Sonja Knips

Sonja Knips photographed by Friedrich Viktor Spitzer, 1907, in: Photographische Rundschau und photographisches Centralblatt. Zeitschrift für Freunde der Photographie, 22. Jg., Heft 3 (1908).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Sonja Knips, 1897/98, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

© Belvedere, Vienna

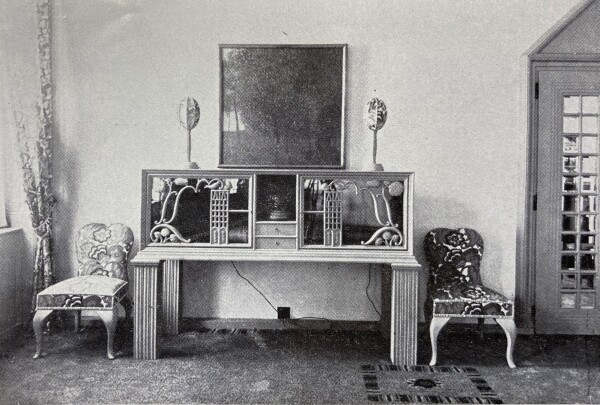

Bruno Reiffenstein (?): Insight into the apartment of Sonja and Anton Knips, 1916, in: Der Architekt. Wiener Monatshefte für Bau- und Raumkunst, 21. Jg. (1916/18).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Insight into the Villa Knips, presumably 1920s, Verbleib unbekannt

© APA-PictureDesk

Sonja Knips was a prominent personality in Vienna in the early 20th century. As a supporter of the Wiener Werkstätte, a patron of the arts and an art collector, she influenced the development of Viennese Modernism. She was especially close to Gustav Klimt and Josef Hoffmann.

Sonja Knips was born in Lemberg (now Ukraine) on 2 December 1873. She descended from a noble family of Austrian army officers. Born as Baroness Potier des Echelles, she was christened Sophia Amalie Maria. Her family was not wealthy but enjoyed high social status.

She trained as a teacher and worked as a companion until she married the wealthy industrialist Anton Knips in 1896. They had two sons. Their married life was rather unconventional for the time, however. Sonja Knips was very emancipated and pursued her personal interests unabashedly. Despite frequent disputes about her high expenses, her husband financed restorations, remodeling and construction work, extravagant clothes and her collecting activities as a patron of the arts.

Sonja Knips was interested in Vienna’s avant-garde and presumably met Gustav Klimt even before 1895, which was when he presented her with a fan, a drawing and a poem. Klimt created the Portrait of Sonja Knips (1897/98, Belvedere, Vienna), which the newly founded artists’ association Vienna Secession presented for the first time at the “II. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession” [“2nd Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists Secession”] in 1898. The square format shows Knips in a pale pink dress in front of a dark background and became one of the key works of Secessionism. It also marked the beginning of Klimt’s career as a portraitist of Vienna’s high society. Sonja Knips is holding a small book, presumably Klimt’s sketchbook bound in red leather, which was among her private possessions. It is one of only three surviving sketchbooks by Klimt and contains drawings and notes dating from 1897 to around 1900. A photograph of Gustav Klimt was also inserted in the book. Apart from her own portrait, Sonja Knips also purchased Klimt’s paintings Fruit Trees (1901, privately owned) and Adam and Eve (1916–1918 (unfinished), Belvedere, Vienna).

A diary entry by Knips documents that she had the apartment she shared with her husband at Gumpendorferstraße 15 redecorated by Josef Hoffmann from 1901. She also commissioned Hoffmann to build a cottage in Seeboden am Millstätter See in Carinthia. Hoffmann and Koloman Moser together created the cottage and its interior decoration, which followed a consistent design. Its construction began in 1905. The cottage on the lake, which had its own jetty, served as a refuge for Sonja Knips, especially during the summer months, when she sought to escape the noise and heat of the city.

As a client and patron she supported the ideas of the Wiener Werkstätte. Her commitment is illustrated by a 1907 photograph, which shows Sonja Knips, Berta Zuckerkandl and Lili Waerndorfer in the booth of the Wiener Werkstätte at the “Künstler-Gartenfest” [“Artists’ Garden Party”] at Weigls Dreher Park. According to newspaper reports, Knips worked at the “Künstlerbude” [“Artists’ Booth”] together with Lili Waerndorfer, Serena Lederer and Berta Zuckerkandl. The women wore fashionable reform dresses and hats: Knips not only regularly bought jewelry and clothes by the Wiener Werkstätte, she was also one of the earliest clients of the “Schwestern Flöge” fashion salon, which opened in 1904.

Apart from her cottage in Carinthia, Knips also wanted “a house with garden” in Vienna, as she noted in her diary. She purchased a large property at Nusswaldgasse 22 in Vienna-Döbling, 19th District, in 1915. The previous owner had been Berta Zuckerkandl, who had hosted her legendary salon there. Sonja Knips moved into the derelict building around 1916 and again commissioned Hoffmann to create a new building, designed as a Gesamtkunstwerk [universal work of art], which was completed in 1925.

The house – also called the Knips Villa – was a popular meeting place, where rounds of cards, home concerts and “artists’ evenings” were held. Knips frequently hosted Vienna’s high society and also invited international artists and intellectuals. Her guests for instance included Henry van de Velde, Peter Behrens, Josef August Lux, Carl Moll, Emilie Flöge and Mäda Primavesi. Several artists of Vienna’s former avant-garde, such as Josef Hoffmann, Eduard Wimmer-Wisgrill and Anton Hanak, continued to meet at the house until the 1930s.

Aged 85, Sonja Knips died of a heart attack in May 1959. She died in Seeboden, where she is also buried.

Literature and sources

- Manu Miller: Sonja Knips und die Wiener Moderne. Gustav Klimt, Josef Hoffmann und die Wiener Werkstätte gestalten eine Lebenswelt, Vienna 2004.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2017, S. 505-506, Nr. 114.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Klimt and the Women of Vienna's Golden Age. 1900–1918, Ausst.-Kat., New Gallery New York (New York), 22.09.2016–16.01.2017, London - New York 2016, S. 116.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band IV, 1878–1918, Salzburg 1989, S. 73-74.

- Christian M. Nebehay: Gustav Klimt. Das Skizzenbuch aus dem Besitz von Sonja Knips, Vienna 1987.

- N. N.: Gartenfest in Weigls Dreherpark, in: Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 07.06.1907, S. 9-10.

- N. N.: Künstlerisches Gartenfest, in: Neue Freie Presse, 07.06.1907, S. 12.

- Walter Riezler: Haus von Sonja Knips in Wien, in: Die Form. Zeitschrift für gestaltende Arbeit, Heft 1 (1927), S. 17-20.