Franz Matsch

Franz Matsch photographed by Carl Pietzner, around 1895, Austrian National Library, Vienna

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Franz Matsch sen.: Hermine and Klara Klimt, around 1882

© Belvedere, Vienna

Franz Matsch was one of the leading painters of Vienna’s Ringstraße era. Together with his fellow students Ernst and Gustav Klimt, he founded a studio community, the so-called “Künstler-Compagnie.” Matsch, who regularly executed commissions for the Emperor and Viennese high society, was knighted in 1912 and henceforth entitled to call himself Franz von Matsch. A successful history painter, he also worked as an architect and sculptor.

Franz Matsch was born at No. 23 Josefstädter Straße in Vienna’s 7th District Neubau on 16 September 1861, the son of Karl and Rosina Matsch (née Paweletz). Due to his father’s premature death – Matsch was not even three years old – the family’s financial means were limited.

Matsch, who was artistically gifted from an early age, applied at the School of Arts and Crafts (now University of Applied Arts Vienna) of the Imperial-Royal Museum of Art and Industry (now MAK) in 1875, intending to become a drawing teacher.

During his studies, he met the brothers Gustav and Ernst Klimt. The teachers recognized the talent of the three young men and stood behind them so that they were able to switch to the College of Drawing and Painting in 1878 with the aid of a scholarship. The Klimt brothers and Matsch were also given the opportunity to collaborate on various commissions of their professors. The painter trio worked for Michael Rieser, Ferdinand Julius Laufberger, and subsequently for Julius Victor Berger on designs for stained glass windows for the Votivkirche, the sgraffiti in the inner courtyard of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, and the ceiling paintings for the Empress’s boudoir at the Hermes Villa in Lainz. They were given their own studio at the School of Arts and Crafts. Scholars and literature would later refer to the studio partnership as “Künstler-Compagnie.” In the early 1880s, Matsch also collaborated with his two colleagues on the work Allegorien und Embleme [“Allegories and Emblems”], published by Gerlach & Schenk.

They received their first independent commissions from the architectural office Fellner & Helmer, which had specialized in theater buildings. Between 1882 and 1892, Matsch created numerous ceiling paintings in private palaces in Vienna, as well as decorative paintings and curtains for theater and concert buildings in the provinces, including the municipal theaters of Karlovy Vary and Liberec. In the context of the latter project, Matsch painted an oil painting of the sisters Hermine and Klara Klimt around 1882. In 1883, the painters moved into their first independent studio at No. 8 Sandwirtgasse.

Franz Matsch sen.: The interior of the Altes Burgtheater, 1888 (Heliogravure)

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Franz Matsch senior: Antique Improviser (design), 1886-1887, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Burgtheater and Kunsthistorisches Museum

In the mid-1980s, Franz Matsch, Gustav, and Ernst Klimt were commissioned to decorate the staircase of the Burgtheater, for which they were awarded the Golden Cross of Merit with the Crown in 1888. In 1887, Matsch and Gustav Klimt were also commissioned to artistically document the interior of the old Burgtheater before it would be demolished. Matsch painted the view of the stage, while Gustav Klimt depicted the view of the auditorium in a gouache. Both had received season tickets for the theater for this purpose.

The second important commission for the young trio of artists followed in 1890: the painted decoration of the spandrels in the staircase of the Kunsthistorisches Museum. It can already be seen from these paintings that the three artists, whose hands could hardly be distinguished in previous works, were about to diverge stylistically. While Matsch and Ernst Klimt continued to work in a Historicist style, Gustav Klimt already began to display first signs of a Symbolist idiom.

In 1892, Franz Matsch moved into a studio at No. 21 Josefstädterstraße, which he shared with the Klimt brothers. Living in the neighboring house at No. 23, it had presumably been Matsch who had located the garden pavilion.

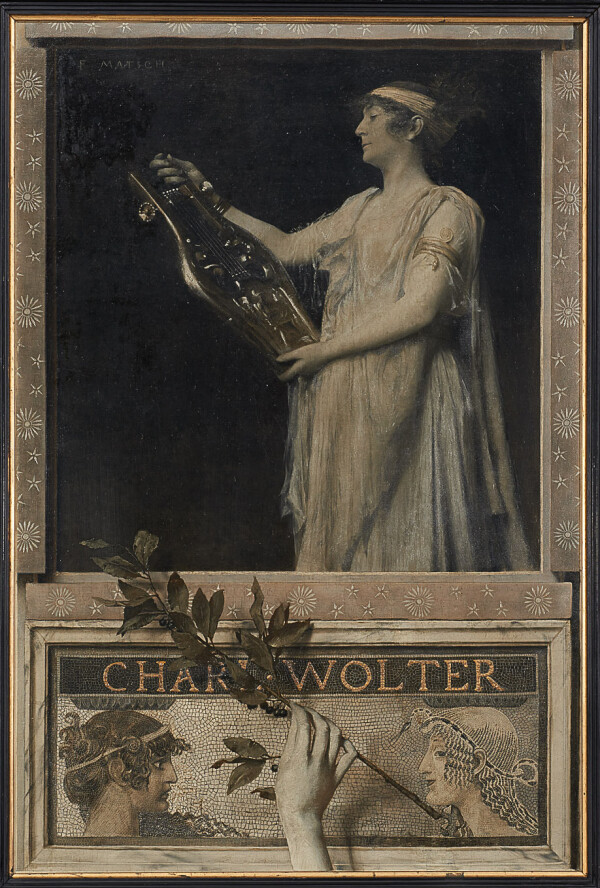

Franz Matsch: Charlotte Wolter as Sappho,1895

© KHM-Museumsverband

Franz Matsch's studio building with the artist's children, Villa Matsch, Hungerberggasse 16, in: Die Kunst für Alle. Malerei, Plastik, Graphik, Architektur, 23. Jg. (1907/08).

© Heidelberg University Library

During their collaboration, the young artists undertook many trips together. Franz Matsch, who was very keen to improve his contacts in high society, often left the others behind on these excursions. In 1889, Gustav Klimt wrote to his father from the Salzkammergut: “Matsch has gone to Weißenbach to see Wolter.” He referred to the actress Charlotte Wolter. Matsch had invited the widow of the Belgian diplomat Count Charles O’Sullivan de Grass, who had died in 1888, to sit for him for his Burgtheater paintings, which led to a long-standing friendship. Matsch produced a wide variety of works, including numerous portraits of the actress, and increasingly used the studio in her villa in Hietzing at No. 33 Alleegasse (now Trauttmansdorffgasse). Wolter paved his way into aristocracy and the imperial court, and these contacts enabled him to obtain numerous independent commissions away from the “Künstler-Compagnie.” Emperor Francis Joseph I became a regular customer. Matsch painted works for the imperial couple, including Triumph of Achilles (1892, Achilleion, Corfu) and Madonna Stella del Mare (1894–1896, private collection) for Empress Elisabeth’s palace in Corfu.

In 1894 it was through his work as a court painter that he met Therese Kattus, the daughter of the Viennese champagne merchant. Her father asked Klimt to paint her portrait, and the artist married her in November 1895. Their daughter Hilde was born in 1897 and their first son, Franz Jr., in 1899.

In 1896, Franz Matsch, who had become a high-earner thanks to his numerous commissions and marriage, had a villa he had designed himself and an adjacent studio built at Hohe Warte in Vienna’s 19th District at No. 16 Hungerberggasse (now No. 3 Haubenbiglstraße). It seems likely for Matsch to have stopped using the shared studio at No. 21 Josefstädter Straße after the completion of his new home and studio in 1898. Villa Matsch, which was destroyed in a bomb attack in 1945, had been holistically designed by the artist in the style of a Gesamtkunstwerk or universal work of art.

Matsch also decorated and furnished the neighboring villa (at No. 60 Silbergasse), which belonged to his father-in-law, Josef Kattus. Matsch, who was generously supplied with work from his circle of wealthy clients, resigned from the Vienna Künstlerhaus in July 1898 and from then on would no longer be affiliated with any artists’ association.

Franz Matsch in his studio building, Villa Matsch, Hungerberggasse 16, in: Die Kunst für Alle. Malerei, Plastik, Graphik, Architektur, 23. Jg. (1907/08).

© Heidelberg University Library

Franz Matsch: Theology

© University of Vienna Archive

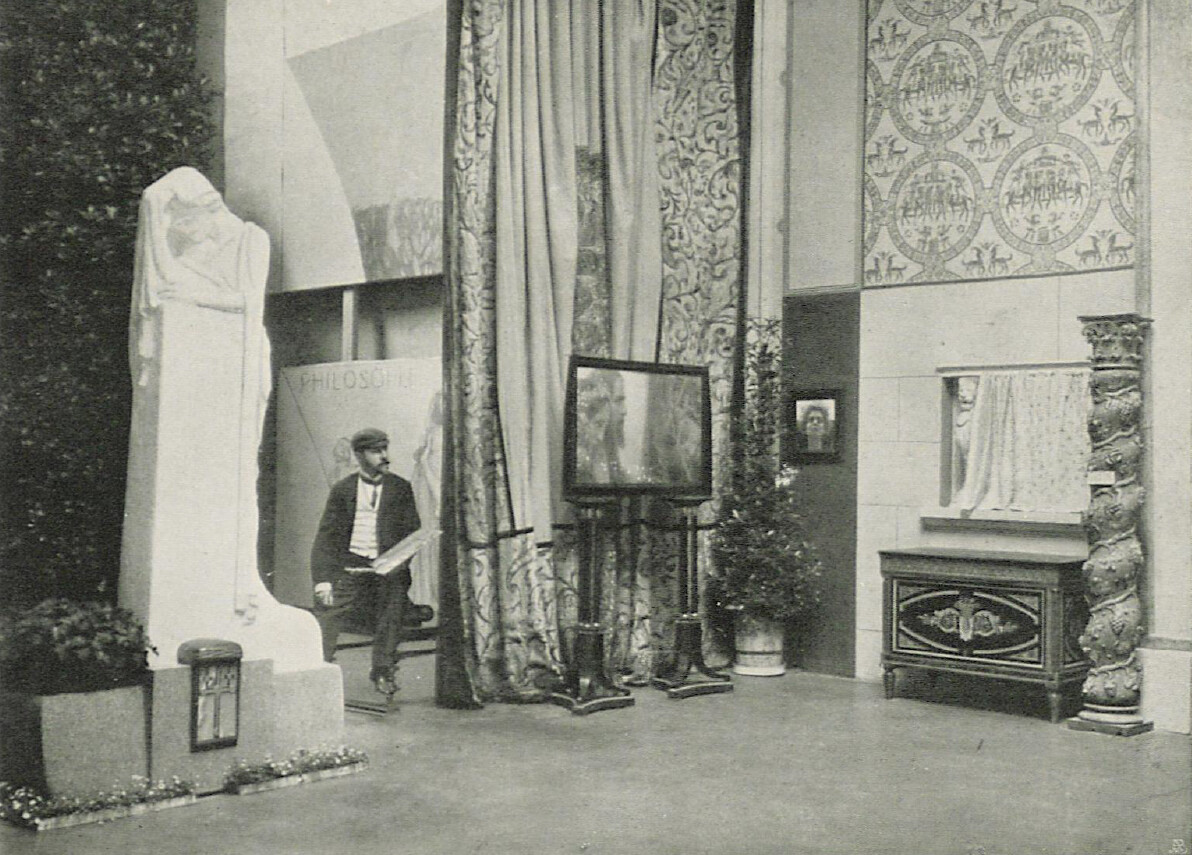

Dissolution of the Studio of the Klimt Brothers and Franz Matsch

In 1893, Franz Matsch was appointed professor at his alma mater, the Imperial-Royal School of Arts and Crafts. That same year, he applied single-handedly for the job to design the ceiling paintings for the Great Hall of the University of Vienna, but was only awarded the contract for a joint project with Gustav Klimt. Matsch was to tackle the large central panel, Triumph of Light over Darkness (1905, University of Vienna), as well as one of the four planned Faculty Paintings, namely Theology (1900–1903, Faculty of Catholic Theology, University of Vienna). Klimt would devote himself to the other three faculties: Medicine, Philosophy, and Jurisprudence. In the course of this project, both artists were criticized for their overly modern designs. The Faculty of Theology, for example, voiced reservations “against the overly modern direction” of Matsch’s designs for the Old and New Testament spandrels. Matsch, who had previously been considered more of a traditional, academic painter, began to explore new artistic paths.

While Klimt had already outgrown Fernand Khnopff and Alma Tadema around 1900, they now became role models for Franz Matsch. The work Father, Forgive Them!, (1903, destroyed in 1945) shows that Matsch’s paintings were just as progressive and mystical as Klimt’s scandalous Faculty Paintings. The crowd of human bodies in the right half of the composition is strongly reminiscent of Klimt’s Medicine (1900–1907, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945) and Philosophy (1900–1907, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945).

Franz Matsch: Lord forgive you, 1903, in: Die Kunst für Alle. Malerei, Plastik, Graphik, Architektur, 23. Jg. (1907/08).

© Heidelberg University Library

It was precisely these disorderly crowds of naked people that had been particularly criticized in Klimt’s paintings. Whether Franz Matsch made this change of style in order to be able to continue collaborating with Klimt on joint commissions, or whether this was a personal artistic development cannot be decided with certainty.

At the same time, both Matsch and Klimt worked on the decorations for the Dumba Palace. Matsch decorated the dining room, while Gustav Klimt worked in the neighboring music room.

Franz Matsch: Dining Room at the Palais Dumba

Franz Matsch sen.: Victory of light over darkness (design), around 1894, The Albertina Museum, Vienna

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

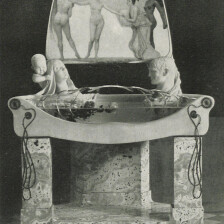

The Fountain of Life (1899, Villa Kattus), which Matsch had designed and executed for the winter garden of the Dumba Palace, was awarded a prize at the 1900 Paris World’s Fair, and Matsch subsequently received the Knight’s Cross of the Order of Francis Joseph.

In 1901, Franz Matsch resigned from his teaching position at the School of Arts and Crafts. According to an article in the Neue Freie Presse, the reason for his resignation was the growing Secessionist influence that made itself felt at the school. In view of the modern tendencies in Matsch’s own work discussed above, however, this seems rather implausible. The artists’ developing in different stylistic directions, which has so often been emphasized in literature, is therefore unlikely to have led to a break. Rather, the choice of patrons and clients of the two former colleagues diverged noticeably. While Matsch mainly frequented the traditional circles of the imperial family and the aristocracy, Klimt mostly found his patrons among entrepreneur friends and scientists.

In 1905, Klimt resigned from the commission of the Faculty Paintings. After this scandal, the collaboration between Franz Matsch and Gustav Klimt was finally over. Although Matsch agreed to take over Klimt’s share, his designs were also rejected, and the four ceiling panels, which were to show the faculties, remained empty. The painting of Theology was finally installed in the meeting room of the Faculty of Catholic Theology. Matsch’s central painting Triumph of Light over Darkness and his spandrel paintings, on the other hand, can still be seen in the Great Hall today.

Franz Matsch: The Anchor Clock, 1812-1814

© SLUB / Deutsche Fotothek

Franz Matsch after the end of the “Künstler-Compagnie”

After the dissolution of the studio partnership with Gustav Klimt, Matsch continued to work successfully on his own. As a consequence of the failure of the Faculty Paintings, Matsch returned to his tried and tested Historicist painting style. This was probably also due to his traditional aristocratic patrons’ stylistic expectations and desires. Between 1908 and 1910 he worked on a commission for the City of Vienna, the painting The Princes of the German Empire Paying Tribute to Emperor Francis Joseph in Schönbrunn on 7 May 1908 (1908–1910, Wien Museum, Vienna). At that time, Emperor Francis Joseph I visited him personally at his studio in Döbling. In 1912 he was ennobled and henceforth entitled to call himself Franz Edler von Matsch. That same year, he received his last major commission. Franz Matsch designed the Anker Clock (1911–1927, Hoher Markt, Vienna) for the branch of the Anker Insurance Company on Hoher Markt. After the outbreak of World War I, he would mainly specialize in landscapes, still lifes, and portraits.

In February 1942, Matsch was again accepted as a full member of the Vienna Künstlerhaus, and in September that year Adolf Hitler honored him with the Goethe Medal for Art and Science. Shortly afterwards, Franz Matsch died in Vienna on 4 October 1942 at the age of 81.

Literature and sources

- Wien Geschichte Wiki. Ankeruhr. www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Ankeruhr (02/02/2022).

- Wien Geschichte Wiki. Trauttmansdorffgasse. www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Trauttmansdorffgasse (02/02/2022).

- Wien Geschichte Wiki. Franz Matsch. www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Franz_Matsch (12/12/2022).

- Herbert Giese: Franz von Matsch – Leben und Werk. 1861–1942. Dissertation, Vienna 1976, S. 1-18.

- Otmar Rychlik: Gustav Klimt Franz Matsch und Ernst Klimt im Kunsthistorischen Museum, Vienna 2012.

- Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien (Hg.): Franz von Matsch. Ein Wiener Maler der Jahrhundertwende, Ausst.-Kat., Museums of the City of Vienna (Vienna), 12.11.1981–31.01.1982, Vienna 1981.

- Ludwig Hevesi: Das Heim eines Wiener Kunstfreundes (Nikolaus Dumba), in: Kunst und Kunsthandwerk. Monatsschrift des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie, 2. Jg., Heft 10 (1899), S. 341-365.

- Das Vaterland. Zeitung für die österreichische Monarchie, 21.12.1888, S. 2.

- Wiener Montags-Post, 22.04.1912, S. 3.

- Wiener Zeitung, 07.05.1901, S. 18.

- Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 24.02.1901, S. 4.

- Reichspost, 13.09.1904, S. 4.

- Neue Freie Presse, 21.09.1901, S. 6.

- Neue Freie Presse, 28.05.1918, S. 9.

- Neuigkeits-Welt-Blatt, 22.06.1893, S. 3.

- Wiener Zeitung, 09.03.1913, S. 7.

- Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 08.04.1900, S. 5.

- Das Vaterland. Zeitung für die österreichische Monarchie, 19.09.1901, S. 11.

- Das Vaterland. Zeitung für die österreichische Monarchie, 29.05.1901, S. 4.

- Günter Meissner, Andreas Beyer, Bénédicte Savoy, Wolf Tegethoff: Allgemeines Künstler-Lexikon. Die bildenden Künstler aller Zeiten und Völker, Band LXXXVIII, Berlin - New York 2016.

- Adolph Lehmann's allgemeiner Wohnungs-Anzeiger. Nebst Handels- u. Gewerbe-Adressbuch für d. k. k. Reichshaupt- u. Residenzstadt Wien u. Umgebung, 33. Jg. (1891), S. 779.

- Adolph Lehmann's allgemeiner Wohnungs-Anzeiger. Nebst Handels- u. Gewerbe-Adressbuch für d. k. k. Reichshaupt- u. Residenzstadt Wien u. Umgebung, 39. Jg., Band 1 (1897), S. 701.

- Adolph Lehmann's allgemeiner Wohnungs-Anzeiger. Nebst Handels- u. Gewerbe-Adressbuch für d. k. k. Reichshaupt- u. Residenzstadt Wien u. Umgebung, 41. Jg., Band 1 (1899), S. 734.

- Adolph Lehmann's allgemeiner Wohnungs-Anzeiger. Nebst Handels- u. Gewerbe-Adressbuch für d. k. k. Reichshaupt- u. Residenzstadt Wien u. Umgebung, 47. Jg., Band 1 (1905), S. 825.

- Adolph Lehmann's allgemeiner Wohnungs-Anzeiger. Nebst Handels- u. Gewerbe-Adressbuch für d. k. k. Reichshaupt- u. Residenzstadt Wien u. Umgebung, 66. Jg., Band 1 (1925), S. 1109.