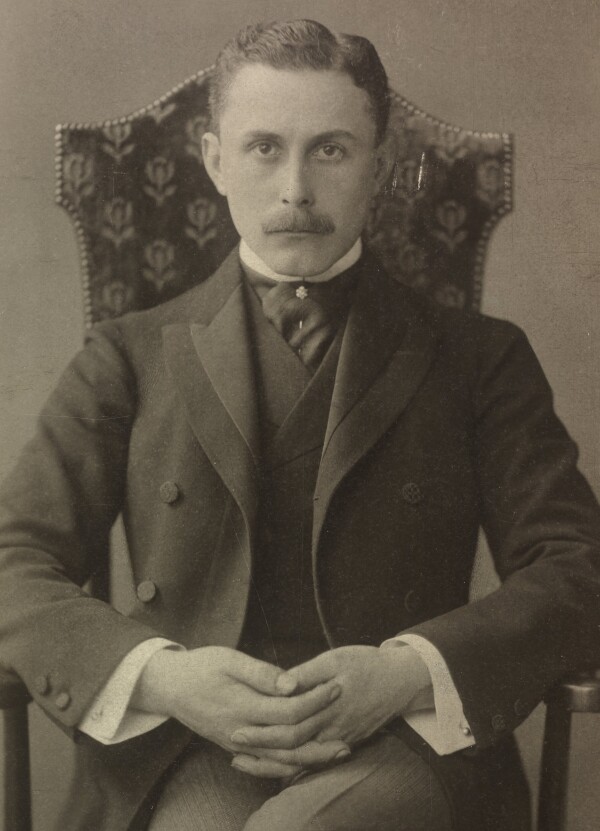

Adolf Loos

Adolf Loos photographed by Otto Mayer, 1904

© Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Austrian National Library

Adolf and Lina Loos in the fireplace alcove of their apartment at Bösendorferstrasse 3, 1903

© The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

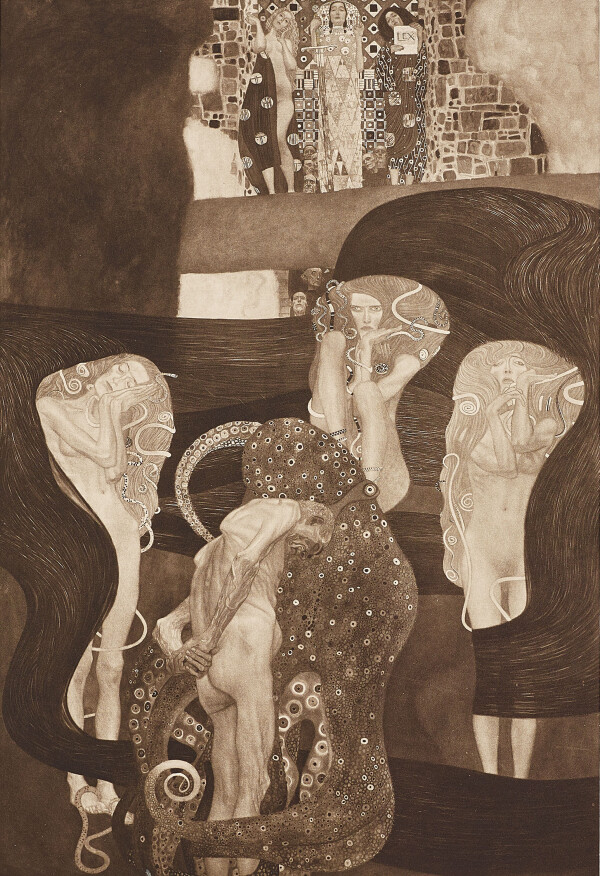

Gustav Klimt: Jurisprudence, 1903-1907, 1945 in Schloss Immendorf verbrannt, in: Kunstverlag Hugo Heller (Hg.): Das Werk von Gustav Klimt, Vienna - Leipzig 1918.

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

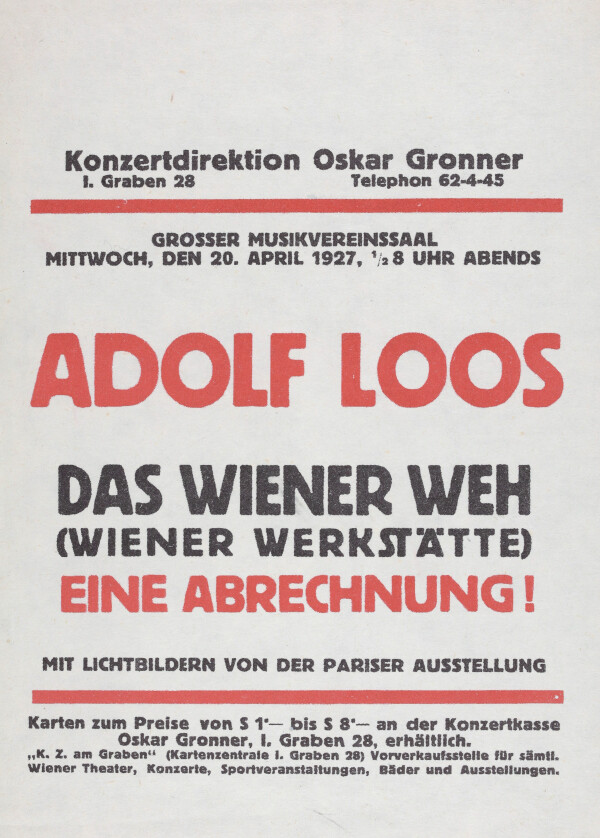

Poster "Das Wiener Weh" (Wiener Werkstätte) Eine Abrechnung!", 20.04.1927

© Klimt Foundation, Vienna

The house on Michaelerplatz by Adolf Loos, photographed by Bruno Reiffenstein, around 1920

© Wien Museum

Around 1900, architect and author Adolf Loos vehemently opposed the Vienna Secession’s prevalent aesthetics. Influenced by architectural tendencies from the United States, the Biedermeier’s domestic culture, and the Chippendale style, he created buildings and interiors marked by practicability and materiality. In spite of all, he considered Gustav Klimt a revolutionary.

Globe Trotter Adolf Loos

Adolf Loos was born in Brno (now in Czechia) on 10 December 1870. His father’s profession – he was a sculptor and master stonemason – proved influential for the son’s career. Loos’s relationship to his mother was strained, especially after his father’s premature death.

Loos went to school in Brno, Jihlava (now in Czechia), and Melk. In Jihlava he met Josef Hoffmann, who was of the same age. Having graduated from secondary school, Loos attended the Imperial-Royal State Vocational School in Reichenberg and then enrolled at the Imperial-Royal State Vocational School in Brno, as did Hoffmann. From 1892 he studied architecture at the Technical University in Dresden. Dropping out before graduation, he traveled the USA for several years starting in 1893. All the combined impressions gained in Chicago, where he also visited the World’s Fair, New York, St. Louis, and Philadelphia had an enormous impact on Loos’s style. He returned to Europe in May 1896 and settled in Vienna. For a short while he worked in the studio of Karl Mayreder, but soon decided on what was primarily a journalist’s career. Peter Altenberg, Karl Kraus, and Arnold Schönberg became important companions. Loos wrote for the Neue Freie Presse and published the essay Die alte und die neue Richtung in der Baukunst [“Old and New Directions in Architecture”], which he had written for a competition in response to Otto Wagner’s treatise Moderne Architektur [“Modern Architecture”], in the journal Der Architekt, winning the second prize.

Loos’s Rebellion against Viennese Modernism

In July 1898, Loos’s opinions were also spread in Ver Sacrum. In his polemicizing essay Die Potemkinsche Stadt [“The Potemkin City”] he maintained the view that an architect was to refrain from major attempts at artistic creativity. This and Hoffmann’s refusal to have the Secession’s Ver Sacrum Room designed by Loos led to their breakup. Loos subsequently tried to gain ground as an independent interior architect and from the outset primarily decorated various apartments and designed publicly accessible localities. He developed a purified modernism vehemently directed against the concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk or universal work of art propagated by Hoffmann, the Vienna Secession, and the Wiener Werkstätte. Loos defined himself as “an opponent of whatever direction seeing something particularly deserving in the fact that everything from building to coal scoop comes from the hand of the same architect.” Nonetheless he was also against Historicism’s stylistic blunders.

In spring 1899, he attracted a great deal of public attention for the first time with his puristic and functional design of the Café Museum, “the first modern one [café] in Vienna, which was on its way to becoming Secessionist,” as Ludwig Hevesi remarked. The coffeehouse was regularly frequented by Gustav Klimt and other Secessionists.

“And yet I believe in Klimt’s genius”

Even if Loos was basically diametrically opposed to the position of fin-de-siècle art, he expressed recognition for Klimt as an exceptional artist and particularly showed solidarity in the context of the latter’s scandal-riddled Faculty Paintings in an undated and unpublished typescript entitled Ein Kapitel aus der Geschichte der Malerei im XX. Jahrhundert. Klimt [“A Chapter from the History of Painting in the 20th Century. Klimt”]:

“In everything great we did over the past years we are indebted to this master: Gustav Klimt.”

Moreover, following his analytical review of the ceiling paintings, he concluded:

“Until now we have only talked about what is revolutionary on the outside. […] Klimt’s magnitude could not be explained by this alone. For it is the spirit that builds the body. Klimt is the greatest inner revolutionary among the painters.”

So far it has not been possible to find out with certainty whether Klimt and Loos ever interacted with each other directly.

“Fundamental Remarks on the Seemingly Functional”

In the years after the turn of the century, Loos’s activities as an architect intensified, as he was responsible for the construction and interior decoration of a multitude of stores, private villas, housing estates, and office buildings in Vienna. In 1902/03 he furnished his own apartment at Bösendorferstraße 3 (formerly Giselastraße, in Vienna’s Inner City/1st District), into which he moved with his young wife Lina Loos. They already divorced again in 1905. That year, Loos designed the apartment of Carl Reininghaus (which no longer exists) in Wieden, Vienna’s 4th District. The art patron had rescued Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze, the famous wall decoration for the Vienna Secession (1901/02, Belvedere, Vienna), from demolition by purchasing it.

In the context of the “Kunstschau Wien” in 1908, Loos met enfant terrible Oskar Kokoschka, whose mentor he was to become. Klimt had encouraged the young artist to participate. On 21 January 1910, Loos, following an invitation extended by the Academic Association of Literature and Music in Vienna, held his scandalous lecture “Ornament und Verbrechen” [“Ornament and Crime”] for the first time, with which he impressed the younger generation of Expressionists. Loos had already presented an earlier version under a different title in November 1909 at the gallery of Paul Cassirer in Berlin – at an event organized by Herwarth Walden. An advocate of material quality and practicability, Loos took a firm stand against decorative Jugendstil or Art Nouveau and the Wiener Werkstätte, to which he also referred to as “Wiener Weh” (“Weh” referring to the letter “double-u” in German and being a slang expression for “sissy”). In the course of this lecture he emphasized that the practicability of a structure and its interior were superior to any modern ornamental system. He fuelled these views in subsequent public lectures. His largest and at the same time most provocative building project in Vienna’s inner city was the Looshaus on Michaelerplatz, which he realized around the same time, between 1909 and 1911, his client being the exclusive gentlemen’s outfitter Goldman & Salatsch. The austere architecture, concentrating on materiality, caused a scandal that led to a temporary work stoppage. In those years, he also designed the interior for the Viennese men’s fashion store Kniže & Comp.

In 1912 Loos was asked to apply as successor of Otto Wagner at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, which he refused. He founded a private architectural school instead, the teaching activities of which were unfortunately interrupted by the outbreak of World War I. Ornament and Crime was first published in French in 1913.

When the war was over, Loos married Elsie Altmann, thirty years his junior. In the years to come, he would mostly be involved in council housing projects and held the position of head of the Vienna Housing Office. Due to disagreements, however, he resigned from this function, and from 1922 on mainly resided in France, where he built the houses of Tristan Tzara and Josephine Baker. Loos could hardly make a living from his commissions, so that he depended on Altmann’s maintenance. They were divorced in 1926. After his return from France in 1928, Adolf Loos faced serious accusations of gross indecency in Vienna. The actual scope of the crimes committed by him only became known decades after his death. That year he also met his third wife, Claire Beck.

Adolf Loos died an impoverished architect at Kalksburg (a sanatorium for alcoholics) near Vienna from the consequences of a cerebral stroke on 23 August 1933. The writer Karl Kraus, his companion and friend of many years, held the funeral eulogy. A gravestone designed on the basis of Loos’s sketches adorns his final resting place on Vienna’s Central Cemetery.

Literature and sources

- Architektenlexikon. Wien 1770–1945. Adolf Loos. www.architektenlexikon.at/de/362.htm (04/15/2020).

- Eva B. Ottillinger: Was sind moderne Möbel? Antworten von Wagner, Hoffmann und Loos, in: Eva B. Ottillinger (Hg.): Wagner, Hoffmann, Loos und das Möbeldesign der Wiener Moderne. Künstler, Auftraggeber, Produzenten, Ausst.-Kat., Imperial Furniture Collection - Vienna Furniture Museum (Vienna), 21.03.2018–07.10.2018, Vienna - Cologne - Weimar 2018, S. 109-121.

- Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Matthias Boeckl, Christina Witt-Dörring (Hg.): Wege der Moderne / Ways to Modernism. Josef Hoffmann, Adolf Loos und die Folgen / and Their Impact, Ausst.-Kat., MAK - Museum of Applied Arts (Vienna), 17.12.2014–19.04.2015, Vienna 2015.

- Adolf Loos: Die Interieurs in der Rotunde, in: Adolf Loos (Hg.): Ins Leere gesprochen, Vienna 1898, S. 81.

- Christopher Long: Vermächtnis einer Kampfdekade.»Ornament und Verbrechen ab 1909«, in: Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Matthias Boeckl, Christina Witt-Dörring (Hg.): Wege der Moderne / Ways to Modernism. Josef Hoffmann, Adolf Loos und die Folgen / and Their Impact, Ausst.-Kat., MAK - Museum of Applied Arts (Vienna), 17.12.2014–19.04.2015, Vienna 2015, S. 184-193.

- Ludwig Hevesi: Adolf Loos, in: Altkunst – Neukunst, Vienna 1909, S. 284-288.

- Burkhardt Rukschcio, Roland Schachel: Adolf Loos. Leben und Werk, Vienna - Salzburg 1982.

- Eva B. Ottillinger: Adolf Loos. Wohnkonzepte und Möbelentwürfe, Salzburg - Vienna 1994.

- Eva B. Ottillinger (Hg.): Wagner, Hoffmann, Loos und das Möbeldesign der Wiener Moderne. Künstler, Auftraggeber, Produzenten, Ausst.-Kat., Imperial Furniture Collection - Vienna Furniture Museum (Vienna), 21.03.2018–07.10.2018, Vienna - Cologne - Weimar 2018.

- Adolf Loos: Ein Kapitel aus der Geschichte der Malerei im XX: Jahrhundert. Klimt, o.D., in: Adolf Loos. Schriften, Briefe, Dokumente aus der Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Vienna 2018, S. 34-36.

- Tobias G. Natter: »Klimt hat uns den Himmel genommen, Klimt hat uns den Himmel gegeben.«, in: Adolf Loos. Schriften, Briefe, Dokumente aus der Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Vienna 2018, S. 37-41.

- Beatriz Colomina: Sex, Lies and Decoration: Adolf Loos and Gustav Klimt, in: Jehuda E. Safran (Hg.): Adolf Loos Our Contemporary, New York 2012.

- Ein Kapitel aus der Geschichte der Malerei im XX. Jahrhundert. Klimt, Wien, o.D.. Unveröffentlichtes Typoskript.