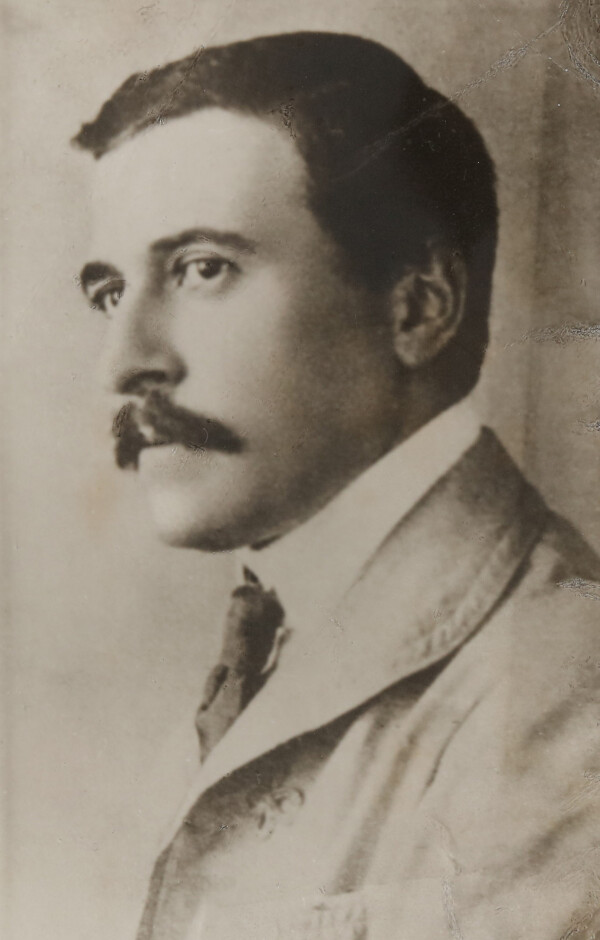

Hugo von Hofmannsthal

Hugo von Hofmannsthal, 1907

© Freies Deutsches Hochstift / Frankfurter Goethe-Museum

Otto Brahm, Felix Salten, Arthur Schnitzler and Hugo von Hofmannsthal at Semmering around 1907

© Freies Deutsches Hochstift / Frankfurter Goethe-Museum

The poet and playwright Hugo von Hofmannsthal is one of the most important Austrian authors of the modern age. His play Jedermann, which is still the heart of the Salzburg Festival today, achieved world fame.

Hugo von Hofmannsthal was born in Vienna, the son of bank director Dr. Hugo von Hofmannsthal and his wife Anna, née Fohleutner. Initially taught by private tutors, Hugo von Hofmannsthal then switched to the highly recognized Akademisches Gymnasium, where he graduated in 1892.

After a trip to the south of France, he studied law, Romance languages, and French philology at the University of Vienna. In 1899 he earned a doctorate in Romance studies and began work on a habilitation thesis about the development of Victor Hugo, yet decided to become a freelance writer instead.

Friends and Acquaintances – Viennese Salons and the Café Griensteidl

Hofmannsthal frequented the Café Griensteidl while he was still at school. There he became acquainted with a circle of young writers who referred to themselves as “Jung-Wien” [“Young Vienna”]. This group of writer-friends included Arthur Schnitzler, Hermann Bahr, Richard Beer-Hofmann, Theodor Herzl, Leopold von Adrian, Stefan George, Felix Salten, and Karl Kraus. Hofmannsthal also became a member of Jung-Wien. He was particularly close to Schnitzler and Bahr, who recognized his talent early on.

During his student days he frequented the numerous Viennese salons, such as those of the Tedesco and Wertheimstein families, where he met numerous well-known writers, musicians, and artists.

The young writer was also a guest at Berta Zuckerkandl’s salon. Not only were the members of Jung-Wien regularly invited there, but also young visual artists, including Gustav Klimt. Hofmannsthal’s friends from this circle of acquaintances included Alma Mahler-Werfel, the dancer Grete Wiesenthal, and the opera singer Selma Kurz.

After trips to Northern Italy and Paris, Hofmannsthal married Gertrud Schlesinger, the younger sister of his childhood friend, the painter Hans Schlesinger, on 8 June 1901. Together they moved into a small Baroque palace in Rodaun, where Hofmannsthal lived until his death. They had three children, Christiane, Franz, and Raimund. The couple led a busy cultural and social life and regularly received literary and artistic friends at their home.

Residence of Hugo von Hofmannsthal in Rodaun

© Freies Deutsches Hochstift / Frankfurter Goethe-Museum

Gerty von Hofmannsthal with her children, from left to right: Franz, Raimund and Christiane, 1907

© Freies Deutsches Hochstift / Frankfurter Goethe-Museum

Hugo von Hofmannsthal at the opening of the Claude Monet exhibition in Weimar on April 20, 1905

© Freies Deutsches Hochstift / Frankfurter Goethe-Museum

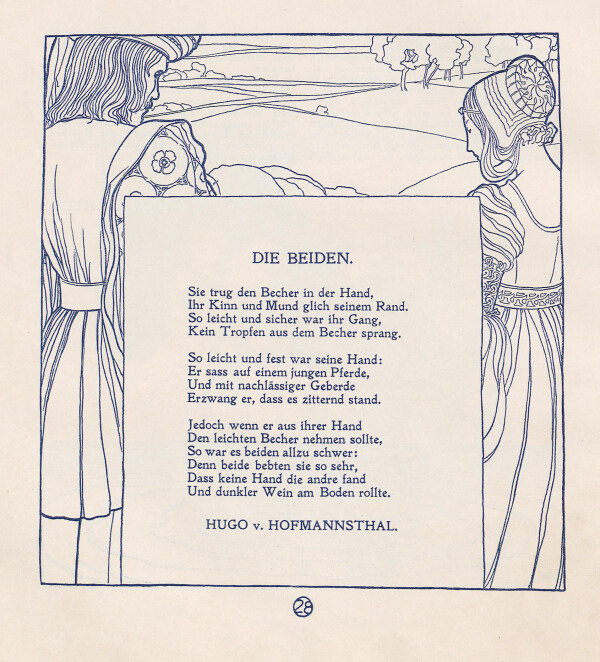

Hugo von Hoffmannsthal: The Two, illustrated by Friedrich König, in: Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Zeitschrift der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 2. Jg., Heft 2 (1899).

© Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Sign. 83 A 2267, Einband

Hugo von Hofmannsthal in his salon in Rodaun. In the background Gerty von Hofmannsthal, 1906

© Freies Deutsches Hochstift / Frankfurter Goethe-Museum

Grete von Hofmannsthal and Lilly Berger in Hugo von Hofmannsthal's Armor and Psyche, 1911

© Freies Deutsches Hochstift / Frankfurter Goethe-Museum

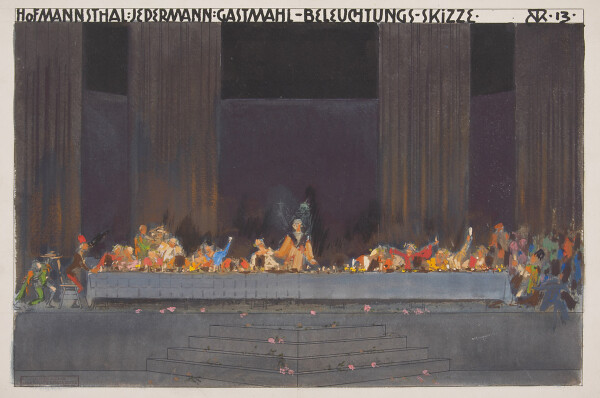

Alfred Roller: Stage design for "Jedermann" by Hugo von Hofmannsthal, banquet scene, 1913, Theatermuseum, Vienna

© KHM-Museumsverband

The Visual Arts, Ver Sacrum, and Klimt

Hofmannsthal’s interests also embraced the visual arts. He actively followed current exhibitions. As he collected art himself, he visited the sales exhibitions at Galerie Miethke, among others. His collection comprised works by Anton Faistauer and a painting by Vincent van Gogh. In 1905 he was present at the opening of the Claude Monet exhibition in Weimar. An art lover, he also took part in several so-called “tableaux vivants.”

Hofmannsthal was also a frequent guest at the Secession to see the current exhibitions, which he sometimes visited more than once. Hermann Bahr in particular facilitated a lively exchange between the writers of Jung-Wien and the Secession artists, whom Bahr supported with his positive reviews. This collaboration became particularly evident in the Secession’s magazine Ver Sacrum, in which both groups were represented side by side through texts and images.

Hofmannsthal contributed to the magazine’s first and second years. The two poems Weltgeheimnis [“The World’s Secret”] and Die Beiden [“The Two of Them”] were illustrated by Fernand Khnopff and Friedrich König. Both contributions had probably been recommended to the editors of Ver Sacrum by Hermann Bahr in March 1898:

“Find enclosed several poems by Hofmannsthal, which I liked.”

Hofmannsthal’s active involvement with the Secession and Gustav Klimt also becomes evident in a postcard in which he tells Hermann Bahr about his visit to a Secession exhibition and in which he even expresses the wish that Klimt should illustrate his poems:

“My dear Bahr, I was at the Secession yesterday and will of course go there more often. I also liked the things by Klimt in the issue of Ver sacrum [!] very much, and I would now really appreciate his illustrating my poems.”

However, the collaboration with Klimt did not come to fruition. A handwritten message suggests that Klimt did not appreciate Hofmannsthal’s work as much as Hofmannsthal appreciated the artist’s work. In his satirical article in Illustriertes Wiener Extrablatt, Julius Bauer ironically suggested that Klimt’s painting Philosophy (1900–1907, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle) would be easier to understand if it were accompanied by an explanatory poem by Hofmannsthal. Klimt’s response in the words of one of the Secession artists was as follows:

“I do not consider myself a philosopher by all means. But that I am associated with Hofmannsthal – this has offended me deeply.”

As these words, presumably written by Alfred Roller, were intended as a reply to the above-mentioned parody, it is not possible to say with certainty how seriously they were meant and to what extent they reflected Klimt’s actual opinion. What is certain, however, is that Klimt and Hofmannsthal did not collaborate in Ver Sacrum.

Private correspondence shows that Hofmannsthal continued to be interested in Klimt’s art despite their collaboration had failed. For example, he discussed the scandal surrounding the Faculty Paintings and the execution of the Beethoven Frieze (1901/02, Secession, Vienna) with his brother-in-law, Hans Schlesinger.

The Theater and Roller

Like the artists of the Secession, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, with his modern works freed from taboos, caused offence in a predominantly conservative society. Nevertheless, he was able to work successfully as a freelance writer until the outbreak of World War I. His work now also came to include works for the stage. For the latter, he closely collaborated with the composer Richard Strauss, for whose operas Hofmannsthal wrote several libretti. They include Elektra (1904), Der Rosenkavalier [The Rose Bearer] (1911), Ariadne auf Naxos [Ariadne on Naxos] (1912), and Die Frau ohne Schatten [The Woman without a Shadow] (1919).

Once again, Hofmannsthal sought to collaborate with Klimt. He tried to win him over for the set designs of his plays. As Klimt generally did not take on stage productions, another artist had to be entrusted with the project. In 1905, Arthur Kahane of the Deutsches Theater in Berlin therefore wrote to Hofmannsthal:

“Klimt has declined as directly and bluntly as possible. He would have been my absolute favorite by far, but I consider it a completely hopeless case. On the other hand, Roller gave the impression of the greatest likelihood.”

The Secessionist Alfred Roller, a good friend of Klimt’s, had increasingly accepted work for theater productions in the course of his career. Roller also designed numerous concepts for Hofmannsthal’s plays, most of which ranged from stage sets to costume designs.

Hofmannsthal repeatedly engaged famous dancers, such as the Wiesenthal sisters and Lilly Berger, for his works. For example, Grete Wiesenthal and Lilly Berger danced in Hofmannsthal’s Amor und Psyche [Cupid and Psyche] in 1911. A friendly relationship developed with Grete Wiesenthal in particular.

After World War I, Hofmannsthal was a frequent guest at Andy von Szolnay’s salon at Oberufer Castle near Bratislava, which was also frequented by Gerhart Hauptmann, Richard Strauss, Franz Werfel, and Carl Moll. This network of acquaintances resulted in new projects for the writer. He established the Salzburg Festival in a dialog with Berta Zuckerkandl, Max Reinhardt, Richard Strauss, and the Viennese opera director Franz Schalk. Hoffmannsthal’s mystery play Jedermann [Everyman] (1911), especially written for the festival, was first performed in 1920 in a production by Max Reinhardt on Salzburg’s Domplatz; it has remained the heart of the festival to this day. Here, too, he worked closely with Alfred Roller, who provided the entire artistic concept.

Hofmannsthal's enthusiasm for Klimt would last until his death. When the painter died in 1918, Hofmannsthal wrote an emotional letter to Alfred Roller in which he mourned the loss of the great artist:

“The paper with the news of Klimt’s death arrived at the same time as your letter. What should one say to this?”

Hugo von Hofmannsthal died on 15 July 1929.

Literature and sources

- Hugo von Hofmannsthal Gesellschaft. Biografie. hofmannsthal.de/ (04/03/2020).

- Literaturmuseum. Hugo von Hofmannsthal. www.literaturmuseum.at/Literaten/Hofmannsthal.html (04/03/2020).

- Wien Geschichte Wiki. Hugo von Hofmannsthal. www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Hugo_von_Hofmannsthal (04/03/2020).

- Österreichisches Biographisches Lexikon. Hugo von Hofmannsthal. www.biographien.ac.at/oebl/oebl_H/Hofmann-Hofmannsthal_Hugo_1874_1929.xml (04/03/2020).

- Hugo von Hofmannsthal: Der Dichter und diese Zeit – Ein Vortrag, in: Gesammelte Werke, Reden und Aufsätze, Band 1, Frankfurt am Main 1979, S. 54.

- Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 1. Jg., Heft 12 (1898), S. 5.

- Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Zeitschrift der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 2. Jg., Heft 2 (1899), S. 28.

- Brief von Hugo von Hofmannsthal an Hermann Bahr (undated). HS AM37228Ba.

- Brief von Hermann Bahr an die Redaktion des Ver Sacrum (03/11/1898). 2.5.9.765, .

- Korrespondenzkarte von Gustav Klimt, verfasst in fremder Hand, an die Redaktion des Illustrierten Wiener Extrablattes (04/02/1900). Autogr. 580/5-1.

- Brief von Hans Schlesinger in Paris an Hugo Hofmannsthal (03/25/1901). HS-31019,40.

- Brief von Hans Schlesinger in Paris an Hugo Hofmannsthal (04/10/1901). HS-31019,41.

- Julius Bauer: Das Bild von Klimt, in: Illustrirtes Wiener Extrablatt, 01.04.1900, S. 4.