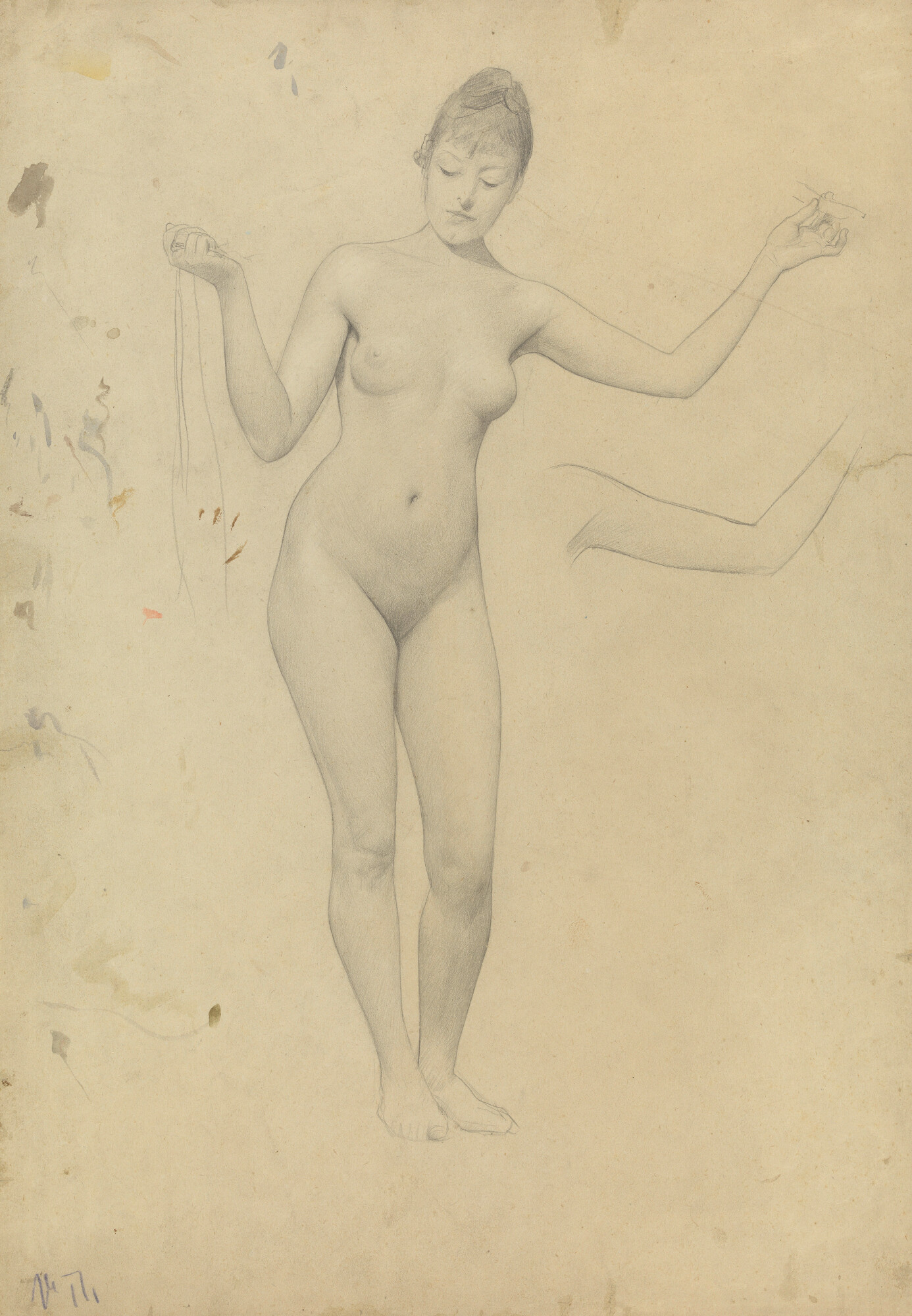

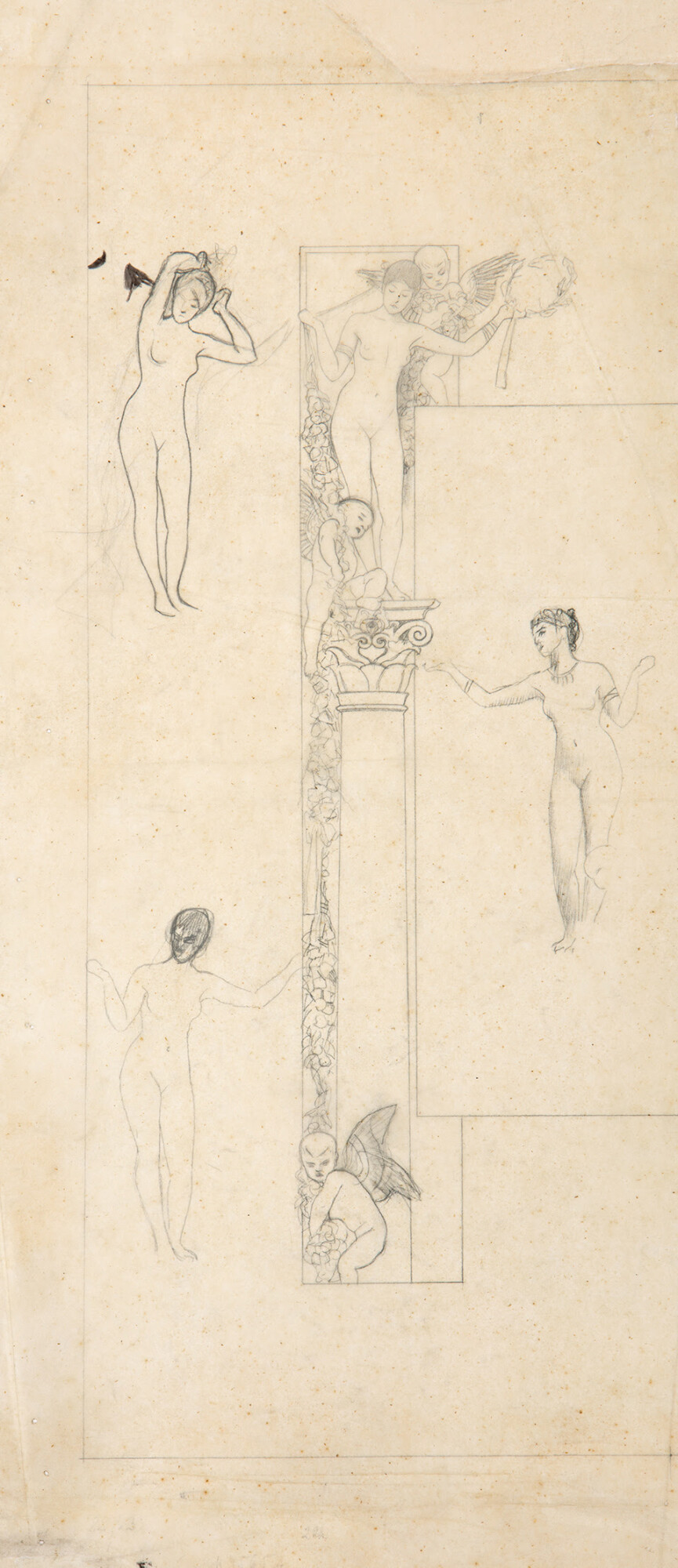

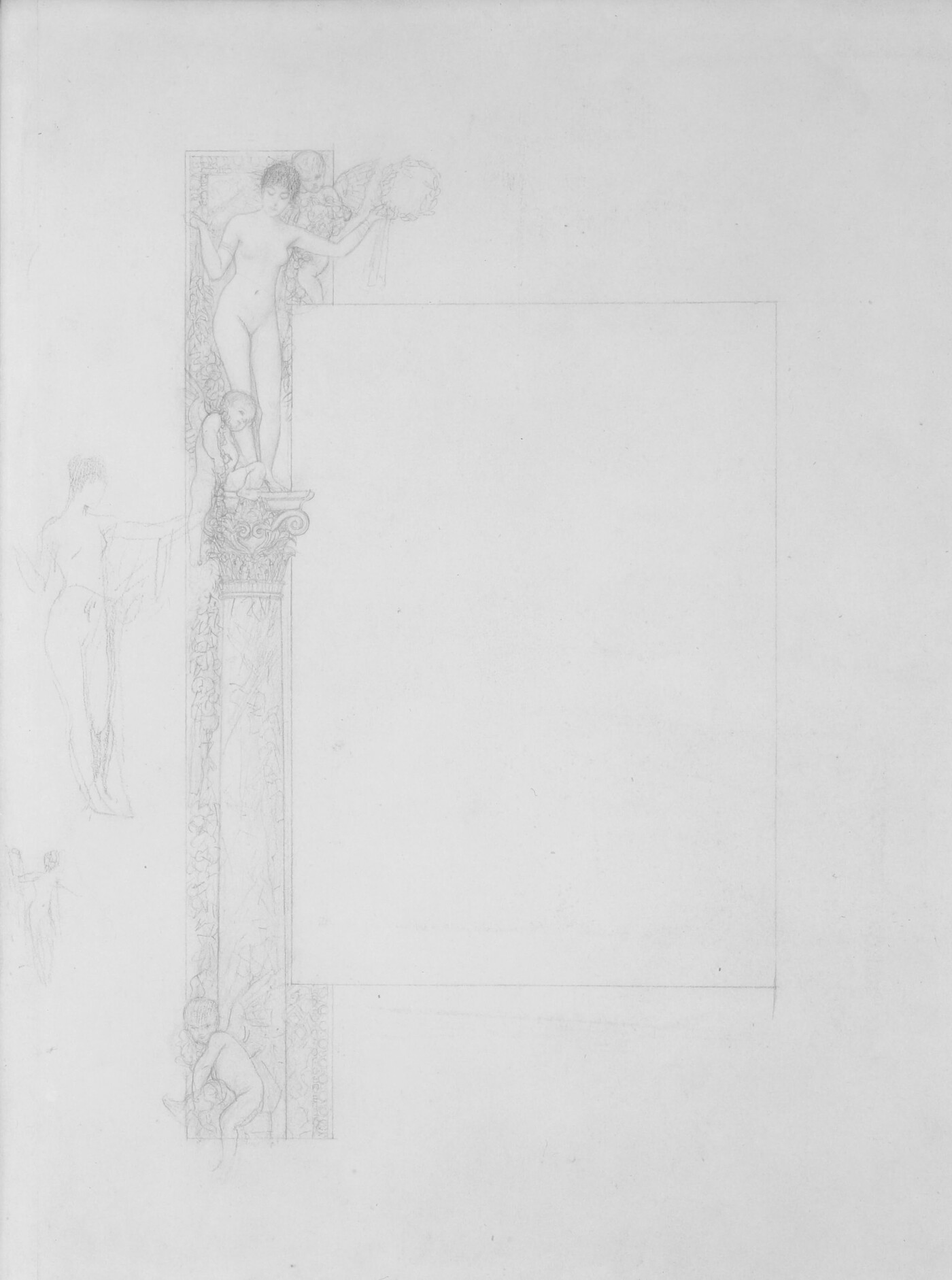

Klimt’s artistic contribution to this homage address was a document page with a decoration in the margin executed in the form of a miniature in opaque colors and golden highlights. On a high, classic marble column with a composite capital, a female nude – probably the personification of fame – is offering a golden wreath of laurels. Klimt enlivened the motif with three putti bearing flower garlands. The vertical composition, which Klimt positioned on the left side of the page, is framed by a cymatium motif. The same female type was also used in the painting Allegory of Sculpture (1889, MAK, Vienna), which Klimt executed for the second homage address.

Sketches, revised drawing and final execution of the document page

-

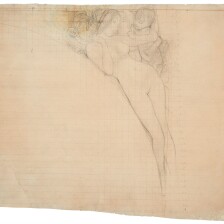

Gustav Klimt: Standing female nude and arm study, 1888/89, Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Standing female nude and arm study, 1888/89, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum -

Gustav Klimt: Study for the overall composition of the homage address and various position studies for the main figure, 1888/89, private collection

Gustav Klimt: Study for the overall composition of the homage address and various position studies for the main figure, 1888/89, private collection

© W&K – Wienerroither & Kohlbacher -

Gustav Klimt: Study for the overall composition of the homage address and various position studies for the main figure, 1888/89, private collection

Gustav Klimt: Study for the overall composition of the homage address and various position studies for the main figure, 1888/89, private collection

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Homage address for Carl von Hasenauer, 1888/89, Theatermuseum

Homage address for Carl von Hasenauer, 1888/89, Theatermuseum

© KHM-Museumsverband

Commemorative publication on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the Imperial and Royal Austrian Museum of Art and Industry, 1889, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

© MAK

Gustav Klimt: Allegory of sculpture, 1889, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

© MAK

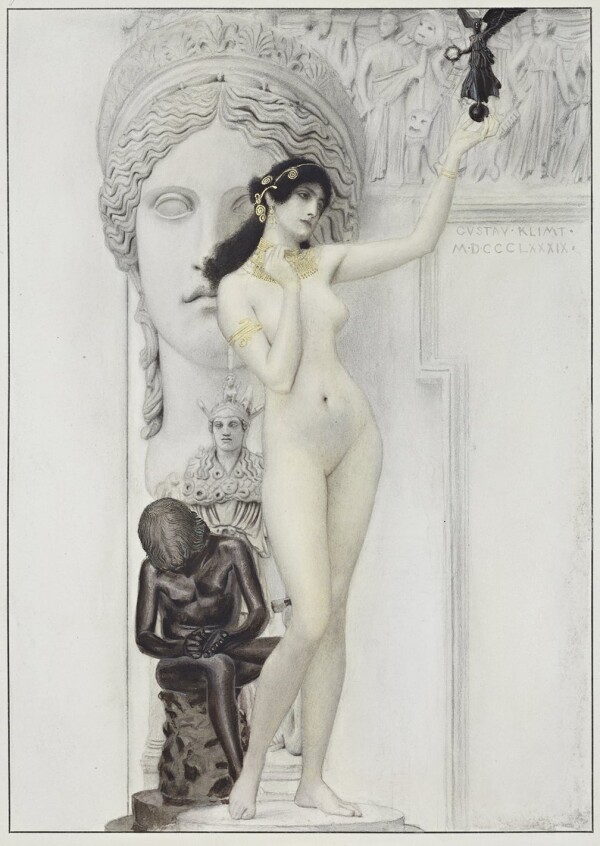

Homage Address for Archduke Rainer

On the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the Imperial-Royal Museum of Art and Industry in 1889, a commemorative publication was created for Archduke Rainer, the institution’s imperial patron (1889, MAK, Vienna). It was presented at a ceremony held in the museum’s assembly hall on 24 June 1889 and was attended by all artists involved. The contents of this masterfully executed commemorative publication in the form of a book were conceived and illustrated by teachers as well as former and contemporary students of the School of Arts and Crafts (now University of Applied Arts Vienna), including Hrachowina, Minnigerode, Rieser. The “Künstler-Compagnie” took on the special task of designing the cover pages for the three main artistic genres as page-filling illustrations: Ernst Klimt thus created the Allegory of Painting (1889, MAK, Vienna) for the homage address, while Franz Matsch executed the Allegory of Architecture (1889, MAK, Vienna). Meanwhile, Gustav Klimt was responsible for rendering the Allegory of Sculpture.

The personification of sculpture is a nude inspired by antiquity and depicted in a gracious pose carrying a small bronze of the goddess Victoria (Nike). The allegory of sculpture is standing in front of a bronze Boy with Thorne, a scaled-down image of Pallas Athena and a monumental head of Juno. An antique relief with a symbolic depiction of theater runs along the upper edge, not unlike an architrave. The combination of black, curly hair and gilded jewelry resurfaces in the following decade in the designs for Allegories and Emblems. New Series on which Gustav Klimt worked between 1895 and 1897. The first works of the Golden Period, created from the late 1890s – such as Pallas Athena (1898, Wien Museum) – share the same characteristics.

Literature and sources

- Marian Bisanz-Prakken (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Ausst.-Kat., Albertina (Vienna), 14.03.2012–10.06.2012; Getty Center (Los Angeles), 03.07.2012–23.09.2012, Munich 2012, S. 46-51.

- Wiener Abendpost. Beilage zur Wiener Zeitung, 21.01.1889, S. 3-4.

- Wilhelm Mrazek: Die Huldigungsgabe der Kunstgewerbeschule an Erzherzog Rainer aus Anlass des 25jährigen Jubiläums des k. k. Österreichischen Museums im Jahre 1889, in: Alte und moderne Kunst. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Kunst, Kunsthandwerk und Wohnkultur, 23. Jg., Heft 158 (1978), S. 13-16.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band I, 1878–1903, Salzburg 1980, S. 78-79.

- Mittheilungen des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie. Monatsschrift für Kunst und Gewerbe, N.F., 4. Jg., Heft 43 (1889), S. 409-411.

- Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, 22.01.1889, S. 2.

- Die Presse, 22.01.1889, S. 9.

- Wiener Zeitung, 21.01.1889, S. 3-4.

- Die Kunst für Alle. Malerei, Plastik, Graphik, Architektur, 14. Jg. (1898/99), S. 141.

- Otmar Rychlik (Hg.): Gustav Klimts Lehrer. 1876-1882. Sieben Jahre an der Kunstgewerbeschule, Ausst.-Kat., MAK - Museum of Applied Arts (Vienna), 03.11.2021–13.03.2022, Bad Vöslau 2021, S. 196-201.

- Die Presse, 24.06.1889, S. 3.

- Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, 25.06.1889, S. 5.

- Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 24.06.1889, S. 3.

- Neue Freie Presse, 18.04.1897, S. 1-2.

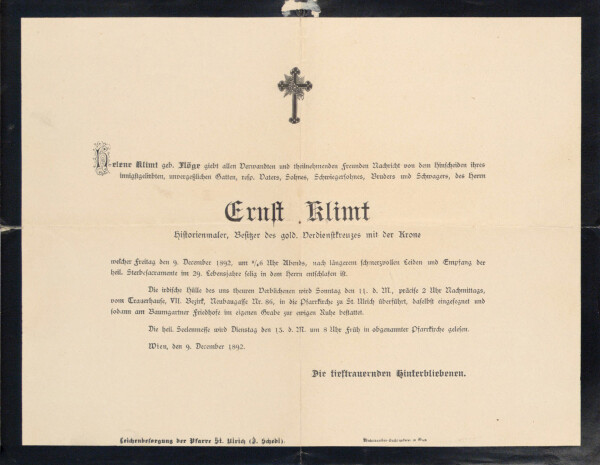

Ernst Klimt’s Artistic Legacy

Ernst Klimt: Hanswurst on the fairground stage, 1886-1888, Burgtheater Vienna

© Georg Soulek

Helene Klimt: Death Notice of Ernst Klimt jun., written by his family, 12/09/1892, The Albertina Museum

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

When Ernst Klimt passed away on 9 December 1892, he left the second version of his work Hanswurst Delivering an Impromptu Performance in Rothenburg unfinished. Gustav completed his brother’s oil painting, with members of the Flöge and Klimt families posing as his models

The ceiling painting Hanswurst Delivering an Impromptu Performance in Rothenburg (1886–1888) was Ernst Klimt’s most notable contribution to the decoration of the staircases of the Imperial-Royal Court Theater (now Burgtheater, Vienna) and his greatest success. Seeing as the character of Hanswurst enjoyed huge popularity around 1890, Ernst Klimt revisited the composition as an easel painting, likely for a private commissioner: Hanswurst Delivering an Impromptu Performance in Rothenburg (1892–1894, private collection). However, the painter died on 9 December 1892, before he was able to finish the work. Gustav Klimt took over the painting’s completion, but, owing to personal inhibitions and several fundamental adaptations, was only able to finish it in 1893/94. In early 1895, the work was posthumously displayed under Ernst Klimt’s name at the annual exhibition of the Künstlerhaus, and was purchased by a certain “V. Wokaun,” presumably the Prague businessman Viktor Wokaun, for 8400 guilders (c. 126,800 euros).

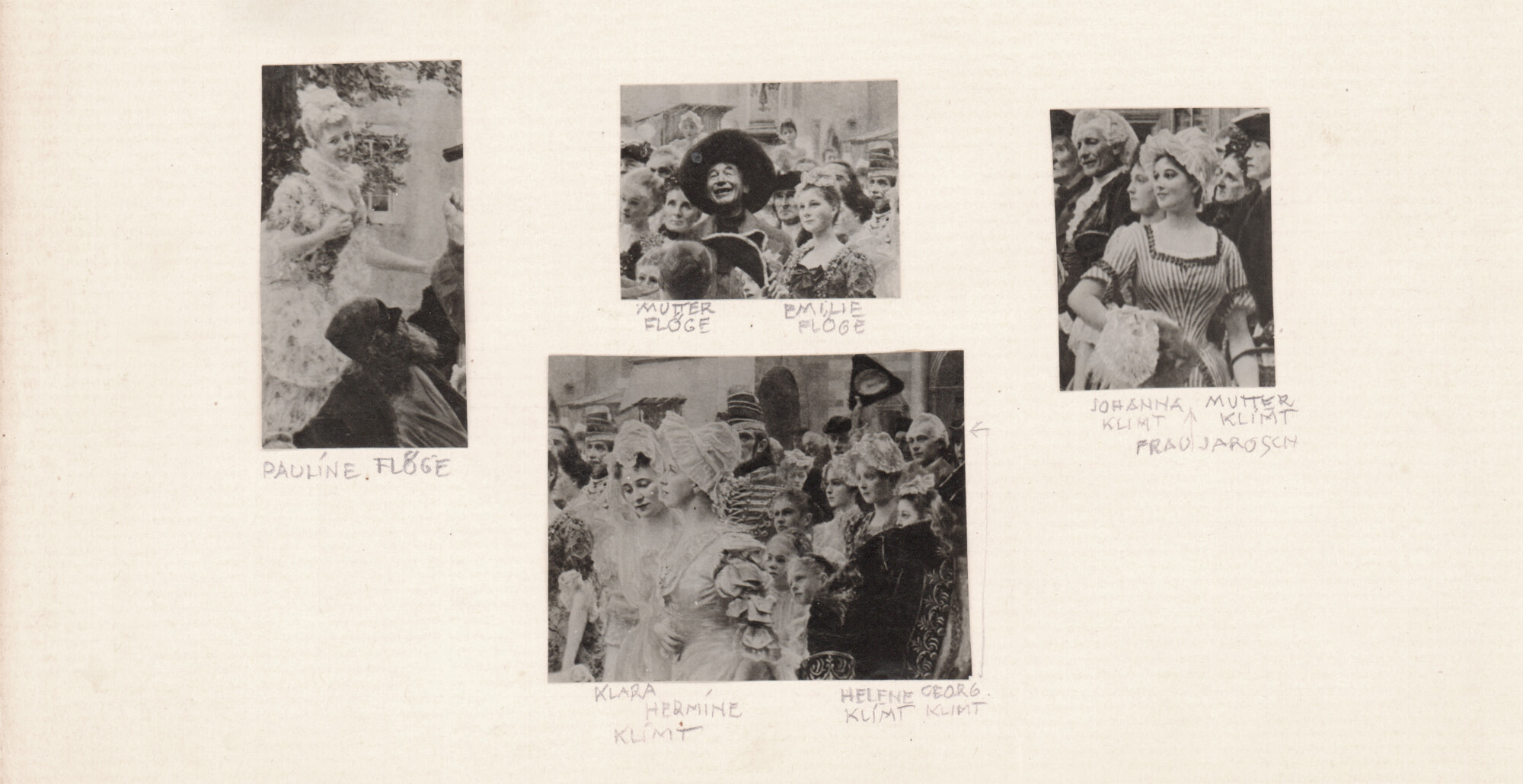

A Portrait of the Klimt and Flöge Families

As with the large-scale ceiling painting in the Burgtheater, numerous portraits of family members were incorporated into this painted scenic depiction by Ernst and Gustav Klimt. The portrait quality of the renderings of audience members was to give the work authenticity.

Gustav Klimt: Hanswurst Delivering an Impromptu Performance in Rothenburg, 1892-1894, private collection

© Sotheby's

In his family chronicles Chronik über das Leben der Familie Klimt, Gustav and Ernst’s younger brother Georg Klimt identified the various depicted persons. The three Flöge sisters – Gustav’s sister-in-law Helene Klimt, Pauline and Emilie Flöge – feature both on stage and in the audience. There are also two surviving cartoons with studies for the painting – both likely painted by Gustav Klimt – which show Pauline and Emilie wearing the same red and green rococo suits. The postures of the depicted correspond to the composition of the painting. Further among the audience members are Gustav and Ernst’s siblings Klara, Hermine and Georg Klimt, as well as the mothers of the two families, Barbara Flöge and Anna Klimt.

Georg Klimt: Chronicle of the life of the Klimt family, 1924, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Portrait Studies of the Flöge Sisters

-

Gustav Klimt: Pauline Flöge in a Rococo Costume, 1892-1894, ARGE Sammlung Gustav Klimt, Dauerleihgabe im Leopold Museum, Wien, Permanent Loan, Leopold Museum, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Pauline Flöge in a Rococo Costume, 1892-1894, ARGE Sammlung Gustav Klimt, Dauerleihgabe im Leopold Museum, Wien, Permanent Loan, Leopold Museum, Vienna

© Leopold Museum, Vienna -

Gustav Klimt: Emilie Flöge in a Rococo Costume, 1892-1894, private collection

Gustav Klimt: Emilie Flöge in a Rococo Costume, 1892-1894, private collection

© APA-PictureDesk

Die Graphischen Künste, 18. Jg., Heft 4+5 (1895).

© Heidelberg University Library

Reviews and Reproductions

In their praise, the critics emphasized what they called the “Viennese” aspect of the figures and the historical rendering of the costumes. By finishing the painting, Gustav Klimt had managed to memorialize his brother, who died an untimely death. A review in the newspaper Wiener Zeitung in early 1896 read:

“This Hanswurst does not lie when he claims that charming Viennese girls and women are crowding his stage in naive rapture, for the beauty of Viennese women has never been a hollow illusion. The Viennese womanizers of the time in their wide-skirted, braided coats, knee breeches and buckled shoes [...], too, would have looked much like they were depicted here by Klimt. We will always remember the painter with wistfulness; he was only 28 when he departed this world [...].”

It seems that it was especially the composition’s merging of contemporary portraits of Viennese society with historical documentation that charmed Viennese viewers. Gustav Klimt had previously demonstrated his mastery in this field with his gouache Auditorium of the Old Burgtheater (1888, Wien Museum).

In December 1895, the Gesellschaft für Vervielfältigende Kunst [Society for Reproductive Art] issued a halftone print of the oil painting Hanswurst Delivering an Impromptu Performance in Rothenburg. Gustav Klimt had ceded the image rights for 200 guilders (c. 2850 euro) as well as 6 trial copies of the reproduction to the printing house. The painting’s reproductions vastly increased the work’s popularity and further contributed to Ernst Klimt’s posthumous fame.

Literature and sources

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007.

- Toni Stoos, Christoph Doswald (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Ausst.-Kat., Kunsthaus Zurich (Zurich), 11.09.1992–13.12.1992, Stuttgart 1992.

- Chronik über das Leben der Familie Klimt, "DAS LEBEN DES GUSTAV KLIMT UND SEINER FAMILIE" (1924). S16/1.

- Tobias G. Natter, Gerbert Frodl (Hg.): Klimt und die Frauen, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 20.09.2000–07.01.2001, Cologne 2000, S. 76.

- Josef Bayer: Das K. K. Hofburgtheater als Bauwerk mit seinen Sculpturen und Bilderschmuck, in: Gesellschaft für Vervielfältigende Kunst (Hg.): Die Theater Wiens, Band III, Vienna 1894.

- Martina Leitner: Die Familie Flöge, in: Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Emilie Flöge. Reform der Mode. Inspiration der Kunst, Vienna 2016, S. hier S. 102, S. 99-112.

- Brief von Gustav Klimt an Unbekannt (04/05/1895). 18.2.2.4577, .

- Revers der Gesellschaft für Vervielfältigende Kunst von Gustav Klimt (04/27/1895).

- Wiener Zeitung, 01.01.1896, S. 8.

Stylized and Naturalistic Portraits

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Joseph Pembaur, 1890, Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum

© Scala Florence

Between 1889 and 1894, the artist painted numerous naturalistic portraits. Although they are mostly characterized by an extremely realistic painting style, in some cases the first attempts of stylization and open brushwork become evident. These already point to the future development within the movement of the Secession.

Especially in the genre of portraiture, Gustav Klimt’s early style was dominated by a naturalistic rendering of his sitters. He mainly depicted ladies of society. Male portraits were an exception. Klimt increasingly enriched his naturalistic portraits with symbols from antiquity and abstract ornamental backgrounds. This increasing tendency toward stylization would become stronger in the artist’s later years.

A Composer’s Idealization

As Franz Matsch reported, Klimt painted Portrait of Joseph Pembaur (1890, Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum, Innsbruck) for the regulars’ table of the newly founded Pembaur Society, which was based at a Viennese beer pub called Spatenbräu:

“Klimt also painted Pembauer [!] for our pub room, with a golden lyre and laurels.”

Klimt painted the picture as a member of said society, so it was probably not a commissioned work in the traditional sense. When the Spatenbräu was closed down, the work apparently passed into the possession of the society’s initiator, Georg Reimers. In any case, the Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum acquired it from his estate auction in 1936.

Plate CCCXIX, in: Eduard Gerhard (Hg.): Auserlesene Griechische Vasenbilder, hauptsächlich Etruskischen Fundorts, Band 2, Berlin 1843.

© Heidelberg University Library

Naturalism and Antiquity

It seems that the composer’s naturalistically painted portrait was based on a photograph. At least this is suggested by the uncompromisingness and directness of the depiction, even if the specific portrait photograph could not be found. Klimt dated the work in the upper right corner in Roman numerals: “ANNO DOMINI 1890.” On the gold painted frame appear various symbols and allegories from antiquity as attributes alluding to Joseph Pembaur’s activity as a composer and musician: Apollo Citharoedus, the Greek god of the arts and leader of the Muses, is shown standing on an Ionic column with his attribute, the cithara. The column is surrounded by stylized seawater and jumping dolphins. A tripod on the left, stars at the top, as well as the trademark of the Munich beer brewery Spatenbräu and two heads at the bottom make the eclectic golden frame complete. Such an integration of the picture frame into the composition could already be observed in previous years in the designs for Allegorien und Embleme [“Allegories and Emblems”] and in the pastel Bust of Emilie Flöge at the Age of Eighteen (c. 1891, private collection), which dates from about the same time.

Portrait of Joseph Pembaur is one of the rare male portraits in Klimt’s oeuvre. In the subsequent years, however, he repeatedly used elements from the ancient language of form as universal symbols for music and inspiration. Examples are the overdoor entitled Music (1897/98, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945) for the Dumba Music Salon and The Beethoven Frieze (1901/02, Belvedere, Vienna).

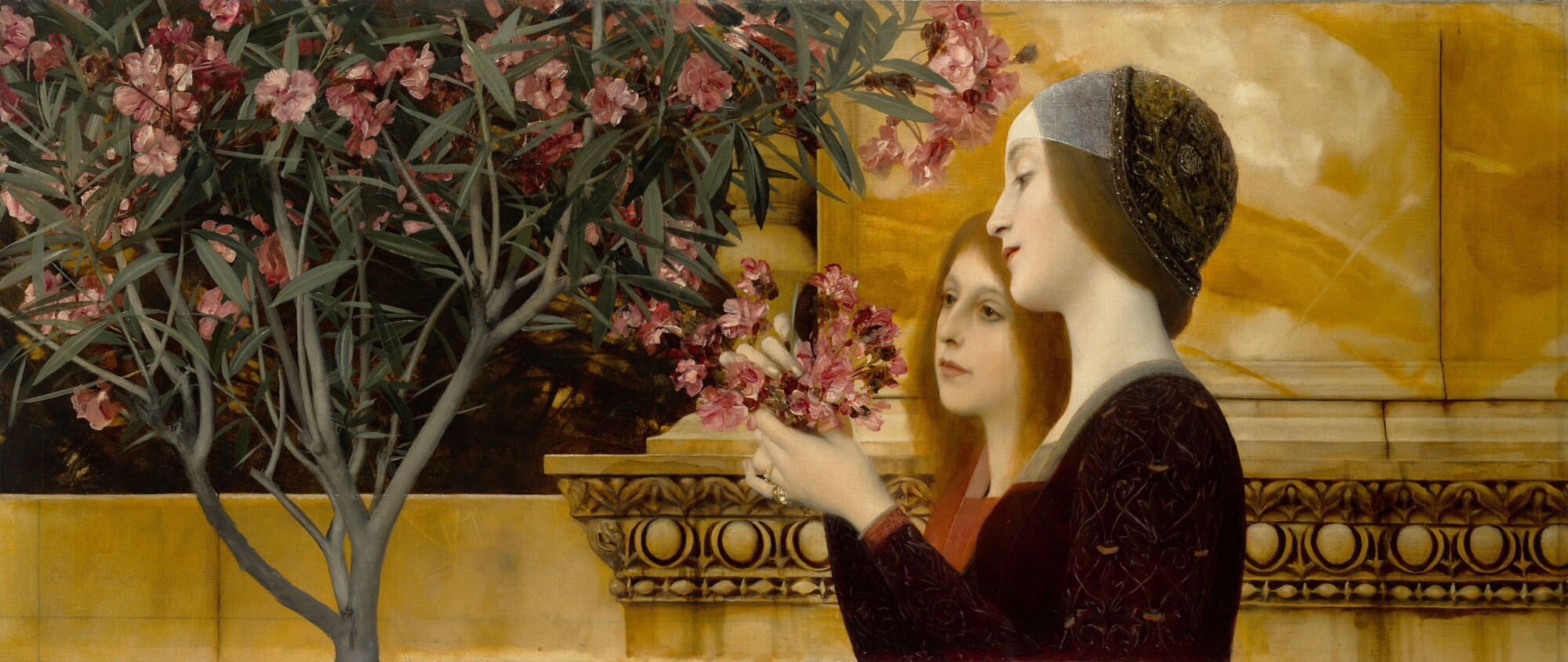

Two Girls with Oleander

When Klimt worked on Pembauer’s portrait, he also painted a genre picture in a narrow landscape format, which was unusual for Klimt. So far, it has not been possible to find out why the painting Two Girls with Oleander (1890–1892, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut) features such an unusual format for Klimt. However, the composition’s emphasized view from below could indicate that the painting was intended as an overdoor.

Gustav Klimt: Two Girls with Oleander, 1890-1892, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, The Douglas Tracy Smith and Dorothy Potter Smith Fund and The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund

© Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art

Francesco Laurana: Female bust, ideal portrait of Laura (?), c. 1490 (?), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

© KHM-Museumsverband

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Marie Kerner von Marilaun as a Bride, 1891/92, private collection

© Belvedere, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Franz Trau, circa 1893, private collection

© Gallery Welz Salzburg

Stylistically, the depiction is reminiscent of Klimt’s decorations painted between 1886 and 1888 for the staircase of the Imperial-Royal Court Theater (now Burgtheater, Vienna) and the wall paintings also executed around that time in the spandrels and between the columns at the Imperial-Royal Art History Museum (now Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna). The flower picker’s clothes and hairstyle were inspired by Francesco Laurana’s Female Bust in the imperial Kunstkammer (now Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), painted around 1490. Gustav Klimt probably had a chance to study the work in situ in the context of his commission for the decoration of the staircase.

Klimt executed his realistic portraits in the Historicist manner, in the style of the Renaissance. The composition is structured with the strict linearity of antique architecture in mind. With this rigid pictorial structure, Klimt alludes to the Renaissance and the geometrically constructed pictorial compositions typical of the period. Unlike Portrait of Joseph Pembaur, painted around the same time, Two Girls with Oleander is a work completely committed to the Historicist style of Klimt’s academic training. There is no trace yet of an increasing stylization of the background or the first beginnings of Art Nouveau in the figures – as can partly be found in the spandrels at the Imperial-Royal Art History Museum. Rather, the painting style is reminiscent of the Dutch painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s genre-like visions of antiquity.

Commissioned Portraits

In 1893 and 1894, Gustav Klimt increasingly devoted himself commissioned portraits. In contrast to the Pembaur portrait, however, these largely remained free of ancient symbolic language and abstract backgrounds. Whereas Klimt had presumably been given free hand in the design of the commission for the Pembaur Society’s round of regulars, his clients doubtlessly had certain expectations what a portrait of their relatives or of themselves should be like. It is therefore not surprising that Klimt chose a consistently photorealistic style for his commissioned portraits, which suited contemporary taste.

Challenging Conditions for a Portrait

One of the first official portrait commissions Gustav Klimt received was for the Portrait of Marie Kerner von Marilaun as a Bride (1891/92, private collection). In November 1891, his client, Anton Kerner, had asked Klimt to paint his wife as a youthful bride. It was to be a Christmas gift for the sitter.

The portrait was created under difficult circumstances, thirty years after the marriage, on the basis of a watercolor miniature showing Marie Kerner. The lack of a photographic or living model is probably the reason why the depiction lacks Klimt’s characteristic vividness. Correspondence between the painter and the client shows that various changes and adaptations were made to increase the portrait’s likeness and liveliness:

“I could not make any more progress with the picture today, I colored the face much more vibrantly, but I only could do very little with the garment.”

The Couple of Tea Merchants

It was probably around 1893 that Klimt portrayed the well-known tea merchants Franz and Mathilde Trau. Portrait of Franz Trau (c. 1893, private collection) is the only known commissioned male portrait in oil in the painter’s œuvre. Klimt chose the type of a pair of pendants that had been known since the 15th century (1893, private collection). The two naturalistic depictions were therefore conceived in such a way that in the correct hanging – Franz on the left and his wife to his right – Mathilde would be looking directly at her husband.

Gustav Klimt: Study for "Auditorium in the Old Burgtheater", presumably 1888/89, private collection

© Auktionshaus im Kinsky GmbH, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Mathilde Trau, circa 1893, private collection, Permanent loan at the Belvedere, Vienna

© Belvedere, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of a Woman, circa 1893/94, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of a Lady (Mrs. Heymann?), circa 1894, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

In a signed watercolor sketch for Klimt’s famous commissioned work Auditorium of the Old Burgtheater (1888/89, Wien Museum, Vienna), Klimt placed the Trau couple among the audience. The way the couple is depicted there corresponds exactly to that of the two individual portraits. What is remarkable is that the two sitters are the only recognizable faces. The remaining figures look blurred. In the executed work for the City of Vienna, however, the couple is not depicted. It is possible that Klimt added the Trau couple to the sketch later on.

The style of the commissioned portraits is strongly based on Flemish portraits in terms of the somber color scheme – black dress, dark red background. The sitters’ naturalistic faces are brought to the fore through the handling of light and their pale complexion. The absence of visible brushwork ensures a totally smooth appearance. For the portrait of Mathilde’s husband, which has only survived in a black-and-white photograph, a similar color scheme can be assumed. The portrait character and three-dimensionality of the heads, as well as the naturalistic rendering of the skin and hair, make these paintings prime examples of academic painting. The red background is typical of Klimt’s portrait heads dating from those years.

For full-length portraits, on the other hand, he rather resorted to interiors. While the monochrome background corresponds to the tradition of bust portrayals, the approach already anticipates Klimt’s late work. Both the monochrome, mottled coloring and the oscillation between light and dark values without suggesting spatial depth would increasingly be taken up again in Klimt’s later paintings. The artist’s signature in golden capitals in the upper right corner corresponds to the antique script he also used in Portrait of Joseph Pembauer. It already points to Klimt’s embrace of antiquity that would increasingly manifest itself in his work around 1900.

Portraits of Beautiful Viennese Ladies

Around 1894 Klimt painted another three portraits of women, all executed in a naturalistic style. The two works Seated Young Girl (c. 1894, Leopold Museum, Vienna) and Portrait of a Woman (c. 1894, private collection), which appear to have been executed at the same time, also make use of a completely naturalistic, academic painting style. While the seated girl in her realistically formulated armchair, who could not be identified to this day, was painted in the style of the Trau couple and inscribed in a flat, red pictorial space, the lady in black is placed in a more or less articulated three-dimensional space. Scholars have identified the lady in the black dress as Marie Breunig, the wife of a Viennese master baker. This painting was one of Gustav Klimt’s first female portraits that earned him recognition as a portraitist and would later confer on him the impressive title “Painter of Women.” When the picture was first presented at the Vienna Künstlerhaus in 1894, it was above all its lifelike painting style that was praised:

»Gustav Klimt with his portrait of a lady in black (three-quarter-length), which is of great vibrancy.”

The contrast between the black dress and the white wall, which Klimt deliberately used to make the sitter the center of attention, did not go unnoticed either:

“Klimt has created a good contrast between the dark figure of his lady and the bright background.”

Portrait of a Lady (Mrs. Heymann) (c. 1894, Wien Museum, Vienna), on the other hand, already shows the artist’s initial abandonment of the classical, academic painting style. The approach is strongly reminiscent of Pembaur’s portrait. While the naturalistically rendered head, meticulously finished like in the other paintings, is in the focus of the composition, the background here is again dominated by a red mottled expanse embellished with stylized golden elements. The flat background thus deliberately oscillates between the naturalistic rendering of a wallpaper pattern and abstract pictorial components. The collar of the dress and the hair show an open brushwork and are less precisely executed than the part of the face. They indicate that in the years to come Klimt would increasingly turn to a more liberal painting style inspired by Fernand Khnopff and Impressionism.

What all of the portraits from this period share is the porcelain-like smoothness of the brushwork, the wealth of detail, and the naturalistic representation of the sitters in general. Ten years after the death of Hans Makart, who cultivated a neo-Baroque, impasto painting style, Klimt had thus finally broken away from his model.

In the design of his backgrounds, however, Klimt had already gone a step further. First approaches of a stylized ornamentalism and spaceless flatness are noticeable. Portrait of Joseph Pembaur already exhibits those symbolic elements in the style of antiquity that were typical of Klimt’s early Secession period. Portrait of a Lady (Mrs. Heymann?) reveals the first beginnings of a more open painting style. The artist had previously tried this out in his studies of Pauline and Emilie Flöge for Hanswurst Delivering an Impromptu Performance in Rothenburg (1892–1894, private collection), where he was not bound by the taste of a particular client.

Literature and sources

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007.

- Christian M. Nebehay: Gustav Klimt. Sein Leben nach zeitgenössischen Berichten und Quellen, Vienna 1969.

- Toni Stoos, Christoph Doswald (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Ausst.-Kat., Kunsthaus Zurich (Zurich), 11.09.1992–13.12.1992, Stuttgart 1992.

- Tobias G. Natter, Elisabeth Leopold (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Sammlung im Leopold Museum, Vienna 2013.

- Marian Bisanz-Prakken (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Ausst.-Kat., Albertina (Vienna), 14.03.2012–10.06.2012; Getty Center (Los Angeles), 03.07.2012–23.09.2012, Munich 2012.

- N. N.: Das Walther-Denkmal in Bozen, in: Neuigkeits-Welt-Blatt, 17.09.1889, S. 4.

- Andrea Gottdang: Vom Spatenbräu ins Museum. Joseph Pembaur der Ältere im Porträt Gustav Klimts, in: Franz Gratl, Andreas Holzmann, Verena Gstir (Hg.): Stereo-Typen: gegen eine musikalische Mono-Kultur, Ausst.-Kat., Ferdinandeum (Innsbruck), 27.04.2018–28.10.2018, Innsbruck 2018, S. 62-71.

- Herbert Giese: Franz von Matsch – Leben und Werk. 1861–1942. Dissertation, Vienna 1976, S. 287-288.

- Kunstchronik. Wochenschrift für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, N.F., 5. Jg., Heft 31 (1894), S. 497.

- Deutsche Kunst- & Musik-Zeitung, 21. Jg., Nummer 8 (1894), S. 105.

- Brief von Gustav Klimt in Wien an Anton Kerner von Marilaun in Wien (01/16/1892). 151.277.05, .

- Brief von Gustav Klimt in Wien an Anton Kerner von Marilaun in Wien (23.12.1891). 151.277.02, .

- Brief von Gustav Klimt in Wien an Anton Kerner von Marilaun in Wien (12/24/1891). 151.277.03, .

- Brief von Gustav Klimt in Wien an Anton Kerner von Marilaun in Wien (24.12.1891). 151.277.04, .

- Brief von Gustav Klimt in Wien an Anton Kerner von Marilaun in Wien (11/25/1891). 151.277.01, .

Exhibition Activity

Invitation to the XIXth annual exhibition at the Künstlerhaus, 1890, Künstlerhaus Archive, Vienna

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Auditorium of the Old Burgtheater, 1888, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Starting on 17 November 1889, Gustav Klimt’s gouache Auditorium of the Old Burgtheater was on display together with Franz Matsch’s Interior of the Old Burgtheater for a first preview at the City of Vienna’s Historical Museum. Ten days earlier, the Neues Wiener Tagblatt had written about the works, with a special focus on an enumeration of those portrayed in the pictures.

19th Annual Exhibition of the Vienna Künstlerhaus

At the “XIX. Jahresausstellung des Künstlerhauses” [“19th Annual Exhibition of the Vienna Künstlerhaus”] (18 March – 8 May 1890), the gouache Auditorium of the Old Burgtheater (1888, Wien Museum) was presented for the first time in an official exhibition in the “Watercolors and Pastels” section.

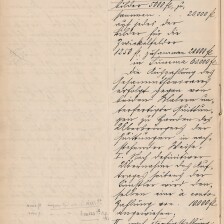

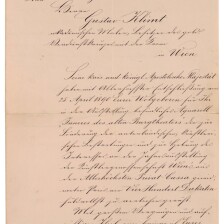

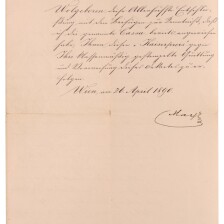

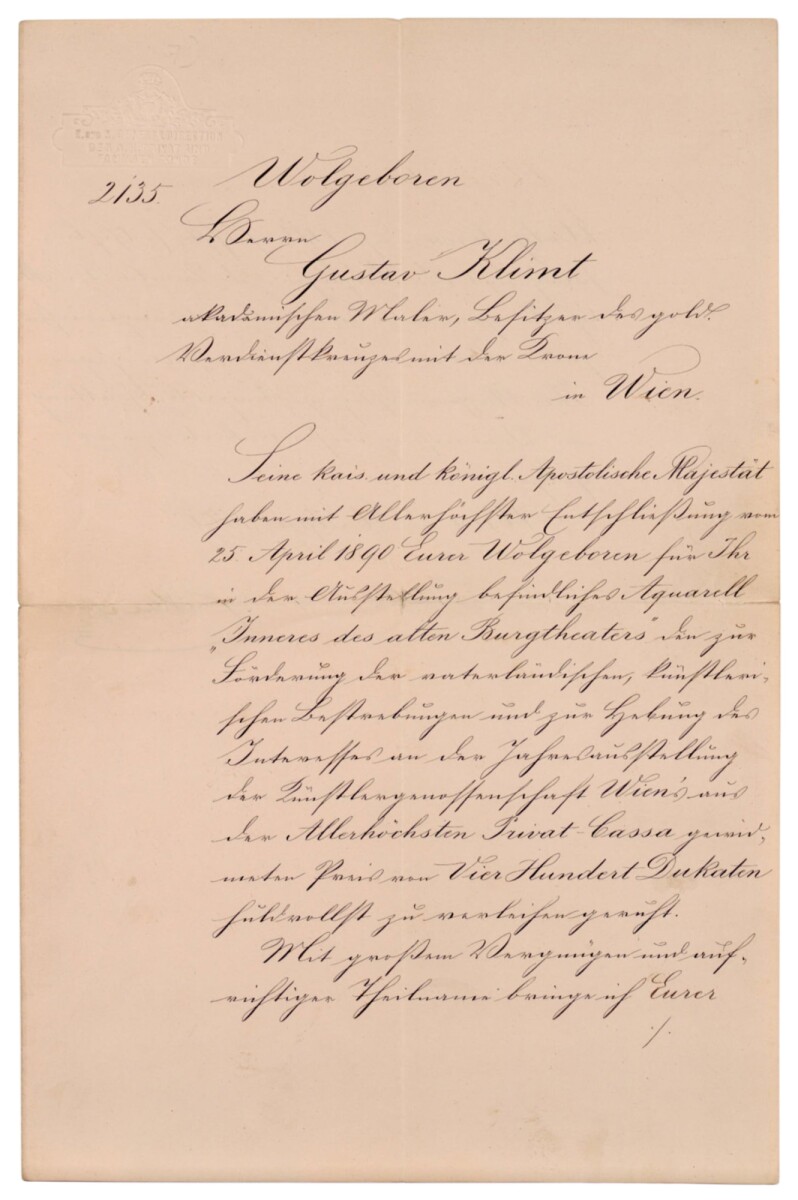

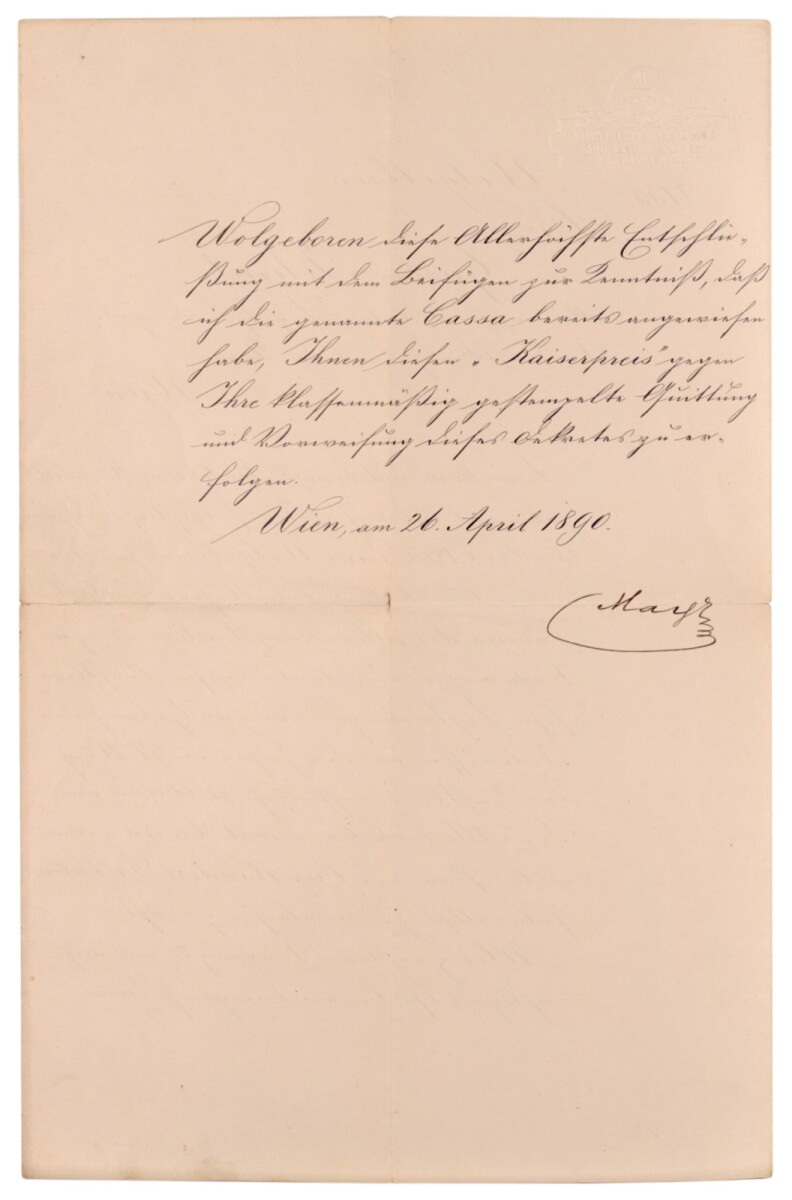

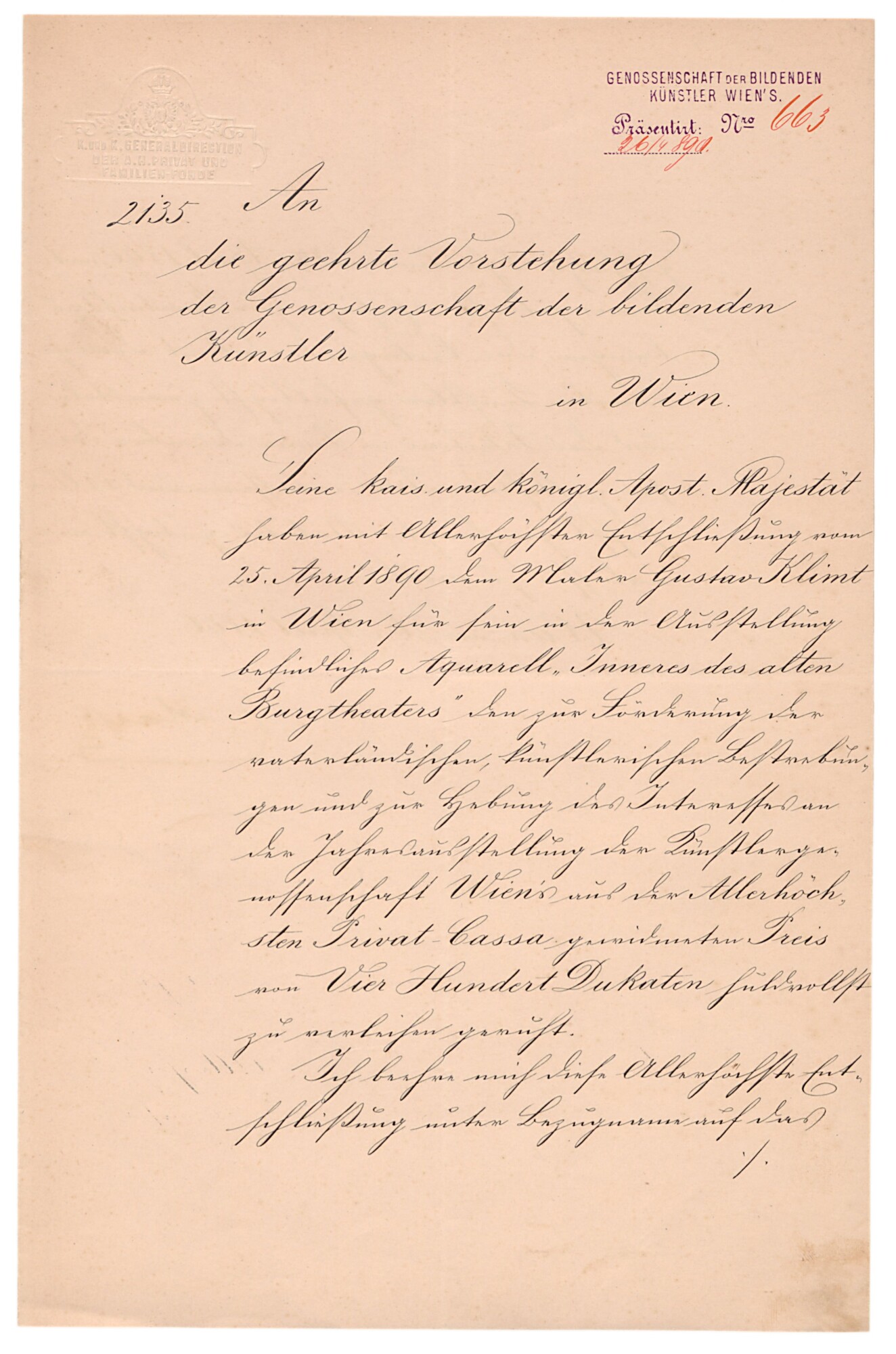

From the loan request to Mayor Johann Prix of 1 March 1890 we know that the Cooperative of Visual Artists in Vienna regarded Klimt’s gouache as one of the “most outstanding works” recently created in the visual arts. Emperor Francis Joseph I confirmed its appraisal by choosing Gustav Klimt as the first winner of the so-called Emperor’s Prize, which came with the amount of 400 ducats (approx. 50,000 euros). Klimt had prevailed over two competitors from the circle of exhibitors. There was praise for Klimt’s subtle observation and rare talent in artistic composition.

According to the statutes, the prize, which was paid from the emperor’s private purse, was to promote young and highly gifted artists. Both Austrian and Hungarian artists featured in the annual exhibition of the Vienna Künstlerhaus were admitted. The jury was made up of the award committee and the director of the Imperial Picture Gallery, Eduard Ritter von Engerth.

Award of the Emperor’s Prize and Letter of Congratulations

-

Letter from the Imperial and Royal Directorate General of the A. H. Privat und Familien-Fonde in Vienna to Gustav Klimt in Vienna, signed by Hofzahlmeister Mayr, 04/26/1890, The Albertina Museum

Letter from the Imperial and Royal Directorate General of the A. H. Privat und Familien-Fonde in Vienna to Gustav Klimt in Vienna, signed by Hofzahlmeister Mayr, 04/26/1890, The Albertina Museum

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna -

Letter from the Imperial and Royal Directorate General of the A. H. Privat und Familien-Fonde in Vienna to Gustav Klimt in Vienna, signed by Hofzahlmeister Mayr, 04/26/1890, The Albertina Museum

Letter from the Imperial and Royal Directorate General of the A. H. Privat und Familien-Fonde in Vienna to Gustav Klimt in Vienna, signed by Hofzahlmeister Mayr, 04/26/1890, The Albertina Museum

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna -

Letter from the k. und k. Generaldirection der A. H. Privat- und Familien-Fonde to the Genossenschaft der bildenden Künste Österreichs, signed by Hofzahlmeister Mayr, 04/26/1890, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien

Letter from the k. und k. Generaldirection der A. H. Privat- und Familien-Fonde to the Genossenschaft der bildenden Künste Österreichs, signed by Hofzahlmeister Mayr, 04/26/1890, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna -

Letter from the k. und k. Generaldirection der A. H. Privat- und Familien-Fonde to the Genossenschaft der bildenden Künste Österreichs, signed by Hofzahlmeister Mayr, 04/26/1890, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien

Letter from the k. und k. Generaldirection der A. H. Privat- und Familien-Fonde to the Genossenschaft der bildenden Künste Österreichs, signed by Hofzahlmeister Mayr, 04/26/1890, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna -

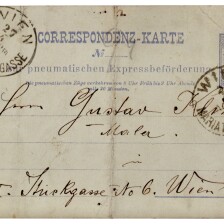

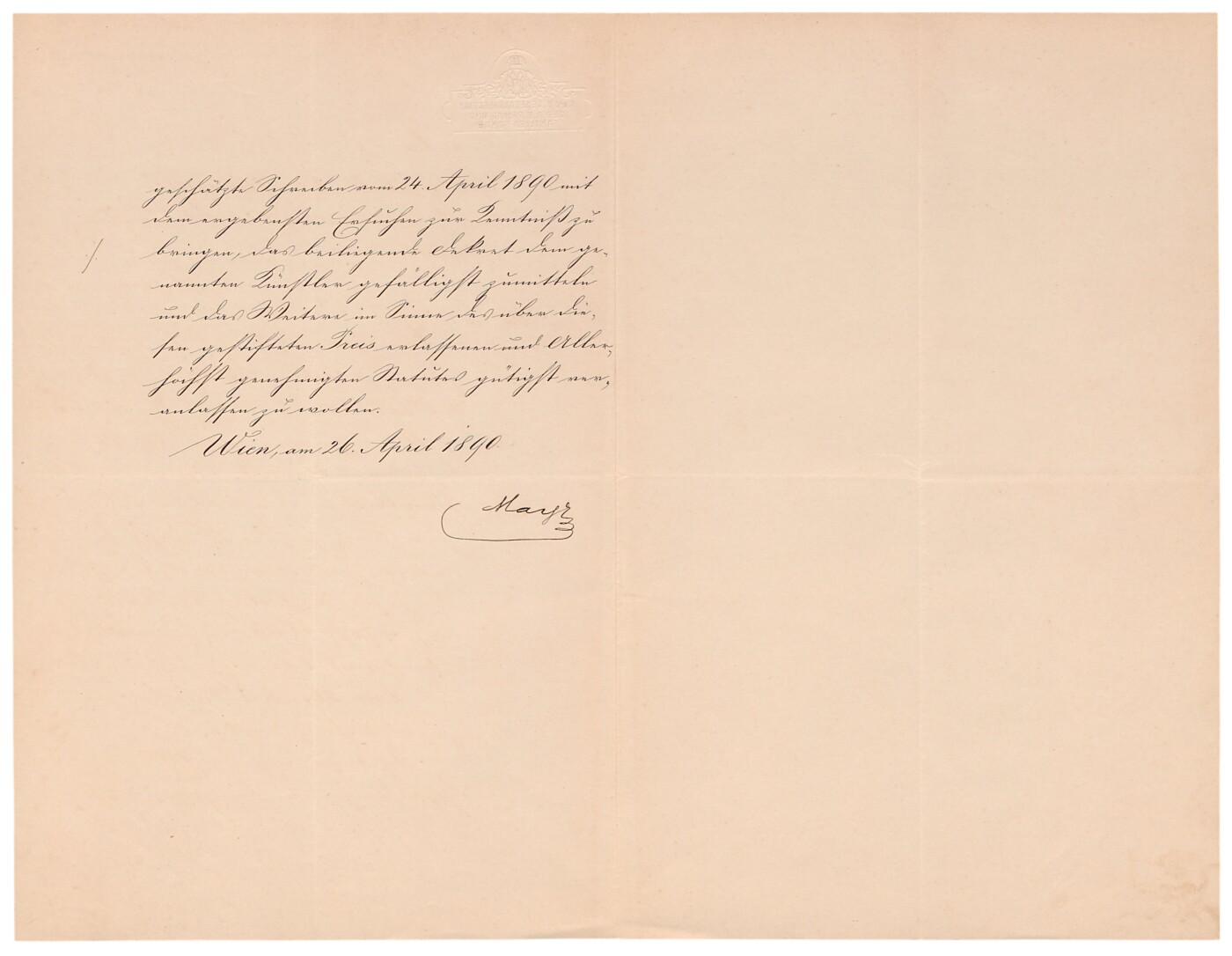

Eduard Veith: Correspondence Card from Eduard Veith in Vienna to Gustav Klimt in Vienna, 04/27/1890, The Albertina Museum

Eduard Veith: Correspondence Card from Eduard Veith in Vienna to Gustav Klimt in Vienna, 04/27/1890, The Albertina Museum

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna -

Eduard Veith: Correspondence Card from Eduard Veith in Vienna to Gustav Klimt in Vienna, 04/27/1890, The Albertina Museum

Eduard Veith: Correspondence Card from Eduard Veith in Vienna to Gustav Klimt in Vienna, 04/27/1890, The Albertina Museum

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Auditorium of the Theater of Esterházy Palace in Totis, 1893, Verbleib unbekannt

© Gallery Welz Salzburg

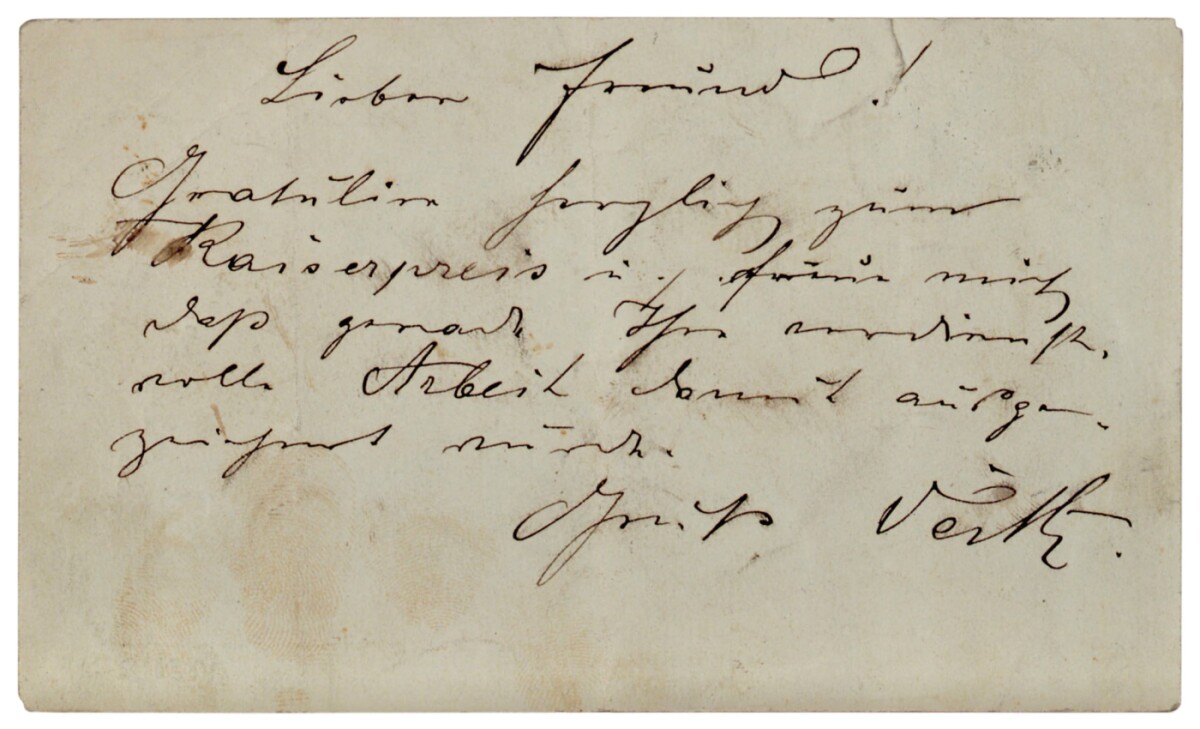

Poster of the World Exhibition in Antwerp, 1894

© gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

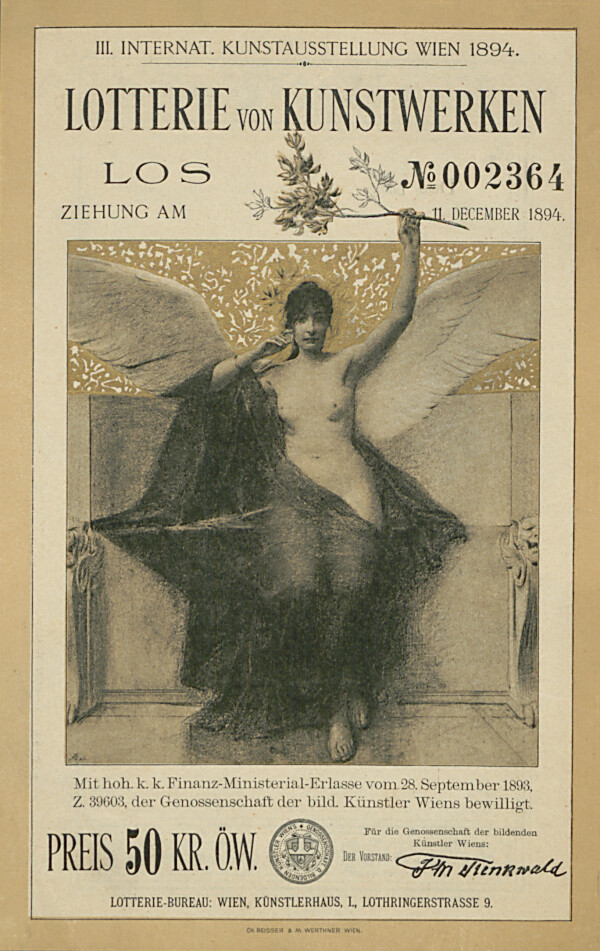

Eduard Veith: Lottery ticket for the III. International Art Exhibition at the Künstlerhaus, 1894, recto, Künstlerhaus Archive, Vienna

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna

It seems that the award had brought Klimt recognition in artistic circles, so that he felt sufficiently encouraged to apply for admission to the Cooperative of Visual Artists in Vienna at the beginning of March 1891. Klimt was admitted to the Cooperative as an ordinary member on 13 March.

22nd Annual Exhibition of the Vienna Künstlerhaus

It was probably because of the success of his Burgtheater picture that Klimt was commissioned by Count Esterházy in 1892 to capture the auditorium of his palace in Totis (now Tata) in a painting. In the course of the “XXII. Jahresausstellung des Künstlerhauses” [“22nd Annual Exhibition of the Vienna Künstlerhaus”] (28 March – 28 May 1893), the unfinished oil Auditorium of the Theater of Esterházy Palace in Totis (1893, unknown whereabouts), which incorporated 80 portraits of members of the audience, was awarded the silver state medal. The critics were beside themselves with praise:

“The most interesting work by far, and let us put it plainly, the best work (in the ‘Portraiture’ section) was brought by Gustav Klimt with his vibrant ‘Auditorium of the Theater in Totis.’”

The reviews particularly marveled at the detailed manner of painting, the virtuoso rendering of form and color, and the vibrancy of the groups of figures represented in the painting.

Traveling Exhibition in Antwerp

At the “Exposition Universelle des Beaux-Arts” (World’s Fair) in Antwerp (5 May – 12 November 1894), the painting was presented before an international audience. The Vienna Künstlerhaus contributed altogether 194 works to the show. The World’s Fair was the first presentation of Klimt’s paintings beyond Austria. In addition to Auditorium of the Theater of Esterházy Palace in Totis, Klimt presented a portrait from a private collection (cat. no. 2819) that can no longer be explicitly identified. In the context of the Antwerp exhibition, Klimt proved that his works could prevail on the international art scene. For his contribution, the jury awarded him one out of 22 certificates of honor in the discipline of painting, drawing, pastel, and watercolor. Only two other Austrians received what was the exhibition’s highest award: Vaeslav Brozik (painting) and Victor Tilgner (sculpture).

3rd International Art Exhibition

At the “III. Internationale Kunst-Ausstellung” [“3rd International Art Exhibition”] (6 March – 3 June 1894), Klimt could make a name for himself as an emerging Viennese artist. The show presented altogether 1,393 works of art grouped as to the exhibiting artists’ nationality. Klimt exhibited two portraits. One of the works, which in the first edition of the catalog was referred to as owned by “Franz Tran [!]” [Franz Trau], seems to have been his Portrait of Mathilde Trau (c. 1893, private collection). The painting was actually one of two pendants showing the couple Mr. and Mrs. Trau, who were tea merchants. According to Emil Pirchan, originally both portraits were meant to be shown. However, the hanging commission rejected the portrait of Franz Trau because of a lack of space. This was an early sign that Klimt mainly acquired a reputation as a painter of women, while male portraits proved quite rare in his oeuvre and met with much less public recognition. Newspaper articles also mentioned a “Portrait of a Lady in Black (three-quarter-length).” The only portrait fitting this description would be Portrait of a Woman (c. 1893/94, private collection). Together with Casimir Pochwalski and Eduard Angeli, Klimt thus headed the portraiture genre in this major international exhibition. Critic Rudolf Böck praised Klimt’s contribution as being “of greatest liveliness.”

Literature and sources

- Wiener Abendpost. Beilage zur Wiener Zeitung, 21.01.1889, S. 3-4.

- Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 07.11.1889, S. 1-2.

- Josef Langl: Die Jahresausstellung im Wiener Künstlerhause, in: Kunstchronik. Wochenschrift für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, N.F., 1. Jg., Heft 25 (1890), Spalte 393-400.

- Rudolf Böck: Die dritte Internationale Kunstausstellung in Wien. III, in: Kunstchronik. Wochenschrift für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, N.F., 5. Jg., Heft 31 (1894), Spalte 491–499.

- Rudolf Böck: Die dritte Jahresausstellung im Wiener Künstlerhause. II., in: Kunstchronik. Wochenschrift für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, N.F., 4. Jg., Heft 25 (1893), Spalte 398-404.

- Österreichische Kunst-Chronik, Nummer 10 (1890), S. 282.

- Brief der k. und k. Generaldirection der A. H. Privat und Familien-Fonde in Wien an Gustav Klimt in Wien, unterschrieben von Hofzahlmeister Mayr (26.04.1890). GKA71.

- Ehrendiplom für Gustav Klimt von der Weltausstellung in Antwerpen (July 1894). GKA83.

- Offizielle Broschüre der Jury der Weltausstellung in Antwerpen (1894). Mappe Antwerpen Weltausstellung A 1894, .

- Brief von Gustav Klimt in Wien an die Genossenschaft der bildenden Künstler Wiens, Aufnahmeansuchen (März 1891). Mappe Gustav Klimt, .

- Aufnahmeerklärung von Gustav Klimt in die Genossenschaft der bildenden Künstler Wiens (25.03.1891). Mappe Gustav Klimt, .

- Briefentwurf der Genossenschaft der bildenden Künstler Wiens an Johann Prix (03/01/1890). Mappe 19. Jahresausstellung_A_1890, .

- Österreichische Kunst-Chronik, Nummer 9 (1893), S. 6.

Drawings

Gustav Klimt: Egyptian art (transfer sketch), 1890/91, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Banknote "Fifty guilders" (design), 1892, Österreichische Nationalbank

© Oesterreichische Nationalbank

Gustav Klimt: Banknote "Ten guilders" (design), 1892, Österreichische Nationalbank

© Oesterreichische Nationalbank

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Emilie Flöge (Helene Klimt?), 1894, private collection

© Scala Florence

Between 1889 and 1894, Klimt created a series of watercolors, pastels, gouaches and drawings which can be regarded as complete and independent works. While Klimt would use the medium of drawing over the following years primarily for studies, many of his earlier graphic works are artworks in their own right.

Transfer Sketches

In 1890, the Klimt brothers and Franz Matsch were commissioned to create 40 spandrel paintings for the staircase of the Imperial-Royal Court Museum of Art History (now: Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna). In this context, they executed several black-chalk transfer sketches on paper gridded with pencil. All of these sketches were formulated with great attention to detail. Along with the positioning of the figures and the rough contours, the artists precisely predefined the fall of the folds of the clothing and the facial features. In Klimt’s later oeuvre, these meticulous preparatory works would be replaced by more schematic preliminary drawings.

50-Guilder Banknote for the National Bank

In early summer of 1892, the Austro-Hungarian Bank (now: Austrian National Bank, Vienna) asked Franz Matsch and Gustav Klimt to design banknotes. In the summer of that year, Klimt worked on drafts for a 10- and a 50-guilder banknote (Austrian National Bank, Money Museum). He placed the design for the 10-guilder bill into an antique context. The allegorical female depictions which Klimt positioned on both sides of the number panels also recall antique renderings. The personifications of commerce and economy are recognizable through their attributes, the scroll and caduceus. Klimt positioned the two women in a modern way sitting straight in front of the viewer, though they are looking away. Their expressions suggest indifference, if not absent transfiguration. The two figures convey a sense of cool rejection. The 50-guilder bill was meant to represent agriculture and science. Again, Klimt dramatized the depiction through contrasts, rendering the allegory of agriculture – a monumental female figure in antique dress in contrapposto turned away in a rotating movement – opposite a Pallas Athene – depicted from the front and wearing a Byzantine robe – in strict axial alignment.