Max Klinger

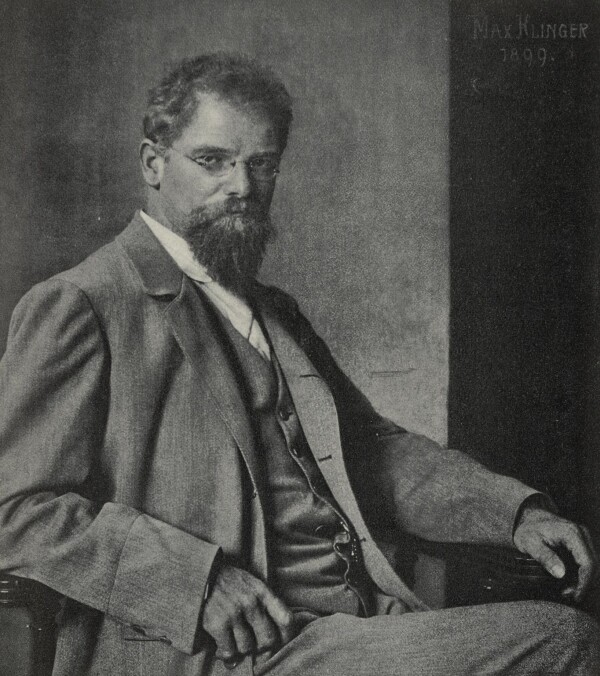

Max Klinger photographed by Nicola Perscheid, 1899, Austrian National Library, Vienna

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

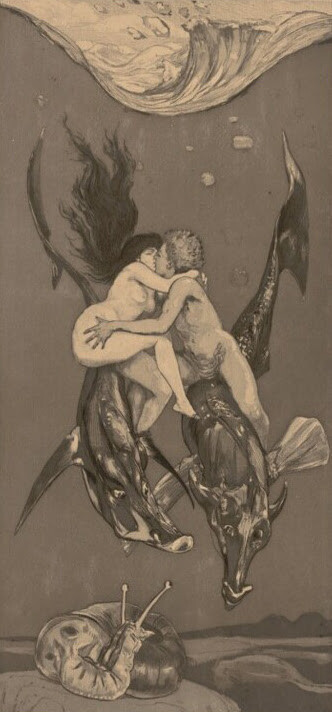

Max Klinger: Seduction, sheet 4 from the cycle "A Life", 1882, The Albertina Museum, Vienna

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

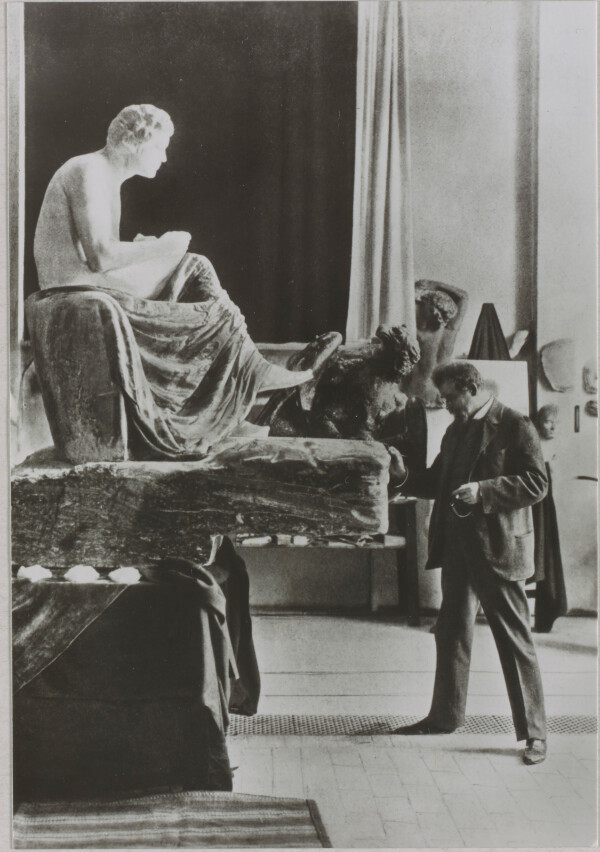

Max Klinger working on the Beethoven statue in his studio, 1988, Leipzig Institute for Regional Geography

© Leipzig-Institut für Länderkunde

Max Klinger was a German painter, graphic artist, medalist, and sculptor. He was a corresponding member of the Vienna Secession and vice president of the Union of German Artists.

Max Klinger was born in Plagwitz near Leipzig on 18 February 1857 the second of five children of master soap boiler Heinrich Louis Klinger. Klinger was active as an artist at a young age and went to Karlsruhe in 1874 to study at the Grand Ducal Baden School of Art. His teachers were the painters Ludwig Des Coudres and Karl Gussow. He then followed Gussow to the Academy of Fine Arts in Berlin, from which he graduated with distinction.

He exhibited for the first time at the “52nd Exhibition of the Royal Academy” in 1878 with the painting Strollers (Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin). In 1879 he executed the graphic cycle Opus I, which anticipated the principal themes of Klinger’s artistic oeuvre per se: death, love and art.

From 1879 on, Klinger lived abroad for several years. During this time, he realized several etching cycles that stylistically referred back to works by Arnold Böcklin and mostly reveal Surrealist and Symbolist traits. These brought him international recognition and awards.

In 1882/83, Klinger made his first sculpture, a portrait bust of Friedrich Schiller. In the summer of 1883, the artist moved to Paris. It was there that he began to increasingly concentrate on the medium of sculpture and also produced the plaster model for his famous Beethoven monument, which he would execute in stone later on. Following his time of artistic activity and studies in Paris, he moved his studio to Rome in 1888. From there, he undertook several trips across Italy, where he was particularly interested in ancient sculpture.

Success and Work in Germany

After Klinger’s Crucifixion had caused a scandal in 1893 due to Christ’s nudity, the artist became a member of the Academy of Fine Arts the following year, and a collective exhibition was organized for him. Both helped Klinger to achieve great renown. In 1895, Klinger designed a studio building for himself in Leipzig, where he collected works by his friends Böcklin, Rodin, and Menzel. Aside from fellow artists, Klinger, who was a music enthusiast, invited important composers and musicians to his studio. The following year he received a major state commission when he was asked to decorate the main hall of Leipzig University.

In 1897 he took part in the “Große Kunstausstellung” [“Great Art Exhibition”] in Leipzig with the monumental painting Christ on Mount Olympus (1897, Belvedere) and a year later in the “Münchener Jahres-Ausstellung” [“Munich Annual Exhibition”] at the Royal Glass Palace. Klimt, who visited the Munich exhibition, was disappointed by the show, but not by his German colleague:

“It [the exhibition] is lousy, apart from a few exceptions, including Klinger’s ‘Christ on Mount Olympus.’”

His appreciation was probably reciprocated. Klinger collected Klimt’s drawings. In a letter to Carl Moll, he also expressly regretted that Klimt had not been appointed professor at the Academy.

In the following years, Klinger concentrated increasingly on his sculptural work. In addition to busts and sculptures of famous musicians like Johannes Brahms, Franz Liszt, Richard Strauss, and Richard Wagner, he also depicted the philosophers Friedrich Nietzsche and Arthur Schopenhauer, whom he admired.

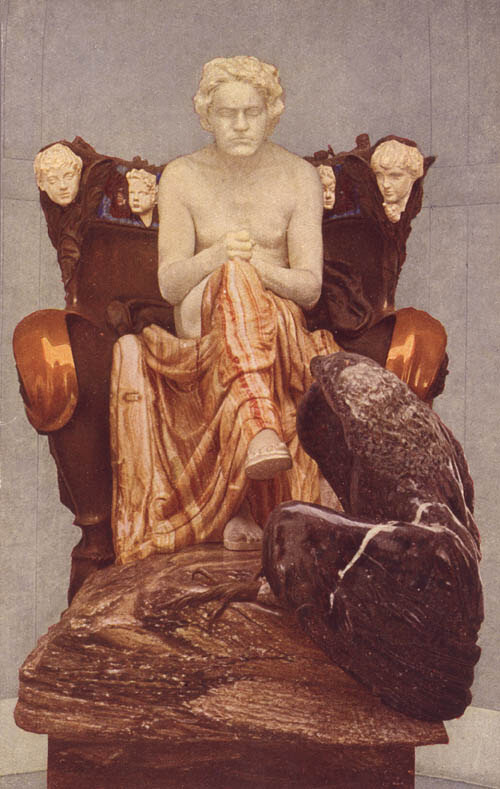

Trying to combine various artistic disciplines, he worked with differently colored materials. He also relied on archaeological findings with respect to the polychromy of ancient sculptures, which he had dealt with during his time in Rome. He achieved polychrome effects using white, black, and purple marble, alabaster, bronze, and ivory.

Klinger and the Vienna Secession

In 1897, Klinger became a corresponding member of the newly founded Vienna Secession, in the exhibitions of which he would participate repeatedly over the next few years. His works had been exhibited in Vienna for the first time in 1895, at the Künstlerhaus.

Moriz Nähr (?): Insight into the XIV Secession Exhibition, April 1902 - June 1902, Albertina, Gustav Klimt Archiv

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

Max Klinger: Beethoven statue, around 1920, Leipzig Institute for Regional Geography

© Leipzig-Institut für Länderkunde

In 1898 he took part in the Vienna Secession’s first exhibition with drawings illustrating the tale of Cupid and Psyche. His Christ on Mount Olympus was shown at the Secession’s 3rd Exhibition. The Secession’s 9th Exhibition focused on the three international artists Giovanni Segantini, Auguste Rodin, and Max Klinger.

In 1902, the Vienna Secession organized an exhibition whose main theme was “Klinger and Beethoven.” The aim was to create a Gesamtkunstwerk or universal work of art on the subject of Beethoven around Klinger’s monumental statue, the Beethoven Monument, which had never been presented before. Gustav Klimt conceived the Beethoven Frieze (1901/02, Belvedere, Vienna) for this 14th Exhibition of the Vienna Secession. On 12 April, the statue was ceremoniously unveiled for the first time, and the second movement of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 was performed under the baton of Gustav Mahler. Klinger came to Vienna in person to attend this important event. To mark the event, Karl Wittgenstein hosted a banquet in Klinger’s honor at Vienna’s Grand Hotel on the evening of 12 April. In addition to the artists of the Secession, their patrons, including Moriz Gallia, Anton Loew, and the Minister of Education Wilhelm von Hartel, were also present.

Despite several efforts, the City of Vienna purchased neither Klinger’s statue nor Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze. Klinger therefore sold the sculpture to his hometown Leipzig. For this purpose, he had the south façade of the Museum of Fine Arts in Leipzig rebuilt at his own expense.

Max Klinger: Bust of Elsa Asenijeff, around 1900

© Bavarian State Painting Collections - Neue Pinakothek, Munich

In 1903, Klinger became vice president of the Union of German Artists under Max Liebermann. Gustav Klimt was also a member. Klinger corresponded with Moll about the possibility of Klimt taking over a studio in a house belonging to the association in Florence. Klimt declined and suggested Max Kurzweil in his place.

Death, Love, and Art

Klinger and the Austrian writer and poet Elsa Asenijeff (real name: Elsa Maria Packeny), who had studied philosophy and psychology at the University of Leipzig, had a relationship of many years without being legally married. Their daughter Desirée was born in 1900, and that same year the artist sculpted a portrait bust of Elsa. The artist also made numerous paintings of his long-time partner, as well as matching bookplates for himself and his muse, until the relationship finally ended in 1916.

At the beginning of November 1919, Max Klinger suffered a stroke followed by pneumonia. Before his death on 4 July 1920, he married his then partner, Gertrud Bock, and left her his entire fortune. Max Klinger died at the age of 63 at his summer residence in Großjena, where he also found his final resting place.

Literature and sources

- belvedere. digital.belvedere.at/people/1068/max-klinger (04/20/2020).

- Deutsche Biographie. Max Klinger. www.deutsche-biographie.de/sfz42897.html (04/20/2020).

- Janca Imwolde: LeMO. Max Klinger. www.dhm.de/lemo/biografie/max-klinger (04/20/2020).

- Secession. www.secession.at/die-beethoven-ausstellung-1902/ (04/20/2020).

- Christian M. Nebehay (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Dokumentation, Vienna 1969, S. 515.

- Mdr. Max Klinger. www.mdr.de/zeitreise/weitere-epochen/neuzeit/max-klinger-leben-100.html (11/25/2021).

- Sächsische Staatszeitung. Staatsanzeiger für den Freistaat Sachsen, 17.02.1917, S. 10.

- Neue Freie Presse, 13.04.1902, S. 7.

- Prager Tagblatt, 13.04.1902, S. 10.

- Brief von Max Klinger an Carl Moll (vor Januar 1905).

- Brief von Max Klinger in Florenz an Carl Moll (01.11.1905).

- Ludwig Hevesi: Max Klinger in Wien, 13. April 1902, in: Acht Jahre Sezession (März 1897–Juni 1905). Kritik – Polemik – Chronik, Vienna 1906, S. 383.

- Berliner Tageblatt und Handels-Zeitung, 21.11.1919, S. 2.

- Dresdner neueste Nachrichten, 12.11.1919, S. 3.

- Berliner Tageblatt und Handels-Zeitung, 06.07.1920, S. 2.

- Leipziger Tageblatt und Handelszeitung. Amtsblatt des Rates und des Polizeiamtes der Stadt Leipzig, 05.07.1920, S. 2.

- Deutsche allgemeine Zeitung (Abendausgabe), 05.07.1920, S. 3.

- Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): XIV. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession. Klinger Beethoven, Ausst.-Kat., Secession (Vienna), 15.04.1902–15.06.1902, Vienna 1902.