Carl Reininghaus

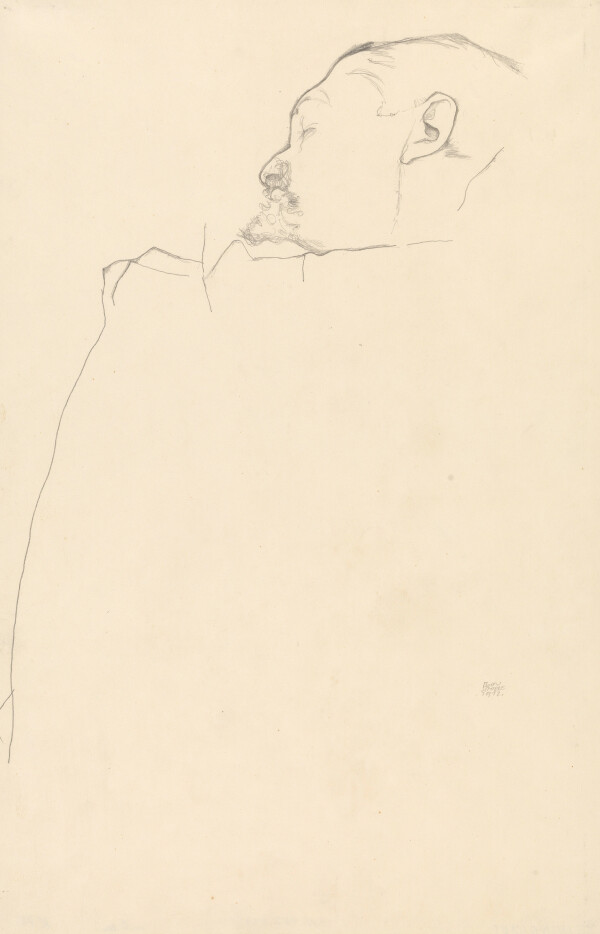

Egon Schiele: Carl Reininghaus, 1912

© Wien Museum

Carl Reininghaus was a patron of the arts who promoted Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, Ferdinand Hodler and other artists of the Secession. Following the 14th Exhibition of the Secession, dedicated to Beethoven, he acquired Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze, thus saving it from destruction.

Carl Reininghaus hailed from a Graz dynasty of Beer brewers. He was the eldest son of Julius Reininghaus and Emilie, née Mautner Markhof, and was born on 11 February 1857 in Graz. After his father’s untimely death, Carl Reininghaus inherited a considerable fortune which enabled him to live a life of financial independence. Reininghaus invested his capital in a comprehensive art collection, and is considered an important commissioner and patron of his time. Around 1900, he owned one of the most eminent compilations of artworks in Styria. The emphasis of his collection was on works by Hans Makart, Hans Thoma and Wilhelm von Kaulbach, as well as on older Italian art.

Following his divorce from his first wife Zoë, née von Karajan, with whom he had five children, Reininghaus moved to Vienna in 1904. Prior to his move, and perhaps on account of his kinship with the Mautner Markhof family, who acted as benefactors to the Secessionists, he had already established ties with several young artists of the Secession, including Gustav Klimt, Carl Moll and Egon Schiele. Reininghaus changed the focus of his art collection to modern art, and actively supported the artists of the Secession. In 1899, for example, he financed Klimt and Moll’s trip to Italy.

Carl Moll noted about the Graz industrialist’s passion for the art of the Secession:

“When a Secession exhibition was due to open, he could never contain his excitement; already during the hanging of works he besieged the premises, turned over every painting, disturbed the workers, was feared and – loved.”

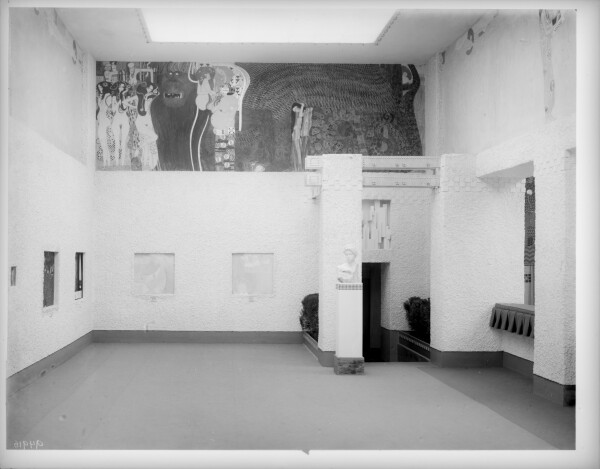

Moriz Nähr: Insight into the XIV Secession Exhibition, April 1902 - June 1902, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Gustav Klimt: The Beethoven Frieze (The Hostile Forces), 1901/02, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: The Beethoven Frieze (The Arts, Paradise Choir and Embrace), 1901/02, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

The Beethoven Frieze and the Hohe Warte

Around 1900, serval artists connected with the Secession made plans to establish an artists’ colony on Hohe Warte. To this end, the artists Moll, Moser, Henneberg and Spitzer bought plots of land there. Carl Reininghaus was the only nonartist to also purchase a piece of land on Hohe Warte. His intention was to have a villa designed by Josef Hoffmann in keeping with the idea of a Gesamtkunstwerk [universal work of art]. For unknown reasons, Villa Reininghaus was never built, however, and the plot was later given to Carl Moll and the Ast family.

Around this time, Reininghaus made what was possibly one of his largest acquisitions at a Secession exhibition. Klimt had created The Beethoven Frieze in 1901/02 for the Secession’s Beethoven Exhibition. The monumental frieze was originally only intended as an interior decoration and was meant to be knocked off the walls after the end of the exhibition. But then Carl Reininghaus announced his intention to buy the work. Several newspapers reported that Reininghaus was willing to pay the princely sum of 40,000 crowns (approx. 291,000 euros) for it. However, in a letter to Maria Zimmermann, dated 17 October 1902, Klimt wrote that the actual purchase price was only half of that sum. Moreover, Klimt mentioned that Reininghaus had bought the frieze for an as yet unexecuted residential building:

“[...] regarding the ‘sensation’ [NB: The acquisition of The Beethoven Frieze] – I am sure you have read the ‘special edition’ – none of it is true – everything has remained the same – not 40,000 but 20,000, and this only provided the images can be taken down and attached somewhere else. [...] the house where they are supposed to go has not been built yet – it hasn’t even been started – plenty of time for the man to regret his purchase”

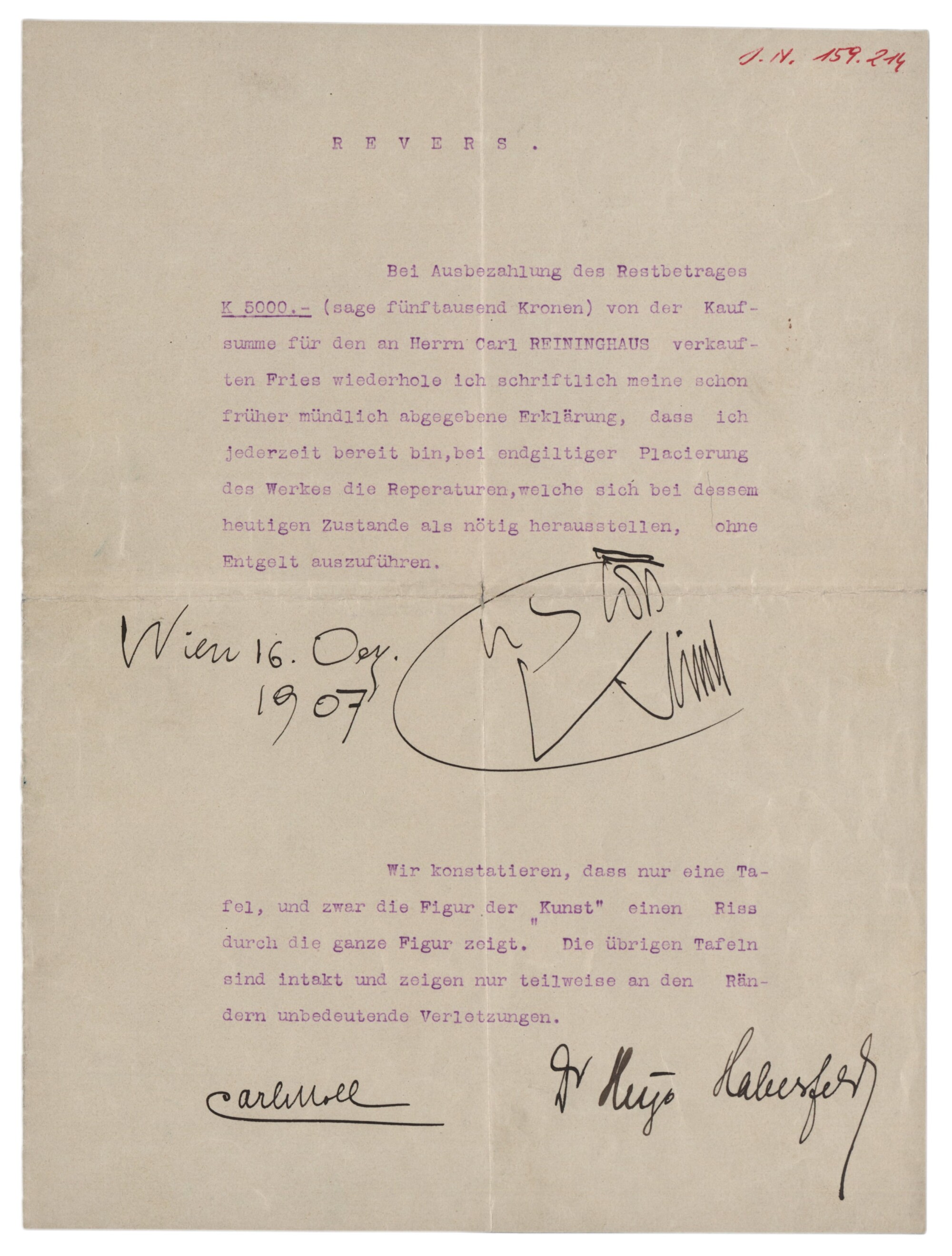

The house in question might have been the villa for which Reininghaus had bought the plot on Hohe Warte, but which was never built. The sale happened nonetheless. Despite difficulties that occurred when dismantling the frieze, an agreement made in 1907 documents that Reininghaus purchased the plates. In the agreement, Klimt confirmed that he would repair any damage done whilst taking the frieze off the wall or during transport free of charge upon payment of the remaining sum. The sale was likely handled by Galerie Miethke, as the agreement was further signed by the gallery’s director Carl Moll and his assistant Hugo Haberfeld.

Reininghaus kept the unused frieze until 1915. While it could be viewed by private appointment, it was not shown in public during this time. Eduard Buschbeck, for instance, was able to view the frieze in 1912 by agency of the director of the Österreichische Galerie, Friedrich Dörnhöffer. In 1915, Reininghaus sold the monumental work to the Klimt collectors August and Serena Lederer.

Gustav Klimt: Reverse by Gustav Klimt in Vienna, co-signed by Carl Moll and Hugo Haberfeld, 12/16/1907, Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Handschriftensammlung

© Vienna City Library, Manuscript collection

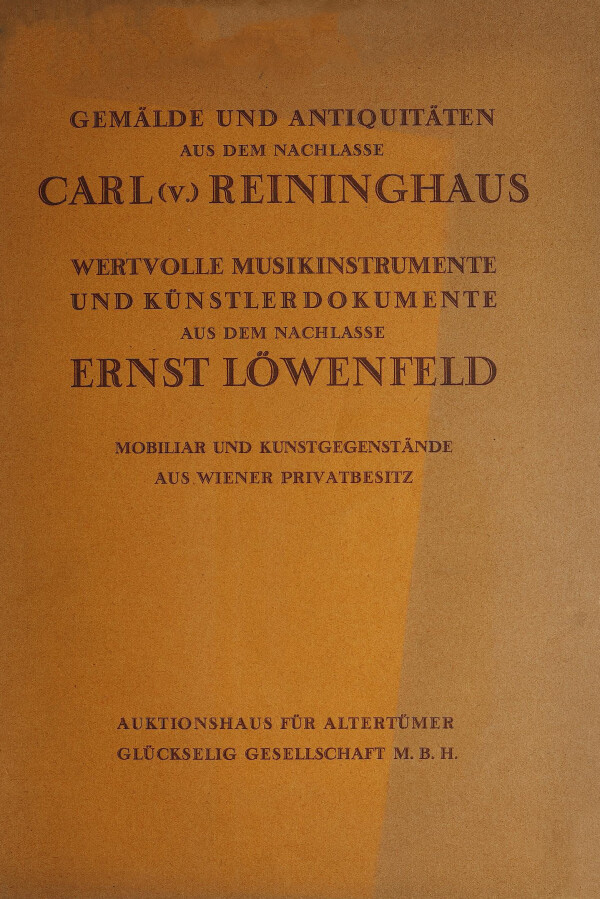

Auktionshaus für Altertümer Glückselig Gesellschaft M.B.H. (Hg.): Gemälde und Antiquitäten aus dem Nachlasse Carl (v.) Reininghaus. Wertvolle Musikinstrumente und Künstlerdokumente aus dem Nachlasse Ernst Löwenfeld. Mobiliar und Kunstgegenstände aus Wiener Privatbesitz, Aukt.-Kat., Vienna 1933.

© Heidelberg University Library

Patron of Modernism

Along with Klimt, Reininghaus also supported other up-and-coming artists. After exhibitions at the Secession, he acquired several works by Ferdinand Hodler, including the main work of the 19th exhibition, held in 1904, Weary of Life (1892, Neue Pinakothek München). Reininghaus also had close ties with Egon Schiele. We know that he repeatedly visited the young artist at his studio. When Schiele was accused of having seduced a minor, Reininghaus provided his friend with financial support for his trial. Schiele also created several portraits of his collector and benefactor. In 1905, Reininghaus had his apartment at Brahmsplatz 4, in which he resided until 1921, decorated by Adolf Loos. The interior has not survived.

Reininghaus was also active as an international collector, and took a keen interest especially in French art. His collection included works by Eduard Manet, Auguste Renoir and Paul Cézanne. Time and again, he loaned works from his compilation to exhibitions – as well as to Galerie Miethke run by Carl Moll – so that they could be presented to the public.

An admirer of modern art, he further organized competitive exhibitions to enable young artists to present their works. For a 1913 competition, he endowed the first prize for a painting with a prize money of 3,000 crowns (approx. 20,300 euros). The jury was made up of Gustav Klimt, Rudolf Junk, Josef Hoffmann and Carl Reininghaus himself.

In 1920, Reininghaus married Friederike Knepper. The couple had no children. After his death on 29 October 1929, parts of his collection were sold for financial reasons, despite his wish to keep it as an ensemble. The principle heirs were Reininghaus’ illegitimate children, who he had officially adopted before his death, while his five children from his first marriage only received a compulsory portion of his estate. Paying out these legal shares was only possible by selling individual works from the collection.

Literature and sources

- Lexikon der österreichischen Provenienzforschung. www.lexikon-provenienzforschung.org/reininghaus-carl (05/04/2020).

- Kunstrückgabebeirat. www.secession.at/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Empfehlung-des-Kunstr%c3%bcckgabebeirat.pdf (05/04/2020).

- Reininghaus.at. www.reininghaus.at/website/carl_r.htm (05/04/2020).

- Wien Geschichte Wiki. Brahmsplatz. www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Brahmsplatz (05/04/2020).

- Christina Gschiel: „Transport der Teile ohne zu schneiden“. Die Bergung des Beethoven-Frieses aus der Sammlung Lederer in Schloss Thürnthal, in: Pia Schölnberger, Sabine Loitfellner (Hg.): Bergung von Kulturgut im Nationalsozialismus, Mythen – Hintergründe – Auswirkungen, Vienna - Cologne - Weimar 2016, S. 359-382, S. 360.

- Carl Moll: Carl Reininghaus. Ein Gedenkwort von Carl Moll, in: Neue Freie Presse, 17.11.1929, S. 37-38.

- Tobias G. Natter: Die Wiener haben mir nun aus dem Dreck herausgeholfen!. Ferdinand Hodler, sein Sammler Carl Reininghaus und die Folgen, in: Tobias G. Natter, Niklaus Manuel Güdel, Monika Mayer, Elisabeth Schmuttermeier, Rainald Franz (Hg.): Hodler, Klimt und die Wiener Werkstätte, Ausst.-Kat., Kunsthaus Zurich (Zurich), 21.05.2021–29.08.2021, Zurich 2021, S. 12-31.

- Revers von Gustav Klimt in Wien, mitunterschrieben von Carl Moll und Hugo Haberfeld (12/16/1907). H.I.N. 15.9214, .

- Brief mit Kuvert von Gustav Klimt in Wien an Maria Zimmermann in Villach (10/17/1902). S63/28.

- Brief von Carl Reininghaus in Wien an Friedrich Dornhöffer (02/17/1913). 1913-290/2, .

- N. N.: Der Erbstreit im Hause Reininghaus beigelegt. Aufteilung der Kunstschätze, in: Die Stunde, 12.11.1931, S. 3.

- Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, 30.03.1906, S. 2.

- Neue Freie Presse, 31.05.1913, S. 13.