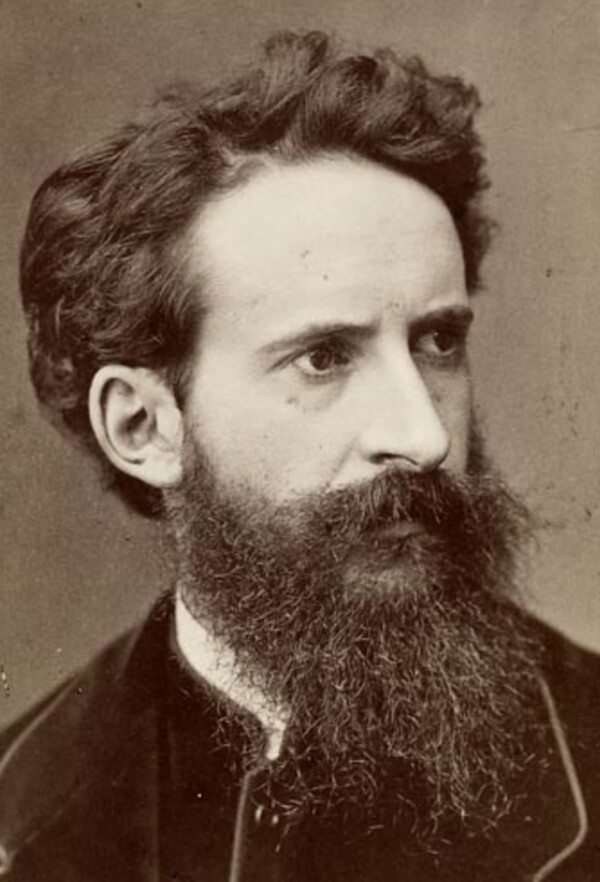

Hans Makart

Hans Makart photographed by Fritz Luckhart, around 1879

© Wien Museum

The academic painter Hans Makart established himself as one of the most important artists in Vienna in the late 19th century. With the organization of the Imperial Procession, he affirmed his standing as a celebrated master painter. After Makart’s death in 1884, Gustav and Ernst Klimt together with Franz Matsch completed most of his unfinished commissions.

The painter Hans Makart was born in Salzburg on 28 May 1840. His artistic talent was soon recognized in school. The young painter was supported by his drawing teacher Josef Mayburger and by the painter Johann Fischbach, who managed the Kleine Akademie in Salzburg. Makart was primarily trained in graphic art. In his spare time, he earned money by retouching photographs at a photo studio in Salzburg. In 1858, he attended the preparatory class of the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts with the intention of becoming a painter. The aspiring artist was considered untalented, however, and was soon expelled. He decided to move to Munich to continue his education there, studying with the history painter Karl Theodor von Piloty at the local Academy of Fine Arts until 1865.

Breakthrough and Return to Vienna

Hans Makart, who had been trained as a classic, academic history painter, gradually developed his own style after completing his studies. Inspired by fashionable salon pictures with erotic motifs, which he had seen at the London World’s Fair (1862), Makart created paintings that displayed an erotic sensuality, executed in shining colors. His sensual style was much criticized, but eventually led to Makart’s breakthrough.

His monumental triptych The Plague in Florence (1868, Museum Georg Schäfer, Schweinfurt) was too morbid and decadent for contemporary audiences in Munich. The nude depictions of women provoked a scandal. His deviation from correct spatial and anatomical representations in order to increase the overall dramatic effect of the painting was described as erroneous. While Makart’s new style was rejected by the conservative public, his modern shapes met with approval. 40 years later, Gustav Klimt would face similar reactions in the scandal surrounding his Faculty Paintings.

The Plague in Florence, 1868

Hans Makart's studio at Gußhausstraße 25 photographed by Viktor Angerer, around 1880

© Wien Museum

Hans Makart with artists at a costume party photographed by Viktor Angerer, around 1879

© Wien Museum

Rudolf von Alt: Library in Palais Dumba furnished by Hans Makart, 1877, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

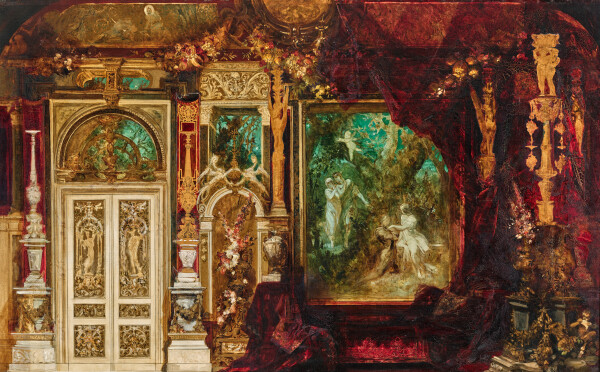

Hans Makart: Decoration design for Empress Elisabeth's bedroom in the Hermes Villa, 1882, Belvedere, Vienna

© Belvedere, Vienna

In 1869, Emperor Franz Joseph I took notice of the young painter and ordered him to return to his hometown and to work for the Viennese Court. At public expense, Makart was granted use of the former studio of the painter Anton Dominik von Fernkorn on Gußhausstraße as well as a house for him to live in. His studio would soon become an opulent space of representation and the venue of a variety of costume parties for artists and members of Vienna’s nobility. The pompous style in which the studio was decorated, recalling theater sets, became known as Makart’s Style and was emulated in many private homes.

Despite the Emperor’s support, Makart did not initially receive any official public commissions, which is why he focused on private commissions. He created erotic, theatrically idealized portraits of the ladies of the bourgeois high society. In 1870, he decorated the study at the city palace of the wealthy industrialist Nikolaus Dumba. A few years later, Gustav Klimt would decorate its music room.

Three years later, the art dealer Hugo Othmar Miethke helped the rising artist to stage his works at the Vienna Künstlerhaus. The individual presentation of Makart’s painting Venice Pays Homage to Caterina Cornaro (1872/73, Belvedere Vienna) at the main wall and the theatrical decoration of the entire room with props was a completely new exhibition concept. The staging of his works and of his own persona as a master painter would become indispensable to his further artistic creativity.

In 1879, Makart was appointed professor for history painting at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts. In the following year he took a leading role in the Cooperative of Visual Artists in Vienna (Künstlerhaus), having thus irrevocably established himself on the Viennese scene as a painter of great renown.

Makart and the “Künstler-Compagnie”

The commission to organize the procession to commemorate the 25th wedding anniversary of the Imperial Couple in 1879, for which Makart was given honorary citizenship of the city of Vienna, represented the apex of his career. While it has been repeatedly stated that the Klimt brothers and Franz Matsch also contributed to the procession directed by Makart, there is no evidence of such a collaboration. What is certain, however, is that the members of the so-called “Künstler-Compagnie” were “diligent visitors” at the master’s studio. Franz Matsch recorded in his autobiographical notes that he and Gustav and Ernst Klimt saw the master painter leave his studio on several occasions but never contacted him directly.

In the 1880s, Makart received two prestigious commissions. He was to decorate the bedroom of Empress Elisabeth at the Hermesvilla with ceiling frescoes and, in 1881, he was commissioned to design and execute the decorations for the stairwell of the newly built Kunsthistorisches Museum. The master painter thus finally received his long-awaited public commission and was given the opportunity to leave his mark on the Ringstraße buildings.

Makart was unable to complete either commission, however, since he died aged only 45 on 28 May 1884. While the fully executed lunette paintings were attached to the ceiling of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, the large ceiling painting The Victory of Light over Darkness: Apollo Casting Ignorance into the Abyss (1883/84, Belvedere Vienna) remained a design that was never executed. The fresco painter Mihály von Munkácsy created the central painting, while Franz Matsch and Gustav and Ernst Klimt were commissioned to decorate the remaining spandrels and intercolumnar spaces. The three young artists also completed the decorations for the Empress’s bedroom at the Hermesvilla, on which Makart had already begun working.

Literature and sources

- Wien Geschichte Wiki. Hans Makart. www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Hans_Makart (03/27/2020).

- Sandra Tretter, Hans-Peter Wipplinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Jahrhundertkünstler, Ausst.-Kat., Leopold Museum (Vienna), 22.06.2018–04.11.2018, Vienna 2018, S. 20, S. 24, S. 196.

- Otmar Rychlik: Gustav Klimt Franz Matsch und Ernst Klimt im Kunsthistorischen Museum, Vienna 2012, S. 9-13.

- Herbert Giese: Franz von Matsch – Leben und Werk. 1861–1942. Dissertation, Vienna 1976, S. 7.

- Ralph Gleis (Hg.): Makart. Ein Künstler regiert die Stadt, Ausst.-Kat., Vienna Museum (Vienna), 09.06.2011–16.10.2011, Munich 2011.

- Max Eisler: Gustav Klimt, Vienna 1920, S. 6-7.

- N. N.: Die Bilanz des Festzuges, in: Leitmeritzer Zeitung, 10.05.1879, S. 406.

- N. N.: Hans Makart, in: Prager Tagblatt, 30.04.1879, S. 7.

- N. N.: Salzburger Nachrichten.. Hans Makart vermählt, in: Salzburger Volksblatt: unabh. Tageszeitung f. Stadt u. Land Salzburg, 02.08.1882, S. 2.

- Tobias G. Natter, Franz Smola, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Klimt persönlich. Bilder – Briefe – Einblicke, Ausst.-Kat., Leopold Museum (Vienna), 24.02.2012–27.08.2012, Vienna 2012.

- Günter Meissner, Andreas Beyer, Bénédicte Savoy, Wolf Tegethoff: Allgemeines Künstler-Lexikon. Die bildenden Künstler aller Zeiten und Völker, Band LXXXVI, Berlin - New York 2015, S. 420.

- Hans Vollmer (Hg.): Allgemeines Lexikon der Bildenden Künstler von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart. Begründet von Ulrich Thieme und Felix Becker, Band XXIII, Leipzig 1929, S. 583.