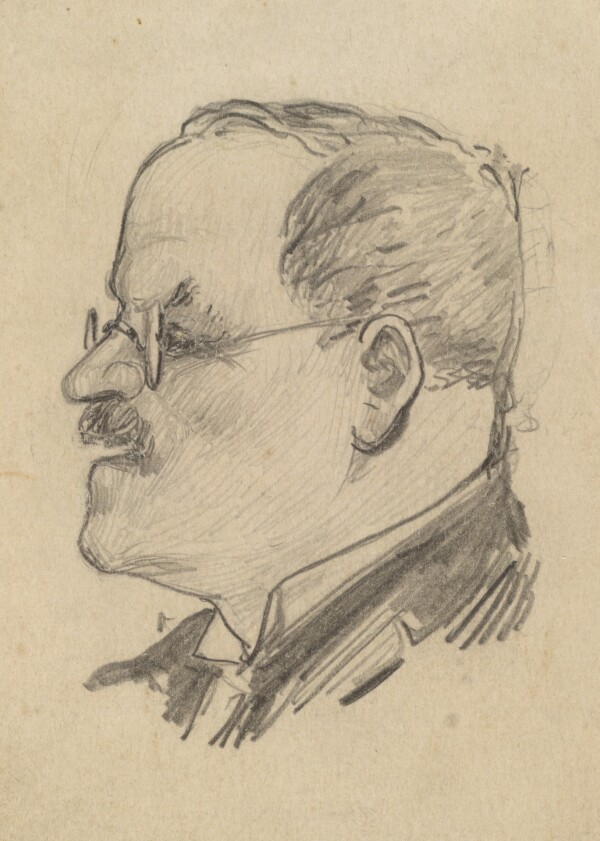

Maximilian Lenz

Maximilian Lenz drawn by Moriz Nähr

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

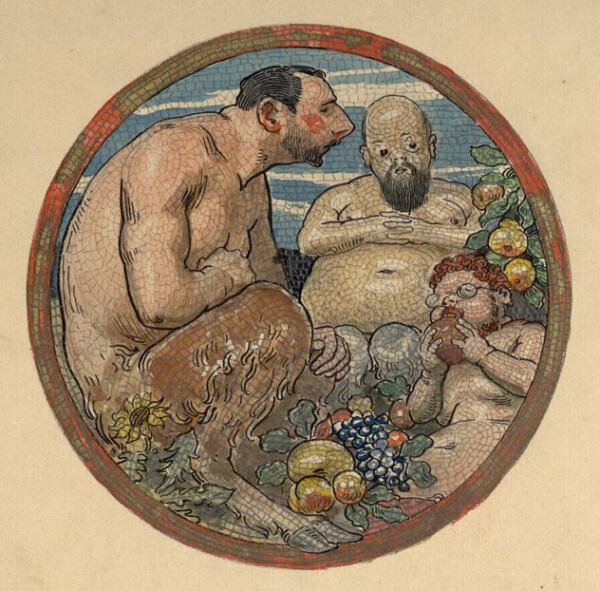

Maximilian Lenz: Mosaic tondo with Stolba, Böhm and Nowak as faun figures, around 1895, The Albertina Museum, Vienna

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

Moriz Nähr: Gustav Klimt with the artists participating in the 14th Exhibition of the Secession, April 1902, Klimt Foundation: Maximilian Lenz (reclining) with the artists involved in the Vienna Secession’s 14th Exhibition, photographed by Moriz Nähr, April 1902

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

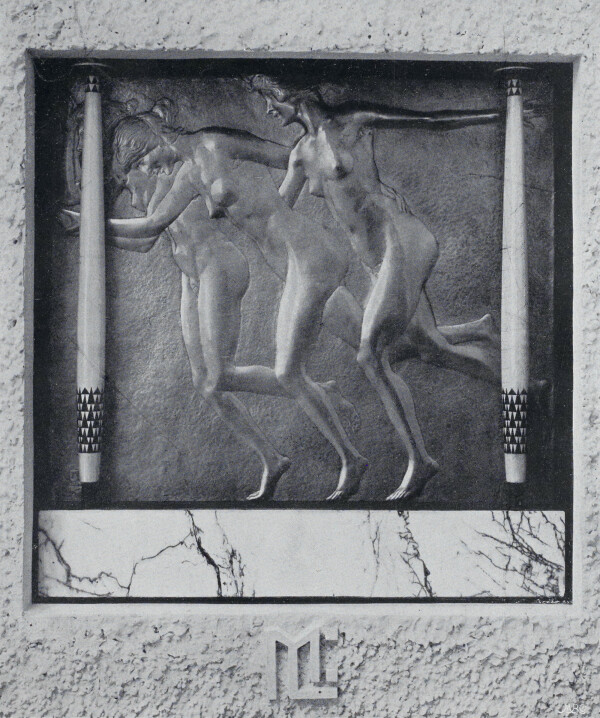

Maximilian Lenz: Chased brass relief mounted in marble and wood for the XIV Secession Exhibition photographed by Moriz Nähr, 1902, in: Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, Band 10 (1902).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Maximilian Lenz was primarily active as a painter and graphic artist, employing a wide variety of techniques and materials. In 1897 he was one of the co-founders of the Vienna Secession alongside Gustav Klimt. Within the association, he took part in numerous exhibitions and illustrated the magazine Ver Sacrum.

Maximilian Lenz was born in Vienna on 4 October 1860. Between 1874 and 1877 he studied at the Imperial-Royal School of Arts and Crafts under Michael Rieser and Ferdinand Laufberger. He attended Laufberger’s preparatory class for figure drawing in 1876/77 together with Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch. The latter he already knew from his childhood, as they had grown up in the same house at No. 23 Josefstädter Straße in Vienna’s 8th District. At the School of Arts and Crafts, Lenz probably also met Moriz Nähr, who later became known as the Vienna Secession’s photographer and with whom he developed a close friendship. In return for helping out with cleaning and errands, the two “apprentices” were allowed to use the studio of the painter Stefan (Istvan) Delhaes, who sometimes took them along on excursions.

Upon graduating from the School of Arts and Crafts, Lenz attended the Imperial-Royal Academy of Fine Arts under Carl Wurzinger, August Eisenmenger, and Christian Griepenkerl, receiving several scholarships. In 1886, the Kenyon Travel Scholarship took him to Rome for two years. In the early 1890s he even traveled to Buenos Aires together with the engraver Ferdinand Schirnböck to design banknotes for the central bank.

Networking in Vienna

It seems that Lenz returned to his native country in 1893. He became a member of the Cooperative of Visual Artists in Vienna (Künstlerhaus) in 1896. He was well connected and had been part of a loose group of artists known as the Hagengesellschaft since his student days, attending its meetings, which usually took place at the pub Zum blauen Freihaus or at Café Sperl, with the participants enjoying drawing witty caricatures of each other.

Together with Gustav Klimt, Kolo Moser, Josef Hoffmann, and others, he founded the groundbreaking Association of Austrian Artists Secession in 1897. He provided several illustrations for the association’s magazine Ver Sacrum and took part in exhibitions of the young artists’ association, which was committed to modernism. Its 14th Exhibition, which opened in 1902 and was innovative in terms of spatial art, was particularly significant. For this so-called “Beethoven Exhibition,” Lenz created, among other things, embossed brass plates featuring mythological motifs, which were embedded in the walls of the central hall. They blended in with the overall concept of the exhibition, at the center of which was Max Klinger’s Beethoven monument and for which Gustav Klimt had designed the Beethoven Frieze (1901/02, Belvedere, Vienna, on permanent loan to the Secession, Vienna).

Inspirations in Italy

In late November 1903, Maximilian Lenz undertook a trip to Italy in Klimt’s company, which, in his memoirs, he described as follows:

“Klimt was very dear as a person; I enjoyed the company of this dear friend on a journey through Northern Italy. [...] Ravenna, the actual destination, was reached; Gustav Klimt’s hour of destiny had arrived. For the shimmering golden mosaics of the Ravenna churches made a tremendous and crucial impression on him. From then on, the ostentatious, the rigidly magnificent came into his sensitive art.”

The Byzantine mosaics of Ravenna and San Vitale also impressed and influenced Lenz in his artistic work. He worked in a variety of techniques such as printmaking, mosaic, mortar carving, and chasing, but was primarily active as a painter. His style was based on Symbolism, and he was often inspired by the works and themes of his colleagues. His best-known paintings include A World (1899, Szépmuveszeti Múzeum, Budapest), The Sirk Corner (1900, Wien Museum, Vienna), Spring (1904, National Museum Wales, Cardiff), and Iduna’s Apples (1904, lost), as well as Justitia, the ceiling painting for the Palace of Justice, which was destroyed by fire in 1927.

In 1904, Lenz accepted a position as a drawing teacher with the Kupelwieser family, a dynasty of Austrian industrialists. His pupil was Ida Kupelwieser, the granddaughter of the painter Leopold Kupelwieser and a niece of the industrialist and patron Karl Wittgenstein; she probably posed for the latter painting.

Maximilian Lenz: Spring, 1904, Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales, Cardiff

© Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

Maximilian Lenz in front of his work "The Baptism of the Ethiopian" for the XXIV Secession Exhibition, center Josef Engelhart, right Friedrich König photographed by Moriz Nähr, 1905

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

The “Naturalist Wing”

When the Klimt Group broke away from the Vienna Secession in 1905 due to artistic differences, Lenz joined the “Naturalist Wing” – the so-called “Impressionists” – around Josef Engelhart, Rudolf Bacher, Alois Hänisch, and Ferdinand König. Engelhart, Hänisch, and König were also his friends, and they shared a studio at No. 112 Landstraßer Hauptstraße, which Engelhart had received as a dowry on the occasion of his marriage to Dorothea Mautner-Markhof. Lenz mainly exhibited his paintings at the Vienna Secession; he worked on a compilation of wall charts published by the Imperial-Royal State Printing Press, which appeared as color lithographs between 1903 and 1926, and designed posters for war bonds during World War I.

Although Lenz and Klimt parted ways artistically, they probably continued to be friends for many years. He condoled with Klimt on the occasion of his mother’s death, as is documented by a thank-you letter from 1915:

"Dear Lenz! I thank you most sincerely for your kind letter – for your sympathy. I apologize for the somewhat belated thanks. With my best regards, Gustav Klimt.”

Maximilian Lenz had cultivated a friendship of many years with his pupil Ida Kupelwieser, and they finally married in 1926, with the photographer Moriz Nähr acting as best man. Unfortunately, Ida died of a stroke after only six months of marriage. In the years that followed, the artist was unable to produce any independent work. Between 1933 and 1947 he wrote his memoirs, which have survived as copies and unpublished transcripts and provide an interesting insight into his private and professional life. Maximilian Lenz died in Vienna on 18 May 1948 at the age of 87 and was buried at Grinzing Cemetery.

Literature and sources

- Österreichisches Biographisches Lexikon. Maximilian Lenz. www.biographien.ac.at/oebl/oebl_L/Lenz_Maximilian_1860_1948.xml (09/11/2020).

- Elisabeth Dutz: The Hagengesellschaft: Bohemia in Vienna, in: PhotoResearcher, Nummer 31 (2019), S. 112-133.

- Trauungsbuch 1926 (Tomus 41), röm.-kath. Pfarre Landstrasse - St. Rochus, Wien, fol. 124.

- Hella Buchner-Kopper: Maximilian Lenz. Ein Maler im Licht / Schatten Gustav Klimts. Betrachtungen zum Leben und Werk eines Angepaßten. Dissertation, University of Klagenfurt 2001.

- Elisabeth Dutz: Moriz Nähr. Die Biografie, in: Uwe Schögl, Sandra Tretter und Peter Weinhäupl für die Klimt-Foundation (Hg.): Moriz Nähr (1859–1945). Fotograf für Habsburg, Klimt und Wittgenstein. Catalogue Raisonné, Wien (2021). www.moriz-naehr.com (05/22/2022).

- Georg Gaugusch: Die Familien Wittgenstein und Salzer und ihr genealogisches Umfeld, in: Heraldisch-Genealogische Gesellschaft ADLER (Hg.): Adler. Zeitschrift für Genealogie und Heraldik, 21. Jg., Heft 4 (2001/02), S. 120-145.

- Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Erster Jahresbericht der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession, Vienna 1899, S. 29.

- Wilhelm Dessauer: Gustav Klimts Winterreise nach Italien. Unveröffentlichte Erinnerungen des Malers Lenz, mitgeteilt von Wilhelm Dessauer, in: Österreichische Kunst, 4. Jg., Heft 3 (1933), S. 11-12.

- Klassenkataloge 1876–1881, .

- Ansichtskarte von Gustav Klimt in Ravenna an Emilie Flöge in Wien (12/02/1903).

- Maximilian Lenz: Meine Erinnerungen. Unveröffentlichtes Typoskript aus den Jahren 1933-1947.. Wortgetreue Abschrift des Originals, Graz 1976.

- Zum Kometenstern. Wien Geschichte Wiki. www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Zum_Kometenstern (02/16/2023).

- Wiener Zeitung (Abendausgabe), 18.07.1886, S. 2.

- Brief von Gustav Klimt an Maximilian Lenz (undated).