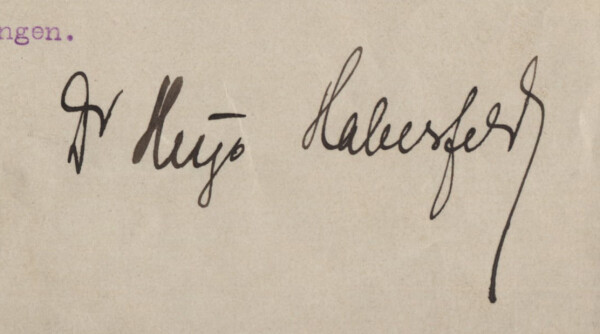

Hugo Haberfeld

Gustav Klimt: Letter of indemnity written by Gustav Klimt in Vienna, co-signed by Carl Moll and Hugo Haberfeld, 12/16/1907, Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Handschriftensammlung, Estate of Hans Ankwicz-Kleehoven

© Vienna City Library, Manuscript collection

An art expert who worked as an assistant at Galerie Miethke and was further active as a journalist and art writer, Hugo Haberfeld made a name for himself in Vienna around 1900. Owing to his activities in the art trade, his circle of acquaintances included numerous contemporary artists, among them Gustav Klimt, Carl Moll and Adolf Loos.

Hugo Haberfeld was born on 24 November 1875 in Auschwitz, Poland, the son of a Jewish industrialist. He spent his childhood in the crown land Galicia. After attending high school in Bielitz (now: Bielsko-Biala, Poland), he studied at the universities of Vienna and Berlin, first law and later philosophy. He subsequently studied art history, archeology, history and philosophy in Breslau.

Following his studies, Haberfeld initially worked as a journalist in the field of art and culture, writing exhibition reviews for the art journals Kunst und Künstler and Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration. His focus was on Viennese exhibitions and on monographic articles about individual artists. After moving to the imperial capital Vienna, he worked as editor for the newspaper Die Zeit and as a freelance journalist for the Wiener Zeitung.

In his articles, Haberfeld often wrote about the exhibitions of the Vienna Secession and those held at Galerie Miethke. In 1902/03, he published a favorable review of the 17th Exhibition of the Secession in Kunst und Künstler: “It is with gladness that we discern how the level of artistry has increased once again.” The more traditional Künstlerhaus, by contrast, did not come off nearly as well: “The Künstlerhaus is degenerating more and more into a mere outlet.”

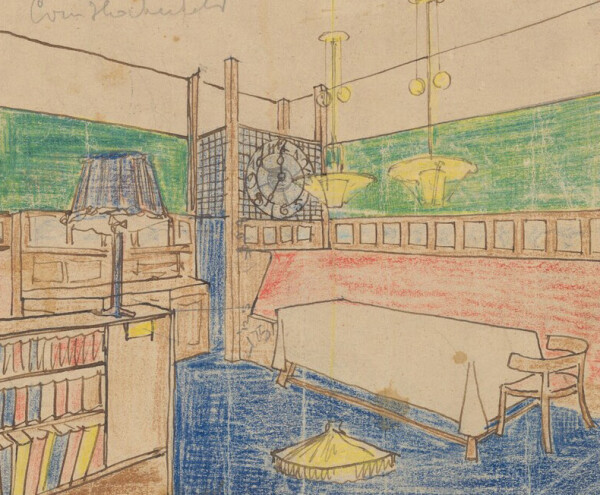

Adolf Loos: Design for Hugo Haberfeld's dining room, 1902

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

Dining room in the apartment of Hugo Haberfeld, designed by Adolf Loos, 1903, in: Das Interieur. Wiener Monatshefte für angewandte Kunst, 4. Jg. (1903).

© Heidelberg University Library

Living room in the apartment of Hugo Haberfeld, designed by Adolf Loos, 1903, in: Das Interieur. Wiener Monatshefte für angewandte Kunst, Jg. 4 (1903).

© Heidelberg University Library

In 1903, Haberfeld had his apartment at Alserstraße 53 decorated by the architect Adolf Loos, who, while not a member of the Secession, was an exponent of modern art.

It was likely this positive attitude towards the Secession and modern art that brought Haberfeld into contact with the circles surrounding Carl Moll and Galerie Miethke. Latest from 1904, the art historian wrote introductory texts for the gallery’s catalogues. In 1906, he issued a complimentary review of a collective exhibition shown at Miethke’s, featuring the artists Thomas Theodor Heine and Nikolai Konstantinovich:

“Just in the nick of time, Galerie Miethke knows how to capture the imagination of art enthusiasts.”

In 1905, a group of artists surrounding Klimt left the Secession, not least on account of Moll’s work for Galerie Miethke and the Klimt-Group’s wish to hold sales exhibitions there. It is worth noting that Haberfeld’s hitherto positive reviews of the Secession exhibitions changed from this point onwards. In 1906, he published an extensive article in the journal Kunst und Kultur on Religious Art in the Secession and the association’s spring exhibition. While his reviews had been consistently positive up until the exit of the artists surrounding Klimt, this essay now had a skeptical, negative undertone. Haberfeld’s loyalty towards the Klimt-Group and its main representative, the Galerie Miethke, clearly comes across in his critical assessment:

“The Secession’s spring exhibition marks yet another step backwards for this association [...] such a climax is certainly undeserving of the valiant and proud struggle fought by the Secession for the past eight years [...]. Prior to the fateful schism, the Secession aspired to turn the necessary evil of exhibitions into a medium promoting the development of artists and the education of audiences. Nothing is palpable of this today.”

It is hardly surprising that Haberfeld, who had been writing texts for Galerie Miethke for years and openly advocated its exhibition policy, became the official director of the gallery in 1907, managing it jointly with Carl Moll. Together, they organized exceptional, modern exhibitions of the highest quality, which were greatly esteemed in Viennese circles. The author Ludwig Hevesi, for instance, wrote:

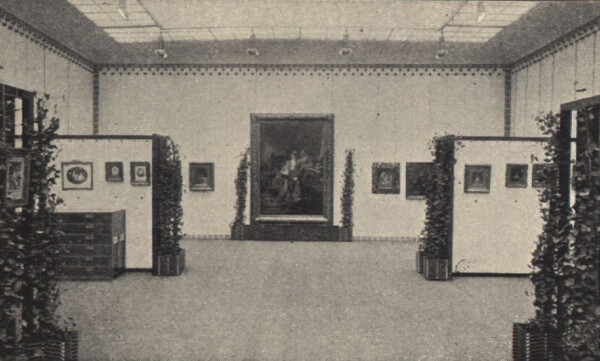

Insight into the exhibition room of Galerie H. O. Miethke on the ground floor, Dorotheergasse 11, 1906, in: Galerie H. O. Miethke (Hg.): Old and modern pictures. Tableaux anciens et modernes, Ausst.-Kat., Gallery H. O. Miethke (Vienna), 00.07.1906–00.00.1906, Vienna 1906.

© Library of the Belvedere, Vienna

Insight into the gallery H. O. Miethke at Graben 17, 1905, in: Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, Band 18 (1906).

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

“The mission of guiding audiences along the paths of Modernism has now well and truly been taken over by Galerie Miethke. The restless energy of Karl [!] Moll promotes a high artistic level, and in the Muthesius student Dr. Haberfeld he has found an excellent assistant. In these rooms, you primarily encounter what is bold, powerful, new and highly controversial, that which will only be recognized tomorrow.”

Haberfeld and Moll had succeeded in making the gallery one of the most renowned art dealerships in Central Europe. In 1911, the first solo exhibition dedicated to the work of Egon Schiele was held there. An important factor for the gallery’s international reputation were the continuous presentations of the art of French Modernism, featuring artists like Manet, Monet, Cézanne, van Gogh, Gauguin and Toulouse-Lautrec. Additionally, photographs and works from the Wiener Werkstätte were an integral part of the gallery’s modern exhibition program.

Throughout his activities as an art dealer, Haberfeld kept working as a journalist. He authored several monographic essays on modern artists surrounding Klimt, including Ferdinand Hodler, Franz Metzner and Adolf Loos. Moreover, he delivered scientific, art historical lectures more and more frequently.

Though the gallery experienced an enormous upswing under Moll and Haberfeld, the two art dealers eventually fell out, likely on account of personal differences. Moll left the gallery in 1912. Klimt commented on this in a picture postcard to Emilie Flöge, writing: “Moll has been fired,” which suggests that Moll did not leave entirely of his own accord. Haberfeld now managed the art salon by himself. In 1917, Emma Teschner, who had owned the gallery up until then, also withdrew from the business, making Haberfeld the sole proprietor.

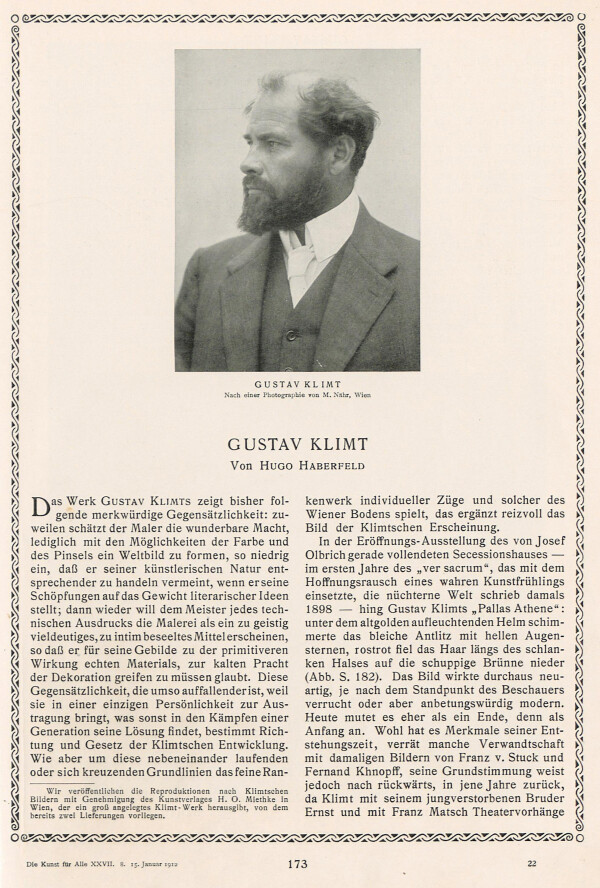

Hugo Haberfeld: Gustav Klimt, in: Die Kunst für Alle. Malerei, Plastik, Graphik, Architektur, 27. Jg. (1911/12), S. 177-183.

© Heidelberg University Library

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

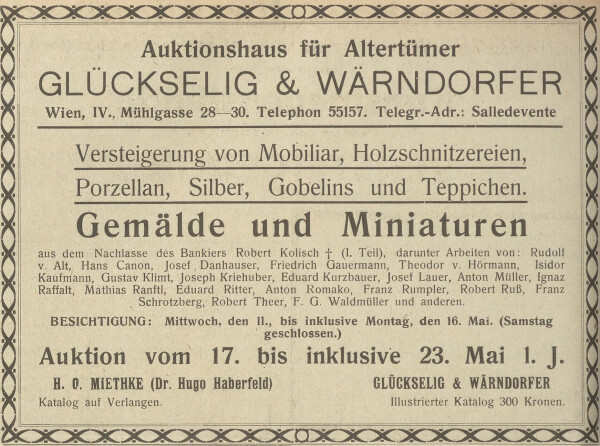

Advertising for an auction by the auction house Glückseling & Wärndorfer, in: Internationale Sammlerzeitung. Zentralbl. für Sammler, Liebhaber u. Kunstfreunde, 13. Jg., Nummer 19 (1921).

© ANNO | Austrian National Library

Haberfeld and Gustav Klimt

As early as 1904, Haberfeld had commented favorably on Klimt in an article on the artist’s work within the Secession. In it, he wrote about observing his evolution from his early oeuvre to his Symbolist period, which started to emerge in 1904. Haberfeld further mentioned all the role models who had shaped Klimt’s stylistic development during this time, including Toorop, Khnopff, Beardsley, Rodin and Minne, as well as Byzantine art. As opposed to contemporary critics like Bahr or Servaes, he did not see Klimt’s works as self-contained, virtuosic and philosophical units but, in keeping with his education as an art historian, embedded them in the context of the art world around 1900.

As the director of Galerie Miethke, Haberfeld was mainly responsible for Klimt’s oeuvre from 1907. On behalf of the gallery, Haberfeld processed sales of artworks and secured loans for Austrian and international exhibitions. Already the year he was named director in December 1907, Haberfeld signed an agreement on the final sale of Klimt’s work The Beethoven Frieze. When Hoffmann asked Klimt for loans of his works for the “XI. Internationale Kunstausstellung im Königlichen Glaspalast zu München 1913” [“11th International Art Exhibition at the Royal Glass Palace in Munich 1913”], Klimt informed him:

“I am happy to accommodate your wish and place a painting at your disposal for the intended purpose, but I have to ask if they agree with this at Miethke’s, as they have the sole publishing rights. I will write to Dr. Haberfeld about it.”

Following Moll’s withdrawal from the gallery in 1912, Haberfeld gave a talk on Klimt at the Vienna Urania Theater, which attracted a lot of attention. Additionally, he published an extensive article on the artist’s work in the periodical Die Kunst für Alle. In the portfolio Das Werk von Gustav Klimt [The Oeuvre of Gustav Klimt], published by Galerie Miethke, the article appeared with rich illustrations. The rights to these reproductions belonged exclusively to Galerie Miethke and thus indirectly to Hugo Haberfeld. Featuring more than 14 large-format black-and-white clichés and a color reproduction of Judith I (1902, Belvedere, Vienna), the article was one of the most extensively illustrated newspaper reports on Klimt. Moreover, it is still one of the most important sources on the colors of the Faculty Paintings to this day. It was certainly in Haberfeld’s interest to promote his client, to increase his renown and with it also his market value.

Art Auctions and the End of Galerie Miethke

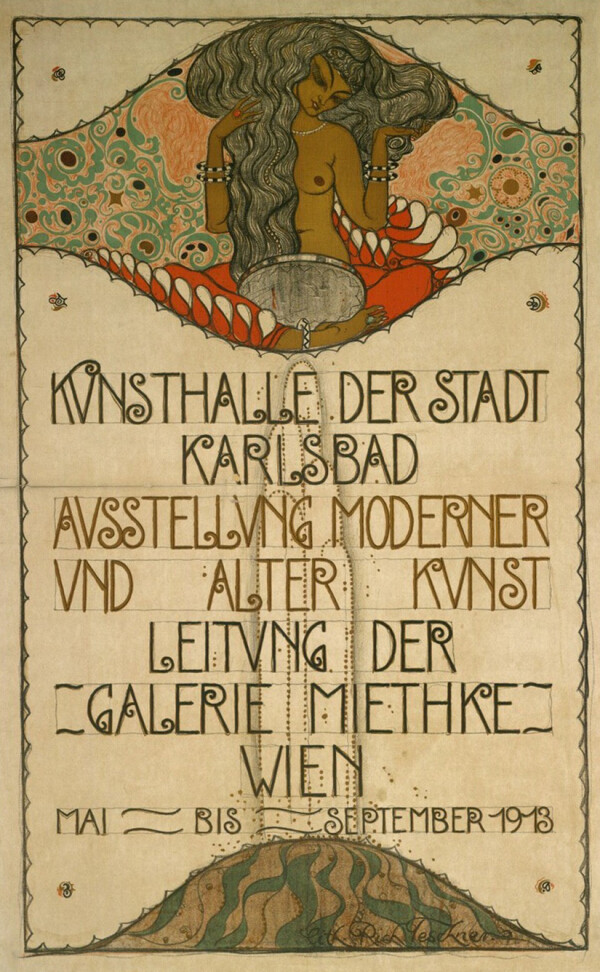

In 1913, Haberfeld opened a branch of the gallery in the newly built Kunsthalle Karlsbad. Under the artistic direction of Galerie Miethke, this second location showcased artists like Goya, Titian, Cranach, Füger and Waldmüller, alongside French Impressionists as well as modern Austrian artists, among them Jettel, Alt, Andri, Laske, Barwig and Klimt.

From the 1920s onwards, Haberfeld increasingly focused on auctions. In his capacity as an esteemed and renowned art expert, he often acted as an appraiser, and helped organize auction exhibitions. Haberfeld primarily collaborated with the auctioneers Albert Kende, J. Fischer as well as Glückselig und Wärndorfer.

Haberfeld and his wife Paula, née Köberl, were forced to flee the National Socialist regime with their daughter Marianne in 1938, and went to Paris. This prompted the dissolution of Galerie Miethke in 1940. The company’s archive has been lost ever since.

Haberfeld died on 6 February 1946 in London.

Literature and sources

- Wien Geschichte Wiki. Galerie Miethke. www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Galerie_Miethke (04/21/2020).

- Lost Art. www.lostart.de/Content/051_ProvenienzRaubkunst/DE/Sammler/H/Haberfeld,%20Hugo.html (04/21/2020).

- N. N.: 1898, in: Gerd Hermann-Susen, Martin Anton Müller (Hg.): Hermann Bahr, Arno Holz, Briefwechsel 1887 – 1923, Goettingen 2015, S. 50-52, S. 51.

- Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 11.05.1921, S. 9.

- Becsi Magyar Ujsag (Wiener Ungarische Zeitung), 13.05.1921, S. 8.

- Reichspost, 17.01.1912, S. 16.

- Elana Shapira: Die kulturellen Netzwerke der Wiener Moderne. Loos, Hoffmann und ihre Klienten, in: Eva B. Ottillinger (Hg.): Wagner, Hoffmann, Loos und das Möbeldesign der Wiener Moderne. Künstler, Auftraggeber, Produzenten, Ausst.-Kat., Imperial Furniture Collection - Vienna Furniture Museum (Vienna), 21.03.2018–07.10.2018, Vienna - Cologne - Weimar 2018, S. 132-135.

- Wien Geschichte Wiki. Hugo Haberfeld. www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Hugo_Haberfeld (04/23/2020).

- Helga Malmberg: Widerhall, Vienna 1961, S. 17.

- Brief von Gustav Klimt in Malcesine am Gardasee an Josef Hoffmann in Wien (presumably June 1913-09/15/1913).

- Revers von Gustav Klimt in Wien, mitunterschrieben von Carl Moll und Hugo Haberfeld (16.12.1907). H.I.N. 15.9214, .

- Kunst und Künstler. Illustrierte Monatsschrift für bildende Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, 1. Jg., Heft 10 (1902/03), S. 403-402.

- Hugo Habermann: Religiöse Kunst in der Wiener Secession, in: Kunst und Künstler. Illustrierte Monatsschrift für bildende Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, 4. Jg. (1906), S. 164-170.

- Kunst und Künstler. Illustrierte Monatsschrift für bildende Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, 4. Jg. (1906), S. 364, S. 487.

- Hugo Haberfeld: Ferdinand Hodler, in: Kunst und Künstler. Illustrierte Monatsschrift für bildende Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, 27. Jg., Heft 5 (1911/12), S. 101-112.

- Hugo Haberfeld: Gustav Klimt, in: Die Kunst. Monatshefte für freie und angewandte Kunst, Band 25 (1912), S. 173-186.

- Hugo Haberfeld (Hg.): Aubrey Beardsley. Ausstellung von Werken alter und moderner Kunst, Ausst.-Kat., Gallery H. O. Miethke (Vienna), 00.12.1904–00.01.1905, Vienna 1904.

- Hugo Haberfeld: Gustav Klimt in der Wiener Secession, in: Kunst und Künstler. Illustrierte Monatsschrift für bildende Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, 2. Jg. (1904), S. 157-158.

- Prager Tagblatt (Mittagsausgabe), 06.05.1907, S. 5.

- Die Zeit, 03.05.1907.

- Kunstchronik. Wochenschrift für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, N.F., 24. Jg., Nummer 3 (1913), S. 41.

- Wiener Zeitung, 12.05.1917, S. 332.

- Auktionshaus Albert Kende (Hg.): 79. Kunstauktion von Albert Kende. Gemälde hervorragender Meister 15. bis 19. Jahrhundert. Kostbare antike Kunstgegenstände aus drei Wiener Sammlungen, Aukt.-Kat., Vienna 1925.

- Wiener Auktionshaus J. Fischer (Hg.): Grosse Auktion, Aukt.-Kat., Vienna 1931.

- Österreichische Photographen-Zeitung, 4. Jg., Heft 2 (1907), S. 23.

- Prager Tagblatt, 16.05.1913, S. 8.

- Curliste Karlsbad, 19.06.1913, S. 2.

- Hugo Haberfeld: Gustav Klimt, in: Die Kunst für Alle. Malerei, Plastik, Graphik, Architektur, 27. Jg. (1911/12), S. 177-183.