Karl Kraus

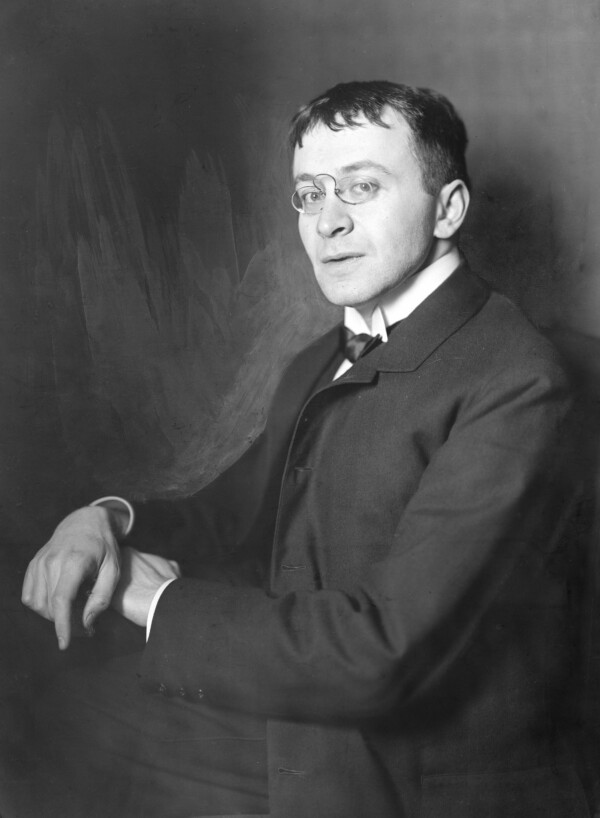

Karl Kraus photographed by Madame d'Ora, 1908, Austrian National Library, Vienna

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

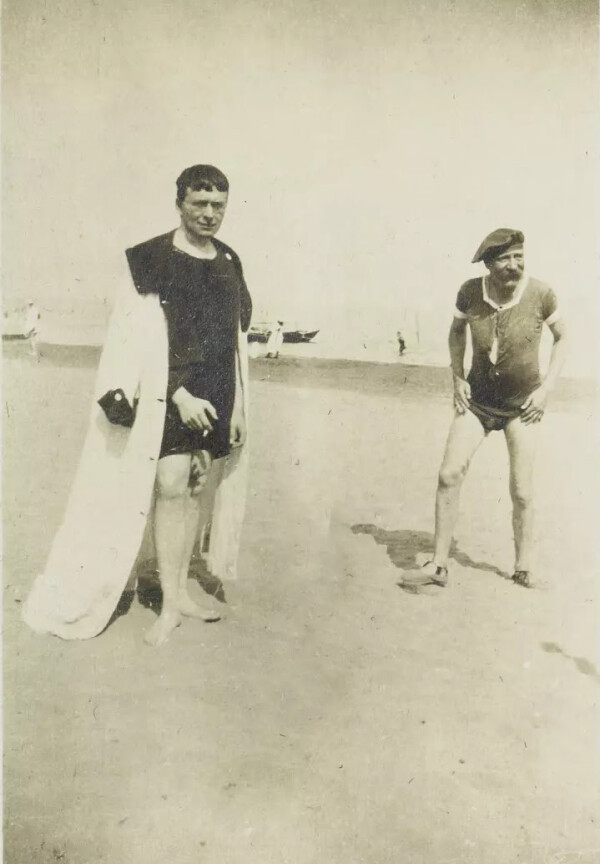

Karl Kraus and Peter Altenberg at the Lido, 1913, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

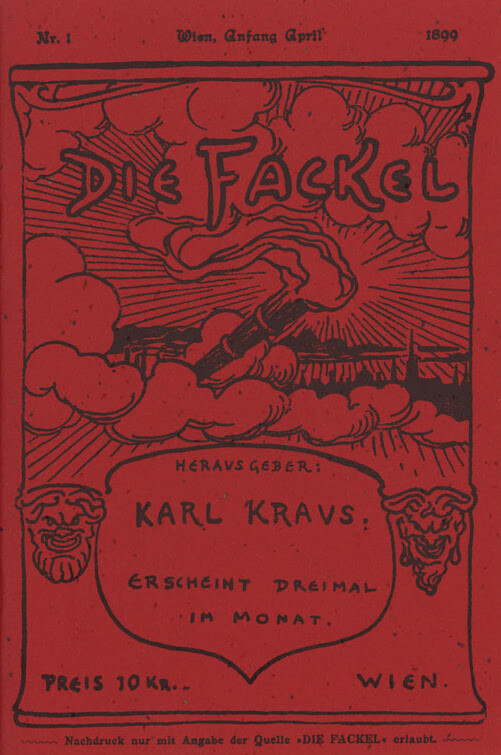

Cover, in: Die Fackel, 1. Jg., Heft 1 (1899).

© Heidelberg University Library

With his journal Die Fackel, which leveled criticism against culture and society, the publicist, dramatist, lyricist, satirist and cultural critic Karl Kraus was an important protagonist of his time. Commenting negatively on the Faculty Paintings in 1900, he took a clear stance against Gustav Klimt.

Karl Kraus was born the ninth child of a paper manufacturer in Bohemia. In 1877, the Jewish family moved to Vienna, where Kraus studied law from 1892. After two years, he changed over to the department of philosophy and German studies, but never graduated.

Contact and Break with the Circle of Viennese Writers

Already as a young student, Kraus sought contact with the Viennese literary scene. In the 1890s, he regularly frequented Café Griensteidl in Vienna’s inner city, which at the time was a popular meeting place amongst renowned writers, including Hermann Bahr, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Felix Salten, Arthur Schnitzler and Peter Altenberg. Kraus joined the literary circle Jung-Wien [Young Vienna] before vehemently opposing this society a few years later with his first extensive satire directed against literary cliques Die demolirte Literatur [The Demolished Literature].

A Wordsmith’s Polemic

Kraus soon started to work as a journalist and correspondent in Vienna, writing numerous articles and reviews for periodicals in the German-speaking world. At the age of 25, he started publishing his own journal: Die Fackel. It was issued regularly from 1 April 1899 until July 1904, and subsequently more sporadically until his death, counting more than 900 issues overall. Die Fackel became an eminent medium and forum of critical Viennese Modernism.

Criticism Against the Secession and Klimt

Via his journal, Kraus repeatedly expressed negative opinions about the art of the Vienna Secession. In an issue published in 1900, he described the “change in Viennese artistic taste” as follows:

“While people who admired Makart used to buy works by the Makart imitator Klimt, they now had to be trained to admire Khnopff so that they could purchase works by the Khnopff imitator Klimt; and who would wish to be portrayed by Herr Klimt in the Pointillist technique before knowing how much the paintings by Pointillists fetch in Western Europe? […].”

In 1900 and 1903, he ranted about Klimt’s controversial Faculty Paintings:

“Who cares how Herr Klimt imagines philosophy? An unphilosophical artist may well paint philosophy, but he must allegorize it the way it is painted in the philosophical minds of his time.”

Kraus further called Klimt a “stylistic eclecticist” as well as a “representative of a time of decay of true art which, instead of individualities, now only brings forth interesting individuals.”

The Last Days of Mankind

Contrary to many of his contemporaries, Kraus decidedly opposed World War I. He expressed his pacifist stance in his anti-war drama The Last Days of Mankind, which is considered his most important work today.

Kraus continued to use his literary influence during the time of the First Republic to raise awareness for and fight against the threat of National Socialism. However, he withheld his 300-page analysis of the National Socialists’ rise to power in Germany, Dritte Walpurgisnacht [The Third Walpurgis Night], which was only published after his death.

Obituary for the Highly Controversial “Fackel=Kraus”

The eloquent writer died in the early summer of 1936 at the age of 62 in Vienna. Though he was antagonistic towards the press all his life, his activities as an argumentative social and cultural critic, lyricist and reader were lauded by the print media. On 13 June 1936, the newspaper Der Tag issued the following statement:

“Karl Kraus erred a lot and battered, or wanted to batter, many an unsuspecting victim who did not deserve such treatment. […] But he invariably reacted with his whole temperament. […] Whenever he paused in his hatred and battles, his influence was positive and productive.”

Only a few days after his passing, he was laid to rest at Vienna Central Cemetery in a funeral which, according to his last will and testament, was to be devoid of any ceremony:

“Since my life was not a family affair – something that was rendered impossible by my work – I would like my passing not to be one either. I thus ask my relatives to stay away from my interment. That it shall remain a private affair, which will keep others away too, I may only hope but cannot guarantee. I would like to thank all my dear friends, known and unknown.”

The bulk of his estate – the Karl Kraus Archive – is kept today at the Wienbibliothek at Vienna City Hall.

Literature and sources

- Wien Geschichte Wiki. Karl Kraus. www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Karl_Kraus (03/04/2024).

- Österreichisches Biographisches Lexikon. Karl Kraus. www.biographien.ac.at/oebl/oebl_K/Kraus_Karl_1874_1936.xml (03/27/2020).

- Karl Kraus: Klimt, in: Die Fackel, 1. Jg., Heft 36 (1900), S. 16-20.

- Karl Kraus: Klimt’s »Jurisprudenz«, in: Die Fackel, 5. Jg., Heft 147 (1903), S. 10.

- Konstanze Fliedl, Marina Rauchenbacher, Joanna Wolf (Hg.): Handbuch der Kunstzitate: Malerei, Skulptur, Fotografie in der deutschsprachigen Literatur der Moderne, Band 1, Boston 2011, S. 465-467.

- Die Fackel. fackel.oeaw.ac.at/ (11/26/2021).

- Eigenhändiges Testament von Karl Kraus, verfasst am 27. und 28. August 1935. WStLA, Hauptarchiv-Akten, Persönlichkeiten, A1: K12 Karl Kraus, Fol. 4r.

- Der Tag, 13.06.1936, S. 5.

- Katharina Prager, Simon Ganahl (Hg.): Karl Kraus Handbuch. Leben - Werk - Wirkung, Vienna 2022.