Emperor Francis Joseph I

Portrait of Emperor Franz Joseph I (detail), around 1900, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Xylograph after Ernst Hartmann: The Imperial Family, Emperor Franz Joseph, Empress Elisabeth, Crown Prince Rudolf, around 1870

© Wien Museum

Francis Joseph I was the Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary. An absolute monarch at first, he later ruled as a constitutional sovereign. He shaped the Austro-Hungarian monarchy and acted as a political figure of integration for the multiethnic state and as a patron of the arts and sciences.

As a statesman the emperor was confronted with many significant political events during his long reign from 1848 until his death in 1916.

Following the revolutionary events of 1848, he introduced neo-absolutism into the Habsburg monarchy as a young regent aged merely 18. In 1854 he married Elizabeth Amalia Eugenia of Wittelsbach, the Duchess in Bavaria, who would later become famous as Empress Sisi.

The military defeats of Solferino in 1859 and Königgrätz (now Hradec Králové) in 1866, as well as the tensions with Hungary forced the absolutist and centralist ruler to reach a compromise with Hungary in 1867 and thus to establish a dual monarchy. However, a modern existence, with all of the monarchy’s ethnicities living on an equal footing, was thwarted by the emperor’s conservative policies. The alliance with the German Empire in 1879 and its expansion into a Triple Alliance in 1882 were unable to strengthen the monarchy against the rising movement of Pan-Slavism in the long run.

The emperor’s private life was by no means stable either. Starting in 1885, he was involved in an extramarital liaison with court actress Katharina Schratt. With the suicide of Crown Prince Rudolf at Mayerling in 1889, the succession passed to his brother’s line. In the years to come, Francis Joseph I suffered further personal losses. In 1867 his brother Ferdinand Max, King of Mexico, was shot dead, and in 1898 his wife, Empress Elizabeth, was murdered.

The annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1908 further exacerbated the situation. Although Emperor Francis Joseph I had always rejected a pre-emptive strike against Italy and Serbia, he now issued a declaration of war against Serbia, following the assassination of heir to the throne Francis Ferdinand and his wife Sophie in Sarajevo. This sealed the outbreak of World War I in 1914.

Golden Cross of Merit with Crown

© Dorotheum Vienna, Auction catalog 17.11.2017

The Emperor as a Patron

Emperor Francis Joseph I was known as a faithful patron of the arts and sciences who regularly purchased paintings at the Künstlerhaus exhibitions. As early as 1885, the “Künstler-Compagnie” around Klimt was involved in the decoration of the Hermes Villa, a gift to Empress Elizabeth.

The architectural design of Vienna’s Ringstraße, a project initiated by the Emperor, provided a wide field of work for many artists. In 1886, Klimt’s “Künstler-Compagnie” was commissioned to decorate the new Imperial-Royal Court Theater (now Burgtheater) with ceiling paintings. Emperor Francis Joseph I was so enthusiastic about these works that he awarded Gustav Klimt and his two colleagues the Golden Cross of Merit with the Crown in 1888.

Around the same time, Gustav Klimt painted the gouache Auditorium of the Old Burgtheater (1888, Wien Museum, Vienna). It shows the emperor in his box as the central figure, surrounded by numerous portraits of celebrities. At the annual exhibition of the Künstlerhaus in 1890, Klimt was honored with the Emperor’s Prize for this work, an award that came with a substantial amount of money and was funded from the emperor’s private purse. That same year, the “Künstler-Compagnie” was commissioned to decorate the staircase of the Imperial-Royal Court Museum (now Kunsthistorisches Museum).

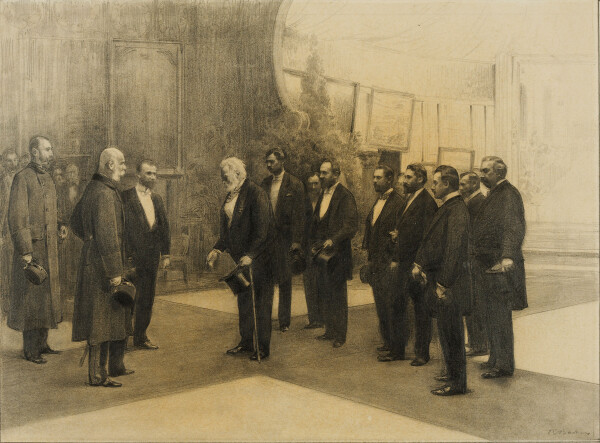

Rudolf Bacher: Emperor Franz Joseph visits the first exhibition of the Vienna Association at the Gartenbaugesellschaft, 1898, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Wiener Werkstätte card no. 162, Josef Divéky: Emperor Franz Joseph I, 1908, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

The Emperor and the Secession

On 1 March 1898, the emperor received a delegation from the Secession consisting of Honorary President Rudolf von Alt, President Gustav Klimt, and Carl Moll. They presented the new association’s program. On 5 April 1898, Francis Joseph visited the first exhibition of the young association, which was presented in the Horticultural Society’s flower showrooms. Rudolf Bacher documented how Klimt received the emperor and showed him around the premises in the form of drawings. However, Francis Joseph refused to make any purchases at the exhibition, despite the Secession’s repeated requests. He preferred the more traditional Künstlerhaus for the expansion of his personal collection.

That same year, Secession member Otto Wagner, with the assistance of Joseph Maria Olbrich, completed the imperial waiting room at the Hietzing Court Pavilion as part of the urban renewal project for the Vienna Stadtbahn, an urban railway system.

As a result of the Secession’s efforts to establish a gallery for contemporary art, in June 1902, the emperor approved the temporary accommodation of the so-called Modern Gallery in the rooms of the Lower Belvedere. In the Imperial Jubilee Year of 1908, mainly members of the so-called Klimt Group, who had left the Secession in 1905, were commissioned to create works for the Emperor’s Jubilee Procession.

Emperor Francis Joseph I died on 21 November 1916 after a short illness, at a time when the situation seemed to be changing in favor of the monarchy. Contemporary accounts testify that Gustav Klimt took part in the emperor’s solemn funeral ceremony.

Literature and sources

- Wien Geschichte Wiki. Altes Burgtheater. www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Altes_Burgtheater (03/24/2020).

- Die Welt der Habsburger. Franz Joseph I. www.habsburger.net/de/personen/habsburger-herrscher/franz-joseph-i (03/24/2020).

- Österreichisches Biographisches Lexikon. www.biographien.ac.at/oebl/oebl_F/Franz-Joseph__1830_1916.xml (03/25/2020).

- Julia Teresa Friehs: Vom Kunstskandal zur Austro-Trademark. Gustav Klimt. www.habsburger.net/de/kapitel/vom-kunstskandal-zur-austro-trademark-gustav-klimt (03/24/2020).

- Austrian Posters. Beiträge zur Geschichte der visuellen Kommunikation. www.austrianposters.at/2018/04/14/zensurfall-gustav-klimt/ (09/01/2022).

- Mona Horncastle, Alfred Weidinger: Gustav Klimt. Die Biografie, Vienna 2018.

- Beatrix Kriller, Georg Kugler: Das Kunsthistorische Museum. Die Architektur und Ausstattung: Idee und Wirklichkeit des Gesamtkunstwerkes, Vienna 1991.

- Sieglinde Baumgartner: Broncia Koller-Pinell. 1863-1934. Eine österreichische Malerin zwischen Dilettantismus und Profession. Dissertation, Salzburg 1989, S. 38.

- Brief des k. k. Ministeriums für Cultus und Unterricht in Wien an Gustav Klimt in Wien, unterschrieben von Paul Gautsch von Frankenthurn (10/31/1888). GKA70.

- Brief der k. und k. Generaldirection der A. H. Privat und Familien-Fonde in Wien an Gustav Klimt in Wien, unterschrieben von Hofzahlmeister Mayr (04/26/1890). GKA71.

- Akkord-Protokoll betreffend die Ausschmückung des Stiegenhauses im k. k. Kunsthistorischen Museum, unterschrieben von Franz Matsch, Gustav und Ernst Klimt und Mitgliedern des Hof-Bau-Comités (02/28/1890). AT-OeStA/AVA Inneres MdI STEF A Hofbauk. 40.33 fol. 2+3, .

- Akt der Generaldirektion der Privat- und Familienfonde betreffend die I. Secessionsausstellung (04/09/1898-06/16/1898). ÖStA/HHStA GDPFF_Zl. 1403/1898._2, .

- Brief der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs an den Kabinettsdirektor Kaiser Franz Josephs I, unterschrieben von Gustav Klimt als Präsident (04/07/1898). ÖStA/HHStA GDPFF Zl. 1403/1898_1, .