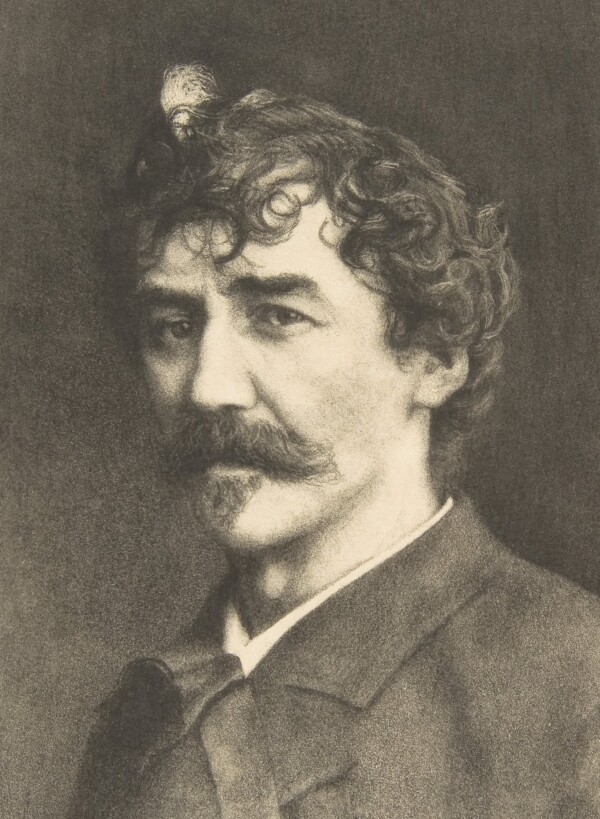

James McNeill Whistler

Thomas Robert Way: James McNeill Whistler

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The painter and graphic artist James McNeill Whistler was primarily active in Paris and London. In his work, he combined French, Pre-Raphaelite and Japanese influences, informed the discourse on landscape painting, and gained international recognition especially in his final years.

James Abbot McNeill Whistler was born in Lowell, Massachusetts, on 11 July 1834. Due to his father’s work as a railroad engineer, the family moved to St. Petersburg in 1843, where Whistler took drawing lessons at the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts. After his father’s death, the family returned to the United States in 1849, and between 1851 and 1854 Whistler was at the West Point Military Academy, where he also attended drawing classes. He then worked briefly as a cartographer with the Navy Department in Washington.

In 1855 he decided to become an artist and moved to Paris, where he met such avant-garde artists as Edgar Degas and Henri Fantin-Latour. He studied at the Ecole Impériale et Spéciale de Dessin and became a student at the studio of Charles Gleyre, who also taught the Impressionists Claude Monet and Auguste Renoir. At the Louvre, he familiarized himself with the Old Masters, Oriental art, and Japanese prints and was particularly enthusiastic about 17th-century Spanish and Dutch painting. He also traveled to the Netherlands and in 1858 took to making etchings.

His painting At the Piano (1858/59, The Taft Museum, Cincinnati, Ohio) – a portrait of Lady Seymor Haden – was rejected by the jury of the Paris Salon in 1859, but was exhibited in the studio of the painter Bouvin, where he met Gustave Courbet. Discouraged by the Salon’s rejection, Whistler moved to London in 1859 and exhibited At the Piano at the Royal Academy. His early work was influenced by French Impressionism and Realism, while his subsequent output was largely inspired by the English Pre-Raphaelites: Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and Albert Joseph Moore were among his friends.

In 1862, he gained international notoriety with Symphony in White No. 1 (1861/62, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Washington), as the work was rejected both by the Royal Academy and the Paris Salon and presented at the Salon des Refusés alongside Edouard Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863, Musée d'Orsay, Paris).

In the first half of the 1860s, Whistler increasingly incorporated Asian and especially Japanese motifs into his work, such as in the paintings The Princess from the Land of Porcelain and Caprice in Purple and Gold: The Golden Screen.

Between 1865 and 1866 he traveled to Chile, painting coastal landscapes in Valparaiso. In Europe he exhibited regularly in London, and in 1872 he produced what are probably his most famous and compositionally trailblazing works, Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1 (1871, Musée d’Orsay, Paris) – known as Whistler's Mother – and Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 2 (1872/73, Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum), which he signed with his butterfly monogram.

An important client of Whistler’s was the wealthy shipowner Frederick Leyland, whose wife he portrayed in Symphony in Flesh Color and Pink (1871–1874, The Frick Collection, New York) and for whom he decorated the so-called “Peacock Room” in 1876/77 as Harmony in Blue and Gold (1876/77, Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.). The extraordinary room, with its elaborate peacock decorations and numerous golden details, served to display Leyland’s collection of Chinese vases and exerted a strong influence on the interior design of the Aesthetic Movement. Whistler’s friend and patron Charles Lang Freer purchased the “Peacock Room” in 1904 and had it transported to Detroit to set it up in his own home.

In the 1870s, Whistler’s Nocturne series of views of the Thames at night harked back to William Turner’s late seascapes, yet evolved in a different direction artistically. John Ruskin’s criticism of Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (1875, Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, Michigan) entailed a lawsuit that put the artist in a difficult financial position.

In 1879 he moved to Italy, where he made several etchings in Venice. Back in England from 1880, he produced prints and lithographs, designed interiors, delved into aesthetic theory, and published Whistler versus Ruskin. Art and Art Critics (1878), Ten o’Clock (1888), and The Gentle Art of Making Enemies (1890).

In 1884 he became a member of the Royal Society of British Artists, went back to Paris, and gained increasing international recognition through his taking part in exhibitions, winning awards, and being admitted to various artists’ associations. His extensive oeuvre influenced European modernism particularly in terms of composition, tonality, and color harmony.

As early as 1895, Whistler’s works were also shown in Vienna, in the Society of Reproductive Art’s anniversary exhibition at the Künstlerhaus, “III. Internationale Graphische Ausstellung” [“3rd International Graphic Art Exhibition”], in which Gustav Klimt was also represented with his Portrait of Josef Lewinsky as Carlos in Clavigo (1895, Belvedere, Vienna).

Klimt and Whistler corresponded at the time of the founding of the Association of Austrian Artists – Vienna Secession in 1897, and as the association’s first president Klimt invited him to become an honorary member. Josef Engelhart even visited Whistler in Paris in 1898 to recruit him as a member and received several letters of recommendation to obtain paintings on loan from private collectors for the Vienna Secession’s exhibitions. Eventually he became a corresponding member and in return appointed Klimt honorary member of the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers, of which he was elected president in 1898. In the Vienna Secession’s “I. Kunstausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs” [“1st Art Exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists”] only a few of Whistler’s lithographs were on view, since, according to Engelhart, the owners of about 20 paintings were at war with the artist and did not want to lend their works.

Whistler spent the last years of his life in seclusion and died in the borough of Chelsea in London on 17 July 1903.

Literature and sources

- ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA. James McNeill Whistler. www.britannica.com/biography/James-McNeill-Whistler (05/25/2020).

- Caitlin Silberman: Evolutionary. Whistler, Darwin, and the Peacock Room, 29.12.2015. asia.si.edu/evolutionary-whistler-darwin-and-the-peacock-room/ (05/25/2020).

- Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.. A. asia.si.edu/exhibition/the-peacock-room-comes-to-america/ (05/25/2020).

- Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.. B. asia.si.edu/object/F1904.61/ (05/25/2020).

- Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.. C. asia.si.edu/object/F1903.91a-b/ (05/25/2020).

- Detroit Institute of Arts. Nocturne in Black and Gold, the Falling Rocket, 1875. www.dia.org/art/collection/object/nocturne-black-and-gold-falling-rocket-64931 (03/10/2022).

- Neue Freie Presse, 13.02.1898, S. 10.

- Karl von Lützow: Die Modernen im Künstlerhause, in: Neue Freie Presse, 19.10.1895, S. 1-3.

- Richard Muther: Whistler, in: Die Zeit, 22.07.1903, S. 1-3.

- Franz Servaes: Whistler, in: Neue Freie Presse, 22.07.1903, S. 1-3.

- Dougald S. Mac Coll: Whistlers Pfauenzimmer, in: Kunst und Künstler. Illustrierte Monatsschrift für bildende Kunst und Kunstgewerbe, 3. Jg. (1905), S. 112-114.

- Josef Engelhart: Meine Erlebnisse mit James Mac Neill Whistler aus dem Jahre 1898, in: Der Architekt. Wiener Monatshefte für Bau- und Raumkunst, 21. Jg. (1916/18), S. 53-56.

- Brief von Gustav Klimt und Wilhelm Schölermann in Wien an James McNeill Whistler (13.12.1897). MS Whistler S150.