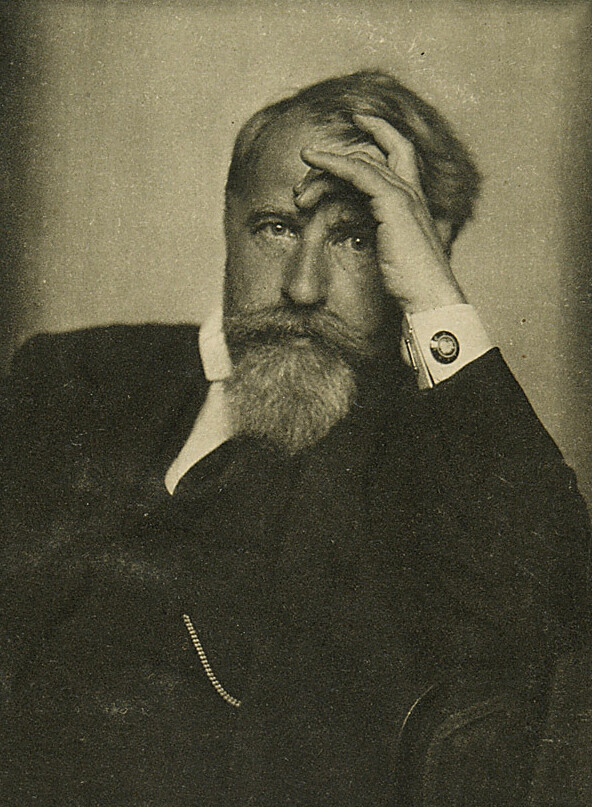

Arthur Schnitzler

Arthur Schnitzler photographed by Madame d'Ora, 1915, Theatermuseum, Vienna

© KHM-Museumsverband

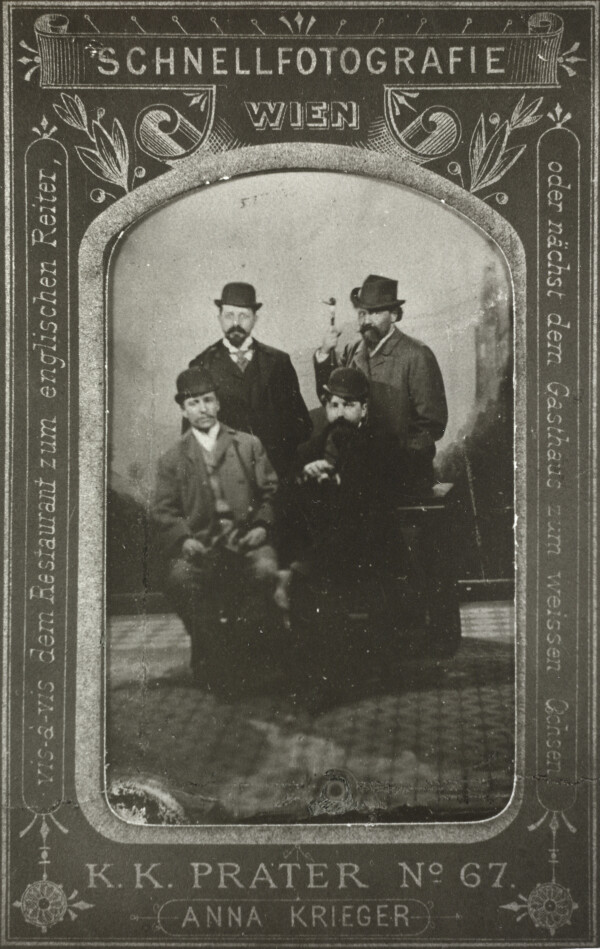

The "Young Vienna" group: standing Richard Beer-Hofmann and Hermann Bahr, seated Hugo von Hoffmannsthal and Arthur Schnitzler photographed by Anna Krieger, around 1895, Austrian National Library, Vienna

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

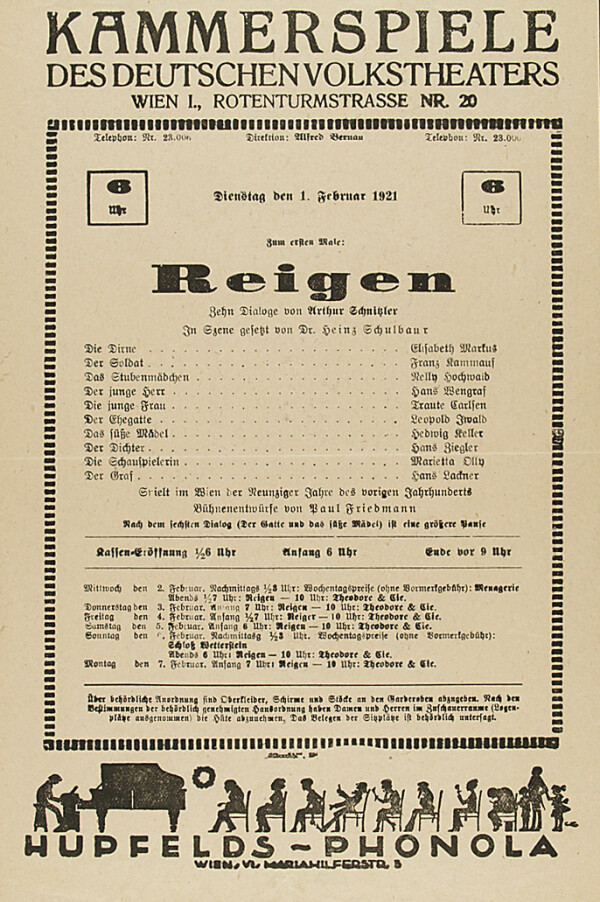

Premiere ticket of Arthur Schnitzler's "Reigen" at the Kammerspiele of the Deutsches Volkstheater, Vienna, 01.02.1921, Theatermuseum, Vienna

© KHM-Museumsverband

Arthur Schnitzler was among the most important writers of the fin-de-siècle. In his literary oeuvre, he addressed the societal and political injustices of his time, such as emerging anti-Semitism and the social upheaval following the demise of the Habsburg Empire. He had friendly ties with Gustav Klimt, whom he greatly admired.

Arthur Schnitzler was born in Vienna on 15 May to the laryngologist Johann Schnitzler and the doctor’s daughter Luise, née Markbreiter, into an assimilated Jewish family. Like his father and grandfather before him, he studied medicine in Vienna, and subsequently worked as a physician at Vienna’s General Hospital. Early on, Schnitzler had shown an inclination towards art and literature but was not given the chance to actively pursue these interests.

A Writing Doctor

Around 1890, Schnitzler encountered members of the literary circle Jung-Wien [Young Vienna], promoted by Hermann Bahr, at Café Griensteidl. His friends included Richard Beer-Hofmann as well as Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Felix Salten. These contacts encouraged Schnitzler to become increasingly active as a writer. Having already worked as an editor for his father’s medical journal Internationale Klinische Rundschau, he published the one-act play cycle Anatol in 1892, as well as some poetry and prose. Owing to his work as a physician, psychoanalysis played an important role in his literary creations. The work The Interpretation of Dreams (1900) written by Sigmund Freud – whom Schnitzler had known personally since 1885 – proved particularly inspirational to the author.

After his father’s death in 1893 and the opening of a private practice, Schnitzler was finally able to resolve the long-standing conflict between his medical and literary activities.

Schnitzler celebrated his breakthrough in 1895 when the publishing house S. Fischer became publishers of his works, and the play Liebelei premiered at Vienna’s Burgtheater. As Schnitzler’s works held up a brutally honest mirror to Viennese society, they caused a lot of controversy. His monologue novella Leutnant Gustl, published in the 1900 Christmas supplement of the newspaper Neue Freie Presse, in which he leveled unveiled criticism at the Imperial-Royal military, led to the revocation of his officer’s rank. His cycle Reigen, published in 1897, fell victim to censorship. When the play eventually premiered in 1920 in Berlin and in 1921 in Vienna, the performances were disrupted by anti-Semitic provocations. In Berlin, Schnitzler was even taken to court for offending moral rights. This prompted the author himself to prohibit the play from being performed – a ban that wasn’t lifted until 1982. Despite all this harsh criticism and ill will, Schnitzler received the award Bauernfeldpreis in 1899, and established himself as Austria’s most famous playwright. With the emergence of political anti-Semitism, however, he faced increasing hostilities. In his novel Der Weg ins Freie [The Road into the Open] (1907), he addressed the precarious situation of Vienna’s assimilated Jews. His play Professor Bernhardi (1912), about plots against a Jewish hospital director, was banned from being performed in Austria.

Following the divorce from his wife, the actress Olga Gussmann, after 18 years of marriage in 1921, the suicide of his 18-year-old daughter Lilli, the Reigen scandal and the gradual loss of his hearing, Schnitzler became increasingly lonely, while translations of his works into numerous languages won him international renown as a writer. Schnitzler died on 21 October 1931, and was laid to rest at the old Israelite section of Vienna’s Central Cemetery. He was thus spared from witnessing the ban of his works by the National Socialist regime in 1933.

Schnitzler’s Relationship with Klimt

Arthur Schnitzler was an ardent admirer of Klimt’s. In many of his diary entries, he stressed his love for the artist, and even wrote about encountering him in his dreams:

“In my dreams, I love him [NB: Gustav Klimt] very much (even more than in reality).”

The two personalities had met through a shared circle of acquaintances. The Zuckerkandl family, especially, provided a point of intersection. Schnitzler had become friends with Otto Zuckerkandl when they were both medical students. Through this connection, Schnitzler met Otto’s sister-in-law Berta Zuckerkandl, who was close friends with Klimt. Thus, the two men kept meeting each other at various social gatherings, at Berta Zuckerkandl’s salon, at Moll’s house or within the circle of the Mahler family. Schnitzler described Klimt as the “jolly faun” at dinner parties.

Schnitzler’s interest in Klimt extended not just to his personality but also to his art. Again and again, he wrote about Klimt’s work in his diary. In 1911, he saw The Stoclet Frieze (1905–1911, private collection) at Leopold Forstner’s mosaic workshop. In March 1907, he encountered the painting Hope I (1903/04, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa) when he and Klimt were invited to the home of Fritz Waerndorfer. Schnitzler’s wife Olga, née Gussmann, often gave him Klimt drawings as presents. When Schnitzler received one such drawing as a gift from his wife for his 53rd birthday in 1915, the couple visited Klimt at his studio on Feldmühlgasse to have the work signed. In his diary, Schnitzler emphasized the deep connection he felt with Klimt:

“[…] Hietzing, at Klimt’s studio on Feldmühlgasse, in the heart of the old garden. He shows me his drawings, some paintings, landscapes, portraits, fantasies, finished and unfinished; the landscapes, especially, are beautiful. He has never been ‘happy’ with any of them. He signs the bought drawing, gives O. [NB: Olga Schnitzler, née Gussmann] a photograph. He shows us around the rooms and garden; and – despite all the differences between us and his artistic superiority – I feel a deeply burrowed kinship.”

Schnitzler would later immortalize Klimt with an allusion in his play Die Komödie der Verführung (1924), outlining a painter “[…] who paints two pictures of every woman that models for him. An official one in a suit, and then another.”

Schnitzler likely also had an influence on Klimt’s oeuvre. It is presumed that Klimt’s last, unfinished work, The Bride (1917/18, unfinished, Klimt-Foundation, Vienna), was inspired by Schnitzler’s 1891 novella of the same name. The character of a wife caught in her desire for unbridled sexuality, and the protagonist’s midnight blue dress, appear both in the painting and the novella.

Literature and sources

- Arthur Schnitzler. Tagebuch. schnitzler-tagebuch.acdh.oeaw.ac.at/pages/show.html (11/26/2021).

- Franz Eder, Ruth Pleyer: Berta Zuckerkandls Salon – Adressen und Gäste, Versuch einer Verortung, in: Bernhard Fetz (Hg.): Berg, Wittgenstein, Zuckerkandl. Zentralfiguren der Wiener Moderne, Vienna 2018, S. 212-233.

- Sandra Tretter: „Phantasien, vollendete und unvollendete“. Gustav Klimts Allegorie Die Braut im Kontext seines Spätwerks und Arthur Schnitzlers gleichnamiger Novelle, in: Sandra Tretter, Hans-Peter Wipplinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Jahrhundertkünstler, Ausst.-Kat., Leopold Museum (Vienna), 22.06.2018–04.11.2018, Vienna 2018, S. 167-177.

- Vera Brantl: Die familiären, politischen und kulturellen Netzwerke Berta Zuckerkandls, in: Bernhard Fetz (Hg.): Berg, Wittgenstein, Zuckerkandl. Zentralfiguren der Wiener Moderne, Vienna 2018, S. 234-243.

- Felix Czeike (Hg.): Historisches Lexikon Wien, Band 5, Vienna 1997, S. 117-118.

- Österreichisches Biographisches Lexikon. Arthur Schnitzler. www.biographien.ac.at/oebl/oebl_S/Schnitzler_Arthur_1862_1931.xml (08/25/2022).

- Gerhard Hubmann: Menschen, die einmal beinahe Freunde waren, in: Marcel Atze (Hg.): Im Schatten von Bambi. Felix Salten entdeckt die Wiener Moderne. Leben und Werk, Ausst.-Kat., Vienna Library in City Hall (Vienna) - Vienna Museum MUSA (Vienna), 15.10.2020–19.09.2021, Vienna 2020, S. 184-205.

- Arthur Schnitzler Tagebuch. Akademie der Wissenschaften. www.oeaw.ac.at/de/acdh/projects/arthur-schnitzler-tagebuch (11/26/2021).

- Tagebucheintrag von Arthur Schnitzler vom 20.10.1911 (10/20/1911).

- Tagebucheintrag von Arthur Schnitzler vom 22.03.1907 (03/22/1907).

- Tagebucheintrag von Arthur Schnitzler vom 05.12.1912 (12/05/1912).

- Tagebucheintrag von Arthur Schnitzler vom 18.05.1915 (05/18/1915).

- Tagebucheintrag von Arthur Schnitzler vom 16.03.1916 (16.03.1916).