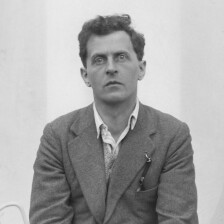

The Wittgenstein Family

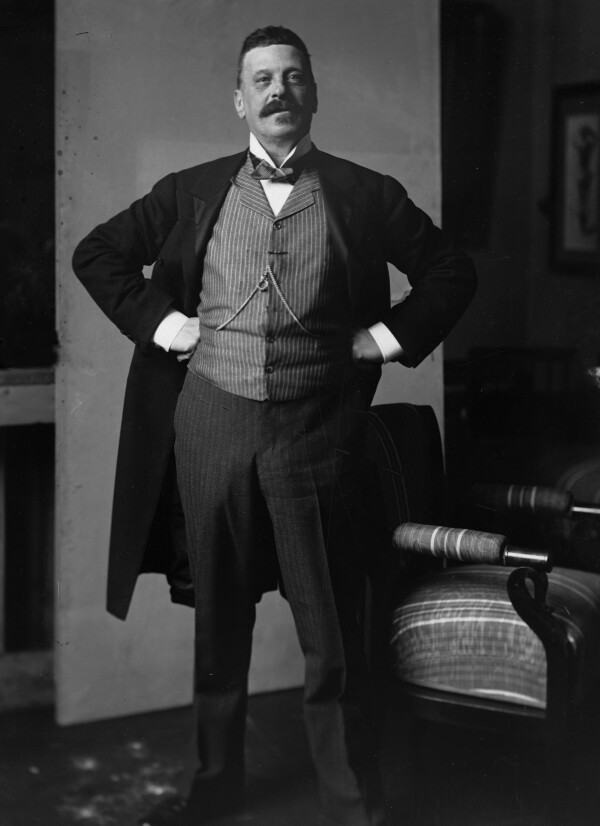

Karl Wittgenstein photographed by Ferdinand Schmutzer, 1908, Austrian National Library, Vienna

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

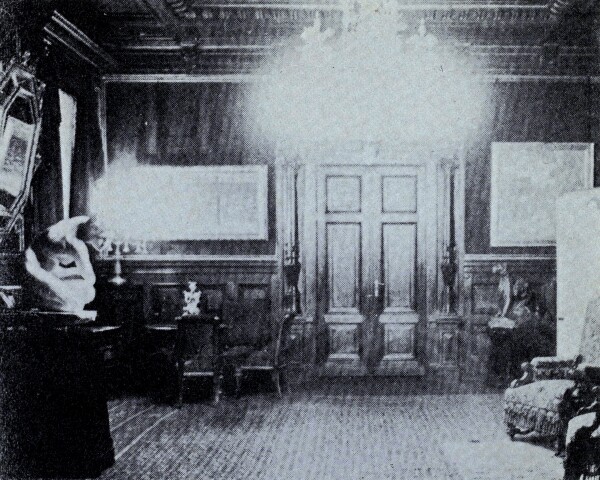

Palais Wittgenstein photographed by Julius Scherb, 1918, Austrian National Library, Vienna

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Around 1900, the Wittgenstein family was one of the richest families in the Habsburg monarchy. Paterfamilias Karl Wittgenstein was one of the most important patrons of Gustav Klimt and Viennese Modernism. He supported the Secession financially and provided the Wiener Werkstätte with major commissions. His daughter Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein was portrayed by Klimt in 1905.

Karl Otto Clemens Wittgenstein, the head of the Wittgenstein family, came from an assimilated German-Jewish family whose ancestor Moses Meyer had worked for Count of Sayn-Wittgenstein and consequently adopted the name Wittgenstein. Karl’s parents, Hermann Wittgenstein and Franziska “Fanny”, née Figdor, sister of the famous art collector Albert Figdor, converted to the Protestant faith before their marriage and committed themselves to the promotion of cultural life.

Karl was born in Gohlis (now Leipzig) in 1847, the son of a now-Protestant family. In 1851, the Wittgensteins moved to Vösendorf near Vienna. At the age of seventeen, Karl Wittgenstein emigrated to the USA on his own initiative, where he kept his head above water with occasional jobs. After his return to Vienna he studied at the University of Technology and then built up a huge empire in the iron and steel industry. From 1875 to 1899 he successfully controlled the Teplitz Rolling Mill in Bohemia and founded the first Austrian iron cartel.

In addition to his business activities, Karl Wittgenstein was interested in music and art. Through musical evenings with his family he met the talented pianist Leopoldine “Poldi” Kalmus, whom he married in 1874. The couple had nine children, only eight of which reached adulthood. At the request of their Catholic mother, all of the children were brought up according to the Roman Catholic faith. Hermine, the eldest daughter, was her father’s confidante and accompanied him on his business trips from an early age. She had two sisters, Helene and Margarethe, as well as five brothers, Paul, Ludwig, Konrad, Hans, and Rudolf. All sons except Paul and Ludwig took their own lives at a young age. Paul became a well-known pianist, while Ludwig developed into a famous philosopher.

Karl Wittgenstein ensured that his children received a profound artistic education. The Wittgenstein Palace at No. 16 Alleegasse (now Argentinierstraße) regularly accommodated outstanding artists.

The Children of the Wittgenstein Family

Gustav Klimt: The Golden Knight (Life a Battle), 1903, Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art

© Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art, Nagoya

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein, 1905, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen - Neue Pinakothek München

© bpk | Bavarian State Painting Collections

Insight into the Palais Wittgenstein, presumably circa 1910, private collection

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Karl Wittgenstein and Viennese Modernism

In 1898, Karl Wittgenstein, one of the wealthiest industrialists in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, retired from business at the early age of 51 years, devoting himself primarily to promoting the arts. Initially, the focus of his collection was predominantly on objects from the field of music. A crucial motivation for his interest in modern art was certainly his eldest daughter and confidante Hermine. She took painting lessons from Rudolf von Alt, Franz Hohenberger, and Johann Victor Krämer, all of whom were members of the Secession, and was an enthusiastic supporter of Klimt. Karl Wittgenstein made the young woman, who remained unmarried throughout her life, the custodian of his art collection and asked her to advise him on his purchases. From the turn of the century, Karl’s patronage therefore focused primarily on the Vienna Secession and the Wiener Werkstätte. In 1897/98 he financed the construction of the Secession building with the considerable sum of about 50,000 guilders (approx. 748,400 euros). At the Secession exhibitions he mainly purchased paintings by Rudolf von Alt, Giovanni Segantini, and Gustav Klimt.

Gustav Klimt and the Wittgenstein Family

In 1903, Wittgenstein purchased his first Klimt painting, The Golden Knight (Life Is a Battle) (1903, Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art, Nagoya). The work was installed in the staircase of the palace on Alleegasse.

On the occasion of the engagement of their youngest daughter, Margarethe, to the wealthy American Jerome Stonborough in 1903, the Wittgenstein couple commissioned Klimt to paint a life-size portrait of the young bride, who preferred to use the English version of her name, “Margaret,” after her marriage. The painting process would take a very long time and involved repeated phases of overpainting. Klimt presented Portrait of Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein (1905, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Neue Pinakothek, Munich) for the first time in Berlin in 1905 at the “II. Ausstellung des Deutschen Künstlerbundes” [“2nd Exhibition of the Union of German Artists”]. Klimt himself described it as still unfinished in a loan request to Karl Wittgenstein:

“[M]ay I ask for the painting ‘The Golden Knight,’ which is owned by you, for the art exhibition in Berlin? And also for the portrait of your daughter, although the picture is still not finished?”

In May 1905, the Neue Freie Presse reported that Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein was personally present at the Berlin exhibition to witness the debut of her portrait, which was still a work in progress:

“What was particularly admired was the portrait of a slender young woman, and it attracted all the more attention because the Viennese original, who had married an Englishman [note: her husband was American, not English], was frequently present in the exhibition room.”

The painting seems to have finally been completed in 1906, when it was installed at the Wittgenstein Palace, first in the staircase and subsequently in the drawing room. The fact that Margaret left the portrait behind in Vienna when she moved to Berlin has often been interpreted in literature as a rejection of the painting on her part. However, there is no concrete source that would prove this assertion.

In addition to these two paintings by Klimt, Karl Wittgenstein also owned Sunflower (1907/08, Belvedere, Vienna), Water Snakes I (Parchment) (1904, reworked before 1907, Belvedere, Vienna), Cottage Garden with Sunflowers (1906, Belvedere, Vienna), and Kammer Castle on the Attersee IV (1910, private collection).

Even after the so-called Klimt Group had left the Secession in 1905, the Wittgenstein family would continue to support the artist as a sponsor. On the occasion of the organization of the “Internationalen Kunstschau Wien 1909,” for which Klimt acted as president, he wrote to Emilie Flöge: “Witt. has also given 10.” This appears to have been a subsidy from Karl Wittgenstein for the exhibition of 10,000 crowns (approx. 62,780 euros). Together with the Ministry of Labor, he thus made it possible for the art exhibition to take place.

In addition to Klimt, Karl Wittgenstein also supported Max Klinger, Auguste Rodin, Anton Hanak, Johann Victor Krämer, Ferdinand Hodler, and Rudolf von Alt. The Wittgenstein family also employed the photographer Moriz Nähr, who was a friend of Klimt and worked for the Secession, as a personal family photographer. A close friendship developed between Nähr and Ludwig Wittgenstein, and the latter engaged the photographer for important commissions even after the death of his father Karl in 1913.

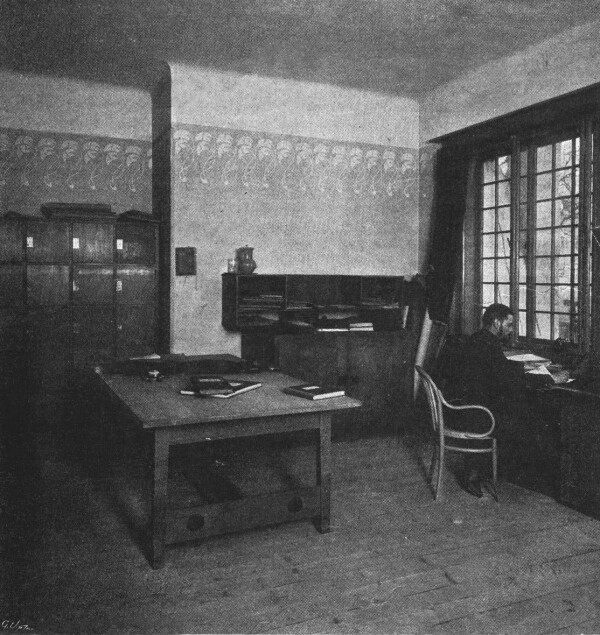

Parlor in Karl Wittgenstein's forester's lodge designed by Josef Hoffmann, around 1901, in: Der Architekt. Wiener Monatshefte für Bau- und Raumkunst, 7. Jg. (1901).

© ANNO | Austrian National Library

The Wittgenstein Family and the Wiener Werkstätte

The Wittgenstein family was also an important client for Josef Hoffmann and the Wiener Werkstätte. In 1905, Karl Wittgenstein had a hunting lodge built by Hoffmann on the Hochreith mountain pasture. It was completely decorated by the Wiener Werkstätte as a Gesamtkunstwerk or universal work of art. That same year, Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein and her husband Jerome commissioned the Wiener Werkstätte to decorate their apartment in Berlin. Moreover, the frame of Klimt’s portrait of Margaret was designed by Hoffmann and executed by the Wiener Werkstätte. In 1912, Karl Wittgenstein ordered a portal and the interior decoration for the Poldihütte office headquarters on Invalidenstraße. Two years later, Paul Wittgenstein, Karl’s brother, even became a partner in the Wiener Werkstätte. He had entrusted Josef Hoffmann with the reconstruction of his Bergerhöhe country estate in 1899.

Karl Wittgenstein’s Death – A Drastic Change in Patronage

After Karl Wittgenstein’s death on 12 January 1913, his children, who had inherited his entire possessions, continued the family’s collecting activities. Both Hermine and Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein were named as donors on the occasion of the opening of the Modern Gallery at the Orangery of the Belvedere in 1929. Shortly after Karl’s death, the Secession, which had benefited from his support over many years, had a commemorative plaque installed on the Secession building in remembrance of its deceased patron.

A reorientation of his children, who increasingly embraced artists of the new generation, meant that they gradually lost interest in the Secessionists and the Wiener Werkstätte. Margaret, who lived in Berlin, Paris, and Zurich, collected international art, particularly by Expressionist and Impressionist artists. Jerome and Margaret Stonborough’s French art collection, shown at the Secession’s 132th exhibition in 1934, included outstanding works by Matisse, Gauguin, Picasso, Modigliani, and Utrillo.

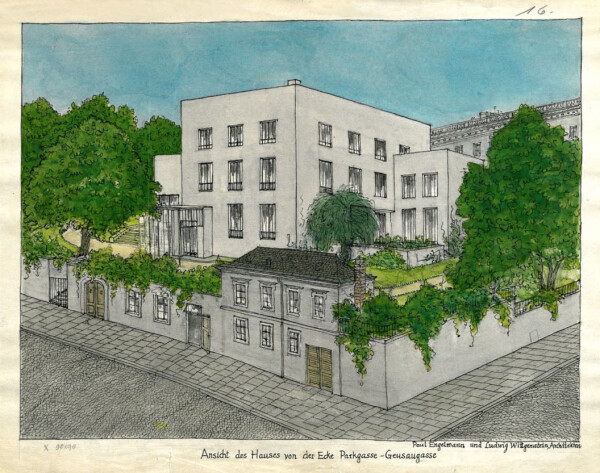

Paul Engelmann and Ludwig Wittgenstein: Design for the Villa Wittgenstein at Kundmanngasse 19, view from the corner of Parkgasse/Geusaugasse, 1926

© WStLA - Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna

In 1917, Hermine and her brother Paul Wittgenstein commissioned Paul Engelmann, a student of Adolf Loos, rather than Josef Hoffmann, to redesign the Neuwaldegg and Hochreith country estates. Between 1926 and 1929, Engelmann eventually realized a private residence (Villa Wittgenstein) for Margaret at No. 19 Kundmanngasse, based on Ludwig Wittgenstein’s idea.

With Austria’s “Anschluss” to Nazi Germany in 1938, the Wittgensteins were forced to flee to the USA due to their Jewish origins. The commemorative plaque for Karl Wittgenstein on the Secession building was removed for so-called “racial reasons.”

After the war, Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein returned to her villa on Kundmanngasse. She was able to recover a large part of her father’s art collection, including her portrait by the hand of Gustav Klimt.

Literature and sources

- Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Chiffre: Sehnsucht – 25. Gustav Klimts Korrespondenz an Maria Ucicka 1899–1916, Vienna 2014.

- Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Florale Welten, Vienna 2019.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Die Welt von Klimt, Schiele und Kokoschka. Sammler und Mäzene, Cologne 2003.

- Bernhard Fetz (Hg.): Berg, Wittgenstein, Zuckerkandl. Zentralfiguren der Wiener Moderne, Vienna 2018.

- Uwe Schögl, Hans-Peter Wipplinger (Hg.): Moriz Nähr. Fotograf der Wiener Moderne / Photographer of Viennese Modernism, Ausst.-Kat., Leopold Museum (Vienna), 24.08.2018–29.10.2018, Vienna - Cologne 2018.

- Wien Geschichte Wiki. Villa Wittgenstein. www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Villa_Wittgenstein (08/26/2021).

- Ursula Prokop, Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein: Bauherrin, Intellektuelle, Mäzenin, Cologne 2016.

- Trauungsbuch 1873 (Tomus 91), röm.-kath. Dompfarre St. Stephan, Wien, fol. 64.

- Elana Shapira: Style & Seduction. Jewish Patrons, Architecture and Design in Fin de Siècle Vienna, Waltham 2016.

- Ludwig Hevesi: Max Klinger in Wien, 13. April 1902, in: Acht Jahre Sezession (März 1897–Juni 1905). Kritik – Polemik – Chronik, Vienna 1906, S. 383.

- N. N.: [Karl Wittgenstein.], in: Neue Freie Presse, 25.01.1913, S. 9.

- N. N.: Karl Wittgenstein als Kunstfreund, in: Neue Freie Presse, 21.01.1913, S. 10-11.

- N. N.: Eröffnung der Ausstellung des Deutschen Künstlerbundes. Telegramme der "Neuen freien Presse", in: Neue Freie Presse (Morgenausgabe), 20.05.1905, S. 9.

- Neue Freie Presse, 13.04.1902, S. 7.

- N. N.: Handel, Industrie und Verkehr. Karl Wittgenstein †, in: Fremden-Blatt, 21.01.1913, S. 25.

- N. N.: Karl Wittgenstein gestorben, in: Illustrierte Kronen Zeitung, 21.01.1913, S. 5.