Klimt's work focuses on all aspects of the Art Nouveau master's oeuvre. Visualized through a timeline, Klimt's creative periods are rolled up here, starting with his training, his collaboration with Franz Matsch and his brother Ernst in the "Künstler-Compagnie", the affair surrounding the faculty paintings and his post-fame and the myth that still surrounds this exceptional artist today.

Theater Painter in the Crown Lands and Vienna

It was at a rapid pace that Gustav Klimt and his colleagues executed decorations for theater buildings across the crown lands built by Fellner & Helmer. After the death of Hans Makart in 1884, the members of the “Künstler-Compagnie” ranked among the leading painters of their generation, and they received their first commission for the decoration of a public building on Vienna’s Ringstraße.

→

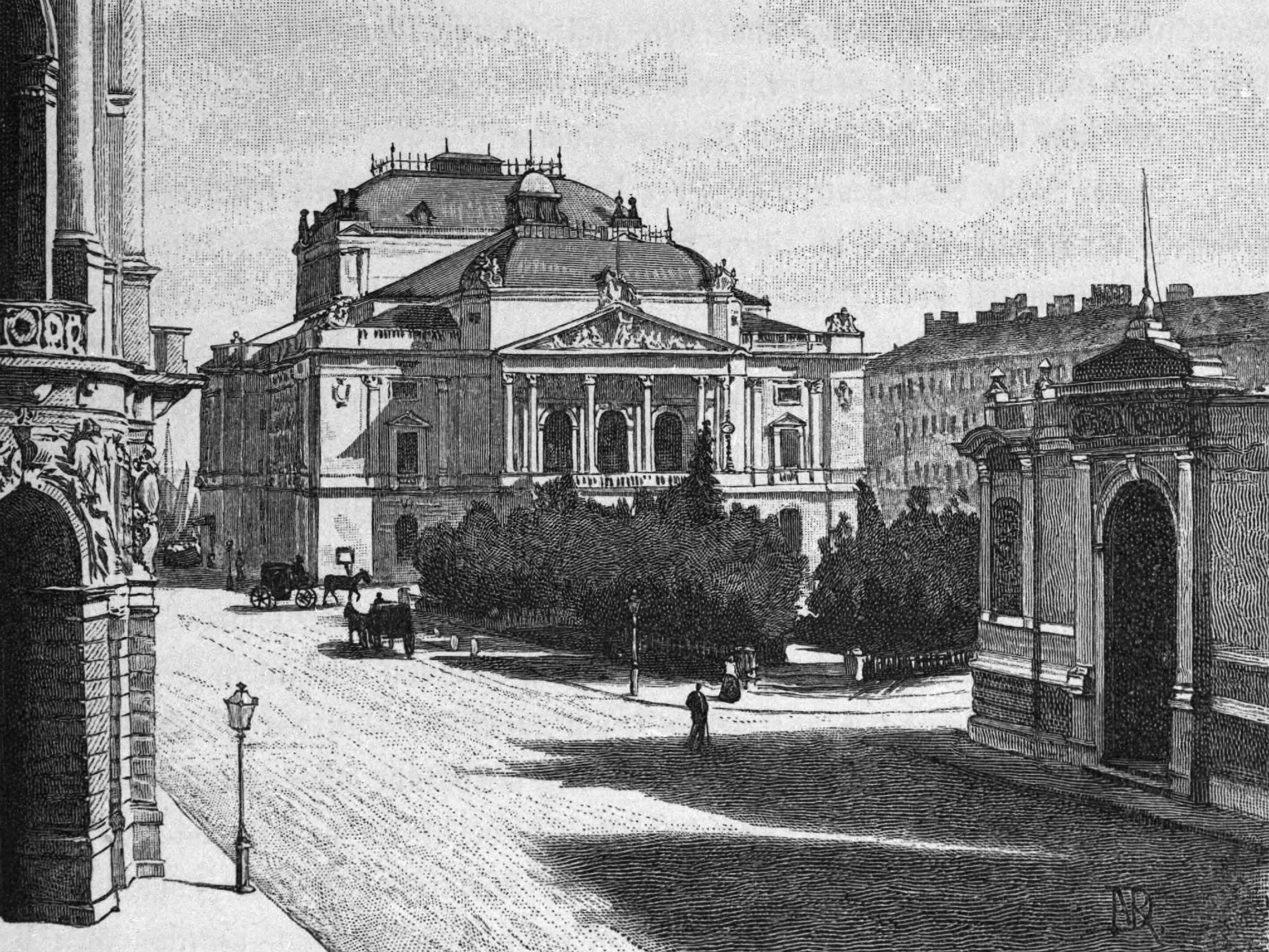

k. k. Hofburgtheater, circa 1885

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Stadttheater Reichenberg

In 1882/83, the “Künstler-Compagnie” executed its first autonomous large-scale commission: Five ceiling paintings and the stage curtain for the newly built municipal theater in Reichenberg. Franz Matsch and the Klimt brothers received the commission through the architectural office Fellner & Helmer, who were in charge of the theater’s construction.

To the chapter

→

Reichenberg Municipal Theater, in: Neue Illustrierte Zeitung, 04.06.1882.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

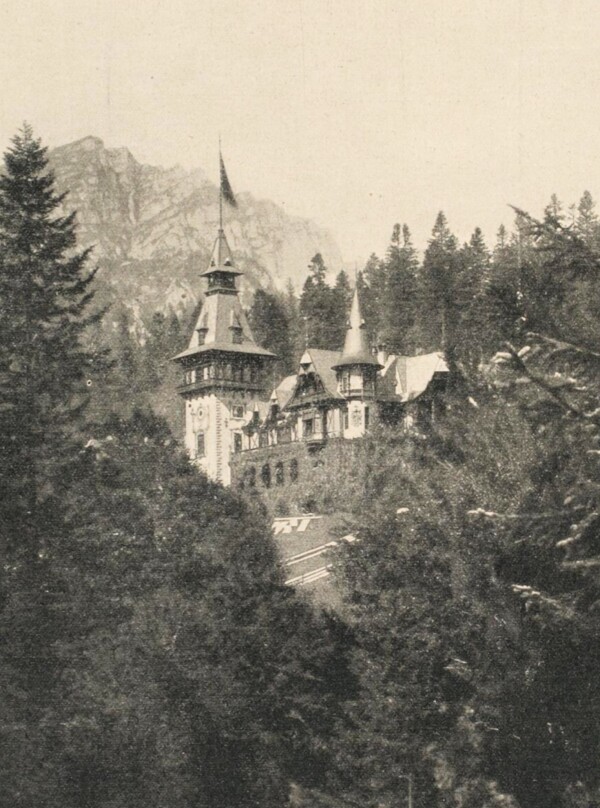

Peleș Castle

From 1883 to 1886, the “Künstler-Compagnie” worked on the decoration of Peleș Castle in Romania. This varied and challenging major commission included the creation of ten ancestral portraits, copies after Old Masters from the Imperial art collection as well as the decoration of the castle’s small theater.

To the chapter

→

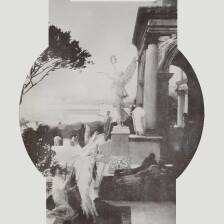

Pelesch Castle, around 1900

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

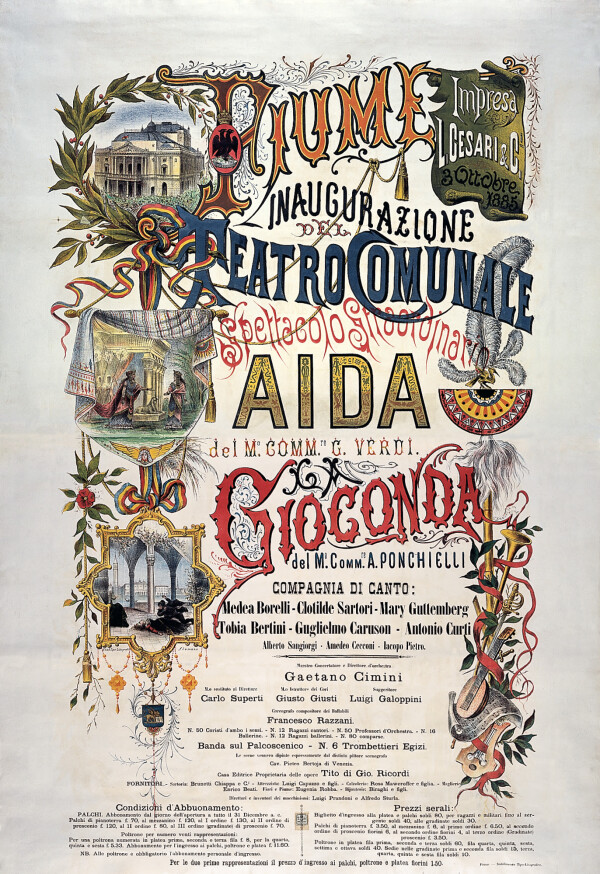

Stadttheater Fiume

In the mid-1880s, the “Künstler-Compagnie” received the commission to decorate the interior of the municipal theater in Fiume – yet another theater designed by Fellner & Helmer. The commission included six ceiling paintings, as well as a proscenium painting and two smaller paintings for the auditorium.

To the chapter

→

Fiume City Theater, in: Erzherzog Rudolf (Hg.): Die österreichisch-ungarische Monarchie in Wort und Bild, Band 12, Vienna 1893.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Hermesvilla

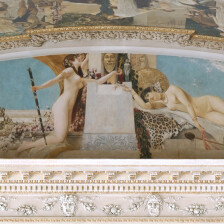

The “Künstler-Compagnie” decorated the cavetto of Empress Elisabeth’s bedroom in the Hermesvilla with scenes from William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and created a ceiling painting for the villa’s salon. They partly worked from drafts by their former teacher Julius Victor Berger, and partly after their own designs.

To the chapter

→

Hermesvilla in the Lainzer Tiergarten, an etching after a photograph by Josef Löwy

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Stadttheater Karlsbad

Franz Matsch and the Klimt brothers continued their successful partnership for the municipal theater in Karlsbad, which opened in 1886, creating four ceiling paintings, one proscenium painting and a stage curtain. The latter was temporarily displayed to the public at the Imperial-Royal Museum of Art and Industry in Vienna.

To the chapter

→

Carlsbad Municipal Theater

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Imperial-Royal Hofburgtheater

Between 1886 and 1888, the “Künstler-Compagnie” decorated the two prestigious staircases of the newly built Imperial-Royal Hofburgtheater with painterly scenes from theater history. It was the company’s first major independent commission in the residential city Vienna.

To the chapter

→

k. k. Hofburgtheater, in: V. A. Heck Verlag (Hg.): Das k. k. Hofburgtheater in Wien. erbaut von Carl Freiherrn von Hasenauer, Vienna 1890.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

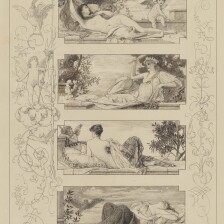

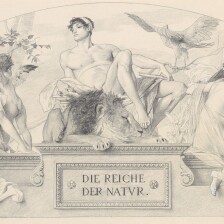

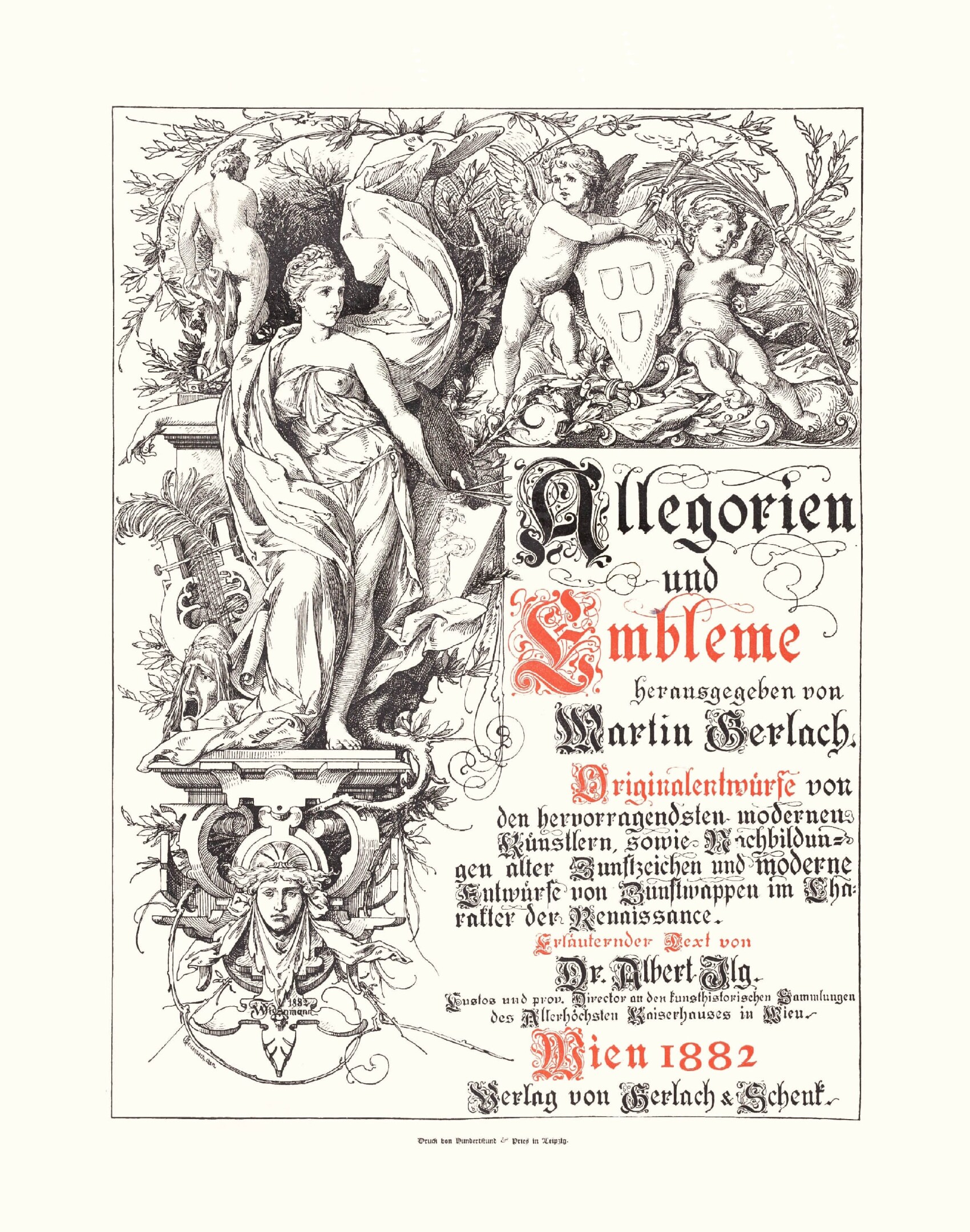

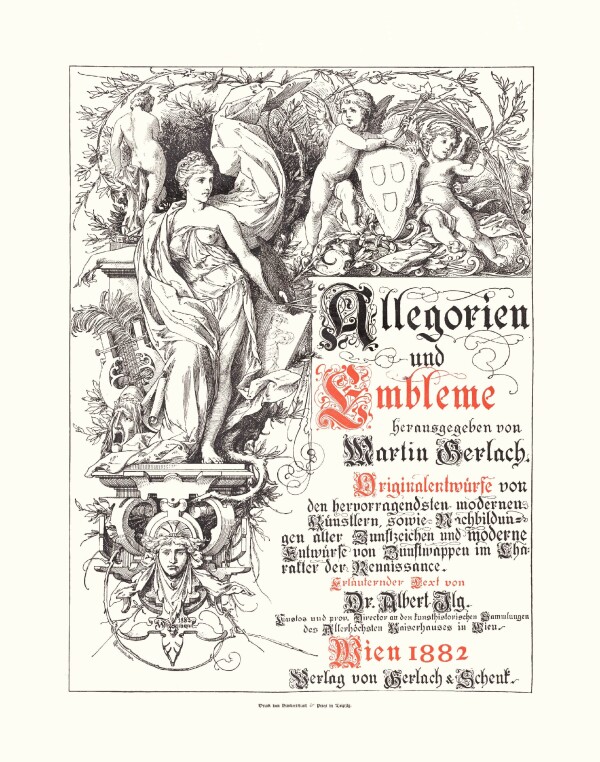

Allegories and Emblems

Starting in 1881, Gustav Klimt, commissioned by Martin Gerlach, worked on the sample collection Allegorien und Embleme [Allegories and Emblems]. He supplied designs for various allegories for this compilation of prints in the media of both drawing and oil painting.

To the chapter

→

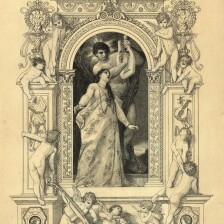

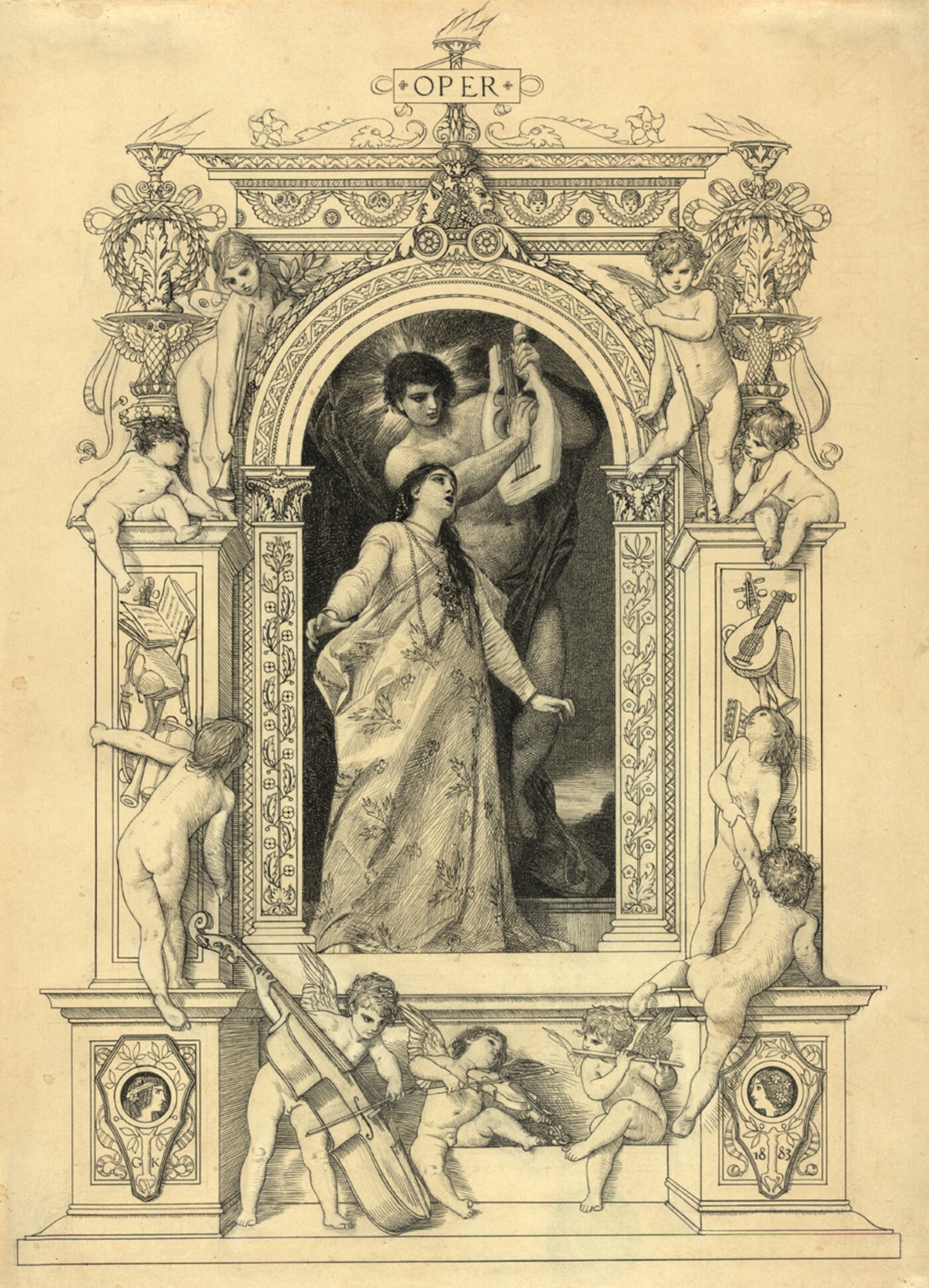

Front page, in: Martin Gerlach (Hg.): Allegorien und Embleme. Originalentwürfe von den hervorragendsten modernen Künstlern, sowie Nachbildungen alter Zunftzeichen und modernen Entwürfen von Zunftwappen im Charakter der Renaissance. Abtheilung I. Allegorien, Vienna 1882/84.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Drawings and Watercolors

The majority of drawings in Gustav Klimt’s early oeuvre were created as sketches and studies for decorative commissions. Only very few of these works on paper are considered autonomous artworks, among them the gouache Auditorium of the Old Burgtheater which Klimt created as a commission for the City of Vienna.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Auditorium of the Old Burgtheater, 1888, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

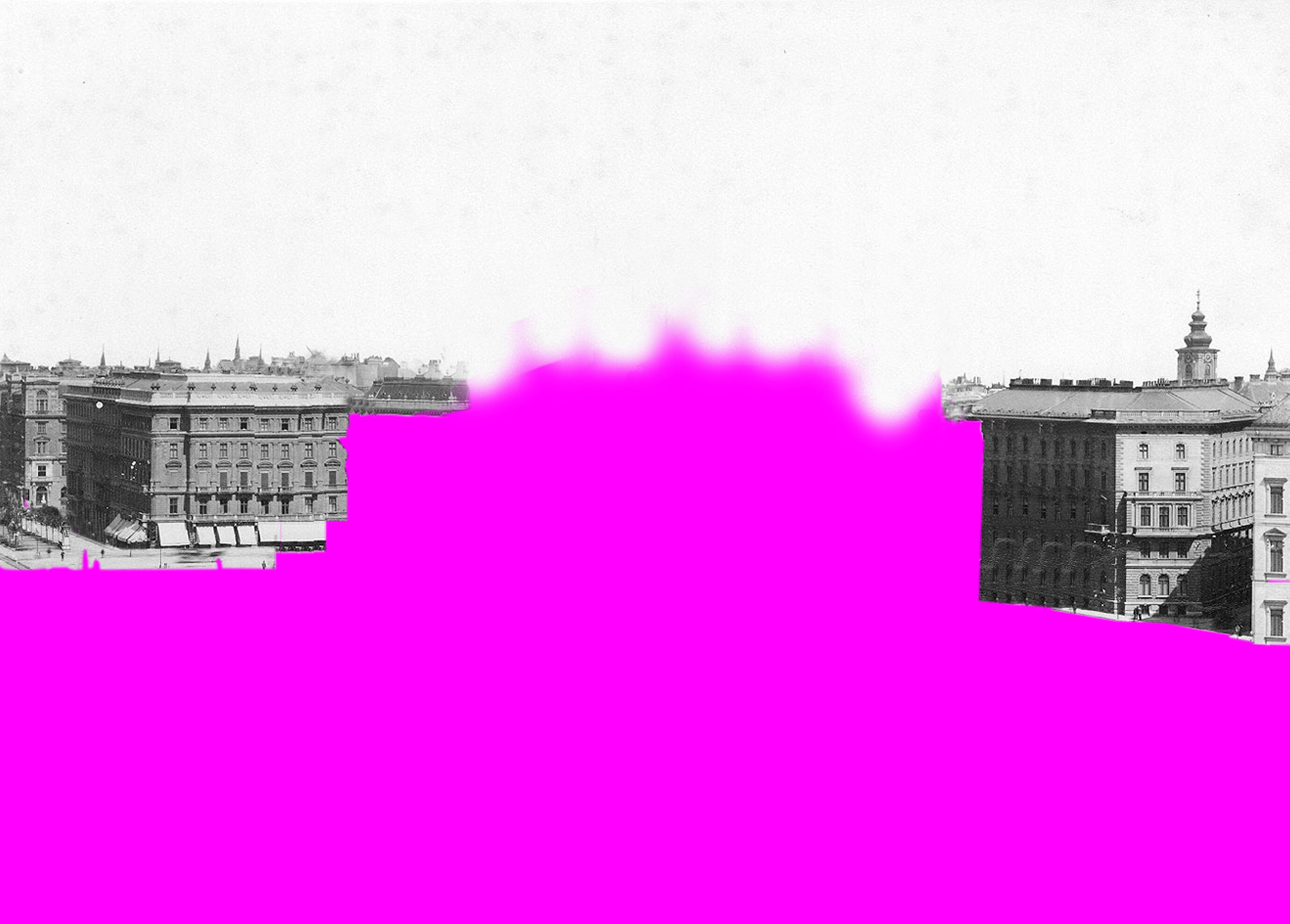

Theater Painter in the Crown Lands and Vienna

It was at a rapid pace that Gustav Klimt and his colleagues executed decorations for theater buildings across the crown lands built by Fellner & Helmer. After the death of Hans Makart in 1884, the members of the “Künstler-Compagnie” ranked among the leading painters of their generation, and they received their first commission for the decoration of a public building on Vienna’s Ringstraße.

→

k. k. Hofburgtheater, circa 1885

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Stadttheater Reichenberg

Reichenberg Municipal Theater, in: Neue Illustrierte Zeitung, 04.06.1882.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

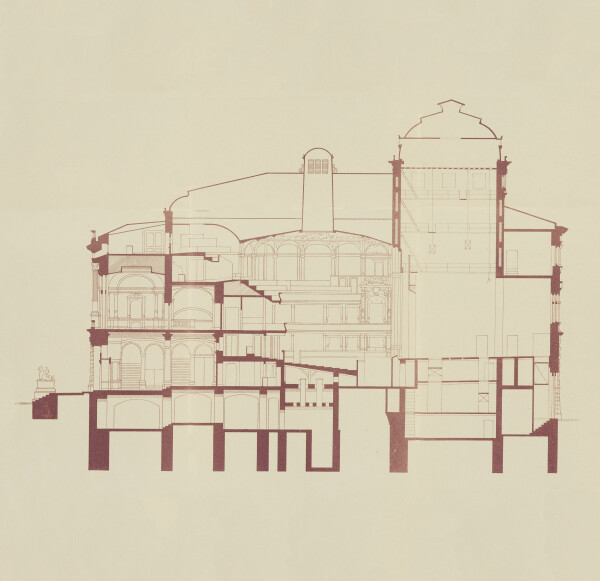

Reichenberg Municipal Theater (elevation)

© Architekturmuseum (TU Berlin)

Gustav Klimt, Ernst Klimt, Franz Matsch: Design for the Main Curtain of Liberec City Theater, 1882, Verein der Freunde der Österreichischen Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

In 1882/83, the “Künstler-Compagnie” executed its first autonomous large-scale commission: Five ceiling paintings and the stage curtain for the newly built municipal theater in Reichenberg. Franz Matsch and the Klimt brothers received the commission through the architectural office Fellner & Helmer, who were in charge of the theater’s construction.

In June 1881, the city of Reichenberg (now Liberec, Czech Republic) entered into a contract with the two famous Viennese architects Ferdinand Fellner Jr. and Hermann Helmer, commissioning them to erect a new municipal theater (now F. X. Šalda-Theater), which was to open as early as the autumn of 1883. According to the newspaper Die Presse, dated 23 June 1881, Fellner & Helmer were asked to submit their detailed plans and cost estimate by the end of August, as the city intended for construction to start in the autumn. Various media reports indicate that the requested documents were submitted to the municipality in early September. Fellner & Helmer personally presented the plans for the theater, which they designed as a free-standing building, to the city council in Reichenberg. The newspaper Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung reported on 8 September 1881 that “the city councilors announced the construction of the new theater according to the architects’ much-lauded plans […].” The budget for the building project, which was to last several years, was set for 230,000 guilders (c. 3,234,000 euros), but, in the end, exceeded the sum of 300,000 guilders (c. 4,219,000 euros).

The dedicated master builders from Reichenberg, Sachers and Gärtner, began construction work in 1881. Together with the Viennese architectural office, they completed the building on schedule in 1883. The inauguration ceremony was held on 29 September 1883. According to the Prague newspaper Prager Tagblatt, it was attended by Fellner & Helmer, who were “honored by the audience in a highly complementary manner.”

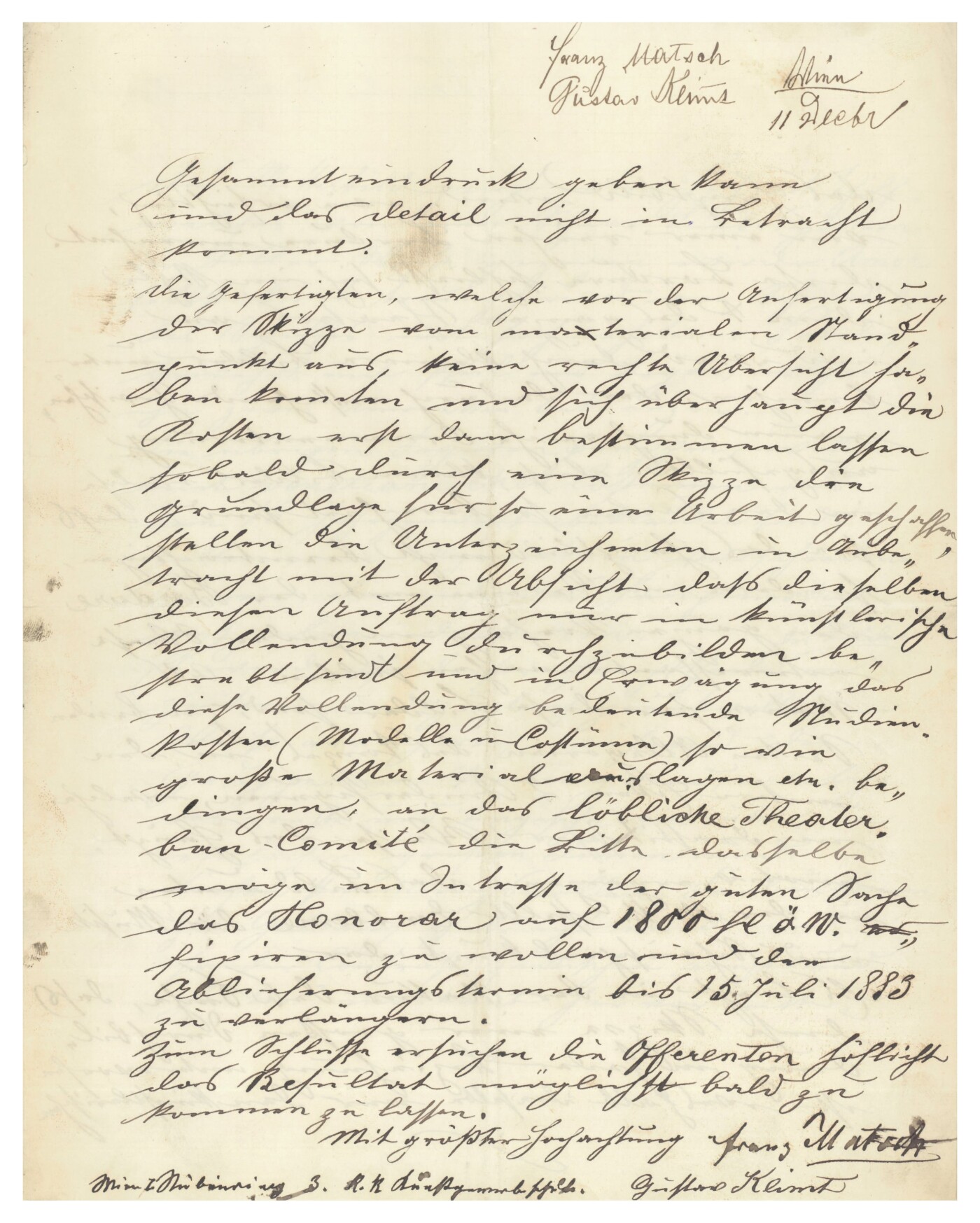

Commissioning of the “Künstler-Compagnie”

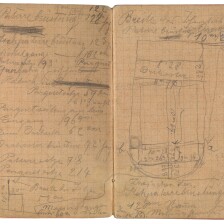

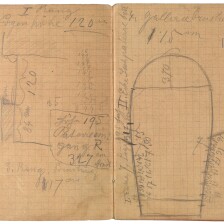

In the autumn of 1882, Franz Matsch and Gustav Klimt – likely at the recommendation of Fellner & Helmer – received a request from Reichenberg to create a sketch for the municipal theater’s main stage curtain. In the two young artists’ extant reply – written on stationary from the architectural office Fellner & Helmer and dated 10 October 1882 – they accepted the request, and promised to send a draft by early December. Should their design be accepted, they initially set the price for its realization at 1,500 guilders (c. 21,260 euros), and later at 1,800 guilders.

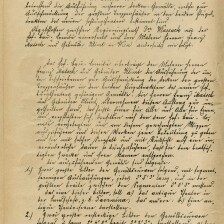

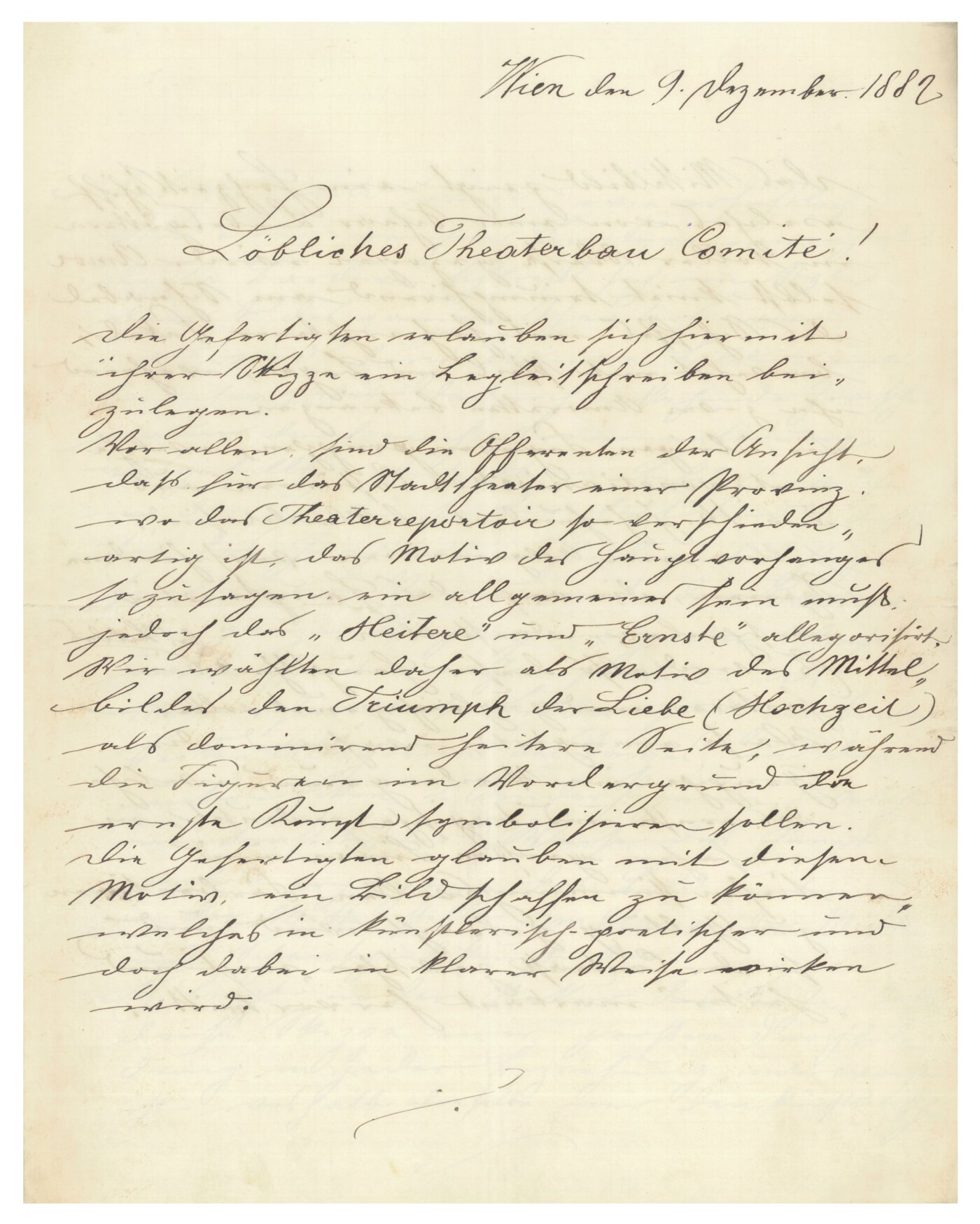

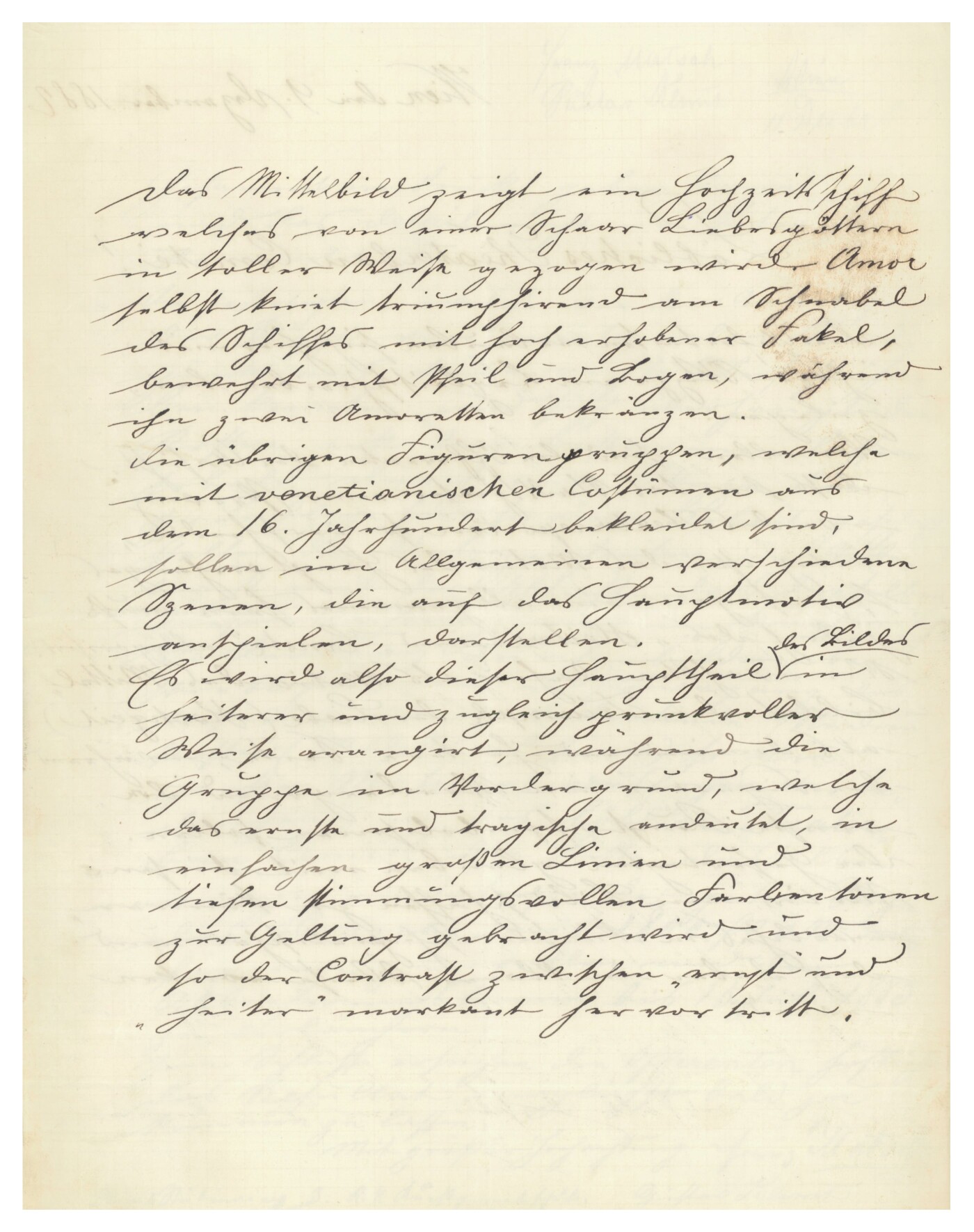

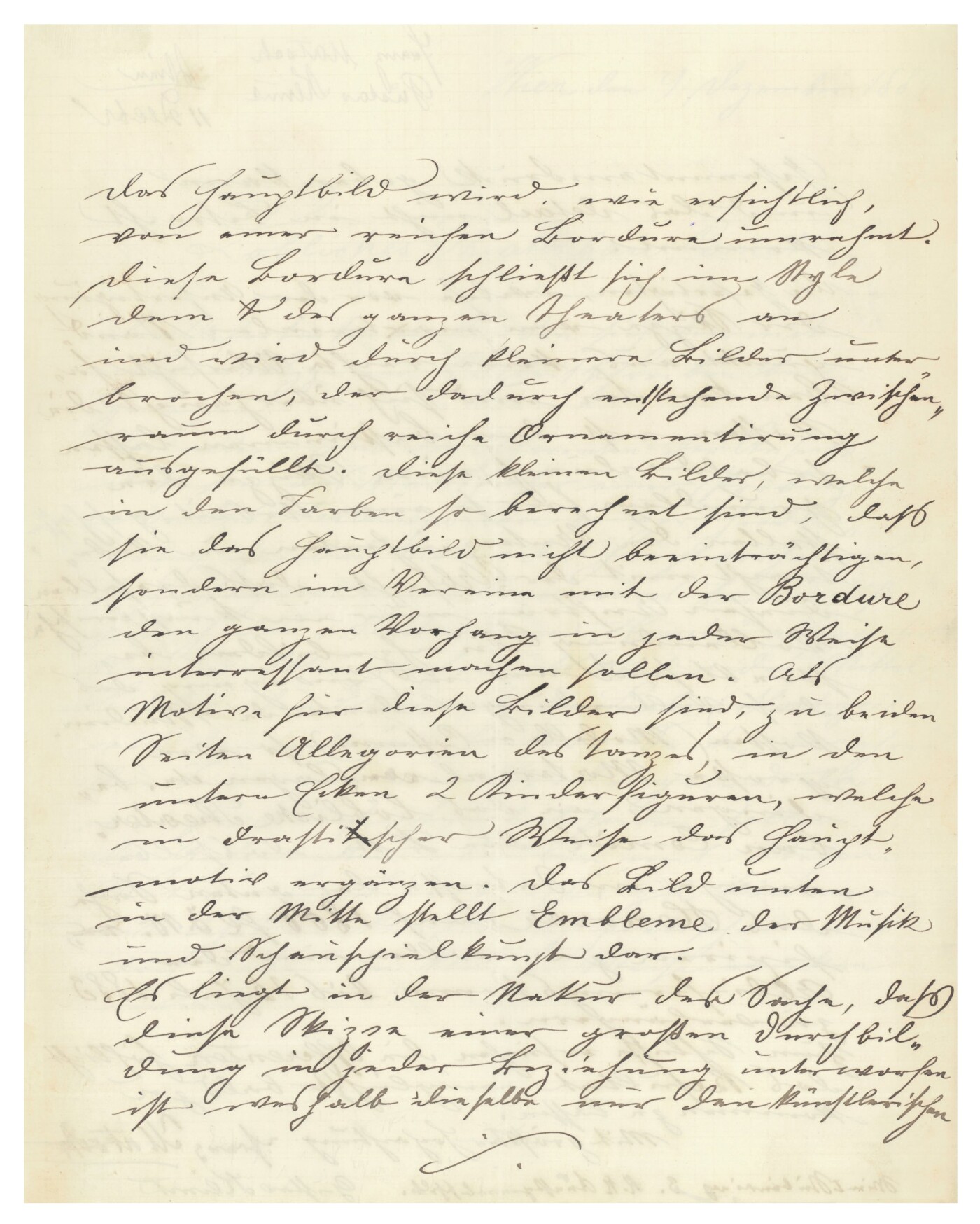

According to the correspondence kept at the State District Archive Liberec (SOkA Liberec), the sketch was delivered nearly on schedule in December 1882 to the theater construction committee, along with a detailed program description:

“The offerers believe that, for the municipal theater of a province, whose repertoire has to be especially varied, the motif of the main stage curtain should be a general one; one that allegorizes both the ‘merry’ and the ‘solemn.’ […] We thus chose the triumph of love (marriage) as the motif for our central depiction to express the merry aspect, while the figures in the foreground are meant to symbolize solemn art […].”

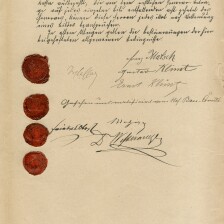

Letter from Franz Matsch in Vienna to the Theater Construction Committee in Reichenberg, Co-Signed by Gustav Klimt

-

Franz Matsch: Letter from Franz Matsch in Vienna to the Theater Construction Committee in Reichenberg, co-signed by Gustav Klimt, 12/09/1882, SOkA Liberec, Archiv města Liberec (AML)

Franz Matsch: Letter from Franz Matsch in Vienna to the Theater Construction Committee in Reichenberg, co-signed by Gustav Klimt, 12/09/1882, SOkA Liberec, Archiv města Liberec (AML)

© SOkA Liberec, Archiv města Liberec (AML) -

Franz Matsch: Letter from Franz Matsch in Vienna to the Theater Construction Committee in Reichenberg, co-signed by Gustav Klimt, 12/09/1882, SOkA Liberec, Archiv města Liberec (AML)

Franz Matsch: Letter from Franz Matsch in Vienna to the Theater Construction Committee in Reichenberg, co-signed by Gustav Klimt, 12/09/1882, SOkA Liberec, Archiv města Liberec (AML)

© SOkA Liberec, Archiv města Liberec (AML) -

Franz Matsch: Letter from Franz Matsch in Vienna to the Theater Construction Committee in Reichenberg, co-signed by Gustav Klimt, 12/09/1882, SOkA Liberec, Archiv města Liberec (AML)

Franz Matsch: Letter from Franz Matsch in Vienna to the Theater Construction Committee in Reichenberg, co-signed by Gustav Klimt, 12/09/1882, SOkA Liberec, Archiv města Liberec (AML)

© SOkA Liberec, Archiv města Liberec (AML) -

Franz Matsch: Letter from Franz Matsch in Vienna to the Theater Construction Committee in Reichenberg, co-signed by Gustav Klimt, 12/09/1882, SOkA Liberec, Archiv města Liberec (AML)

Franz Matsch: Letter from Franz Matsch in Vienna to the Theater Construction Committee in Reichenberg, co-signed by Gustav Klimt, 12/09/1882, SOkA Liberec, Archiv města Liberec (AML)

© SOkA Liberec, Archiv města Liberec (AML)

Franz Matsch sen.: Hermine and Klara Klimt, around 1882

© Belvedere, Vienna

In January 1883, the committee in charge decided to commission the Viennese artists with the execution of the theater curtain sketch, which was deemed “very beautiful and artistic.” The delivery of the finished curtain Allegory of Merry and Solemn Art (1882/83) was scheduled for 15 July 1883.

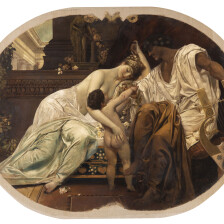

The signature, placed in the central depiction, reveals that Franz Matsch as well as Gustav and Ernst Klimt worked on the stage curtain together. It has thus far been difficult to distinguish exactly which artist worked on which part. Owing to a sketch, it is believed that Gustav Klimt painted the standing male figure in the middle of the wedding ship. The group of figures gathered at the stern of the ship, too, is ascribed to the elder Klimt brother. The two female figures next to the group were most likely painted by Matsch. They form part of the wedding party and are reminiscent in their composition of a portrait created by Matsch of the sisters Hermine and Klara Klimt (c. 1882, private collection).

Gustav Klimt, Ernst Klimt, Franz Matsch: Allegory of Merry and Solemn Art, 1882/83, F. X. Šalda-Theater

© Divadlo F. X. Šaldy

Decoration in Reichenberg

-

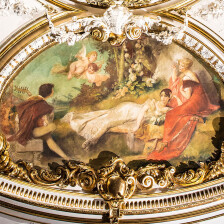

Gustav Klimt: Lute Music, 1882/83, F. X. Šalda-Theater

Gustav Klimt: Lute Music, 1882/83, F. X. Šalda-Theater

© Divadlo F. X. Šaldy -

Franz Matsch: Recitation | 1882/83, undated, F. X. Šalda-Theater

Franz Matsch: Recitation | 1882/83, undated, F. X. Šalda-Theater

© Divadlo F. X. Šaldy -

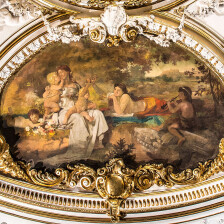

Franz Matsch: Young woman with playing children | 1882/83, undated, F. X. Šalda-Theater

Franz Matsch: Young woman with playing children | 1882/83, undated, F. X. Šalda-Theater

© Divadlo F. X. Šaldy -

Gustav Klimt: Family with Child Playing the Drums, 1882/83, F. X. Šalda-Theater

Gustav Klimt: Family with Child Playing the Drums, 1882/83, F. X. Šalda-Theater

© Divadlo F. X. Šaldy -

Ernst Klimt: Allegory of the Arts | 1882/83, undated, F. X. Šalda-Theater

Ernst Klimt: Allegory of the Arts | 1882/83, undated, F. X. Šalda-Theater

© Divadlo F. X. Šaldy

Ceiling ensemble in the Reichenberg Municipal Theater

© Divadlo F. X. Šaldy

Ceiling Paintings

Along with the curtain, the three artists created four large ceiling paintings, as well as a proscenium painting for the auditorium. The latter was realized by Ernst Klimt, while Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch created two works each for the ceiling. Owing to the marginal source situation, the precise circumstances surrounding the commission of these five works for Reichenberg have not yet been fully ascertained. A report from the Mittheilungen des k. k. Oesterreichischen Museums [Communications from the Imperial-Royal Austrian Museum of Art and Industry], dated 1 February 1883, merely states that the city council of Reichenberg approved the sketches designed by the Viennese painters Franz Matsch and the brothers Gustav and Ernst Klimt for the curtain and five ceiling paintings for the newly built municipal theater. The works could have been directly commissioned from Fellner & Helmer, though.

Presentation at the Imperial-Royal Austrian Museum of Art and Industry

Both the five ceiling paintings as well as the main stage curtain for Reichenberg were presented to the public for a few days at the Imperial-Royal Austrian Museum of Art and Industry (now MAK, Vienna). This was done at the initiative of the museum’s director Rudolf Eitelberger, among others. According to the Mittheilungen des k. k. Oesterreichischen Museums, the two exhibitions were shown from 16 to 19 March 1883 and from 1 to 2 September 1883. The very short duration of the presentations was due to the artists’ obligation to deliver the works.

Literature and sources

- Hana Seifertová-Korecká: Ein Frühwerk von Gustav Klimt – Der Theatervorhang in Reichenberg (Liberec), in: Alte und moderne Kunst. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Kunst, Kunsthandwerk und Wohnkultur, 12. Jg., Heft 94 (1967), S. 23-28.

- Mittheilungen des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie. Monatsschrift für Kunst und Gewerbe, 18. Jg., Heft 209 (1883), S. 335.

- Mittheilungen des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie. Monatsschrift für Kunst und Gewerbe, 19. Jg., Heft 220 (1884), S. 14-15.

- Mittheilungen des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie. Monatsschrift für Kunst und Gewerbe, 18. Jg., Heft 217 (1883), S. 526.

- Mittheilungen des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie. Monatsschrift für Kunst und Gewerbe, 18. Jg., Heft 211 (1883), S. 378.

- Die Presse, 23.06.1881, S. 11.

- Neue Illustrierte Zeitung, 04.06.1882, S. 570.

- Der Bautechniker. Centralorgan für das österreichische Bauwesen, 1. Jg., Nummer 36 (1881), S. 291.

- Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, 08.09.1881, S. 5.

- Herbert Giese: Franz von Matsch – Leben und Werk. 1861–1942. Dissertation, Vienna 1976, S. 42-47.

- Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien (Hg.): Franz von Matsch. Ein Wiener Maler der Jahrhundertwende, Ausst.-Kat., Museums of the City of Vienna (Vienna), 12.11.1981–31.01.1982, Vienna 1981, S. 45-48.

- Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, 08.11.1881, S. 3.

- Neue Freie Presse, 01.10.1883, S. 1.

- Teplitz-Schönauer Anzeiger, 03.10.1883, S. 5.

- Prager Tagblatt, 30.09.1883, S. 4.

- Brief von Franz Matsch in Wien an das Theaterbaucomité in Reichenberg, mitunterschrieben von Gustav Klimt (09.12.1882). VI. – Gd, 202, Signatur 709/4, Karton 188_2, .

- Brief von Franz Matsch in Wien an Carl Finke in Reichenberg, mitunterschrieben von Gustav Klimt (10/10/1882). VI. – Gd, 202, Signatur 709/4, Karton 188_1, .

- Brief von Franz Matsch in Wien an den Magistrat der Stadt Reichenberg, mitunterschrieben von Gustav Klimt (01/19/1883). VI. – Gd, 202, Signatur 709/4, Karton 188_9, .

- Brief von Franz Matsch in Wien an den Magistrat der Stadt Reichenberg, mitunterschrieben von Gustav und Ernst Klimt (vor dem 14.08.1883). VI. – Gd, 202, Signatur 709/4, Karton 188_6, .

- N. N.: Atelier Klimt und Matsch, in: Mittheilungen des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie. Monatsschrift für Kunst und Gewerbe, 20. Jg., Heft 232 (1885), S. 308.

- Die Graphischen Künste, 35. Jg. (1912), S. 51.

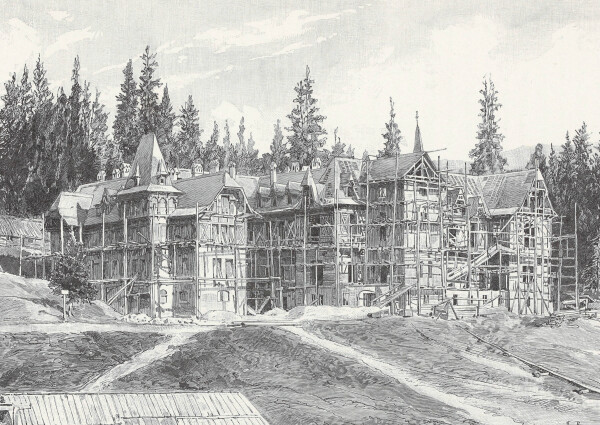

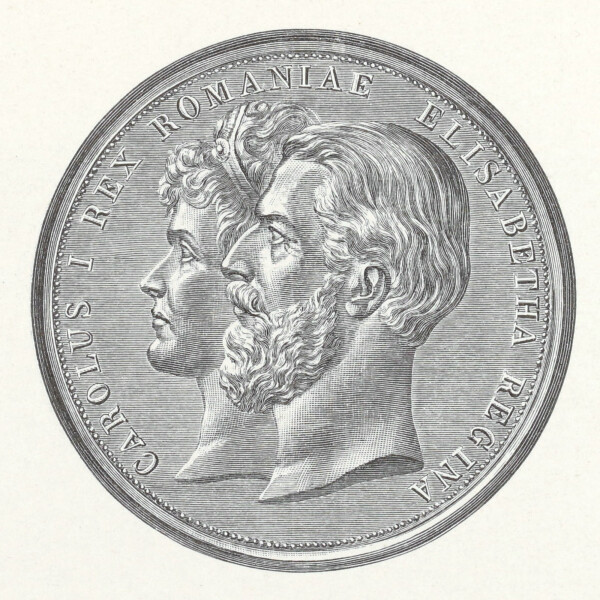

Peleș Castle

Pelesch Castle, around 1900

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Construction of Pelesch Castle, in: Jacob von Falke: Das rumänische Königsschloss Pelesch, Vienna 1893.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Obverse of a medal created by Wilhelm Kullrich on the occasion of the completion of Pelesch Castle, 1883, in: Jacob von Falke: Das rumänische Königsschloss Pelesch, Vienna 1893.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

From 1883 to 1886, the “Künstler-Compagnie” worked on the decoration of Peleș Castle in Romania. This varied and challenging major commission included the creation of ten ancestral portraits, copies after Old Masters from the Imperial art collection as well as the decoration of the castle’s small theater.

In 1873, King Carol I of Romania commissioned a summer residence to be built near the small town of Sinaia. The first plans for Peleș Castle (German: Schloss Pelesch) were created by the Viennese architect Wilhelm von Doderer. His assistant, Johannes Schulz, and the German interior designer and sculptor Martin Stöhr were in charge of the final planning and construction management. The construction of the palace took an entire decade – not least on account of armed conflicts which coincided with this period – while further structural adaptations were carried out later during a second construction phase.

The inauguration of the royal palace, built in the German neo-Renaissance style, took place on 7 October 1883. The newspaper Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung reported on this occasion a few days later:

“King Carol I of Romania built a wonderful summer residence, situated in a scenic spot in the Carpathian Mountains, which he has called ‘Pelesch.’ […] Following the inaugural church ceremony, General Creteanu read out the construction certificate, which was then signed by the King and Queen, and subsequently by all the guests. Hereupon, the King opened the door to the castle, and gave the Queen and all the guests a tour of its rooms.”

By the time of the inauguration, the interior design and artistic decorations were largely completed. For the “Künstler-Compagnie,” however, work for Peleș Castles would continue until 1886

Nibelung Sgraffiti

Just who recommended the artists of the “Künstler-Compagnie” to the building contractors at the time has not yet been ascertained. Most likely, the artists received the commission via the Vienna-based company of Joseph Kott, which was tasked with the castle’s decor. Acting as Kott’s subcontractors, the three young artists created cartoons – according to Franz Matsch there were nine – for sgraffiti in the inner courtyard, showing depictions from the Legend of the Nibelung. Seeing as this inner courtyard was roofed around 1900, and later converted, the sgraffiti are now lost.

Copies after Old Masters

The “Künstler-Compagnie” also created copies of select works from the Imperial art collection in Vienna for the Sinaia commission. Ernst Klimt and Franz Matsch executed five detailed copies after Rembrandt, Velásquez and van Dyck. Gustav Klimt reproduced Titian’s idealized portrait of Isabella d’Este (c. 1534/1536, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), masterfully imitating the work’s material quality. To this end, he signed the copyists’ register of the Imperial-Royal Court Museum of Art History (now Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) in April and June 1885.

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Isabella d'Este, 1885, Muzeul Național Peleș

© Muzeul Național Peleș

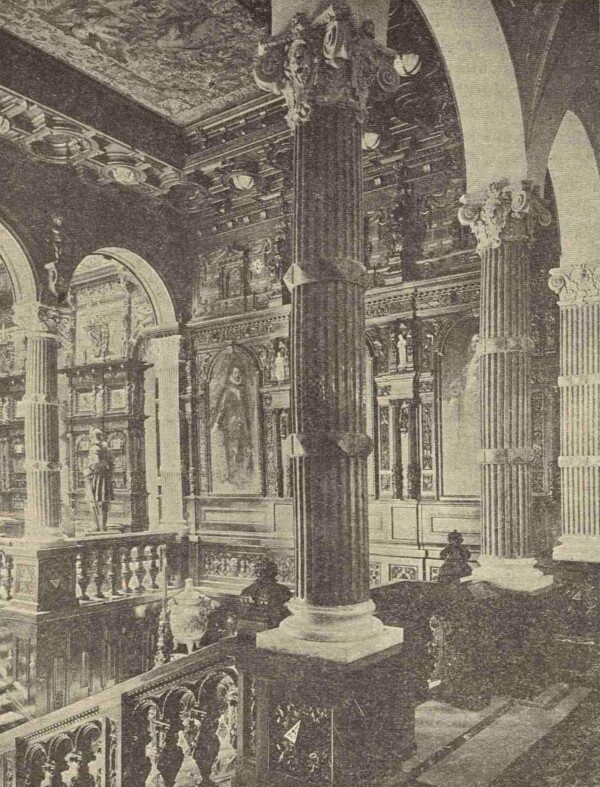

Insight into the ceremonial hall of Pelesch Castle, circa 1924, in: Mihai Haret: Castelul Peleş, Bucharest 1924.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

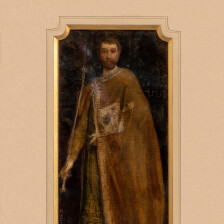

Ancestral Hall

Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch were further tasked with executing five life-sized representational portraits each for the large ceremonial hall and the corresponding staircase at the summer residence, some of which were set into richly decorated wood paneling. The ceiling painting Science and Art (c. 1883–1885), painted by Ernst Klimt, completed the ensemble of paintings in these rooms.

The portrait-format paintings depicted ancestors of the Romanian King – all of them members of the Zollern and Hohenzollern-Hechingen families. Franz Matsch recalled in his autobiography that the monarch had sent the artists a book from the 16th century to use as a template, but since at least two of the ancestors painted by Gustav Klimt lived in the 17th century, it cannot have been their only source.

Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch created small-scale preliminary color drafts for the ten portraits, which are now kept at the National History Museum in Bucharest. Worth mentioning in this context are two photographs from what is known as the “Klimt-Chronik” (Klimt-Foundation, Vienna). These were possibly taken by the young artists themselves, and afford interesting insights into the studio of the “Künstler-Compagnie” on Sandwirtgasse around 1883/84. Discernible in the background of both photographs are the drafts for the ancestral portraits.

Gustav Klimt’s Artworks for Peleș Castle

-

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Philipp Friedrich Christoph, Count of Hohenzollern (Study), 1883-1885, Muzeul Naţional de Istorie a României

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Philipp Friedrich Christoph, Count of Hohenzollern (Study), 1883-1885, Muzeul Naţional de Istorie a României

© Muzeul Naţional de Istorie a României, Bukarest (MNIR) -

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Philipp Friedrich Christoph, Count of Hohenzollern, 1883, Muzeul Național Peleș

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Philipp Friedrich Christoph, Count of Hohenzollern, 1883, Muzeul Național Peleș

© Muzeul Național Peleș -

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Eitel Friedrich VII, Count of Zollern (Study), 1883-1885, Muzeul Naţional de Istorie a României

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Eitel Friedrich VII, Count of Zollern (Study), 1883-1885, Muzeul Naţional de Istorie a României

© Muzeul Naţional de Istorie a României, Bukarest (MNIR) -

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Eitel Friedrich VII, Count of Zollern, 1883/84, Muzeul Național Peleș

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Eitel Friedrich VII, Count of Zollern, 1883/84, Muzeul Național Peleș

© Muzeul Național Peleș -

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of an Ancestor of the Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen Family (Johann Georg, Count of Hohenzollern?) (Study), 1883-1885, Muzeul Naţional de Istorie a României

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of an Ancestor of the Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen Family (Johann Georg, Count of Hohenzollern?) (Study), 1883-1885, Muzeul Naţional de Istorie a României

© Muzeul Naţional de Istorie a României, Bukarest (MNIR) -

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Johann Georg, Count of Hohenzollern, 1883/84, Muzeul Național Peleș

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Johann Georg, Count of Hohenzollern, 1883/84, Muzeul Național Peleș

© Muzeul Național Peleș -

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Wolfgang, Count of Zollern (Study), circa 1884, Muzeul Naţional de Istorie a României

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Wolfgang, Count of Zollern (Study), circa 1884, Muzeul Naţional de Istorie a României

© Muzeul Naţional de Istorie a României, Bukarest (MNIR) -

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Wolfgang, Count of Zollern, 1884, Muzeul Național Peleș

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Wolfgang, Count of Zollern, 1884, Muzeul Național Peleș

© Muzeul Național Peleș -

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Friedrich I, Count of Zollern (Study), circa 1884, Muzeul Naţional de Istorie a României

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Friedrich I, Count of Zollern (Study), circa 1884, Muzeul Naţional de Istorie a României

© Muzeul Naţional de Istorie a României, Bukarest (MNIR) -

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Friedrich I, Count of Zollern, 1884, Muzeul Național Peleș

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Friedrich I, Count of Zollern, 1884, Muzeul Național Peleș

© Muzeul Național Peleș

Gustav Klimt: The Muse Thalia, 1884/85, Muzeul Național Peleș

© Muzeul Național Peleș

Castle Theater, in: Jacob von Falke: Das rumänische Königsschloss Pelesch, Vienna 1893.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Decoration of the Castle’s Theater

From 1884, the “Künstler-Compagnie” further executed a 15-meter-long frieze showing various allegories and muses on eight canvases. The frieze was originally intended for the music room, or – according to Matsch – for the library of the Romanian Queen Elisabeth. Following a change in the decoration concept, the frieze – except for a section that was later mounted in one of the guest rooms on the second floor due to a lack of space – was used for the castle’s small theater. Additionally, Franz Matsch created the ceiling painting The Poet and Poetry for the room in 1884. Gustav Klimt also furnished a draft for this room, though the planned work Poet and Muse (c. 1884, private collection) was never realized.

Literature and sources

- Jacob von Falke: Das rumänische Königsschloss Pelesch, Vienna 1893.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012, S. 529-532.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007, S. 238-241.

- Muzeul Național Peleș (Hg.): Gustav Klimt & Künstlerkompagnie. Klimt la Castelul Peles. Catalogul lucrarilor lui Gustav Klimt si Künstlerkompagnie de la Muzeul National Peles, Sinaia 2012.

- Lucia Curta: Painter and King: Gustav Klimt's Early Decorative Work at Peleş Castle, Romania, 1883-1884, in: Studies in the Decorative Arts, Band 12 (2004/05), S. 98-129.

- Mihai Haret: Castelul Peleş, Bucharest 1924.

- Léo Bachelin: Castel Pelesch. Résidence d'été du Roi Charles Ier de Roumanie à Sinaia. Notice descriptive et historique, Paris 1893.

- Herbert Giese: Franz von Matsch – Leben und Werk. 1861–1942. Dissertation, Vienna 1976, S. 286.

- Herbert Giese: Matsch und die Brüder Klimt. Regesten zum Frühwerk Gustav Klimts, in: Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Galerie, 22/23. Jg., Nummer 66/67 (1978/79), S. 48-68.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band I, 1878–1903, Salzburg 1980, S. 31-35.

- Christian M. Nebehay (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Dokumentation, Vienna 1969, S. 100-101.

- Pester Lloyd, 30.09.1896, S. 3.

- Neue Illustrierte Zeitung, 17.09.1882, S. 803.

- Carl von Lützow: Das rumänische Königsschloss Pelesch, in: Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst, N.F., 5. Jg. (1894), S. 241-245.

- Narcis Dorin Ion: Gustav Klimt and the Künstler-Compagnie at Peles Castle, in: Deborah Pustišek Antić (Hg.): The Unknown Klimt. Love, Death, Ecstasy, Ausst.-Kat., Muzej Grada Rijeke (Rijeka), 20.04.2021–20.10.2021, Rijeka 2021, S. 32-39.

- Centralblatt der Bauverwaltung, 17.02.1894, S. 65-66.

- N. N.: Atelier Klimt und Matsch, in: Mittheilungen des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie. Monatsschrift für Kunst und Gewerbe, 20. Jg., Heft 232 (1885), S. 308.

- Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung (Mittagsausgabe), 12.10.1883, S. 3.

- Neue Freie Presse (Abendausgabe), 10.09.1875, S. 1.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco (Hg.): Gustav Klimt und die Künstler-Compagnie, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 20.06.2007–14.10.2007, Weitra 2007, S. 74-89.

Stadttheater Fiume

Fiume City Theater, in: Erzherzog Rudolf (Hg.): Die österreichisch-ungarische Monarchie in Wort und Bild, Band 12, Vienna 1893.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

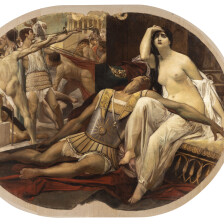

In the mid-1880s, the “Künstler-Compagnie” received the commission to decorate the interior of the municipal theater in Fiume – yet another theater designed by Fellner & Helmer. The commission included six ceiling paintings, as well as a proscenium painting and two smaller paintings for the auditorium.

The “Künstler-Compagnie,” made up of Gustav and Ernst Klimt as well as Franz Matsch, received a new commission likely in the course of 1884. Within a short period of time, they were to create a total of nine paintings for the auditorium of the municipal theater in Fiume (now Rijeka, Croatia), yet another theater designed by the Viennese architectural office Fellner & Helmer.

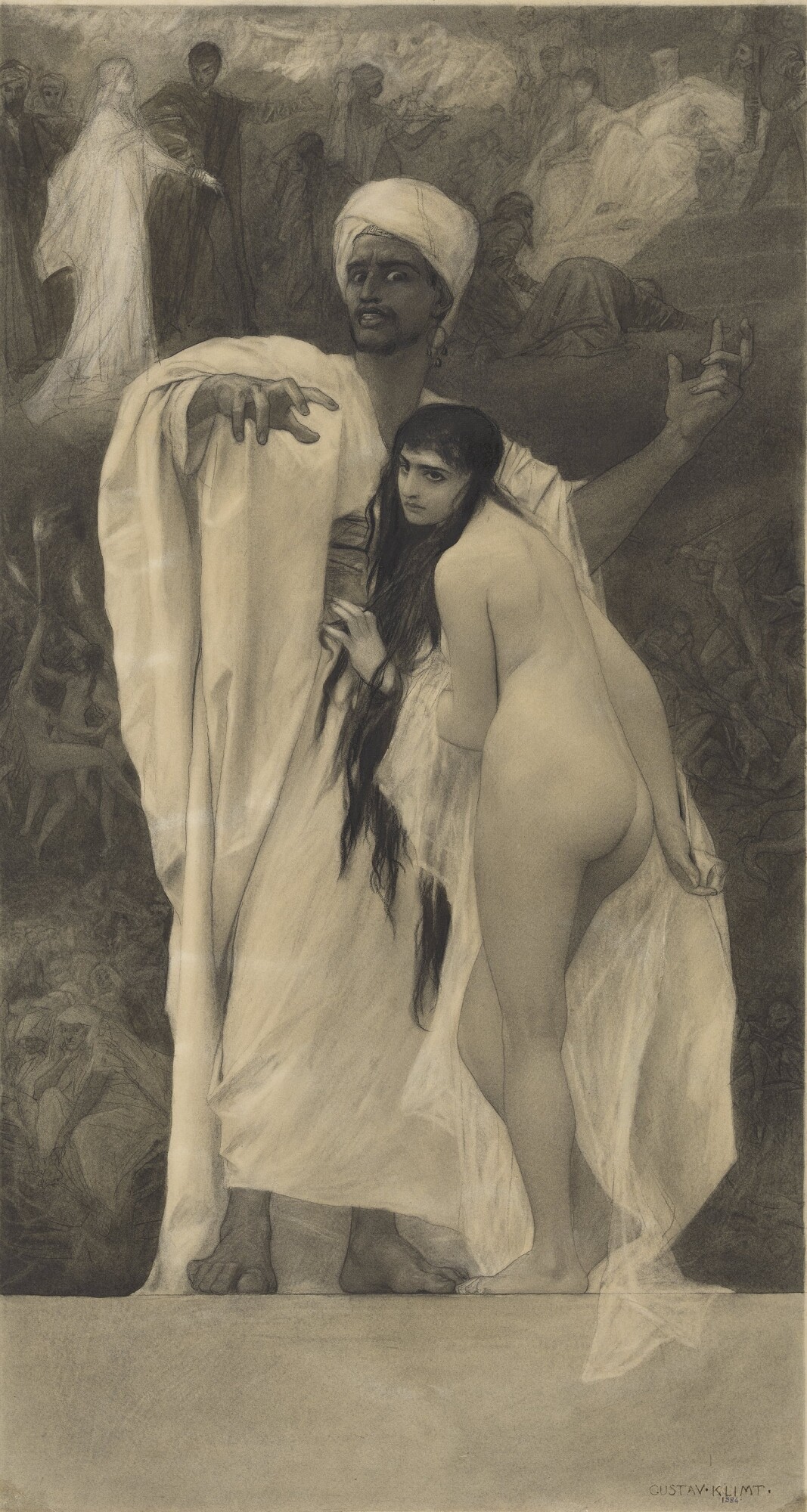

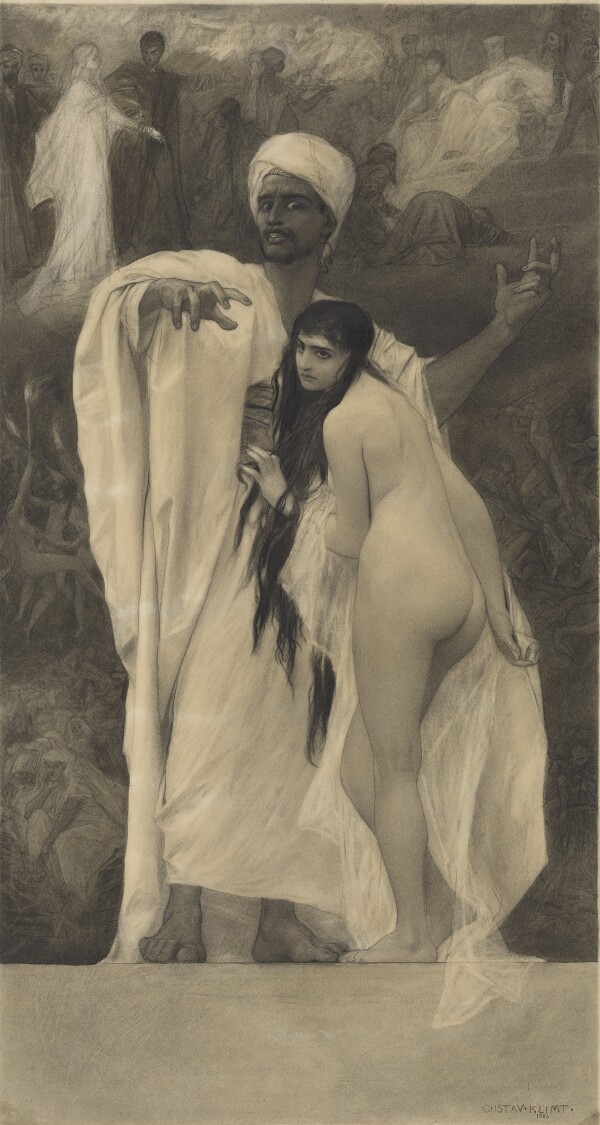

“Allegories of Various Music Genres”

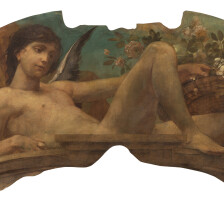

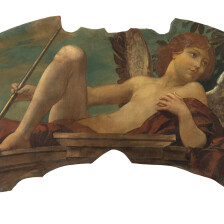

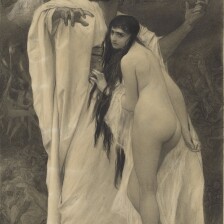

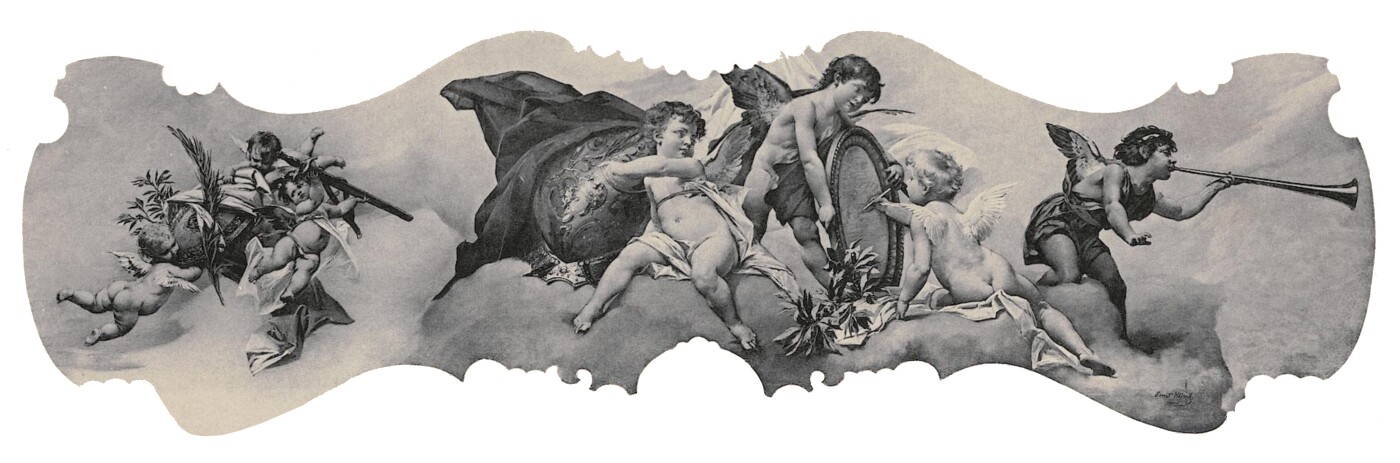

Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch each painted three of the ceiling paintings, arranged as a circle. Together, they represent the various genres of music. In the contemporary press, these depictions, along with the proscenium painting, were referred to as “allegories of various music genres,” or, more specifically, as “dance, love, battle, concert, operetta, religious music and singing.” The proscenium painting, as well as two smaller fanlight paintings – featuring putti – above the dignitaries’ boxes, were created by Ernst Klimt.

Decoration of the Stadttheater Fiume

-

Gustav Klimt: Mark Antony and Cleopatra (Allegory of Opera Seria), 1885, Hrvatsko narodno kazalište Ivana pl. Zajca

Gustav Klimt: Mark Antony and Cleopatra (Allegory of Opera Seria), 1885, Hrvatsko narodno kazalište Ivana pl. Zajca

© City Museum of Rijeka -

Gustav Klimt: Saint Cecilia (Allegory of Music), 1885, Hrvatsko narodno kazalište Ivana pl. Zajca

Gustav Klimt: Saint Cecilia (Allegory of Music), 1885, Hrvatsko narodno kazalište Ivana pl. Zajca

© City Museum of Rijeka -

Gustav Klimt: Orpheus and Eurydice (Allegory of Poetry), 1885, Hrvatsko narodno kazalište Ivana pl. Zajca

Gustav Klimt: Orpheus and Eurydice (Allegory of Poetry), 1885, Hrvatsko narodno kazalište Ivana pl. Zajca

© City Museum of Rijeka -

Franz Matsch: Allegory of the Dance, 1885, Hrvatsko narodno kazalište Ivana pl. Zajca

Franz Matsch: Allegory of the Dance, 1885, Hrvatsko narodno kazalište Ivana pl. Zajca

© City Museum of Rijeka -

Franz Matsch: Allegory of cheerful opera, 1885, Hrvatsko narodno kazalište Ivana pl. Zajca

Franz Matsch: Allegory of cheerful opera, 1885, Hrvatsko narodno kazalište Ivana pl. Zajca

© City Museum of Rijeka -

Franz Matsch: Allegory of love poetry, 1885, Hrvatsko narodno kazalište Ivana pl. Zajca

Franz Matsch: Allegory of love poetry, 1885, Hrvatsko narodno kazalište Ivana pl. Zajca

© City Museum of Rijeka -

Ernst Klimt: Allegory of Theater Art, 1885, Croatian National Theater Ivan Zajc, Rijeka

Ernst Klimt: Allegory of Theater Art, 1885, Croatian National Theater Ivan Zajc, Rijeka

© City Museum of Rijeka -

Ernst Klimt: Angel with a Basket of Flowers, 1885, Croatian National Theater Ivan Zajc, Rijeka

Ernst Klimt: Angel with a Basket of Flowers, 1885, Croatian National Theater Ivan Zajc, Rijeka

© City Museum of Rijeka -

Ernst Klimt: Angel with Trumpet, 1885, Croatian National Theater Ivan Zajc, Rijeka

Ernst Klimt: Angel with Trumpet, 1885, Croatian National Theater Ivan Zajc, Rijeka

© City Museum of Rijeka

Ceiling ensemble

© Hrvatsko narodno kazalište Ivana pl. Zajca, Rijeka

Announcement poster from 1885 for the first plays performed at the Fiume Municipal Theater

© City Museum of Rijeka

Gustav Klimt: Orpheus and Eurydice (Allegory of Poetry) (Study), 1885, Muzeul Naţional de Artă al României

© Muzeul Naţional de Artă al României

Presentation in Vienna

In March 1885, the “Künstler-Compagnie” briefly presented their works as part of an exhibition at the Austrian Museum of Art and Industry (now MAK, Vienna). The few reviews of this presentation gave positive feedback to the Klimt brothers and Franz Matsch: A critic writing for the Kunstchronik assessed the execution and coloring of the paintings “as animated and skilled.” A reviewer for the daily newspaper Neue Freie Presse wrote:

“The new paintings (in distemper) are so imaginative, so cleverly composed into the room, and painted with such skill, that we can only hope that the three highly gifted artists will soon be tasked with a similar commission in Vienna.”

We do not know precisely when the finished paintings were transported to Fiume. The official inauguration of the theater took place in early October 1885 – about half a year after the works’ public presentation in Vienna – with a performance of Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida.

The Whereabouts of Klimt’s Drafts

The three drafts Klimt created for the Fiume commission remained in the artist’s possession. In November 1904, he gave them to the gallery of H. O. Miethke to be sold, where they were erroneously listed as oil sketches for the theater in Bucharest. The sketch for Orpheus and Eurydice (Allegory of Poetry) (1885) was acquired in the summer of 1912 by a collector from Bucharest. It is housed today by the Muzeul Național de Artă al României in the Romanian capital. The same year, the Austrian State Gallery (now Belvedere, Vienna) purchased the two other drafts for 350 crowns (c. 1,940 euros) each. Today, the institution only holds the draft for Saint Ceclia (Allegory of Instrumental Music) (1885); the work Antony and Cleopatra (Allegory of Opera Seria) (1885) was stolen in 1946, and is considered lost to this day.

Literature and sources

- Irena Kraševac: Allegorische Bilder von Gustav Klimt und Franz Matsch im Stadttheater von Rijeka (Fiume), in: Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für vergleichende Kunstforschung in Wien, 67. Jg., Heft 1/2 (2019), S. 1-17.

- k. k. Österreichisches Museum für Kunst und Industrie (Hg.): Jahresbericht des k. k. Österreichischen Museum für Kunst und Industrie für 1885, Vienna 1885, S. 4.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Die Galerie Miethke. Eine Kunsthandlung im Zentrum der Moderne, Ausst.-Kat., Jewish Museum Vienna (Vienna), 19.11.2003–08.02.2004, Vienna 2003, S. 250.

- Neue Freie Presse (Morgenausgabe), 24.03.1885, S. 7.

- Die Presse, 24.03.1885, S. 10.

- Deborah Pustišek Antić (Hg.): The Unknown Klimt. Love, Death, Ecstasy, Ausst.-Kat., Muzej Grada Rijeke (Rijeka), 20.04.2021–20.10.2021, Rijeka 2021.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt 150 Jahre, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 13.07.2012–27.01.2013, Vienna 2012, S. 36-43.

- Die Presse, 08.10.1885, S. 11.

- Neue Freie Presse, 16.12.1883, S. 17.

- Neue Freie Presse, 31.10.1885, S. 24.

- Der Bautechniker. Centralorgan für das österreichische Bauwesen, 3. Jg., Nummer 8 (1883), S. 3.

- Der Bautechniker. Centralorgan für das österreichische Bauwesen, 5. Jg., Nummer 51 (1885), S. 1-2.

- Kunstchronik. Wochenschrift für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, 20. Jg., Heft 26 (1884/85), Spalte 446.

- Wiener Zeitung, 24.03.1885, S. 5.

- Neuigkeits-Welt-Blatt, 09.08.1885, S. 7.

- N. N.: Atelier Klimt und Matsch, in: Mittheilungen des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie. Monatsschrift für Kunst und Gewerbe, 20. Jg., Heft 232 (1885), S. 308.

- Marian Bisanz-Prakken: Gustav Klimt's Drawings for the Ceiling Paintings in the Fiume/Rijeka Teatro Comunale, in: Deborah Pustišek Antić (Hg.): The Unknown Klimt. Love, Death, Ecstasy, Ausst.-Kat., Muzej Grada Rijeke (Rijeka), 20.04.2021–20.10.2021, Rijeka 2021, S. 98-115.

Hermesvilla

Hermesvilla in the Lainzer Tiergarten, an etching after a photograph by Josef Löwy

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

The “Künstler-Compagnie” decorated the cavetto of Empress Elisabeth’s bedroom in the Hermesvilla with scenes from William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and created a ceiling painting for the villa’s salon. They partly worked from drafts by their former teacher Julius Victor Berger, and partly after their own designs.

On 10 June 1882, the architect Carl Freiherr von Hasenauer was commissioned by Emperor Franz Joseph I to design a “palace for dreaming.” In early 1884, the Emperor transferred ownership of the building to Empress Elisabeth. Within a construction period of only five years (1882–1886), Hasenauer realized the building at the Lainzer Tiergarten, which was financed with the Emperor’s private funds. The construction and interior design were declared completed on 7 July 1886. Situated on the outskirts of the city and the Vienna Woods, the Hermesvilla was to serve the Empress, Crown Prince Rudolph and Emperor Franz Joseph I as a “hunting lodge in the Imperial-Royal zoological garden.”

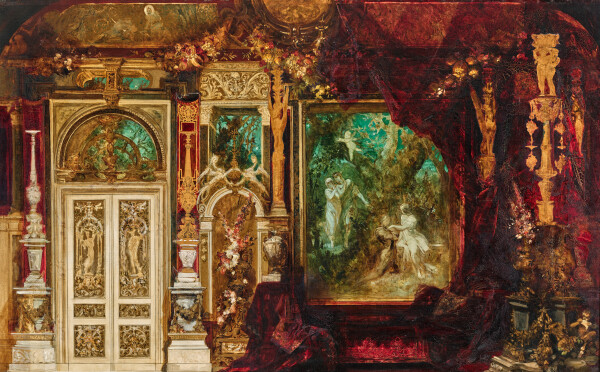

Hans Makart: Decoration design for Empress Elisabeth's bedroom in the Hermes Villa, 1882, Belvedere, Vienna

© Belvedere, Vienna

Carl Hasenauer: Design sketches for the bedroom of the Hermesvilla, The Albertina Museum, Vienna

©

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

For the villa’s interior design, the Emperor commissioned the most renowned artists of the Monarchy, whose styles were aligned with the Emperor’s tastes. These were Carl von Hasenauer, the sculptor Viktor Tilgner and the painter Hans Makart. Makart had previously decorated the main curtain of the Wiener Stadttheater with scenes from William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1872, Wien Museum, Vienna). Ten years later, the Emperor personally commissioned the famous painter to decorate the Hermesvilla. The bedroom, especially, was to receive a sumptuous decor in keeping with Makart’s distinctive style. In terms of its theme, it was to draw upon Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, whose fairytale-like aura, with a hint of irony, held a special fascination for Elisabeth. A Decoration Design (1882, Belvedere, Vienna), conceived by Makart for Empress Elisabeth’s bedroom, gives us an inkling of the wealth of colors, materials and fabrics. Due to Makart’s early death, the designs could not be executed by the master himself. Makart’s students Eduard Charlemont, Carl Rudolf Huber and Julius Victor Berger took over and reworked their mentor’s designs.

In 1885, the “Künstler-Compagnie” joined the decoration project for the Hermesvilla in Lainz near Vienna. Under the direction of their former teacher Berger, Franz Matsch as well as Ernst and Gustav Klimt designed the scenes in the cavettos of the bedroom. This was a major step for the young artists, which helped them secure future commissions for prestigious buildings on the Vienna Ringstraße. At the same time, the commission marked the advancement of the artists of the “Künstler-Compagnie” from theater painters in the crown lands to serious decorative painters in the residential city Vienna.

Gustav Klimt, Ernst Klimt, Franz Matsch: A Midsummer Night's Dream, 1884/85, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Insight into the Hermesvilla, before 1900, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Gustav Klimt, Ernst Klimt, Franz Matsch: Spring, 1885, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Salon

Along with the cavettos, the artists of the “Künstler-Compagnie” also decorated the ceiling of the Empress’ salon with a depiction of spring. The work Spring (1885, Wien Museum, Hermesvilla, Vienna) shows a hunting Diana and Flora, clad in white dresses, along with putti and rose garlands. In the renowned magazine of the Imperial-Royal Austrian Museum of Art and Industry Mittheilungen des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie, the art historian and curator of the Imperial-Royal Court Museum of Art History, Albert Ilg, commented favorably:

“Klimt and Matsch painted the ceiling with genii and floating girls who, laden with floral wreaths, stand out against the blue air. The two highly gifted painters have given us yet another demonstration of their taste and fresh manner of painting.”

As the work, executed in oil on plaster, sustained serious damage in the middle of the 20th century and was subsequently unprofessionally restored, it is impossible today to distinguish the hands of the individual artists. This is also true for the cavetto paintings, for which the painters of the “Künstler-Compagnie” followed Berger’s designs.

Literature and sources

- Albert Ilg: Die kaiserliche Villa im Thiergarten, in: Mittheilungen des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie. Monatsschrift für Kunst und Gewerbe, N.F., 2. Jg., Heft 9 (1887), S. 427-431.

- Renata Kassal-Mikula: Kaiserin Elisabeths Schlafzimmer, in: Wien Museum (Hg.): Hans Makart. Malerfürst (1840-1884), Ausst.-Kat., Hermesvilla (Vienna), 14.10.2000–16.04.2001, Vienna 2000, S. 132.

- Ralph Gleis (Hg.): Makart. Ein Künstler regiert die Stadt, Ausst.-Kat., Vienna Museum (Vienna), 09.06.2011–16.10.2011, Munich 2011, S. 183.

Stadttheater Karlsbad

Carlsbad Municipal Theater

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

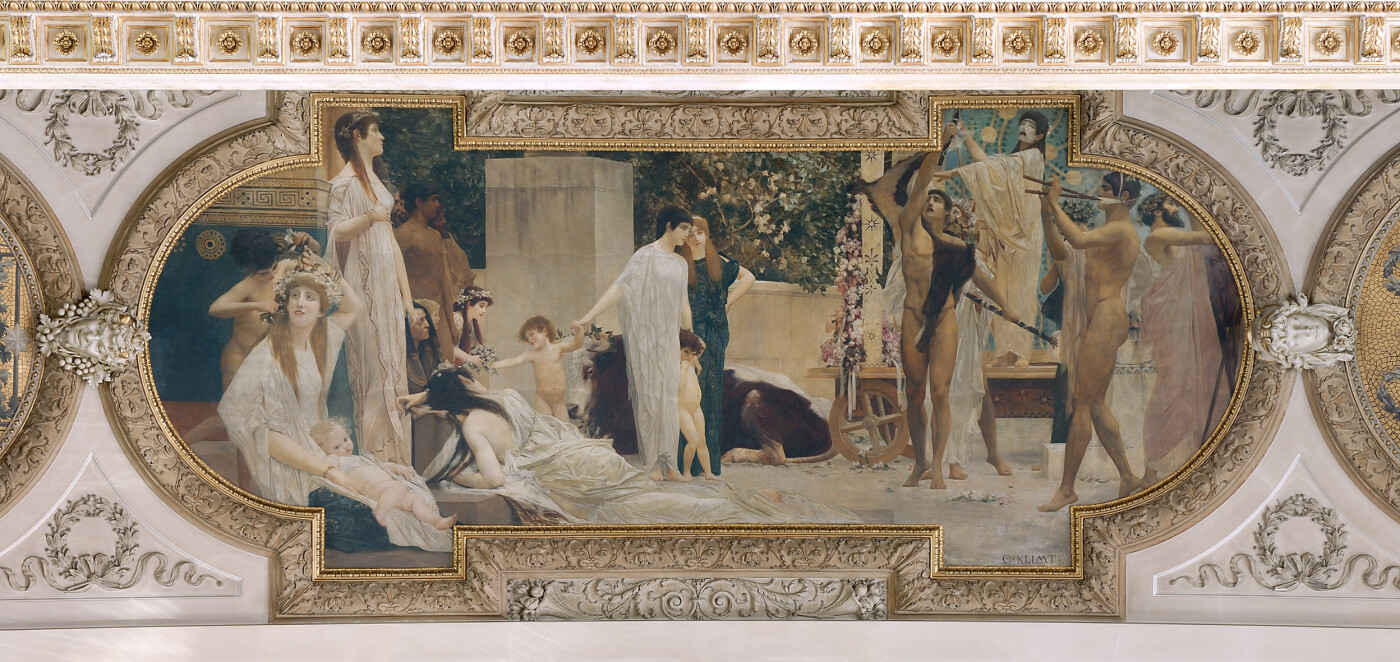

Franz Matsch and the Klimt brothers continued their successful partnership for the municipal theater in Karlsbad, which opened in 1886, creating four ceiling paintings, one proscenium painting and a stage curtain. The latter was temporarily displayed to the public at the Imperial-Royal Museum of Art and Industry in Vienna.

In the Bohemian city of Karlsbad (now Karlovy Vary, Czech Republic), a popular spa town in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, a new, free-standing municipal theater opened on 15 May 1886. Following several competitions, the contract for the construction of the theater had been awarded in 1883 to the new Viennese architectural office Fellner & Helmer.

The “Künstler-Compagnie” was commissioned in 1884 to decorate the theater, likely once more at the recommendation of the two Viennese architects. As with earlier theater projects, Ernst Klimt created a proscenium painting, while Franz Matsch and Gustav Klimt executed the four ceiling paintings for the auditorium, Play, Hunt, Dance and Delights of the Table (all 1886, Karlovarské městské divadlo, Karlsbad). We know very little today about the process of these works’ creation, as only Klimt’s draft for Delights of the Table (1886, private collection) has survived.

Interior Decoration of the Stadttheater Karlsbad

-

Gustav Klimt: Delights of the Table, 1886, Karlovarské městské divadlo

Gustav Klimt: Delights of the Table, 1886, Karlovarské městské divadlo

© Heidelberg University Library -

Gustav Klimt: Dance, 1886, Karlovarské městské divadlo

Gustav Klimt: Dance, 1886, Karlovarské městské divadlo

© Heidelberg University Library -

Franz Matsch: The Hunt, 1886, Karlovarské městské divadlo, in: Josef Löwy: Figurale Compositionen für die malerische Ausschmückung von Decken, Wänden, Zwickeln, Lünetten und kunstgewerblichen Objecten aller Art. Lichtdrucke nach Gemälden und Zeichnungen Wiener Künstler, Band 2, Vienna 1898.

Franz Matsch: The Hunt, 1886, Karlovarské městské divadlo, in: Josef Löwy: Figurale Compositionen für die malerische Ausschmückung von Decken, Wänden, Zwickeln, Lünetten und kunstgewerblichen Objecten aller Art. Lichtdrucke nach Gemälden und Zeichnungen Wiener Künstler, Band 2, Vienna 1898.

© Heidelberg University Library -

Franz Matsch: The Game, 1886, Karlovarské městské divadlo, in: Josef Löwy: Figurale Compositionen für die malerische Ausschmückung von Decken, Wänden, Zwickeln, Lünetten und kunstgewerblichen Objecten aller Art. Lichtdrucke nach Gemälden und Zeichnungen Wiener Künstler, Band 2, Vienna 1898.

Franz Matsch: The Game, 1886, Karlovarské městské divadlo, in: Josef Löwy: Figurale Compositionen für die malerische Ausschmückung von Decken, Wänden, Zwickeln, Lünetten und kunstgewerblichen Objecten aller Art. Lichtdrucke nach Gemälden und Zeichnungen Wiener Künstler, Band 2, Vienna 1898.

© Heidelberg University Library -

Ernst Klimt: Proscenium painting, 1886, Karlovarské městské divadlo, in: Josef Löwy: Figurale Compositionen für die malerische Ausschmückung von Decken, Wänden, Zwickeln, Lünetten und kunstgewerblichen Objecten aller Art. Lichtdrucke nach Gemälden und Zeichnungen Wiener Künstler, Band 2, Vienna 1898.

Ernst Klimt: Proscenium painting, 1886, Karlovarské městské divadlo, in: Josef Löwy: Figurale Compositionen für die malerische Ausschmückung von Decken, Wänden, Zwickeln, Lünetten und kunstgewerblichen Objecten aller Art. Lichtdrucke nach Gemälden und Zeichnungen Wiener Künstler, Band 2, Vienna 1898.

© Heidelberg University Library

Frederic Leighton: Painter's Honeymoon, c. 1864, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

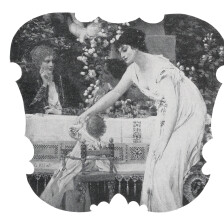

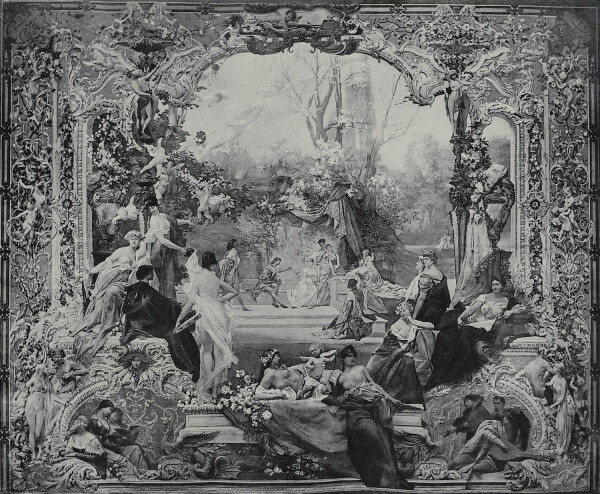

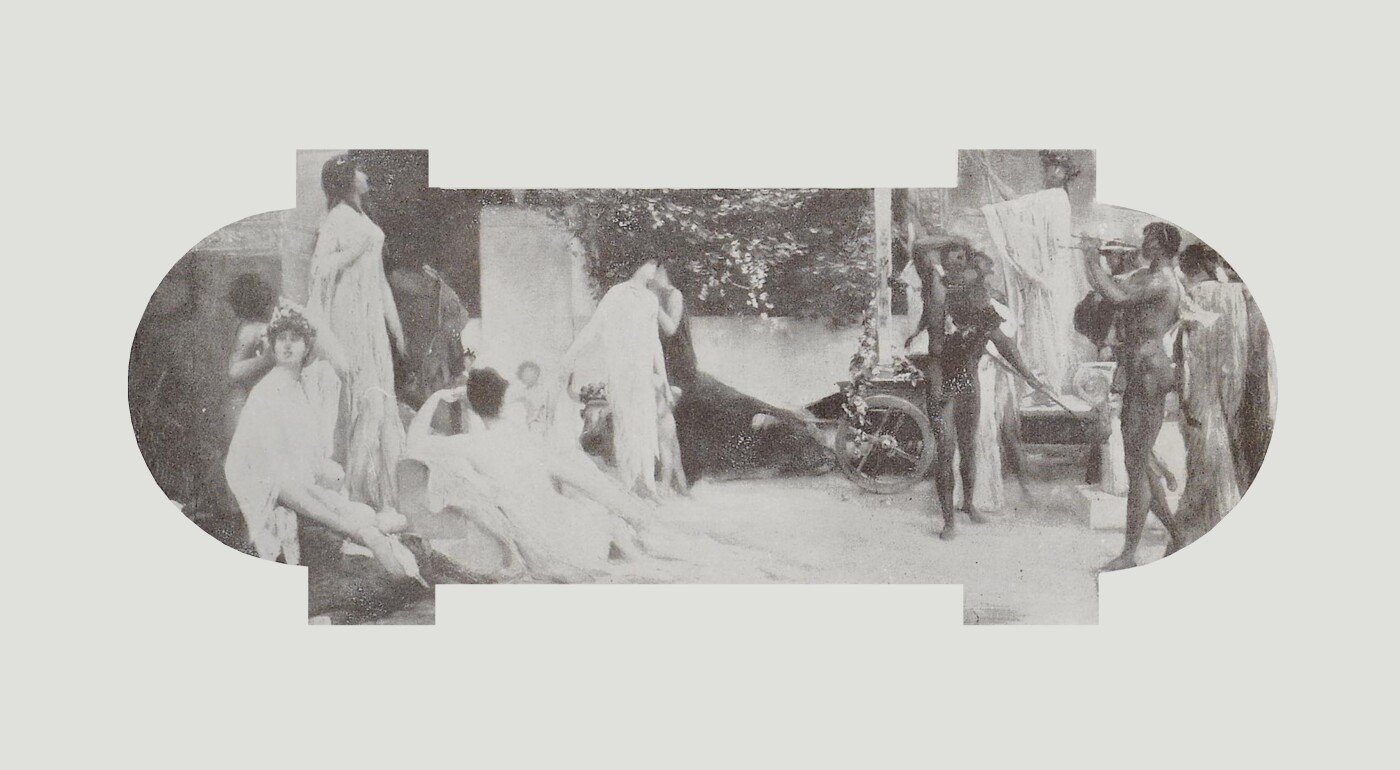

Gustav Klimt, Ernst Klimt, Franz Matsch: Homage to Dramatic Art, 1886, Karlovarské městské divadlo

© Heidelberg University Library

Ceiling ensemble (detail)

© Karlovarské městské divadlo

Artistic Influences

Compared to Klimt’s works for the Stadttheater Reichenberg (now Liberec, Czech Republic), the scenes in the two paintings appear a lot more animated. Figures viewed from the back direct the beholder’s gaze to the middle ground. Additionally, the composition of Delights of the Table is parallel to the picture plane, while that of Dance gives an impression of spatial depth. Moreover, these works are the first to reflect Klimt’s study of artworks from the former Imperial painting collection and his exploration of English art: The brocade cape of the lute player is reminiscent of Moretto da Brescia’s St. Justina, Venerated by a Donor (1530–1534, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna). The texture and patterns, as a whole, recall the ornamental fabric designs of the English painter and textile designer William Morris. Moreover, the genre-like character of the depictions might have been inspired by the painterly works of Frederic Leighton.

Homage to Dramatic Art

The stage curtain Homage to Dramatic Art (1886, Karlovarské městské divadlo, Karlsbad) was designed by the three artists together. Upon the work’s completion, and shortly before the theater’s official inauguration, the artists presented it over the weekend of 8 and 9 May 1886 at the Imperial-Royal Museum of Art and Industry in Vienna (now MAK, Vienna). The pictorial program can be inferred primarily from contemporary press reports, which suggest that the work was an allegorical depiction of poetry. A detailed description can be found in an exhibition review in the newspaper Neue Freie Presse, dated 9 May 1886:

“Surrounded by the nine muses, all of whom are aptly characterized and appear charmingly animated, there are groups which represent love, family life, the joy of life, etc. – the very subject matter that is brought to life by the muses in all the arts, and particularly in poetry. Through the magic of their colors, individual figures are reminiscent of Makart […].”

The same critic concluded that the curtain was “one of the most delightful things created in the area of decorative painting.”

Critical Voice

In this context, it seems all the more remarkable that on 26 June 1886, the Neue Freie Presse published a retrospective negative critique of the works by the “Künstler-Compagnie,” though all the paper’s previous reviews had been favorable. The written criticism exclusively targeted the ceiling paintings:

“These ceiling paintings were painted using deep colors and – each one taken as a coloristic spot – stand out against the pure white of the ceiling very emphatically, too emphatically, in fact. They appear to be falling out of the ceiling, and, through the contrast with the stark white, their content becomes indistinct.”

The unknown author located the reason for this shortcoming in the fact that the paintings were not created on site but rather at the artists’ studio. We do not know whether the three young artists reacted to the criticism.

Literature and sources

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012, S. 535.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007, S. 243.

- Die Presse, 08.05.1886, S. 10.

- Österreichische Badezeitung, 23.05.1886, S. 50.

- Prager Abendblatt, 18.05.1886, S. 3.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band I, 1878–1903, Salzburg 1980, S. 50-53.

- Josef Löwy: Figurale Compositionen für die malerische Ausschmückung von Decken, Wänden, Zwickeln, Lünetten und kunstgewerblichen Objecten aller Art. Lichtdrucke nach Gemälden und Zeichnungen Wiener Künstler, Band 2, Vienna 1898, Tafel 40-44A.

- Neue Freie Presse, 09.05.1886, S. 5.

- Neue Freie Presse, 26.06.1886, S. 4.

- Neue Freie Presse, 16.05.1886, S. 8.

- Neue Freie Presse, 13.05.1886, S. 4-5.

- Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 15.05.1886, S. 4.

- Wiener Abendpost. Beilage zur Wiener Zeitung, 18.05.1886, S. 3.

- Die Kunst für Alle. Malerei, Plastik, Graphik, Architektur, 3. Jg. (1887/88), S. 192-194.

- Kunstverlag Schroll (Hg.): Die malerische Ausschmückung des neuen Stadttheaters in Carlsbad. componirt und ausgeführt von Franz Matsch, Gustav Klimt und Ernst Klimt, Vienna 1886.

- Michaela Seiser: Die Künstler-Compagnie, in: Agnes Husslein-Arco (Hg.): Gustav Klimt und die Künstler-Compagnie, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 20.06.2007–14.10.2007, Weitra 2007, S. 8-73.

Imperial-Royal Hofburgtheater

k. k. Hofburgtheater, in: V. A. Heck Verlag (Hg.): Das k. k. Hofburgtheater in Wien. erbaut von Carl Freiherrn von Hasenauer, Vienna 1890.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

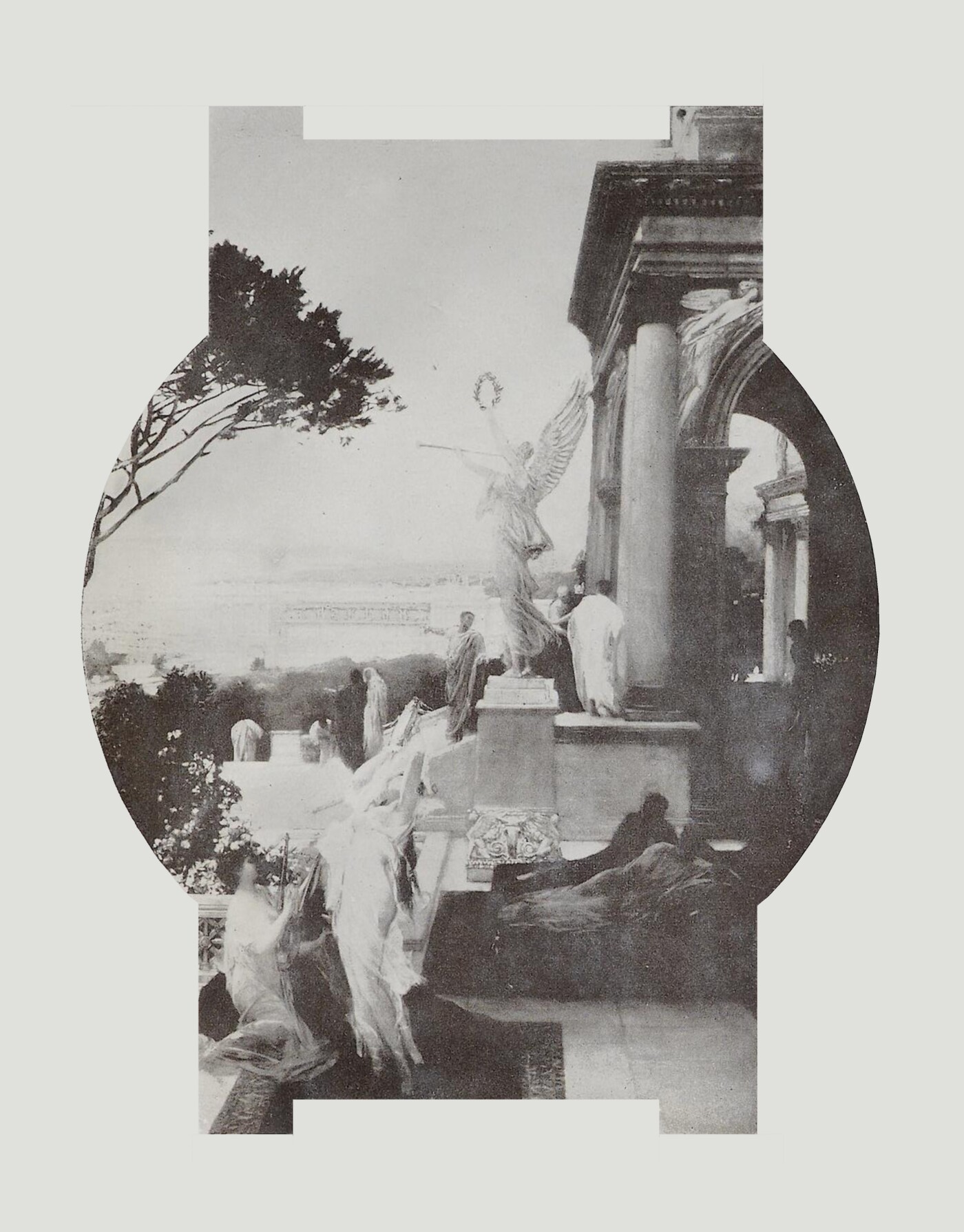

Between 1886 and 1888, the “Künstler-Compagnie” decorated the two prestigious staircases of the newly built Imperial-Royal Hofburgtheater with painterly scenes from theater history. It was the company’s first major independent commission in the residential city Vienna.

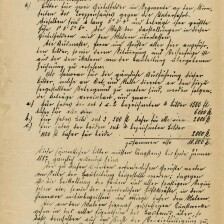

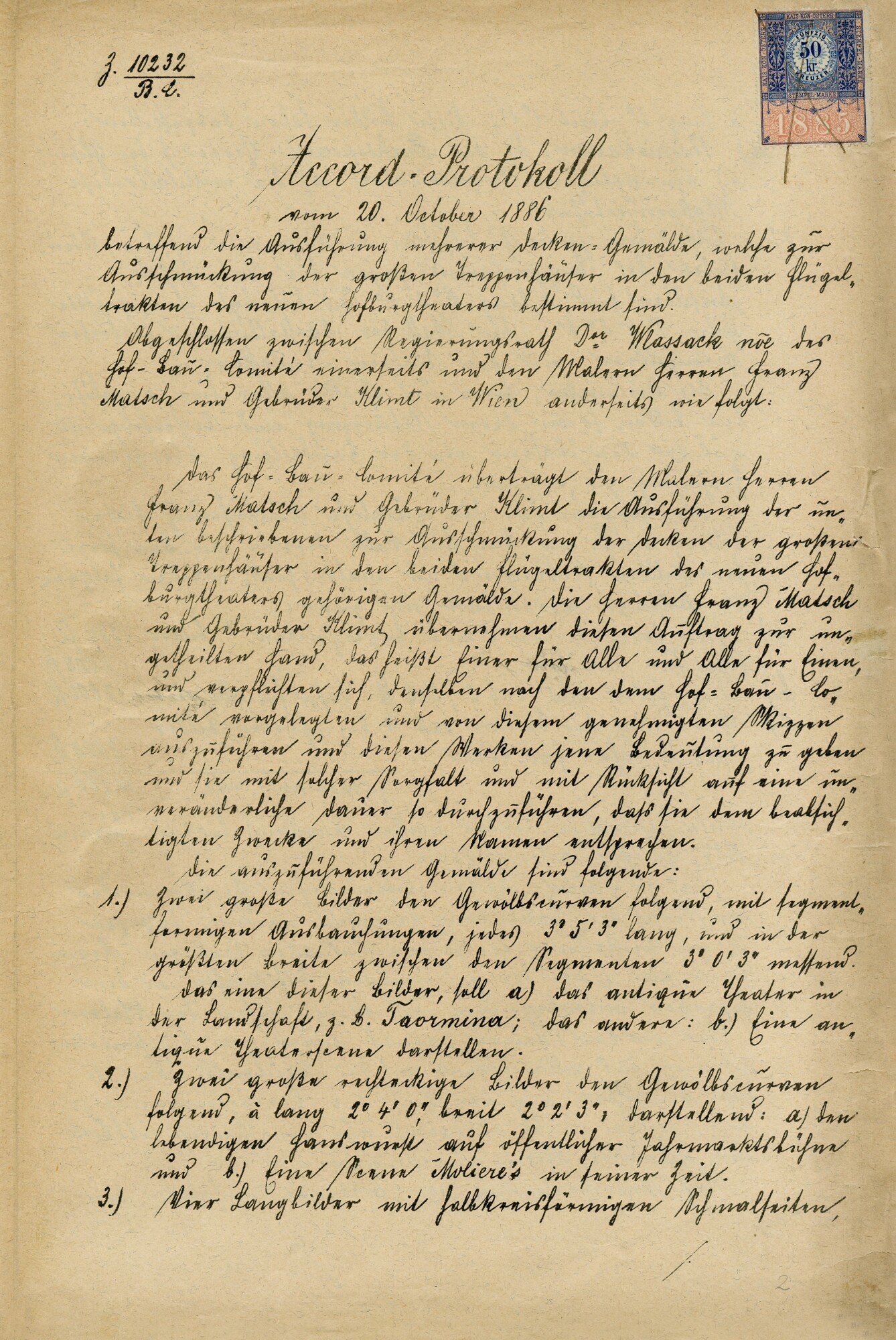

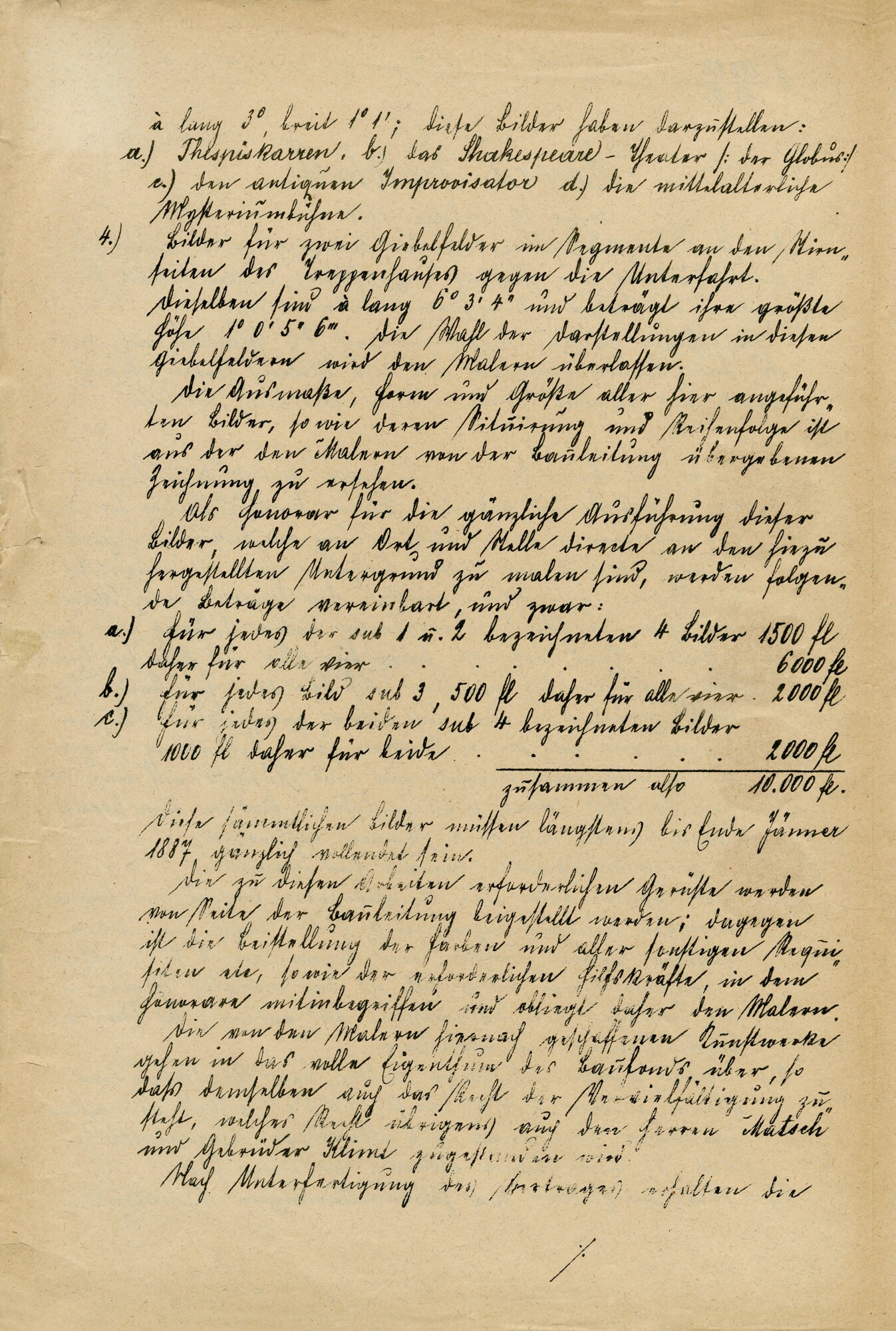

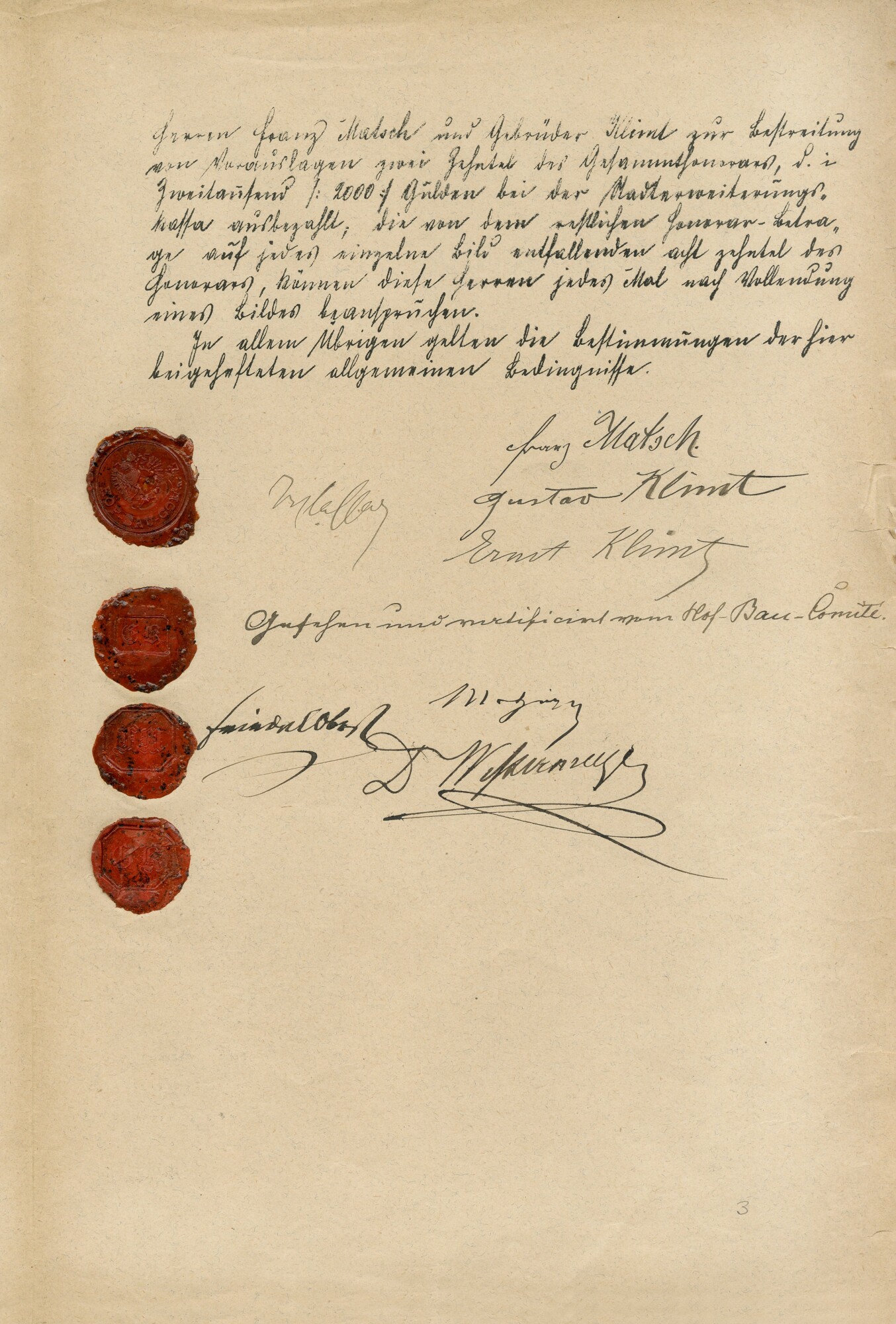

On 20 October 1886, the “Künstler-Compagnie” – likely on the recommendation of Rudolf Eitelberger – received a commission worth 10,000 guilders (c. 139,705 euros) to create ceiling paintings for the two lateral staircases of the Imperial-Royal Hofburgtheater (now Burgtheater, Vienna), planned by Gottfried Semper and Carl Hasenauer, to be carried out “exclusively by their hands.” In keeping with the program devised by the theater’s director Adolf von Wilbrandt, the paintings were to reflect the history of the theater from antiquity to the 18th century.

Agreement Protocol Regarding the Decoration of the Staircases in the Imperial-Royal Hofburgtheater

-

Piecework protocol concerning the decoration of the staircases in the Imperial-Royal Hofburgtheater, signed by Franz Matsch, Gustav and Ernst Klimt, Eduard Wlassack and members of the Court Building Committee, 10/20/1886, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

Piecework protocol concerning the decoration of the staircases in the Imperial-Royal Hofburgtheater, signed by Franz Matsch, Gustav and Ernst Klimt, Eduard Wlassack and members of the Court Building Committee, 10/20/1886, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

© Austrian State Archives, Vienna -

Piecework protocol concerning the decoration of the staircases in the Imperial-Royal Hofburgtheater, signed by Franz Matsch, Gustav and Ernst Klimt, Eduard Wlassack and members of the Court Building Committee, 10/20/1886, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

Piecework protocol concerning the decoration of the staircases in the Imperial-Royal Hofburgtheater, signed by Franz Matsch, Gustav and Ernst Klimt, Eduard Wlassack and members of the Court Building Committee, 10/20/1886, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

© Austrian State Archives, Vienna -

Piecework protocol concerning the decoration of the staircases in the Imperial-Royal Hofburgtheater, signed by Franz Matsch, Gustav and Ernst Klimt, Eduard Wlassack and members of the Court Building Committee, 10/20/1886, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

Piecework protocol concerning the decoration of the staircases in the Imperial-Royal Hofburgtheater, signed by Franz Matsch, Gustav and Ernst Klimt, Eduard Wlassack and members of the Court Building Committee, 10/20/1886, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Allgemeines Verwaltungs-, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (AVA)

© Austrian State Archives, Vienna

Franz Matsch senior: Antique Improviser (design), 1886-1887, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

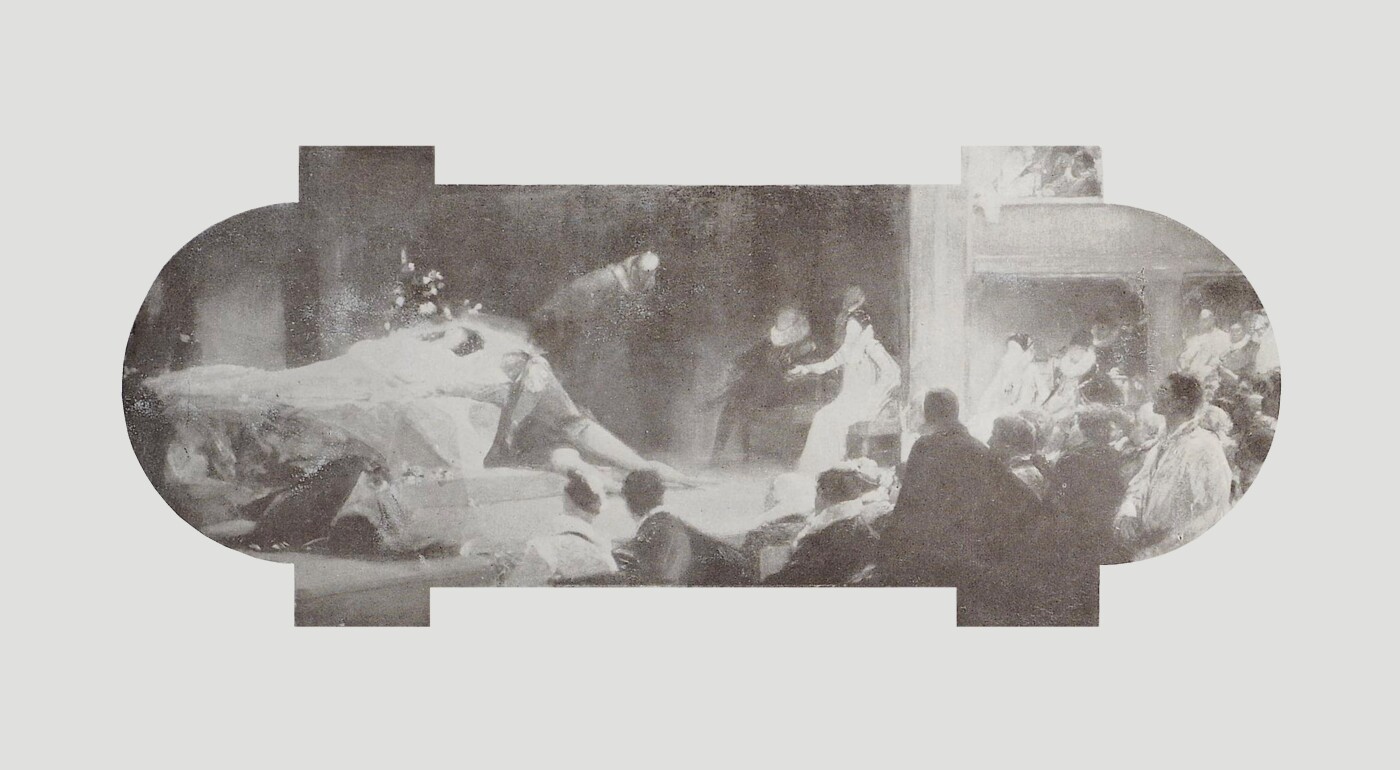

Of the total of ten secco paintings, Gustav Klimt executed four until 1888, preparing each of them with sketches and designs. More specifically, these works were Shakespeare’s Globe Theater, The Cart of Thespis and The Altar of Dionysus in the southern staircase, as well as The Theater in Taormina located in the northern stairwell (all 1886-1888, Burgtheater Vienna). A further four works were created by Franz Matsch, and two by Ernst Klimt. These paintings, executed with oil paints on pre-primed plaster, are the first to reveal artistic decisions which would impact on the development of Klimt’s modern pictorial language.

Artworks by Gustav Klimt for the Imperial-Royal Hofburgtheater

-

Gustav Klimt: Shakespeare's Globe Theater (Study), 1886, Verbleib unbekannt

Gustav Klimt: Shakespeare's Globe Theater (Study), 1886, Verbleib unbekannt

© Heidelberg University Library -

Gustav Klimt: Shakespeare's Globe Theater, 1886-1888, Burgtheater

Gustav Klimt: Shakespeare's Globe Theater, 1886-1888, Burgtheater

© Georg Soulek -

Gustav Klimt: The Cart of Thespis (Study), 1886, Verbleib unbekannt

Gustav Klimt: The Cart of Thespis (Study), 1886, Verbleib unbekannt

© Heidelberg University Library -

Gustav Klimt: The Cart of Thespis, 1888, Burgtheater

Gustav Klimt: The Cart of Thespis, 1888, Burgtheater

© Georg Soulek -

Gustav Klimt: The Altar of Dionysus (Study), 1886, Leopold Museum

Gustav Klimt: The Altar of Dionysus (Study), 1886, Leopold Museum

© Bank Austria Kunstsammlung -

Gustav Klimt: The Altar of Dionysus, 1888, Burgtheater

Gustav Klimt: The Altar of Dionysus, 1888, Burgtheater

© Georg Soulek -

Gustav Klimt: The Theater in Taormina (Study), 1886, private collection

Gustav Klimt: The Theater in Taormina (Study), 1886, private collection

© Heidelberg University Library -

Gustav Klimt: The Theater in Taormina, 1888, Burgtheater

Gustav Klimt: The Theater in Taormina, 1888, Burgtheater

© Georg Soulek

Ceiling ensemble in the southern stairwell

© Georg Soulek

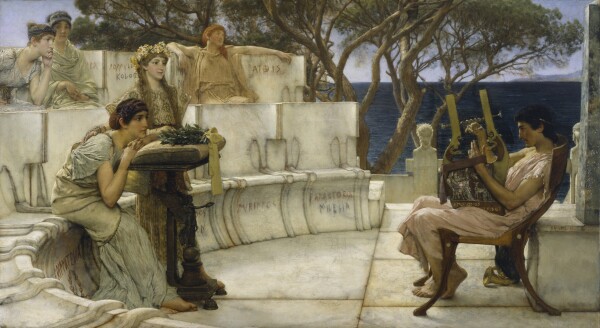

Lawrence Alma-Tadema: Sappho and Alcaeus, 1881, The Walters Art Museum

© The Walters Art Museum

Models and Photographic Templates

In these works, Gustav Klimt clearly strove for the greatest possible authenticity and vividness, rendering the furniture and buildings that were characteristic for each era in great detail. The meticulously reconstructed theater stages show the influence of the antiquity depictions of the highly successful Dutch painter Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema and the Englishman John William Waterhouse. In his personal style, Gustav Klimt also processed contemporary international tendencies in these works, such as the realistic history painting.

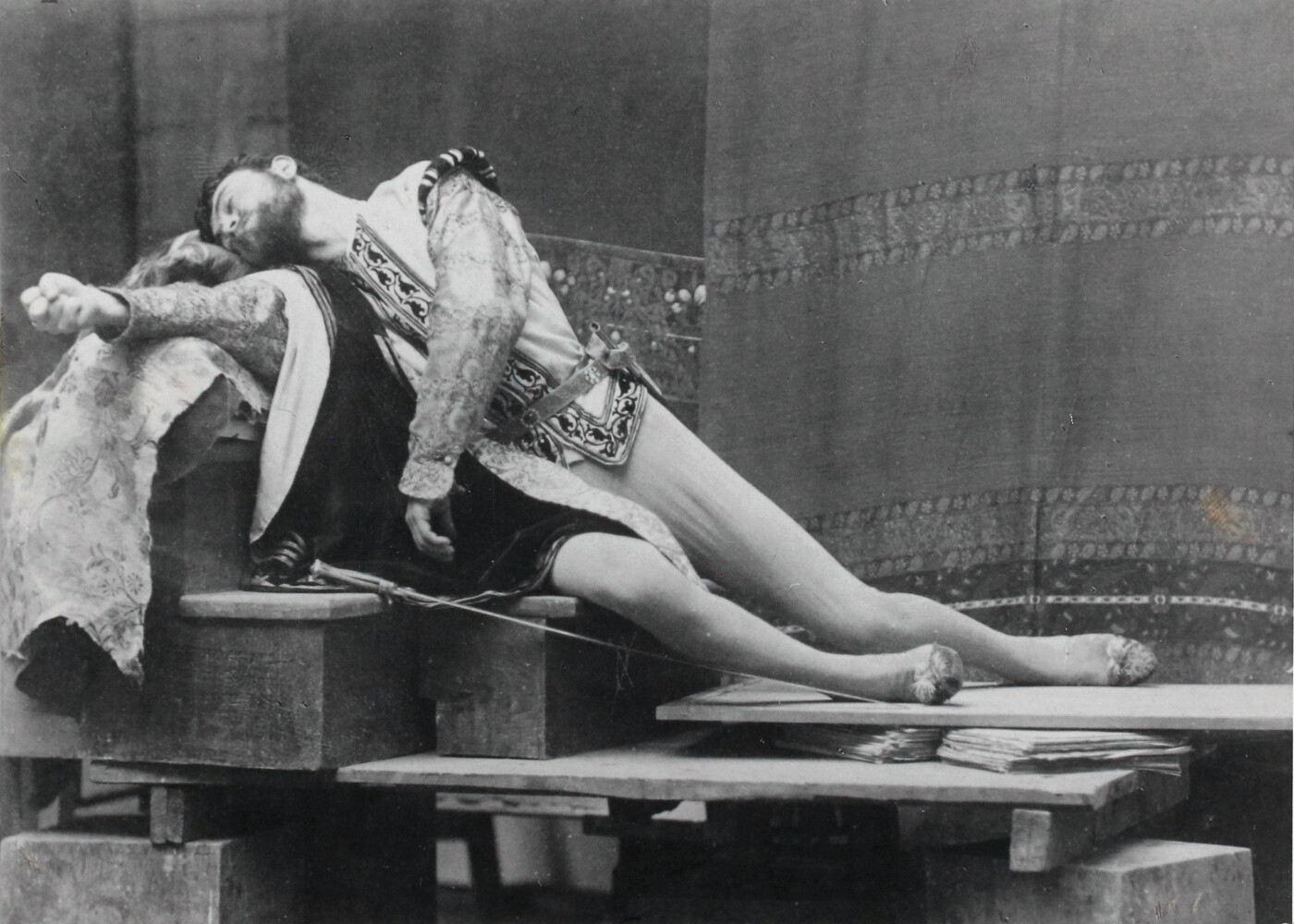

The artists of the “Künstler-Compagnie” carried out a series of detailed studies of clothes, objects and postures. Acting as models were family members and the three artists themselves. Photographs show them posing in authentic theater costumes. When comparing them directly, it is clear today that these photographs served as direct templates for the paintings.

Posture Photographs

-

Georg Klimt as "Romeo"

Georg Klimt as "Romeo"

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Johanna Zimpel as a model

Johanna Zimpel as a model

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna -

Hermine Klimt as a model

Hermine Klimt as a model

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Klimt’s Self-Portrait

Gustav Klimt used the opportunity to immortalize his own likeness in one of the ceiling paintings, positioning himself and his brother Ernst and Franz Matsch in the background as members of the audience in the rendering Shakespeare’s Globe Theater. This depiction is the only self-portrait known to date created by Gustav Klimt.

Gustav Klimt: Shakespeare's Globe Theater, 1886-1888, Burgtheater

© Georg Soulek

Golden Cross of Merit with Crown

© Dorotheum Vienna, Auction catalog 17.11.2017

Completion and Distinction

Upon completion of the works, Klimt appeared to have been unhappy with the result. Decades later, Franz Matsch recalled the artists’ mixed feelings at the time in his memoirs:

“Finally, the day of completion had arrived. When we saw our work for the first time in its entirety, without the scaffolding, we were gripped by despair. Gustav KLIMT, especially, uttered drastic words: Filth, utter filth and many more such flattering words – such was our verdict.”

The harsh self-criticism was unfounded, however. According to Matsch, the entire construction committee and the architect Carl von Hasenauer were very taken with the finished works created by the artists of the “Künstler-Compagnie.” Immediately after the official inauguration in October 1888, Gustav Klimt, his brother and Franz Matsch were awarded the Golden Cross of Merit with the Crown by Emperor Franz Joseph I for their artistic decoration of the theater. Latest by this time, the “Künstler-Compagnie” had made it into the top tier of Viennese artists.

Literature and sources

- Otmar Rychlik: Gustav Klimt, Franz Matsch und Ernst Klimt im Burgtheater, Vienna 2007.

- Josef Bayer: Vom Neuen Hofburgtheater. Die Theater Wiens, Dritter Band, Rückschau und Ergänzung, in: Die Graphischen Künste, 19. Jg. (1896), S. 87-104.

- Herbert Giese: Matsch und die Brüder Klimt. Regesten zum Frühwerk Gustav Klimts, in: Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Galerie, 22/23. Jg., Nummer 66/67 (1978/79), S. 48-68.

- Gesellschaft für Vervielfältigende Kunst (Hg.): Die Theater Wiens, Band III, Vienna 1894.

- Österreichische Kunst-Chronik, Nummer 41 (1888), S. 1017-1028.

- Österreichische Kunst-Chronik, Nummer 43 (1888), S. 1079.

- Kunstchronik. Wochenschrift für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, 22. Jg., Heft 8 (1886/87), Spalte 132.

- V. A. Heck Verlag (Hg.): Das k. k. Hofburgtheater in Wien. erbaut von Carl Freiherrn von Hasenauer, Vienna 1890.

- Christian M. Nebehay (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Dokumentation, Vienna 1969, S. 88-96.

- Akkord-Protokoll betreffend die Ausschmückung der Treppenhäuser im k. k. Hofburgtheater, unterschrieben von Franz Matsch, Gustav und Ernst Klimt, Eduard Wlassack und Mitgliedern des Hof-Bau-Comités (10/20/1886). AT-OeStA/AVA Inneres MdI STEF A Hofbauk. 30.36 fol. 2+3, .

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band I, 1878–1903, Salzburg 1980, S. 54-57.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007, S. 244-246.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012, S. 536-541.

- Wiener Zeitung, 30.10.1888, S. 1.

- Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, 14.10.1888, S. 1-4.

- Die Kunst für Alle. Malerei, Plastik, Graphik, Architektur, 4. Jg., Heft 3 (1888), S. 33-41.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Monika Faber (Hg.): Inspiration Fotografie. Von Makart bis Klimt, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna), 17.06.2016–30.10.2016, Vienna 2016, S. 210-213.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco (Hg.): Gustav Klimt und die Künstler-Compagnie, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 20.06.2007–14.10.2007, Weitra 2007, S. 56-67.

- Markus Fellinger: Klimt, die Künstler-Compagnie und das Theater, in: Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alexander Klee (Hg.): Klimt und die Ringstraße, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna), 05.07.2015–11.10.2015, Vienna 2015, S. 35-48.

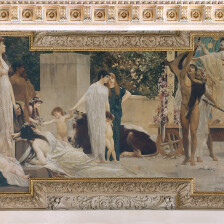

Allegories and Emblems

Front page, in: Martin Gerlach (Hg.): Allegorien und Embleme. Originalentwürfe von den hervorragendsten modernen Künstlern, sowie Nachbildungen alter Zunftzeichen und modernen Entwürfen von Zunftwappen im Charakter der Renaissance. Abtheilung I. Allegorien, Vienna 1882/84.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Starting in 1881, Gustav Klimt, commissioned by Martin Gerlach, worked on the sample collection Allegorien und Embleme [Allegories and Emblems]. He supplied designs for various allegories for this compilation of prints in the media of both drawing and oil painting.

Martin Gerlach’s portfolio Allegorien und Embleme served as a compilation of samples for artists and artisans and was intended to raise the general level of production in the applied art genres. As early as 1881, Gerlach engaged students from the Imperial-Royal School of Arts and Crafts, including Gustav and Ernst Klimt and Franz Matsch, in addition to such renowned artists as Wilhelm von Kaulbach, Max Klinger, Franz von Stuck, and Julius Victor Berger. The portfolio was to contain “original designs by the most outstanding modern artists.” In the context of this collaboration, Gustav Klimt was perceived by the press as an individual personality outside the “Künstler-Compagnie” for the first time in his career. The reviews were ambivalent: some were full of praise, others negative.

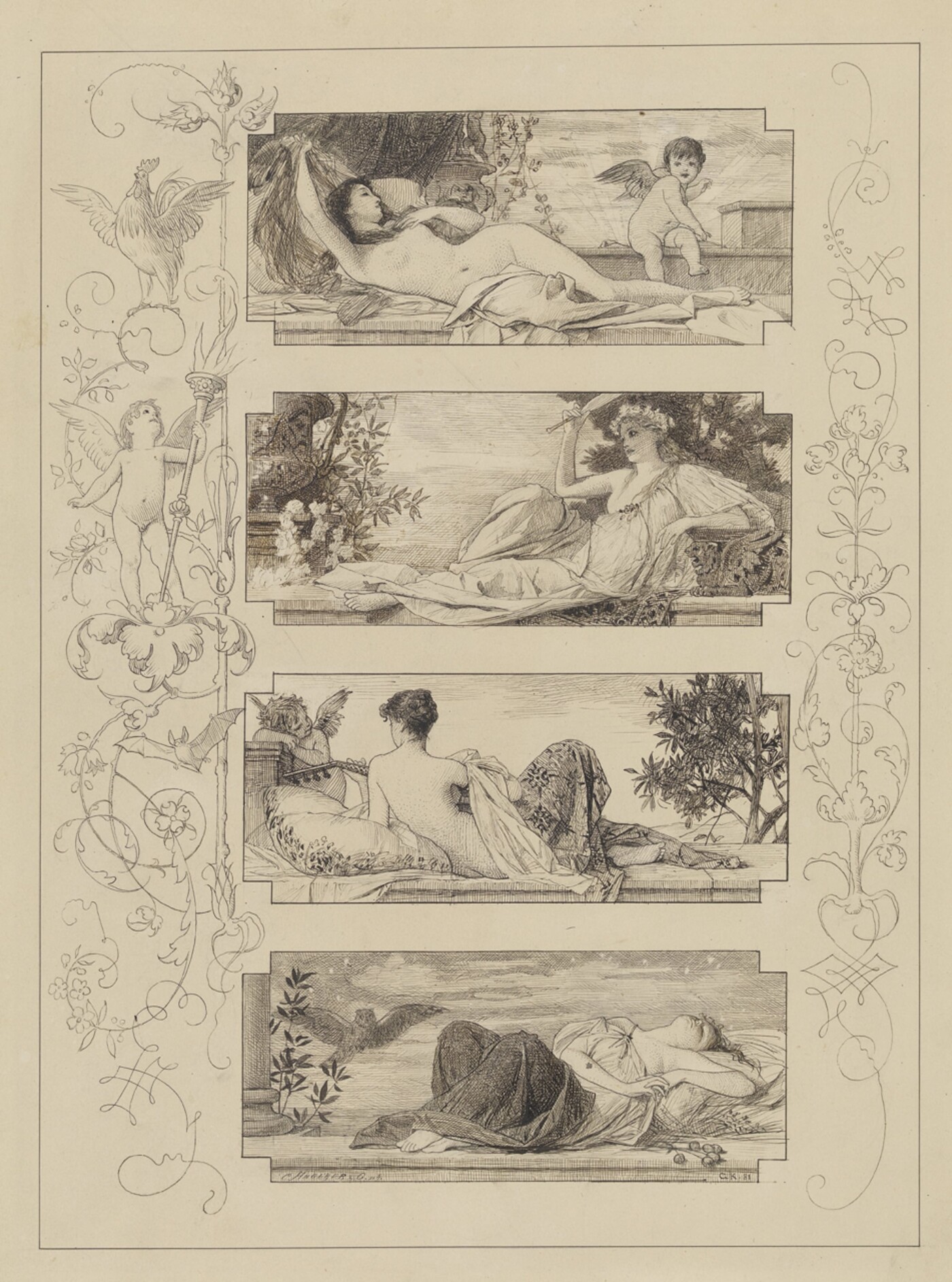

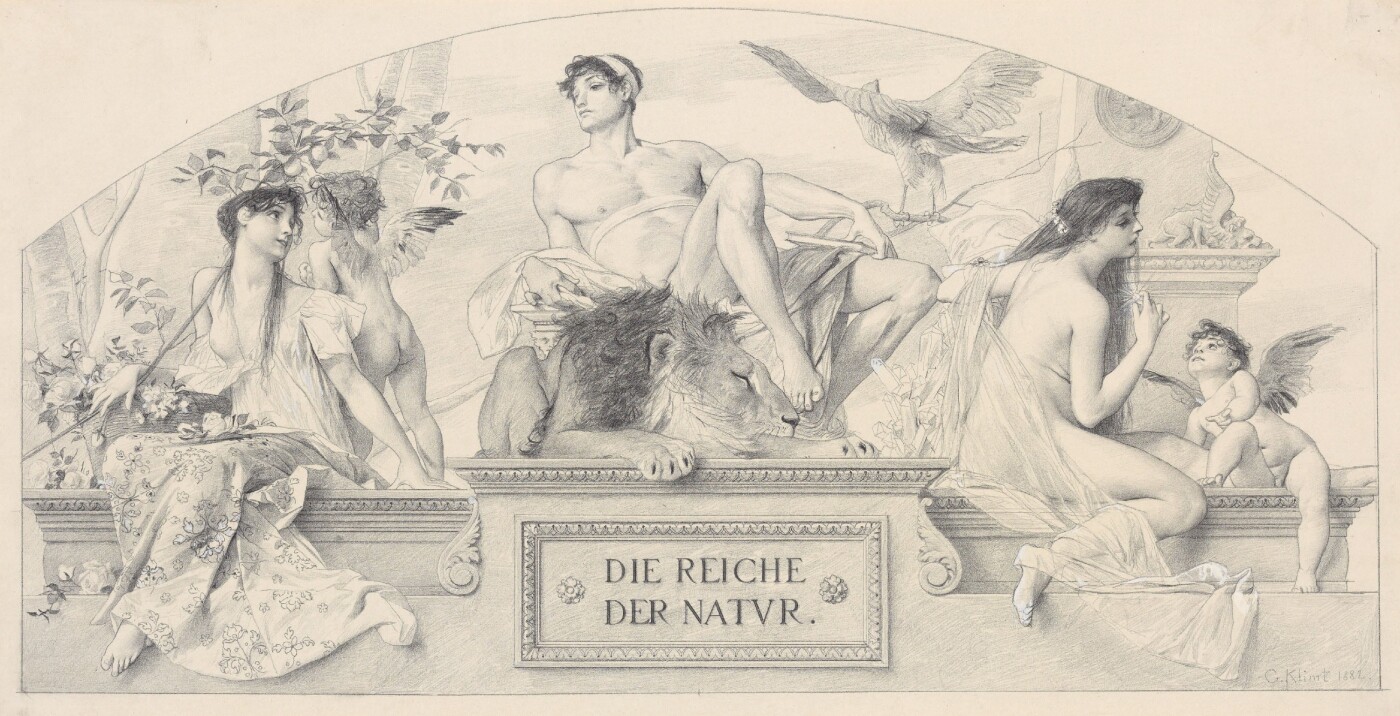

Gustav Klimt’s contributions to the portfolio comprised the drawings The Times of the Day (1881, Wien Museum, Vienna), which was based on the borders of the prayer book of Emperor Maximilian I (1513, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich), The Realms of Nature (1882, Wien Museum, Vienna), Youth (1882, Wien Museum, Vienna), Opera (1883, Wien Museum, Vienna), and Fairy-Tale (1884, Wien Museum, Vienna).

Gustav Klimt’s Contributions to Martin Gerlach’s “Allegorien und Embleme”

-

Gustav Klimt: The times of day (final artwork), 1881, Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: The times of day (final artwork), 1881, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum -

Gustav Klimt: The realms of nature (final artwork), 1882, Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: The realms of nature (final artwork), 1882, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum -

Gustav Klimt: Youth (final artwork), 1882, Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Youth (final artwork), 1882, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum -

Opera (final artwork), 1883, Wien Museum

Opera (final artwork), 1883, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum -

Fairy tale (final artwork), 1884, Wien Museum

Fairy tale (final artwork), 1884, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Allegory of Fable, 1883, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

The Oil Paintings Allegory of Fable and Allegory of Idyll

He also painted the two oil paintings Allegory of Fable (1883, Wien Museum, Vienna) and Allegory of Idyll (1884, Wien Museum, Vienna). In both works, the allegories were personified as idealized female figures. The personification of Fable holds a scroll in her right hand. She is accompanied by two pairs of animals, a lion with mice and a fox with a stork. Both motifs are borrowed from Aesop’s ancient fables and represent human behavior in the manner of parables.

For Allegory of Idyll, Gustav Klimt chose an architectural and figurative frame, which reminded contemporaries of Michelangelo’s ceiling in the Sistine Chapel. Klimt depicted the allegory of Idyll as a woman with children gathered around a nest filled with eggs. Like in Allegory of Fable, the landscape in the background is rendered as a cursory vista. Allegory of Idyll represents a picture within a picture, with a medallion surrounded by a floral wreath and held up by two muscular male nudes doubtlessly inspired by Michelangelo’s Ignudi (1508–1512, Sistine Chapel, Vatican City). They sit on a stone parapet bearing the title, a monogram and the date.

The original designs for Allegorien und Embleme were presented to a Viennese audience at the Vienna Künstlerhaus in 1885 within the framework of the “Exhibition of the Complete Original Drawings, Oil Sketches and Watercolors from the Edition de luxe Allegories and Emblems, edited by Martin Gerlach with the Gerlach and Schenk publishing house.”

Gustav Klimt: Allegory of Idyll, 1884, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

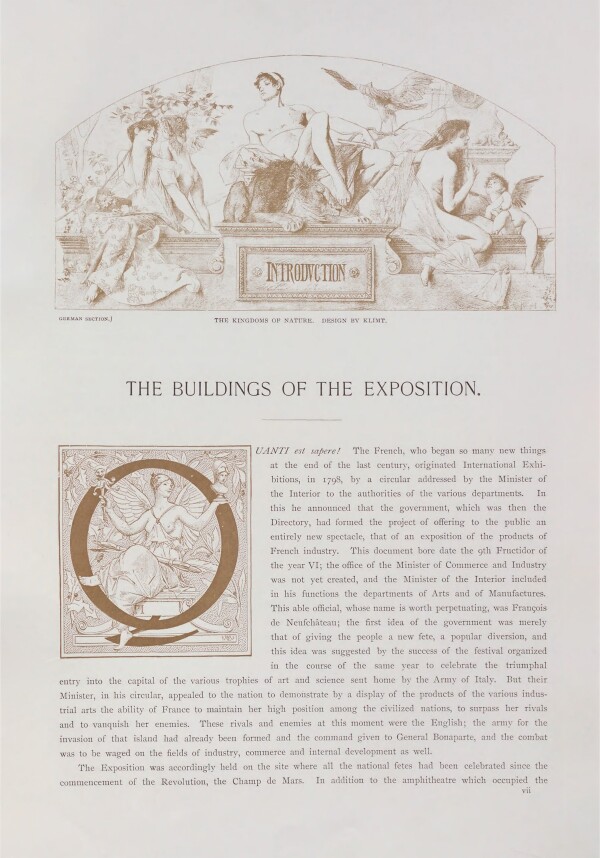

William Walton: Chefs-d’œuvre de l’Exposition Universelle de Paris, Sonderband »Introduction«, Paris - Philadelphia 1889.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

International Coverage and Dissemination

Moreover, the portfolio was presented in an international context for the first time at the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1889, where it was on view in the “German section.” Paul Schönfeld, a critic of the Kunstchronik, referred to Klimt’s allegories as

“the best in the section of ‘Allegories,’ featuring figures in splendid early Renaissance frames by Gustav Klimt [...], in which mature youth is represented, although not as allegories in the strict sense, but more in the way Titian treated his “Sacred and Profane Love” [...], the best of the collection in compositional terms being the representation of the ‘Realms of Nature’ by G. Klimt in Vienna.”

The American painter and art writer William Walton had also become aware of the two allegories by Gustav Klimt and included them in his exhibition guide “Chefs-d’œuvre.” In the introductory section, he used The Realms of Nature, adapting the presentation to his needs by changing the inscription on the plaque from “The Realms of Nature” to “Introduction,” the subtitle of the volume in question. In the second volume, Walton eventually also depicted Allegory of Idyll. Thus, these two works were the first works by Klimt to be disseminated beyond the German-speaking world.

Literature and sources

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007.

- Paul Schönfeld: Allegorien und Embleme, in: Kunstchronik. Wochenschrift für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, 19. Jg., Heft 3 (1883), Spalte 38-41.

- Colin B. Bailey (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Modernism in the Making, Ausst.-Kat., National Gallery of Canada (Ottawa), 15.06.2001–16.09.2001, Ottawa 2001.

- William Walton: Chefs-d’œuvre de l’Exposition Universelle de Paris, 2. Lieferung, Paris - Philadelphia 1889, S. 10.

- William Walton: Chefs-d’œuvre de l’Exposition Universelle de Paris, Sonderband »Introduction«, Paris - Philadelphia 1889, S. VII.

- Genossenschaft der bildenden Künstler Wiens (Hg.): Katalog der Ausstellung sämmtlicher Original-Zeichnungen. Oelskizzen und Aquarelle zu dem Prachtwerke: "Allegorien und Embleme" herausgegeben von Martin Gerlach im Verlage von Gerlach & Schenk Wien, Ausst.-Kat., Artists' House (Vienna), 21.06.1885–31.08.1885, Vienna 1885.

Drawings and Watercolors

Fairy tale (final artwork), 1884, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

The majority of drawings in Gustav Klimt’s early oeuvre were created as sketches and studies for decorative commissions. Only very few of these works on paper are considered autonomous artworks, among them the gouache Auditorium of the Old Burgtheater which Klimt created as a commission for the City of Vienna.

Klimt created his early pencil and ink drawings primarily as detailed studies for figures, draperies and accessories for the decorative commissions carried out by the “Künstler-Compagnie.” Thus, most of them were executed merely as fleeting sketches. An exception is the 1884 fine-drawing of the rendering Fairytale (Wien Museum, S 1980: 93) which was created as a template for the publication Allegorie und Embleme. This work on paper, executed using black chalk and India ink, boasts an autonomous, fully formulated pictorial composition in the medium of drawing.

Watercolors as Color Studies

Watercolors only play a minor role in Gustav Klimt’s graphic oeuvre. In the very few extant watercolored drawings, the artist tried out color effects through the use of watercolors.

Worth mentioning in this context is a sketch for a theater curtain (c. 1883, Wien Museum) whose exact period of creation is not entirely clear. There is also a small-scale extant watercolor based on Old Masters from the Kunsthistorisches Museum: Copy after St. Justina by Moretto da Brescia (c. 1883–85, private collection S 1980: 111). This work was likely either created as part of his training at the Imperial-Royal School of Arts and Crafts, or as a small preliminary color study for the large-scale oil copies that he executed from 1883 to 1885 for the King of Romania. What we know for sure is that Klimt used the pattern of the brocade fabric for his commission for the Karlovy Vary City Theater.

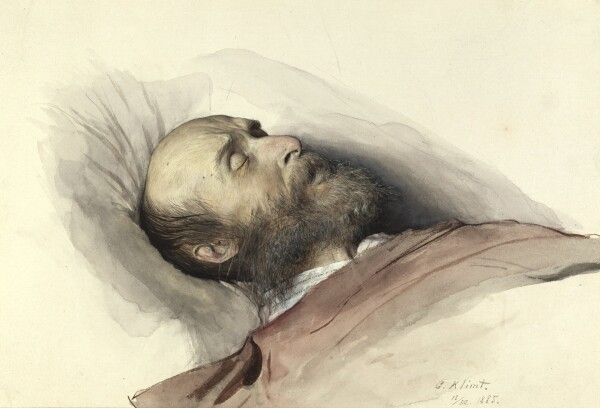

Gustav Klimt: Rudolf von Eitelberger on his Deathbed, 1885, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Death Portraits

Between 1883 and 1888, Klimt created two watercolors which represent independent artworks rather than color studies for planned oil paintings. Both depictions were executed in the tradition of death portraits. The portraits Julius Lott on his Deathbed (1883, Wien Museum, S 1980: 113) and Rudolf von Eitelberger on his Deathbed (1885, Wien Museum, S 1980: 112) are characteristic of Klimt’s drawing style of those years. The three-dimensional and detailed rendering of the heads suggests that Klimt worked from photographs, as he often did already during his early years as a student. The watercolors’ naturalistic style would also become characteristic of the oil portraits Klimt created over the following years, which increasingly earned him the reputation of a renowned portraitist.

Gustav Klimt: Auditorium of the Old Burgtheater, 1888, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

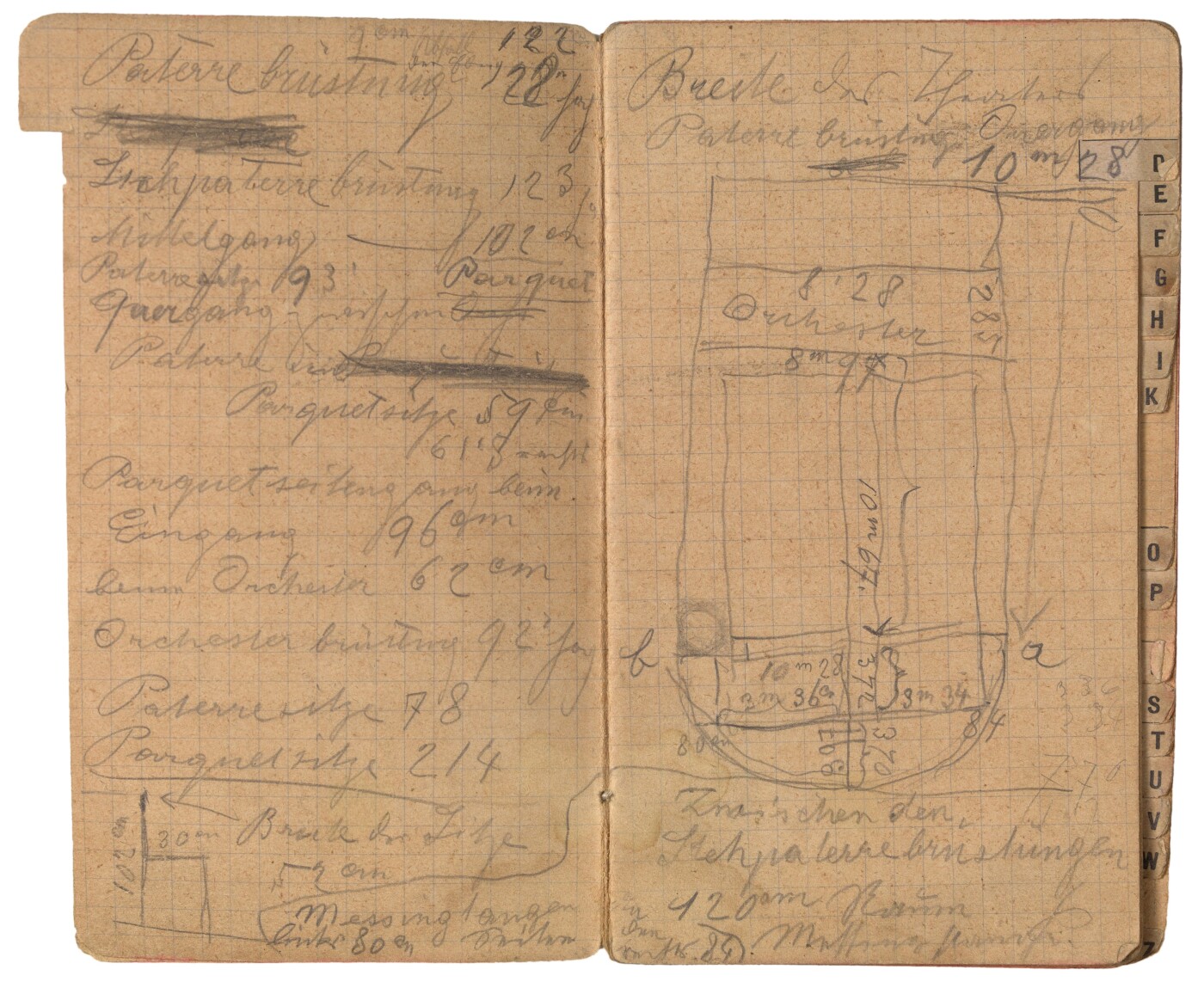

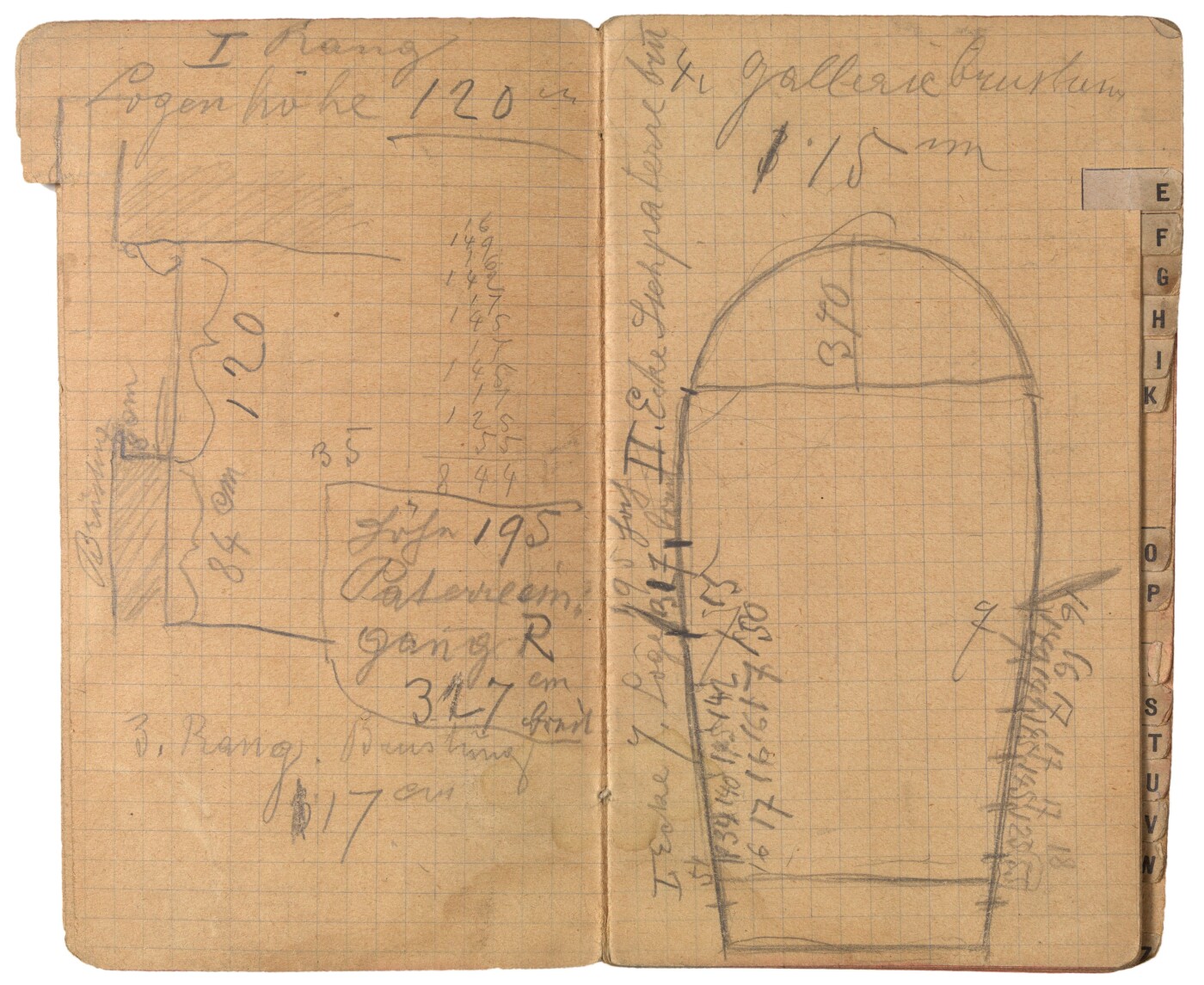

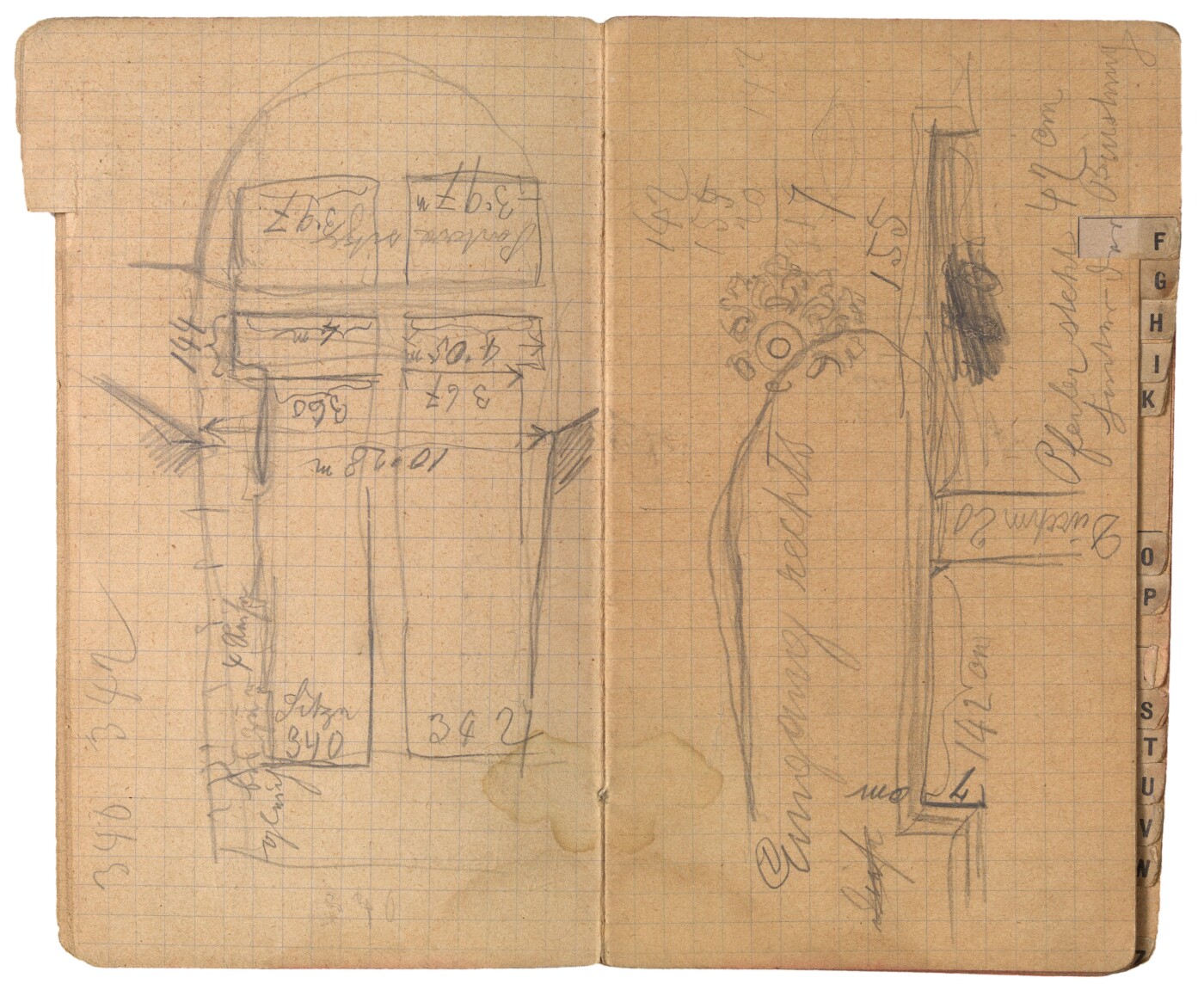

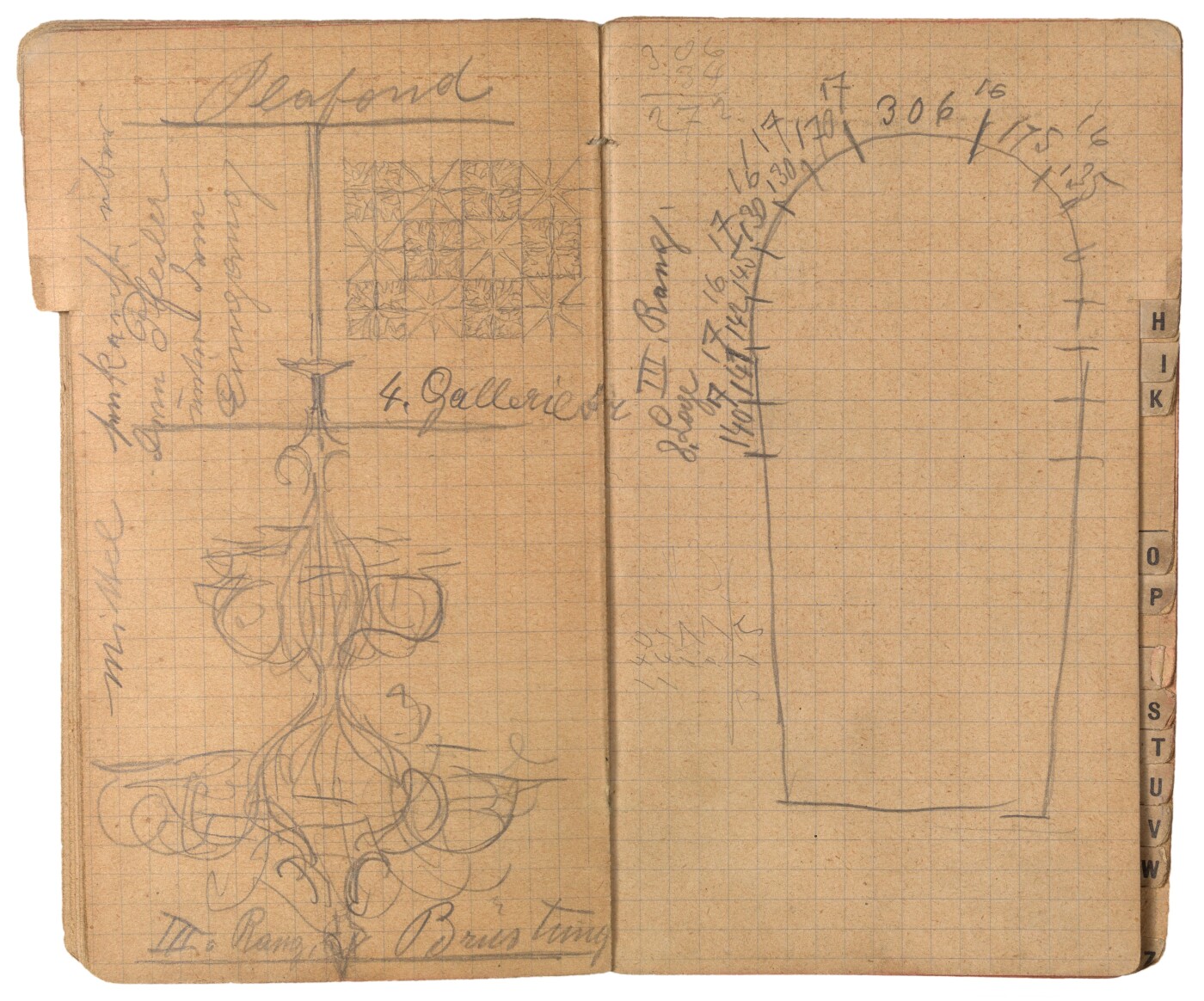

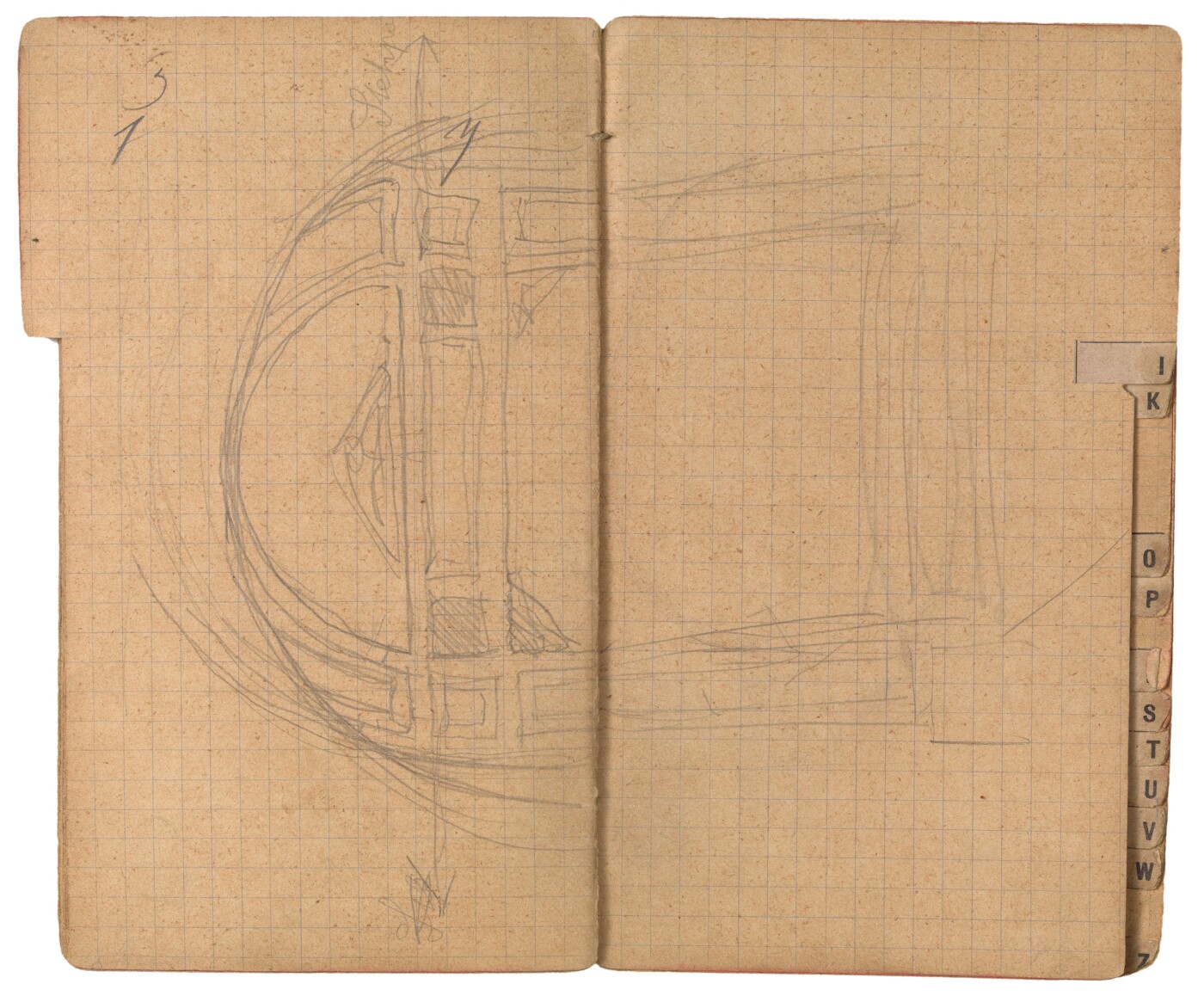

Individual Pages from one of Klimt’s Sketchbooks from 1888/89

-

Gustav Klimt: Sketchbook by Gustav Klimt (auditorium in the old Burgtheater), 1888-1889, Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Sketchbook by Gustav Klimt (auditorium in the old Burgtheater), 1888-1889, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum -

Gustav Klimt: Sketchbook by Gustav Klimt (auditorium in the old Burgtheater), 1888-1889, Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Sketchbook by Gustav Klimt (auditorium in the old Burgtheater), 1888-1889, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum -

Gustav Klimt: Sketchbook by Gustav Klimt (auditorium in the old Burgtheater), 1888-1889, Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Sketchbook by Gustav Klimt (auditorium in the old Burgtheater), 1888-1889, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum -

Gustav Klimt: Sketchbook by Gustav Klimt (auditorium in the old Burgtheater), 1888-1889, Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Sketchbook by Gustav Klimt (auditorium in the old Burgtheater), 1888-1889, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum -

Gustav Klimt: Sketchbook by Gustav Klimt (auditorium in the old Burgtheater), 1888-1889, Wien Museum

Gustav Klimt: Sketchbook by Gustav Klimt (auditorium in the old Burgtheater), 1888-1889, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Franz Matsch sen.: The interior of the Altes Burgtheater, 1888 (Heliogravure)

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Auditorium of the Old Burgtheater

Gustav Klimt’s first successful easel painting was not an oil painting but the gouache Auditorium of the Old Burgtheater (1888, Wien Museum, Vienna, S 1980: 191). In 1888, Franz Matsch and Gustav Klimt had been commissioned by the City of Vienna to document the interior of the old Burgtheater, which was scheduled to be demolished before the autumn of 1888. While Matsch rendered the view of the stage, Klimt depicted the auditorium. In this meticulous rendering of the theater’s interior, Klimt portrayed 133 famous Viennese personalities. Among the depicted are the actress Katharina Schratt, the later major of Vienna Karl Lueger, the composer Johannes Brahms, the physician Theodor Billroth, the architect Hasenauer with his family, as well as many of Klimt’s later commissioners and patrons.

For the up-and-coming artist, the watercolor Auditorium of the Old Burgtheater represented a resounding success with critics and audiences alike. The gouache was so popular that numerous heliogravures of it were distributed. The drawing, executed with mixed media, was exhibited in 1890 at the Künstlerhaus and won the Emperor’s Prize. However, the gouache would be the first and last graphic work by Klimt to win an award.

Literature and sources

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band I, 1878–1903, Salzburg 1980, S. 69-71.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007.

- Dr. A.N.: Die Klim-Matsch'schen Gemälde aus dem alten Burgtheater, in: Österreichische Kunst-Chronik, Nummer 24 (1889), S. 701.

- Leopold Wolfgang Rochowanski: Intimes von Klimt, in: Neues Wiener Journal, 13.01.1929, S. 19.

- N. N.: Der Kaiser im neuen Rathause, in: Das Vaterland. Zeitung für die österreichische Monarchie, 30.12.1888, S. 4.

- Ursula Storch (Hg.): Klimt. Die Sammlung des Wien Museums, Ausst.-Kat., Vienna Museum (Vienna), 16.05.2012–07.10.2012, Vienna 2012.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco (Hg.): Gustav Klimt und die Künstler-Compagnie, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 20.06.2007–14.10.2007, Weitra 2007.