Fritz Waerndorfer

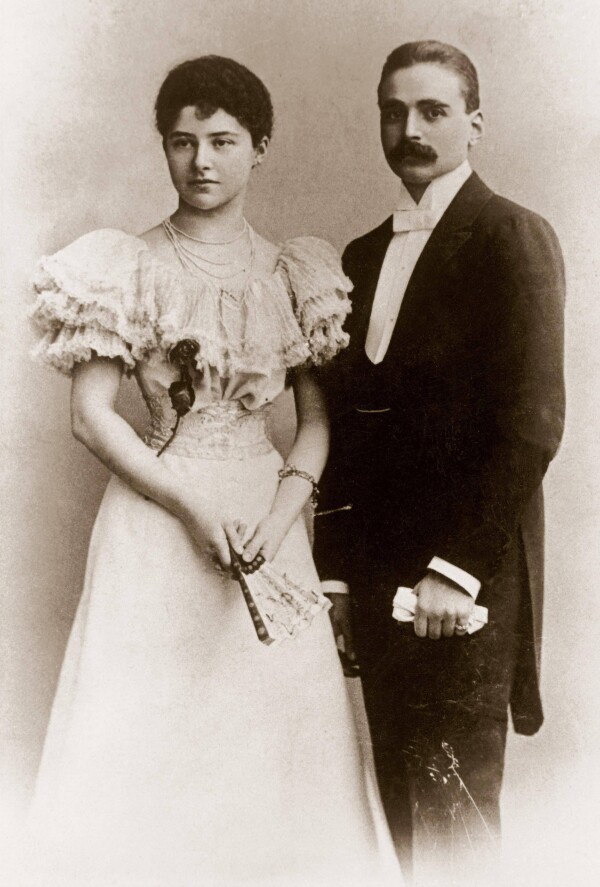

Lili and Fritz Waerndorfer, around 1895

© APA-PictureDesk

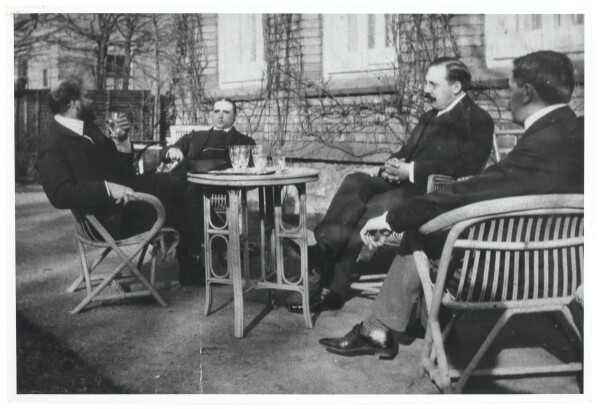

Gustav Klimt in the garden of Fritz Waerndorfer's villa, presumably circa 1903, Verbleib unbekannt

© Private collection

View into Villa Waerndorfer, 1903/04, MAK - Museum für angewandte Kunst, Archiv der Wiener Werkstätte

© MAK

The Austrian entrepreneur, patron of the arts, and co-founder of the Wiener Werkstätte had a crucial influence on Vienna’s fin-de-siècle art scene through his social connections and commitment. He collected paintings by Gustav Klimt as well as works by international avant-garde artists and supported Josef Hoffmann and Kolo Moser.

Fritz Waerndorfer (originally Wärndorfer), coming from a wealthy Jewish industrialist family, was born in Vienna on 5 May 1868, the son of textile manufacturer Samuel Wärndorfer and his wife Berta, née Neumann. His aunts on his mother’s side – Marianne and Jenny Neumann – were married to Moriz Benedict and Isidor Mautner respectively, and the three brothers-in-law ran the Wärndorfer-Benedict-Mautner cotton mill, one of the monarchy’s largest textile companies, with its headquarters in Náchod (now Czech Republic).

After graduating from the Akademisches Gymnasium in Vienna, Fritz Waerndorfer did his military service until 1889 and then spent time studying in England, where he frequented the art scene and began collecting art. In 1895 he was employed in the family business, of which he later became a partner. In 1896 he married the author and translator Lili Jeanette Hellmann, and they had three children.

By the turn of the century, he was in close contact with Hermann Bahr and was a guest at Berta Zuckerkandl’s salon. It was probably through this connection that he also met the founders of the Vienna Secession, Gustav Klimt, Josef Hoffmann, Carl Moll, and Kolo Moser. Waerndorfer supported and commissioned the friends of the young association and compiled a collection with works by Richard Luksch, Marcus Behmer, Aubrey Beardsley, George Minne, and Klimt’s paintings Pallas Athene (1898, Wien Museum, Vienna), Orchard in the Evening (1899, Leopold Museum, Vienna), A Morning by the Pond (1899, Leopold Museum, Vienna), Farmhouse with Birch Trees (1900, private collection), From the Realm of Death (Stream of the Dead) (1903, whereabouts unknown, lost since the end of the war in 1945), and Hope I (1903/04, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa).

As Waerndorfer spoke English fluently and was familiar with the latest British design trends, Hoffmann asked him to travel to Glasgow in the spring of 1900 to persuade Charles Rennie Mackintosh to take part in the “VIII. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Secession” [“8th Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists Secession”]. In November, Mackintosh exhibited in Vienna alongside Charles Robert Ashbee, Henry van de Velde, George Minne, and others within the trend-setting group of Scottish Modern Style artists referred to as The Four. The groundbreaking show, organized by Moll as the Secession’s president and Hoffmann as its vice president, led to a programmatic revaluation of the decorative arts. For the duration of the exhibition, the Mackintosh couple lived at Waerndorfer’s villa at No. 45 Carl-Ludwig-Straße (now No. 59 Weimarer Straße) in the Cottage District of Währing (18th District). By 1902, Waerndorfer commissioned them to decorate his music salon. Margaret MacDonald Mackintosh designed a three-panel frieze featuring the motif The Seven Princesses (1906, MAK) from Maurice Maeterlinck’s play of the same name, which, however, would not make its way into the salon until 1907.

He also co-founded the Wiener Werkstätte in 1903 with Hoffmann and Moser, following the example of the English Arts and Crafts Movement. The aim was to renew the concept of art in the fields of the decorative arts and the production of furniture, everyday objects, and jewelry. He also initiated the redecoration of Klimt’s studio in Josefstädter Straße. Klimt wrote to Mizzi Zimmermann in the summer of 1903:

“This mister from the Cottage quarter wished to redecorate my studio at his cost during my absence, meant as a surprise – I was not supposed to know anything – the housekeeper would not tolerate it – but she checked with me – I had a hard time warding off his otherwise commendable intention […].”

Klimt refused to have the rooms redesigned completely, and only some furniture designed by Hoffmann and made by the Wiener Werkstätte was added to the studio at the end of the year.

Through the modernization of his house, his collecting activities, and the promotion of international artists, Waerndorfer positioned himself as an influential personality in Viennese society and the art and cultural scene, as he also hosted numerous get-togethers. Ludwig Hevesi described such a visit to the villa on 25 November 1905:

“A double door concealing a large picture is hermetically closed to keep any profane eye off. The picture in question is the famous, or let us say, notorious, ‘Hope’ by Klimt. Namely that young woman expecting in a most interesting way whom the artist dared to paint in the nude. One of his masterpieces.”

In 1906, Waerndorfer traveled to London with Klimt, Hoffmann, and Carl Otto Czeschka to visit the “Imperial-Royal Austrian Exhibition” at Earls Court on the occasion of the presentation of Austrian arts and crafts. The return journey took them via Brussels, where they visited the site of the Stoclet Palace, one of the Wiener Werkstätte’s most comprehensive projects in the sense of a Gesamtkunstwerk or universal work of art.

Hoffmann and the Wiener Werkstätte were also responsible for the artistic design of the Cabaret Fledermaus, which had been founded in 1907. Waerndorfer as an ambitious patron saw to an avant-garde program with performances by Egon Friedell, Peter Altenberg, and Alfred Polgar, modern dance choreographies featuring the Wiesenthal sisters and shadow plays by Oskar Kokoschka. Waerndorfer also employed the latter as an art teacher for his children and encouraged him to design his children’s book The Dreaming Boys (1908).

In 1909, in order to pay back one of the Wiener Werkstätte’s bank loans that had become due from his personal assets, he sold his family shares in the cotton mill. In 1911 he sold the Cabaret Fledermaus. As the Wiener Werkstätte’s debts continued to mount, production was discontinued in 1913 and bankruptcy was declared.

One year later, Waerndorfer, urged by his family and Hoffmann, finally left the company and moved to the USA. There he called himself Frederick or Fred Warndof, worked as a farmer in Florida and applied for American citizenship in 1919. He also lived in Savannah (Georgia), where his uncle Isidor Mautner got him a job as a coordinator for cotton deliveries. In the mid-1920s he moved to New York and cultivated contacts with Friedrich Kiesler and Vally Wieselthier. He worked as a textile designer and painter under the pseudonym of Warndof. His marriage to Lili ended in divorce in 1930, and in 1931 he married the young English-born pianist and composer Fiona McCleary, whom he had met in 1928. Fritz Waerndorfer died in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, on 9 August 1939.

Literature and sources

- MAK Blog. blog.mak.at/der-waerndorfer-fries-im-mak/ (03/31/2020).

- Österreichisches Biographisches Lexikon. Fritz Waerndorfer. biographien.ac.at/oebl/oebl_W/Waerndorfer_Fritz_1868_1939.xml (08/25/2020).

- Peter Vergo: Fritz Waerndorfer as Collector, in: Alte und moderne Kunst. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Kunst, Kunsthandwerk und Wohnkultur, 26. Jg., Heft 177 (1981), S. 33-38.

- Elana Shapira: Modernism and Jewish Identity in Early Twentieth-Century Vienna: Fritz Waerndorfer and His House for an Art Lover, in: Studies in the Decorative Arts, Band 13 (2006), S. 52-92.

- Heinz Spielmann, Hella Häussler, Rüdiger Joppien: Carl Otto Czeschka. Ein Wiener Künstler in Hamburg. Mit unveröffentlichten Briefen, Goettingen 2019, S. 446-448.

- Peter Noever (Hg.): Ein moderner Nachmittag. Margaret MacDonald Mackintosh und der Salon Waerndorfer in Wien, Vienna 2000.

- Peter Vergo: Fritz Waerndorfer and Josef Hoffmann, in: The Burlington Magazine, 125. Jg., Heft 964 (1983), S. 402-410.

- Siegfried Geyer: Der Leidensweg der Wiener Werkstätte, in: Die Bühne. Wochenschrift für Theater, Film, Mode, Kunst, Gesellschaft, Sport, 3. Jg., Heft 81 (1926), S. 6-9.

- Ludwig Hevesi: Ein moderner Nachmittag, in: Flagranti und andere Heiterkeiten, Stuttgart 1909, S. 166-167.

- Ludwig Hevesi: Haus Wärndorfer, in: Altkunst – Neukunst, Vienna 1909, S. 221–227.

- Brief mit Kuvert von Gustav Klimt in Kammer am Attersee an Maria Zimmermann in Villach (28.08.1903). S64/24.

- Brief von Fritz Waerndorfer in Wien an die Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs (03.04.1901). I 43.4.6. - 10787, .

- N. N.: Charles Rennie Mackintosh Glasgow, in: Innendekoration, 13. Jg. (1902), S. 133-136.

- Heidi Brunnbauer: Im Cottage von Währing/Döbling .... Interessante Häuser - interessante Menschen, Band 2, Gösing 2006, S. 126-132.