Josef Hoffmann

Josef Hoffmann, in: Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, Band 62 (1928/29).

© Heidelberg University Library

Burial of Gustav Klimt at the Hietzing cemetery, 02/09/1918, Verbleib unbekannt

© APA-PictureDesk

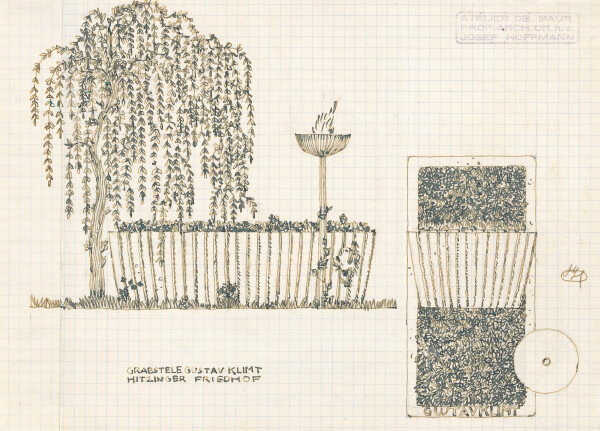

Josef Hoffmann: Grave design for Gustav Klimt

© Graphic Collection of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna

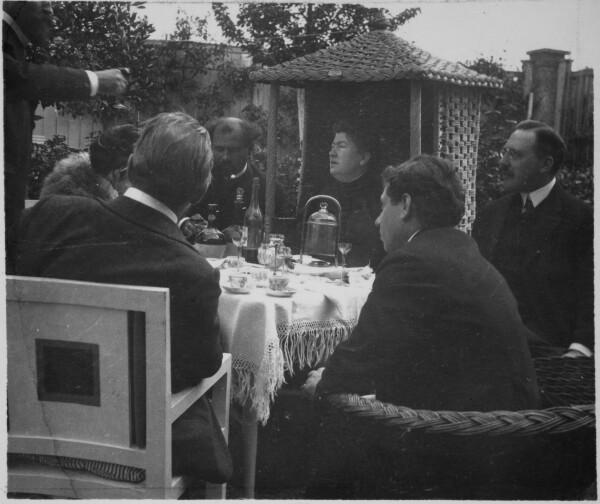

Gustav Klimt in company in the garden of Villa Moll on the Hohe Warte, May 1905, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Josef Hoffmann: Seal stamp by Gustav Klimt, executed by the Wiener Werkstätte, presumably circa 1911, Klimt Foundation

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

Gustav Klimt at a costume party in the cellar of the Primavesi family's country house in Winkelsdorf, presumably 12/30/1917-01/03/1918, MAK - Museum für angewandte Kunst, Archiv der Wiener Werkstätte

© MAK

Josef Hoffmann, an innovative designer and architect, was among the most important personalities of Viennese Modernism. Together with Gustav Klimt, the Vienna Secession and the Wiener Werkstätte he created Gesamtkunstwerke [universal works of art] that were meticulously designed in every detail.

Josef Hoffmann’s Training Years and His Appointment as a Teacher

Josef Hoffmann was born in Pirnitz (now Brtnice) on 15 December 1870. Like Gustav Mahler and Adolf Loos, he went to school in Iglau (now Jihlava). Following his graduation from the State Trade School in Brünn (now Brno) – which he had attended together with Loos – and an apprenticeship in the construction industry in Würzburg, he studied at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts from 1892 to 1895. He was taught by Carl Freiherr von Hasenauer and, after Hasenauer’s death, by Otto Wagner. He was honored for his achievements with the prestigious “Prix de Rome,” which gave him the opportunity to take a study trip to Italy in 1895/96. Apart from Venice, Rome and Naples, Hoffmann also visited Capri. The simple rural architecture he encountered there had a lasting influence on his style. After his return from Italy, he worked at Wagner’s studio. Thanks to a recommendation from Wagner, Hoffmann took over the Architecture Class at the Imperial-Royal School of Arts and Crafts in 1899. At the same time, Kolo Moser accepted his initially provisional teaching post there.

Josef Hoffmann and Gustav Klimt

Hoffmann presumably met Klimt for the first time in the early 1890s. Hoffmann played an instrumental role in the founding of the Siebener Club and the Vienna Secession. He described this time of artistic reorientation as follows:

“The meetings with friends who worked as painters, architects and sculptors began to suggest more and more new paths […]. Klimt, Moll […] Wagner, Olbrich wanted nothing more to do with the usual exhibition activities at the Künstlerhaus, which resulted in our joint departure and in the founding of the Vienna Secession.”

Hoffmann and Moser became the most important exhibition designers for this avant-garde artists’ association. Hoffmann also played a defining role in the design of its magazine Ver Sacrum. In 1905, after several successful years, he left the Secession together with the Klimt Group.

The two artists remained close friends and collaborators until the death of the master painter. Like many of Klimt’s companions, Hoffmann attended Klimt’s funeral on 9 February 1918. Around 1935, Hoffmann designed a stela for Klimt’s grave, which was never executed, however.

Klimt and Hoffmann: Collaborations in Interior Decoration

“Quadratl-Hoffmann” [“Small Squares Hoffmann”], as the designer was nicknamed, worked on the concept of the “Künstlerkolonie,” an artists’ colony on Hohe Warte, from 1900. He designed a duplex for Moser and Moll (1900/01) and villas for the photographers Henneberg and Spitzer (1901–1903). At the Villa Henneberg, in particular, the interplay between Hoffmann’s interior design and Klimt’s art reveals its unsurpassable finesse in the presentation of the work Portrait of Marie Henneberg (1901/02, Kulturstiftung Sachsen-Anhalt – Kunstmuseum Moritzburg Halle (Saale)). Further residential buildings in the same neighborhood followed a few years later, including the Villa Eduard Ast (1909–1911). The ladies’ parlor at this villa provided the ideal stage for Klimt’s Danaё (1907/08, privately owned).

From 1905 at the latest, Hoffmann and several fellow artists, including Klimt, dedicated themselves to the execution of the epitome of the Gesamtkunstwerk: Stoclet Palace in Brussels. Together they visited the construction site of this temple of the Wiener Werkstätte after a sojourn in London in 1906. Hoffmann and Klimt entertained a lively exchange of ideas when Klimt was designing the centerpiece of the palace, Stoclet Frieze (1905–1911, privately owned).

Another successful collaboration between Klimt and Hoffmann was the dining room in the villa of the Knips family (1924–26) in Vienna-Döbling, 19th District, also created by the ingenious universal designer, which served as an ideal vehicle of presentation for Klimt’s work Portrait of Sonja Knips (1897/98, Belvedere, Vienna).

Hoffmann as an Exhibition Designer

This portrait, the first to be executed in a square format by Klimt, was also presented at the “World’s Fair” in Paris in 1900 in the rooms of the Grand Palais that had been designed by Hoffmann. Klimt furthermore exhibited Pallas Athene (1898, Wien Museum, Vienna) as well as his Faculty Painting Philosophy (1900–1907, destroyed by fire at Immendorf Castle in 1945). The latter work, which had been met with derision in Vienna, was rewarded with a gold medal in Paris.

In 1902, Hoffmann was in charge of the room design and the overall artistic direction of the famous “XIV. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession” [“14th Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists Secession”], the so-called “Beethoven Exhibition.”

Two years later, he created the designs for the rooms of the Secession at the “Louisiana Purchase Exposition” in St. Louis, which was conceptualized like a World’s Fair. Because of the lack of available space, these designs focused on the monumental presentation of Klimt’s Faculty Paintings. The designs were rejected by the Imperial-Royal Ministry of Culture and Education. Because of further disagreements, the Secession finally withdrew from the exhibition.

Hoffmann also designed the rooms for the “Jubiläums-Ausstellung Mannheim 1907” [“1907 Mannheim Jubilee Exhibition”], where Klimt presented his works The Three Ages of Woman (1905, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Rome), Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907, Neue Galerie New York, New York) and Portrait of Fritza Riedler (1906, Belvedere, Vienna). From late 1907, Hoffmann was in charge of the overall architectural concept of the epochal “Kunstschau Wien.” Hoffmann became the vice-president of the Austrian Artists League, which had been founded with the purpose of establishing this new exhibition format and which was presided over by Klimt as its president.

A few years later, Hoffmann designed the no longer existent Austrian Pavilion for the “Esposizione Internazionale di Roma 1911” [“International Art Exhibition of Rome 1911”], which was dominated by references to classical architecture. He recalled:

“In 1912 [!], I was asked to build the Austrian exhibition building in Rome. […] Among the painters it was especially Gustav Klimt who was presented to an international audience for the first time.”

Klimt, who had in fact participated in other international exhibitions before, was represented with eight paintings and won a cash prize.

Hoffmann and the Wiener Werkstätte

The most important commissions executed by the Wiener Werkstätte, which had been founded by Hoffmann, Moser and Fritz Waerndorfer in 1903, included the whole interior decoration of the “Schwestern Flöge” fashion salon (1904), the Purkersdorf Sanatorium (1904–1906), the Cabaret Fledermaus (1907) and the above-mentioned Stoclet Palace in Brussels.

Klimt’s interest and involvement in these projects are well documented. He was also a client of this innovative arts and crafts collective, purchasing several pieces of jewelry for himself and for Emilie Flöge. Some of these pieces were designed by Hoffmann himself, such as Klimt’s seal stamp or his tiepin. Hoffmann and the Wiener Werkstätte also provided furniture for the painter’s studio at Josefstädter Straße 21 around 1904, which was moved to Klimt’s last studio at Feldmühlgasse 11 (previously 9) in 1911.

Hoffmann, Klimt and the Primavesis

Shortly before the onset of World War I, when the Wiener Werkstätte was losing some of its profitability, Hoffmann established ties with the Primavesis. He subsequently built the Villa Skywa-Primavesi (1913–1915) in Vienna-Hietzing, 13th District, and the Primavesis’ cottage (1913/14) in Winkelsdorf (now Koutny nad Desnou), which no longer exists. This cottage was the site of regular social events, which were frequently attended by Klimt, who had also found important patrons and friends in this family. He also spent his last New Year’s Eve with Hoffmann, Anton Hanak and other companions at the cottage in 1917/18. Hoffmann recalled the legendary celebrations in Winkelsdorf:

“Officially, we had to go to bed early. But the guests secretly met with their host in the lower rooms, where there was good wine and everybody was in high spirits […]. Klimt also happily enjoyed this friendly company […].”

Hoffmann’s Last Decades

After the end of Word War I, Hoffmann received only few commissions. In the 1920s, he executed several villas and worked as an exhibition designer. Together with Peter Behrens, Oskar Strnad and Josef Frank he designed the Austrian Pavilion for the “Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Moderns” [“International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts”] in Paris in 1925. Hoffmann’s design for the Austrian Pavilion at the “Venice Biennale” was executed in 1934. He also worked on social housing projects.

Hoffmann was forced to retire as a university teacher in 1937. He considered the “Anschluss” of Austria as an opportunity to reposition Viennese arts and crafts. He received several commissions and tried to profit from the public’s unbroken admiration of his work. After the war had ended, Hoffmann was primarily occupied with his position as Austria’s general commissioner for the “Venice Biennale” and a new teaching post.

In 1955, for the 50th anniversary of the construction of Stoclet Palace, Hoffmann visited his best-known work for the last time. He died the following year on 7 May 1956. Josef Hoffmann was laid to rest at the Vienna Central Cemetery in an Ehrengrab [grave of honor] designed by Fritz Wotruba.

Literature and sources

- Maria Hussl-Hörmann: Gustav Klimt und Josef Hoffmann Wegkreuzungen, in: Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt – Josef Hoffmann. Pioniere der Moderne, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna) - Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 25.10.2011–04.03.2012, Munich 2011, S. 16-35.

- Ernst Ploil: Die Ateliereinrichtung des Gustav Klimt, in: Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt – Josef Hoffmann. Pioniere der Moderne, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna) - Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 25.10.2011–04.03.2012, Munich 2011, S. 300-309.

- Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt – Josef Hoffmann. Pioniere der Moderne, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna) - Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 25.10.2011–04.03.2012, Munich 2011.

- Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Matthias Boeckl, Christina Witt-Dörring (Hg.): Wege der Moderne / Ways to Modernism. Josef Hoffmann, Adolf Loos und die Folgen / and Their Impact, Ausst.-Kat., MAK - Museum of Applied Arts (Vienna), 17.12.2014–19.04.2015, Vienna 2015.

- Eva B. Ottillinger (Hg.): Wagner, Hoffmann, Loos und das Möbeldesign der Wiener Moderne. Künstler, Auftraggeber, Produzenten, Ausst.-Kat., Imperial Furniture Collection - Vienna Furniture Museum (Vienna), 21.03.2018–07.10.2018, Vienna - Cologne - Weimar 2018.

- Peter Noever, Marek Pokorný (Hg.): Josef Hoffmann. Selbstbiographie, Ostfildern 2009, S. S. 21f, S. S. 33.

- Marianne Hussl-Hörmann: Gustav Klimt und Josef Hoffmann, in: Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt – Josef Hoffmann. Pioniere der Moderne, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna) - Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 25.10.2011–04.03.2012, Munich 2011, S. 18-34.

- Rainald Franz: Gustav Klimt und Josef Hoffmann als Reformer der grafischen Künste in der Gründungsphase der Secession und Wiener Werkstätte, in: Agnes Husslein-Arco, Alfred Weidinger (Hg.): Gustav Klimt – Josef Hoffmann. Pioniere der Moderne, Ausst.-Kat., Lower Belvedere (Vienna) - Upper Belvedere (Vienna), 25.10.2011–04.03.2012, Munich 2011, S. 38-49.

- Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Matthias Boeckl, Rainald Franz, Christian Witt-Dörring (Hg.): Josef Hoffmann. 1870–1956. Fortschritt durch Schönheit, Ausst.-Kat., MAK - Museum of Applied Arts (Vienna), 15.12.2021–19.06.2022, Basel 2021, S. 109-117.

- Vereinigung bildender KünstlerInnen Wiener Secession (Hg.): Ver Sacrum. Mitteilungen der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, 6. Jg., Sonderband 3 (1903).