The Bloch-Bauer Family

Adele Bloch-Bauer, photographed by Friedrich Viktor Spitzer, 1906, in: Photographische Rundschau und photographisches Centralblatt. Zeitschrift für Freunde der Photographie, 22. Jg., Heft 3 (1908).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, 1907, Neue Galerie New York, Acquired through the generosity of Ronald S. Lauder, the Heirs of the Estates of Ferdinand and Adele Bloch-Bauer, and the Estée Lauder Fund

© APA-PictureDesk

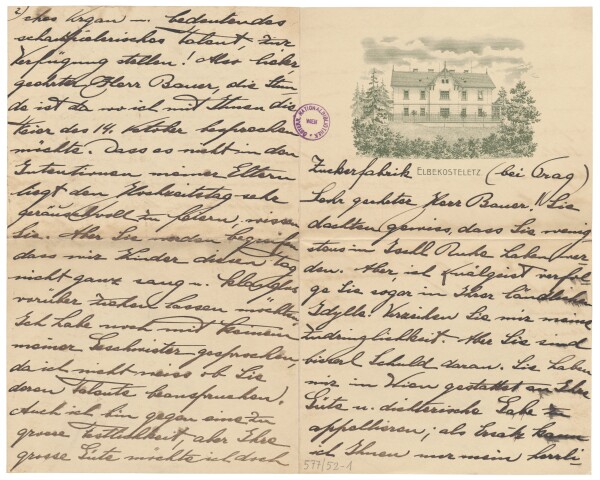

Adele Bloch-Bauer: Letter from Adele Bloch-Bauer in Elbekosteletz to Julius Bauer, 08/22/1903, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Sammlung von Handschriften und alten Drucken, Partial Estate of Julius Bauer

© Department of Manuscripts and Rare Books, Austrian National Library

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II, 1912, private collection

© APA-PictureDesk

The wealthy Bloch-Bauer family was among Gustav Klimt’s most important benefactors. With the commissioned work Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, the Jugendstil artist created one of the icons of his Golden Period. It has become symbolic of the countless instances of stolen art during National Socialism and often protracted restitution cases.

The Bloch and Bauer Families

Ferdinand Bloch, who hailed from a Prague dynasty of sugar magnates, was born on 16 July 1864 in Jungbunzlau (now Mladá Boleslav). He managed one of the largest sugar factories in Central Europe. Along with his socio-political commitment and his activities as an art collector, he was a supporting member of an association for the promotion of Austrian museums, the Österreichische Staatsgalerieverein, later Verein der Museumsfreunde. Adele Bauer, the daughter of the general manager of the Viennese association of banks, Moriz Bauer, was born on 9 August 1881 in Vienna. In December 1899, Ferdinand Bloch, who was 35, married the 18-year-old Adele Bauer, who was also known for her socio-political commitment. The connection between the two Jewish families was further strengthened by the marriage between Adele’s sister Theresia and Ferdinand’s brother Gustav. Both couples used the double name Bloch-Bauer from February 1917. Ferdinand and Adele had no children.

The couple used their social standing to establish a salon, where Vienna’s intellectual and artistic elite came together. Along with political figures from social democracy, whom Adele supported financially, the salon’s welcome guests included Gustav Mahler, Arthur Schnitzler, Stefan Zweig and Richard Strauss. Owing to these connections, the couple also made contact with Gustav Klimt.

Gustav Klimt and His “Fairytale-Like Combinations for the Eye”

As early as 1903, the genius painter received the commission for the painting Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907, Neue Galerie New York), which was initially intended as a wedding present for Adele’s parents. In a letter dated 22 August 1903, she wrote about this to her friend, the journalist Julius Bauer:

“[…] Originally, us children wanted to give a joint present, but we have since discarded this idea. My husband then decided to have Klimt portray me […].”

From the winter of that year, Klimt elaborated the work in 100 meticulous detail studies to create this “idol in a scintillating temple shrine” – as Berta Zuckerkandl aptly described it – with its references to the mosaics of Ravenna and Venice Klimt had seen that year. He did not finish the work until 1907.

“Frau Bloch says that I am looking well” Gustav Klimt and the Bloch-Bauers

Klimt regularly met the art patrons, for instance at dinner parties or during visits to concerts and exhibitions. In 1910, the painter and Adele, accompanied by other artists including Alfred Roller, Kolo and Editha Moser and Carl Otto Czeschka, attended the second performance of Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 3. This concert visit took place in the context of a Munich exhibition.

In 1912, Klimt portrayed Adele a second time in the painting Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II (1912, private collection). This second portrait, which looks very different to the first, captivates with its Fauvist, floral colorfulness and Asian ornaments. That year, Klimt visited the Bloch-Bauer family, as he had done in September 1911, at their estate in Jungfernbreschan (now Panenské Břežany) near Prague. On 15 November 1912, Klimt wrote a picture postcard to Emilie Flöge on his way there. Usually, several guests participated in these social encounters. Special activities included what was known as a “chicken hunt,” which Klimt described to Emilie in their correspondence.

The Bloch-Bauer Family’s Collection

The family’s collection included not only the two portraits of Adele but also Klimt’s works Birch Forest (Beech Forest) (1903, private collection), Kammer Castle on the Attersee III (1910, Belvedere, Vienna), Apple Tree I (Small Apple Tree) (c. 1912, private collection), Houses in Unterach on the Attersee (1915/16, private collection), as well as likely from 1928 to 1939 the Portrait of Amalie Zuckerkandl (1917/18 (unfinished), Belvedere, Vienna). Additionally, the Bloch-Bauer family also owned several drawings by Klimt, as the Galerie H. O. Miethke’s filing card no. 355 documents. Keen art collectors in general, their collection included works by Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller and Emil Jakob Schindler, as well as porcelain and silver objects.

The Years after Klimt’s Death

World War I prompted the Bloch-Bauers to move to their castle in Jungfernbreschan, and to become Czechoslovakian citizens. While the estate had become their primary residence, they kept an apartment at Schwindgasse 10 (Vienna-Wieden, 4th District). In 1919, Ferdinand bought a mansion at Elisabethstraße 18 (Vienna-Innere Stadt, 1st District). That year, the portraits of Adele and the four landscapes by Klimt from their collection were loaned to the Österreichische Staatsgalerie (now Belvedere, Vienna) to be shown in exhibitions. In early 1920, the works returned to the Bloch-Bauers’ residence, resuming their place in what was known as the “Klimt Room.”

Up until her death, Adele expedited her role as a sophisticated salonnière on the one hand, and a supporter of the socialist workers’ movement on the other. She died on 24 January 1925, and was laid to rest at the urn cemetery in Vienna-Simmering, 11th District. In her will, she decreed that Klimt’s paintings should be given to the Österreichische Staatsgalerie after her husband’s death.

Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer continued his commitment to art after his wife’s passing. He extended the collection, and loaned works to various exhibitions, such as the “Klimt-Gedächtnisausstellung” [Klimt Commemorative Exhibition] held at the Vienna Secession in 1928.

Nascent National Socialism and the outbreak of World War II forced him to flee to Prague, followed by his emigration to Switzerland. His assets were confiscated. In 1939, the collection was dispossessed and dissolved. Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer died on 13 November 1945 in Zurich. His ashes were also buried at Simmering Crematorium. In his last will, he provided for his estate to go to his nieces, Louise Baroness Gutmann and Maria Altmann, and to his nephew Robert Bentley. The dispossession of the exquisite Bloch-Bauer collection and the disregard of Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer’s will led to a protracted legal battle which – aside from a handful of previous restitutions – resulted in 2006 in the long overdue restitution of the Klimt paintings to Maria Altmann.

Literature and sources

- Berta Zuckerkandl: Die Kunstschau 1908, in: Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, 06.06.1908, S. 4.

- Ludwig Hevesi: Altkunst – Neukunst, Vienna 1909, S. 207.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Die Welt von Klimt, Schiele und Kokoschka. Sammler und Mäzene, Cologne 2003, S. 87-99.

- Sophie Lillie: The Golden Age of Klimt. The Artist’s Great Patrons: Lederer, Zuckerkandl and Bloch-Bauer, in: Renée Price (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. The Ronald S. Lauder and Serge Sabarsky Collections, Ausst.-Kat., New Gallery New York (New York), 18.10.2007–30.06.2008, Munich 2007, S. 54-89.

- Georg Gaugusch: Wer einmal war. Das jüdische Großbürgertum Wiens 1800–1938, Band 1, Vienna 2011, S. 104-107.

- Hubertus Czernin: Die Fälschung. Der Fall Bloch Bauer und das Werk Gustav Klimts. Band 2, Vienna 1999.

- Tobias G. Natter, Gerbert Frodl (Hg.): Klimt und die Frauen, Ausst.-Kat., Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 20.09.2000–07.01.2001, Cologne 2000.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Klimt and the Women of Vienna's Golden Age. 1900–1918, Ausst.-Kat., New Gallery New York (New York), 22.09.2016–16.01.2017, London - New York 2016.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Jane Kallir, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Klimt, Schiele, Kokoschka und die Frauen, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna), 22.10.2015–28.02.2016, Munich 2015.

- Leonhard Weidinger: Lexikon der Provenienzforschung. Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer. www.lexikon-provenienzforschung.org/bloch-bauer-ferdinand (09/02/2022).

- Lisa Silverman: Gustav Klimt, Adele Bloch-Bauer I. www.bpb.de/themen/zeit-kulturgeschichte/geteilte-geschichte/340148/gustav-klimt-adele-bloch-bauer-i/ (09/02/2022).

- Ansichtskarte von Gustav Klimt in Wodolka an Emilie Flöge am Semmering (15.11.1912). RL 2868, .

- Ansichtskarte von Gustav Klimt in Wien an Emilie Flöge am Semmering, 1. Karte (Morgen) (28.02.1912). RL 2854, .

- Ansichtskarte von Gustav Klimt in Wodolka an Emilie Flöge in Wien (27.09.1911). RL 2845, .

- Brief mit Kuvert von Gustav Klimt in Wien an Emilie Flöge in Wien (presumably late September 1911). Autogr. 959/54-2, .

- Eintrittskarte zur »Ausstellung München 1910« unterschrieben von Gustav Klimt, Alma Mahler, Kolo Moser, Editha Moser, Adele Bloch-Bauer, Alfred Roller, Max Reinhardt, Anna Moll, Josef Maria Auchentaller und Carl Otto Czeschka (13.09.1910). MKG Archiv, NL Czeschka, Bestand Angelika Spielmann Karton 13 A, Mappe 5_2.

- Karteikarte Nr. 355 der Galerie H. O. Miethke über den Verkauf von 16 Skizzen (07/17/1906).

- Brief von Adele Bloch-Bauer in Elbekosteletz an Julius Bauer (22.08.1903). Autogr. 577/52-1, .