Café Museum

Café Museum exterior view, 1899

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

Advertising for the Café Museum, in: Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): XX. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Oesterreichs Secession Wien. März April Mai 1904, Ausst.-Kat., Secession (Vienna), 26.03.1904–12.06.1904, Vienna 1904.

© Library of the Belvedere, Vienna

View into the billiard room of the Café Museum by Adolf Loos, around 1911

© Wien Museum

Wilhelm Gause: Café Museum, Gibson Room, 1899

© Wien Museum

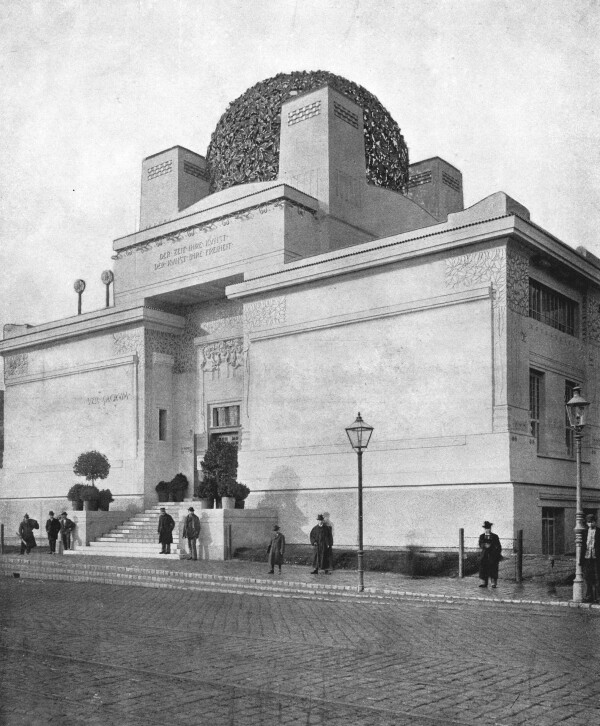

Vienna Association, around 1898, in: Wiener Bauindustrie-Zeitung und Wiener Bauten-Album, 17. Jg., Band 1 (1899/1900).

© ANNO | Austrian National Library

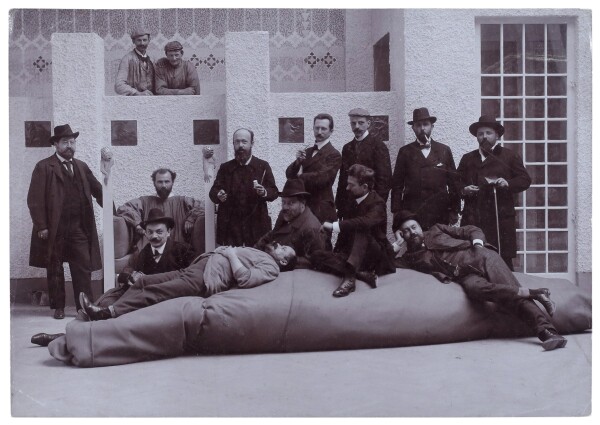

Moriz Nähr: Gustav Klimt with the artists participating in the 14th Exhibition of the Secession, April 1902, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Café Museum interior view, view through the left wing after the redesign by Josef Zotti, photographed by Bruno Reiffenstein, 1931

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Accommodated in one of the oldest buildings in the Ringstraße zone, the Café Museum, innovatively designed by Adolf Loos, was frequented by the Viennese art and cultural scene. Known as the Secessionists’ hangout, it was also a favorite haunt of Gustav Klimt.

The Beginnings

Originally run by Ludwig Frisch, the café named “Zum Museum” was situated opposite the Kunsthistorisches Museum (at Babenbergerstraße 5 in Vienna’s 1st Innere Stadt District). Since 1899, the Café Museum – a variation of the name that was kept – can be found at the corner of Operngasse 7 and Friedrichstraße 6 (in the 1st District), in the immediate vicinity of the Vienna Secession Building. Max Fabiani, a student of Otto Wagner and the future architect of the Urania, was entrusted with the interior decoration at first, but he passed the commission on to Adolf Loos.

Loosian Restraint

The interior design of the Café Museum was the quintessence of Loos’s principle to distance oneself from both Historicism and the Vienna Secession’s contemporary embellishments. Loos devised an overall concept for the Café Museum that focused on materiality and was committed to practicability at the same time. Inspiration for the café came from the Viennese coffeehouses on the Ringstraße furnished in the Biedermeier style. Loos appreciated the period’s formal vocabulary, as well as that of the English Chippendale style. Moreover, he also incorporated impressions gained during his stay in the United States of several years. It was the combination of all this that consolidated his position as an antagonist of Josef Hoffmann and the latter’s architecture in particular and of the Secession in general, even if the humorous weekly paper Kikeriki stated sarcastically:

“The modern Secessionist direction, which has otherwise few agreeable things to offer, has been considered here in a most fortunate way, as the result recognizes the Viennese taste; everyone will feel cozy and at home here.”

One of Vienna’s sights is the newly opened Café Museum

In the coffeehouse, which consists of two spacious vaulted enfilades, a rounded cashier’s booth made of dark mahogany was located opposite the entrance. The same wood was used for the billiard tables installed in the room to the left of the cash desk. Rows of seats were put up along the walls and windows. Loos sought to conceal the different lengths of the two enfilades by installing a mirrored wooden screen presenting a series of pictures of hunting scenes and horse races: the ambience thus resembled a modern gentlemen’s club that reflected Loos’s preference for Anglo-Saxon culture. The adjacent room, which was called “Gibson Room,” stood out for its series of pictures by the American illustrator Charles Dana Gibson of women and men in contemporary sportswear practicing modern sports. The seating came from the Prag Rudniker basketwork factory.

The room to the right of the cash desk was furnished with traditional coffeehouse suites. For the chairs, Loos optimized ordinary serial models manufactured by the bentwood furniture company Jacob & Josef Kohn. The beechwood used for the furniture was stained in a particular reddish tone. In combination with the walls, which were covered with matt green velour wallpaper distinguished by its blotting paper grain, this ensured an appearance rich in contrasts. Brass strips were used to frame most of the walls. Similar frames made of the same metal were used to protect the legs of the billiard and marble coffee tables. Loos also created an innovative electrical lighting system for the Café Museum: made of brass, it also functioned as hat racks.

The Café Museum and the Vienna Secession

Although the interior of this café had been designed by a critic of the Vienna Secession, it would become an important meeting place of its members and other artists soon after the café’s opening, probably also because it was so close to the Secession building. Among its regulars were Peter Altenberg, Albert Paris Gütersloh, Oskar Kokoschka, Karl Kraus, Egon Schiele, and Franz Werfel. Carl Moll and his stepdaughter Alma Schindler were welcome guests, as were Marie and Hugo Henneberg and Friedrich Viktor Spitzer. A special table was always reserved for Josef Hoffmann, Kolo Moser, Joseph Maria Olbrich, Alfred Roller, Otto Wagner, and Gustav Klimt, as the German painter Walter Klemm, a participant in the “Kunstschau Wien 1908,” remembered. According to Klemm, the café was also frequented by Amiet, Hodler, Munch, and further guests of the Secession coming from abroad. From the correspondence between Fritz Waerndorfer and Hermann Bahr we know that it was there that they discussed the book project Gegen Klimt [“Against Klimt”] in 1903, with which they sought to condemn the criticism of the Faculty Paintings as being behind the times. Loos himself was also a regular, assembling at his table students from the Polytechnic University and the Academy of Fine Arts, both of which were near.

The art critic Ludwig Hevesi, who was also a supporter of the Vienna Secession, pointed out in May 1899: “In his ‘Café Museum,’ Loos presents himself as a sincere Non-Secessionist. [H]e did a good job. Somewhat nihilistic, very nihilistic indeed, but appetizing, logical, practical. And unusual, which is also deserving.” Moreover, Hevesi declared that Loos “did not pose as an enemy of the Secession, but as something different, for ultimately both are modern.” From then on, the establishment was also referred to as “Café Nihilism.”

Redesigns of the Café Museum

In 1931 the original interior decoration was replaced by that of Josef Zotti, a student of Josef Hoffmann and senior designer of the Prag Rudniker basketwork factory. The plain style propagated by Loos had to give way to circular settees in red synthetic leather, and the bentwood chairs were swapped for new seats. About twenty years earlier, a basketwork balustrade had been commissioned to fence in the café’s sidewalk seats.

Zotti’s interior design was to be kept for a long time, until the place underwent general refurbishment at the beginning of the 2000s. Loos’s puristic spatial concept was reconstructed, which, however, entailed harsh criticism. Since 2010 the café’s furnishings have therefore once again been based on Zotti’s design.

Literature and sources

- Ludwig Hevesi: Aus dem Wiener Kunstleben, in: Mittheilungen des k. k. Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie. Monatsschrift für Kunst und Gewerbe, 2. Jg., Heft 5 (1899), S. 196-197.

- Ludwig Hevesi: Kunst auf der Straße. 30. Mai 1899, in: Acht Jahre Sezession (März 1897–Juni 1905). Kritik – Polemik – Chronik, Vienna 1906, S. 170-175.

- Wien Geschichte Wiki. Cafe Museum. www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Caf%C3%A9_Museum (04/15/2020).

- Eva B. Ottillinger: Möbelgeschichten, ein Katalog, in: Eva B. Ottillinger (Hg.): Wagner, Hoffmann, Loos und das Möbeldesign der Wiener Moderne. Künstler, Auftraggeber, Produzenten, Ausst.-Kat., Imperial Furniture Collection - Vienna Furniture Museum (Vienna), 21.03.2018–07.10.2018, Vienna - Cologne - Weimar 2018, S. 76-78.

- Michaela Schlögel: Klimt mit allen fünf Sinnen, Vienna 2012, S. 88.

- Elana Shapira: Style & Seduction. Jewish Patrons, Architecture and Design in Fin de Siècle Vienna, Waltham 2016.

- Anthony Beaumont, Susanne Rode-Breymann (Hg.): Alma Mahler-Werfel. Tagebuch-Suiten. 1898–1902, 2. Auflage, Frankfurt am Main 2011, S. 604.

- Kikeriki. Humoristisches Volksblatt, 23.04.1899, S. 5.