Felix Albrecht Harta

Felix Albrecht Harta, before 1930

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

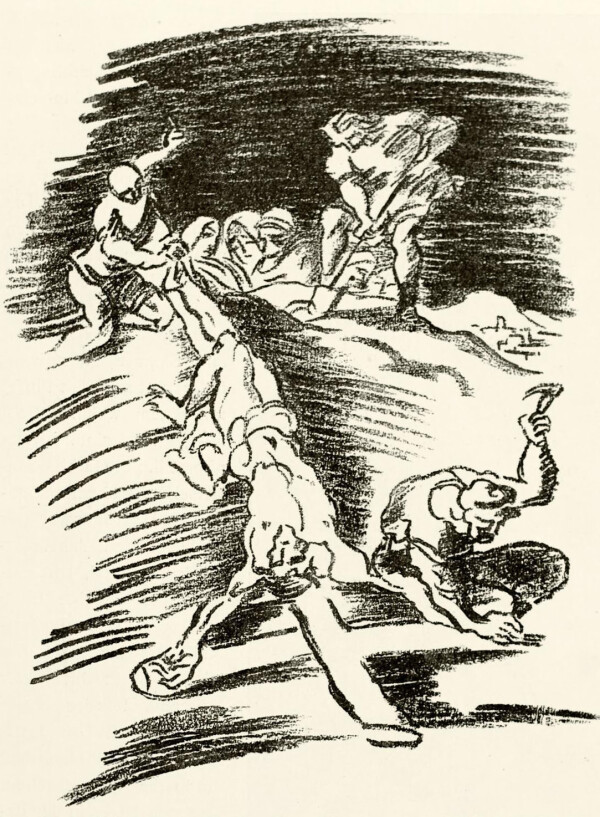

Felix Albrecht Harta: Christ is nailed to the cross, in: Die Graphischen Künste, 43. Jg. (1920).

© Heidelberg University Library

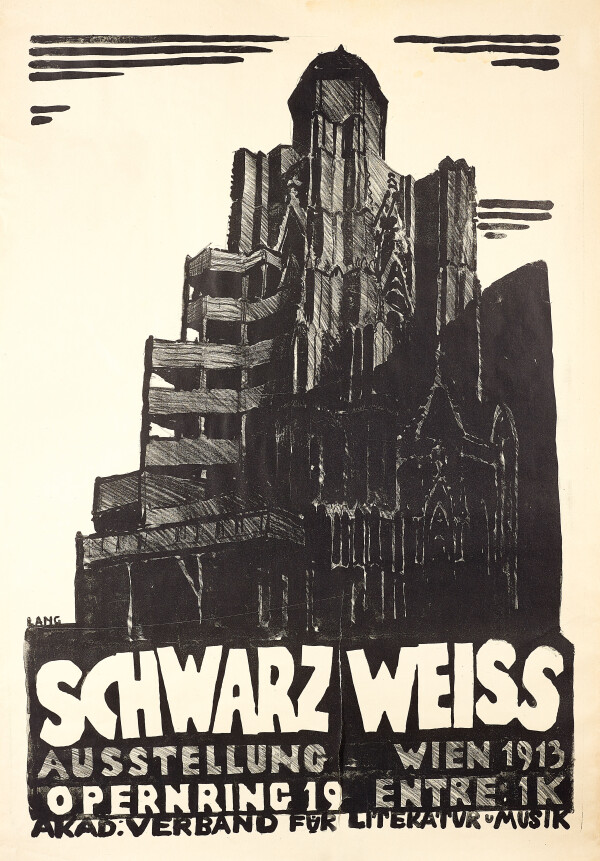

Erwin Lang: Poster of the International Black and White Exhibition, 1913

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Like Egon Schiele and Anton Faistauer, Felix Albrecht Harta was an important protagonist of Expressionism in Austria. Together with Klimt, Schiele and Faistauer he advocated for the promotion of modern art in Vienna and Salzburg.

Harta was born Felix Albrecht Hirsch on 2 July 1884. He was the son of a wealthy Jewish family from Budapest, but grew up in Vienna. Like his brother, the actor and painter Ernst Reinhold, Felix changed his surname, calling himself Felix Albrecht Harta. At the request of his father, he studied architecture at the Technical College in Vienna. From the spring of 1905 he turned to painting, his true passion. He went to Germany and studied with Hans von Hayek at the artists’ school in Dachau. Later in the same year he went on to study at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, where he was taught by Hugo von Habermann and befriended renowned German artists.

After his graduation in 1908, Harta went on various study trips. In Paris he exhibited at the modern Salon d'Automne and established close ties to French Impressionists. In Spain he explored the works of Velasquez, El Greco and Goya.

Harta and Viennese Modernism

Harta returned to Vienna in 1909. There, he came into contact with a group of young artists including Egon Schiele, Anton Faistauer, Oskar Kokoschka and Paris von Gütersloh, who regularly met at the Café Museum. Harta impressed his fellow artists with his knowledge of international art. He made friends not only with these young painters but also with established artists such as Gustav Klimt. Even though Harta was part of Schiele’s social circle, it is presumed that he was no founding member of the Neukunstgruppe, since he did not participate in the association’s first three exhibitions at the Pisko Gallery.

Harta got engaged to Elisabeth Hermann in 1911, but they did not marry until 1914. Her family owned a property in Vienna-Hietzing, 13th District, at Feldmühlgasse 9 (now 11). It is presumed that Harta introduced Gustav Klimt, who was looking for a new studio at the time, to his in-laws. They subsequently rented the building (now Klimt Villa) to Klimt until his death in 1918. In 1914, Harta and his family moved into a house on the same street at number 12, directly opposite Klimt’s studio.

Klimt, Schiele and the Austrian Artists’ League

Harta was no member of the Vienna Secession nor the Künstlerhaus, but he repeatedly exhibited at both institutions. He participated in the “Sonderbundausstellung” [“Special Interest Society Exhibition”] in Cologne in 1912 and in the “XLIII. Ausstellung der Vereinigung Bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession” [“43rd Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists Secession”] in the following year. He also participated in the exhibition of the Austrian Artists’ League at the Künstlerhaus in Budapest in 1913 and in the association’s exhibition at the Rome Secession in 1914. This was followed by the “Wiener Kunstschau” at the Berlin Secession in 1916, which was also organized by the Austrian Artists’ League, led by its president Gustav Klimt. It is presumed that Harta, like his friend Egon Schiele, was a member of the Austrian Artists’ League from 1913, but his membership is confirmed only from 1917.

In 1913, Harta traveled to Paris together with Gütersloh. There, he met the Futurists Marinetti, Boccioni and Severini. At the end of the year, he was a co-organizer of the “Internationale Schwarz-Weiß-Ausstellung” [“International Black-and-White Exhibition”] in Vienna, one of the most important art shows since the two “Kunstschau” exhibitions.

After the onset of World War I, Harta’s friendship with Schiele evidently grew closer in 1915/16. The two artists created numerous portrait drawings of each other and corresponded frequently. Harta joined the military in 1916. For one year, he served as a volunteer with the Imperial-Royal Army (also called “Kuk”). Harta then applied for a transfer to the much less dangerous War Press Office as a war artist. Thanks to a letter of recommendation written by Klimt in his function as president of the Austrian Artists’ League, the transfer was granted. With the art division of the Kuk he participated in two War Exhibitions in 1917 and 1918. He may have also played a part in organizing the exhibitions. A letter from Klimt dated July 1917 in which he declines an invitation to participate in an exhibition organized by Harta for lack of time might well refer to the War Exhibition.

Salzburger Kunstverein (Hg.): Der Wassermann. Katalog der Ausstellung Moderner Kunst veranstaltet von der neuen Vereinigung bild. Künstler Salzburgs Der Wassermann in der Zeit vom 20. August bis Ende September 1920 im Salzburger Künstlerhaus, Ausst.-Kat., Artists' House (Salzburg), 20.08.1920–26.09.1920, Salzburg 1920.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Der Wassermann and the Salzburg Festival

After the end of the War, Harta joined his family, who had moved to Salzburg during the War. There, he socialized with Alois Grasmayr – who, together with his wife Magda, née Mautner-Markhof, cultivated an art collection, which also included works by Klimt – as well as with the artists and writers Alfred Kubin, Stefan Zweig, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Hermann Bahr and Max Reinhardt.

Together with his old friend Anton Faistauer, Harta founded the artists’ association Der Wassermann, the first modern art movement in Salzburg. Harta was elected its president. The association’s first exhibition was held in 1919, showing works by Faistauer, Kolig, Andersen, Broncia Koller, Schiele, Kubin and Wiegele as well as visual arts with a focus on graphics, music and literature. After the first few successful exhibitions, Harta opened the Neue Galerie in 1920, which was intended as an exhibition venue for Der Wassermann. The association participated in only three exhibitions, however. Simultaneously, Harta worked with Alfred Roller, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Max Reinhardt and Richard Strauss to establish the Salzburg Festival, which is still held today.

Together, Faistauer and Harta also advocated for the creation of a memorial for Hans Makart and for the opening of a gallery of Old and New Masters (now Residenzgalerie).

Felix Albrecht Harta: Abduction, in: Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, Band 40 (1917).

© Heidelberg University Library

Return to Vienna

Harta moved back to Vienna in 1924. He lived in France in 1926 and 1927. His exhibition activity continued unabated. His works won awards in Austria and abroad. Upon his return to Vienna he joined the Hagenbund in 1928, acting as secretary, vice-president and jury member until 1930.

After the “Anschluss” in 1938, Harta faced persecution by the Nazi regime, even though he had converted to Christianity in 1921. In 1939 he emigrated to England with his family. In the same year, many of his works were destroyed in a fire at the Neue Galerie in Salzburg. Harta lived in Cambridge, where he taught until 1950. He then returned to Salzburg, where he continued to work as an artist until his death on 27 November 1967.

Literature and sources

- Nikolaus Schaffer, Weltkrieg und Künstlerfehden Salzburger Kunst und Erster Weltkrieg — eine nüchterne Bilanz. www.zobodat.at/pdf/MGSL_154-155_0541-0569.pdf (04/20/2020).

- Salzburg Museum. Faistauer, Schiele, Harta & Co - Malerei verbindet. www.salzburgmuseum.at/ausstellungen/rueckblick/ausstellungen-seit-2015/faistauer-schiele-harta-co-painting-connects-us/ (04/20/2020).

- Kunsthandel Widder. www.kunsthandelwidder.com/en/artists/felixalbrechtharta/biography (04/20/2020).

- Hieke Kunsthandel. www.hieke-art.com/felix-a-harta (04/20/2020).

- Gieser und Schweiger. www.gieseundschweiger.at/de/artist/4101 (04/20/2020).

- belvedere. digital.belvedere.at/people/733/felix-albrecht-harta (04/20/2020).

- N. N.: Kleine Kunstwanderung, in: Der Wiener Tag, 22.11.1932, S. 7.

- N. N.: Geburtenausweis, in: Salzburger Volksblatt: unabh. Tageszeitung f. Stadt u. Land Salzburg, 05.11.1920, S. 4.

- Laura Erhold, Sandra Tretter: »Am Wege durch mein[en] Garten heute der Geruch wie Frühlingsduft – Vogelgesang – die Knospen weiten sich«. Biografisches zu Gustav Klimt im Kontext des floralen Jugendstils und der Naturwahrnehmung um 1900, in: Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Florale Welten, Vienna 2019, S. 117-128, S. 124.

- Konstanze Fliedl, Marina Rauchenbacher, Joanna Wolf (Hg.): Handbuch der Kunstzitate: Malerei, Skulptur, Fotografie in der deutschsprachigen Literatur der Moderne, Band 1, Boston 2011, S. 676.

- Christine Lubkoll, Günter Osterle: Gewagte Experimente und kühne Konstellationen: Kleists Werk zwischen Klassizismus und Romantik, Würzburg 2001, S. 216.

- Felix Salten: Gustav Klimt – Gelegentliche Anmerkungen. mit Buchschmuck von Berthold Löffler, Leipzig 1903.

- Pester Lloyd, 23.02.1913, S. 13.

- Familie Harta. www.faharta.com/biography (07/12/2021).

- Berliner Secession (Hg.): Wiener Kunstschau in der Berliner Secession Kurfürstendamm 232, Ausst.-Kat., Exhibition house on Kurfürstendamm (Berlin), 08.01.1916–20.02.1916, Berlin 1916.

- Pester Lloyd, 01.10.1911, S. 16.

- Brief vom Bund österreichischer Künstler an das k. k. Ministerium für Kultus und Unterricht, unterschrieben von Gustav Klimt als Präsident (02/26/1917). AOK KPQ Bund Österreichischer Künstler fol.15, .

- N. N.: Die österreichischen Staatspreise für bildende Kunst, in: Bregenzer/Vorarlberger Tagblatt, 04.06.1929, S. 2.