Berlin Secession

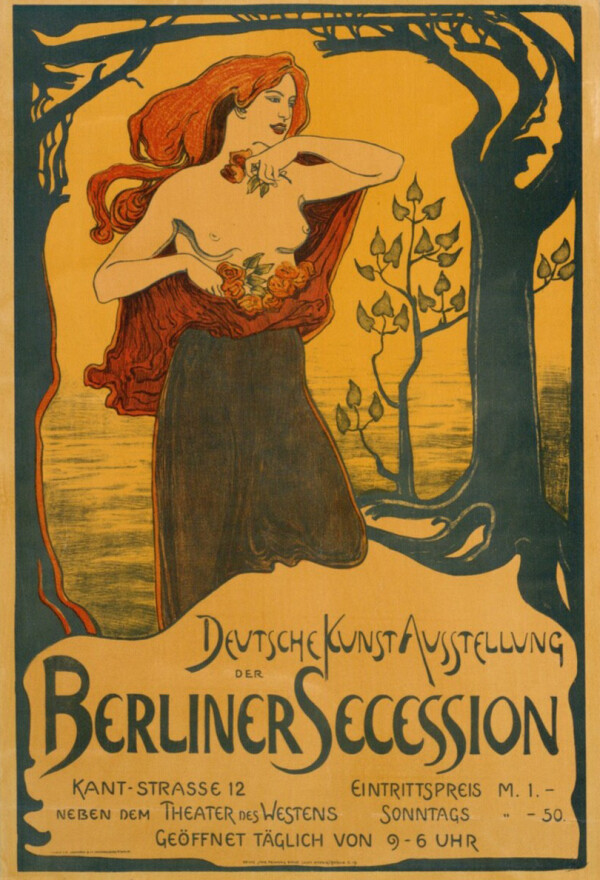

Ludwig von Hofmann: Poster of the German Art Exhibition in Berlin Association, 1899, The Albertina Museum, Vienna

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

Exhibition building of the Berlin Association at Kantstraße 12, around 1899, in: Die Kunst für Alle. Malerei, Plastik, Graphik, Architektur, 14. Jg. (1898/99).

© Heidelberg University Library

Insight into the III exhibition of the Berlin Association, 1901, in: Die Kunst für Alle. Malerei, Plastik, Graphik, Architektur, 16. Jg. (1900/01).

© Heidelberg University Library

Thomas Theodor Heine: Poster of the 26th exhibition of the Berlin Association, 1913, The Albertina Museum, Vienna

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

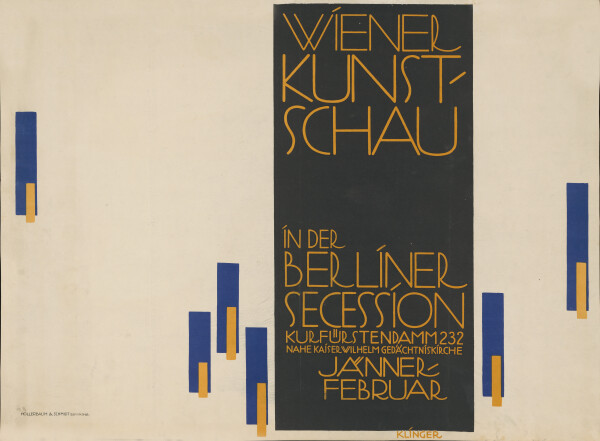

Julius Klinger: Poster of the Vienna Art Show in Berlin Association, 1916,

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek

Arising as a protest movement against prevalent artistic tradition and exhibition practice, the Berlin Secession came together as a modern, liberal association of artists led by Walter Leistikow and Max Liebermann.

The Berlin Secession association of artists was officially founded in early 1899, following the example of the Munich Secession. A protest movement, it positioned itself against a conventional and historicizing understanding of art. The founding of the association had been preceded by tensions on the Berlin art scene. When conservative members of the Society of Berlin Artists forced a special exhibition devoted to Edvard Munch to close its doors in 1892, Walter Leistikow, Franz Skarbina, and Max Liebermann initiated the formation of the first independent group of artists, which called itself Die Elf [The Eleven]. In the years to come, several more such small artists’ groups were formed, increasingly dividing up the Berlin art community.

As early as 1898, there were initial discussions about founding a Berlin Secession, as more and more works by progressive modern artists had been rejected by the exhibition jury. A list of potential members drawn up in the fall of 1898 has long been regarded as the birth of the Berlin Secession, but is actually to be seen as a first concrete proposal rather than a founding document.

It was not until January of the following year that the newspapers announced the official foundation of the Berlin Secession, whose first president was Max Liebermann. Winning the art dealers Bruno and Paul Cassirer over as members functioning as secretary and managing director ensured a solid economic basis. Numerous Austrian artists, including Gustav Klimt, Eugen Jettel, Emil Orlik, Carl Moll, and Arthur Strasser, were appointed corresponding members.

When it became clear that the young association would be refused participation in the “Große Berliner Kunstschau” [“Great Berlin Art Exhibition”], it finally broke away from the Society of Berlin Artists. As early as May, the Berlin Secession’s first exhibition took place in the newly constructed exhibition building, then still located on Kantstraße.

Works by international artists such as Pissarro, Renoir, Segantini, and Whistler, as well as Kandinsky, Manet, Monet, and Munch, were presented in the coming summer and winter exhibitions. The Berlin Secession opened itself to all styles and directions, as well as foreign art, which Berlin an international art metropolis alongside Munich. However, this opening up, in addition to conflicting interests with regard to the personal representation of some Secession members through art dealer Paul Cassirer, led to a number of more conservative members leaving in 1902. The first exhibition of the “purified” association outside Berlin was to follow in May.

A Time of Crisis and Further Secessions

A long-standing problem for the Berlin Secession was the dual membership of its members. Many of the association’s artists still belonged to the Society of Berlin Artists at the same time. The statutes were repeatedly amended in a futile attempt to prevent this duality. A sense of injustice that was not least due to the aforementioned conflict over Paul Cassirer led to another split in 1910. The New Secession was founded under Max Pechstein, yet the conflicts within the Berlin Secession remained. After numerous reshuffles at board level, including the resignation of Liebermann as president, who was replaced by Lovis Corinth, the association finally split in 1914. Liebermann, Slevogt, and Cassirer left the Berlin Secession to found the Free Secession. Following the collapse of the new association in 1925, many artists, however, rejoined the Berlin Secession.

After the Berliner Secession almost dissolved in 1933 due to its precarious financial situation, the political situation under the Nazi regime led to the expulsion of all Jewish members. Deprived of a suitable venue for exhibitions and meetings, the Berlin Secession came to an end in 1937.

Klimt and the Berliner Secession

On the one hand, Klimt was connected to the Berlin Secession through his affinity with fellow German artists like Max Liebermann and Hermann Muthesius, as well as the Cassirer art dealers. On the other hand, he took part in a total of five exhibitions of the Berlin Secession as a corresponding member between 1905 and 1916.

In 1905, the Berlin Secession presented the “II. Ausstellung des Deutschen Künstlerbundes” [“2nd Exhibition of the Union of German Artists”] to celebrate the opening of its new exhibition building on Kurfürstendamm. Gustav Klimt, who was a member of the association, was allowed to present a total of 13 works by his hand to the Berlin public in a separate room. Klimt even traveled to Berlin personally for the preparations of the show.

In 1907 he showed drawings at the Kunstsalon Paul Cassirer as part of the “XIV. Ausstellung der Berliner Secession” [“14th Exhibition of the Berlin Secession”], and in 1909 Portrait of Fritza Riedler was exhibited at the Berlin Secession’s 18th Exhibition.

In 1916 – in the middle of World War I – the Berlin Secession invited the artists from the “Wiener Kunstschau” to exhibit their works on Kurfürstendamm. Under the title “Wiener Kunstschau at the Berlin Secession,” 70 works by Austrian artists were on display, including Egon Schiele, Koloman Moser, Anton Faistauer, and Carl Moll. Among the five paintings Klimt sent to the show was his heavily reworked allegory Death and Life (Death and Love) (1910/11, reworked 1912/13 and 1916/17, Leopold Museum, Vienna).

Literature and sources

- Deutscher Künstlerbund. www.kuenstlerbund.de/deutsch/historie/deutscher-kuenstlerbund/deutscher-kuenstlerbund.html (04/27/2020).

- Pinakothek. www.pinakothek.de/kunst/gustav-klimt/die-musik (04/27/2020).

- Michael Michael: Gustav Klimt, Tod und Leben, 1910/11, umgearbeitet 1915/16 (LM Inv. Nr. 630). Dossier LM Inv. Nr. 630, Vienna 2016.

- Anke Matelowski: Die Berliner Secession 1899–1937. Chronik, Kontext, Schicksal, Wädenswil on Lake Zurich 2017.

- Ansichtskarte von Gustav Klimt in Berlin an Emilie Flöge in Wien (05/19/1905).

- Korrespondenzkarte von Gustav Klimt, verfasst von fremder Hand an Maria Cyrenius (11/16/1915).