Camera-Club

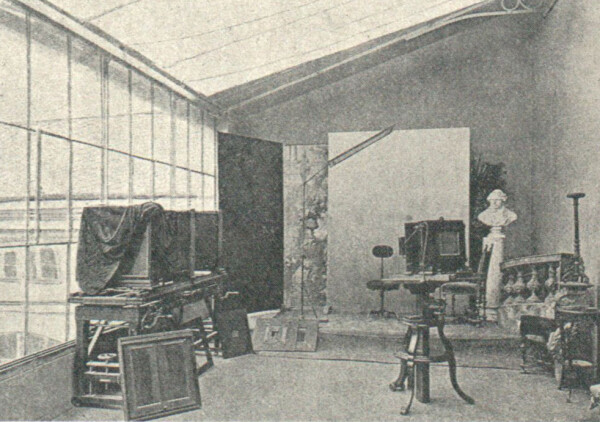

Camera-Club, Clubatelier, in: Wiener Camera-Club (Hg.): Wiener Photographische Blätter, 1. Jg., Nummer 10 (1894).

© ANNO | Austrian National Library

The Club of Amateur Photographers in Vienna (called Camera-Club from 1893 onward) was an association made up of members of the bourgeoisie and the aristocracy who pursued photography as a leisure activity and through their tackling scientific, technical, and aesthetic issues considerably influenced the reorientation of photography.

By the middle of the 19th century, photography was on the upswing throughout Europe, which in 1861 led to the foundation of the Photographic Society in Vienna. This association acted first and foremost as a lobby for photography businesses in the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. Amateur photographers, whom professional photographers often saw as competitors, also wished to organize themselves within said Photographic Society. However, the lack of aesthetic discourse and internal power struggles prompted them to install their own association, which was incorporated on 31 March 1887 as the Club of Amateur Photographers in Vienna. Its goals were the aesthetic renewal of photography, its recognition as an art form, and its technical improvement.

Thanks to the invention of the dry plate collodion process, photography came to be simplified in the late 1870s, and besides being applied in science and art it also became a popular albeit costly leisure activity pursued by the upper classes and the aristocracy. In elite circles there was a growing interest in taking photographs in one’s private surroundings and when traveling, and amateur photography developed into a cherished institutionalized pursuit, comparable to cycling and ice skating clubs.

The members of the Club of Amateur Photographers were scientists, industrialists, and private individuals, most of them cultivated, cosmopolitan, and interested in the art discourse, yet distancing themselves from inexpert “snappers.” Technical specialists and aristocrats were appointed extraordinary honorary members in order to promote networking and exchange. An essential feature of the association, which was also referred to as “Millionaires’ Club,” was its exclusivity: an elaborate admission process and expensive membership fees guaranteed a high degree of selection.

Club Life and Club Magazines

To promote club activities, the association rented a clubhouse boasting a salon, an auditorium, a studio, a darkroom, a photographic collection, and a specialized library. The headquarters were home to weekly club meetings that provided a platform for discussion, lectures, practical experimentation, and slide shows. Moreover, the program comprised excursions and “club corners” for specific interests.

Starting in early 1887, the association published the Photographische Rundschau as its official magazine, the primary purpose of which was to inform members living out of town about club activities. The periodical also contained specialized contributions, translations of articles from international magazines, and elaborate illustrated supplements. From 1894 to 1899 the club published the Wiener Photographische Blätter in a modernized format and layout, which was superseded by the Photographisches Centralblatt in 1899 and the Jahrbuch des Camera-Klubs in Wien in 1905.

In the beginning, the focus was on science, technology, craftsmanship, and experimentation, and as to their pompous presentations the first exhibitions resembled contemporary industrial and trade fairs. Photomicrographs by Hugo Hinterberger and instantaneous photographs by Charles Scolik were among the novelties of the 1890s. In 1893 the association changed its name to Camera-Club and increasingly devoted itself to aesthetic issues, organizing more reduced exhibitions the objects for which were selected by a jury.

Starting in 1896, the gum bichromate process became a major impact on the aesthetic discourse that contributed to the development of Pictorialism: through individual interference, photographers were able to create pictures with a painterly effect, which as unique photographs were opposed to reproducible photographs and elevated amateur photography to “the sphere of art.” Pictorialism’s principal exponents were Hugo Henneberg, Hans Watzek, and Heinrich Kühn – also known as the “Trifolium” – as well as Friedrich Viktor Spitzer. They put photography on an equal footing with the visual arts as a medium and in 1902 presented selected works in the Vienna Secession’s “VIII. Austellung” [“8th Exhibition”].

Henneberg and Spitzer were in close contact with the artists of the Secession and the Wiener Werkstätte through personal friendships and as patrons. They lived in an artists’ colony on Hohe Warte as neighbors of Carl Moll and Kolo Moser. Henneberg and Spitzer had their villas designed by Josef Hoffmann and had a photo studio and darkroom installed in their homes. Their close relationship to the intellectual and artistic elite and to high-society circles has been documented in the diaries of Alma Mahler-Werfel, Carl Moll’s stepdaughter, and numerous portrait photographs of such personalities as Gustav Klimt, Ferdinand Hodler, Gustav Mahler, Jan Toorop, and Emil Zuckerkandl point to their social milieu.

Not only did the members of the Camera-Club publish their progressive photographs and ideas in magazines, they also exhibited their works at such renowned institutions as the H. O. Miethke Gallery, the Hagenbund, the Imperial-Royal Austrian Museum of Art and Industry (now MAK), and even the New York Gallery of the Photo-Secession. The development of photography went hand in hand with that of modern art, and while the two media mutually influenced each other, it was primarily painting that borrowed photography’s pictorial accomplishments.

The foundation of new associations caused a decline in membership as early as the 1890s. Yet by World War I at the latest, the amateur scene’s gradual democratization and profound social changes had set in that would ultimately lead to the Camera-Club’s demise and liquidation in 1937.

Literature and sources

- N. N.: Vereins- und Personal-Nachrichten. Club der Amateure, in: Photographische Correspondenz, 23. Jg., Nummer 308 (1886), S. 303-304.

- N. N.: Amateurclub, in: Photographische Correspondenz, 24. Jg., Nummer 316 (1887), S. 46-47.

- Uwe Schögl: Moriz Nähr and the Vienna Secession. Interrelationship between Photography and Painting, in: PhotoResearcher, Nummer 31 (2019), S. 122-133.

- Astrid Mahler: Liebhaberei der Millionäre. Der Wiener Camera-Club um 1900. Beiträge zur Geschichte der Fotografie in Österreich. Band 18, Vienna 2019.

- V. S.: Wiener Camera-Club, in: Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 4 (1898), S. 25-27.

- Anthony Beaumont (Hg.): Alma Mahler-Werfel. Tagebuch-Suiten. 1898–1902, Frankfurt am Main 1997.

- N. N.: Unser Club, in: Wiener Camera-Club (Hg.): Wiener Photographische Blätter, 1. Jg., Nummer 10 (1894), S. 208-213.