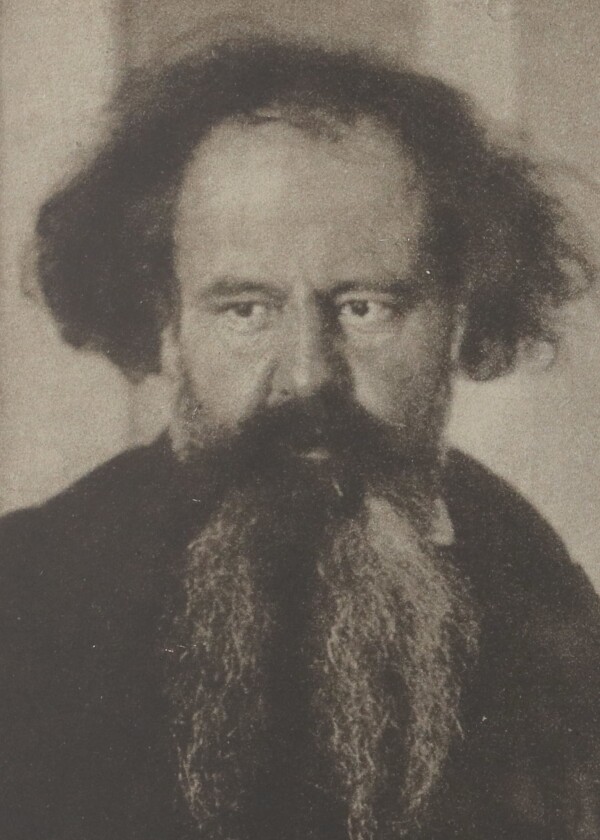

Hermann Bahr

Hermann Bahr photographed by Friedrich Viktor Spitzer, in: Photographische Rundschau und photographisches Centralblatt. Zeitschrift für Freunde der Photographie, 22. Jg., Heft 3 (1908).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

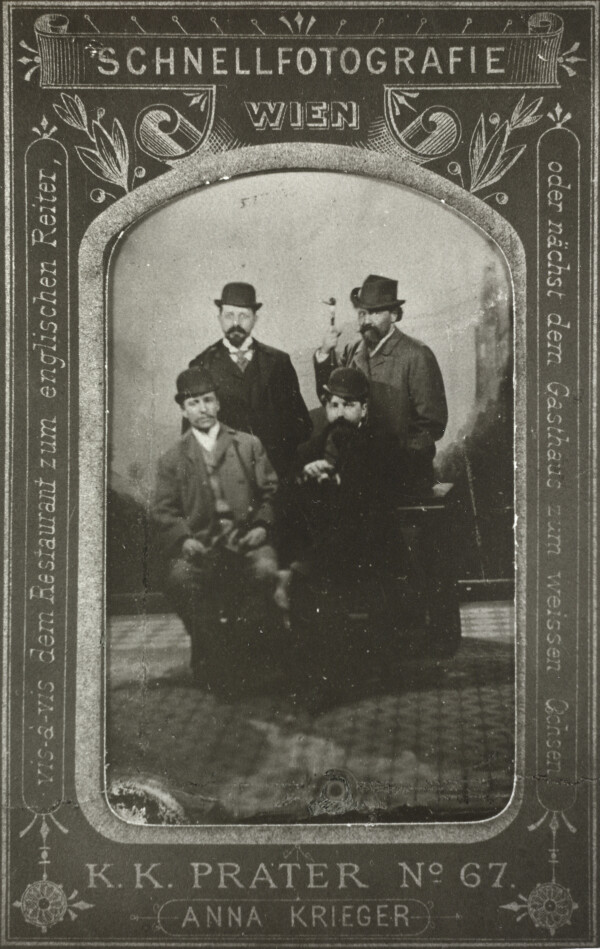

The "Young Vienna" group: standing Richard Beer-Hofmann and Hermann Bahr, seated Hugo von Hoffmannsthal and Arthur Schnitzler photographed by Anna Krieger, around 1895, Austrian National Library, Vienna

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

The Austrian poet, writer, playwright, essayist, and theater and literary critic Hermann Bahr is considered a key figure on the Viennese art and cultural scene of the fin de siècle and a pioneer of modernism.

Hermann Bahr was born in Linz on 19 July 1863. He attended the Akademisches Gymnasium in Linz and the Benediktiner-Gymnasium in Salzburg and then moved to Vienna to study classical philology, law, and economics. Bahr began to frequent German nationalist circles and was among the followers of Georg Ritter von Schönerer. Due to an anti-Semitic speech he delivered as a member of a German nationalist fraternity named Albia during a commercium held to mourn the death of Richard Wagner in 1883, he was expelled from the University of Vienna. He thus continued his studies in Graz and Czernowitz (now Chernivtsi) and in 1884 started attending lectures in philosophy, literature, and art history at the Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin, yet did not complete his studies.

Bahr undertook journeys to France, Spain, Morocco, Russia, and Italy and from 1882 onward worked as a journalist for various journals and publishing houses. Especially his stay in Paris in 1888/89 informed his embrace of art and modernism. In 1889 a first compilation of his magazine contributions appeared under the title of Zur Kritik der Moderne [“On the Critique of Modernism”]. The subsequent year he joined the Freie Bühne in Berlin, where he became friends with Josef Kainz and Arno Holz. As professional success failed to materialize, he returned to Vienna in 1894, where he established himself as a writer, theater critic, and playwright. He left the Roman-Catholic church and in 1895 married the Jewish actress Rosalia (Rosa) Jokl.

Bahr met Peter Altenberg, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Arthur Schnitzler, Felix Salten, and Richard Beer-Hofmann and became the central figure of the literary circle Jung-Wien, whose members regularly met at the Café Griensteidl. He was considered the mouthpiece of the modern literature movement and published a collection of his reviews in 1891 under the title of Die Überwindung des Naturalismus [“Overcoming Naturalism”].

An encounter with Theodor Herzl in Paris, whose Zionist movement he subsequently endorsed, seems to have influenced his book Der Antisemitismus. Ein internationales Interview [“Anti-Semitism. An International Interview”], which he wrote in 1894. That same year, Bahr founded the weekly periodical Die Zeit together with Heinrich Kanner and Isidor Singer, where he was in charge of the arts section. He also worked for the Deutsche Zeitung and wrote theater reviews for the Österreichische Volks-Zeitung and the Neues Wiener Tagblatt. As Bahr skillfully positioned himself on the cultural scene with his activities, Karl Kraus became one of his most severe critics and frequently attacked him in Die Fackel.

During the foundation of the Vienna Secession, Hermann Bahr supported the renewal of art and appeared as the programmatic artists’ association’s advocate. In the first three years he was also a member of the literary advisory committee of Ver Sacrum, the Secession’s official magazine. Moreover, he penned reviews in which he particularly praised Klimt’s painting. In the context of the “IV. Secessionsausstellung” [“4th Secession Exhibition”] in 1899 he referred to one of the artist’s overdoors for the Dumba Palace, entitled Schubert on the Piano (1899, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945), as:

“[…] the most beautiful picture ever painted by an Austrian.”

Josef Löwy: Schubert at the piano, 1899, MAK - Museum of Applied Arts

© MAK

Josef Maria Olbrich: Villa Bahr, Winzerstraße 22, 1130 Vienna, in: Der Architekt. Wiener Monatshefte für Bau- und Raumkunst, 6. Jg. (1900).

© ANNO | Austrian National Library

Aura Hertwig (?): Insight into the Villa Bahr, circa 1905, Theatermuseum, Wien

© KHM-Museumsverband

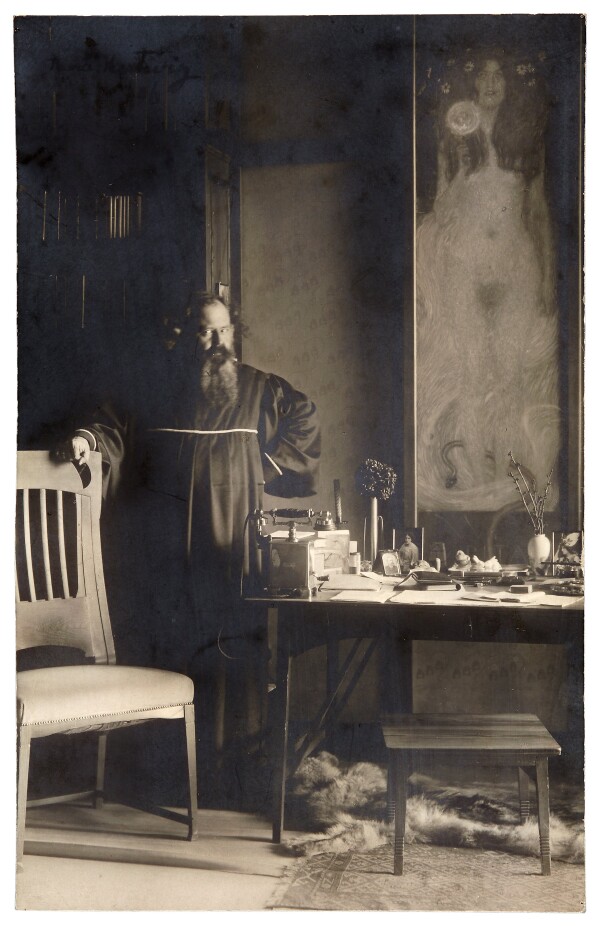

In 1900, Bahr entrusted Josef Maria Olbrich with the design of his villa in the suburb of Ober Sankt Veit, and he bought Klimt’s painting Nuda Veritas (1899, Österreichisches Theatermuseum, Vienna), a work controversially discussed in public. It was prominently placed on a wall in his study. In the door to this room, he also integrated Klimt’s drawing Witch in a small frame. The villa became a meeting point for artists, including Klimt, Otto Wagner, and Gustav Mahler, among others.

In 1901, Bahr said about Klimt in a libel suit against Kraus:

“There is nothing in the world I like more than pictures by Klimt. Through my standing up for his pictures, Klimt and I have become close friends, and I have become his confidant.”

That same year, Bahr held his Rede über Klimt [“Speech on Klimt”] at the Concordia association of writers. He warned that under the prevalent conditions modern art in Austria would run the risk of being destroyed through arbitrary interference. He also took a firm stand on Klimt’s Faculty Paintings, which the government had commissioned from the artist for the University of Vienna’s assembly hall, defending the freedom of artistic expression with the backing of Ludwig Hevesi and Berta Zuckerkandl. In 1903 Bahr collected negative press commentaries and published them under the title of Gegen Klimt [“Against Klimt”].

Besides his work as a journalist, Bahr wrote numerous theater plays and became a leading creative mind of the Salzburg Festival. From 1906 on he worked as a stage director for Max Reinhardt at the Deutsches Theater in Berlin. At the time he met the opera singer, director, and Wagner interpreter Anna Bellschan von Mildenburg. They married after Bahr’s divorce from his first wife, and three years later the couple moved to Salzburg.

As were many intellectuals at the time, Bahr was in favor of Austria’s entry into World War I. Although having been criticized as being “reactionary,” he sought to do justice to the current discourse on art with his work Expressionismus, which appeared in 1916 and in which he stood up for this latest artistic movement. He presented himself as open-minded toward all literary movements, from naturalism to expressionism, writing novels and penning journals of historico-cultural relevance. After World War I, however, his work was marked by a conservative streak and the return to Catholicism. Hermann Bahr worked as a dramaturge at the Vienna Burgtheater and in 1922 moved to Munich, where he spent the last years of his life in illness and suffering from dementia. He died on 15 January 1934.

Literature and sources

- Hermann Bahr: Rede über Klimt, Vienna 1901, S. 13.

- Hermann Bahr: Gegen Klimt, Vienna 1903.

- Hermann Bahr: Tagebuch 1918, Innsbruck 1919, S. 40.

- Österreichische Biographisches Lexikon. Hermann Bahr. www.biographien.ac.at/oebl/oebl_B/Bahr_Hermann_1863_1934.xml (09/14/2020).

- Markus Kristan: Kunstschau Wien 1908, Vienna 2016, S. 214-215.

- Wien Geschichte Wiki. Hermann Bahr. www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Hermann_Bahr (04/08/2020).

- Hermann Bahr. Österreichischer Kritiker europäischer Avantgarden. www.univie.ac.at/bahr/ (04/08/2020).

- Hermann Bahr: Secession, Vienna 1900, S. 120, S. 123.

- Eduard Pötzl: Gerichtssaal. Ein Ehrenbeleididungsproceß, in: Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 24.02.1901, S. 6-8.

- N. N.: Lese-Abend der »Concordia«, in: Neue Freie Presse, 26.03.1901, S. 5.

- Jarmila Weißenböck: Das Haar der Nuda Veritas. Hermann Bahr und seine Klimts, in: Parnass, 20. Jg., Heft 17 (2000), S. 116-117.

- Markus Neuwirth: Hermann Bahr und Gustav Klimt. Exotismus als Fluchtpunkt, in: Jeanne Benay, Alfred Pfabigan (Hg.): Hermann Bahr – für eine andere Moderne, Berne 2004.

- Werner Hanak: Von Bärten und Propheten. Oder: Theodor Herzl, Hermann Bahr und die Folgen des »antisemitic turns« der Wiener 1880er Jahre, in: Elana Shapira (Hg.): Design Dialogue. Jews, Culture and Viennese Modernism, Vienna 2018, S. 313-328.

- Kurt Ifkovits: forum oö Geschichte. Virtuelles Museum Oberösterreich. Hermann Bahr. www.ooegeschichte.at/themen/kunst-und-kultur/literaturgeschichte-oberoesterreichs/literaturgeschichte-ooe-in-abschnitten/19-fruehes-20-jahrhundert/hermann-bahr/ (10/19/2021).

- Brief von Gustav Klimt an Hermann Bahr (17.11.1897). HS_AM19666Ba.

- Ludwig Hevesi: Villa Bahr. Juni 1900, in: Acht Jahre Sezession (März 1897–Juni 1905). Kritik – Polemik – Chronik, Vienna 1906, S. 512-516.