Klimt's work focuses on all aspects of the Art Nouveau master's oeuvre. Visualized through a timeline, Klimt's creative periods are rolled up here, starting with his training, his collaboration with Franz Matsch and his brother Ernst in the "Künstler-Compagnie", the affair surrounding the faculty paintings and his post-fame and the myth that still surrounds this exceptional artist today.

Klimt Today

→

Lilya Corneli: Lady with fan (Modern reception), 2019

© tobeamuse

Klimt = Restitution?

The most spectacular cases of restitution in Austria over the last twenty years have involved works by Gustav Klimt. His name is almost symbolic of art restitution, with “Golden Adele” as the perfect icon, as this opulent work, like no other, is emblematic of the treasures the National Socialists had stolen from Jewish owners.

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, 1907, Neue Galerie New York, Acquired through the generosity of Ronald S. Lauder, the Heirs of the Estates of Ferdinand and Adele Bloch-Bauer, and the Estée Lauder Fund

© APA-PictureDesk

Klimt at the Albertina

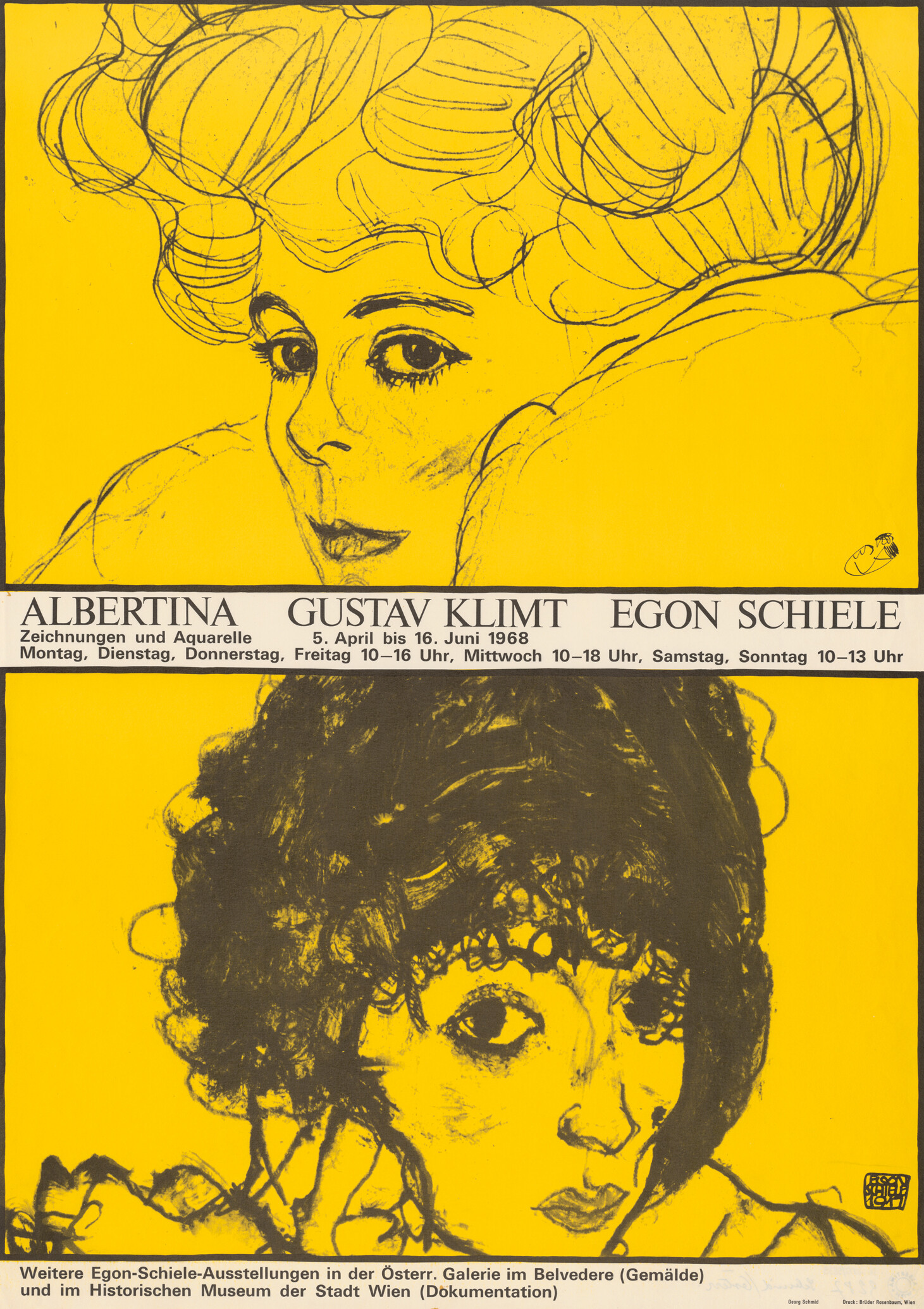

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the deaths of Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele in 1968, the Albertina in Vienna devoted a comprehensive memorial exhibition to these two exceptional artists. The exhibition was complemented by a show curated by Christian M. Nebehay, which dealt with Klimt’s life in a documentary fashion.

To the chapter

→

Poster of the memorial exhibition on the 50th anniversary of the deaths of Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele at The Albertina Museum, 1968

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

Exhibitions on Klimt’s 100th Birthday

To mark the 100th anniversary of Gustav Klimt’s birthday in 1962, museums in Graz and Vienna organized large-scale retrospectives. The start was made in Graz with works from Styrian collections. This was followed by two commemorative exhibitions in autumn organized by the Belvedere and the Albertina in Vienna, which presented altogether 29 paintings and 246 drawings.

To the chapter

→

The Albertina Museum photographed by Bruno Reiffenstein, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

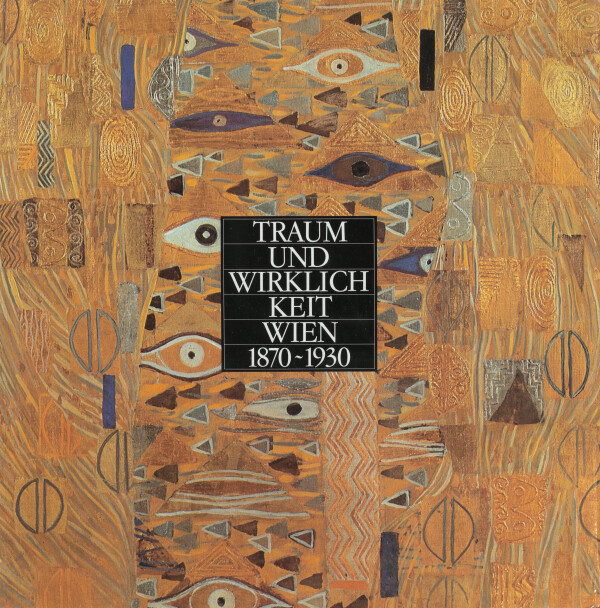

Dream and Reality

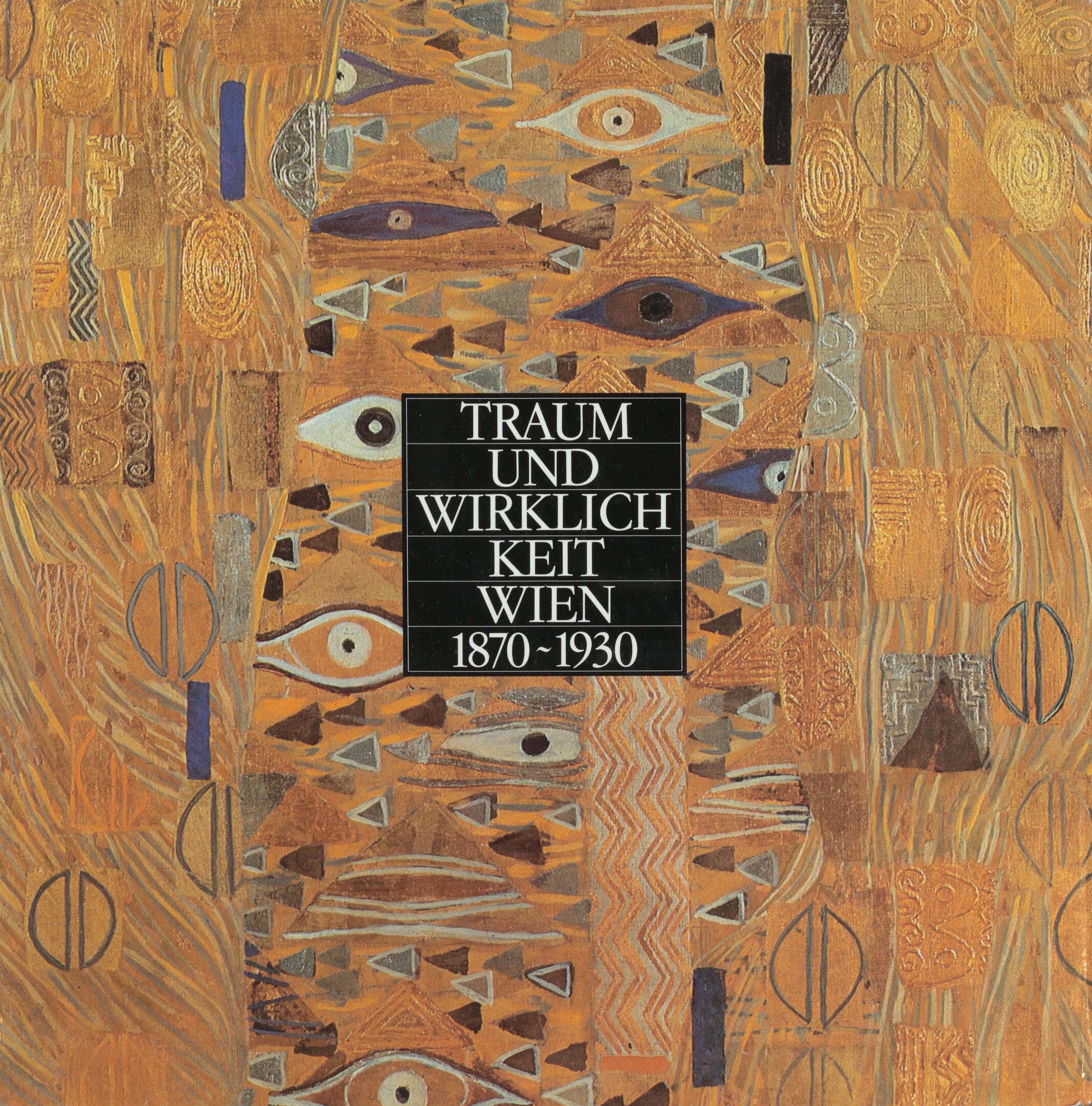

In 1985, the temporary exhibition “Traum und Wirklichkeit. Wien 1870–1930” [“Dream and Reality. Vienna 1870–1930”], devoted to said epoch’s art and cultural history, took place at the Vienna Künstlerhaus. Gustav Klimt’s work and network in fin-de-siècle Vienna were among the focal points of the show.

To the chapter

→

Robert Waissenberger (Hg.): Traum und Wirklichkeit. Wien 1870–1930, Ausst.-Kat., Museums of the City of Vienna (Vienna), 28.03.1985–06.10.1985, Vienna 1985.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

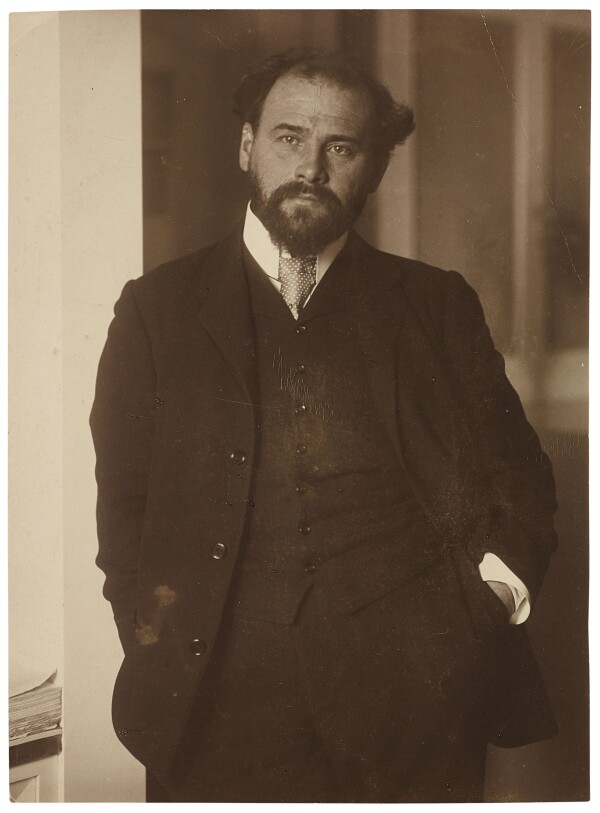

Anniversaries

Gustav Klimt’s oeuvre and the history of its reception, his sources of inspiration, his contemporaries, but also the person behind the artist have continuously been presented to the public in exhibitions at home and abroad. Anniversaries marking the birth or death of this artist of a century provide special opportunities.

To the chapter

→

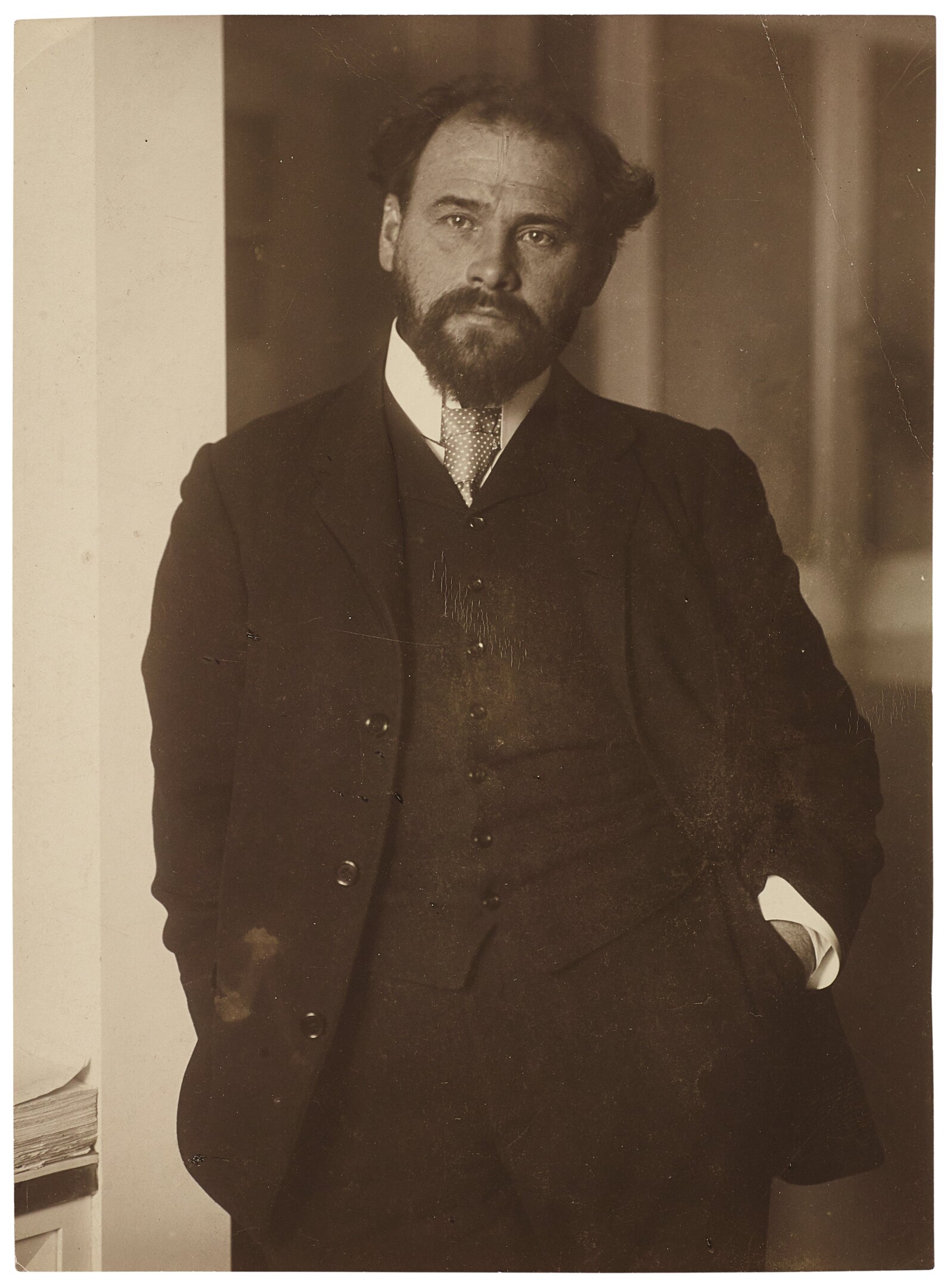

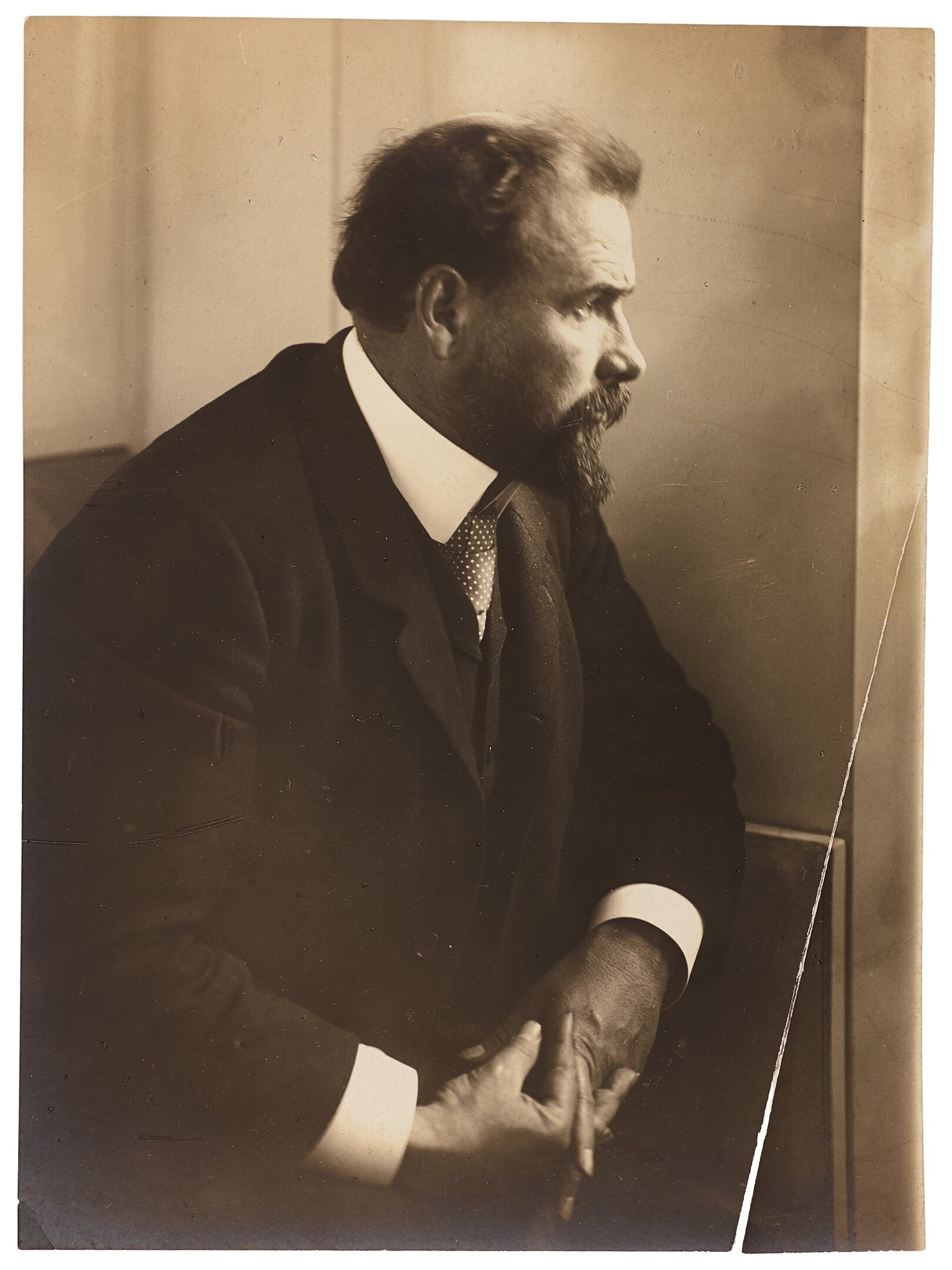

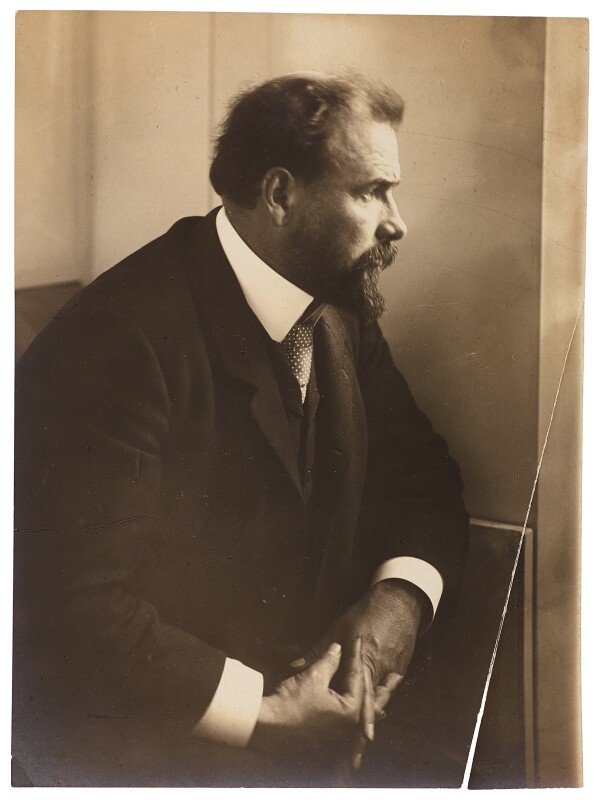

Gustav Klimt, 1910, ARGE Sammlung Gustav Klimt, Dauerleihgabe im Leopold Museum, Wien

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

The Catalogue Raisonné as a Tool for Provenance Research

Every scholarly examination of Gustav Klimt’s oeuvre begins with the catalogues raisonnés. They deal with questions of authenticity, exhibition history, ownership, and references in literature. Only then is it possible to gain an overview of the artist’s complete oeuvre.

To the chapter

→

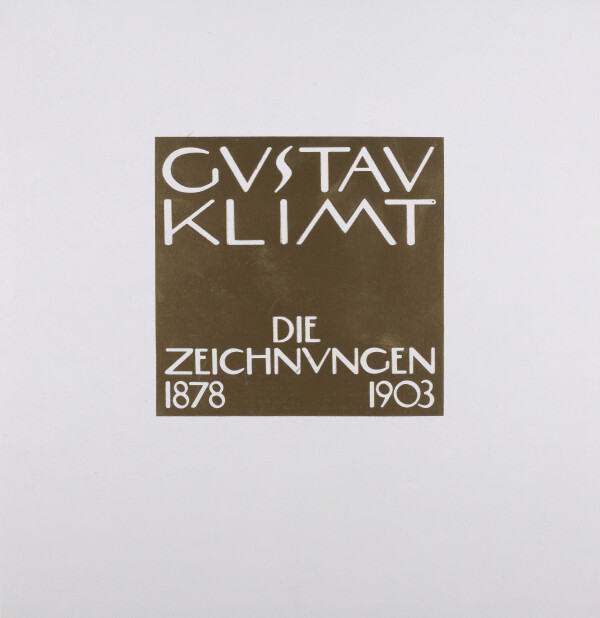

Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band I, 1878–1903, Salzburg 1980.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Klimt in Film and Theater

Gustav Klimt and his work have long been considered apt to please the masses, which also applies to the world of film and theater. In recent years, numerous national and international productions have dealt with the life and work of this exceptional artist, as is evidenced by the following selection, with reality and fiction closely interwoven

To the chapter

→

Gustav Klimt, 1910, ARGE Sammlung Gustav Klimt, Dauerleihgabe im Leopold Museum, Wien

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

Klimt Today

→

Lilya Corneli: Lady with fan (Modern reception), 2019

© tobeamuse

Klimt = Restitution?

Gustav Klimt: Forester's House in Weissenbach on the Attersee I, 1914, private collection

© Belvedere, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Water Snakes II, 1904, private collection

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Apple Tree II (Green Apple Tree), 1916, private collection

© Bridgeman Images

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, 1907, Neue Galerie New York, Acquired through the generosity of Ronald S. Lauder, the Heirs of the Estates of Ferdinand and Adele Bloch-Bauer, and the Estée Lauder Fund

© APA-PictureDesk

The most spectacular cases of restitution in Austria over the last twenty years have involved works by Gustav Klimt. His name is almost symbolic of art restitution, with “Golden Adele” as the perfect icon, as this opulent work, like no other, is emblematic of the treasures the National Socialists had stolen from Jewish owners.

With its 1998 Art Restitution Act, Austria is considered an international forerunner in the field of art restitution. This law provides for the in rem restitution of objects that were confiscated by the National Socialists and not returned after 1945. It relates exclusively to federal property, although some federal states and municipalities have introduced similar regulations, following the example of the federal government. Private collections are not subject to the Art Restitution Act. As an alternative to restitution in kind, attempts are made to reach an agreement by means of settlements and compensation payments. Although this is done on a voluntary basis, it is now a prerequisite for placing an object on the art market or for it to be lent to exhibitions.

A drawing by Gustav Klimt from the Albertina was handed over to the heirs of Siegfried and Irma Kantor in 1999, the very first year of the Austrian Art Restitution Advisory Board’s activities.

In 2000, the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere restituted Apple Tree II (Green Apple Tree) (1916, private collection) to the heirs of Nora Stiasny. Doubts as to whether Stiasny’s collection was the correct one were confirmed in 2017: the painting originally came from the Lederer Collection and should actually have been restituted to its heirs. To date, this is the only known case of restitution from an Austrian federal museum to the wrong heirs.

According to a decision of 10 October 2000, the heirs of Jenny Steiner received the painting Forester’s House in Weißenbach on the Attersee I (1914, private collection) from the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere. In 2013, a settlement was reached with the same heirs for the privately owned painting Water Snakes II (1904, reworked before 1908, private collection).

As with Apfelbaum II, paintings from the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere that had been donated by Gustav Ucicky were restituted, such as Farm House with Birch Trees (1900, private collection), which was returned to the heirs of Hermine Lasus in 2001, and Lady en face in a Pleated Dress (c. 1898, private collection), which went to the heirs of Bernhard Altmann in 2004. Portrait of Gertrud Loew (1902, The Lewis Collection), which had remained in Ucicky’s private collection, was the subject of an out-of-court settlement between the Klimt-Foundation and the heirs of Gertrud Felsövanyi in 2014.

Although the “Golden Adele” – Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907, Neue Galerie New York) – was state-owned, this painting was restituted in 2006 according to the ruling of an arbitration tribunal specifically set up for this purpose instead of following a decision by the Art Restitution Advisory Board.

In 2015, the Beethoven Frieze (1901/02, Belvedere, Vienna) from the Serena Lederer Collection received almost as much media attention as “Golden Adele,” but was not restituted according to the decision of the Art Restitution Advisory Board. The works Portrait of Amalie Zuckerkandl (1913/14, unfinished, Belvedere, Vienna) and Poppies in Bloom (1907, Belvedere, Vienna) also remained in the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, based on the Art Restitution Advisory Board’s relevant decisions.

This list is by no means complete, but it shows the importance of Gustav Klimt’s oeuvre in the policy and practice of restitution in Austria.

Exhibitions on Klimt’s 100th Birthday

To mark the 100th anniversary of Gustav Klimt’s birthday in 1962, museums in Graz and Vienna organized large-scale retrospectives. The start was made in Graz with works from Styrian collections. This was followed by two commemorative exhibitions in autumn organized by the Belvedere and the Albertina in Vienna, which presented altogether 29 paintings and 246 drawings.

Memorial Exhibition in Graz

The Neue Galerie at the Landesmuseum Joanneum Graz (now Universalmuseum Joanneum) presented the “Gedächtnis-Ausstellung aus Anlass des 100. Geburtstages von Gustav Klimt mit Werken aus privatem und öffentlichem Besitz in [der] Steiermark” [“Memorial Exhibition on the Occasion of the 100th Birthday of Gustav Klimt with Works from Public and Private Collections in Styria”] from 22 June to 22 July 1962. The show comprised altogether 51 exhibits, including seven oil paintings from a private collection in Graz, 43 drawings, and a letter from Klimt to Ludwig König of 6 December 1901.

In the show, Danaë (1907/08, private collection), a masterpiece from the Golden Period, and several late landscapes – Church in Cassone on Lake Garda (1913, private collection), Church in Unterach on the Attersee (1915/16, Heidi Horten Collection, Vienna), Orchard with Roses (1912, private collection), “Garden” (now Apple Tree II [Green Apple Tree]) (1916, private collection), Houses in Unterach on the Attersee (1915/1916, private collection), and “Park in Schönbrunn” (now Schönbrunn Landscape [1916, private collection]) – were complemented by Altar of Dionysus (Study) (1886, Leopold Museum, Vienna) and The Black Feathered Hat (1910, private collection). Important loans primarily came from the art collection of the Graz-based merchant Viktor Fogarassy.

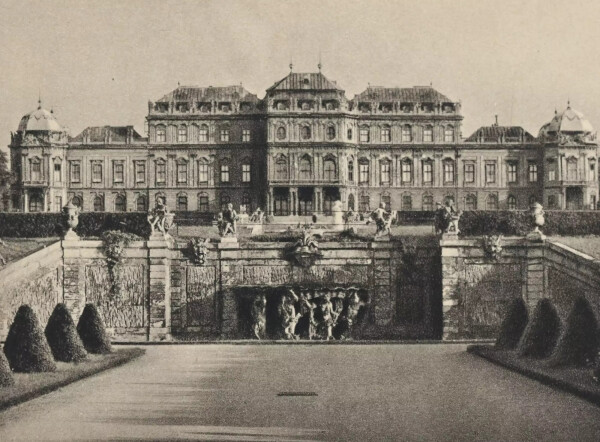

Upper Belvedere, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Retrospective at the Belvedere, Vienna

From 15 October to 16 December 1962, the Österreichische Galerie in Vienna (now Belvedere) presented a retrospective dedicated to the artist of the century that was entitled “29 Gemälde von Gustav Klimt, ausgestellt im Oberen Belvedere aus Anlass der 100. Wiederkehr seines Geburtstages” [“29 Paintings by Gustav Klimt Exhibited at the Upper Belvedere on the Occasion of the 100th Anniversary of His Birthday”]. Out of the altogether almost thirty works on display, ten came from private collections. The highlight of the show was Klimt’s masterpiece The Kiss (Lovers) (1908/09, Belvedere, Vienna), which had been acquired for the museum’s forerunner, the Modern Gallery, as early as 1908 in the context of the “Kunstschau Wien.” Around it, exhibition curator Fritz Novotny, the museum’s director, grouped various important portraits, landscapes, and allegories. The objects, dating from all of the artist’s periods, offered a comprehensive overview of Klimt’s work. Even if the show could not claim to present his entire oeuvre – the Stoclet Frieze (1905–1911, private collection) was not publicly accessible, the former Lederer Collection, including the Faculty Paintings, had been destroyed in 1945, and many paintings in private collections were not available – the works compiled conveyed an overall impression of Klimt’s artistic development.

In his foreword to the catalog, Novotny described Klimt’s stylistic evolution as a “dominant principle of form” brought about by the replacement of naturalism through ornament. He emphasized the ornamentalism in Klimt’s work, which came to prevail more and more until the artist’s death in 1918. For Novotny, this, “together with appropriate conceptual and symbolic content,” resulted in the “pure expression of the Secessionist style.”

The Albertina Museum photographed by Bruno Reiffenstein, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Retrospective at the Albertina, Vienna

The Albertina’s Klimt retrospective, succinctly entitled “Gustav Klimt 1862–1918. Zeichnungen” [“Gustav Klimt 1862–1918. Drawings”] was held under the motto of Klimt’s “break with Historicism.” The core of the exhibition was thus made up of the progressive studies for the Faculty Paintings and the Beethoven Frieze (1901/02, Belvedere, Vienna). Ten drawings from the collection of Erich Lederer and four from the personal collection of the art dealer Christian M. Nebehay complemented the Albertina’s ample holdings. In the exhibition rooms, the objects were arranged chronologically as well as grouped according to motifs: drawings from the years 1902–1906 were followed by studies for portraits in oil, including those of Adele Bloch-Bauer, Hermine Gallia, Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein, and Fritza Riedler. The designs for the Stoclet Frieze – from the Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien (now Wien Museum, Vienna) and the related work drawings from the Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst (now MAK, Vienna) gave an impression of Klimt’s fusion of painting and applied art. Three book projects the illustrations of which were based on Klimt’s drawings were included in the show: the complete edition of Ver Sacrum, Franz Blei’s reedition of Lucian’s Dialogues of the Courtesans of 1907, and Paul Verlaine’s Femmes – avec 6 dessins de Gustav Klimt. Klimt’s personal environment was elucidated through various autograph documents. Klimt’s handwritten poem entitled Wasserrose [“Water Rose”], which was then still owned by Erich Lederer, was presented together with Schiele’s drawing Gustav Klimt on His Deathbed (7 February 1918, Wien Museum, Vienna) and one of Peter Altenberg’s dedications to the artist.

The comprehensive show and the Albertina’s first illustrated exhibition catalog produced in its context prompted curator Alice Strobl to begin her work on the four-volume catalogue raisonné published between 1980 and 1989, the most important reference work regarding Klimt’s drawings to this date.

Literature and sources

- Österreichische Galerie Belvedere (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. 29 Gemälde, ausgestellt im Oberen Belvedere aus Anlass der 100. Wiederkehr seines Geburtstages, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 15.10.1962–16.12.1962, Vienna 1962.

- Neue Galerie Graz Landesmuseum Joanneum (Hg.): Gedächtnis-Ausstellung aus Anlass des 100. Geburtstages von Gustav Klimt. mit Werken aus privatem und öffentlichem Besitz in Steiermark, Ausst.-Kat., New Gallery Graz (Graz), 22.06.1962–22.07.1962, Graz 1962.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Ausst.-Kat., Albertina (Vienna), 16.10.1962–16.12.1962, Vienna 1962.

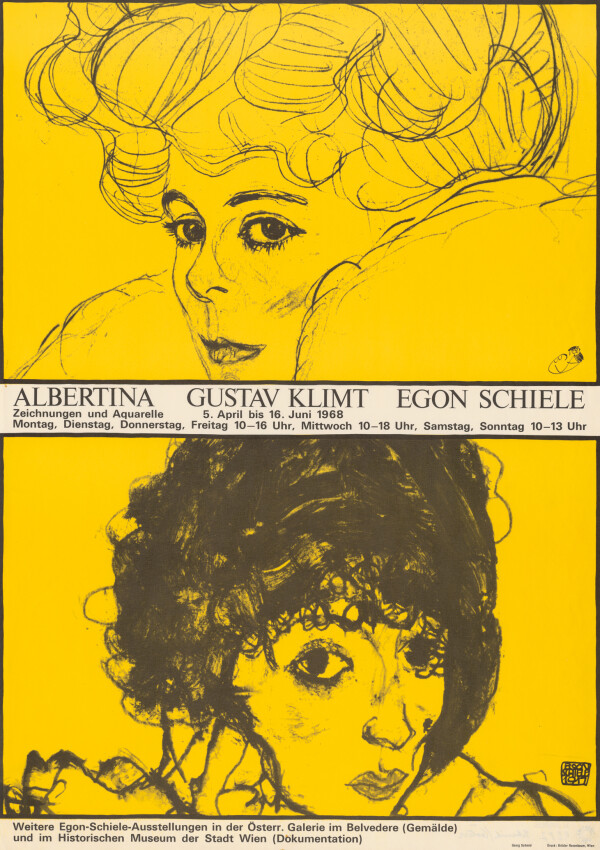

Klimt at the Albertina

Poster of the memorial exhibition on the 50th anniversary of the deaths of Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele at The Albertina Museum, 1968

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

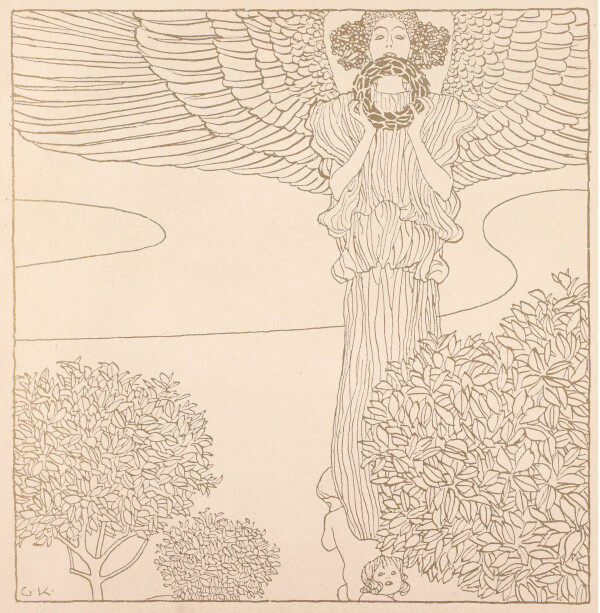

Gustav Klimt: Study for the dedication sheet for Rudolf von Alt on his 88th birthday, 1900, in: Vereinigung bildender KünstlerInnen Wiener Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Mitteilungen der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 3. Jg., Heft 21 (1900).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

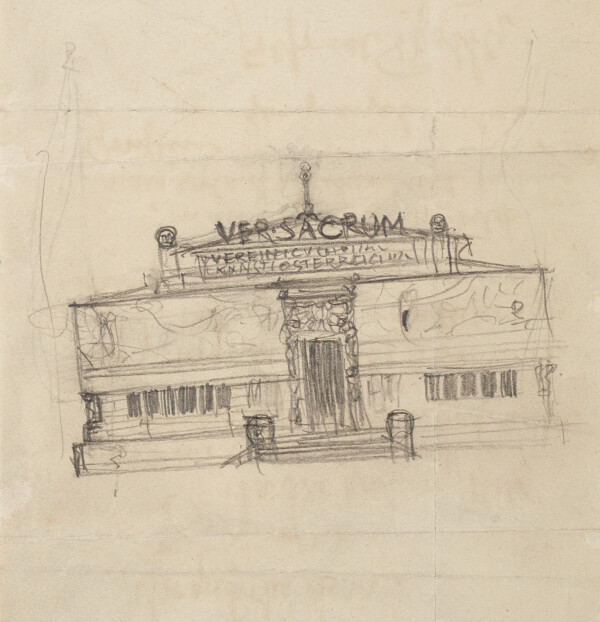

Alfred Roller: Letter from Alfred Roller to Gustav Klimt with a design sketch for the building of Gustav Klimt's Vienna Association , 05/04/1897, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the deaths of Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele in 1968, the Albertina in Vienna devoted a comprehensive memorial exhibition to these two exceptional artists. The exhibition was complemented by a show curated by Christian M. Nebehay, which dealt with Klimt’s life in a documentary fashion.

The “Major Creative Forces of Our Cultural World” United

The Albertina had already organized its first Klimt retrospectives in 1948, 1958, and 1962. A motivation for the thematic juxtaposition of Klimt and Schiele, these “major creative forces of our cultural world,” in the show of 1968 was not only that they tragically shared 1918 as their year of death. The two artists, who stood for different generations and whose paths had kept crossing, were to be presented to the public holistically, as they most perfectly embodied the diverging artistic expressions of Vienna around 1900.

Apart from drawings from the Albertina’s own collections, the show included international loans from Canada, the USA, and Switzerland, as well as from Austrian private collections. Alice Strobl and Erwin Mitsch were in charge as curators for Klimt and Schiele respectively. This exhibition was complemented by a Klimt documentation, which had been compiled by the art dealer and Klimt specialist Christian M. Nebehay at the invitation of then-director Walter Koschatzky and which was presented at a separate venue. In the following year, Nebehay published Gustav Klimt. Dokumentation, today a standard work for Klimt research.

The in-depth analysis of the drawings and their presentation at the Albertina entailed a detailed study of the artist’s extensive drawn oeuvre. Between 1980 and 1989, Strobl eventually published the four volumes of her catalogue raisonné of Klimt’s drawings, studies, and sheets of sketches.

The Exhibition Concept

The exhibition presented 127 works by Klimt, placing its focus on drawings of high quality still unknown. On the one hand, the selection comprised works introduced in such publications as Ver Sacrum during Klimt’s lifetime. On the other hand, it showcased drawings that had been considered worth presenting by personalities like Hermann Bahr, Gustav Glück, and Alfred Stix. These also included those drawings that had come out as facsimile collotype prints in 1919 in the portfolio Fünfundzwanzig Handzeichnungen. Gustav Klimt [“Twenty-Five Original Drawings. Gustav Klimt”], which had appeared with the Viennese publishing house Gilhofer & Ranschburg. Moreover, the display also featured works in techniques the artist hardly used, such as watercolors and pen and ink drawings. Klimt preferably resorted to pencil, colored pencil, and black chalk, which he frequently mixed and heightened with white. Another goal of this exhibition was to highlight various stylistic influences on Klimt’s drawn oeuvre. For example, the Albertina’s memorial show introduced to its audience models reminiscent of antiquity, which Klimt had harked back to time and again throughout his career. Another focal point was Klimt’s orientation on Japanese art – an influence observed not only in Klimt’s output but widely relied upon at the time. It manifests itself particularly clearly in Klimt’s drawings, as does the recurring reception of a special visual vocabulary that eventually also found its way into Klimt’s paintings. The show, which was mostly made up of portrait studies, also presented Klimt’s Design for the Building of the Vienna Secession of 1897 (Klimt-Foundation, Vienna, S 1980: 322), which was drawn on the reverse side of a letter from Alfred Roller to Klimt.

The Albertina’s show traced Klimt’s development from compositional studies reminiscent of classical models and drawings in which the language of form of Viennese Jugendstil impressively manifests itself to his late work, characterized by the well-versed processing of various inspirations gained, with simplification and metamorphosis culminating in the artist’s autonomous and unmistakable formal idiom.

The exhibition presented 156 drawings by Schiele visualizing his artistic development and a formal language embracing expression. Moreover, Schiele’s stylistic orientation on both Klimt’s art and Jugendstil was made obvious through the integration of drawings from the first decade of the 20th century. The most substantial difference in this respect was the polychromy that played an inherent role in young Schiele’s drawn oeuvre.

Not only did the exhibition brochure catalog the works by Klimt and Schiele. It was for the first time that the 1918 obituary Klimt. Ein Bild in Worten [“Klimt. A Painting in Words”] by the artist Albert Paris Gütersloh was published.

Besides the Albertina, the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere and the Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien (now Wien Museum, Vienna) honored Schiele with two shows in 1968, as is illustrated by the joint exhibition poster of these three institutions.

Literature and sources

- Walter Koschatzky (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Egon Schiele. Zum Gedächtnis ihres Todes vor 50 Jahren. Zeichnungen und Aquarelle, Ausst.-Kat., Albertina (Vienna), 05.04.1968–16.06.1968, Vienna 1968.

Dream and Reality

Robert Waissenberger (Hg.): Traum und Wirklichkeit. Wien 1870–1930, Ausst.-Kat., Museums of the City of Vienna (Vienna), 28.03.1985–06.10.1985, Vienna 1985.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Insight into the exhibition "Dream and Reality", presumably March 1985, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna

In 1985, the temporary exhibition “Traum und Wirklichkeit. Wien 1870–1930” [“Dream and Reality. Vienna 1870–1930”], devoted to said epoch’s art and cultural history, took place at the Vienna Künstlerhaus. Gustav Klimt’s work and network in fin-de-siècle Vienna were among the focal points of the show.

The mega exhibition “Traum und Wirklichkeit. Wien 1870–1930” [“Dream and Reality. Vienna 1870–1930”], organized by the Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien (now Wien Museum, Vienna), opened at the Vienna Künstlerhaus on 28 March 1985. The scholarly fundament of the show came from Robert Waissenberger, director of the Historisches Museum, while the Austrian architect and designer Hans Hollein was in charge of the visual concept. Hollein himself then commented upon the show in the exhibition catalog:

“The idea of this exhibition is based on the long-discussed necessity to finally also present an exhibition about this essential epoch in Vienna itself, following numerous attempts at other places, and benefit from the resources in situ.”

The exhibition comprised altogether 24 political, cultural, and historical “stations,” spanning from the Makart Parade of 1879 to the Great Depression of 1929. What mattered most to Hans Hollein was, in his own words, to present the topics in a popular, atmospheric, and experiential way. In addition to the numerous authentic exhibits, he also relied on such stylistic elements as reconstructions and models for the sake of an enhanced visualization. Hollein also provided an elaborate conception for the outer appearance of the Künstlerhaus. On the roof, he installed both a construction element of the Karl Marx Hof, a Viennese public housing estate, and an overdimensioned golden female figure extracted from Klimt’s Faculty Painting of Medicine (1900–1907, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945).

The Presentation of Gustav Klimt

Within the framework of the exhibition, a thematic chapter of its own was devoted to Gustav Klimt. Next to the painting The Kiss (Lovers) (1908/09, Belvedere, Vienna), the Beethoven Frieze was one of the most prominent exhibits of the Vienna show. The lengthy restoration of the work, which had been acquired by the Republic of Austria in 1972, had only been completed a short while ago.

From Vienna to Paris and New York

“Dream and Reality. Vienna 1870–1930” ended in October 1985. Having attracted 662,000 visitors, it has been one of the museum’s most successful shows to this day. It provided the basis for two major follow-up shows, “Vienne, Naissance d’un siècle, 1880–1938” and “Vienna 1900. Art. Architecture & Design.” They were to take place the subsequent years at the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Literature and sources

- Monika Sommer-Sieghart, Luisa Ziaja: Kulturhistorische Großausstellungen der 1980er Jahre im Künstlerhaus. Anmerkungen zu kuratorischen Kontinuitäten und Brüchen, in: Peter Bogner, Richard Kurdiovsky, Johannes Stoll (Hg.): Das Wiener Künstlerhaus. Kunst und Institution, Vienna 2015, S. 334-341.

- Sophie Lillie: Feindliche Gewalten: Das Ringen um Gustav Klimts Beethovenfries, Vienna 2017.

- Robert Waissenberger (Hg.): Traum und Wirklichkeit. Wien 1870–1930, Ausst.-Kat., Museums of the City of Vienna (Vienna), 28.03.1985–06.10.1985, Vienna 1985.

- Haus der Geschichte. www.hdgoe.at/traum-wirklichkeit (05/19/2022).

- Moma. Vienna 1900: Art, Architecture and Design. www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1729 (05/19/2022).

- Centre Pompidou (Hg.): Vienne. Naissance d'un sciècle 1880–1938, Ausst.-Kat., , Paris 1986.

- Kirk Varnedoe (Hg.): Vienna 1900. Art, Architecture and Design, Ausst.-Kat., , New York 1986.

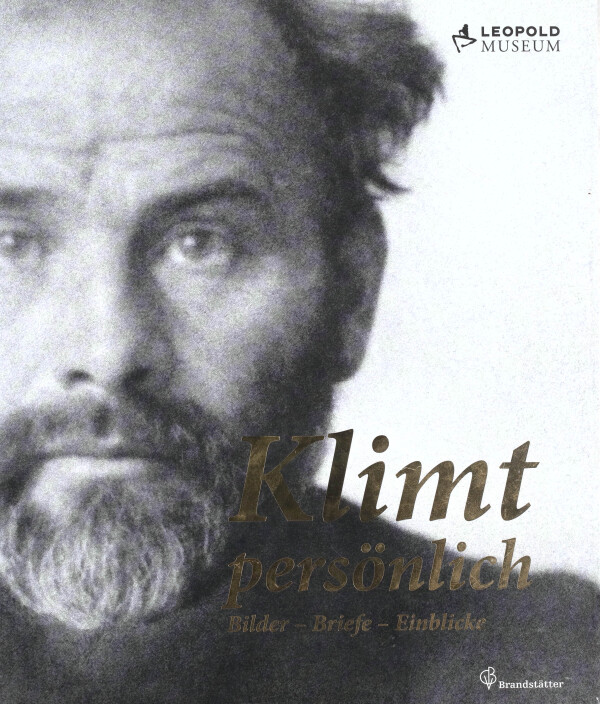

Anniversaries

Gustav Klimt, 1910, ARGE Sammlung Gustav Klimt, Dauerleihgabe im Leopold Museum, Wien

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

Gustav Klimt’s oeuvre and the history of its reception, his sources of inspiration, his contemporaries, but also the person behind the artist have continuously been presented to the public in exhibitions at home and abroad. Anniversaries marking the birth or death of this artist of a century provide special opportunities.

The Anniversary Year of 2012

In 2012, nine large-scale exhibitions to mark the 150th anniversary of Gustav Klimt’s birth visualized and conveyed various aspects of the life and work of the world-famous master of Jugendstil. The focus was both on the presentation and reception of individual masterpieces and the respective museums’ own holdings, on congenial collaborations and intimate insights into Klimt as a person.

The start was made in late 2011 with the exhibition “Gustav Klimt – Josef Hoffmann. Pioniere der Moderne” [“Gustav Klimt – Josef Hoffmann. Pioneers of Modernism”] at the Orangery of the Lower Belvedere. It featured the congenial collaboration between Klimt and Hoffmann, which manifested itself in the 1900 Paris World’s Fair, the famous “XIV. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession” [“14th Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists Secession”], also known as “Beethoven Exhibition,” and in the incunabulum of a Gesamtkunstwerk or universal work of art, the Stoclet Palace in Brussels.

The Kunsthistorisches Museum presented the exhibition “Gustav Klimt im Kunsthistorischen Museum” [“Gustav Klimt at the Kunsthistorisches Museum”]. The focus was on the wall paintings in the museum’s staircase, which Klimt had created around 1890/91 as a member of the “Künstler-Compagnie” and which are characteristic of his early decorative style. These permanent wall decorations could be viewed via the so-called “Klimt Bridge” especially installed for this purpose.

Klimt Bridge, erected on the occasion of the anniversary exhibition at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, 2012, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

© KHM-Museumsverband

Tobias G. Natter, Franz Smola, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Klimt persönlich. Bilder – Briefe – Einblicke, Ausst.-Kat., Leopold Museum (Vienna), 24.02.2012–27.08.2012, Vienna 2012.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

In the exhibition “Klimt persönlich” [“Klimt: Up Close and Personal”], the Leopold Museum once again shed light not only on the work of the Jugendstil master, but also on the person behind the artist, his joys, fears, distractions, and curses. In addition to the paintings from the museum’s own collection, the presentation included some 400 postcards sent by Klimt to Emilie Flöge, his soulmate. They provided deep insights into his personal feelings.

In “Gegen Klimt. Die ‘Nuda Veritas’ und ihr Verteidiger Hermann Bahr” [“Against Klimt. ‘Nuda Veritas’ and Her Defender Hermann Bahr”], the Vienna Theatermuseum focused on the “naked truth.” This work was supplemented by statements from advocates and dispraisers of Klimt's art.

Klimt’s works on paper were in the focus of the Albertina’s exhibition “Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen” [“Gustav Klimt. The Drawings”], which was also shown at the Getty Museum that same year under the title of “Gustav Klimt: The Magic of Line.”

The exhibition at the Vienna MAK – Museum für angewandte Kunst, “Gustav Klimt: Erwartung und Erfüllung” [“Gustav Klimt: Expectation and Fulfillment”] was devoted to the extensive designs for one of the most striking milestones in the work of the painter genius: the Stoclet Frieze (1905–1911, private collection), made for the dining room of the Stoclet Palace in Brussels. Following restoration, the drawings – a total of nine single large-format sheets – were presented to the public. Additional objects complementing the exhibition placed its focus on the Stoclet Palace as a Gesamtkunstwerk or universal work of art.

In “Klimt. Die Sammlung des Wien Museums” [“Klimt. The Collection of the Wien Museum”], the Wien Museum presented an overview of its own Klimt holdings. In addition to paintings, drawings, posters and portrait photographs, Klimt’s death mask was also on display.

Apart from the aforementioned juxtaposition of Klimt and Hoffmann, the Belvedere organized the show “150 Jahre Gustav Klimt” [“150 Years of Gustav Klimt”]. The focus was on the paintings from the museum’s collection and the reception of Klimt’s oeuvre and person.

In addition to the aforementioned exhibitions organized in Vienna, the Museo d’arte Mendrisio in the Swiss canton of Ticino devoted itself to Klimt’s Vienna in the anniversary year of 2012, viewed through the lens of photographer Heinrich Böhler in the show “L’oro e la danza. La Vienna di Klimt nelle fotografie di Heinrich Böhler” [“Gold and Dance. Klimt’s Vienna in the Photography of Heinrich Böhler”].

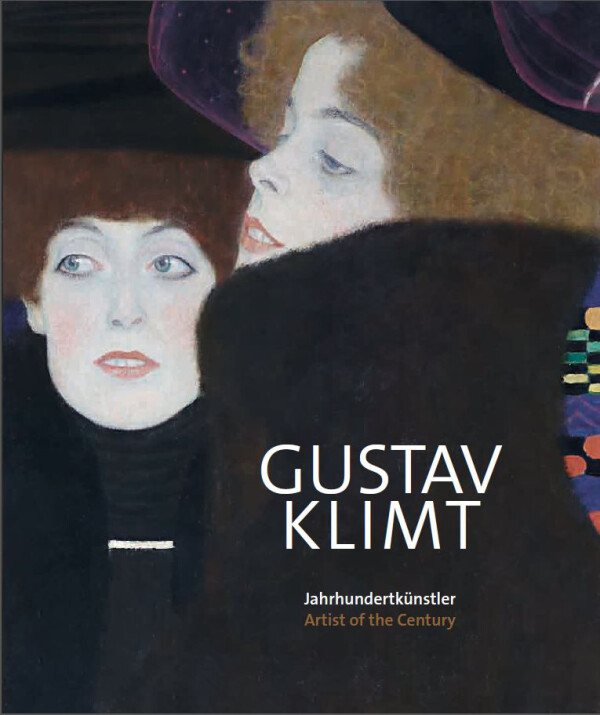

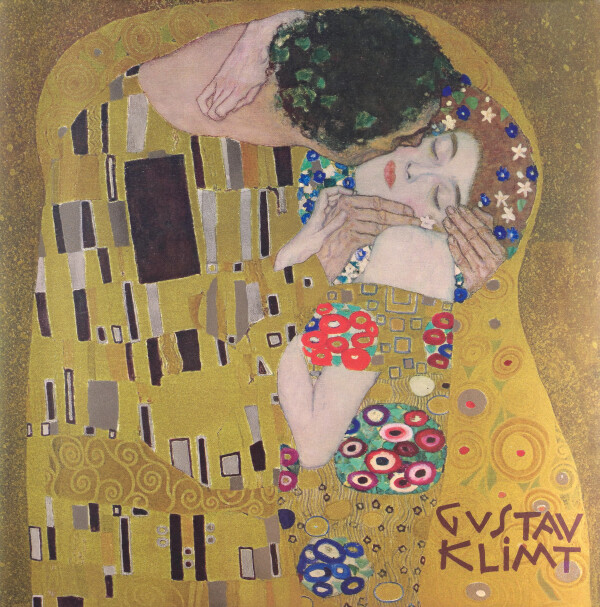

Sandra Tretter, Hans-Peter Wipplinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Jahrhundertkünstler, Ausst.-Kat., Leopold Museum (Vienna), 22.06.2018–04.11.2018, Vienna 2018.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

The Anniversary Year of 2018

2018 marked the 100th anniversary of the deaths of four outstanding personalities of “Vienna around 1900.” In addition to Gustav Klimt, Otto Wagner, Kolo Moser, and Egon Schiele died in 1918 as well. Accordingly, the international exhibition program was quite extensive. Four of the presentations were explicitly dedicated to Klimt.

The first was “Klimt & Rodin: An Artistic Encounter” at the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco in the final months of 2017. The oeuvre of Rodin, who died in 1917 and is considered one of the most important sculptors of modernism, was juxtaposed with the painted work of pioneering Klimt.

The Kunsthistorisches Museum once again offered the opportunity to marvel at Klimt’s works in the staircase. In addition, the iconic painting Nuda Veritas (1899, Theatermuseum, Vienna) was on display as part of the “Stairway to Klimt.”

At the Leopold Museum, Hans-Peter Wipplinger and Sandra Tretter of the Vienna Klimt-Foundation curated the comprehensive anniversary exhibition “Gustav Klimt. Jahrhundertkünstler” [“Gustav Klimt. Artist of the Century”]. Within a chronological overview of his oeuvre featuring first-rate examples, the allegories Death and Life (Death and Love) (1910/11, reworked in 1912/13 and 1916/17, Leopold Museum Privatstiftung, Vienna) and The Bride (1917/18, unfinished, Klimt-Foundation, Vienna) took center stage in this presentation. The genesis of Klimt’s last large-format allegory was brought into special focus through the first presentation of individual sheets from the artist’s last sketchbook.

Finally, the Kunstmuseum Moritzburg in Halle an der Saale compiled the exhibition “Gustav Klimt und Hugo Henneberg. Zwei Künstler der Wiener Secession “ [“Gustav Klimt and Hugo Henneberg. Two Artists of the Vienna Secession”]. Starting out from the painting Portrait of Marie Henneberg (1901/02, Kulturstiftung Sachsen-Anhalt – Kunstmuseum Moritzburg Halle (Saale)), the show was devoted to Klimt as a portraitist of Viennese society and innovative landscapist and to his closely associated contemporary Henneberg in his pioneering role in modern photography.

These exhibitions were complemented by such extensive presentations as “Wiener Werkstätte 1903–1932: The Luxury of Beauty" at the Neue Galerie New York. Vienna’s Leopold Museum devoted itself to Klimt’s companion and favorite photographer Nähr in the exhibition “Moriz Nähr. Fotograf der Wiener Moderne” [“Moriz Nähr. Photographer of Viennese Modernism”], and the Vienna MAK – Museum für angewandte Kunst, followed by the Museum Villa Stuck in Munich, featured “Jack of all trades” Kolo Moser in the exhibition “Koloman Moser. Universalkünstler zwischen Gustav Klimt und Josef Hoffmann” [“Koloman Moser. Universal Artist Between Gustav Klimt and Josef Hoffmann”].

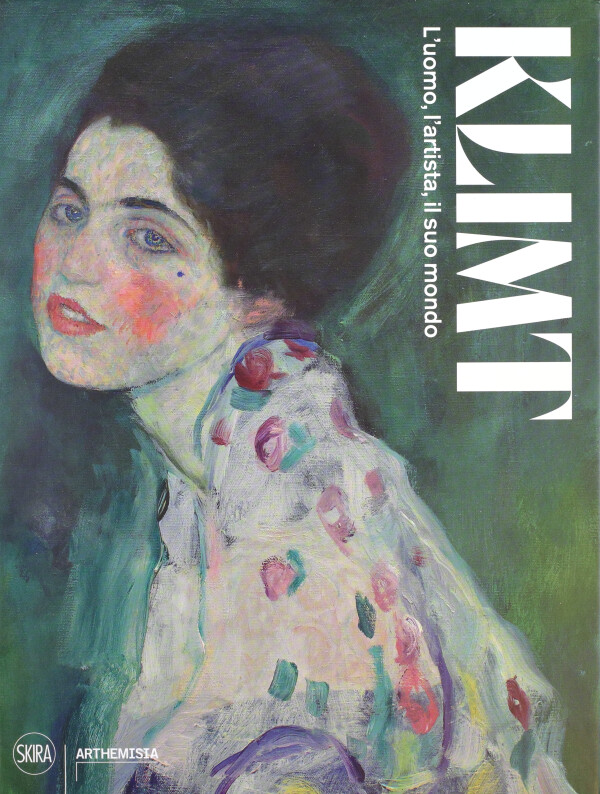

Gabriella Belli, Elena Pontiggia (Hg.): Klimt. L'uomo, l'artista, il suo mondo, Ausst.-Kat., Galleria d'Arte Moderna Ricci Oddi (Piacenza), 12.04.2022–24.07.2022, Milan 2022.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

The Anniversary Year of 2022

In 2022, on the occasion of the 160th birthday of the master of Jugendstil, the Galleria d’Arte Moderna Ricci Oddi in Piacenza presented the show “Klimt. L’uomo, l’artista, il suo mondo” [“Klimt. The Man, the Artist, His World”], a comprehensive overview of different phases of the artist’s work. Particular attention was paid to the painting Portrait of a Woman (Adolescent) (1910, reworked before 1916/17, Galleria d’arte moderna Ricci Oddi, Piacenza), which had been rediscovered in 2019 after more than twenty years.

The Albertina once again exhibited its ample collection of Klimt drawings in the show “Gustav Klimt: 100 Meisterwerke aus der Albertina “ [“Gustav Klimt: 100 Masterpieces from the Albertina”].

The Klimt-Foundation curated the temporary exhibition “Ein Sommer wie damals” [“A Summer Like Back Then”] for the Klimt Museum in Kammer-Schörfling to mark the tenth anniversary of this institution. Klimt’s summer retreats at the Attersee were presented in a new format and visualized using private historical snapshots, among other items. In addition, the focus was on those commissioned works Klimt felt obliged to work on during his summers at the Attersee.

Finally, from October 2022, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, in cooperation with the Belvedere in Vienna, dedicated the extensive exhibition “Golden Boy Gustav Klimt. Inspired by Van Gogh, Rodin, Matisse ...” to Klimt’s international contemporaries. This exhibition was on display at the Belvedere in Vienna from February to May 2023.

Literature and sources

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt – Josef Hoffmann. Pioniere der Moderne, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna) - Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 25.10.2011–04.03.2012, Munich 2011.

- Sabine Haag (Hg.): Gustav Klimt im Kunsthistorischen Museum, Ausst.-Kat., Museum of Art History (Vienna), 14.02.2012–06.05.2012, Vienna 2012.

- Tobias G. Natter, Franz Smola, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Klimt persönlich. Bilder – Briefe – Einblicke, Ausst.-Kat., Leopold Museum (Vienna), 24.02.2012–27.08.2012, Vienna 2012.

- Marian Bisanz-Prakken (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Ausst.-Kat., Albertina (Vienna), 14.03.2012–10.06.2012; Getty Center (Los Angeles), 03.07.2012–23.09.2012, Munich 2012.

- Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Beate Murr (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Erwartung und Erfüllung. Entwürfe zum Mosaikfries im Palais Stoclet, Ausst.-Kat., MAK - Museum of Applied Arts (Vienna), 21.03.2012–15.07.2012, Vienna 2012.

- Ursula Storch (Hg.): Klimt. Die Sammlung des Wien Museums, Ausst.-Kat., Vienna Museum (Vienna), 16.05.2012–07.10.2012, Vienna 2012.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt 150 Jahre, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 13.07.2012–27.01.2013, Vienna 2012.

- Gianna Macconi (Hg.): L'oro e la danza. La Vienna di Klimt nelle fotografie di Heinrich Böhler, Ausst.-Kat., Museo d'arte Mendrisio (Mendrisio), 25.11.2012–31.01.2013, Mendrisio 2012.

- Max Hollein, Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Klimt & Rodin. An Artistic Encounter, Ausst.-Kat., San Francisco, 14.10.2017–28.01.2018, San Francisco 2017.

- Sandra Tretter, Hans-Peter Wipplinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Jahrhundertkünstler, Ausst.-Kat., Leopold Museum (Vienna), 22.06.2018–04.11.2018, Vienna 2018.

- Christian Philipsen, Thomas Bauer-Friedrich, Wolfgang Büche (Hg.): Gustav Klimt und Hugo Henneberg. Zwei Künstler der Wiener Secession, Ausst.-Kat., Moritzburg Art Museum Halle (Saale) (Halle (Saale)), 14.10.2018–06.01.2019, Cologne 2019.

- Christian Witt-Döring, Janis Staggs (Hg.): Wiener Werkstätte 1903-1932. The Luxury of Beauty, New York 2017.

- Uwe Schögl, Hans-Peter Wipplinger (Hg.): Moriz Nähr. Fotograf der Wiener Moderne / Photographer of Viennese Modernism, Ausst.-Kat., Leopold Museum (Vienna), 24.08.2018–29.10.2018, Vienna - Cologne 2018.

- Gabriella Belli, Elena Pontiggia (Hg.): Klimt. L'uomo, l'artista, il suo mondo, Ausst.-Kat., Galleria d'Arte Moderna Ricci Oddi (Piacenza), 12.04.2022–24.07.2022, Milan 2022.

- Elisabeth Dutz (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. 100 Meisterwerke aus der Albertina, Ausst.-Kat., Albertina Modern (Vienna), 08.04.2022–24.07.2022, Vienna 2022.

The Catalogue Raisonné as a Tool for Provenance Research

Fritz Novotny, Johannes Dobai (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Salzburg 1967.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band I, 1878–1903, Salzburg 1980.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Every scholarly examination of Gustav Klimt’s oeuvre begins with the catalogues raisonnés. They deal with questions of authenticity, exhibition history, ownership, and references in literature. Only then is it possible to gain an overview of the artist’s complete oeuvre.

The first catalogue raisonné of Gustav Klimt’s oil paintings dates from 1967 and was compiled by Fritz Novotny and Johannes Dobai. It is based on Dobai’s dissertation, which was approved in 1958. Thanks to the proximity in time to the earliest collectors, the ownership details are very accurate. However, the authors were not yet able to identify all of the works that we now know exist. The second catalogue raisonné of Gustav Klimt’s works was not published until 2008 and presented by Alfred Weidinger. This was followed at a much shorter interval by Tobias Natter’s catalogue raisonné in 2012 (second edition 2018). What stands out here is the development toward a considerably improved image quality, which enables high-quality detailed images of works – a feature that was previously impossible.

Alice Strobl’s four-volume catalogue raisonné of Gustav Klimt’s drawings holds a unique position. Published between 1980 and 1989, this work is so extensive that only a further development, but not a completely new publication seems possible.

Scientific Challenges

The more recent catalogues raisonnés also include the results of provenance research and, in addition to the owners’ names, also document the dates when and ways in which the works changed hands. However, all catalogues raisonnés face the problem that it is often not known in which (private) collection a certain picture is kept and how it got there. Especially when paintings have been passed down within families and never reached the art market, it is difficult to identify the whereabouts and succession of ownership of a painting. In other cases, the owners themselves make a point of not being named, so that they appear neither in catalogues raisonnés nor in exhibition catalogs.

Catalogues Raisonnés of the Future

These catalogues raisonnés are likely to be the last to have appeared in print and will soon be regarded as a historically self-contained corpus of sources. Continuing Strobl’s work, Marian Bisanz-Prakken is currently working on a fifth volume of the catalogue raisonné of Klimt’s drawings. At the same time, however, the Albertina is also compiling the first online catalogue raisonné of Klimt’s drawings. This clearly illustrates once more that online databases will prevail as a future research tool that can be used worldwide and without any restrictions. Databases are very useful for provenance research, which is constantly accumulating new knowledge, as they allow new research findings to be shared directly with other scholars.

Literature and sources

- Fritz Novotny, Johannes Dobai (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Salzburg 1967.

- Fritz Novotny, Johannes Dobai (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Salzburg 1975.

- Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt, Munich - Berlin - London - New York 2007.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2012.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2017.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band I, 1878–1903, Salzburg 1980.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band II, 1904–1912, Salzburg 1982.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band III, 1912–1918, Salzburg 1984.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band IV, 1878–1918, Salzburg 1989.

Klimt in Film and Theater

Gustav Klimt, 1910, ARGE Sammlung Gustav Klimt, Dauerleihgabe im Leopold Museum, Wien

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, 1907, Neue Galerie New York, Acquired through the generosity of Ronald S. Lauder, the Heirs of the Estates of Ferdinand and Adele Bloch-Bauer, and the Estée Lauder Fund

© APA-PictureDesk

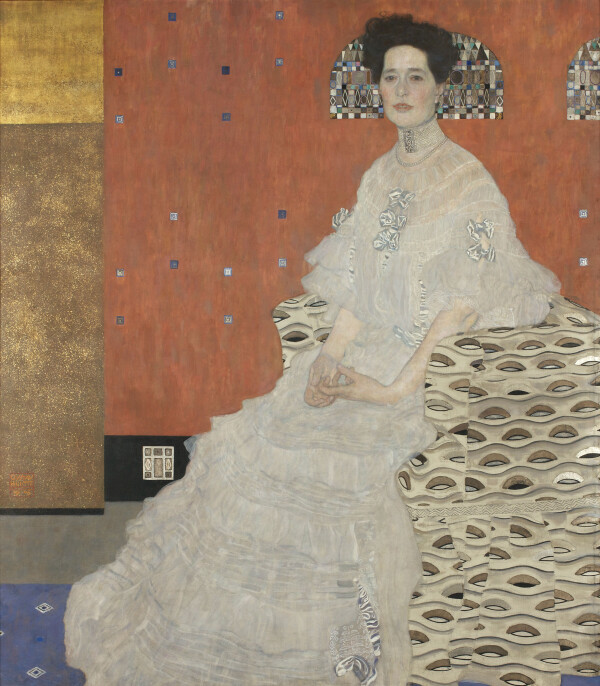

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Fritza Riedler, 1906, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II, 1912, private collection

© APA-PictureDesk

Gustav Klimt: Litzlberg on the Attersee, circa 1915, private collection

© Sotheby's

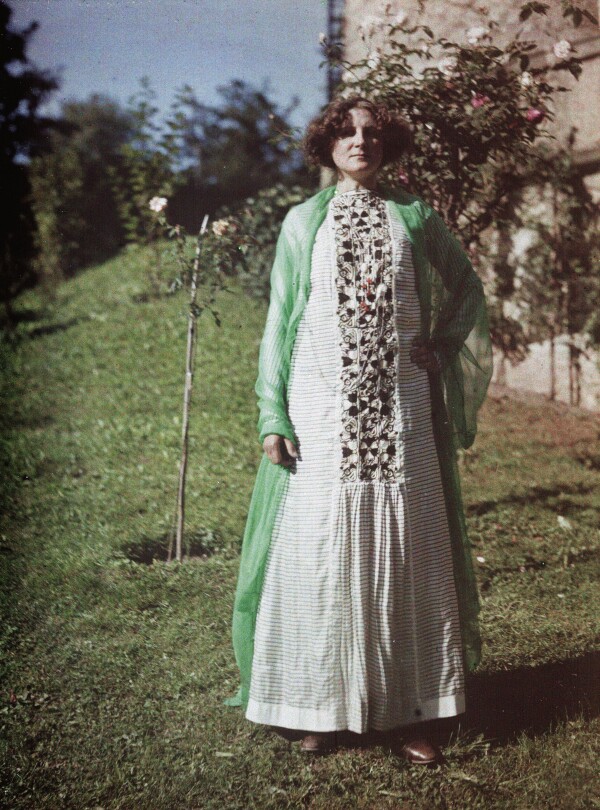

Friedrich Walker: Emilie Flöge in the garden of Villa Paulick, 09/14/1913, Verbleib unbekannt

© APA-PictureDesk

Gustav Klimt and his work have long been considered apt to please the masses, which also applies to the world of film and theater. In recent years, numerous national and international productions have dealt with the life and work of this exceptional artist, as is evidenced by the following selection, with reality and fiction closely interwoven.

Gustav Klimt in Feature Film Productions and Television Series

In 2006, the film Klimt, directed by Raoúl Ruiz, came out, with John Malkovich starring as the grand seigneur of Austrian art and Veronica Ferres acting the part of Emilie Flöge. The sets, peppered with exaggerated opulence, sought to replicate the visual language of Jugendstil. The plot itself is staged as a retrospective introspection of the painter, who, lying on his deathbed, looks back on his fading life in the presence of Egon Schiele.

In 2015, the motion picture Woman in Gold by director Simon Curtis, featuring Helen Mirren as Maria Altmann, dealt with the unwavering lady’s legal dispute of several decades with the Republic of Austria over her rightful inheritance. The focus is not on Klimt as a personality and artist, but on his painting Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907, Neue Galerie New York), a symbol of the illegitimately seized Bloch-Bauer Collection and many other Jewish possessions. The feature film, which is based on a true story, impressively conveys such themes as confiscated art and restitution.

Klimt’s Art as Opulent Set Pieces and Child-Friendly Atmospheric Realm

Apart from the motion picture productions mentioned above, Klimt’s paintings were integrated in film scenes and television series as fictive props, mostly symbols of opulence and wealth. Said portrait of Bloch-Bauer makes an appearance as a trophy-like set piece in the film Ocean’s Twelve from 2004.

In the third season episode Taking Account of the series White Collar, which premiered in July 2011, the painting Portrait of Fritza Riedler (1906, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna) is featured as a luxury good available on the art market. Portrait of Mäda Primavesi (1913, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) appears in the episode The Pious Thieves in season one of the Amazon Prime series Hunters, which came out in 2020, as art confiscated by the Nazis.

In the feature film Mia and Me: The Hero of Centopia, a mixture of live action and CGI animation, Klimt’s language of form and color scheme served as model for the figures and interior decoration of the magical world of Centopia. The appearance of the elves clearly borrows from Klimt’s famous works from the Golden Period. Ornamental configurations generally play a crucial role in the colorful design meant to appeal to children.

A Documentary Perspective of Gustav Klimt

In 2007 the documentary Stealing Klimt, directed by Jane Chablani and Martin Smith, appeared. This production seeks to reconstruct the fate of Klimt’s paintings Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907, Neue Galerie New York), Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II (1912, private collection), Apple Tree I (Small Apple Tree) (c. 1912, private collection), Houses in Unterach on the Attersee (1915/16, private collection), and Birch Forest (Beech Forest) (1903, private collection) and their rightful heirs. One again, Maria Altmann and the Bloch-Bauer Collection served as points of departure. Shortly before the film came out in 2006, the court had decided in Altmann’s favor.

Director Terrence Turner’s documentary Adele’s Wish from 2008 is practically devoted to the same theme. Here, too, the focus is on said paintings.

On the occasion of Klimt’s 150th birthday on 14 July 2012, Herbert Eisenschenk produced the ORF documentary Gustav Klimt – Der Geheimnisvolle [“Gustav Klimt – The Mysterious Man“], which was first presented at the Vienna Leopold Museum. Similar to the exhibition “Klimt persönlich” [“Klimt: Up Close and Personal”], which opened at the museum that same year, the documentary focused on Klimt’s inner life, personality, and private relationships.

In 2017, Karl Hohenlohe, in the episode Klimts Attersee – Ein Künstler auf Sommerfrische [“Klimt’s Attersee – An Artist at His Summer Retreat”] of his ORF program Aus dem Rahmen [“Outside the Frame”], went in search of the painter’s sources of inspiration at this Upper Austrian lake. That same year, the revised version of the documentary, Sehnsucht “nach dort.” Gustav Klimt am Attersee [“Longing for there.” Gustav Klimt at the Attersee“], produced by Peter Weinhäupl, appeared.

The documentary L’Héritier, directed by Édith Jorisch, also premiered in 2017. The content was supplied by the adventures of her grandfather, Georges Jorisch, grandson and sole heir of Amalie Redlich. He had looked, among other things, for the landscape painting Litzlberg on the Attersee (c. 1915, private collection) for more than ten years. In 2011, it was finally restituted to Jorisch by the Museum der Moderne Salzburg and the State of Salzburg and subsequently auctioned off at Sotheby‘s in New York. To thank Salzburg for the smooth restitution, Jorisch helped fund the adaption of the former water tower, since then known as Amalie Redlich Tower.

In 2018, marking the 100th anniversary of the deaths of Klimt, Egon Schiele, Otto Wagner, and Kolo Moser, the documentary Klimt & Schiele. Eros & Psyche focused on the biographies of and the bond between these two exceptional personalities.

2020 saw the broadcast of the documentary Emilie Flöge & Gustav Klimt, produced in cooperation with arte for its series Liebe am Werk [“Love at Work”] and devoted to the relationship between the artist and his lifelong soulmate, Emilie Flöge.

In 2023, the series Klimt & The Kiss was released in the documentary series Exhibition on screen. Based on Klimt's painting The Kiss (Lovers) (1908/09, Belvedere, Vienna), the life and work of the exceptional artist are examined and viewed from new angles through experts' interviews.

Gustav Klimt in the World of Theater

The year 2009 saw the world premiere of the musical Gustav Klimt within the framework of the Lower Austrian Gutenstein Festival (now Raimundspiele Gutenstein). The production spanned the painter’s life from his years as a student to his artistic reorientation and his journey of self-discovery up to his death. In 2012, the musical production was again performed at the Vienna Künstlerhaus to mark Klimt’s 150th birthday. The venue was thus identical with the very institution Klimt had left in 1897 to eventually become successful as first president of the newly founded Vienna Secession.

In 2017, the Klimt-Foundation as a non-profit organization presented the theater solo Süße Wiener Dunkelheit / tiefheller See [“Sweet Viennese Darkness / Deep Bright Lake”] by the playwright Clara Gallistl, featuring Maxi Blaha as Emilie Flöge. The historic Villa Paulick in Seewalchen, which had been an inspiring meeting place for Flöge and Klimt, served as setting. The plot took place in Vienna during the 1930s, with Flöge reliving her time spent with Klimt. Numerous original quotes from the correspondence between the two soulmates and musical sequences from the early 20th century evoked an atmospheric scene of an epoch reverberating to this day.

In 2018, the producer and stage director Julia Marie Wagner landed another Klimt coup in the world of theater with Wally:Emilie – Schauspiel mit Musik. It had its world premiere in Vienna in 2019, when, at the Klimt-Foundation’s invitation, the characters of Emilie Flöge and Wally Neuzil once again met at the Villa Paulick in Seewalchen on the Attersee to wallow in memories of their companions Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele and share some anecdotes.

Literature and sources

- Klimts „Litzlberg“ erzielte 30 Mio. Euro. Der Standard (05.12.2011). kurier.at/kultur/klimts-litzlberg-erzielte-30-mio-euro/735.666 (02/23/2022).

- Olga Kronsteiner: Gemälde von Gustav Klimt als Filmstatisten. Der Standard (22.03.2020). www.derstandard.at/story/2000115965982/gemaelde-von-gustav-klimt-als-filmstatisten (02/20/2022).

- Stealing Klimt. www.stealingklimt.com/ (03/01/2023).

- Gustav Klimt Der Geheimnisvolle. www.ots.at/presseaussendung/OTS_20120626_OTS0098/gustav-klimt-der-geheimnisvolle-praesentation-der-orf-doku-von-herbert-eisenschenk-im-leopold-museum (02/13/2023).

- Adele’s Wish. www.adeleswish.com/ (03/01/2023).

- Wally:Emilie – Schauspiel mit Musik. www.wally-emilie.com/ (03/01/2023).