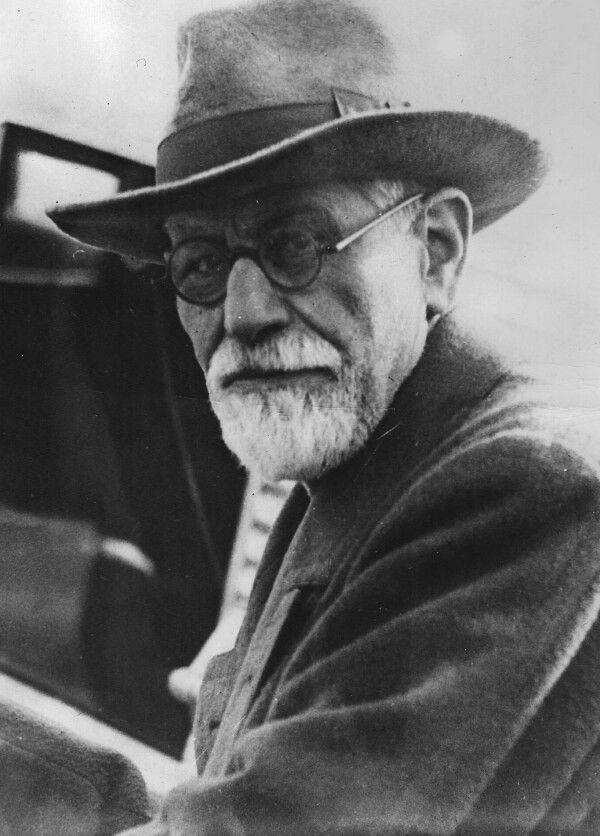

Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud photographed by Albert Hilscher, around 1930, Austrian National Library, Vienna

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Former waiting room of Sigmund Freud's surgery, today: Sigmund Freud Museum photographed by Otto Simoner, 1979, Austrian National Library, Vienna

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Sigmund Freud is considered the father of psychoanalysis and one of the most influential thinkers of the twentieth century. Initially met with a hostile response, he ultimately achieved international fame. The discourse on his theories and the application of his methods continues to this day.

Sigmund Freud, originally named Sigismund Schlomo, came from a Jewish family. He was born in Freiberg (now Přibor) in Moravia on 6 May 1856 as one of seven children, son of the textile merchant Jakob Freud and Amalia Freud, née Nathanson. As religion played no role in the family, Freud considered himself an atheist throughout his life.

In 1860 the family moved to Vienna, where he studied medicine at the university from 1873 to 1881. While working at the General Hospital and specializing in neurology, he was involved in the discovery of the analgesic effect of cocaine and also carried out experiments on himself. As part of his research into the nervous system, he habilitated as a university lecturer in neuropathology in 1885. With the aid of a scholarship he was able to study for a year with Jean-Martin Charcot, a luminary in the field of neurology, in Paris and Berlin in 1885/86. In 1886, Freud married Martha Bernays, with whom he had six children. Their youngest daughter, Anna, would follow in her father’s footsteps. In her British exile she became famous for her psychoanalytic pedagogy and child analysis. Sigmund Freud then worked as a general practitioner in Vienna and published relevant literature.

Freud’s Psychoanalysis

The phenomenon of “hysteria” had already aroused Freud’s interest at an early stage. In 1889 he deepened his hypnotic technique with Liébault and Bernheim in Nancy and began an intensive collaboration with the internist Josef Breuer. The latter had come up with the theory that unprocessed dreams led to physical symptoms. Hysteria was therefore an expression of a psychological trauma that had not been digested. With the help of hypnosis it would be possible to eliminate the symptoms by reproducing the experience, so that the misdirected affect could be reacted to in a normal way. Breuer called this the “cathartic method.”

Freud, however, broke away from this theory and replaced hypnosis with free association, the analysis of Freudian slips, and the interpretation of dream content. He thus developed his own method and gave it the name psychoanalysis. Examining the development of neuroses, he also looked into the mental life of healthy people, deriving depth psychology from his research.

In 1900 he published The Interpretation of Dreams, in which he used his own dreams and the stories of patients to open up the realm of the unconscious to his empirical research method. He did not distinguish between the dreams of healthy and of mentally ill people. This fact in particular provoked resistance, with Freud pointing out that a mental illness did not necessarily have physical causes, but could also be the expression of a psychological injury, such as neurosis. Experts dismissed his theories as fantastic and bizarre. In artistic circles, however, his psychological treatises found many admirers.

Freud became an associate professor in 1902 and accepted an invitation to the USA in 1909, where he gave guest lectures at the University of Worcester, thus making his theories known internationally.

Freud and Fin-de-Siècle Art

Dreams and their interpretation were a popular leitmotif in literature around 1900. The authors of Jung-Wien [Young Vienna], including Arthur Schnitzler and Felix Salten, were inspired by psychoanalysis. Dreams and the psyche also played an increasingly important role in the visual arts, which found a suitable breeding ground in the Symbolist style.

To date there is no evidence of a personal contact between Gustav Klimt and Sigmund Freud. However, according to Erich Lederer, the son of one of the families who actively supported Klimt, Klimt “joked” about the contents of psychoanalysis. What is certain, however, is that Klimt was aware of Freud’s theories and had probably studied them in detail. The problems of the unconscious and sexuality – especially female sexuality – were also a recurring theme in Klimt‘s works. Freud‘s focus on the life of the soul, the world of instinct, and the elimination of sexual taboos opened up a new liberal attitude for Klimt and many other artists.

Interwar Years and Political Persecution

After the caesura caused by World War I, Freud became a full professor at the University of Vienna in 1919. To this day, his most important works include Totem and Taboo (1913), The Ego and the Id (1923), and Civilization and Its Discontents (1930). After initial resistance, a group of followers soon gathered around Freud, consisting of Alfred Adler, Wilhelm Stekel, Otto Rank, Hanns Sachs, Theodor Reik, and many others.

After the invasion of Austria by German troops in 1938, Freud and his family were directly threatened. Not only his Jewish ancestry but also his controversial theories made him an enemy of the Nazi regime. Thanks to his international fame he managed to escape into exile in London, where Freud was celebrated for his achievements. He died in London on 23 September 1939, having suffered from cancer of the palate for many years.

Literature and sources

- Österreichisches Biographisches Lexikon. Sigmund Freud. www.biographien.ac.at/oebl/oebl_F/Freud_Sigmund_1856_1939.xml (03/26/2020).

- Wien Geschichte Wiki. Sigmund Freud. www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Sigmund_Freud (03/26/2020).

- Josef Rattner: Klassiker der Psychoanalyse, Wienheim - Basel 1995, S. 3-27.

- Sandra Tretter, Hans-Peter Wipplinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Jahrhundertkünstler, Ausst.-Kat., Leopold Museum (Vienna), 22.06.2018–04.11.2018, Vienna 2018.

- Alice Strobl (Hg.): Gustav Klimt. Die Zeichnungen, Band III, 1912–1918, Salzburg 1984, S. 212.

- Stefan Zweig: Worte am Sarge Sigmund Freuds, Amsterdam 1939.

- Steven Beller: Freud, Vienna and the Historiography of Madness, in: Jouneys into Madness. Mapping Mental Illness in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, New York 2012.