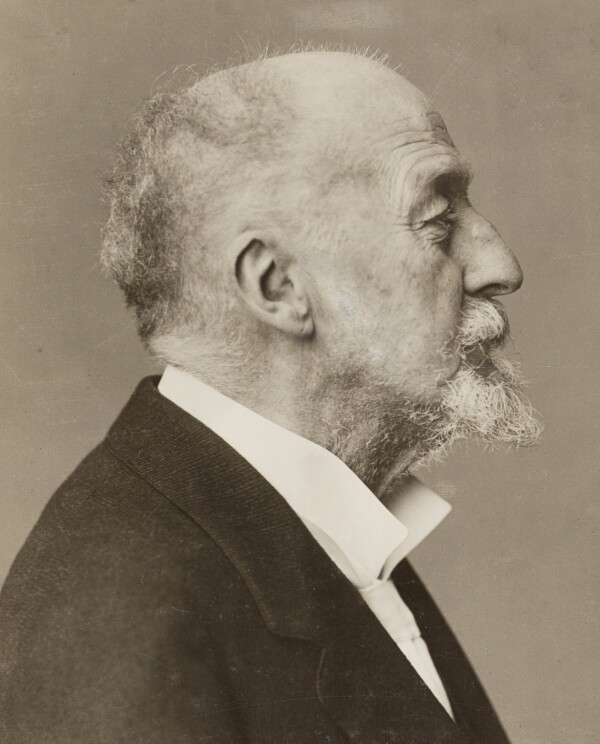

Otto Wagner

Otto Wagner, 1915, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Villa Wagner in Hütteldorf planned by Otto Wagner, 1899, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

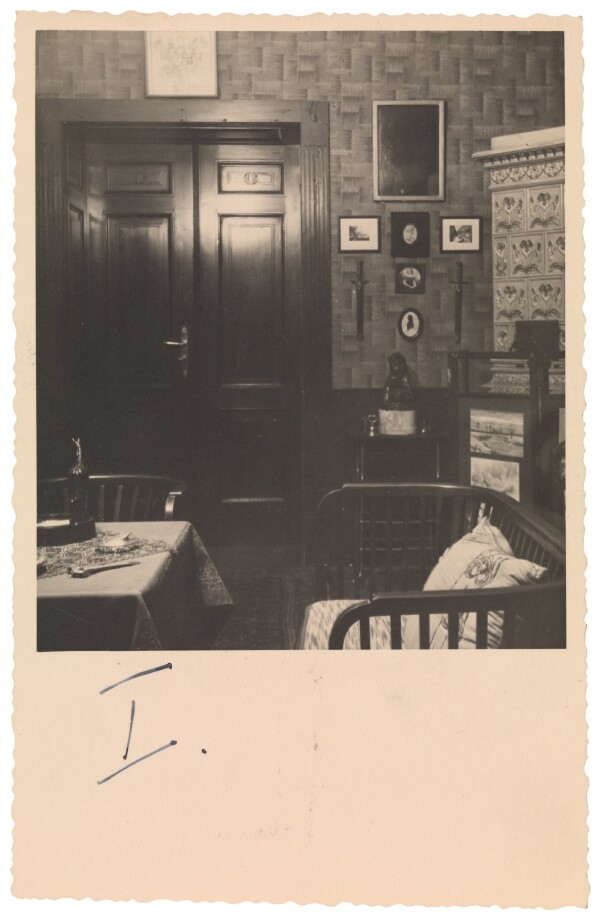

The silence, 1898-1945, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

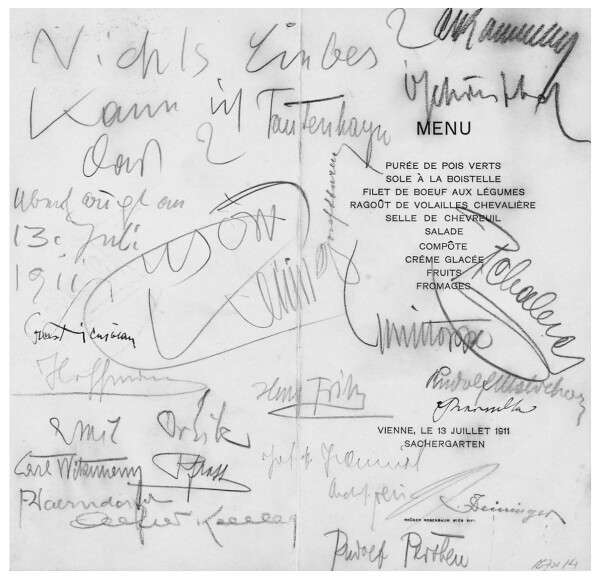

Gustav Klimt: Gustav Klimt's dedication on the menu card of a dinner on the occasion of Otto Wagner's 70th birthday, co-signed by Josef Tautenhayn, Emil Orlik, Fritz Waerndorfer, Emil Hoppe and others., 07/13/1911, Verbleib unbekannt

© Dorotheum Vienna

Otto Wagner was one of the foremost architects and urban planners of the fin de siècle, and his buildings still shape Vienna’s cityscape today. A member of the Vienna Secession, he fundamentally revolutionized the understanding of architecture. With his demand for functional construction methods, he laid the foundation for modern design principles.

Otto Koloman Wagner was born into a wealthy Viennese family on 13 July 1841. In 1857 he attended the Polytechnical Institute in Vienna. After two years he went to Berlin on the advice of Theophil Hansen to attend the local Royal Academy of Architecture. In 1861, Wagner returned to Vienna and became a student at the Academy of Fine Arts, where August von Sicardsburg and Eduard van der Nüll were his teachers. He took on his first commissions as a construction supervisor in 1864 under Ludwig Förster and Theophil Hansen. In 1867, Wagner married Josefine Domhart, the daughter of a Viennese jeweler, whom he divorced so that he would be able to marry his second wife. This first marriage produced two daughters: Susanna and Margarete, the latter of whom died in infancy. Wagner also had two illegitimate sons: Otto Emmerich and Robert Koloman. In 1884 he married the former governess of his daughter Susanna, Louise Stiffel, with whom he had another three children: Stefan, Aloisia “Louise,” and Christine.

Breakthrough and Search for the Style of His Age

Wagner’s first buildings were still entirely committed to the Historicist style. It was only with the construction of the Länderbank (1882–1884, Vienna) and the Villa Wagner I (1886–1888, Vienna) that first deviations from the academic canon became apparent. In his search for a style of his age – a concept inspired by Gottfried Semper – Otto Wagner developed a style he referred to as “free Renaissance.” Although this approach still made use of historical forms, it combined them freely and in new ways.

Wagner’s breakthrough came in 1892/93, when he won first prize for his design for the embankment of the Danube Canal (which was never realized). On the other hand, he received approval for the realization of his project for the network of the Vienna Stadtbahn, an urban railway system. From then on, he was considered a key figure in Viennese urban planning.

From 1894 he taught at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. Among his students were many future members of the Vienna Secession and friends of Gustav Klimt, including Joseph Maria Olbrich, Josef Hoffmann, and Koloman Moser. Toward the end of the 1890s, Wagner finally distanced himself from his academic roots. In his manifesto entitled Modern Architecture of 1896, he explained his views of aesthetics and practicality and came to the conclusion:

“What is impractical cannot be beautiful.”

Otto Wagner and the Vienna Secession

In 1899, Otto Wagner left the Vienna Künstlerhaus and became a member of the Association of Austria Artists Secession, to which he belonged until 1905. The association’s motto “To every time its art. To art its freedom” was in line with Wagner’s understanding of a constantly advancing and modern artistic practice. For example, when asked what he thought of Klimt’s innovative Faculty Painting of Philosophy (1900–1907, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945), Wagner is said to have replied:

“Everything! It’s most sublime! – Michelangelo can pack up now.”

At regular meetings at the Café Museum, the architect exchanged the latest ideas and philosophical concepts with artists and intellectuals of his time.

The Vienna Secession’s members appreciated Wagner’s modern architecture and supported his architectural endeavors. Wagner collaborated on a number of buildings with his former students and Secession colleagues Olbrich, Hoffmann, and Moser. The Secession building, which was planned by Joseph Maria Olbrich in 1898, was clearly based on Wagner’s Vienna Stadtbahn Court Pavilion (1898, Vienna), in the construction of which Olbrich had been involved.

Gustav Klimt and Otto Wagner had a friendly relationship. Wagner even owned a painting by the artist. Correspondence relating to his estate, which is now conserved at the Wien Museum, shows that Klimt’s painting Silence (c. 1898, whereabouts unknown) remained in the possession of Wagner’s daughter Christine, who had inherited it from her father, until at least 1945. The latter may have purchased it at the “II. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs” [“2nd Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists”] in 1898. A photograph, which is unfortunately very dark, is said to show the painting in the living room of Christine Wagner’s apartment, which was confiscated in 1945. Since then, Silence has been considered lost.

In 1905, Wagner left the Secession together with the so-called Klimt Group. The celebrations on the occasion of his 70th birthday in 1911 show how much Wagner was appreciated by the young artists. The Klimt Group presented Wagner with a diploma drawn by Alfred Lichtwark and painted with miniatures by Klimt, as well as a portfolio of erotic drawings, including one by Klimt. Unfortunately, the whereabouts of the portfolio are unknown. Wagner wrote in his diary in December 1917:

“This morning, when I was still in bed, it [...] occurred to me that I could sell the half-erotic artist’s portfolio I had been given for my seventieth birthday.”

There is no evidence if he actually did so. On the menu card of the dinner, Klimt had left a dedication: “Nothing nice? Am I capable of this?” – a tongue-in-cheek expression of his appreciation of the architect and friend.

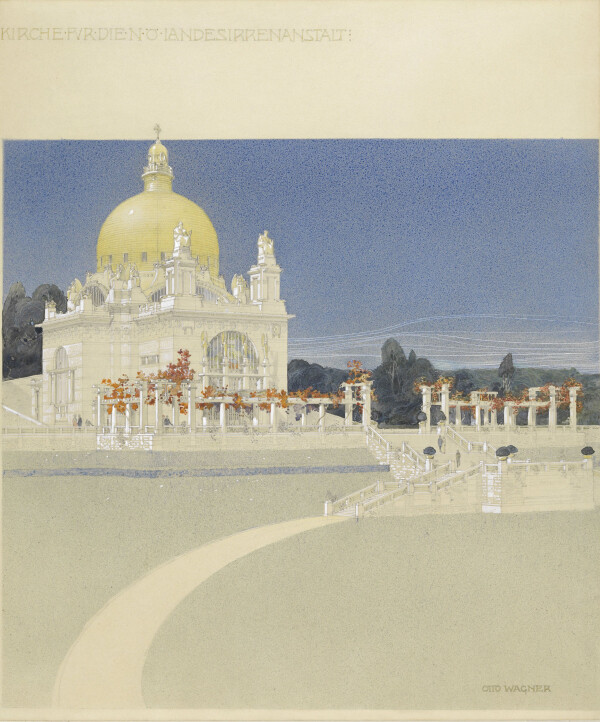

Otto Wagner: Design for the church in St. Leopold am Steinhof, 1902/03, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

Otto Wagner: Design for the exhibition hall of the Association of Austrian Artists, museum project on Karlsplatz, 1914-1916, Wien Museum

© Wien Museum

The Late Work

Wagner’s late work was characterized by the aesthetic principle of practicality, which he implemented by doing without decoration and using glass, iron, and aluminum as materials. Outstanding examples of Wagner’s concept of modern architecture are the Postal Savings Bank (1904–1906/1910–1912, Vienna) and the Kirche am Steinhof [Church of St. Leopold] (1902–1907, Vienna). Wagner was heavily criticized for the use of concrete and glass in a church building. The church was built in collaboration with Kolo Moser, who provided the designs for the stained glass windows; Moser’s design for the altarpiece, however, was rejected.

Between 1900 and 1908, Wagner submitted numerous modern proposals for the redesign of Karlsplatz. Klimt wrote to Emilie Flöge in 1909:

“Wagner will most probably build the museum on Karlsplatz.”

However, when all of Wagner’s sketches were rejected, Klimt, Hoffmann, Deininger, and others held a meeting on 4 May 1910 in the great hall of the Lower Austrian Trade Association. According to the invitation, the purpose of the meeting was

“[…] to spare our hometown the loss of an excellently conceived work of art [...].”

Despite these interventions, Wagner’s building project was never realized. In June 1913, the newly founded League of Austrian Artists, headed by Gustav Klimt as president, elected Wagner as its honorary member.

Otto Wagner died on 11 April 1918, the same year as Klimt, Moser, and Schiele.

Literature and sources

- Rolf Toman (Hg.): Wien. Kunst und Architektur, Vienna 2008, S. 280-297.

- Andreas Nierhaus, Eva-Maria Orosz (Hg.): Otto Wagner, Ausst.-Kat., Vienna Museum (Vienna), 15.03.2018–07.10.2018, Vienna 2018.

- Andreas Nierhaus, Alfred Pfoser (Hg.): Meine angebetete Louise! Otto Wagner. Das Tagebuch des Architekten 1915-1918, Salzburg - Vienna 2019, S. 215.

- Ursula Storch: Die Klimt-Sammlung des Wien Museums. Fakten und Schlüsse, in: Ursula Storch (Hg.): Klimt. Die Sammlung des Wien Museums, Ausst.-Kat., Vienna Museum (Vienna), 16.05.2012–07.10.2012, Vienna 2012, S. 15-16.

- Joseph August Lux: Wanderung zu Gott, Paderborn 1926, S. 61.

- Elana Shapira: Style & Seduction. Jewish Patrons, Architecture and Design in Fin de Siècle Vienna, Waltham 2016.

- N. N.: Das Museumsprojekt auf dem Karlsplatze. Eine Künstlerversammlung, in: Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 05.01.1910, S. 6.

- Max Fabiani: Wagner-Schule, in: Der Architekt. Wiener Monatshefte für Bau- und Raumkunst, 1. Jg. (1895), S. 53-54, S. 53.

- Wien Geschichte Wiki. Otto Wagner. www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Otto_Wagner (04/24/2019).

- Architektenlexikon. Wien 1770–1945. Otto Wagner. architektenlexikon.at/de/670.htm (04/24/2019).

- Berliner Tageblatt und Handels-Zeitung (Abend-Ausgabe) (06.07.1911). www.univie.ac.at/bahr/sites/all/txt/berliner-tageblatt/1911_wagner.pdf (01/13/2022).

- Reichspost, 14.07.1911, S. 7.

- Widmung Gustav Klimts auf der Menükarte eines Diners anlässlich des 70. Geburtstages von Otto Wagner, mitunterschrieben von Josef Tautenhayn, Emil Orlik, Fritz Waerndorfer, Emil Hoppe u.a. (07/13/1911).

- Wiener Zeitung, 14.07.1912, S. 2.

- N. N.: Eine Künstlerversammlung, in: Arbeiter-Zeitung, 03.01.1910, S. 5.