Vienna Secession

Hotel Victoria, Favoritenstraße 11, 1040 Vienna

© Wien Museum

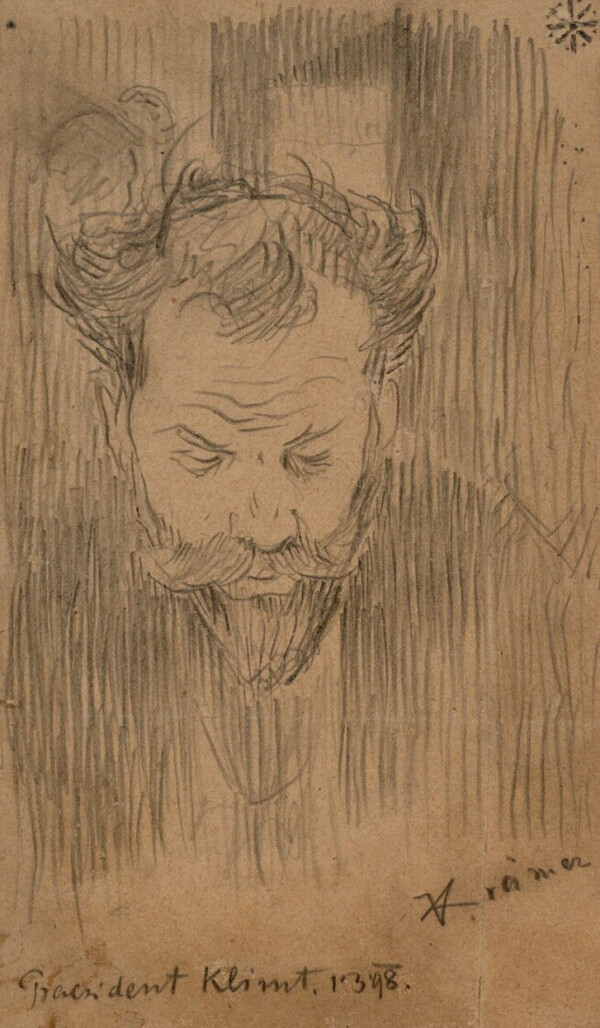

Johann Victor Krämer: President Klimt, 01.03.1898, The Albertina Museum, Vienna

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

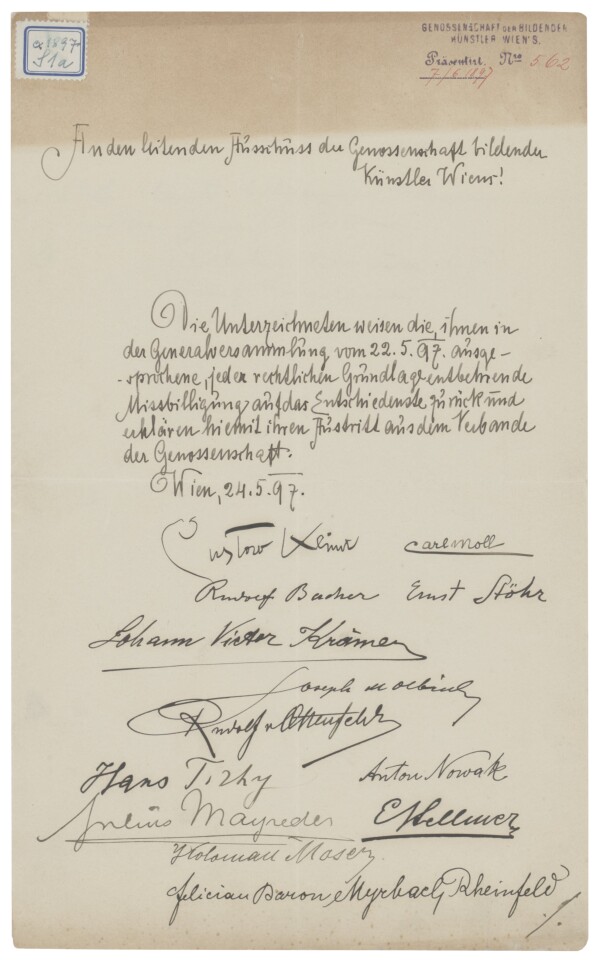

Alfred Roller: Letter written by Alfred Roller to the Committee of the Cooperative of Fine Artists of Vienna, signed by Gustav Klimt, Carl Moll, Rudolf Bacher, Ernst Stöhr, Johann Victor Krämer, Joseph Maria Olbrich, and others., 05/24/1897, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Wien

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna

The Association of Austrian Artists Secession was founded in 1897 by artists gathering around Gustav Klimt and had its heyday as a vital driving force behind Viennese Modernism until the “Klimt Group” left in 1905. The magazine Ver Sacrum served as the official organ, and exhibitions were held in a specially erected building from 1898.

From the early 1890s, the European art world saw various reform efforts, particularly in England, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany. The desire to renew art led to the foundation of the Secessions in Düsseldorf and Munich, with the burgeoning ideas of modernism spreading through art magazines such as The Studio, Pan, and Jugend.

Foundation of the Vienna Secession

As early as the mid-1890s, tensions within the traditional Cooperative of Visual Artists in Vienna (Künstlerhaus for short) would lead to the formation of a nucleus of visual artists by the fall of 1896. Among them were artists who belonged to the loose associations of the so-called Hagengesellschaft and Siebener-Club [Club of the Seven], something like a table of regulars that met at the Hotel Victoria. According to Ludwig Hevesi’s foreword to Berta Zuckerkandl’s volume Zeitkunst, which was published in 1908, the idea of founding the Vienna Secession was born at the Salon Zuckerkandl, which was frequented by Gustav Klimt, Carl Moll, Alfred Roller, Hermann Bahr, and others. They wanted to pursue their goals autonomously and as an independent association, and, following a few meetings, set up a “Preparatory Committee,” with Klimt, Rudolf Bacher, Wilhelm Bernatzik, Josef Engelhart, Moll, Kolo Moser, Anton Nowak, and Roller nominated as delegates. This committee was entrusted with the tasks of finding a site for the exhibition building, drafting the association’s statutes and rules of procedure for organizing exhibitions, securing funds, and ensuring that all prerequisites for the foundation would be in place in general.

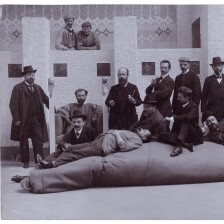

The Association of Austrian Artists Secession was finally established on 3 April 1897, its best-known founding members including Klimt, Kolo Moser, and Joseph Maria Olbrich. The Secessionists elected Klimt as their first president, Moll as vice-president, and the 85-year-old Rudolf von Alt as honorary president; there was also a working committee installed to plan the association’s exhibition building.

On 5 April, the Secessionists informed the Cooperative about the constitution, motives, and goals of their association, and at the same time they spread the word about its establishment to the daily papers. Misunderstandings and conflicts led to a fierce dispute at the extraordinary general assembly of the Vienna Künstlerhaus on 22 May. This was followed by the resignation of several members rallying behind Klimt, which they announced in their letter of resignation on 24 May 1897, thus finally breaking with the Cooperative.

This separation had been preceded by numerous conflicts. The main points of criticism were the exhibition policy, lack of internationality, and excessive market orientation of the sometimes-overloaded Künstlerhaus exhibitions and its lavish festivities. The “affair"” surrounding Josef Engelhart’s naturalistic female nude The Cherry Picker (1893, destroyed in World War II), which was rejected and only exhibited at the Künstlerhaus after Engelhart’s objection in 1894, was also often given as a reason.

The Secession opposed the conservative, historicizing tendencies prevalent at the art academies and saw itself as a body representing the interests of modern artists. By July 1898, some 50 full members had joined the association, who now presented itself as if in a competition with the Künstlerhaus. Above all, they advocated a “revival of the Viennese art scene,” the encounter with international art, and the freedom of artistic creation. The focus was on the Gesamtkunstwerk or universal work of art, in which the arts and crafts should play an equal role alongside the visual art genres of painting, sculpture, and architecture.

The Secession recorded its activities, exhibition highlights, financial statements, statutes, rules of procedure, and membership lists in annual reports. The president was elected annually and, due to its extensive agenda, the association, in addition to a working committee responsible for planning exhibitions, was organized in the form of a number of individual committees: the “Press Committee,” the “Editorial Committee” for the association’s periodical Ver Sacrum, and the “Decorations Committee” for the interior design of the exhibitions. The Secession also went in search of its own corporate identity, which should be reflected in a consistent design of office stationery, posters, exhibition catalogs, and the association’s periodical, among other things.

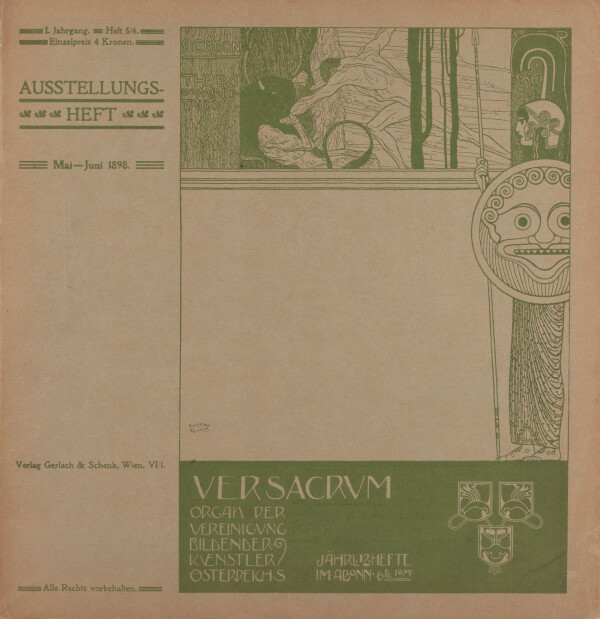

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 5/6 (1898).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Ver Sacrum

At its general assembly of 21 July 1897, the association representing the interests of modern artists decided to publish its programmatic ideas in the association’s organ, Ver Sacrum. A contract was thus signed with the publishing house Gerlach & Schenk in August 1897. As the Neue Freie Presse reported on 19 November 1897, the aim of the illustrated periodical was

“to not only offer the artists a field of activity aside from exhibitions, but also to convey to both the Austrian and international audience a more intimate knowledge of our art life.”

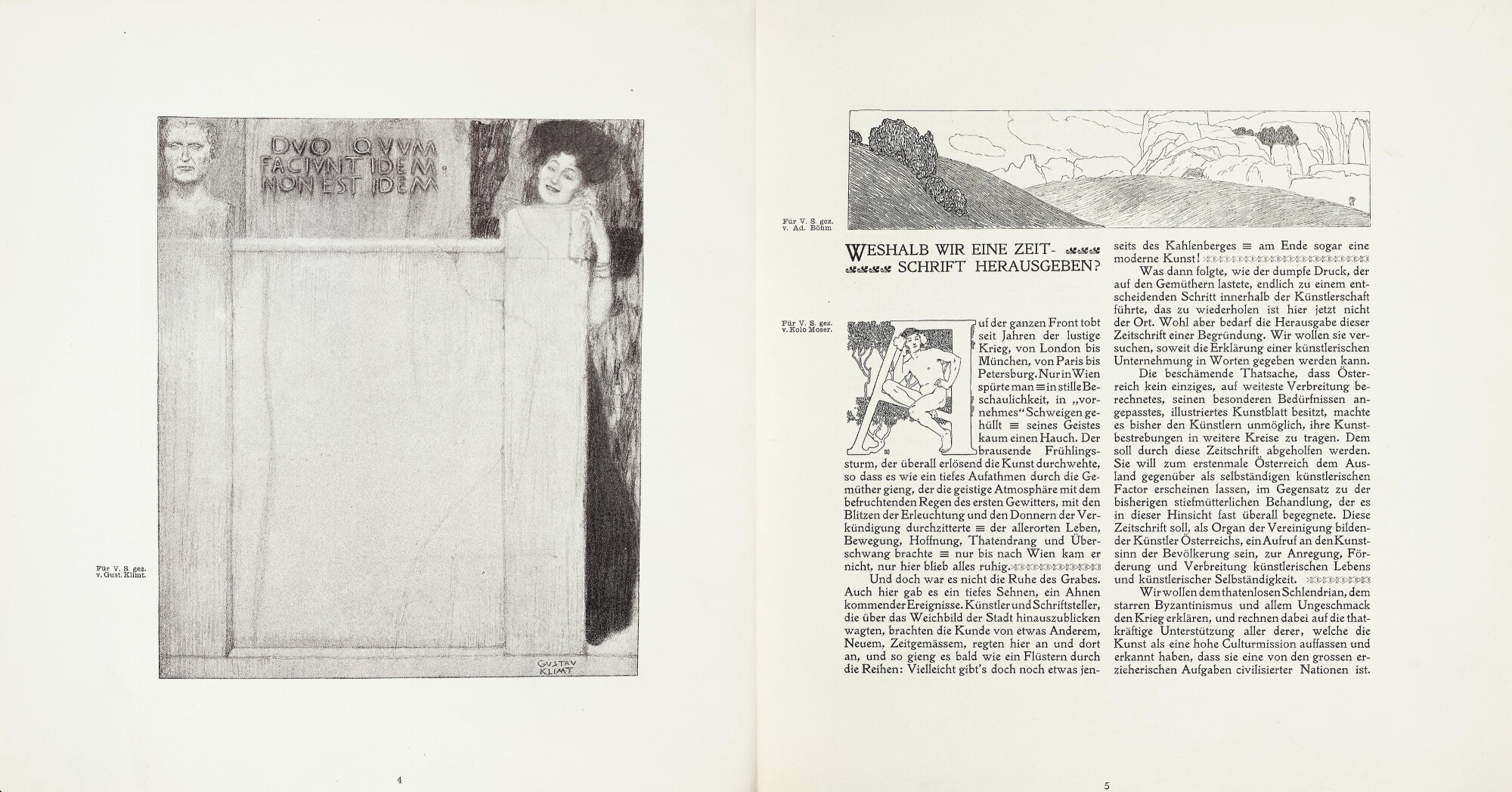

The first issue was published in January 1898, with Alfred Roller as editor. Hermann Bahr and Max Burckhard were on the literary advisory board. The latter wrote an opening essay for the first issue in which he explained the association’s choice of name with the Roman custom of the “secessio plebis” – the march of the common people, a demonstration of power to realize political demands against patricians. He also explained the title of the magazine Ver Sacrum: “Holy Spring” also refers to a Roman tradition in which those born in spring, as soon as they had grown up, “had to go abroad to found a new community on their own, with their own goals.” In the introductory article Why We Publish a Magazine, the association also postulated its wish to

“[a]ppeal to the population’s sense of art […], for the inspiration, promotion, and dissemination of artistic life and artistic autonomy.”

Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

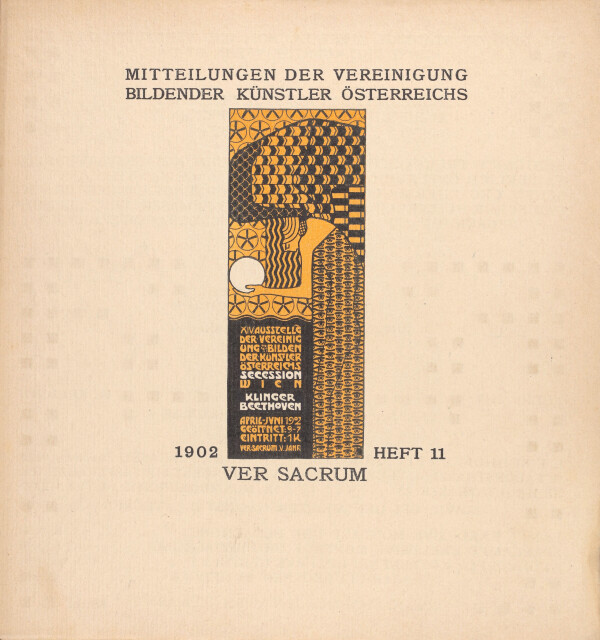

Vereinigung bildender KünstlerInnen Wiener Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Mitteilungen der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 5. Jg., Heft 11 (1902).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Ver Sacrum was published in six volumes between 1898 and 1903, with the issues initially appearing on a monthly basis. The subtitle Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs [“Organ of the Association of Austrian Artists”] changed to Zeitschrift der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs [“Magazine of the Association of Austrian Artists”] in 1899 on under the new publisher E. A. Seemann. Starting in 1900, the third and subsequent volumes were self-published by the association. The subtitle was then changed to Mitteilungen der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs [“Notes of the Association of Austrian Artists”], and the journal began to appear twice a month.

Ver Sacrum became one of the most important art magazines of its age, not only because of its programmatic content. The concept of Gesamtkunstwerk was also continued in the new combination of literature, visual arts, and music. The individual issues mostly contained reproductions of works of art, exhibition views, original graphic art, and book decoration. The innovative arrangement of image and text elements in articles on art theory, poems, artists’ features, as well as exhibition and book reviews reflected the formal language of Jugendstil or Art Nouveau and the flourishing art of Viennese flatness. The graphic design had a groundbreaking impact on Austrian book art.

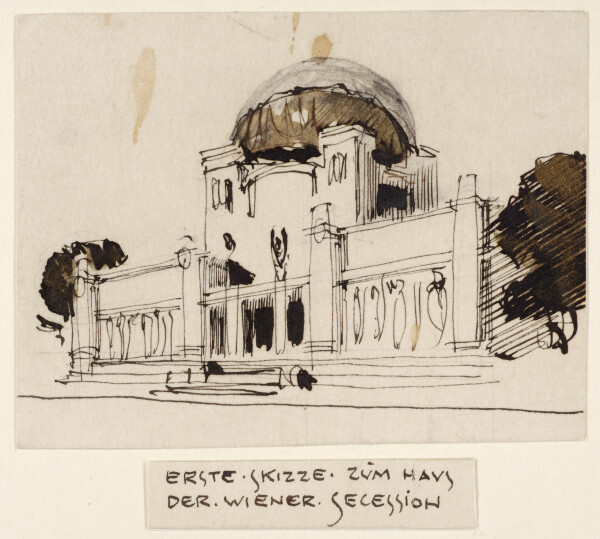

Joseph Maria Olbrich: First sketch for the House of Vienna Association, 1897, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek

Association with Naschmarkt and Academy of Fine Arts

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

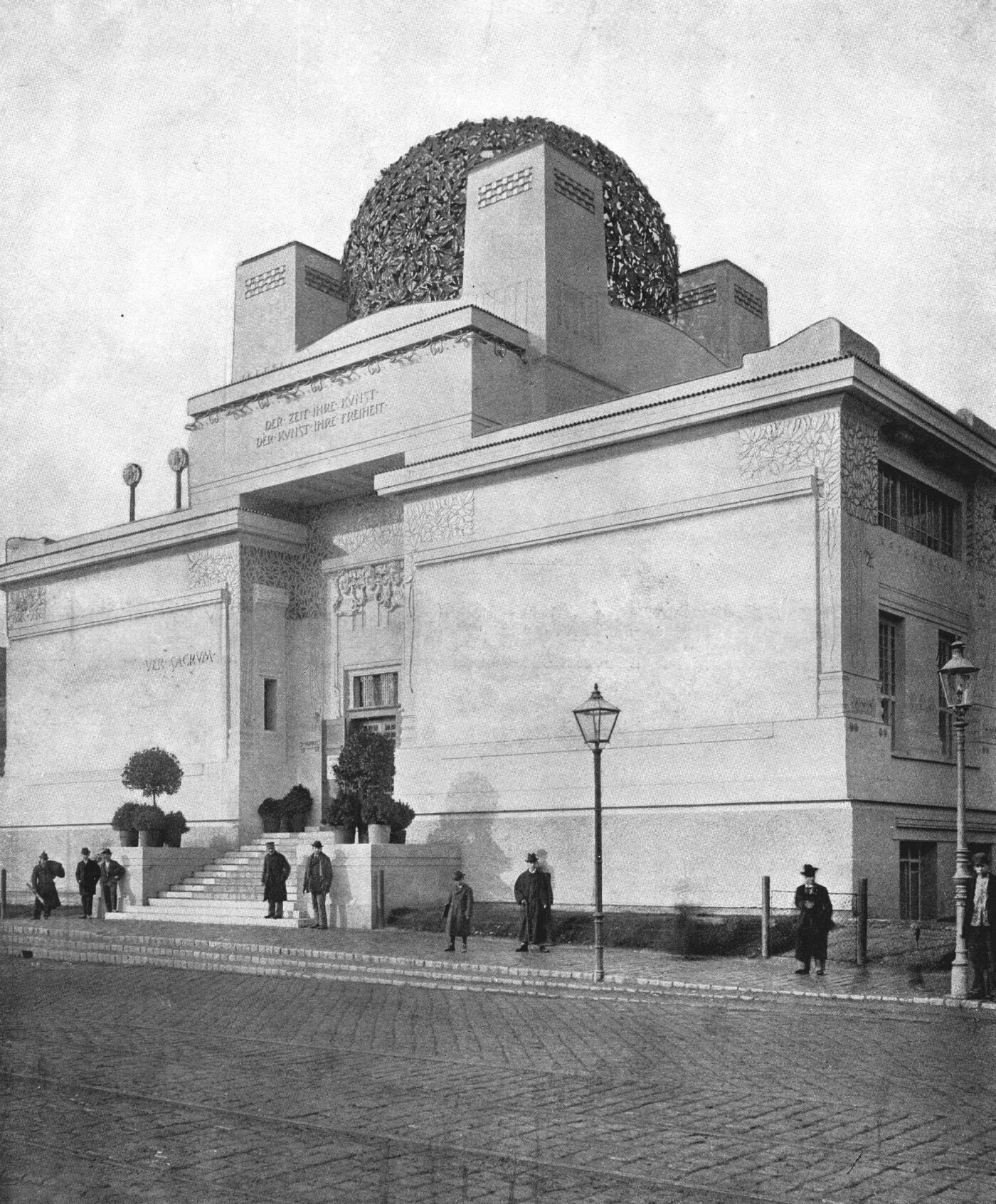

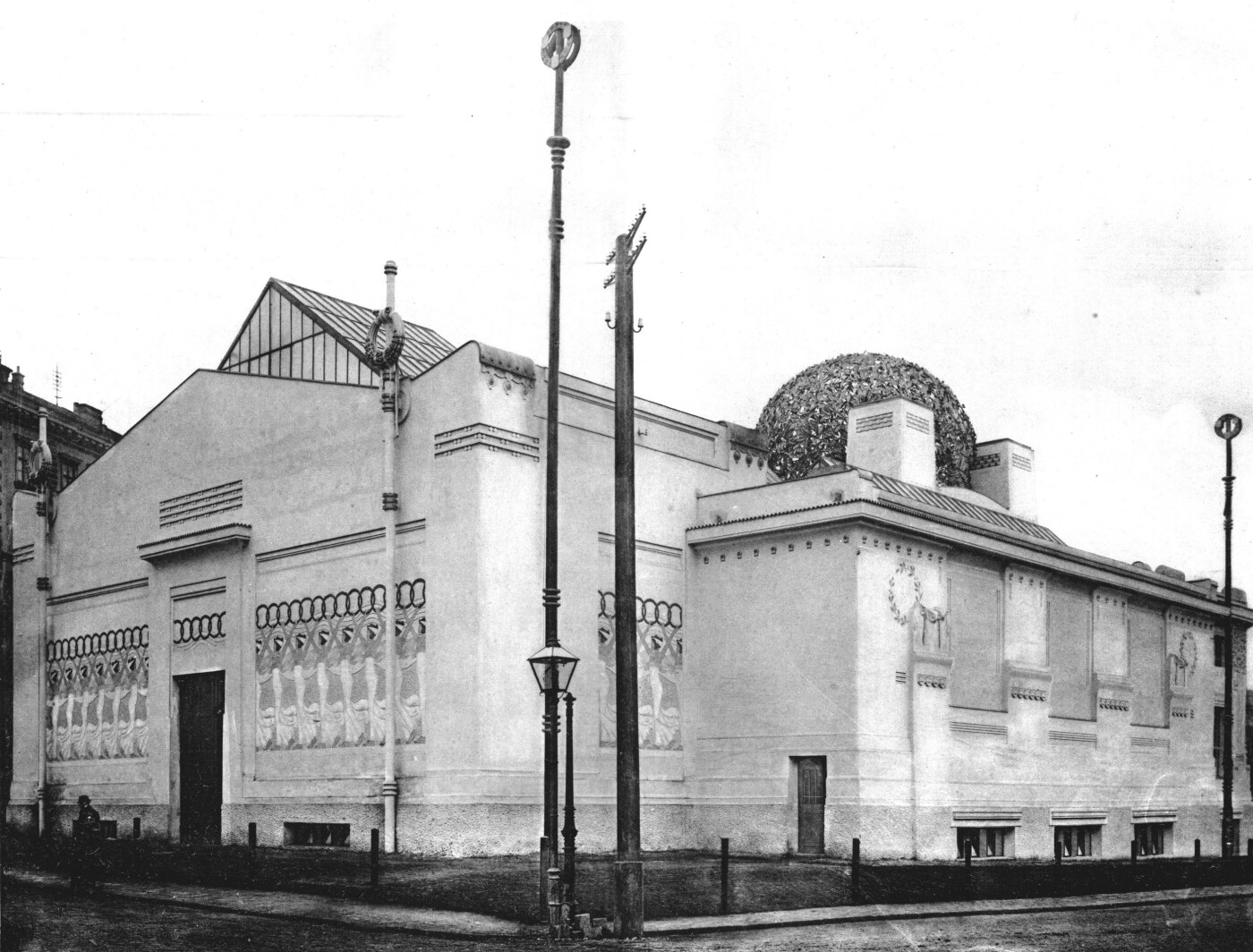

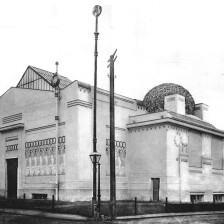

“The House of the Secession”

Planning its own exhibition building had begun even before the Secession was officially founded, when the architect Joseph Maria Olbrich prepared the submission of plans for the building project, which were presented to the Vienna City Council in March 1897. After lengthy negotiations regarding the building site, the City approved the plot behind the Academy of Fine Arts on Linke Wienzeile (now Friedrichstraße) near the Naschmarkt on 17 November 1897. The foundation stone was laid on 28 April 1898. Under Olbrich’s guidance, Adolf Böhm, Josef Hoffmann, Kolo Moser, and Othmar Schimkowitz were also involved in the design of the building, which would be completed by November 1898.

The temple of art, featuring a dome of gilded laurel leaves also known as the “Golden Cabbage,” is one of the key buildings of Viennese Modernism. Ludwig Hevesi wrote about the Secession’s motto on the white façade in Acht Jahre Sezession:

“There are also golden characters to be spelled and interpreted. The writing above the door reads: ‘TO EVERY TIME ITS ART. TO ART ITS FREEDOM.’ […] The artists chose this headline from a number of variants I had formulated at their request.”

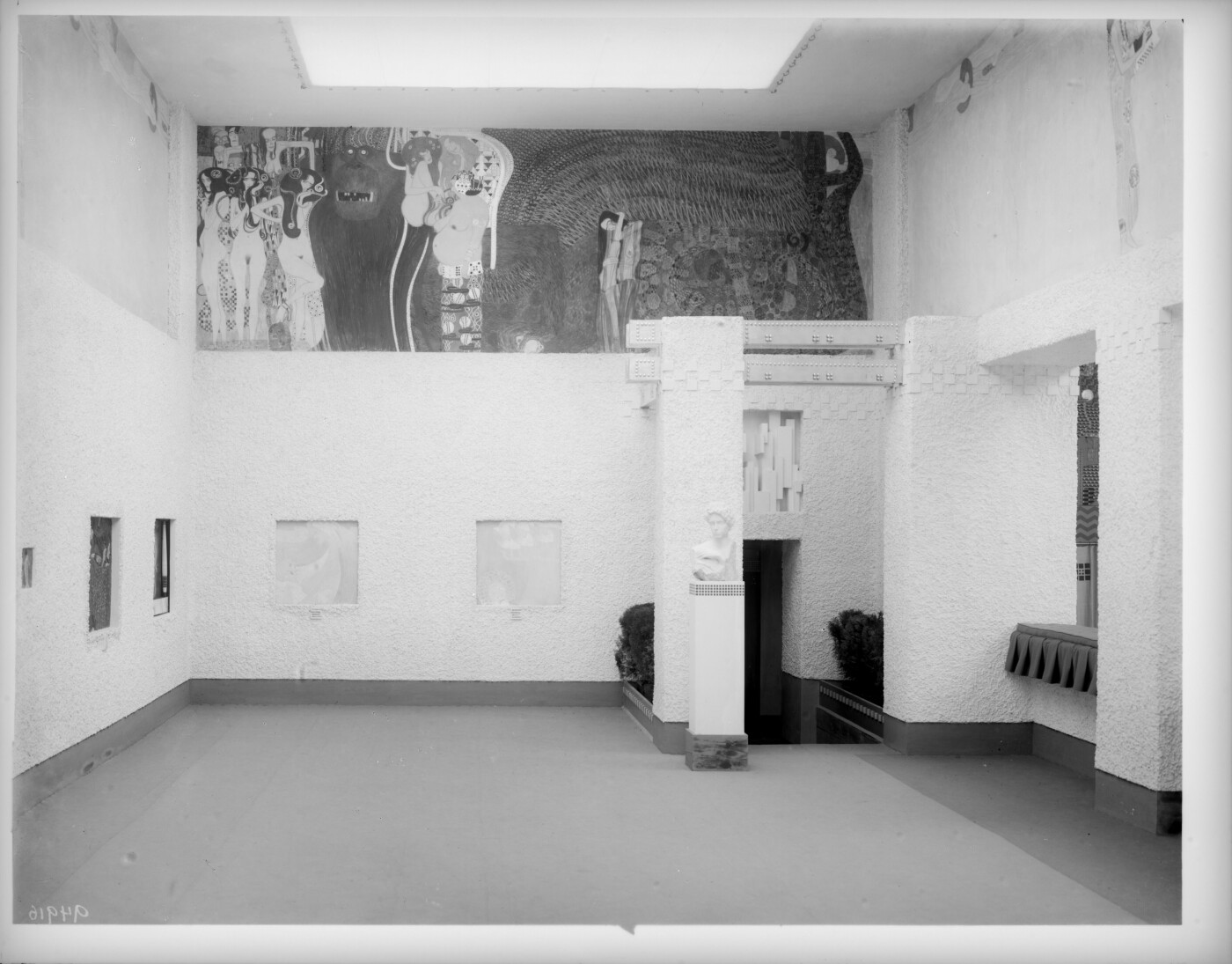

In the January 1899 issue of Ver Sacrum, the Secessionists explained the purpose of the exhibition pavilion: “[...] to provide a useful framework for the activities of a modern artists’ association while employing the simplest of means.” The exhibition rooms were to be on the same level, spacious, pleasantly tempered by heating and ventilation systems and evenly illuminated in the main hall via a glass roof. Partition walls that could be moved across the entire surface of the main hall allowed the exhibition rooms to be divided flexibly and adapted individually for the exhibitions. Rooms with side lighting were provided for spatial art exhibitions, and the “home to art” also housed a reception room, a meeting room, servants’ apartments, depots, and rooms for administrative operations, as well as the editorial office for the association’s periodical.

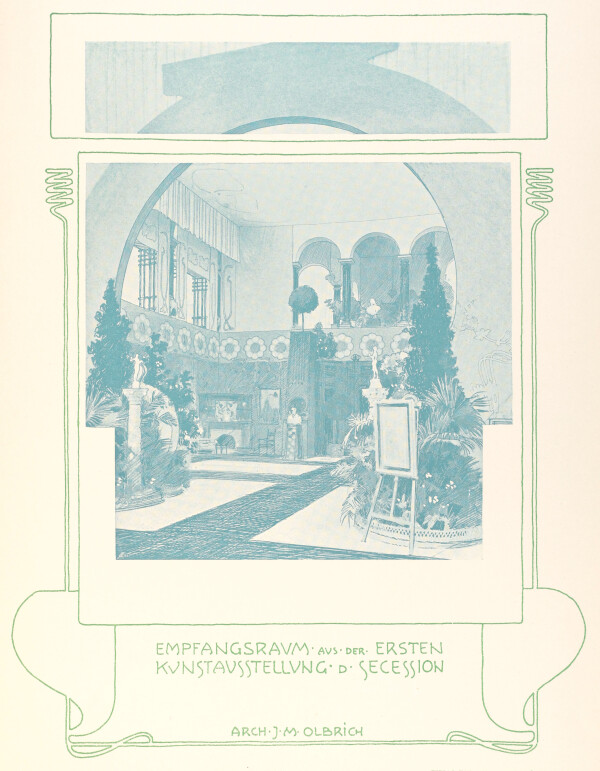

Reception room of the I. Art Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Fine Artists in the flower rooms of the k. k. Gartenbaugesellschaft, 1898, in: Der Architekt. Wiener Monatshefte für Bau- und Raumkunst, 4. Jg. (1898).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

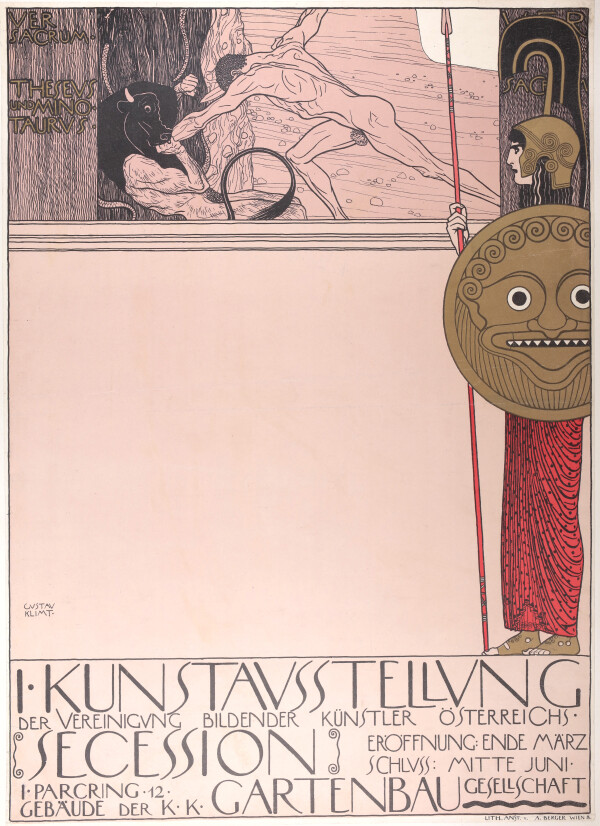

Gustav Klimt: Poster design for the I Secession Exhibition, uncensored version, 1898, Klimt Foundation, Vienna

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Exhibitions

As the Secession started out without its own exhibition building, the “I. Kunst-Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs” [“1st Art Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists”] took place in the rented and adapted flower halls of the Imperial-Royal Horticultural Society on Parkring. Hoffmann and Olbrich designed the exhibition architecture with the support of the “Decorations Committee,” and so the first exhibition opened on 26 March 1898. The preface to the self-published exhibition catalog stated that the Secession

“made the first attempt in Vienna to offer the audience an exquisite exhibition of specifically modern works of art. The intention to organize selected small-scale exhibitions was one of the fundamental ideas at the beginning of our new association.”

The Secession wished to present “a picture of modern art from abroad,” and the “artistic arrangement” of the exhibition for its part was to “have a groundbreaking effect on Vienna.” Although censorship of the exhibition poster – in which naked Theseus fights the Minotaur – caused a minor scandal, even Emperor Francis Joseph I visited the exhibition on the morning of 5 April 1898. He expressed his appreciation for the fascinating presentation in which international artists like Auguste Rodin, Fernand Khnopff, Giovanni Segantini, and Constantin Meunier were presented alongside Austrians. Newspaper articles about the emperor’s visit gave the Secession an important status alongside the Künstlerhaus. The exhibition was also a great financial success, thanks to the official art purchases by the Imperial-Royal Ministry of Culture and Education and a number of private purchases.

The 2nd Exhibition opened in November 1898 and already took place in the association’s own building, which was to be used exclusively for the presentation of works of art. With its program and reduced exhibition architecture, the Secession sought to set itself apart from the Cooperative, which was known for its lavish festivals and frequent, overloaded exhibitions of a “show-booth nature.” Writing in Ver Sacrum, Hermann Bahr also criticized the profit-oriented nature of the Vienna Künstlerhaus: “Business or art [...], that is the question of our Secession,” and cleverly used the ideological opposition between art and commerce to position himself publicly.

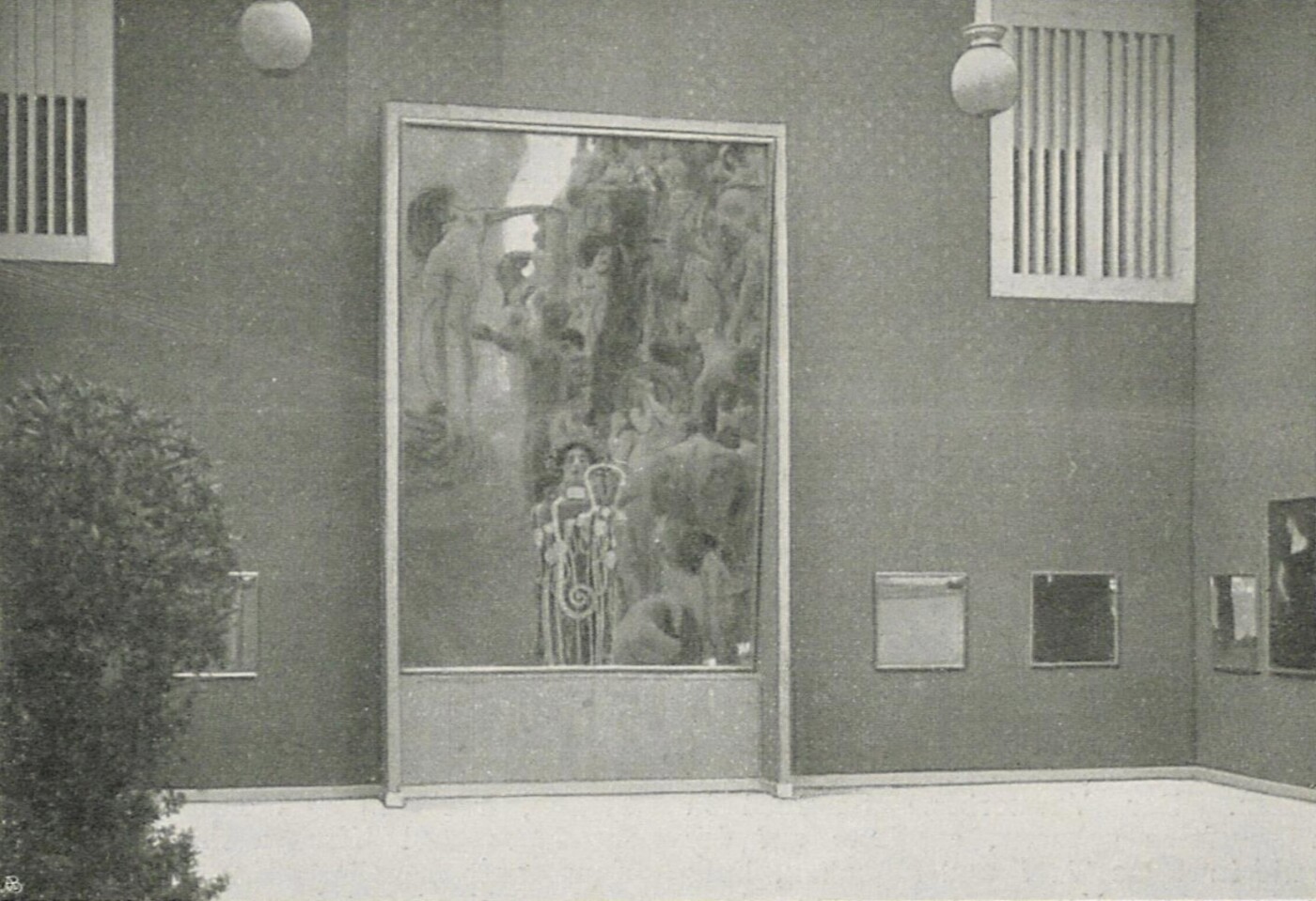

The 3rd Exhibition in 1899, presenting Max Klinger’s monumental painting Christ on Olympus, was particularly sensational, yet Gustav Klimt’s Faculty Paintings, when exhibited at the Secession, would cause a bigger scandal: Philosophy (1900), Medicine (1901), and Jurisprudence (1903). Among the most important exhibitions were the 6th Exhibition (1900), featuring Japanese art, the 8th Exhibition (1900), which showcased European arts and crafts, a memorial exhibition for Giovanni Segantini (1901), participation in the “Deutschnationale Kunstausstellung” [“German National Art Exhibition”] in Düsseldorf (1902), and the 14th Exhibition (1902), for which Klimt conceived the Beethoven Frieze. The “Kollektiv-Ausstellung Gustav Klimt” [“Gustav Klimt Collective Exhibition”] (1903/1904) and the Secession’s 19th Exhibition (1904), featuring pioneering works by Ferdinand Hodler, were also particularly noteworthy.

Julius Scherb (?): Insight into the 1928 memorial exhibition, June 1928 - August 1928, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

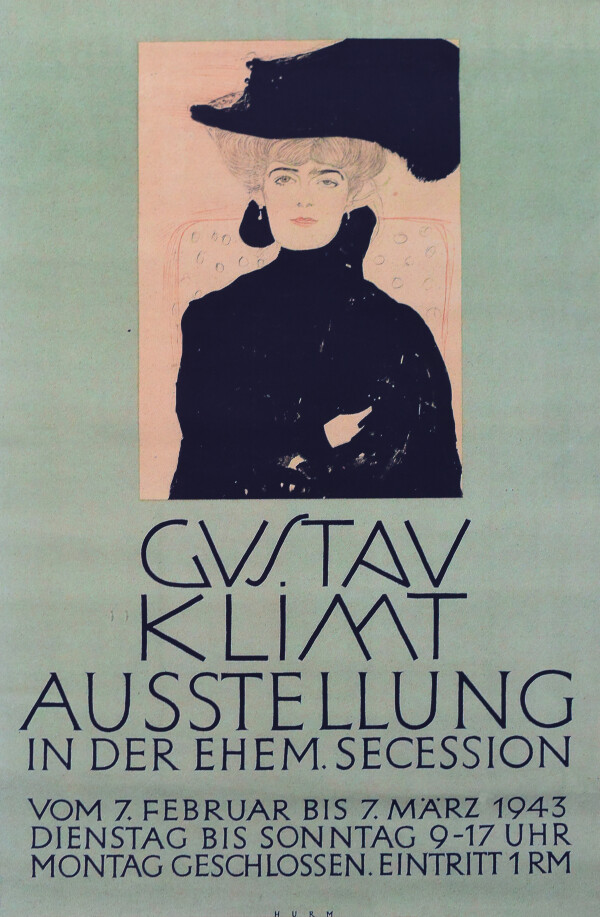

Poster of the Gustav Klimt memorial exhibition, 1943, private collection

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

The Klimt Group’s Resignation

Following the foundation of the Wiener Werkstätte by Hoffmann, Moll, and the entrepreneur Fritz Waerndorfer in 1903, the debate about participation in the World’s Fair in St. Louis (1904) in particular led to differences within the association. The idea that Secession members could present their art at the Miethke Gallery and Carl Moll’s dual role as vice-president of the Secession and “artistic advisor” to the Miethke Gallery, which had been taken over by Paul Bacher, also led to conflicting interests. Moreover, two artistic camps formed, the “Stylists” around Klimt and the “Impressionists” around Engelhart, Rudolf Bacher, and Ferdinand König, also referred to as the “naturalistic wing.” However, they were not so much followers of clearly distinguishable art movements, but rather groups of people growing apart.

After Carl Moll left due to his position at the Miethke Gallery, the so-called “Klimt Group,” including Moser, Hoffmann, Wagner, Roller, Bernatzik and other artists, also withdrew from the association in 1905. Numerous newspapers and art magazines reported on a “session of the Secession,” and some foreign and “corresponding” members like Ferdinand Hodler followed their example and resigned as well. Without Klimt as an artistic driving force, the Vienna Secession quickly lost in recognition.

Wartime and Reconstruction

Following the outbreak of World War I, the Secession building was used as “Red Cross Reserve Hospital Secession” until 1917. Ten years after Klimt’s death, Anton Hanak, Josef Hoffmann, Berta Zuckerkandl, and Carl Moll, among others, organized a memorial exhibition for Gustav Klimt, which took place in the summer of 1928, presenting over 75 works at the Secession. In the fall of 1939, the Secession was integrated into what was now known as the Society of Visual Artists in Vienna, Künstlerhaus. Possibly in order to build on more successful times, the institution appropriated the memory of Klimt, and in 1943 the Vienna Reich Governor organized a large commemorative exhibition at the “Ausstellungshaus Friedrichstraße” to mark the 80th anniversary of Klimt’s birth. The building also served as a granary and tire depot during the war and was destroyed down to its foundations in an air raid and fire in 1945. After the end of the war, the Association of Austrian Artists Vienna Secession was re-established, and its house was rebuilt.

Literature and sources

- N. N.: Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, in: Das Vaterland. Zeitung für die österreichische Monarchie, 06.04.1897, S. 6.

- F.M.M.: Wiener Brief, in: Innsbrucker Nachrichten, 07.04.1897, S. 4-5.

- Hermann Bahr: Unsere Secession, in: Die Zeit, 29.05.1897, S. 139-140.

- N. N.: Der Pavillon der Secessionisten, in: Neue Freie Presse, 19.11.1897, S. 5.

- N. N.: Der Kaiser in der Secessionisten-Ausstellung, in: Das Vaterland. Zeitung für die österreichische Monarchie, 05.04.1898, S. 3.

- N. N.: Staatliche Kunstankäufe, in: Wiener Zeitung, 04.06.1898, S. 4.

- N. N.: Staatliche Kunstankäufe, in: Wiener Zeitung, 01.06.1898, S. 7.

- N. N.: Staatliche Kunstankäufe, in: Wiener Zeitung, 15.06.1898, S. 3.

- Richard Muther: Wiener Ausstellungen, in: Die Zeit, 24.03.1900, S. 185.

- Hermann Bahr: Secession, Vienna 1900.

- Ludwig Hevesi: Acht Jahre Sezession (März 1897–Juni 1905). Kritik – Polemik – Chronik, Vienna 1906.

- Robert Weissenberger: Die Wiener Secession, Vienna 1971.

- Oskar Pausch: Gründung und Baugeschichte der Wiener Secession, Vienna 2006.

- Marian Bisanz-Prakken (Hg.): Heiliger Frühling. Gustav Klimt und die Anfänge der Wiener Secession 1895–1905, Ausst.-Kat., Albertina (Vienna), 16.10.1998–10.01.1999, Vienna 1999.

- Christian Huemer: Jahrmarktbude oder Musentempel? Das Wiener Künstlerhaus und der Kunsthandel, in: Peter Bogner, Richard Kurdiovsky, Johannes Stoll (Hg.): Das Wiener Künstlerhaus. Kunst und Institution, Vienna 2015, S. 267–275.

- Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1898), S. 1-2, S. 10-15.

- Ludwig Hevesi: Zum Geleit, in: Berta Zuckerkandl (Hg.): Zeitkunst. Wien 1901–1907, Vienna 1908.

- Adolph Lehmann's allgemeiner Wohnungs-Anzeiger. Nebst Handels- u. Gewerbe-Adressbuch für d. k. k. Reichshaupt- u. Residenzstadt Wien u. Umgebung, 40. Jg., Band 1 (1898), S. 260.

- Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Erster Jahresbericht der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession, Vienna 1899.

- Friedrich Achleitner (Hg.): Secession. Die Architektur, Vienna 2003.

- Oskar Pausch: Kolo Moser und die Gründung der Secession, in: Rudolf Leopold, Gerd Pichler (Hg.): Koloman Moser 1868−1918, Ausst.-Kat., Leopold Museum (Vienna), 25.05.2007–10.09.2007, Munich 2007, S. 58-61.

- N. N.: Der Bruch in der Wiener Sezession, in: Kunstchronik. Wochenschrift für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, N.F., 16. Jg., Heft 29 (1904/05), Spalte 454-455.

- N. N.: Die Spaltung in der Wiener Sezession, in: Die Werkstatt der Kunst. Organ für die Interessen der bildenden Künstler, 4. Jg., Heft 39 (1905), S. 530-531.

- Ludwig Hevesi: Der Bruch in der Sezession, in: Kunst und Kunsthandwerk. Monatsschrift des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie, 8. Jg., Heft 7-8 (1905), S. 424-429.

- Gustav Schoenaich: Die Münchener Secession in Wien, in: Die Kunst für Alle. Malerei, Plastik, Graphik, Architektur, 10. Jg., Heft 8 (1894/95), S. 119-120.

- Brief verfasst von Alfred Roller an den Ausschuss der Genossenschaft der bildenden Künstler Wiens, unterzeichnet von Gustav Klimt, Carl Moll, Rudolf Bacher, Ernst Stöhr, Johann Victor Krämer, Joseph Maria Olbrich, u.a., Austrittsgesuch (05/24/1897). Mappe Gustav Klimt, .

- Brief von Alfred Roller in Wien an Gustav Klimt in Wien (19.04.1898). GKA46.

- Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Zeitschrift der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 2. Jg., Heft 1 (1899), S. 6-7.

- Horst-Herbert Kossatz: Der Austritt der Klimt-Gruppe. Eine Pressenachschau, in: Alte und moderne Kunst. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Kunst, Kunsthandwerk und Wohnkultur, 20. Jg., Heft 141 (1975), S. 23-26.

- Bernhard Denscher: Zensurfall Klimt. Austrian Posters. Beiträge zur Geschichte der visuellen Kommunikation. www.austrianposters.at/2018/04/14/zensurfall-gustav-klimt/ (09/01/2022).