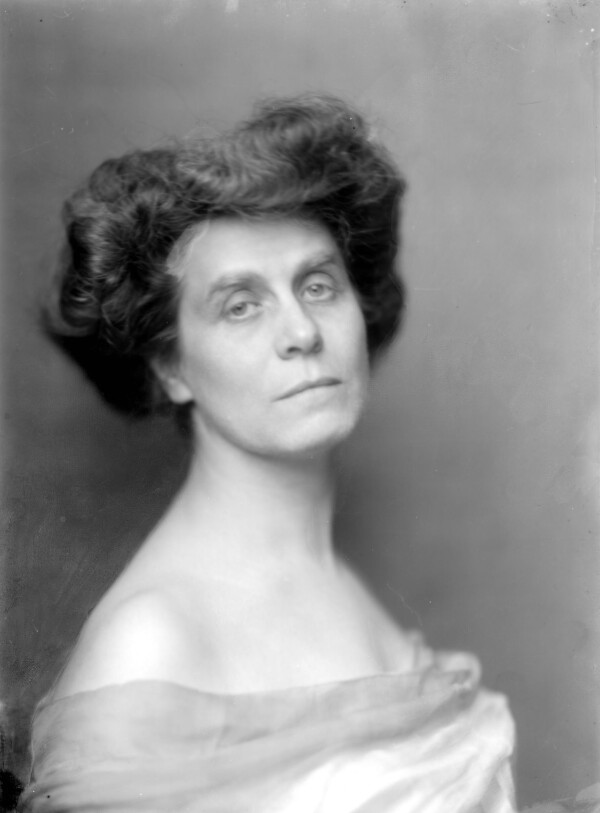

Berta Zuckerkandl

Berta Zuckerkandl photographed by Madame d'Ora, 1908

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

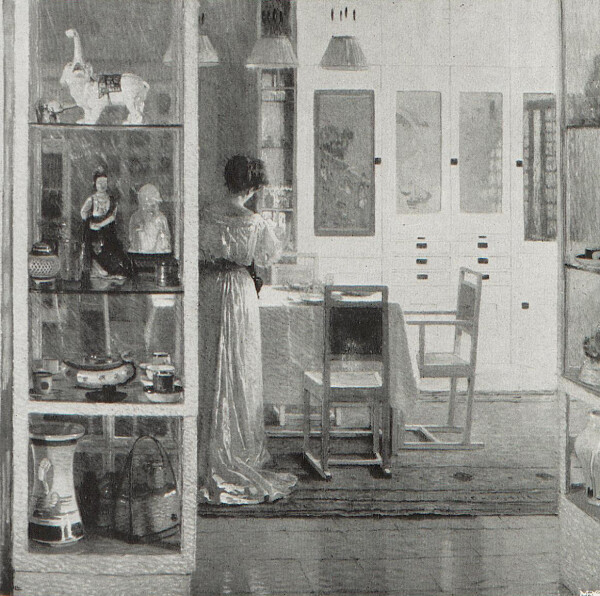

Carl Moll: White Interior, 1905, view of the dining room at Villa Zuckerkandl in Nußwaldgasse, in: Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, Band 23 (1908/09).

© Heidelberg University Library

Anton Kolig: Portrait of Berta Zuckerkandl, 1925

© Wien Museum

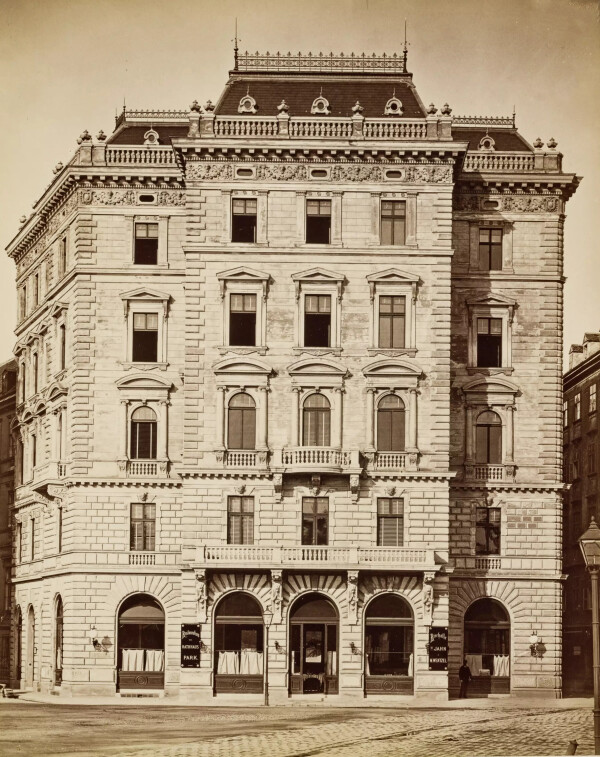

Berta Zuckerkandl's apartment and salon in Palais Lieben, Oppolzergasse, around 1900

© Wien Museum

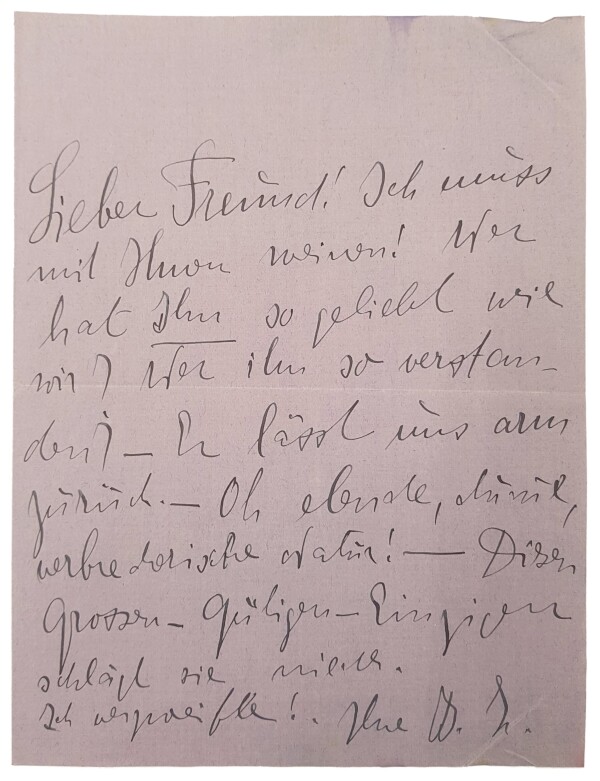

Berta Zuckerkandl: Letter from Berta Zuckerkandl to Anton Hanak, presumably after 02/06/1918, LANGENZERSDORF MUSEUM, Hanak-Archiv

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

As a writer, literary figure, and journalist, Berta Zuckerkandl championed modern art for over half a century. Her salon was a meeting place for numerous artists, writers, and scholars. Her circle of friends included many Secessionists, including Gustav Klimt.

Berta Zuckerkandl was born into a Jewish family on 13 April 1864. She was the daughter of Moriz Szeps, the editor of the newspaper Neues Wiener Tagblatt, and his wife Amalie, née Schlesinger. She and her sister Sophie received a comprehensive education. Numerous writers, musicians, and actors frequented the home of the Szeps family. From an early age, she accompanied her father as a secretary to French and English politicians. Since her father was a friend of Crown Prince Rudolf, it was easy for the two daughters to gain a foothold in high society. In 1886, Berta married the physician Emil Zuckerkandl, who would later teach anatomy at the University of Vienna. They had met in 1883 through the writer Berthold Frischauer. Emil was very much interested in art as well and an important collector. Her husband’s entire family started collecting works by Klimt, presumably also with the help of art-loving Berta.

Through the marriage of her sister Sophie to Paul Clemenceau, the brother of the future French Prime Minister, Paris became Berta’s second home, where she encountered Rodin and Impressionism, among other things.

Berta Zuckerkandl, the Secession, and Gustav Klimt

As a columnist, Berta Zuckerkandl campaigned tirelessly for the Secession, the Wiener Werkstätte, and, above all, Gustav Klimt. Her critical articles about art and culture appeared in the Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, the Neues Wiener Journal, Ver Sacrum, and the magazines Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration and Die Kunst für Alle.

Following her parents’ example, starting in 1888 she ran a salon on Günthergasse in Vienna’s 9th District, a meeting place of the artistic elite and future patrons of the arts. Klimt, Mahler, Moser, and Moll were among the guests, as were Hermann Bahr, Arthur Schnitzler, Egon Friedell, and the families Hellmann, Löw, Berl, and Waerndorfer. A few years after the birth of son Fritz in 1895, the family and the salon moved to Alserbachstraße. According to Ludwig Hevesi, the idea of founding the Secession was born in one of her two salons. The illustrious circle later moved to Nußwaldgasse in Vienna’s 19th District, where Berta and her husband had bought a villa near the Hohe Warte artists’ colony. The art-loving couple had their residence decorated by Josef Hoffmann and the Wiener Werkstätte. Thanks to Carl Moll, a regular guest at their house, the interiors of their home and the couple’s collection of Asian art were documented in the form of paintings twice.

Berta Zuckerkandl was also committed to helping Klimt to private commissions from her guests, all of whom were to become important collectors of the artist.

Since the foundation of the Secession in 1898 and the Wiener Werkstätte in 1903, Berta Zuckerkandl had published numerous essays in which she advocated modern art and encouraged its dissemination. Through her sister in Paris she introduced Auguste Rodin and Eugène Carrière to the Secession as associate members. Berta even brought the former to Vienna in 1902 in the context of an exhibition of his works. She and her husband also vehemently defended Gustav Klimt in the dispute over the Faculty Paintings. Emil Zuckerkandl was one of twelve university professors to sign a petition in Klimt’s favor, calling for Klimt’s paintings to be installed in the assembly hall. Berta saw Klimt as a “figurehead of a revolutionary art movement,” a “leader, pioneer, and genius recognized by everyone.” She dedicated her book Zeitkunst, which appeared in 1908, to the artist, who was also her close friend: “To Gustav Klimt, the first and greatest artist, this small token of goodwill. Presented faithfully by B. Z.”

After her husband’s death in 1910 and her mother’s death in 1912, she worked as a translator and journalist. In this context she also collaborated closely with Arthur Schnitzler, with whom she shared a bond of friendship throughout her life.

Following a serious illness during which she stayed at the sanatorium of her friends, the Löw family, the widow moved to Oppolzergasse near the Burgtheater in 1916, where she continued to host a salon. A sitting area designed by Josef Hoffmann, which had been moved from Nußwaldgasse, stands for the long tradition of this meeting place for art and culture:

“This cozy divan corner is a principal part of my social life. For many years I have met here with my friends.”

The death of Gustav Klimt in 1918 hit Berta Zuckerkandl hard. In a letter to Anton Hanak, she expressed her pain over the loss:

“I cannot but weep with you! Who loved him as much as we did? Understood him as we did? – He has left us behind deprived. – Oh, miserable, stupid, mischievous nature! – This great, kindhearted, unique man it knocked down. Joining you in despair, Yours, B. Z.”

In the years that followed, she would write tirelessly about Klimt in order to preserve his art and accomplishments for posterity. She was one of the few who would continue publishing about the painter even years after his death. She was also part of the exhibition committee for the “Gedächtnisausstellung Gustav Klimt” [“Exhibition in Commemoration of Gustav Klimt”] at the Secession in 1928.

In 1920, she supported Max Reinhardt and Hugo Hofmannsthal as a journalist in their efforts to rescue Austrian culture in the form of the Salzburg Festival.

After World War I, the pacifist journalist also became involved outside of the cultural scene as a mouthpiece for international activities and campaigned for peace and international understanding. She wrote about Austrian foreign policy for the Neues Wiener Journal.

After Austria’s “Anschluss” to the German Reich in 1938 she was forced to flee to her sister in Paris with her grandson Emile due to her Jewish ancestry. From there she traveled on to Algiers, where she remained active as a journalist during the war years, but became increasingly impoverished. Seriously ill, she returned to Paris in 1945, where she died on 16 October.

Literature and sources

- Reinhard Federmann (Hg.): Berta Zuckerkandl: Österreich intim, Erinnerungen 1892- 1942, Vienna 2013.

- De Gruyter. Bibliothek Forschung und Praxis. Band 42: Heft 1. Berta Zuckerkandl – Netzwerkerin der Wiener Moderne: Über die Sammlungen Emile Zuckerkandl an der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek. www.degruyter.com/view/journals/bfup/42/1/article-p128.xml (04/06/2020).

- Der Standard. Nationalbibliothek erwirbt Zuckerkandl-Archiv (26.11.2012). www.derstandard.at/story/1353207349685/nationalbibliothek-erwirbt-zuckerkandl-archiv (04/06/2020).

- FemBio. Frauen. Biografieforschung. Berta Zuckerkandl. www.fembio.org/biographie.php/frau/biographie/berta-zuckerkandl/ (04/06/2020).

- Ö1. Das Porträt der Amalie Zuckerkandl. oe1.orf.at/artikel/641943/Das-Portraet-der-Amalie-Zuckerkandl (04/06/2020).

- Wien Geschichte Wiki. Berta Zuckerkandl. www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Berta_Zuckerkandl (04/06/2020).

- Berta Zuckerkandl-Szeps: Erinnerung an Gustav Klimt, in: Die Bühne. Wochenschrift für Theater, Film, Mode, Kunst, Gesellschaft, Sport, 11. Jg., Heft 386 (1934), S. 3-7.

- Christian M. Nebehay (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Dokumentation, Vienna 1969.

- Berta Zuckerkandl (Hg.): Zeitkunst. Wien 1901–1907, Vienna 1908, S. 163-166.

- Franz Eder, Ruth Pleyer: Berta Zuckerkandls Salon – Adressen und Gäste, Versuch einer Verortung, in: Bernhard Fetz (Hg.): Berg, Wittgenstein, Zuckerkandl. Zentralfiguren der Wiener Moderne, Vienna 2018, S. 212-233.