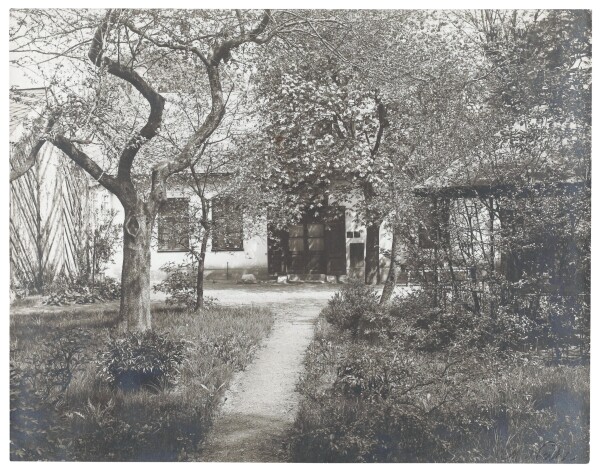

Studio at Feldmühlgasse 11

Moriz Nähr: Garden and exterior view of Gustav Klimt's studio in Feldmühlgasse, May 1917, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

In 1911, Gustav Klimt moved into his studio at Feldmühlgasse 11 (formerly Feldmühlgasse 9). The secluded, rural studio in Vienna-Hietzing, 13th District, was the artist’s last workplace. After Klimt’s death in 1918, numerous paintings remained unfinished on their easels.

After Gustav Klimt’s old studio in Vienna-Josefstadt, 8th District, had been demolished, his friend and fellow artist, Felix Albrecht Harta, helped him to find a small house at Feldmühlgasse 9 (now number 11), in proximity to his own studio (Feldmühlgasse 12). The rooms, including the garden, were photographed in 1917 by Klimt’s friend, the photographer Moriz Nähr. Additionally, there are various reports from Klimt’s friends and contemporaries describing the artist’s last place of activity.

The layout of the new studio was highly similar to that of Klimt’s old workspace on Josefstädter Straße. Nähr’s photographs show a small, single-floor Biedermeier house with a flourishing orchard and flower garden. Egon Schiele reported that Klimt, who had struggled with a lack of daylight at his Josefstadt studio, had two large windows fitted to allow for enough light.

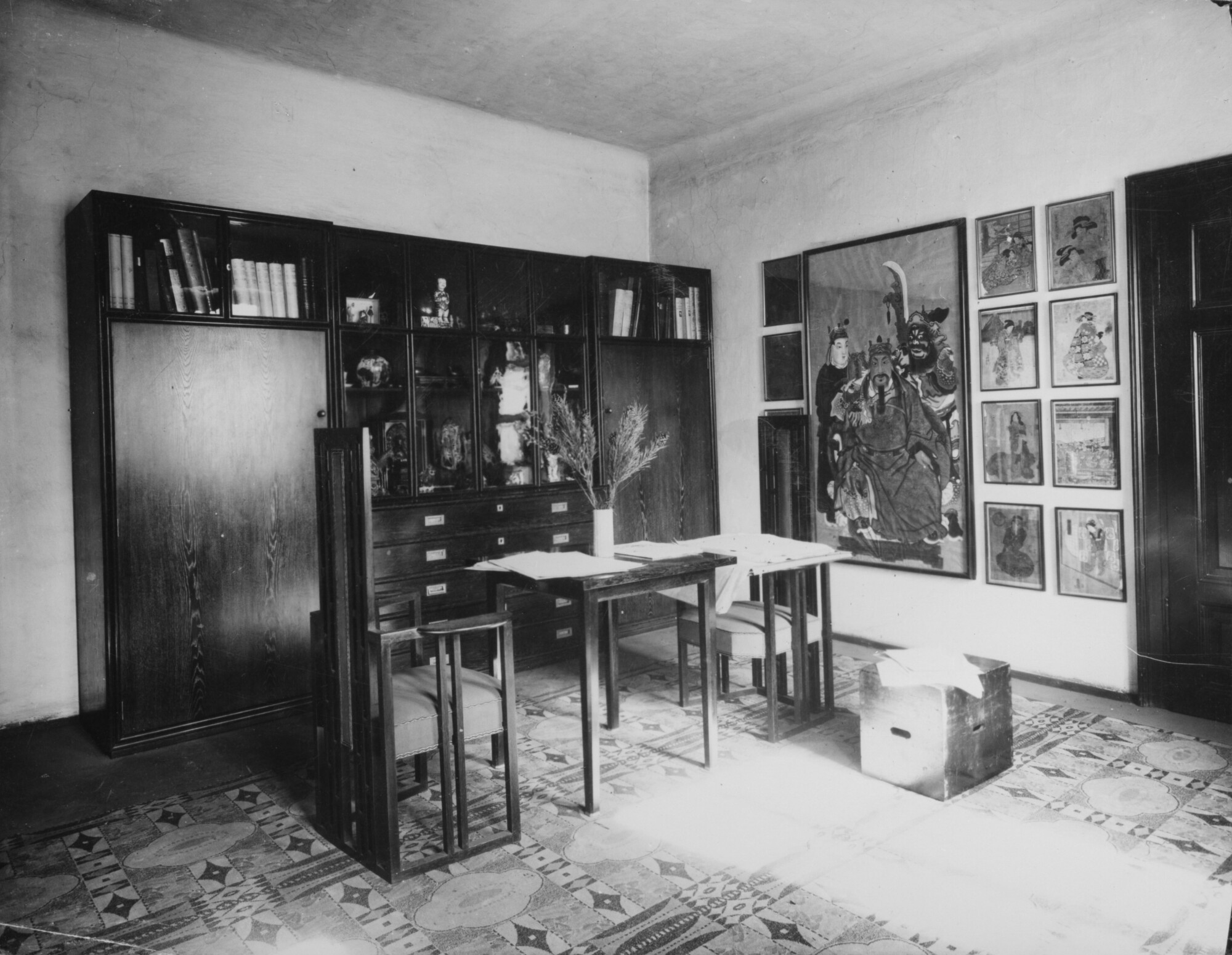

Moriz Nähr: Reception room of Gustav Klimt's studio in Feldmühlgasse, presumably 1917, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Gustav Klimt: Portrait of Friederike Maria Beer, 1916, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, The Mizne-Blumental Collection

© Tel Aviv Museum of Art

The Wiener Werkstätte furnishings, which the artist had been given as a present by Fritz Waerndorfer and Josef Hoffmann (both of whom were founders of the Wiener Werkstätte and close friends with Klimt), were moved to the new address. As opposed to his old workspace on Josefstädter Straße, Klimt now finally permitted Hoffmann to design all the rooms as a cohesive Jugendstil ensemble.

In numerous cupboards, Klimt kept his ethnographical collection, which included Japanese kimonos, Japanese color woodcuts, Chinese paintings, African sculptures and a Japanese suit of armor. From 1912 onwards, Klimt increasingly derived inspiration for the decor of his portraits from these exotic objects. According to Maximilian Eisler, Klimt used motifs from a Chinese vase from the imperial factory in Jingdezhen, in the style of the “green family” (famille verte), for his Portrait of Friederike Maria Beer (1916, Museum of Art, Mizne-Blumenthal Collection, Tel Aviv). In this work, the artist combined the exotic depictions with a Wiener Werkstätte dress, more specifically a model designed by Dagobert Peche by the name of “Marina.” In his late oeuvre, Klimt increasingly included objects, and thus motifs from his ethnographical collection, in his paintings. He focused especially on animal and flower depictions and on human figures from Asian arts-and-crafts objects, with which he decorated the background of his works. Moreover, he now often draped his female figures in exotic garments from his collections. Examples of this are his works Lady with a Fan (1917/18 (unfinished), private collection) and Friends II (1916/1917, destroyed in a fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945).

Klimt not only created numerous paintings at his Feldmühlgasse studio but also countless drawings – most of them for study purposes – which, according to Klimt’s contemporaries, the artist simply let pile up on the studio floor.

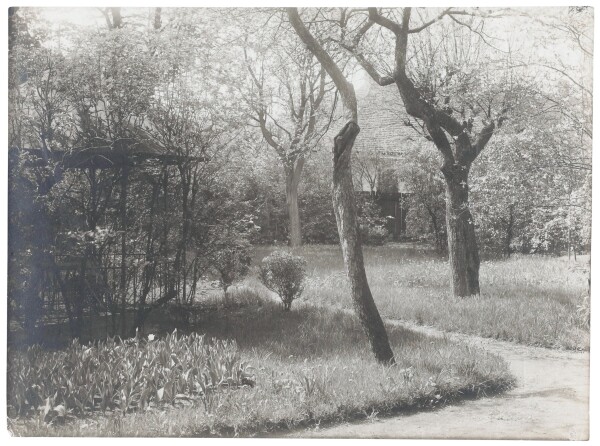

Moriz Nähr: Garden and pavilion of Gustav Klimt's studio in Feldmühlgasse, May 1917, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Gustav Klimt: Orchard with Roses, 1912, private collection

© Bridgeman Images

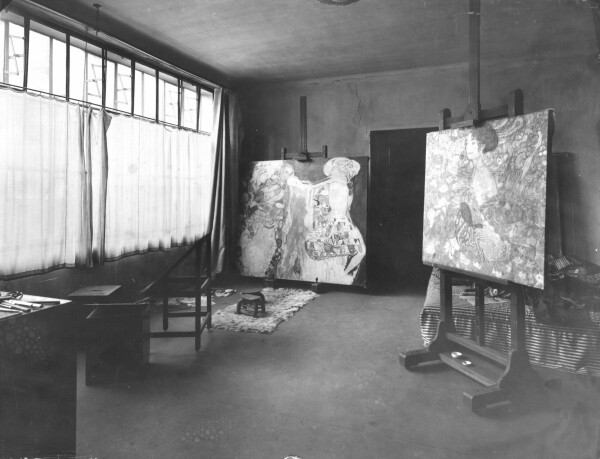

Moriz Nähr: Gustav Klimt's workshop in Feldmühlgasse, presumably 1917, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

The Garden as a Haven

“A stunning day in my garden pavilion – wonderfully fragrant air – a nice spot – feeling as though I was in the countryside,” Klimt wrote in 1912 in a postcard to Emilie Flöge.

All his life, nature had provided a haven for the artist, from which he could draw strength and inspiration. While the studio’s interior was pragmatic and often untidy, Klimt nourished and cherished the lush garden featuring roses, flowers, fruit trees and shrubs. Nature and gardens generally held a special significance in art around 1900. All the important exhibitions of the fin-de-siècle – including the “Kunstschau Wien” organized by Klimt in 1908 – featured a separate garden department. For his construction project for an artists’ colony on Hohe Warte, Josef Hoffmann focused not just on the buildings but also on the planning of the gardens. Like Klimt, numerous eminent artists of the time, including Claude Monet and Max Liebermann, had their own gardens, which often served them as the subject of their works. Klimt, too, used his garden as a motif for his paintings. It has often been suggested that his rendering Orchard with Roses (1912, private collection) affords an insight into Klimt’s studio garden. If we compare Moriz Nähr’s photographs of the garden with the composition in Orchard with Roses, it really does seem likely that he painted the same rose bushes under (in the photo still bare) fruit trees and the same forked path. Klimt usually found his landscape motifs during his summer sojourns on the Attersee. Thus, this painting would be the only work to show Klimt’s private garden.

Gustav Klimt’s Final Years

Klimt increasingly withdrew from the public during the final years of his life, and enjoyed the seclusion of his personal “hortus conclusus” in Vienna’s suburb. This ideal synergy of artistic focus and meditative solitude at his Feldmühlgasse studio yielded allegorical key works, such as Death and Life (Death and Love) (1910/11, reworked: 1912/13 and 1916/17, Leopold Museum, Vienna) and The Virgin (1913, Národní Gallerie, Prague).

In January 1918, Klimt suffered a stroke. He was first taken to a sanatorium and subsequently admitted to Vienna’s General Hospital. Schiele reported in a letter that shortly after Klimt’s hospitalization, the Feldmühlgasse studio was broken into, though it is unclear whether something was taken. The painting The Bride (1917/18, unfinished, Klimt-Foundation, Vienna) is one of the last renderings that Klimt worked on in his studio. As a 1917 photograph by Moriz Nähr shows, it remained unfinished on the easel.

After Klimt’s death, Egon Schiele tried to take over the Feldmühlgasse studio to preserve it for posterity. Unfortunately, he, too, died that same year. Emilie Flöge, who took over the rental agreement for the Feldmühlgasse studio, terminated the contract in May 1919. In 1923, a neo-baroque villa was built over the small Biedermeier house, though the basic layout of Klimt’s studio rooms was preserved. In 1930, the plot was divided into Feldmühlgasse numbers 9 and 11. The villa, and thus the former studio, were now located at number 11. In 2012, the workshop rooms within the building were returned to their original state as far as possible. Known as the “Klimt-Villa,” the house has since been made accessible to the public.

Literature and sources

- Christian M. Nebehay (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Dokumentation, Vienna 1969.

- Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl, Felizitas Schreier, Georg Becker (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Atelier Feldmühlgasse 1911–1918, Vienna 2014.

- Mona Horncastle, Alfred Weidinger: Gustav Klimt. Die Biografie, Vienna 2018.

- Sandra Tretter, Peter Weinhäupl: Gustav Klimt und sein »Werkstattgarten«, in: Irmi Soravia (Hg.): Hietzing, Vienna 2019, S. 135-146.

- Ernst Ploil: Die Ateliers des Gustav Klimt, in: Tobias G. Natter, Franz Smola, Peter Weinhäupl (Hg.): Klimt persönlich. Bilder – Briefe – Einblicke, Ausst.-Kat., Leopold Museum (Vienna), 24.02.2012–27.08.2012, Vienna 2012, S. 98-107.

- Verena Traeger: Gustav Klimts ethnografische Sammlung, in: Sandra Tretter, Hans-Peter Wipplinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Jahrhundertkünstler, Ausst.-Kat., Leopold Museum (Vienna), 22.06.2018–04.11.2018, Vienna 2018.

- Ansichtskarte von Gustav Klimt in Wien an Emilie Flöge in Bad Gastein (23.06.1912). RL 2857, .

- Brief von Egon Schiele an Anton Peschka (30.01.1918). S249.

- Max Eisler: Gustav Klimt, Vienna 1920, S. 46.

- Tobias G. Natter (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Sämtliche Gemälde, Vienna 2017, S. 573, S. 576.