Carl Moll

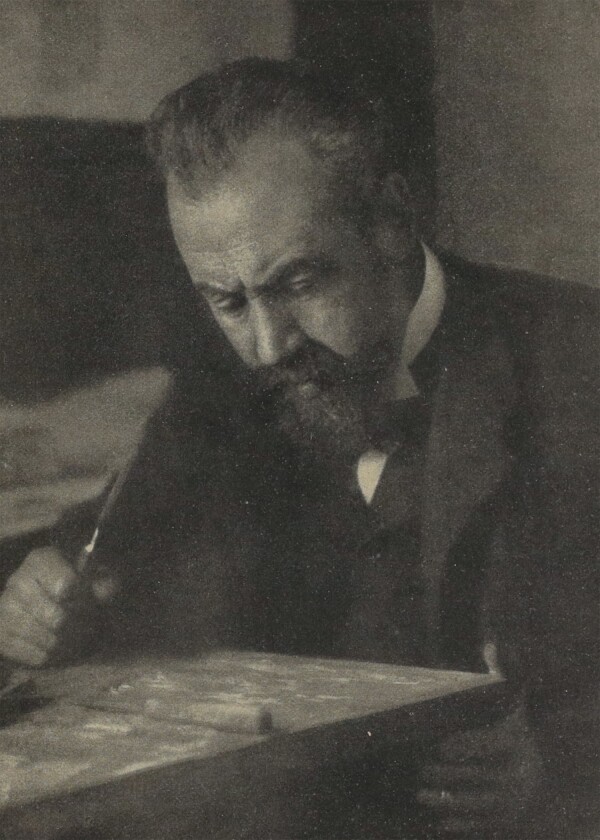

Carl Moll photographed by Friedrich Viktor Spitzer, in: Photographische Rundschau und photographisches Centralblatt. Zeitschrift für Freunde der Photographie, 20. Jg., Heft 23 (1906).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Carl Moll: Anna Moll at a writing desk, around 1903, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

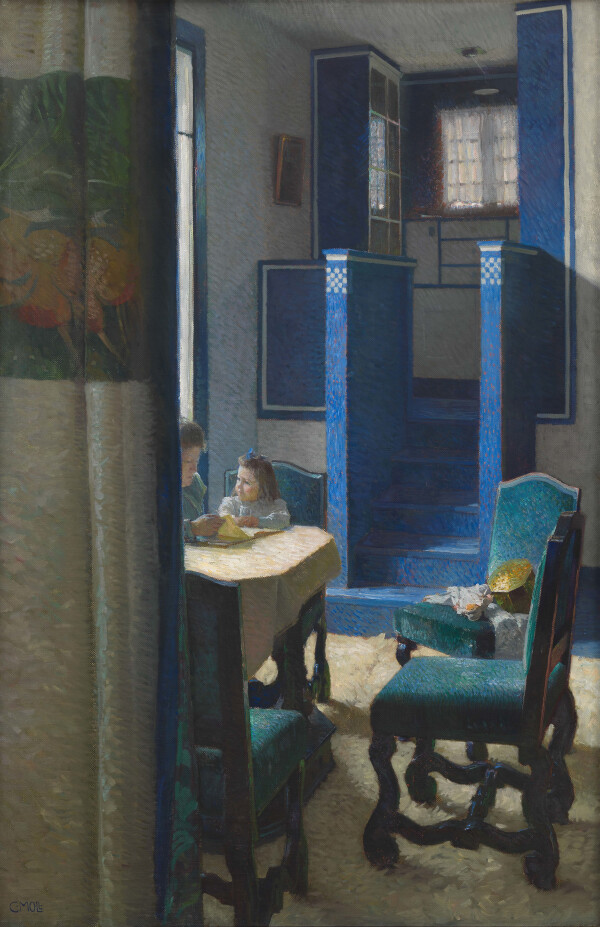

Carl Moll: Salon in Carl Moll's house on the Hohe Warte, 1903, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

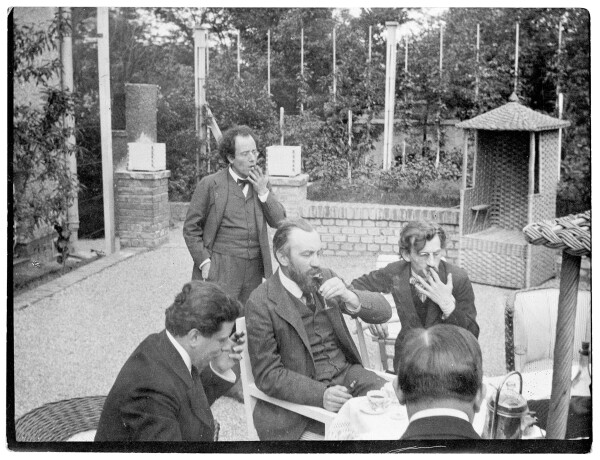

Company in the garden of Villa Moll on the Hohe Warte, May 1905, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

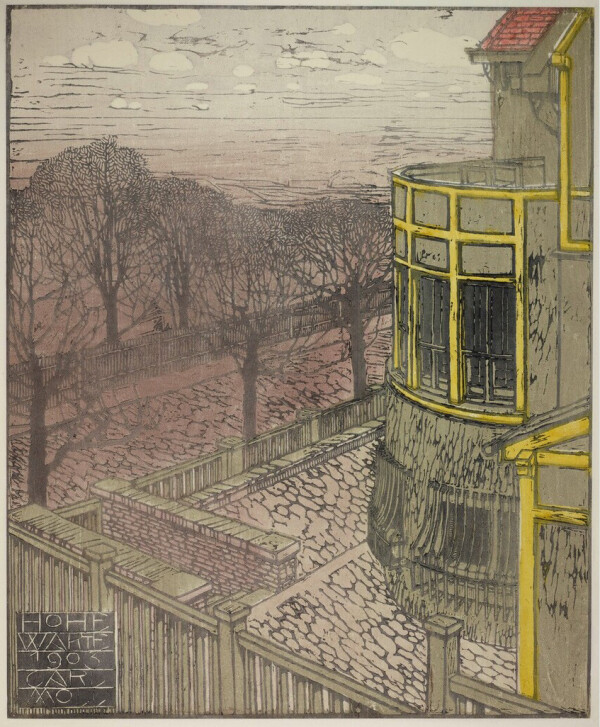

Carl Moll: Color woodcut Hohe Warte, 1903

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

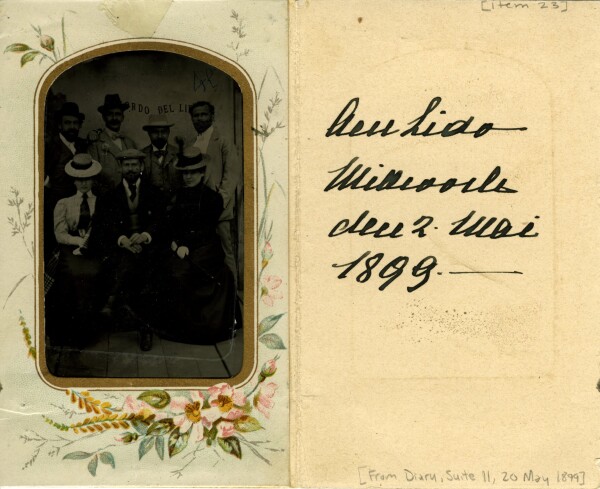

Gustav Klimt with friends at the Lido in Venice, 05/02/1899, University of Pennsylvania

© Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts at the University of Pennsylvania

, undated: Gustav Klimt: Portrait of a Child (Marie Moll), c. 1902-1904

© Wien Museum

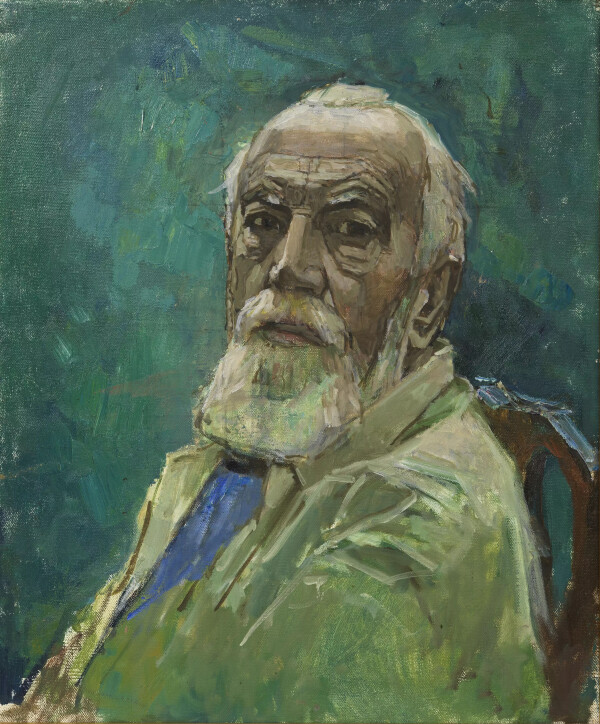

Carl Moll: Self-portrait, 1943, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

The painter and graphic artist Carl Moll was a close friend of Gustav Klimt. Aside from his work as an artist, Moll was also an art dealer and manager of a gallery. He was a co-founder of the Vienna Secession, ran Galerie Miethke, supported the establishment of the Modern Gallery, and advocated modernism in Austria.

Carl Julius Rudolf Moll was born in Vienna on 23 April 1861. His father, Julius Franz Moll, was an employee of the National Bank, an industrialist, and a Vienna councilman. The nephew of landscape painter Karl Schmid, Carl Moll discovered his love for art at an early point in life. Aged seventeen, Moll took private lessons from the landscape painter Carl Haunold. Between 1879 and 1881 he studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. His teacher at the academy, Emil Jakob Schindler, a practitioner of poetic Atmospheric Impressionism, recognized Moll’s talent and encouraged him by instructing him individually. Through him, Moll became acquainted with pleinairism on painting excursions to the Vienna’s surroundings. The young artist was tied to his mentor and the latter’s family by a bond of close friendship. Three years after Schindler’s death in 1892, Moll married his widow, Anna, and thus became the stepfather of Grete Schindler (married name Legler) and Alma Schindler (later known as Alma Mahler-Werfel). Their daughter Maria (married name Eberstaller) was born in 1899.

Künstlerhaus and Early Success

Moll joined the Künstlerhaus in 1890. It was probably there that he met Gustav Klimt, who was only four years his junior and was admitted as a member in 1891. From then on, the two became close friends. Together with Joseph Maria Olbrich, Josef Hoffmann, and Kolo Moser, the two artists were among the association’s progressive forces and supported an opening toward international modern art movements and a reformation of the exhibition system.

Moll celebrated his first successes as an artist starting in the 1890s. The emperor purchased his works The Roman Ruin in Schönbrunn (1892, Belvedere, Vienna) and The Naschmarkt in Vienna (1894, Belvedere, Vienna). Organizing the memorial exhibition for his mentor, Emil Schindler, who had died in 1892, he demonstrated his curatorial skills for the first time. The exhibition of the latter’s estate took place at Galerie H. O. Miethke. In 1894, Moll brought Secessionist art to the Künstlerhaus for the first time, as he invited the artists of the Munich Secession, including Franz Stuck, to show their work in the association’s exhibition venue.

Through various trips abroad around 1893, which also led him to Northern Germany, Moll increasingly came into contact with the works of the French Impressionists. The artist, who had previously been known primarily for his woodcuts, gradually shifted his interest to Impressionist landscape painting.

Carl Moll and Gustav Klimt, Friends and Colleagues

“I feel drawn to you in sincere friendship as it has rarely happened before, and I feel very much at ease in the circle of your family,”

Klimt described his relationship to Moll in 1899.

The circle of friends around Moll, Moser, Hoffmann, Klimt, and Olbrich also met on a regular basis in private. In addition to meetings at Moll’s studio, the aspiring artists also regularly came together at Berta Zuckerkandl’s salon. Important figures from the worlds of art and culture gathered there for an exchange of ideas, including the art patron Fritz Waerndorfer, the musician Gustav Mahler, and the writer Hermann Bahr. The young Künstlerhaus members’ aspirations for reform became stronger and stronger. According to Ludwig Hevesi, the idea of founding the Union of Austrian Artists Secession was born at the Salon Zuckerkandl.

As a result, Moll resigned from the Künstlerhaus in 1897 along with Klimt and other founding members of the Secession. In their new association he initially held the position of vice-president under Klimt, and in 1900 was himself elected president. Moll was instrumental in organizing the Secession’s exhibitions, which became increasingly international. He supplied many of his woodcuts as illustrations for the art magazine Ver Sacrum.

Around 1900, with the help of his friends and patrons Friedrich Viktor Spitzer and Hugo Henneberg, Moll initiated the establishment of an artists’ colony on Hohe Warte, based on plans by Olbrich. The semi-detached house Moll/Moser was built in 1901, followed a year later by the neighboring twin villas for Spitzer and Henneberg. Moll repeatedly revisited the entire estate as a motif for his works. The so-called Villa Moll at No. 6 Steinfeldgasse turned into a meeting place for many artists and writers, as did Carl Moll’s studio at No. 6 Theresianumgasse. Some of the Secession’s conferences were held at Carl Moll’s home. At the beginning of 1909, the family moved into a villa at No. 10 Wollergasse, which was likewise built by Hoffmann and was also known as Villa Moll II.

Moll undertook several private journeys with Gustav Klimt. Postcards addressed to Moll’s stepdaughters document a joint trip to Salzburg in 1898. The following spring, Klimt joined the Moll family on their journey to Florence in Italy. On the return trip, they stopped over in Genoa, Verona, and Venice. During the trip, it almost came to a falling-out between the two friends. A long letter of apology from Klimt reveals that he had begun a love affair with Moll’s eighteen-year-old stepdaughter, Alma, during the journey, thus incurring his friend’s anger. However, the quarrel was settled, and their personal contact remained unharmed. In 1901, Carl Moll sided with Klimt as an enthusiastic defender in the scandal surrounding the Faculty Paintings.

Carl Moll as a Promoter of Modernism

Moll was one of the artists who campaigned for the establishment of the Modern Gallery (now Belvedere) in 1903. It was conceived as a state museum and thus counterpart to the imperial collections and was primarily intended to present works by contemporary artists, including paintings by Gustav Klimt.

In 1905, Carl Moll took over the artistic direction of Galerie H. O. Miethke and turned it into a point of sale for modern art. Following the example of the Berlin Secession and its cooperation with Kunstsalon Paul Cassirer, Galerie Miethke was to serve as an extended exhibition venue and saleroom for the Vienna Secession. Carl Moll’s dual role as an artist and art dealer led to tensions within the association. Many members of the Secession regarded the art dealership’s sales activities as competition to their in-house exhibitions. On 14 June 1905, the Secession held a vote, an episode known as the so-called “Moll Affair,” which culminated in the withdrawal of the group around Moll and Klimt. Galerie Miethke under Moll’s artistic direction therefore became the sole representative for the sale of Klimt’s works. Between 1914 and 1918, Moll himself, who valued Klimt highly both personally and artistically, owned the Klimt painting Water Nymphs (Silverfish) (around 1902/03, Kunstsammlung Bank Austria, Vienna).

The artists in Moll’s circle, who were now without an association and came to be known as the “Klimt Group,” organized two exhibitions in 1908 and 1909. Klimt and Moll worked side by side on the exhibition committee for both the “Kunstschau Wien 1908” and the “Internationale Kunstschau 1909.” In 1909, Moll and Klimt once again traveled together, this time to France and Spain.

Under Moll, Galerie Miethke became Vienna’s market leader in the field of modern art. In numerous exhibitions he brought international works of art, primarily by the French Impressionists, to the imperial capital. However, his management of the gallery was short-lived. On 29 June 1912, Klimt wrote to Emilie Flöge: “Moll is fired,” referring to Carl Moll’s dismissal from Galerie Miethke. Due to a dispute with his colleague, the art historian Dr. Hugo Haberfeld, Moll was forced to leave the gallery. Following his departure, Gustav Klimt’s close collaboration with the art dealership also came to an end.

Klimt’s Death and World War II

After Klimt’s death in 1918, Moll organized two memorial exhibitions for his esteemed friend and colleague. At the Zurich exhibition “Ein Jahrhundert Wiener Malerei [“A Century of Viennese Painting”] in 1918, a separate Klimt Room was set up. In 1928, at Moll’s insistence, the Secession organized the “Gustav Klimt Gedächtnisausstellung” [“Gustav Klimt Commemorative Exhibition”] to mark the tenth anniversary of Klimt’s death. Carl Moll himself was actively involved in organizing the exhibition and made two works from his private collection available for it: the allegory Moving Water (1898, private collection) and an unidentified portrait of a child (presumably Klimt’s drawing of Moll’s daughter Maria).

In 1930, Moll rejoined the Secession, which organized a retrospective exhibition for him the following year to celebrate his seventieth birthday. World War II thwarted Moll’s efforts to make modern art socially acceptable. Many of the artists he supported, including Oskar Kokoschka, were branded as “degenerate.”

Nevertheless, Moll was a supporter of the regime and an anti-Semite. He welcomed the “Anschluss” in 1938, although as a result of it his stepdaughter Alma was forced to emigrate with her Jewish husband, Franz Werfel. He justified his friendship with Alma’s first husband, Gustav Mahler, by saying that only someone “who is a Jew inside is a Jew.” After the end of the war in 1945, he committed suicide together with his daughter Maria and her husband.

Literature and sources

- Robert Weissenberger: Die Wiener Secession, Vienna 1971.

- Wien Geschichte Wiki. Carl Moll. www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Carl_Moll (01/03/2019).

- Österreichisches Biographisches Lexikon. Carl Moll. www.biographien.ac.at/oebl/Moll_Karl (01/02/2019).

- Sandra Tretter, Hans-Peter Wipplinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Jahrhundertkünstler, Ausst.-Kat., Leopold Museum (Vienna), 22.06.2018–04.11.2018, Vienna 2018, S. 8.

- Ansichtskarte von Gustav Klimt in Wien an Emilie Flöge in Bad Gastein, 1. Karte (Morgen) (29.06.1912). RL 2865, .

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Die Galerie Miethke. Eine Kunsthandlung im Zentrum der Moderne, Ausst.-Kat., Jewish Museum Vienna (Vienna), 19.11.2003–08.02.2004, Vienna 2003, S. 62-94.

- Cornelia Cabuk: Carl Moll. Monografie und Werkverzeichnis, in: Stella Rollig (Hg.): Belvedere Werkverzeichnisse, Band 11, Vienna 2020.

- Kunstvermittlung Gerald Weinpolter GmbH. Carl Moll Biografie. www.carl-moll.info/de/biografie (04/20/2022).

- Kunsthaus Zürich (Hg.): Ein Jahrhundert Wiener Malerei. Kunsthaus Zürich, 12. Mai 1918 bis 16. Juni 1918: Verzeichnis der ausgestellten Werke, Ausst.-Kat., Kunsthaus Zurich (Zurich), 12.05.1918–16.06.1918, Zurich 1918.

- Arbeitsausschuss der Kunstschau (Hg.): Katalog der Internationalen Kunstschau 1909, Ausst.-Kat., Exhibition building Lothringerstraße (Vienna), 22.04.1909–01.07.1909, 1. Auflage, Vienna 1909.

- Vereinigung bildender KünstlerInnen Wiener Secession (Hg.): XCIX. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Wiener Secession. Klimt-Gedächtnis-Ausstellung, Ausst.-Kat., Secession (Vienna), 27.06.1928–05.08.1928, Vienna 1928.

- Prager Tagblatt, 05.10.1912, S. 5.

- Neue Freie Presse, 30.11.1928, S. 1.

- Andreas Beyer, Bénédicte Savoy, Wolf Tegethoff (Hg.): Allgemeines Künstler-Lexikon. Die bildenden Künstler aller Zeiten und Völker, Band XC, New York - Berlin 2016, S. 236.